XML PDF

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

TO THE SAVOY (1896)

The origins of The Savoy can be traced to the arrest of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) on charges of “gross indecency” in April 1895. When word spread that Wilde had been carrying a “yellow book” at the time that the police had detailed him, an angry crowd descended upon the offices of John Lane, assuming the volume in question could only have been a copy of the magazine he published, The Yellow Book. This was not, in fact, the case: Wilde wasn’t carrying a copy of the magazine (which he avidly disliked); he was carrying a French novel, the covers of which were printed in yellow. Disregarding the crowd’s mistaken assumption, a group of the magazine’s more conservative contributors, including Alice and Wilfrid Meynell and William Watson, called on the publisher to reject any association not only with Wilde, but with the decadent school of art and literature with which he was associated. To this end, they demanded the dismissal of Aubrey Beardsley, the magazine’s high-profile art editor. Beardsley’s work, indeed, had been entangled with the fortunes of Wilde for some years. The artist’s rapid rise to public notice had been propelled in part by his illustrations for the English version of Wilde’s banned play, Salomé, brought out by John Lane and Elkin Mathews at The Bodley Head in 1894, only two months before the publishers launched The Yellow Book. Lane was in a difficult position. He admired and respected Beardsley’s talent, and was well aware that The Yellow Book’s success was owed in part to the artist’s attention-grabbing covers and exquisite pen-and ink drawings. But such was the popular outrage occasioned by Wilde’s arrest that Lane felt he had no choice. Beardsley was dismissed and his contributions to the April issue were laboriously excised even though the contents had already been set in type (Kooistra and Denisoff, Introduction to The Yellow Book vol. 5).

While many writers and artists lamented the loss of Beardsley from the pages of The Yellow Book, for Leonard Smithers it was an opportunity. Described by Wilde as “the most learned erotomane in Europe” (qtd. in Sturgis 251), Smithers was a solicitor from Sheffield who had given up his law practice to pursue a career as a dealer in rare books. In the late 1880s he assisted Sir Richard Burton, the famed explorer and linguist, with the publication of his translations of oriental erotica, including the Kama Sutra and The Arabian Nights, and the success of these ventures led him to become a publisher of high-brow pornography. With The Yellow Book seemingly in retreat, Smithers felt there might be an opening in the print market for a well-produced magazine of art and literature, especially if it featured the kind of avant-garde work that other periodicals were now increasingly reluctant to publish. He approached the poet and essayist Arthur Symons to serve as editor. Though Symons had little experience running a magazine, he was nonetheless a reasonable choice. Smithers had published Symons’s third volume of verse, London Nights (1895), after several other presses, including Lane’s, had rejected it. As a result, the two, though very different in temperament and social class, had a good working relationship. Moreover, Symons had connections among many of the most important young writers of the period, including members of the Rhymers’ Club, something the provincial solicitor-turned-pornographer lacked. On his side, Symons saw not only the possibility of an escape from his impoverished life as a poet and essayist, but also the opportunity to promote the forward-looking literature and art of his friends and peers. He readily agreed to the proposal.

At Smithers’s suggestion, Symons sought out Beardsley in his Pimlico apartment, with an eye to enlisting him as art editor. In his memoir, the newly-appointed editor recalls finding the artist, who suffered from a debilitating case of tuberculosis, “lying on a couch, horribly white” (Symons, Memoirs 170). Symons feared that he had perhaps “come too late” (170), that the artist was not long for this world. But the prospect of helping to produce a new periodical to compete with that of his erstwhile employer seemed to revive Beardsley’s flagging spirits; he, too, quickly agreed to take up the new venture.

