XML PDF

The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume I April 1894

Contents

Letterpress

I. The Death of the Lion .. By Henry

James .. Page 7

II. Tree-Worship .. Richard Le Gallienne .. 57

III. A Defence of Cosmetics .. Max

Beerbohm .. 65

IV. Δαιμονζσμενος .. Arthur Christopher Benson .. 83

V. Irremediable .. Ella D’Arcy ..

87

VI. The Frontier .. William

Watson .. 113

VII. Night on Curbar

Edge

VIII. A Sentimental Cellar .. George Saintsbury .. 119

IX. Stella Maris .. Arthur Symons .. 129

X. Mercedes .. Henry

Harland .. 135

XI. A Broken

Looking-Glass

XII. Alere Flammam .. Edmund Gosse ..

153

XIII. A Dream of November

XIV. The Dedication .. Fred M.

Simpson .. 159

XV. A Lost Masterpiece ..

George Egerton .. 189

XVI. Reticence in Literature .. Arthur Waugh ..

201

XVII. Modern Melodrama .. Hubert Crackanthorpe .. 223

XVIII. London .. John

Davidson .. 233

XIX. Down-a-down. ..

235

XX. The Love-Story of Luigi Tansillo ..

Richard Garnett, LL.D. . 235

XXI. The Fool’s Hour .. John Oliver

Hobbes

and George Moore .. 253

Pictures

The Yellow Book, — Vol. I.— April, 1894.

Pictures

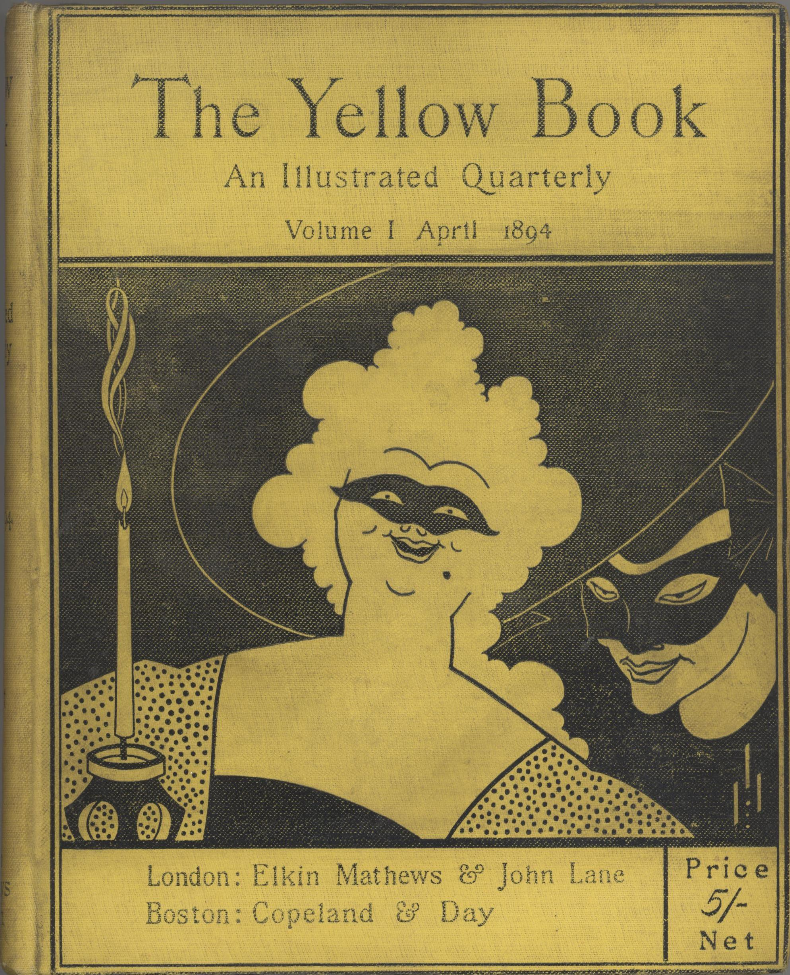

Front Cover, by Aubrey Beardsley

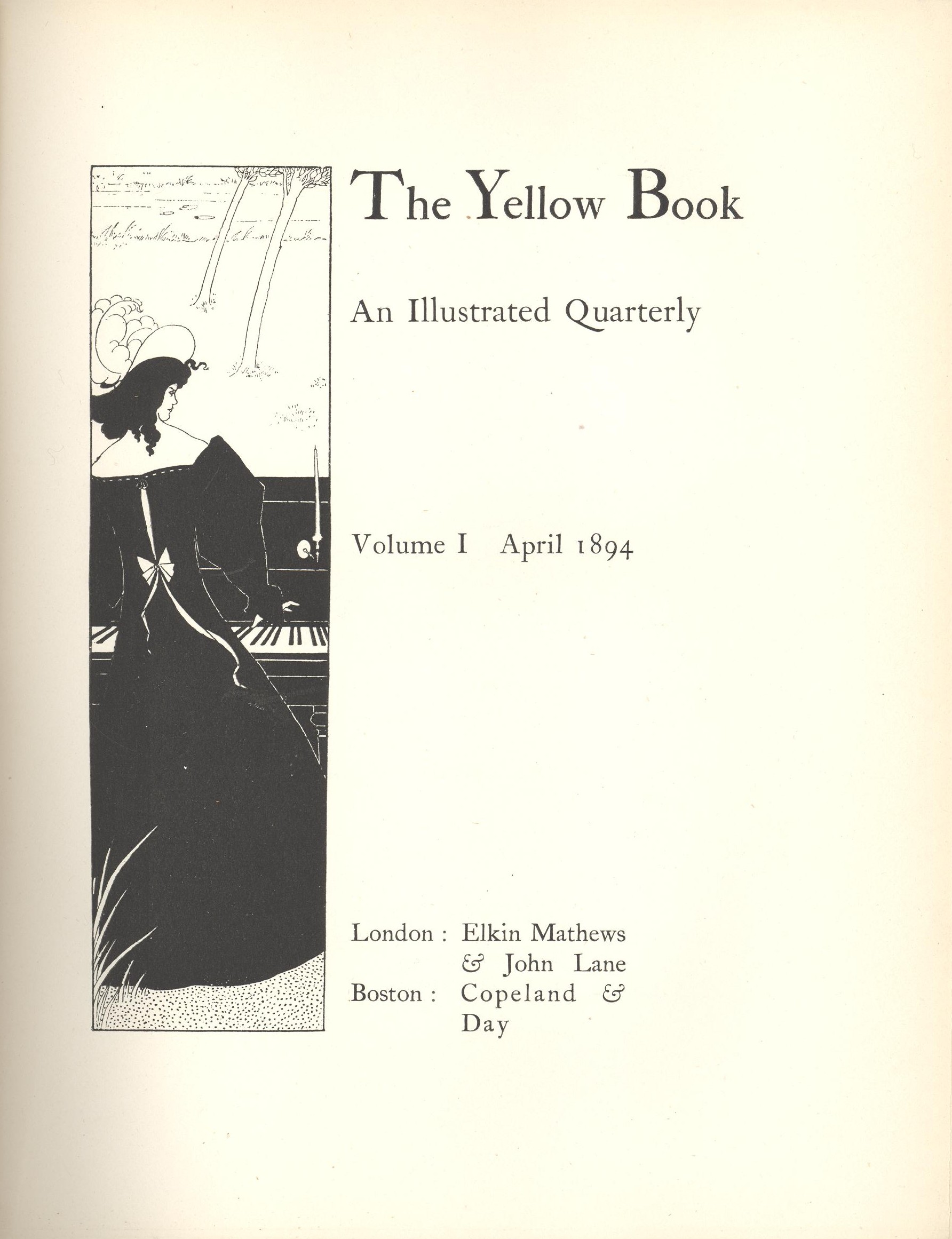

Title Page, by Aubrey Beardsley

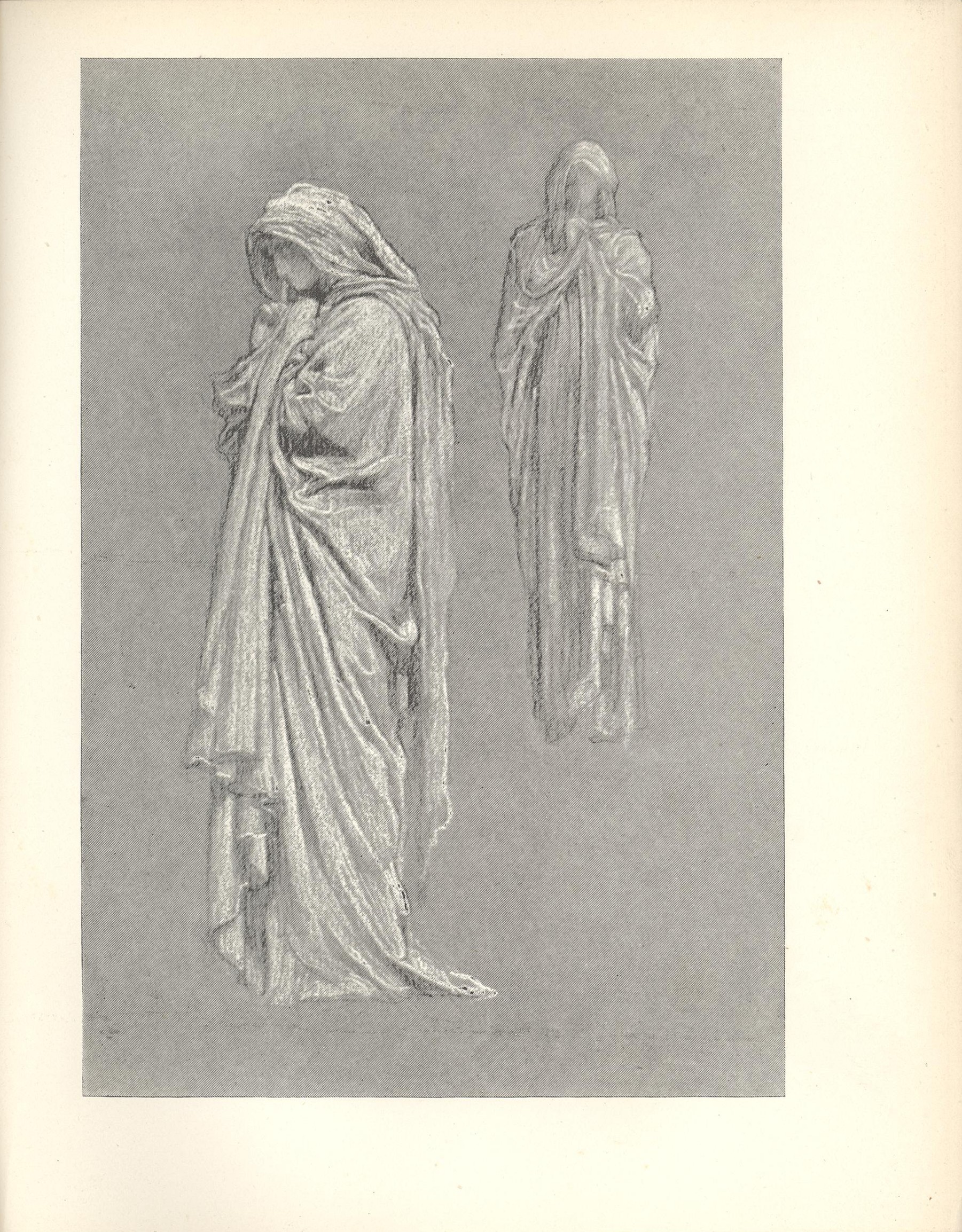

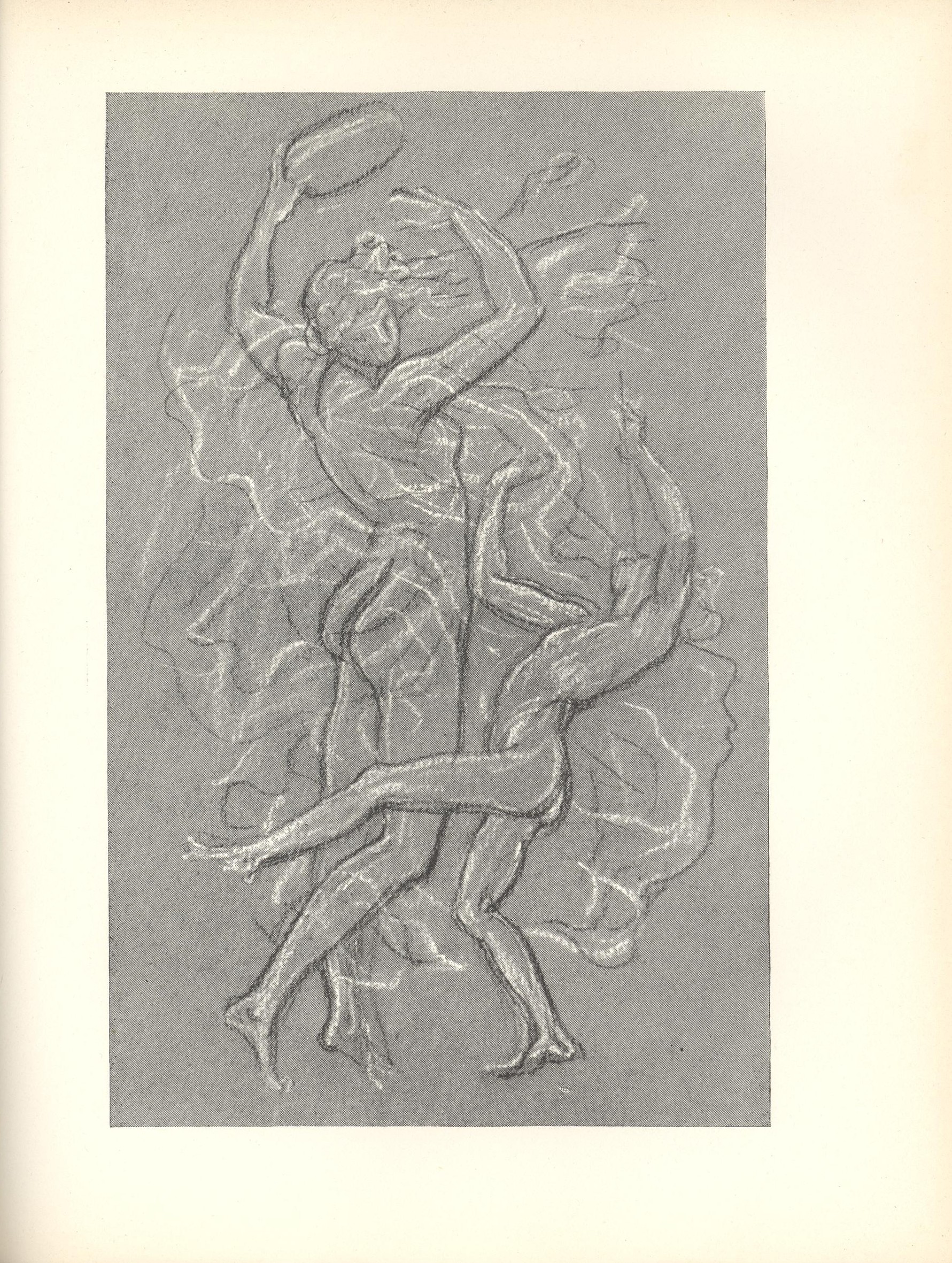

I. A Study .. By Sir Frederic

Leighton,

P.R.A.

