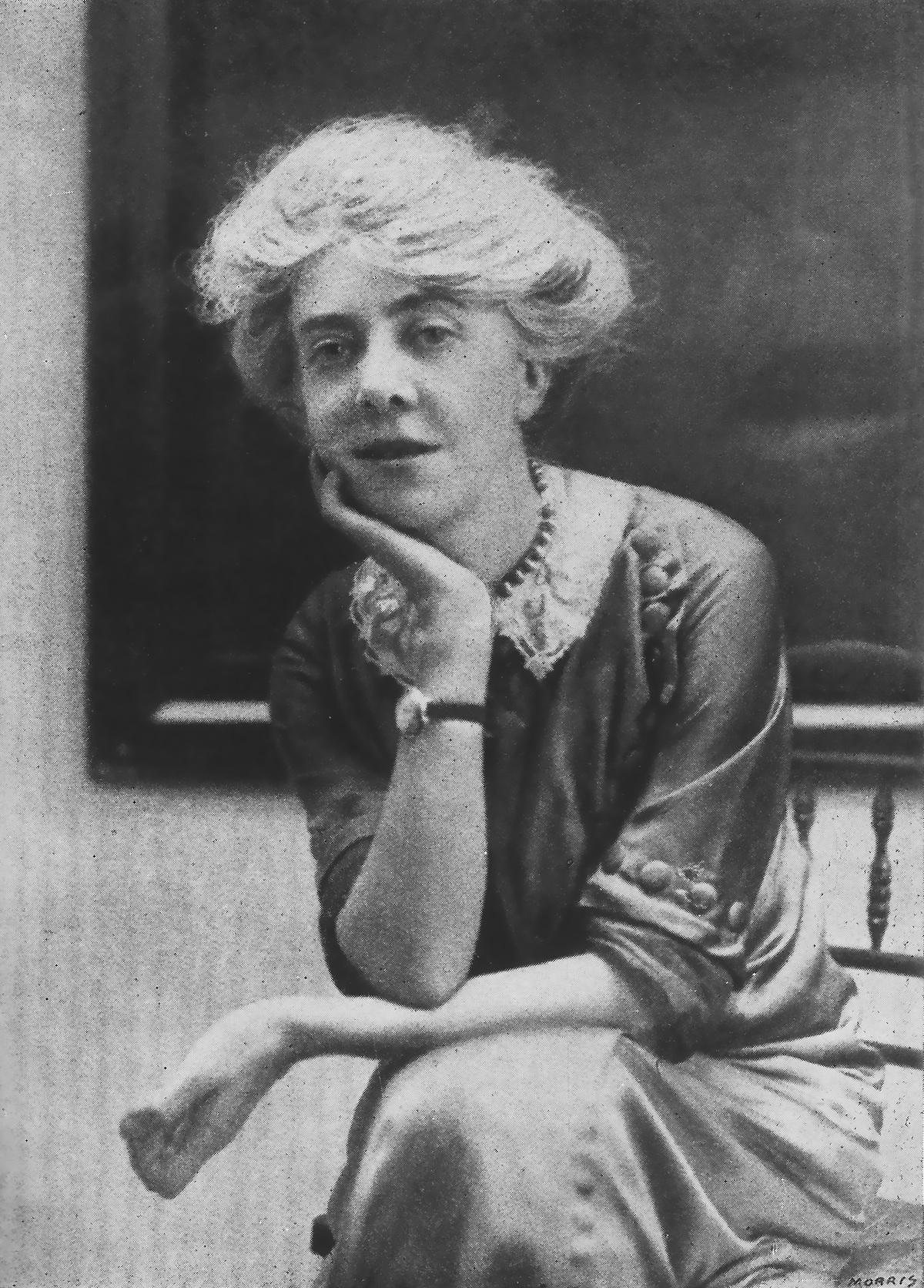

Ethel Colburn Mayne [aka Frances E. Huntley]

(1865-1941)

