The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume IV January 1895

Contents

Literature

I. Home . . . . By Richard Le

Gallienne Page 11

II. The

Bohemian Girl . Henry Harland . . 12

III. Vespertilia . . . Graham

R. Tomson . . 49

IV. The House of Shame

. H. B. Marriott Watson . 53

V. Rondeaux d’Amour . Dolf

Wyllarde . . . 87

VI. Wladislaw’s Advent

. Ménie Muriel Dowie . 90

VII. The Waking of Spring . Olive

Custance . . 116

VIII. Mr. Stevenson’s

Fore-runner James Ashcroft Noble .

121

IX. Red Rose . . . Leila Macdonald . . 143

X. Margaret

. . . C. S. . . . . 147

XI. Of One in Russia . . Richard

Garnett, LL.D. . 155

XII. Theodora, a

Fragment . Victoria Cross . . . 156

XIII. Two Songs . . . Charles

Sydney . . 189

XIV. A Falling Out

. . Kenneth Grahame . . 195

XV. Hor. Car. I. 5 . . Charles

Newton-Robinson 202

XVI. Henri Beyle

. . . Norman Hapgood . . 207

XVII. Day and Night . . E. Nesbit

. . . 234

XVIII. A Thief in the Night

. Marion Hepworth Dixon . 239

XIX. An Autumn Elegy . . C. W.

Dalmon . . 247

XX. The End of an

Episode . Evelyn Sharp . . . 255

XXI.