Frontispiece

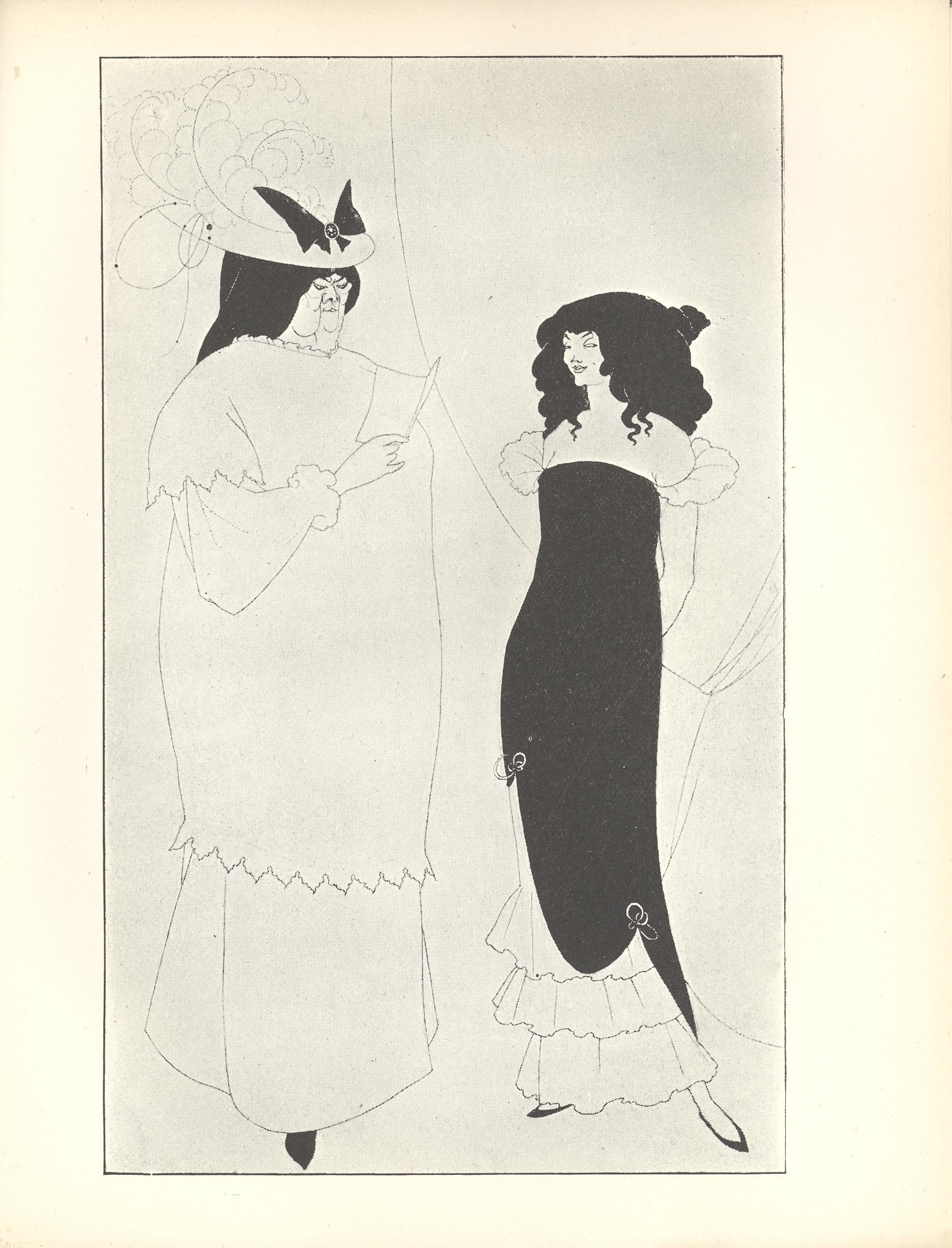

II. L’Education Sentimentale .. Aubrey

Beardsley .. Page 55

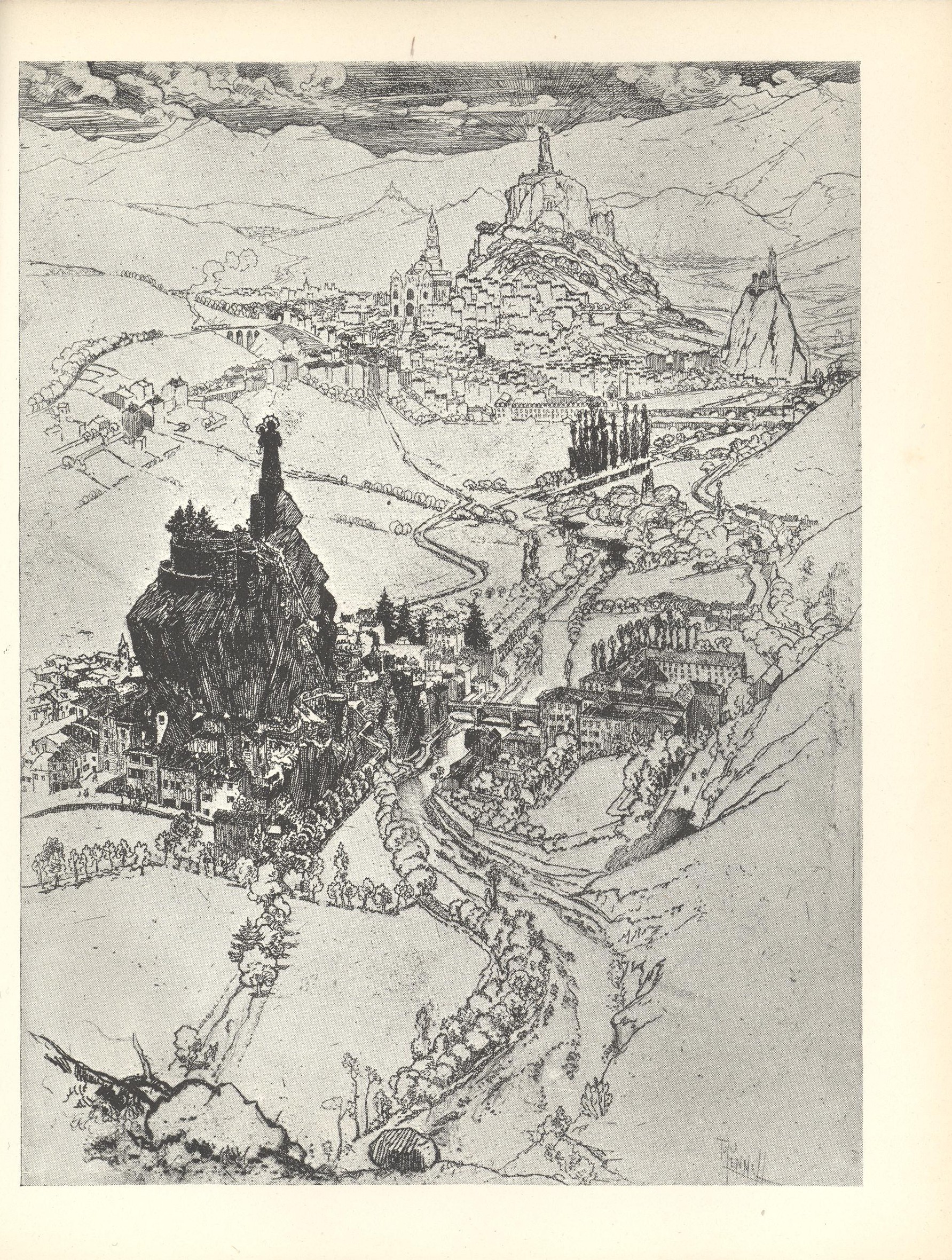

III. Le Puy en Velay .. Joseph Pennell .. 63

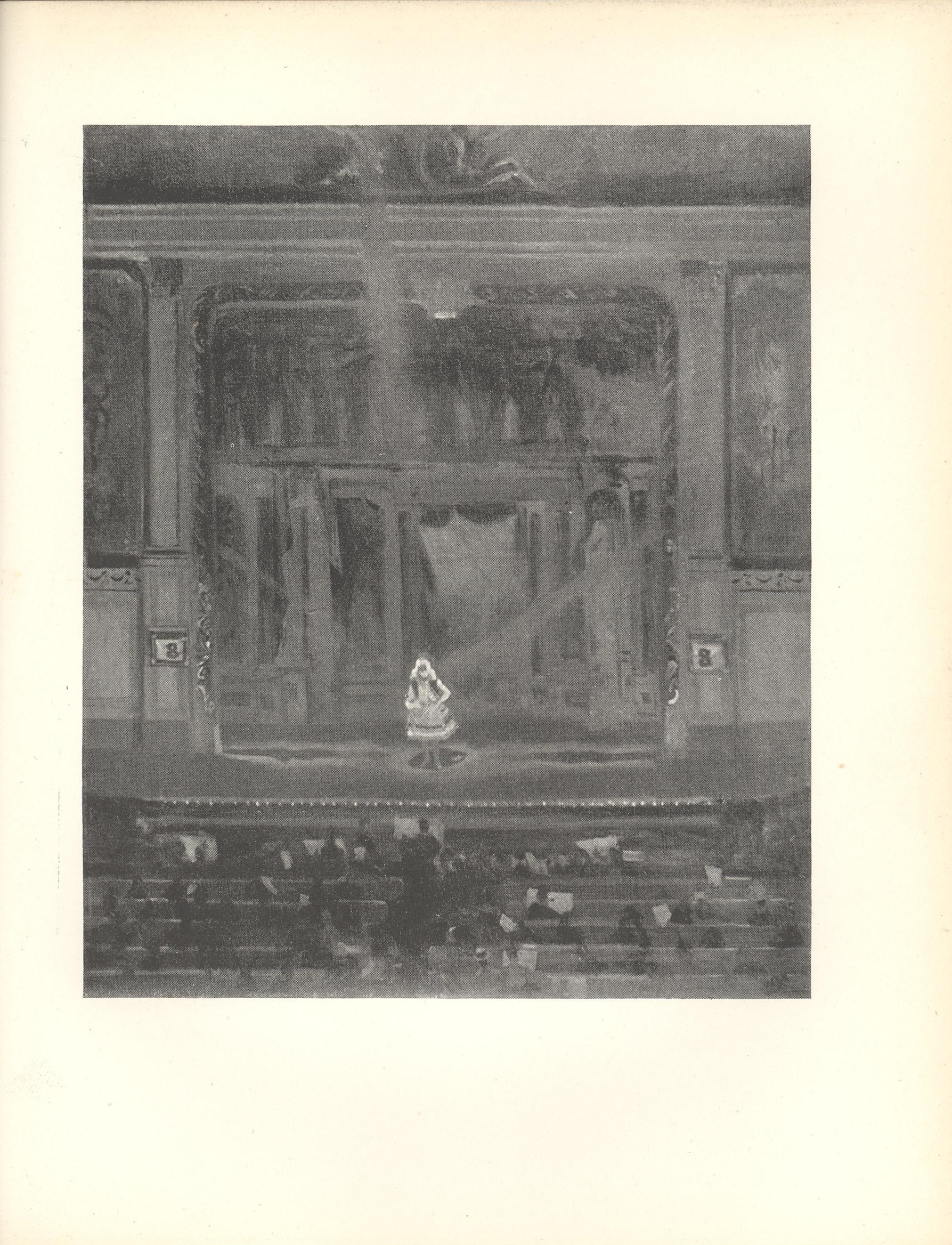

IV. The

Old Oxford Music Hall .. Walter Sickert .. 85

V. Portrait

of a Gentleman .. Will Rothenstein .. 111

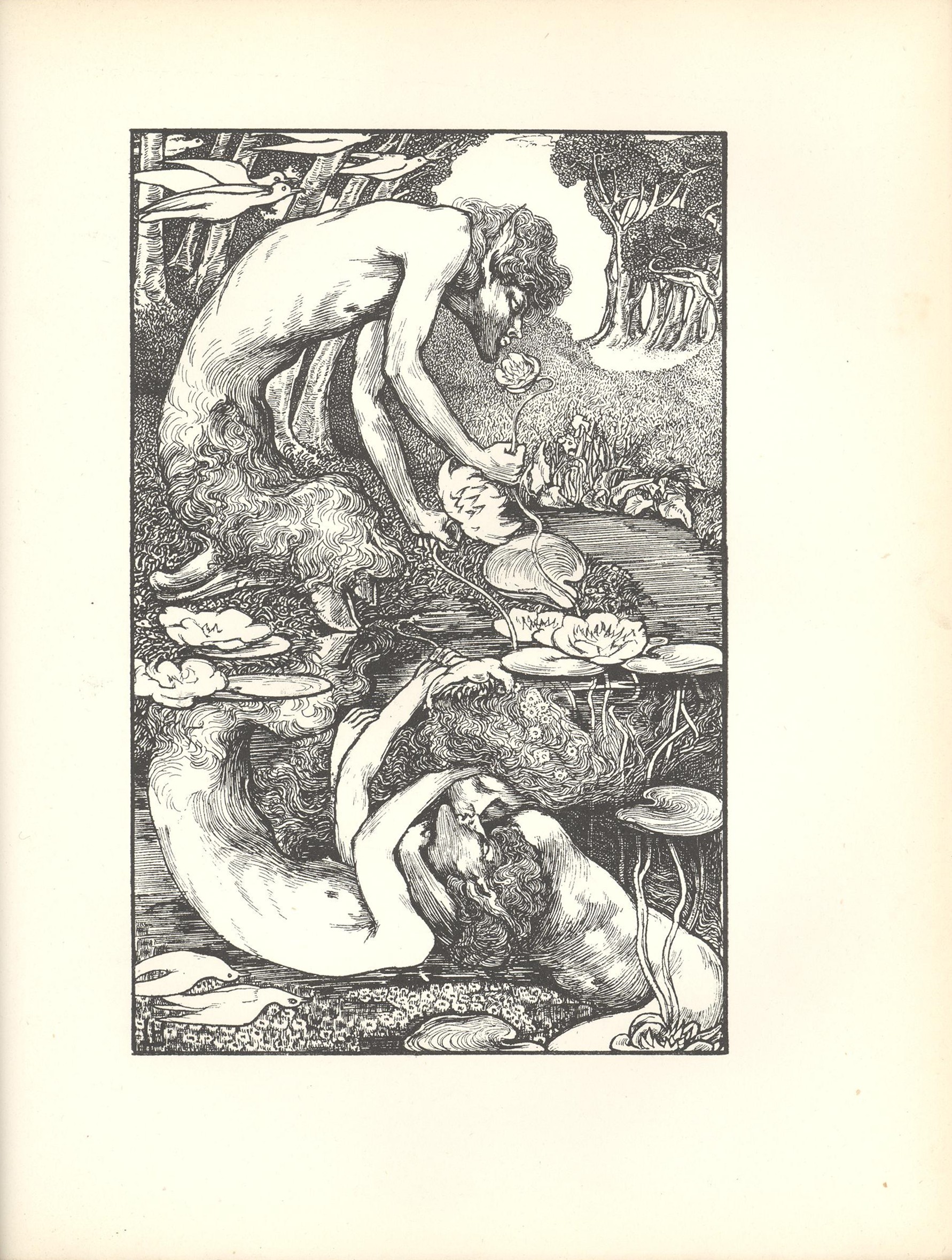

VI.

