❧ THE PAGEANT

ART EDITOR LITERARY EDITOR

C. HAZELWOOD SHANNON J. W. GLEESON WHITE

PUBLISHED BY MESSRS. HENRY AND COMPANY

93 ST. MARTIN’S LANE LONDON

MDCCCXCVI

❧THE BOOK IS PRINTED BY MESSRS. T. AND A. CONSTABLE. THE

LITHOGRAPH IS PRINTED BY MR. THOMAS WAY. THE HALF-TONE

REPRODUCTIONS ARE BY THE SWAN ELECTRIC ENGRAVING COMPANY.

THE COPYRIGHT OF THE PLATES ON PAGES 137, 161, 173 IS THE

PROPERTY OF MR. F. HOLLYER; THAT ON PAGE 77 IS THE PROPERTY

OF MESSRS F. WARNED AND CO.

❧ THE TITLE-PAGE IS DESIGNED BY SELWYN IMAGE, AND THE

END-PAPERS BY LUCIEN PISSARRO.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Front

Cover . .

. by Charles Ricketts

Endpapers . .

. by Lucien

Pissarro

Half Title

Page . [v]

Title

Page . .

. by Selwyn

Image . [vii]

Publishers

Note . [ix]

❧ LITERARY CONTENTS

A ROUNDEL OF

RABELAIS . .

. A. C. Swinburne

. 1

COSTELLO THE PROUD, OONA MACDERMOTT, AND THE BITTER

TONGUE,

. .

. W. B.

Yeats . 2

MONNA ROSA . .

. Paul

Verlaine . 14

NIGGARD

TRUTH . .

. John

Gray . 20

ET S’IL REVENAIT

. .

. Maurice

Maeterlinck . 37

ON THE SHALLOWS . .

. W. Delaplaine

Scull . 38

SONG . .

. W. E.

Henley (1877) . 46

THE DEATH OF

TINTAGILES . .

. Maurice

Maeterlinck . 47

(Translated by Alfred

Sutro)

DAVID GWYNN—HERO OR ‘BOASTING LIAR’?

. .

. Theodore

Watts . 72

THE WORK OF CHARLES

RICKETTS . .

. J. W.

Gleeson White . 79

A

DUET . .

. T. Sturge

Moore . 94

TALE OF A NUN . .

. Translated by L. Simons and L.

Housman . 95

A HANDFUL OF

DUST . .

. Richard

Garnett . 117

WILHELM

MEINHOLD . .

. F. York

Powell . 119

FOUR

QUATRAINS . .

. Percy

Hemingway . 130

INCURABLE . .

. Lionel

Johnson . 131

BY THE

SEA . .

. Margaret L.

Woods . 140

GROUPED

STUDIES . .

. Frederick

Wedmore . 142

THE SOUTH

WIND . .

. Robert

Bridges . 145

ALFRIC . .

. W. Delaplaine

Scull . 151

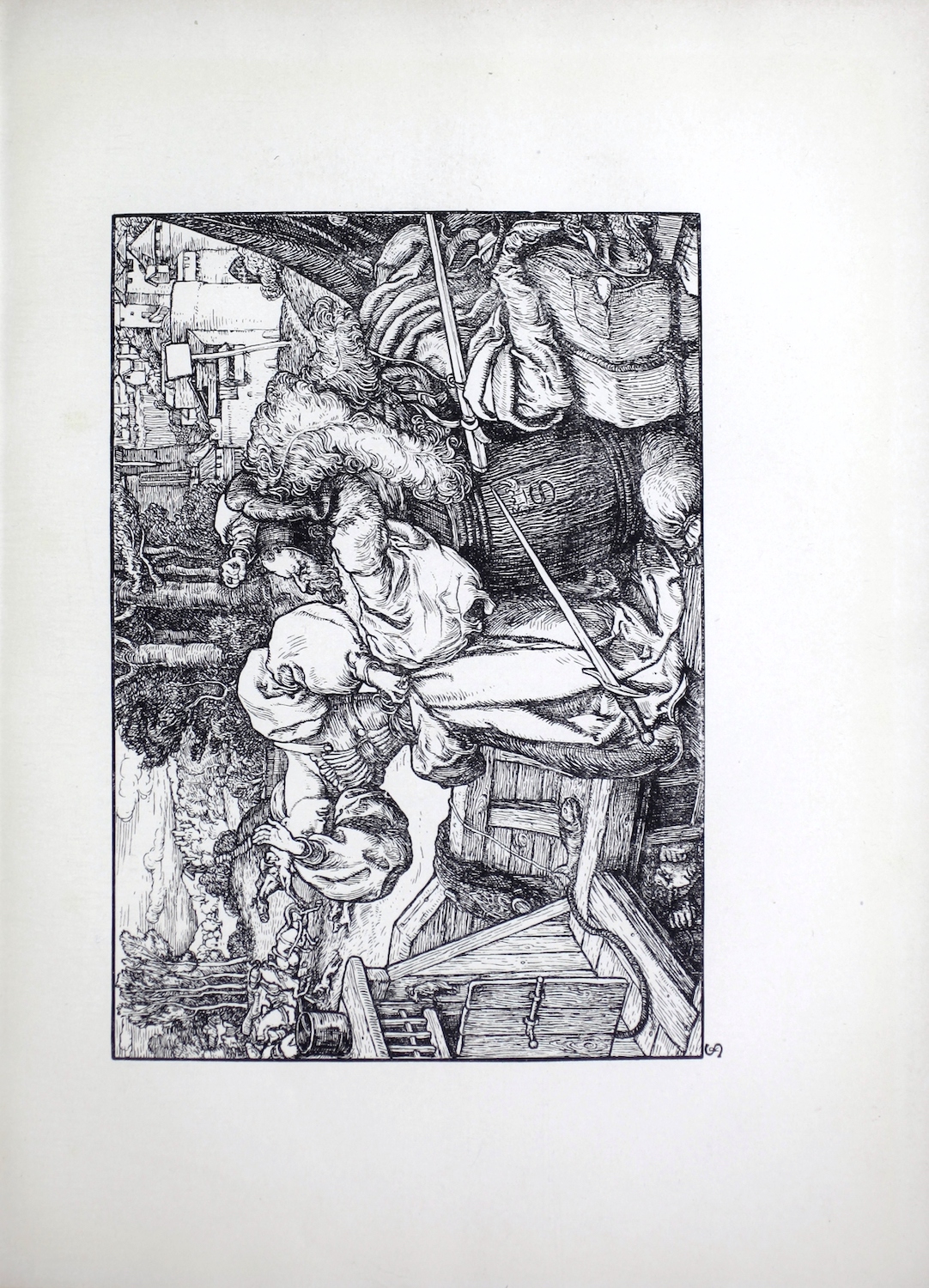

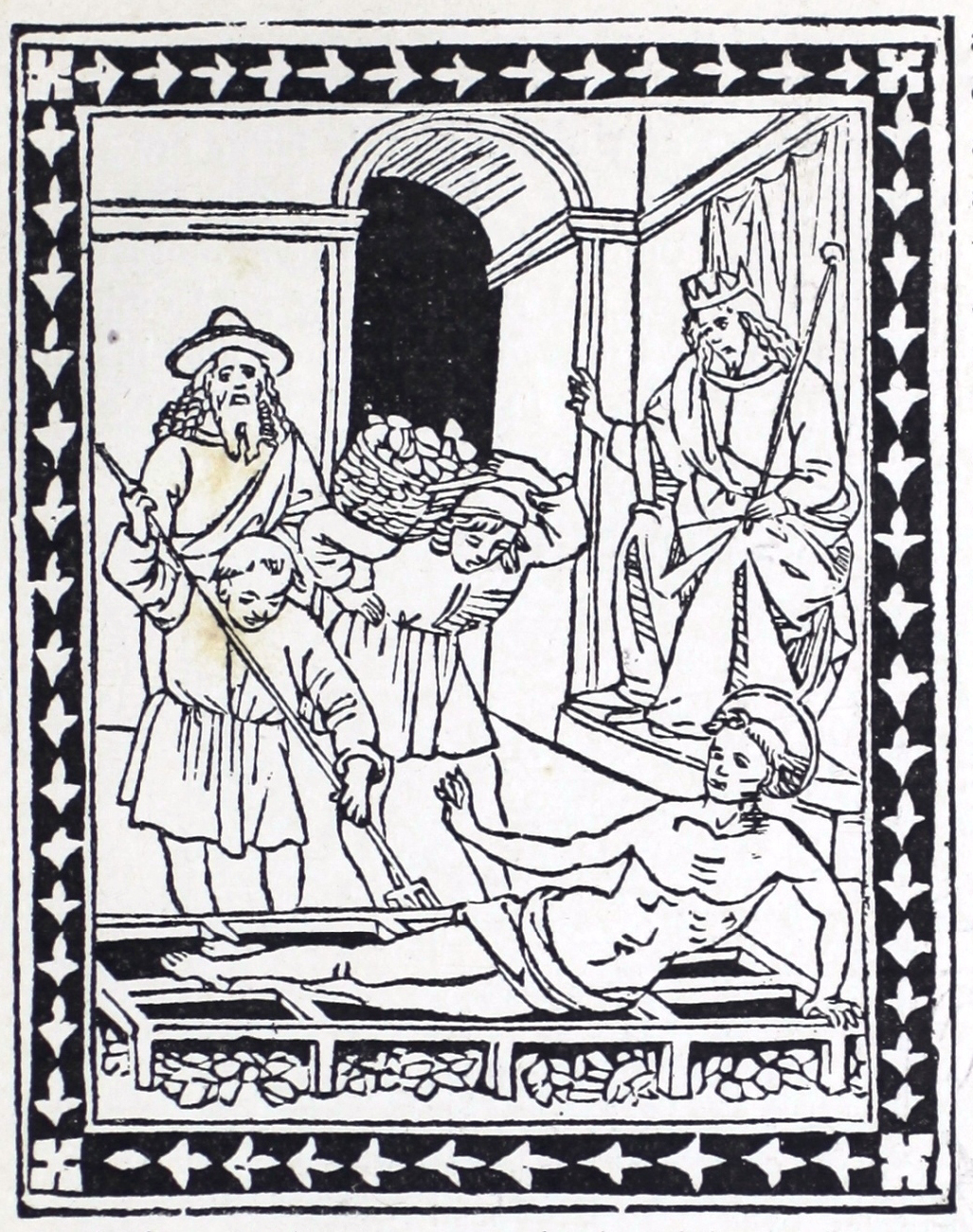

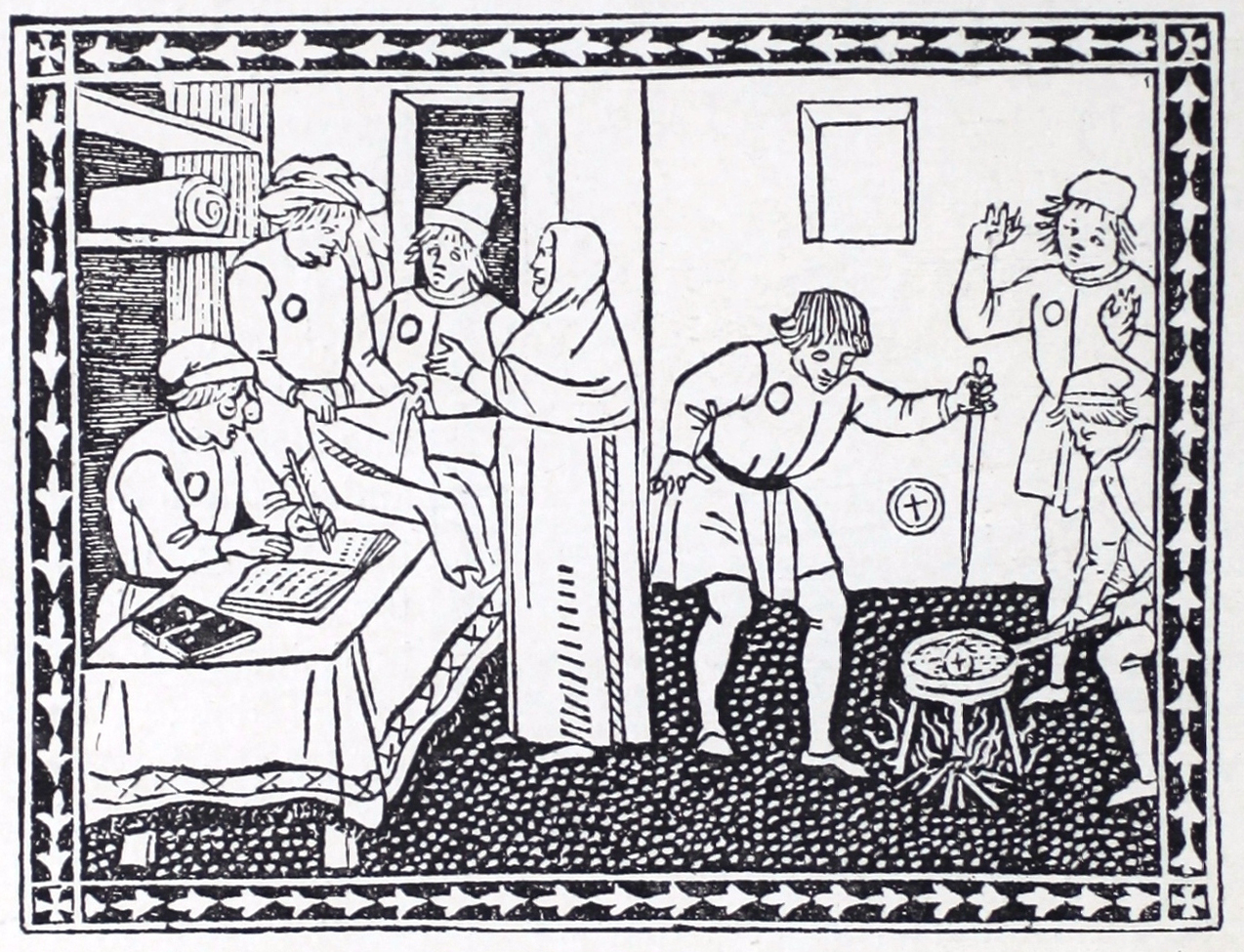

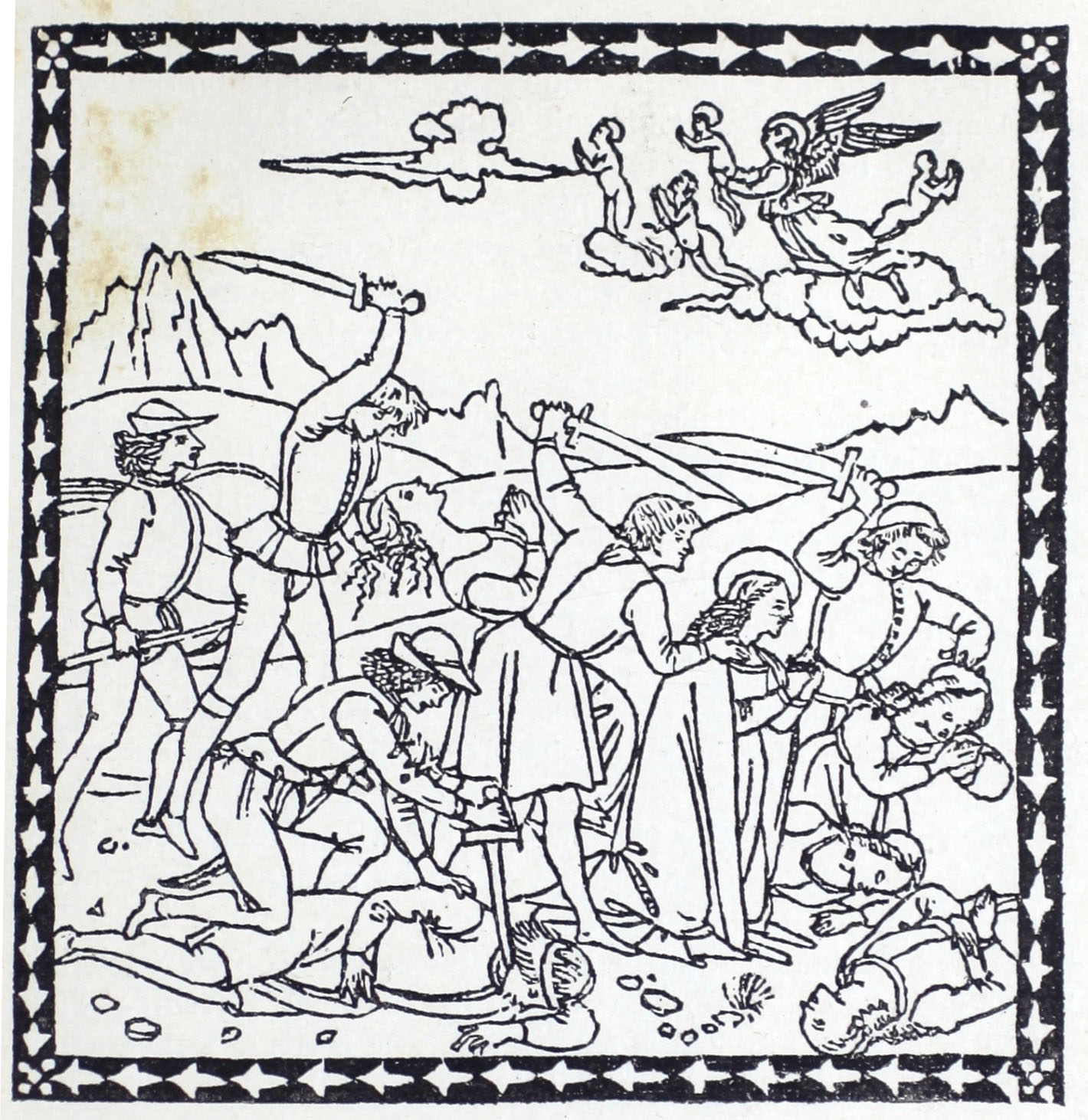

FLORENTINE RAPPRESENTAZIONI AND THEIR PICTURES,

. .

. Alfred W.

Pollard . 163

THE

OX . .

. John

Gray . 184

EQUAL

LOVE . .

