XML PDF

Critical Introduction to The Venture:

An Annual of Art and Literature Volume 1 (1903)

John Baillie (1868-1926) was not a publisher, but rather a London-based gallery owner when he issued the first volume of The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature in late November 1903. The reciprocal relationship between Baillie’s Gallery and his annual is evident in one of his fall exhibition catalogues, which urged visitors to “make it [The Venture] a success by ordering a copy” (Some Woodcuts, [viii]). In his dual role as art editor and publisher, Baillie was able to realize what Koenraad Claes aptly names “The Total Work of Art” objective of the late-Victorian little magazine (1). The crown quarto, which extended to 249 pages, was printed on laid paper at The Pear Tree Press by acclaimed artisanal printer James J. Guthrie (1874-1952). The Sketch reviewer enthused that the volume was “beautifully got up, having very wide margins, and being clearly printed in solid old English type on antique paper” (“The Venture,” 184). The critic also praised the volume’s treatment of art contents, noting: “Each woodcut, however small, has a page to itself, which gives a restful effect for which one is grateful” (ibid). In its design, The Venture recreated the effect of a gallery display within the confines of a printed book. The volume’s original prints were treated as works of art in their own right: because the fifteen images were all wood engravings, Guthrie was able to print them along with the type on his hand press. Consequently, the first volume of The Venture is one of the best designed and aesthetically harmonized of all the period’s little magazines.

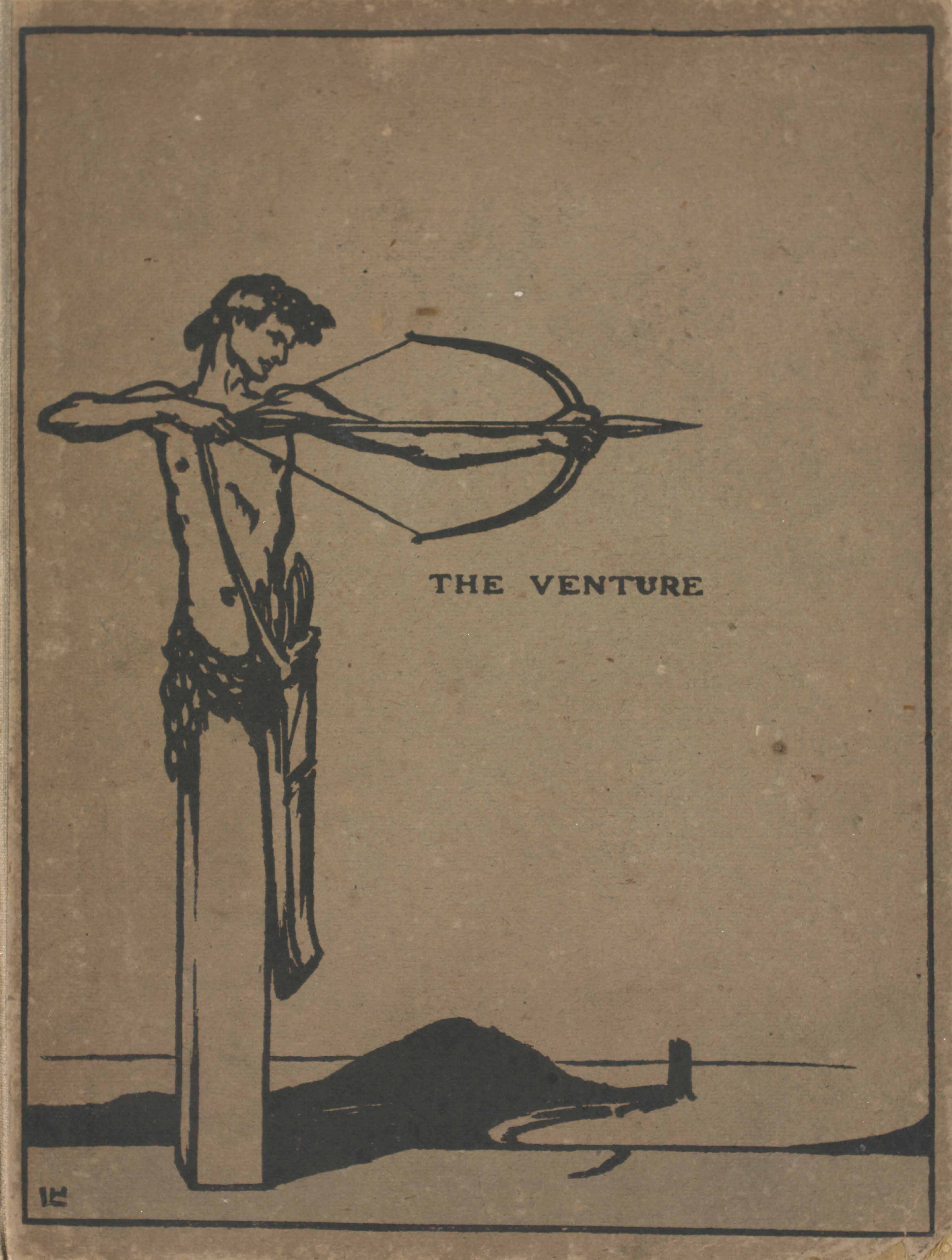

Some of the credit for this must surely be given to Laurence Housman (1865-1959), an experienced book designer who provided the illustration for the front cover. Invoking an artist’s portfolio by using buff-coloured paper over boards, Housman’s design created the visual effect of a portable gallery (fig. 1). The cover design pays bibliographic homage to fin-de-siècle innovations in the book arts by James McNeill Whistler (1843-1903) and Charles Ricketts (1866-1931). The former had introduced brown paper wrappers and asymmetrical typography in Mr. Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock” in 1888 (Calloway 13). The following year, Ricketts and his partner Charles Shannon (1863-1937) brought out the first issue of The Dial in brown paper wrappers, with a wood-engraved illustration featuring herms—human torsos set upon plinths—placed in the corners of a walled garden. Housman’s striking Venture cover combines Ricketts’s queer iconography with Whistler’s asymmetrical layout. Printed on the extreme left, Housman’s attenuated herm or caryatid figure appears in profile, ready to release a drawn arrow (fig. 1). Named “Love the Archer” by gay poet and editor Charles Kains-Jackson (1857-1933) (144), the design captures the tense excitement and high expectations that accompanied The Venture’s publication.

