The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume VIII January 1896

Contents

Literature

I. The Foolish Virgin . . By George Gissing. Page 11

II. Rest …. Arthur Christopher

Benson 43

III. Two Stories …Frances E. Huntley . . 47

IV. P’tit-Bleu … Henry

Harland .. 65

V. Aubade …. Rosamund Marriott Watson 97

VI. Dies Irae … Kenneth

Grahame ..101

VII. The Enchanted

Stone . Lewis Hind … 115

VIII. Two Songs … Nora Hopper

… 137

IX. A Captain of Salvation . John Buchan… 143

X. Georg

Brandes .. Julie Norregard .. 163

XI.

Postscript … Ernest

Wentworth…177

XII. In Dull Brown

..Evelyn Sharp … 180

XIII. Three Prose Fancies . Richard

Le Gallienne . 205

XIV. Rain (from

the French)

of Emile Verhaeren) Alma Strettell…

223

XV. A Slip under the Micro- scope H.G. Wells… 229

XVI. The Deacon … Mary Howarth .. 255

XVII. Two Sonnets . Hon. Maurice Baring . 297

XVIII. A

Resurrection ..H.B. Marriott Watson .

303

XIX. The Quest of Sorrow . Mrs. Ernest Leverson .. 325

XX. A Mood … Olive Custance .. 341

XXI.