. Michael

Field . 189

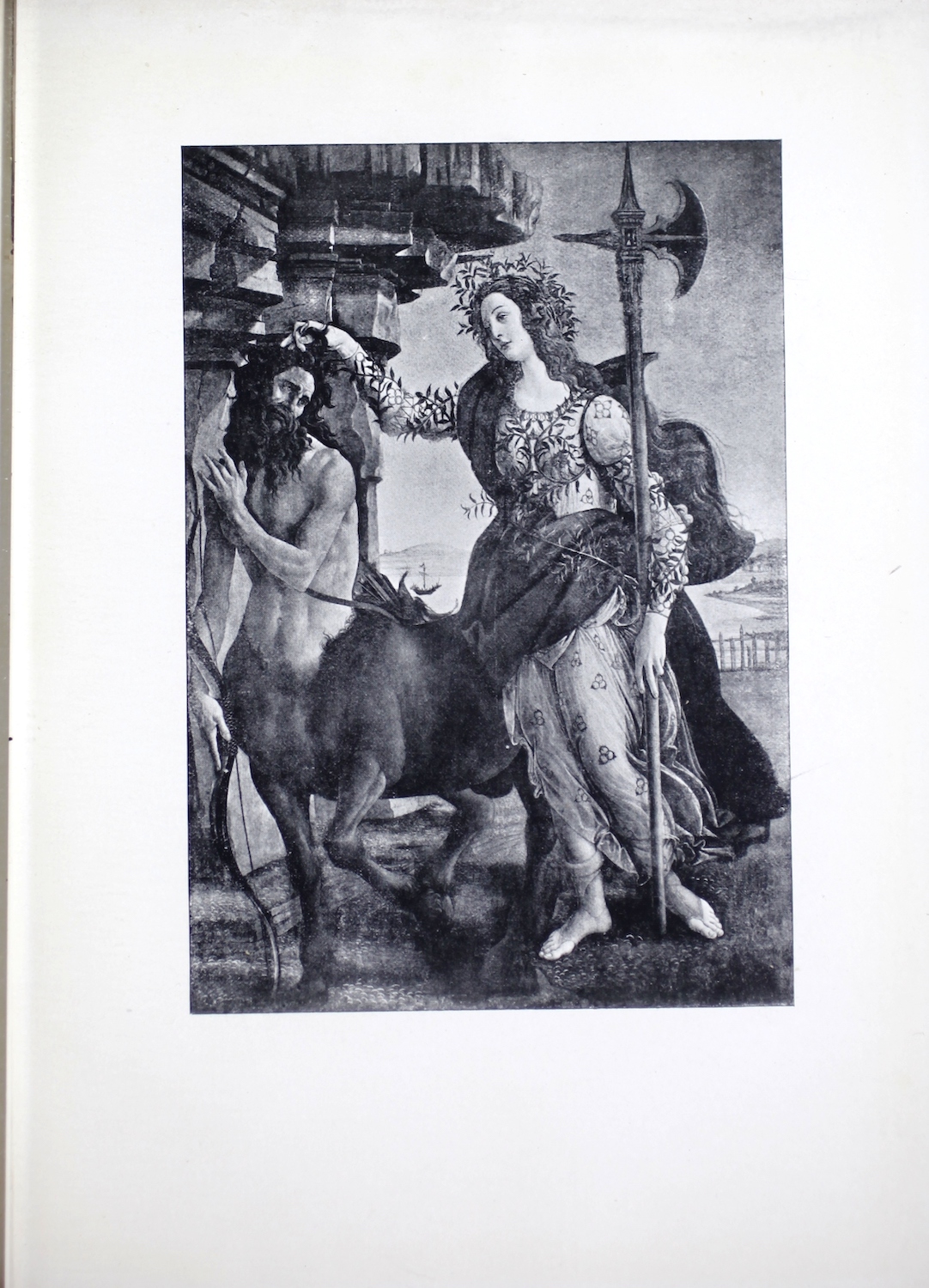

PALLAS AND THE CENTAUR,

after a picture by

Botticelli . .

. T. Sturge

Moore . 229

BE IT COSINESS . .

. Max

Beerbohm . 230

SOHEIL . .

. R. B. Cunninghame

Graham . 236

❧ ART CONTENTS

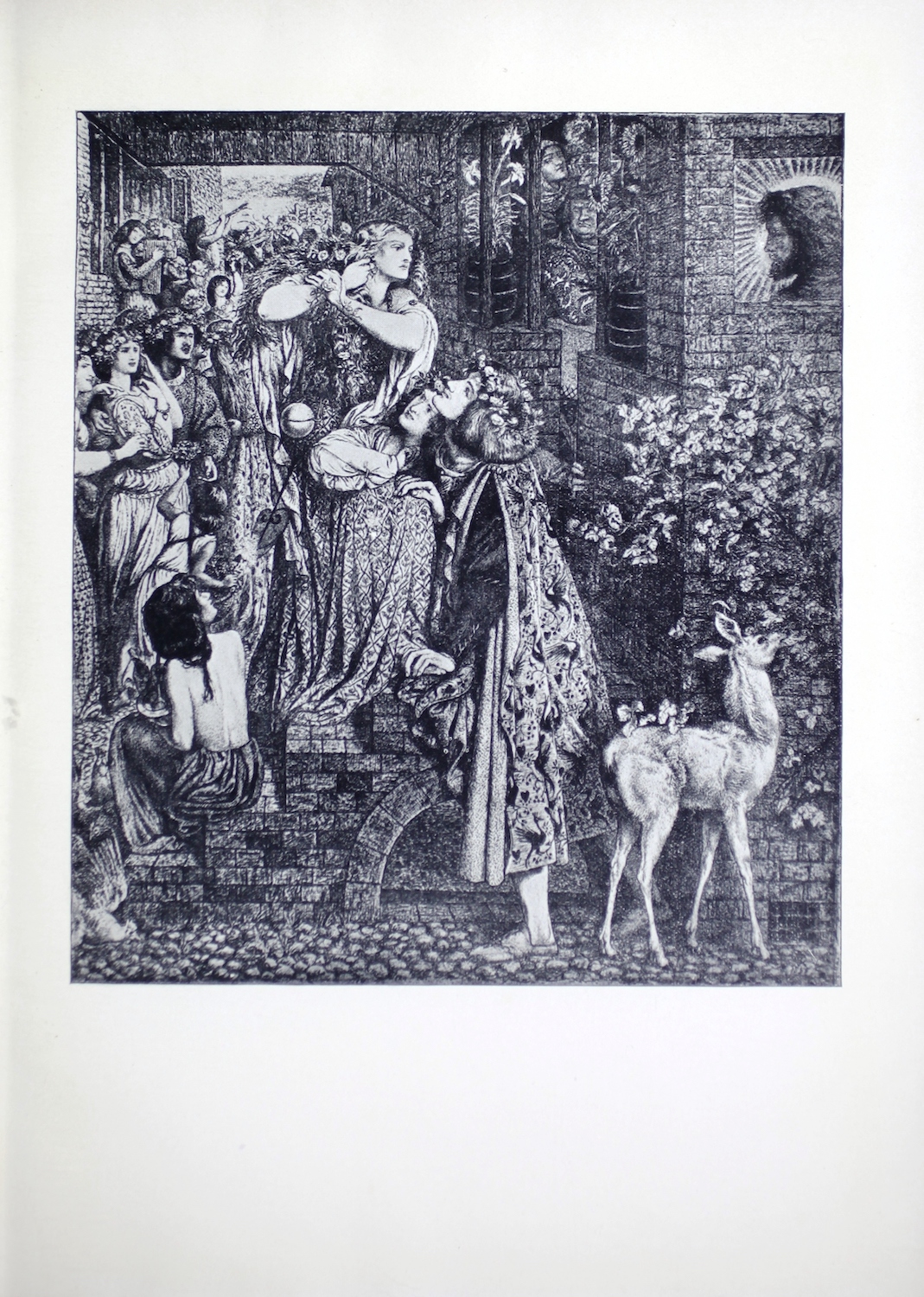

THE MAGDALENE AT THE HOUSE OF SIMON THE

PHARISEE,

Dante Gabriel Rossetti . Frontispiece

MONNA

ROSA . .

. Dante Gabriel

Rossetti . 17

THE DOCTOR—PORTRAIT OF MY BROTHER,

an original

lithograph . .

. James M’Neil

Whistler . 29

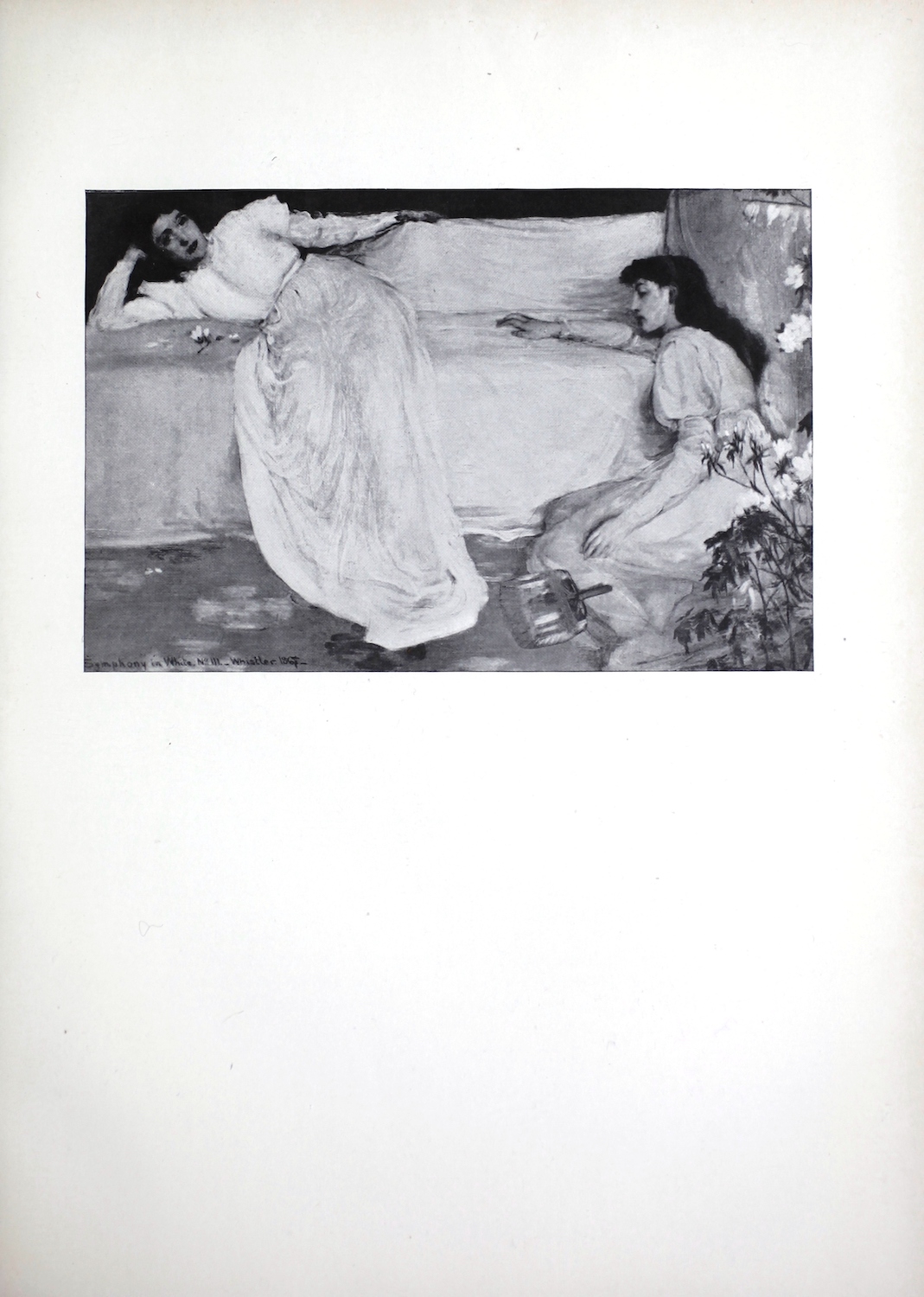

SYMPHONY IN WHITE, NO. III

. .

. James M’Neil

Whistler . 41

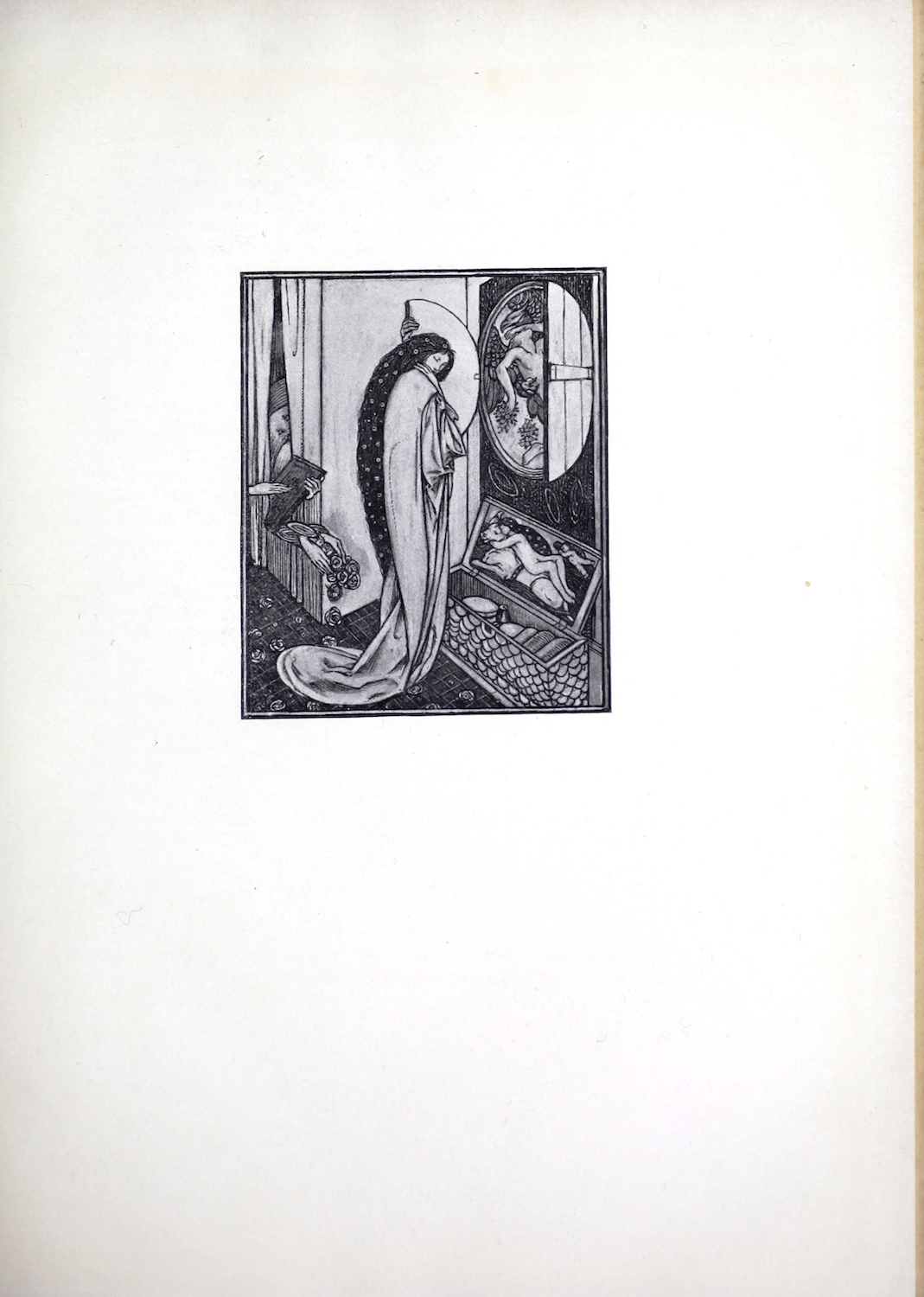

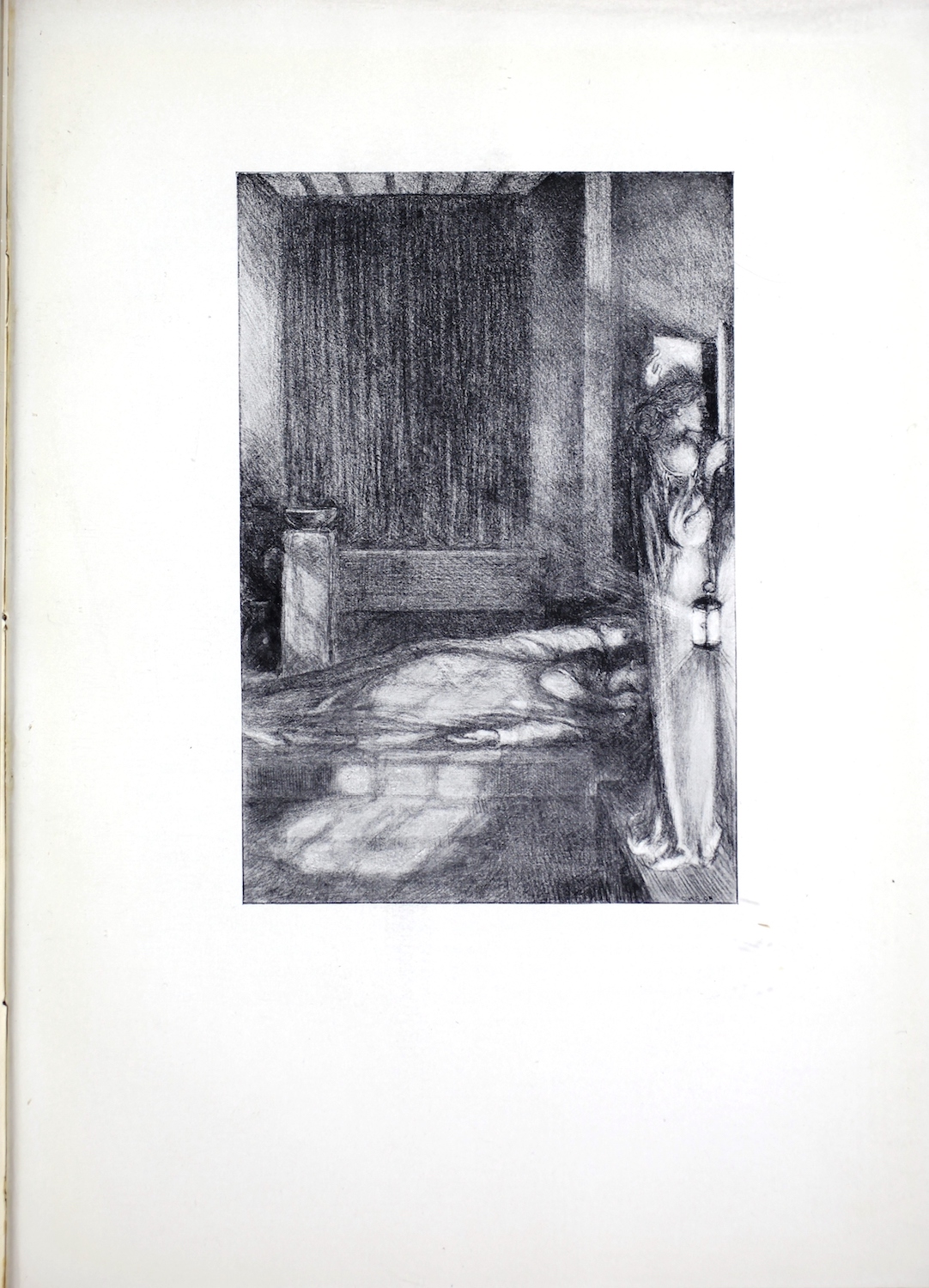

PSYCHE IN THE

HOUSE . .

