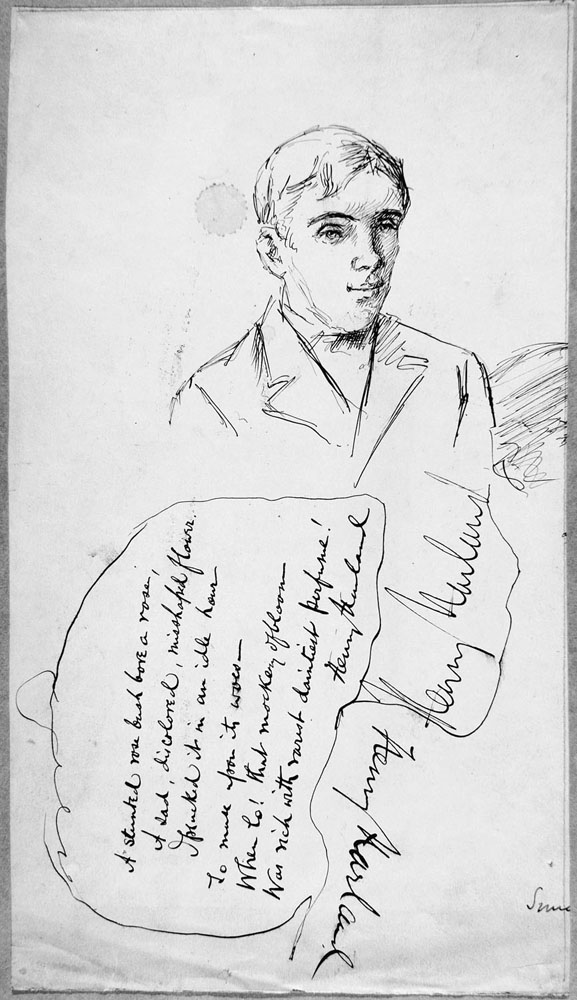

Henry Harland

(1861 – 1905)

“A stunted rose bush bore a rose,

A sad discoloured, misshaped flower.

I plucked it in an idle hour

To muse upon its woes –

When lo! That mockery of bloom

Was rich with rarest daintiest perfume!

Henry Harland”

Born in New York City on March 1st, 1861, Henry Harland is mainly remembered for the central role he played in the artistic and literary coteries of fin-de-siècle London, especially his editorship of The Yellow Book (1894-1897). He was the son of Justice Thomas Harland and Irene Jones Harland of Norwich, Connecticut. Harland studied in New York City College from 1877 to 1880, before briefly attending theology classes at the Harvard Divinity School (1881-1882). He left the USA in 1882 to spend a year in Rome. Upon his return to New York, he worked in his father’s legal practice until 1886, while starting to spend his free time writing. In May 1884, he married Aline Herminie Merriam (1860-1939), an American music lover who shared her husband’s artistic interests and played a crucial role in his career. Aline also wrote for The Yellow Book as “Renée de Coutans,” she contributed a love poem (Vol. 10) and a short story (Vol. 12). After Harland died in 1905, she published some of his work posthumously.

Like Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) and other fin-de-siècle authors, Harland cultivated the art of lying and enjoyed fictionalizing his own life. Fascinated by the aristocracy, Harland refashioned himself as the heir of a Russian prince: for this reason, many biographies, including the pre-2004 editions of the Dictionary of National Biography, falsely state that he was born in St. Petersburg. At the beginning of his literary career, he wrote under the allegedly Jewish pen name “Sidney Luska,” misleading some of his contemporaries to think he was Jewish himself. Later in his life, he attempted to trace his lineage, hoping to find distinguished aristocrats among his ancestors, and he enjoyed referring to himself and Aline as “Sir and Lady Harland.”

The first book Harland published under the pseudonym “Sidney Luska” was As It Was Written — A Jewish Musician’s Story (1885). It was the first in a series of novels depicting the Jewish American circles of his time, which he thought particularly picturesque, and to which he felt very close in spite of his attraction to Roman Catholicism. It was followed by Mrs. Peixada (1886), The Yoke of Thorah (1887), and My Uncle Florimond (1888), which were written in the same vein. Although Harland gave up this pseudonym once his actual identity was revealed, he continues to be recognized as one of the first American novelists to make the Jewish community the centre of his fiction. The style of these early novels is radically different from that of his later romances and half-realistic, half-sentimental descriptions of Bohemian life in Paris, Rome, or London.

