❧ THE PAGEANT

ART EDITOR LITERARY EDITOR

C. HAZELWOOD SHANNON J. W. GLEESON WHITE

PUBLISHED BY MESSRS. HENRY AND COMPANY

93 ST. MARTIN’S LANE LONDON

MDCCCXCVII

❧ FOREWORD

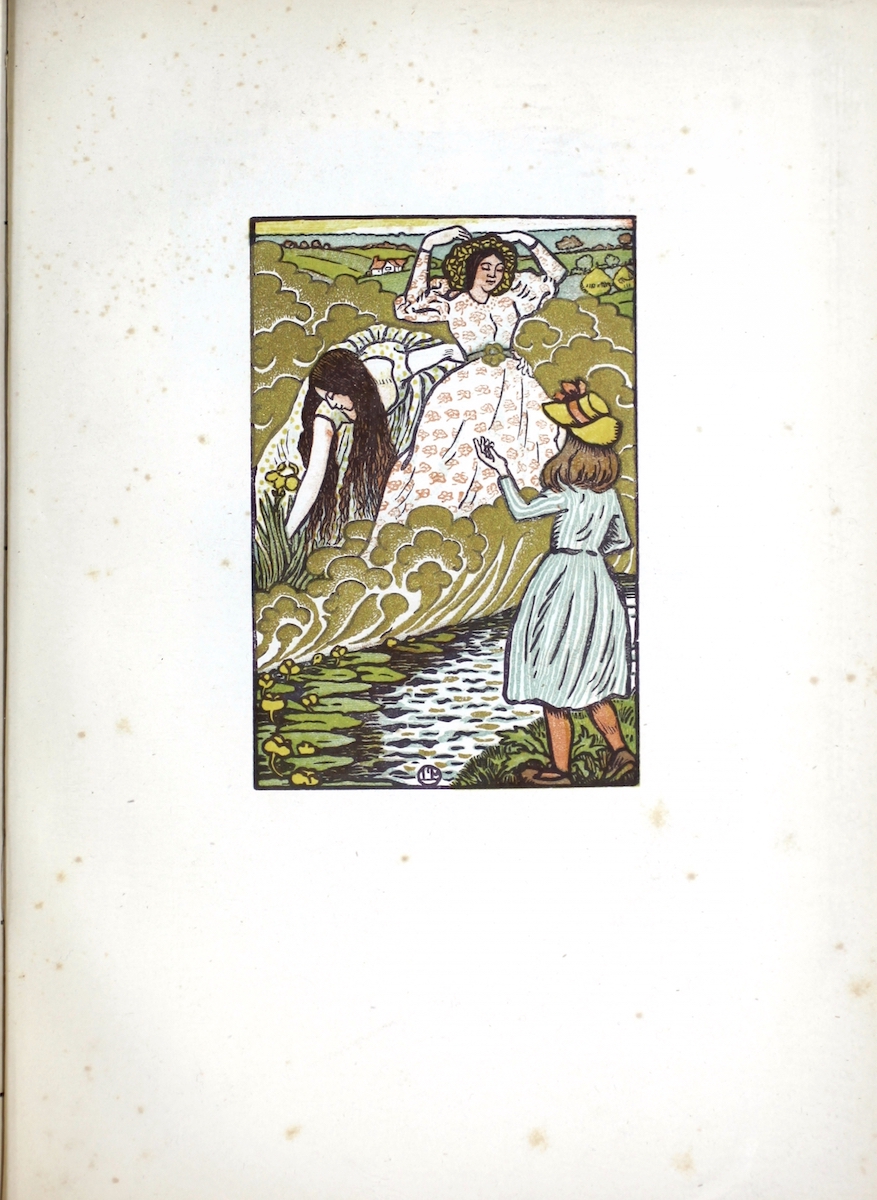

TO ENSURE THE GREATEST POSSIBLE DELICACY OF EFFECT, THE

PICTURES INTERLEAVED HAVE BEEN PRINTED THROUGHOUT BY

THE SWAN ELECTRIC ENGRAVING COMPANY, BY WHOM ALSO THE

BLOCKS HAVE BEEN MADE. THE MIXING OF THE COLOURED INKS

HAS BEEN SUPERVISED BY THE ART EDITOR. THE WOOD-CUT, IN

FIVE BLOCKS, AND THE WRAPPER HAVE BEEN PRINTED BY MR.

EDMUND EVANS. THE LINE BLOCKS ARE BY MESSRS. CARL

HENTSCHEL AND COMPANY, AND MESSRS. WALKER AND BOUTALL.

THE PRINTING OF THE BOOK IS BY MESSRS. T. AND A. CONSTABLE,

FROM THE DESIGN OF THE ART EDITOR. THE COPYRIGHT OF

THE FRONTISPIECE AND OF THE PLATES ON PAGES 9, 15, AND 161

IS THE PROPERTY OF MR. L. LECADRE, JUN., PARIS; THAT OF THE

PLATES ON PAGES 99, 111, 189 , AND 203 IS THE PROPERTY OF

MR. F. HOLLYER; AND THAT OF THE PLATE ON PAGE 149 IS THE

PROPERTY OF MESSRS. BRAUN, CLEMENT AND COMPANY OF PARIS.

❧THE OUTER WRAPPER IS DESIGNED BY GLEESON WHITE, THE

CLOTH BINDING BY CHARLES RICKETTS, THE END-PAPERS BY

LUCIEN PISSARRO.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Front Cover

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . Charles Ricketts

Endpapers . . .

. . .

. . .

. . Lucien

Pissarro

Half Title

Page [v]

Title

Page [vii]

Foreword C. Hazelwood

Shannon & J. W. Gleeson

White [ix]

❧ LITERARY CONTENTS

A POSTSCRIPT TO

RETALIATION . . . . Austin

Dobson 1

THE PICTURES OF GUSTAVE

MOREAU . . Gleeson

White 3

JULY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Michael

Field 17

JULES BARGEY

D’AUREVILLY . . . . Edmund

Gosse 18

MISS PEELE’S APOTHEOSIS: A STUDY IN

EXTRA-SUBURBAN

AMENITIES .

. . . Victor

Plarr 32

THE SONG OF

SONGS . . . Rosamund Marriott

Watson 63

BLIND

LOVE . . . . . . . Laurence Housman 64

ON THE SOUTH COAST OF

CORNWALL . . . John

Gray 47

THE GODS GAVE MY DONKEY WINGS

. Angus Evan

Abbott 87

TWENTY-FOUR QUATRAINS FROM

OMAR . F. York

Powell 79

LIGHT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . John

Gray 113

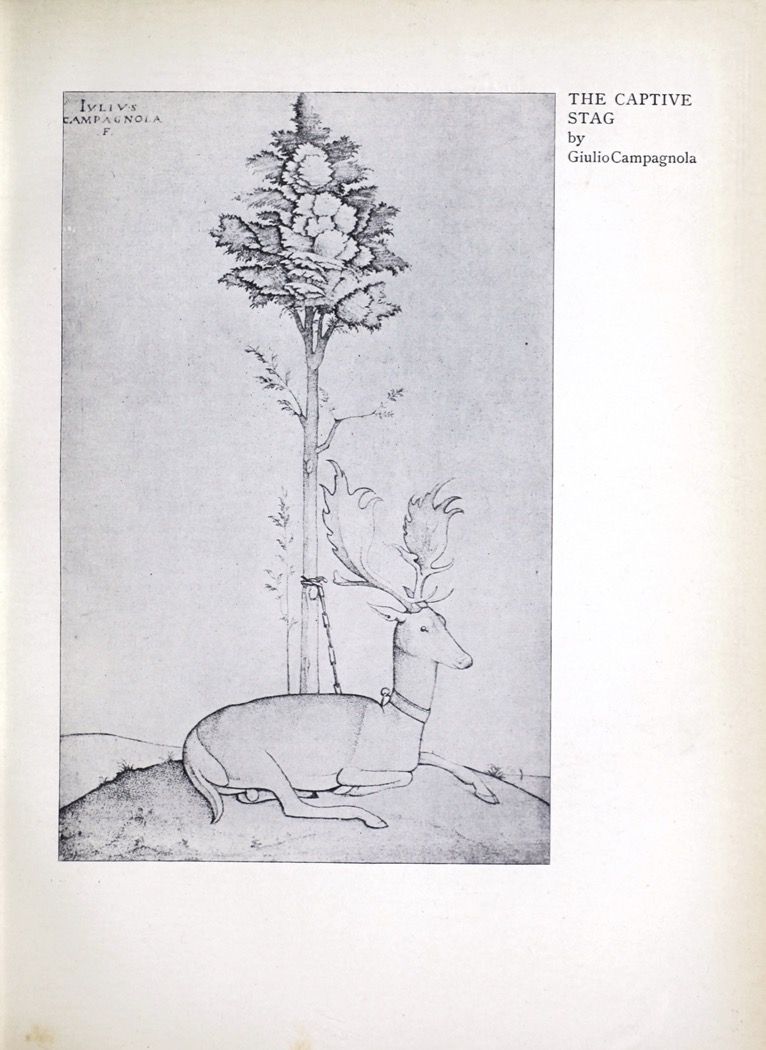

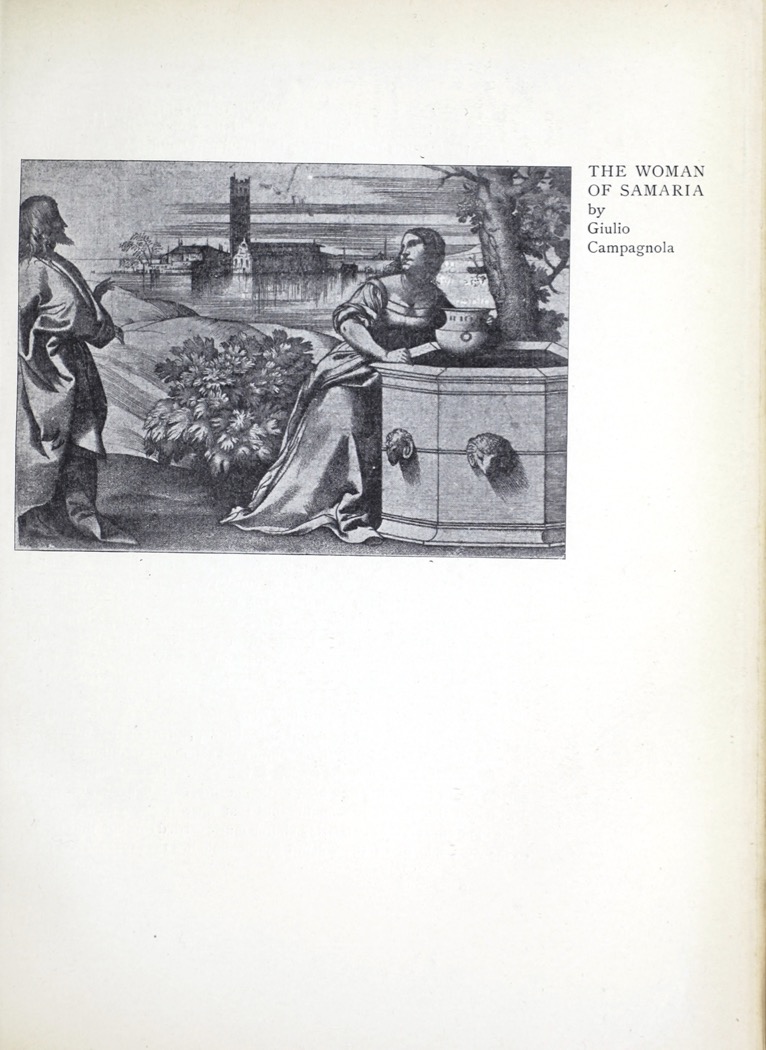

GIULIO

CAMPAGNOLA . . . . . . .

D. S.

MacColl 136

YAI AND THE

MOON . . . . . . . . Max

Beerbohm 143

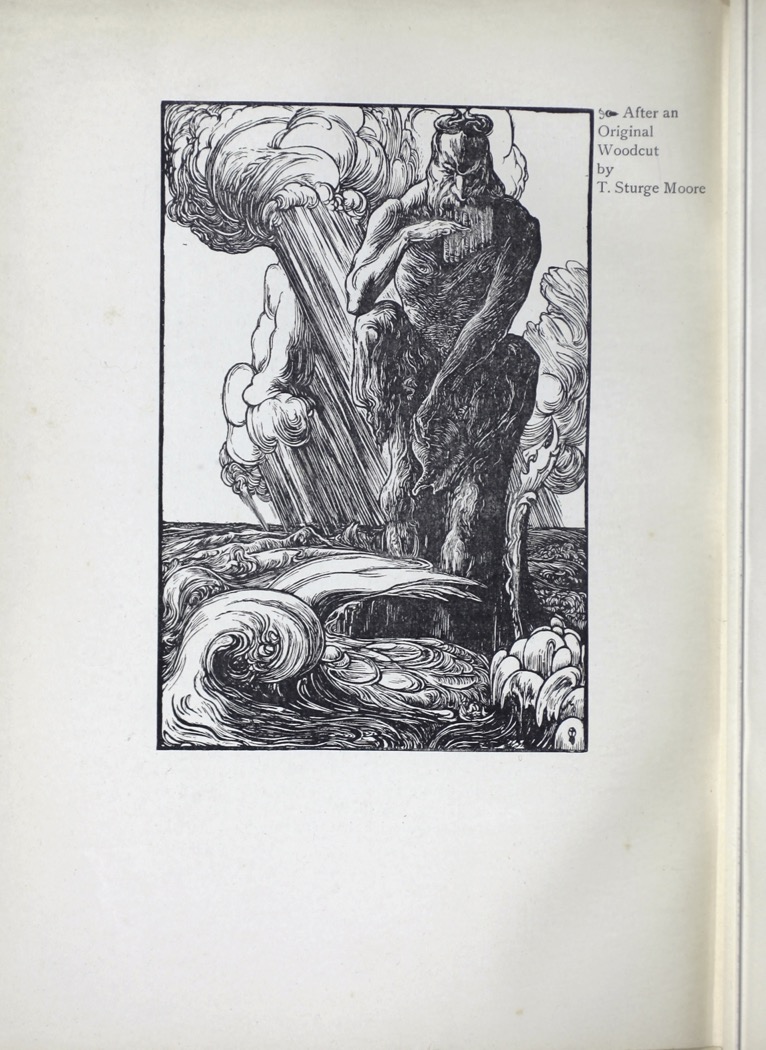

TO AN EARLY SPRING

DAY . . . . . T. Sturge

Moore 156

THE SEVEN

PRINCESSES . . . . Maurice

Maeterlinck 163

(Translated by Alfred

Sutro)

RENEWAL . . . . . . . . . . . Michael

Field 185

VIRAGO . . . . . . . . . . W. Delaplaine

Scull 186

ANCILLA

DOMINI . . . . . . . . . Selwyn

Image 196

OF PURPLE

JARS . . .

. .

. .

. Edward

Purcell 198

THE LAGGARD

KNIGHT . . . . . . . . R.

Garnett 221

QUEEN

YSABEAU . . . . Count Villiers de

l’Isle-Adam 222

(Translated by A. Teixeira de

Mattos)

