XML PDF

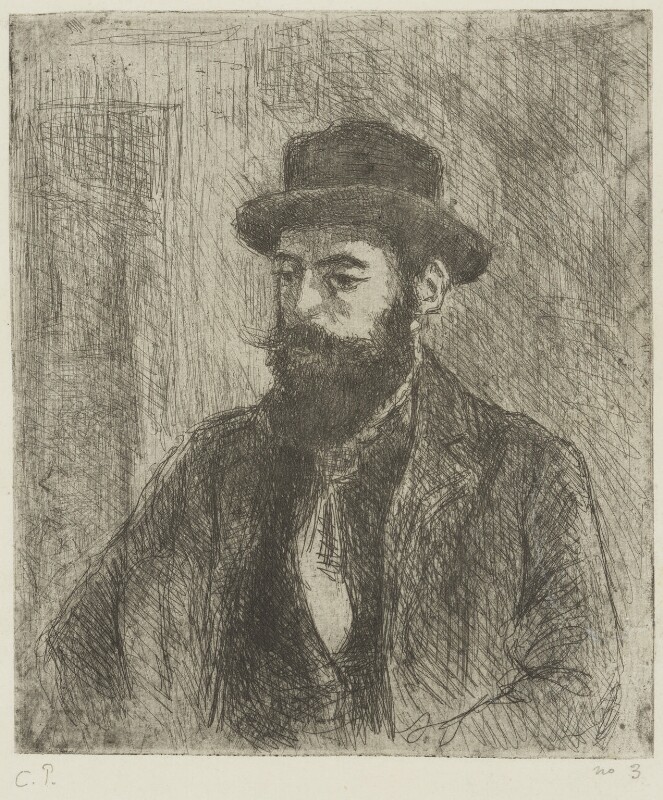

Lucien Pissarro

(1863 – 1944)

Lucien Pissarro was born in Paris in 1863, the eldest of seven children of the French Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) and Julie Vellay (1839-1926). During his early years the family moved often, spending time not only in Paris but also Pontoise, Louveciennes, Brittany, London (during the Franco-Prussian War), and Osny. Lucien followed in his father’s footsteps and trained as an artist. As he began to paint and draw, he was deeply influenced by his father’s work along with the work of other Impressionists, including Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919). In future years, the artists Georges Seurat (1859-1891), Paul Signac (1863-1935), and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) would also influence his work. As a young adult he studied art in both France and England, spending much of 1883-84 living in London with his uncle Phineas Isaacson, a successful merchant, and his family. In London, Lucien was exposed to the old masters as well as art of his contemporaries, often visiting the British Museum and the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) and sketching from their collections. His father’s guidance remained strong, and over this year a lifelong pattern of correspondence began between father and son, with letters, drawings, and prints often exchanged between the two artists. In March of 1883 Camille writes to his son: “My Dear Lucien, You do indeed show strength of will in harnessing yourself to English, nothing but English, … and your future, too, who knows?—do not give up drawing, draw often, always from nature, and whenever possible consult the primitives.—If you could only be persuaded that no other activity is so intelligent and agreeable” (Rewald, Letters 24). It was during this year abroad that Lucien seems to have decided to dedicate his life to an artistic career and, through introduction by the Isaacsons, also met his future wife, Esther Bensusan (1870-1951), who would become not only his partner in marriage but also in artistic endeavours.