. Charles

Ricketts . 53

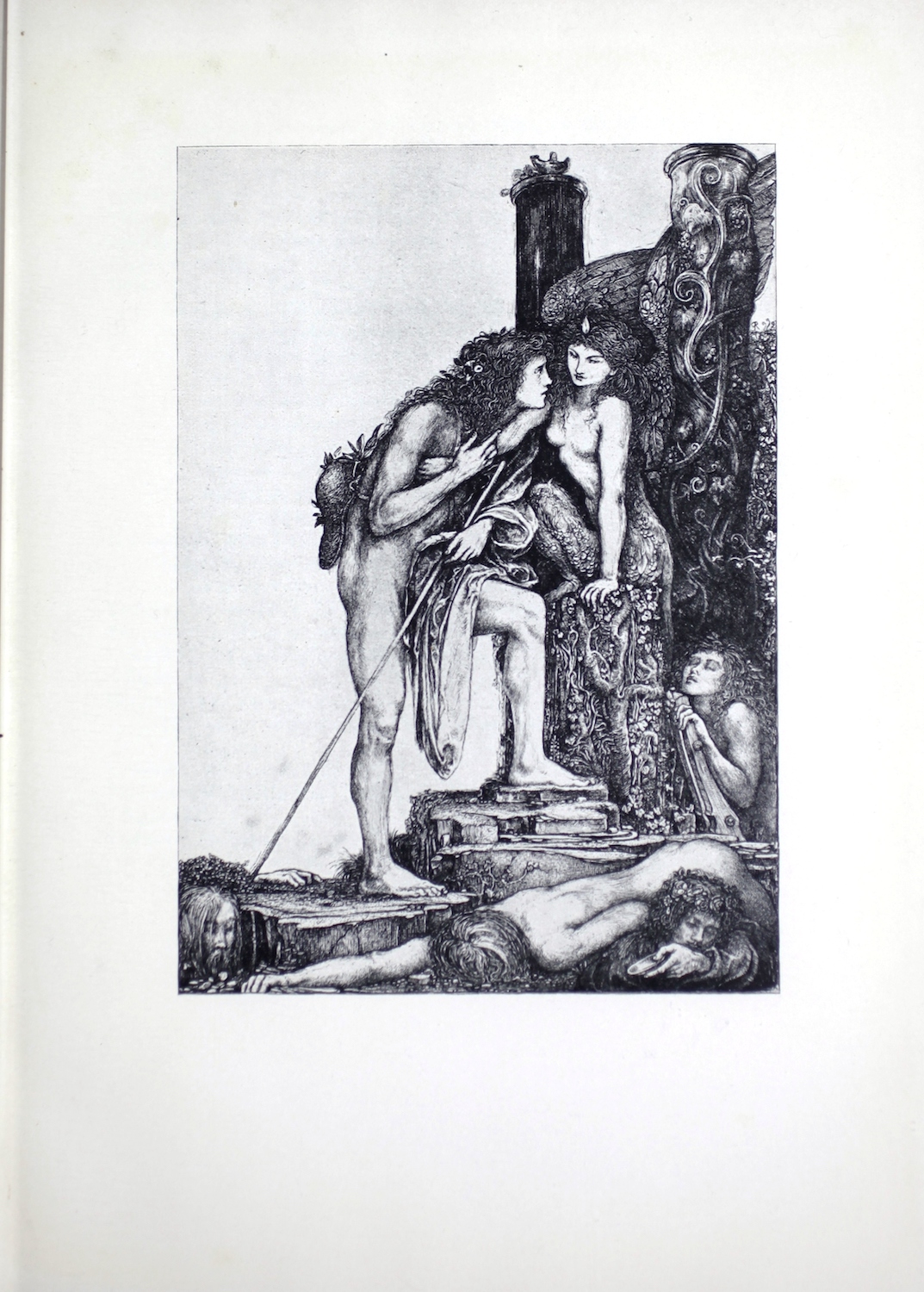

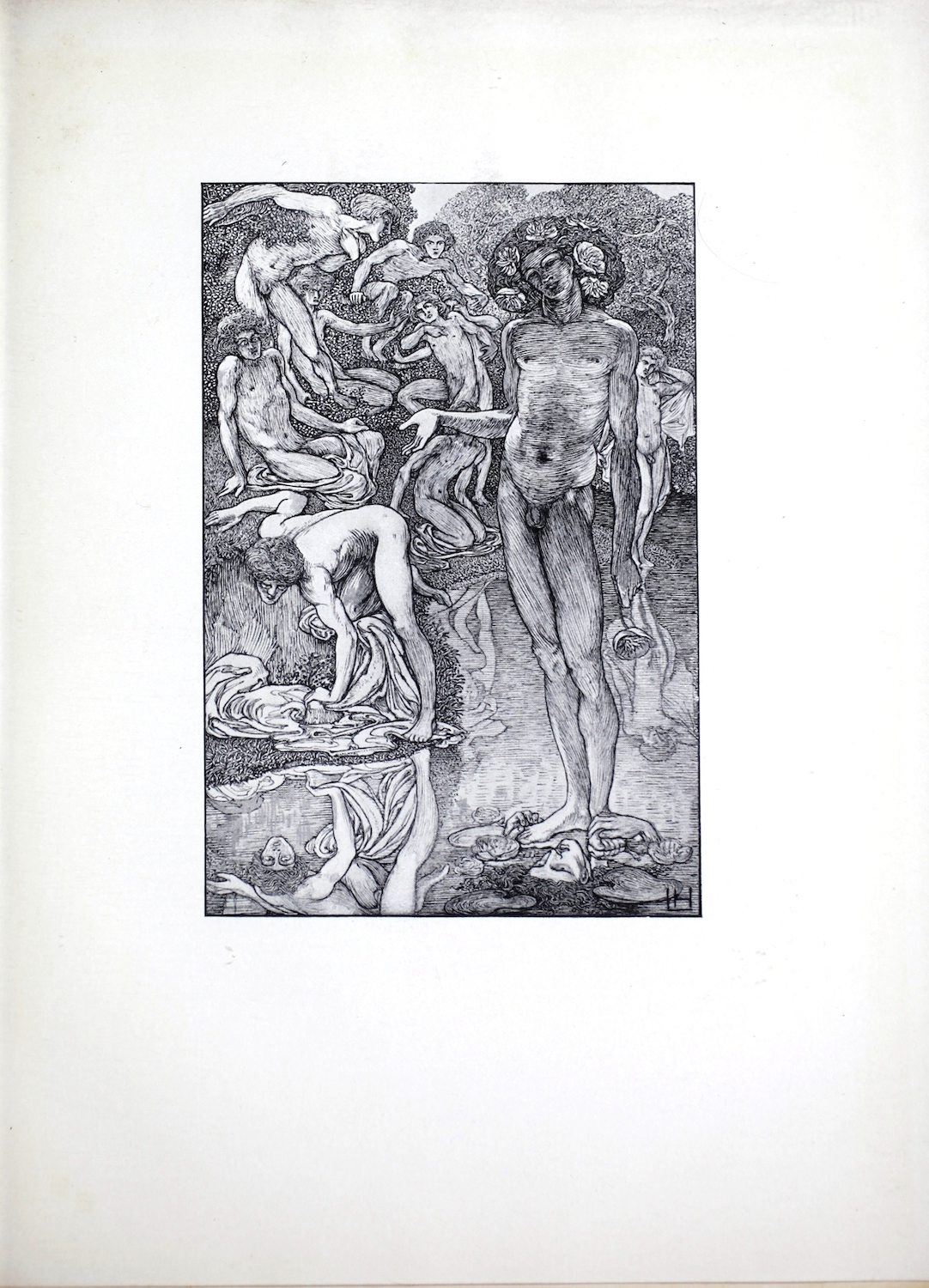

ŒDIPUS, after a pen

drawing . .

. Charles

Ricketts . 65

LOVE, a brush

drawing . .

. Sir John Everett Millais, R.A. . 77

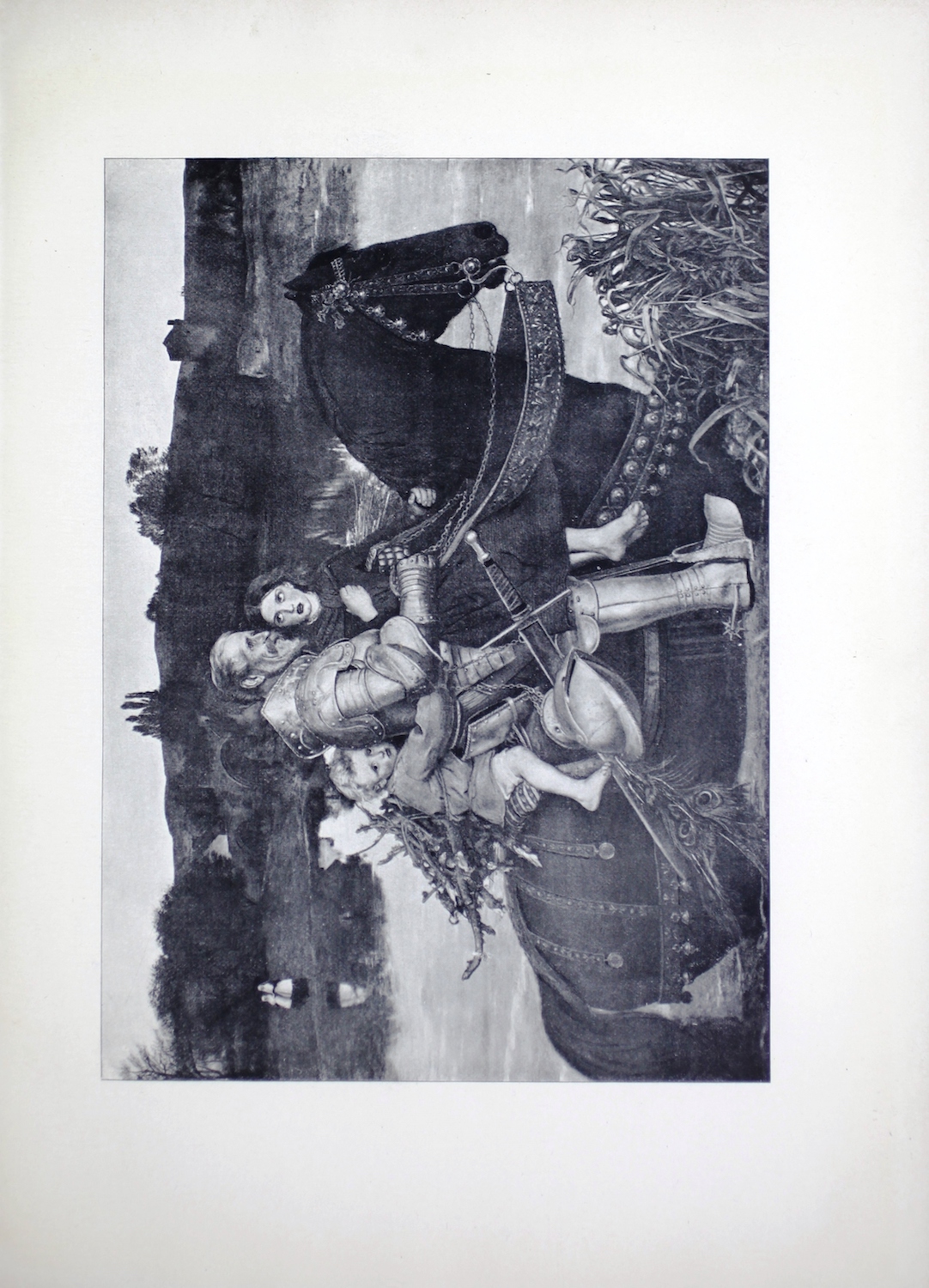

SIR ISUMBRAS AT THE

FORD . .

. Sir John

Everett Millais, R.A. . 89

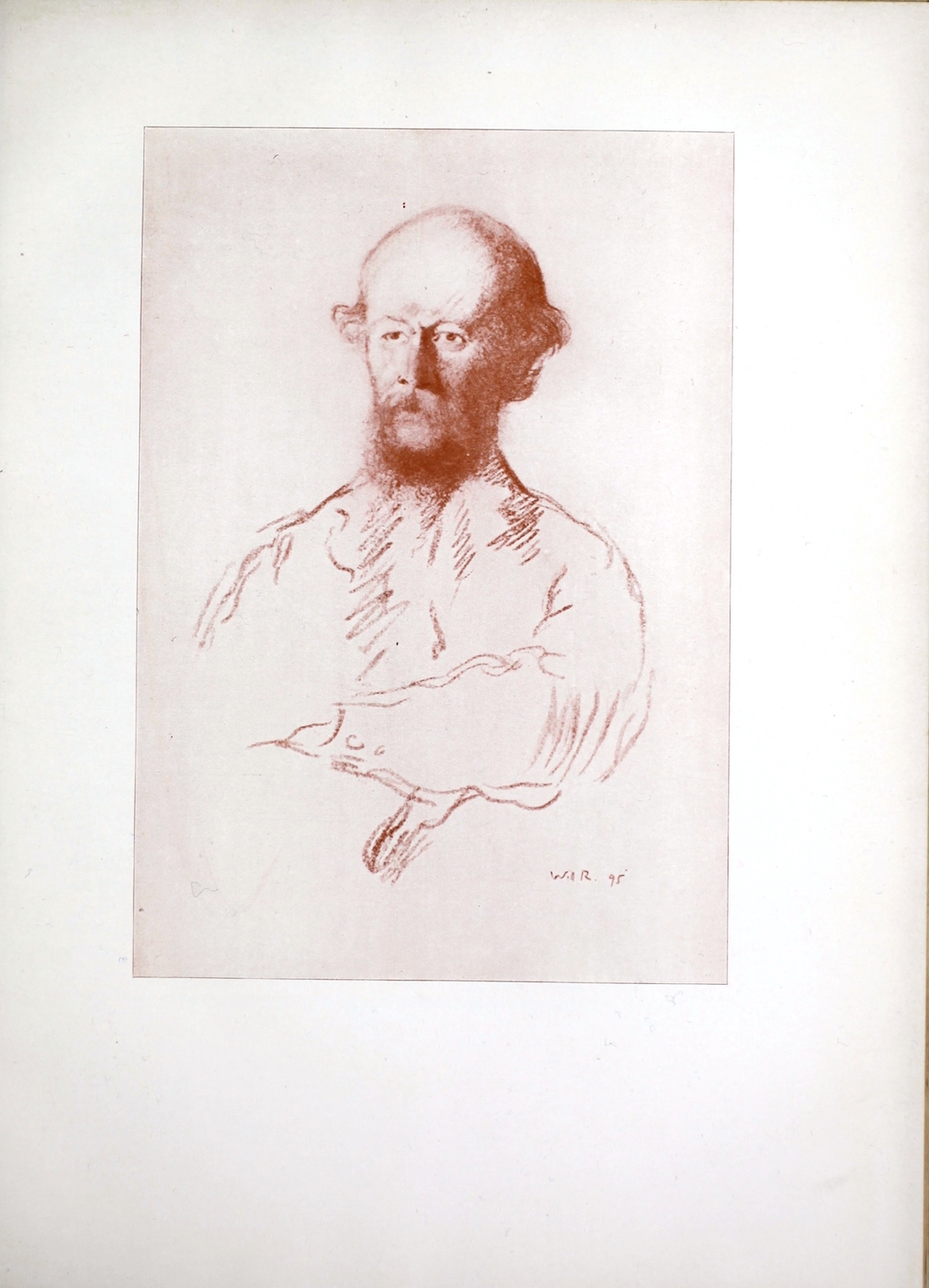

ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE,

a chalk drawing

. .

. Will

Rothenstein . 101

L’OISEAU BLEU, after a water-colour drawing . .