The initial plans for the periodical were worked out over the course of the summer of 1895. Despairing of the increasingly reactionary cultural climate in England in the wake of Wilde’s arrest, Smithers, Symons, Beardsley, and a group of other artists and writers decamped to the French coastal town of Dieppe (an account of which appears in Volume 1). “It was,” Symons would later admit, “to have been something of a rival to The Yellow Book, which had by that time ceased to mark a movement and had become little more than a publisher’s magazine” (Memoirs 170). The two publications would, indeed, have much in common. Like The Yellow Book, The Savoy would give equal weight to letterpress and visual art and provide a separate table of contents for each. Moreover, like its rival, The Savoy would appear not as a disposable commodity, in the manner of a popular periodical like The Strand or Pearson’s Monthly, but in a book format, with stiff board covers, high-quality paper, and superb reproductions of art. Following the success of The Century Guild Hobby Horse (1884-94), this format had become, by the 1890s, closely associated with the idea of the fine art magazine, and was adopted not only by The Yellow Book and The Savoy but also by other little magazines of the period, including The Evergreen (1895-86), The Pageant (1896/97), and The Venture (1903/5). And, like The Yellow Book, The Savoy would eschew monthly publication, which was associated with six-penny magazines and serialized novels, in favour of the seemingly more dignified temporality of quarterly publication.

There were, however, be some notable differences between The Savoy and its rival. Where The Yellow Book sold for 5 shillings, making it relatively expensive for a magazine, Smithers calculated that he could sell The Savoy for 2 shillings and 6 pence without impairing its printing quality. Such pricing would make The Savoy more competitive in the crowded market for periodical literature and art, but it also meant that the per-copy cost of production was scarcely higher than the wholesale price offered to the shops and booksellers who elected to stock the new title (Nelson 79). It would therefore take substantial sales to make a reasonable profit, a fact that Symons was later to identify as a key factor in the magazine’s failure (“A Literary Causerie”). Beyond the retail price, there were also several differences in editorial policy. The Savoy permitted some illustrations of texts to be set up on the same page; art was not always segregated as a standalone work. Furthermore, The Savoy allowed for limited serial publication, often publishing longer works, such as William Butler Yeats’s essay on William Blake, or Beardsley’s unfinished novel Under the Hill, in installments over several issues. The Savoy also did not restrict its contributor list to contemporary authors and artists, but made room for admired predecessors, like Blake and D.G. Rossetti. The Savoy also included advertisements for publications that extended beyond the publisher’s own list and for products other than print matter. The Savoy thus borrowed much from The Yellow Book and other little magazines of the period, but was in many regards a distinct publication.

The exact origins of the magazine’s name are uncertain. Symons claims that it was Beardsley’s idea to call it The Savoy (Memoir 170), though later historians and biographers, such as Matthew Sturgis, have given the credit to the artist’s sister, Mabel, who joined the company in Dieppe for several days in late August and early September (Sturgis 256). Regardless of which Beardsley came up with it, the name was evocative. In the first instance, it followed the practice of magazines being named after the street or district in which they were published (e.g. The Strand or The Pall Mall Gazette). Smithers’s new offices in Arundel Street were in a neighbourhood often referred to as “the Savoy” as it was home to a well-known theatre of that name. But “Savoy” was also the name of a fashionable new hotel, one that since its opening in 1889 had become virtually synonymous with elegance and sophistication, owing to its extensive use of electric lighting and the haute cuisine of its famed restaurant. There was, too, the fact—well-known among London’s artists and writers—that the hotel had been where Wilde conducted many of the assignations with young men that led to his arrest. The name thus gestured toward the conventional (naming a magazine for the district in which it was published) while subtly encoding a more decadent allusion for those who were “in-the-know,” a rhetorical double gesture that would become a salient feature of the periodical.