Baillie compounded his own lack of publishing experience by engaging two equally novice editors. The multi-talented Laurence Housman was an avant-garde writer as well as an illustrator and book designer, while W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1966) was a middle-brow author. An unlikely pair of collaborators, Housman and Maugham had little in common and were never to work together again after what Housman later described as “the mis-fire of The Venture” (Unexpected 203). An up-and-coming professional writer, Maugham had contributed stories to mainstream periodicals and published a handful of popular novels when he took on the Venture co-editorship (Van Dijck, np). As it happened, he was on the cusp of his career breakthrough as a playwright of social comedies in the vein of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900). Written in the same year as The Venture launched, Lady Frederick (1903) became a runaway hit in 1907; within a year, Maugham was rich and famous, with four successful plays running in London’s West End (Hastings 113). In contrast, Housman, who began his dramatic career at the same time as Maugham, produced his unlicensed plays in small alternative venues for the next thirty years, claiming to be “the most censored playwright in England” because of his propensity to dramatize biblical figures and royal personages (qtd in Engen 106).

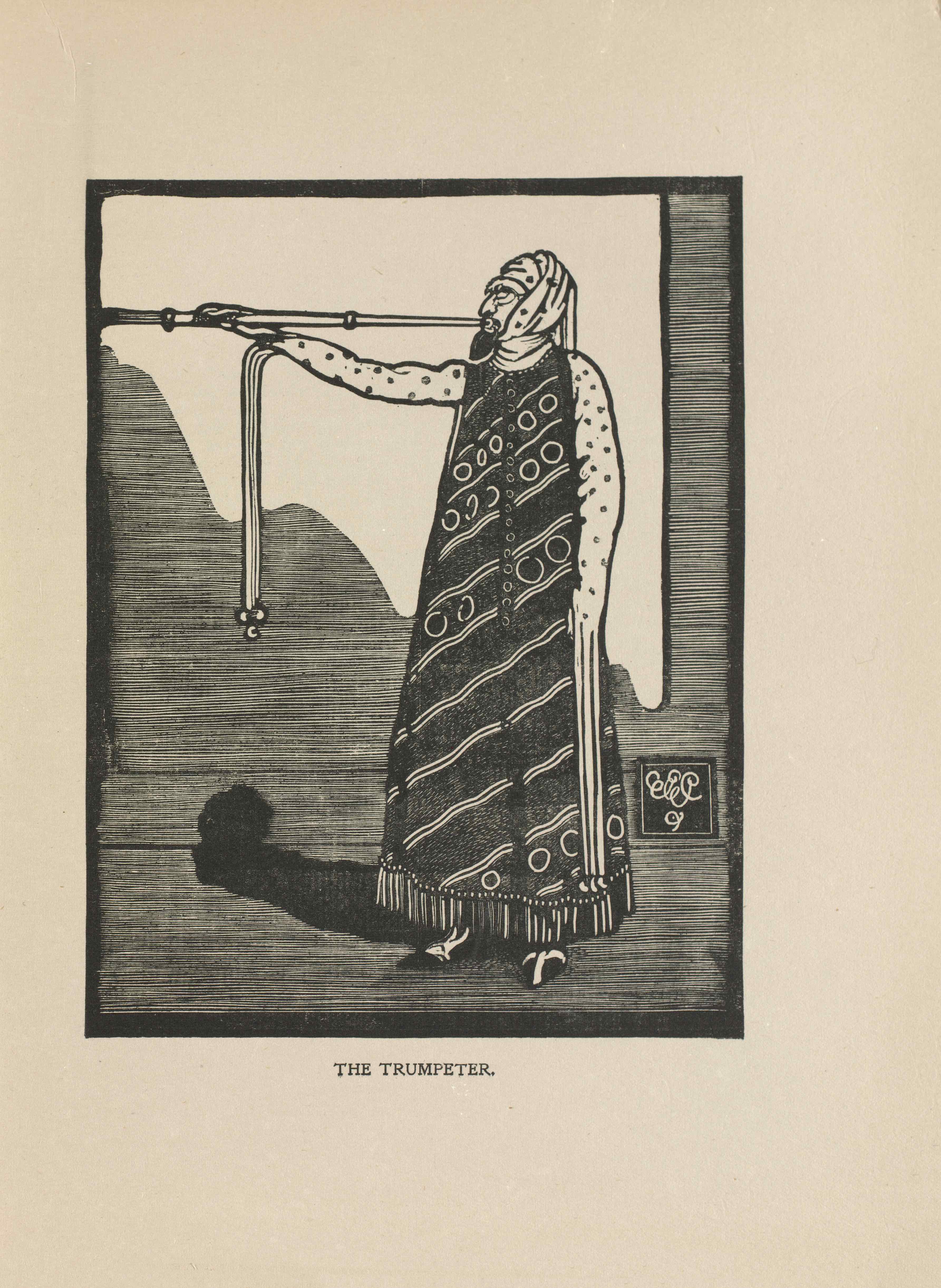

Although Baillie is known to have had strong ties with Housman, the publisher’s relationship with Maugham remains somewhat obscure. The historical record leaves little trace of their connection, but it is possible that mutual friend Netta Syrett (1865-1943), who contributed to both Venture volumes and edited the only other title Baillie published, The Dream Garden: A Children’s Annual (1905), brought him and Maugham together. In contrast, Baillie and Housman had well-established professional connections prior to their collaboration on The Venture. A year before the annual appeared, Baillie provided much-needed assistance when the Lord Chamberlain refused to grant a licence for Housman’s first play, Bethlehem, because the Virgin Mary spoke on stage (Unexpected, 188). To circumvent the need for a licence, Housman formed the “Bethlehem Society,” which involved “setting up a species of box-office for the enrolment of members” (189). Housman’s faux box office was John Baillie’s Art Gallery at 1 Princes Terrace, Hereford Road, Bayswater. Acting as “secretary” for the Society, Baillie took in the subscriptions of those who wished to see a performance of Bethlehem directed and designed by E. Gordon Craig (1872-1966), a Gallery exhibitor and Venture contributor (“Literary World,” 6). The intermedial relationship triangulating across avant-garde exhibition, print, and performance cultures at Baillie’s Gallery is signalled in Craig’s woodcut, “The Trumpeter” in The Venture (fig. 2). The engraving was one of Craig’s costume designs for Housman’s Bethlehem (Craig, Woodcuts, 35).