In 1884 Lucien returned to France, and remained there for much of the next six years. He soon found employment in Paris through an apprenticeship with the printer François Marie Manzi, director of illustrated publications for Goupil, an international fine art dealership and print publishing firm that specialized in reproductive prints. Through Manzi’s instruction, Lucien learned chromolithography, a method for producing multi-colour prints. He trained in the separation of colours, and while he found the work to be oppressive, he came to recognize how important drawing skills were to the printmaking process (Genz 23-24). While employed by Manzi, he also undertook independent commissions to create drawings for publication in various periodicals, including La Vie Franco-Russe (1888), La Vie moderne (1879-1883), and Le Chat noir (1882-1895). During this period, he also continued to paint, with a focus on landscapes, and exhibited with his father at the last Impressionist exhibition in 1886. In the same year he exhibited at the Societé des Artistes Indépendants for the first time, later exhibiting with the group as a Neo-Impressionist. Due to a growing interest in children’s book illustration and the book manufacturing process, he also began to experiment with wood engraving, a relief printmaking process in which the image is incised into the prepared end-grain surface of a hardwood block, allowing for finely carved detail that could withstand the pressure of repeated printings for book or magazine publication. This experiment would have a profound impact on his career.

He studied with the artist Auguste-Louis Lepère (1849-1918), who by the 1880s was well-established as a leading printmaker in France and proponent of the revival of the technique of wood engraving. Lepère was recognized not only for his prolific output as a wood engraver and etcher, but also for his innovative methods and use of coloured printing papers. Lucien’s early employment with Manzi, coupled with his training with Lepère, provided him with both the skills and sense of experimentation that would become central to his future work in illustration, book design, and printing. It would also allow him to engrave his own illustrations rather than employ a commercial engraver, thereby reducing production costs and enabling him to retain complete artistic control over his designs.

In 1886 he was commissioned by the French illustrated magazine Revue Illustrée (1885-1912) to produce a series of four wood engravings illustrating the story “Infortunes de mait’Lizard” by Octave Mirbeau. Pissarro’s published designs clearly show the influence of the British mid-Victorian illustrator Charles Keene (1823-1891), whose work Lucien greatly admired. The illustrations were praised within his circle; however, they received harsh reviews. He sought to publish additional illustrations for journals as well as an illustrated children’s book of his own design, but was not successful in securing commercial publishers. Disappointed by his early experiences in the Parisian publishing world, in 1890 Pissarro returned to England, where the burgeoning fine press movement offered a more agreeable environment for his printmaking and publishing interests as well as his socialist beliefs. While he would return to France regularly throughout the rest of his life, England became his home and the centre for his artistic output. As the scholar Marcella Genz writes: “He was an artist who had to remove himself from his French milieu in order to find his own distinctive style” (121).

Shortly after his arrival in London in November 1890, Pissarro was introduced—through the poet John Gray—to Charles Ricketts, who eventually became his close friend, mentor, and publisher. Ricketts, a highly skilled wood engraver who spoke fluent French and was interested in French Symbolist literature and art, had seen Pissarro’s illustrations in Revue Illustrée (Moore 5). He approached wood engraving as an independent art form rather than merely a reproductive medium, which appealed to Pissarro’s artistic ambitions. Ricketts and his partner Charles Haslewood Shannon lived at the Vale in Chelsea in the former home of James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), and later founded the influential Vale Press (1896-1904).

Through Ricketts, Pissarro was introduced to artists, writers, and publishers deeply invested in English book illustration, typography, printing, and book binding, including members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle and the Arts and Crafts movement: Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893), William Michael Rossetti (1829-1919), Walter Crane, and Emery Walker (1851-1933), among others, plus artists and writers associated with Ricketts’s Vale group, including Thomas Sturge Moore, Reginald Savage (active 1866-1932), and Oscar Wilde. In 1891, Pissarro lectured on Impressionism at the Art Workers Guild, an organization formed in London in 1884 by a group of young architects and designers to promote unity between the arts, with emphasis on craftsmanship and artisanal production.

