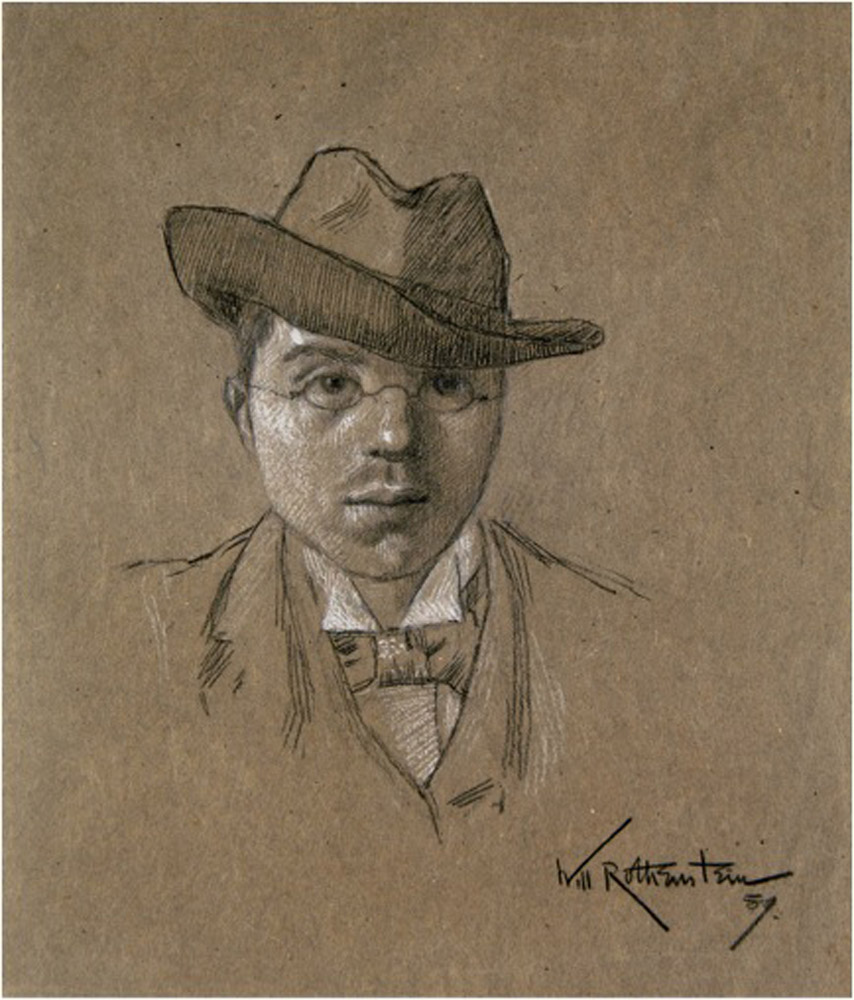

William Rothenstein

(1872 – 1945)

Painter, printmaker, draughtsman, gallery founder, multiple society-member, art critic, lecturer, social net-worker par excellence, and prolific memoirist: William Rothenstein’s energies were, as Wyndham Lewis once remarked, “parcelled out over a wide field” (Lewis 218). Beyond this, aspects of his identity have always been hard to pin down. Rothenstein was a northerner who lived largely in the south; a cosmopolitan with a firm faith in the English tradition; a purveyor of small pencil portraits who espoused covering large walls with paint; and a seemingly conservative artist who nevertheless encouraged many of the big names in modern British art, Lewis included.

Throughout his life, Rothenstein mingled on mutual terms with a multitude of names that seem likely to last longer than his own. These included artists such as Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) and Augustus John (1878-1961); and writers such as Max Beerbohm (1872-1956), Joseph Conrad (1857-1924), and Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). As a portraitist he commanded sittings from leading politicians, scientists, and social reformers. In the somewhat sceptical words of his close friend Charles Conder (1868-1909), Rothenstein was clearly an “important personage” (Galbally 235), and yet he was an anxious leader also, just as likely to withdraw from centre stage as to take it.

Rothenstein was born in 1872 in Bradford, West Yorkshire, the fourth child of Bertha and Moritz Rothenstein, a successful textile merchant who had emigrated from Germany in the 1860s. His parents were Jewish, but worshipped infrequently; in unpublished notes for his memoirs, Rothenstein wrote of his father: “he was not much in sympathy with Jewish tradition. He was more attracted by Unitaranianism” (Houghton Library, Harvard). Rothenstein was educated at Bradford Grammar School, but his talent for the fine arts persuaded his family to send him to London to study at the Slade School of Art in 1888. After a year working under Alphonse Legros (1837-1911), he followed his fellow student Arthur Studd (1866-1919) to Paris, where he enrolled in the Academié Julian.

Rothenstein remained in Paris from 1889-92, making important contacts within the European and Anglo-American artist communities based there. Though he would later destroy much of the work produced in this period, some key paintings have survived, not least the Tate-owned Parting at Morning (1891), which takes inspiration from Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898), Degas, and Robert Browning (1812-1889). Several sketchbooks also exist, which reveal a loose, Impressionistic drawing technique, which Rothenstein would later abandon in favour of heavier, unbroken lines and a firm sense of design.

