XML PDF

Charles Haslewood Shannon

(1863 – 1937)

Most scholars of the 1890s know Charles Shannon as one half of a celebrated artistic partnership with Charles Ricketts, which was so close that the two initially shared an artistic monogram, and lived together for most of their lives. Their joint output includes some of the most iconic art of the fin de siècle, including the Books Beautiful of their Vale Press and the little magazines The Dial and The Pageant , both available on the Yellow Nineties website. Ricketts is the more studied of the two, because of his association with Oscar Wilde, but in their own day, Shannon was more widely known. As a painter and lithographer, he has a distinct identity that makes him stand out amongst the artists of his period.

Charles Haslewood [also commonly “Hazelwood”] Shannon was born on 20 April 1863, the second son of the rector of the small town of Quarrington in the East Midlands. By all accounts, from an early age, “handsome, curly-haired Shannon” showed the quietly industrious personality that would characterize him throughout his life (Holmes, Self, 141). When he discovered a considerable talent for draughtsmanship, his Reverend father allowed him to enrol at the City and Guilds Technical Art School, also known as the Lambeth School of Art or Kennington Art School for its more precise location in South London. It was here that he came to know Ricketts and later collaborator Reginald Savage (1862–1932), as well as his first housemate, the cartoonist Leonard Raven-Hill (1867–1942).

Kennington was a forward-thinking institution that, under the leadership of the educationalist John Sparkes (1833–1907), first combined vocational training in “technical” or applied arts with the academic curriculum of fine art skills such as modelling and life drawing, hitherto only practised at the Royal Academy. The school can therefore be argued to have played a considerable part in the bringing together of “arts” and “crafts,” even before there was a movement dedicated to this purpose. Shannon and Ricketts met under a joint apprenticeship to Charles Roberts (active 1870–1898), the most respected wood engraver of this period, right before the then strictly “technical” art of engraving—a means of image reproduction—was replaced by new and far more efficient photographic methods (Delaney 28). No doubt it was the school’s combined technical and academic training that allowed Ricketts to combine in one person the conceptualizing artist and the executing craftsman, separated since Early Modern times, and thereby help to reinvigorate wood engraving as an art form in the late Victorian era. Shannon would not go on to do much work in engraving, instead focusing on the more modern but similarly technical medium of lithography and making a name for himself as a painter.

Shannon exhibited at the Impressionist stronghold of the New English Art Club in the 1890s, but his painting was eclectic, and he had little in common with his contemporaries. His work has a peculiar modernity of its own, however, through its appropriation of themes and styles from seemingly disparate traditions across Western art history. His aesthetic principles, if not his style, perhaps came closest to those of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898), often hailed as a precursor to Symbolism. This French painter was the subject of an article and a poem in the Dial and was also reproduced by art editor Shannon in the Pageant. Ricketts and Shannon cherished the memory of meeting their opinionated idol in his final years, in terms that may elucidate the origins of their own artistic creeds:

From time to time his speech became admonitory, and he launched forth into disapproval of current tendencies—the photographic drawing of many, “la perfection bête qui n’a rien à faire avec le vrai dessin, le dessin expressif!” [the stupid perfection that has nothing to do with true drawing, expressive drawing] and against “les pochades d’atelier et de vacance” [colour sketches of the studio and holidays]. (Ricketts, “Puvis,” 70)

Puvis likely intended the then upcoming styles of naturalist Realism and Post-Impressionism. Shannon avoided both these fashionable opposites by going back to older modes of representation. Yet, notably, he would not go back as far as the Pre-Raphaelites, who, at least originally, connected to the legacy of Florentine artists of the earlier fifteenth century, favouring the great Venetians of the High Renaissance instead. Consequently, he was styled “the English Giorgione” by Laurence Binyon (1869–1943) in 1907 (Darracott, World, 69). It is, however, impossible to pin Shannon down to one influence. Some of the most accomplished early paintings, such as Tibullus in the House of Delia (ca. 1900), are indeed decidedly Venetian, but reminiscent of a later period in their suggestion of the tonal qualities of the mature Titian (Darracott, World, 58). The painting features Ricketts on the left and Shannon himself on the right, and between him the suffragist and model Edith Broadbent alias Rhyllis , once the mistress of Arthur Symons but at this time the wife of William Llewellyn Hacon (1860–1910), who managed the business side of Ricketts’s and Shannon’s Vale Press. Another Vale Press associate, Charles Holmes (1868–1936), puffing his friend in the little magazine The Dome (1897–1900), would around the same time claim Shannon as one of the foremost “Modern Followers” of Velazquez, as ‘[c]ertainly, among our younger artists, [Shannon] is the one who seems to have appreciated the great Spaniard with the most absolute justice’ (Holmes, “Velazquez,” 94). To make matters even more complicated, Shannon was also echoing seventeenth-century portraiture in paintings such as Souvenirs of van Dyck (1897). The diversity in style claimed by Shannon seems to fit Ricketts’s defiant defence of eclecticism in the second number of The Dial (1892), arguing that “all good art” is but a “Document” or “monument of moods”, and that each of these moods might demand their own most suitable form of expression (“Unwritten,” 24–5).