Poet and Historian .. Walter Raleigh .. 349

XXII. Wait

…. Frances Nicholson .. 371

XXIII. An Engagement .. Ella

D’Arcy.. 379

Art

The Yellow Book — Vol. VIII. — January, 1896

Art

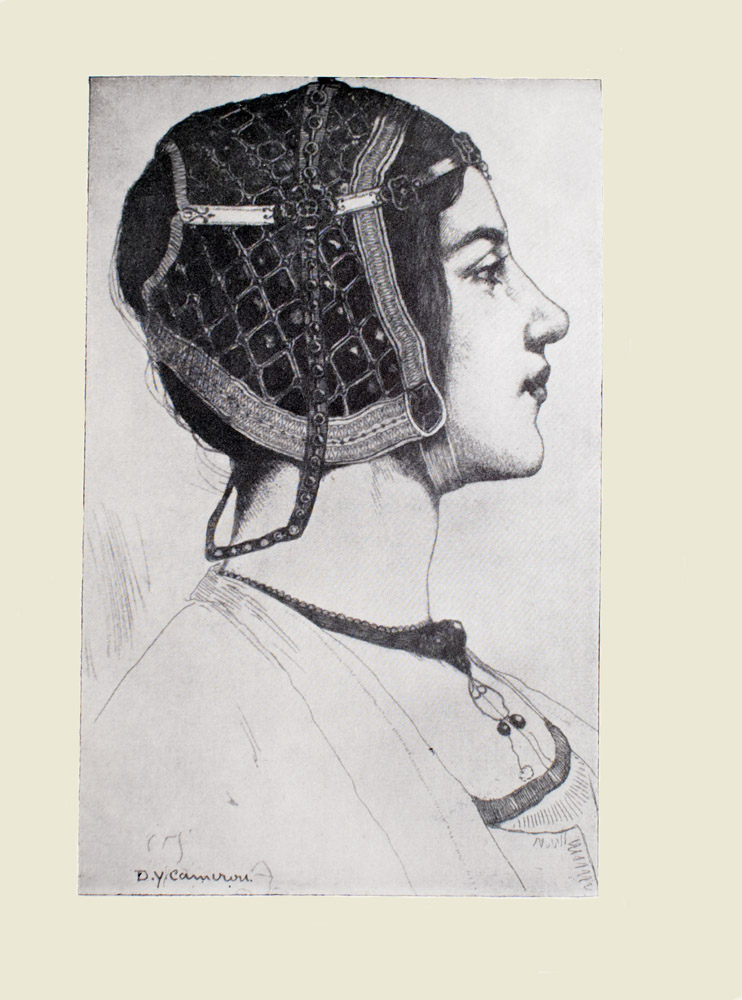

I. A Girl’s Head. . By D.Y.

Cameron Page 9

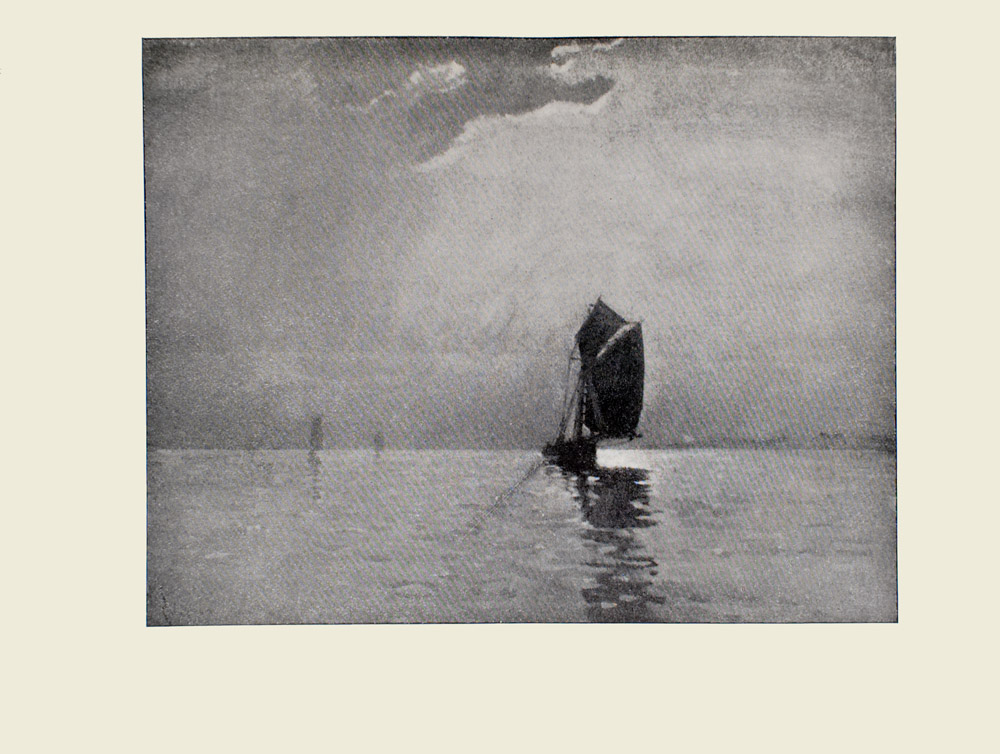

II. A Southerly

Air ..A. Frew .. 39

III. Study of a Calf .. D.Gauld

.. 44

IV. A Pastoral…

Whitelaw Hamilton. 61

V. Stacking

Hay … William Kennedy . 94

VI. A Girl’s Head. . Harrington

Mann . 98

VII. The Harbour Light..

D. Martin .. 112

VIII. Evening by the River . T.C. Morton ..

133

IX. Under the Moon .. F.H. Newbery . 139

X. A Windmill

… James Paterson .. 159

XI. Hen and Chickens .. George

Pirie .. 173

XII. The Old Mill ..

R.M. Stevenson . 178

XIII. The Forge … Grosvenor

Thomas . 201

XIV. Geisha …. E. Hornel .. 220

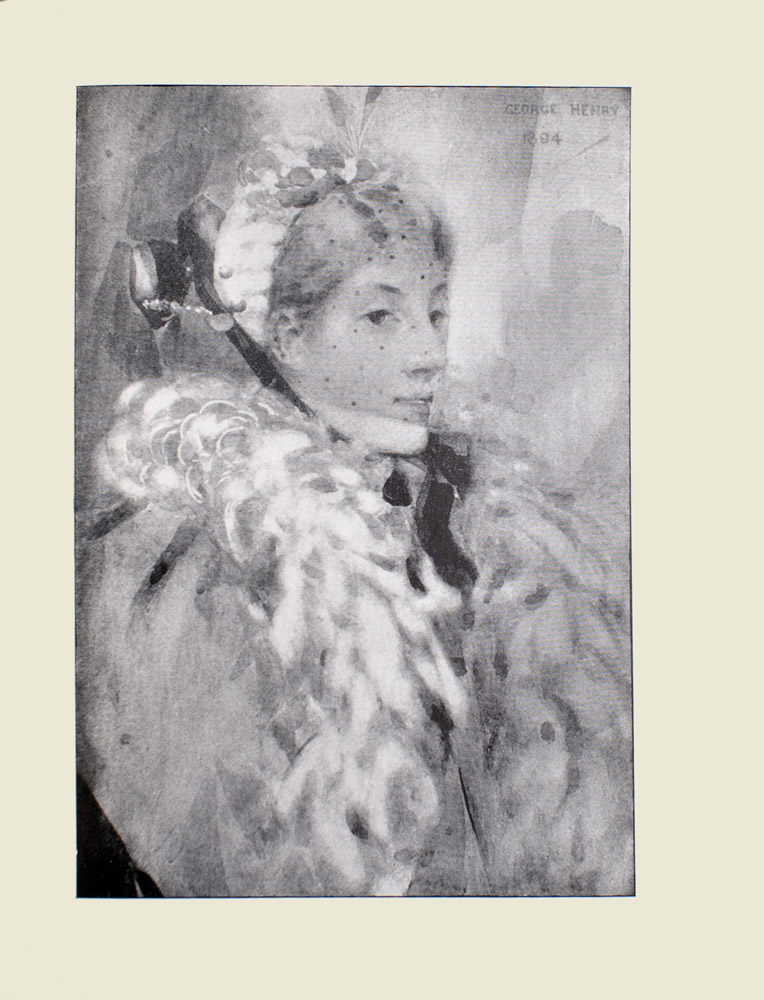

XV. Portrait of a Lady .. George Henry ..

226

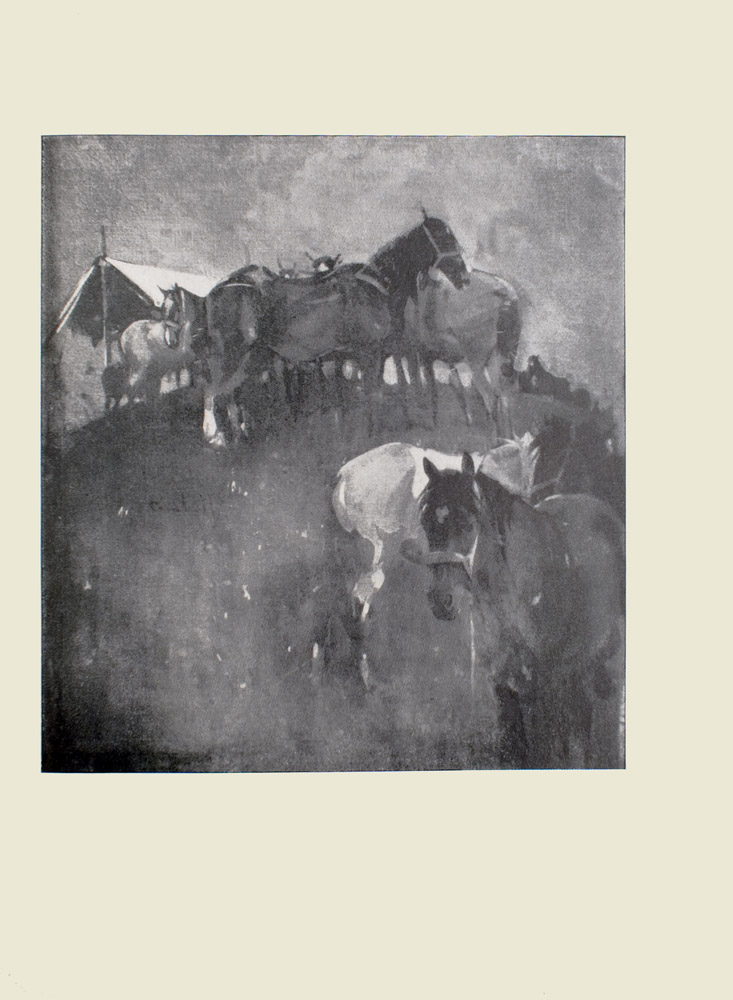

XVI. Horses …. J.

Crawhall .. 252

XVII. The Ballad

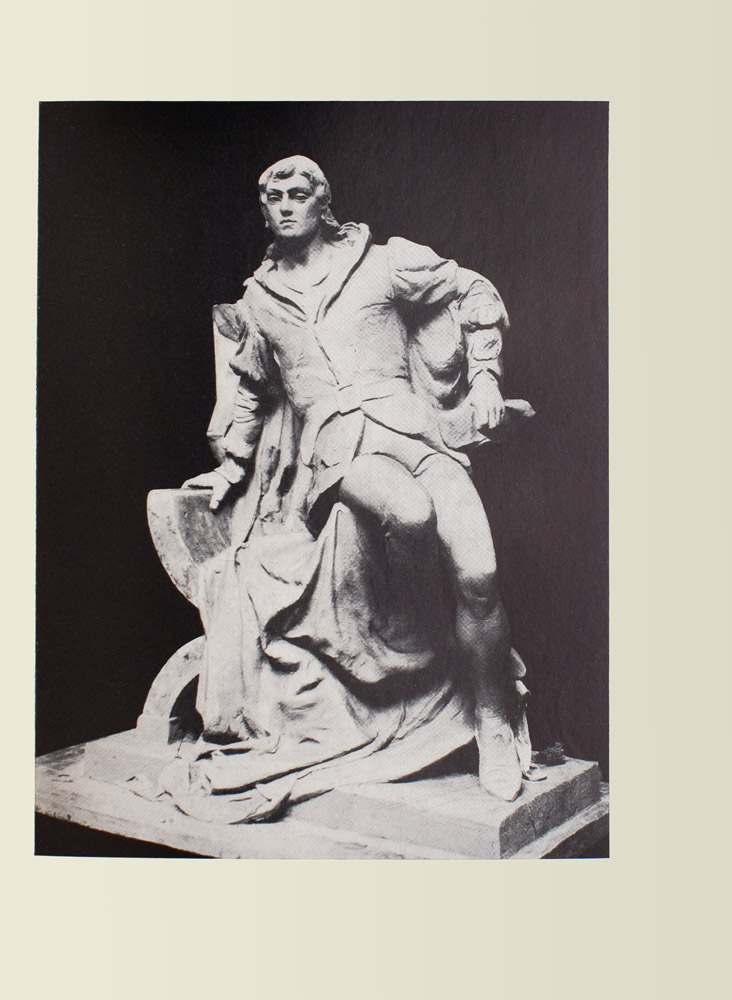

Monger . Kellock Brown . 293

XVIII.

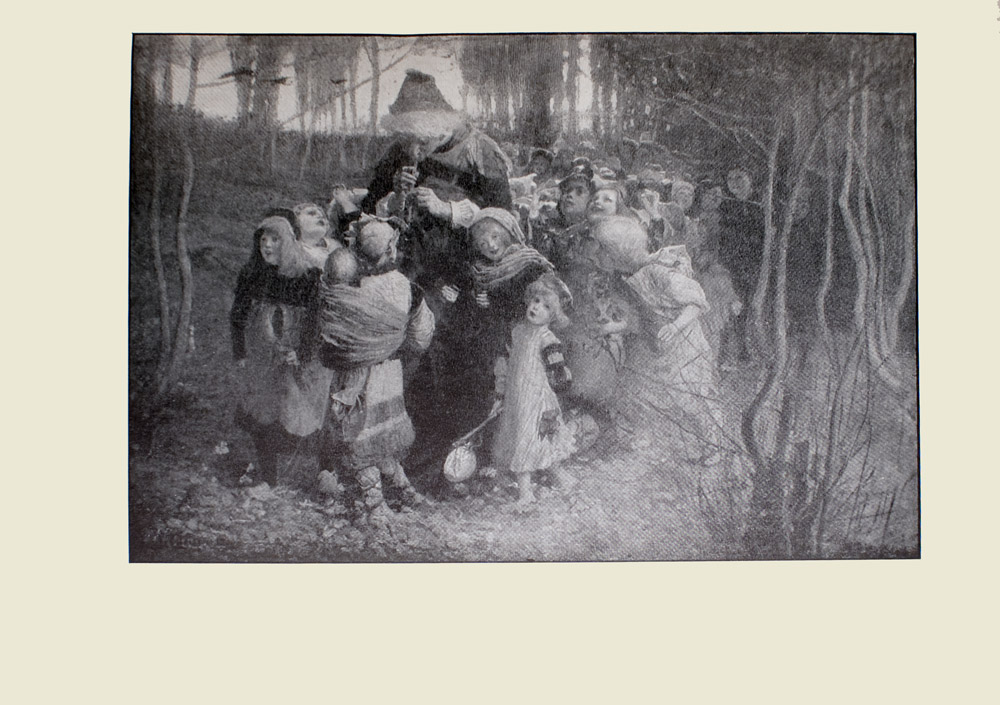

The Pied Piper .. J.E.

Christie .. 299

XIX. Wild Roses …

Stuart Park .. 321

XX. Portrait of Kenneth Grahame

XXI. Portrait of a Child E.A. Walton .. 336

XXII. A Sketch … James Guthrie .. 43

XXIII.

A Barb

..

XXIV. Portrait of Miss Burrell John Lavery .. 366

XXV. Idling . . .

XXVI. The Window

Seat Alexander Roche . 373

Back Cover, by Patten Wilson

The Cover Design and Title-page are by D. Y. Cameron.

The Pictures are by Members of the Glasgow School.

the Half-tone Blocks

are by the Swan Electric Engraving Company

The Editor of THE YELLOW BOOK can in no case

hold himself responsible for rejected manuscripts ;

when, however, they are accompanied by stamped

addressed envelopes, every effort will be made to

secure their prompt return. Manuscripts arriving un-

accompanied by stamped addressed envelopes will be neither

read nor returned.

The Foolish Virgin

By George Gissing

COMING down to breakfast, as usual, rather late, Miss Jewell

was surprised

to find several persons still at table. Their

conversation ceased as she

entered, and all eyes were directed to

her with a look in which she

discerned some special meaning.

For several reasons she was in an irritable

humour ; the significant

smiles, the subdued ” Good mornings,” and the

silence that fol-

lowed, so jarred upon her nerves that, save for

curiosity, she would

have turned and left the room.

Mrs. Banting (generally at this hour busy in other parts of the

house)

inquired with a sympathetic air whether she would take

porridge ; the

others awaited her reply as if it were a matter of

general interest. Miss

Jewell abruptly demanded an egg. The

awkward pause was broken by a high

falsetto.

” I believe you know who it is all the time, Mr. Drake,” said

Miss Ayres,

addressing the one man present.

” I assure you I don’t. Upon my word, I don’t. The whole

thing astonishes

me.”

Resolutely silent, Miss Jewell listened to a conversation the

drift of which

remained dark to her, until some one spoke the name

” Mr. Cheeseman ; ”

then it was with difficulty that she controlled

her face and her tongue.