Ethelind Frances Colburn Mayne was born on January 7, 1865 in Johnstown, County Kilkenny, the second child of Charles Edward Bolton Mayne, of the Royal Irish Constabulary, and Charlotte Emily Henrietta Sweetman. The Maynes were Anglo–Irish Protestants dating back to Elizabethan times; Sweetman’s Protestantism was of a more recent vintage (though her Irish roots went even further back than the Maynes’), as her father had converted from Catholicism to marry her mother. Mayne’s family moved with some frequency during her early childhood but she spent the greater part of her youth in Kinsale and Cork, ultimately settling in a spacious house dubbed “Rockmahon” in the Blackrock area of Cork when her father was appointed a Resident Magistrate there in 1892. Privately educated, she became proficient in German and French, and enjoyed honing her language skills by translating poetry, some examples of which The Academy (1869–1902) published in 1900 and 1901. Indeed, the linguistic challenges of translation helped to shape her writing, and this art was to prove, just as much as her published fiction and nonfiction, a mainstay of her literary career.

The most pivotal event in her life occurred when Henry Harland, editor of The Yellow Book, wrote to accept one of her stories for the July 1895 issue. Thus began a correspondence that culminated in his invitation in December for her to come to London to be his sub-editor, “Miss Ella D’Arcy, who had hitherto acted in that capacity, having left England for a stay in France” (Lasner 18). Mayne accepted with alacrity and arrived at Euston Station on New Year’s Day, 1896. Although the publication of “A Pen–and–ink Effect” (by “Frances E. Huntley,” a pseudonym she dropped in 1898) in such a high–profile journal constituted an impressive achievement in itself, even more significant for both her professional and her artistic development were the many opportunities that Harland’s offer made possible—not least of which was working closely with a passionate devotee of the quest for “le mot juste” (the best possible phrasing). In a memoir of Harland she wrote many years afterward, Mayne recalled some of his favorite writing precepts posted on the walls of the Yellow Book workroom, such as “Glissez; n’appuyez pas [‘Tread lightly; don’t strain’]” and “Cultivez l’art d’omettre [‘cultivate the art of omission’].” Mayne’s own penchant for French words and phrases was matched by Harland’s; they also shared a reverence for “le maître” (the Master) Henry James. Her assimilation of these doctrines was subsequently testified to by more than a few reviewers’ criticism of the “elliptical” nature of her work, but at this stage of her writing life she focused more on plumbing the nuances of human psychology and fashioning language to capture “exquisite shade[s] of meaning” (Isherwood 249), especially in her characters’ thoughts. In “A Pen-and-ink Effect,” for example, the protagonist is a sensitive, imaginative young woman who abruptly awakens to her fortunate escape from matrimony. The story is largely made up of two interior monologues, one of Mayne’s favourite literary devices. The first conveys the thoughts of an egotistical man writing an unintentionally self–revealing letter, and the second communicates the young woman’s thoughts, before and after reading the letter. The technique’s success derives from Mayne’s ability to convey both sensibilities with exceptional accuracy and insight.

Harland also taught Mayne about proof–correcting, and she was conveniently situated to apply these new skills to two more of her stories, as he had accepted “Points of View” and “Lucille,” which were included as “Two Stories” in the January 1896 issue. Both works are again interior monologues, the first once more by an unworldly, introspective young woman, but this time one who finds herself conflicted about adhering to conventional decorum. In a different vein altogether, and virtually unique in Mayne’s oeuvre, “Lucille” is a humorous satire of male Aesthetes’ objectification, and misreading, of women, and of female artists in particular. This interior monologue takes the form of a confidential one-sided conversation by the garrulous narrator, a narratorial voice that would reappear in various incarnations in Mayne’s future short fiction. Her Yellow Book stories all demonstrate one of her signature skills: to thoroughly inhabit the psyches of her characters, whether they be naïve or narcissistic women, men suffering from self–delusion or slipping into madness, or observant children trying to make sense of adult mysteries.