1880 . . . . Max Beerbohm

. . 275

XXII. Proem to “The Won-derful Mission of Earl Lavender” John Davidson . . 284

Art

The Yellow Book—Vol. IV.—January, 1895

Art

Front Cover, by Aubrey Beardsley

Title Page, by Aubrey Beardsley

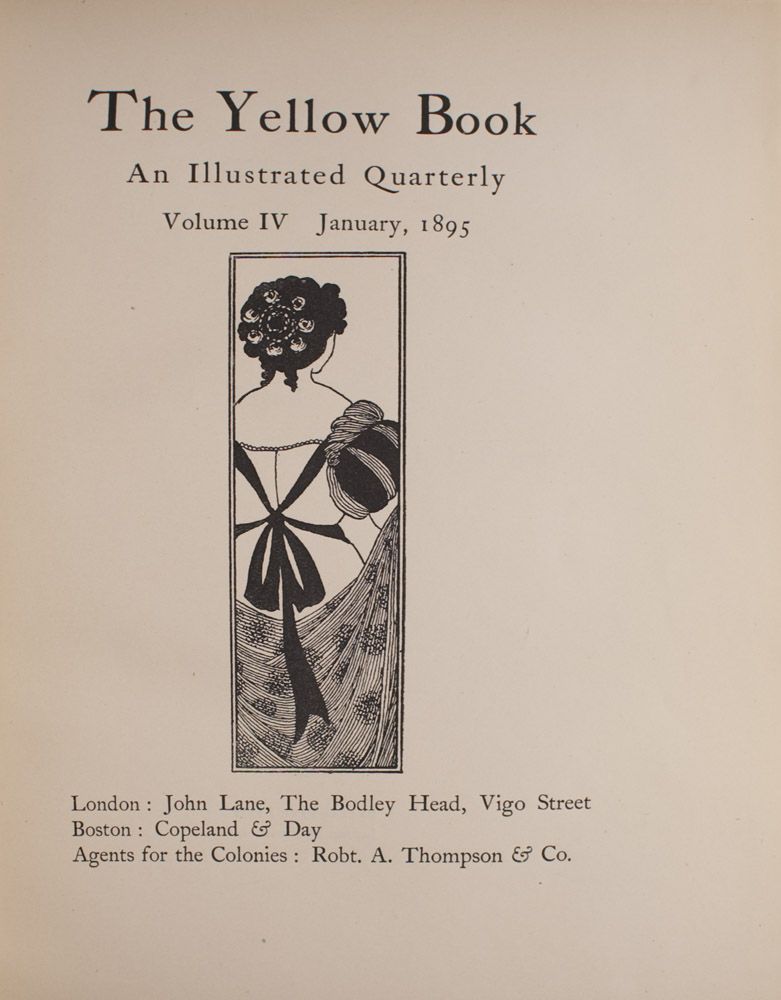

I. Study of a Head . . By H. J.

Draper . . Page 7

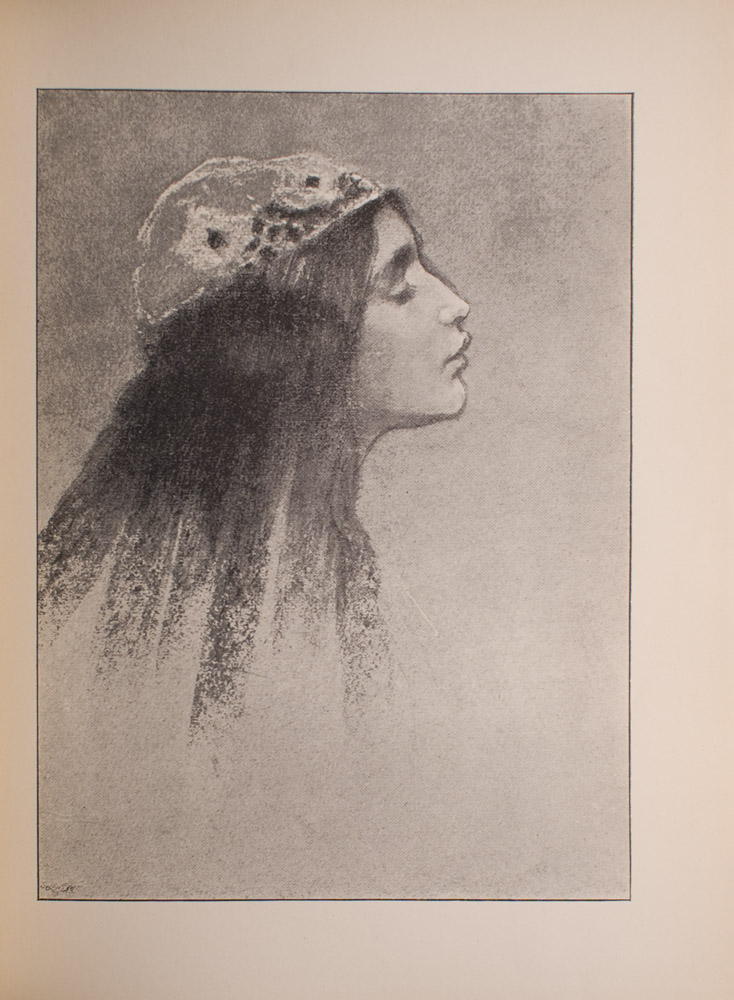

II. A Sussex Landscape . William

Hyde . . 45

III. Hotel Royal, Dieppe

Walter Sickert . .