The Reflected Faun .. Laurence

Housman .. 117

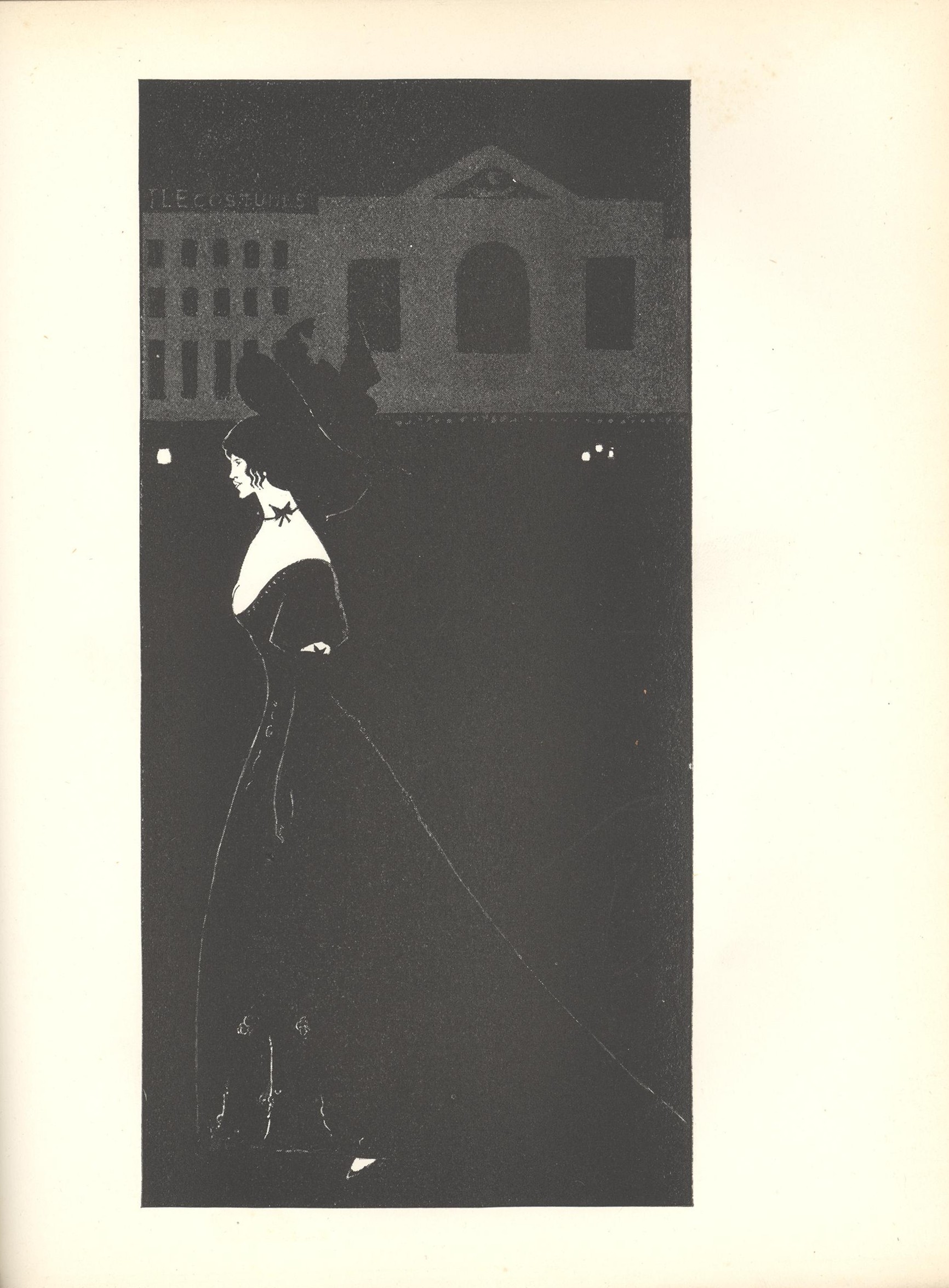

VII. Night Piece .. Aubrey Beardsley .. 127

VIII. A

Study … Sir Frederic Leighton,

P.R.A. .. 133

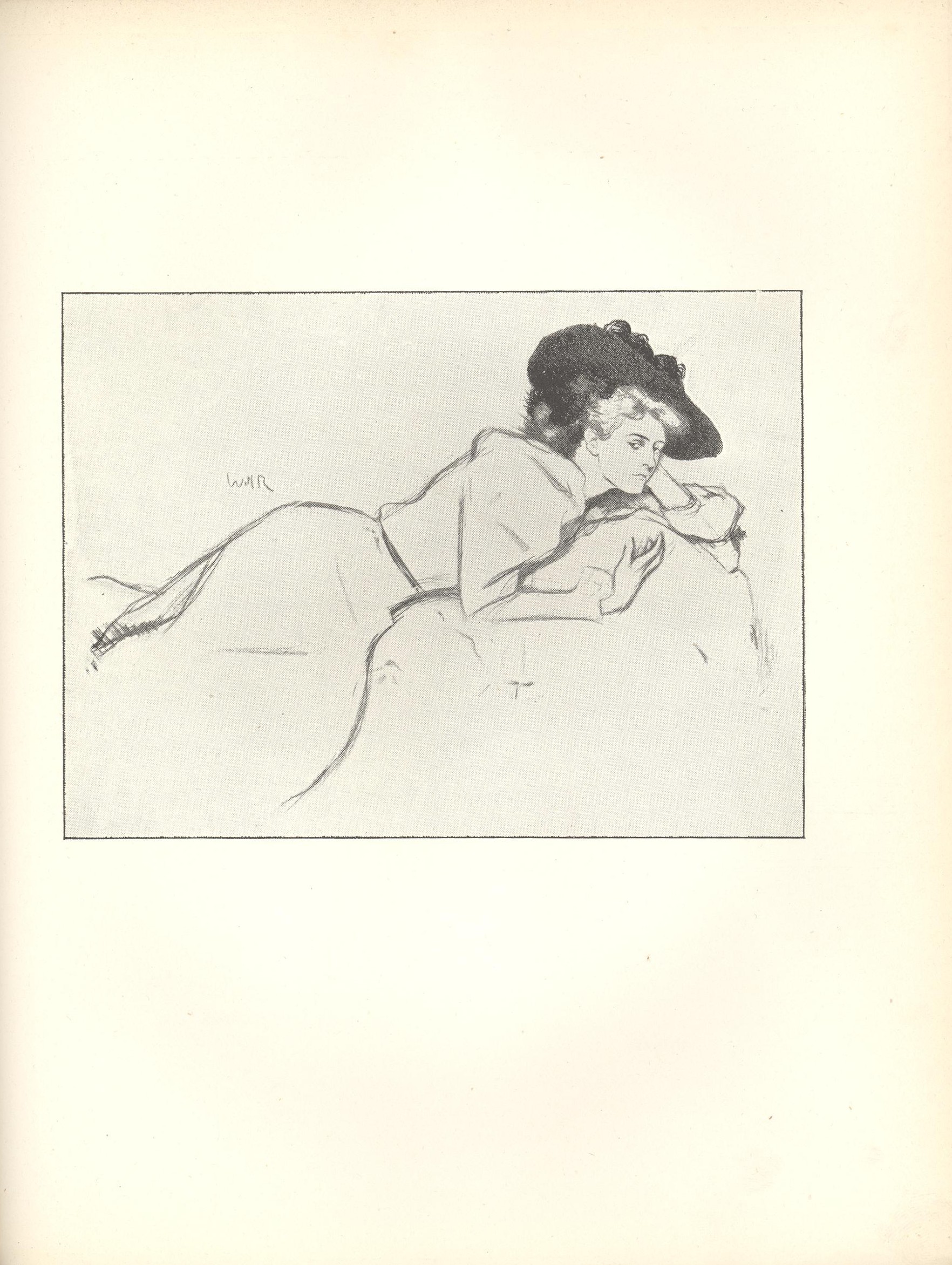

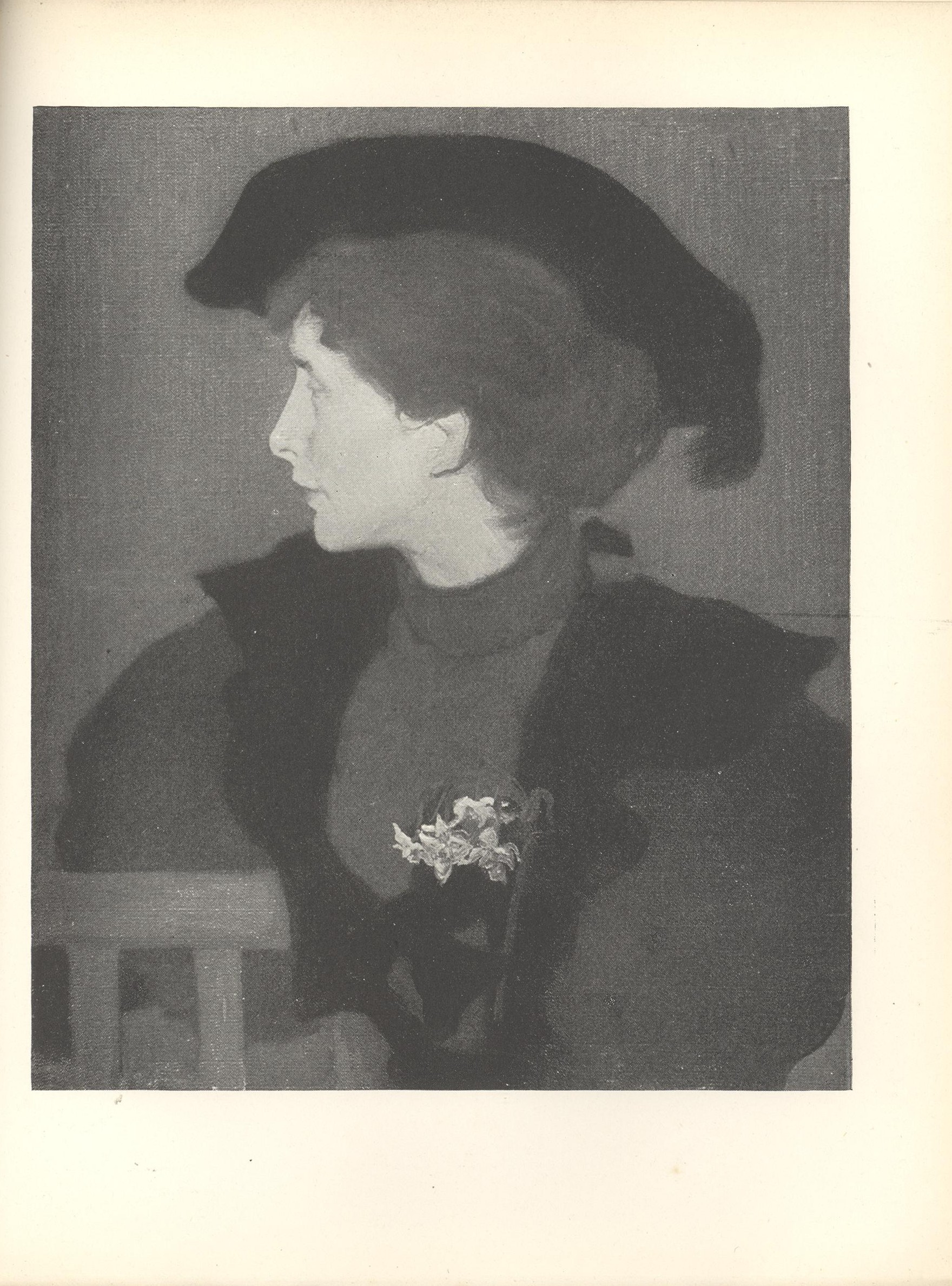

IX. Portrait of a Lady ..Will

Rothenstein .. 151

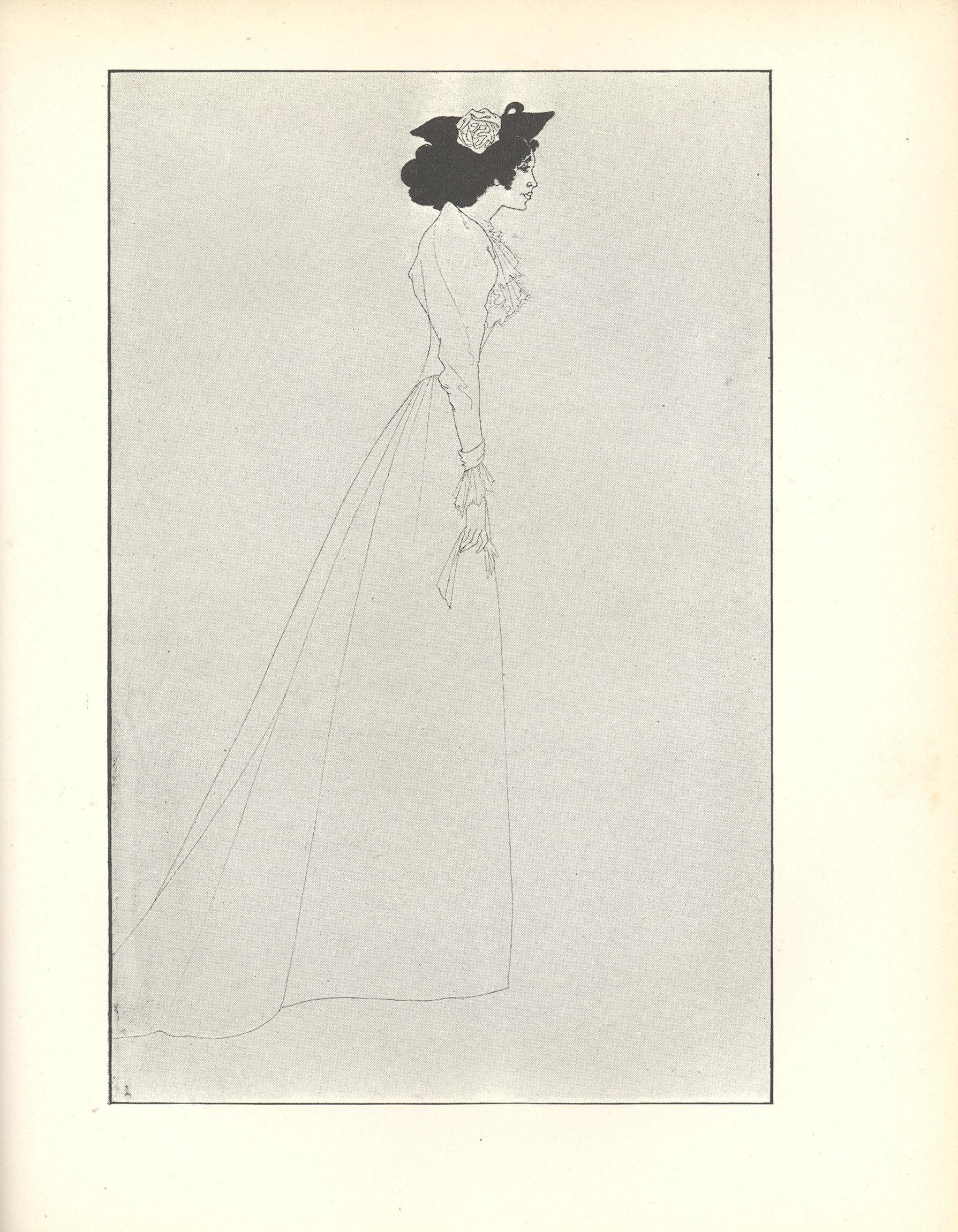