ON A BRETON

CEMETERY . . . . . . Ernest

Dowson 232

THE LILIES OF

FRANCE . . . . . . . Lionel

Johnson 233

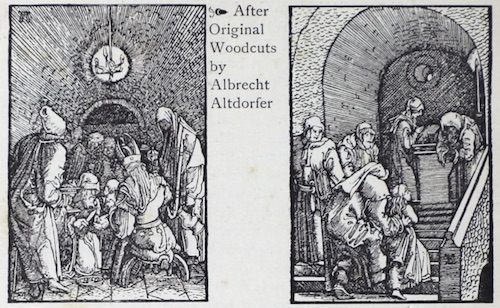

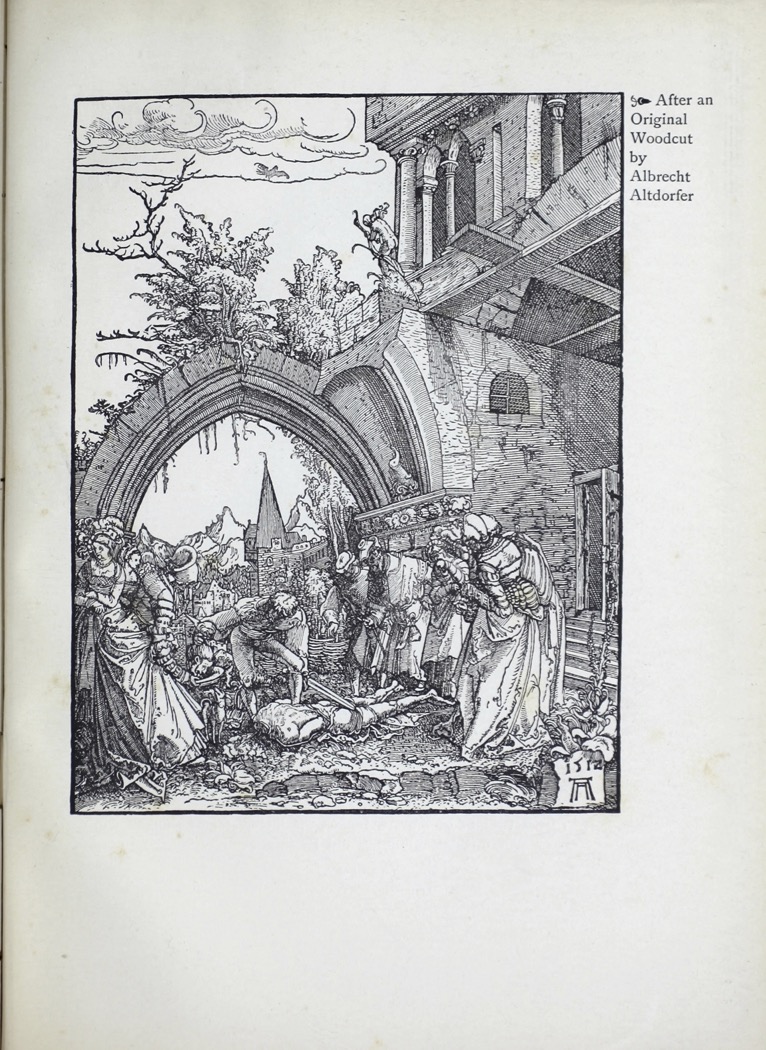

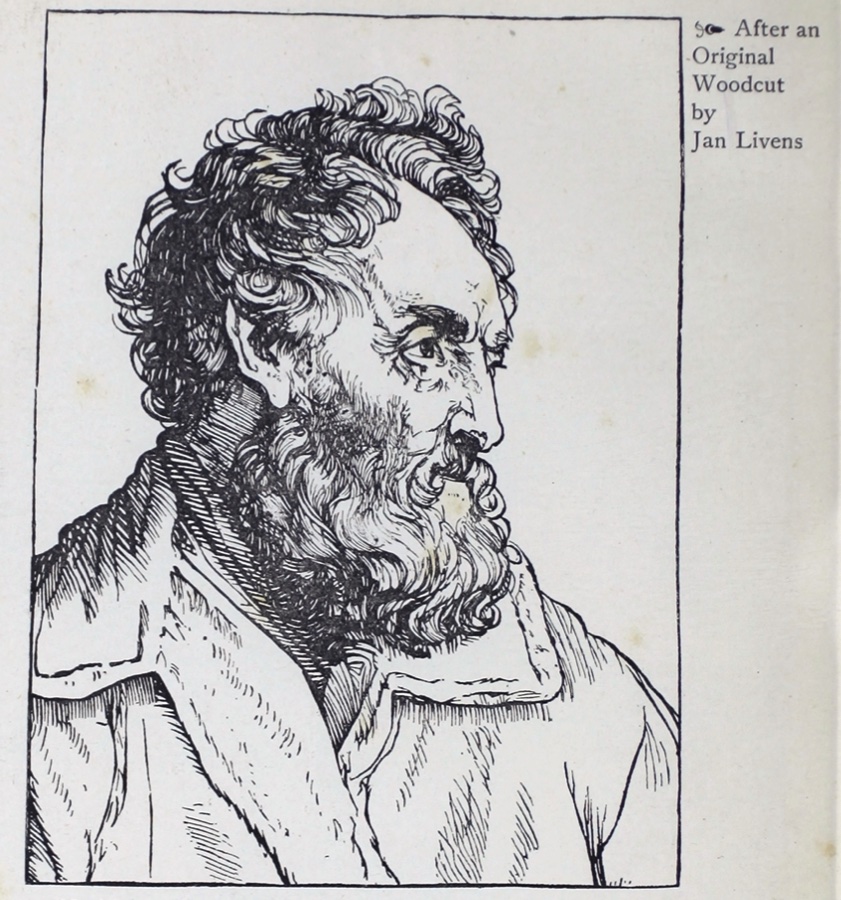

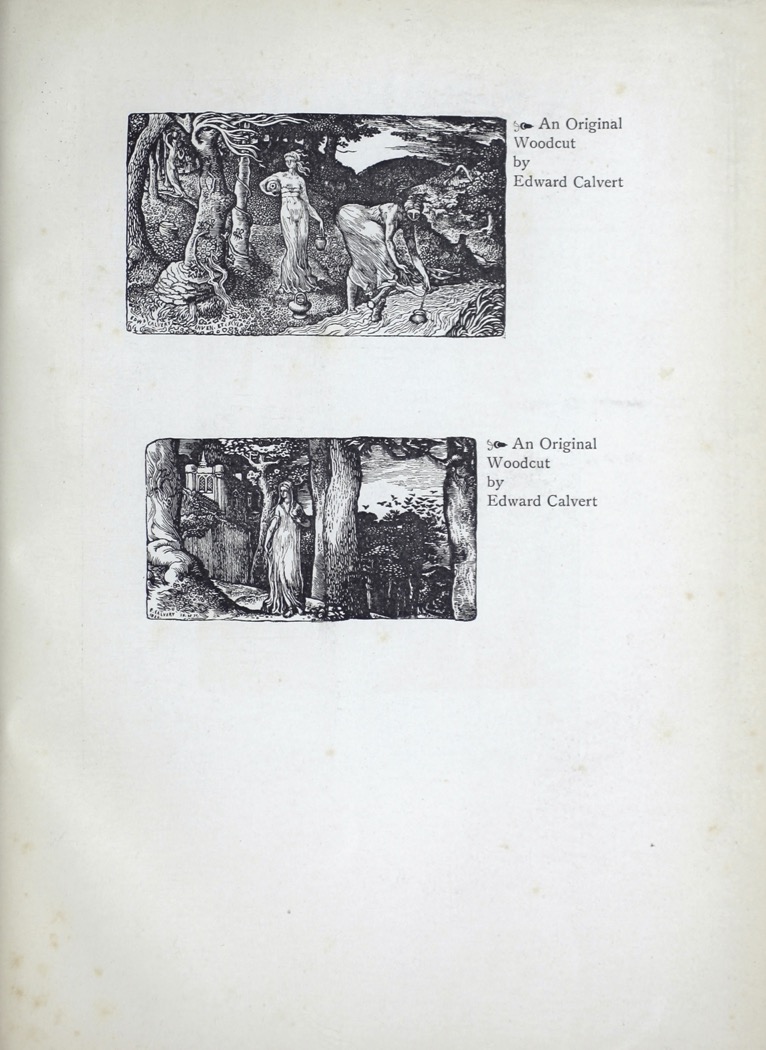

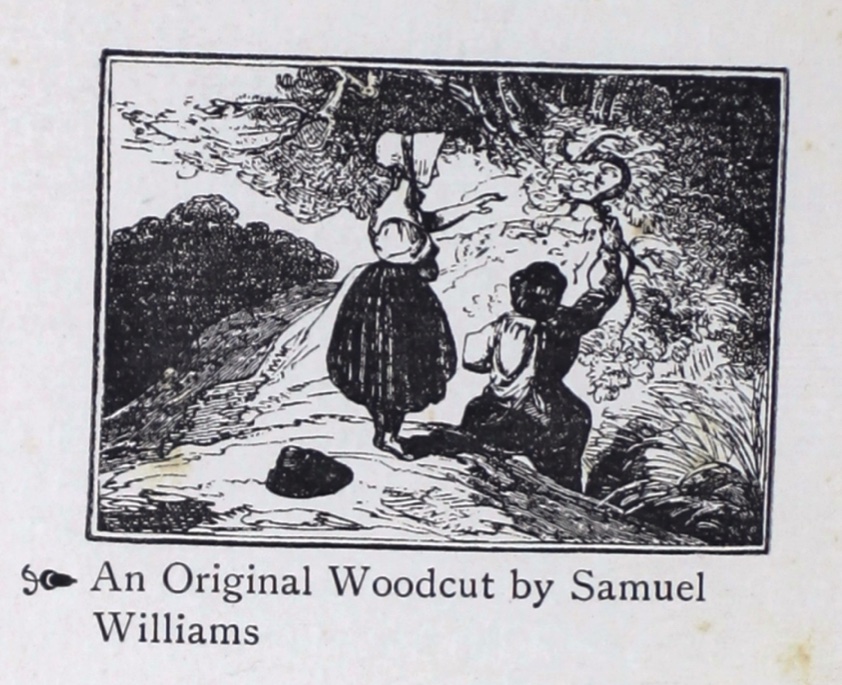

A NOTE ON ORIGINAL WOOD ENGRAVING

(illustrated) .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. Charles

Ricketts 253

❧ ART CONTENTS

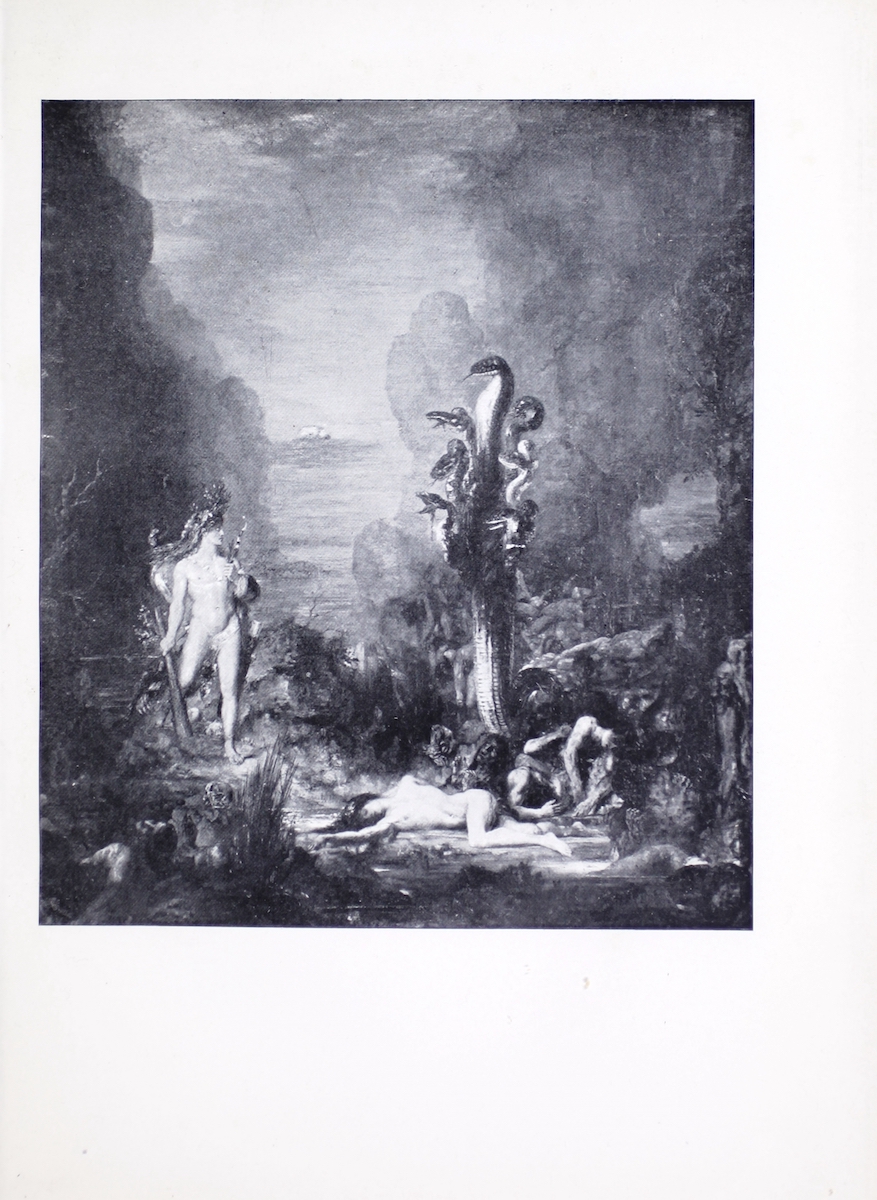

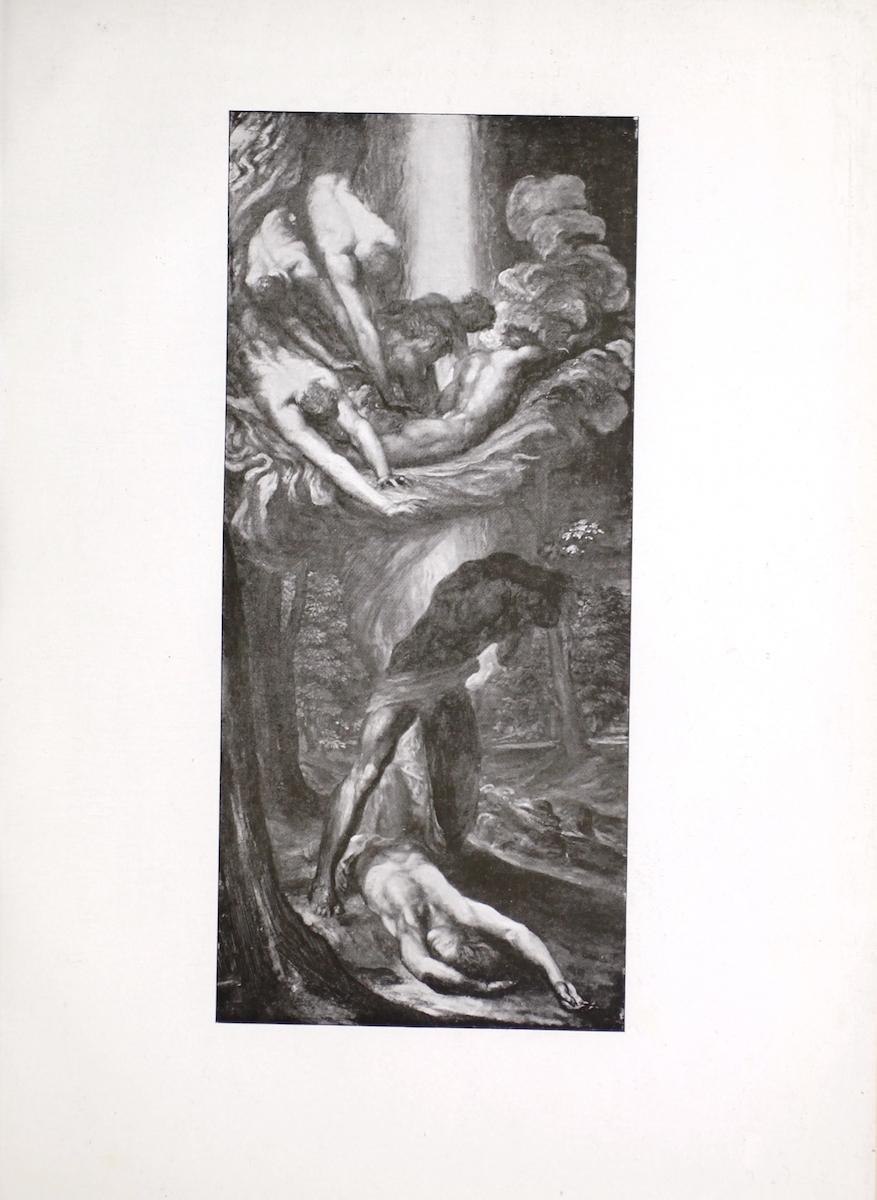

HERCULES AND THE

HYDRA . Gustave

Moreau Frontispiece

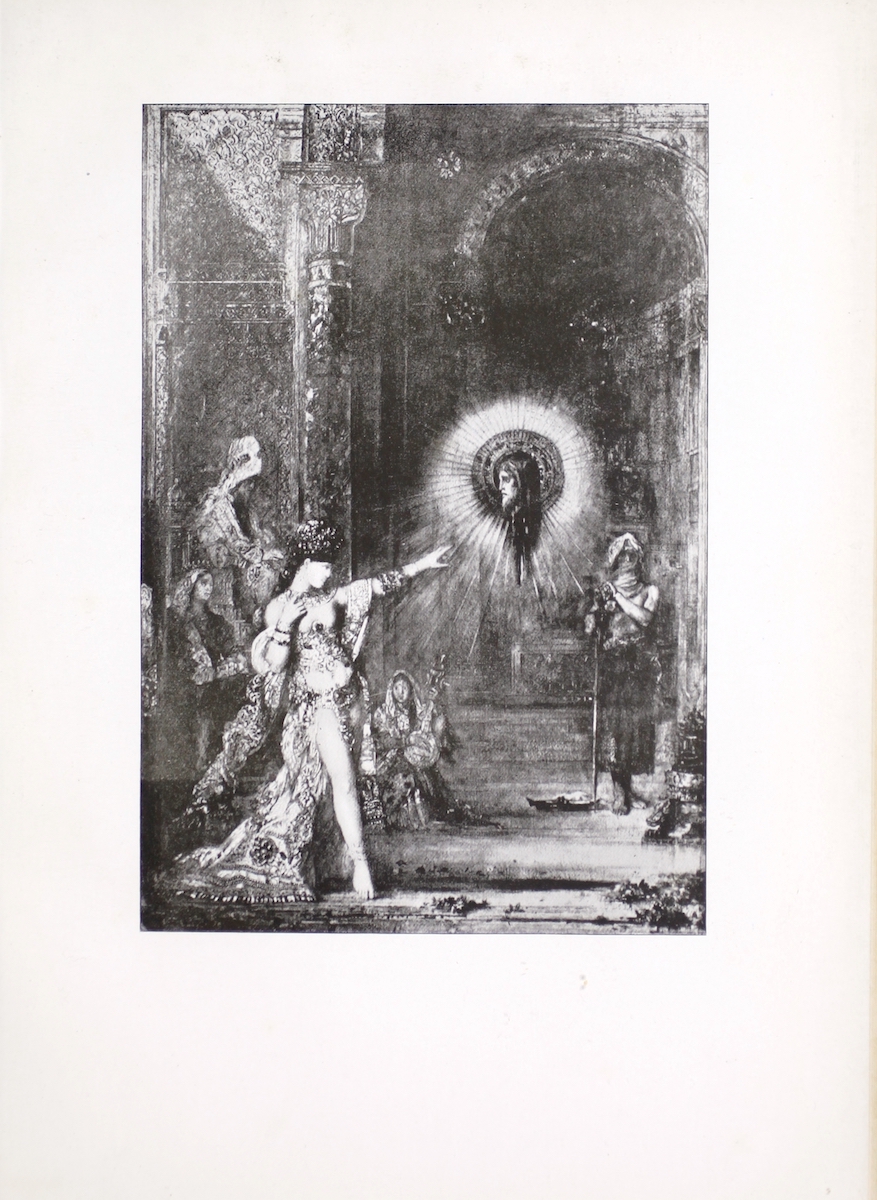

THE

APPARITION . . . . . . . . . . Gustave

Moreau 9

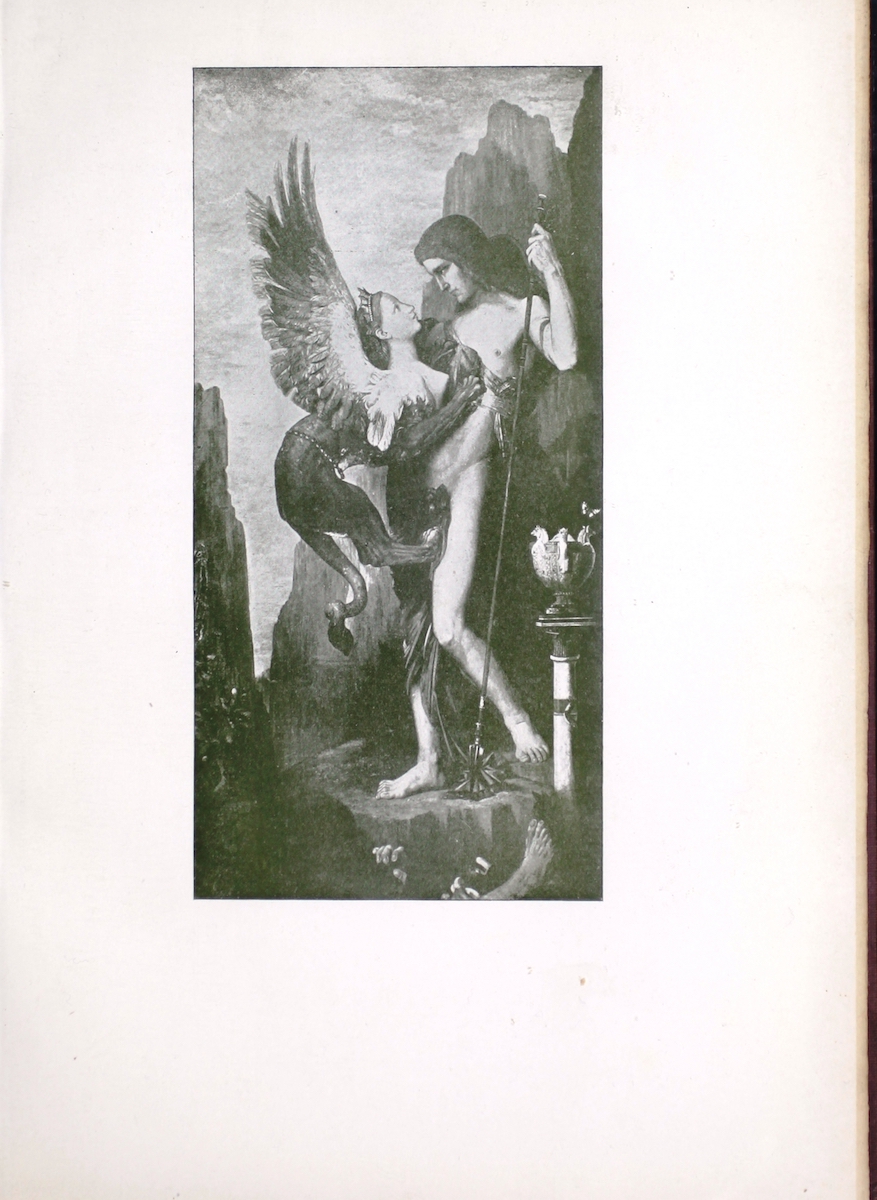

THE

SPHINX . . . . . . . .