The servant brought her an egg. She

struck

struck it clumsily with the edge of the spoon, and asked in an

affected

drawl :

” What are you people talking about ? “

Mrs. Sleath, smiling maliciously, took it upon herself to

reply.

” Mr. Drake has had a letter from Mr. Cheeseman. He writes

that he’s

engaged, but doesn’t say who to. Delicious mystery,

isn’t it ? ”

The listener tried to swallow a piece of bread-and-butter, and

seemed to

struggle with a constriction of the throat. Then, look-

ing round the

table, she said with contemptuous pleasantry :

” Some lodging-house servant, I shouldn’t wonder.”

Every one laughed. Then Mr. Drake declared he must be off

and rose from the

table. The ladies also moved, and in a minute

or two Miss Jewell sat at her

breakfast alone.

She was a tall, slim person, with unremarkable, not ill-moulded

features.

Nature meant her to be graceful in form and pleasantly

feminine of

countenance ; unwholesome habit of mind and body

was responsible for the

defects that now appeared in her. She had

no colour, no flesh ; but an

agreeable smile would well have

become her lips, and her eyes needed only

the illumination of

healthy thought to be more than commonly attractive. A

few

months would see the close of her twenty-ninth year ; but Mrs.

Banting’s boarders, with some excuse, judged her on the wrong

side of

thirty.

Her meal, a sad pretence, was soon finished. She went to the

window and

stood there for five minutes looking at the cabs and

pedestrians in the

sunny street. Then, with the languid step

which had become natural to her,

she ascended the stairs and

turned into the drawing-room. Here, as she had

expected, two

ladies sat in close conversation. Without heeding them,

she

walked

walked to the piano, selected a sheet of music, and sat down to

play.

Presently, whilst she drummed with vigour on the keys, some

one approached ;

she looked up and saw Mrs. Banting ; the other

persons had left the room.

” If it’s true,” murmured Mrs. Banting, with genuine kindli-

ness on her

flabby lips, ” all I can say is that it’s shameful—shame-

ful ! ”

Miss Jewell stared at her.

” What do you mean ? ”

” Mr. Cheeseman—to go and——”

” I don’t understand you. What is it to me ? “

The words were thrown out almost fiercely, and a crash on the

piano drowned

whatever Mrs. Banting meant to utter in reply.

Miss Jewell now had the

drawing-room to herself.

She ” practised ” for half an hour, careering through many fami-

liar pieces

with frequent mechanical correction of time-honoured

blunders. When at

length she was going up to her room, a

grinning servant handed her a letter

which had just arrived.

A glance at the envelope told her from whom it

came, and

in privacy she at once opened it. The writer’s address was

Glasgow.

” My dear Rosamund,” began the letter, ” I can’t understand

why you write in

such a nasty way. For some time now your

letters have been horrid. I don’t

show them to William because

if I did he would get into a tantrum. What I

have to say to you

now is this, that we simply can’t go on sending you the

money.

We haven’t it to spare, and that s the plain truth. You think

we’re rolling in money, and it s no use telling you we are not.

William

said last night that you must find some way of

supporting

yourself, and I can only say the same. You are a lady and had a

thorough

thorough good education, and I am sure you have only to exert

yourself.

William says I may promise you a five-pound note

twice a year, but more

than that you must not expect. Now do

just think over your

position—”

She threw the sheet of paper aside, and sat down to brood miser-

ably. This

little back bedroom, at no time conducive to good

spirits, had seen

Rosamund in many a dreary or exasperated mood ;

to-day it beheld her on the

very verge of despair. Illuminated

texts of Scripture spoke to her from the

walls in vain ; portraits

of admired clergymen smiled vainly from the

mantelpiece. She

was conscious only of a dirty carpet, an ill-made bed,

faded

curtains, and a window that looked out on nothing. One cannot

expect much for a guinea a week, when it includes board and

lodging ; the

bedroom was at least a refuge, but even that, it

seemed, would henceforth

be denied her. Oh, the selfishness of

people ! And oh, the perfidy of man

!

For eight years, since the breaking up of her home, Rosamund

had lived in

London boarding-houses. To begin with, she could

count on a sufficient

income, resulting from property in which

she had a legitimate share. Owing

to various causes, the value of

this property had steadily diminished,

until at length she became

dependent upon the subsidies of kinsfolk ; for

more than a twelve-

month now, the only person able and willing to continue

such

remittances had been her married sister, and Rosamund had hardly

known what it was to have a shilling of pocket-money. From

time to time she

thought feebly and confusedly of ” doing some-

thing,” but her aims were so

vague, her capabilities so inadequate,

that she always threw aside the

intention in sheer hopelessness.

Whatever will she might once have

possessed had evaporated in

the boarding-house atmosphere. It was hard to

believe that her

brother-in-law would ever withhold the poor five pounds a

month.

and

And—what is the use of boarding-houses if not to renew indefi-

nitely

the hope of marriage ?

She was not of the base order of women. Conscience yet lived

in her, and

drew support from religion ; something of modesty,

of self-respect, still

clad her starving soul. Ignorance and ill-luck

had once or twice thrown her

into such society as may be found

in establishments outwardly respectable ;

she trembled and fled.

Even in such a house as this of Mrs. Banting’s, she

had known

sickness of disgust. Herself included, four single women

abode

here at the present time ; and the scarcely disguised purpose of

every one of them was to entrap a marriageable man. In the

others, it

seemed to her detestable, and she hated all three, even as

they in their

turn detested her. Rosamund flattered herself with

the persuasion that she

did not aim merely at marriage and a sub-

sistence ; she would not

marryany one ; her desire was for sym-

pathy, true companionship. In years gone by she had used to

herself a more

sacred word ; nowadays the homely solace seemed

enough. And of late a ray

of hope had glimmered upon her dusty

path. Mr. Cheeseman, with his

plausible airs, his engaging smile,

had won something more than her

confidence ; an acquaintance

of six months, ripening at length to intimacy,

justified her in

regarding him with sanguine emotion. They had walked

toge-

ther in Kensington Gardens ; they had exchanged furtive and

significant glances at table and elsewhere ; every one grew aware

of the

mutual preference. It shook her with a painful misgiving

when Mr. Cheeseman

went away for his holiday and spoke no

word ; but probably he would write.

He had written—to his

friend Drake ; and all was over.

Her affections suffered, but that was not the worst. Her pride

had never

received so cruel a blow.

After a life of degradation which might well have unsexed her,

Rosamund

Rosamund remained a woman. The practice of affectations

numberless had

taught her one truth, that she could never hope

to charm save by reliance

upon her feminine qualities. Boarding-

house girls, such numbers of whom

she had observed, seemed all

intent upon disowning their womanhood ; they

cultivated mascu-

line habits, wore as far as possible male attire, talked

loud slang,

threw scorn (among themselves at all events) upon domestic

virtues ; and not a few of them seemed to profit by the prevailing

fashion.

Rosamund had tried these tactics, always with conscious

failure. At other

times, and vastly to her relief, she aimed in

precisely the opposite

direction, encouraging herself in feminine

extremes. She would talk with

babbling naïveté, exaggerate the

languor induced

by idleness, lack of exercise, and consequent

ill-health ; betray

timidities and pruderies, let fall a pious phrase,

rise of a morning for ”

early celebration ” and let the fact be

known. These and the like

extravagances had appeared to fasci-

nate Mr. Cheeseman, who openly

professed his dislike for andro-

gynous persons. And Rosamund enjoyed the

satisfaction of

moderate sincerity. Thus, or very much in this way, would

she

be content to live. Romantic passion she felt to be beyond her

scope. Long ago—ah ! perhaps long ago, when she first knew

Geoffrey

Hunt—

The name, as it crossed her mind, suggested an escape from

the insufferable

ennui and humiliation of hours till evening.

It

must be half a year since she called upon the Hunts, her only

estim-

able acquaintances in or near London. They lived at Tedding-

ton, and the railway fare was always a deterrent ; nor did she care

much

for Mrs. Hunt and her daughters, who of late years had

grown reserved with

her, as if uneasy about her mode of life.

True, they were not at all

snobbish ; homely, though well-to-do

people ; but they had such strict

views, and could not understand

the

the existence of a woman less energetic than themselves. In her

present

straits, which could hardly be worse, their counsel might

prove of value ;

though she doubted her courage when it came to

making confessions.

She would do without luncheon (impossible to sit at table with

those ”

creatures “) and hope to make up for it at tea ; in truth

appetite was not

likely to trouble her. Then for dress. Wearily

she compared this garment

with that, knowing beforehand that

all were out of fashion and more or less

shabby. Oh, what did

it matter ! She had come to beggary, the result that

might have

been foreseen long ago. Her faded costume suited fitly

enough

with her fortunes—nay, with her face. For just then she

caught

a sight of herself in the glass, and shrank. A lump choked her

:

looking desperately, as if for help, for pity, through gathering

tears, she saw the Bible verse on the nearest wall : ” Come unto

me—” Her heart became that of a woful child ; she put her

hands

before her face, and prayed in the old, simple words of

childhood.

As her call must not be made before half-past three, she could

not set out

upon the journey forthwith ; but it was a relief to get

away from the

house. In this bright weather, Kensington

Gardens, not far away, seemed a

natural place for loitering, but

the alleys would remind her too vividly of

late companionship ;

she walked in another direction, sauntered for an hour

by the

shop windows of Westbourne Grove, and, when she felt tired, sat

at the railway station until it was time to start. At Teddington,

half a

mile’s walk lay before her ; though she felt no hunger, long

abstinence and

the sun’s heat taxed her strength to the point of

exhaustion ; on reaching

her friend’s door, she stood trembling

with nervousness and fatigue. The

door opened, and to her

dismay she learnt that Mrs. Hunt was away from

home.

