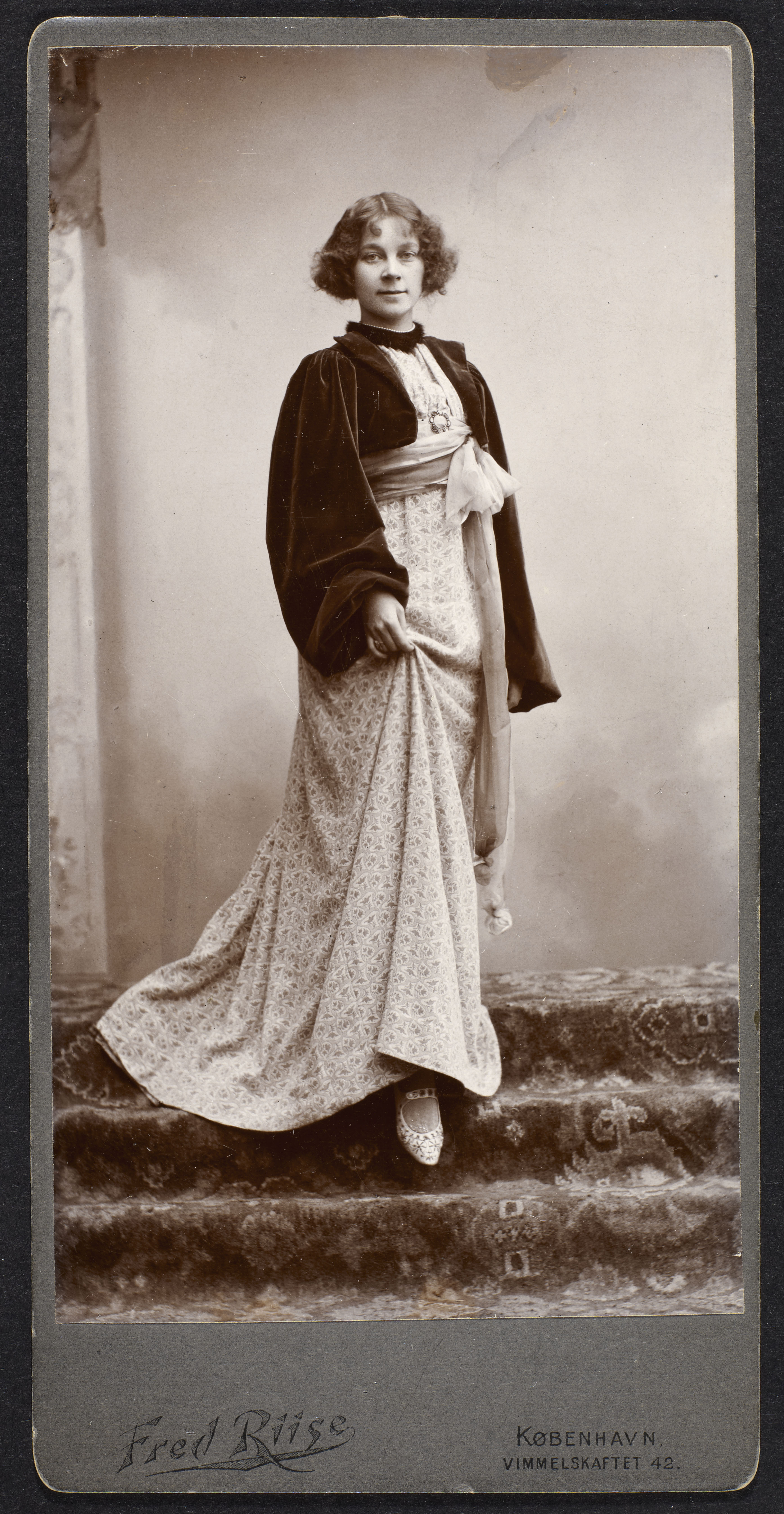

Julie Nørregaard

(1863 – 1942)