80

IV. Bodley Heads. No. I : Mr. Richard

Le Gallienne

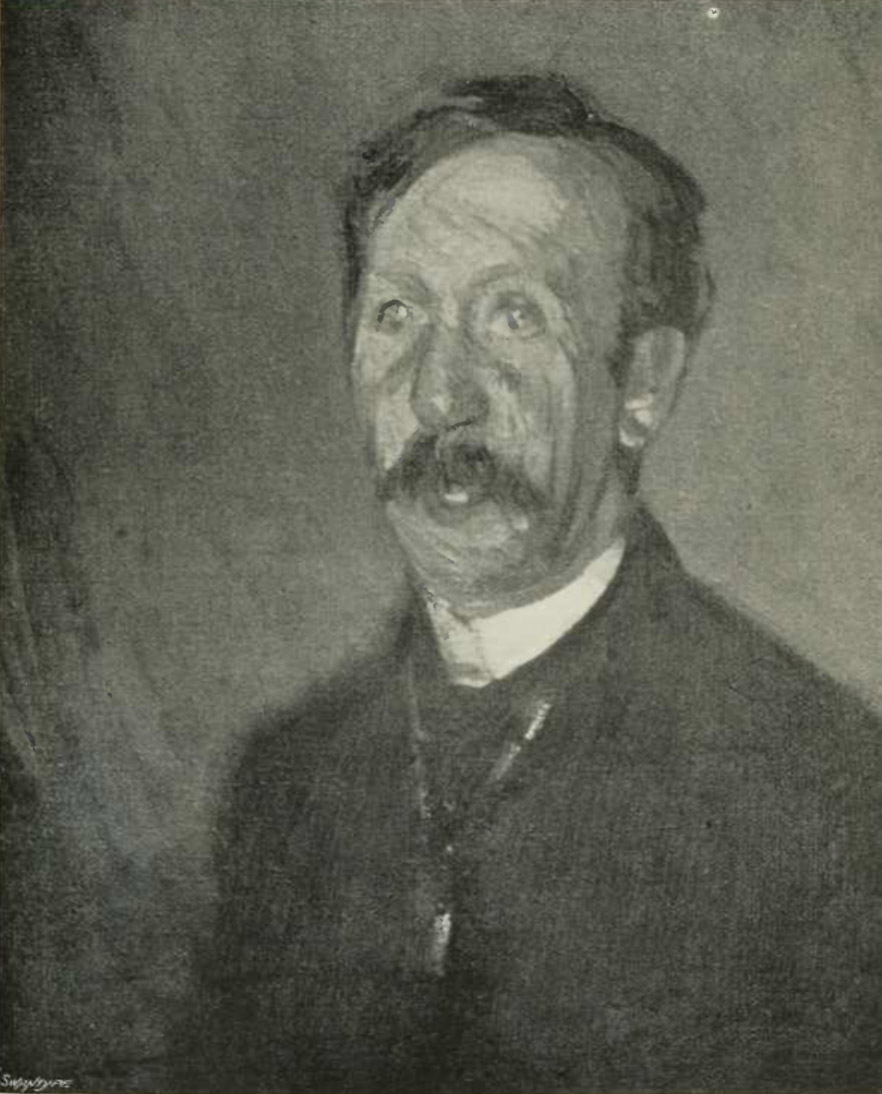

V. Portrait of Mr. George Moore

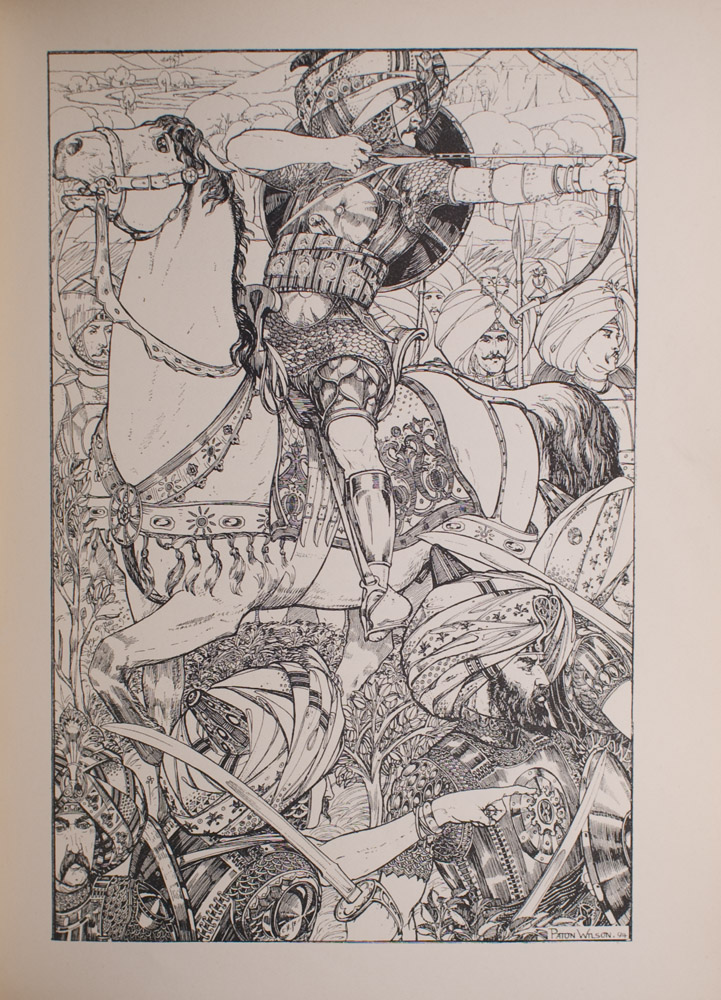

VI. Rustem Firing the First Shot Patten Wilson . . 118

VII. A Westmorland Village . W. W. Russell . . 144

VIII. The

Knock-out . . A. S. Hartrick . . 152

IX. Design for a Fan . . Charles Conder . . 191