By the early 1890s, a few years before founding the abovementioned Vale Press, Ricketts and Shannon had a growing interest in publishing the work of other artists, and in 1891 published Pissarro’s first portfolio of prints: Twelve Woodcuts in Black and Colours by Lucien Pissarro (also known as The First Portfolio). While the title refers to “woodcuts,” the included works were all in fact wood engravings. In this series, Pissarro began to explore unique methods for carving the blocks and printing in colour, including three multi-block colour prints, where each colour in the image was carefully printed from a separate block. The following year this method of colour printing continued when a small portfolio of six prints after drawings by his father titled Les Travaux des champs (“Rustic Labour”) was published at the Vale, in an edition of 25 copies. Pissarro was also invited to contribute to Ricketts’s and Shannon’s little magazine The Dial, producing five illustrations that appeared across three of the four volumes. His first illustration for this publication, “Sister of the Woods,” published in the second issue (1892), exemplifies Pissarro’s synthesis of his Impressionist style with Pre-Raphaelite subject matter, evoking the illustrations of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), Frederick Sandys (1829-1904), and Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) while maintaining his own slightly naïve linear style and method of engraving. Pissarro’s contributions to periodicals also included decorated endpapers plus one illustration to The Pageant in 1896-97, edited by Charles Shannon and Gleeson White, and two illustrations to The Venture in 1903; both periodicals circulated visual and literary works relating to British aestheticism and notions of integrated book design. Pissarro’s work at the Vale furthered his commitment to fine printing and publishing. He and Ricketts espoused their views on book design and the harmony of text and illustration in their collaborative publication De la Typographie et de l’Harmonie de la Page Imprimée: William Morris et son influence sur les arts et métiers (1898) (“Of Typography and the Harmony of the Printed Page: William Morris and his influence on the Arts and Crafts”).

Pissarro married Esther Bensusan in Richmond in August of 1892. The daughter of a prosperous Jewish merchant and friend of the Isaacson family, Esther had studied at the Crystal Palace School of Art and had learned wood engraving. The couple honeymooned in France, including an eight-month stay at Camille and Julie Pissarro’s new home in Eragny, a commune in the Oise suburb northwest of Paris. Upon their return to England in 1893, they settled in Epping in Essex, and in October of that year their daughter and only child, Orovida Camille Pissarro (1893-1968) was born; she too was to become a successful artist. While he continued to paint, the growing Arts and Crafts movement and Revival of Fine Printing invigorated Lucien’s interests in illustration and book production. In 1894, Lucien and Esther founded the Eragny Press at their home in Epping. The Eragny Press created small, hand-made, labour-intensive books in limited print runs. For example, their first book The Queen of the Fishes (1894), an English adaptation of an old Valois fairy tale, included twelve wood-engraved illustrations (five in colour and seven in black and white), plus decorative ornaments and borders, with special hand-lettered text that was photo-engraved and printed in gray ink. Esther was involved with engraving Eragny blocks from the beginning, and over the years took on a greater role in printing and presswork (Whiteley 42). The Queen of the Fishes is also notable in that some of the illustrations were later reprinted. One of the colour illustrations, printed from five blocks, was reprinted (without the decorative border) in the second volume of The Pageant (1897), appearing with the article “A Note on Original Wood Engraving” by Charles Ricketts, where Pissarro’s technique is described as both uniquely modern as well as evoking skilled printmakers of the past (Ricketts 265). Similarly, one of the black and while illustrations was reprinted in volume 1 of The Venture (1903).

Ricketts and his new business partner, William Llewellyn Hacon (1860-1910), agreed to distribute Eragny books through the Vale Press for a percentage of sales. This business arrangement with Hacon and Ricketts continued until the Vale Press closed in 1904. Henceforth, the Pissarros financed the Eragny Press themselves, having moved from Epping to Bedford Park in Chiswick, West London, in 1897 and then to “The Brook,” a nearby house and studio on Stamford Brook Road in 1902. However, due to the high production costs and their meticulous standards, they rarely made a financial profit. The press was active between 1894 and 1914, producing 32 titles. Found within these Eragny books are over 300 wood-engraved illustrations, borders, and capitals. Editions ranged in size from twenty-seven to 226 copies, and the average output was between one and two books per year (Genz 145). In 1903 Lucien designed a custom typeface for the Eragny Press publications, called the “Brook” type, which was inspired by typefaces designed by Nicolas Jenson (1420-1480) – much like the Golden Type created by William Morris (1834-1896) for his Kelmscott Press. The Kelmscott influence—greater than that of the Vale’s less ornate style—can further be seen in the use of numerous decorative elements, principles of page design, and unification of illustration and text. After 1903, Eragny books are particularly noted for their increasingly adept use of colour printing, with illustrations, such as those for Some Old French and English Ballads (1905) and Album de Poèmes Tirés du Livre de Jade (1911), printed in multiple colours using different woodblocks. As Lora Urbanelli observes:

