XML PDF

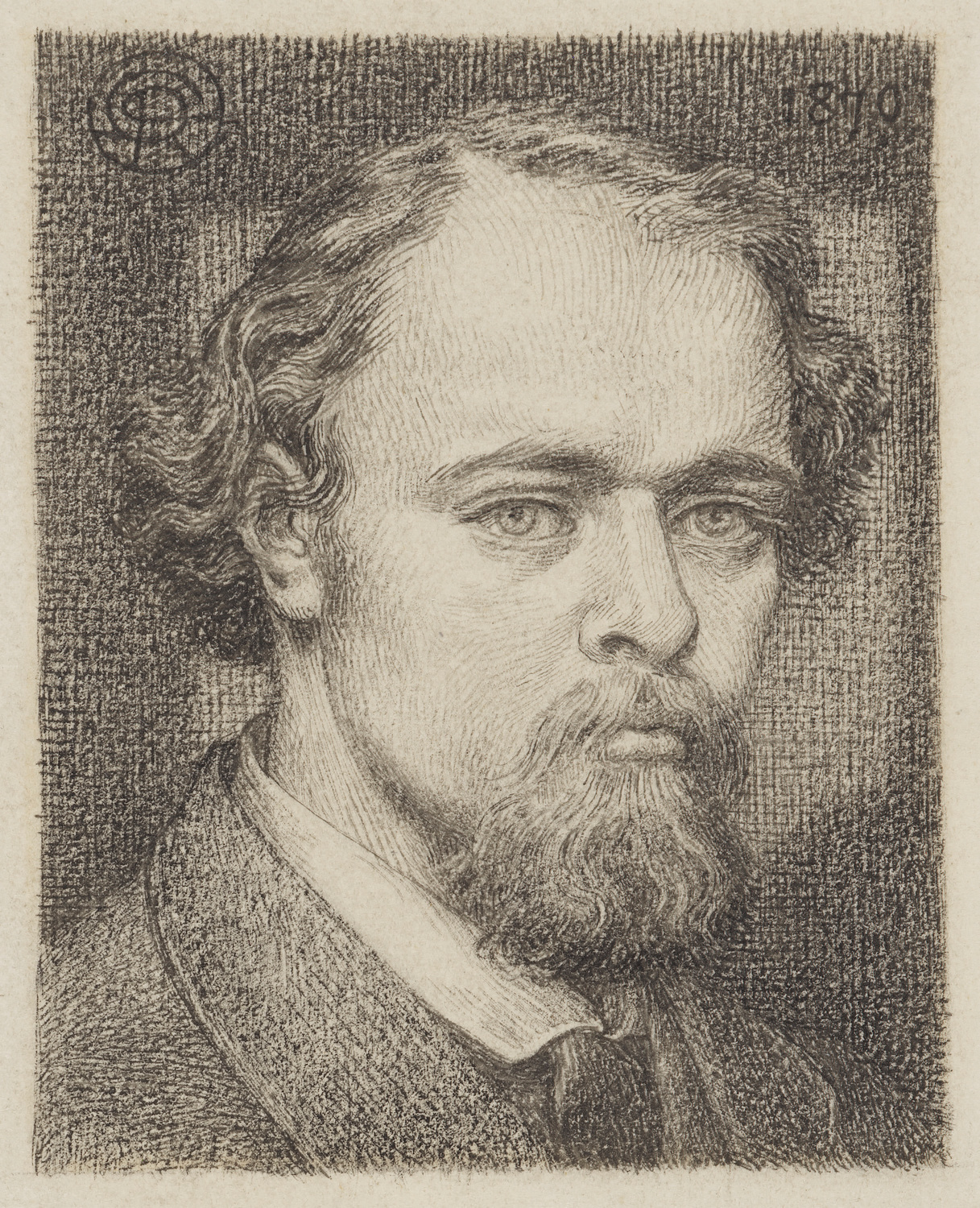

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

(1828 – 1882)

