The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume VI July 1895

Contents

Literature

I. The Next Time . . By Henry

James . . Page 11

II. Earth’s Complines . . Charles

G.D. Roberts . 60

III. Tirala-tirala

. . . Henry Harland . . 65

IV. The Golden Touch . Rosamund

Marriott Watson 77

V. Long Odds

. . . Kenneth Grahame . . 78

VI. A Letter Home . . Enoch Arnold

Bennett . 93

VII. The Captain’s Book

. George Egerton . . 103

VIII. A Song . . . . Dollie Radford

. . . 121

IX. A New Poster . . Evelyn Sharp . . . 123

X. An Appreciation of Ouida G.S. Street . . . 167

XI. Justice . . . . Richard Garnett, LL.D.,

C.B. . . . . 177

XII. Lilla . . . . Prince Bojidar Karageorgevitch . . . . 178

XIII.

In an American Newspaper office Charles Miner Thompson 187

XIV. A Madrigal . . . Olive

Custance . . 215

XV. The Dead Wall

. . H.B. Marriott Watson . 221

XVL. Mars . . . . Rose Haig Thomas

. . 249

XVII. The Auction Room of Letters Arthur Waugh . . 257

XVIII. The Crimson Weaver . R. Murray

Gilchrist . 269

XIX. The Digger

. . . Edgar Prestage . . 283

XX. A Pen-and-ink Effect . Frances

E. Huntley . . 286

XXI. Consolation

. . . J.A. Blaikie . . . 295

XXII. A Beautiful Accident . Stanley

V. Makower . 297

XXIII. Four Prose

Fancies . Richard Le Gallienne . 307

XXIV. Two Letters to a Friend . Theodore Watts . . 333

Art

The Yellow Book — Vol. VI. — July, 1895

Art

Front Cover, by Patten Wilson

Title Page, by Patten Wilson

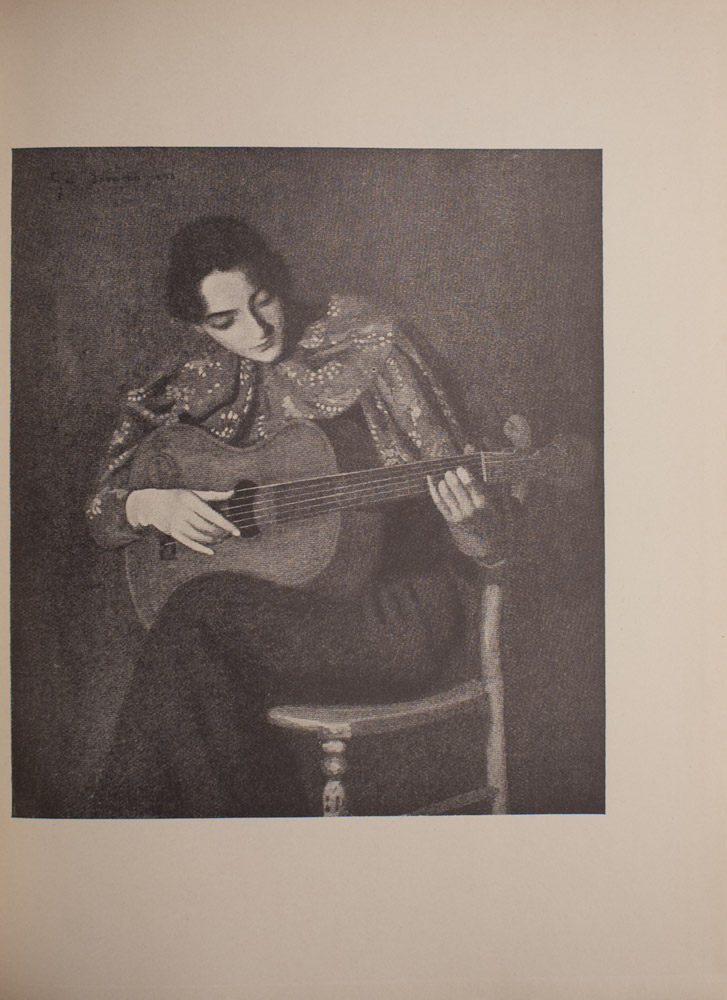

I. The Guitar Player . . By

George Thomson . . Page 7

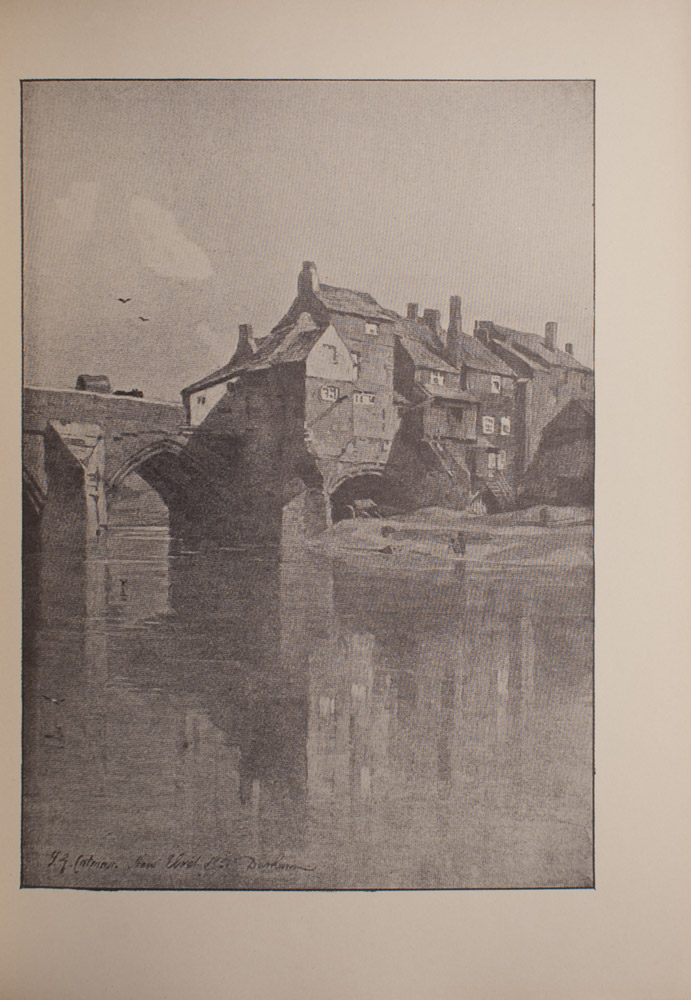

II. Durham . . . . F.G. Cotman

. . 62

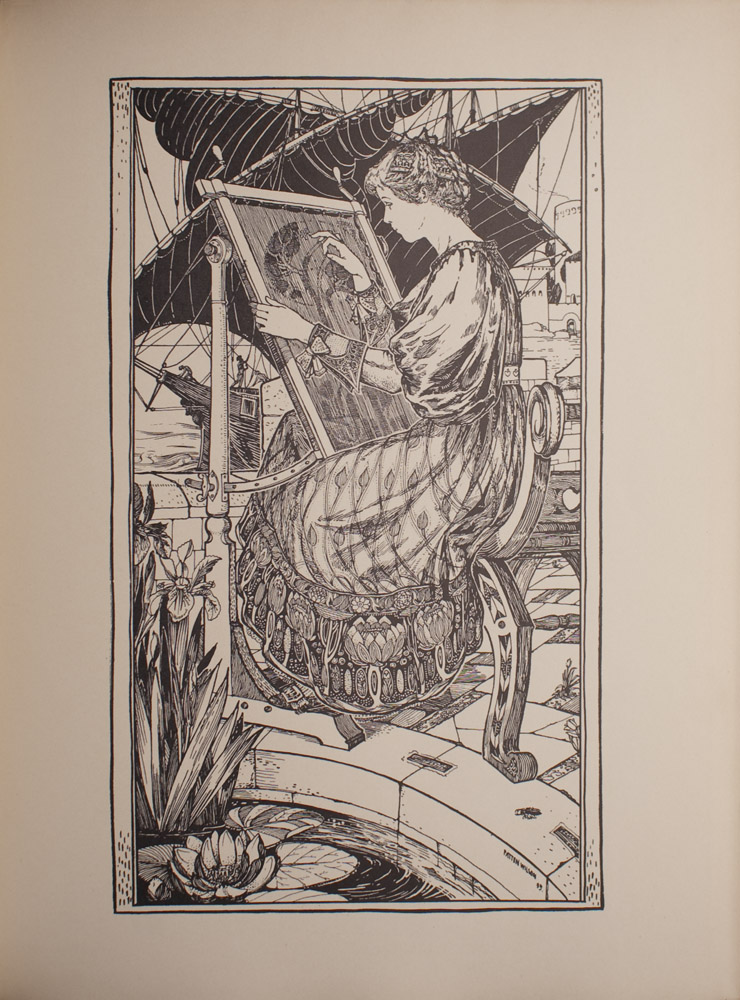

III. A Penelope . .Patten Wilson . . 87

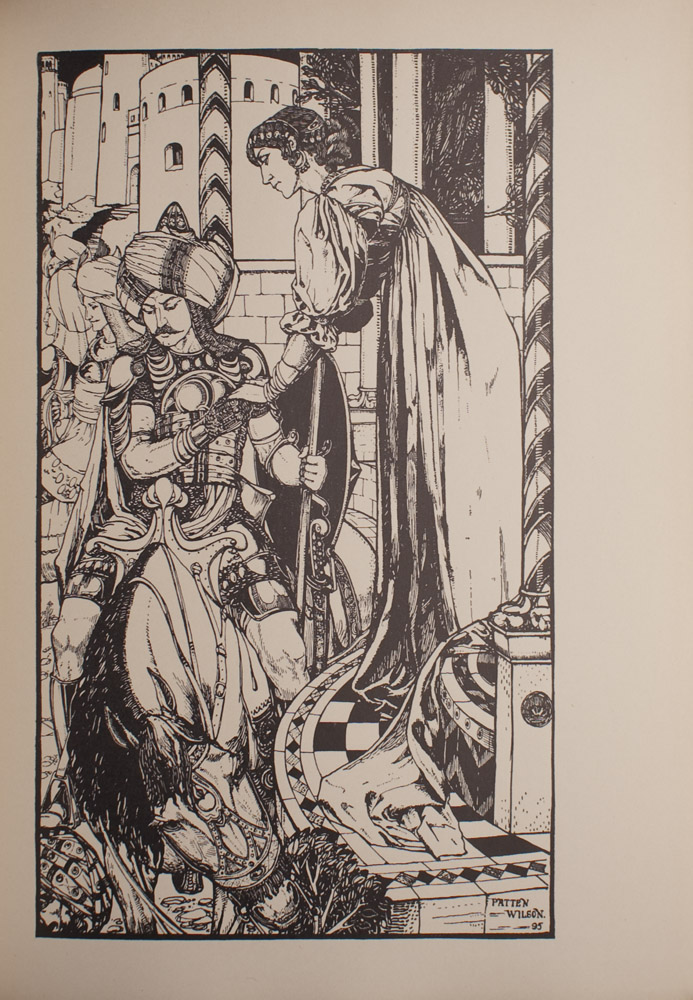

IV. Sohrab Taking Leave of his Mother . .

V. The Yellow Book . . Gertrude

D. Hammond . 117

VI. Star and Garter,

Richmond P. Wilson Steer . . 164

VII. The Screen . . . Sir William

Eden, Bart. . 183

VIII. Padstow .

. . . Gertrude Prideaux-Brune 217

IX. Souvenir de Paris . . Charles

Conder . . 253

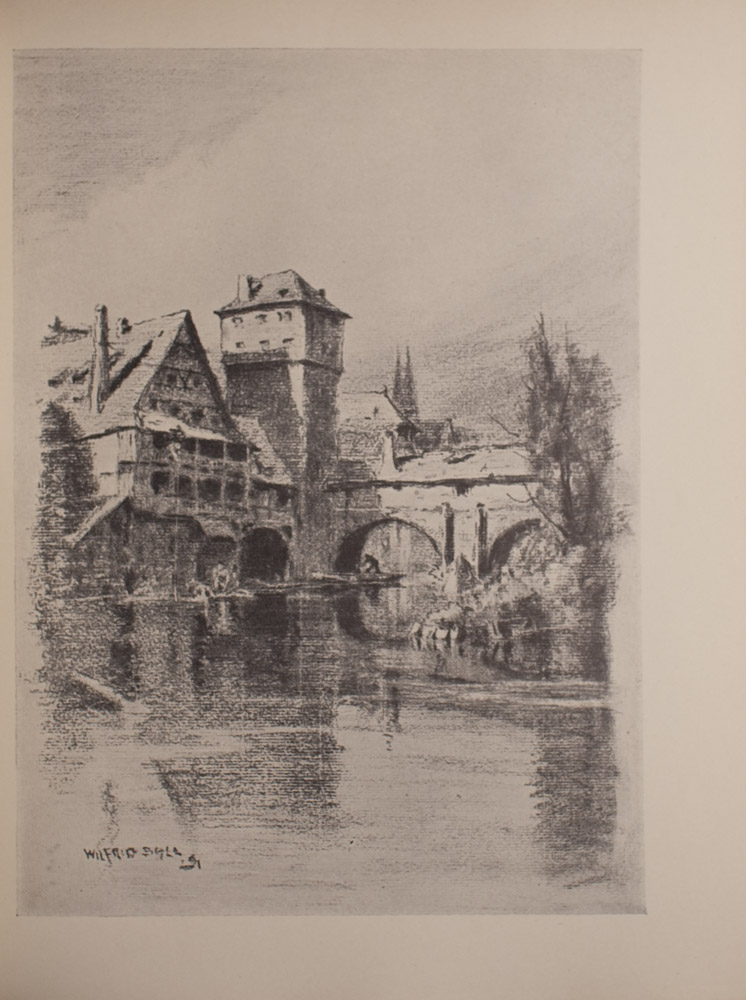

X. Wasser-Thurm,

Nürnberg Wilfred Ball . . . 266

XI. The Mirror . .Fred Hyland

. . . 278

XII. Keynotes . .

XIII. Trees . . . . Alfred

Thornton . . 292

XIV. Gossips .

. . . A.S. Hartrick . . . 303

XV. Going to Church .William

Strang . . 327

XVI. A Study . .

.

Back Cover, by Patten Wilson

Advertisements

The half-tone Reproductions in this Volume are

by the Swan Electric Engraving Company.

The Editor of THE YELLOW BOOK can in no case

hold himself responsible for rejected manuscripts ;

when, however, they are accompanied by stamped

addressed envelopes, every effort will be made to

secure their prompt return. Manuscripts arriving un-

accompanied by stamped addressed envelopes will be neither

read nor returned.

The Next Time

By Henry James

MRS. HIGHMORE’S errand this morning was odd enough to

deserve commemoration

: she came to ask me to write a

notice of her great forthcoming work. Her

great works have

come forth so frequently without my assistance that I

was

sufficiently entitled, on this occasion, to open my eyes ; but

what

really made me stare was the ground on which her request reposed,

and what leads me to record the incident is the train of memory

lighted by