In this work Lucien truly flourished. His renewed palette (opposing hues of red and green, yellow and purple) revealed his background in Neo-Impressionist colour theory, but his distinctive accomplishment was due in part to subtle inking. Lucien almost never printed a colour flat. Each block, cut to print a single colour, was mottled to produce a pattern and inked with a delicate tint. The blocks of pale colour were then carefully printed one over the next so that the viewer had to look closely to understand what was causing the spectral vibration. The colours were printed wet on wet, and the paper was kept damp so that the sheet did not shrink between colour applications. Occasionally, Lucien even published an entire volume on coloured papers (Urbanelli, Wood Engravings 35).

During the First World War, sales of Eragny books declined as the Pissarros began to lose contact with many of the Press’s international collectors. The inability to obtain materials such as handmade paper imported from France and ink from Germany soon brought production at the Eragny Press to a halt. In her assessment of the Eragny books, Genz writes: “In creative vision, original style, and meticulous production skills, no other private press surpasses the art of an Eragny Press book. Combining the principles of Arts and Crafts book design and of impressionist sensation, Lucien Pissarro created the most original books of the private press movement and can be credited also with provoking an interest in France in the livre d’artiste” (134). Pissarro’s chosen role as artist-craftsman led to uniquely personal and technically sophisticated book designs.After 1914, Pissarro returned his artistic focus to painting, with a notable exception of designing the Distel typeface for the Dutch printer Jean François van Royen (1878-1942) in 1916. Impressionist art was now more popular in England and sales of his paintings increased, easing the Pissarros’ financial burdens. He had been affiliated with the Fitzroy Street Group and the Camden Town Group, though Pissarro resigned from the latter before their first exhibition. The artist and art critic James Bolivar Manson (1879-1945) became a close friend and began publishing on Pissarro’s illustrations (1913) and paintings (1916) and promoted his work to collectors. Pissarro became a British citizen in 1916. In 1919, he formed the Monarro Group (merging the surnames of Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro) to exhibit art inspired by French Impressionism, with Manson serving as the group’s secretary in London and Théo van Rysselberghe (1862-1926) as the secretary in Paris; the group held exhibitions in 1920 and 1921, but ceased operations shortly thereafter. Manson became Director of the Tate Gallery in 1930, having worked there since 1912. Due to their friendship, Lucien Pissarro held an “unacknowledged influence on the Tate’s acquisitions at this time” (Jenkins and Bonett 3) and during Manson’s tenure gifted numerous works by Camille Pissarro to the Tate and the National Gallery, further influencing the reception of French Impressionism in England. In the 1920s and 1930s his paintings were often exhibited, sometimes alongside those of his father and daughter. From 1934 to 1944 he exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy in London. After his death in 1944, memorial exhibitions of his prints and paintings were held in 1946 and 1947.

©2022, Joanna Karlgaard, Assistant Curator of Prints, Drawings & Photographs, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Selected Publications by Lucien Pissarro:

- “The Crowning of Esther.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 129. Venture Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2021. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021, https://1890s.ca/vv1-pissarro-esther/

- Decorated endpapers. The Pageant, vols. 1-2, 1896-1897. Yellow Nineties 2.0 Database of Ornament, https://ornament.library.ryerson.ca/items/show/209

- Ricketts, Charles and Pissarro, Lucien. De la Typographie et de l’Harmonie de la Page Imprimée: William Morris et son influence sur les arts et métiers. Paris: Floury; London: Hacon & Ricketts, Ballantyne Press, 1898.