Happily

Happily, the servant added that Miss Caroline was in the

garden.

” I’ll go round,” said Rosamund at once. ” Don’t trouble—”

The

pathway round the pleasant little house soon brought her

within view of a

young lady who sat in a garden-chair, sewing.

But Miss Caroline was not

alone ; near to her stood a man in

shirt-sleeves and bare-headed,

vigorously sawing a plank ; he seemed

to be engaged in the construction of

a summer-house, and Rosa-

mund took him at first sight for a mechanic, but

when he turned

round, exhibiting a ruddy face all agleam with health and

good

humour, she recognised the young lady’s brother, Geoffrey Hunt.

He, as though for the moment puzzled, looked fixedly at her.

” Oh, Miss Jewell, how glad I am to see you ! ”

Enlightened by his sister’s words, Geoffrey dropped the saw,

and stepped

forward with still heartier greeting. Had civility

permitted, he might

easily have explained his doubts. It was

some six years since his last

meeting with Rosamund, and she

had changed not a little ; he remembered her

as a graceful and

rather pretty girl, with life in her, even if it ran for

the most part

to silliness, gaily dressed, sprightly of manner ;

notwithstanding

the account he had received of her from his relatives, it

astonished

him to look upon this limp, faded woman. In Rosamund’s

eyes,

Geoffrey was his old sell ; perhaps a trifle more stalwart, and

if

anything handsomer, but with just the same light in his eyes,

the

same smile on his bearded face, the same cordiality of

utterance. For an

instant, she compared him with Mr. Cheese-

man, and flushed for very shame.

Unable to command her voice,

she stammered incoherent nothings ; only when

a seat supported

her weary body did she lose the dizziness which had

threatened

downright collapse ; then she closed her eyes, and forgot

every-

thing but the sense of rest.

Geoffrey

Geoffrey drew on his coat, and spoke jestingly of his amateur

workmanship.

Such employment, however, seemed not inappro-

priate to him, for his

business was that of a timber-merchant.

Of late years he had lived abroad,

for the most part in Canada.

Rosamund learnt that at present he was having

a longish holiday.

” And you go back to Canada ? “

This she asked when Miss Hunt had stepped into the house to

call for tea.

Geoffrey answered that it was doubtful ; for various

reasons he rather

hoped to remain in England, but the choice

did not altogether rest with

him.

“At all events “—she gave a poor little laugh—”you haven’t

pined in exile.”

” Not a bit of it. I have always had plenty of hard work—

the one

thing needful.”

” Yes—I remember—you always used to say that. And I

used to

protest. You granted, I think, that it might be different

with women.”

” Did I ? “

He wished to add something to the point, but refrained out of

compassion. It

was clear to him that Miss Jewell, at all events,

would have been none the

worse for exacting employment.

Mrs. Hunt had spoken of her with the

disapprobation natural in

a healthy, active woman of the old school, and

Geoffrey himself

could not avoid a contemptuous judgment.

” You have lived in London all this time ? ” he asked, before

she could

speak.

” Yes. Where else should I live ? My sister at Glasgow

doesn’t want me

there, and—and there’s nobody else, you know.”

She tried to laugh. ”

I have friends in London—well, that is to

say—at all events

I’m not quite solitary.”

The man smiled, and could not allow her to suspect how pro-

The Yellow Book—Vol. VIII. B

foundly

foundly he pitied such a condition. Caroline Hunt had reappeared ;

she began

to talk of her mother and sister, who were enjoying

themselves in Wales.

Her own holiday would come upon their

return ; Geoffrey was going to take

her to Switzerland.

Tea arrived just as Rosamund was again sinking into bodily

faintness and

desolation of spirit. It presently restored her, but

she could hardly

converse. She kept hoping that Caroline would

offer her some

invitation—to lunch, to dine, anything ; but as

yet no such thought

seemed to occur to the young hostess.

Suddenly the aspect of things was

altered by the arrival of new

callers, a whole family, man, wife and three

children, strangers to

Rosamund. For a time it seemed as if she must go

away

without any kind of solace ; for Geoffrey had quitted her, and

she

sat alone. On the spur of irrational resentment, she rose and

advanced to Miss Hunt.

” Oh, but you are not going ! I want you to stay and have

dinner with us, if

you can. Would it make you too late ? ”

Rosamund flushed and could scarce contain her delight. In a

moment she was

playing with the youngest of the children, and

even laughing aloud, so that

Geoffrey glanced curiously towards

her. Even the opportunity of private

conversation which she had

not dared to count upon was granted before long

; when the

callers had departed Caroline excused herself, and left her

brother

alone with the guest for half an hour. There was no time to be

lost ; Rosamund broached almost immediately the subject upper-

most in her

mind.

” Mr. Hunt, I know how dreadful it is to have people asking

for advice, but

if I might—if you could have patience

with

me “—

” I haven’t much wisdom to spare,” he answered, with easy

good-nature.

” Oh,

” Oh, you are very rich in it, compared with poor me.—And

my position

is so difficult. I want—I am trying to find

some

way of being useful in the world. I am tired of living for

myself. I seem to be such a useless creature. Surely even I

must have some talent, which it s

my duty to put to use !

Where should I turn ? Could you help me with a

suggestion ? ”

Her words, now that she had overcome the difficulty of begin-

ning, chased

each other with breathless speed, and Geoffrey was

all but constrained to

seriousness ; he took it for granted, how-

ever, that Miss Jewell

frequently used this language ; doubtless

it was part of her foolish,

futile existence to talk of her soul’s

welfare, especially in tête-à-tête with unmarried men. The truth

he did

not suspect, and Rosamund could not bring herself to

convey it in plain

words.

” I do so envy the people who have something to live for ! “

Thus she

panted. ” I fear I haveneverhad a purpose in

life—

I m sure I don t know why. Of course I m only a woman,

but

even women nowadays are doing so much. You don’t despise

their

efforts, do you ? ”

” Not indiscriminately.”

” If I could feel myself a profitable member of society !—I

want to

be lifted above my wretched self. Is there no great end

to which I could

devote myself ?”

Her phrases grew only more magniloquent, and all the time

she was longing

for courage to say : ” How can I earn money ? “

Geoffrey, confirmed in the

suspicion that she talked only for

effect, indulged his natural humour.

” I’m such a groveller, Miss Jewell. I never knew these

aspirations. I see

the world mainly as cubic feet of timber.”

” No, no, you won’t make me believe that. I know you

have

ideals ! ”

” That

” That word reminds me of poor old Halliday. You remember

Halliday, don’t

you ? ”

In vexed silence, Rosamund shook her head.

” But I think you must have met him, in the old days. A

tall, fair

man—no ? He talked a great deal about ideals, and

meant to move the

world. We lost sight of each other when I

first left England, and only met

again a day or two ago. He is

married, and has three children, and looks

fifty years old, though

he can t be much more than thirty. He took me to

see his wife

—they live at Forest Hill.”

Rosamund was not listening, and the speaker became aware of

it. Having a

purpose in what he was about to say, he gently

claimed her attention.

” I think Mrs. Halliday is the kind of woman who would

interest you. If ever

any one had a purpose in life, she has.”

” Indeed ? And what ? ”

” To keep house admirably, and bring up her children as well

as possible, on

an income which would hardly supply some women

with shoe-leather.”

” Oh, that’s very dreadful ! ”

” Very fine, it seems to me. I never saw a woman for whom

I could feel more

respect. Halliday and she suit each other

perfectly ; they would be the

happiest people in England if they

had any money. As he walked back with me

to the station he

talked about their difficulties. They can’t afford to

engage a

good servant (if one exists nowadays), and cheap sluts have

driven

them frantic, so that Mrs. Halliday does everything with her

own

hands.”

” It must be awful.”

” Pretty hard, no doubt. She is an educated woman—otherwise,

of

course, she couldn’t, and wouldn’t, manage it. And, by-the-

bye

bye “—he paused for quiet emphasis—” she has a sister,

unmarried,

who lives in the country and does nothing at all. It occurs

to

one—doesn’t it ?—that the idle sister might pretty easily

find scope

for her energies.”

Rosamund stared at the ground. She was not so dull as to

lose the

significance of this story, and she imagined that Geoffrey

reflected upon

herself in relation to her own sister. She broke the

long silence by saying

awkwardly :

” I’m sure I would never allow a sister of mine to

lead such a

life.”

” I don’t think you would,” replied the other. And, though he

spoke

genially, Rosamund felt it a very moderate declaration of his

belief in

her. Overcome by strong feeling, she exclaimed :

” I would do anything to be of use in the world. You

don’t

think I mean it, but I do, Mr. Hunt. I—”

Her voice faltered ; the all-important word stuck in her throat.

And at that

moment Geoffrey rose.

” Shall we walk about ? Let me show you my mother’s fernery

she is very

proud of it.”

That was the end of intimate dialogue. Rosamund felt aggrieved,

and tried to

shape sarcasms, but the man’s imperturbable good-

humour soon made her

forget everything save the pleasure of

being in his company. It was a

bitter-sweet evening, yet perhaps

enjoyment predominated. Of course,

Geoffrey would conduct

her to the station ; she never lost sight of this

hope. There

would be another opportunity for plain speech. But her desire

was

frustrated ; at the time of departure, Caroline said that they

might

as well all go together. Rosamund could have wept for chagrin.

She returned to the detested house, the hateful little bedroom,

and there

let her tears have way. In dread lest the hysterical sobs

should be

overheard, she all but stifled herself.