that explanation. Poor Ray Limbert, while we talked,

seemed to sit there

between us : she reminded me that my acquaint-

ance with him had begun,

eighteen years ago, with her having

come in precisely as she came in this

morning to bespeak my

consideration for him. If she didn’t know then how

little my

consideration was worth she is at least enlightened about its

value

to-day, and it is just in that knowledge that the drollery of

her

visit resides. As I hold up the torch to the dusky years—by

which

I mean as I cipher up with a pen that stumbles and stops the

figured column of my reminiscences—I see that Limbert’s public

hour,

or at least my small apprehension of it, is rounded by those

two occasions.

It was finis with a little moralising flourish,

that

Mrs. Highmore seemed to trace to-day at the bottom of the page.

”

One of the most voluminous writers of the time,” she has often

repeated

repeated this sign ; but never, I dare say, in spite of her professional

command of appropriate emotion, with an equal sense of that

mystery and

that sadness of things which, to people of imagination,

generally hover

over the close of human histories. This romance

at any rate is bracketed by

her early and her late appeal ; and

when its melancholy protrusions had

caught the declining light

again from my half-hour’s talk with her, I took

a private vow to re-

cover, while that light still lingers, something of

the delicate flush,

to pick out, with a brief patience, the perplexing

lesson.

It was wonderful to observe how, for herself, Mrs. Highmore

had already done

so : she wouldn’t have hesitated to announce to

me what was the matter with

Ralph Limbert, or at all events to

give me a glimpse of the high admonition

she had read in his

career. There could have been no better proof of the

vividness of

this parable, which we were really in our pleasant sympathy

quite

at one about, than that Mrs. Highmore, of all hardened sinners,

should have been converted. This indeed was not news to me :

she impressed

upon me that for the last ten years she had wanted

to do something

artistic, something as to which she was prepared

not to care a rap whether

or no it should sell. She brought home

to me further that it had been

mainly seeing what her brother-in-

law did, and how he did it, that had

wedded her to this perversity.

As he didn’t

sell, dear soul, and as several persons, of whom I was

one, thought ever so

much of him for it, the fancy had taken her—

taken her even quite

early in her prolific—course of reaching, if

only once, the same

heroic eminence. She yearned to be, like

Limbert, but of course only once,

an exquisite failure. There

was something a failure was, a failure in the

market, that a success

somehow wasn’t. A success was as prosaic as a good

dinner : there

was nothing more to be said about it than that you had had

it.

Who but vulgar people, in such a case, made gloating remarks

about

about the courses ? It was by such vulgar people, often, that a

success was

attested. It made, if you came to look at it, nothing

but money ; that is

it made so much that any other result showed

small in comparison. A

failure, now, could make—oh, with the

aid of immense talent of

course, for there were failures and failures

—such a reputation !