. . . Gustave

Moreau 15

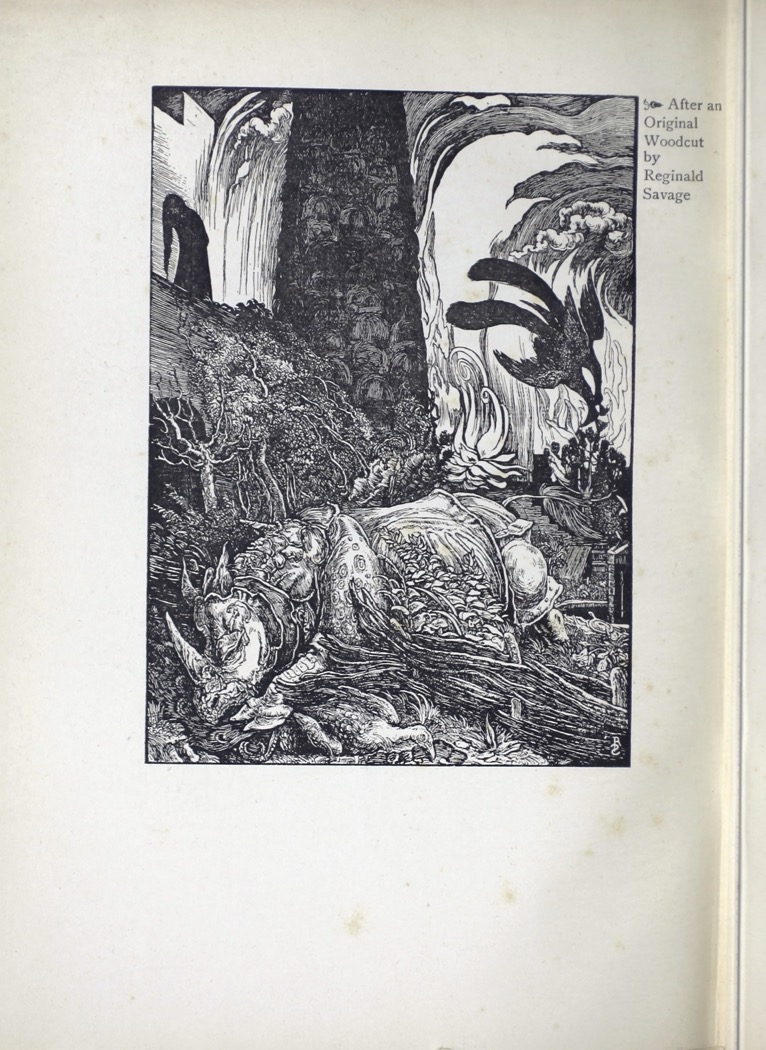

THE ANCIENT MARINER,

from a pen

drawing . . . . . . . . . Reginald

Savage 29

LA

PIA . . . . . . . . . . . Dante Gabriel

Rossetti 43

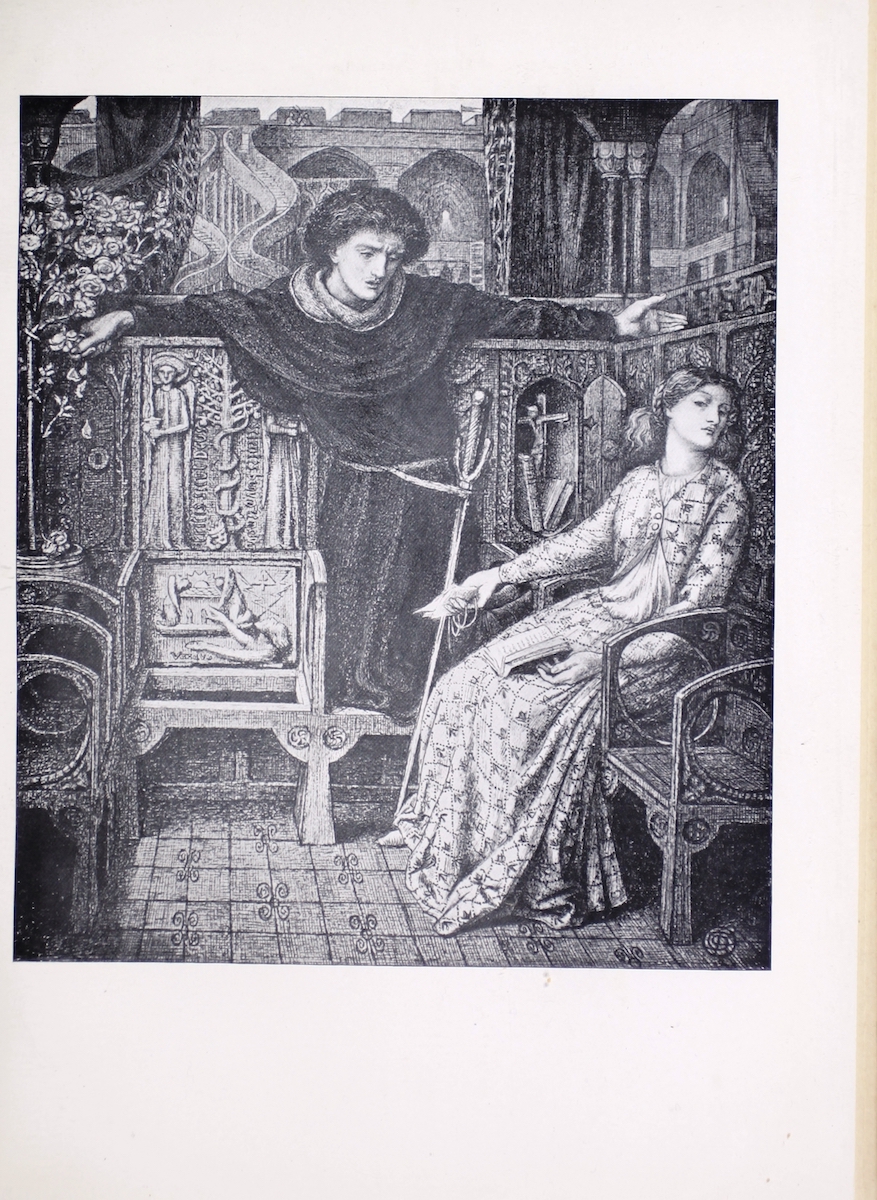

HAMLET AND OPHELIA,

from a pen

drawing . . . . . . . Dante Gabriel

Rossetti 57

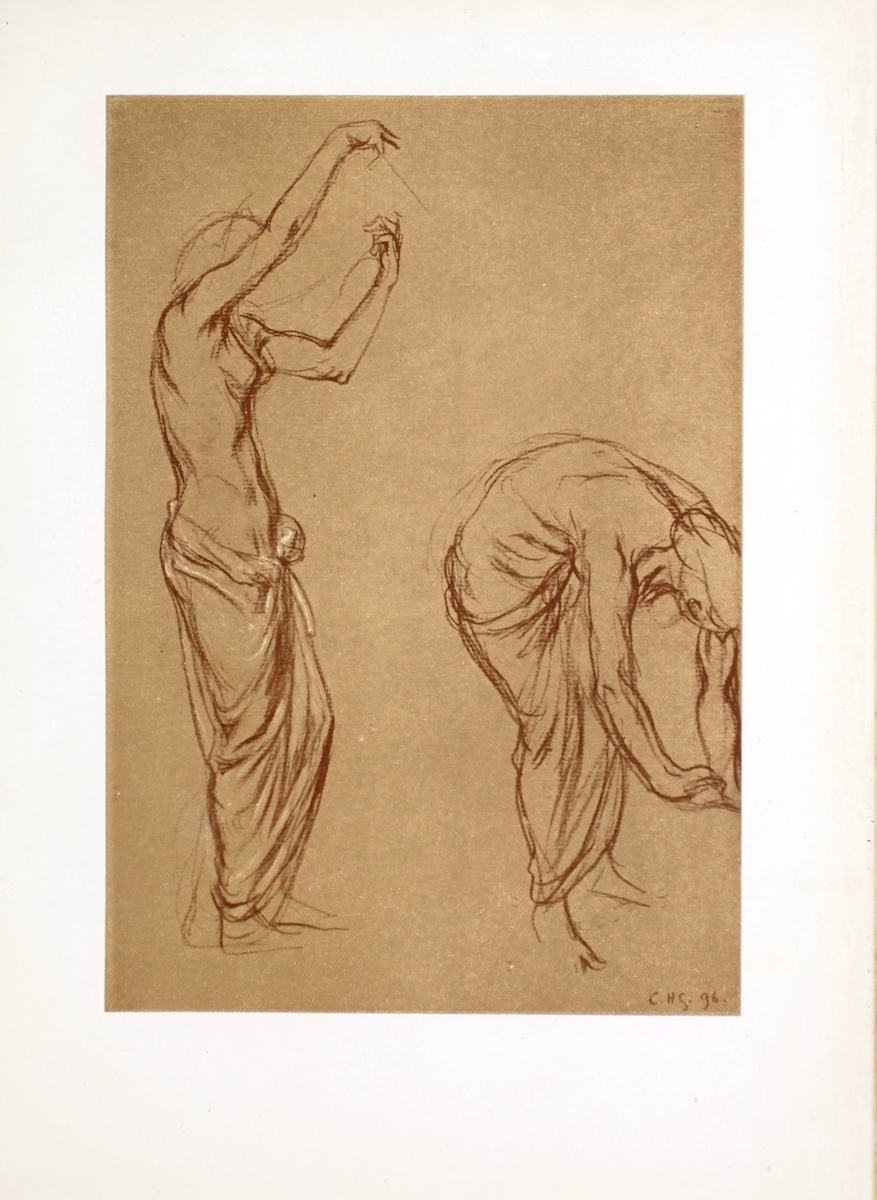

A STUDY IN SANGUINE AND

WHITE . . . . . . . . . Charles Hazelwood

Shannon

71

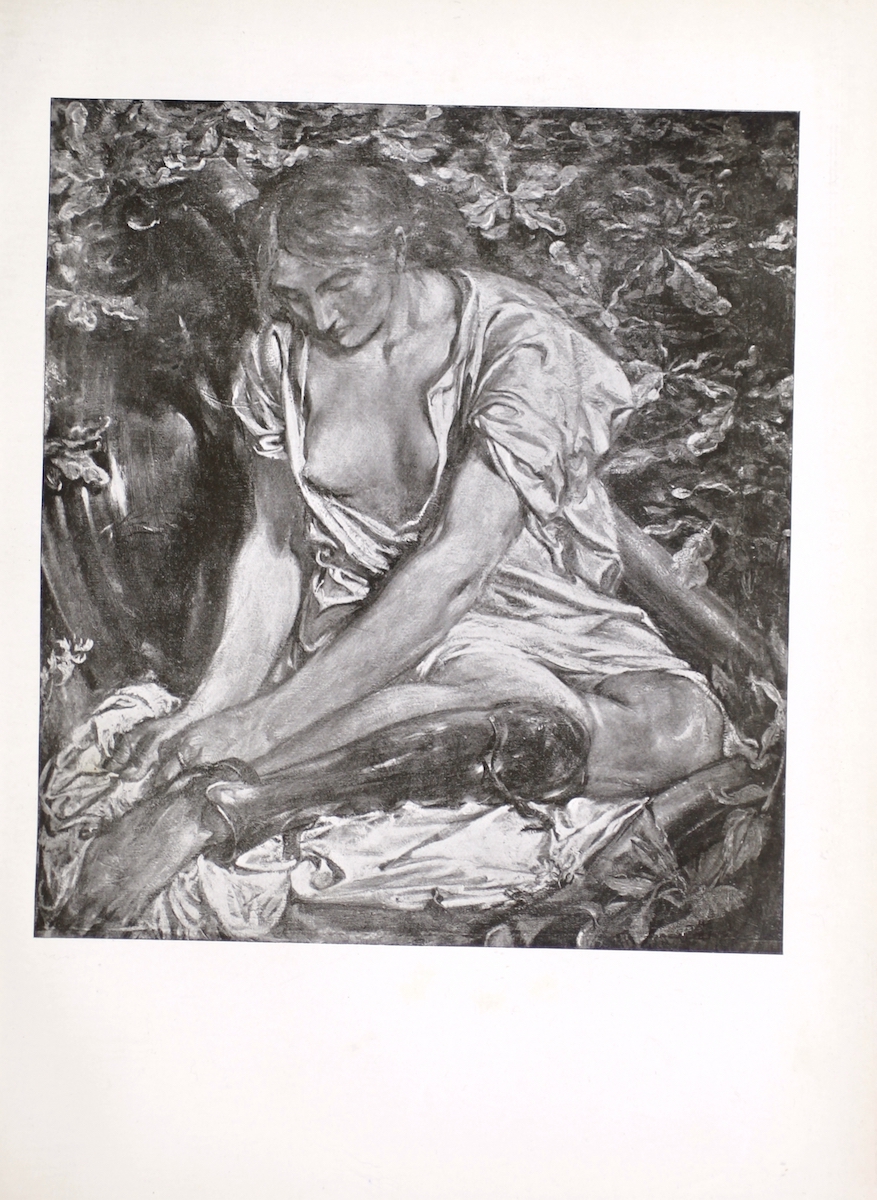

A WOUNDED

AMAZON . . . . Charles Hazelwood

Shannon 85

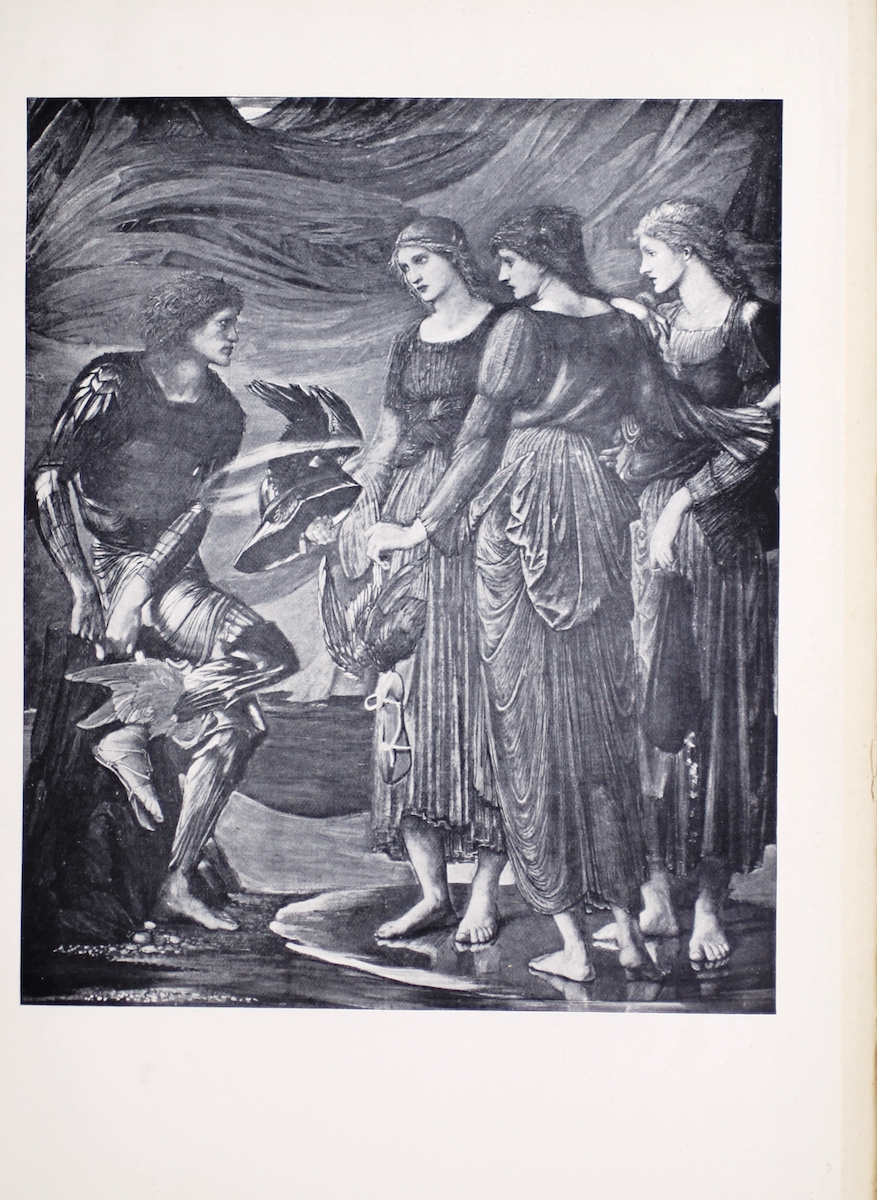

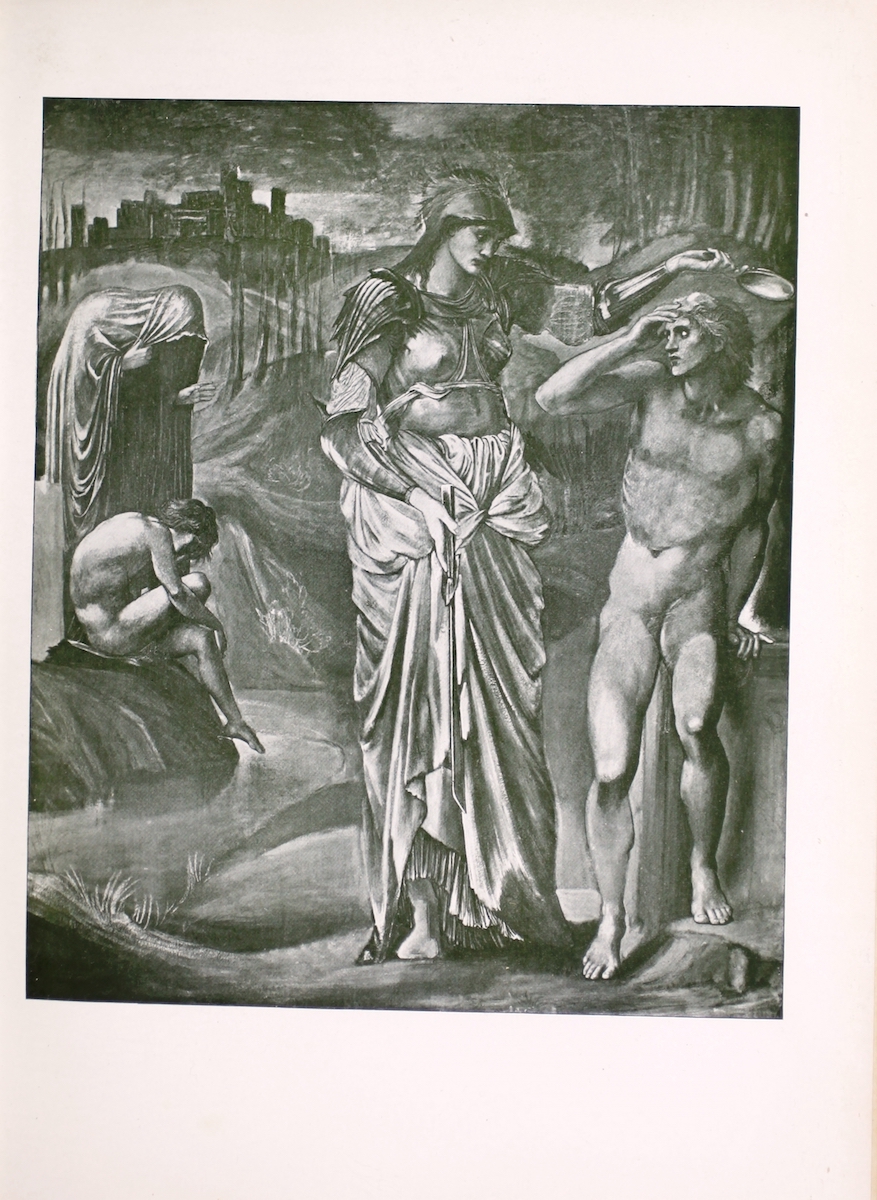

PERSEUS AND THE SEA-MAIDENS

. Sir Edward

Burne-Jones 99

THE CALL OF

PERSEUS . . . . . Sir Edward

Burne-Jones 111