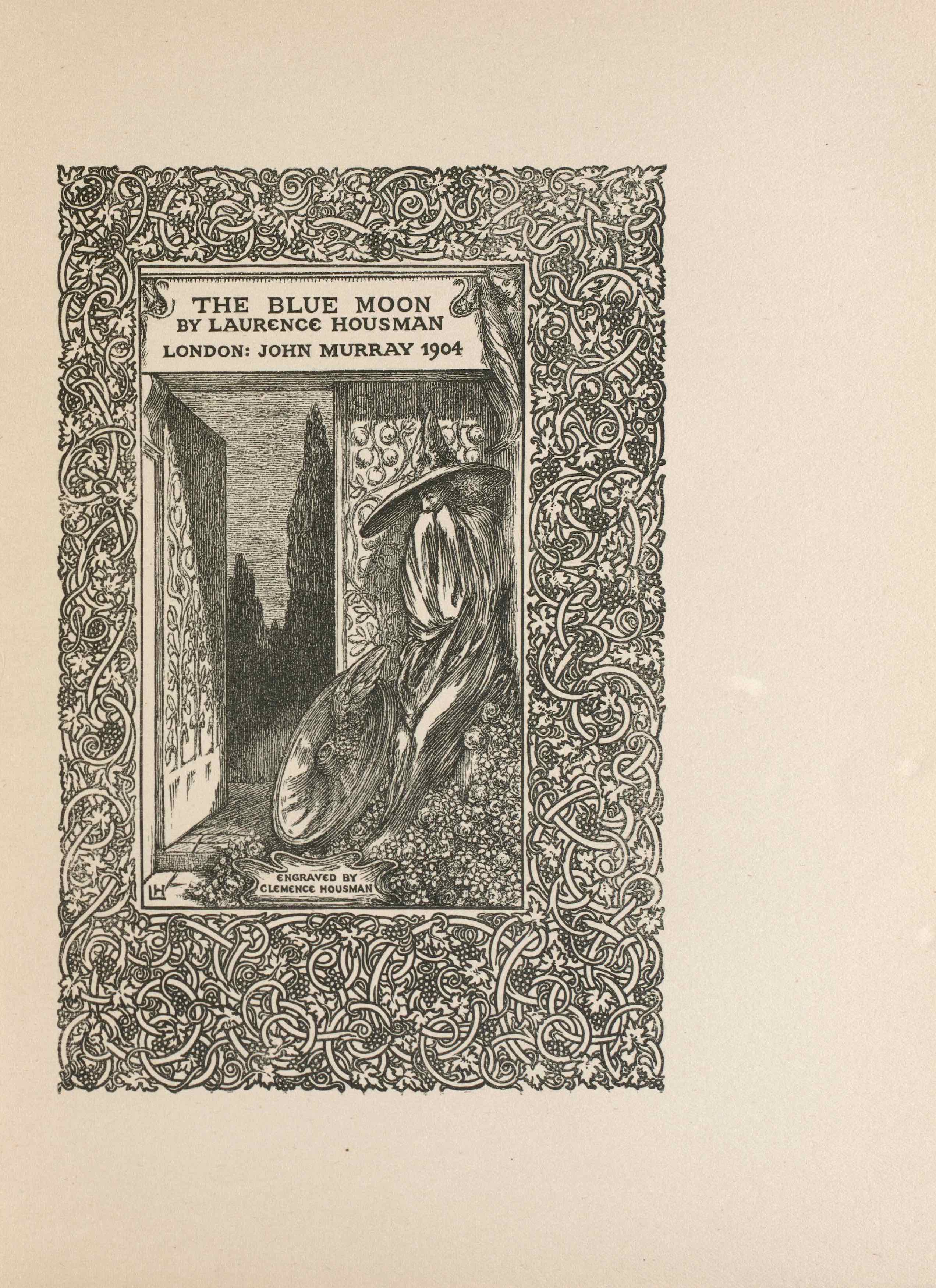

Within months of the December 1902 production of Bethlehem, Baillie’s Gallery held an exhibition of drawings by Housman and wood engravings after his designs by his sister Clemence (1861-1955), a skilled facsimile engraver (Baillie Gallery Exhibitions). Clemence Housman’s exquisite cutting of the title page for her brother’s self-illustrated book of fairy tales, The Blue Moon (1904), appears as a work of art in The Venture. As a reproductive engraver of another’s drawing, rather than an original artist executing her own design, Clemence is not given credit for her work in the Venture’s Table of Contents, but her contribution is acknowledged in an engraved cartouche on the image itself (fig. 3). Laurence regarded the title page as “proof of the extraordinary minuteness and accuracy of her engraving” (qtd in Kooistra, “Victorian Women,” 291), and may have offered it to The Venture in celebration of Clemence’s acknowledged position as one of the period’s best wood engravers (Guthrie 199; Sleigh, Wood Engraving, 43-33). In addition to engraving illustrations for her brother’s books, Clemence also engraved for James J. Guthrie at his Pear Tree Press, and it is possible that she brought printer and publisher together for the Venture project. Shortly after the Housman show, Baillie mounted an exhibition of Guthrie’s drawings at his Gallery (Baillie Gallery Exhibitions). He must have contracted the services of Guthrie’s Pear Tree Press at about the same time, spring 1903.