Then,

Then, as if by blessed inspiration, a great thought took shape

in her

despairing mind. At the still hour of night she suddenly

sat up in the

darkness, which seemed illumined by a wondrous

hope. A few minutes

motionless ; the mental light grew dazzling ;

she sprang out of bed, partly

dressed herself, and by the rays of a

candle sat down to write a letter :

DEAR MR. HUNT,

“Yesterday I did not tell you the whole truth. I have

nothing to live upon,

and I must find employment or starve. My

brother-in-law has been supporting me for a long time—I am ashamed

to tell you, but I will, and he can do so no longer.

I wanted to ask

you for practical advice, but I did not make my meaning

clear. For

all that, you did advise me, and very

well indeed. I wish to offer

myself as domestic help to poor Mrs. Halliday.

Do you think she

would have me ? I ask no wages—only food and

lodging. I will

work harder and better than any general

servants—I will indeed. My

health is

not bad, and I am fairly strong. Don’t—don’t throw scorn

on this !

Will you recommend me to Mrs. Halliday—or ask Mrs.

Hunt to do so ? I

beg that you will. Please write to me at once,

and say yes. I shall be ever

grateful to you.

” Very sincerely yours,

” ROSAMUND JEWELL.”

This she posted as early as possible. The agonies she endured

in waiting for

a reply served to make her heedless of boarding-

house spite, and by the

last post that same evening came Geoffrey’s

letter. He wrote that her

suggestion was startling. ” Your

motive seems to me very praiseworthy, but

whether the thing

would be possible is another question. I dare not take

upon

myself the responsibility of counselling you to such a step.

Pray, take time, and think. I am most grieved to hear of your

difficulties,

but is there not some better way out of them ? ”

Yes,

Yes, there it was ! Geoffrey Hunt could not believe in her

power to do anything praiseworthy. So had it been six years

ago,

when she would have gone through flood and flame to win his

admiration. But in those days she was a girlish simpleton ; she

had behaved

idiotically. It should be different now ; were it at

the end of her life,

she would prove to him that he had slighted

her unjustly !

Brave words, but Rosamund attached some meaning to them.

The woman in

her—the ever-prevailing woman—was wrought by

fears and

vanities, urgencies and desires, to a strange point of

exaltation.

Forthwith, she wrote again : ” Send me, I entreat

you, Mrs. Halliday’s

address. I will go and see her. No, I can’t

do anything but work with my

hands. I am no good for anything

else. If Mrs. Halliday refuses me, I shall

go as a servant into

some other house. Don’t mock at me ; I don’t deserve

it. Write

at once.”

Till midnight she wept and prayed.

Geoffrey sent her the address, adding a few dry words : ” If

you are willing

and able to carry out this project, your ambition

ought to be satisfied.

You will have done your part towards solving

one of the gravest problems of

the time.” Rosamund did not at

once understand ; when the writer s meaning

grew clear, she kept

repeating the words, as though they were a new gospel.

Yes !

she would be working nobly, helping to show a way out of the

great servant difficulty. It would be an example to poor ladies,

like

herself, who were ashamed of honest work. And Geoffrey

Hunt was looking on.

He must needs marvel ; perhaps he would

admire greatly ; perhaps—oh,

oh !

Of course, she found a difficulty in wording her letter to the

lady who had

never heard of her, and of whom she knew practically

nothing. But zeal

surmounted obstacles. She began by saying

that

that she was in search of domestic employment, and that, through

her friends

at Teddington, she had heard of Mrs. Halliday as a

lady who might perhaps

consider her application. Then followed

an account of herself, tolerably

ingenuous, and an amplification of

the phrases she had addressed to

Geoffrey Hunt. On an after-

thought, she enclosed a stamped envelope.

Whilst the outcome remained dubious, Rosamund’s behaviour to

her

fellow-boarders was a pattern of offensiveness. She no longer

shunned

them—seemed, indeed, to challenge their observation for

the sake of

meeting it with arrogant defiance. She rudely in-

terrupted conversations,

met sneers with virulent retorts, made

herself the common enemy. Mrs.

Banting was appealed to ;

ladies declared that they could not live in a

house where they were

exposed to vulgar insult. When nearly a week had

passed Mrs.

Banting found it necessary to speak in private with Miss

Jewell,

and to make a plaintive remonstrance. Rosamund’s flashing eye

and contemptuous smile foretold the upshot.

” Spare yourself the trouble, Mrs. Banting. I leave the house

to-morrow.”

” Oh, but—”

” There is no need for another word. Of course, I shall pay

the week in

lieu of notice. I am busy, and have no time to

waste.”

The day before, she had been to Forest Hill, had seen Mrs.

Halliday, and

entered into an engagement. At midday on the

morrow she arrived at the

house which was henceforth to be her

home, the scene of her labours.

Sheer stress of circumstance accounted for Mrs. Halliday’s

decision.

Geoffrey Hunt, a dispassionate observer, was not misled

in forming so high

an opinion of his friend’s wife. Only a year

or two older than Rosamund,

Mrs. Halliday had the mind and the

temper

temper which enable woman to front life as a rational combatant,

instead of

vegetating as a more or less destructive parasite. Her

voice declared her

; it fell easily upon a soft, clear note ; the kind

of voice that

expresses good-humour and reasonableness, and many

other admirable

qualities ; womanly, but with no suggestion of

the feminine gamut ; a

voice that was never likely to test its

compass in extremes. She had

enjoyed a country breeding ; some-

thing of liberal education assisted her

natural intelligence ; thanks

to a good mother, she discharged with

ability and content the

prime domestic duties. But physically she was not

inexhaustible,

and the laborious, anxious years had taxed her health. A

woman

of the ignorant class may keep house, and bring up a family, with

her own hands ; she has to deal only with the simplest demands

of

life ; her home is a shelter, her food is primitive, her children

live or

die according to the law of natural selection. Infinitely

more complex,

more trying, is the task of the educated wife and

mother ; if to

conscientiousness be added enduring poverty, it

means not seldom an early

death. Fatigue and self-denial had set

upon Mrs. Halliday’s features a

stamp which could never be

obliterated. Her husband, her children,

suffered illnesses ; she,

the indispensable, durst not confess even to a

headache. Such

servants as from time to time she had engaged merely

increased

her toil and anxieties ; she demanded, to be sure, the diligence

and efficiency which in this new day can scarce be found among

the

menial ranks ; what she obtained was sluttish stupidity,

grotesque

presumption, and every form of female viciousness.

Rosamund Jewell, honest

in her extravagant fervour, seemed at

first a mocking apparition ; only

after a long talk, when Rosamund’s

ingenuousness had forcibly impressed

her, would Mrs. Halliday

agree to an experiment. Miss Jewell was to live

as one of the

family ; she did not ask this, but consented to it. She was

to

receive

receive ten pounds a year, for Mrs. Halliday insisted that payment

there

must be.

” I can’t cook,” Rosamund had avowed. ” I never boiled a

potato in my life.

If you teach me, I shall be grateful to you.”

” The cooking I can do myself, and you can learn if you like.”

” I should think I might wash and scrub by the light of

nature ? ”

“Perhaps. Good will and ordinary muscles will go a long

way.”

” I can’t sew, but I will learn.”

Mrs. Halliday reflected.

” You know that you are exchanging freedom for a hard and a

very dull life

? ”

“My life has been hard and dull enough, if you only knew.

The work will seem hard at first, no doubt. But I don’t think

I shall be

dull with you.”

Mrs. Halliday held out her work-worn hand, and received a

clasp of the

fingers attenuated by idleness.

It was a poor little house ; built—of course—with sham display

of spaciousness in front, and huddling discomfort at the rear.

Mrs.

Halliday’s servants never failed to urge the smallness of the

rooms as an

excuse for leaving them dirty ; they had invariably

been accustomed to

lordly abodes, where their virtues could expand.

The furniture was homely

and no more than sufficient, but here

and there on the walls shone a

glimpse of summer landscape, done

in better days by the master of the

house, who knew something of

various arts, but could not succeed in that

of money-making.

Rosamund bestowed her worldly goods in a tiny chamber

which

Mrs. Halliday did her best to make inviting and comfortable ;

she had less room here than at Mrs. Banting’s, but the cleanliness

of

surroundings would depend upon herself, and she was not likely

to

to spend much time by the bedside in weary discontent. Halliday,

who came

home each evening at half-past six, behaved to her on

their first meeting

with grave, even respectful, courtesy ; his tone

flattered Rosamund’s ear,

and nothing could have been more

seemly than the modest gentleness of her

replies.

At the close of the first day, she wrote to Geoffrey Hunt : ” I

do believe

I have made a good beginning. Mrs. Halliday is

perfect and I quite love

her. Please do not answer this ; I only

write because I feel that I owe it

to your kindness. I shall never

be able to thank you enough.”

When Geoffrey obeyed her and kept silence, she felt that he

acted prudently

; perhaps Mrs. Halliday might see the letter, and

know his hand. But none

the less she was disappointed.

Rosamund soon learnt the measure of her ignorance in domestic

affairs.

Thoroughly practical and systematic, her friend (this

was to be their

relation) set down a scheme of the day’s and

the week’s work ; it made a

clear apportionment between them,

with no preponderance of unpleasant

drudgery for the new-comer’s

share. With astonishment, which she did not

try to conceal,

Rosamund awoke to the complexity and endlessness of home

duties even in so small a house as this.

” Then you have no leisure ? ” she exclaimed, in

sympathy, not

remonstrance.

” I feel at leisure when I’m sewing—and when I take the

children

out. And there’s Sunday.”