In 1892 Rothenstein, encouraged by Toulouse-Lautrec, shared an exhibition with the Anglo-Australian artist Charles Conder at Père Thomas’s in the Boulevard Malesherbes. Attended by Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) and Edgar Degas, and well-reviewed in the French press, the exhibition suggested a bright future for Rothenstein in the French capital. Nevertheless, the following year he chose to return to England to work on a series of portraits (published by Grant Richards as Oxford Characters in 1896). This was the first of several collections of delicate lithographic, pencil or chalk portraits depicting men and women of distinction, examples of which would also appear in The Yellow Book (volumes 1 and 4).

At the same time he began exhibiting larger works at the New English Art Club, including paintings such as The Coster Girls (1894) and Porphyria (1894), which showed the debt he owed to both Degas and James McNeill Whistler. Rothenstein’s influences during the 1890s were, however, broad, and also included Goya (on whom he published the first English monograph in 1900), Rembrandt, and Jean-François Millet.

From 1894 to 1899 Rothenstein was based in Chelsea, where he mixed with a wide circle of artists and writers including Max Beerbohm (1872-1956), Laurence Binyon (1869-1943), Charles Ricketts (1866-1931), Walter Sickert (1860-1942), and—before his arrest in April 1895— Oscar Wilde (1854-1900). Though Wilde would tease the young artist for his seriousness and sobriety, others (including Beerbohm, who created a memorable written portrait of Rothenstein in his short story “Enoch Soames”) noted his wit, energy, and high-spiritedness. These qualities are clearly present in his writing from this period, which included art criticism for The Studio and The Saturday Review . In addition to The Yellow Book, Rothenstein also contributed art work to The Pageant and The Savoy, despite his quarrels with Leonard Smithers (1861-1907).

Rothenstein’s Parisian connections were especially valuable at this time. In 1895 he was instrumental in organising a visit from Paul Verlaine (1844-1896) to London; in the next few years he was responsible for furthering the reputation of Rodin in England. The Carfax Gallery, which Rothenstein co-founded in 1898 with the archaeologist John Fothergill (1876-1957), was the site of Rodin’s first solo-show in England. The Carfax also showed the work of Beerbohm, Conder, Ricketts, Augustus John, and, posthumously, Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898). Rothenstein resigned from his official role at the gallery in 1901, whereupon it fell under the management of Robert Ross, More Adey, and Arthur Clifton.

It could be argued that Rothenstein fulfilled the role of sensible older brother to many 1890s characters. At various points, he shared studios with both Conder and Beardsley, on whom he acted as a steadying influence. Despite the company he kept, Rothenstein’s decadence only went so far, and the behaviour of his fellow artists often bemused him. Acquiring a collection of Kitagawa Utamaro’s prints in Paris, Rothenstein was embarrassed by their eroticism and duly passed them onto Beardsley, who was not only un-embarrassed, but pasted them up on the walls of his bedroom.

Such stories indicate why Rothenstein’s first son, the art historian John Rothenstein, would later claim that the spirit of the 1890s was not one with which his father felt comfortable. After his marriage to the actress Alice Knewstub in 1899, Rothenstein’s art took a turn towards more austere, serious subjects. Gone were the illustrations to Balzac, Voltaire, and Villon; in came studies of his wife and children, and a series of paintings depicting Jewish life in the East End of London. The 1900s also saw Rothenstein step up his activities as a lecturer, establishing himself as a leading figure in the public mural movement. This led, eventually, to his appointment as Chair of Civic Art at the University of Sheffield in 1917 and, after the war, to the directorship of the Royal College of Arts, which he held from 1920 to 1935. Although Rothenstein’s work gained great critical success in the 1900s, receiving praise from critics such as Roger Fry, Laurence Binyon, and D. S. MacColl, sales remained poor and he relied on family money to keep his career going.

Ironically, considering his interest in French art, a trip to India in late 1910 ensured that Rothenstein missed the controversy surrounding Fry’s 1910 exhibition, Manet and the Post-Impressionists. His subsequent refusal to take part in the follow-up (the 1912 Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition ) caused a breach between the two men, and left Rothenstein feeling alienated within progressive art circles in Britain. Despite the vital support he offered to young artists (Augustus John, Paul Nash, and Wyndham Lewis included), his reputation began to decline after the First World War, in which he served as official War Artist. Twice rejecting offers of membership to the Royal Academy, Rothenstein continued to exhibit with the New English Art Club and related societies, though his relocation to Gloucestershire in 1912 reflected a desire to remove himself from the centre of the art world.

Rothenstein’s reputation received a boost in the early 1930s, upon the publication of the first of three volumes of his memoirs, Men and Memories . This is a vital text for anyone looking for insights into the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century British art world. As its title suggests, the book was not so much an autobiography as a collection of anecdotes about friends and associates. The first volume covers the 1890s in great detail, containing extensive written portraits of Beardsley, Conder, Ricketts, and Wilde, among others.