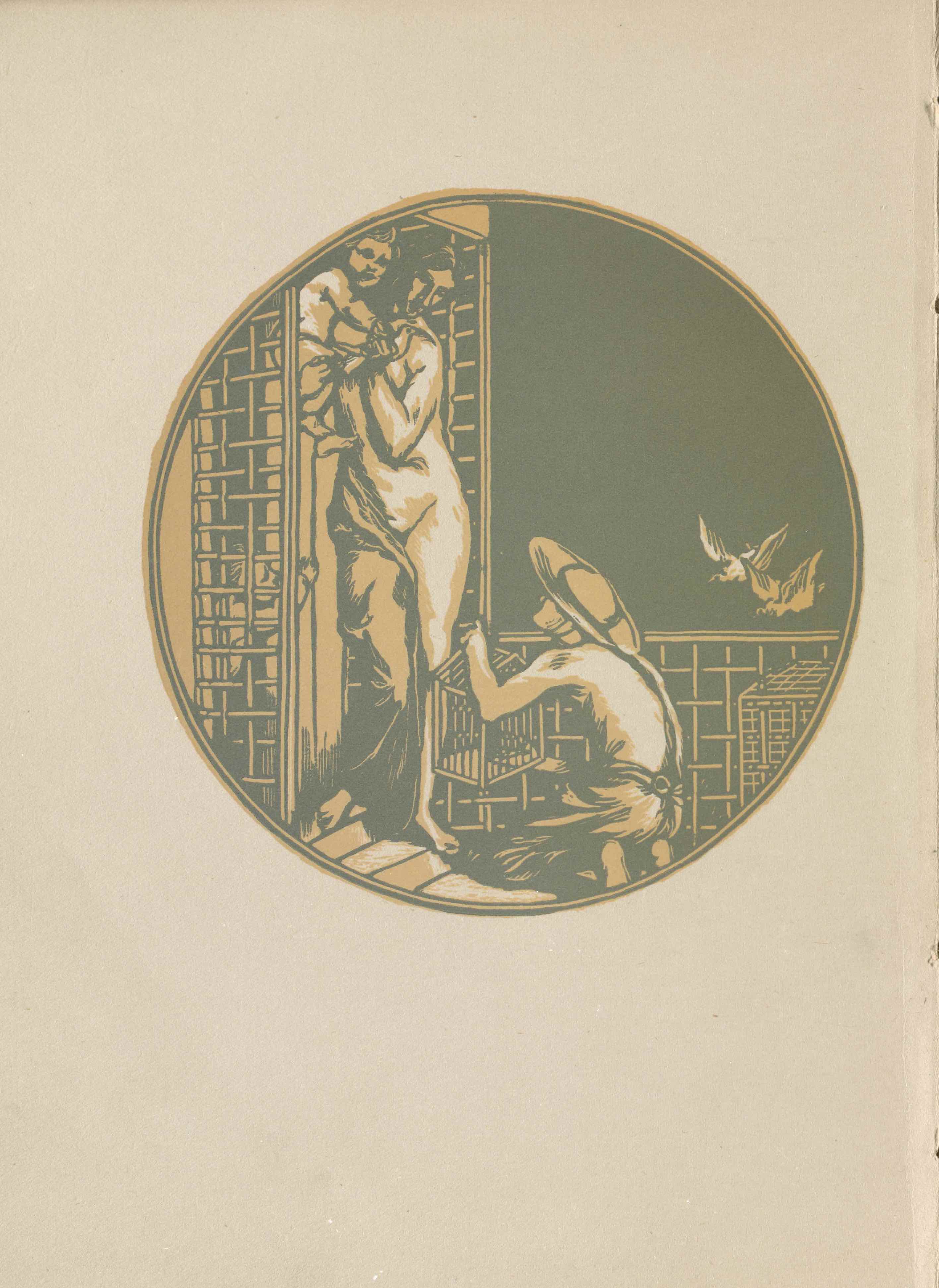

Together, Baillie’s Gallery and annual made important but under-studied contributions to the movement to revive wood engraving as a fine art. The revival had been launched in a fin-de-siècle little magazine when Ricketts and Shannon featured original woodcuts in the 1892 volume of The Dial (see Critical Introduction to The Dial). In 1898, the Dutch Gallery celebrated the revival by exhibiting prints from The Dial as fine art at London’s first “Exhibition of Original Wood Engravings” (Barlow 8; “An Exhibition,” 778-79). Five years later, Baillie advanced the cause of this ground-breaking exhibition in two ways. First, in late 1903, his Gallery showcased some of the same wood engravings, including some beautiful rondels by Ricketts and Shannon (Some Woodcuts, [i]). Second, Baillie reinforced the impact of his exhibition by foregrounding original prints by all five of The Dial’s wood-engraving artists in the first volume of The Venture.

Baillie gave Shannon’s “The Dove Cot” pride of place as the volume’s frontispiece (fig. 4). Described by a reviewer of the 1898 exhibition as representing “the revival of another variety of the art, that of the so-called chiaroscuro or camaieu printing from more blocks than one,” Shannon’s two-coloured wood engraving is printed in soft greens and golds (“An Exhibition,” 779). The print’s colours complement the muted olive hues of the decorative peacocks on the preceding endpapers, which were designed by Paul Woodroffe (1875-1954). Listed as a “Chiaroscuro Woodcut” and titled “The Porch” in Baillie’s exhibition catalogue (Some Woodcuts, [iv]), Shannon’s frontispiece provides an apt threshold image for Venture readers as they cross into the volume’s contents. The image depicts a graceful woman with an infant in her arms, standing on the steps of a latticed porch and looking down at a kneeling man holding up a bird cage, while two doves hover just beyond the garden enclosure.

Immediately following the frontispiece, Baillie presents work by Shannon’s innovative Dial colleagues. In bibliographic tribute to the foundational role The Dial played in the wood-engraving revival, Baillie positions prints by the earlier magazine’s five artist-engravers as The Venture’s first works of art. In addition to Ricketts and Shannon, these include Thomas Sturge Moore (1870-1944), Lucien Pissarro (1863-1944) and Reginald Savage (1862-1937). Moore and Pissarro each contributed a second image as well. Baillie’s selection of the volume’s fifteen wood engravings includes a full range of contemporary approaches to the art, with beautiful examples of both the detailed compositions inspired by Pre-Raphaelite illustrations (see fig. 3) and the stylized black lines and open white spaces more characteristic of modern print making (see fig. 2).

The fin-de-siècle revival promoted wood engraving as a fine art designed and executed by a single artist at the very moment that wood engraving as the craft activity of a worker reproducing someone else’s design gave way to photographic processes (Kooistra, “Victorian Women,” 287-88). Bernard Sleigh (1872-1954), who had two artworks published in The Venture, gives a history of the movement’s development in Wood Engraving Since Eighteen-Ninety (1932), where he distinguishes between the Victorian tradition of reproductive engravers represented by Clemence Housman and the modern school of artist-engravers that emerged after The Dial (vii). In 1920, the artistic movement was formalized with the founding of the Society of Wood Engravers (SWE). In addition to the pioneering engravers of The Dial, The Venture showcases some of the artists who were to become founding members of the SWE, including E. Gordon Craig and Sydney Lee (1866-1949) (Brett 12). The latter taught some of the first wood-engraving classes offered at London’s Central School of Arts and Crafts and was an influential promoter of original prints in the first half of the twentieth century (Desmet 28).

While classes in art schools undoubtedly led to the twentieth-century popularization of original wood engravings as artists’ prints, the role of artisanal presses and little magazines should not be underestimated. As Simon Brett explains, “Since the time of William Morris (1834-96) and the Kelmscott Press (1891-98)”—and, I would add, of Charles Ricketts and the Vale Press (1896-1904)—”the renewal of wood engraving has been closely linked to the rethinking of printing standards, largely by owners of private presses” (16). In addition to Clemence Housman, the volume’s sole reproductive engraver, The Venture included two women artist-engravers associated with private presses, both recent exhibitors at Baillie’s Gallery: Louise Glazier (1870-1917) and Elinor Monsell (1879-1954).