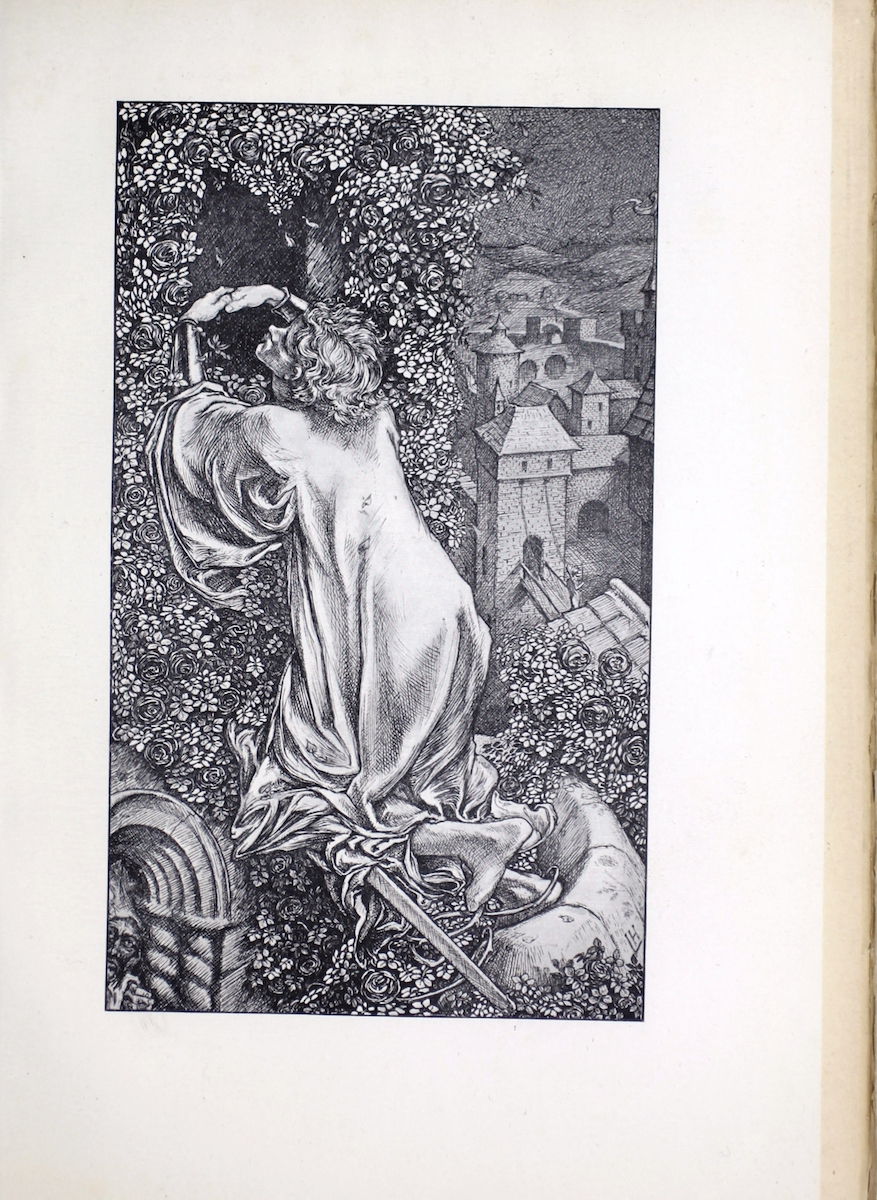

THE INVISIBLE PRINCESS,

from a pen

drawing . . . . . . . . Laurence

Housman 125

THE CAPTIVE STAG,

from an engraving . . . . . . . . . Giulio

Campagnola 135

THE WOMAN OF SAMARIA,

from an

engraving . . . . . . . . . Giulio

Campagnola 139

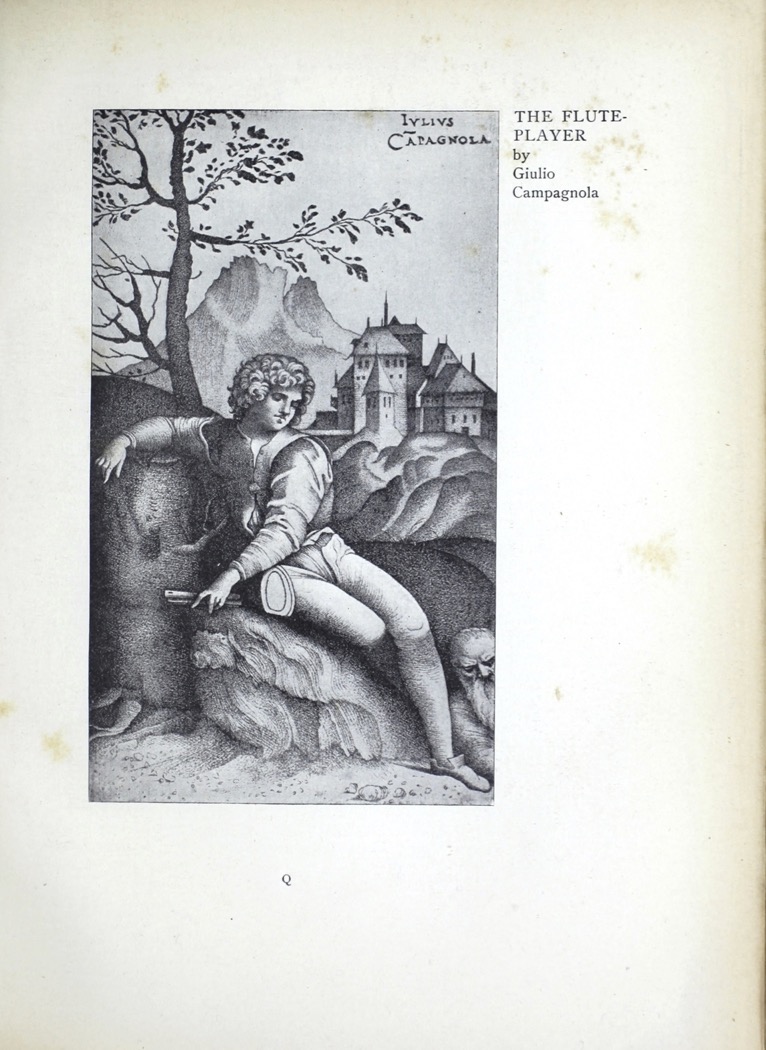

THE FLUTE-PLAYER,

from an engraving . . . . . . . Giulio

Campagnola 141

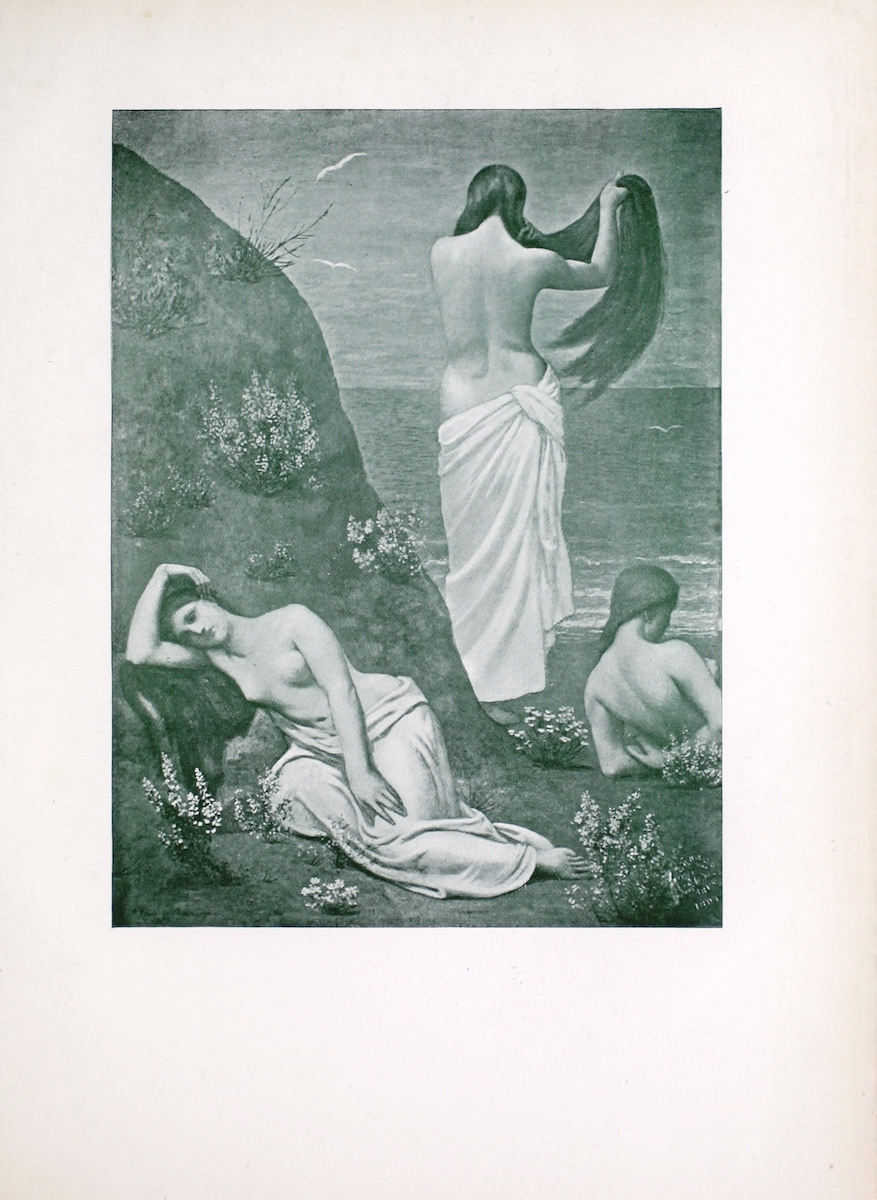

YOUNG GIRLS BY THE

SEA . . . . P. Puvis de

Chavannes 149

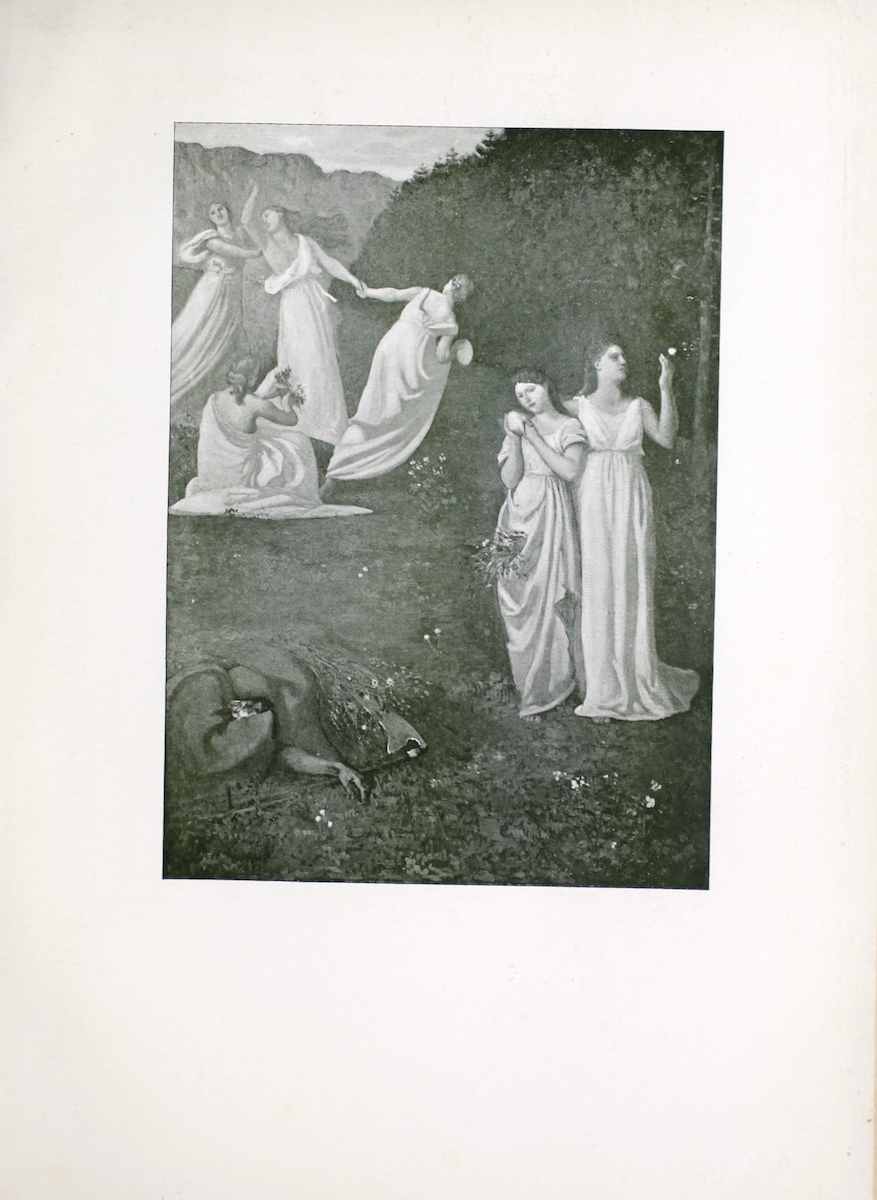

YOUNG GIRLS AND

DEATH . . . . P. Puvis de

Chavannes 161

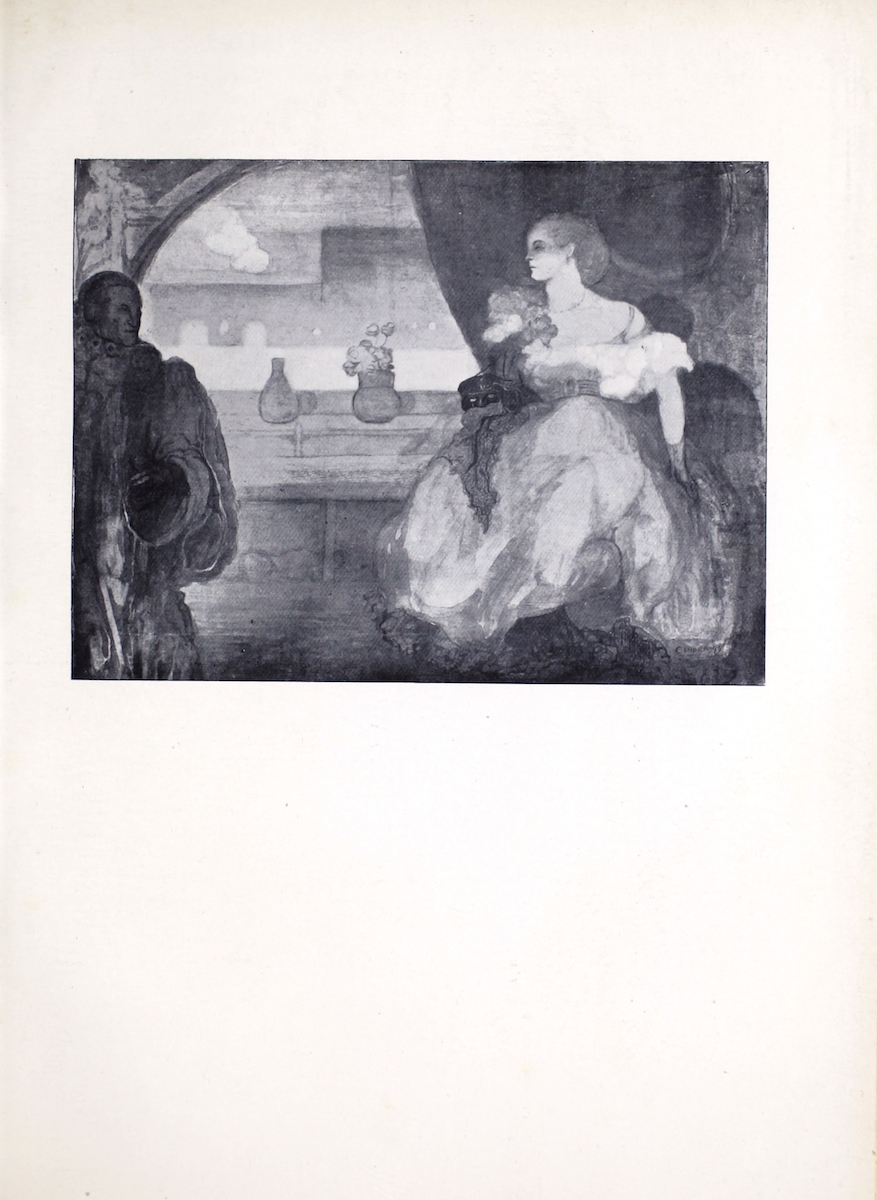

LE PREMIER BAL,

from a watercolour . . . . . . . . . Charles

Conder 173

THE DEATH OF

ABEL . . . . George Frederick Watts, R.