Artist, writer, translator, and designer Dante Gabriel Rossetti was one of the major painters and poets of the Victorian era. As two of the dominant critics of the period—John Ruskin (1819–1900) and Walter Horatio Pater (1839–1894)—noted, Rossetti represented one of the most original and influential artistic forces of the nineteenth-century. Ruskin, writing shortly after the artist’s death, claimed that Rossetti “should be placed first on the list of men, within my own range of knowledge, who have raised and changed the spirit of modern Art: raised, in absolute attainment; changed, in direction of temper” (269). Pater observed that Rossetti’s poetry represented “perfect sincerity, taking effect in the deliberate use of the most direct and unconventional expression, for the conveyance of a poetic sense which recognised no conventional standard of what poetry was called upon to be” (229). Rossetti’s influence continued after his death in 1882, not only on developments in the Aesthetic and Symbolist movements, but also on the fin-de-siècle fine printing revival. Rossetti’s impact on late-Victorian little magazines is evident in their reproductions of his work, references to his pictures and poetry, and homages to The Germ, the magazine of art and literature he co-founded with fellow Pre-Raphaelites in 1850.

Born Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti, he was, in the Victorian era, the most celebrated member of a highly idiosyncratic and intellectual Anglo-Italian household. Rossetti was the second child of the Italian political exile and scholar Gabriele Rossetti (1783–1854) and Frances Rossetti (née Polidori) (1800–1886). Through his mother, he was the nephew of Romantic writer and Byron’s personal physician John Polidori (1795–1821). All of the Rossetti siblings have been recognised as exceptional. His sister, Maria Francesca (1827–1876), published on Dante and became an Anglican nun. His brother, William Michael (1829–1919), was a writer, editor, and critic, and served as historian and biographer for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His second sister and youngest sibling, Christina (1830-1894), was a major Victorian poet in her own right.

Dante Alighieri (c. 1265–1321) was markedly present during Rossetti’s upbringing. In his preface to The Early Italian Poets (1861), Rossetti states that “[t]he first associations I have are connected with my father’s devoted studies [ . . . ] in those early days, all around me partook of the influence of the great Florentine.” Dante became the single most important influence on Rossetti’s work. His painting and poetry developed in tandem—and frequently drew on similar subjects and sources.

Rossetti began his studies as a painter at the Royal Academy in 1845: it is during this period that he wrote the first version of his remarkably original “The Blessed Damozel” (1846/1847–1881). The poem is now seen as his single most important literary work. During this time, Rossetti met his peers William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) and John Everett Millais (1829–1896). He left the Royal Academy in 1848 to study under Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893). Various accounts of these early events are, notoriously, concocted much later—the actual details lost to history and complicated by Pre-Raphaelite mythology.

Rossetti read widely during these formative years: not just Dante, the Bible, John Keats (1795–1821), and William Shakespeare (1564–1616), but also Thomas Malory (1405–1471), William Blake (1757–1827), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), Lord Byron (1788–1824), Walter Scott (1771–1832), Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809–1892), and Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849). The influence of Blake’s composite art form can be seen on Rossetti’s “double works of art”—each a visual-verbal composite of a picture and poem.

Rossetti, Hunt, Millais, and four other painters and writers founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. Their work, however, provoked significant critical ire when it first appeared. It was attacked as blasphemous, criticised for its medievalism, condemned as ugly due to its minute detail, and mocked for its perspective. Charles Dickens (1812–870) referred to Millais’ depiction of the Virgin Mary in Christ in the House of His Parents (1849–1850) as “so horrible in her ugliness, that [ . . . ] she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster” (512). The initial hostility did not last long. Recognised today as a highly distinctive movement in modern art, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood revolutionised British artistic practices with their commitment to extraordinary detail, brilliant colours, and complex compositions as well as their frequently literary subjects. This stood in stark contrast with the academic art and institutionalised style of the period.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood published their own magazine in 1850 to disseminate their work and ideas. While The Germ: Thoughts towards Nature in Poetry, Literature, and Art only lasted four issues over five months, it had a significant and long-lasting influence. The Germ not only served as the organ of the group; it also became the progenitor of the fin-de-siècle little magazine movement.