X. Portrait of Mrs. Patrick Campbell .. Aubrey Beardsley .. 157

XI. The

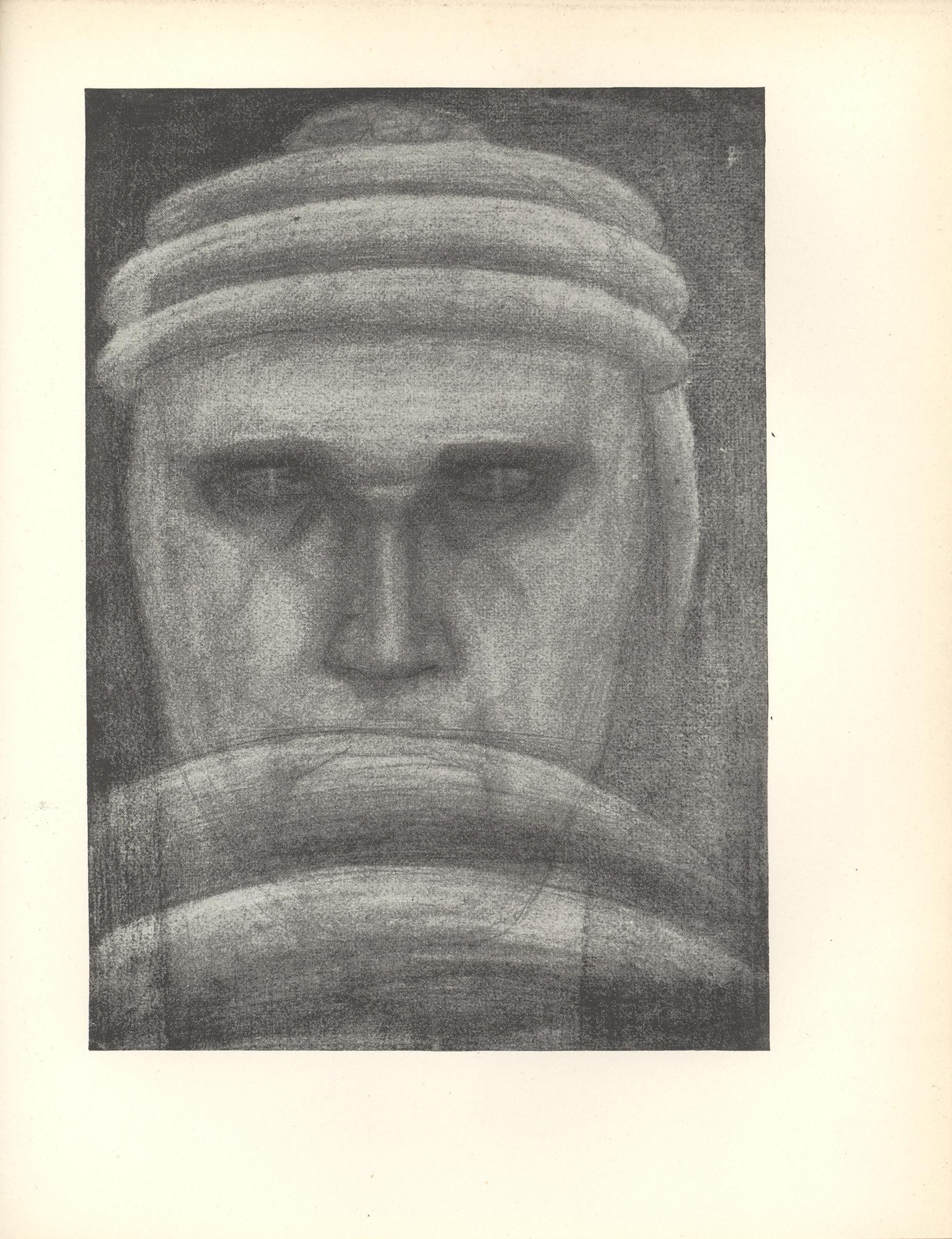

Head of Minos .. J. T. Nettleship .. 187

XII.

Portrait of a Lady .. Charles W.

Furse .. 199

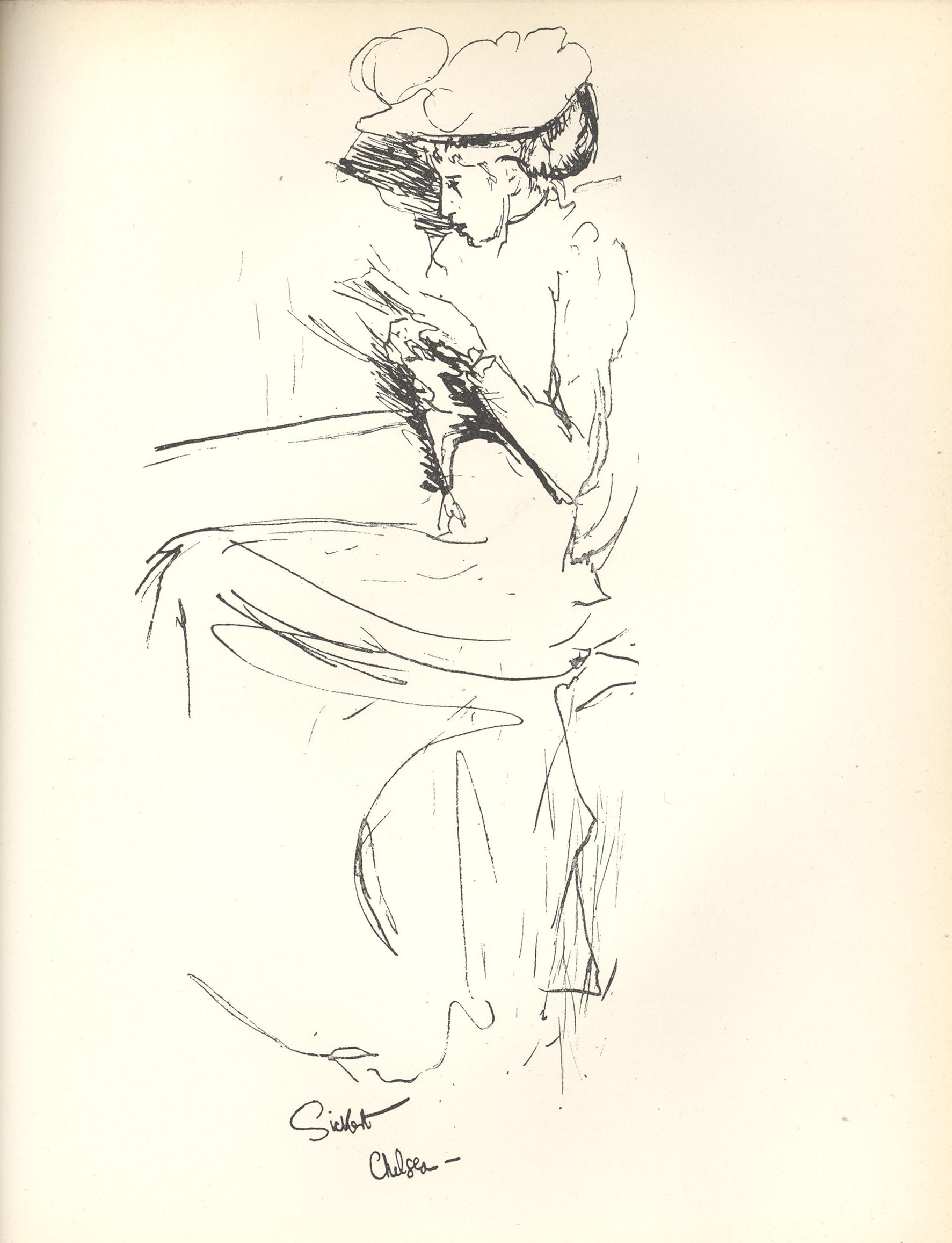

XIII. A Lady Reading ..

Walter Sickert .. 221

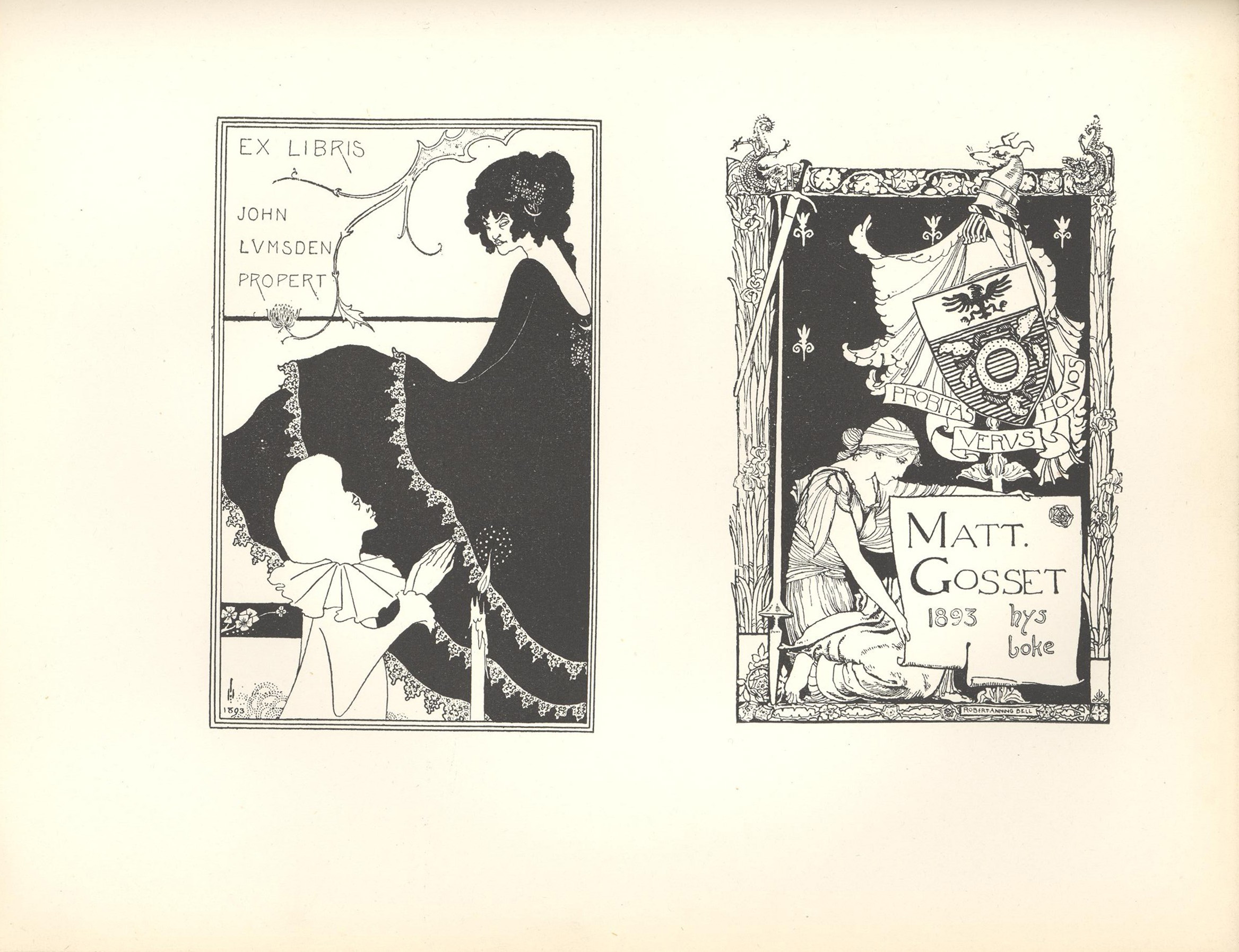

XIV. A Book Plate .. Aubrey Beardsley .. 251

XV.