She did me the honour—she had often done

it—to intimate that

what she meant by reputation was seeing me

toss

a flower. If it took a failure to catch a failure I was by my

own admission

well qualified to place the laurel. It was because

she had made so much

money and Mr. Highmore had taken such

care of it that she could treat

herself to an hour of pure glory.

She perfectly remembered that as often as

I had heard her heave

that sigh I had been prompt with my declaration that

a book sold

might easily be as glorious as a book unsold. Of course she

knew

that, but she knew also that it was an age of flourishing rubbish

and that she had never heard me speak of anything that had ” done

well ”

exactly as she had sometimes heard me speak of something

that

hadn’t—with just two or three words of respect which, when

I used

them, seemed to convey more than they commonly stood

for, seemed to hush up

the discussion a little, as if for the very

beauty of the secret.

I may declare in regard to these allusions that, whatever I then

thought of

myself as a holder of the scales, I had never scrupled to

laugh out at the

humour of Mrs. Highmore’s pursuit of quality at

any price. It had never

rescued her, even for a day, from the hard

doom of popularity, and, though

I never gave her my word for it,

there was no reason at all why it should.

The public would

have her, as her husband used

roguishly to remark ; not indeed

that, making her bargains, standing up to

her publishers and even,

in his higher flights, to her reviewers, he ever

had a glimpse of her

attempted conspiracy against her genius, or rather, as

I may say,

against

against mine. It was not that when she tried to be what she

called subtle

(for wasn’t Limbert subtle, and wasn’t I ?) her fond

consumers, bless them,

didn’t suspect the trick nor show what

they thought of it : they

straightway rose, on the contrary, to the

morsel she had hoped to hold too

high, and, making but a big,

cheerful bite of it, wagged their great

collective tail artlessly for

more. It was not given to her not to please,

nor granted even to

her best refinements to affright. I have always

respected the

mystery of those humiliations, but I was fully aware this

morning

that they were practically the reason why she had come to me.

Therefore when she said, with the flush of a bold joke in her kind,

coarse

face, ” What I feel is, you know, that you could

settle me if

you only would,” I knew quite well what she meant. She

meant

that of old it had always appeared to be the fine blade, as some

one had hyperbolically called it, of my particular opinion that

snapped the

silken thread by which Limbert’s chance in the market

was wont to hang. She

meant that my favour was compromising,

that my praise indeed was fatal. I

had made myself a little specialty

of seeing nothing in certain

celebrities, of seeing overmuch in an

occasional nobody, and of judging

from a point of view that, say

what I would for it (and I had a monstrous

deal to say) remained

perverse and obscure. Mine was in short the love that

killed, for

my subtlety, unlike Mrs. Highmore’s, produced no tremor of

the

public tail. She had not forgotten how, toward the end, when his

case was worst, Limbert would absolutely come to me with a funny,

shy

pathos in his eyes and say : ” My dear fellow, I think I’ve done

it this

time if you’ll only keep quiet.” If my keeping quiet, in

those days, was to

help him to appear to have hit the usual taste, for

the want of which he

was starving, so now my breaking out was to

help Mrs. Highmore to appear to

have hit the unusual.

The moral of all this was that I had frightened the public too

much

much for our late friend, but that as she was not starving this was

exactly

what her grosser reputation required. And then, she

good-naturedly and

delicately intimated, there would always be, if

further reasons were

wanting, the price of my clever little article.

I think she gave that hint

with a flattering impression—spoiled

child of the booksellers as she

is—that the price of my clever little

articles is high. Whatever it

is, at any rate, she had evidently

reflected that poor Limbert’s anxiety

for his own profit used to

involve my sacrificing mine. Any inconvenience

that my obliging

her might entail would not, in fine, be pecuniary. Her

appeal, her

motive, her fantastic thirst for quality and her ingenious

theory of

my influence struck me all as excellent comedy, and as I

con-

sented, contingently, to oblige her (I could plead no

inconvenience)

she left me the sheets of her new novel. I have been

looking

them over, but I am frankly appalled at what she expects of

me.

What is she thinking of, poor dear, and what has put it into her

head that ” quality ” has descended upon her ? Why does she

suppose that

she has been ” artistic ” ? She hasn’t been anything

whatever, I surmise,

that she has not inveterately been. What

does she imagine she has left out

? What does she conceive she

has put in ? She has neither left out nor put

in anything. I shall

have to write her an embarrassed note. The book

doesn’t exist,

and there’s nothing in life to say about it. How can there

be any-

thing but the same old faithful rush for it ?

I

This rush had already begun when, early in the seventies, in the

interest of

her prospective brother-in-law, she approached me on

the singular ground of

the unencouraged sentiment I had enter-

tained

tained for her sister. Pretty pink Maud had cast me out, but I appear

to

have passed in the flurried little circle for a magnanimous youth.

Pretty

pink Maud, so lovely then, before her troubles, that dusky

Jane was

gratefully conscious of all she made up for, Maud Stannace,

very literary

too, very languishing and extremely bullied by her

mother, had yielded,

invidiously, as it might have struck me, to

Ray Limbert’s suit, which Mrs.

Stannace was not the woman to

stomach. Mrs. Stannace was never the woman to

do anything :

she had been shocked at the way her children, with the grubby

taint

of their father’s blood (he had published pale Remains or flat

Con-

versations of his father) breathed the

alien air of authorship. If not

the daughter, nor even the niece, she was,

if I am not mistaken, the

second cousin of a hundred earls, and a great

stickler for relationship,

so that she had other views for her brilliant

child, especially after her

quiet one (such had been her original discreet

forecast of the pro-

ducer of eighty volumes) became the second wife of an

ex-army-

surgeon, already the father of four children. Mrs. Stannace

had

too manifestly dreamed it would be given to pretty pink Maud to

detach some one of the hundred (he wouldn’t be missed) from the

cluster. It

was because she cared only for cousins that I unlearnt the

way to her

house, which she had once reminded me was one of the

few paths of gentility

indulgently open to me. Ralph Limbert,

who belonged to nobody and had done

nothing—nothing even at

Cambridge—had only the uncanny spell

he had cast upon her

younger daughter to recommend him ; but if her

younger

daughter had a spark of filial feeling she wouldn’t commit the

in-

decency of deserting for his sake a deeply dependent and intensely

aggravated mother.

These things I learned from Jane Highmore, who, as if her

books had been

babies (they remained her only ones) had waited till

after marriage to show

what she could do, and now bade fair to

surround

surround her satisfied spouse (he took, for some mysterious reason,

a part

of the credit) with a little family, in sets of triplets, which,

properly

handled, would be the support of his declining years.

The young couple,

neither of whom had a penny, were now virtu-

ally engaged : the thing was

subject to Ralph’s putting his hand

on some regular employment. People more

enamoured couldn’t

be conceived, and Mrs. Highmore, honest woman, who had

more-

over a professional sense for a love-story, was eager to take them

under her wing. What was wanted was a decent opening for

Limbert,

which it had occurred to her I might assist her to find,

though indeed I

had not yet found any such matter for myself.

But it was well known that I

was too particular, whereas poor

Ralph, with the easy manners of genius,

was ready to accept

almost anything to which a salary, even a small one,

was attached.

If he could only get a place on a newspaper, for instance,

the rest

of his maintenance would come freely enough. It was true that

his two novels, one of which she had brought to leave with me,

had passed

unperceived, and that to her, Mrs. Highmore person-

ally, they didn’t

irresistibly appeal ; but she could none the less

assure me that I should

have only to spend ten minutes with him

(and our encounter must speedily

take place) to receive an impres-

sion of latent power.

Our encounter took place soon after I had read the volumes

Mrs. Highmore had

left with me, in which I recognised an inten-

tion of a sort that I had now

pretty well given up the hope of

meeting. I daresay that, without knowing

it, I had been looking

out rather hungrily for an altar of sacrifice : at

any rate, when I

came across Ralph Limbert I submitted to one of the rarest

emo-

tions of my literary life, the sense of an activity in which I

could

critically rest. The rest was deep and salutary, and it has not

been disturbed to this hour. It has been a long, large surrender,

the

the luxury of dropped discriminations. He couldn’t trouble me,

whatever he

did, for I practically enjoyed him as much when he

was worse as when he was

better. It was a case, I suppose, of

natural prearrangement, in which, I

hasten to add, I keep excellent

company. We are a numerous band, partakers

of the same repose,

who sit together in the shade of the tree, by the plash

of the

fountain, with the glare of the desert around us and no great

vice

that I know of but the habit perhaps of estimating people a

little

too much by what they think of a certain style. If it had been

laid upon these few pages, however, to be the history of an

enthusiasm, I

should not have undertaken them : they are con-

cerned with Ralph Limbert

in relations to which I was a stranger,

or in which I participated only by

sympathy. I used to talk about

his work, but I seldom talk now : the

brotherhood of the faith

have become, like the Trappists, a silent order.