A. 189

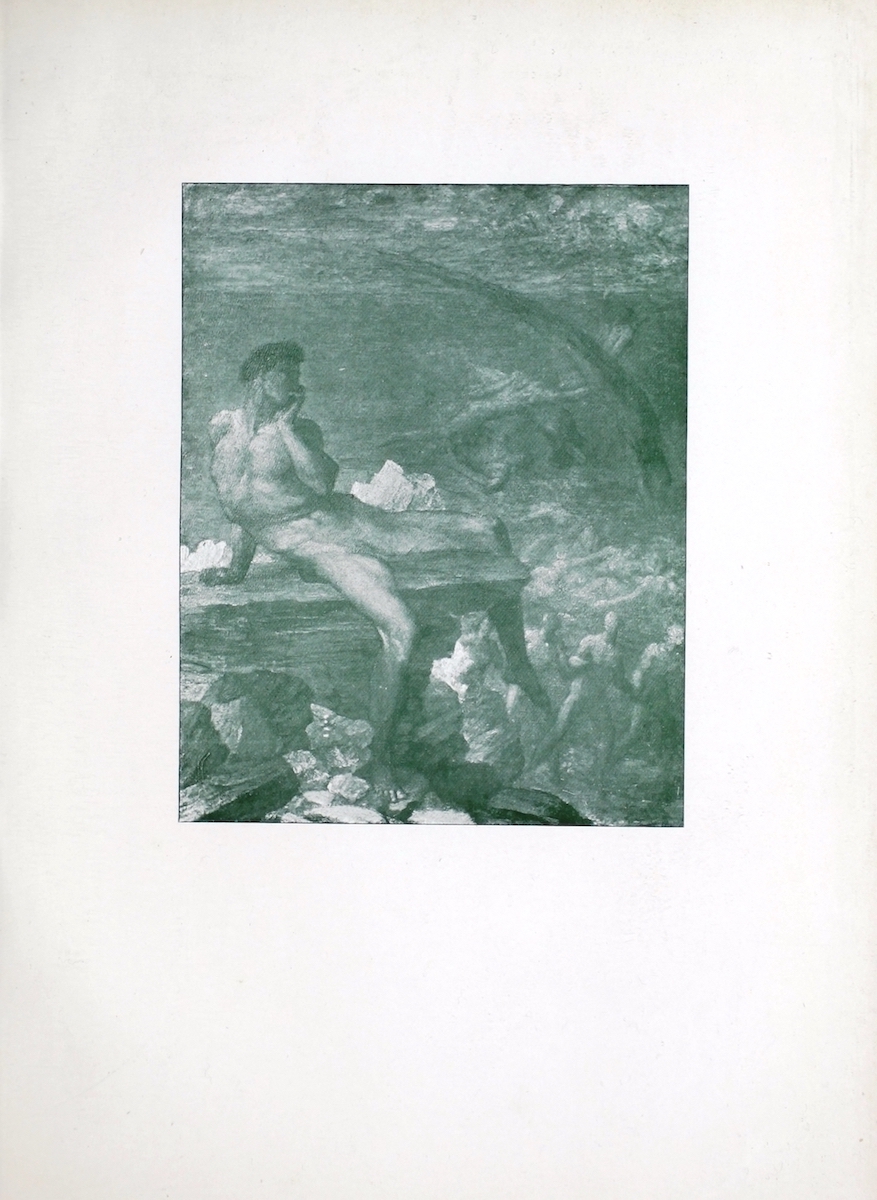

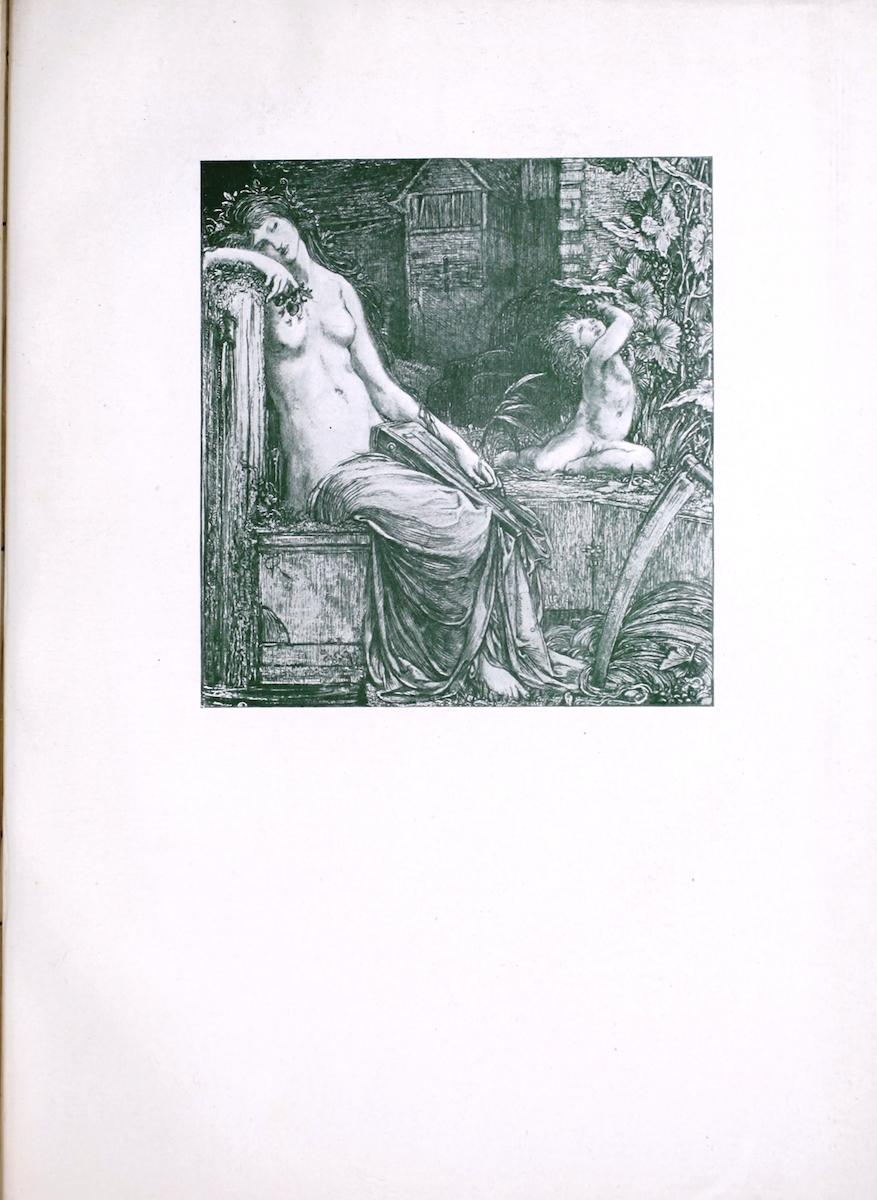

THE GENIUS OF GREEK

POETRY . George Frederick Watts, R.

A. 203

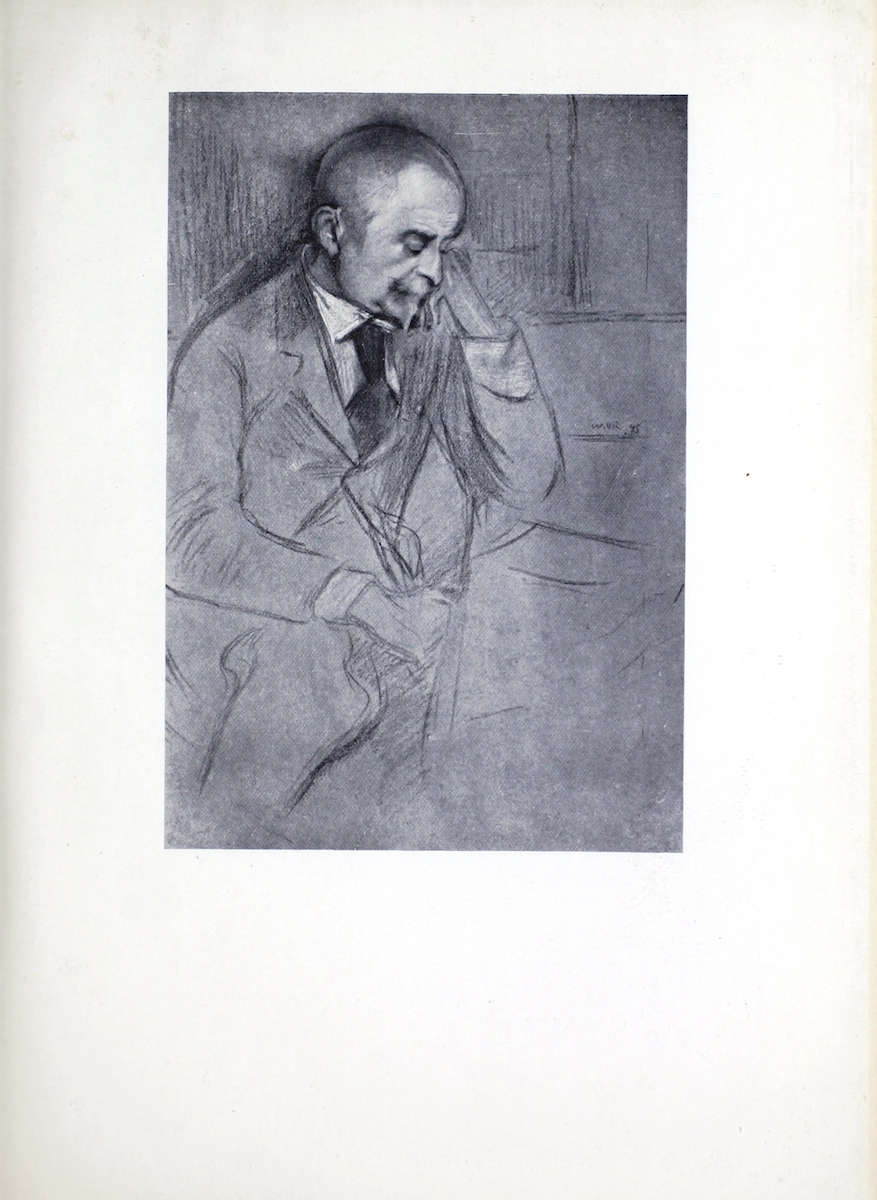

J. K.

HUYSMANS . . . . . . . . . . Will

Rothenstein 217

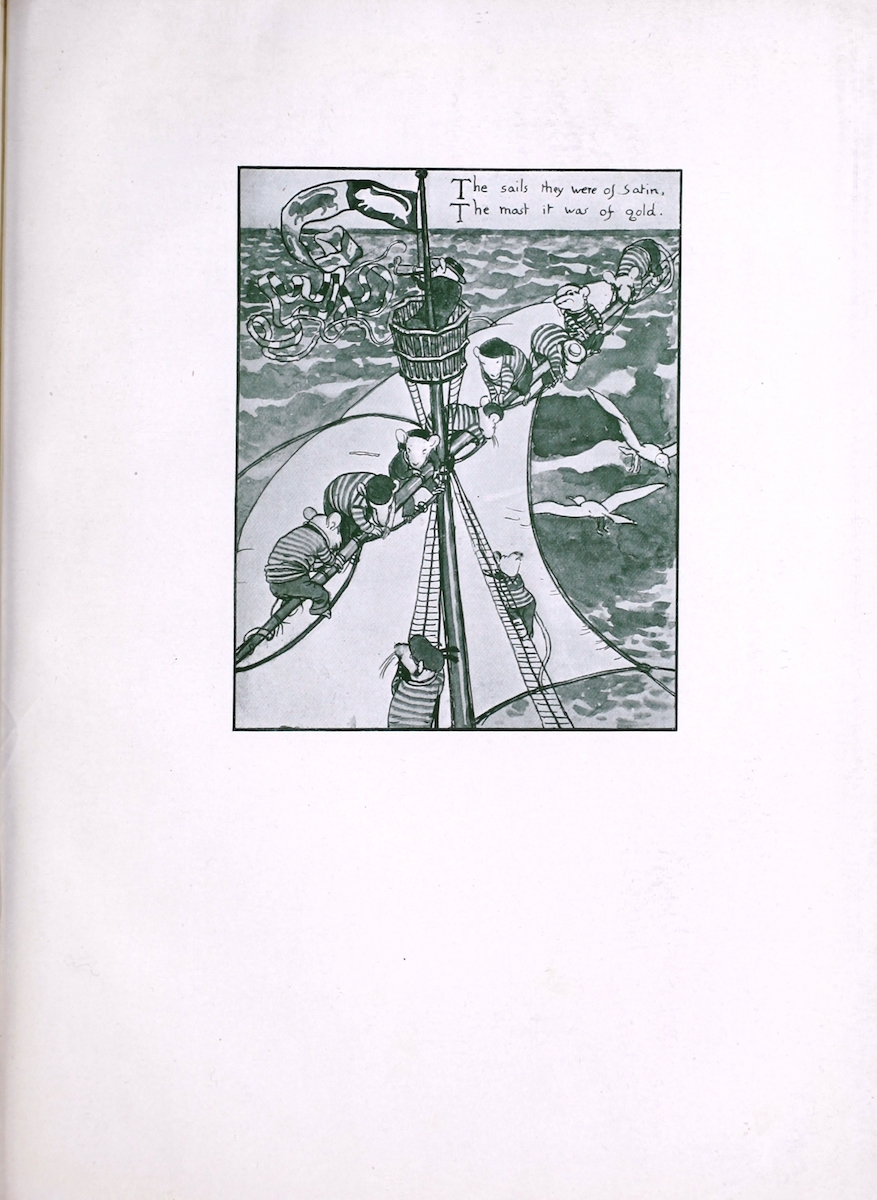

THE FAIRY

SHIP . . . . . . . . . . . Walter

Crane 229

THE

BATHERS . . . . . . . . . . . William

Strang 243

THE AUTUMN

MUSE . . . . . . . . Charles

Ricketts 251

THE QUEEN OF THE FISHES,

a woodcut in five

blocks . . . . . . . . Lucien

Pissarro 259

Advertisements

A Selection from Messrs Henry & Co’s

Publications [i-viii]

Ad for: Marcus Ward &

Co [vi]

The List of Books Published by

Messrs Hacon and Ricketts at the Sign of the Dial [vii]

Ad for: Swan Electric Engraving

Company [ix]

❧ A POSTSCRIPT TO ‘RETALIATION’

[After the fourth edition of Dr. Goldsmith’s Retaliation was printed, the publisher

received a supplementary epitaph on the wit and punster, Caleb Whitefoord. Though

it is found appended to the later issues of the poem, it has been suspected that

Whitefoord wrote it himself. It may be that the following, which has recently come

to light, is another forgery.]

Here JOHNSON is laid. Have a care how you walk;

If he stir in his sleep, in his sleep he will talk.

Ye gods! how he talk’d! What a torrent of sound

His hearers invaded, encompass’d, and—drown’d!

What a banquet of memory, fact, illustration,

In that innings-for-one that he call’d conversation!

Can’t you hear his sonorous ‘Why no, sir!’ and ‘Stay, sir!

Your premiss is wrong,’ or ‘You don’t see your way, sir!’

How he silenc’d a prig, or a slip-shod romancer!

How he pounc’d on a fool with a knock-me-down answer!

But peace to his slumbers! Tho’ rough in the rind,

The heart of the giant was gentle and kind:

What signifies now, if in bouts with a friend,

When his pistol miss’d fire, he would use the butt-end 1

If he trampled your flow’rs—like a bull in a garden—

What matter for that? he was sure to ask pardon;

And you felt on the whole, tho’ he’d toss’d you and gor’d you,

It was something, at least, that he had not ignor’d you.

Yes ! the outside was rugged. But test him within,

You found he had nought of the bear but the skin; 2

And for bottom and base to his ‘anfractuosity,’

A fund of fine feeling, good taste, generosity.

He was true to his conscience, his King, and his duty,

And he hated the Whigs, and he softened to beauty.

Turn now to his writings. I grant, in his tales,

That he made little fishes talk vastly like whales; 3

I grant that his language was rather emphatic,

Nay, even—to put the thing plainly—dogmatic;

But

❧ Read for the author, by the Master of the Temple, at the dinner of the ‘Johnson Society’

in Pembroke College, Oxford, on the 22nd June of 1896.

1. Goldsmith said this of Johnson. 2. Goldsmith also said this. 3. And this.

But read him for style, and dismiss from your thoughts

The crowd of compilers who copied his faults, 1

Say, where is there English so full and so clear,

So weighty, so dignified, manly, sincere?

So strong in expression, conviction, persuasion?

So prompt to take colour from place and occasion?

So widely removed from the doubtful, the tentative;

So truly—and in the best sense—argumentative?

You may talk of your Burkes and your Gibbons so clever

But I hark back to him with a ‘Johnson for ever!’

And I feel as I muse on his ponderous figure,

Tho’ he’s great in this age, in the next he’ll grow bigger;

And still while his Pembroke takes sunlight upon her,

New dons shall assemble, and dine in his honour!

AUSTIN DOBSON.

1. These, or like rhymes, are to be found in Edwin and Angelina and in Retaliation itself.

THE PICTURES OF GUSTAVE MOREAU

WHO has not suffered under the tyranny of

an insistent phrase from the street song of

the moment? or from the reiteration of a

foolish phrase? ‘The French Burne-Jones,’

for instance, is one that will intrude when

Moreau is mentioned. Such an inept com-

parison is degrading to both painters, and its

ghost must be laid. To apply a geographical

adjective to an artist is always a fatuous

substitute for criticism. A Belgian Shakespeare or a French Burne-

Jones—how pitifully meaningless each phrase is seen to be when you

face it boldly. For the essence of Burne-Jones is that he is Northern,

and of Moreau that he is Latin.

A Frenchman looks to the East through Rome; whether his gaze be

fixed on theology or art, he sees it through the atmosphere of the eternal

city. An Englishman regards Rome as an episode, and sometimes for-

gets even whether Greece inspired the Latins, or vice versâ. For Rome

to a Briton is not the outpost of his frontier whence he emerges in quest

of the dim past; it is not the beginning of his to-day, but one of the

twilights of dead yesterdays. He may travel to the Orient, whose

frontier is Greece, by sea; or, through the haunted forests of Germany

and down the Danube. His East is linked to him not by the Caesars,

nor the Popes, but by the Crusaders. His myths of Hellas reach

him more often by way of Chaucer or William Morris. That Venus

should masquerade as Our Lady of Pain, clad in broideries of mediæval

fashion, seems to him natural enough. Not so the Frenchman, who,

Latin by race, is still Latin in heart, and regards far off Greece and

more distant Egypt as the direct artistic progenitors of his forefathers

the Romans, by whom he claims a clear pedigree through the masters

of classic times, back to the East, the birthplace of knowledge.

Recognising this sharply defined distinction, you may trace the

art of Burne-Jones and Moreau to the same fountain-head, and find in

the brooding East the mother of all the mysteries each delights to re-

edify; but the two streams only meet at the source. Over the waters

of the one still hangs the heavy-scented incense cloud of the Middle

Ages; the other flows azure and sparkling from springs fed by the dews

from the mystic rose of Persia, from lotus-pools of Ind, and from

Hellenic brooks wherein Narcissus gazed.

For Moreau is the classic ideal, which is scholarly simplicity; al-

though

6

l’Ange, St. Etienne, un Calvaire, une Déposition de Croix, Ensevelissement

du Christ, and the biblical pictures, Salomé, David, Bethsabée.

To these may be added the series of designs for the fables of La

Fontaine which were admirably described in an illustrated paper in The

Magazine of Art.1 Reproductions of these sixty-four water-colours

nominally intended to illustrate La Fontaine are not yet accessible in

volume form, but many single pictures have been admirably etched by

Bracquemond. Mr. Claude Phillips sees in them a distinctly strong trace

of Persian influence, which, unlike Japanese, does not concern itself

with the purely exterior manifestation of humanity and the outer

world, but is distinguished by supreme calm, devoid of violent action,

assisted by a severe life and tempered passions. Possibly it would be

still more accurate to call this influence Hindoo-Greek, for although

both sprang, doubtless, from the same source, it is the latter develop-

ment which Moreau feels. But in the exquisitely delicate tracery and

jewelled embroideries, that preserve a certain reticence in their splen-

dour, there is kinship to Persian fantasy. The text of La Fontaine,

with its beasts masquerading as men, its prim moralities and fossil anec-

dotes, fettered Moreau, who seems at times to have wearied of the effort.

The Head of Orpheus, which Ary Renan describes so charmingly,

has found an English critic, whose impression is so vividly expressed

that it were folly to try to put the idea in other words: ‘It is against

skies flushed by an aftermath of sun that recall for their touches of

orange and bands of brooding purple these words, Quelles violettes

frondaisons vont descendre—words so expressive of that hush in nature

become strange in expectation of some countersign pregnant for the

future—it is against a sky like this,’ he says, ‘that an all-persuasive

figure moves away; the head of Orpheus lies between her hands, and we

scarcely know if her fastidious dress, decked with so many outlandish

things, has been clasped to her waist and chaste throat in real

innocence of the burden she holds so mystically; but this hint of

sentiment is too slight, too fugitive, in the picture to become morbid.’

In The Birth of Venus, not included in M. Ary Renan’s list, we note

a curious influence of Pompeii. The figure of Venus, in the foreground,

floats in a shell, by way of boat, scarce conscious of the clamorous

worshippers on the distant beach who would fain attract her gaze;

through a cleft in the fantastic walls of rock that bound the coast you

catch a glimpse of a lovely country.