D’Arcy returned to London at the beginning of April and promptly banished her replacement from the Yellow Book office, while Harland fled to Paris. However, one of the lasting benefits of the few months that were allowed to Mayne was the chance to meet all kinds of literary people—writers, editors, publishers, publishers’ readers—many of whom remained in contact with her throughout her life. Some became good friends, such as fellow Yellow Book contributors Dollie Radford and Olive Custance, as well as the novelist Violet Hunt (1862–1942), who recorded in her diary meeting “Ethelred” shortly after her arrival (Jan. 17, 1896) and who some forty years later made Mayne her literary executor (though it turned out that Mayne predeceased her). Hunt also noted that Mayne was planning to go see Oswald Crawfurd (1834–1909), Hunt’s lover and the editor of Chapman’s Magazine of Fiction (1895–1902), a new monthly that had already published Mayne’s “Her Story and His” in its November 1895 issue; two more of her stories, “His Glittering Hour” and “Unto the Shore of Nothing,” appeared in its pages in 1896 and 1897.

Mayne’s stories in Chapman’s are distinct from those included in The Yellow Book in less faithfully following the injunctions to cultivate the art of omission and to not dwell too heavily upon one’s subject. “Her Story and His” is in two parts comprising the interior monologues of a newly married couple regarding the man’s apparently feigned ignorance of the woman’s legacy when he proposed. “Her story” resembles the ingenuous confidences entrusted to a diary, while “his” is like the increasingly anxious appeals made to an unresponsive oracle. But both notably lack succinctness or suggestion, as do the endings of “His Glittering Hour” and “Unto the Shore of Nothing.” Far from “elliptical,” all three stories might be said to err on the side of overstatement, which Harland deplored. His influence ultimately prevailed, however; as Mayne noted years later in her preface to Browning’s Heroines (1913), “[T]o suggest—to open magic casements—surely is the office of our artists in every sort…” (vii).

In offering the magazine different stories, perhaps Mayne had taken into account that Chapman’s did not aspire to the same standards as The Yellow Book. Its aim was merely to publish “the best fiction” by “the most popular novelists of the day”; indeed, Crawfurd’s editorial tastes, according to Arthur Waugh (1866–1943), his colleague at Chapman and Hall, ran toward the “old–fashioned” and the “reactionary” (Waugh 190–91). Mayne may have similarly appraised Hearth and Home: An Illustrated Weekly Journal for Gentlewomen (1891–1914), for her story “A Mercenary Girl” was included in the issue of April 18, 1895. Edited by Charlotte H. Talbot Coke (1843–1922), the wife of an army officer, the periodical was a promising venue for the tale of a young woman whose jilting of a suddenly impecunious subaltern turns out to be motivated by selflessness. Mayne’s assessments of periodicals were not always so discerning, however.

With the courage imparted by her first Yellow Book credit, and an understandable ambition to appear in such a prestigious journal, she offered a story to Blackwood’s Magazine (1817–1980) in the fall of 1895. But “The One Way” was declined, for its subject is the unpleasant quandary facing the young mistress of a man she senses is tiring of her, and Blackwood’s did not look favourably on stories that dishonoured the institution of marriage. Undaunted, Mayne then offered the story to Harland, who accepted it and included it in The Yellow Book’s April 1896 issue. But before it could be printed, and while Harland was still in Paris, D’Arcy removed Mayne’s story when going over the issue’s page proofs. She also “expunged her name from the Yellow Dwarf’s [Harland’s] mistaken eulogies” (Anderson 24), as she gleefully explained in a letter to Yellow Book publisher John Lane (1854–1925). Although Harland apologized to Mayne via letter from Paris, and fired D’Arcy “by peremptory post–card” (Anderson 26), that was the last she ever heard from him. So she returned to Cork in June, and set to work transforming her newly acquired wealth of material into fiction.

Her first effort did not meet with success. In late 1897 Mayne submitted a novel titled “The Gate of Life” to T. Fisher Unwin, which had a reputation for being receptive to the work of unknown writers. Unwin’s reader Edward Garnett (1868–1937) advised against accepting it, on the grounds that it was untrue to life: “[T]he sketches of social celebrities, artists, famous critics, etc. etc., all the art atmosphere, & art gossip is—well, humbug. There are no such circles as Miss Mayne describes—none.” The manuscript has been lost, so we cannot be certain if the novel was indeed a version of her experiences in the Yellow Book coterie, but if so, it apparently did not, as she might have said, “come off.” It was five more years before Mayne’s first novel, Jessie Vandeleur, finally appeared. Published by the firm of George Allen in 1902, it earned almost universal criticism of its protagonist, variously denounced as a “feminist” and a “monster.” Certainly no heroine by conventional standards, though beautiful and independent–minded, Jessie leaves a small town in Ireland for London when her widowed mother receives a legacy, and enters a circle of artists and writers. She soon appropriates and finishes the manuscript of a novel entrusted to her by her fiancé Hugo, who has gone to Africa with his employer. On its publication she wins acclaim and the admiration of her idol, the author Deyncourt. When her theft is exposed after Hugo’s death, Deyncourt accepts it as proof of her devotion, and the novel ends with the prospect of their marriage.