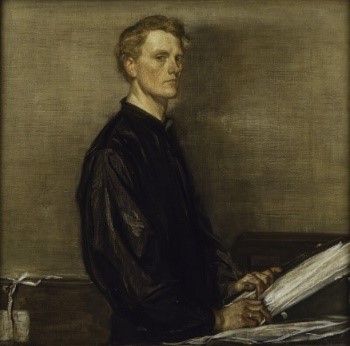

Around the turn of the century, Shannon started producing portraits, including the self-portrait at the top of this essay. The highbrow magazine The Athenaeum (1828–1921) declared that this painting “vanquished Whistler on his own ground” when it was first exhibited in 1898 (613). Starting from this period, Shannon obtained many commissions from patrons who probably appreciated his characteristic versatility as it allowed him to deliver an individual approach proper to each subject, as well as the pageantry of being depicted in unusual poses and often anachronistic styles. His 1898 portrait of Ricketts, now in the National Portrait Gallery, was praised by the sitter as capturing him “turning away from the 20th century to think only of the 15th” (quoted in Delaney 110). Shannon has also left us intriguing likenesses of fellow artists, as well as of wealthy socialites and the actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell (1907–currently at Tate Britain). He was made an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1911 and a full RA in 1920.

Among a more restricted audience of connoisseurs, Shannon established a reputation for himself by the early 1890s, not only for his painting but also for being an early British adopter of artistic lithography. Lithography, a printing technique that has been around since the late eighteenth century, involves images grafted into slabs of stone (Gr. lithos) though a chemical process. In the Victorian era it was widely used in commercial printing, for instance for maps, but until the 1880s the only major artistic practitioner active in Britain was J. A. M. Whistler (1834–1903). Artists who wanted to come to grips with the medium were of necessity self-taught, as it was not on the curriculum at even the most practically-oriented art schools, such as Kennington. Shannon picked it up by trial and error from the handbook The Grammar of Lithography by W. D. Richmond (1880), “a full and explicit account of the art of lithography in its various branches, adapted to the requirements alike of the amateur and professional” (1). In France, lithography had been a prestigious artistic medium for decades, and it is testimony to Shannon’s proficiency that he was soon invited to contribute to the L’Estampe Originale (1893–1895), a short-lived but monumental series of print portfolios that included all the major lithographers active at that time, including Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904) and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901). Another Britain-based contributor was Joseph Pennell (1857-1926), who in his later overview of Lithographers and Lithography (1898 / expanded in 1915) noted that, in Britain at least, and excluding Whistler, Shannon had “done more than anyone else” for the development of this art (178). It is indeed fair to say that his experiments helped to induce a trend among younger artists, eventually leading to the odd little magazine The Neolith (1907–1908) that was entirely—illustrations and text—produced through lithography, and which the by-then eminent Shannon could consecrate through a contribution.