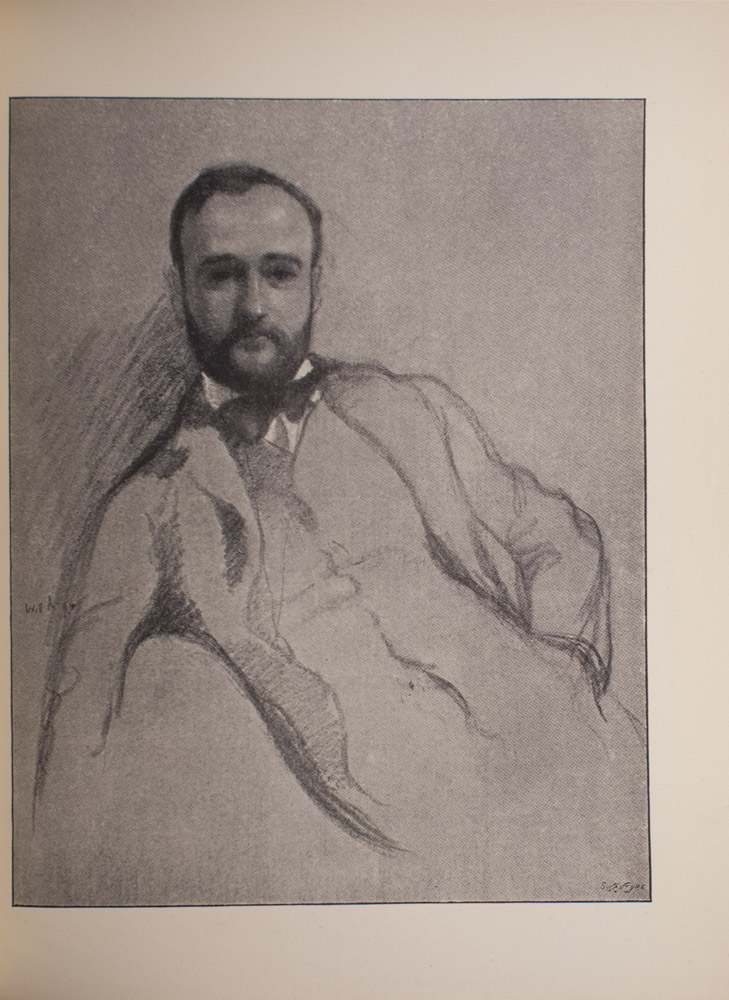

X. Bodley

Heads. No. 2 : Mr. John Davidson Will Rothenstein 203

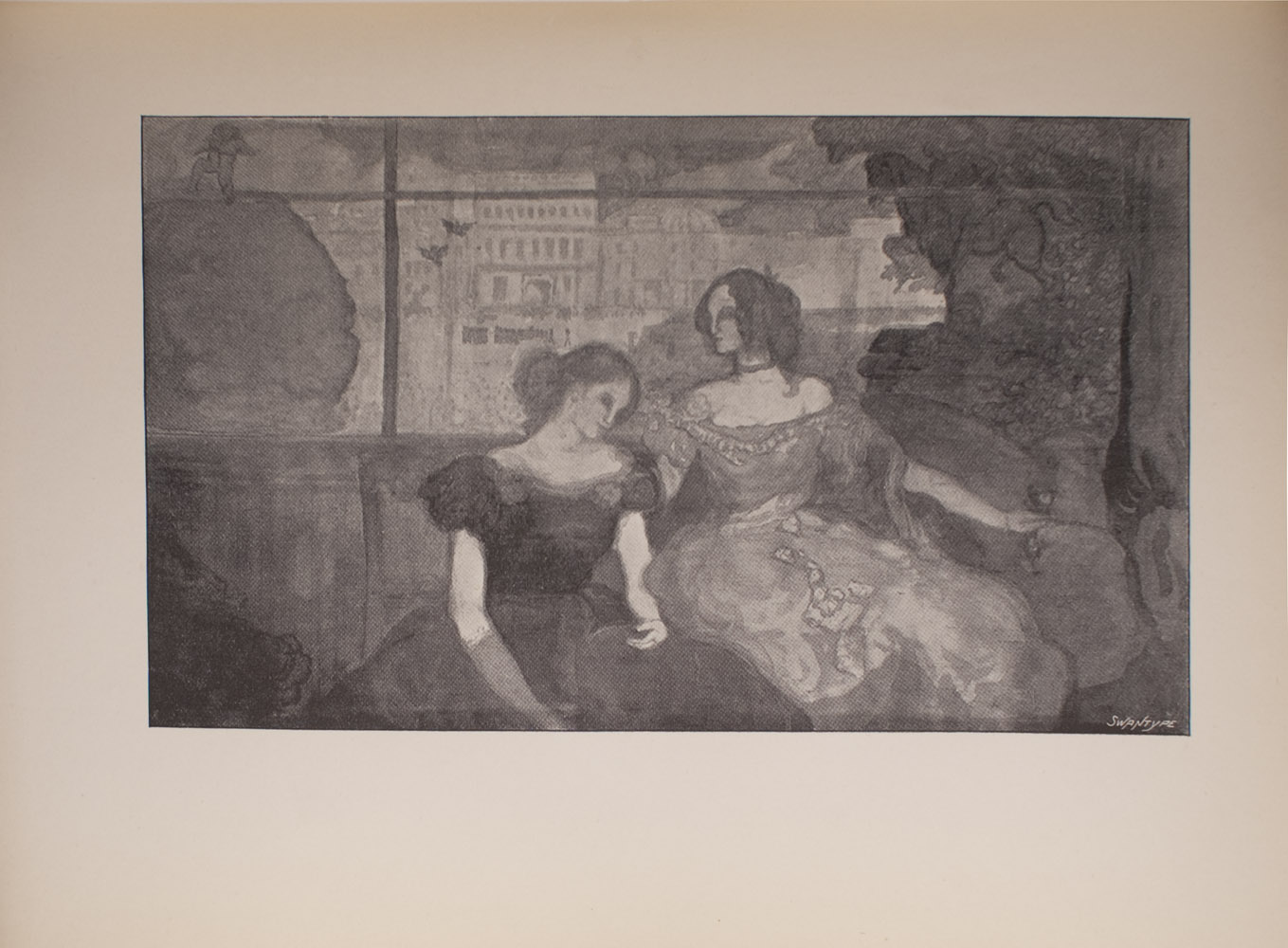

XI. Plein Air . . . Miss

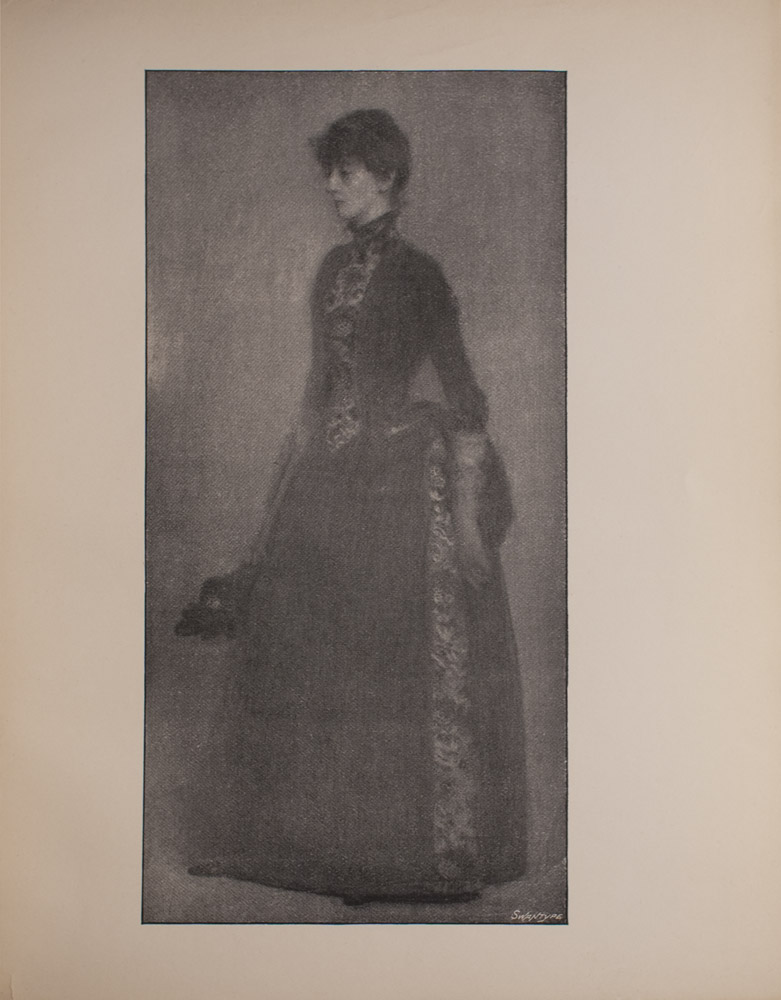

Sumner 235

XII. A Lady in Grey

. P. Wilson Steer 249

XIII. Portrait of Emil Sauer

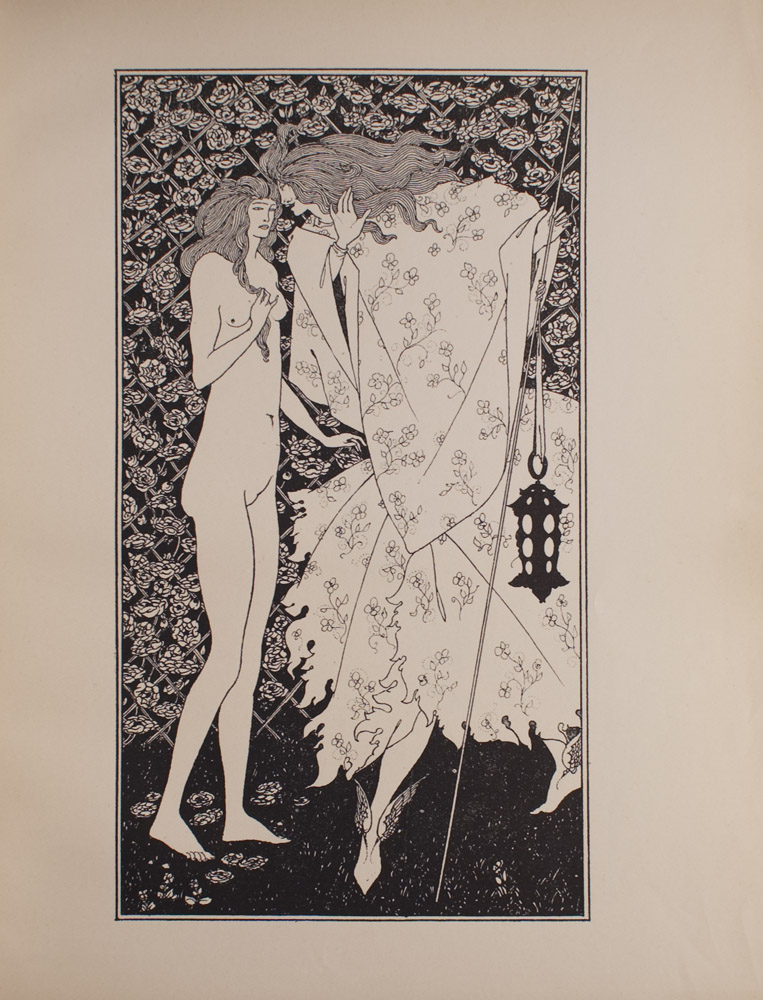

