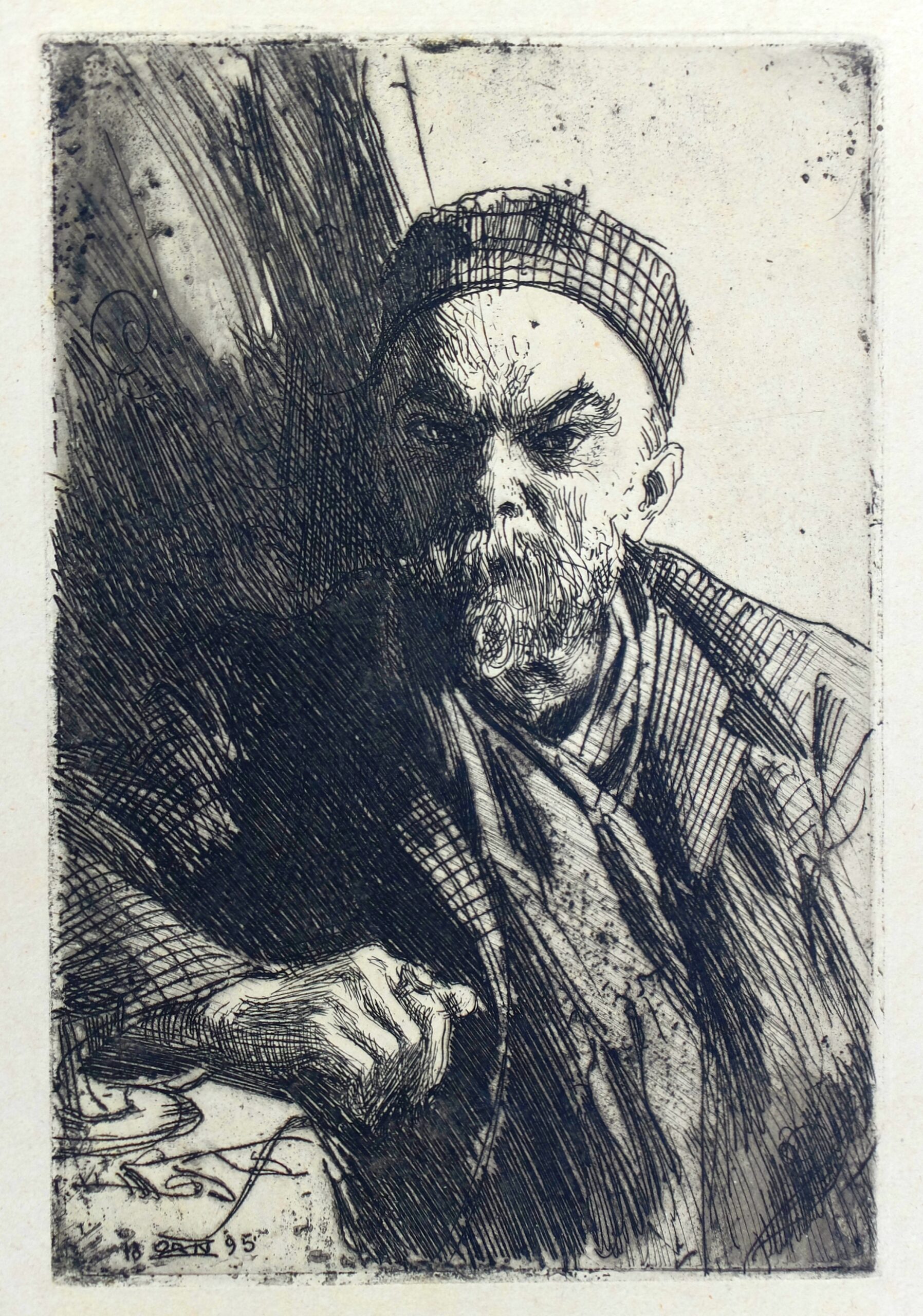

Paul Verlaine

(1844 – 1896)