In 1889, the Harlands left the USA for Europe, settling first in Paris before moving to London. Here in their flat on Cromwell Road they received many personalities of the 1890s, and were friends with a variety of authors and artists of the time, ranging from the most respectable, such as Edmund Gosse (1849-1928), to the most avant-garde, such as Arthur Symons (1865-1945), Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898), and Frederick Rolfe (aka Baron Corvo) (1860-1913). In the late 1880s and early 1890s, Harland published the novels Grandison Mather (1889), Two Voices (1890), and Mea Culpa (1891), as well as two collections of short stories, A Latin Quarter Courtship (1889) and Mademoiselle Miss (1893), all under his actual name. These are transitional texts heralding the type of fiction he was to produce during his Yellow Book years. Some of them are already inspired by his fascination for Bohemian life and the aristocracy, and obviously influenced by his great admiration for Henry James (1843-1916) and Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893), whose styles he strove to imitate.

During the summer of 1893, at Sainte-Marguerite, Brittany, the Harlands were the centre of a small group of novelists, art critics, and artists, including Charles Conder (1868-1909), Dugald S. MacColl (1859-1948) and Alfred Thornton (1863-1939), who shared an interest in avant-garde art and publications. The GROB — named after some of its participants, Littelus Goold and three sisters named Robinson — was a kind of literary camp with an unconventional, at times eccentric, atmosphere. It was here that MacColl made the daring suggestion of creating a new magazine in which the letterpress and the art would be independent of each other. A few months later, on January 1st, 1894, Harland and Beardsley allegedly discussed the launching of a new magazine that would publish works unlikely to be accepted by mainstream publishers. John Lane (1854-1925) was contacted at The Bodley Head, and he immediately expressed his enthusiasm: the first volume of The Yellow Book was released in April 1894, with Beardsley as art editor and Harland as literary editor.

With fourteen realistic short stories or sentimental romances to his credit, as well as three satirical essays under the pen name “The Yellow Dwarf,” Harland was the only author who contributed at least one story or article to each volume of The Yellow Book. Some have suggested that he published two other stories under the pseudonymns “Scott Matthewson” (“La Goya: A Passion of the Peruvian Desert,” Volume 10) and “Robert Shews” (“The Elsingfords,” Volume 11), though there is no actual proof of this. Harland’s Yellow Book stories were also included in two of his collections – Grey Roses (1895) and Comedies and Errors (1898). While he never became the equal of James and Maupassant, he did contribute to the development of the short story as a genre. His fiction often presents artists struggling with poverty in Paris, Rome, or London, or aristocrats struggling with the increasing power of the middle class. As such, it reflects the preoccupations of many fin-de-siècle artists who, like Wilde, considered the artistic and social elites to be a last stronghold against what they saw as growing social mediocrity. Another characteristic of Harland’s Yellow Book stories is the nostalgia many of his characters express for the golden years of their childhood, which only involuntary memory can revive, and then only for privileged moments. One critic even described Harland as a forerunner of Marcel Proust (O’Brien).

In Volumes 7, 9, and 10 of The Yellow Book, Harland published three overtly polemical “letters to the editor” (that is, to himself). These appeared under the pen name “The Yellow Dwarf” – a reference to the French “Nain Jaune,” initially a cruel fairy tale character and later the title of at least two early 19th-century French satirical magazines. The three essays rekindled the audience’s waning interest in the magazine after Wilde’s trials and Lane’s dismissal of Beardsley as art editor in April 1895. The piece in Volume 9 was accompanied by Max Beerbohm’s mysterious depiction of a yellow dwarf wearing a black mask — notably the only colour plate in the whole print run of the magazine. These “letters to the editor” adopt an ironic tone, attacking in a light though incisive manner both authors and readers of the late-19th century, and at times challenging the quality of even The Yellow Book itself. Harland also contributed critical essays to other magazines and books — including a piece on the short story that gives an interesting insight into the genre (“Concerning the Short Story”).

Harland was famous for his eccentricities more than for the quality of his writings. His literary fame was slow to come, and only The Cardinal’s Snuff Box , published in 1900, met with some success. Two other works followed: The Lady Paramount (1902) and My Friend Prospero (1904). All three novels reflect his late conversion to Roman Catholicism and focus on the rediscovered beauty of the Catholic faith. The tuberculosis from which Harland had been suffering for years ultimately compelled him to spend long months in the milder and drier climate of San Remo, Italy. He died there on December 20th, 1905, but was later buried in his family’s hometown of Norwich, Connecticut. He left behind the incomplete manuscript of The Royal End, which his wife finished and published in 1909. His correspondence is to be found primarily in the collections of the Boston Public Library, Columbia University, and Westfield College in London.