A Book Plate .. R. Anning

Bell .. 251

Back Cover, by Aubrey Beardsley

Advertisements

The Death of the Lion

By Henry James

I

I HAD simply, I suppose, a change of heart, and it must

have

begun when I received my manuscript back from Mr. Pinhorn.

Mr. Pinhorn was my chief, as he was called in

the office: he

had accepted the high mission of bringing the paper up.

This

was a weekly periodical, and had been supposed to be almost past

redemption when he took hold of it. It was Mr.

Deedy who had

let it down so dreadfully — he was never mentioned

in the office

now save in connection with that misdemeanour. Young as I

was I had been in a manner taken over from Mr.

Deedy, who

had been owner as well as editor; forming part of a

promiscuous

lot, mainly plant and office-furniture, which poor Mrs. Deedy, in

her bereavement and depression,

parted with at a rough valuation.

I could account for my continuity only on

the supposition that

I had been cheap. I rather resented the practice of

fathering

all flatness on my late protector, who was in his unhonoured

grave; but as I had my way to make I found matter enough for

complacency in

being on a “staff.” At the same time I was

aware that I was exposed to

suspicion as a product of the old

lowering system. This made me feel that I

was doubly bound to

have

to Mr. Pinhorn that I should lay my lean hands on Neil Paraday.

I remember that he looked at me first as if he had never heard of

this celebrity, who indeed at that moment was by no means in the

middle of the heavens; and even when I had knowingly explained

he expressed but little confidence in the demand for any such

matter. When I had reminded him that the great principle on

which we were supposed to work was just to create the demand

we required, he considered a moment and then rejoined: “I see;

you want to write him up.”

“Call it that if you like.”

“And what’s your inducement?”

“Bless my soul — my admiration!”

Mr. Pinhorn pursed up his mouth. “Is there

much to be done

with him?”

“Whatever there is, we should have it all to ourselves for he

hasn’t been touched.”

This argument was effective, and Mr. Pinhorn responded:

“Very well, touch him.” Then he added: “But where can you

do

it?”

“Under the fifth rib!” I laughed.

Mr. Pinhorn stared. “Where’s that?”

“You want me to go down and see him?” I inquired, when I

had enjoyed

his visible search for this obscure suburb.

“I don’t “want” anything — the proposal’s your own. But you

must

remember that that’s the way we do things now,”

said Mr.

Pinhorn, with another dig at

Mr. Deedy.

Unregenerate as I was, I could read the queer implicationsoof

this speech. The present owner’s superior virtue as well as his

deeper

craft spoke in his reference to the late editor as one of

that baser sort who

deal in false representations. Mr. Deedy

would

have published a holiday-number; but such scruples presented

themselves as mere ignoble thrift to his successor, whose own

sincerity took the form of ringing door-bells and whose definition

of genius was the art of finding people at home. It was as if Mr.

Deedyhad published reports without his young men’s having, as

Mr. Pinhorn would have said, really been there. I was unre-

generate, as I have hinted, and I was not concerned to straighten

out the journalistic morals of my chief, feeling them indeed to be

an abyss over the edge of which it was better not to peer. Really

to be there this time moreover was a vision that made the idea of

writing something subtle about Neil Paraday only the more

inspiring. I would be as considerate as even Mr. Deedy could

have wished, and yet I should be as present as only Mr. Pinhorn

could conceive. My allusion to the sequestered manner in which

Mr. Paraday lived (which had formed part of my explanation,

though I knew of it only by hearsay) was, I could divine, very

much what had made Mr. Pinhorn bite. It struck him as in-

consistent with the success of his paper that any one should be so

sequestered as that. Moreover, was not an immediate exposure of

everything just what the public wanted? Mr. Pinhorn effectually

called me to order by reminding me of the promptness with which

I had met Miss Braby at Liverpool, on her return from her fiasco in

the States. Hadn’t we published, while its freshness and flavour

were unimpaired, Miss Braby’s own version of that great inter-

national episode? I felt somewhat uneasy at this coupling of the

actress and the author, and I confess that after having enlisted Mr.

Pinhorn’s sympathies I procrastinated a little. I had succeeded

better than I wished, and I had, as it happened, work nearer at

hand. A few days later I called on Lord Crouchley and carried

off in triumph the most unintelligible statement that had yet

appeared

appeared of his lordship’s reasons for his change of front. I thus

set in

motion in the daily papers columns of virtuous verbiage.

The following week I

ran down to Brighton for a chat, as Mr.

Pinhorn called it, with Mrs. Bounder, who gave me, on the

subject of

her divorce, many curious particulars that had not been

articulated in court.

If ever an article flowed from the primal

fount it was that article on

Mrs. Bounder. By this rime, however,

I became aware that Neil Paraday’s new book

was on the point of

appearing, and that its approach had been the ground of

my

original appeal to Mr. Pinhorn, who

was now annoyed with me

for having lost so many days. He bundled me off—we

would at

least not lose another. I have always thought his sudden alertness

a

remarkable example of the journalistic instinct. Nothing had

occurred,

since I first spoke to him, to create a visible urgency,

and no enlightenment

could possibly have reached him. It was a

pure case of professional flair—he had smelt the coming glory as

an animal

smells its distant prey.

I may as well say at once that this little record pretends in no

degree to be

a picture either of my introduction to Mr.

Paraday

or of certain proximate steps and stages. The scheme of my

narrative

allows no space for these things and in any case a pro-

hibitory sentiment

would be attached to my recollection of so rare

an hour. These meagre notes

are essentially private, and if they

see the light the insidious forces that,

as my story itself shows,

make at present for publicity will simply have

overmastered my

precautions. The curtain fell lately enough on the

lamentable

drama

drama. My memory of the day I alighted at Mr.

Paraday’s door

is a fresh memory of kindness, hospitality,

compassion, and of the

wonderful illuminating talk in which the welcome was

conveyed.

Some voice of the air had taught me the right moment, the

moment of his life at which an act of unexpected young allegiance

might most

come home. He had recently recovered from a long,

grave illness. I had gone

to the neighbouring inn for the night,

but I spent the evening in his

company, and he insisted the next

day on my sleeping under his roof. I had

not an indefinite leave:

Mr. Pinhorn supposed us to put out victims

through on the

gallop. It was later, in the office, that the step was

elaborated

and regulated. I fortified myself however, as my training had

taught me to do, by the conviction that nothing could be more

advantageous

for my article than to be written in the very atmo-

sphere. I said nothing to

Mr. Paraday about it, but in the

morning, after my removal from the inn, while he was occupied in

his study,

as he had notified me that he should need to be, I com-

mitted to paper the

quintessence of my impressions. Then

thinking to commend myself to Mr. Pinhorn by my celerity, I

walked out and

posted my little packet before luncheon. Once

my paper was written I was free

to stay on, and if it was designed

to divert attention from my frivolity in

so doing I could reflect

with satisfaction that I had never been so clever I

don’t mean to

deny of course that I was aware it was much too good for

Mr.

Pinhorn; but I was equally

conscious that Mr. Pinhorn had the

supreme shrewdness of recognising from time to time the cases in

which an

article was not too bad only because it was too good,

There was nothing he

loved so much as to print on the right

occasion a thing he hated. I had begun

my visit to Mr. Paraday

on a Monday, and on the Wednesday his book came out. A copy

of it

arrived by the first post, and he let me go out into the garden

with

with it immediately after breakfast. I read it from beginning to

end that

day, and in the evening he asked me to remain with him

the rest of the week

and over the Sunday.

That night my manuscript came back from Mr.

Pinhorn,

accompanied with a letter, of which the gist was the

desire to

know what I meant by sending him such stuff. That was the

meaning of the question, if not exactly its form, and it made my

mistake

immense to me. Such as this mistake was I could now

only look it in the face

and accept it. I knew where I had failed,

but it was exactly where I couldn’t

have succeeded. I had been

sent down there to be personal, and in point of

fact I hadn’t been

personal at all; what I had sent up to London was merely a little

finicking, feverish

study of my author’s talent. Anything less

relevant to Mr. Pinhorn’s purpose couldn’t well be imagined,

and

he was visibly angry at my having (at his expense, with a second-

class ticket) approached the object of our arrangement only to be

so deucedly

distant. For myself, I knew but too well what had

happened, and how a miracle

— as pretty as some old miracle of

legend — had been wrought on the spot to

save me. There had

been a big brush of wings, the flash of an opaline robe,

and then,

with a great cool stir of the air, the sense of an angel’s

having

swooped down and caught me to his bosom. He held me only

till the

danger was over, and it all took place in a minute. With

my manuscript back

on my hands I understood the phenomenon

better, and the reflections I made on

it are what I meant, at the

beginning of this anecdote, by my change of

heart. Mr. Pinhorn’s

note was hot only

a rebuke decidedly stern, but an invitation

immediately to send him (it was

the case to say so) the genuine

article, the revealing and reverberating

sketch to the promise of

which — and of which alone — I owed my squandered

privilege. A

week or two later I recast my peccant paper, and giving it a

particular

particular application to Mr. Paraday’s new

book, obtained for it

the hospitality of another journal, where, I must

admit, Mr. Pin-

horn was so far

justified that it attracted not the least attention.

I was frankly, at the end of three days, a very prejudiced critic,

so that

one morning when, in the garden, Neil

Paraday had

offered to read me something I quite held my breath

as I listened.

It was the written scheme of another book—something he

had

put aside long ago, before his illness, and lately taken out again

to

reconsider. He had been turning it round when I came down

upon him,

and it had grown magnificently under this second

hand. Loose, liberal,

confident, it might have passed for a great

gossiping, eloquent letter—the

overflow into talk of an artist’s

amorous plan. The subject I thought

singularly rich, quite the

strongest he had yet treated; and this familiar

statement of it, full

too of fine maturities, was really, in summarised

splendour, a mine

of gold, a precious, independent work. I remember rather

pro-

fanely wondering whether the ultimate production could possibly

be

so happy. His reading of the epistle, at any rate, made me

feel as if I were,

for the advantage of posterity, in close corre-

spondence with him — were the

distinguished person to whom it had

been affectionately addressed. It was

high distinction simply to

be told such things. The idea he now communicated

had all the

freshness, the flushed fairness of the conception untouched

and

untried: it was Venus rising from

the sea, before the airs had

blown upon her. I had never been so throbbingly

present at such

an unveiling. But when he had tossed the last bright word

after

the

the others, as I had seen cashiers in banks, weighing mounds of

coin, drop a

final sovereign into the tray, I became conscious of a

sudden prudent

alarm.

“My dear toaster, how, after all, are you going to do it?” I

asked.

“It’s infinitely noble, but what rime it will take, what

patience and

independence, what assured, what perfect conditions

it will demand! Oh for

a lone isle in a tepid sea!”

“Isn’t this practically a lone isle, and aren’t you, as

an encircling

medium, tepid enough?” he replied; alluding with a laugh

to the

wonder of my young admiration and the narrow limits of his little

provincial home. “Time isn’t what I’ve lacked hitherto: the

question

hasn’t been to find it, but to use it. Of course my

illness made a great

hole, but I daresay there would have been a

hole at any rate. The earth we

tread bas more pockets than a

billiard-table. The great thing is now to

keep on my feet.”

“That’s exactly what I mean.”

Neil Paraday looked at me with eyes — such

pleasant eyes as he

had — in which, as I now recall their expression, I seem

to have

seen a dim imagination of his fate. He was fifty years old, and

his illness had been cruel, his convalescence slow. “It isn’t as if

I

weren’t all right.”

“Oh, if you weren’t all right I wouldn’t look at you!” I

tenderly

said.

We had both got up, quickened by the full sound of it all, and

he had lighted

a cigarette. I had taken a fresh one, and, with an

intenser smile, by way of

answer to my exclamation, he touched it

with the flame of his match. “If I

weren’t better I shouldn’t have

thought of that!” He flourished his epistle in his hand.

“I don’t want to be discouraging, but that’s not true,” I re-

turned.

” I’m sure that during the months you lay here in pain

You had

visitations sublime. You thought of a thousand things.

You

you, if you will pardon my familiarity, so respectable. At a time

when so many people are spent you come into your second wind.

But, thank God, all the same, you’re better! Thank God, too,

you’re not, as you were telling me yesterday, ‘successful.’ If you

weren’t a failure, what would be the use of trying? That’s my

one reserve on the subject of your recovery — that it makes you

“score,” as the newspapers say. It looks well in the newspapers,

and almost anything that does that is horrible. ‘We are happy

to announce that Mr. Paraday, the celebrated author, is again in

the enjoyment of excellent health.’ Somehow I shouldn’t like to

see it.”

“You won’t see it; I’m not in the least celebrated — my

obscurity protects

me. But couldn’t you bear even to see I was

dying or dead?” my

companion asked.

“Dead — passe encore; there’s

nothing so safe. One never

knows what a living artist may do — one has

mourned so many.

However, one must make the worst of it; you must be as

dead as

you can.”

“Don’t I meet that condition in having just published a book?”

“Adequately, let us hope; for the book is verily a master- piece.”

At this moment the parlour-maid appeared in the door that

opened into the

garden: Paraday lived at no great cost, and

the

frisk of petticoats, with a timorous “Sherry, sir?” was about

his

modest mahogany. He allowed hall his income to his wife, from

whom

he had succeeded in separating without redundancy of legend.

I had a general

faith in his having behaved well, and I had once, in

London, taken Mrs.

Paraday down to dinner. He now turned to

speak to the maid, who

offered him, on a trait, some card or note,

while

while agitated, excited, I wandered to the end of the garden.

The idea of his

security became supremely dear to me, and I asked

myself if I were the same

young man who had come down a few

days before to scatter him to the four

winds. When I retraced

my steps he had gone into the house and the woman (the second

London post had come in) had placed my letters

and a newspaper

on a bench. I sat down there to the letters, which were a

brief

business, and then, without heeding the address, took the paper

from its envelope. It was the journal of highest renown, The

Empire of that morning. It regularly camee to

Paraday, but I

remembered that

neither of us had yet looked at the copy already

delivered. This one had a

great mark on the editorial page,

and, uncrumpling the wrapper, I saw it to

be directed to my host

and stamped with the name of his publishers. I

instantly divined

that The Empire had

spoken of him, and I have not forgotten the

odd little shock of the

circumstance. It checked all eagerness and

made me drop the paper a moment.

As I sat there, conscious of

a palpitation, I think I had a vision of what

was to be. I had

also a vision of the letter I would presently address to

Mr. Pinhorn,

breaking as it were

with Mr. Pinhorn. Of course, however,

the next minute the voice of The Empire was

in my ears.