In

1. Vol. x. 101

❧ THE APPARITION

by

Gustave Moreau

11

In the Hercules and Hydra, the central figure is, like that of the

Venus, singularly removed from the gross physical type so dear to

certain schools. It is a divine, not a fat Hercules; and the reality of the

monster terrifies one. The colouring of the picture—dark green with

blood-red in the sky and upon the ground—imparts a grim sense of

awe. The third picture illustrated, the Apparition, is strangely like

the Salome Dancing in its composition. In each the chief figure

stands to the left of the spectator; in each a silent warrior with his

mouth swathed in heavy drapery gazes mutely impassive; in each,

huge arches rise profound and mysterious; but apart from mere similarity

of composition the motif of either is utterly distinct. In the Apparition

the figure of Herod is at the side scarce noticeable. The tragedy is

but indirectly concerned with him; it is the instigator who is con-

founded by the spectral and transfigured head that rivets the attention

of one who sees the painting, no less than it appals the chief actor,

who is alone moved by the portent. In the Salome Dancing, the white

lily she holds as a sceptre seems to heighten the meaning of her

sorcery. The hanging lamps and the cathedral-like aspect of the vast

Asiatic interior, the brooding Herod who sits enthroned with grotesque

monsters in a hellish trinity above him, all assist to make the scene

suggest an impious travesty of the religion that was destined to

enshrine the incident. So stern is the purpose that not at first do you

realise the wealth of imagery which has been encrusted upon the

idea, or rather the complexity of aspect which the idea itself has

assumed in Moreau’s conception.

To describe in catalogue the works of Gustave Moreau already

mentioned would serve no purpose. If any one interested in his paint-

ing is unable to gain access to the pictures—and as they are mostly in

private hands it is extremely difficult to do so—he will find in the

various periodicals already mentioned descriptions of the most important.

In A Rebours, Huysmans has spoken at some length of the Apparition,

which was shown in England at the first Exhibition at the Grosvenor

Gallery. The story of Salomé has had a most lasting fascination for

Moreau. A third picture—a wonderful water-colour, that so far appears

to have escaped reproduction—which shows Salome returning with the

head of John the Baptist on a charger, conveys the same poetic under-

current we see in the Head of Orpheus. It is an echo of Heine’s terrible

Salomein Alta Troll.

Of

1. A Rebours, pp. 74, 79

12 Of the Young Man and Death, with its ascription to Chassériau, of

the Plainte du Poète, reproductions are given in the Gazette des Beaux

Arts, and elsewhere; but none of these do more than suggest and

then only to those familiar with the originals—the scheme of colour

which Moreau usually employs. His favourite harmony is in blues

verging on peacock, merging into dark green, with rather hot browns

and a liberal use of crimsons and old-gold colour. The flesh tones are

inclined to be cadaverous; the draperies are often polychromatic, not

‘shot’ like those of Burne-Jones, but in layers of different hues.

Bowers of clipped foliage, the lotus, the iris, and gum-cistus, lilies and

roses, branches of coral and sea-plants, are frequent accessories. As

Burne-Jones loves to depict metals, so Moreau delights in enamelled

surfaces. To attempt to convey his manner in a sentence is not easy;

perhaps to say that he is a cross between Mantegna and Delacroix

might convey some idea of his colour, but his blues are quite unlike

those of either master.

But this chance comparison with Burne-Jones is merely for explana-

tory purposes. For to appreciate one painter by linking him with

another—the eternal match-making of the elderly—is at once a failure

and an unintentional insult. The one distinct patent of nobility for an

artist is that he shall hide a superb pedigree by the still more noble

title won by his own prowess. The more you study Moreau, the more

you feel he owes his manner, his style, his entire art, to Moreau and

Moreau only. In a distinctly limited manner he is not merely

supreme, but an autocrat with no power behind the throne. The

new personality of his invention is more and more apparent as you

attempt to discover the real artist. Like all princes he may employ

the universal language of courts, but he speaks as unreservedly as a

democrat; he does not hunt like Flaubert for the exact adjective, nor

weary himself by constant self-criticism. But the language he uses,

whether polished by the master of the past or created for his own

purpose, is strangely pregnant.

JULY

THERE is a month between the swath and sheaf

When grass is gone

And corn still grassy,

When limes are massy

With hanging leaf

And pollen-coloured blooms whereon

Bees are voices we can hear,

So hugely dumb

The silent month of the attaining year.

The white-faced roses slowly disappear

From field and hedgerow, and no more flowers come:

Earth lies in strain of powers

Too terrible for flowers:

And would we know

Her burthen we must go

Forth from the vale, and, ere the sunstrokes slacken,

Stand at a moorland’s edge and gaze

Across the hush and blaze

Of the clear-burning, verdant, summer bracken;

For in that silver flame

Is writ July’s own name.

The ineffectual, numbed sweet

Of passion at its heat.

1894 MICHAEL FIELD

JULES BARBEY D’AUREVILLY

THOSE who can endure an excursion into the

backwaters of literature may contemplate,

neither too seriously nor too lengthily, the

career and writings of Barbey d’Aurevilly.

Very obscure in his youth, he lived so long,

and preserved his force so consistently, that

in his old age he became, if not quite a

celebrity, most certainly a notoriety. At

the close of his life—he reached his eighty-

first year— he was still to be seen walking the streets or haunting

the churches of Paris, his long, sparse hair flying in the wind, his

fierce eyes flashing about him, his hat poised on the side of his

head, his famous lace frills turned back over the cuff of his coat,

his attitude always erect, defiant, and formidable. Down to the

winter of 1888 he preserved the dandy dress of 1840, and never

appeared but as M. de Pontmartin has described him, in black satin

trousers, which fitted his old legs like a glove, in a flapping, brigand

wideawake, in a velvet waistcoat, which revealed diamond studs and a

lace cravat, and in a wonderful shirt that covered the most artful pair of

stays. In every action, in every glance, he seemed to be defying the

natural decay of years, and to be forcing old age to forget him by dint

of spirited and ceaseless self-assertion. He was himself the prototype

of all the Brassards and Misnilgrands of his stories, the dandy of

dandies, the mummied and immortal beau.

His intellectual condition was not unlike his physical one. He was

a survival—of the most persistent. The last, by far the last, of the

Romantiques of 1840, Barbey d’Aurevilly lived on into an age wholly

given over to other aims and ambitions, without changing his own

ideals by an iota. He was to the great men who began the revival,

to figures like Alfred de Vigny, what Shirley was to the early Eliza-

bethans. He continued the old tradition, without resigning a single

habit or prejudice, until his mind was not a whit less old-fashioned

than his garments. Victor Hugo, who hated him, is said to have

edicated an unpublished verse to his portrait:

‘Barbey d’Aurevilly, formidable imbécile.’

But ‘imbécile’ was not at all the right word. He was absurd; he was

outrageous; he had, perhaps, by dint of resisting the decrepitude of his

natural powers, become a little crazy. But imbecility is the very last

word to use of this mutinous, dogged, implacable old pirate of letters.

Jules

19

Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly was born near Valognes (the ‘V——’

which figures in several of his stories) on the 2nd of November 1808.

He liked to represent himself as a scion of the bluest nobility of Nor-

mandy, and he communicated to the makers of dictionaries the fact

that the name of his direct ancestor is engraved on the tomb of

William the Conqueror. But some have said that the names of his

father and mother were never known, and others (poor d’Aurevilly !)

have set him down as the son of a butcher in the village of Saint-

Sauveur-le-Vicomte. He was at college with Maurice de Guérin, and

quite early, about 1830 apparently, he became personally acquainted

with Chateaubriand. His youth seems to be wrapped up in mystery;

according to one of the best informed of his biographers, he vanished

in 1831, and was not heard of again until 1851. To these twenty

years of alleged disappearance one or two remarkable books of his

are, however, ascribed. It appears that what is perhaps the most

characteristic of all his writings, Du Dandyisme et de Georges Brummell,

was written as early as 1842; and in 1845 a very small edition of it was

printed by an admirer of the name of Trebutien, to whose affection

d’Aurevilly seems to have owed his very existence. It is strange that

so little is distinctly known about a man who, late in life, attracted

much curiosity and attention. He was a consummate romancer, and

he liked to hint that he was engaged during early life in intrigues of a

corsair description. The truth seems to be that he lived, in great

obscurity, in the neighbourhood of Caen, probably by the aid of

journalism. As early as 1825 he began to publish; but of all the pro-

ductions of his youth, the only one which can now be met with is the

prose poem of Amaïdée, written, I suppose, about 1835; this was pub-

lished by M. Paul Bourget as a curiosity immediately after Barbey

d’Aurevilly ’s death. Judged as a story, Amaïdée is puerile; it

describes how to a certain poet, called Somegod, who dwelt on a

lonely cliff, there came a young man altogether wise and stately

named Altar, and a frail daughter of passion, who gives her name to

the book. These three personages converse in magnificent language,

and, the visitors presently departing, the volume closes. But an

interest attaches to the fact that in Somegod (Quelque Dieu!) the

author was painting a portrait of Maurice de Guerin, while the majestic

Altar is himself. The conception of this book is Ossianic; but the

style is often singularly beautiful, with a marmoreal splendour founded

on a study of Chateaubriand and, perhaps, of Goethe, and not without

relation to that of Guérin himself.

The

The earliest surviving production of d’Aurevilly, if we except

Amaïdée is L’ Amour Impossible, a novel published in 1841, with the

object of correcting the effects of the poisonous Lélia of George Sand.

Already, in this crude book, we see something of the Barbey d’Aure-

villy of the future, the Dandy-Paladin, the Catholic Sensualist or Dia-

volist, the author of the few poor thoughts and the sonorous, paroxysmal,

abundant style. I forget whether it is here or in a slightly later novel

that, in hastily turning the pages, I detect the sentiment, ‘Our fore-

fathers were wise to cut the throats of the Huguenots, and very stupid

not to burn Luther.’ The late Master of Balliol is said to have asked

a reactionary undergraduate, ‘What, Sir! would you burn, would you

burn?’ If he had put the question to Barbey d’Aurevilly, the scented

hand would have been laid on the cambric bosom, and the answer

would have been, ‘Certainly I should.’ In the midst of the infidel

society and literature of the Second Empire, d’Aurevilly persisted in

the most noisy profession of his entire loyalty to Rome, but his methods

of proclaiming his attachment were so violent and outrageous that the

Church showed no gratitude to her volunteer defender. This was a

source of much bitterness and recrimination, but it is difficult to see

how the author of Le Prêtré Marié and Une Histoire sans nom could

expect pious Catholics to smile on his very peculiar treatment of

ecclesiastical life.

Barbey d’Aurevilly, none the less, deserves attention as really the

founder of that neo-catholicism which has now invaded so many

departments of French literature. At a time when no one else per-

ceived it, he was greatly impressed by the beauty of the Roman cere-

monial, and determined to express with poetic emotion the mystical

majesty of the symbol. It must be admitted that, although his work

never suggests any knowledge of or sympathy with the spiritual part

of religion, he has a genuine appreciation of its externals. It would be

difficult to point to a more delicate and full impression of the solemnity

which attends the crepuscular light of a church at vespers than is given

in the opening pages of A un Diner d’Athées. In L’Ensorcelée, too, we

find the author piously following a chanting procession round a church,

and ejaculating, ‘Rien nest beau comme cet instant solennel des cérémonies

catholiques. ’ Almost every one of his novels deals by preference with

ecclesiastical subjects, or introduces some powerful figure of a priest.

But it is very difficult to believe that his interest in it all is other

than histrionic or phenomenal. He likes the business of a priest

he likes the furniture of a church, but there, in spite of his vehemen

protestations

21

protestations, his piety seems to a candid reader to have begun and

ended.

For a humble and reverent child of the Catholic Church, it must

be confessed that Barbey d’Aurevilly takes strange liberties. The

mother would seem to have had little control over the caprices of her

extremely unruly son. There is scarcely one of these ultra-catholic

novels of his which it is conceivable that a pious family would like to

see lying upon its parlour table. The Devil takes a prominent part in

many of them, for d’Aurevilly’s whim is to see Satanism everywhere,

and to consider it matter of mirth; he is like a naughty boy, giggling

when a rude man breaks his mother’s crockery. He loves to play with

dangerous and forbidden notions. In Le Prêtre Marié (which, to his

lofty indignation, was forbidden to be sold in Catholic shops) the hero

is a renegade and incestuous priest, who loves his own daughter, and

makes a hypocritical confession of error in order that, by that act of

perjury, he may save her life, as she is dying of the agony of knowing

him to be an atheist. This man, the Abbé Sombreval, is bewitched, is

possessed of the Devil, and so is Ryno de Marigny in Une vieille

Maîtresse, and Lasthénie de Ferjol in Une Histoire sans nom. This is

one of Barbey d’Aurevilly’s favourite tricks, to paint an extraordinary,

an abnormal condition of spirit, and to avoid the psychological difficulty

by simply attributing it to sorcery. But he is all the time rather

amused by the wickedness than shocked at it. In Le Bonheur dans le

Crime—the moral of which is that people of a certain grandeur of

temperament can be absolutely wicked with impunity—he frankly

confesses his partiality for la plaisanterie légèrcment sacrilège, and all

the philosophy of d’Aurevilly is revealed in that rash phrase. It is

not a matter of a wounded conscience expressing itself with a brutal

fervour, but the gusto of conscious wickedness. His mind is intimately

akin with that of the Neapolitan lady, whose story he was perhaps the

first to tell, who wished that it only were a sin to drink iced sherbet.

Barbey d’Aurevilly is a devil who may or may not believe, but who

always makes a point of trembling.

The most interesting feature of Barbey d’Aurevilly’s temperament,

as revealed in his imaginative work, is, however, his preoccupation with

his own physical life. In his youth, Byron and Alfieri were the objects

of his deepest idolatry; he envied their disdainful splendour of passion;

and he fashioned his dream in poverty and obscurity so as to make

himself believe that he was of their race. He was a Disraeli—with

whom, indeed, he has certain relations of style—but with none of

Disraeli’s

22

Disraeli’s social advantages, and with a more inconsequent and violent

habit of imagination. Unable, from want of wealth and position, to

carry his dreams into effect, they became exasperated and intensified,

and at an age when the real dandy is settling down into a man of the

world, Barbey d’Aurevilly was spreading the wings of his fancy into

the infinite azure of imaginary experience. He had convinced himself

that he was a Lovelace, a Lauzun, a Brummell, and the philosophy of

dandyism filled his thoughts far more than if he had really been able

to spend a stormy youth among marchionesses who carried, set in

diamonds in a bracelet, the ends of the moustaches of viscounts. In

the novels of his maturity and his old age, therefore, Barbey d’Aurevilly

loved to introduce magnificent aged dandies, whose fatuity he dwelt

upon with ecstasy, and in whom there is no question that he saw

reflections of his imaginary self. No better type of this can be found

than that Vicomte de Brassard, an elaborate, almost enamoured, por-

trait of whom fills the earlier pages of what is else a rather dull story,

Le Rideau Cramoisi. The very clever, very immoral tale called Le

Plus Bel Amour de Don Juan—which relates how a superannuated but

still incredibly vigorous old beau gives a supper to the beautiful women

of quality whom he has known, and recounts to them the most piquant

adventure of his life—is redolent of this intense delight in the pro-

longation of enjoyment by sheer refusal to admit the ravages of age.

Although my space forbids quotation, I cannot resist repeating a

passage which illustrates this horrible fear of the loss of youth and the

struggle against it, more especially as it is a good example of

d’Aurevilly’s surcharged and intrepid style:

‘II n’y avail pas lk de ces jeunesses vert tendre, de ces petites damoiselles

qu’exécrait Byron, qui sentent la tartelette et qui, par la toumure, ne sent encore

que’des épluchettes, mais tons étés splendides et savoureux, plantureux automnes,

épanouissements a. plénitudes, seins éblouissants battant leur plien majestueux au

bord decouvert des corsages, et, sous les camees de 1’épaule nue, des bras de tout

galbe, mais surtout des bras puissants, de ces biceps de Sabines qui ont utté avec

les Remains, et qui seraient capables de s’entrelacer, pour l’arrêter, dans les rayons

de la roue du char de la vie.’

This obsession of vanishing youth, this intense determination to

preserve the semblance and colour of vitality, in spite of the passage of

years, is, however, seen to greatest advantage in a very curious book

of Barbey d’Aurevilly’s, in some aspects, indeed, the most curious

which he has left behind him, Du Dandyisme et de Georges Brummell.

This is really a work of his early maturity, for it was printed in a small

private ’edition so long ago as ,845. It was no, published, however,

until

23

until 1861, when it may be said to have introduced its author to the

world of France. Later on he wrote a curious study of the fascination

exercised over La Grande Mademoiselle by Lauzun, Un Dandy d’avant

les Dandys, and these two are now published in one volume, which

forms that section of the immense work of d’Aurevilly which best

rewards the curious reader.

Many writers in England, from Thomas Carlyle in Sartor Resartus

to our ingenious young forger of paradoxes, Mr. Max Beerbohm, have

dealt upon that semi-feminine passion in fatuity, that sublime attention

to costume and deportment, which marks the dandy. The type has

been, as d’Aurevilly does not fail to observe, mainly an English one.

We point to Lord Yarmouth, to Beau Nash, to Byron, to Sheridan, and,

above all, ‘à ce Dandy royal, S. M. Georges iv;’ but the star of each

of these must pale before that of Brummell. These others, as was said

in a different matter, had ‘other preoccupations,’ but Brummell was

entirely absorbed, as by a solemn mission, by the conduct of his person

and his clothes. So far, in the portraiture of such a figure, there is

nothing very singular in what the French novelist has skilfully and

nimbly done, but it is his own attitude which is so original. All other

writers on the dandies have had their tongues in their cheeks. If they

have commended, it is because to be preposterous is to be amusing.

When we read that ‘dandyism is the least selfish of all the arts,’

we smile, for we know that the author’s design is to be entertaining.

But Barbey d’Aurevilly is doggedly in earnest. He loves the great

dandies of the past as other men contemplate with ardour dead

poets and dead musicians. He is seriously enamoured of their mode

of life. He sees nothing ridiculous, nothing even limited, in their

self-concentration. It reminds him of the tiger and of the condor;

it recalls to his imagination the vast, solitary forces of Nature;

and when he contemplates Beau Brummell, his eyes fill with tears of

nostalgia. So would he have desired to live; thus, and not otherwise,

would he fain have strutted and trampled through that eighteenth

century to which he is for ever gazing back with a fond regret. ‘To

dress one’s self,’ he says, ‘should be the main business of life,’ and

with great ingenuity he dwells upon the latent but positive influence

which dress has had on men of a nature apparently furthest re-

moved from its trivialities; upon Pascal, for instance, upon Buffon,

upon Wagner.

It was natural that a writer who delighted in this patrician ideal of

conquering man should have a limited conception of life. Women to

Barbey

24

Barbey d’Aurevilly were of two varieties — either nuns or amorous

tigresses; they were sometimes both in one. He had no idea of soft

gradations in society: there were the tempestuous marchioness and

her intriguing maid on one side; on the other, emptiness, the sordid

hovels of the bourgeoisie. This absence of observation or recognition

of life d’Aurevilly shared with the other Romantiques, but in his

sinister and contemptuous aristocracy he passed beyond them all. Had

he lived to become acquainted with the writings of Nietzsche, he would

have hailed a brother-spirit, one who loathed democracy and the

humanitarian temper as much as he did himself. But there is no

philosophy in Barbey d’Aurevilly, nothing but a prejudice fostered and

a sentiment indulged.