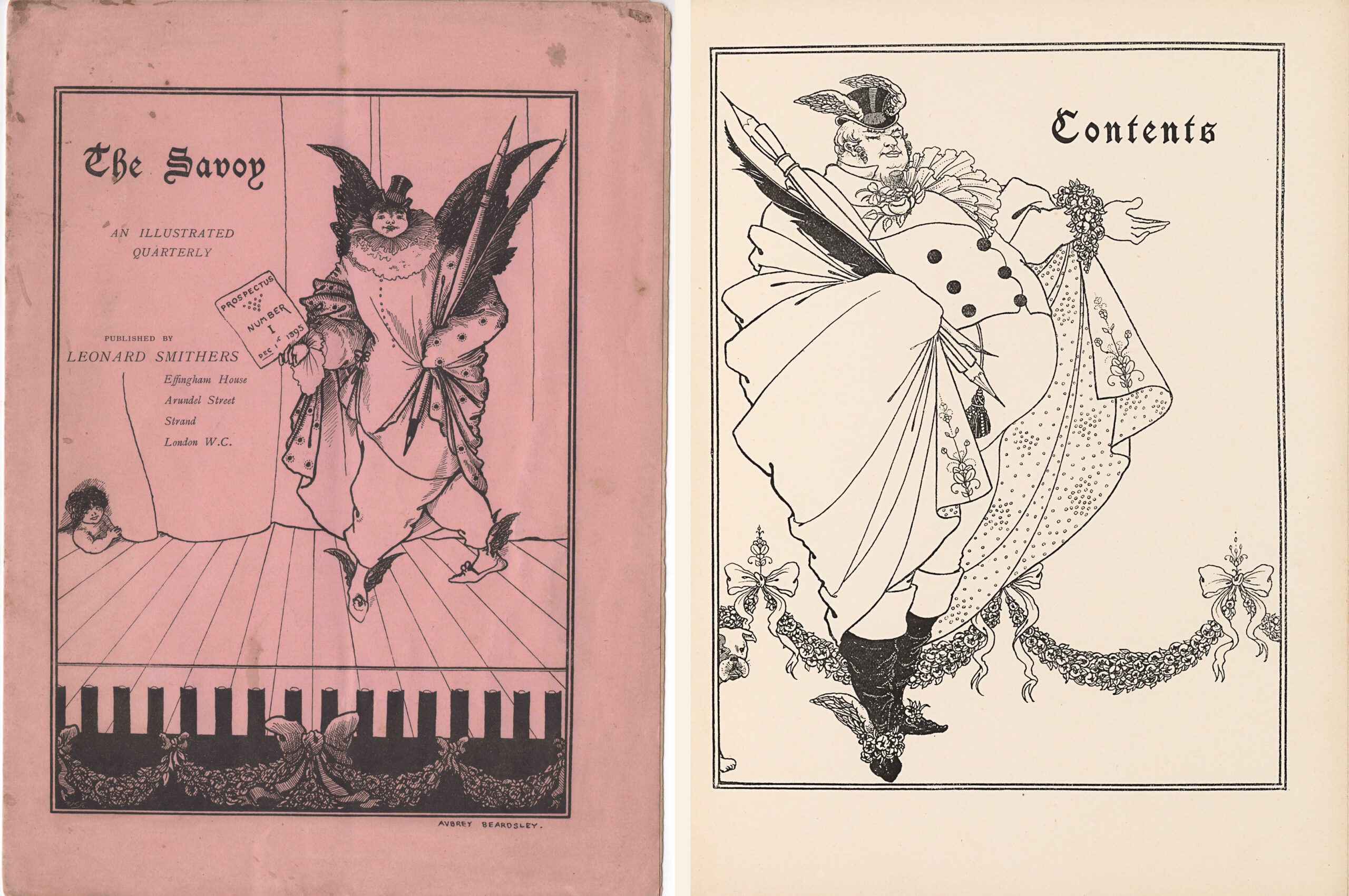

In November 1895, Smithers distributed a prospectus for the new venture. Designed by Beardsley, the image shows John Bull, the archetypal Englishman, strutting on stage with an oversized pencil and quill pen slung over his shoulder, the former referring to the magazine’s letterpress and the latter to its art. The text announces that “A New Quarterly Magazine, entitled The Savoy . . . will be published early in December next, by Mr. Leonard Smithers, of Effingham House, Arundel Street, Strand. Each number will contain upwards of 120 quarto pages of letterpress, and six or more illustrations, independent of the text, together with illustrated articles, and will cost 2S. 6d. net” (“Prospectus”). Symons, as editor, assured the magazine’s prospective readers, “We have no formulas and we desire no false unity of form or matter. We have not invented a new point of view. We are not Realists, or Romanticists, or Decadents. For us, all art is good which is good art” (“Prospectus”). This disavowal of any partisan loyalties—especially to the decadent movement with which both Symons and Beardsley had been previously associated—was likely an effort to insulate the new venture from the public outcry that had engulfed The Yellow Book, and there was some truth to the claim. While the magazine would include contributions by many avant-garde writers and artists of the period, including Max Beerbohm, Ernest Dowson, Lionel Johnson, Walter Sickert, and William Rothenstein (all of whom had earlier appeared in The Yellow Book), Symons and Beardsley were also careful to secure the contributions of more established figures, such as George Bernard Shaw, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and Joseph Pennell. The Savoy was to be a broad church.