If to the day of

his death, after mortal disenchantments, the impression he

first

produced always evoked the word ” ingenuous, ” those to whom

his

face was familiar can easily imagine what it must have been

when it still

had the light of youth. I have never seen a man of

genius look so passive,

a man of experience so off his guard. At

the period I made his acquaintance

this freshness was all un-

brushed. His foot had begun to stumble, but he

was full of big

intentions and of sweet Maud Stannace. Black-haired and

pale,

deceptively languid, he had the eyes of a clever child and the

voice of a bronze bell. He saw more even than I had done in

the girl he was

engaged to ; as time went on I became conscious

that we had both, properly

enough, seen rather more than there was.

Our odd situation, that of the

three of us, became perfectly possible

from the moment I observed that he

had more patience with

her than I should have had. I was happy at not

having to supply

this quantity, and she, on her side, found pleasure in

being able

to

to be impertinent to me without incurring the reproach of a

bad

wife.

Limbert’s novels appeared to have brought him no money; they

had only

brought him, so far as I could then make out, tributes

that took up his

time. These indeed brought him, from several

quarters, some other things,

and on my part, at the end of three

months, The

Blackport Beacon. I don’t to-day remember how I

obtained for him

the London correspondence of the great northern

organ, unless it was

through somebody’s having obtained it for

myself. I seem to recall that I

got rid of it in Limbert’s interest,

persuaded the editor that he was much

the better man. The better

man was naturally the man who had pledged

himself to support a

charming wife. We were neither of us good, as the

event proved,

but he had a rarer kind of badness. The

Blackport Beacon had two

London correspondents—one a

supposed haunter of political circles,

the other a votary of questions

sketchily classified as literary.

They were both expected to be lively, and

what was held out to

each was that it was honourably open to him to be

livelier than the

other. I recollect the political correspondent of that

period, and

that what it was reducible to was that Ray Limbert was to try

to

be livelier than Pat Moyle. He had not yet seemed to me so can-

did

as when he undertook this exploit, which brought matters to a

head with

Mrs. Stannace, inasmuch as her opposition to the marriage

now logically

fell to the ground. It’s all tears and laughter as I

look back upon that

admirable time, in which nothing was so

romantic as our intense vision of

the real. No fool’s paradise

ever rustled such a cradle-song. It was

anything but Bohemia

—it was the very temple of Mrs. Grundy. We knew

we

were too critical, and that made us sublimely indulgent; we

believed we did our duty, or wanted to, and that made us free to

dream. But

we dreamed over the multiplication-table ; we were

nothing

The Yellow Book—Vol. VI. B

nothing if not practical. Oh, the long smokes and sudden ideas,

the knowing

hints and banished scruples ! The great thing was

for Limbert to bring out

his next book, which was just what his

delightful engagement with the Beacon would give him leisure and

liberty to do.

The kind of work, all human and elastic and sug-

gestive, was capital

experience : in picking up things for his

bi-weekly letter he would pick up

life as well, he would pick up

literature. The new publications, the new

pictures, the new

people—there would be nothing too novel for us and

nobody

too sacred. We introduced everything and everybody into Mrs.

Stannace’s drawing-room, of which I again became a familiar.

Mrs. Stannace, it was true, thought herself in strange company ;

she didn’t

particularly mind the new books, though some of them

seemed queer enough,

but to the new people she had decided

objections. It was notorious,

however, that poor Lady Robeck

secretly wrote for one of the papers, and

the thing had certainly,

in its glance at the doings of the great world, a

side that might be

made attractive. But we were going to make every side

attractive,

and we had everything to say about the kind of thing a paper

like

the Beacon would want. To give it what it

would want and

to give it nothing else was not doubtless an inspiring, but

it was

a perfectly respectable task, especially for a man with an

appealing

bride and a contentious mother-in-law. I thought Limbert’s

first

letters as charming as the genre allowed,

though I won’t deny

that in spite of my sense of the importance of

concessions I was

just a trifle disconcerted at the way he had caught the

tone. The

tone was of course to be caught, but need it have been caught

so

in the act ? The creature was even cleverer, as Maud Stannace

said,

than she had ventured to hope. Verily it was a good thing

to have a dose of

the wisdom of the serpent. If it had to be

journalism—well, it was journalism. If he had to be ” chatty

“—

well,

well, he was chatty. Now and then he made a hit

that—it was

stupid of me—brought the blood to my face. I

hated him to be

so personal ; but still, if it would make his

fortune— ! It

wouldn’t of course directly, but the book would,

practically and

in the sense to which our pure ideas of fortune were

confined ; and

these things were all for the book. The daily balm

meanwhile

was in what one knew of the book—there were exquisite

things

to know ; in the quiet monthly cheques from Blackport and in

the deeper rose of Maud’s little preparations, which were as dainty,

on

their tiny scale, as if she had been a humming-bird building a

nest. When

at the end of three months her betrothed had fairly

settled down to his

correspondence—in which Mrs. Highmore

was the only person, so far as

we could discover, disappointed,

even she moreover being in this particular

tortuous and possibly

jealous; when the situation had assumed such a

comfortable

shape it was quite time to prepare. I published at that

moment

my first volume, mere faded ink to-day, a little collection of

literary impressions, odds and ends of criticism contributed to a

journal

less remunerative but also less chatty than the Beacon,

small ironies and ecstasies, great phrases and mistakes

; and the very

week it came out poor Limbert devoted half of one of his

letters

to it, with the happy sense, this time, of gratifying both

himself

and me as well as the Blackport breakfast tables. I remember

his

saying it wasn’t literature, the stuff, superficial stuff, he had

to

write about me ; but what did that matter if it came back, as we

knew, to the making for literature in the roundabout way ? I

sold the

thing, I remember, for ten pounds, and with the money I

bought in Vigo

Street a quaint piece of old silver for Maud

Stannace, which I carried to

her with my own hand as a wedding-

gift. In her mother’s small

drawing-room, a faded bower of photo-

graphy, fenced in and bedimmed by

folding screens out of which

sallow

sallow persons of fashion, with dashing signatures, looked at you

from

retouched eyes and little windows of plush, I was left to wait

long enough

to feel in the air of the house a hushed vibration

of disaster. When our

young lady came in she was very pale,

and her eyes too had been

retouched.

” Something horrid has happened,” I immediately said; and

having really, all

along, but half believed in her mother’s meagre

permission, I risked with

an unguarded groan the introduction of

Mrs. Stannace’s name.

” Yes, she has made a dreadful scene ; she insists on our putting

it off

again. We’re very unhappy : poor Ray has been turned

off.” Her tears began

to flow again.

I had such a good conscience that I stared. ” Turned off

what ?”

” Why, his paper of course. The Beacon has given him

what

he calls the sack. They don’t like his letters—they’re not

the

sort of thing they want.”

My blankness could only deepen. ” Then what sort of thing

do they want ?”

” Something more chatty.”

” More ?” I cried, aghast.

” More gossipy, more personal. They want ‘journalism.’

They want tremendous

trash.”

” Why, that’s just what his letters have been ! ” I

broke out.

This was strong, and I caught myself up, but the girl offered

me the pardon

of a beautiful wan smile. ” So Ray himself

declares. He says he has stooped

so low.”

” Very well—he must stoop lower. He must keep

the place.”

” He can’t ! ” poor Maud wailed. ” He says he has tried all he

knows, has

been abject, has gone on all fours, and that if they

don’t like

that——”

“He

” He accepts his dismissal ?” I demanded in dismay.

She gave a tragic shrug. ” What other course is open to him ?

He wrote to

them that such work as he has done is the very worst

he can do for the

money.”

” Then,” I inquired, with a flash of hope, ” they’ll offer him

more for

worse ?”

” No, indeed,” she answered, ” they haven’t even offered him

to go on at a

reduction. He isn’t funny enough.”

I reflected a moment. ” But surely such a thing as his notice

of my

book—— !”

” It was your wretched book that was the last straw ! He should

have treated

it superficially.”

” Well, if he didn’t——! ” I began. But then I checked myself.

” Je vous porte malheur.“

She didn’t deny this ; she only went on : ” What on earth is he

to

do?”

” He’s to do better than the monkeys ! He’s to write !”

” But what on earth are we to marry on ?”

I considered once more. ” You’re to marry on The Major

Key.”

II

The Major Key was the new novel, and the great thing

there-

fore was to finish it ; a consummation for which three months

of

the Beacon had in some degree prepared the

way. The action of

that journal was indeed a shock, but I didn’t know then

the worst,

didn’t know that in addition to being a shock it was also a

symptom. It was the first hint of the difficulty to which poor

Limbert was

eventually to succumb. His state was the happier,

however, for his not

immediately seeing all that it meant. Diffi-

culty

culty was the law of life, but one could thank heaven it was excep-

tionally

present in that horrid quarter. There was the difficulty

that inspired, the

difficulty of The Major Key to wit, which it

was, after all, base to sacrifice to the turning of somersaults for

pennies. These convictions Ray Limbert beguiled his fresh wait

by blandly

entertaining : not indeed, I think, that the failure of

his attempt to be

chatty didn’t leave him slightly humiliated. If

it was bad enough to have

grinned through a horse-collar, it was

very bad indeed to have grinned in

vain. Well, he would try no

more grinning, or at least no more

horse-collars. The only success

worth one’s powder was success in the line

of one’s idiosyncrasy.