In their diverse styles and themes, there is a clear connection between Shannon’s painting and his lithography. William Butler Yeats (1865–1939), in the throes of his Nineties obsession with symbols, tried to claim Shannon’s lithographs for a broad Symbolist movement that would go back to the early nineteenth century, but had come to flourish in the fin de siècle. Shannon’s lithographs would

but differ from the religious art of Giotto and his disciples in having accepted all symbolisms, the symbolism of the ancient shepherds and star-gazers, that symbolism of bodily beauty which seemed a wicked thing to Fra Angelico, the symbolism in day and night, and winter and summer, spring and autumn, once so great a part of an older religion than Christianity; and in having accepted all the Divine Intellect, its anger and its pity, its waking and its sleep, its love and its lust, for the substance of their art. (231–2)

In a word, again, his artworks were eclectic. In a preface to a catalogue for Shannon’s 1902 lithography exhibition at the Dutch Gallery, Ricketts noted correctly—and more concisely—that “the roots of all art spread far” (“Prefatory,” 147), and arguably for few farther than for Shannon. As in painting, the Impressionist and Realist modes dominated in this medium at the time. But Shannon here too favours historical and mythological subjects. He achieves in prints such as “ A Romantic Landscape” (1893) an ethereal effect, likely inspired by the visionary scenes in the lithographs of his idol Puvis, and the “iridescent and vaporous effect” of the aforementioned Fantin-Latour (Ricketts, “Prefatory,” 139). This may also derive from “the daintiness and delicacy of the artist’s own temperament,” commended by the critic Marion Spielmann in an article on “Original Lithography: The Present Revival” for the Magazine of Art (290), an authoritative journal. It is worthy of note that Spielmann presents Shannon as being a revivalist of the art of original lithography, whereas Ricketts was often lauded for helping to revive original engraving: both print arts were liberated, as it were, through the recent technological obsolescence of all manual means of image reproduction. With Shannon, “the charm of his work is distinctly that proper to lithography itself” (Spielmann 290).

Shannon and Ricketts started their artistic partnership immediately after graduating, and soon settled into distinct roles that fit their complementary but contrasting personalities. Before they developed career paths of their own in the early twentieth century, they were usually mentioned in the same breath. Also, they never lived apart. The unconventional relationship was speculated about, but even during the homophobic panic surrounding the Wilde trial, the discretion of their private lives and a lack of interest in sexually controversial themes in their art saved them from notoriety. It seems significant that the Uranian poet and activist John Addington Symonds (1840–1893) in the mid-Nineties was convinced of the fact that they were an item (Delaney 25). Diaries and letters have revealed that Ricketts was certainly homosexual, and that Shannon had affairs with female sitters. Recent scholarship on their shared involvement with the queer culture of their time may confirm the rumours of their being a romantic couple, if not an exclusive one (Cook passim). From the start, Ricketts considered Shannon as the more likely to become famous because of Shannon’s greater talent for painting, which—despite the burgeoning Arts & Crafts Movement—was still the most prestigious art form. In their early bohemian days, Ricketts selflessly took on hackwork to pay the bills while Shannon developed his artistry untainted, and he also acted as his friend’s publicist (Delaney 37). Shannon taught at the Croydon School of Art in the mid-1880s, where his students included Thomas Sturge Moore, who later became a regular contributor to his and Ricketts’s periodical ventures.

The first of their magazine collaborations, The Dial, was conceptualised in 1889 as an extension of the coterie that Shannon and Ricketts gathered around themselves at their home in the Vale. an idyllic glade in the middle of Chelsea that somehow survived until the early twentieth century. Their home there, from 1888 to 1898, had been previously occupied by Whistler and was the scene of a salon that hosted an array of rising artists and authors, as well as established names such as Whistler and Wilde. The Dial would serve as a common platform for the aspiring talent gathered there, including, besides the two hosts and the abovementioned Sturge Moore and Savage, also the poet and dramatist duo “Michael Field,” and the Decadent poet-turned-Catholic priest John Gray.

Shannon contributed more than just lithographs to The Dial, but it is clear from the predominance of work in this medium that it was his artistic focus at the time. In a magazine in which artisanal production methods were so conspicuous, it is no doubt significant that for lithography—unlike for painting—no photographic reproduction methods would need to be used to do the original design justice. In the table of contents, wood engravings were boasted to be “designed and engraved on the wood” by the one artist, just as most of the lithographs were indicated to have been “drawn on the stone and bitten by Charles H. Shannon.” This precise stipulation is characteristic for the magazine; those that were not produced in this way would have been so-called “transfer lithographs,” with the designs drawn on paper and then transferred onto the stone, a process seen by purists as inauthentic because it obviates some very particular technical skills (cf. Sickert 667). Shannon had started experimenting in the art only the year before the first Dial came out, and some of his earliest but also most acclaimed lithographs were featured in the magazine. It was on the strength of these publications alone that he was declared “the greatest English lithographer of the present time” in an 1895 profile in The Sketch , a popular illustrated weekly with a prominent interest in art. Shannon also contributed lithographs to the first three issues of The Savoy.