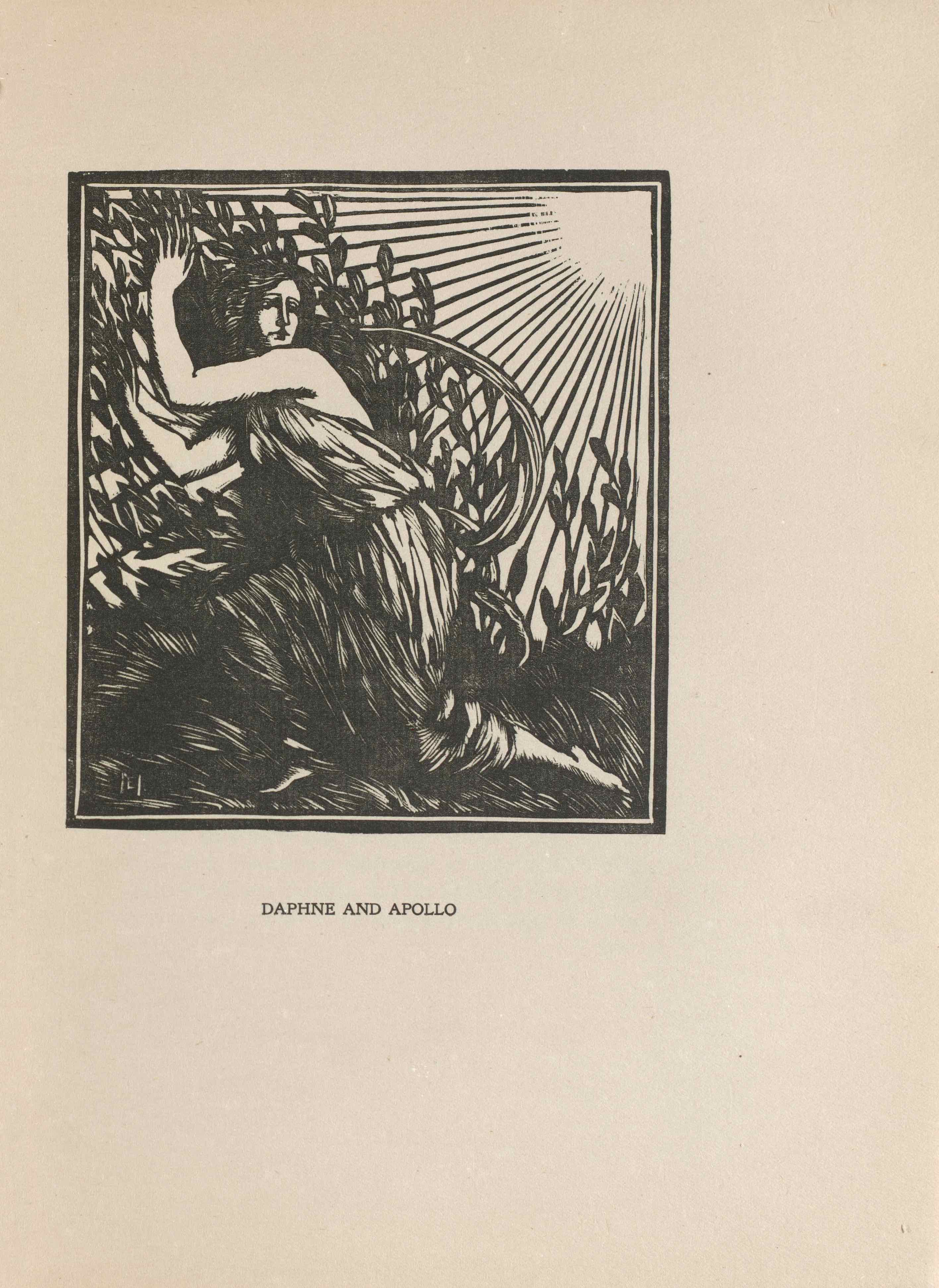

Glazier, who exhibited in the same Baillie exhibition as Clemence and Laurence Housman in 1903, published A Book of Thirty Woodcuts with the Unicorn Press later that year. Her contribution to The Venture, “The Death of Pan,” is a dramatic composition foregrounding the goat-legged god in a wood, observing the birth of the Christ child. Monsell’s work appeared in a Baillie exhibition featuring women artists. Although the Athenaeum’s review of the women’s art was not generally positive, the critic declared “Miss Elinor Monsell is on a different plane from these,” praising her wood engravings for honoring the medium’s limitations (“Mr. Baillie’s Gallery,” 410). With its dramatic diagonals and stark black lines emerging out of white space, Monsell’s “Daphne and Apollo” is one of The Venture’s most compelling images (fig. 5). A talented printmaker involved in the Irish Revival, Monsell designed the logo for the Abbey Theatre, the print mark for the Dun Emer Press (“Drawn to the Page,” np), and the opening image for the first number of Pamela Colman Smith’s The Green Sheaf (1903). Monsell also contributed wood engravings to some of Ricketts’s Vale Press books before a fire compelled the firm to close in 1904.

The Venture’s art contents demonstrate the close relationship between the private press movement and the wood-engraving revival. Pissarro’s contributions, “Queen of the Fishes” and “The Crowning of Esther,” come from the first two books published by his Eragny Press (1894 and 1896 respectively). Ricketts’s rondel, “Psyche’s Looking Glass,” derives from an early Vale Press edition of Apuleius’s classic tale, The Most Pleasant and Delectable Tale of the Marriage of Cupide and Psyches (1897), where the image is entitled “Psyches’ Invisible Ministrants” (Van Capelleveen, No. 615). Other Venture contributors were associated with Guthrie’s Pear Tree Press and Charles R. Ashbee’s (1863-1942) Essex House Press (1898-1904), both run on arts-and-crafts principles. In addition to their work at the Pear Tree Press, Clemence Housman and Reginald Savage joined Bernard Sleigh and Paul Woodroffe as engravers for Essex House.

![FFigure 6. Reginald Savage, "John Woolman," The Venture, vol. 1, 1903, p. [viii].](https://1890s.ca/wp-content/uploads/VV1-savage-woolman.jpg)

As a relief art, wood engraving has always been intimately associated with letterpress, so it is no surprise that most of the prints Baillie selected for The Venture originated in books. Housman’s “Blue Moon” title page appeared in advance of his forthcoming fairy-tale collection, while Savage’s “John Woolman” and Woodroffe’s “The World is Old Tonight” were both taken from recent publications; Baillie printed their respective publisher’s permission on the Contents page. Originally the frontispiece for A Journal of the Life and Travels of John Woolman in the Service of the Gospel, printed at the Essex House Press in a limited edition for Edward Arnold in 1901, Savage’s “John Woolman” is the volume’s first image after the frontispiece (fig. 6). Baillie’s editorial placement seems inspired as much by his desire to headline one of the Dial’s coterie of artists as by the actual subject of Savage’s print. Woolman (1720-1772) was an Anglo-American Quaker who campaigned tirelessly for the abolition of slavery; his Journal recorded his “inner spiritual life” as he struggled in this cause (“John Woolman”). Savage’s black-and-white image of the Quaker engaging with New England shipowners in an effort to convert them to the abolitionist cause sits somewhat uneasily across from the literary piece on the recto of the first page opening. In contrast to Savage’s “Woolman” engraving, John Masefield’s (1878-1967) sonnet, “When Bony Death Has Chilled her Gentle Blood” (mistitled “Beauty’s Mirror” on the Contents page), offers a worldly celebration, in the courtly verse tradition, of his beloved’s ephemeral beauty and his poem’s immortality. Together, image and text signal two of the volume’s contrasting thematic strands: spirituality and social consciousness, sensuality and desire.