. Charles

Conder . 113

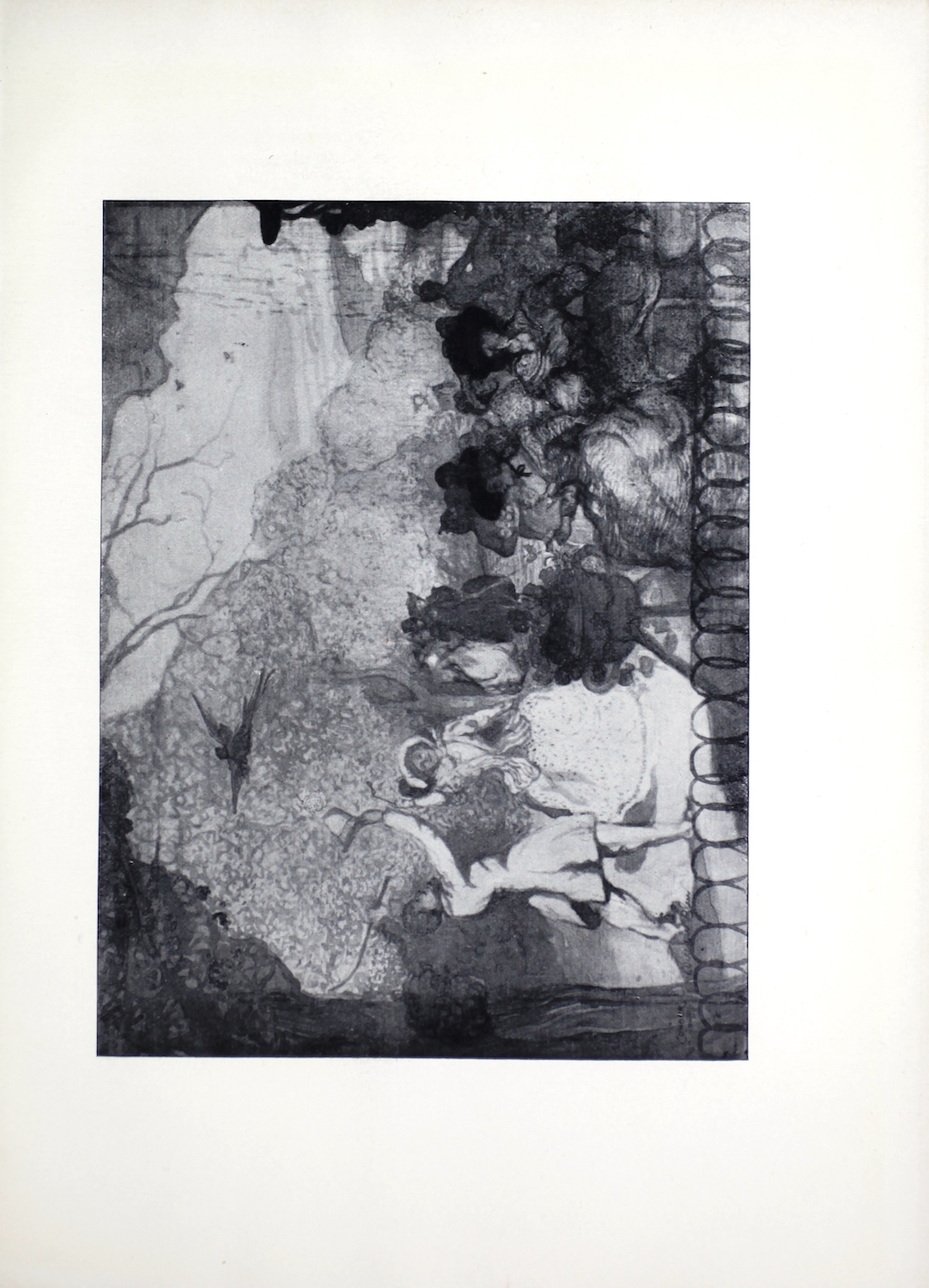

SIDONIA AND OTTO VON BORK ON THE WATERWAY TO STETTIN,

a pen

drawing . .

. Reginald

Savage . 125

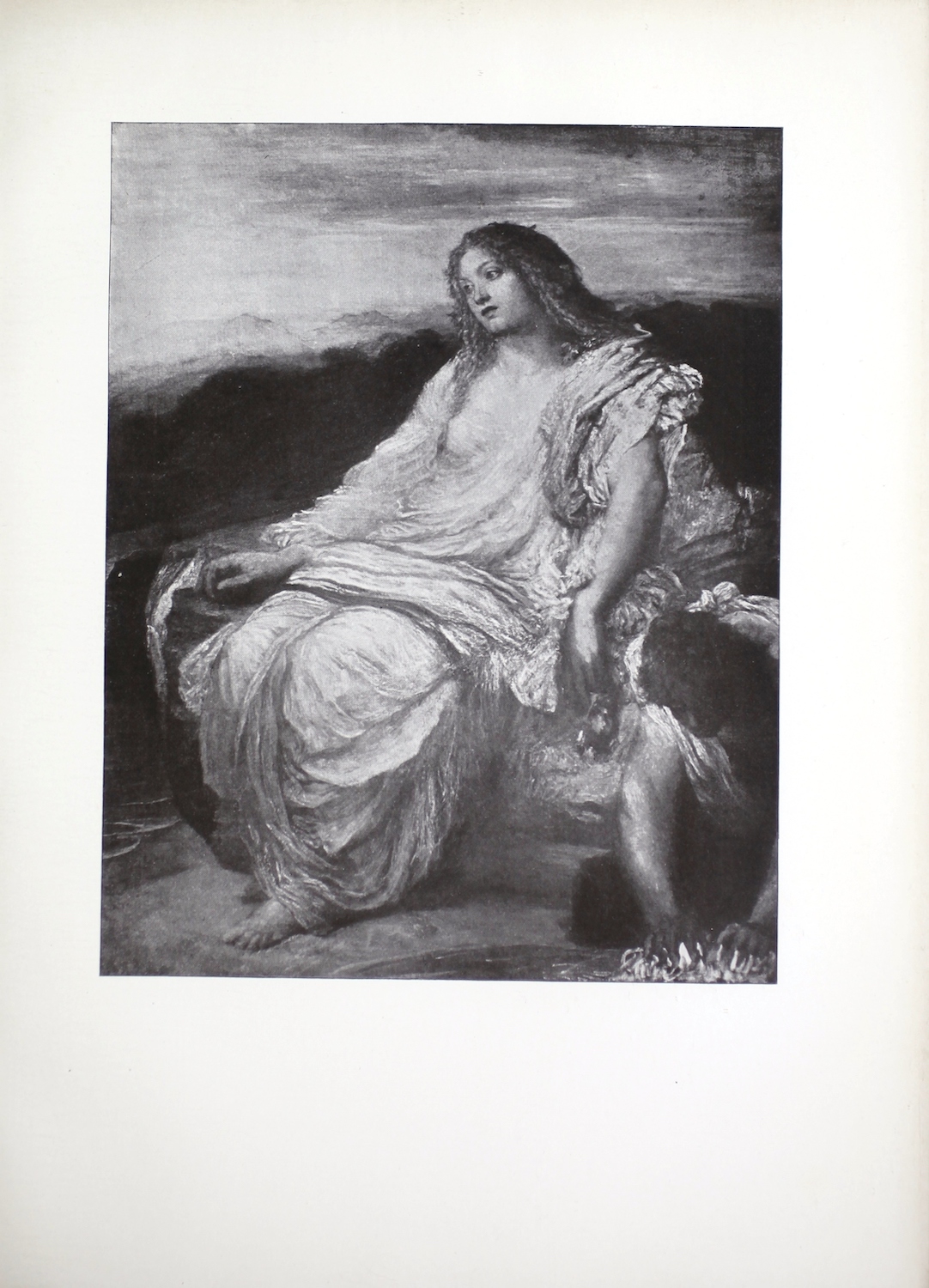

ARIADNE . .

. G. F. Watts,

R.A. . 137

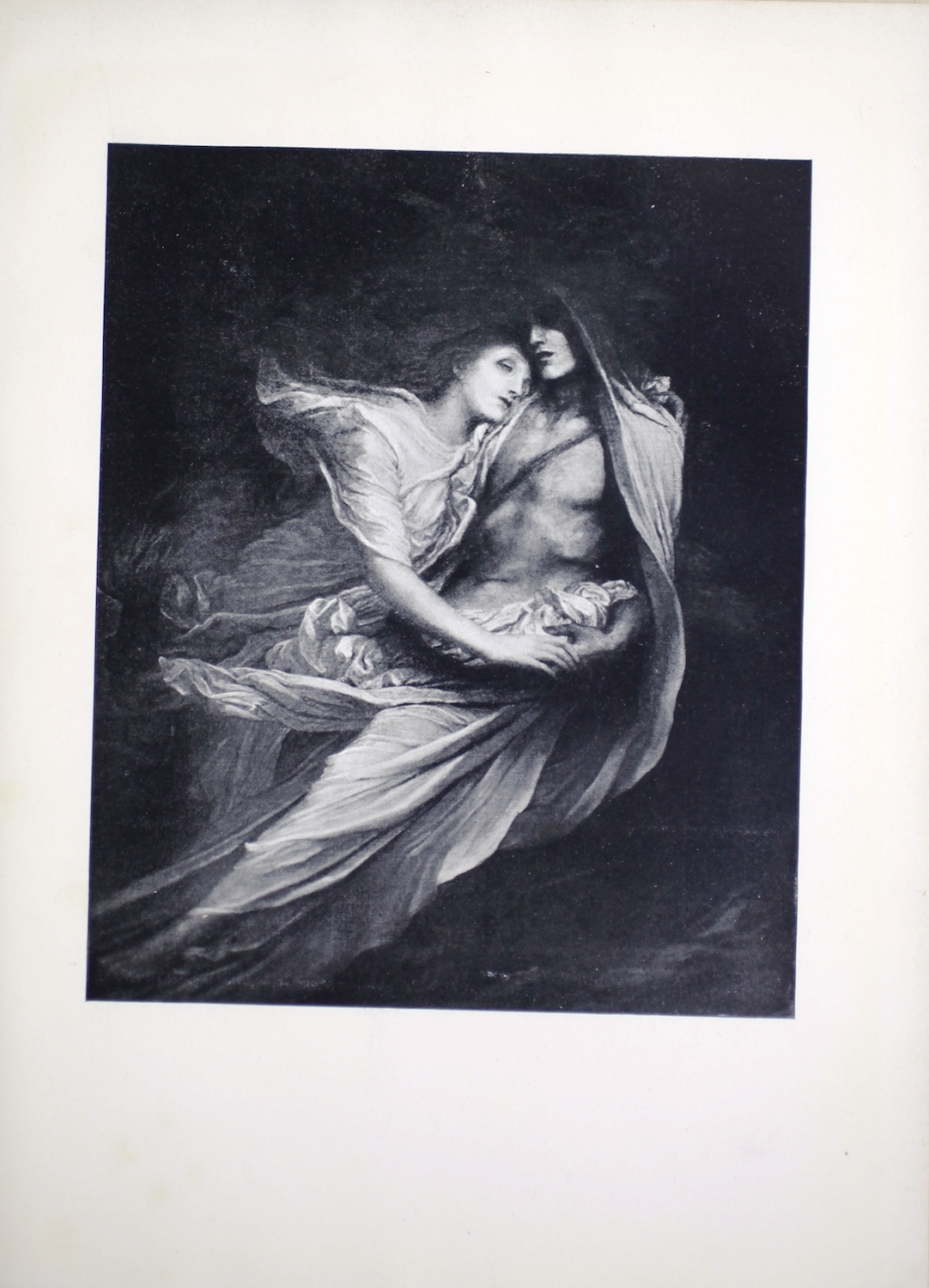

PAOLO AND

FRANCESCA . .

. G. F.

Watts, R. A. . 149

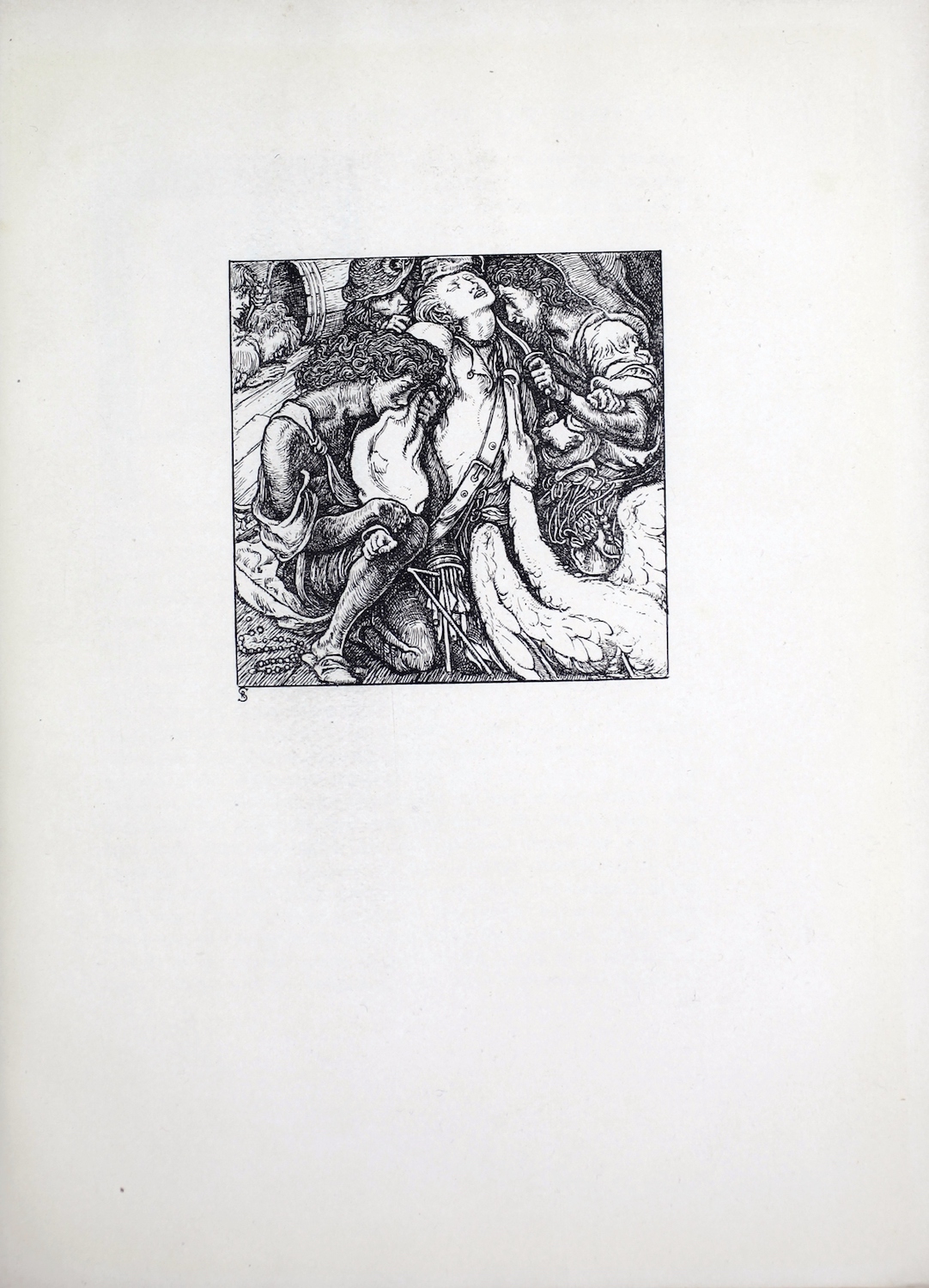

THE ALBATROSS (ANCIENT MARINER),

a pen

drawing . .

. Reginald

Savage . 161

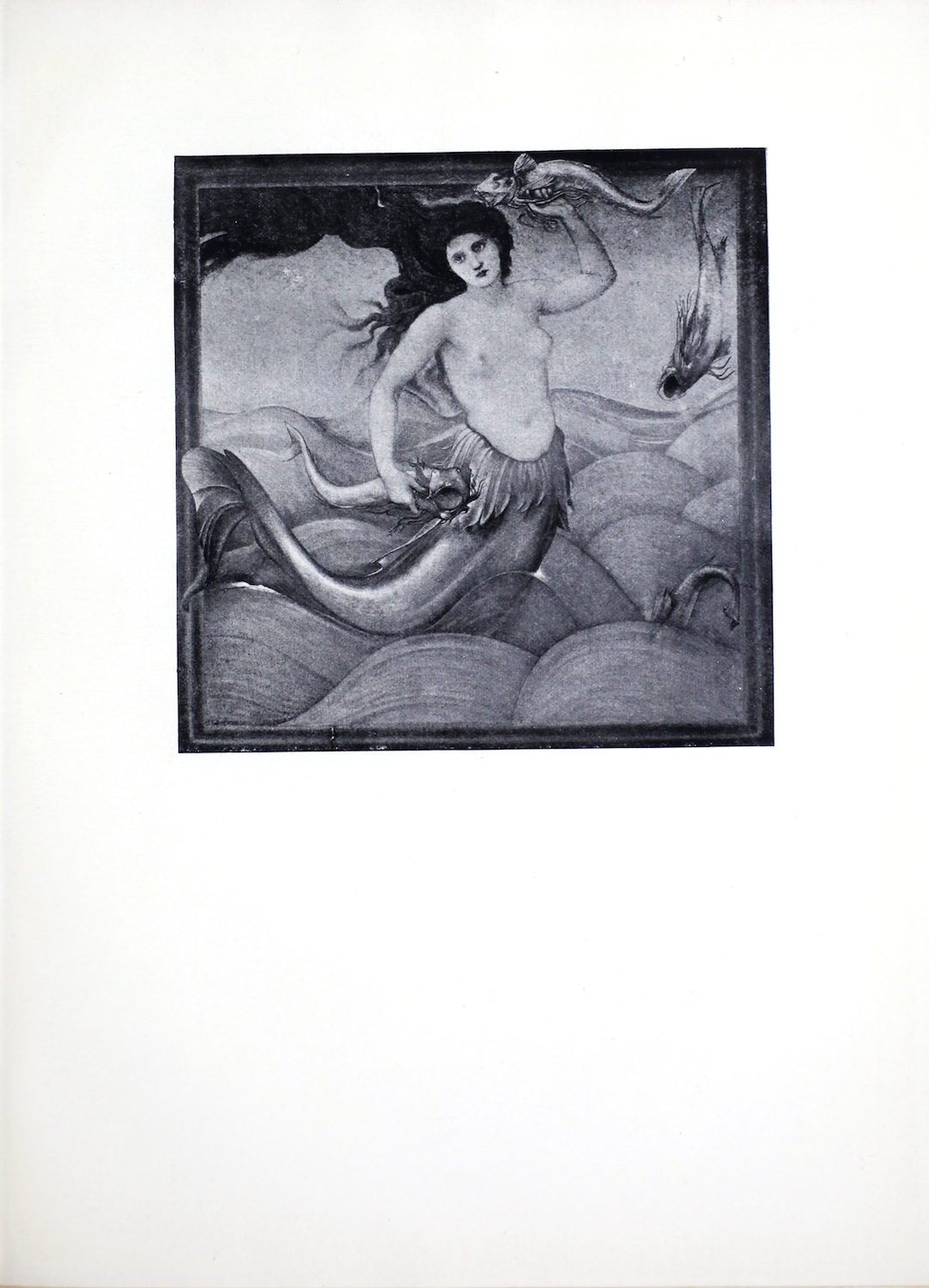

THE SEA

NYMPH . .