The Dial was, as admitted in its subtitle, “ An Occasional Publication,” and its five self-published issues appeared irregularly over the span of eight years. As Lorraine Janzen Kooistra argues in her general introduction to this magazine, it is best seen as a means for the contributors to publicize their talents among an insider audience of artists, authors, and publishers, and certainly never intended as a source of direct income. The two issues of the annual The Pageant , appearing in 1896 and 1897, as explained by Frederick King on this site, are a different matter. Headed by Shannon (as art editor) and experienced editor Gleeson White (the literary editor), who had recently made the wide-ranging art journal The Studio (1893–1964) an international bestseller, and published by the ambitious firm of Henry & Co, The Pageant aimed at a wider audience. Every member of the coterie behind The Dial makes an appearance here too, but their work in the latter magazine appeared together with original contributions by a diverse range of artists and authors, and a number of photographic reproductions after famous artists such as Whistler or Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882). This shows that The Pageant, unlike The Dial, was also attempting to include uninitiated readers.

Ricketts and Shannon moved out of the Vale in 1898, first spending a few years in Richmond, and then, from 1902, dividing their time between Chilham Castle in Kent, where they were hosted by their wealthy patron Sir Edmund Davis (1861–1939), and at the latter’s Landsdowne House in Holland Park. This was an institution furnishing housing and studio space to gifted artists; Others living and working at Landsdowne House at the time included the painter and poster artist James Pryde (1866–1941) and, already of the next generation, the painter Glyn Philpot (1884–1937). In 1923, in a move that was testimony to their success, Ricketts and Shannon relocated to Townshend House in Regent’s Park, lavishly decorated by former occupant Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912). Here, in 1929, Shannon took a fall while hanging a picture, through which he suffered brain damage and became an invalid, passing away in 1937. Ricketts, who decades earlier had made sacrifices to facilitate the young hopeful’s artistic breakthrough, now nursed him faithfully through his final years (Cook 637). After his death, Shannon has occasionally been the focus of retrospective exhibitions of both his paintings and his lithographs, each arguing that he deserves to be better known. Also, to this end, in 2003, Shannon’s life with Ricketts was the subject of an acclaimed Canadian play by Michael MacLennan, entitled Last Romantics.

©2021, Koenraad Claes, Lecturer in English Literature, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Selected publications about Charles Shannon

- Cook, Matt. “Domestic Passions: Unpacking the Homes of Charles Shannon and Charles Ricketts.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 51, no. 3, July 2012, pp. 618–440..

- Darracott, Joseph. The World of Charles Ricketts. Methuen, 1980.

- —. “Shannon, Charles Haslewood (1863–1937), lithographer and painter.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography . October 8, 2009. Oxford University Press. Accessed 12 May 2021.

- Delaney, J. G. P. Charles Ricketts: A Biography. Clarendon, 1990.

- “The Grafton Galleries: Society of Portrait Painters.” The Athenaeum 3705, 29 October 1898, pp. 613- 4. ProQuest. Accessed 12 May 2021.

- Holmes, C.J. “Velazquez and His Modern Followers.” The Dome, vol. 3, no. 7, July 1899, pp. 89-95. ProQuest. Accessed 12 May 2021.

- Holmes, C. J. Self & Partners (Mostly Self): Being the Reminiscences of C. J. Holmes . Constable, 1936.

- Pennell, Joseph. Lithography & Lithographers: Some Chapters in the History of Art . Second edition. T. Fisher Unwin, 1915.

- Ricketts, Charles. “Prefatory Note for Mr. Shannon’s Lithographs.” Everything For Art: Selected Writings . Edited by Nicholas Frankel, Rivendale, 2014, pp. 139–51.

- Spielmann, Marion H. “Original Lithography: The Present Revival.” Magazine of Art , vol. 20, no. 1, January 1897, pp. 289–96. ProQuest. Accessed 12 May 2021.