The eldest child was about five years old, the others three and

a

twelvemonth, respectively. Their ailments gave a good deal of

trouble, and

it often happened that Mrs. Halliday was awake with

one of them the

greater part of the night. For children Rosa-

mund had no natural

tenderness ; to endure the constant sound

of their voices proved, in the

beginning, her hardest trial ; but

the

the resolve to school herself in every particular soon enabled her

to tend

the little ones with much patience, and insensibly she grew

fond of them.

Until she had overcome her awkwardness in every

task, it cost her no

little effort to get through the day ; at bedtim

e she ached in every joint,

and morning oppressed her with a sick

lassitude. Conscious however, of

Mrs. Halliday’s forbearance,

she would not spare herself, and it soon

surprised her to discover

that the rigid performance of what seemed an

ignoble task

brought its reward. Her first success in polishing a grate

gave her

more delight than she had known since childhood. She summoned

her friend to look, to admire, to praise.

” Haven’t I done it well ? Could you do it better yourself ?

” Admirable ! “

Rosamund waved her black-lead brush and tasted victory.

The process of acclimatisation naturally affected her health.

In a month’s

time she began to fear that she must break down ;

she suffered painful

disorders, crept out of sight to moan and shed

a tear. Always faint, she

had no appetite for wholesome food.

Tossing on her bed at night she said

to herself a thousand times :

” I must go on even if I die ! ” Her

religion took the form of

asceticism and bade her rejoice in her miseries

; she prayed

constantly and at times knew the solace of an infinite

self-glorifica-

tion. In such a mood she once said to Mrs. Halliday :

” Don’t you think I deserve some praise for the step I took ? “

” You certainly deserve both praise and thanks from me.”

” But I mean—it isn’t every one who could have done it ? I’ve

a

right to feel myself superior to the ordinary run of girls ? :

The other gave her an embarrassed look, and murmured a few

satisfying

words. Later in the same day she talked to Rosamund

about her health and

insisted on making certain changes which

allowed her to take more open-air

exercise. The result of this

was

was a marked improvement ; at the end of the second month

Rosamund began to

feel and look better than she had done for

several years. Work no longer

exhausted her. And the labour

in itself seemed to diminish, a natural

consequence of perfect

co-operation between the two women. Mrs. Halliday

declared

that life had never been so easy for her as now ; she knew the

delight of rest in which there was no self-reproach. But for

sufficient reasons she did not venture to express to Rosamund all

the

gratitude that was due.

About Christmas a letter from Forest Hill arrived at Ted-

dington ; this

time it did not forbid a reply. It spoke of struggles

sufferings,

achievements. ” Do I not deserve a word of praise ?

Have I not done

something, as you said, towards solving the

great question ? Don t you

believe in me a little ? ” Four

more weeks went by, and brought no answer.

Then, one

evening, in a mood of bitterness, Rosamund took a singular step

;

she wrote to Mr. Cheeseman. She had heard nothing of him, had

utterly lost sight of the world in which they met ; but his place

of

business was known to her, and thither she addressed the note.

A few lines

only : ” You are a very strange person, and I really

take no interest

whatever in you. But I have sometimes thought

you would like to ask my

forgiveness. If so, write to the above

address—my sister’s. I am

living in London, and enjoying

myself, but I don’t choose to let you know

where.” Having an

opportunity on the morrow, Sunday, she posted this in a

remote

district.

The next day, a letter arrived for her from Canada. Here

was the

explanation of Geoffrey s silence. His words could

hardly have been more

cordial, but there were so few of them.

On nourishment such as this no

illusion could support itself ; for

the moment Rosamund renounced every

hope. Well, she was no

worse

worse off than before the renewal of their friendship. But could

it be

called friendship ? Geoffrey’s mother and sisters paid no

heed to her ;

they doubtless considered that she had finally sunk

below their horizon ;

and Geoffrey himself, for all his fine words,

most likely thought the same

at heart. Of course they would

never meet again. And for the rest of her

life she would be

nothing more than a domestic servant in genteel

disguise—

happy were the disguise preserved.

However, she had provided a distraction for her gloomy

thoughts. With no

more delay than was due to its transmission

by way of Glasgow, there came

a reply from Mr. Cheeseman :

two sheets of notepaper. The writer

prostrated himself ; he had

been guilty of shameful behaviour ; even Miss

Jewell, with all her

sweet womanliness, must find it hard to think of him

with

charity. But let her remember what ” the poets ” had written

about Remorse, and apply to him the most harrowing of

their

descriptions. He would be frank with her ; he would “a plain,

unvarnished tale unfold.” Whilst away for his holiday he by

chance

encountered one with whom, in days gone by, he had

held

tender relations. She was a young widow ; his foolish heart was

touched ; he sacrificed honour to the passing emotion. Their

marriage

would be delayed, for his affairs were just now any-

thing but flourishing.

” Dear Miss Jewell, will you not be my

friend, my sister ? Alas, I am not

a happy man ; but it is too

late to lament.” And so on to the squeezed

signature at the

bottom of the last page.

Rosamund allowed a fortnight to pass—not before writing, but

before

her letter was posted. She used a tone of condescension,

mingled with airy

banter. ” From my heart I feel for you, but,

as you say, there is no help.

I am afraid you are very impulsive

—yet I thought that was a fault

of youth. Do not give way to

despair

despair. I really don’t know whether I shall feel it right to let

you hear

again, but if it soothes you I don’t think there would be

any harm in your

letting me know the cause of your troubles.”

This odd correspondence, sometimes with intervals of three

weeks, went on

until late summer. Rosamund would soon

have been a year with Mrs.

Halliday. Her enthusiasm had long

since burnt itself out ; she was often a

prey to vapours, to cheer-

less lassitude, even to the spirit of revolt

against things in general,

but on the whole she remained a thoroughly

useful member of the

household ; the great experiment might fairly be

called successful.

At the end of August it was decided that the children

must have

sea air ; their parents would take them away for a fortnight.

When the project began to be talked of, Rosamund, perceiving

a

domestic difficulty, removed it by asking whether she would be

at liberty

to visit her sister in Scotland. Thus were things

arranged.

Some days before that appointed for the general departure.

Halliday

received a letter which supplied him with a subject of

conversation at

breakfast.

” Hunt is going to be married,” he remarked to his wife,

just as Rosamund

was bringing in the children s porridge.

Mrs. Halliday looked at her helper—for no more special reason

than

the fact of Rosamund’s acquaintance with the Hunt family ;

she perceived a

change of expression, an emotional play of feature,

and at once averted

her eyes.

” Where ? In Canada ? ” she asked, off-hand.

” No, he’s in England. But the lady is a Canadian.—I

wonder he

troubles to tell me. Hunt’s a queer fellow. When

we meet, once in two

years, he treats me like a long-lost brother ;

but I don’t think he’d care

a bit if he never saw me or heard of

me again.”

” It’s

” It’s a family characteristic,” interposed Rosamund with a dry

laugh.

That day she moved about with the gait and the eyes of a som-

nambulist. She

broke a piece of crockery, and became hysterical

over it. Her afternoon

leisure she spent in the bedroom, and at

night she professed a headache

which obliged her to retire early.

A passion of wrath inflamed her ; as vehement—though so

utterly

unreasonable—as in the moment when she learnt the

perfidy of Mr.

Cheeseman. She raged at her folly in having

submitted to social

degradation on the mere hint of a man

who uttered it in a spirit purely

contemptuous. The whole

hateful world had conspired against her. She

banned her kins-

folk and all her acquaintances, especially the Hunts ; she

felt

bitter even against the Hallidays—unsympathetic, selfish

people,

utterly indifferent to her private griefs, regarding her as a mere

domestic machine. She would write to Geoffrey Hunt, and let

him know

very plainly what she thought of his behaviour in

urging her to become a servant. Would such a thought

have

ever occurred to a gentleman ! And her

poor life was wasted, oh !

oh ! She would soon be thirty—thirty !

The glass mocked her

with savage truth. And she had not even a decent

dress to put

on. Self-neglect had made her appearance vulgar ; her

manners,

her speech, doubtless, had lost their note of social superiority.

Oh,

it was hard ! She wished for death, cried for divine justice in a

better world.

On the morning of release, she travelled to London Bridge,

ostensibly en route for the north. But, on alighting, she had her

luggage taken to the cloak-room, and herself went by omnibus to

the

West-end. By noon she had engaged a lodging, one room in a

street where

she had never yet lived. And hither before night

was transferred her

property.

The

The next day she spent about half of her ready-money in the

purchase of

clothing—cheap, but such as the self-respect of a

” lady ”

imperatively demands. She bought cosmetics ; she set to

work at removing

from her hands the traces of ignoble occupation.

On the day that

followed—Sunday—early in the afternoon, she

repaired to a

certain corner of Kensington Gardens, where she

came face to face with Mr.

Cheeseman.

” I have come,” said Rosamund, in a voice of nervous exhilara-

tion which

tried to subdue itself. ” Please to consider that it is

more than you

could expect.”

” It is ! A thousand times more ! You are goodness itself.”

In Rosamund’s eyes the man had not improved since a year ago.

The growth of

a beard made him look older, and he seemed in

indifferent health ; but his

tremulous delight, his excessive homage,

atoned for the defect. She, on

the other hand, was so greatly

changed for the better that Cheeseman

beheld her with no less

wonder than admiration. Her brisk step, her

upright bearing,

her clear eye, and pure-toned skin contrasted remarkably

with the

lassitude and sallowness he remembered ; at this moment, too, she

had a pleasant rosiness of cheek which made her girlish, virginal.