Despite the spectrum of New Woman novels that had preceded Jessie Vandeleur, the triumph of a protagonist who is more objectionable than sympathetic made for a hard sell, and Mayne had not stinted on evidence revealing Jessie as self–centred and ruthless. Nevertheless, she tried to make her character human rather than evil. For instance, Jessie fumes over being put on a pedestal for her beauty when she knows being recognized for having brains is a more valuable and enduring kind of regard. And in a playful touch, Jessie is shown feeling pained by a badly performed song at a social gathering in her provincial town, a scene designed to evoke empathy among readers who were, like Mayne herself, lovers of good music.

The poor sales of Jessie Vandeleur were even more disappointing in light of the fact that Unwin had published a collection of Mayne’s short stories in 1898 to a more positive reception. When it declined “The Gate of Life” the firm had nevertheless asked to see more of her work, on the basis of Garnett’s praise for her analysis of a woman’s feelings. The manuscript she submitted, provisionally titled Secrets (and later advertised with the subtitle Stories of the Secret Life, though this did not appear in the book itself), met with approval from both Garnett and another Unwin reader, the writer G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936). Garnett again applauded Mayne’s “skilful analysis of feeling” as well as her “keen observation,… natural wit, insight & charm of manner.” Chesterton described the stories as “extremely ‘modern’ in tone… They have all the faults of the self–consciously psychological impressionists… They are not controversial,” he added, “but they bear traces of a certain feminine pessimism which is abroad.” Mayne paid tribute to Harland by choosing as her title his phrase for a writer’s highest goal: The Clearer Vision (Lasner 22). The volume received mixed reviews, of which that in The Athenaeum (1828–1920) is representative: “The writer has real talent, and should apply it to something else than her morbidly introspective heroines. When she has learnt to give up the extensive use of French scraps and disjointed fragments of phrase she may do something really good” (“Short Stories,” Oct. 29, 1898, 606).

The sales of Jessie Vandeleur—and, Mayne felt, its promotion by Allen—were negligible enough that she took the then somewhat unusual step of hiring an agent, Charles Francis Cazenove of the newly established Literary Agency of London. Their ten–year relationship helped to sustain Mayne’s career, but did not bring about a breakthrough in terms of her reputation or her income. So, upon her father’s retirement in 1905, she moved with him to London, where she could more actively promote her work; her mother had died in 1902. The higher cost of living impelled Mayne to seek literary jobs for which she could be paid while working on her next novel and trying to get her stories into periodicals. Cazenove found her a variety of translating projects, including a few sensational books that she chose not to have her name on—predicting that they would “sell like hotcakes,” she nevertheless inquired, only half in jest, if he could get her royalties in lieu of part of her fee. In quick succession she translated Confessions of a Princess (1906), published anonymously but now attributed to the Austro–Hungarian journalist Felix Salten (1869–1945), better known as the author of Bambi; The Diary of a Lost One (1907), also published anonymously but as “edited by” the German writer Margarete Böhme (1867–1939), who is now accepted as the author; and The Struggle for a Royal Child (1907) by the child’s former governess, Ida Kremer. Mayne found the work fairly easy and, as she confessed to Cazenove, the female protagonists of the first two books fascinating, if at times shocking too. In addition, she translated “The Unknown Masterpiece” for Stories by Honoré de Balzac (1909) in The World’s Story Tellers series edited by Arthur Ransome (1884–1967), but none of the volume’s translators were credited.