XIV. The Mysterious Rose Garden Aubrey

Beardsley . . 273

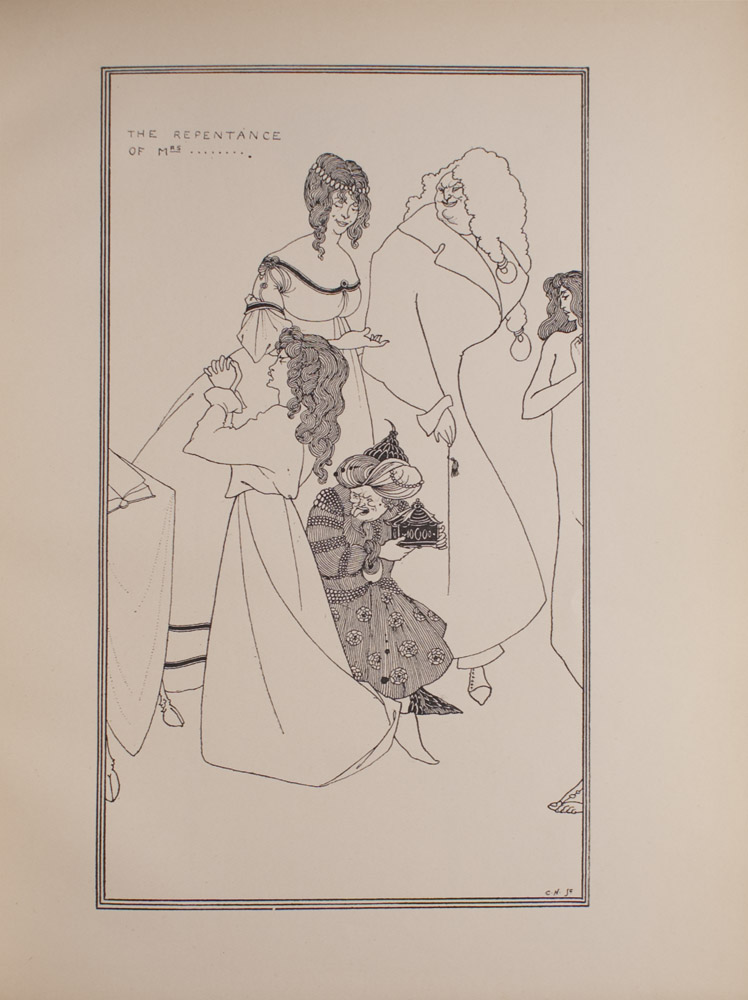

XV. The

Repentance of Mrs. ****

XVI. Portrait of Miss Wini-fred

Emery

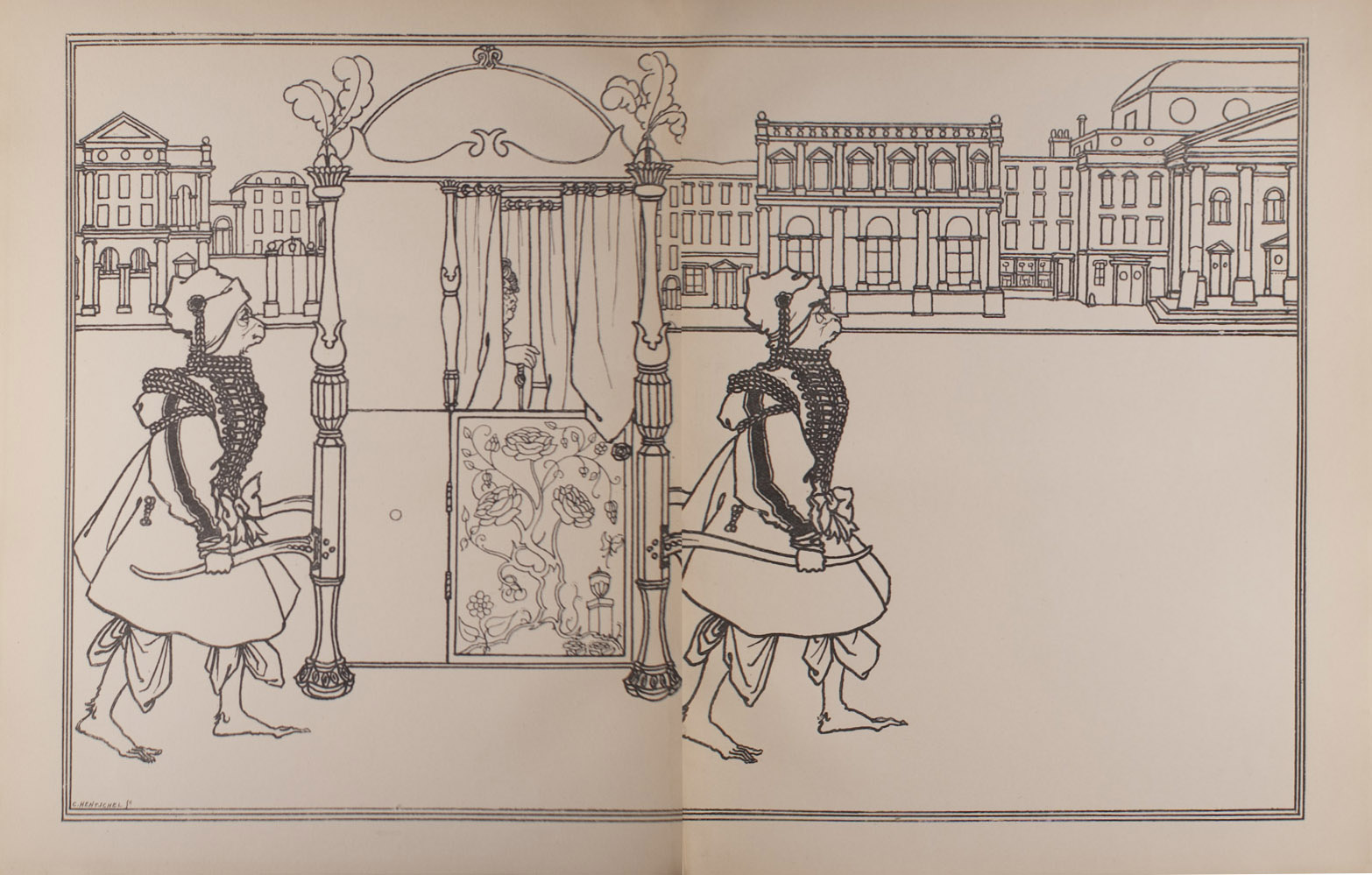

XVII. Double-page Supple-ment :

Frontispiece for

Juvenal

Back Cover, by Aubrey Beardsley

Advertisements

Home . . .

” WE’RE going home ! ” I heard two lovers say,

They kissed their friends and bade them bright

good-byes ;

I hid the deadly hunger in my eyes,

And, lest I might have killed them, turned away.

Ah, love, we too once gambolled home as they,

Home from the town with such fair merchandise,—

Wine and great grapes—the happy lover buys :

A little cosy feast to crown the day.

Yes ! we had once a heaven we called a home,

Its empty rooms still haunt me like thine eyes

When the last sunset softly faded there ;

Each day I tread each empty haunted room,

And now and then a little baby cries,

Or laughs a lovely laughter worse to bear.

“Tell me not Now”

By William Watson

TELL me not now, if love for love

Thou canst return,

Now while around us and above

Day’s flambeaux burn.