Born in 1844 at Metz in northeast France as the only child of an army officer, Paul Verlaine’s life was characterised by personal and professional turmoil. He is, however, now recognised as one of France’s foremost poets of the nineteenth century. His work tends to emphasize moods and sensations over more direct forms of statement. It is closely associated with Decadence, a label he neither fully embraced nor rejected. Verlaine’s experiments with metre cement the evasive, fleeting quality of his verse, creating uncertain, evocative rhythms that draw out the rich acoustic properties of his poetry. His sexuality and personal circumstances made Verlaine’s work largely taboo in the Anglophone world until the 1890s, when his work was embraced by the British avant-garde and discussed more widely in various periodicals.

After his family moved to Paris in 1851, Verlaine studied at the Lycée Bonaparte. Upon finishing his baccalaureate, plans were made for him to study the law, but he did not prove suited to it and worked instead as clerk for an insurance company and the Hôtel de Ville in Paris. His early development as a poet was precocious. Inspired by the work of Victor Hugo (1802-1885) and Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), Verlaine fell in with a group of Parnassian poets who met at the bookshop of Alphonse Lemerre (1838-1912) in the Passage Choiseul. Still in his twenties, Verlaine contributed to the first two volumes of the Parnasse contemporain (“Contemporary Parnassus”) in 1866 and 1871. His poetry appeared there alongside work by Catulle Mendès (1841-1909), Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-1898), Leconte de l’Isle (1818-1894) and his literary hero, Baudelaire, who was also a strong influence upon Verlaine’s first collection, Poèms saturniens (“Saturnine Poems”), published in 1866 by Lemerre.

Three years later, Verlaine published his second collection, Fêtes galantes (“Gallant Revels”) in 1869. Evoking the paintings of Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), many of the poems contain partial vignettes of pastoral scenes featuring stock characters from commedia dell’arte such as Columbine and Pulcinella. This collection established Verlaine as a poet of hints and moods, but his poems are also full of sharper insinuations behind the gauzy veil of their rural settings. There are glimpses of tensions amongst the participants in his elegant countryside gatherings.

Around this time, Verlaine met and fell in love with Mathilde Mauté (1853-1914). Mathilde was ten years younger than him and inspired Verlaine to write a short collection of poems based upon their courtship, La Bonne chanson (“The Good Song”; 1870). The two married in 1870, just as France went to war with Prussia. Theirs was not, however, a successful marriage: Verlaine had become an alcoholic and was prone to violent outbursts. He mistreated his mother and proved violent towards his wife too.

During the Siege of Paris in 1870 as the Prussian army invaded France, Verlaine served in the National Guard, but was imprisoned briefly for seeking to avoid his military duties. Verlaine was then linked with the Paris Commune – the revolutionary uprising that followed the withdrawal of Prussia’s occupying forces, which was brutally suppressed by the French authorities. There are, however, conflicting accounts regarding the nature and extent of his involvement.

It was at this point that Verlaine met the teenaged poet, Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891), who had run away from his home in Charleville and travelled to Paris in late 1871. Verlaine took Rimbaud into his home and the two men became lovers (despite the fact that Mathilde was very heavily pregnant with Verlaine’s son, Georges). The relationship between Verlaine and Rimbaud is the stuff of literary legend and gossip. Over the next couple of years, Verlaine abandoned his wife, and the two poets drank, drugged, fought and argued their way around Northern France, Belgium and Britain, where they settled briefly in London’s Soho and Camden neighbourhoods. Their tumultuous relationship culminated in Verlaine firing a gun at Rimbaud during a drunken row in Brussels during July 1873. The bullet hit Rimbaud’s wrist, and Verlaine was arrested and imprisoned at Mons for two years.