Consistency was in itself distinction, and what was

talent but the art

of being completely whatever it was that one happened to

be ? One’s

things were characteristic or they were nothing. I look back

rather

fondly on our having exchanged in those days these admirable

re-

marks and many others ; on our having been very happy too, in

spite

of postponements and obscurities, in spite also of such

occasional

hauntings as could spring from our lurid glimpse of the fact

that

even twaddle cunningly calculated was above some people’s heads.

It was easy to wave away spectres by the reflection that all one

had to do

was not to write for those people ; and it was certainly

not for them that

Limbert wrote while he hammered at The

Major Key. The taint of literature was fatal only in

a certain

kind of air, which was precisely the kind against which we

had

now closed our window. Mrs. Stannace rose from her crumpled

cushions as soon as she had obtained an adjournment, and Maud

looked pale

and proud, quite victorious and superior, at her having

obtained nothing

more. Maud behaved well, I thought, to her

mother, and well indeed, for a

girl who had mainly been taught

to be flowerlike, to every one. What she

gave Ray Limbert her

fine, abundant needs made him, then and ever, pay for

; but the

gift

gift was liberal, almost wonderful—an assertion I make even while

remembering to how many clever women, early and late, his work

had been

dear. It was not only that the woman he was to marry

was in love with him,

but that (this was the strangeness) she had

really seen almost better than

any one what he could do. The

greatest strangeness was that she didn’t want

him to do something

different. This boundless belief was, indeed, the main

way of her

devotion ; and, as an act of faith, it naturally asked for

miracles.

She was a rare wife for a poet, if she was not perhaps the

best

who could have been picked out for a poor man.

Well, we were to have the miracles at all events, and we were

in a perfect

state of mind to receive them. There were more of

us every day, and we

thought highly even of our friend’s odd jobs

and pot-boilers. The Beacon had had no successor, but he found

some

quiet corners and stray chances. Perpetually poking the fire

and looking

out of the window, he was certainly not a monster of

facility, but he was,

thanks perhaps to a certain method in that

madness, a monster of certainty.

It wasn’t every one, however,

who knew him for this : many editors printed

him but once. He

was getting a small reputation as a man it was well to

have the

first time : he created obscure apprehensions as to what

might

happen the second. He was good for making an impression, but

no

one seemed exactly to know what the impression was good

for when made. The

reason was simply that they had not seen

yet The Major

Key, that fiery-hearted rose as to which we

watched in private

the formation of petal after petal. Nothing

mattered but that, for it had

already elicited a splendid bid, much

talked about in Mrs. Highmore’s

drawing-room, where, at this

point my reminiscences grow particularly

thick. Her roses

bloomed all the year, and her

sociability increased with her row of

prizes. We had an idea that we ” met

every one ” there—so we

naturally

naturally thought when we met each other. Between our hostess

and Ray

Limbert flourished the happiest relation, the only cloud

on which was that

her husband eyed him rather askance. When

he was called clever this

personage wanted to know what he had

to “show”; and it was certain that he

had nothing that could

compare with Jane Highmore. Mr. Highmore took his

stand on

accomplished work and, turning up his coat-tails, warmed his

rear

with a good conscience at the neat bookcase in which the genera-

tions of triplets were chronologically arranged. The harmony

between his

companions rested on the fact that, as I have already

hinted, each would

have liked so much to be the other. Limbert

couldn’t but have a feeling

about a woman who, in addition to

being the best creature and her sister’s

backer, would have made,

could she have condescended, such a success with

the Beacon.

On the other hand, Mrs. Highmore

used freely to say : ” Do

you know, he’ll do exactly the thing that I want to do ? I shall

never do it myself, but

he’ll do it instead. Yes, he’ll do my thing,

and I shall hate him for

it—the wretch.” Hating him was her

pleasant humour, for the wretch

was personally to her taste.

She prevailed on her own publisher to promise to take The

Major Key and to engage to pay a considerable sum

down, as

the phrase is, on the presumption of its attracting attention.

This

was good news for the evening’s end at Mrs. Highmore’s, when

there were only four or five left and cigarettes ran low ; but there

was

better news to come, and I have never forgotten how, as it

was I who had

the good fortune to bring it, I kept it back on one

of those occasions, for

the sake of my effect, till only the right

people remained. The right

people were now more and more

numerous, but this was a revelation addressed

only to a choice

residuum—a residuum including of course Limbert

himself, with

whom I haggled for another cigarette before I announced that

as

a consequence

a consequence of an interview I had had with him that afternoon,

and of a

subtle argument I had brought to bear, Mrs. Highmore’s

pearl of publishers

had agreed to put forth the new book as a

serial. He was to ” run ” it in

his magazine, and he was to pay

ever so much more for the privilege. I

produced a fine gasp

which presently found a more articulate relief, but

poor Limbert’s

voice failed him once for all (he knew he was to walk away

with

me) and it was some one else who asked me in what my subtle

argument had resided. I forget what florid description I then

gave of it :

to-day I have no reason not to confess that it had

resided in the simple

plea that the book was exquisite. I had said :

” Come, my dear friend, be

original ; just risk it for that !” My

dear friend seemed to rise to the

chance, and I followed up my

advantage, permitting him honestly no illusion

as to the quality

of the work. He clutched interrogatively at two or

three

attenuations, but I dashed them aside, leaving him face to face

with the formidable truth. It was just a pure gem : was he the

man not to

flinch ? His danger appeared to have acted upon

him as the anaconda acts

upon the rabbit ; fascinated and paralysed,

he had been engulfed in the

long pink throat. When, a week

before, at my request, Limbert had let me

possess for a day the

complete manuscript, beautifully copied out by Maud

Stannace,

I had flushed with indignation at its having to be said of the

author

of such pages that he hadn’t the common means to marry. I had

taken the field, in a great glow, to repair this scandal, and it was

therefore quite directly my fault if, three months later, when

The Major Key began to run, Mrs. Stannace was driven

to the

wall. She had made a condition of a fixed income ; and at last

a fixed income was achieved.

She had to recognise it, and after much prostration among the

photographs

she recognised it to the extent of accepting some of

the

the convenience of it in the form of a project for a common

household, to

the expenses of which each party should propor-

tionately contribute. Jane

Highmore made a great point of

her not being left alone, but Mrs. Stannace

herself determined

the proportion, which, on Limbert’s side at least, and

in spite

of many other fluctuations, was never altered. His income had

been ” fixed ” with a vengeance: having painfully stooped to

the

comprehension of it, Mrs. Stannace rested on this effort

to the end and

asked no further questions on the subject.

The Major Key, in other words, ran ever so long, and

before

it was half out Limbert and Maud had been married and the

common household set up. These first months were probably

the happiest in

the family annals, with wedding-bells and

budding laurels, the quiet,

assured course of the book and the

friendly, familiar note, round the

corner, of Mrs. Highmore’s big

guns. They gave Ralph time to block in

another picture, as

well as to let me know, after a while, that he had the

happ

y prospect of becoming a father. We had some dispute, at times, as

to whether The Major Key was making an impression,

but our

contention could only be futile so long as we were not agreed

as

to what an impression consisted of. Several persons wrote to the

author, and several others asked to be introduced to him : wasn’t

that an

impression? One of the lively ” weeklies, ” snapping

at the deadly ”

monthlies,” said the whole thing was “grossly

inartistic “—wasn’t

that ? It was somewhere else proclaimed ” a

wonderfully subtle

character-study “—wasn’t that too ? The

strongest effect doubtless

was produced on the publisher when, in

its lemon-coloured volumes, like a

little dish of three custards, the

book was at last served cold : he never

got his money back and,

as far as I know, has never got it back to this

day. The Major Key

was rather a great

performance than a great success. It con-

verted

verted readers into friends and friends into lovers ; it placed the

author,

as the phrase is—placed him all too definitely ; but it

shrank to

obscurity in the account of sales eventually rendered.

It was in short an

exquisite thing, but it was scarcely a thing

to have published, and

certainly not a thing to have married on.

I heard all about the matter, for

my intervention had much ex-

posed me. Mrs. Highmore said the second volume

had given her

ideas, and the ideas are probably to be found in some of her

works,

to the circulation of which they have even perhaps contributed.