. Sir

Edward Burne Jones . 173

PERSEUS AND

MEDUSA . .

. Sir Edward Burne

Jones . 187

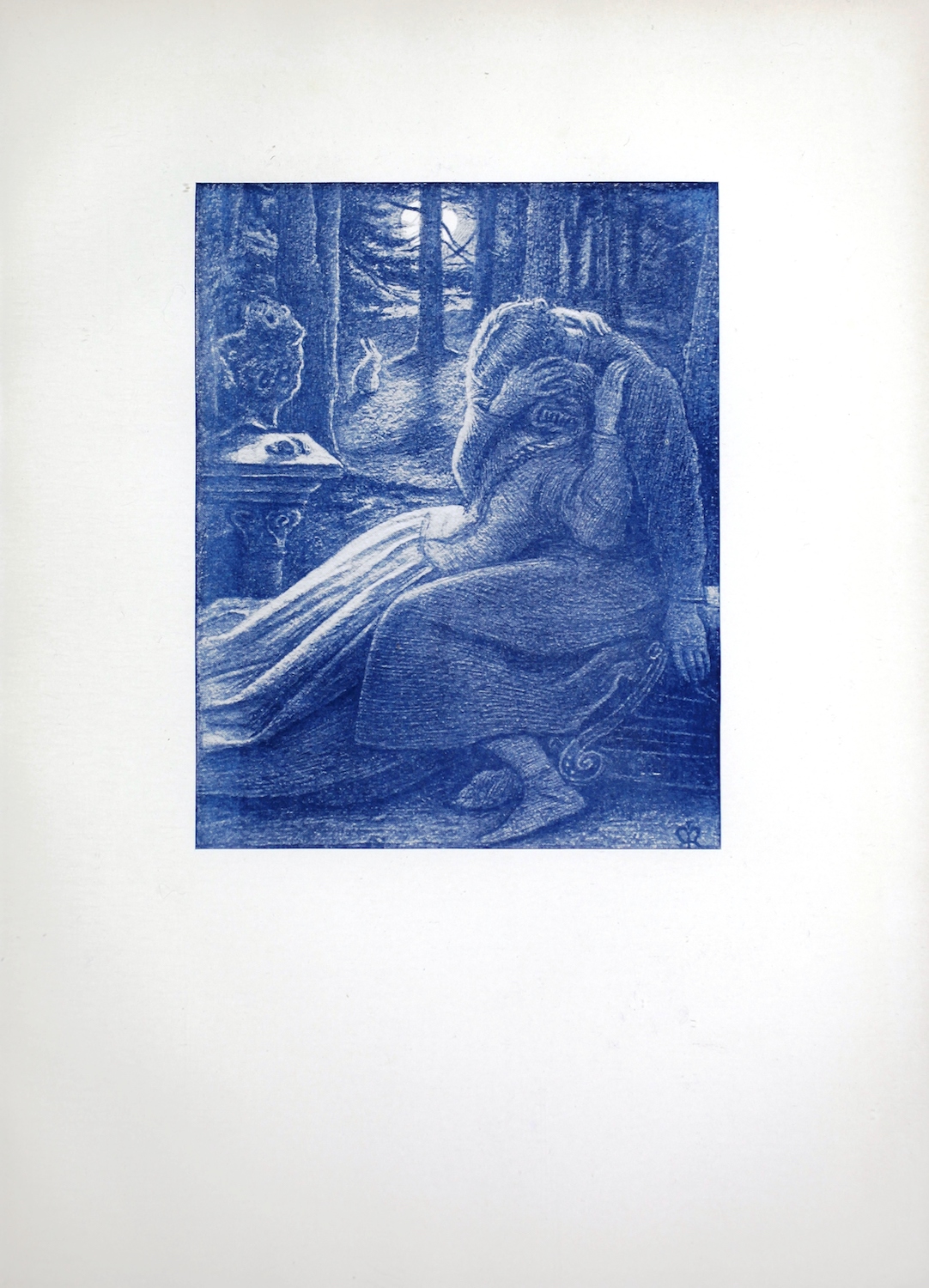

DEATH AND THE BATHER,

after a pen

drawing . .

. Laurence Housman . 199

A ROMANTIC LANDSCAPE,

after a water-colour

drawing . .

. Charles H. Shannon . 211

PALLAS AND THE

CENTAUR . .

. Sandro

Botticelli . 227

THE WHITE

WATCH . .

. Charles H.

Shannon . 239

Advertisements:

A Selection from Messrs Henry & Co’s

Publications . [i-viii]

Ad for: Swan

Electric Engraving Company . [ix]

❧ A ROUNDEL OF RABELAIS

THELEME is afar on the waters, adrift and afar,

Afar and afloat on the waters that flicker and gleam,

And we feel but her fragrance and see but the shadows that mar

Theleme.

In the sun-coloured mists of the sunrise and sunset that steam

As incense from urns of the twilight, her portals ajar

Let pass as a shadow the light or the sound of a dream.

But the laughter that rings from her cloisters that know not a bar

So kindles delight in desire that the souls in us deem

He erred not, the seer who discerned on the seas as a star

Theleme.

❧It is particularly requested that this poem should not be quoted as

a whole in any publication.

COSTELLO THE PROUD, OONA MACDERMOTT, AND THE BITTER TONGUE

COSTELLO had come up from the fields, and

lay

upon the ground before the door of his

square tower, supporting his head

upon his

hands, looking at the sunset, and considering

the chances of

the weather. Though the

customs of Elizabeth and James, now going

out

of fashion in England, had begun to pre-

vail among the gentry, he still

wore the

great cloak of the native Irishry; and the

sensitive outlines

of his face and the greatness of his indolent body

showed a commingling of

pride and strength which belonged to a

simpler age. His eyes strayed in a

little from the sunset to where the

long white road lost itself over the

south-western horizon, and then

falling, lit upon a horseman who toiled

slowly up the hill. A few more

minutes and the horseman was near enough for

his little and shapeless

body, his long Irish cloak and the dilapidated

bagpipes hanging from

his shoulders, and the rough-haired garron under him,

to stand out dis-

tinctly in the gathering greyness. So soon as he had come

within

earshot he began crying in Gaelic,

‘Is it sleeping you are, Tumaus Costello, while better folk

break

their hearts on the great white roads? Listen to me,

Tumaus Costello

the Proud, for I come out of Coolavin, and bring a message

from Oona

MacDermott, and it is the good pay I must have, for the saddle

was

bitter under me.’

He was close to the door by now, and began slowly

dismounting,

cursing the while by God, and Bridget and the

devil; for riding in all

weathers from wake to wedding and wedding to wake

had made him

rheumatic. Costello had risen to his feet, and was fumbling at

the

mouth of the leather bag, in which he carried his money, but it

was

some time before it would open, for the hand that had thrown so

many

in wrestling shook with excitement.

‘Here is all the money in my bag,’ he said, at last dropping

a stream

of French and Spanish silver into the hand of the

piper. ‘I got it

for a heifer down at Ballysumaghan last week!’ The other

bit a

shilling between his teeth, and went on,

‘And it is the good protection I must have, for if the

MacDermotts

lay their hands upon me in any boreen after sundown,

or in Coolavin

by

3

by broad day, I will be flung among the

nettles in a ditch, or hanged

upon the sycamore, where they hanged the

horse thieves out by Leitram

last Great Beltan four years!’ And while he

spoke he tied the reins

of his garron to a bar of rusty iron that was

mortared into the wall.

‘I will make you my piper and my body servant’ said Costello,

‘and

no man dare lay hands upon the man or the goat, or the

horse or the

dog protected by Tumaus Costello.’

‘And I will only tell my message’ said the other flinging the

saddle

on the ground, ‘in the corner of the chimney with a

noggin of Spanish

ale in my hand, and a jug of Spanish ale beside me, for

though I am

ragged and empty my forbears were well clothed and full until

their

house was burnt, and their cattle harried in the time of Cathal of

the

Red Hand by the Dillons, whom I shall yet see on the hob of hell,

and

they screeching,’ and while he spoke the little eyes gleamed and

the

thin hands clenched.

Costello brought him into the great rush-strewn hall where

were none

of the comforts which had begun to grow common among

the gentry,

but a feudal gauntness and bareness, and led him to the bench

in the

great chimney; and when he had sat down, filled up a horn noggin,

and

set it on the bench beside him, and set a great black-jack of

leather

beside the noggin, and lit a torch that slanted out from a ring in

the wall,

his hands trembling the while; and then turned towards him and

said,

‘Will Oona MacDermott come to me, Dualloch O’Daly of the Pipes?’

‘Oona MacDermott will not come to you, for her father, Teig

Mac-

Dermott of the Sheep, has set women to watch her, but she

bid me tell

you that this day sennight will be the eve of St. John and the

night of

her betrothal to Macnamara of the Lake, and she would have you

there,

that, when they bid her drink to him she loves best, as the way is,

she

may drink to you, oh Tumaus Costello, and let all know where her

heart

is and how little of gladness is in her marrying: and I myself bid

you

go with good men about you, for I saw the horse thieves with my

own

eyes, and they dancing the blue pigeon in the air.’ And then he

held

the now empty noggin towards Costello, his hand closing round it

like

the claw of a bird, and cried,

‘Fill my noggin again, for I would the day had come when all

the

water in the world is to shrink into a periwinkle shell,

that I might

drink nothing but the poteen.’ Finding that Costello made no

reply,

but sat in a dream, he burst out,

‘Fill my noggin, I tell you, for no Costello is so great in

the world

that

4

that he should not wait upon an O’Daly,

even though the O’Daly travel

the road with his pipes and the Costello have

a bare hill, an empty

house, a horse, a herd of goats and a handful of

cows.’

‘Praise the O’Dalys if you will’ said Costello as he filled

the noggin,

‘for you have brought me a kind word from my love.’

For the next few days Duallach went hither and thither,

trying to

raise a body guard; and every man he met had some

story of Costello,

how he killed the wrestler, when but a boy, by so

straining at the belt,

that went about them both, that he broke the back of

his opponent;

how, when somewhat older, he dragged the fierce horses of the

Dunns of

Shancough through a ford in the Unchion for a wager; how, when

he

came to maturity, he broke the steel horse shoe in Mayo; how he

drove

many men before him through Drumlease and Cloonbougher and

Druma-

hair, because of a malevolent song they had about his poverty;

and

of many another deed of his strength and pride; but he could find

none who would trust themselves with any so passionate and poor in

a

quarrel with careful and wealthy persons, like MacDermott of the

Sheep, and

Macnamara of the Lake.

Then Costello went out himself, and, after listening to

many

excuses and in many places, brought in a big half-witted

fellow who

followed him like a dog, a farm labourer who worshipped him for

his

strength, a fat farmer whose forefathers had served his family, and

a

couple of lads who looked after his goats and cows, and marshalled

them before the fire in the empty hall. They had brought with them

their

stout alpeens, and Costello gave them an old pistol a-piece, and

kept them

all night drinking Spanish ale, and shooting at a white

turnip which he

pinned against the wall with a skewer. O’Daly sat on

the bench in the

chimney playing ‘The Green Bunch of Rushes,’ ‘The

Unchion Stream,’ and ‘The

Princes of Beffeny’ on his old pipes, and

railing now at the appearance of

the shooters, now at their clumsy shoot-

ing, and now at Costello because

he had no better servants. The

labourer, the half-witted fellow, the farmer

and the lads were all well

accustomed to O’Daly’s unquenchable railing, for

it was as inseparable

from wake or wedding as the squealing of his pipes,

but they wondered

at the forbearance of Costello, who seldom came either to

wake or

wedding, and, if he had, would scarce have been patient with a

scolding

piper.

On the next evening they set out for Coolavin, Costello

riding a

tolerable horse and carrying a sword, the others upon

rough haired

garrons

5

garrons, and with their stout alpeens

under their arms. As they rode

over the bogs, and in the boreens among the

hills, they could see fire

answering fire from hill to hill, from horizon

to horizon, and everywhere

groups who danced in the ruddy light of the

turf, celebrating the bridal

of life and fire. When they came to

MacDermott’s house they saw

before the door an unusually large group of the

very poor, dancing

about a fire, in the midst of which was a blazing

cartwheel, that cir-

cular dance which is so ancient that the gods, long

dwindled to be

but fairies, dance no other in their secret places. From the

door, and

through the long loop-holes on either side, came the pale light

of

candles, and the sound of many feet dancing a dance of Elizabeth

and

James.

They tied their horses to bushes, for the number so tied

already

showed that the stables were full, and shoved their way

through a

crowd of peasants who stood about the door, and went into the

great

hall where the dance was. The labourer, the half-witted fellow,

the

farmer, and the two lads mixed with a group of servants, who were

looking on from an alcove, and Duallach sat with the pipers on their

bench;

but Costello made his way through the dancers to where

MacDermott of the

Sheep stood with Macnamara of the Lake, pouring

poteen out of a porcelain

jug into horn noggins with silver rims.

‘Tumaus Costello,’ said the old man, ‘you have done a good

deed

to forget what has been, and to fling away enmity and come

to the

betrothal of my daughter to Macnamara of the Lake.’

‘I come,’ answered Costello, ‘because, when in the time of

Eoha

of the Heavy Sighs my forbears overcame your forbears, and

afterwards

made peace, a compact was made that a Costello might go with

his

body servants and his piper to every feast given by a MacDermott

for

ever, and a MacDermott with his body servants and his piper to

every

feast given by a Costello for ever.’

‘If you come with evil thoughts and armed men,’ said

MacDermott

flushing, ‘no matter how strong your hands to wrestle

and to swing the

sword, it shall go badly with you, for some of my wife’s

clan have come

out of Mayo, and my three brothers and their servants have

come down

from the Mountains of the Ox,’ and while he spoke he kept his

hand

inside his coat as though upon the handle of a weapon.

‘No,’ answered Costello, ‘I but come to dance a farewell

dance with

your daughter.’

MacDermott drew his hand out of his coat and went over to a

tall

pale

6

pale girl who had been standing a little

way off for the last few

moments, with her mild eyes fixed upon the ground.

‘Costello has come to dance a farewell dance, for he knows

that you

will never see one another again.’

The girl lifted her eyes and gazed at Costello, and in her

gaze was

that trust of the humble in the proud, the gentle in

the violent, which

has been the tragedy of woman from the beginning.

Costello led her

among the dancers, and they were soon absorbed in the

rhythm of the

Pavane, that stately dance which, with the Saraband, the

Gallead, and

the Morrice dances, had driven out, among all but the most

Irish of the

gentry, the quicker rhythms of the verse-interwoven,

pantomimic dances

of earlier days ; and while they danced came over them

the unutterable

melancholy, the weariness with the world, the poignant and

bitter pity,

the vague anger against common hopes and fears, which is the

exulta-

tion of love. And when a dance ended and the pipers laid down

their

pipes and lifted their horn noggins, they stood a little from the

others,

waiting pensively and silently for the dance to begin again and the

fire

in their hearts to leap up and to wrap them anew; and so they

danced

and danced through Pavane and Saraband and Gallead the night

through, and many stood still to watch them, and the peasants came

about

the door and peered in, as though they understood that they

would gather

their children’s children about them long hence, and tell

how they had seen

Costello dance with Oona MacDermott, and become,

by the telling, themselves

a portion of ancient romance; but through all

the dancing and piping

Macnamara of the Lake went hither and thither

talking loudly and making

foolish jokes, that all might seem well with

him, and old MacDermott of the

Sheep grew redder and redder, and

looked oftener and oftener at the doorway

to to see if the candles there

grew yellow in the dawn.

At last he saw that the moment to end had come, and, in a

pause

after a dance, cried out from where the horn noggins

stood, that his

daughter would now drink the cup of betrothal; then Oona

came over

to where he was, and the guests stood round in a half circle,

Costello

close to the wall to the right, and the labourer, the farmer, the

half-witted

man, and the two farm lads close behind. The old man took out

of a

niche in the wall the silver cup, from which her mother and her

mother’s

mother had drunk the toasts of their betrothals, and poured into

it a

little of the poteen out of a porcelain jug, and handed it to his

daughter

with the customary words, ‘Drink to him whom you love the best.’

7

She held the cup to her lips for a moment, and then said in a

clear,

soft voice,

‘I drink to my true love, Tumaus Costello.’

And then the cup rolled over and over on the ground, ringing

like a

bell, for the old man had struck her in the face, and it

had fallen in her

confusion; and there was a deep silence. There were many

of Macna-

mara’s people among the servants, now come out of the alcove, and

one

of them, a story teller and poet, a last remnant of the bardic order,

who

had a chair and a platter in Macnamara’s kitchen, drew a French

knife

out of his girdle, and made as though he would strike at Costello,

but in

a moment a blow had hurled him on the ground, his shoulder

sending

the cup rolling and ringing again. The click of steel had

followed

quickly had not there come a muttering and shouting from the

peasants

about the door, and from those crowding up behind them; and all

knew

that these were no children of Queen’s Irish or friendly

Macnamaras

and MacDermotts, but wild Lavells and Quinns and Dunns from

about

Lough Garra, who rowed their skin coracles, and had masses of

hair

over their eyes, and left the right arms of their children

unchristened,

that they might give the stouter blows, and swore only by St.

Atty and

sun and moon, and worshipped beauty and strength more than St.

Atty

or sun and moon.