Julie Nørregaard (Nørregaard Le Gallienne upon marriage in 1897) contributed only one essay to The Yellow Book, in Volume 8, January 1896. Her introduction to the magazine was most likely through Richard Le Gallienne (1866-1947), one of the periodical’s most regular contributors, whom she married in 1897. Their stormy relationship ended in 1903, when they separated; he moved to New York and she to Paris with their child, Eva (1899-1991). Nørregaard’s essay in The Yellow Book reflects her cultural background as a Dane: it is a long eulogy of one of the leading Danish intellectuals, Dr. Georg Brandes (1842-1927), who, since the 1870s, had brought the thoughts and writings of the French, German, and English avant garde to Denmark. His monograph on Disraeli, Lord Beaconsfield: A Study, appeared in an English translation in 1880, only two years after its first publication in Danish. Nørregaard’s essay on Brandes is a puff piece on his monograph on William Shakespeare, which first appeared in Danish from William Heinemann in the spring of 1896, and then in an English translation by William Archer, Mary Morrison, and Diana White under the title William Shakespeare: A Study (London: William Heinemann, 1898). Nørregaard’s worship of Brandes is symptomatic of his cult status in the more radical Danish intellectual circles, especially among his many female admirers. When visiting London in the late 1890s to promote his Shakespeare monograph, Brandes was disappointed to find he was not lionized there to the same extent as he was at home.

From the limited archival material on Julie Nørregaard’s life and the biographies and autobiographies of her spouse and daughter, Nørregaard emerges as a resourceful, independent woman with a passion for the theatre, fashion, and women’s education and sexual freedom. Her life was a cosmopolitan one spent in Copenhagen, London, Paris, and New York, major cities in which she maintained social and professional circles throughout most of her life. She played a significant role as supporting wife or mother: acting as helpful go-between for both Richard and Eva, she provided introductions and established links between Danish, English, French, or American artists or writers. This supportive role alternated with Nørregaard’s activities as a hard-working journalist. Churning out articles to cover the most basic daily expenses, she wrote hundreds of newspaper and magazine columns in both Danish and English. Her literary output is uncollected and includes published translations of three short Danish novels and of Henrik Ibsen’s play Hedda Gabler (1928). She also left an unfinished novel and an unfinished anthology of Scandinavian writings.

Nørregaard was born to Danish parents in Flensborg in the North of Germany. The family moved to Copenhagen in 1864 to escape the German invasion of Schleswig-Holstein. Little is known of her early years and education, except that her upper-middle-class parents ensured that she had good language skills in English and French, stimulated by the many English and French books and magazines her father brought back from his travels. Nørregaard developed an early interest in the theatre, attending the world première of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House in Copenhagen in 1879, and seeing Sarah Bernhardt on her Copenhagen tours performing in Fédora and Froufrou. In the 1880s she formed friendships with Brandes and with the Danish writer Peter Nansen (1861-1918). In 1884 Brandes co-founded the liberal newspaper Politiken, which served as an important organ for the cultural radicalism he and his brother Edvard (1847-1931) were advocating in their attempts to invigorate Danish cultural debate. Against her parents’ will, Julie attended his flamboyant public lectures on aesthetics and modern writing. Her friendship with Nansen and Brandes led to a career as a journalist for Politiken. From the early 1890s until shortly before the Second World War, Nørregaard contributed regular columns on fashion, embroidery, women’s issues, royalty, and theatre, writing under the pseudonym of “Eva.” She gradually established herself as a journalist, contributing not merely to the Scandinavian press, but also to such English papers as The Star, The Morning Leader, The Daily Courier, and Town and Country .

In the early 1890s she moved with her sister Ellen to London to sell samples of Danish embroidery at the Danish Art School in Bayswater and to develop her writing career. After encountering Le Gallienne, she became part of his circles of aesthetes, writers, and publishers, meeting Walter Crane (1845-1915), William Sharp (1855-1905), John Lane (1854-1925), and William Heinemann (1863-1920).