The article was not, I thanked Heaven, a review; it was a

leader, the last of

three, presenting Neil Paraday to the

human

race. His new book, the fifth from his hand, had been but a day

or

two out, and The Empire, already aware of

it, fired, as if on the

birth of a prince, a salure of a whole column. The

guns had been

booming these three hours in the house without out

suspecting

them. The big blundering newspaper had discovered him, and

now he was proclaimed and anointed and crowned. His place was

assigned him as

publicly as if a fat usher with a wand had pointed

to the topmost chair; he

was to pass up and still up, higher and

higher,

higher, between the watching faces and the envious sounds — away

up to the

daïs and the throne. The article was a date; he had

taken rank at a bound —

waked up a national glory. A national

glory was needed, and it was an immense

convenience he was there.

What all this meant rolled over me, and I fear I

grew a little faint

—it meant so much more than I could say “yea” to

on the spot.

land a flash, somehow, all was different; the tremendous wave

I

speak of had swept something away. It had knocked down, I

suppose, my

little customary altar, my twinkling tapers and my

flowers, and had reared

itself into the likeness of a temple vast and

bare. When Neil Paraday should come out of the house he

would

come out a contemporary. That was what had happened — the

poor man

was to be squeezed into his horrible age. I felt as if

he had been overtaken

on the crest of the hill and brought back

to the city. A little more and he

would have dipped down to

posterity and escaped.

When he came out it was exactly as if he had been in custody,

for beside him

walked a stout man with a big black beard, who,

save that he wore spectacles,

might have been a policeman, and

in whom at a second glance I recognised the

highest contemporary

enterprise.

“This is Mr. Morrow,” said Paraday, looking, I thought,

rather white;

“he wants to publish heaven knows what about

me.”

I winced as I remembered that this was exactly what I myself

had wanted.

“Already?” I exclaimed, with a sort of sense that

my friend had

fled to me for protection.

The Yellow Book–Vol. I. B

Mr. Morrow

Mr. Morrow glared, agreeably, through his

glasses: they

suggested the electric headlights of some monstrous modern

ship,

and I felt as if Paraday and I

were tossing terrified under his

bows. I saw that his momentum was

irresistible, “I was

confident that I should be the first in the

field,” he declared.

“A great interest is naturally felt in Mr. Paraday’s surroundings.”

“I hadn’t the least idea of it,” said Paraday, as if he had been

told he had been snoring.

“I find he has not read the article in The

Empire,”Mr. Morrow

remarked to me. “That’s so very interesting — something to

start

with,” he smiled. He had begun to pull off his gloves,

which were

violently new, and to look encouragingly round the

little garden. As a

“surrounding” I felt that I myself had

already been taken in; I was

a little fish in the stomach of a

bigger one. “I represent,” our

visitor continued, “a syndicate of

influential journals, no less than

thirty-seven, whose public —

whose publics, I may say — are in peculiar

sympathy with Mr.

Paraday’s line of

thought. They would greatly appreciate any

expression of his views on the

subject of the art he so brilliantly

practises. Besides my connection with

the syndicate just men-

tioned, I hold a particular commission from The Tatler, whose

most prominent

department, Smatter and Chatter — I

daresay

you’ve often enjoyed it — attracts such attention. I was

honoured

only last week, as a representative of The Tatler, with the confi-

dence of Guy Walsingham, the author of ‘Obsessions.’ She

expressed herself thoroughly pleased with my

sketch of her

method; she went so far as to say that I had made her

genius

more comprehensible even to herself.”

Neil Paraday had dropped upon the

garden-bench and sat there,

at once detached and confused; he looked hard at

a bare spot in

the lawn, as if with an anxiety that had suddenly made him grave.

His

to sink sympathetically into a wicker chair that stood hard by,

and as Mr. Morrow so settled himself I felt that he had taken

official possession and that there was no undoing it. One had

heard of unfortunate people’s having a man in the house, and

this was just what we had. There was a silence of a moment,

during which we seemed to acknowledge in the only way that

was possible the presence of universal fate; the sunny stillness

took no pity, and my thought, as I was sure Paraday’s was doing,

performed within the minute a great distant revolution. I saw

just how emphatic I should make my rejoinder to Mr. Pinhorn,

and that having come, like Mr. Morrow, to betray, I must

remain as long as possible to save. Not because I had brought

my mind back, but because our visitor’s last words were in my

ear, I presently inquired with gloomy irrelevance if Guy Wals-

ingham were a woman.

“Oh yes, a mere pseudonym; but convenient, you know, for

a lady who goes

in for the larger latitude. Obsessions, by Miss

So-and-So would look a little odd, but men are more naturally

indelicate.

Have you peeped into Obsessions?”Mr. Morrow

continued sociably to our companion.

Paraday, still absent, remote, made no

answer, as if he had not

heard the question: a manifestation that appeared to

suit the

cheerful Mr. Morrow as well as

any other. Imperturbably bland,

he was a man of resources — he only needed to

be on the spot.

He had pocketed the whole poor place while Paraday and I were

woolgathering, and I could

imagine that he had already got his

heads. His system, at any rate, was

justified by the in-

evitability with which I replied, to save my friend the trouble:

“Dear, no; he hasn’t read it. He doesn’t read such things!” I

unwarily

added.

Things

“Things that are too far over the fence, eh?” I was indeed a

godsend

to Mr. Morrow. It was the psychological

moment; it

determined the appearance of his notebook, which, however, he

at

first kept slightly behind him, as the dentist, approaching his

victim, keeps his horrible forceps. “Mr.

Paraday holds with the

good old proprieties — I see!”

And, thinking of the thirty-seven

influential journals, I found myself, as I

found poor Paraday, help-

lessly gazing

at the promulgation of this ineptitude. “There’s

no point on which

distinguished views are so acceptable as on this

question — raised perhaps

more strikingly than ever by Guy Wals-

ingham— of the permissibility of the larger latitude. I have

an

appointment, precisely in connection with it, next week, with

Dora Forbes, the author of ‘The Other Way Round,’ which

everybody is talking

about. Has Mr. Paraday glanced at ‘The

Other Way Round’?”Mr. Morrow now frankly appealed to

me.

I took upon myself to repudiate the supposition, while our

companion, still

silent, got up nervously and walked away. His

visitor paid no heed to his

withdrawal; he only opened out the

notebook with a more motherly pat.

“Dora Forbes, I gather, takes

the ground, the same as Guy Walsingham’s,

that the larger

latitude has simply got to come. He holds that it bas got

to

squarely faced. Of course his sex makes him a less prejudiced

witness. But an authoritative word from Mr.

Paraday— from the

point of view of his sex, you know — would

go right round the

globe. He takes the line that we haven’t got to face

it?”

I was bewildered; it sounded somehow as if there were three

sexes. My

interlocutor’s pencil was poised, my private responsi-

bility great. I simply

sat staring, however, and only, found

presence of mind to say: “Is this

Miss Forbes a gentleman?”

Mr. Morrow hesitated an instant, smiling:

“It wouldn’t be

“Miss” — there’s a wife!”

I

“I mean is she a man?”

“The wife?” — Mr. Morrow, for a

moment, was as confused

as myself. But when I explained that I alluded to

Dora Forbes

in person he informed me, with visible amusement at my being

so out of

it, that this was the pen-name of an indubitable male

— he had a big red

moustache. “He only assumes a feminine

personality because the ladies are

such popular favourites. A great

deal of interest is felt in this

assumption, and there’s every pro-

spect of its being widely

imitated.” Our host at this moment

joined us again, and Mr. Morrow remarked invitingly that he

should

be happy to make a note of any observation the movement

in question, the bid

for success under a lady’s name, might suggest

to Mr. Paraday. But the poor man, without catching the allu-

tion, excused himself, pleading that, though he was greatly

honoured by his

visitor’s interest, he suddenly felt unwell and

should have to take leave of

him — have to go and lie down and

keep quiet. His young friend might be

trusted to answer for

him, but he hoped Mr.

Morrow didn’t expect great things even

of his young friend. His

young friend, at this moment, looked

at Neil

Paraday with an anxious eye, greatly wondering if he were

doomed to be ill again; but Paraday’s own

kind face met his ques-

tion reassuringly, seemed to say in a glance

intelligible enough:

“Oh, I’m not ill, but I’m scared: get him out of the house as

quietly as

possible.” Getting newspaper-men out of the house was

odd business for

an emissary of Mr. Pinhorn, and I was so

exhila-

rated by the idea of it that I called after him as he left us:

“Read the article in The Empire, and

you’ll soon be all

right!”

“Delicious my having come down to tell him of it!”Mr.

Morrow ejaculated. “My cab was

at the door twenty minutes

after The

Empire had been laid upon my breakfast-table. Now

what have you

got for me?” he continued, dropping again into

his chair, from which,

however, the next moment he quickly

rose. “I was shown into the

drawing-room, but there must be

more to see—his study, his literary

sanctum, the little things he

has about, or other domestic objects or

features. He wouldn’t be

lying down on his study-table? There’s a great

interest always

felt in the scene of an author’s labours. Sometimes we’re

favoured

with very delightful peeps. Dora

Forbes showed me all his table-

drawers, and almost jammed

my hand into one into which I made

a dash! I don’t ask that of you, but if

we could talk things

over right there where he sits I feel as if I should

get the

keynote.”

I had no wish whatever to be rude to Mr.

Morrow, I was

much too initiated not to prefer the safety of

other ways; but I

had a quick inspiration and I entertained an

insurmountable, an

almost superstitious objection to his crossing the

threshold of my

friend’s little lonely, shabby, consecrated workshop.

“No,

we sha’n’t get at his lire that way,” I said. “The way to

get at

his lire is to — But wait a moment!” I broke off and went

quickly into the house; then, in three minutes, I reappeared before

Mr. Morrow with the two volumes of Paraday’s new book.

“His life’s here” I went on, “and I’m so full of this admirable

thing that I can’t talk of anything else. The artist’s life’s his

work,

and this is the place to observe him. What he has to tell

us

viewer’s the best reader.”

Mr. Morrow good-humouredly protested. “Do

you mean to

say that no other source of information should be opened to

us?”

“None other till this particular one — by far the most copious —

has been

quite exhausted. Have you exhausted it, my dear sir

Had you exhausted it

when you came down here? It seems to

me in our time almost wholly

neglected, and something should

surely be done to restore its ruined

credit. It’s the course to

which the artist himself at every step, and

with such pathetic

confidence, refers us. This last book of Mr. Paraday’s is full of

revelations.”

“Revelations.” panted Mr. Morrow,

whom I had forced

again into his chair.

“The only kind that count. It tells you with a perfection that

seems to me

quite final all the author thinks, for instance, about the

advent of the

larger latitude.”

“Where does it do that?” asked Mr.

Morrow, who had picked

up the second volume and was insincerely

thumbing it.

“Everywhere — in the whole treatment of his case. Extract the

opinion,

disengage the answer — those are the real acts of homage.”

Mr. Morrow, after a minute, tossed the book

away. “Ah, but

you mustn’t take me for a reviewer.”

“Heaven forbid I should take you for anything so dreadful!

You came down

to perform a little act of sympathy, and so, I

may confide to you, did I.

Let us perform our little act together.

These pages overflow with the

testimony we want: let us read

them and taste them and interpret them. You

will of course

have perceived for yourself that one scarcely does read

Neil

Paraday till one reads him

aloud; he gives out to the ear an extra-

Ordinary quality, and it’s only

when you expose it confidently to

that

again and let me listen, while you pay it out, to that wonderful

fifteenth chapter. If you feel that you can’t do it justice, compose

yourself to attention while I produce for you — I think I can! —

this scarcely less admirable ninth.”

Mr. Morrow gave me a straight glance which

was as hard as a

blow between the eyes; he had turned rather red and a

question had

formed itselfin his mind which reached my sense as distinctly as

if

he had uttered it: “What sort of a damned fool are you?” Then

he got up, gathering together his hat and gloves, buttoning his

coat,

projecting hungrily all over the place the big transparency of

his mask. It

seemed to flare over Fleet Street and

somehow

made the actual spot distressingly humble: there was so little

for

it to feed on unless he counted the blisters of our stucco or saw

his way to do something with the roses. Even the poor roses

were common

kinds. Presently his eyes fell upon the manuscript

from which Paraday had been reading to me and which still lay

on

the bench. As my own followed them I saw that it looked

promising,

looked pregnant, as if it gently throbbed with the lire

the reader had given

it. Mr. Morrow indulged in a nod toward

it and a vague thrust of his umbrella. “What’s that?”

“Oh, it’s a plan — a secret.”

“A secret!” There was an instant’s silence, and then Mr.

Morrow made another movement. I may have

been mistaken,

but it affected me as the translated impulse of the desire to

lay

hands on the manuscript, and this led me to indulge in a quick

anticipatory grab which may very well have seemed ungraceful, or

even

impertinent, and which at any rate left Mr.

Paraday’s two

admirers very erect, glaring at each other while

one of them held

a bundle of papers well behind him. An instant later

Mr.

Morrow quitted me abruptly, as

if he had really carried some-

thing

I only grasped my manuscript the tighter. He went to the

back-door of the house, the one he had come out from, but on

trying the handle he appeared to find it fastened. So he passed

round into the front garden, and, by listening intently enough, I

could presently hear the outer gate close behind him with a bang.

I thought again of the thirty-seven influential journals and

wondered what would be his revenge. I hasten to add that he was

rnagnanimous: which was just the most dreadful thing he could

have been. The Tatler published a charming, chatty, familiar

account of Mr. Paraday’s “Home-life,” and on the wings of the

thirty-seven influential journals it went, to use Mr. Morrow’s own

expression, right round the globe. VI

A week later, early in May, my glorified friend came up to

town, where, it

may be veraciously recorded, he was the king of

the beasts of the year. No

advancement was ever more rapid, no

exaltation more complete, no bewilderment

more teachable. His

book sold but moderately, though the article in The Empire had

done unwonted wonders for

it; but he circulated in person in a

manner that the libraries might well

have envied. His formula

had been found — he was a revelation. His momentary

terror

had been real, just as mine had been — the overclouding of his

passionate desire to be left to finish his work. He was far from

unsociable,

but he had the finest conception of being let alone

that I have ever met. For

the time, however, he took his profit

where it seemed most to crowd upon him,

having in his pocket

the

Observation too was a kind of work and experience a kind of

success; London dinners were all material and London ladies

were fruitful toil. “No one has the faintest conception of what

I’m trying for,” he said to me, “and not many have read three

pages that I’ve written; but they’re all enthusiastic, enchanted,

devoted.” He found himself in truth equally amused and fatigued;

but the fatigue had the merit of being a new sort, and the phantas-

magoric town was perhaps after all less of a battlefield than the

haunted study. He once told me that he had had no personal life

to speak of since his fortieth year, but had had more than was

good for him before. London closed the parenthesis and exhibited

him in relations; one of the most inevitable of these being that in

which he found himself to Mrs. Weeks Wimbush, wife of the

boundless brewer and proprietress of the universal menagerie.