The literary contents co-edited by Housman and Maugham are of exceptionally high quality, but—as the leading item by Masefield suggests—not necessarily as experimental or trend-setting as the volume’s wood engravings. The issue contains twenty-two pieces of literature: eight poems, seven stories, five essays, and two plays. Masefield, who became Britain’s Poet Laureate in 1930, wrote two of the eight poems. John Gray (1866-1934), the decadent poet of Silverpoints (1893) whose poetry had appeared in The Dial, The Pageant, and The Savoy, contributed “A Phial.” Ordained a Catholic priest in 1901, Gray continued to publish his work in magazines throughout his life and was one of a handful of returning contributors to the Venture’s second volume (King, np). Catholic poet and mystic Francis Thompson (1859-1901), whose poetry collections Housman had designed for The Bodley Head in the 1890s, was represented posthumously with “Marriage in Two Moods.” Laurence Binyon (1869-1943), a poet and art historian connected to the wood-engraving movement through his 1902 publication of William Blake’s woodcuts in photographic facsimile, contributed a sonnet. Stephen Phillips (1864-1915), an actor known for his verse dramas who became editor of the Poetry Review in 1913, contributed a short lyric.

Thanks to Housman’s literary connections, two of the period’s most highly regarded poets, neither of them part of the little magazine community, appeared in The Venture’s first volume. When Housman invited well-known writer Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) to contribute a poem to the annual, he sent in “The Market Girl.” The two-stanza lyric was part of Hardy’s “Casterbridge Fair” series of seven poems, only one of which had previously been published: in 1902, “The Ballad Singer” appeared in The Cornhill, a mainstream literary magazine (Bailey 225-26). Ultimately, the verses were published in the sub-section “A Set of Country Songs” in Hardy’s Time’s Laughingstocks and Other Verses in 1909. The Venture volume was also distinguished by a rare offering by A.E. Housman (1859-1936), the celebrated poet of A Shropshire Lad (1896) who typically eschewed magazine publication. As he explained to his brother, he only contributed to The Venture “because you were the editor.” Laurence had asked Alfred, a classical scholar, for an essay, but the elder Housman sent two poems instead, inviting the editor to select the one he considered “the least imperfect” (qtd in Alfano, np.). Laurence chose “The Oracles,” whose “classical focus,” as Veronica Alfano observes, somewhat “sets it apart from the other literary offerings in The Venture’s first volume” (ibid).

While thematic interests and aesthetic styles vary, both visual and verbal contents in The Venture frequently engage with spirituality, taking subjects drawn from pagan and Christian stories alike. Introduced by the leading image of “John Woolman,” religious tropes appear in Christmas-themed pictures by Glazier and Woodroffe, as well as in poems by Gray and Thompson and essays by Alice Meynell (1847-1922) and G.K. Chesterton (1874-1976). Meynell, who went on to found the Catholic Women’s Suffrage Society, contributed a piece on architectural aesthetics addressed “To Any Householder.” Chesterton, a regular columnist for the Illustrated London News best-known today for his Father Brown stories, explored the benefits of restrictions, religious and otherwise, in “The Philosophy of Islands.”

In contrast to these philosophical musings, Irish Literary Society member John Todhunter (1839-1916) celebrated the revival of period instruments, such as the psalteries made by Arnold Dolmetsch (1858-1940), in his essay on “A Concert at Clifford’s Inn.” His subject was of great topical interest to members of London’s little magazine community, many of whom were involved in the recently formed and short-lived Masquers Society (see Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf, No. 3). Gordon Bottomley (1874-1948), whose own verse, like that of Masefield, was influenced by this “bardic revival,” attended the Clifford’s Inn lectures. Here, according to Bottomley, W.B. Yeats (1865-1939) spoke on the art of chanting, accompanied “by actress Florence Farr with a psaltery and … Pamela Colman Smith without a psaltery” (qtd in Schuchard 137). Notably, Bottomley, Farr, and Smith became contributors to the second Venture.

Two other essays in the volume reassess the significance of historical persons rather than historical instruments and performative methods. Stephen Gwynn (1864-1950) extols “The Genius of Pope,” while sexologist Havelock Ellis (1859-1939) argues for the significance of Madame de Warens (1699-1762), mistress of Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). Clarifying, correcting, and commenting on the historical record, Ellis’s Venture essay is akin to his earlier Savoy contributions on Casanova, Nietzsche, and Zola. His essay enhances the annual’s high-quality prose as well as its international and historical reach. Surprisingly, Ellis also has a connection to the woodcut revival: in 1932, Sleigh dedicated Wood Engraving Since Eighteen-Ninety to him as “the last of the great Victorians” (154).

The fictional contents of The Venture are almost equally divided between the modern short story of mood and character set in contemporary milieus and fanciful tales of exotic personages taking place in remote settings. Short stories are offered by two former Yellow Book authors: the urbane popular novelist E. F. Benson (1867-1940) and New Woman writer Netta Syrett. The latter’s “Poor Little Mrs. Villiers” explores the complicated character of a woman with a questionable past who leverages her girlish appearance to prey on a gullible and wealthy younger man. In “Jill’s Cat,” Benson represents the deeply affectionate, cross-species relationship between the titular fox-terrier and her unnamed feline friend.

May Bateman (1872-1938) and Charles Marriott (1869-1957) provide the volume’s other two realist stories. An extract taken from her novel of the same title (published in 1908), Bateman’s “Richard Farquharson” exposes the dysfunctional relationship of a mother and son. In addition to her popular novels, Bateman was a prolific magazine contributor who served as a war correspondent for the Daily Express during the Boer War. In 1910 she became the manager of the world’s first bank run by women, for women (“May Bateman”). Marriott, who was educated at the National Art Training School, had a good eye for details, evident in the gritty representation of urban life in his “Open Sesame.” Despite its title, the story is not an exotic Orientalist tale, but rather the record of the last days of an elderly Cornish man forced to live in the sordid surroundings of Packer’s Rents in London, where his widowed daughter-in-law, a factory worker, draws on his annuity to extend the family’s meagre income.

These four stories, grounded in the quotidian details of contemporary life and social relationships, make a strong contrast to the three fantastical tales offered by Richard Garnett (1835-1906), Shadwell Boulderson (1878-?), and co-editor Housman. An author, librarian, and translator, Garnett had appeared in numerous Yellow Book volumes and was one of John Lane’s Bodley Head authors. “The Merchant Knight” is his translation of a sixteenth-century romance about a young Portuguese trader who makes a fortune and marries an English princess. Boulderson was a childhood friend of the Housman family in Bromsgrove with whom Laurence retained close ties. In 1896, Housman dedicated All-Fellows: Seven Legends of Lower Redemption to “my friend and dear fellow, Shadwell Boulderson”; a decade later, he inscribed a copy of his Pierrot play, Prunella, or Love in a Dutch Garden, “To my dear Shad, with Love, LH, Christmas 1906” (inscribed copy advertised on AbeBooks). Born and raised in India before returning to England with his family, Boulderson may be drawing on folklore he heard as a child in his contribution to The Venture. His “An Indian Road-Tale” is a disturbing story about two travelers who kill the feared being known as the “Kir” when it transforms into a woman. Housman’s own offering, “Proverbial Romances,” consists of nine short scenes in which the relationships and challenges of fairy-tale characters provide symbolic insight into the human condition. These themes are complemented by his “Blue Moon” title page, which punctuates his proverbial tales. In contrast to the array of failed heterosexual relationships enumerated in his “Proverbs,” Housman’s title-page illustration for his Blue Moon collection of fairy tales gestures toward other romantic possibilities. In this collection, Housman symbolically imagines a world in which same-sex love might be understood as natural and beautiful as the titular “blue moon” (Kooistra, “Victorian Women” 291-4).