Though the “Prospectus” sought to assure prospective readers and contributors that the new magazine would not court controversy, it was, ironically, also the cause of the first of the scandals that would plague The Savoy. Beardsley’s original design had, in fact, featured a different figure, a winged Pierrot carrying a card that read: “Prospectus, Number 1, December 1895.” Accounts vary as to why Smithers rejected this design, but Shaw, in an account recorded by Grant Richards, claims that the publisher was concerned that the clown might indicate a lack of seriousness; he suggested that John Bull, a popular symbol of traditional “Englishness,” might be more appropriate. Beardsley complied, and Smithers distributed some 80,000 copies of the revised “Prospectus” before George Moore, a respected novelist and an early supporter of the new magazine, noticed that the John Bull figure appeared to be in what Shaw calls “a condition of strained sexual excitement” (qtd. in Richards 19n1). Worried that Beardsley’s predilection for sexual innuendo would taint The Savoy much as it had The Yellow Book, Moore rallied a group of writers and artists—including Shaw— who had allowed their names to appear on the Prospectus, demanding that it be retracted. Smithers, who had no remaining copies to withdraw, readily agreed to the demand (Richards 19). While comical, the episode also speaks to the abiding sense of panic, most especially with regards to the depiction of male sexuality, that loomed uneasily over the venture. The Savoy would find itself repeatedly trying to appeal to the conservative sentiment of the British public (and, indeed, some of its own contributors), while seeking to remain true to the aesthetic credo that good art is indifferent to morality.