Nørregaard’s fascination with the forceful female characters in Ibsen’s plays, combined with her own life experience, helped her argue in her columns for women’s independence and right to acknowledge both their intellect and their sexuality. Richard Le Gallienne’s alcoholism, combined with his womanizing and extravagant habits, left her without any financial support both during their marriage and after their separation. Through journalism and translation, she supported not only herself and her daughter, but also a nanny and Richard’s daughter from his first marriage. When journalistic jobs became scarce in 1906, she turned to millinery and found her customers among the international community on the Rive Gauche: her hat shop in Paris, “Mme. Fédora,” located in her drawing room, provided the female friends of H.G. Wells (1866-1946) and Arnold Bennett (1867-1931) with hats from 1906 till 1914, when she left France. Moving first to London, Nørregaard left soon afterwards for New York to promote her daughter’s pursuit of an acting career. She remained in New York until Eva established herself on the American stage, returning to London in 1920. Here she pursued her journalistic career until shortly before the Second World War, when she moved once again to America. Julie Nørregaard died from lung cancer under her daughter’s care in 1942.

During the 1890s Nørregaard served as an important connecting link between British and Danish aestheticism. Through her contact with Brandes, she provided Danish artists and writers with introductions and access to London magazines, publishers, critics, and exhibition venues. She negotiated with William Heinemann for the English translation of some of Peter Nansen’s novels, and planned to bring out an anthology of Scandinavian writing with the title Northern Lights with John Lane. Her translation of Nansen’s controversial Love’s Trilogy: Julie’s Diary, Maria, God’s Peace was published by Heinemann in 1906. She took paintings to the Royal Academy and the New Gallery for the Danish “Pre-Raphaelites,” Agnes and Harald Slott-Møller, introduced the two to Walter Crane and William Sharp, and promoted their work with The Magazine of Art . Similarly, she had her daughter introduced to Sarah Bernhardt several times in Paris, and to William Faversham and other leading actors in London. Nørregaard’s discreet role as go-between for others has overshadowed her own impressive and adventurous life and career, leaving them still to be fully chronicled.

© 2011, Lene Østermark-Johansen

Lene Østermark-Johansen is Reader in English at the University of Copenhagen. She is the author of Sweetness and Strength: The Reception of Michelangelo in Late Victorian England (Ashgate 1998), and, most recently, of Walter Pater and the Language of Sculpture (Ashgate 2011). She has also published on Oscar Wilde, Algernon Swinburne, and Frederic Leighton and is currently working on an edition of Pater’s Imaginary Portraits.

Published Translations by Julie Nørregaard

- Nansen, Peter. Love’s Trilogy: Julie’s Diary, Maria, God’s Peace . Trans. Julia [sic] Le Gallienne. London: William Heinemann, 1906.

- Ibsen, Henrik. Hedda Gabler. Revised Trans. Julie Le Gallienne and Paul Leyssac. In Eva le Gallienne’s Civic Repertory Plays . New York: Norton, 1928.

Archival Material about Julie Nørregaard

- Royal Library Copenhagen: Letters between Julie and the Slott-Møllers, Peter Nansen and a few other Danish correspondents.

- Library of Congress, Washington: The Eva Le Gallienne papers MSS 84002. (contain family correspondence and many columns that Eva contributed to Danish and English magazines.)

- Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, Austin Texas: Correspondence between Julie Nørregaard and John Lane’s publishing house.

Selected Publications Referencing Julie Nørregaard

- Le Gallienne, Eva. With a Quiet Heart. New York: Viking, 1953.

- Sheeny, Helen. Eva le Gallienne: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

- Whittington-Egan, Richard and Geoffrey Smerdon. The Quest of the Golden Boy: The Life and Letters of Richard Le Gallienne . London: Unicorn, 1960.

MLA citation:

Østermark-Johansen, Lene. “Julie Nørregaard (1863-1942),” Y90s Biographies, 2011. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/norregaard_bio/.