One of Cazenove’s most significant contributions to Mayne’s career was finding her a supportive publisher in Chapman and Hall, which published her remaining three novels—The Fourth Ship (1908), Gold Lace: A Study of Girlhood (1913), and One of Our Grandmothers (1916), a prequel to The Fourth Ship—and her next three short story collections: Things That No One Tells (1910), Come In (1917), and Blindman (1919). After Chapman and Hall failed to make a profit on Blindman, her final two collections were published by Constable, Nine of Hearts in 1923 and Inner Circle in 1925. The novels concern themselves with the limited roles assigned to women by society, or more precisely, how their fates are governed by the marriage market.

After their publication, Mayne decided to shift her focus from the form of the novel and New Woman themes to short fiction and the intricacies of human relations, or as Ford Madox Ford (1873–1939) put it, “the fine shades of civilised contacts” (Hueffer 36). Her writing underwent a transition to a more modernist aesthetic, a development that was reflected in the periodicals publishing her work; whereas in the early 1910s her stories appeared in such periodicals as the liberal weekly The Nation (1907–1921) and the popular magazines Vanity Fair (1868–1914) and Pall Mall Magazine (1893–1914), in the twenties she published in such modernist journals as The Golden Hind (1922–1924) and The Transatlantic Review (1924). In 1919 her short story “The Man of the House,” about three unmarried sisters and the death of the family feline, won a competition in the country life and topical affairs magazine Land and Water (1866–1920) judged by Arnold Bennett (1867–1931), Joseph Conrad (1857–1924), and J.C. Squire (1884–1958). The otherwise sentimental subject is deftly handled, using language that is spare, straightforward, and dispassionate, its impact achieved through the accretion of carefully observed details. Another superb example of Mayne’s later style is “The Shirt of Nessus,” which appeared in the October 1923 issue of The Golden Hind. Using the familiar device of the interior monologue, it depicts the disintegration of a man’s sanity during a serene afternoon on the banks of the canal in Regent’s Park. Although it is not the same kind of mental breakdown as that suffered by Septimus Smith in Mrs. Dalloway (1925), both characters undergo a similar deterioration in the coherence of their thoughts despite trying desperately to make their experiences intelligible, and both their struggles evoke pathos and horror as reason proves increasingly elusive.

Mayne’s interest in human psychology led naturally to an early interest in the work of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), which led in turn to her friendship with Joan Riviere (1883–1962), one of the founders of the British Psychoanalytical Society and the preeminent English translator of Freud’s work. Riviere invited Mayne to join a team of translators working on The Collected Papers of Sigmund Freud, published by the Hogarth Press in 1924 and 1925. Of the seven essays Mayne translated, her renderings of two of the best known, “‘Civilized’ Sexual Morality and Modern Nervousness” (with E.B. Herford) and “Thoughts for the Times on War and Death,” are still listed as texts on some university syllabi today.

During the 1920s Mayne became involved in two prominent literary organizations. From its founding in 1919 to its wartime hiatus in 1939 she was a member of the Femina Vie Heureuse Prize Committee, serving as its president in 1924 and 1925. And in 1921 she became one of the founding members of P.E.N., the international writers’ organization founded by Catherine Amy Dawson Scott (1865–1934). In the late twenties Mayne began reading French and German books for publishers J.M. Dent and Chatto and Windus to advise on their suitability for the British market. One especially noteworthy book she evaluated for Chatto was Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse (1877–1962), on which she wrote a lengthy and appreciative report, cautioning senior partner Charles Prentice, however, that unless many readers were like T.S. Eliot, the novel would be unlikely to achieve large sales.

Another creative professional outlet for Mayne’s interest in human psychology was the genre of biography. After successfully pitching the idea to Methuen, she began with Enchanters of Men (1909), portraits of foreign women who wielded influence in various ways throughout history. In 1912 she published her monumental 200,000-word biography of Lord Byron, which took her four years to research and write and earned warm and widespread praise, such as, in The Bookman (1891–1934), “her work has superseded all others” (Douglas 188); her 1924 revised edition was described as “by far the best [biography of Byron] in English” (Chew 256). Her life of Lady Byron, published in 1929, was also regarded by reviewers as a model of sensitivity and insight. Leonard Woolf wrote in The Nation and Athenaeum (1921–1931) that it was “one of the most fascinating and important biographies which have appeared for a long time” (July 6, 1929, 478). To Mayne’s great disappointment she had to abandon a biography of Lady Caroline Lamb when another was published in 1932, but she made the best of it by applying her research to what was to become her last published work, a biography of Lamb’s slightly less notorious mother, Lady Bessborough, which came out in 1939.

