Max Beerbohm

(1872 – 1956)

The question of how to place Max Beerbohm historically must have caused as much confusion for Beerbohm himself as it has for critics in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Though he lived until 1956, his assertion in 1896 that he belonged to “the Beardsley period” seemed to hold true until his death (“Cosiness” 235). Throughout the early twentieth century, he represented himself as out of place, as a time traveler from a more aesthetically inflected and decorous past. However, in works such as Rossetti and His Circle (1922) his nostalgic gaze also shifted further back in time, to the roots of the yellow nineties in the 1860s, to Rossetti’s home at 16 Cheyne Walk and to the “divine singer,” Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909) (Beerbohm, And Even Now 64). Conversely, critics such as Terry Caesar have argued that Beerbohm’s proper place is amongst his twentieth-century contemporaries. According to Caesar, “the kind of writing which Beerbohm evolved . . . is not so different from that written by Eliot, Pound, or Joyce” (23). Evelyn Waugh similarly argued in 1956 that Beerbohm was “regarded as a man of the 1890s but his full flowering was in the 1920s” (12). As true as that may be, Beerbohm flowered in the interbellum period most fully as a point of access to the fin de siècle. His appeal rested on his connections to the final years of the previous century, his insider knowledge concerning Wilde and his circle, his dandyism, and his role as the writer of parodic manifestoes for the Decadent movement.

Though Beerbohm referred to himself as a “Tory anarchist,” he hailed from a middle-class background ( And Even Now 185). His father, Julius Ewald Beerbohm, was a grain merchant of Dutch, German, and Lithuanian heritage. His mother, Elizabeth Draper, was the sister of his father’s first wife, Constantia. Beerbohm spent his childhood in London before being sent away to Charterhouse School in Surrey, where he began to develop a reputation as a wit and caricaturist. He then attended Oxford in the early 1890s, a time when Wildean aestheticism held sway over many undergraduates, and he began to exhibit the impress of aestheticist dandyism and style. Beerbohm was introduced to Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) personally through his half-brother, Herbert Beerbohm Tree (1853-1917), a well-known actor and theatre manager. Their first encounter occurred at a dinner in the late-1880s, but it was while Beerbohm Tree was producing A Woman of No Importance in 1893 that Max came to know Wilde and his circle well. While at Oxford, he also met the writer Reggie Turner (1869-1938), a member of Wilde’s circle who remained loyal to the very end, and the artist Will Rothenstein (1872-1945), both of whom became close, lifelong friends. It was Rothenstein who introduced Beerbohm to the world of decadent London, to the Café Royal, the “haunt of intellect and daring” where Wilde and his circle mingled amidst the “exuberant vista of gilding and crimson velvet,” and to Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898) (Beerbohm, Seven Men 5).

Beardsley invited Beerbohm to contribute to the very first issue of The Yellow Book. With his essay “ A Defence of Cosmetics” Beerbohm helped to shape the voice of the periodical. However, his contributions often exhibited what Dennis Denisoff describes as a “camp” sensibility in relationship to the literary movements associated with The Yellow Book. His “Defence of Cosmetics,” for example, at once articulates and lampoons the decadent aesthetic of artifice. He compounded the offensiveness of the essay by taunting the reading public with images of cunning and frightening femininity and ridiculing The Yellow Book’s other primary source of contributors, the New Woman movement. According to Beerbohm, while the simple and “natural” women of the first days of the Victorian era exerted no influence and posed no threat, those “dear little creatures” have now been supplanted by “horrific pioneers of womanhood” who impose themselves upon the masculine realm of action (68-9). These women, however, he goes on to proclaim, will in turn be replaced by a far more modern mode of femininity; these will be women who eschew action that might cause their powder to fly or their enamel to crack, who instead repose in painted masks behind which their minds can “play without let,” planning, deceiving, and dissembling (70).

