Henry James

(1843 – 1916)

“We must feel everything, everything we can. We are here for that,” Henry James advises in The Tragic Muse (1890). This aphorism encapsulates his important contribution to the culture of the 1890s. However, we must take care not to misread James’s injunction as a bold declaration that hedonism is the way to go in life, but rather, as a private invitation that ripples with ambiguity. This doubleness is the hallmark of James’s life as a citizen of two countries and a novelist who, in the words that mark his grave in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was the “interpreter of his generation on both sides of the sea.”

Born in 1843 in New York City, James spent much of his childhood and adolescence in Europe, an experience that profoundly shaped his fiction, as well as his transatlantic, cosmopolitan worldview. After a stint at Harvard Law School, James took to writing. By his 25th year, he had published more than 53 reviews and 12 short stories. During the 1870s and 1880s, James divided his time between Cambridge MA, the Continent, and England, becoming familiar with leading men and women of letters including Ivan Turgenev (1818-1883), Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), Émile Zola (1840-1902), and Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893). By the age of 35, James had published several novels ( Watch and Ward (1871), Roderick Hudson (1875), The American (1877), and The Europeans (1878) as well as critical works and travel writing, including French Poets and Novelists (1875) and Transatlantic Sketches (1878).

“Daisy Miller,” James’s story of adolescent love on the grand tour, made him a household name. Propelled to the notice of British and American audiences, James was celebrated by William Dean Howells (1837-1920) as the creator of “the international novel,” the heir of Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, Nathaniel Hawthorne and George Eliot, and the future of Anglo-American literature. “An enlightened criticism will recognize in Mr. James’s fiction a metaphysical genius working to aesthetic results,” Howells proclaimed.

Despite a number of personal setbacks including the death of both his parents in quick succession and unsatisfactory earnings from his books, James remained highly productive during the 1880s. He refined his artistic philosophy, famously advising aspiring authors to “try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost” in The Art of Fiction. His engagement with Aestheticism became more palpable, and he began to experiment with a style that would incorporate romance, realism, and literary impressionism.