The subtitle—Thoughts towards Nature in Poetry, Literature, and Art—gives some sense of the programmatic goals of the magazine and the first issue, published on 1st January 1850, demonstrates the magazine’s range. The first issue features, among other things, a Holman Hunt etching as its frontispiece; Rossetti’s short story “Hand and Soul” (1849); Thomas Woolner’s ballad “My Beautiful Lady” (1849); and an essay on the subject in art. Summarising what should be seen as a consistent structure of The Germ, the advertisement at the end notes that:

This Periodical will consist of original Poems, Stories to develope [sic] thought and principle, Essays concerning Art and other subjects, and analytic Reviews of current Literature —particularly of Poetry. Each number will also contain an Etching; the subject to be taken from the opening article of the month. (Germ, back cover)

The Germ was a brief artistic experiment and a commercial failure—yet it explicitly influenced the little magazines that emerged at the fin de siècle. It served as a model for The Dial: An Occasional Publication (1889-1897). Co-editor Charles Ricketts (1866-1931) was unambiguous on the subject:I wished, in conjunction with a few other artists who thought in common, to re-assert certain traditions—to insist on absolute sincerity in art. Chiefly, however, to emphasise and re-emphasise the importance of design in art. Really, the Pre-Raphaelite Germ was its legitimate precursor. (Ricketts, qtd in Scott, 339; see also “General Introduction: The Dial”)

Moreover, Ricketts explicitly cited Rossetti’s “double work” on “The Sonnet” (“A Sonnet is a moment’s monument”) when setting out The Dial’s editorial policy and explaining his theory of “Document” as “that monument of moods,” conveying “this sense of existence and pre-existence, this sense of time” (“Unwritten Book,” 26). The Germ’s manifesto and short print run would become key characteristics of the little magazines that followed a generation later. The Green Sheaf (1903–1904) is one such example. Eccentric, niche, and in stark contrast to mainstream publications, The Green Sheaf—like The Germ and The Dial—was produced by a group of connected artists and writers. The short-lived Christmas annual, The Pageant (1896-97), was marked as being “a little too much with the spirit of Pre-Raphaelite art” (529) by The Academy (1869–1902) in their mostly positive review. The Pageant featured several of Rossetti’s works, including his drawing, The Magdalene at the House of Simon the Pharisee (1858), which served as the first volume’s frontispiece. Fittingly for a magazine where “mythical and biblical references [ . . . ] defy historical and cultural boundaries, confusing time, place, and order” (King, “General Introduction: The Pageant”), Rossetti’s image seems to transport the biblical narrative to Quattrocento Florence and its composition is highly unusual. At the end of the 1890s, The Germ was reprinted by Thomas Mosher (1898). It would be reprinted again, this time with a preface and other details from William Michael Rossetti, after the close of the decade (1901).In 1856, William Morris (1834–1896), Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), and five other undergraduates produced The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine. The students—who referred to themselves as “The Brotherhood”—were manifestly influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite magazine The Germ. Taking on the mantle of aesthetic revolt, the magazine existed for a single year and ran for 12 issues. Rossetti contributed three poems to The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, including a revision of the “Damozel” that had first been published in The Germ, forming a further link between the magazines. In 1857–1859, seven artists including Rossetti, Morris, and Burne-Jones painted a set of murals for the Oxford Union Society.

Rossetti’s work and Pre-Raphaelitism were also circulated in America in the 1850s and 1860s via several magazines. The Crayon (1855–1861) reprinted a number of Rossetti’s poems from The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, linking it to Pre-Raphaelitism but also formalising the connection between these two magazines, the painter-poet, and The Germ. The New Path (1863–1865), which shared much of The Germ’s ethos and approach, consistently praised Rossetti’s work—bringing his writing and his art to American audiences.

Fin-de-siècle little magazines led a sustained revaluation and revival of the wood-engraved illustrations designed by Rossetti and other Pre-Raphaelite artists. The second volume of The Pageant, for example, carried Rossetti’s pen-and-ink drawing Hamlet and Ophelia (1858): the black-and-white illustrative style is distinctive and is a key example of fin-de-siècle recirculation of Pre-Raphaelite art and design (57). The wood-engraved illustrations were produced during the 1860s—termed “A Golden Decade in English Art” by Joseph Pennell (1857–1926) in first issue of The Savoy (1896)—and these included illustrations for the very book that launched the “Golden Decade.” Thirty of the fifty-two woodcut illustrations featured in the lavish Moxon Tennyson (1857) were designed by Rossetti, Millais, and Holman Hunt. These—and Rossetti’s illustrations for his sister Christina’s Goblin Market (1862)—influenced Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) and his illustrations of Salome (1894) by Oscar Wilde (1854–1900). Ricketts and Laurence Housman (1865-1959) were influenced not only by Rossetti’s black-and-white designs but also by their reproductive medium. Each relied extensively on wood-engraved illustrations in the magazines they edited—The Dial and The Venture (1903) respectively.