All was set off by the new drapery and millinery, which threw a

shade upon

Cheeseman’s very respectable but somewhat time-

honoured, Sunday costume.

They spent several hours together, Cheeseman talking of his

faults, his

virtues, his calamities, and his hopes, like the impul-

sive, well-meaning,

but nerveless fellow that he was. Rosamund

gathered from it all, as she

had vaguely learnt from his recent

correspondence, that the alluring widow

no longer claimed him ;

but he did not enter into details on this delicate

subject. They

had tea at a restaurant by Netting Hill Gate ; then, Miss

Jewell

appearing indefatigable, they again strolled in unfrequented ways.

The Yellow Book—Vol. VIII. C

At

At length was uttered the question for which Rosamund had long

ago prepared

her reply.

” You cannot expect me,” she said sweetly, ” to answer at once.”

” Of course not ! I shouldn’t have dared to hope—”

He choked and swallowed ; a few beads of perspiration shining

on his

troubled face.

” You have my address ; most likely I shall spend a week or two

there. Of

course you may write. I shall probably go to my

sister’s in Scotland, for

the autumn—”

” Oh ! don’t say that—don’t. To lose you again—so soon—”

” I only said, ‘probably ‘—”

” Oh, thank you !—To go so far away—And the autumn ;

just

when I have a little freedom ; the very best time—if I

dared to

hope such a thing—”

Rosamund graciously allowed him to bear her company as far

as to the street

in which she lived.

A few days later she wrote to Mrs. Halliday, heading her

letter with the

Glasgow address. She lamented the sudden im-

possibility of returning to

her domestic duties. Something had

happened. “In short, dear Mrs.

Halliday, I am going to be

married. I could not give you warning of this,

it has come so

unexpectedly. Do forgive me ! I so earnestly hope that you

will

find some one to take my place, some one better and more of a help

to you. I know I haven t been much use. Do write home at

Glasgow and

say I may still regard you as a dear friend.”

This having been dispatched, she sat musing over her prospects.

Mr.

Cheeseman had honestly confessed the smallness of his income ;

he could

barely count upon a hundred and fifty a year ; but things

might improve. She did not dislike him—no, she

did not dislike

him. He would be a very tractable husband. Compared, of

course, with—

A letter

A letter was brought up to her room. She knew the flowing

commercial hand,

and broke the envelope without emotion. Two

sheets—three

sheets—and a half. But what was all this ?

” Despair . . . thoughts

of self-destruction . . . ignoble pub-

licity . . . practical ruin . . .

impossible . . . despise and

forget . . . Dante’s hell . . . deeper than

ever plummet

sounded . . . forever !….” So again he had deceived her !

He

must have known that the widow was dangerous ; his reticence was

mere shuffling. His behaviour to that other woman had perhaps

exceeded in

baseness his treatment of herself ; else, how could he

be so sure that a

jury would give her ” ruinous damages ” ? Or was

it all a mere

illustration of a man s villainy ? Why should not she

also sue for damages ? Why not ? Why not ?

The three months that followed were a time of graver peril, of

darker

crisis, than Rosamund, with all her slip-slop experiences,

had ever known.

An observer adequately supplied with facts,

psychological and material,

would more than once have felt that

it depended on the mere toss of a coin

whether she kept or lost

her social respectability. She sounded all the

depths possible to

such a mind and heart—save only that from which

there could

have been no redemption. A saving memory lived within her,

and at length, in the yellow gloom of a November morning—her

tarnished, draggle-tailed finery thrown aside for the garb she had

worn in

lowliness—Rosamund betook herself to Forest Hill. The

house of the

Hallidays looked just as usual. She slunk up to the door,

rang the bell,

and waited in fear of a strange face. There appeared

Mrs. Halliday

herself. The surprised but friendly smile at once

proved her forgiveness

of Rosamund’s desertion. She had written,

indeed, with calm good sense,

hoping only that all would be well.

” Let me see you alone, Mrs.

Halliday.—How glad I am to sit

in this room again ! Who is helping

you now ? ”

” No

” No one. Help such as I want is not easy to find.”

” Oh, let me come back !—I am not

married.—No, no, there is

nothing to be ashamed of. I am no worse

than I ever was. I ll

tell you everything—the whole silly, wretched

story.”

She told it, blurring only her existence of the past three

months.

” I would have come before, but I was so bitterly ashamed. I

ran away so

disgracefully. Now I’m penniless—all but suffering

hunger. Will you

have me again, Mrs. Halliday ? I’ve been a

horrid fool, but—I do

believe—for the last time in my life. Try

me again, dear Mrs.

Halliday ! ”

There was no need of the miserable tears, the impassioned

pleading. Her

home received her as though she had been absent

but for an hour. That

night she knelt again by her bedside in

the little room, and at seven

o’clock next morning she was light-

ing fires, sweeping floors, mute in

thankfulness.

Halliday heard the story from his wife, and shook a dreamy,

compassionate

head.

” For goodness’ sake,” urged the practical woman, ” don’t let

her think

she’s a martyr.”

” No, no ; but the poor girl should have her taste of happi-

ness.”

” Of course I’m sorry for her, but there are plenty of people

more to be

pitied. Work she must, and there’s only one kind of

work she’s fit for.

It’s no small thing to find your vocation—is it ?

Thousands of such

women—all meant by nature to scrub and

cook—live and die

miserably because they think themselves too

good for it.”

” The whole social structure is rotten ! ”

” It’ll last our time,” rejoined Mrs. Halliday, as she gave a little

laugh

and stretched her weary arms.

A Southerly Air

By A. Frew

Rest

By Arthur Christopher Benson

TO-DAY I’ll give to peace : I will not look

Behind, before me ; I will simply be ;

Hopes and regrets shall claim no share in me ;

Here will I lie, beside the leaping brook,

And turn the pages of some aimless book,

Sunk and submerged in vague felicity ;

Live, mute, and still, in what I hear and see,

The dreaming guardian of the upland nook.

Well, here’s my world to-day ! cicalas spare

Sawing harsh music ; beetles big, that grope

Among the grass-stems ; merry flies astir ;

And goats with impudent face and silken hair,

That poise and tinkle on the Western slope,

Breast deep in Alpen-rose and juniper.

Study of a Calf

By D. Gauld

Two Stories

By Frances E. Huntley

I—Points of View

WHENEVER she recalled that incredible moment, she was

conscious of a

strange emotional excitement, that thrilled

her with an exquisite

poignancy, that set blushes momentarily

flaming, that darkened her eyes,

and parted her quick-breathing

lips. She felt a little ashamed of the

sensation, so that she

wanted to put into words, to get somebody else’s

opinion on,

what had occurred the evening before in the seductive

corridor,

where the lights were turned low nearly to extinction, and the

scent of flowers penetrated and grew, till it took that keen

metallic odour that seems almost tangible.

The scene, familiar to weariness, had held for her always a

repulsion no

less than an attraction ; it seemed such a bid for

playing at passion, and

yet—commonplaces were so invariable

there ! Talk of the

decorations, the floor, the guests, perhaps, as

a rarer topic, the more or

less uninteresting personality of her

partner, minutely

investigated—these had been the associations of

the corridor : not

that she had wished it otherwise, far from that ;

but . . . well ! the

feeling had been inexplicable, a mixture of

relief and disappointment,

that still there was so much to learn,

that still it remained unlearnt.

And

And the teacher ? For him, she had imagined herself fas-

tidious, critical

of shades of manner, almost impossible to please ;

and now, this morning !

… It had been a man whom she

hardly knew, but with whom she felt

conicious of a strange

intimacy. He, too, repulsed and attracted her at

once ; said

things to her that in any one else she would have passionately

resented, spoke to her with an almost obtrusive sans-gêne, did not

even especially amuse her, and

yet—his attraction was invincible.

Directly she came into a

ball-room where he was, she perceived

him, freshly disapproved of him,

smiled at him, disarranged her

card to include his dances, and, the dance

over, came to sit out, in

a corridor such as that last night, all

voluptuousness and allurement.

. . . She raged at herself perpetually, and

would talk, none the

less, her wittiest and brightest, and glance gaily

into the eyes that

looked back at her with a somewhat posé cynicism.

Last night ! Over and over again the scene recalled itself, and

thrilled

her with that curious tremor. . . . She longed for a

clearer view of it, a

cool, unswayed opinion . . . yet to tell !

It would be schoolgirlish,

typical almost of silly loquacious

womanhood ; that was her first thought,

then came another : the

woman of the world—the half-cynical,

half-tender type that

attracted her so strongly, that she had met with in

one woman,

and loved so dearly. Would she have

told ? Yes, she could

fancy her, in her bright allusive way, with her wide

roguish gaze,

and enchanting suggestion of a brogue. . . . So, she would tell,

and then, she laughed to think how

much she was making of it ;

it was such a little thing after all, wasn’t

it ? … But she

wavered again. It would sound so crude, such a bald,

almost

vulgar, statement. For, when all was said and done, what had

happened ? . . . In the moment that she felt her cheek tinge

itself again

with that vivid pink, another memory came to her,

vaguely

vaguely, as it seemed, unmeaningly—of a public ball she had once

gone to (a rare thing with her, she didn’t care enough for dancing

to pay

for it, she always said), a ball at which were to be seen

many people of

whose manners and customs she was entirely

ignorant. A scene she had

witnessed there ! . . . the remem-

brance possessed her, a kind of

unconscious cerebration, for which

she could not account.