“A Defence of Cosmetics” seems designed to infuriate both conservative moralists and progressive feminists, as well as to irk the Decadents, but the most vociferous response came primarily in the form of moral outrage. As Beerbohm noted in his “ Letter to the Editor,” which appeared in Volume 2 of The Yellow Book, his “Defence” managed to “provoke ungovernable fury” and caused “the mob [to lose] its head” (281). The Westminster Gazette called for an Act of Parliament to “make this kind of thing illegal,” and another critic called the “Defence” “the rankest and most nauseous thing in all literature” (281). The “Letter to the Editor” reads, in true Beerbohmian fashion, as both a retraction and a reiteration of the “Defence.” Beerbohm reassures the angry mob that the essay was a hoax, but he concludes the letter by warning that English literature will “fall at length into the hands of the decadents,” that Artifice may in fact be at the gates, and, in fact, “by the time this letter appears, it may be too late” (284).

Beerbohm similarly oscillated between reverence and satire in his relationship to Wilde. His first publication, “Oscar Wilde by an American,” which appeared in the Anglo-American Times in March of 1893, praised Wilde as a “born writer” (289). (Wilde replied by asserting that the essay was “incomparably clever” [ LRT 34].) Beerbohm likewise rhapsodized that Salome “charmed [his] eyes from their sockets and through the voids sent incense to [his] brain” (LRT 32). As early as 1894, however, his fascination with Wilde became a bit more critical. For example, his “A Peep into the Past,” initially intended for Volume 1 of The Yellow Book, pokes fun at Wilde’s markedly feminine home decor and “the constant succession of page-boys” whose visits “so [startle] the neighborhood” (11). His caricatures from this period of a corpulent, unappealing Wilde reflect Beerbohm’s distaste for what he saw as increasing vulgarity and hedonism on Wilde’s part. However, he was horrified to see one of these caricatures, which had appeared in Pick-Me-Up in September of 1894, in the police inspector’s office during the trials in 1895: “I hadn’t realized till that moment how wicked it was. I felt as if I had contributed to the dossier against Oscar” (Behrman 85-6). After Wilde was released from prison, he received from Beerbohm a copy of his short story, “The Happy Hypocrite,” which had been published in The Yellow Book in 1896. Wilde responded with great pleasure, reading the work as a revision of Dorian Gray . While Beerbohm eventually emerged from Wilde’s influence to develop his own prose style, his debt to Wilde continued to be evident in his later work.

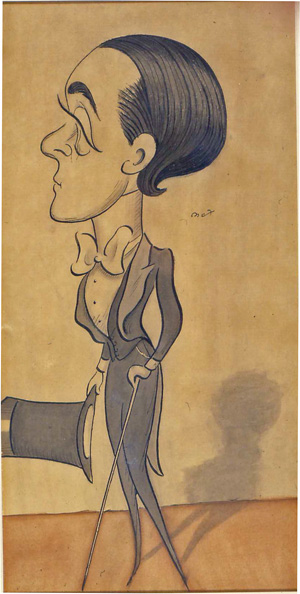

Critics and friends represent Beerbohm as either eternally youthful or always already elderly. Wilde said that the gods had bestowed on Max the gift of perpetual old age, while Roger Lewis has more recently argued that “his whole attitude evinces . . . a peculiarly late-Victorian and Edwardian trait: that of refusing to grow up” (297). In “Diminuendo” (1896), the 23 year old Beerbohm himself declared that he was outmoded and announced his decision to stop writing and retire to a London suburb. However, as David Cecil has argued, the contents of The Works of Max Beerbohm (1896), in which Beerbohm advertises himself as elderly and turns so deliberately to the past in essays such as “ 1880” and “ King George the Fourth,” are also “exuberantly youthful” (149). The equally playful Caricatures of Twenty-Five Gentlemen (1896) includes the now famous image of Beardsley leading a poodle by a ribbon, showing Beerbohm already assuming his role as camp portraitist of the yellow nineties.

Beerbohm continued to play the part of satiric chronicler of the fin de siècle far into the twentieth century, supplying a nostalgic public with caricatures of the Beardsley period in a series of exhibitions at the Leicester Galleries in the 1920s. By this point, Beerbohm had extracted himself from London life, retiring to Rapallo, Italy with his wife, Florence Kahn. His assertion that he had been rendered irrelevant was repeatedly undone by, for example, his popularity in the twenties and the adoration showered upon his radio broadcasts in the thirties and forties. He died at Rapallo in 1956, after wedding his friend and secretary, Elizabeth Jungmann, on his deathbed.