The image of the “Rossetti woman” has dominated the artist’s public reputation. It has been strongly associated with both Symbolism and Aestheticism and is crucial to understanding Rossetti’s reception and legacy in the 1890s. The influence of Titian (1488/90–1576) and Venetian art of the Italian High Renaissance is evident. Rossetti’s pictures are sensuous, voluptuous, desirous, fleshly, luxuriant, and littered with symbols. They also share a figurative style: oversized figures, abundant heads of hair, full lips, rich flesh, thick necks, and emotive eyes. They are frequently backed with, or flanked by, complex floral patternings. Rossetti mostly used the models Alexa Wilding (1847–1884), Fanny Cornforth (1835–1909), and Jane Morris (1839–1914). Rossetti’s riveting personal life and relationship with his own models has undoubtedly coloured much of the critical reception of these pictures. Key examples include Bocca Baciata (1859), Proserpine (1874), The Blessed Damozel (1875–1878), Astarte Syriaca (1876–1877), Lady Lilith (1868), and The Blue Bower (1865). Pennell’s “A Golden Decade in English Art” in The Savoy explicitly uses the term when discussing Rossetti’s illustrations for Christina’s Goblin Market. In his essay, Pennell contrasts the frontispiece figure (“a country girl”) with the figure in the title-page vignette (“a stately Rossetti woman”) (116). The Pageant printed two images of this type, including Rossetti’s major oil painting La Pia [De’ Tolomei] (1868–1880) in volume 2 and Monna Rosa (1867) in volume 1. The latter was accompanied by an ekphrastic poem of the same title by French avant-garde poet Paul Verlaine (1844-1896). He was commissioned to respond to a painting by James McNeil Whistler, but responded to Rossetti’s work instead, perhaps in homage to the poet-painter’s “double work” form (Creasy, np).

Rossetti’s reluctance to exhibit has generated a number of differing interpretations. The idea of Rossetti as a reclusive and possibly oversensitive artist—which persists today—was also circulating in the 1890s. Writing in volume 6 of The Savoy, Arthur Symons (1865–1945) generously argued that: “Art, let it be remembered, must always be an aristocracy; it has been so, from the days when Michel Angelo dictated terms to Popes, to the days when Rossetti cloistered his canvases in contempt of the multitude and its prying unwisdom” (57). Rossetti, in reality, sold most of his paintings to a small number of wealthy patrons—and frequently suggested subjects for commission.

Turning from his visual to literary work necessitates a return to the 1860s—the decade Rossetti refocused his attention on writing. His first book was one of translations, The Early Italian Poets (1861), published at the start of the decade: it is often treated as an original work by Rossetti because of its commitment to translating the works “anew” rather than literally. He also provided commentaries for the Life of William Blake (1863) by Alexander Gilchrist (1828–1861). His poetry during this period is animated and enlivened by the “double work” form he was perfecting: as such, many of his poems take the same title as one of his pictures. Together, they develop and elaborate on a shared visionary ideal or subject.

Jerome McGann argues that Poems (1870), Rossetti’s first book of original poetry, is “perhaps the most influential book of poetry published in the second half of the nineteenth century in England” (“Scholarly Commentary,” np). Poems established Rossetti’s significance as a poet. It marked the first publication of the dramatic monologue “Jenny,” “The House of Life” sonnet sequence, and the “Sonnets for Pictures” subcategory. The design, too, was notably original, opening up new approaches to the book as a material object and influencing the fin-de-siècle revival of fine printing. The reviews were many and mostly positive. Robert Buchanan’s “The Fleshly School of Poetry” (1871), however, sparked one of the notable cultural controversies of the nineteenth century. Rossetti was accused of deploying highly sexualised imagery and his poetry and art were declared a source of moral corruption.