Costello’s hand had rested upon the handle of his sword, and

his

knuckles had grown white, but now he drew it away, and,

followed by

those who were with him, strode towards the door, the dancers

giving

before him, the most angrily and slowly and with glances at the

mut-

tering and shouting peasants, but some gladly and quickly because

the

glory of his fame was over him; and passed through the fierce and

friendly peasant faces, and came where his good horse and the rough-

haired

garrons were tied to bushes; and mounted and bade his ungainly

body-guard

mount also, and rode into the narrow borreen. When

they had gone a little

way, Duallach, who rode last, turned towards the

house where a little group

of MacDermotts and Macnamaras stood next

to a far more numerous group of

peasants, and cried,

‘Well do you deserve, Teig MacDermott, to be as you are

this

hour, a lantern without a candle, a purse without a penny,

a sheep

without wool, for your hand was ever niggardly to piper and fiddler

and

story teller and to poor travelling folk.’ He had not done before

the

three old MacDermotts from the Mountains of the Ox had run towards

their horses, and old MacDermott himself had caught the bridle of a

garron

8

garron of the Macnamaras, and was

calling to others to follow him; and

many blows and many deaths had been,

had not the Lavells and Dunns

and Quinns caught up still glowing brands

from the ashes of the fire,

and hurled them among the horses with loud

cries, making all plunge

and rear, and some break from their owners with

the whites of their eyes

gleaming in the dawn.

For the next few weeks Costello had no lack of news of Oona,

for

now a woman selling eggs or fowls, and now a man or a woman

on

pilgrimage to the holy well of Tubbernalty, would tell him how his

love

had fallen ill the day after St. John’s Eve, and how she was a

little

better or a little worse, as it might be; and though he looked to

his

horses and his cows and goats as usual, the common and uncomely

things, the dust upon the roads, the songs of men returning from fairs

and

wakes, men playing cards in the corners of fields on Sundays and

Saints’

Days, the rumours of battles and changes in the great world, the

deliberate

purposes of those about him, troubled him with an inexplic-

able trouble;

but the peasants still remember how when night had fallen

he would bid

Duallach O’Daly recite, to the chirping of the crickets,

‘The Son of

Apple,’ ‘The Beauty of the World,’ ‘The Feast of Bricriu,’

or some other of

those traditional tales, which were as much a piper’s

business as ‘The

Green Bunch of Rushes,’ ‘The Unchion Stream,’ or

‘The Chiefs of Breffany’;

and, while the boundless and phantasmal

world of the legends was

a-building, would abandon himself to the

dreams of his sorrow.

Duallach would often pause to tell how the Lavells or Dunns

or

Quinns or O’Dalys, or other tribe near his heart, had come

from some

Lu, god of the leaping lightning, or incomparable King of the

Blue Belt

or Warrior of the Ozier Wattle, or to tell with many railings how

all the

strangers and most of the Queen’s Irish were the seed of some

misshapen

and horned Fomoroh or servile and creeping Firbolg; but

Costello

cared only for the love sorrows, and no matter whither the stories

wan-

dered, whether to the Isle of the Red Loch where the blessed are, or

to

the malign country of the Hag of the East, Oona alone endured their

shadowy hardships; for it was she, and no King’s daughter of old, who

was

hidden in the steel tower under the water with the folds of the

Worm of

Nine Eyes round and about her prison; and it was she who

won, by seven

years of service, the right to deliver from hell all she

could carry, and

carried away multitudes clinging with worn fingers to

the hem of her dress;

and it was she who endured dumbness for a year

because

9

because of the little thorn of

enchantment the fairies had thrust into her

tongue; and it was a lock of

her hair, coiled in a little carved box, which

gave so great a light that

men threshed by it from sundown to sunrise,

and awoke so great a wonder

that kings spent years in wandering, or

fell before unknown armies in

seeking, to discover her hiding place; for

there was no beauty in the world

but hers, no tragedy in the world

but hers: and when at last the voice of

the piper, grown gentle

with the wisdom or old romance, was silent, and his

rheumatic

steps had toiled upstairs and to bed, and Costello had dipped

his

fingers into the little delf font of holy water, and begun to pray

to Maurya of the Seven Sorrows, the blue eyes and star-covered

dress of the

painting in the chapel faded from his imagination, and the

brown eyes and

homespun dress of Oona MacDermott came in their

stead; for there was no

tenderness in the world but hers. He was of

those ascetics of passion who

keep their hearts pure for love or for

hatred, as other men for God, for

Mary and for the saints, and who,

when the hour of their visitation

arrives, come to the Divine Essence by

the bitter tumult, the Garden of

Gethsemane, and the desolate rood,

ordained for immortal passions in mortal

hearts.

One day a serving man rode up to Costello, who was helping

his two

lads to reap a meadow, gave him a letter and rode away

without a word;

and the letter contained these words in English: ‘Tumaus

Costello, my

daughter is very ill. The wise woman from Knock-na-shee has

seen

her, and says she will die unless you come to her. I therefore bid

you

to her, whose peace you stole by treachery—Teig MacDermott.’

Costello threw down his scythe, sent one of the lads for

Duallach,

who had become associated in his mind with Oona, and

himself saddled

his great horse and Duallach’s garron.

When they came to MacDermott’s house it was late afternoon,

and

Lough Garra lay down below them, blue, mirrorlike, and

deserted; and

though they had seen, when at a distance, dark figures moving

about the

door, the house appeared not less deserted than the lake. The

door

stood half-open, and Costello rapped upon it again and again,

making

a number of lake gulls fly up out of the grass, and circle screaming

over

his head, but there was no answer.

‘There is no one here,’ said Duallach, ‘for MacDermott of the

Sheep

is too proud to welcome Costello the Proud,’ and, flinging

the door open,

showed a ragged, dirty, and very ancient woman, who sat upon

the floor

leaning against the wall. Costello recognised Bridget Delaney, a deaf

and

10

and dumb beggar; and she, when she saw

him, stood up, made a sign to

him to follow, and led him and his companion

up a stair and down a

long corridor to a closed door. She pushed the door

open, and went a

little way off and sat down as before. Duallach sat upon

the ground

also, but close to the door, and Costello went and gazed upon

Oona

MacDermott asleep upon a bed. He sat upon a chair beside her and

waited, and a long time passed, and still she slept on, and then Duallach

motioned to him through the door to wake her, but he hushed his very

breath

that she might sleep on, for his heart was full of that ungovern-

able pity

which makes the fading heart of the lover a shadow of the

divine heart.

Presently he returned to Duallach and said,

‘It is not right that I stay here where there are none of her

kindred

for the common people are ever ready to blame the

beautiful.’ And

then they went down and stood at the door of the house and

waited,

but the evening wore on and no one came.

‘It was a foolish man that called you Costello the Proud,’

Duallach cried

at last; ‘had he seen you waiting and waiting

where they left none but a

beggar to welcome you, it is Costello the Humble

he would have called you.

Then Costello mounted and Duallach mounted, but when they

had

ridden a little way, Costello tightened the reins and made

his horse

stand still. Many minutes passed, and then Duallach cried,

‘It is no wonder that you fear to offend Teig MacDermott of

the

Sheep, for he has many brothers and friends, and though he

is old he is

a strong man, and ready with his hands.’

And Costello answered, flushing and looking towards the house:

‘I swear by Maurya of the Seven Sorrows that I will never

return

there again if they do not send after me before I pass

the ford in the

Donogue,’ and he rode on, but so very slowly, that the sun

went down

and the bats began to fly over the bogs. When he came to the

river he

lingered a while upon the bank among the purple flag-flowers,

but

presently rode out into the middle, and stopped his horse in a

foaming

shallow. Duallach, however, crossed over and waited on the

further

bank above a deeper place. After a good while, Duallach cried

out

again, and this time very bitterly:

‘It was a fool who begot you and a fool who bore you, and

they are

fools of all fools who say you come of an old and noble

stock, for you

come of whey-faced beggars, who travelled from door to door,

bowing

to gentles and to serving men.’

With bent head Costello rode through the river and stood

beside

him

11

him, and would have spoken had not

hoofs clattered on the further bank

and a horseman splashed towards them.

It was a serving man of Teig

MacDermott’s, and he said, speaking

breathlessly like one who had

ridden hard,

‘Tumaus Costello, I come to bid you again to Teig

MacDermott’s.

When you had gone, Oona MacDermott awoke and

called your name,

for you had been in her dreams. Bridget Delaney, the

dummy, saw her

lips move and the trouble upon her, and came where we were

hiding

in the wood above the house, and took Teig MacDermott by the

coat

and brought him to his daughter. He saw the trouble upon her, and

bid me ride his own horse to bring you the quicker.’

Then Costello turned towards the piper Duallach O’Daly, and,

taking

him about the waist, lifted him out of the saddle, and

hurled him against

a grey rock that rose up out of the river, so that he

fell lifeless into the

deep place, and the waters swept over the tongue

which God had made

bitter that there might be a story in men’s ears in

after time; and

plunging his spurs into the horse, he rode away furiously

towards the

north-west, along the edge of the river, and did not pause

until he came

to another and smoother ford and saw the rising moon mirrored

in the

water. He paused for a moment irresolute, and then rode into the

ford

and on over the Mountains of the Ox, and down towards the sea,

his

eyes almost continually resting upon the moon, which glimmered in

the

dimness like a great white rose hung on the lattice of some

boundless

and phantasmal world. But now his horse, long dank with sweat

and

breathing hard, for he kept spurring it to utmost speed, fell

heavily,

hurling him into the grass at the road side. He tried to make it

stand

up, and, failing this, went on alone towards the moonlight; and came

to

the sea, and saw a schooner lying there at anchor. Now that he

could

go no further because of the sea, he found that he was very tired

and

the night very cold, and went into a shebeen close to the shore, and

threw

himself down upon a bench. The room was full of Spanish and

Irish

sailors, who had just smuggled a cargo of wine and ale, and were

waiting

a favourable wind to set out again. A Spaniard offered him a drink

in

bad Gaelic. He drank it greedily, and began talking wildly and rapidly.

For some three weeks the wind blew still inshore or with too

great

violence, and the sailors stayed, drinking and talking and

playing cards,

and Costello stayed with them, sleeping upon a bench in the

shebeen,

and drinking and talking and playing more than any. He soon

lost

what little money he had, and then his horse, which some one had brought

from

12

from the mountain boreen, to a

Spaniard, who sold it to a farmer from

the mountains for a score of silver

crowns, and then his long cloak and

his spurs and his boots of soft

leather. At last a gentle wind blew

towards Spain, and the crew rowed out

to their schooner singing Gaelic

and Spanish songs, and lifted the anchor,

and in a little the white

sails had dropped under the horizon. Then

Costello turned homeward,

his empty life gaping before him, and walked all

day, coming in the

early evening to the road that went from near Lough

Garra to the

southern edge of Lough Cay. Here he overtook a great crowd

of

peasants and farmers, who were walking very slowly after two

priests,

and a group of well dressed persons who were carrying a coffin.

He

stopped an old man and asked whose burying it was and whose people

they were, and the old man answered,

It is the burying of Oona MacDermott, and we are the

Macnamaras

and the MacDermotts and their following, and you are

Tumaus Costello

who murdered her.’

Costello went on towards the head of the procession, passing

men

who looked at him with fierce eyes, and only vaguely

understanding

what he had heard, for, now that he had lost the quick

apprehension of

perfect health, it seemed impossible that a gentleness and

a beauty

which had been so long the world’s heart could pass away.

Presently he

stopped and asked again whose burying it was, and a man

answered,

We are carrying Oona MacDermott, whom you murdered, to

be

buried in the island of the Holy Trinity,’ and the man

stooped and

picked up a stone and cast it at Costello, striking him on the

cheek, and

making the blood flow out over his face. Costello went on

scarcely

feeling the blow, and, coming to those about the coffin,

shouldered his

way into the midst of them, and, laying his hand upon the

coffin, asked

in a loud voice,

‘Who is in this coffin?’

The three old MacDermotts from the Mountains of the Ox

caught

up stones and bid those about them do the same; and he

was driven

from the road covered with wounds, and but for the priests would

surely

have been killed.

When the procession had passed on Costello began to follow

again,

and saw from a distance the coffin laid upon a large boat

and those

about it get into other boats and the boats move slowly over the

water

to Insula Trinitatis; and after a time he saw the boats return and

their

passengers mingle with the crowd upon the bank and all disperse by

many

13

many roads and boreens. It seemed to

him that Oona was somewhere

on the island smiling gently as of old, and,

when all had gone, he swam

in the way the boats had been rowed and found

the new-made grave

beside the ruined Abbey of the Trinity, and threw

himself upon it,

calling to Oona to come to him. Above him the

three-cornered leaves

of the ivy trembled, and all about him white moths

moved over white

flowers and sweet odours drifted through the dim air.

He lay there all that night and through the day after, from

time to

time calling her to come to him, but when the third

night came he had

forgotten, worn out with hunger and sorrow, that her body

lay in the

earth beneath; and only knew she was somewhere near and would

not

come to him.

Just before dawn, the hour when the peasants hear his ghostly

voice

crying out, his pride awoke and he called loudly,

‘Oona MacDermott, if you do not come to me I will go and

never

return to the island of the Holy Trinity;’ and, before his

voice had died

away, a cold and whirling wind had swept over the island,

and he saw

many figures rushing past, women of the Shee with crowns of

silver and

dim floating drapery; and then Oona MacDermott, but no

longer

smiling gently, for she passed him swiftly and angrily, and as

she

passed struck him upon the face crying,

‘Then go and never return.’

He would have followed and was calling out her name, when

the

whole glimmering company rose up into the air, and, rushing

together

into the shape of a great silvery rose, faded into the ashen dawn.

Costello got up from the grave, understanding nothing but

that he

had made his beloved angry, and that she wished him to

go, and, wading

out into the lake, began to swim. He swam on and on, but

his limbs

were too weary to keep him long afloat, and her anger was heavy

about

him, and, when he had gone a little way, he sank without a struggle

like

a man passing into sleep and dreams.

The next day a poor fisherman found him among the reeds upon

the

lake shore, lying upon the white lake sand with his arms

flung out as

though he lay upon a rood, and carried him to his own house.

And the

very poor lamented over him and sang the keen, and, when the time

had

come, laid him in the Abbey on Insula Trinitatis with only the

ruined

altar between him and Oona MacDermott, and planted above them

two

ash trees that in after days wove their branches together and

mingled

their trembling leaves.

W. B. YEATS.

MONNA ROSA

Elle est seule au boudoir

En bandeaux d’or liquide,

En robe d’or fluide

Sur fond blanc dans le soir

Teinté d’or vert et noir.

Un pot bleu japonise

Délicieusement

Dont s’élance gaiment

Dans l’atmosphère exquise

Oû l’âme s’adonise

Un flot mélodieux

Selon le rhythme juste—

De roses, chœur auguste,

Bouquet insidieux

Au conseil radieux!

Elle, belle comme elles,

Les roses, n’élit plus

Dans ses cheveux élus

Qu’une de ces fleurs belles

Comme elle, et de ciseaux

Prestes, tels des oiseaux,

La coupe ou, mieux, la cueille

Avec le soin charmant

D’y laisser joliment

La grâce d’une feuille

Verte comme le soir

Noir et or du boudoir.

Cependant

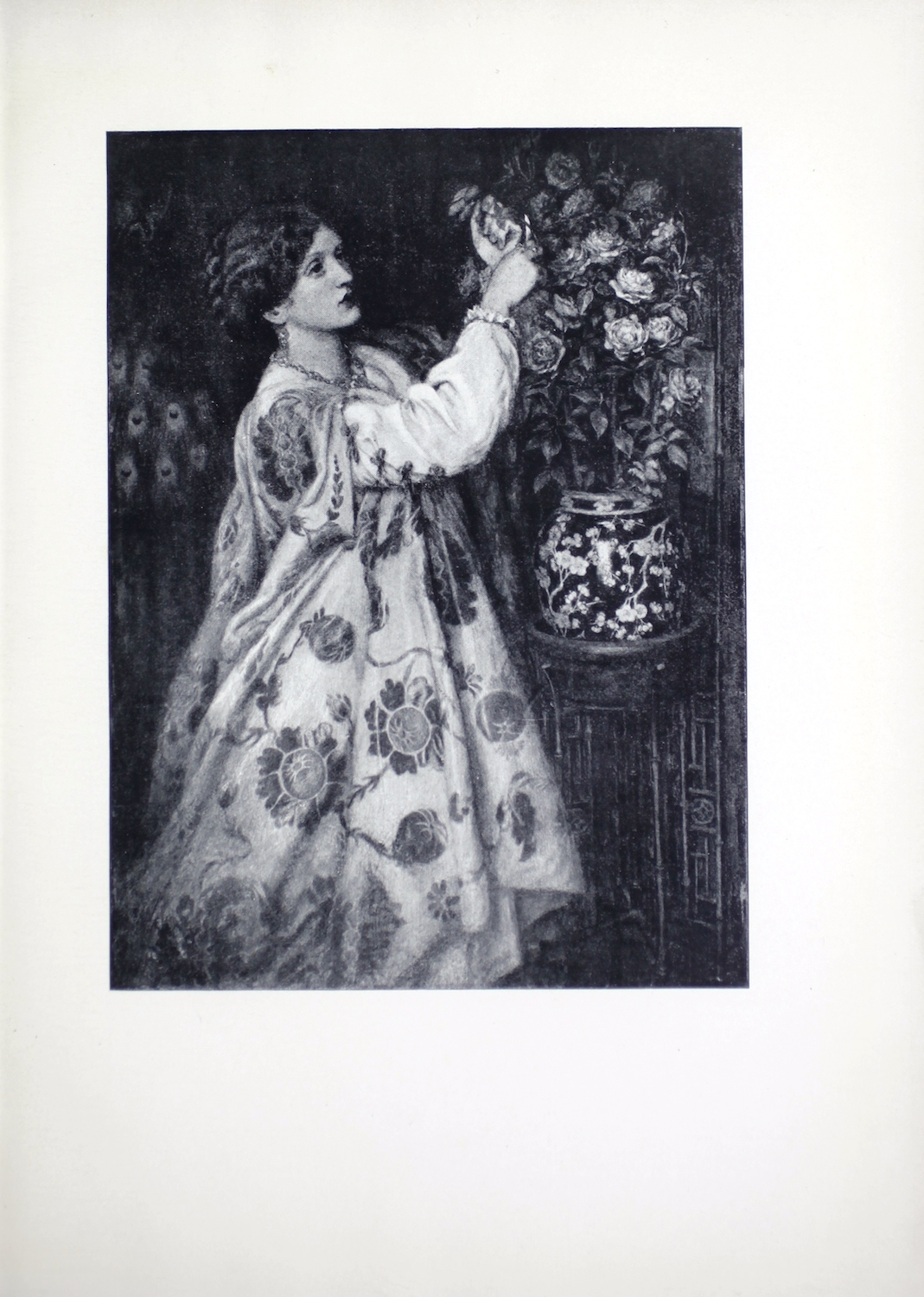

❧ MONNA ROSA

by

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

NIGGARD TRUTH

HARRIET came of farmers. The stout race

hesitated and hoped in the strong girl; at

last, for she never had any

children, finished

with her. Her mother had followed White-

field, and

Harriet held to the new Protestant-

ism; the men, decidedly retrograde

here,

were all for Pope Denys. At the time

when Harriet first had a

real existence,

symbolism might have called the grand-dad

Silenus, the

father Gambrinus, the brother Dionysos. These drank

and drank; oftenest in

their own complete and scandalous company;

but at all times they drank. She

said nothing, there being nothing

to say. Their cult brought her a new, at

times harassing, duty:

to see them laid out all three at night in the warm

kitchen, their

cravats loosened, and the fire safe extinguished. The

disgrace

of her family added little in the country to her own disgrace

of

Methodism. Her friends the Methodists found nothing surprising

in

the unregenerate state of men who had not come under the

only possible

saving influence. The farm went on, in a fashion,

thanks to Harriet. Had

she been less active and intelligent than she

was, she might have managed

it to profit, and her kinsmen might have

been her terrible luxury. Her

activity never hesitated to carry out

what a servant did other than to her

liking. Whatever her hands

touched was a pattern. Yes; but the

servants—especially as she was

kind, and often, of necessity,

ignorant—pandered to her mania to do her

own work herself. The farm, too

much for her, had at last to be let to

keep up the mortgages.