This was not absolutely yet the very thing she wanted to do, but

it was on

the way to it. So much, she informed me, she par-

ticularly perceived in

the light of a critical study which I put forth

in a little magazine ;

which the publisher, in his advertisements,

quoted from profusely ; and as

to which there sprang up some

absurd story that Limbert himself had written

it. I remember

that on my asking some one why such an idiotic thing had

been

said, my interlocutor replied : ” Oh, because, you know, it’s

just

the way he would have written !” My spirit

sank a little perhaps

as I reflected that with such analogies in our manner

there might

prove to be some in our fate.

It was during the next four or five years that our eyes were

open to what,

unless something could be done, that fate, at least

on Limbert’s part,

might be. The thing to be done was of

course to write the book, the book

that would make the differ-

ence, really justify the burden he had accepted

and consummately

express his power. For the works that followed upon The Major

Key he had inevitably to accept conditions the

reverse of brilliant,

at a time when the strain upon his resources had

begun to show

sharpness. With three babies, in due course, an ailing wife,

and a

complication still greater than these, it became highly

important

that a man should do only his best. Whatever Limbert did

was

his

his best ; so, at least, each time, I thought, and so I unfailingly said

somewhere, though it was not my saying it, heaven knows, that

made the

desired difference. Every one else indeed said it, and

there was always the

comfort, among multiplied worries, that his

position was quite assured. The

two books that followed The

Major Key did more than anything else to assure it,

and Jane

Highmore was always crying out : ” You stand alone, dear Ray

;

you stand absolutely alone !” Dear Ray used to tell me that he

felt

the truth of this in feebly-attempted discussions with his book

seller. His

sister-in-law gave him good advice into the bargain ;

she was a repository

of knowing hints, of esoteric learning. These

things were doubtless not the

less valuable to him for bearing

wholly on the question of how a reputation

might be, with a

little gumption, as Mrs. Highmore said, ” worked ” : save

when

she occasionally bore testimony to her desire to do, as Limbert

did, something some day for her own very self, I never heard

her speak of

the literary motive as if it were distinguishable

from the pecuniary. She

cocked up his hat, she pricked up

his prudence for him, reminding him that

as one seemed to take

one’s self, so the silly world was ready to take one.

It was a

fatal mistake to be too candid even with those who were all

right—

not to look and to talk prosperous, not at least to pretend

that one

had beautiful sales. To listen to her you would have thought

the profession of letters a wonderful game of bluff. Wherever

one’s idea

began it ended somehow in inspired paragraphs in

the newspapers.” I pretend, I assure you, that you are going off

like wildfire—I can at least do that for you !” she often declared,

prevented as she was from doing much else by Mr. Highmore’s

insurmountable

objection to their taking Mrs. Stannace.

I couldn’t help regarding the presence of this latter lady in

Limbert’s life

as the major complication : whatever he attempted

it

it appeared given to him to achieve as best he could in the narrow

margin

unswept by her pervasive skirts. I may have been mis-

taken in supposing

that she practically lived on him, for though it

was not in him to follow

adequately Mrs. Highmore’s counsel

there were exasperated confessions he

never made, scanty domestic

curtains he rattled on their rings. I may

exaggerate, in the

retrospect, his apparent anxieties, for these after all

were the years

when his talent was freshest and when, as a writer, he most

laid

down his line. It wasn’t of Mrs. Stannace, nor even, as time went

on, of Mrs. Limbert that we mainly talked when I got, at longer

intervals,

a smokier hour in the little grey den from which we

could step out, as we

used to say, to the lawn. The lawn was

the back-garden, and Limbert’s study

was behind the dining-

room, with folding-doors not impervious to the

clatter of the

children’s tea. We sometimes took refuge from it in the

depths

—a bush and a half deep—of the shrubbery, where was a

bench

that gave us a view, while we gossiped, of Mrs. Stannace’s

tiara-

like headdress nodding at an upper window. Within doors and

without, Limbert’s life was overhung by an awful region that

figured in his

conversation, comprehensively and with unpremedi-

tated art, as Upstairs.

It was Upstairs that the thunder gathered,

that Mrs. Stannace kept her

accounts and her state, that Mrs.

Limbert had her babies and her headaches,

that the bells forever

jangled for the maids, that everything imperative,

in short, took

place—everything that he had somehow, pen in hand, to

meet

and dispose of in the little room on the garden-level. I don’t

think he liked to go Upstairs, but no special burst of confidence

was

needed to make me feel that a terrible deal of service went.

It was the

habit of the ladies of the Stannace family to be

extremely waited on, and

I’ve never been in a house where three

maids and a nursery-governess gave

such an impression of a

retinue

retinue. ” Oh, they’re so deucedly, so hereditarily fine!”—I

remember

how that dropped from him in some worried hour.

Well, it was because Maud

was so universally fine that we had

both been in love with her. It was not

an air moreover for the

plaintive note : no private inconvenience could

long outweigh,

for him, the great happiness of these years—the

happiness

that sat with us when we talked and that made it always

amusing to talk, the sense of his being on the heels of success,

coming

closer and closer, touching it at last, knowing that

he should touch it

again and hold it fast and hold it high.

Of course when we said success we

didn’t mean exactly what

Mrs. Highmore, for instance, meant. He used to

quote at me,

as a definition, something from a nameless page of my

own,

some stray dictum to the effect that the man of his craft had

achieved it when of a beautiful subject his expression was com-

plete.

Wasn’t Lambert’s, in all conscience, complete ?

III

And yet it was bang upon this completeness that the turn

came, the turn I

can’t say of his fortune—for what was that ?—but

of his

confidence, of his spirits and, what was more to the point,

of his system.

The whole occasion on which the first symptom

flared out is before me as I

write. I had met them both at

dinner ; they were diners who had reached the

penultimate stage

—the stage which in theory is a rigid selection

and in practice a

wan submission. It was late in the season, and stronger

spirits

than theirs were broken ; the night was close and the air of

the

banquet such as to restrict conversation to the refusal of dishes

and consumption to the sniffing of a flower. It struck me all

the

the more that Mrs. Limbert was flying her flag. As vivid as a

page of her

husband’s prose, she had one of those flickers of fresh

ness that are the

miracle of her sex and one of those expensive

dresses that are the miracle

of ours. She had also a neat brougham

in which she had offered to rescue an

old lady from the possi-

bilities of a queer cab-horse ; so that when she

had rolled away

with her charge I proposed a walk home with her husband,

whom

I had overtaken on the doorstep. Before I had gone far with

him

he told me he had news for me—he had accepted, of all

people and of

all things, an ” editorial position.” It had come to

pass that very day,

from one hour to another, without time for

appeals or ponderations : Mr.

Bousefield, the proprietor of a

” high-class monthly,” making, as they

said, a sudden change, had

dropped on him heavily out of the blue. It was

all right—there

was a salary and an idea, and both of them, as such

things went,

rather high. We took our way slowly through the empty

streets,

and in the explanations and revelations that, as we lingered

under

lamp-posts, I drew from him, I found, with an apprehension that

I tried to gulp down, a foretaste of the bitter end. He told me

more than

he had ever told me yet. He couldn’t balance

accounts—that was the

trouble ; his expenses were too rising a

tide. It was absolutely necessary

that he should at last make

money, and now he must work only for that. The

need, this last

year, had gathered the force of a crusher ; it had rolled

over him

and laid him on his back. He had his scheme; this time he

knew

what he was about ; on some good occasion, with leisure to talk

it over, he would tell me the blessed whole. His editorship would

help him,

and for the rest he must help himself. If he couldn’t,

they would have to

do something fundamental—change their life

altogether, give up

London, move into the country, take a house

at thirty pounds a year, send

their children to the Board-school. I

saw

saw that he was excited, and he admitted that he was : he had

waked out of a

trance. He had been on the wrong tack ; he had

piled mistake on mistake. It

was the vision of his remedy that

now excited him : ineffably, grotesquely

simple, it had yet come

to him only within a day or two. No, he wouldn’t

tell me what

it was : he would give me the night to guess, and if I

shouldn’t

guess it would be because I was as big an ass as himself.

How

ever, a lone man might be an ass : it was

nobody’s business. He

had five people to carry, and the back must be

adjusted to the

burden. He was just going to adjust his back. As to the

editor

ship, it was simply heaven-sent, being not at all another case of

The Blackport Beacon, but a case of the very

opposite. The

proprietor, the great Mr. Bousefield, had approached him

precisely

because his name, which was to be on the cover, didn’t represent

the chatty. The whole thing was

to be—oh, on fiddling little

lines, of course—a protest

against the chatty. Bousefield wanted

him to be himself; it was for himself

Bousefield had picked him

out. Wasn’t it beautiful and brave of Bousefield

? He wanted

literature, he saw the great reaction coming, the way the cat

was

going to jump. ” Where will you get literature ?” I wofully

asked

; to which he replied with a laugh that what he had to get

was not

literature, but only what Bousefield would take for it.

In that single phrase, without more ado, I discovered his

famous remedy.