But Rimbaud was also important in encouraging Verlaine’s continuing experiment with poetic form. It is widely acknowledged that his influence can be felt upon the poetry in Romances sans paroles (“Songs without words”; 1874) and it is this volume of short, broken, evocative lyrics, such as the “Ariettes oubliées” (“Forgotten Melodies”), by which Verlaine is probably best known. Verlaine’s complex personal circumstances – his broken-down marriage, tempestuous relationship with Rimbaud, and restless travels – are caught in settings such as the “Bruxelles” (“Brussels”) sequence and in translinguistic elements, such as the choice of English titles (“Streets,” “A Poor Young Shepherd”). Fraught emotional states register within the vestigial details of Verlaine’s loose translations and derivations from English texts, such as the poetry of Longfellow, which underpins his most famous lyric, “Il pleure dans mon Coeur” (It is raining in my heart).

Verlaine’s imprisonment, his conduct towards his wife and mother, and his relationship with Rimbaud, led to an informal boycott of his work. He was deliberately excluded from the third volume of the Parnasse contemporain (1876) and seems to have been dropped by his publisher, Lemerre. A collection of religious verse Sagesse (“Wisdom”; 1880) is the exception to this period of literary exile. Published by a small Catholic press, the poems gave voice to a religious conversion that Verlaine experienced in prison. After his release, Verlaine moved to England for two years, where he worked in schools in Lincolnshire and on the Isle of Wight, teaching French, Latin and drawing. In 1877, he moved back to France, where, as well as stints working as a teacher, he tried farming at Arras, in the north. During this period, he entered into a relationship with one of his school pupils, Lucien Létinois. He would later record his grief at the boy’s early death from typhoid in 1883 in a long poem within the collection, Amour (“Love”; 1888).

Verlaine’s re-accommodation within Parisian literary circles during the 1880s was largely due to the enthusiasm of a younger generation of writers, including Charles Morrice (1860-1919) and Jean Moréas (1856-1910), who saw in his work the seeds of Decadence, a literary movement taking hold at that time. He acquired a new publisher, Léon Vanier (1847-1896) and marked his return to literary life with the publication of Jadis et naguère (“Yesteryear and Yesterday”; 1884), which mixed new work with compositions from previous decades. This collection helped foster his status amongst younger adherents of Decadence and Symbolism, by including poems such as “Langueur” (“Langour”), which opens by declaring: “Je suis l’Empire à la fin de la decadence” (“I am the Empire at the end of decadence”). It also incorporated his manifesto poem “Art Poètique” (“The Art of Poetry”), which urges writers to take eloquence and “wring its neck.” Verlaine helped further cultivate this image by publishing a series of literary portraits, Les poètes maudits (“The Cursed Poets”; 1884) under the anagrammatic pseudonym of “Pauvre Lelian” (“Poor Lelian”). These studies of himself and his contemporaries, including Rimbaud, Mallarmé, and Villiers de l’Isle-Adam (1838-1889), construed them as outsiders and “cursed” poets.

Verlaine settled in Paris during 1885, where he took up an itinerant literary life, floating around cafés and being fêted occasionally by younger members of literary society. As he documented in Mes hôpitaux (“My Hospitals”; 1886), Verlaine suffered from ill health. He spent his last decade in and out of various medical institutions receiving treatment for arthritic rheumatism, exacerbated by his chronic alcoholism and possibly by venereal disease. He set up household on the rue Saint Jacques with Eugénie Krantz, a former mistress of the Minister of the Interior, but also slept with prostitutes and another mistress, Philomène Boudin. The poetry of his later years oscillates from the religious piety of Bonheur (“Happiness”; 1891) to the erotic frankness of Chansons pour elle (“Songs for Her”; 1891) and the occasional poetry of Dedicaces (“Dedications”; 1890).