In this establishment, as everybody knows, on occasions when the

crush is great, the animais rub shoulders freely with the spectators

and the lions sit down for whole evenings with the lambs.

It had been ominously clear to me from the first that in Neil

Paraday this lady, who, as all the world

agreed, was tremendous

fun, considered that she had secured a prime

attraction, a creature

of almost heraldic oddity. Nothing could exceed ber

enthusiasm

over ber capture, and nothing could exceed the confused

apprehen-

sions it excited in me. I had an instinctive fear of her which

I

tried without effect to conceal from her victim, but which I let

her

perceive with perfect impunity. Paraday

heeded it, but she

never did, for her conscience was that of a romping child.

She was

a blind, violent force, to which I could attach no more idea of

responsibility than to the hum of a spinning-top. It was difficult

to say

what she conduced to but to circulation. She was constructed

of sted and

leather, and all I asked of her for our tractable friend

was

of indiarubber, but my thoughts were fixed on the day he should

resume his shape or at least get back into his box. It was evi-

dently all right, but I should be glad when it was well over. I

was simply nervous — the impression was ineffaceable of the hour

when, after Mr. Morrow’s departure, I had found him on the sofa

in his study. That pretext of indisposition had not in the least

been meant as a snub to the envoy of The Tatler — he had gone

to lie down in very truth. He had felt a pang of his old pain, the

result of the agitation wrought in him by this forcing open of a

new period. His old programme, his old ideal even had to be

changed. Say what one would, success was a complication and

recognition had to be reciprocal. The monastic life, the pious

illumination of the missal in the convent cell were things of the

gathered past. It didn’t engender despair, but it at least required

adjustment. Before I left him on that occasion we had passed a

bargain, my part of which was that I should make it my business

to take care of him. Let whoever would represent the interest in

his presence (I had a mystical prevision of Mrs. Weeks Wimbush),

I should represent the interest in his work — in other words, in his

absence. These two interests were in their essence opposed; and

I doubt, as youth is fleeting, if I shall ever again know the

intensity of joy with which I felt that in so good a cause I was

willing to make myself odious.

One day, in Sloane Street, I found myself

questioning Paraday’s

landlord, who had

come to the door in answer to my knock. Two

vehicles, a barouche and a smart

hansom, were drawn up before

the house.

“In the drawing-room, sir? Mrs. Weeks Wimbush.”

“And in the dining-room?”

“A young lady, sir — waiting: I think a foreigner.”

It

It was three o’clock, and on days when Paraday didn’t lunch

out he attached a value to these

subjugated hours. On which

days, however, didn’t the dear man lunch out?

Mrs. Wimbush,

at such a crisis,

would have rushed round immediately after her

own repast. I went into the

dining-room first, postponing the

pleasure of seeing how, upstairs, the lady

of the barouche would,

on my arrival, point the moral of my sweet solicitude.

No one

took such an interest as herself in his doing only what was good

for him, and she was always on the spot to see that he did it.

She made

appointments with him to discuss the best means of

economising his time and

protecting his privacy. She further

made his health her special business, and

had so much sympathy

with my own zeal for it that she was the author of

pleasing

fictions on the subject of what my devotion had led me to give

up. I gave up nothing (I don’t count Mr.

Pinhorn) because I

had nothing, and all I had as yet achieved

was to find myself

also in the menagerie. I had dashed in to save my friend,

but I

had only got domesticated and wedged; so that I could do nothing

for him but exchange with him over people’s heads looks of

intense but futile

intelligence.

The young lady in the dining-room had a brave face, black

hair, blue eyes,

and in her lap a big volume. “I’ve come for his

autograph,” she said,

when I had explained to her that I was

under bonds to see people for him when

he was occupied. “I’ve

been waiting half an bout, but I’m prepared to wait

all day.” I

don’t know whether it was this that told me she was American,

for

of her race. I was enlightened probably not so much by the

spirit of the utterance as by some quality of its sound. At an

y rate I saw she had an individual patience and a lovely frock, to-

gether with an expression that played among her pretty features

as a breeze among flowers. Putting her book upon the table, she

showed me a massive album, showily bound and full of autographs

of price. The collection of faded notes, of still more faded

“thoughts,” of quotations, platitudes, signatures, represented a

formidable purpose.

“Most people apply to Mr. Paraday by letter, you know,” I said.

“Yes, but he doesn’t answer, I’ve written three times.”

“Very true,” I reflected; “the sort of letter you mean goes

straight into the fire.”

“How do you know the sort I mean?” my interlocutress

asked. She had

blushed and smiled and in a moment she added:

“I don’t believe he gets many like them!”

“I’m sure they’re beautiful, but he burns without reading.” I

didn’t

add that I had told him he ought to.

“Isn’t he then in danger of burning things of importance?”

“He would be, if distinguished men hadn’t an infallible nose for

a

petition.” She looked at me a moment — her face was sweet and gay.

“Do you burn without reading, too?” she asked;

in answer to

which I assured her that if she would trust me with her

repository

I would see that Mr. Paraday

should write his name in it.

She considered a little. “That’s very well,

but it wouldn’t

make me see him.”

“Do you want very much to see him?” It seemed ungracious

to catechise

so charming a creature, but somehow I had never yet

taken my duty to the

great author so seriously.

Enough

“Enough to have come from America for the

purpose.”

I stared. “All alone?”

“I don’t see that that’s exactly your business; but if it will

make me

more appealing I will confess that I am quite by myself.

I had to come

alone or not at all.”

She was interesting; I could imagine that she had lost parents,

natural

protectors — could conceive even that she had inherited

money. I was in a

phase of my own fortunes when keeping

hansoms at doors seemed to me pure

swagger. As a trick of

this frank and delicate girl, however, it became

romantic — a part

of the general romance of her freedom, her errand, her

innocence.

The confidence of young Americans was notorious, and I

speedily

arrived at a conviction that no impulse could have been more

generous than the impulse that had operated here. I foresaw at

that moment

that it would make her my peculiar charge, just as cir-

cumstances had made

Neil Paraday. She would be another

person

to look after, and one’s honour would be concerned in guiding

her

straight. These things became clearer to me later; at the

instant I had

scepticism enough to observe to her, as I turned the

pages of her volume,

that her net had, all the same, caught many a

big fish. She appeared to have

had fruitful access to the great

ones of the earth; there were people

moreover whose signatures

she had presumably secured without a personal

interview. She

couldn’t have waylaid George

Washington and Friedrich

Schiller

and Hannah More. She met this

argument, to my surprise, by

throwing up the album without a pang. It wasn’t

even her own;

she was responsible for none of its treasures. It belonged to

a

girl-friend in America, a young lady

in a western city. This

young lady had insisted on her bringing it, to pick

up more auto-

graphs: she thought they might like to see, in Europe, in what

company they would be. The

girlfriend, the western city,

the

a story as strange to me, and as beguiling, as some tale in the

Arabian Nights. Thus it was that my informant had encum-

bered herself with the ponderous tome; but she hastened to as

sure me that this was the first time she had brought it out. For her

visit to Mr. Paraday it had simply been a pretext. She didn’t

really care a straw that he should write his name; what she did

want was to look straight into his face.

I demurred a little. “And why do you require to do that?”

“Because I just love him!” Before I could recover from the

agitating

effect of this crystal ring my companion had continued:

“Hasn’t there ever been any face that you’ve wanted to look

into?”

How could I tell her so soon how much I appreciated the

opportunity of

looking into hers? I could only assent in general

to the proposition that

there were certainly for every one such

faces; and I felt that the crisis

demanded all my lucidity, all my

wisdom. “Oh, yes, I’m a student of

physiognomy. Do you

mean,” I pursued, “that you’ve a passion for

Mr. Paraday’s

books?”

“They’ve been everything to me — I know them by heart.

They’ve completely

taken hold of me. There’s no author about

whom I feel as I do about

Neil Paraday.”

“Permit me to remark then,” I presently rejoined, “that

you’re one

of the right sort.”

“One of the enthusiasts? Of course I am!”

“Oh, there are enthusiasts who are quite of the wrong. I

mean you’re one

of those to whom an appeal can be made.”

“An appeal?” Her face lighted as if with the chance of some

great

sacrifice.

If she was ready for one it was only waiting for her, and in a

moment

him. Go away without it. That will be far better.”

She looked mystified; then she turned visibly pale. “Why,

hasn’t he any personal charm?” The girl was terrible and laugh-

able in her bright directness.

“Ah, that dreadful word personal!” I exclaimed; “we’re

dying of it, and you women bring it out with murderous effect.

When you

encounter a genius as fine as this idol of ours, let him

off the dreary

duty of being a personality as well. Know him

only by what’s best in him,

and spare him for the same sweet

sake.”

My young lady continued to look at me in confusion and mis-

trust, and the

result of her reflection on what I had just said

was to make her suddenly

break out: “Look here, sir — what’s the

matter with him?”

“The matter with him is that, if he doesn’t look out, people

will eat a

great hole in his life.”

She considered a moment. “He hasn’t any disfigurement?”

“Nothing to speak of!”

“Do you mean that social engagements interfere with his occu-

pations?”

“That but feebly expresses it.”

“So that he can’t give himself up to his beautiful imagin-

ation?”

“He’s badgered, bothered, overwhelmed, on the pretext of

being applauded.

People expect him to give them his time, his

golden time, who wouldn’t

themselves give five shillings for one of

his books.”

“Five? I’d give five thousand!”

“Give your sympathy — give your forbearance. Two-thirds of

those who

approach him only do it to advertise themselves.”

Why

“Why, it’s too bad!” the girl exclaimed, with the face of an

angel.

I followed up my advantage. “There’s a lady with him now

who’s a terrible

complication, and who yet hasn’t read, I am sure,

ten pages that he ever

wrote.”

My visitor’s wide eyes grew tenderer. “Then how does she

talk?”

“Without ceasing. I only mention her as a single case. Do

you want to know

how to show a superlative consideration?

Simply, avoid him.”

“Avoid him?” she softly wailed.

“Don’t force him to have to take account of you; admire him

in silence,

cultivate him at a distance and secretly, appropriate his

message. Do you

want to know,” I continued, warming to

my idea, “how to perform an

act of homage really sublime?”

Then as she hung on mg words: “Succeed in never seeing

him!”

“Never?” she pathetically gasped.

“The more you get into his writings the less you’ll want to;

and you’ll be

immensely sustained by the thought of the good

you’re doing him.”

She looked at me without resentment or spite, and at the truth

I had put

before her with candour, credulity and pity. I was

afterwards happy to

remember that she must have recognised in

my face the liveliness of my

interest in herself. “I think I see

what you mean.”

“Oh, I express it badly; but I should be delighted if you would

let me

come to see you — to explain it better.”

She made no response to this,

and her thoughtful eyes fell on

the big album, on which she presently laid

her hands as if to take

it away. “I did use to say out West that they

might write a little

The Yellow Book — Vol. I. C

less

the thoughts and style a little more.”

“What do they care for the thoughts and style? They didn’t

even understand

you. I’m not sure,” I added, “that I do myself,

and I daresay that

you by no means make me out.” She had got

up to go, and though I

wanted her to succeed in not seeing Neil

Paraday I wanted her also, inconsequently, to remain in the

house.

I was at any rate far from desiring to hustle her off. As Mrs.

Weeks Wimbush, upstairs, was still saving

our friend in her own

way, I asked my young lady to let me briefly relate, in

illustration

of my point, the little incident of my having gone clown into

the

country for a profane purpose and been converted on the spot to

holiness. Sinking again into her chair to listen, she showed a deep

interest

in the anecdote. Then, thinking it over gravely she ex-

claimed with her odd

intonation:

“Yes, but you do see him!” I had to admit that this was the

case; and

I was not so prepared with an effective attenuation as I

could have wished.

She eased the situation off, however, by the

charming quaintness with which

she finally said: “Well, I

wouldn’t want him to be lonely!” This time

she rose in earnest,

but I persuaded her to let me keep the album to show to

Mr.

Paraday. I assured her I would

bring it back to her myself.

“Well, you’ll find my address somewhere in it, on a paper!” she

sighed

resignedly, as she took leave.

I blush to confess it, but I invited Mr.

Paraday that very day

to transcribe into the album one of his

most characteristic passages.

I

it — her ominous name was Miss Hurter and she lived at an hotel;

quite agreeing with him moreover as to the wisdom of getting

rid with equal promptitude of the book itself. This was why I

carried it to Albemarle Street no later than on the morrow. I

failed to find her at home, but she wrote to me and I went again:

she wanted so much to hear more about Neil Paraday. I returned

repeatedly, I may briefly declare, to supply her with this informa-

tion. She had been immensely taken, the more she thought of it,

with that idea of mine about the act of homage: it had ended by

filling her with a generous rapture. She positively desired to do

something sublime for him, though indeed I could see that, as this

particular flight was difficult, she appreciated the fact that my visits

kept her up. I had it on my conscience to keep her up; I

neglected nothing that would contribute to it, and her conception

of our cherished author’s independence became at last as fine as his

own conception. “Read him, read him,” I constantly repeated;

while, seeking him in his works, she represented herself as con-

vinced that, according to my assurance, this was the system that

had, as she expressed it, weaned her. We read him together when

I could find time, and the generous creature’s sacrifice was fed by

our conversation. There were twenty selfish women, about whom

I told her, who stirred her with a beautiful rage. Immediately

after my first visit her sister, Mrs. Milsom, came over from Paris,

and the two ladies began to present, as they called it, their letters.

I thanked our stars that none had been presented to Mr. Paraday.

They received invitations and dined out, and some of these occa-

sions enabled Fanny Hurter to perform, for consistency’s sake,

touching feats of submission. Nothing indeed would now have

induced her even to look at the object of her admiration. Once,

hearing his name announced at a party, she instantly left the room

by

another time, when I was at the opera with them (Mrs. Milsom

had invited me to their box) I attempted to point Mr. Paraday

out to her in the stalls. On this she asked her sister to change

places with her, and, while that lady devoured the great man

through a powerful glass, presented, all the rest of the evening,

her inspired back to the house. To torment her tenderly I pressed

the glass upon her, telling her how wonderfully near it brought our

friend’s handsome head. By way of answer she simply looked at me

in grave silence; on which I saw that tears had gathered in her eyes.