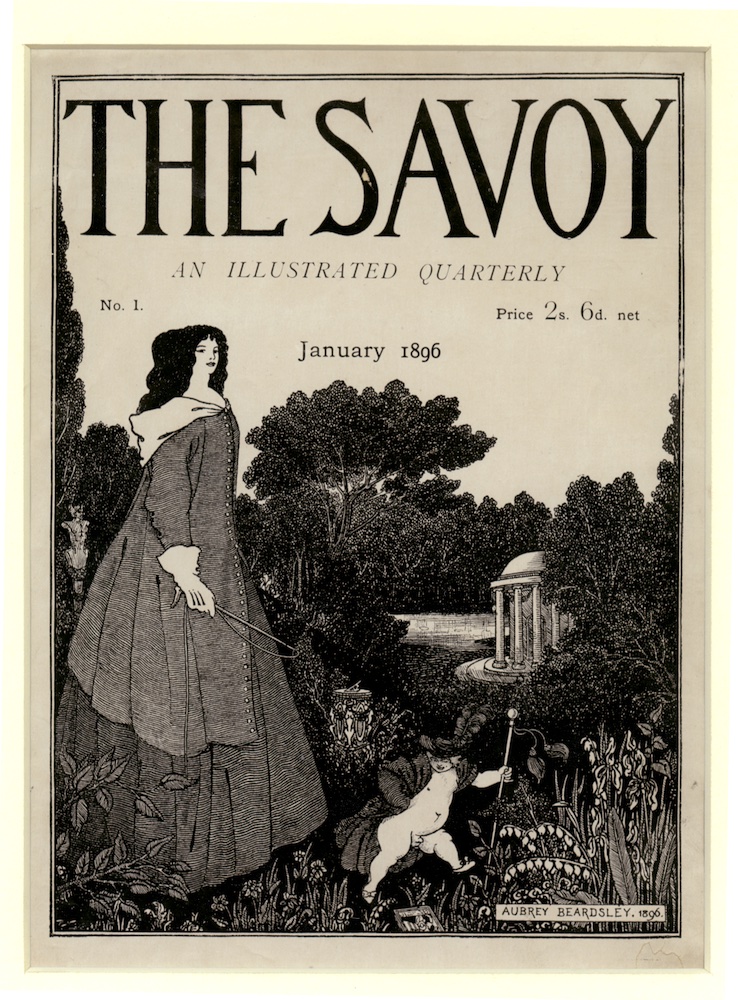

The Savoy’s debut, as the “Prospectus” indicates, was scheduled for December. Hoping to entice readers over the holidays, Smithers commissioned Beardsley to produce a large Christmas card to be included free with every copy. But problems with the artwork quickly mounted up. First there were the changes to the John Bull image, a version of which was to introduce the contents, and then there was the cover. Beardsley’s original design depicted an elegant woman in full riding habit, her hair loose and the front buttons of her tunic partially undone, chasing a naked cherub through the lush undergrowth of a neo-classical garden. The image was one of Beardsley’s finest achievements to date, but he seemingly could not pass up the opportunity to indicate how he felt his new venture compared with that of his former employer. Upon close inspection, the cherub, an alter ego for the artist himself, appeared to be urinating on a copy of The Yellow Book which lay half-obscured in the foliage (fig. 2). Smithers insisted that this image, too, needed to be altered, and the ensuing delays (occasioned in part by Beardsley’s poor health) meant that the publisher was unable to get the copy to the printers in time for the gift-buying season. Already priced just above cost, the magazine would also have to forgo the additional sales and publicity that a December launch might have brought.

The first issue of The Savoy finally appeared in January 1896, Beardsley’s Christmas card, featuring an ornate image of the Madonna and child, now serving as a belated New Year’s greeting (fig. 3). The first issue did not sell out its print run of 3000 copies, but sales were strong enough as to merit enthusiasm for the magazine’s future. In order to improve the print quality of the second number (and shed any lingering association with his career as a publisher of erotica), the publisher cut his ties with his former partner, the printer W.S. Nichols. All future numbers would be produced by the reputable Chiswick Press (Nelson 369 n125) and Paul Naumann’s firm would take care of the reproduction of visual art.

Further changes came with The Savoy’s third number. The magazine changed from a quarterly publication schedule to a monthly, dropped the board covers for paper, and lowered both the page count and retail price—each copy would now cost 2 shillings even. These efforts to resituate The Savoy more squarely within the mainstream of periodical publishing—to make it, in effect, more of a magazine and less of a book— were to be in vain. On receipt of the July issue, the first of the monthly numbers, W.H. Smith, the prominent bookseller with stalls in scores of railway stations across the nation, notified Smithers that they would not be carrying the title. Perhaps surprisingly, given his well-earned reputation for boundary pushing, it was not Beardsley’s artwork to which the bookseller objected, but that of Blake. “Antaeus Setting Virgil and Dante Upon the Verge of Cocytus” was one of three rare or previously unpublished designs that accompanied an essay by Yeats that cast the Romantic poet as a forerunner of Symbolism. The bookseller’s manager, Yeats recalled in his Autobiographies, objected to Blake’s depiction of male nudity. Symons, fully realizing what it would mean to lose access to the vast number of readers who purchased magazines to accompany their travel, pleaded with the manager to reconsider. Blake, he remonstrated, was, in fact, “a very spiritual artist.” The manger replied, “O, Mr. Symons, you must remember that we have an audience of young ladies as well as an audience of agnostics” (249). The fact that the manager added that “[i]f contrary to our expectations the Savoy should have a large sale, we should be very glad to see you again,” suggests that W.H. Smith’s decision to drop the magazine was likely more motivated by the desire to protect its reputation than by its desire to protect the supposedly delicate sensibilities of female readers (249). Whether it was Blake or Beardsley, carrying The Savoy was simply more of a risk than its modest sales merited.

The loss of W.H. Smith as a distributor was a significant blow for The Savoy. Each of the following monthly numbers saw declining sales and while Smithers and Symons tried to keep the magazine afloat by trimming the number of pages, sales continued to slump. By November, the writing was on the wall. In his editorial note for the seventh number, Symons announced that The Savoy would cease publication the following month. The magazine, he writes, had largely conquered a reluctant press, but “it has not conquered the general public, and, without the florins of the general public, no magazine such as ‘The Savoy,’ issued at so low a price, and without the aid of advertisements, can expect to pay its way. We therefore retire from the arena, not entirely dissatisfied, if not a trifle disappointed” (5). With little in the way of funds to commission new work, the magazine’s last issue, number eight, was composed entirely of essays, poems, short stories, and illustrations by Symons and Beardsley.