Rossetti suffered a form of mental breakdown in June 1872—caused, in part, by some of the negative reviews of Poems. Yet he also painted some of his most distinctive and well-known pictures during his final decade, including Proserpine (1871–1882), The Blessed Damozel (1875-1878), and Astarte Syriaca (1876–1877). His relationship with Jane Morris ended and, with his behaviour alienating various friends, his “sense of isolation prompted him to take up with admirers and followers rather than equals” (Bullen 252). These included his future biographer William Sharp (1855-1903), who became a prominent contributor to fin-de-siècle little magazines The Pagan Review (1892) and The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal (1895–1896/7). While Rossetti’s health failed, his poetry was increasingly anthologised in Britain and America during this period, and his mastery of the sonnet form was increasingly recognised. Housebound in Cheyne Walk, London, with paralysis of the leg, kidney failure, and other health problems, he was increasingly unstable and addicted to both alcohol and chloral hydrate. On doctor’s advice, Rossetti went to stay with a friend at their country house in Birchington, Kent, where he died on Easter Sunday, 9th April 1882.

Rossetti’s impact on European literature and art, including on Aestheticism and Symbolism, is significant and well-documented. Rossetti is rightly recognised as one the most important painters and poets of the Victorian era and he possessed a rare—possibly unsurpassed—talent for combining the two art forms. His considerable influence on the development of the little magazine as a counter-cultural publishing genre is less frequently acknowledged and remains under-examined. Although Rossetti’s reputation is rightfully assessed and debated within the disciplines of literary and art-historical studies, his interdisciplinary legacy is also significant to the fields of periodicals studies and publishing history.

© 2022 Nicholas Dunn-McAfee, Doctoral Researcher (AHRC), University of York, United Kingdom

Selected Publications by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

- The Early Italian Poets from Ciullo D’Alcamo to Dante Alighieri (1100–1200–1300) in the Original Metres, Together with Dante’s Vita Nuova. London: Smith, Elder, 1861.

- Poems. 1st ed. London: Ellis, 1870.

- Dante and His Circle: With the Italian Poets Preceding Him (1100–1200–1300). London: Ellis and White, 1874.

- “The Sonnet,” 27 April 1880. Doubleworks Exhibit, Rossetti Archive, accessed 15

December 2022,

http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/s258.rap.html

- Poems: A New Edition. London: Strangeways, 1881.

- Ballads and Sonnets. London: Ellis, 1881.

- The Collected Works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, edited by William Michael Rossetti. 2 vols. London: Ellis and Scrutton, 1886.

- The Works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, edited by William Michael Rossetti. London: Ellis, 1911.

- The Collected Poetry and Prose, edited by Jerome McGann. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003.

Selected Publications about Dante Gabriel Rossetti

- Armstrong, Isobel. “The Pre-Raphaelites and Literature.” The Cambridge Companion to the Pre-Raphaelites, edited by Elizabeth Prettejohn, Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 13–31.

- Becker, Edwin, Julian Treuherz, and Elizabeth Prettejohn. Dante Gabriel Rossetti. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2003.

- Broussine, Sylvie, and Christopher Newall. Rossetti’s Portraits. Bath and London: The Holburne Museum and Pallas Athene, 2021.

- Bullen, J. B. Rossetti: Painter and Poet. London: Frances Lincoln, 2011.

- Clifford, David, and Laurence Roussillon, eds. Outsiders Looking In: The Rossettis Then and Now. London: Anthem Press, 2004.

- Donnelly, Brian. Reading Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Painter as Poet. London: Routledge, 2015.

- Faxon, Alicia Craig. Dante Gabriel Rossetti. New York: Abbeville, 1989.

- Grieve, Alastair I. The Art of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: 1. Found. 2. The Pre–Raphaelite Modern Subject. Norwich: Real World Publications, 1976.

- —–. The Art of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Pre–Raphaelite Period 1848–1850. Hingham: Real World Publications, 1973.

- —–. The Art of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Watercolours and Drawings of 1850–1855. Norwich: Real World Publications, 1978.

- —–. “Rossetti and the Scandal of Art for Art’s Sake in the Early 1860s.” After the Pre–Raphaelites: Art and Aestheticism in Victorian England, edited by Elizabeth Prettejohn, Rutgers University Press, 1999, pp. 17–35.

- Helsinger, Elizabeth. Poetry and the Pre-Raphaelite Arts: Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Morris. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

- Holmes, John. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Late Victorian Sonnet Sequence: Sexuality, Belief and the Self. Oxford: Routledge, 2016.

- Marsh, Jan. Dante Gabriel Rossetti: Painter and Poet. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1999.