These tears, I may remark, produced an effect on me of which

the end is not yet. There was a moment when I felt it my

duty to mention them to Neil Paraday; but I was deterred

by the reflection that there were questions more relevant to his

happiness.

These questions indeed, by the end of the season, were reduced

to a single

one — the question of reconstituting, so far as might be

possible, the

conditions under which he had produced his best

work. Such conditions could

never all come back, for there was

a new one that took up too much place; but

some perhaps were

not beyond recall. I wanted above all things to see him sit

down

to the subject of which, on my making his acquaintance, he had

read

me that admirable sketch. Something told me there was no

security but in his

doing so before the new factor, as we used to say

at Mr. Pinhorn’s, should render the problem

incalculable. It only

half reassured me that the sketch itself was so copious

and so eloquent

that even at the worst there would be the making of a small

but com-

plete book, a tiny volume which, for the faithful, might well

become

an object of adoration. There would even not be wanting critics

to declare, I foresaw, that the plan was a thing to be more thankful

for than

the structure to have been reared on it. My impatience

for

tions. He had, on coming up to town, begun to sit for his portrait

to a young painter, Mr. Rumble, whose little game, as we used to

say at Mr. Pinhorn’s, was to be the first to perch on the shoulders

of renown. Mr. Rumble’s studio was a circus in which the man

of the hour, and still more the woman, leaped through the hoops

of his showy frames almost as electrically as they burst into tele-

grams and “specials.” He pranced into the exhibitions on their

back; he was the reporter on canvas, the Vandyke up to date,

and there was one roaring year in which Mrs. Bounder and Miss

Braby, Guy Walsingham and Dora Forbes proclaimed in chorus

from the same pictured walls that no one had yet got ahead of

him.

Paraday had been promptly caught and

saddled, accepting with

characteristic good-humour his confidential hint that

to figure in

his show was not so much a consequence as a cause of

immortality.

From Mrs. Wimbush to the

last “representative” who called to

ascertain his twelve

favourite dishes, it was the same ingenuous

assumption that he would rejoice

in the repercussion. There

were moments when I fancied I might have had more

patience

with them if they had not been so fatally benevolent. I hated,

at all events, Mr. Rumble’s picture, and had

my bottled resent-

ment ready when, later on, I found my distracted friend

had

been stuffed by Mrs. Wimbush into

the mouth of another cannon.

A young artist in whom she was intensely

interested, and who

had no connection with Mr.

Rumble, was to show how far he

could shoot him. Poor Paraday, in return, was naturally to write

something somewhere about the young artist. She played her

victims against

each other with admirable ingenuity, and her

establishment was a huge machine

in which the tiniest and the

biggest wheels went round to the same treadle. I

had a scene

with

man was to exercise his genius — not to serve as a hoarding for

pictorial posters. The people I was perhaps angriest with were

the editors of magazines who had introduced what they called new

features, so aware were they that the newest feature of all would

be to make him grind their axes by contributing his views on

vital topics and taking part in the periodical prattle about the

future of fiction. I made sure that before I should have done

with him there would scarcely be a current form of words left

me to be sick of; but meanwhile I could make surer still of my

animosity to bustling ladies for whom he drew the water that

irrigated their social flower-beds.

I had a battle with Mrs. Wimbush over the

artist she protected,

and another over the question of a certain week, at the

end of

July, that Mr. Paraday appeared

to have contracted to spend with

her in the country. I protested against this

visit; I intimated

that he was too unwell for hospitality without a nuance, for caresses

without imagination; I begged he

might rather take the time in

some restorative way. A sultry air of promises,

of reminders hung

over his August, and he would great]y profit by the

interval of

test. He had not told me he was ill again — that he had a

warning; but I had not needed this, and I found his reticence

his worst

symptom. The only thing he said to me was that he

believed a comfortable

attack of something or other would set him

up: it would put out of the

question everything but the exemp-

tions he prized. I am afraid I shall have

presented him as a

martyr in a very small cause if I fail to explain that he

surren-

dered himself much more liberally than I surrendered him. He

filled his lungs, for the most part, with the comedy of his queer

fate: the

tragedy was in the spectacles through which I chose to

look. He was conscious

of inconvenience, and above all of a

great

in the bells of his accession? The sagacity and the jealousy were

mine, and his the impressions and the anecdotes. Of course, as

regards Mrs. Wimbush; I was worsted in my encounters, for was

not the state of his health the very reason for his coming to her

at Prestidge? Wasn’t it precisely at Prestidge that he was to

be coddled, and wasn’t the dear Princess coming to help her to

coddle him? The dear Princess, now on a visit to England, was

of a famous foreign house, and, in her gilded cage, with her retinue

of keepers and feeders, was the most expensive specimen in the

good lady’s collection. I don’t think her august presence had had

to do with Paraday’s consenting to go, but it is not impossible

that he had operated as a bait to the illustrious stranger. The

party had been made up for him, Mrs. Wimbush averred, and

every one was counting on it, the dear Princess most of all. If he

was well enough he was to read them something absolutely fresh,

and it was on that particular prospect the Princess had set her

heart. She was so fond of genius, in any walk of life, and she was

so used to it, and understood it so well; she was the greatest of

Mr. Paraday’s admirers, she devoured everything he wrote. And

then he read like an angel. Mrs. Wimbush reminded me that he

had again and again given her, Mrs. Wimbush, the privilege of

listening to him.

I looked at her a moment. “What has he read to you” I

crudely

inquired.

For a moment too she met my eyes, and for the fraction of a

moment she

hesitated and coloured, “Oh, all sorts of things!”

I wondered whether this were a perfect fib or only an imperfect

Recollection,

and she quite understood my unuttered comment on

her perception of such

things. But if she could forget Neil

Paraday’s beauties she could of course forget my rudeness, and

three

Prestidge. This time she might indeed have had a story about

what I had given up to be near the toaster. I addressed from

that fine residence several communications to a young lady in

London, a young lady whom, I confess, I quitted with reluctance

and whom the reminder of what she herself could give up was

required to make me quit at all. It adds to the gratitude I owe

her on other grounds that she kindly allows me to transcribe from

my letters a few of the passages in which that hateful sojourn is

candidly commemorated. IX

“I suppose I ought to enjoy the joke,” I wrote, “of what’s

going on here, but

somehow it doesn’t amuse me. Pessimism on

the contrary possesses me and

cynicism solicits. I positively feel

my own flesh sore from the brass nails

in Neil Paraday’s social

harness. The

house is full of people who like him, as they

mention, awfully, and with whom

his talent for talking nonsense

has prodigious success. I delight in his

nonsense myself; why is

it therefore that I grudge these happy folk their

artless satisfac-

tion? Mystery of the human heart — abyss of the critical spirit!

Mrs. Wimbush thinks she can answer that

question, and as my

want of gaiety has at last worn out her patience she has

given me

a glimpse of her shrewd guess. I am made restless by the

selfish-

ness of the insincere friend — I want to monopolise Paraday in

order that he may push me on. To be

intimate with him is a

feather in my cap; it gives me an importance that I

couldn’t

naturally pretend to, and I seek to deprive him of social

refresh-

ment because I fear that meeting more disinterested people may

enlighten

here are his particular admirers and have been carefully selected as

such. There is supposed to be a copy of his last book in the

house, and in the hall I come upon ladies, in attitudes, bending

gracefully over the first volume. I discreetly avert my eyes, and

when I next look round the precarious joy has been superseded by

the book of life. There is a sociable circle or a confidential

couple, and the relinquished volume lies open on its face, as if it

had been dropped under extreme coercion. Somebody else pre-

sently finds it and transfers it, with its air of momentary deso-

lation, to another piece of furniture. Every one is asking every

one about it all day, and every one is telling every one where they

put it last. I’m sure it’s rather smudgy about the twentieth page.

I have a strong impression too that the second volume is lost —

has been packed in the bag of some departing guest; and yet

everybody has the impression that somebody else has read to the

end. You see therefore that the beautiful book plays a great

part in our conversation. Why should I take the occasion of

such distinguished honours to say that I begin to see deeper into

Gustave Flaubert’s doleful refrain about the hatred of literature?

I refer you again to the perverse constitution of man.

“The Princess is a massive lady with the

organisation of an

athlete and the confusion of tongues of a valet de place. She

contrives to commit herself

extraordinarily little in a great many

languages, and is entertained and

conversed with in detachments

and relays, like an institution which goes on

from generation to

generation or a big building contracted for under a

forfeit. She

can’t have a personal taste, any more than, when her

husband

succeeds, she can have a personal crown, and her opinion on any

matter is rusty and heavy and plain — made, in the night of ages,

to last and

be transmitted. I feel as if I ought to pay some one a

fee

world and has never perceived anything, and the echoes of her

education respond awfully to the rash footfall — I mean the casual

remark — in the cold Valhalla of her memory. Mrs. Wimbush

delights in her wit and says there is nothing so charming as to

hear Mr. Paraday draw it out. He is perpetually detailed for this

job, and he tells me it has a peculiarly exhausting effect. Every

one is beginning — at the end of two days — to sidle obsequiously

away from her, and Mrs. Wimbush pushes him again and again into

the breach: None of the uses I have yet seen him put to irritate

me quite so much. He looks very fagged, and has at last confessed

to me that his condition makes him uneasy — has even promised

me that he will go straight home instead of returning to his final

engagements in town. Last night I had some talk with him

about going to-day, cutting his visit short; so sure am I that he

will be better as soon as he is shut up in his lighthouse. He told

me that this is what he would like to do; reminding me, how-

ever, that the first lesson of his greatness has been precisely that

he can’t do what he likes. Mrs. Wimbush would never forgive

him if he should leave her before the Princess has received the

last hand. When I say that a violent rupture with our hostess

would be the best thing in the world for him he gives me to

understand that if his reason assents to the proposition his courage

hangs wofully back. He makes no secret of being mortally afraid

of her, and when I ask what harm she can do him that she hasn’t

already done he simply repeats: “I’m afraid, I’m afraid! Don’t

inquire too closely,” he said last night; “only believe that I feel

a sort of terror. It’s strange, when she’s so kind! At any rate,

I would as soon overturn that piece of priceless Sèvres as tell her

that I must go before my date.” It sounds dreadfully weak, but

he has some reason, and he pays for his imagination, which puts

him

even against himself, their feelings, their appetites, their motives.

He’s so beastly intelligent. Besides, the famous reading is still to

come off, and it has been postponed a day, to allow Guy Walsing-

ham to arrive. It appears that this eminent lady is staying at a

house a few miles off, which means of course that Mrs. Wimbush

has forcibly annexed her. She’s to come over in a day or two —

Mrs. Wimbush wants her to hear Mr. Paraday.

“To-day’s wet and cold, and several of the company, at the

invitation of the

Duke, have driven over to luncheon at Bigwood.

I saw poor Paraday wedge himself, by command, into the little

supplementary seat of a brougham in which the Princess and our

hostess were already ensconced. If the front

glass isn’t open on

his dear old back perhaps he’ll survive. Bigwood, I believe, is very

grand and frigid, all

marble and precedence, and I wish him well

out of the adventure. I can’t tell

you how much more and more

your attitude to him, in the midst of all this,

shines out by contrast.

I never willingly talk to these people about him, but

see what a

comfort I find it to scribble to you! I appreciate it; it keeps

me

warm; there are no fires in the house. Mrs.

Wimbush goes by

the calendar, the temperature goes by the

weather, the weather

goes by God knows what, and the Princess is easily heated. I

have nothing but

my acrimony to warm me, and have been out

under an umbrella to restore my

circulation. Coming in an hour

ago, I found Lady

Augusta Minch rummaging about the hall.

When I asked her what

she was looking for she said she had

mislaid something that Mr. Paraday had lent her. I ascertained

in a

moment that the article in question is a manuscript and I

have a foreboding

that it’s the noble morsel he read me six weeks

ago. When I expressed my

surprise that he should have passed

about anything so precious (I happen to

know it’s his only copy —

in

to me that she had not had it from himself, but from Mrs.

Wimbush, who had wished to give her a glimpse of it as a salve

for her not being able to stay and hear it read.

“”Is that the piece he’s to read,” I asked, “when Guy Wals-

ingham arrives?”

“”It’s not for Guy Walsingham they’re

waiting now, it’s for

Dora Forbes,”Lady Augusta said. “She’s coming, I

believe, early

to-morrow. Meanwhile Mrs.

Wimbush has found out about him,

and is actively wiring to him. She says he also must hear him.”

“”You bewilder me a little,” I replied; “in the age we live in

one

gets lost among the genders and the pronouns. The clear

thing is that

Mrs. Wimbush doesn’t guard such a

treasure as

jealously as she might.”

“”Poor dear, she has the Princess to

guard! Mr. Paraday lent

her the

manuscript to look over.”

“”Did she speak as if it were the morning paper?”

“Lady Augusta stared — my irony was lost

upon her. “She

didn’t have time, so she gave me a chance first; because

unfor-

tunately I go to-morrow to Bigwood.”

“”And your chance has only proved a chance to lose it?”

“”I haven’t lost it. I remember now — it was very stupid of

me to have

forgotten. I told my maid to give it to Lord Dori-

mont — or at least to

his man.”

“”And Lord Dorimont went away directly after luncheon.”

“”Of course he gave it back to my maid — or else his man did,”

said Lady Augusta. “I daresay it’s all

right.”

“The conscience of these people is like a summer sea. They

haven’t time to

look over a priceless composition; they’ve only

time to kick

it about the house. I suggested that the man, fired

with a noble

emulation, had perhaps kept the work for his own

perusal;

didn’t turn up again in time for the session appointed by out

hostess, the author wouldn’t have something else to read that would

do just as well. Their questions are too delightful! I declared

to Lady Augusta briefly that nothing in the world can ever do as

well as the thing that does best; and at this she looked a little

confused and scared. But I added that if the manuscript had gone

astray our little circle would have the less of an effort of attention

to make. The piece in question was very long — it would keep

them three hours.

“”Three hours! Oh, the Princess will get

up!” said Lady

Augusta.

“”I thought she was Mr. Paraday’s greatest admirer.”

“‘I daresay she is — she’s so awfully clever. But what’s the