It was during this final decade that Verlaine’s poetry began to find an audience in the English-speaking world. Young writers, such as George Moore (1852-1933) and Arthur Symons (1865-1945) started making pilgrimages to Paris to visit him. Moore claimed to have introduced English readers to Verlaine in “A Great Poet,” an article for his brother’s magazine, The Hawk, during February 1890. But others were quick to follow his lead and by 1891 Symons was profiling Verlaine in Black and White and the American journalist Edward Delille was writing about the French poet for the Fortnightly Review. The first English translations of Verlaine’s work date from this period too: Symons published “Tears in my Heart,” his version of “Il pleure dans mon Coeur,” in The Academy during July 1890 and John Gray’s “imitation” of the sonnet “Parsifal” appeared in The Dial during 1892.

As Verlaine’s name and work acquired purchase upon the British imagination, an air of prurient fascination persisted around his sexuality and criminal past. In December 1893, a character in a sketch in the satirical magazine Judy joked that his life and literary status were “rather a delicate subject” (p. 268). Still, Verlaine helped cement his relationship with a new English-speaking public in late 1893 by addressing them in person. At the instigation of the young artist, William Rothenstein (1872-1945), Verlaine travelled to London, Oxford and Salford, where he lectured on contemporary French poetry. He was hosted in London by Symons, who chaperoned the French poet to teas and dinners with publishers such as William Heinemann (1863-1920) and John Lane (1854-1925) and leading literary and artistic figures of the time, such as Edmund Gosse (1848-1929) and Herbert Horne (1864-1916). The visit attracted some coverage in the national press and Verlaine consequently published several poems and articles in the Fortnightly Review, Pall Mall Magazine, the New Review and the Senate during 1894 and 1895.

Rothenstein also acted as Verlaine’s agent when Charles Shannon (1863-1937) and Gleeson White (1851-1898) were planning their new annual, The Pageant. The French poet was initially commissioned to compose a poem responding to a painting by James McNeill Whistler but ended up writing a response to Dante Gabriele Rossetti’s Monna Rosa instead (for which he was paid 100 francs). Sadly, the poem did not appear in print until after Verlaine’s death in 1896.

Verlaine’s passing was widely reported in obituaries in the British press, but his reputation depended very much on the little magazines associated with the avant-garde, such as the Dial, the Pageant, and the Savoy. For the launch of The Savoy magazine in January 1896, for example, Arthur Symons included his own translation of Verlaine’s “Mandoline” from Fêtes Galantes, which was illustrated by Charles Conder. Several pages of the second issue in April of that year were devoted to remembering the poet after his death. This featured accounts of meeting Verlaine by Edmund Gosse (“At First Sight of Verlaine”) and W.B. Yeats (“Verlaine in 1894”), as well as Symons’ English translation of the poet’s own account of his visit to London only three years previously.

©2021, Matthew Creasy, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, School of Critical Studies, University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK.

Major Works by Paul Verlaine

- Poèmes saturniens. Paris: Alphonse Lemerre, 1866.

- Fêtes galantes. Paris: Alphonse Lemerre, 1869.

- La Bonne chanson. Paris: Alphonse Lemerre, 1870.

- Romances sans paroles. Sens: Maurice L’Hermitte, 1874.

- Sagesse. Paris: Société Générale de Librarie Catholique, 1880.

- Jadis et naguère. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1884.

- Parallèlement. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1889.

- Dédicaces. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1890.

- Bonheur. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1891.

- Chansons pour elle. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1891.

- Mes hôpitaux. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1891.

- Mes prisons. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1893.

- Confessions. Paris: Publications du ‘Fin de Siècle’, 1895.

- Invectives. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1896.

Selected Publications by Paul Verlaine in Anglophone Periodicals

- “Tears in my Heart,” trans. Arthur Symons, The Academy, 12 July, 1890, p.31.

- Gray, John. “Parsifal.” The Dial, vol. 2, 1892, p. 8. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/dialv2-gray-parsifal/

- “Visiteurs.” Hobby Horse, April 1893, pp. 41-2.

- “Retraite and Craintes.” Fortnightly Review, April 1894, pp. 557-58.

- “Anniversaire.” New Review, May 1894, p. 571.