They had been rich, now they were poor. Harriet had nothing

in

her hands but work and care. The ‘pretty trio’ had the

management

of all else; their management followed its policy unhesitatingly

to the

logical end. Then the father and the brother died, and were

buried.

Silenus, missing them, became idiotic and eccentric. He took

liquor

in sudden aversion as a beverage; but, buying and getting what

he

could, he bottled and sealed drams which he buried all over the

country; and then, like a dog who would know how his hidden bone

putrefies,

he visited all the nooks strangely, staying out at night even

to follow his

poor fancy.

Harriet never ceased to work, either for gain and living, or

for mere

work’s

21

work’s sake. Once she had to repair

her stays ; she remade them. A

neighbour saw, admired, and had her own

renewed. Another and

another commission, and Harriet was proficient with a

definite occupa-

tion. She knew not how to mark time. Before long she had

dis-

covered an ‘improvement’ which made her wares famous, which later

she sold for a hardly bargained £600. She had her consolation in the

great

days of the patent, that she had fought hard for a good price,

bumpkin girl

as she was at the time of the sale.

Old Silenus died at last. Harriet, under contract to refrain

from

staymaking, was busy as ever with some equally ingenious

labour.

She never stopped to visit or idle, only going out to attend the

offices

of her church, or rather ‘chapel.’ There she was most punctual;

the

chapels life coincided evenly with hers.

The first time the new minister preached, Harriet selected

him for

a husband. It was Hugh Porter, the young man who came in

the face

of so many prejudices, being so young, and ugliness not

compensating

as much as it should. He had once had a kick in the face from

a

horse, whence a hideous malformation. He preached for an opening

with more than passion, with violence. Afterwards, and for many

weeks, he

was quiet, learned. Harriet watched him carefully; com-

pared, heard him

critically; at first thought him tactful, executing a

plan ; only found out

later that it was all accident, that the heaviness of

his beginnings was

but nervous defiance and waste of ammunition.

The sooner he had a calm

friend at his elbow the better for him; and

in addition she made a

memorandum in her mind—for use in their

married life, recognising a

radical fault.

They became acquainted. Harriet was very submissive to

her

‘minister,’ without shyness; in such a way that, in presence

of her

humility and deference, he forgot his regret that he was not a

clergy-

man. She did not mind his lack of judgment; he would have many

other lessons to learn. She took no umbrage at the rude way in which

he set

about his ‘inquiries’ into the conduct of her secluded life; and

he thought

himself so wise in this inquisition.

‘I never thought I should marry my minister.’ The pitch of

her

voice, the smile, the gravity which made her face look

thinner as she

said these words, almost gave him a glimpse of the future;

but the

marriage took place. It was soon found that he was extremely

deli-

cate. And the course of what are called unforeseen circumstances

turned strangely from the time of Hugh Porter’s marriage. Under-

hand

22

hand measures on the part of his

deacons threw him out, made him

redundant for a time, obliged to preach

every Sunday from a different

pulpit. Then it was he began to understand

Harriet. Then, for the

first time in his life, he wrote out his sermons

entire, and again and

again. Then, to patience and kindness in Harriet, he

rehearsed

delivery at oration pitch, and noted gesture. Shrewd Harriet! He

took

her advice, and refused the first offer of a pulpit as second in a

circuit,

alleging that he had some intention of going into a retreat, like

Saint

Paul into Arabia. In three months, the fame of his preaching was

ringing every week in The Recorder. Then a remarkable

event, what

in business is called a ‘deal,’ took place between the

Wesleyans and

the Methodists. A curious notion of Pan-Methodism was abroad,

and

a minister was exchanged for a great occasion in either body. Hugh

Porter was to preach in the great Walworth Road Church in London

to

Wesleyans. Harriet was present, in a place where Hugh could

not see her.

She heard his very low yet distinct preliminary announce-

ment: ‘My text

will be found. . . .’ Right! And then she waited for

the opening phrase,

almost performing mentally the process of sounding

a tuning-fork. Right

again! And he kept it up ; he showed what was

in him. Higher and higher the

flood of his oration swelled, and ever

the language grew more precise, the

argument stricter. Till the last

sentences came, sinking masterly to the

tone on which he began, and

the closing words sounded sweet and distinct as

the first. He took the

beef-tea she offered him in the vestry in silence.

Harriet could not

trust herself to speak, for joy.

The Recorder, a well-managed

paper, knowing the thoroughness

of the Wesleyan organ, came out

on Wednesday, not only with the

sermon at length, but with a leading

article upon it, headed: ‘That

Man!’ the phrase Hugh Porter had used and

repeated with such great

effect. This moment began Hugh’s life, though he

had had a hard

boyhood and harder youth. He thought he had known

struggling.

He found out what struggling means before he had learnt from

Harriet

where he stood towards his body and towards the world. She had

even in her extremity to use for the first time to him the words:

‘Take my advice.’ He had the wit to be wise. He had imagined,

when he

secured the wealthiest chapel in the Society, that the mil-

lennium for him

had come; that he had now only to enjoy his income,

have a library, go out

to tea, embroil himself with all the quarrels of

the laity under him, and

be master in his own house and out of it.

The

23

The time he gave to his sophistries,

otherwise directed, might have

made him half independent of Harriet; and

than this he desired

nothing more dearly. He wanted to love her and direct

her. He

aimed higher than he ever reached.

As it was, he held himself very quiet; it seemed Harriet did

not

make mistakes. The jealousies were not long appearing; the

mutter-

ings against ministers who interfere; the covert wonderings what

he

did with his income. It was hard for Hugh. His policy towards the

members was not of his own invention; he carried it out mechanically,

awkwardly; feared all the time it was right, the only policy. He

never

refused invitations to preach out of his own circuit, by Harriet’s

advice.

And let him not misunderstand: his sermons were to be

staid, even dull, on

no account sensational. He did as he was bidden.

Reasons for all this? A

dozen times he had almost asked: ‘And

what then?’ Well that he checked

himself. As it happened, it never

came to such a question, but how shocked

Harriet would have been!

How could she have told him what might be the

Lord’s inscrutable

will?

Once, vague gratitude supplanting perplexity, he was nigh

thanking

her watchfulness. He put down his awful commentary, and

pretended

to yawn. Harriet looked up with anxiety. (She was making a pair

of

stays.)

‘Well, my Hugh, what is it?’ He sighed a little, and

smiled

‘My poor Hugh is looking tired.’

‘No, Harriet,’ he said sententiously, as though giving out a

hymn,

‘not tired.’

‘Shall we talk then?’ and with that dawned the most terrible

hour

Hugh had ever known; hour which set stormily, misty, and

blurred

with tears. In brief, he must resign, give up his chapel. He

was

stupid, mouth agog, when he caught the intention of her slow, hard

sentences. She was mad; he said so, at last, after repeatedly checking

the

words on his lips. She gave no heed, made no answer; her calm

no whit

ruffled. He could not help himself; he thought it seriously.

Through the

torrents of his objections to each deliberate phrase he

followed his

thought: the possibility that she was a wild woman; like

the mad, gifted

with supernatural penetration.

Give up his ‘position’? Give up his thirty pounds a quarter?

‘Oh, Hugh, Hugh!’

And their little house, so comfortable, with fitted blinds

all through;

to

24

to go to some miserable place in the

country, perhaps! Useless to

talk; he knew this fully ten minutes before he

ceased to be coherent.

The circuit was too large for him. His early years

had been passed in

the country: it would do him good if he were sent back

to it.

Nothing was said next day. It was a Wednesday; and a

com-

mittee meeting after the service. Harriet did not wait for

Hugh in

the chapel as her custom was. She simply told him, as she gave

him

his comforter, that she had something to do; must go home.

The committee meeting began as usual with a prayer by the

eldest

of the deacons. This ceremony passed drily. Hugh

proceeded at

once to run over the accounts; threw the book on the table as

he

finished. There was the shadow of a pause.

‘And now, gentlemen,’ said Hugh,

‘I have something to tell you,

something which lies so heavily

on my heart that I shall be easier

when I have told it: it seems the Lord’s

will that I should leave this

circuit. The circuit is large, my health is

far from good, and I do not

flatter myself that you will have a great

difficulty to fill my place. I

hope you will be able to say, gentlemen,

that I have been a good

minister among you here present as deacons, and

among you all as

members/ He finished, much moved.

‘You are young, sir, to be our minister here . . .’ began a

younger

deacon.

‘Think it over a bit, sir,’ the doyen broke in, roughly. ‘I propose

a committee

meeting this day week, while you think it over, sir.’

‘No, my brethren,’ said Hugh, more humanly. ‘It is thought

over

already. I did not come here myself; I did not seek to come

here.

He who sent me hither now sends me hence. If we are allowed to

exercise our judgment, minister and members, in coming together, we

must

recognise His will above it all. I have to ask your permission

to

resign.’

‘Which we all refuse.’

‘No, brother, it need not take long; talk it over here and

now.

You will find me in the chapel when your decision is

taken.’ He suited

his action by leaving the vestry.

They accepted his resignation.

Hugh had a moment of satisfaction as he walked home.

This

hearty, blunt action of his came at the moment when a

long-nursed

grumble of his deacons was about finding vent. But his joy was

not

long-lived.

25

‘I have resigned,’ said Hugh. ‘The circuit is large, I don’t

say too

large, but they want mere age in their minister, these

people.’

For this announcement, he tried his uttermost to speak

without

expression, to leave Harriet in doubt whether he sulked

or not. A

touch of her fingers was all Harriet’s reply; save that she was

very

motherly that night, appearing almost in a new aspect.

Hugh was sent to a small west-country village, or rather to

two

villages, four miles apart. The Porters found a roomy bright

house

for them, rented by the Society, with a certain quantity of solid

furni-

ture in it. They felt quite wealthy when they were installed.

The

only difficulty was the distances to travel. This was soon felt

heavily,

for Hugh began to be suffering and more delicate from the first

week.

He lost his spirits, his appetite; grew restless at night. Harriet

kept

her head through this trouble; she knew almost all it was

necessary

for her to know, to guard him and tend him well. But there

re-

mained between them want of familiarity. When his ailing was so

far

confirmed that he could look upon it as a definite and more or

less

permanent thing, Hugh became nervous on the subject lest Harriet

might think he was malingering. She knew this anxiety of his; for

once was

baffled, not knowing how to reassure him.

Harriet urged her husband to take some pupils, to amuse him.

Two

boys were found, of eight and eleven. After a week Hugh

refused to

have anything to do with them. Harriet added to her tasks of

feeding

and grooming, that of training them. These boys turned out

wonder-

fully well. Harriet saw each of them make a fortune in

business.

Time came when Hugh left his wife for a whole week, to

conduct

a ‘revival’ at Bristol. When he came back, a shed

adjoining the house

had become a stable; the stable contained a mare. He

gave himself

over to surprise and delight. It so astonished him that

Harriet had

found such a smart, useful animal, that he forgot to ask what

had been

the price of her; and he never knew. The pleasure of his new

play-

thing made Hugh seem his old self for a time. It was a joy to see

him

grooming the mare, spreading her litter, feeding her. At length,

in-

evitably, came weariness of the work: the trouble of it spoilt the

advantage and pleasure of riding; Harriet was forced into suggesting

a man

to take this duty off Hugh’s hands. Henceforth a man was

supposed to attend

to the mare. Hugh never saw this man, nor did

he ever make any inquiry

concerning him. One thing remained, for

nearly a twelvemonth at least: the

distance between village and village

was

26

was no excuse between Hugh and the

fulfilment of his duties. Of

course, this had to come in the end. It began

with obstinacy to go

to the neighbouring village on nights so awful that

scarce ten souls

would be assembled for his ministrations in the chill shed

they called

a chapel; that, too, at times when his cough was deep, shaking

his

poor body, so hidden inside the inches of woollens and cloth in

which

Harriet kept him swathed. Then clear, sheer laziness, variously

dis-

guised or perfectly frank. Harriet soon exhausted what few words

of persuasion she could afford for such extremities, and passed without

pause to acts. The occasion was repeated when Hugh was disinclined

to go

take his service, away over the heath. No word; Harriet was up

to her room

and down again in five minutes.

‘Hugh, I shall be there before you,’ the thin woman’s voice

piped

cheerily, and she was out of the house. A mile and a half

of wet road,

and Hugh passed her at a trot; she let the hoof-strokes die

quite

away, then, with unaltered brisk step, turned about towards their

home;

she had so much to do in the house!

So Hugh grew more and more a child as he aged and

shrunk.

This in his mere personal manliness, for to the outside

he was more

and more each year the image of the ideal Harriet had set for

him,

though all their life she had never so much as said to him: ‘I am

ambitious for you.’ In town or country pupils were always passing

through

his house to success in the ministry, in business, and profes-

sions. He

edited Hugh Bourne, and had heard of Fox and William

Law. He composed test

papers for sprouting divinity. Above all, he

preached through the length

and breadth of England; few preachers

of the denomination were more sought.

A wretched block, which the

enterprising Recorder had had cut from a photograph of him, went the

round

of the Methodist press for years.

The Porters hardly took count of time. Their life together

had

been so long. The history of the world was narrowed for them

into

the span of their married life. Years were passing, though they

seemed to stand still. Not only was Mrs. Porter grown the thinnest

woman

imaginable, and her thin voice incredibly thinner, and more

quavering

almost than a voice can be; but Sophy, Mrs. Porter’s cousin,

had become

Miss Short, and staid at that.