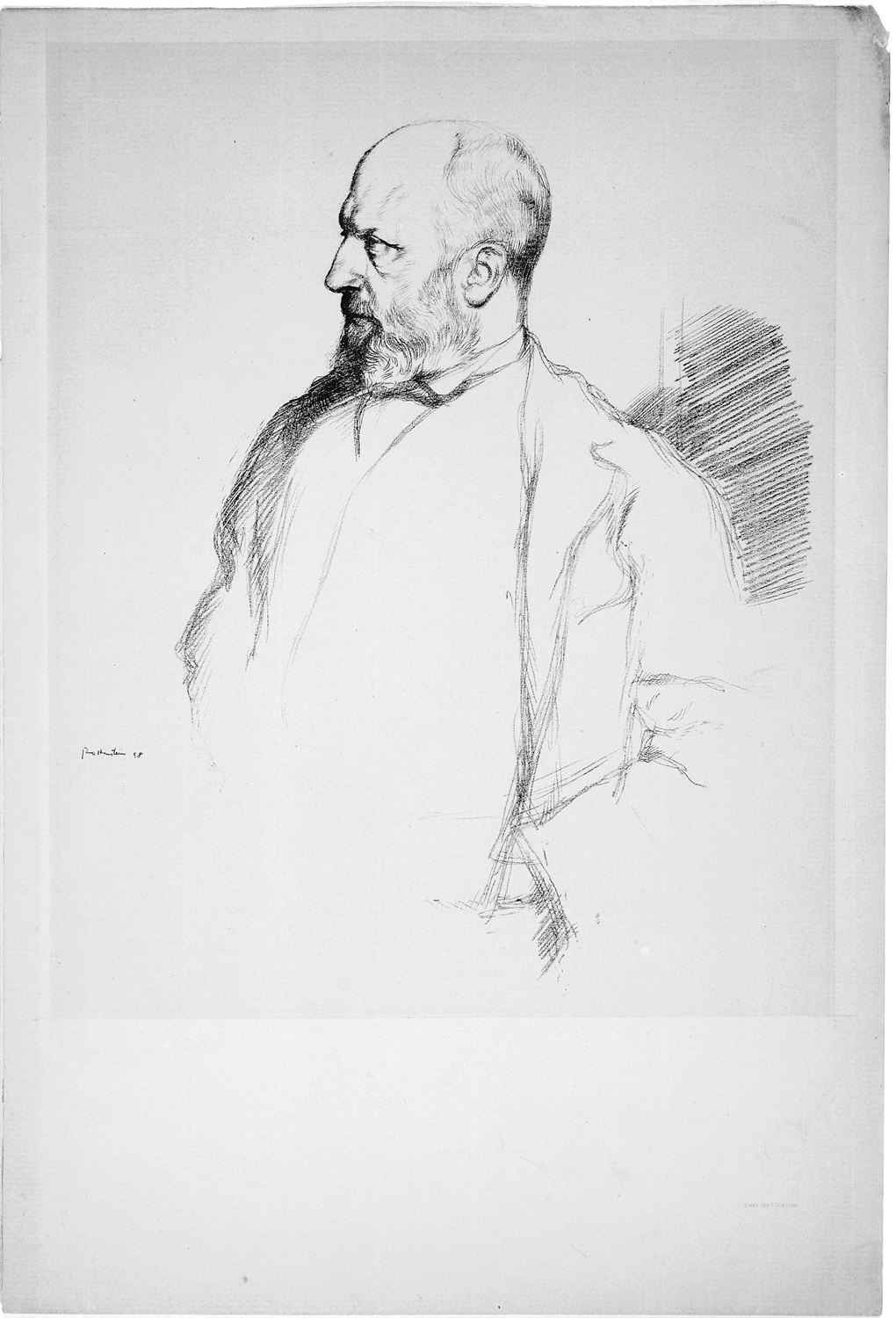

Despite his distaste for The Yellow Book circle, James published four stories in the magazine. James’s “The Death of the Lion” took the lead position in the first issue, published in April 1894. “I hate too much the horrid aspect & company of the whole publication,” James said of The Yellow Book’s decadent coterie. John Singer Sargent’s portrait of James was nevertheless reproduced in the magazine in July 1894, and the October 1895 issue included “A Few Notes on Mr. Henry James,” an essay that judged him to be “too analytical.”

With a view to amending his financial situation and tapping his lifelong fascination with the theatre, he began to write plays in the 1890s. Though some were produced ( The American, Guy Domville ), these are among James’s least rewarding works. In 1895, the unsuccessful run of Guy Domville, which dramatises a novice’s dilemma between the Church and family duty, crushed him.

The experience of stage production no doubt influenced his decision, in February 1897, to begin composing by dictation, a method that altered his style significantly and endowed it with an elliptic, impressionistic, rhythmic, colloquial, and digressive quality that is immediately recognisable as “late James.” In What Maisie Knew (1897), James’s first dictated novel, a cake becomes “a wonderful delectable mountain with geological strata of jam” and a beloved stepfather’s hand is “encased in a pearl-grey glove ornamented with the thick black lines that, at her mother’s, always used to strike her as connected with the way the bestitched fists of the long ladies carried, with the elbows well out, their umbrellas upside down.” It is appropriate that the sensitive child-heroine of What Maisie Knew should think of baked goods as summits of pleasure, and that she should remember the details of the hands that have scolded her. What makes these phrases uniquely Jamesian is not merely their descriptive thickness, or what cynics would call difficulty for difficulty’s sake, but a style that exploits the ambiguity of meaning, perspective, and narrative point of view to develop Maisie’s experience.

James’s most widely read and psychologically intriguing story, “The Turn of the Screw” (1898), similarly uses this mode to shift subtly between the story’s multiple layers and possible interpretations, each one bringing the reader closer to a more chilling reality. The result, as Mark Seltzer notes in Henry James and the Art of Power , is that the story’s “advertised ambiguities” force the reader to make an impossible “‘choice’ between ghost and madness narratives […] by repeating in another register, this inside – or perhaps too-evident – story of desire, knowledge and power.” James continued to exploit the potential of this technique in his late novels, including The Wings of the Dove (1902), The Ambassadors (1903, which includes James’s oft-quoted aphorism “Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to”), and The Golden Bowl (1904).

By the early 1900s, James had been resident in England for several decades. Returning to the United States in 1904-05, he was struck by the way his native land had grown and disappointed at the ways in which it had degenerated. James’s biographer, Leon Edel, notes that The American Scene (1905-06) “was written with all the passion of a[n American] patriot.” A decade later James nevertheless took the oath of allegiance to King George V, surrendered his American passport, and announced excitedly “civis Britannicus sum!”. He received the British Order of Merit in 1916 and died the same year in London. He is buried alongside his family in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

© 2010, Michèle Mendelssohn

Michèle Mendelssohn is the author of Henry James, Oscar Wilde and Aesthetic Culture (Edinburgh UP and Columbia UP, 2007). She is University Lecturer at Oxford University.

Selected Publications by James

- Autobiography: A Small Boy and Others, Notes of a Son and Brother, the Middle Years. Ed. Frederick W. Dupee. London: W.H. Allen, 1956

- The Complete Plays of Henry James. Ed. Leon Edel. London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1949.

- Daisy Miller. New York and London: Harper, 1906.

- Henry James: A Life in Letters. Ed. Philip Horne. London: Allen Lane, 1999.

- Henry James: Literary Criticism. Ed. Mark Wilson and Leon Edel. 2 vols. New York: Library of America, 1984.

- Theory of Fiction: Henry James. Ed. James Edwin Miller. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1972.

Selected Publications about James

- Edel, Leon. Henry James: A Life. New York: Harper & Row, 1985.

- Freedman, Jonathan, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Henry James. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1998.

- Graham, Wendy. Henry James’s Thwarted Love. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1999.

- Haralson, Eric. Henry James and Queer Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003.

- James, Henry. The Art of Criticism: Henry James on the Theory and the Practice of Fiction. Ed. Griffin, William Veeder and Susan M. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1986.

- Ozick, Cynthia. Quarrel and Quandary: Essays. New York: Vintage, 2000.

- Salmon, Richard. Henry James and the Culture of Publicity. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997.

- Seltzer, Mark. Henry James and the Art of Power. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1984.

- Tintner, Adeline. The Cosmopolitan World of Henry James: An Intertextual Study. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1991.

- Wadsworth, Sarah A. “Innocence Abroad: Henry James and the Re-Inventions of the American Woman Abroad.” Henry James Review 22 2 (2001): 107-27.

- Wilson, Edmund. “The Ambiguity of Henry James.” The Triple Thinkers. London: Penguin, 1962.

MLA citation:

Mendelssohn, Michèle. “Henry James (1843-1916),” Y90s Biographies, 2010. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/james_bio.