In September 1940 the house in Twickenham where she and her sister were living was bombed, and Mayne was hospitalized for six weeks. After she recovered they went to live in Torquay, in Devonshire, to be near their brothers, but both died the following April, Mayne on April 30, at the age of 76. She was singularly fortunate in having been mentored by Henry Harland and welcomed into The Yellow Book’s inner circle, however briefly, and in having shared the literary preoccupations of what Ford Madox Ford called “the Yellow Book School”: a concern with “form, with the expression of fine shades, with continental models and exact language” (Hueffer 36). Her unique legacy was to bridge the fin de siècle and the modernist era by uniting formal and stylistic innovation with a highly refined attentiveness to word and phrase in a lifelong quest to probe the infinite complexities of human behavior and give expression to the life of the mind.

©2021, Susan Winslow Waterman

Susan Winslow Waterman has been researching Mayne since completing her master’s thesis, “Ethel Colburn Mayne: Unheralded Pioneer of Modernism,” at Georgetown University in 1995. She is currently working on a biography of Mayne and editing a collection of her letters.

Selected Publications by Mayne

- “As a Lamb….” Pall Mall Magazine, vol. 47, no. 214, Feb. 1911, pp. 209–12.

- “Atherley.” The Nation, vol. 8, no. 16, Jan. 14, 1911, pp. 643–44.

- “A Bit of Her.” Life and Letters, vol. 11, no. 63, March 1935, pp. 692–96.

- “Black Magic.” Westminster Gazette, April 3, 1923, p. 9.

- Blindman. London: Chapman and Hall, 1919.

- Browning’s Heroines. London: Chatto and Windus, 1913.

- Byron (2 vols.). London: Methuen, 1912. New York: Scribner’s, 1912. Revised ed. (1 vol.). London: Methuen, 1924. New York: Scribner’s, 1924.

- The Clearer Vision. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1898.

- “The Colonel.” Pall Mall Magazine, vol. 49, no. 229, May 1912, pp. 679–85.

- Come In. London: Chapman and Hall, 1917.

- “Dialogue in a Cab.” The Transatlantic Review, vol. 1, no. 2, Feb. 1924, pp. 41–45.

- “The Difference.” The Transatlantic Review, vol. 1, no. 5, May 1924, pp. 318–20.

- “Dispossession.” The Nation, vol. 7, no. 18, July 30, 1910, pp. 630–31.

- “Four Dances.” The Nation, vol. 7, no. 24, Sept. 10, 1910, pp. 834–36.

- The Fourth Ship. London: Chapman and Hall, 1908.

- Gold Lace: A Story of Girlhood. London: Chapman and Hall, 1913.

- “Henry James (As seen from the ‘Yellow Book’).” The Little Review, vol. 5, no. 4, Aug. 1918, pp. 1–4.

- “Her Story and His.” Chapman’s Magazine of Fiction, vol. 2, no. 7, Nov. 1895, pp. 286–92. [pseud. Frances E. Huntley]

- “His Glittering Hour.” Chapman’s Magazine of Fiction, vol. 3, no. 12, April 1896, pp. 439–48. [pseud. Frances E. Huntley]

- “Humour.” The Golden Hind, vol. 2, no. 8, July 1924, pp. 19–20.

- “I heard the thrush to–day” (poem). The Academy and Literature, vol. 64, no. 1606, Feb. 21, 1903, p. 186.

- Inner Circle. London: Constable, 1925. New York: Harcourt, 1925.

- “The Invitation to the Valse.” Pall Mall Magazine, vol. 40, no. 176, Dec. 1907, pp. 644–52.

- Jessie Vandeleur. London: George Allen, 1902.

- The Life and Letters of Anne Isabella, Lady Noel Byron. London: Constable, 1929. New York: Scribner’s, 1929.