What was before him for the future was not to

do his work, but to do what

somebody else would take for it. I

had the question out with him on the

next opportunity, and of all

the lively discussions into which we had been

destined to drift it

lingers in my mind as the liveliest. This was not, I

hasten to

add, because I disputed his conclusions : it was an effect of

the

very force with which, when I had fathomed his wretched

premises,

I embraced them. It was very well to talk, with Jane

Highmore,

Highmore, about his standing alone ; the eminent relief of this

position had

brought him to the verge of ruin. Several persons

admired his

books—nothing was less contestable ; but they

appeared to have a

mortal objection to acquiring them by sub-

scription or by purchase : they

begged, or borrowed, or stole, they

delegated one of the party perhaps to

commit the volumes to

memory and repeat them, like the bards of old, to

listening

multitudes. Some ingenious theory was required, at any rate,

to

account for the inexorable limits of his circulation. It wasn’t a

thing for five people to live on ; therefore either the objects

circulated

must change their nature, or the organisms to be

nourished must. The former

change was perhaps the easier to

consider first. Limbert considered it with

extraordinary ingenuity

from that time on, and the ingenuity, greater even

than any I had

yet had occasion to admire in him, made the whole next stage

of

his career rich in curiosity and suspense.

“I have been butting my head against a wall,” he had said in

those hours of

confidence ; ” and with the same sublime imbecility,

if you’ll allow me the

word, you, my dear fellow, have kept

sounding the charge. We’ve sat prating

here of ‘success,’ heaven

help us, like chanting monks in a cloister,

hugging the sweet

delusion that it lies somewhere in the work itself, in

the expres-

sion, as you said, of one’s subject, or the intensification, as

some-

body else somewhere said, of one’s note. One has been going on,

in short, as if the only thing to do were to accept the law of one’s

talent, and thinking that if certain consequences didn’t follow, it

was

only because one hadn’t accepted enough. My disaster has

served me

right—I mean for using that ignoble word at all. It’s

a mere

distributor’s, a mere hawker’s word. What is

‘success’

anyhow ? When a book’s right, it’s right—shame to it

surely if

it isn’t. When it sells it sells—it brings money like

potatoes or

beer.

The Yellow Book—Vol. VI. cbeer. If there’s dishonour one way and inconvenience the other,

it certainly

is comfortable, but it as certainly isn’t glorious, to

have escaped them.

People of delicacy don’t brag either about

their probity or about their

luck. Success be hanged !—I want to

sell. It’s a question of life

and death. I must study the way.

I’ve studied too much the other

way—I know the other way

now, every inch of it. I must cultivate the

market—it’s a science

like another. I must go in for an infernal

cunning. It will be

very amusing, I foresee that ; the bustle of life will

become

positively exhilarating. I haven’t been obvious—! must be

obvious. I haven’t been popular—I must

be popular. It’s

another art—or

perhaps it isn’t an art at all. It’s something else ;

one must find out

what it is. Is it something awfully queer

?—

you blush !—something barely decent ? All the greater

incentive

to curiosity ! Curiosity’s an immense motive ; we shall have

tremendous larks. They all do it ; it’s only a question of how.

Of course

I’ve everything to unlearn; but what is life, as Jane

Highmore says, but a

lesson ? I must get all I can, all she can

give me, from Jane. She can’t

explain herself much ; she’s all

intuition ; her processes are obscure ;

it’s the spirit that swoops

down and catches her up. But I must study her

reverently in

her works. Yes, you’ve defied me before, but now my loins

are

girded : I declare I’ll read one of them—I really will : I’ll

put it

through if I perish !”

I won’t pretend that he made all these remarks at once ;

but there wasn’t

one that he didn’t make at one time or another,

for suggestion and occasion

were plentiful enough, his life being

now given up altogether to his new

necessity. It wasn’t a

question of his having or not having, as they say,

my intellectual

sympathy : the brute force of the pressure left no room for

judg-

ment ; it made all emotion a mere recourse to the spy-glass.

I

watched

watched him as I should have watched a long race or a long chase,

irresistibly siding with him, but much occupied with the calcula-

tion of

odds. I confess indeed that my heart, for the endless

stretch that he

covered so fast, was often in my throat. I

saw him peg away over the

sun-dappled plain, I saw him double

and wind and gain and lose ; and all

the while I secretly enter-

tained a conviction. I wanted him to feed his

many mouths, but

at the bottom of all things was my sense that if he should

succeed

in doing so in this particular way I should think less well of

him, and I had an absolute terror of that. Meanwhile, so far as I

could, I

backed him up, I helped him : all the more that I had

warned him immensely

at first, smiled with a compassion it was

very good of him not to have

found exasperating, over the com-

placency of his assumption that a man

could escape from himself.

Ray Limbert, at all events, would certainly

never escape ; but one

could make believe for him, make believe very

hard—an under-

taking in which, at first, Mr. Bousefield was visibly

a blessing.

Limbert was delightful on the business of this being at last

my

chance too—my chance, so miraculously vouchsafed, to appear

with a certain luxuriance. He didn’t care how often he printed

me, for

wasn’t it exactly in my direction Mr. Bousefield held that

the cat was

going to jump ? This was the least he could do for

me. I might write on

anything I liked—on anything at least

but Mr. Limbert’s second

manner. He didn’t wish attention

strikingly called to his second manner ;

it was to operate in-

sidiously ; people were to be left to believe they

had discovered it

long ago. ” Ralph Limbert ?—why, when did we ever

live with-

out him ? “—that’s what he wanted them to say. Besides,

they

hated manners—let sleeping dogs lie. His understanding

with

Mr. Bousefield—on which he had had not at all to insist ; it

was

the excellent man who insisted—was that he should run one of

his

beautiful

beautiful stories in the magazine. As to the beauty of his story,

however,

Limbert was going to be less admirably straight than as

to the beauty of

everything else. That was another reason why

I mustn’t write about his new

line : Mr. Bousefield was not to be

too definitely warned that such a

periodical was exposed to prosti-

tution. By the time he should find it out

for himself, the public—

le gros public—would have bitten, and then

perhaps he would be

conciliated and forgive. Everything else would be

literary in

short, and above all I would be ; only Ralph Limbert

wouldn’t—

he’d chuck up the whole thing sooner. He’d be vulgar, he’d

be

rudimentary, he’d be atrocious : he’d be elaborately what he hadn’t

been before.

I duly noticed that he had more trouble in making ” everything

else ”

literary than he had at first allowed for ; but this was largely

counteracted by the ease with which he was able to obtain that

that mark

should not be overshot. He had taken well to heart

the old lesson of the

Beacon ; he remembered that he was after

all

there to keep his contributors down much rather than to keep

them up. I

thought at times that he kept them down a trifle

too far, but he assured me

that I needn’t be nervous : he had his

limit—his limit was

inexorable. He would reserve pure vulgarity

for his serial, over which he

was sweating blood and water ;

elsewhere it should be qualified by the

prime qualification, the

mediocrity that attaches, that endears.

Bousefield, he allowed, was

proud, was difficult : nothing was really good

enough for him but

the middling good ; but he himself was prepared for

adverse

comment, resolute for his noble course. Hadn’t Limbert more-

over, in the event of a charge of laxity from headquarters, the

great

strength of being able to point to my contributions ?

Therefore I must let

myself go, I must abound in my peculiar

sense, I must be a resource in case

of accidents. Limbert’s vision

of

of accidents hovered mainly over the sudden awakening of Mr.

Bousefield to

the stuff that, in the department of fiction, his editor

was smuggling in.

He would then have to confess in all humility

that this was not what the

good old man wanted, but I should be

all the more there as a compensatory

specimen. I would cross the

scent with something showily impossible,

splendidly unpopular—

I must be sure to have something on hand. I

always had plenty

on hand—poor Limbert needn’t have worried : the

magazine was

forearmed, each month, by my care, with a retort to any

possible

accusation of trifling with Mr. Bousefield’s standard. He had

admitted to Limbert, after much consideration indeed, that he was

prepared

to be perfectly human ; but he had added that he was not

prepared for an

abuse of this admission. The thing in the world

I think I least felt myself

was an abuse, even though (as I had

never mentioned to my friendly editor)

I too had my project for

a bigger reverberation. I daresay I trusted mine

more than I

trusted Limbert’s ; at all events, the golden mean in which, as

an

editor, in the special case, he saw his salvation, was something I

should be most sure of if I were to exhibit it myself. I exhibited

it,

month after month, in the form of a monstrous levity, only

praying heaven

that my editor might now not tell me, as he had

so often told me, that my

result was awfully good. I knew what

that would signify—it would

signify, sketchily speaking, disaster.

What he did tell me, heartily, was

that it was just what his game

required: his new line had brought with it

an earnest assumption—

earnest save when we privately laughed about

it—of the locutions

proper to real bold enterprise. If I tried to

keep him in the dark

even as he kept Mr. Bousefield, there was nothing to

show that I was

not tolerably successful : each case therefore presented a

promising

analogy for the other. He never noticed my descent, and it

was

accordingly possible that Mr. Bousefield would never notice

his.