- “Le Petit Chaperon Rouge.” The Dial, vol. 4, 1896. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://1890s.ca/dialv4-pissarro-chaperon-AC/

- The Letters of Lucien to Camille Pissarro, 1883–1903. Edited by Anne Thorold. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993 (1st ed.).

- Notes on the Eragny Press, and a Letter to J.B. Manson. Edited with a supplement by Alan Fern. Cambridge: Privately printed, 1957.

- “The Queen of the Fishes.” The Pageant, vol. 2, 1897, p. 259. Pageant Digital Edition, edited by Frederick King and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2021. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021 https://1890s.ca/pag2-pissarro-woodcut/

- “Queen of the Fishes.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p.37. Venture Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2021. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021, https://1890s.ca/vv1-pissarro-fishes/

- Rossetti. London: T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1905.

- “Ruth, Orpah, and Naomi” and “Ruth the Gleaner.” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. The Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://1890s.ca/dialv5-pizzarro-ruth-AG/

- “Sister of the Woods.” The Dial, vol. 2, 1892, AB. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2019-2020. The Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/dialv2-pissarro-sister-ab/

- “Solitude.” The Dial, vol. 3, 1893. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://1890s.ca/dialv3-pissarro-solitude-AG/

- Twelve Woodcuts in Black and Colours by Lucien Pissarro (also known as The First Portfolio). London: Published by Ch. Shannon and C. Ricketts in the Vale, Chelsea, 1891 (completed in 1892).

Selected Eragny Press books:

- Rust, Margaret. The Queen of the Fishes. London: Eragny Press / Vale Publications, 1894.

- Old Testament. The Book of Ruth and the Book of Esther. London: Eragny Press / Sold by Hacon and Ricketts, 1896.

- Laforgue, Jules. Mortalités Légendaires, Vol. I. London: Eragny Press / Sold by Hacon and Ricketts, 1897.

- —. Mortalités Légendaires, Vol. II. London: Eragny Press / Sold by Hacon and Ricketts, 1898.

- Perrault, Charles. Deux Contes de ma Mere l’Oye – La Belle au Bois Dormant et le Petit Chaperon Rouge. London: Eragny Press / Sold by Hacon and Ricketts, 1899.

- Villon, François. Les Ballades de Maistre François Villon. London: Eragny Press / Sold by Hacon and Ricketts, 1900.

- Flaubert, Gustave. Un Coeur Simple. London: Eragny Press / Sold by Hacon and Ricketts, 1901.

- Flaubert, Gustave. Hérodias. London: Eragny Press / Sold by Hacon and Ricketts, 1901.

- Bacon, Francis. Of Gardens. An Essay. London: Eragny Press / Sold by Hacon and Ricketts, 1902.

- Ronsard, Pierre de. Choix de Sonnets. London: Eragny Press / Sold by Hacon and Ricketts, 1902.

- Browning, Robert. Some Poems by Robert Browning. Hammersmith: The Eragny Press, 1904.

- Steele, Robert (ed.). Some Old French and English Ballads. Hammersmith: The Eragny Press, 1905.

- Rossetti, Christina G. Verses by Christina G. Rossetti. Hammersmith: The Eragny Press, 1906.

- Nerval, Gérard de. Histoire de la Reine du Matin et de Soliman Ben Daoud. Hammersmith: The Eragny Press, and Paris: Société des Cent Bibliophiles, 1909.

- Gautier, Judith. Album de Poèmes Tirés du Livre de Jade. Hammersmith: The Eragny Press, 1911.

- Field, Michael [Katherine Harris Bradley and Edith Emma Cooper]. Whym Chow: Flame of Love. Hammersmith: The Eragny Press, 1914.

Selected Publications about Lucien Pissarro:

- Andreini, J. M. “Notes on Book-plates by Esther and Lucien Pissarro; and on Their Eragny Press.” Ex Libran vol. 1, no. 3, 1912, pp. 39-43.