The demise of The Savoy was regretted by many and there were at least two plans to revive it. Hubert Crackanthorpe, believing the magazine had failed largely owing to its association with Beardsley, briefly explored the possibility of purchasing the magazine’s name and continuing it under his own editorship, but soon abandoned the idea (Richards 17-18). Smithers’s own plans to mount a successor, one that in Symons’s words, “will be in a more luxurious form, for which you shall pay more, but less often” (“Editorial Note” 5), similarly came to nothing. The publisher set about, instead, collecting the unsold copies from various shops and distributors to be bound as a three-volume set, with a new cover design by Beardsley, priced at one guinea.

Though it ran for only eight issues, The Savoy is recognized today as “one of the most significant and most beautifully produced ‘little magazines’ of the period” (“Aubrey Beardsley”). It is remembered, in particular, as an outlet for the prodigious talents of Beardsley, one of the most important English artists of the nineteenth century. Beardsley served as the magazine’s de facto art editor (though he was never named as such on its masthead), and made major contributions to both its art and letterpress. It was in the pages of The Savoy that he unveiled the artistic style that would characterize his late work, one that abandoned the swooping lines and Japanese influences of his designs for The Yellow Book in favour of a more rococo (and labour-intensive) aesthetic derived from eighteenth-century French book illustrations. And it was also in The Savoy that Beardsley published his major work of self-illustrated prose fiction, a lavish reworking of the Venus and Tannhäuser legend, entitled Under the Hill. As Stanley Weintraub notes, “If there was one thing about which readers and critics agreed, it was the excellence and drawing power of Beardsley’s contributions and the popular interest in Beardsley as a personality” (xlii).

Recent scholarship regarding The Savoy, however, has tended to turn away from the focus on Beardsley’s role in order to better attend to the magazine’s place within the social and professional networks of fin-de-siècle little magazines. Laurel Brake, for example, acknowledges that Beardsley’s inability, owing to his poor health, to maintain the pace of his early contributions to the magazine was an important factor in The Savoy’s failure to attract a large readership. “But considering the richness of the literary content,” she writes, “its criticism, poetry, and fiction by a variety of contributors— it is misleading to promulgate Hesketh Pearson’s view that it might be dubbed ‘The Beardsley’” (83-4). The Savoy, indeed, encompassed a wide range of literary genres and artistic movements. In addition to the first two instalments of Beardsley’s decadent novel Under the Hill, and Yeats’s poetry and short stories celebrating the Celtic Revival, The Savoy published works of naturalistic fiction, including Joseph Conrad’s first short story, and lyric poetry by Mathilde Blind, Ernest Dowson, John Gray,and Lionel Johnson. Moreover, essays and reviews in The Savoy helped revive critical interest in Blake and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, vigorously defended Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, and introduced English-speaking readers to the poetry of the French symbolists, including Paul Verlaine and Stéphane Mallarmé, and the radical philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. While women writers and artists feature much less frequently in its pages than in other magazines of the other period (there are only seven in the entire run, eight if one includes Fiona MacLeod, the alter ego of William Sharp), they are responsible for some of The Savoy’s most noteworthy contributions, including a remarkable reworking of the dopplegänger myth by Olivia Shakespear, and the first published work of the young Indian poet (and future political activist) Sarojini Naidu. These literary texts were accompanied by first-rate visual art, some of which served as illustrations to the literature, but the majority of which were stand-alone works. The latter included, apart from those of Beardsley, Blake, and Rossetti noted above, contributions from Charles Conder, Mabel Dearmer, Joseph Pennell, Charles Shannon, and the artist that Smithers groomed as Beardsley’s successor, William T. Horton.