In referring to Nicholas Nickleby, a novel which he vainly endeavoured

to get through, d’Aurevilly remarks : ‘ I wish to write an essay on

Dickens, and at present I have only read one hundred pages of his

writings. But I consider that if one hundred pages do not give the

talent of a man, they give his spirit, and the spirit of Dickens is odious

to me.’ ‘ The vulgar Dickens,’ he calmly remarks in Journalistes et

Polémistes, and we laugh at the idea of sweeping away such a record

of genius on the strength of a chapter or two misread in Nicholas

Nickleby. But Barbey d’Aurevilly was not Dickens, and it really is

not necessary to study closely the vast body of his writings. The

same characteristics recur in them all, and the impression may easily

be weakened by vain repetition. In particular, a great part of the

later life of d’Aurevilly was occupied in writing critical notices and

studies for newspapers and reviews. He made this, I suppose, his

principal source of income; and from the moment when, in 1851, he

became literary critic to Le Pays to that of his death, nearly forty years

later, he was incessantly dogmatising about literature and art. He

never became a critical force, he was too violent and, indeed, too

empty for that; but a pen so brilliant as his is always welcome with

editors whose design is not to be true, but to be noticeable, and to

escape ‘the obvious.’ The most cruel of Barbey d’Aurevilly’s enemies

could not charge his criticism with being obvious. It is intensely

contentious and contradictory. It treats all writers and artists on the

accepted nursery principle of ‘Go and see what baby’s doing, and tell

him not to.’ This is entertaining for a moment; and if the shower of

abuse is spread broadly enough, some of it must come down on

shoulders that deserve it. But the ‘slashing’ review of yester-year is

dismal reading, and it cannot be said that the library of reprinted

criticism

25

criticism to which d’Aurevilly gave the general title of Les CEuvres et

les Homines is very enticing.

He had a great contempt for Goethe and for Sainte-Beuve, in whom

he saw false priests constantly leading the public away from the true

principle of literary expression, ‘le couronnement, la gloire et la force

de toute critique, que je cherche en vain. A very ingenious writer, M.

Ernest Tissot, has paid Barbey d’Aurevilly the compliment of taking

him seriously in this matter, and has written an elaborate study on

what his criterium was. But this is, perhaps, to inquire too kindly. I

doubt whether he sought with any very sincere expectation of finding;

like the Persian sage, ‘he swore, but was he sober when he swore?’

Was he not rather intoxicated with his self-encouraged romantic exas-

peration, and determined to be fierce, independent, and uncompromising

at all hazards? Such are, at all events, the doubts awakened by his

indignant diatribes, which once amused Paris so much, and now influence

no living creature. Some of his dicta, in their showy way, are forcible.

‘La critique a pour blason la croix, la balance et la gloire;’ that is a

capital phrase on the lips of a reviewer, who makes himself the appointed

Catholic censor of worldly letters, and is willing to assume at once the

cross, the scales, and the sword. More of the hoof peeps out in

this: ‘La critique, c’est une intrépidité de l’esprit et du caractère! To a

nature like that of d’Aurevilly, the distinction between intrepidity and

arrogance is never clearly defined .

It is, after all, in his novels that Barbey d’Aurevilly displays his

talent in its most interesting form. His powers developed late; and

perhaps the best constructed of all his tales is Une Histoire sans nom,

which dates from 1882, when he was quite an old man. In this, as in

all the rest, a surprising narrative is well, although extremely leisurely,

told, but without a trace of psychology. It was impossible for d’Aure-

villy to close his stories effectively; in almost every case, the futility

and extravagance of the last few pages destroys the effect of the rest.

Like the Fat Boy, he wanted to make your flesh creep, to leave you

cataleptic with horror at the end, but he had none of Poe’s skill in pro-

ducing an effect of terror. In Le Rideau Cramoisi (which is considered,

I cannot tell why, one of his successes) the heroine dies at an embarrass-

ing moment, without any disease or cause of death being suggested—

she simply dies. But he is generally much more violent than this; at

the close of A un Dîner d’Athées, which up to a certain point is an

extremely fine piece of writing, the angry parents pelt one another

with the mummied heart of their only child; in Le Dessons des Cartes,

the

26

the key of all the intrigue is discovered at last in the skeleton of an

infant buried in a box of mignonette. If it is not by a monstrous fact,

it is by an audacious feat of anti-morality, that Barbey d’Aurevilly

seeks to harrow and terrify our imaginations. In Le Bonheur dans le

Crime, Hauteclaire Stassin, the woman-fencer, and the Count of

Savigny, pursue their wild intrigue and murder the Countess slowly,

and then marry each other, and live, with youth far prolonged (d’Aure-

villy’s special idea of divine blessing), without a pang of remorse,

without a crumpled rose-leaf in their felicity, like two magnificent

plants spreading in the violent moisture of a tropical forest.

On the whole, it is as a writer, pure and simple, that Barbey

d’Aurevilly claims most attention. His style, which Paul de Saint-

Victor (quite in his own spirit) described as a mixture of tiger’s blood

and honey, is full of extravagant beauty. He has a strange intensity,

a sensual and fantastic force, in his torrent of intertwined sentences

and preposterous exclamations. The volume called Les Diaboliques,

which contains a group of his most characteristic stories, published in

1874, may be recommended to those who wish, in a single example,

compendiously to test the quality of Barbey d’Aurevilly. He has a

curious love of punning, not for purposes of humour, but to intensify

his style: ‘Quel oubli et quelle oubliette’(Le Dessous des Cartes ), ‘bou-

doir fleur de pécher ou de péché’ (Le Plus Bel Amour), ‘renoncer à

l’amour malpropre, mats jamais à l’amour propre’ (A un Dîner d’Athées).

He has audacious phrases which linger in the memory: ‘Le Profil,

c’est l’écueil de la beauté’ (Le Bonheur dans le Crime ); ‘Les verres à

champagne de France , un lotus qui faisait [les Anglais] oublier les

sombres et religieuses habitudes de la patre;’ ‘Elle avait l’air

de monter vers Dieu, les mains toutes pleines de bonnes œuvres’

{Memoranda).

That Barbey d’Aurevilly will take any prominent place in the

history of literature is improbable. He was a curiosity, a droll, obstinate

survival. We like to think of him in his incredible dress, strolling

through the streets of Paris, with his clouded cane like a sceptre in one

hand, and in the other that small mirror by which every few minutes

he adjusted the poise of his cravat, or the studious tempest of his hair.

He was a wonderful old fop or beau of the forties handed down to the

eighties in perfect preservation. As a writer he was fervid, sumptuous,

magnificently puerile; I have been told that he was a superb talker,

that his conversation was like his books, a flood of paradoxical, flam-

boyant rhetoric. He made a gallant stand against old age, he defied

it

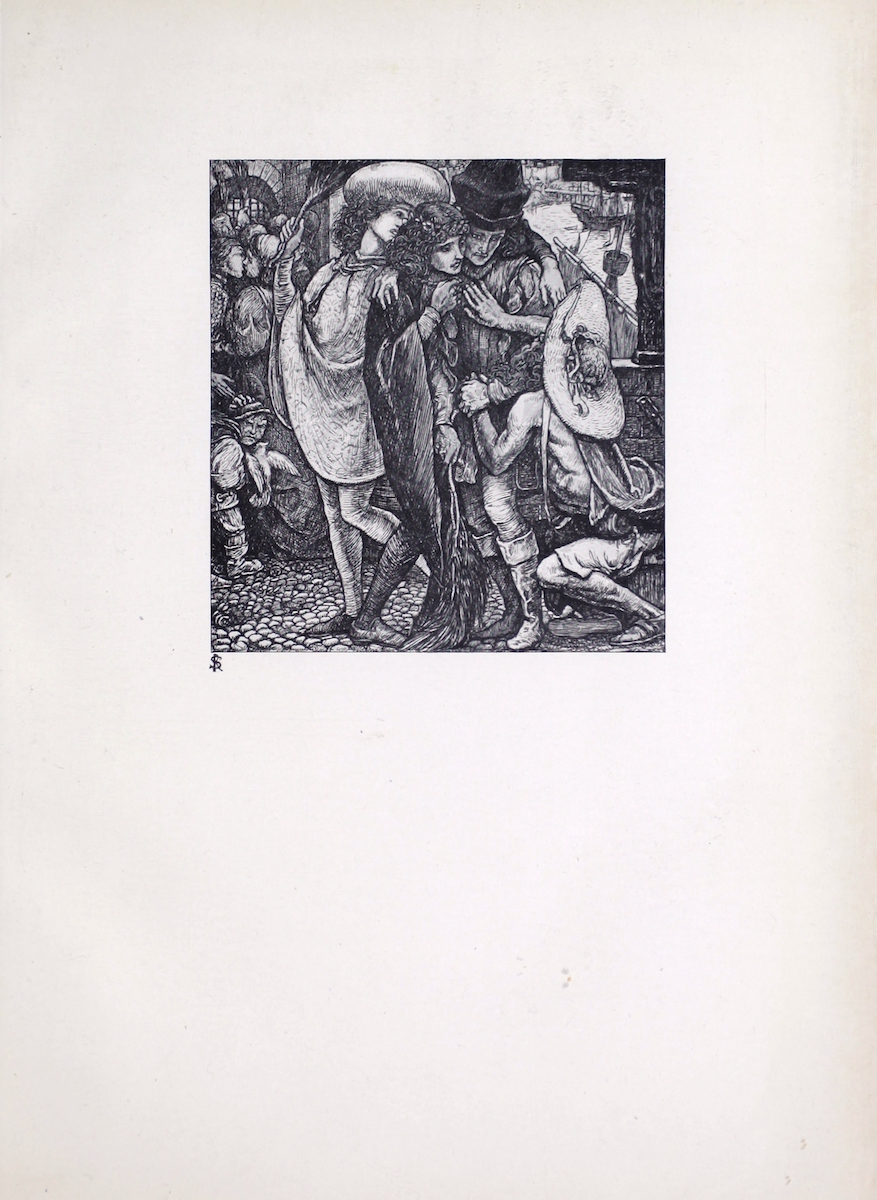

❧ THE ANCIENT MARINER

by

Reginald Savage

31

it long with success, and when it conquered him at last, he retired to

his hole like a rat, and died with stoic fortitude, alone, without a friend

to close his eyelids. It was in a wretched lodging high up in a house

in the Rue Rousselet, all his finery cast aside, and three melancholy cats

the sole mourners by his body, that they found, on an April morning

of 1889, the ruins of what had once been Barbey d’Aurevilly.

MISS PEELE’S APOTHEOSIS: A STUDY IN EXTRA-SUBURBAN AMENITIES

SOME of the little residential towns which lie

just outside the great zone of the London

suburbs are, if possible, more staunchly re-

spectable than the suburbs themselves. In

the latter, as everybody knows, society is at

times apt to be a little mixed, and it is not

always safe for well-bred people with sub-

scriptions at Mudie’s to call on the occupants

of the villa next their own unless they have

been first of all specially introduced to them by other thoroughly ‘nice’

persons. But in these little country towns which dot the home counties,

gentility and refinement are not thus imperilled. In Thegnhurst, for

instance, the lordly lady of Colonel Cholmondeley-Smith knows herself

perfectly safe in the drawing-room of the new tenant next door. For

that new tenant is the pretty, plaintive little widow of a something high

up in the Civil Service, and as such she is a supporter of noblesse and

clergé, and is received with open arms by the circle of the Anglo-Indian

matron. The Hon. and Rev. Parker Cope, a light of local society, a

cricketer and a curate, need never fear a fallen ‘H’ or a gauche allusion

in the house of the new-comer opposite him. For Mr. Philpott Burlegh

is an old gentleman of unimpeachable antecedents among those

mysterious collocations of exalted persons known as the ‘county

families.’ Even Mrs. Ponsonby Baker, the lady of a Thegnhurst

professional man, who having herself risen in some forgotten past from

the bar-parlour of the ‘Horse and Groom,’ is consequently a stricter

guardian of local social proprieties than a woman of bluer blood would

be—even Mrs. Ponsonby Baker need never be outraged by the arrival

in the town of a matron whose antecedents are too similar to her own.

No newly-wedded ex-lady of the ballet has ever ventured, as a resi-

dent, among the terraces of Thegnhurst. No gentleman with wealth

derived from a Regent Street emporium has ever brought a question-

able bride into the seclusion of those pleasant country haunts.

Gentility may indeed be said to run riot in dear little towns such

as these, as though in revenge for the continued existence upon earth

of vulgarity and eccentricity, of Brummagem sectarianism, of faddist

politics, of science, scepticism, the Bohemianism of the arts, and ’Appy

’Ampstead on a Sunday. There is something very charming to the

superficial eye in the air of ci-devant dignity which pervades their

residential

33

residential quarters. The very children, who all know one another,

who are all so healthy, sturdy, pretty, and well dressed, and who play

lawn tennis with big rackets in front of the gabled red-brick villas,—

the very children suggest an ancien regime full of cavalier memories

and Grandisonian traditions. The little sailor boys have the prettiest

manners towards the local ladies, albeit they occasionally thump their

nurses or one another. The little fair-haired girls are models of

wholesomeness and of grace of the healthier and less ideal kind. Mr.

Du Maurier might do worse than draw his child-types from Thegn-

hurst. Nor need his satire on their elders be anything but of

the most delicate kind; for such coarse motifs as those inspired by

the shoddy Sir Gorgius Midas, or the ambitious Mrs. Ponsonby de

Tomkyns, are unknown in the town. Society there is poor—too poor

to fall into the courses which so often bring down upon Mayfair the

charge of crude snobbishness or positive vulgarity. The snobbishness

of Thegnhurst is of a shade so subtle that it is difficult to apprehend it

with the naked eye of criticism. It is there certainly—it exists, but

so mingled with better things, with honest pride in honourable birth

and honourable tradition, that the man who in conversation tries to

satirise it is often fain to give up the attempt with a blush and the

sense of having said something stupidly ill-bred.

But if Thegnhurst is unimpeachably genteel—using the term in

all good faith, just as Miss Austen might have used it—it is also

unconquerably unidea-ed. As we have indicated above, it revenges it-

self upon vulgarity and eccentricity alike, and is inclined to class in the

latter category all the interests and achievements of Mind. Wagner,

Darwin, Browning, Renan—to jot down at haphazard sufficiently diverse

types—are as much anathema to it as the Rev. Jehoram Stiggins of

revivalist fame, or the secularist orator who was once caned by Colonel

Cholmondeley-Smith for trying to institute Sunday morning cricket on

Thegnhurst Common. It loathes genius, and it loathes isms, as frankly

and unquestionably as it loathes Demos.

Thus when, a few years ago, Mr. Hugo Peele and his daughter

Octavia came to live in a little cottage in the Mudleigh Road, an

unfashionable part of Thegnhurst, the young lady at any rate was from

the first destined to suffer social martyrdom. Mr. Hugo Peele and

daughter were not, it is true, guilty of any overt acts of intellectual

Bohemianism. They apparently neither wrote nor published books!

Nay, he was very old, feeble, and quiet: she was an inoffensive spinster.

Nevertheless, it became apparent at once to the ladies and gentlemen

of

34

of Thegnhurst that they were not ‘sound.’ In the first place, nobody

‘knew about them.’ They came to Thegnhurst like thieves in the

night, without those introductions or social relationships which usually

draw people to a particular place of residence. They had no relations

in the town, no friends, no acquaintances. They seemed even more

impecunious than the generality of Thegnhurstians. They dressed

shabbily. They kept only one servant. Many cases of books came

with them, and seemed to form the chief part of their belongings. Mr.

Peele never went to church, and when Miss Peele appeared there it

was observed that she sat down during the Creeds, and was moreover

a very plain girl. Had she been pretty, the male Thegnhurstians would

have forgiven her this little piece of heterodoxy, and even the more

severe among the ladies would have been too intent on finding fault

with her good looks to notice her theological aberrations. But, in that

she was a very plain girl, her sitting down during the Creed was voted

an enormity. Matrons began to ask one another whether they really

ought to call on Miss Peele. Orthodoxy decided against her, but

Curiosity decided against Orthodoxy, and the vicar’s wife determined

to call after a due and proper lapse of weeks.

Three months after the young lady’s first appearance in church the

visit took place. The vicar’s wife brought with her some little black

collecting books, intending, in case she should find her hostess an

undesirable acquaintance, at any rate to secure subscriptions for her

blanket society and her coal club before giving her the cold shoulder

in future. But Miss Peele did not appear wholly undesirable. She

was shy, ladylike, well educated, and explained her father’s absence

from the scene, and from church on Sundays, in the most natural way.

The vicar’s wife departed from the Peeles’ drawing-room with two or

three half-crowns and a fairly good opinion of at least one of the new

arrivals within the limits of her jurisdiction. When asked at the next

working-party in aid of the Zenana Mission whether she did not find

Miss Peele very odd, she replied almost charitably in her behalf:

‘She isn’t such an odd girl as she looks. Indeed, I rather like her!

She seems a ladylike girl, although she does sit down during the

Creeds!’

Other ladies, notably Mrs. Cholmondeley-Smith and the sweet little

widow, her neighbour, thereupon determined to call on this winner

of the vicaress’s good opinion. The month’s end saw the stately

Anglo-Indian local dignitary slowly mounting the three steps before

the Peeles’ front door. And a fortnight later the widow paid her visit.

Other

35

Other ladies, armed mostly with little black collecting books, from time

to time followed suit, and at the end of a year Octavia Peele had

attained to a nodding acquaintance with nearly all the society of the

place. Only Mrs. Ponsonby Baker held aloof, but then such a very

eclectic society lady could not be expected to come to terms under five

or six years at the very least. Such a period, by the by, is a mere

nothing in the placid etfernities of rural existence at Thegnhurst, where

social standing is as often measured by length of residence as not.

But though everybody had called upon Miss Peele, it cannot be

said that they had been all prepossessed precisely in the same way

as the vicaress. A gay young grass-widow and a frisky old maid

or two had been bored by her to the verge of openly expressed con-

tempt. She had no cricket, no lawn tennis, no dancing conversation.

She appeared never to have seen a horse or a golf club. She took no

interest in dashing young military men or brisk young curates. Having

no brothers, she never referred fascinatingly to ‘dear Jack out in

Lahore,’ or ‘that silly Tom at the Cape.’ She had no ideas on dress.

Above all, she was gravely plain, not unpleasantly or grotesquely so,

but simply gravely plain, quietly lacking in good looks. In the esti-

mation of some women, as we all know, the absence of these is as

unpardonable as their presence in a too marked degree. The gay grass-

widows and sprightly old maids of Thegnhurst were perhaps not quite

so hard to please; still, what had they to do with plain girls like Miss

Peele?

Charming young married women, stately matrons, authoritative

mothers in Israel with six or seven strapping sons at the army

crammers’, in the backwoods, and elsewhere—matrons of all kinds

could make nothing of Octavia. If they talked to her of primrose

politics, they found her delicately inattentive. A tirade against servants

only served to elicit the fact that she considered Abigail in the light of

a sister woman. A general discussion on Church work found her

lamentably ignorant of distinctions of sect and party. Eulogy of the

vicar seemed to pall on her.

Young unmarried ladies between the ages of seventeen and thirty

found themselves even more out of touch with her than the foregoing.

By her plainness, her distance from the possibility of being admired by

the other sex, they were unconsciously estranged. Her lack of interest

in Anglicanism and athletics set her on an icy, unfashionable pinnacle,

which they certainly did not envy as one usually envies pinnacles.

Above all, her unmistakable culture was a stumbling-block to them.

Lilly

36

Lilly Cranley, daughter of old General Cranley, late of the Bombay

Army, a thoroughly sensible girl in the estimation of the matrons, was

one day calling on Octavia—it was her first call and her last—and

happened in the course of a few remarks on her favourite novels to

make the then fashionable inquiry, ‘Have you read Pace? My

brothers think it ’s not quite the thing for girls to read, so, of course,

I’ve got it at the Railway Library.’

‘No, I am sorry to say I haven’t read it,’ said Miss Peele, with her

pleasant smile, which somehow or other always seemed insincere.