It was at a period when, for the first time, she had the care

of six

pupils. Harriet dearly wanted a female in her house who

was not a

servant; some one worthy to receive her tradition, who in case of her

death

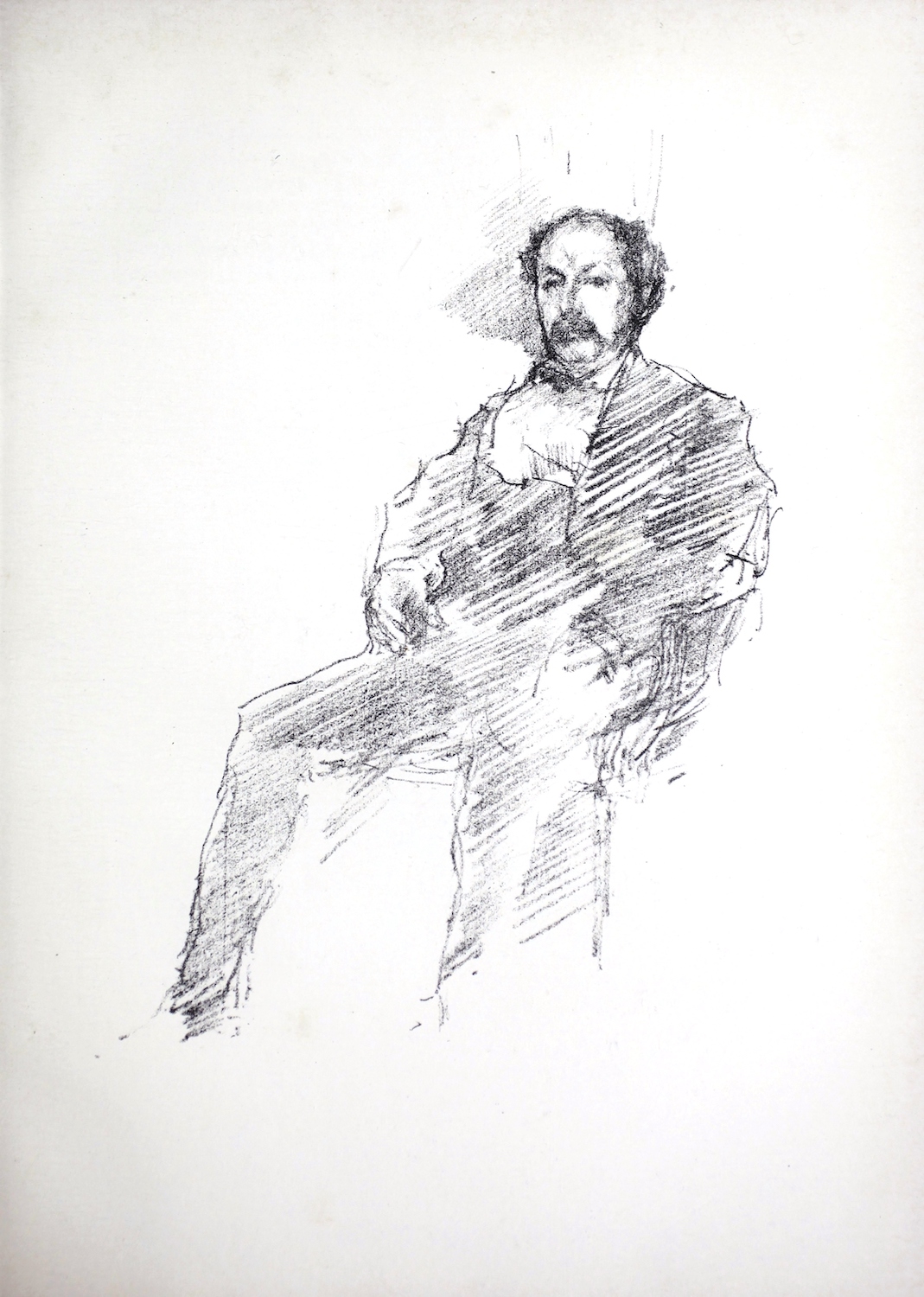

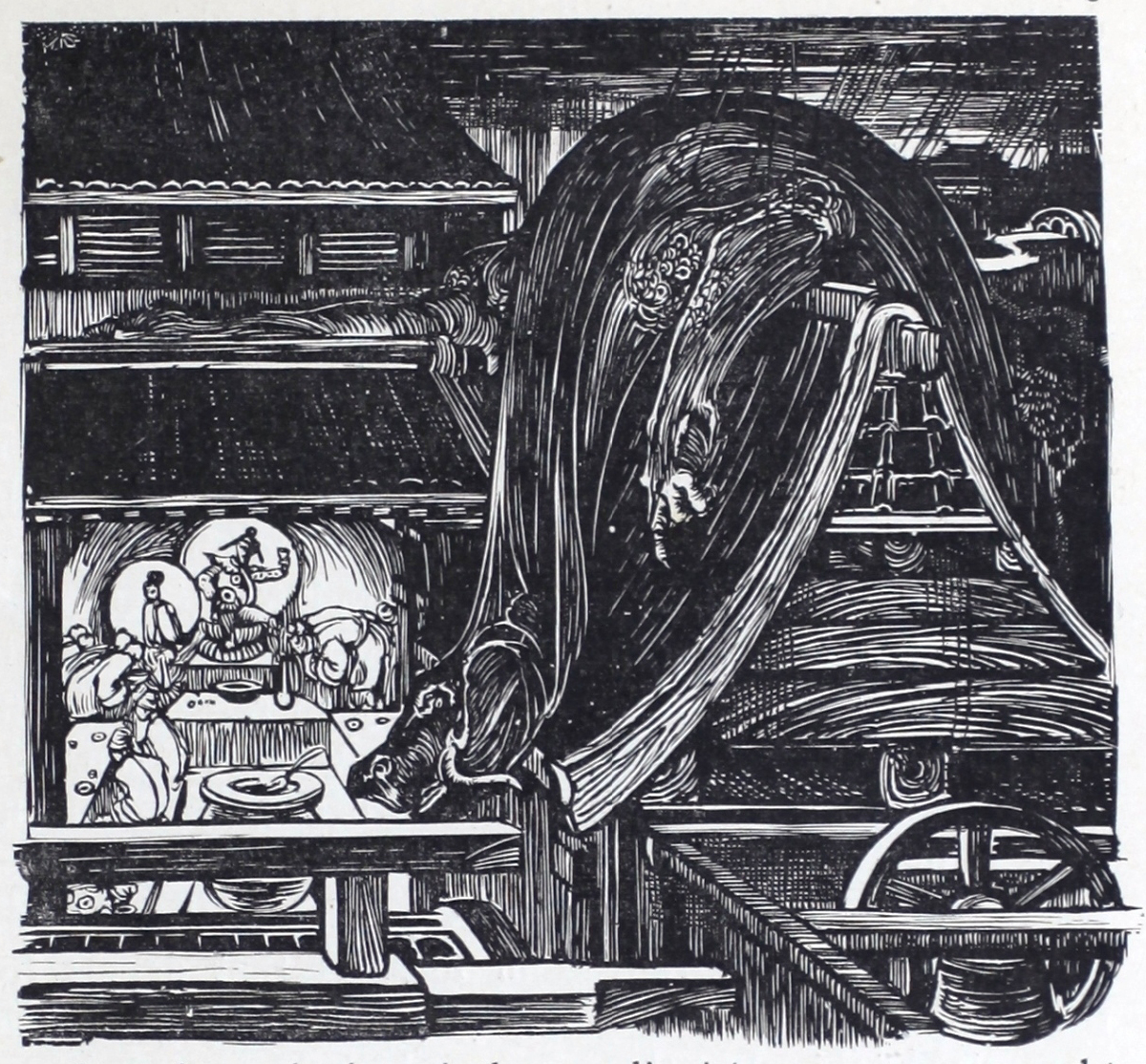

❧ THE DOCTOR — PORTRAIT OF MY BROTHER

an original lithograph

by

James M’Neil Whistler

31

death could look after Hugh, in

all that phrase implied. She had cast

about in her memory: her cousin Sophy

must be fourteen; she gave

days to reflecting on the girl’s ‘breed’

(Harriet believed in breed);

felt sure in the end that, accidents apart,

she could make something of

Sophy. The child turned out, as she became a

woman, the very finest

bit of mortal clay Harriet had ever had the handling

of; so quiet, so

intractable; long-suffering, and so savage. Any impression

made on

such a character lasts. So Harriet thought, and was glad because

of

Sophy Short. There was always perfect accord between the two, but

never, never peace ; they were destined to be noble friends one day.

Such a

pupil for such a mistress!

The two women became a sort of society. They spoke so

little

except between themselves: they treated Hugh with such

equal kind-

ness that they were almost to him as one. Whatever he required

done

either of them did, with the same readiness, the same silence, the

same

perfection. He gave up at length distinguishing their names,

using

them indifferently; they fell in with this arrangement. Hugh

thought

he had reached beautiful old age. He was very white. Wherever

he

went the fuss about him was extraordinary, even for so mild and

ugly

an old gentleman, and so renowned a preacher. The Juggernaut

homages he had been accustomed to receive for years (let us say

this was

the cause) had led him to make a collection of the most

sickening cliches,

to which he made an occasional addition, about

‘getting nearer the light,’

and the like, phrases which sounded like

tinned Longfellow. Poor old Hugh!

But in pulpits he was different.

Once above the heads of a thousand

listeners, he found old fire to

recite old sermons. Harriet seldom heard

him; for one reason that

he rarely preached in his own circuit, where a

grateful Society gave

him more assistance than he required. When she did,

she was pro-

minent in the chapel, nodded vigorous approval, with more

than

punctuality, at each full period, constituting herself a silent

claque.

‘We shall not have Mr. Porter with us much longer,’ startled

Sophy

one quiet morning.

‘What do you mean, Auntie?’ asked Sophy angrily. ‘How

can

you be so stupid? How do you know?’

‘Mark my words, dear, you will see.’

‘How do you know?’

‘Mark my words.’

It seemed a foolish prediction, for Hugh had never been

better

or

32

or livelier to Sophy’s knowledge.

She drew attention to this next

day.

‘That is just it,’ answered Harriet. ‘He is so active.’

There was not a trace in her manner of any feeling other

than

satisfaction in her prophecy. Sophy was far less contented.

After

tea, when all three were sitting together, Hugh rose from his

chair

rather suddenly, and Sophy, on the watch, burst out at him:

‘Don’t be so active, Uncle, you make me cross.’

Hugh was bewildered, but Harriet laughed:

‘Don’t mind her, my dear; she is growing old.’

‘Be more careful,’ Sophy persisted sullenly; ‘where’s your skull-cap?’

Her prophecy came true quickly enough to surprise Harriet

her-

self. The very morning following Hugh was not allowed to

get up;

congestion, pneumonia. The crowd at his burial was enormous.

The

grave-side encomiums were more sincere than grammatical.

‘I have only to think now of following him,’ said Harriet. A

large

subscription to support her widowhood was raised in the

Society.

Hugh had lain dead a whole week before burial, for certain

reasons.

Harriet was glad of this. Day after day the weather

seemed so bad

for Hugh to begin his sojourn under clay. Many a troubling

phrase

came from Harriet while he still lay upstairs; phrases the

heareis

excused, supposing them fruits of her excitement; troubling not

in

their sense but in the expression: Hugh among angels the subject,

right and pious enough as a notion; but the thin old woman had a

wild way

of knowing what she spoke of. Hugh, bright and young and

ransomed, in

spiritual company. But the companions were not so

feathered as sometimes

seen, and their locality to Harriet was never

vague or very distant. For

her they were in the house or the little

garden ; or against the corpse in

prayer. When they were in the

drawing-room, Harriet spoke of them, though

not in direct statement

as in a definite part of the room; and talking

currently and topically.

Sophy and chance women lost patience at last,

though they dared

not show this. Their materialism was low and timid.

Against this (and the superficial may wonder), the corpse

upstairs

was still Hugh. When it had been buried it was still

Hugh. Thrice,

while he waited for burial, his grave costume was changed;

finally he

went to rest in a long scarlet flannel robe, a passionate

Christian symbol

the excuse, that he might be warmer and look more

comfortable in the

earth, but chiefly that Harriet might see him better. Hints she dropped

of

33

of this intention were far too

obscure for Sophy to penetrate. None

remembered that Silenus lived again in

his granddaughter: the old

idiot who had intercourse with his dead through

the medium of

medicine-bottles full of brandy. But Silenus was crazed;

fancy broke

its bounds in his brain, so that he was obliged, with stiff

fingers, to

unearth the drams, to see if the dead had drunk, to drink with

them.

Harriet was quite ready to take up her life again the very

hour

Hugh was put in the dust. Sophy allowed the household work

to

be resumed next day. It passed much as usual, only interrupted by

an occasional snivel of Sophy. Harriet loved facts. Sophy waited

patiently

for the old woman to return to such expressions as she had

used during the

week her husband lay dead—to criticise them, and

admonish her; but she

waited in vain. Only during that week had

any one heard Harriet speak of

the dead and glorified as she had then

spoken; both before and since, all

her utterances on such subjects were

strictly theological, and very scanty.

Her care was always for the

maintenance or improvement of material

surroundings. Here Sophy

seconded her with staunch intention. The two women

kept up their

house as though its inmates were twice as numerous, with as

much

enthusiasm as though they were on the threshold of life. Indeed,

now

Hugh was out of the way, there needed no mystery about the turning

out and scouring which he loathed. They might wash the chimney-

pots every

day, and no one would scowl and whimper, and take to bed

of ennui. Harriet had attained her very ideal of

housewifery, only to

find it hopelessly flawed by the fact that she could

not do all herself.

A failing frame fought her ravenous spirit of toil; for

hours, literally

straightened limbs forced her to idleness, while Sophy

never sat down,

never halted, the long day through: inventing epic tasks,

lifetime

tattings and microscopic patchworks, to employ the hours of

lamp-

light. The only seeming solace Harriet had was that she might

command idleness in Sophy; but how could she do that? Indeed,

Sophy might

refuse to obey her.

However, she took care to set aside, for the time when she

was

forced to sit down, certain employments to which repose was

no barrier.

Chief among these was the care of the ‘silver,’ the

electro-plate she

possessed. Her malice loved to see as much of the

‘silver’ used as

possible, on all occasions: dishes, covers, forks,

spoons, toast-rack,

cruets—such wealth of bright metal as Harriet thought

well nigh in-

credible. It was a joy of joys to her to be surrounded with

her

‘silver’;

34

‘silver’; lovingly to clean and

polish, and then wrap each object in

white tissue-paper, just as they had

been received from the shop.

‘What beautiful new spoons!’ ‘New spoons,’ she

would laugh, ‘well,

they are not very old; I have had them fifteen years.’

With all the

things in the house she valued it was the same. A great

jealousy lest

Sophy should interfere with them for any purpose. It would be

time

enough for her to touch the precious things when they were her

own.

There was never any question on the subject; it was so well

under-

stood that Sophy inherited all the possessions. And not exactly

inherit either; the goods, and that vague wealth in the funds, which

she

would have at Harriet’s death, would come as a life’s wages de-

ferred. For

this she had toiled, brain and hands, to the full of her

powers, for the

Porters. For this she had kept herself fast, never

suffering a thought of

marriage, for example, to loiter in her mind.

She knew, latterly, as she

grew to know Harriet somewhat, that her

legacy would be considerable. She

arrived queerly at this knowledge.

Harriet made no secret of the ‘wage’

understanding; she was finically

just; and she set a higher value on

thorough manual work than on

most things.

It seemed near, too, now. Sophy waited from day to day to

hear

Harriet say, as she had said before: ‘I shall not be with

you long.

She had her angry answer ready, but it was never called for.

So

quickly as almost to be noticeable from one week to another,

Harriet

spent less and less of her day on her feet. Less and less too was

she

able to use her fingers. Her life drifted more every day towards

one

chair, one which had been her affectation somewhat, ever since

Hugh

was taken away. Sophy thought she had always a strange look when

sitting in it. It was true. Harriet loved, since she must be idle, to be

idle in that chair. From it—for it was never moved—the light of the

little

sitting-room favoured her seeing what passed before her mind

when she was

reflective. She would pause sometimes in her work of

cleaning the ‘silver,’

and sit with tea-pot and chamois leather quiet in

her hands, and a fixed

look in her eyes. She still persisted in cleaning

the ‘silver’; but as she

was able to take care of less, less was used.

When Harriet was in this almost cataleptic condition—and at

last

it was characteristic—all offers of ministration, and all

inquiries from

Sophy, were met with thanks and: ‘I am just thinking. Sophy

would

wait to see if anything would be added. But only a twinkling

smile

answered her curiosity, or a vague sentence cut short in the middle,

changed

35

changed presently to some matter

of fact, to the valuables she would

leave at her death: ‘You had better

have all the silver replated, my

dear; then it will last for years. And you

must have the drawing-

room clock cleaned. Don’t be afraid to spend money

having every-

thing done up. Then it will be as though you were starting

for your-

self. I shall come back, perhaps, and see what you are doing; but

you

wont see me! Then such a funny little laugh.

‘Don’t be so stupid, Auntie. It’s nothing to laugh at.’

Auntie thought she had the laugh, all the same. ‘Silver’ and

clocks

and money in the funds she left Sophy; the rest she took with her, into

the grave and out

on the other side. Sophy would not see her; Sophy

would not see anything

but house-linen and spoons. Hugh had never

seen anything; question if he

saw much now; she saw him.

‘Now, Sophy, I want you to do something for me,’ said

Harriet.

‘Address an envelope to the manager of the bank,’ Sophy

did this.

Harriet slipped into the envelope a folded letter. ‘I want you to

take

this to the bank. Give it to one of the clerks and wait for an

answer.’

‘You will be all right until I come back?’ said Sophy;

mere

courtesy, for Harriet wanted little most hours of the

twenty-four. She

went out into the scullery where a charwoman was soiling the flags, in

the language of her irony,

at two shillings a day, and sent her off. A

cynical precaution; Harriet was

practically helpless, and the woman

might ransack the house. Then she went

upstairs and dressed herself

out in all the best she had. She had never

felt so ‘silly’ in her life; one

moment excessively serious, as though she

were going to take posses-

sion of the bank as a symbol of untold fortune;

the next, as utterly

conscious before the glass, posing her bonnet upon her

flattened hair.

She had never before worn all

her best on a weekday. She went off

to the bank without saying good-bye; so

much did she realise the

perfection of her appearance. The letter she

carried contained only a

blank sheet of paper.

At the slam of the street door, Harriet was alone in the

house;

alone with the accumulations of her life. She looked

slowly round the

little sitting-room, resting on each object with the same

thought. The

square table would be Sophy’s, the round one too; the china in

the

corner cupboard, each piece of china singly. The cupboard itself

was

a possession. The canary in its cage before the window would be

Sophy’s, the maidenhair ferns and the variegated houseleek below it.

All

would be Sophy’s, every visible object. Through the wall there,

in

36

in the drawing-room, which she

knew so well that the partition wall

scarcely existed, the piano (which

would have to be tuned), the

inlaid sideboard, and the candlesticks and

stuffed birds upon it, would

be Sophy’s. Hugh’s presentation Bible would be

hers; the rugs, the

pictures on the walls, the curtains, the coal-box, the

gilt-legged chair,

all must be left behind. Sophy would have all. Down

below her feet,

through the floor, all the crockery on the dresser would be

Sophy’s.

All the brass on the high black mantelshelf, the warming-pan

hanging

by the dresser, the commoner knives, the old clock, all the pots

and

crocks would be Sophy’s. A mayor’s dinner might be cooked in that

kitchen. Upstairs, the great bedsteads, the presses full, crammed with

linen, would be Sophy’s. Whatever happened, Sophy would never

want’ linen.

She herself would want one nightdress between her bones

and her coffin:

they would hide her neck with a napkin, and cover her

feet with another;

all in the common way. She left no directions on

this point. The costume of

the dead calls for loving invention. Sophy

would not rise to this; she did

not know.

All the silver in the cupboard beside her would be Sophy’s,

all

wrapped in tissue-paper and safe inside baize-lined boxes.

All would

be Sophy’s; the hassock under her feet, the chair in which she

sat, the

clothes she wore, the shawl about her head, her brooch, her

mittens,

her slippers. All tangible things in the house were nearly

Sophy’s

own now; very nearly. What was all the house, with walls so

thin

and frail, as earthly substance is, that her poor eyesight was

not

stopped by them, pierced them like clear water or clear air? The

lines

of the room threatened to fade altogether at the bold thought.

The

lines of the window-frame wavered and curved; the horizontal

arched,

the perpendicular lines curved outwards as they dropped. It was

not

much she was leaving; perhaps she was not leaving much behind

Something, too, she took away. She had told Sophy where her will