© 2012, Barbara Schmidt

Barbara Schmidt is a senior lecturer at the Université de Lorraine, France. She wrote her doctoral dissertation on The Yellow Book (“ Le Yellow Book, ou les masques des années 1890,” University of Nancy [Lorraine], France, 1993). She has translated several contemporary American novels, including Laird Hunt’s Indiana and Indiana; The Exquisite, Ander Monson’s Other Electricities , Lydia Millet’s How the Dead Dream , and Adam Levin’s The Instructions.

Selected publications by Henry Harland

Novels

- As It Was Written: A Jewish Musician’s Story. New York: Cassell, 1885. [Sidney Luska].

- The Cardinal’s Snuff Box. London; New York: John Lane: The Bodley Head, 1900.

- Grandison Mather; or, An Account of the Fortunes of Mr and Mrs Thomas Gardiner. New York: Cassell, 1889. [Sydney Luska].

- The Lady Paramount. London; New York: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1902.

- A Land of Love. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1887. [Sidney Luska].

- Mea Culpa — A Woman’s Last Word. New York: John W. Lovell, 1891.

- Mrs Peixada. New York: Cassell, 1886. [Sidney Luska]. My Friend Prospero: A Novel. New York: McLure, Phillips, 1904.

- My Uncle Florimond. Boston. D. Lothrop 1888. [Sidney Luska].

- The Royal End: A Romance. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1909. Posthumous publication, completed by his wife, Aline Merriam Harland.

- Two Voices. New York: Cassell, 1890.

- Two Women or One? From the Mss. of Dr. Leonard Benary . New York: Cassell, 1890.

- The Yoke of Thorah. 1887. New York: Cassell, 1896. [Sidney Luska].

Short Stories

- Comedies and Errors. London; New York: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1898. Includes nine Yellow Book short stories: “Rosemary for Remembrance,” The Yellow Book 5 (Apr. 1895): 77-96; “Tirala-Tirala,” The Yellow Book 6 (July 1895): 65-76; “The Queen’s Pleasure,” The Yellow Book 7 (Oct. 1895): 29-70; “P’tit Bleu,” The Yellow Book 8 (Jan. 1896): 65-93; “Cousin Rosalys,” The Yellow Book 9 (Apr. 1896): 25-53; “The Invisible Prince,” The Yellow Book 10 (July 1896): 59-87; “The Friend of Man,” The Yellow Book 11 (Oct. 1896): 51-79; “Flower o’ the Clove,” The Yellow Book 12 (Jan. 1897): 65-109; “Merely Prayers,” The Yellow Book 13 (Apr. 1897): 19-50.

- Grey Roses. London: John Lane: The Bodley Head, 1895. Includes five Yellow Book short stories: “Mercedes,” The Yellow Book 1 (Apr. 1894): 135-142; “A Broken Looking-Glass,” The Yellow Book 1 (Apr. 1894): 142-148; “A Responsibility,” The Yellow Book 2 (July 1894): 103-115; “When I Am King,” The Yellow Book 3 (Oct. 1894): 71-86; “The Bohemian Girl,” The Yellow Book 4 (Jan. 1895): 12-44.

- A Latin Quarter Courtship, and Other Stories. New York: Cassell, 1889.

- Mademoiselle Miss, and Other Stories. London: William Heinemann, 1893.

Play

- The Light Sovereign. With Hubert Crackanthorpe . London: Lady Henry Harland, 1917. Posthumous publication.

Articles / Essays

- “A Birthday Letter. ” The Yellow Book 9 (Apr. 1896): 11-22. ([The Yellow Dwarf]).

- “Books: A Letter to the Editor. ” The Yellow Book 7 (Oct. 1895): 125-143. ([The Yellow Dwarf]).

- “Concerning the Short Story.” Academy June 5, 1897: 6-7.

- “Dogs, Cats, Books and the Average Man.” The Yellow Book 10 (July 1896): 11-23. ([The Yellow Dwarf]).

- “Octave Feuillet’s Novels.” The Romance of a Poor Young Man . By Octave Feuillet. Trans. by C.G. Compton. New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1902. v-xxvii.

Selected publications about Henry Harland

- Alexander, Calvert. The Catholic Literary Revival. 1935. New York: Kennikat Press, 1968. 209-214.

- Beckson, Karl. Henry Harland: His Life and Work. London: Eighteen Nineties Society, 1978.