‘I’ve been making out Theocritus with the help of a lexicon this

morning.’

‘Who was Theocritus?’ said bright Lilly Cranley (educated by

governesses and at Brighton).

‘Oh,’ said Octavia, her eyes—she had fine eyes—brightening ex-

tremely. ‘Do you really care to talk about him? He was a poet, a

Sicilian Greek’ And she went off at score, talking with eloquent

animation for quite ten ecstatic minutes.

‘Greek!’ ejaculated Miss Cranley, whose unmoved face had finally

chilled Octavia into silence. ‘Greek! How deep!’ And with that,

timidly, as though in dread of further appeals to that tiresome, un-

fashionable part of her, the brain, she bade our heroine farewell, and

with hastily gathered up gloves and parasol beat a precipitate retreat.

Alas, poor Octavia! In homely phrase, she had let the cat out of

the bag at last. Her attacks on the Greek language and literature

were now open to public comment. In less than a week Thegnhurst

drawing-rooms were able to add point to their vague general feeling

against Miss Peele. They had always guessed—they now knew she

was a blue-stocking, a strong-minded woman. She was a finished

Greek scholar. Nay, she knew Hebrew, Sanscrit, Arabic! What did

she not know indeed? She was an unmitigated mass of learning.

She was deep!

Her eccentric course of conduct during the Creed, long ago given

up by her in common with other passing phases, was avidly remembered.

She was undoubtedly an unbeliever as well as a blue-stocking! ‘She

is a what-you-call-’em—a—a Positivist Darwinite!’ gasped Mrs. Chol-

mondeley-Smith.

‘She’s a frump!’ ejaculated her neighbour, the dear little widow.

‘I know it’s not nice to say so, but she is!’

Calls, which had occurred in Miss Peele’s life like the rare detona-

tions of a dying fusillade, now ceased almost altogether. Octavia’s

Greek

37

Greek lexicon had achieved her isolation. She was now as much

disregarded as a fallen minister at the court of a despot.

But, though scarcely called upon, she was not actually cut. The

kind of honour, of esprit-de-corps, which actuates Thegnhurstians to a

creditable extent, forbade that. Having once made her acquaintance,

they did not cease to receive her; they did not even exclude her from

their more formal gatherings. To the squire’s yearly ball Miss Peele

was duly invited, albeit, when there, her wall-flower presence was a

delicate irritation to many. To Mrs. Cholmondeley-Smith’s annual

picnic Miss Peele, surrounded by an irksome aura of knowledge and

wisdom, also went, as well as to an ‘At Home’ at the vicarage arid a

‘Small and Early’ at the little widow lady’s, both of which entertain-

ments were biennial. But outside the pale of these, there was no social

life for Octavia in Thegnhurst. Months at a time would pass without

bringing her those little spells of polite intercourse with her kind, which,

in the country, are such a relief to all but hermits. Weeks—nay,

irregular periods, verging on three calendar months—would pass with-

out her being visited by anybody more clubbable than district visitors

in search of small donations. Time began to hang leaden on Octavia’s

hands. Her spirits began to droop fearfully. Old Hugo Peele could

give her no comfort. Absorbed as he was in the study of an abstruse

and antiquated branch of science, which he pursued with senile per-

sistence, the dull non-human atmosphere of Thegnhurst was entirely

congenial to him. When, with an old man’s feeble pace, he left his

study to walk abroad in the world, it was the fields, the common side,

the hills which he sought—not the society of his kind. He avoided

people, and they equally avoided him. To the generality of Thegn-

hurstians he was indeed a sort of superannuated necromancer,

dowered with much dark knowledge which it was just as well not to

examine too closely. And to him Thegnhurst society meant simply a

succession of masks without import of any kind.

For many months Octavia walked out every other day with her

father. The pair paced along very slowly, and talked very little as

they went, and the effect of these solemn perambulations on the young

lady’s spirits was not hopeful. At the close of one of them, when the

red December sunset was dyeing the westward heavens, and all the

landscape of winter fields looked brown and chill as some uninhabited

desert, Hugo awoke from abstraction to find his daughter in tears.

‘What’s the matter, child?’ he queried affectionately, for to him this

daughter was dearer even than his mistress Science.

‘Oh

‘Oh, nothing,’ said she; ‘nothing, except that ’

‘Well, dear?’ said Mr. Peele, weakly fumbling with his boots round

the rickety door-scraper at the top of the cottage steps in Mudleigh

Road.

‘Except that I wish I were anywhere but in Thegnhurst,’ she

almost cried.

‘Why, where else would you be, little one?’ was the half-querulous

rejoinder.

‘Oh, anywhere,’ said ‘little one,’ who, by the by, was some five or

six-and-twenty; ‘anywhere among intelligent, sympathetic people!’

‘Nonsense,’ said the old man, with a touch of irritation in his voice.

‘ Among intelligent people, as you call them, you meet with nothing

but intellectual arrogance and literary jealousy. Do you remember

London and its crowd and smoke?’ And he cleared his old throat

energetically at the thought.

Octavia remembered the delights of the British Museum Reading-

Room—they were delights to her—enjoyed for all too short a season

years ago, and a genuine sob choked her further utterance.

At supper-time the old gentleman discoursed at some length on the

beauty of the rural life.

‘The country is always sublime,’ he said, as he peeled his orange.

‘And solitude is good, and so are books, and so is study. What I

always am saying to you, Octavia, is, “Engross yourself in some great

overmastering study,” as I do. Take up any subject you like, but

engross yourself in it when once you have taken it up! Man muss

immer etivas studiren!—you know Professor Schweinfleisch’s motto:

“One ought ever to be studying something.” Ah, there is all Germany

in that saying!’

Octavia wept silently in her bedroom at night, but her tears this

time were not for herself. They were for that dear, feeble, white-haired

father, that ineffectual, indefatigable follower after truths which men had

discredited. Her father’s lonely, ascetic life, his severity of ideal, his

practical failure, thronged her imagination like the several movements

of a romance. Her heart was wrung with infinite tenderness, infinite

pity, and in an access of soft-hearted remorse she determined never

again to sadden him with her discontents.

It was during ever drearier growing months, each day and hour of

which made Octavia feel more petrified in heart and head, that good

news reached the cottage at Thegnhurst. A cousin of Miss Peele’s, a

bright little worldly-wise woman, wrote to say that she and Tom, her

husband,

39

husband, were thinking of coming to live in Thegnhurst, ‘as Jimmy

and Alec are both being sent to Harrow, and we want to exist as

cheaply as possible till such time as they can shift for themselves or

Tom can get something to do.’ Further on in the same letter she men-

tioned that, as there was a good preparatory school at Thegnhurst, they

were thinking of sending Dodo there.

Dodo was the name by which these lovers of sobriquets knew

Master Eustace MacLeod Featherstonehaugh Peele, their youngest

born. And Octavia brightened up considerably at the thought of

seeing the dear little lad again. She was stirred into cheerful activity

too by the house-hunting and school-hunting expeditions she was now

called upon to undertake in her cousin’s behalf.

In another fortnight Tom Peele arrived on the scene. Tom was a

most deliberate man, whose sentences took many minutes at a time to

deliver.

‘Octavia,’ he said, with sharp solemnity, as at close of day they

stood in the roadway outside Hugo Peele’s cottage. ‘Octavia, listen

to me! Pay attention, please!’

Miss Peele listened, bowing her head with the meekness which was

characteristic of her.

‘I think—that—that—urn er!—that’ (a pause, during which his wife

would have impatiently counted sixty below her breath)— ‘that the

houses you have been looking at for us won’t suit us at all!’

The last part of this rather chilling sentence came with a rush, and

after its delivery Tom drew a long breath, and rested in the manner of

a finished orator.

‘I think,’ he continued, ‘we want a cheaper house! This one’ (a

pause, during which his mind seemed to wander dreamily over the

scenes of a happy past)—‘this one—this little crib next door to yours—

will—um er—will’ (his wife would have got to sixty-five here)—‘will

exactly suit us!’

The crib in question was even smaller and less convenient than the

Peeles’, and Octavia felt a little feminine thrill of pleasure at the

thought that this mysterious and experienced Tom and his socially

brilliant wife were going to descend thereto. Together the cousins

went and looked over the house. Tom approved its every shabbiness,

and became its tenant before leaving for town by the last train.

A few days afterwards Maggie, his wife, and Dodo, his youngest

born, came and took possession. ‘You great goose,’ Maggie had said

to Tom in the tender privacy of midnight, ‘what made you take that

wretched

40

wretched little box next door to them ? You know, the whole thing’s

an experiment! They may be well in with the Thegnhurst set, or they

mayn’t. If they’re not, where are we?’

However, after her instalment in the said box, Maggie behaved, to

all appearances, admirably. She fell on Octavia’s neck, wept a very

little, poured out a pathetic tale of narrowed means, and ended by the

hope that in future they would be able to face the miseries of shabby

gentility shoulder to shoulder, as behoved cousins and next-door

neighbours.

Octavia, after listening to this confession, felt herself a new creature.

The coming into her quiet life of this brilliant, bustling lady filled her

with intimate excitement. She kissed Maggie with an effusion of

grateful sympathy, and repaid her tears with heartfelt words and many

pressures of the hand.

For some months after the arrival, Tom Peele’s wife was never out

of Hugo Peele’s house except at meal-times. But gradually very

gradually at first, then with increasing swiftness—a change began to

come over the cordial relations existing between the two households.

Octavia noticed that Maggie came seldomer and seldomer to see her.

She noticed, as she looked out of the dining-room window, that the

élite of Thegnhurst were calling on Maggie. She noticed, too, that

Maggie went out presumably to return their calls, and that in passing

Hugo Peele’s garden-gate she looked straight ahead of her, and hurried

her pace, as though not wishing to be recognised and stopped.

The little worldly woman was in fact making great social way in

Thegnhurst. People were charmed with her. They were seduced by

her bright and apparently artless allusions to her grand relations—to

my dear old grandfather General Sir Monro this, and my poor dear

friend the Countess that. They adored the particular kind of poverty

she practised. For poverty with Maggie Peele was practised as an art.

She knew how to make it pretty, almost fashionable. Her clear-cut

well-bred English was never more pleasant to listen to than when

economy, and the Civil Service Stores, and the revivification of last

year’s gowns, were under discussion. Her caustic wit was never more

mirth-provoking than when she mimicked the rustic tones of her poor

little Salvationist housemaid, or described the ejectment from her

premises of the tipsy cook. Maggie, by the by, somehow managed

to keep three servants, a very grand establishment, according to Thegn-

hurst ideas. Above all, people liked and approved her religious views,

her politics, her contemptuous attitude towards prigs, faddists, geniuses,

and

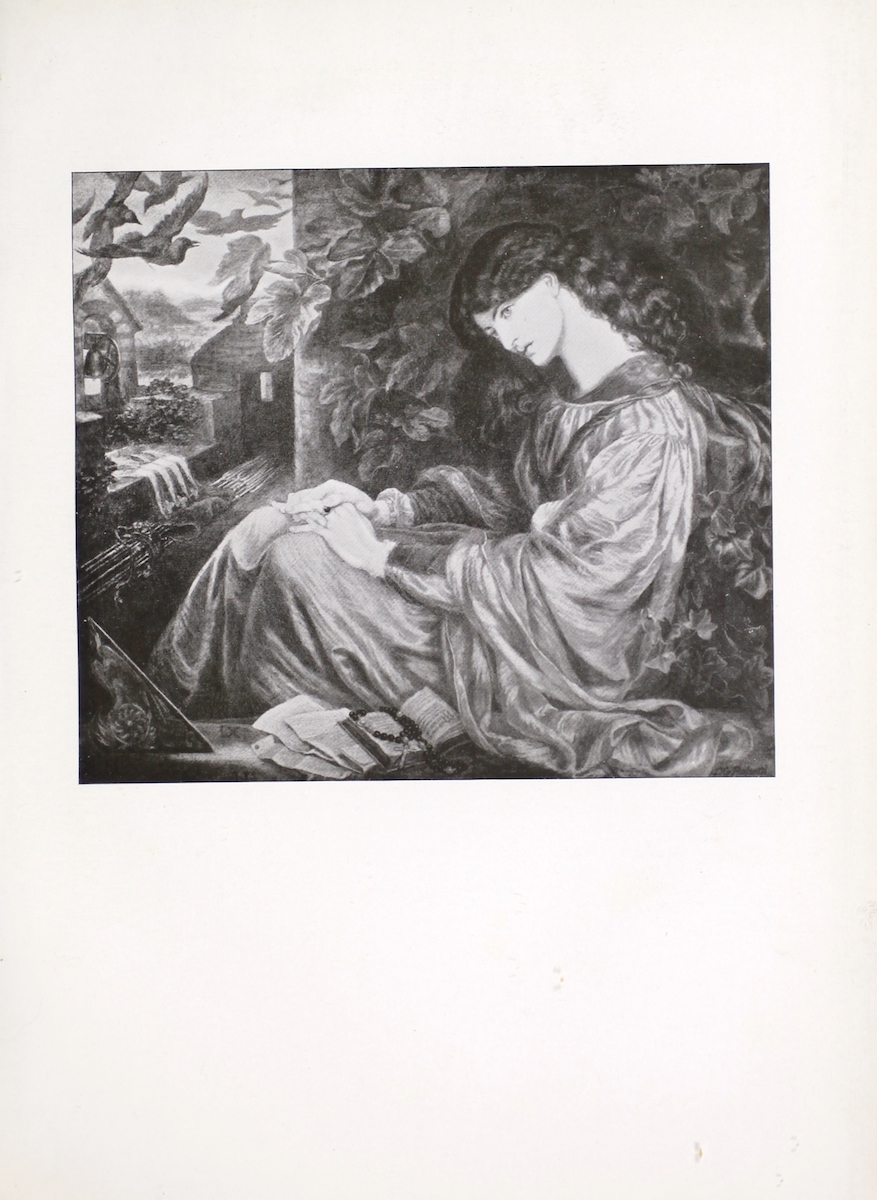

❧ LA PIA

by

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

45

and the socially shabby. They were indeed never more happy than

when they found themselves sitting in her aesthetic little back drawing-

room, drinking tea out of some rare old china, which Maggie sometimes

declared had been bought at ‘dear old Simla,’ and sometimes boasted

to be a present sent by the Duke of Punchestown from ‘one of those

funny tumbledown places in Italy, you know.’ In the end their

approving affection found voice through Mrs. Cholmondeley-Smith.

That lady, sitting glorious by Maggie’s fireside, where the dearest of

brass kettles reflected itself in the art tiles within the fender,—that great

lady was moved to cry out, ‘O Mrs. Peele! why don’t you come and

live among us? The Grove is such a way from this! Do come and

live in the Grove: we shall feel that you are really our neighbour then!’

The ‘Grove,’ be it said, is the Mayfair of Thegnhurst. To live in

the Grove is to be among the socially elect. It is the boast of the

‘Grovites,’ as they are enviously named, that they all call one another

by their Christian names, that they are always in and out of one

another’s houses, and that, towards the outer world of commerce and

ungentility, they oppose an impenetrable and unchanging front.

‘Your neighbours surely won’t prevent your joining us,’ said the

plaintive little widow. To which Mrs. Maggie replied with an

indescribable little grimace, delightful to the delicately humorous

sense of the company. These other Peeles were never definitely

named to Maggie by her new allies. It was tacitly felt that to ask

such a dear, clever woman whether she was any relation of that odd

girl, Octavia Peele, would be to insult her. And Maggie, on her side,

adroitly took advantage of this delicacy, and left her relationship to

her next-door neighbours a matter of the supremest doubt. She had

early guessed that the Hugo Peele element was indifferently regarded,

nay, even unpopular, in Thegnhurst, and neither by word nor deed did

she ever connect herself too irrevocably therewith. Well, the upshot of

all this was that, in no long time, the Tom Peeles left their cottage in

Mudleigh Road, and ascended into the charmed liberties of the Grove.

‘Darling Tavie,’ said Maggie to our heroine, who had been slaving

to pack up Dodo’s school-books and cricket-bats on the day of the

flitting, ‘we must see as much of one another as ever when I am

settled in the Grove!’

‘I do hope so,’ said Octavia disconsolately. ‘But I know what

going to live in the Grove means!’

‘Oh, nonsense,’ said the other.

Still, ‘darling Tavie’ was right. From the very day that her

cousins

46

cousins settled in the patrician quarter, in a little house standing

midway between the demesnes of the Cholmondeley-Smiths and the

Ponsonby Bakers, they began to treat her as did the rest of Thegnhurst.

So little indeed did she see of them that she grew shy at the mere

thought of walking the quarter of a mile separating her father’s house

from the terraced Grove, and contented herself with asking curly-

haired Dodo, whom she met in the fields, about his parents’ health and

doings. The child did not always respond very willingly. When he

chanced to be running about with other sailor boys he even tried to

shun cousin Tavie. The fact was that his new companions, having

often heard her rather unmercifully discussed by their elders, shouted

at the mere mention of her name in a way that chilled and puzzled his

poor little wits.

Tavie noticed that the child too was estranged from her, and her

poor heart, craving always for sympathy, was sometimes fit to break

outright. There is a nadir in the existences of those many quiet

women who are not unendowed with nerves or a critical faculty to

which men can never wholly sink. Men are always able to escape to a

certain extent at least from the gnawings of the introspective tendency

which is born of nerves. But women in Tavie’s position cannot. A

hundred bonds bind them to the rack — bonds of filial duty and

affection, bonds of helpless dependence and inexperience. Octavia,

in her wildest moments of revolt against her chilling unsocial existence,

was always sure to be pricked by a sort of conscience which spoke to

her of her father and of his foibles as of something unutterably sacred.

Her father’s chief foible was, of course, a delight in rural Thegnhurst,

lonesome Thegnhurst, and this delight was an iron law to her.

Under similar circumstances a more commonplace girl would have

turned to religion for solace. But religion, in the ordinary parochial

sense of the term, was impossible for this highly critical nature.

Octavia’s nearest approach to the religious state was a certain self-

pity, a certain constant soreness of mind and heart, a certain half-

mystical, half-pessimistic affection for failure and weakness in others.

It was while Miss Peele was deeply affected by this long-drawn,

morbid phase that Tom’s wife, who was now fashionably metamor-

phosed into Mrs. Hatherley-Peele, came down upon her with an offer.

‘O Tavie dearest,’ she said in her most émpresse manner, ‘you are

just the body who can do me a service. The vicar has asked me to

take a Sunday-school class for him. Now you know I can’t bear

children, especially poor children. It’s very wrong, but I can’t help it.

Now

47

Now I know you are a dear obliging creature, and won’t mind helping

me, will you, Tavie? I want you to take the class for me—there!

They are all little boys; you can easily teach them. Just talk seriously

to them about Catholic doctrine, and try and knock Dissent out of

them. You know the kind of thing!’

Octavia loved children sentimentally, and the children of the poor

touched her above all others. But how could she undertake Sunday-

school work? However, her timid objections passed off the hard

narrow surfaces of Mrs. Hatherley-Peele’s mind like water off a duck’s

back, and at last the young lady agreed to accept the ‘offer,’ subject to

the vicar’s decision.

Maggie marched off in high feather. She felt she had done an act of

supererogation in thus offering what she did not want to her eccentric and

uncomfortable cousin. Octavia, on the other hand, feared she had half

promised where she could nowise perform. So she wrote to the vicar to

explain her scruples. It was a bold stroke, and the reverend gentleman

thought it a very odd one. The letter was of the kind a George Eliot

might have written at the age of twenty, supposing, of course, that the

great authoress had been other than evangelical at that age. It was a