The volume’s editorial sequence is interesting here, as Housman’s verbal and visual contributions appear immediately before the work of his co-editor Maugham. The latter’s “Marriages are Made in Heaven” is one of two plays in the volume, both critical of the upper-middle class marriage market. The other was provided, at Maugham’s request, by Violet Hunt (1862-1942), a prolific author and leading feminist who had recently been romantically involved with Maugham (Ledbetter, np). Written in 1898, Maugham’s ironically titled play became the first of his dramatic works to be performed on stage when Max Reinhardt produced a German translation of it in Berlin in January 1902 (Hastings 81). Publishing the original English version in The Venture allowed Maugham to reach a new audience for his play just as he was trying to break into London’s theatre scene. From an editorial perspective, “Marriages are Made in Heaven” also makes an apt dramatic pairing with “The Gem and its Setting,” Hunt’s exploration of an unromantic and unlikely courtship. Hunt continued to be on friendly terms with Maugham after her brief affair with the bisexual author ended, dedicating White Rose of Weary Leaf to him in 1905. Fourteen years later, Maugham based the character of Rose Waterford in Moon and Sixpence on her (Hastings 90). Hunt also retained friendly relations with Housman, who, unlike the misogynist Maugham, shared her feminist convictions and political activism in the cause of woman suffrage.

Despite the excellence of The Venture’s contents, the beauty of its material format, and its unique relationship with a celebrated London art gallery, the magazine failed to generate sufficient sales to pay its contributors and to retain its editorial team and printer. As Housman ruefully reflected in his autobiography, “My one experiment in editing was not a success, though I think it deserved to be” (Unexpected 202). Neither he nor Maugham joined Baillie in bringing out the next year’s issue, which was printed by the Arden Press. The optimistic Baillie did, however, have good reason to hope for a better future for his annual: the first Venture was a critical success, if not a commercial one. Naming it “A Happy Venture,” The Daily Chronicle praised its contents as experimental, modern, and forward-looking, and “hope[d] the authors and artists …will ‘Venture’ again and again” (Advertisement for The Venture, 1904, [ii]). The critic for To-Day claimed its woodcut artists alone would “prove an irresistible attraction” to consumers and enthused: “All this for five shillings, nicely printed in black letter type, with wide margins, is not only good artistically but cheap commercially” (Advertisement for The Venture, 1904, [iii]). Reflecting on The Venture’s failure to sell enough copies to make a profit, Housman later wrote: “The whole thing was, of course, too highbrow to be popular: perhaps had it been published at a guinea instead of at five shillings, it would have done better” (Unexpected, 203). Possibly hoping he might raise The Venture’s market value by upping its price, John Baillie offered Volume 2 for sale at seven shillings sixpence. When it appeared (somewhat late) for the next year’s gift book season, however, the new Venture fared no better with the public, and its second number would prove to be the short-lived serial’s last.

©2023 Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, FRSC, Emerita Professor of English and Senior Research Fellow, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities

Works Cited

- Advertisement for The Venture, 1904. Advertising Supplement, pp. [ii-iv]. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-advertisements/

- Advertisement for The Venture. Athenaeum, no. 3969, 21 November 1903, p. 667. British Periodicals, C19 Index.

- Alfano, Veronica. “A.E. Housman (1859-1936).” Y90s Biographies, 2021. https://1890s.ca/aehousman_bio/

- Apuleius. The Most Pleasant and Delectable Tale of the Marriage of Cupide and Psyches, translated by William Addington. Vale Press, 1897.

- Baillie Gallery Exhibitions. Exhibition Culture in London 1878- 1908, ©2006 University of Glasgow, https://www.exhibitionculture.arts.gla.ac.uk/gall_exhlist.php?gid=797

- Bailley, J.O. The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: A Handbook and Commentary. University of North Carolina Press, 1970.

- Barlow, Vincent. “An Important Anniversary.” Imaginative Book Illustration Society Newsletter, No. 10, Winter 1998, pp. 8-19.

- Bateman, May. “Richard Farquharson.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 161-72. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-bateman-farquharson/

- Benson, E. F. “Jill’s Cat.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 175-84. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-benson-cat/

- Binyon, Laurence. “The Clue.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 158. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-binyon-clue/

- —. William Blake: Being all his Woodcuts Photographically Reproduced in Facsimile. London: Longmans, Green, and Company, 1902.

- Boulderson, Shadwell. “An Indian Road Tale.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 33-35. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-boulderson-road-tale/

- Brett, Simon. “Setting the Scene: British Wood Engraving in History.” Scene Through Wood: A Century of Modern Wood Engraving, edited by Anne Desmet, Ashmolean Museum, 2020, pp. 11-23.

- Chesterton, G. K. “The Philosophy of Islands.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 2-9. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-chesterton-islands/

- Claes, Koenraad. The Late-Victorian Little Magazine. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Craig, E. Gordon. “The Trumpeter.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 75. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-craig-trumpeter/

- —. Woodcuts and Some Words. With an Introduction by Campbell Dodgson. London: J. M. Dent, 1924.

- Desmet, Anne, ed. Scene Through Wood: A Century of Modern Wood Engraving, Ashmolean Museum, 2020.

- The Dial, vol. 2, 1892. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/dial2-all/

- Drawn to the Page: Irish Artists and Illustration 1830-1930. Trinity College Dublin Library. https://dttp.tcd.ie/artist/35

- The Dream Garden: A Children’s Annual, edited by Netta Syrett. London: John Baillie, 1905.

- Ellis, Havelock. “Madame de Warens.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 136-157. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-ellis-warens/

- Engen, Rodney. Laurence Housman. Catalpa Press, 1983.

- “An Exhibition of Original Wood-Engravings.” The Saturday Review, 10 December 1898, pp. 778-79.

- Garnett, Richard. “The Merchant Knight.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 77-111. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-garnett-merchant-knight/

- Glazier, Louise. “The Death of Pan.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 97. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-glazier-pan/

- —A Book of Thirty Woodcuts by Louise Glazier. Unicorn Press, 1903.