- Theocritus. “The Vale Artists, I.—Charles Shannon.” Rev. of The Dial, The Sketch , vol. 8, 23 January 1895, p. 617. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://www.1890s.ca/Dial-Review-The-Sketch-Jan-1895/

- Yeats, William Butler. “Symbolism in Painting.” Ideas of Good and Evil. A. H. Bullen, 1903.

Other cited sources

- Richmond, W. D. The Grammar of Lithography: A Practical Guide for the Artist and Printer . Second edition. Wyman and Sons, 1880.

- Ricketts, Charles. “The Unwritten Book.” The Dial, vol. 2, 1892, pp. 25-28. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0 , Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/dialv2-ricketts-unwritten/

- Ricketts, Charles. “Puvis de Chavannes.” Pages on Art. Clarendon, 1913.

- Sickert, Walter. “Transfer Lithography.” Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art vol. 82, no. 2148, 26 December 1896, pp. 667-8. ProQuest. Accessed 12 May 2021.

Publications by Charles Shannon available from Yellow Nineties 2.0

Lithographs

- “Illustration to A Glimpse of Heaven.” The Dial, vol. 1, 1889, AF. Dial Digital Edition , edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/dialv1-shannon-heaven-af/

- “Return of the Prodigal.” The Dial, vol. 1, 1889, AB. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. The Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/dialv1-shannon-prodigial-ab/

- “Repeated Bend.” The Dial, vol. 2, 1892, AC. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. The Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/dialv2-shannon-bend-ac/

- “Shepherd in a Mist.” The Dial, vol. 2, 1892, AC. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. The Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/dialv2-shannon-shepherd-aa/

- “With Viol and Flute.” The Dial, vol. 2, 1892, AD. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020.The Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/dialv2-shannon-viol-ad/

- “A Romantic Landscape.” The Dial, vol. 3, 1893. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://1890s.ca/dialv3-shannon-romantic-AA/

- “An Intruder.” The Dial, vol. 3, 1893. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://1890s.ca/dialv3-shannon-intruder-AF/

- “White Nights.” The Dial, vol. 3, 1893. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://1890s.ca/dialv3-shannon-white-nights/

- “A Lithograph.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, p. 29. The Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2018-2019. Yellow Nineties 2.0 , Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/savoyv1_shannon_lithograph

- “Delia.” The Dial, vol. 4, 1896. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://1890s.ca/dialv4-shannon-frontispiece/

- “Atalanta.” The Dial, vol. 4, 1896. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://1890s.ca/dialv4-shannon-atalanta-AB/

- “Salt Water.” The Savoy, vol. 2, April 1896, p. 11. The Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2018-2019. Yellow Nineties 2.0 , Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/savoyv2_shannon_salt/

- “The Stone Bath.” The Savoy, vol. 3, July 1896, p. 13. The Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2018-2019. Yellow Nineties 2.0 , Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/savoyv3_shannon_stone/

- “The Infancy of Bacchus.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019-2020, https://1890s.ca/dialv5-shannon-frontispiece/

- “The Dressing Room.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019-2020, https://1890s.ca/dialv5-shannon-dressing-AB/

- “The White Watch.” The Pageant, vol. 1, 1896, p. 239.

- “A Wounded Amazon.” The Pageant, vol. 2, 1897, p. 85.

Original wood engravings

- “The Topmost Apple.” The Dial, vol. 3, 1893. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://1890s.ca/dialv3-shannon-apple-AH/

- “December.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019-2020. https://1890s.ca/dialv5-shannon-december-AA/

Reproductions of paintings and drawings

- “Circe the Enchantress.” The Dial, vol. 1, 1889, AG. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/dialv1-shannon-enchantress-ag/

- “The Queen of Sheba.” The Dial, vol. 1, 1889, AD. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/dialv1-shannon-sheba-ad/

- “A Study of Mice.” The Dial, vol. 4, 1896. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://1890s.ca/dialv4-shannon-mice-AA/

- “A Romantic Landscape.” The Pageant, vol. 1, 1896, p. 211.

- “A Study in Sanguine and White.” The Pageant, vol. 2, 1897, p. 71.

Prose fiction

- “A Simple Story.” The Dial, vol. 1, 1889, pp. 5-8. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/dialv1-shannon-simple-story/

MLA citation:

Claes, Koenraad. “Charles Haslewood Shannon (1863–1937),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0 , edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021, https://1890s.ca/shannon_bio/