- —, and Mark Samuels Lasner. “The Yellow Book and Beyond: Selected Letters of Henry Harland to John Lane.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920 42.4 (1999): 406-432.

- Burke, Rev. John J. “Mr. Henry Harland’s Novels.” Catholic World (June 1902): 398-403.

- Chan, Winnie. The Economy of the Short Story in British Periodicals of the 1890s . New York; London: Routledge, 2007.

- Cheshire, David, and Malcolm Bradbury. “American Realism and the Romance of Europe: Fuller, Frederic, Harland.” Perspectives in American History . Vol. 4. Cambridge, Mass.: Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History, Harvard University, 1970. 285-310.

- Clarke, John J. “Henry Harland: A Critical Biography.” Unpublished diss. Providence: Brown University, 1957.

- C.Q.P. “Henry Harland.” The Spike; or, The Victoria University College Review June 1922: 65-66.

- Foote, Stephanie. “Ethnic Plotting: Henry Harland and the Jewish Writer.” American Literature 75.1 (Mar. 2003): 119-140.

- Gatton, John Spalding. “‘Much Talk of the Y.B.’: Henry Harland and the Debut of ‘The Yellow Book’.” Victorian Periodicals Review 13.4 (Winter 1980): 132-134.

- “Glastonbury, G.” [Aline HARLAND]. “The Life and Writings of Henry Harland.” Irish Monthly 39.454 (Apr. 1911): 210-219.

- Harap, Louis. “The Strange Case of Henry Harland.” The Image of the Jew in American Literature: From Early Republic to Mass Immigration . 2nd. rev. ed. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse UP, 2003. 455-471.

- Harkins, E. F. “Henry Harland.” Little Pilgrimages Among the Men Who Have Written Famous Books — Second Series . Boston: L. C. Page & Company, 1903. 201-218.

- James, Henry. “The Story-Teller at Large: Mr Henry Harland.” Fortnightly Review 1 Apr. 1898: 650-654.

- Kitcat, Mabel. “Henry Harland in London.” Bookman (New York) Aug. 1909: 609-613.

- Lasner, Mark Samuels. “Ethel Colburn Mayne’s ‘Reminiscences of Henry Harland’.” Bound for the 1890s: Essays on Writing and Publishing in Honor of James G. Nelson . Ed. Jonathan Allison. High Wycombe, Bucks.: Rivendale Press, 2006.

- Le Gallienne, Richard. The Romantic Nineties. New York: Doubleday, Page, 1925. 233-238.

- Obituary. Athenaeum 30 Dec. 1905.

- Obituary. The Times 22 Dec. 1905. 10f.

- O’Brien, Justin. “Henry Harland, An American Forerunner of Proust.” Modern Language Notes 54.6 (June 1939): 420-428.

- Mix, Katherine Lyon. A Study in Yellow: The Yellow Book and Its Contributors . Lawrence: U of Kansas Press, 1960. Parry, Albert. “Henry Harland: Expatriate.” Bookman (New York) Jan. 1933: 1-10.

- Roberts, Donald A. “Henry Harland and His World.” Commonweal 8 Feb. 1928: 1039-1040.

- Stanford, Derek, ed. Short Stories of the Nineties: A Biographical Anthology . London: John Baker, 1970. 179-186.

- Stead, Evanghélia. “Les perversions du merveilleux dans la petite revue; ou, Comment le Nain Jaune se mua en Yellow Dwarf dans treize volumes jaune et noir.” Anamorphoses décadentes. L’art de la défiguration 1880-1914 . Etudes offertes à Jean de Palacio. Eds. Sylvie Thorel-Cailleteau, and Isabelle Krzywkowski. Paris: PU Paris-Sorbonne, 2002. 109-132.

- Weeks, Donald. Two Friends: Frederick Rolfe and Henry Harland . Edinburgh: Tragara Press, 1978.

- Weintraub, Stanley. “Harland, Henry (1861–1905).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/33714, accessed 8 May 2012].

- —. The London Yankees: Portraits of American Writers and Artists in England, 1894-191 4. New York; London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979.

- “What the ‘Yellow Book’ Is To Be — Some Meditations With Its Editors.” Sketch 5 (Apr. 11, 1894): 557-558.

- Worth, George J. “The English ‘Maupassant School’ of the 1890s: Some Reservations.” Modern Language Notes 72.5 (May 1957): 337-340.

MLA citation:

Schmidt, Barbara. “Henry Harland (1861-1905),” Y90s Biographies, 2012. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://www.1890s.ca/harland_bio/