The Savoy’s claim to being worthy of the attention of modern scholars and readers is not, however, limited to the literary and artistic works it published. It was also a remarkable experiment in publishing. In a period in which the magazine industry was flourishing, with publishers seeking to appeal to both the general reader with a limited budget and those with more specialized tastes and the income to support them, The Savoy sought to find the middle ground, the place where art and commerce might meet. Initially, it sought this middle ground by adopting the book format and quarterly publication schedule of its chief rival, The Yellow Book, but priced more cheaply. Then, sensing that he needed to move the magazine more squarely into the mainstream to achieve the sales necessary sustain its low cover price, Smithers retooled The Savoy as a more modern, market-friendly monthly. With their quarto-sized paper covers in pale green, streamlined contents, and a retail price of just 2s, The Savoy’s last six numbers resembled, in many respects, the popular magazines that crowded the shelves of the nation’s bookstalls. Whether as a quarterly or monthly, however, The Savoy offered readers the kind of avant-garde poetry, fiction, and prose non-fiction typically associated with smaller, more exclusively literary journals, and quality artwork reproduced with the care and precision of the best art magazines. The Savoy thus allowed readers to indulge in the most Epicurean of literary and artistic fare without needing an invitation to a fashionable salon or membership in a group like the Rhymers’ Club. Even so, the magazine was unable, in Symons’s words, to reach those “people in the world who really cared for art, and really for art’s sake” (“A Literary Causerie” 92). The experiment, bold as it was, failed, but the failure itself tells us much about the shifting cultural mood of the period immediately following Wilde’s arrest. The Savoy thus remains a testament to both the difficulties and the excitement of publishing forward-looking art, literature, and criticism in the declining days of the “yellow nineties.”

©2022 Christopher Keep, Associate Professor of English, Western University

Works Cited

- “Aubrey Beardsley: Exhibition Guide.” Tate Britain. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/aubrey-beardsley/exhibition-guide

- Beardsley, Aubrey. “A Large Christmas Card.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, insert. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2019. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/savoyv1_beardsley_christmas/

- Blake, William. “Antaeus Setting Virgil and Dante Upon the Verge of Cocytus.” Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2018-2019. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/savoyv3_blake_antaeus/

- Brake, Laurel. “Aestheticism and Decadence: The Yellow Book (1894-7), The Chameleon (1894), and The Savoy (1896).” The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, edited by Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker, vol. 1, Oxford UP, 2009, pp. 76-100.

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen and Dennis Denisoff. “The Yellow Book: Introduction to Volume 5 (April 1895).” Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2011. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/YB_V5_introduction

- Nelson, James G. Publisher to the Decadents: Leonard Smithers in the Careers of Beardsley, Wilde, Dowson. Pennsylvania State UP, 2000.

- Pearson, Hesketh. Oscar Wilde: His Life and Wit. Grosset and Dunlap, 1946.

- Richards, Grant. Author Hunting, By an Old Literary Sports Man: Memories of Years Spent Mainly in Publishing, 1897-1925. Coward-McCann, 1925.

- Sturgis, Matthew. Aubrey Beardsley: A Biography. Flamingo, 1999.

- Symons, Arthur. “Dieppe: 1895.” The Savoy, vol. 1 January 1896, pp. 84-102. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-symons-dieppe/

- —. “Editorial Note.” The Savoy, no. 7, Nov., 1896, p. 5. Yellow Nineties 2.0. https://beta.1890s.ca/savoyv7-editorial-note/

- —. “A Literary Causerie: By Way of an Epilogue.” The Savoy, no. 8, Dec., 1896, pp. 91-92. Yellow Nineties 2.0. https://beta.1890s.ca/savoyv8-symons-causerie/

- —. The Memoirs of Arthur Symons: Life and Art in the 1890s. Edited by Karl Beckson. Pennsylvania State UP, 1977.

- —. Prospectus for The Savoy. Yellow Nineties 2.0. https://beta.1890s.ca/savoy-prospectus/

- “Table of Contents.” The Savoy, vol. 1 January 1896, pp. 9-11. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-toc/

- Yeats, W.B. Autobiographies. Edited by William H.O. Donnell and Douglas N. Archibald, 1999. Collected Works of W.B. Yeats, general editors, Richard J. Finneran and George Mills Harper, vol. 3, Scribners, 1988-2003.

MLA citation:

Keep, Christopher. “General Introduction to The Savoy (1896)” Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/savoy-general-introduction/