- Bailly-Herzberg, Janine and Aline Dardel. “Les Illustrations françaises de Lucien Pissarro.” Nouvelles de l’estampe, vol. 54, November-December 1980, pp. 8-16.

- Bass, Jacquelyn and Richard S. Field, eds. The Artistic Revival of the Woodcut in France, 1875-1895. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Museum of Art, 1984.

- Beckwith, Alice H.R.H. Illustrating the Good Life: The Pissarros’ Eragny Press, 1894-1914. New York: The Grolier Club, 2007.

- —. “Pre-Raphaelites, French Impressionists, and John Ruskin, Intersection at the Eragny Press” in Pre-Raphaelite Art in its European Context, edited by Susan Casteras and Alicia Craig Faxon, pp. 175-90. London and Toronto: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1995.

- Blatchly, John, John Bensusan-Butt. “The wood engraved bookplates of Lucien and Esther Pissarro.” Bookplate, vol. 15, no. 1, March 1997, pp. 21-37.

- Chambers, David. Lucien Pissarro: Notes on a Selection of Wood-Blocks Held at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1980.

- Clément-Janin, Noël. “Lucien Pissarro: Peintres-graveurs contemporains.” Gazette des Beaux-arts, vol. 15, 1919, pp. 337-51.

- Fern, Alan Maxwell. The wood-engravings of Lucien Pissarro with a catalogue raisonné. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chicago, 1960.

- Genz, Marcella D. History of the Eragny Press 1894–1914. New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press; London: British Library, 2004.

- Jenkins, David Fraser, and Helena Bonett, “Lucien Pissarro 1863–1944,” artist biography, February 2011, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/lucien-pissarro-r1105344.

- Lloyd, Christopher. “An Uncut Wood-Block by Lucien Pissarro,” Print Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 4, December 1985, pp. 309-14.

- Manson, John Bolivar. “Notes on Some Wood-Engravings of Lucien Pissarro.” The Imprint, April 17, 1913, pp. 240-47.

- Moore, Thomas Sturge. A Brief Account of the Origin of the Eragny Press & a Note on the Relation of the Printed Book as a Work of Art to Life. Hammersmith: Eragny Press, 1903.

- Perkins, Geoffrey. The Gentle Art: A Collection of Books and Wood Engravings by Lucien Pissarro. Zurich: L’Art ancient S.A., 1974.

- Pratt, Barbara. Lucien Pissarro in Epping. Loughton, Essex: Barbara Pratt Publications, 1982.

- Rewald, John. “Lucien Pissarro: Letters from London, 1883-1891.” Burlington Magazine, vol. 91, 1949, pp. 188-92.

- —. Camille Pissarro: Letters to his son Lucien. New York: Pantheon Books, 1943.

- Ricketts, Charles. “A Note on Original Wood Engraving.” The Pageant, vol. 2, 1897, pp. 253-66. Pageant Digital Edition, edited by Frederick King and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2021. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021. https://1890s.ca/pag2-ricketts-engraving/

- Theocritus. “The Vale Artists, III.—Lucien Pissarro.” Rev. of The Dial, The Sketch, vol. 9, 17 April 1895, pp. 615-616. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://www.1890s.ca/Dial-Review-The-Sketch-Apr-17-1895/

- Thorold, Anne. A Catalogue of the Oil Paintings of Lucien Pissarro. London: Altheney Books, 1983.

- Urbanelli, Lora S. The Book Art of Lucien Pissarro: with a Bibliographical List of the Books of the Eragny Press 1894-1914. Wakefield, Rhode Island: Moyer Bell, 1997.

- —. The Wood Engravings of Lucien Pissarro: A Bibliographical List of Eragny Books. Oxford: The Ashmolean Museum, 1994.

- Whiteley, Jon (ed.). Lucien Pissarro in England: The Eragny Press, 1895-1914. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2011.

MLA citation:

Karlgaard, Joanna. “Lucien Pissarro (1863-1944),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/lpissarro_bio/