- McGann, Jerome. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Game That Must Be Lost. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

- —–. “The Poetry of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882).” The Cambridge Companion to the Pre-Raphaelites, edited by Elizabeth Prettejohn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. 87–102.

- —–. “Scholarly Commentary: Poems (1870).” Rossetti Archive, Accessed 20 June

2021.

http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/1-1870.raw.html.

- Prettejohn, Elizabeth. “The Painting of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.” The Cambridge Companion to the Pre-Raphaelites, edited by Elizabeth Prettejohn, Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 103–115.

- —–. The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites. London: Tate Publishing and Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Pater, Walter. “Dante Gabriel Rossetti.” Appreciations, with an Essay On Style. London: Macmillan, 1889, pp. 213–227.

- Rossetti, William Michael. Dante Gabriel Rossetti as Designer and Writer. London: Cassell & Company, Limited, 1889.

- —–. Dante Gabriel Rossetti: Classified Lists of His Writings with the Dates. London: Privately Printed, 1906.

- Sharp, William. Dante Gabriel Rossetti: A Record and a Study. London: Macmillan, 1882.

- Stauffer, Andrew. “The Germ,” The Cambridge Companion to the Pre-Raphaelites, edited by Elizabeth Prettejohn, Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 76–86.

- Stephens, F. G. Dante Gabriel Rossetti. London: Seeley & Co., 1894.

- Surtees, Virginia, ed. The Paintings and Drawings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882): A Catalogue Raisonné. 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Secondary References

- Bullen, J. B. Rossetti. Rossetti: Painter and Poet. London: Frances Lincoln, 2011.

- Creasy, Matthew. “Paul Verlaine (1844-1896).” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties

2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre

for Digital Humanities, 2022.

https://1890s.ca/verlaine_bio/

- Dickens, Charles. “From New Lamps for Old Ones.” The Norton Anthology of

English Literature, edited by Stephen Greenblatt and Catherine Robson, tenth

edition, Volume E, W.W. Norton and Company, 2018.

https://contentstore.cla.co.uk/secure/link?id=244aff13-6ed0-e811-80cd-005056af4099.

- The Germ. vol. 1 (January 1850). London: Aylott & Jones, 1850. Rossetti

Archive, accessed 14 December 2022,

http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/ap4.g415.1.1.rad.html

- King, Frederick D. “The Pageant (1896-1897): An Overview,” Pageant Digital

Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital

Humanities, 2019,

https://1890s.ca/pageant_overview/

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “General Introduction: The Dial: An Occasional

Publication (1889-1897).” Dial Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto

Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019,

https://1890s.ca/dial_introduction/

- The Pageant, vol. 2, 1897. Pageant Digital Edition, edited by Frederick King

and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2021. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan

University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021.

https://1890s.ca/pag2-all/

- “Pageant (Book Review).” The Academy. vol. 50, no. 1274, Oct. 17, 1896, p. 90.

http://ezproxy.library.dal.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1298641169?accountid=10406.

Accessed June 20, 2022.

- Pater, Walter. “Dante Gabriel Rossetti” in Appreciations with an Essay On Style. London: Macmillan, 1889, pp. 213–227.

- Pennell, Joseph. “A Golden Decade in English Art.” The Savoy, vol. 1, 1896, pp.

112–124. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen

Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital

Humanities, 2019.

https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-pennell-golden/

- Ricketts, Charles. “The Unwritten Book.” The Dial: An Occasional Publication,

vol. 2, 1892, pp. 25–28. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra,

Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital

Humanities, 2019.

https://1890s.ca/dialv2-ricketts-unwritten/

- Ruskin, John. The Works of John Ruskin, vol. 33, edited by E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. London: George Allen, 1908.

- Scott, Temple. “Mr. Charles Ricketts and the Vale Press (An Interview).” Charles Ricketts, Everything for Art: Selected Writings, edited by Nicholas Frankel, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire: Rivendale, 2014, pp. 333–3441.

- Symons, Arthur. “The Lesson of Millais.” The Savoy, vol. 6, 1896, pp. 57–58.

Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra,

Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital

Humanities, 2019.

https://1890s.ca/savoyv6-symons-millais/

MLA citation:

Dunn-McAfee, Nicholas. “Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2023, https://1890s.ca/rossetti_dg_bio/.