- “The Literary Week” (includes translations by Ethel Colburn Mayne of three poems by Heinrich Heine). The Academy, vol. 60, no. 1500, Feb. 2, 1901, p. 96.

- “The Lower Road.” Atalanta’s Garland: Being the Book of the Edinburgh University Women’s Union. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1926, pp. 33–51.

- “The Man of the House.” Land and Water, vol. 74, no. 2979, June 12, 1919, pp. 17–19.

- “May Day at Sea” (poem). The Academy and Literature, vol. 62, no. 1566, May 10, 1902, p. 491.

- “A Mercenary Girl.” Hearth and Home, vol. 8, no. 205, April 18, 1895, p. 845. [pseud. Frances E. Huntley]

- Nine of Hearts. London: Constable, 1923. New York: Harcourt, 1923.

- One of Our Grandmothers. London: Chapman and Hall, 1916.

- “Our Weekly Competition. Result of No. 50 (New Series).” Translation by “E.C.M., Cork” of verse by Victor Hugo. The Academy, vol. 59, no. 1479, Sept. 8, 1900, p. 199.

- “A Pen–and–ink Effect.” The Yellow Book 6 (July 1895): 286–91. [pseud. Frances E. Huntley]. Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2010–2014. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://1890s.ca/YBV6_huntley_pen/

- Prentice, Charles, Letter to. April 26, 1928. CW 41/1. MS. 2444, Chatto and Windus Ltd. Archive. Special Collections, University of Reading.

- “Reassurance.” The Nation, vol. 13, no. 9, May 31, 1913, pp. 342–43.

- A Regency Chapter: Lady Bessborough and Her Friendships. London and New York: Macmillan, 1939.

- The Romance of Monaco and Its Rulers. London: Hutchinson, 1910. New York: John Lane, 1910.

- “The Shirt of Nessus.” The Golden Hind, vol. 2, no. 5, Oct. 1923, pp. 15–20.

- “The Spell of Proust.” Marcel Proust: An English Tribute, edited by C.K. Scott Moncrieff, London: Chatto and Windus, 1923, pp. 90–95.

- “Stripes.” The Golden Hind, vol. 1, no. 1, Oct. 1922, pp. 31–34.

- Things That No One Tells. London: Chapman and Hall, 1910.

- “The Tribute” (poem). The Golden Hind, vol. 1, no. 3, April 1923, p. 24.

- [Tribute to Joseph Conrad]. The Transatlantic Review, vol. 2, no. 3, Sept. 1924, pp. 345–47.

- “Two Stories” [comprising “Points of View” and “Lucille”]. The Yellow Book 8 (Jan. 1896): 47–60. [pseud. Frances E. Huntley]. Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2010–2014. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://1890s.ca/YBV8_huntley_two_stories/

- “Ugliness.” The New Statesman, Sept. 27, 1930, pp. 761–62.

- “Unto the Shore of Nothing.” Chapman’s Magazine of Fiction, vol. 7, no. 1, May 1897, pp. 34–39. [pseud. Frances E. Huntley]

- “Vanity.” Vanity Fair, July 3, 1912, p. 15.

- “Your New Hat.” Pall Mall Magazine, vol. 43, no. 189, Jan. 1909, pp. 72–77.

Selected Publications about Mayne

- Abu-Manneh, Bashir. Fiction of The New Statesman, 1913–1939. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2011, 130–31.

- Adams, Jad. “Mayne, Ethelind Frances Colburn.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www.oxforddnb.com/

- Anderson, Alan. Ella D’Arcy: Some Letters to John Lane. Edinburgh: Tragara Press, 1990.

- Chesterton, G.K. Reader’s report for T. Fisher Unwin on Secrets [The Clearer Vision] by Ethel Colburn Mayne. Report No. 24, April 13, 1898. Berg Collection, New York Public Library.

- Chew, Samuel C. “Byron the Man” (review of Mayne’s Byron and a French biography of Byron). The Saturday Review of Literature, vol. 2, no. 14, Oct. 31, 1925, p. 256.

- D’hoker, Elke. “Daughters, Death and Despair in Ethel Colburn Mayne’s Short Stories.” Irish Women Writers at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, edited by Kathryn Laing and Sinéad Mooney, Brighton: Edward Everett Root, 2020, pp. 143–54.