But

But would nobody notice it at all ?—that was a question that

added a

prospective zest to one’s possession of a critical sense. So

much depended

upon it that I was rather relieved than otherwise

not to know the answer

too soon. I waited in fact a year—the

year for which Limbert had

cannily engaged, on trial, with Mr.

Bousefield ; the year as to which,

through the same sharpened

shrewdness, it had been conveyed in the

agreement between them

that Mr. Bousefield was not to intermeddle. It had

been Lim-

bert’s general prayer that we would, during this period, let

him

quite alone. His terror of my direct rays was a droll, dreadful

force that always operated : he explained it by the fact that I

understood

him too well, expressed too much of his intention,

saved him too little

from himself. The less he was saved, the

more he didn’t sell : I literally

interpreted, and that was simply fatal.

I held my breath, accordingly ; I did more—I closed my eyes, I

guarded my treacherous ears. He induced several of us to do that

(ot such

devotions we were capable) so that not even glancing at

the thing from

month to month, and having nothing but his

shamed, anxious silence to go

by, I participated only vaguely in

the little hum that surrounded his act

of sacrifice. It was blown

about the town that the public would be

surprised ; it was hinted,

it was printed, that he was making a desperate

bid. His new

work was spoken of as ” more calculated for general

acceptance. “

These tidings produced in some quarters much reprobation,

and

nowhere more, I think, than on the part of certain persons who

had

never read a word of him, or assuredly had never spent a

shilling on him,

and who hung for hours over the other attractions

of the newspaper that

announced his abasement. So much as-

perity cheered me a

little—seemed to signify that he might really

be doing something. On

the other hand, I had a distinct alarm ;

some one sent me, for some alien

reason, an American journal

(containing

(containing frankly more than that source of discomposure) in

which was

quoted a passage from our friend’s last instalment.

The passage—I

couldn’t for my life help reading it—was simply

superb. Ah, he would have to move to the country if that was

the

worst he could do ! It gave me a pang to see how little, after

all, he had

improved since the days of his competition with Pat

Moyle. There was

nothing in the passage quoted in the American

paper that Pat would for a

moment have owned. During the last

weeks, as the opportunity of reading the

complete thing drew

near, one’s suspense was barely endurable, and I shall

never forget

the July evening on which I put it to rout. Coming home

to

dinner I found the two volumes on my table, and I sat up with

them

half the night, dazed, bewildered, rubbing my eyes, wonder-

ing at the

monstrous joke. Was it a monstrous joke, his

second

manner—was this the new line, the

desperate bid, the scheme for

more general acceptance and the remedy for

material failure ?

Had he made a fool of all his following, or had he, most

injuriously,

made a still bigger fool of himself? Obvious ?—where

the deuce

was it obvious ? Popular ?—how on earth could it be

popular ?

The thing was charming with all his charm and powerful with

all

his power ; it was an unscrupulous, an unsparing, a shameless,

merciless masterpiece. It was, no doubt, like the old letters to

the Beacon, the worst he could do ; but the perversity of

the

effort, even though heroic, had been frustrated by the purity of

the

gift. Under what illusion had he laboured, with what wavering,

treacherous compass had he steered ? His honour was inviolable,

his

measurements were all wrong. I was thrilled with the whole

impression and

with all that came crowding in its train. It was

too grand a

collapse—it was too hideous a triumph ; I exulted

almost with

tears—I lamented with a strange delight. Indeed as

the short night

waned, and, threshing about in my emotion, I

fidgeted

fidgeted to my high-perched window for a glimpse of the summer

dawn, I

became at last aware that I was staring at it out of eyes

that had

compassionately and admiringly filled. The eastern sky,

over the London

housetops, had a wonderful tragic crimson.

That was the colour of his

magnificent mistake.

IV

If something less had depended on my impression I daresay I

should have

communicated it as soon as I had swallowed my

breakfast ; but the case was

so embarrassing that I spent the first

half of the day in reconsidering it,

dipping into the book again,

almost feverishly turning its leaves and

trying to extract from

them, for my friend’s benefit, some symptom of

re-assurance, some

ground for felicitation. But this rash challenge had

consequences

merely dreadful ; the wretched volumes, imperturbable and

impeccable, with their shyer secrets and their second line of

defence, were

like a beautiful woman more denuded or a great

symphony on a new hearing.

There was something quite

exasperating in the way, as it were, they stood

up to me. I

couldn’t, however, be dumb—that was to give the wrong

tinge

to my disappointment ; so that, later in the afternoon, taking

my

courage in both hands, I approached, with a vain indirectness,

poor

Limbert’s door. A smart victoria waited before it, in

which, from the

bottom of the street, I saw that a lady who had

apparently just issued from

the house was settling herself. I

recognised Jane Highmore and instantly

paused till she should

drive down to me. She presently met me half-way and

as soon

as she saw me stopped her carriage in agitation. This was a

relief—it postponed a moment the sight of that pale, fine face

of

Limbert’s

Limbert’s fronting me for the right verdict. I gathered from the

flushed

eagerness with which Mrs. Highmore asked me if I had

heard the news that a

verdict of some sort had already been

rendered.

” What news ?—about the book ?”

” About that horrid magazine. They’re shockingly upset.

He has lost his

position—he has had a fearful flare-up with Mr.

Bousefield.”

I stood there blank, but not unconscious, in my blankness, of

how history

repeats itself. There came to me across the years

Maud’s announcement of

their ejection from the Beacon, and

dimly,

confusedly the same explanation was in the air. This

time, however, I had

been on my guard; I had had my suspicion.

” He has made it too flippant ?”

I found breath after an instant to

inquire.

Mrs. Highmore’s blankness exceeded my own. ” Too

flippant ? He has made it

too oracular. Mr. Bousefield says

he has killed it.” Then perceiving my

stupefaction : ” Don’t

you know what has happened ?” she pursued : ” isn’t

it because

in his trouble, poor love, he has sent for you, that you’ve

come ? You’ve heard nothing at all ? Then you had better

know before you

see them. Get in here with me—I’ll take you

a turn and tell you.” We

were close to the Park, the Regent’s,

and when with extreme alacrity I had

placed myself beside her

and the carriage had begun to enter it she went on

: ” It was

what I feared, you know. It reeked with culture. He keyed

it

up too high.”

I felt myself sinking in the general collapse. ” What are you

talking about

?”

” Why, about that beastly magazine. They’re all on the streets.

I shall have

to take mamma.”

I pulled

I pulled myself together. ” What on earth, then, did Bousefield

want ? He

said he wanted elevation.”

” Yes, but Ray overdid it.”

” Why, Bousefield said it was a thing he couldn’t

overdo.”

” Well, Ray managed—he took Mr. Bousefield too literally. It

appears

the thing has been doing dreadfully, but the proprietor

couldn’t say

anything, because he had covenanted to leave the

editor quite free. He

describes himself as having stood there in

a fever and seen his ship go

down. A day or two ago the year

was up, so he could at last break out. Maud

says he did break

out quite fearfully ; he came to the house and let poor

Ray have

it. Ray gave it to him back ; he reminded him of his own idea

of

the way the cat was going to jump.”

I gasped with dismay. ” Has Bousefield abandoned that idea ?

Isn’t the cat

going to jump ?”

Mrs. Highmore hesitated. ” It appears that she doesn’t seem in

a hurry. Ray,

at any rate, has jumped too far ahead of her. He

should have temporised a

little, Mr. Bousefield says ; but I’m

beginning to think, you know,” said

my companion, ” that Ray

can’t temporise.”

Fresh from my emotions of the previous twenty-four hours, I

was scarcely in

a position to disagree with her.

” He published too much pure thought.”

” Pure thought ?” I cried. ” Why, it struck me so often—

certainly in

a due proportion of cases—as pure drivel !”

” Oh, you’re a worse purist than he ! Mr. Bousefield says that

of course he

wanted things that were suggestive and clever, things

that he could point

to with pride. But he contends that Ray

didn’t allow for human weakness. He

gave everything in too stiff

doses.”

Sensibly, I fear, to my neighbour, I winced at her words ; I felt

a prick

a prick that made me meditate. Then I said : ” Is that, by chance,

the way

he gave me? Mrs. Highmore remained silent so

long

that I had somehow the sense of a fresh pang ; and after a

minute, turning in my seat, I laid my hand on her arm, fixed my

eyes upon

her face and pursued pressingly : ” Do you suppose it to

be to my

‘Occasional Remarks’ that Mr. Bousefield refers ?”

At last she met my look. ” Can you bear to hear it ?”

” I think I can bear anything now. “

” Well, then, it was really what I wanted to give you an inkling

of. It’s

largely over you that they’ve quarrelled. Mr. Bousefield

wants him to chuck

you.”

I grabbed her arm again. “And Limbert won’t

?”

” He seems to cling to you. Mr. Bousefield says no magazine

can afford

you.”

I gave a laugh that agitated the very coachman. ” Why, my