Knighted in 1931, Rothenstein was by now considered an establishment figure, though he would describe his 1938 exhibition, Fifty Years of Painting , as a “desolating failure” (Speaight 390). Portraiture continued to take up a large proportion of his time during the interwar period, alongside a series of Gloucestershire landscapes. Despite illness, he once again volunteered his services as a War Artist during the Second World War, contributing portraits of the RAF. He died shortly before the end of the war, in February 1945. A memorial exhibition was held at the Tate Gallery in London in 1950, and a centenary retrospective in Bradford in 1972. Rothenstein had four children. The oldest, John, was an art historian and Director of the Tate Gallery from 1938-1964, and the youngest, Michael, became a well-known print-maker.

Despite Robert Speaight’s 1962 biography and subsequent publications by Mary Lago, Rothenstein’s life and work were relatively neglected in the second half of the twentieth century. More recently, however, scholars have begun to re-evaluate the contribution he made to the British art scene, particularly in the period 1890-1920. Special focus has been given to his 1910 visit to India (and related role within the India Society), his Anglo-German connections, his Anglo-Jewish identity, and his campaign for public patronage. Good examples of his work, including over a hundred major paintings, can be found in public galleries across the United Kingdom. His archives are held at Harvard’s Houghton Library.

© Copyright 2013 Samuel Shaw, University of York

Samuel Shaw’s research focuses on the late nineteenth and early-twentieth century British art world, with a particular interest in the relationship between artists, critics and the art market. He is currently writing a study of William Rothenstein. In Autumn 2013 he will join the Yale Center for British Art as Post-Doctoral Associate in Prints and Drawings.

Selected Publications by William Rothenstein

- A Plea for a Wider Use of Artists & Craftsmen. London: Constable, 1916.

- English Portraits. London: Grant Richards, 1898.

- Goya. London: The Sign of the Unicorn, 1900.

- Men and Memories. Vol I. London: Faber & Faber, 1931.

- Men and Memories. Vol II. London: Faber & Faber, 1932.

- Oxford Characters. London: John Lane, 1896.

- Since Fifty. London: Faber & Faber 1939.

Selected Publications about William Rothenstein

- Arrowsmith, Rupert. “ ‘An Indian Renascence’ and the rise of global modernism: William Rothenstein in India, 1910-11,” The Burlington Magazine 152 (April 2010): 228-235.

- Beerbohm, Max. “Enoch Soames.” Seven Men. London: Heinemann, 1919.1-48.

- Brockington, Grace, ed. Internationalism and the Arts in Britain and Europe at the Fin-de-Siècle . Oxford: Peter Lang, 2009.

- Galbally, Ann. Charles Conder: The Last Bohemian. Melbourne: Melbourne UP, 2002.

- Gross, Peter. Representations of Jews and Jewishness in English Painting, 1887-1914 . PhD Thesis: University of Leeds, 2004.

- Lago, Mary, and Karl Beckson, ed. Max and Will: Max Beerbohm and William Rothenstein, their friendship and letters 1893 to 1945 . Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1975.

- Lago, Mary, ed. Imperfect Encounter: Letters of William Rothenstein and Rabindranath Tagore 1911-1941 . Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1972.

- Lewis, Percy Wyndham. “Fifty Years of Painting: Sir William Rothenstein’s Exhibition.” Apollo: The International Magazine of Art & Antiques 91 (March 1970): 218-223.

- Manson, James Bolivar. “The Paintings of Mr. William Rothenstein.” The Studio 50 (1910): 37-46.

- Powers, Alan. “William Rothenstein and the RCA.” Apollo: The International Magazine of Art & Antiques 144 (1996): 21-24.

- Rothenstein, John. A Pot of Paint: The Artists of the 1890s . New York: Covici, Friede, 1929.

- – – -. Modern English Painters: Vol I, Sickert to Smith . London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1952.

- – – -, ed. Portrait Drawings by William Rothenstein. London: Chapman & Hall, 1926.

- Rutter, Frank. “Sir William Rothenstein.” The Studio 111 (1931): 232-241.

- Saler, Michael T. The Avant-garde in Interwar England . Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999.

- Shaw, Samuel. “ ‘ Equivocal Positions’: The Influence of William Rothenstein, c1890—1910 . PhD Thesis: University of York, 2010.

- – – -. “Balzac and British Artists at the Turn of the Twentieth Century.” English Literature in Transition 56.3 (2013): 427-444.

- – – -. “ ‘The new ideal shop’: Founding the Carfax Gallery.” The British Art Journal 13.2 (2012): 35-43.

- Speaight, Robert. William Rothenstein: The Portrait of an Artist in his Time. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1962.

- Thompson, J, ed. Sir William Rothenstein, A Centenary Exhibition . Bradford: Bradford Museums, 1972.

- Turner, Sarah. “‘ Spiritual rhythm’ and ‘material things’: art, cultural networks and modernity in Britain, c.1900 – 1914 .” Phd Thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 2008.

- Willsdon, Clare. Mural Painting in Britain, 1840-1940: Image and Meaning, Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000.

MLA citation:

Shaw, Samuel. “William Rothenstein (1872-1945),” Y90s Biographies , 2013. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/rothenstein_bio/.