- D’hoker, Elke. “A Forgotten Irish Modernist: Ethel Colburn Mayne.” Irish Modernisms: Gaps, Conjectures, Possibilities, edited by Paul Fagan, John Greaney, and Tamara Radak. London: Bloomsbury, 2021, pp. 29–41.

- D’hoker, Elke. “Introduction.” Ethel Colburn Mayne: Selected Stories. Brighton: Edward Everett Root, 2021, pp. 1–37.

- D’hoker, Elke. “Performing Irishness: Ethel Colburn Mayne’s ‘The Happy Day.’” Stage Irish: Performance, Identity, Cultural Circulation, edited by Paul Fagan, Dieter Fuchs, and Tamara Radak. Trier: WVT, forthcoming.

- Douglas, George. “The New Life of Byron.” The Bookman, vol. 43, no. 255, Dec. 1912, pp. 188–89.

- Garnett, Edward. Reader’s report for T. Fisher Unwin on “The Gate of Life” by Ethel Colburn Mayne. Report No. 2125, Nov. 22, 1897. Berg Collection, New York Public Library.

- Garnett, Edward. Reader’s report for T. Fisher Unwin on Secrets [The Clearer Vision] by Ethel Colburn Mayne. Report No. 23, May 19, 1898. Berg Collection, New York Public Library.

- Hueffer [Ford], Ford Madox, Thus to Revisit: Some Reminiscences. London: Chapman and Hall, 1921. New York: Dutton, 1921, pp. 36–37.

- Hunt, Violet. Unpublished AM diary, 1894–96. Box 12, folder 1. Collection 4607, Violet Hunt Papers, 1858–1962. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY.

- Isherwood, Christopher. Introduction to “The Man of the House.” Great English Short Stories, edited by Christopher Isherwood. New York: Dell, 1957, pp. 249–50.

- Lasner, Mark Samuels. “Ethel Colburn Mayne’s ‘Reminiscences of Henry Harland.’ Bound for the 1890s: Essays on Writing and Publishing in Honor of James G. Nelson, edited by Jonathan Allison, High Wycombe: Rivendale Press, 2006, pp. 15–26.

- Mansfield, Katherine. “Dragonflies” (review of Mayne’s Blindman and two other books. Novels and Novelists, edited by J. Middleton Murry. New York: Knopf, 1930, pp. 142–44. Reprinted from The Athenaeum, no. 4680, Jan. 9, 1920, p. 48.

- “Short Stories” (anonymous review of The Clearer Vision). The Athenaeum, no. 3705, Oct. 29, 1898, p. 606.

- Stetz, Margaret D. and Mark Samuels Lasner. The Yellow Book: A Centenary Exhibition. Cambridge, Mass.: The Houghton Library, 1994, pp. 18–19.

- Waterman, Susan. “Ethelind Frances Colburn Mayne.” An Encyclopedia of British Women Writers. Rev. ed., edited by Paul Schlueter and June Schlueter, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998, pp. 441–42.

- Waterman, Susan Winslow. “Ethel Colburn Mayne.” Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 197, Late–Victorian and Edwardian British Novelists: Second Series, edited by George M. Johnson. Detroit: Gale, 1999, pp. 187–201.

- Waterman, Susan Winslow. “Ethel Colburn Mayne: Unheralded Pioneer of Modernism.” Unpublished master’s thesis. Georgetown University, 1995.

- Waugh, Arthur. A Hundred Years of Publishing: Being the Story of Chapman and Hall, Ltd. London: Chapman and Hall, 1930, pp. 190–91.

- Windholz, Anne M. “The Woman Who Would Be Editor: Ella D’Arcy and the Yellow Book.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 29, no. 2, Summer 1996, pp. 116–30.

- Woolf, Leonard. “Lady Byron” (review of The Life and Letters of Anne Isabella, Lady Noel Byron). The Nation and Athenaeum, July 6, 1929, p. 478.

MLA citation:

Waterman, Susan Winslow. “Ethel Colburn Mayne [aka Frances E. Huntley] (1865-1941),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/mayne_bio/