© 2010, Kristin Mahoney

Kristin Mahoney is an assistant professor in the English Department at Western Washington University. She has published articles on Vernon Lee and Dante Gabriel Rossetti in Criticism and Victorian Studies, and her scholarly edition of Baron Corvo’s Hubert’s Arthur was published by Valancourt Books. She is currently working on a project on the afterlife of late-Victorian aestheticism in the early-twentieth century.

Selected Publications by Max Beerbohm

- “A Defence of Cosmetics.” The Yellow Book I (1894): 65-82.

- “A Letter to the Editor.” The Yellow Book II (1894): 281-84.

- And Even Now. London: Heinemann, 1920.

- “Be It Cosiness.” The Pageant I (1896): 230-35. Rpt. as “Diminuendo” in The Works of Max Beerbohm . London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1896.

- Caricatures of Twenty-Five Gentlemen. London: Leonard Smithers, 1896.

- “The Happy Hypocrite.” The Yellow Book XI (1896): 11-44.

- More. London and New York: John Lane, 1899.

- “Oscar Wilde by an American.” Anglo-American Times (March 25, 1893). Rpt. in Max Beerbohm’s Letters to Reggie Turner . Ed. Rupert Hart-Davis. New York: J.B. Lippincott, 1965. 285-92.

- A Peep into the Past. Privately printed, 1923.

- Rossetti and His Circle. London: Heinemann, 1922.

- Seven Men. London: Heinemann, 1919.

- The Works of Max Beerbohm. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1896.

- Yet Again. London: Chapman and Hall, 1909.

- Zuleika Dobson. London: Heinemann, 1911.

- Hart-Davis, Rupert, ed. Letters of Max Beerbohm, 1892-1956 . 1st American ed ed., New York: W.W. Norton, 1989.

- Max Beerbohm’s Letters to Reggie Turner. London: R. Hart-Davis, 1964.

Selected Publications about Max Beerbohm

- Behrman, S.N. Portrait of Max: An Intimate Memoir of Sir Max Beerbohm . New York: Random House, 1960.

- Burgass, John. “Special Collections Report: The Beerbohm Collection At Merton College, Oxford.” English Literature in Transition 27.4 (1984): 320-22.

- Caesar, Terry. “Betrayal and Theft: Beerbohm, Parody, and Modernism.” Ariel 17.3 (1986): 23-37.

- Cecil, David. Max, A Biography. London: Constable, 1964.

- Danson, Lawrence. Max Beerbohm and the Act of Writing . New York: Clarendon, 1989.

- ———. Max Beerbohm: A Kind of Life. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

- Denisoff, Dennis. Aestheticism and Sexual Parody 1840-1940 . New York: Cambridge UP, 2006.

- Hall, N. John. Max Beerbohm Caricatures. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997.

- Lewis, Roger. “The Child and the Man in Max Beerbohm.” English Literature in Transition 27.4 (1984): 296-303.

- Lynch, Bohun. Max Beerbohm in Perspective. London: William Heinemann, 1921.

- Moers, Ellen. The Dandy: Brummel to Beerbohm. New York: Viking, 1960.

- Riewald, Jacobus Gerhardus. The Surprise of Excellence: Modern Essays on Max Beerbohm . Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1974.

- Schaffer, Talia. “Fashioning Aestheticism by Aestheticizing Fashion: Wilde, Beerbohm, and the Male Aesthetes’ Sartorial Codes.” Victorian Literature and Culture 28.1 (2000): 39-54.

- Viscusi, Robert. Max Beerbohm, or the Dandy Dante : Rereading With Mirrors . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1986.

- Waugh, Evelyn. “The Lesson of the Master.” South China Sunday Post June 10, 1956: 12.

MLA citation:

Mahoney, Kristin. “Max Beerbohm (1872-1956),” Y90s Biographies, 2010. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/beerbohm_bio/.