- “Oxford.” Pall Mall Magazine, vol. 3, no. 17, May 1894, pp. 1-4.

- “Notes on England.” Fortnightly Review, July 1894, pp. 70-80.

- “Shakespeare and Racine.” Fortnightly Review, September 1894, pp. 440-47.

- “Conquistador.” Pall Mall Magazine, vol. 4, no. 19, November 1894, pp. 353-55.

- “A une femme.” New Review, March 1895, p. 259.

- “A Moi Amie & Epilogue.” Saturday Review, 29 June 189, p. 856.

- “A Eugénie.” New Review, June 1895, p. 676.

- “Iterum Crispina.” The Senate, September 1895, p. 332.

- “Arthur Rimbaud.” The Senate, October 1895, pp. 373-76.

- “Notes Respecting Alexandre Dumas the Younger.” Senate, January 1896, pp. 30-32.

- “Mandoline.” Translated by Arthur Symons. The Savoy, vol. 1 January 1896, pp. 42-43 Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-verlaine-mandoline/

- “Monna Rosa.” The Pageant. 1. (1896): 14-19.

- “My Visit to London.” The Savoy, vol. 2, April 1896, pp. 119-135. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv2-verlaine-london/

Works Cited and Selected Publications about Verlaine

- Anon. “M. Paul Verlaine.” Saturday Review, 5 December 1891, pp. 645-46.

- Anon. “Modern Men: Paul Verlaine.” National Observer, 12 December 1891, pp. 84-85.

- Anon. “Paul Verlaine.” Pall Mall Gazette, 22 November 1893, p. 4.

- Anon. “The Verlaine Course.” Judy, 6 December 1896, p. 269.

- Claes, Koenraad. The Late Victorian Little Magazine. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Creasy, Matthew. “‘Rather a delicate subject’: Verlaine, France and British Decadence.” Decadence: A Literary History, edited by Alex Murray, Cambridge University Press, 2020, pp. 65-86.

- Delille, Edward. “The Poet Verlaine.” Fortnightly Review, March 1891, pp. 394-403.

- Gosse, Edmund. “M. Paul Verlaine.” St James Gazette, 21 November, 1893, p. 2.

- Keary, C.F. “Paul Verlaine.” New Review, June 1897, pp. 617-30.

- Mackworth, Cecily. English Interludes: Mallarmé, Verlaine, Paul Valéry, Valéry Larbaud in England, 1860–1912. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1974.

- Moore. George. “A Great Poet.” The Hawk, 25 February, 1890, pp. 223-24.

- Murray, Alex. “Decadent Conservatism: Politics and Aesthetics in The Senate,” Journal of Victorian Culture, vol. 20, no. 2, 2015, pp. 186-211.

- Richardson, Joanne, Verlaine. Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1971.

- Scott, Clive. “The Liberated Verse of the English Translators of French Symbolism,”’ The Symbolist Movement in the Literature of European Languages, edited by Anna Balakian John Benjamins, 1982, pp.127-43.

- Stephan, Philip. Paul Verlaine and the Decadence 1880-1892. Manchester University Press, 1974.

- Radford, Andrew, and Victoria Reid, editors. Channel Packets: Franco-British Cultural Exchanges, 1880-1940. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Starkie, Enid. From Gautier to Eliot: The Influence of France on English Literature 1851-1939. Hutchinson, 1960.

- Symons, Arthur. “Paul Verlaine.” Black and White, 20 June 1891, pp. 649-50.

- –. “Paul Verlaine.” New Review, 19. June, 1892, pp. 501-15.

- –. “The Decadent Movement in Literature.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, vol. 87, November 1893, pp. 858-67.

- –. “A Literary Causerie: On the ‘Invectives’ of Verlaine.” The Savoy vol. 7, November 1896, pp. 88-90. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv7-symons-causerie/

MLA citation:

Creasy, Matthew. “Paul Verlaine (1844-1896),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/verlaine_bio/