- Gray, John. “The Phial.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 233-34. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-gray-phial/

- Guthrie, James J. “The Wood Engravings of Clemence Housman.” Print Collectors’ Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 2, April 1924, pp. 190-204.

- Gwynn, Stephen. “The Genius of Pope.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 40-50. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-gwynn-pope/

- Hardy, Thomas. “The Market Girl.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 10. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-hardy-market-girl/

- —Time’s Laughingstocks and Other Verses. London: Macmillan, 1909.

- Hastings, Selena. The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham. John Murray, 2010.

- Housman, A.E. “The Oracles.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 39. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-ae-housman-oracle/

- —. A Shropshire Lad. London: Kegan Paul, 1896.

- Housman, Laurence. All-Fellows: Seven Legends of Lower Redemption. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Co, 1896.

- —. “The Blue Moon.” Engraved by Clemence Housman. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 207. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-housman-moon/

- —. The Blue Moon. With wood engravings by Clemence Housman after the author’s designs. London: John Murray, 1904.

- —. “Proverbial Romances,” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 187-206. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-housman-romances/

- —. The Unexpected Years. London: Jonathan Cape, 1937.

- Housman, Laurence and Granville Barker. Prunella, or Love in a Dutch Garden. London: A. H. Bullen, 1906.

- Hunt, Violet. “The Gem and Its Settings.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 115-128, Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-hunt-gem/

- —. White Rose of Weary Leaf. London: William Heinemann, 1908.

- “John Woolman.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Woolman

- Kains-Jackson, Charles. “The Work of Laurence Housman.” Book-Lover’s Magazine, 1908. Reprinted in Laurence Housman, by Rodney Engen, Catalpa Press, 1983, pp. 139-147.

- King, Frederick. “John Gray (1866-1934).” Y90s Biographies, 2019. https://1890s.ca/gray_bio/

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Critical Introduction to Volume 2 of The Dial (1892).” Dial Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/dialv2_critical_introduction/

- —. “Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf, No. 3.” Green Sheaf Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/gsv3_introduction/

- —. “Laurence Housman (1865-1959).” Y90s Biographies, 2019. https://1890s.ca/housman_bio/

- —. “Victorian Women Wood Engravers: The Case of Clemence Housman.” Women, Periodicals, and Print Culture in Britain, 1830s-1900s: The Victorian Period. Edited by Alexis Easley, Clare Gill, and Beth Rodgers, Edinburgh University Press, 2019, pp. 277-300.

- Laurence Housman Papers, Seymour Adelman Collection, Bryn Mawr College Library.

- Ledbetter, Kathryn. “Violet Hunt.” British Short Fiction Writers, 1915-1945. Gale’s Dictionary of Literary Biography, 1996.

- Lee, Sydney. “The Gabled House.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 185. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-lee-house/

- “The Literary World.” St. James Gazette, 9 August 1902, p. 6.

- Marriott, Charles. “Open Sesame.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 13-28. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-marriott-sesame/

- “May Bateman.” The Oxford Companion to Edwardian Fiction, edited by Sandra Kemp, Charlotte Mitchell, and David Trotter. Oxford Reference Online, 2005.

- Masefield, John. “Blindness.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 74. Venture Digital Edition. https://1890s.ca/vv1-masefield-blindness/

- —. “When Bony Death has Chilled her Gentle Blood.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 1. Venture Digital Edition. https://1890s.ca/vv1-masefield-mirror/

- Maugham, W. Somerset. “Marriages are Made in Heaven.” The Venture, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 209-230. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-maugham-heaven/

- —. The Moon and Sixpence. London: William Heinemann, 1919.

- Meynell, Alice. “To Any Householder.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 31-36. Venture Digital Edition. https://1890s.ca/vv1-meynell-householder/

- “Mr. Baillie’s Gallery.” The Athenaeum, No 3935, 28 March 1903, p. 410.

- “Mr. John Baillie’s Gallery,” The Times, 25 September 1903, p. 11.

- Monsell, Elinor. “The Book-worm.” The Green Sheaf, No. 1, 1903, [p. ii]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV1-monsell-bookworm/

- —. “Daphne and Apollo.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 159. Venture Digital Edition. https://1890s.ca/vv1-monsell-apollo/

- Moore, Thomas Sturge. “Pan and Psyche.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 29. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-moore-psyche/

- —. “Playfellows.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 113. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-moore-playfellows/

- Phillips, Steven. “Earth’s Martyrs.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 112. Venture Digital Edition. https://1890s.ca/vv1-phillips-martyrs/

- Pissarro, Lucien. “The Crowning of Esther.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 129. Venture Digital Edition. https://1890s.ca/vv1-pissarro-esther/

- —. “Queen of the Fishes.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 37. Venture Digital Edition. https://1890s.ca/vv1-pissarro-fishes/

- Ricketts, Charles. “Psyche’s Looking Glass.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 11. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-ricketts-looking-glass/

- Savage, Reginald. “John Woolman.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. [viii]. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-savage-woolman/

- Schuchard, Ronald. The Last Minstrels: Yeats and the Revival of the Bardic Arts. Oxford UP, 2010.

- Shannon, Charles. “The Dove Cot.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 231. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-frontispiece-shannon/

- Sleigh, Bernard. “The Bather.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. [ii]. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-sleigh-bather/

- —. Wood Engraving Since Eighteen-Ninety. London: Pitman, 1932.

- Some Woodcuts by Chas. S. Ricketts, Lithographs by Chas. Hazlewood Shannon, and Fans by Mrs. L. Murray Robertson. Exhibition Catalogue, John Baillie’s Gallery, 1903. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, University of Delaware Libraries, Museums, and Press.

- Syrett, Netta. “Poor Little Mrs. Villiers.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 53-73. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-syrett-villiers/

- Thompson, Francis. “Marriage in Two Moods.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 131-32. Venture Digital Edition https://1890s.ca/vv1-thompson-marriage/

- Todhunter, John. “A Concert at Clifford’s Inn.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 235-249. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-todhunter-inn/

- Van Capelleveen, Paul. No. 615: Charles Ricketts’s Illustrations of Cupid and Psyche, May 17, 2023. Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon. Accessed 22 May 2023. http://charlesricketts.blogspot.com/

- Van Dijk, Cedric. “W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1966).” Y90s Biographies, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/maugham_bio/

- “The Venture.” The Sketch, vol. 44, no. 565, 25 Nov. 1903, p. 184. Pro Quest, British Periodicals.

- Whistler, James McNeill. Mr. Whistler’s Ten O’Clock. Boston: Houghton Mifflin/The Riverside Press, 1888.

- Woodroffe, Paul. “The World is Old To-night.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 173. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv1-woodroffe-world/

MLA citation:

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Critical Introduction to The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature Volume 1 (1903).” Venture Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2023. https://1890s.ca/VV1-introduction/