A corridor, once more almost deserted, save for herself and her

partner,

and, at the farther end, another couple, people she had

never seen before

; the girl, flaunting, ill-dressed, in a gown of

insistently meagre

insufficiency, her hair heaped into unmeaning

shapelessness, nowhere an

outline, a severity, a grave dainty

coquetry ; the effect was almost

pathetic in its dull, bold cheap-

ness. And the man !—hardly more,

indeed, than a boy—he bore

the huddled indistinctness, the look of

imperfect detachment from

the atmosphere, whose opposite we convey by the

word ” distinc-

tion.”

So, in a glance, she had seen them ; and, with a kind of absent

curiosity,

had watched them while she talked . . . Quite suddenly

the man slipped to

the ground beside his partner’s chair, and passed

his arm familiarly,

jocosely, round her unreluctant waist. A

moment more and their faces

touched, their lips met, in a kiss

. . . one which, it was abundantly

evident, was not of deep

feeling, or even the expression of an instant’s

real emotion ; no,

there was an ineffable commonness, a painful coarsening

of the

action, visible even to unaccustomed eyes … it was ” sport.”

The girl had probably invited it ; the man, more than probably,

was

not the first who had been privileged. . . .

She had felt revolted.

Her partner had made some contemptuous remark : ” Can’t

they do it in

private ! If she likes being hugged—” The

mere

mere words had set her cheeks on fire, the careless, half-amused

scorn of

his tone, the matter-of-course for which he had

taken it. She had rushed

into one of her impetuous, heedless

speeches :

” I would rather have a girl who has the realness in

her to do

something honestly wrong ! One can’t call that

‘wrong’—no,

too good a word. It’s only futile, common. Oh, better

the poor

girls whose weakness has something real in it,

some—courage,

foolishness . . . But that sort ! ”

The ring of her voice sounded in her ears when she recalled

the scene. It

had stamped itself oddly on her memory, was always

coming back to her,

haunting her. . . .

The clear, tender pink still lingered on her cheek ; for, once

more, the

public ball forgotten, she had gone over that little

episode in the

corridor last night—in the deserted, solitary corridor.

Why did it

thrill her so ? She did not love the man who had

thus surprised

her—love him ! Why, her acquaintance with him

was of the slightest

; and his feeling for her ? She could not

conceivably delude herself about

that ; it was very much the same,

she divined, as hers for him . . . Then

why was it ? He was

the first who had ever

kissed her—could that be it ?

At the time she had felt angry, but more hurt than angry ;

hurt at his

audacity ; it seemed as if he must have thought her a

girl who very

lightly ” took a fancy ” for a man, a girl who was

easily attracted. . . .

Some analogy was worrying her, something

like it that had happened before,

something she had read perhaps.

. . . What could it be ? Why could she not

remember ?

Great heaven ! the girl at the public ball, the girl who had let

a man kiss

her for sport ! ” That sort ! ” . . .

Oh, no, no, there was no likeness, none, no analogy, no possible

comparison. She, with her pride, and refinement, and high-flown

romantic

romantic idealism in her theory that anything real was better than

that

futile fingering of edged tools. . . . And that wild-haired,

cheap

tawdriness. . . .

She writhed in restless, rebellious shame, her hands covered her

face,

where the soft rosiness was turning to thick suffusing scarlet.

. . .

After all, if any one had seen, it must have looked quite the

same, quite,

quite the same.

The thought was intolerable. What was she to do ? How

get some denial of

this sickening suspicion. Tell her sister, ask

her what she thought ? Ah,

no, no ; now she could never tell

. . . and, in the glass, it seemed to

her that her eyes looked bold

and glittering, and her hair, with its

carefully followed outlines

and burnished softly-curving richness,

appeared shapeless, unkempt

unconsidered . . . Her ball-gown ! she tore it

from the box where

it lay in its fragrant mistiness … it was

disgraceful, it was

immodest almost, she would never wear it again, never

dance

again, never see that man again. . . .

And as she stood before the glass, with passionate quivering

lips, and eyes

burning with stinging unfallen tears, the strange

delicious thrill stole

through her once more, the roseate flickers

glowed on her cheek, the kiss

seemed to touch her once more

with its lingering pressure. . . . Ah,

surely there was a point of

view, surely there was a difference ?

She tasted in that moment something of the weakness of

womanhood—its

pitiful groping artificiality, its keen passionate

realness.

I CAN

II—Lucille

I CAN hardly expect you to understand me, I fear—for, if the

truth

be told, I understand myself not at all ; and of Lucille,

my comprehension

is, at best, just not misapprehension : though

of that, even, I feel at

times uncertain enough.

Well, after this morning, I suppose I need not think about it

any more.

Need not ! must not would express it better : the

last word, so far as I am concerned in it, has been said ; the

curtain has rung down upon the little comedy-tragedy that I had

(I might

say) written, or, at any rate, conceived, entirely by and

for myself ; and

it has left me, the author, in a puzzlement that

is, to treat it lightly,

extremely disconcerting. I can’t help

having the preposterous feeling that

it is partly my fault that it

has ended so, and of course, you know, it

isn’t, couldn’t be !

If we will take our drama in real life, we must not

expect the

unexpected, we must—strenuously—remember that we

are author

and audience both, that we see the thing from the inside, that

we

must be prepared for things actually happening, just as they seem

to be going to happen.

I suppose I thought I had thus reasoned it all out, but I see

now that my

vision was irrevocably warped, that I was looking

out, with a playgoer’s

certainty of anticipation, for the unpre-

pared—for the unexpected.

. . . But (I meant to have said

sooner) it occurs to me that, if I put it

into words for you, if I

reduce it, so to speak, to black and white, we

may contrive

between us to come to some sort of an understanding about it,

to

unravel at least one or two of the threads, to get, in short, an

approximate idea of that slender humorous enigma whom we used

to call

Lucille Silverdale.

So

So now, if you are not alarmed at, repelled by, the prospect of a

riddle, a

puzzle—oh, but a very charming puzzle in brown hair

and hazel eyes

and sensitive contours . . . ?

Mrs. Silverdale, if she did not openly bemoan her fate, yet

intimated

tolerably plainly her resentment at the trick which

nature had played upon

her ; and, far from in sympathy though I

felt with her, I could not deny

that, from her point of view, there

might be an excuse for her attitude.

Her attitude ? But, in

truth, that is hardly the word ; it was more a

resigned recog-

nition that there was no possible attitude to be taken up,

a kind

of mental huddle, a backboneless disapproval, an appallingly silent

silence.

From the culprit herself, little aggression could be complained

of ;

Lucille was, perhaps, as much ashamed of her inconvenience,

her inconvenance, as were the most robust-minded of her

family ;

but (it seemed to me) this very modesty, this very agreement with

their envisagement of the situation, did but add an irritation the

more to her personality.

Strange enough it was, too ; one is used to see it taken so differ-

ently,

that perfunctory law whereby the ages free themselves from

the muffling

oblivion of mankind—that poking, freakish finger that

heredity

sticks in our eyes, as we peer anxiously to see if the veil

be decorously

thrown over all. The tears it brings—that mocking

inexorable

finger—are not always of those that purify our mental

vision ; and

of the Silverdales’ sight, so far as that concerned itself

with this

slender, humorous maiden, it had made miniature havoc.

That, after all these dear mediocre centuries, he should re-assert

himself—that ancestor, who in the days of Herrick and Suckling

had

held his own wittily, gloriously, with the best of them !

One might have

hoped that decades upon decades of ignoring,

of

of snubbing, would have quelled his ghostly essence, would have

taught his

undying part that at any rate it was not wanted among

the posterity of his

race. But (and the situation really had its

pathetic side) here it was,

with the flair of these uncanny insub-

stantialities, finding a welcome at last (though not perhaps of the

most

rapturous) in the great—great—oh, je vous le

donne en mille !

—in the thousandth great-niece, Lucille

Silverdale, daughter and

sister of, in abstract phrase, the Healthy

Commonplace of the

British Nation. It was rare enough, as I

said—that shrinking

from, that deprecation of, their sole title to

distinction ; one longed

to trace it back to its source, to discover from

what veil that

impish ringer had darted,

whether, to add a quaintness the more,

he, the wit, the sweet singer of

that honeyed age, had been as

unwelcome to his family circle as she, the

somewhat unwilling

inheritress of his genius, was to hers. But of that

bygone blazon

upon the Silverdale ‘scutcheon, it would have been

ill-advised,

perilous to speak ; to Lucille even the subject was painful,

and

in the most impracticable sort of way.

She did say to me once, in a moment of acute dejection, that

in any other

family she would probably have been the idol, in-

sufferably thrust for

worship upon every new-comer. ” But as

it is,” she finished sadly, though

with her unquenchable twinkle,

” I am a skeleton, rattling my impossible

bones, not in a nice

musty hiding-place of my own, but in the comfortable,

general

family-cupboard, which they can’t open without seeing me. And

they have to open it every day—before visitors, too ! ”

If I laughed somewhat oppressively at her analogy, I daresay

she divined

part of the reason, and didn’t wonder that her amazing

comicality should

have filled my eyes with tears. . . .

Well, skeleton or idol, she was sufficiently lonely. They were

all so

rudely healthy-minded, so full of the working-out of their

rosy-

rosy-cheeked conception of the joie de vivre (if it

set one wondering

and shuddering, that was one’s own concern), so

insistent in

exuberance and jollity, that it was no marvel if they had

little

time, or inclination to make it, for a dreamer of dreams, a seer of

visions, a hearer of the music of the spheres. Not that any of

those

would have been their definition of Lucille : to them, she

was a

sentimentalist, a ” mooney.” Yet, apart from the unnatural-

nesses into

which she would pathetically force herself, she had her

soft appealing

wildnesses, her gay roguish outbreaks, her bright

apologetic