Not in clear noon, with speech as clear,

Thy heart avow,

For every gossip wind to hear ;

Tell me not now !

Tell me not now the tidings sweet,

The news divine ;

A little longer at thy feet

Leave me to pine.

I would not have the gadding bird

Hear from his bough ;

Nay, though I famish for a word,

Tell me not now !

The Yellow Book—Vol. III. B

But

But when deep trances of delight

All Nature seal ;

When round the world the arms of Night

Caressing steal ;

When rose to dreaming rose says, “Dear,

Dearest ;” and when

Heaven sighs her secret in Earth’s ear,

Ah, tell me then !

The Bohemian Girl

I

I WOKE up very gradually this morning, and it took me a little

while to

bethink myself where I had slept—that it had not

been in my own room

in the Cromwell Road. I lay a-bed, with

eyes half-closed, drowsily looking

forward to the usual procession

of sober-hued London hours, and, for the

moment, quite forgot

the journey of yesterday, and how it had left me in

Paris, a guest

in the smart new house of my old friend, Nina Childe.

Indeed,

it was not until somebody tapped on my door, and I roused

myself to call out, ” Come in,” that I noticed the strangeness of

the

wall-paper, and then, after an instant of perplexity, suddenly

remembered.

Oh, with a wonderful lightening of the spirit, I can

tell you.

A white-capped, brisk young woman, with a fresh-coloured,

wholesome peasant

face, came in, bearing a tray—Jeanne, Nina’s

femme-de-chambre

” Bonjour, monsieur,” she cried cheerily. ” I bring monsieur

his coffee.”

And her announcement was followed by a fragrance

—the softly-sung

response of the coffee-sprite. Her tray, with its

pretty freight of silver

and linen, primrose butter, and gently-

browned

browned pain-de-gruau, she set down on the table at my elbow ;

then she

crossed the room and drew back the window-curtains,

making the rings tinkle

crisply on the metal rods, and letting in a

gush of dazzling sunshine. From

where I lay I could see the

house-fronts opposite glow pearly-grey in

shadow, and the crest of

the slate roofs sharply print itself on the sky,

like a black line on

a sheet of scintillant blue velvet. Yet, a few minutes

ago, I had

been fancying myself in the Cromwell Road.

Jeanne, gathering up my scattered garments, to take them off

and brush them,

inquired, by the way, if monsieur had passed a

comfortable night.

” As the chambermaid makes your bed, so must you lie in it,”

I answered. ”

And you know whether my bed was smoothly made.”

Jeanne smiled indulgently. But her next remark—did it imply

that she

found me rusty ? ” Here’s a long time that you haven’t

been in Paris.”

” Yes,” I admitted ; ” not since May, and now we’re in

November.”

” We have changed things a little, have we not? ” she de-

manded, with a

gesture that left the room, and included the house,

the street, the

quarter.

” In effect,” assented I.

” Monsieur desires his hot water? ” she asked, abruptly irre-

levant.

But I could be, or at least seem, abruptly irrelevant too.

”

Mademoiselle—is she up ? ”

” Ah, yes, monsieur. Mademoiselle has been up since eight.

She awaits you in

the salon. La voilà qui joue,” she added, point-

ing to the floor.

Nina had begun to play scales in the room below.

” Then you may bring me my hot water,” I said.

The

The scales continued while I was dressing, and many desultory

reminiscences

of the player, and vague reflections upon the unlike-

lihood of her

adventures, went flitting through my mind to their

rhythm. Here she was,

scarcely turned thirty, beautiful, brilliant,

rich in her own right, as

free in all respects to follow her own will

as any man could be, with

Camille happily at her side, a well-

grown, rosy, merry miss of

twelve,—here was Nina, thus, to-day ;

and yet, a mere little ten

years ago, I remembered her …. ah,

in a very different plight indeed.

True, she has got no more than

her deserts ; she has paid for her success,

every pennyweight of it,

in hard work and self-denial. But one is so

expectant, here below,

to see Fortune capricious, that, when for once in a

way she

bestows her favours where they are merited, one can’t help

feeling

rather dazed. One is so inured to seeing honest Effort turn

empty-handed from her door.

Ten little years ago—but no. I must begin further back. I

must tell

you something about Nina’s father.

He was an Englishman who lived for the greater part of his life

in Paris. I

would say he was a painter, if he had not been equally

a sculptor, a

musician, an architect, a writer of verse, and a

university coach. A doer

of so many things is inevitably suspect ;

you will imagine that he must

have bungled them all. On the

contrary,

contrary, whatever he did, he did with a considerable degree of

accomplishment. The landscapes he painted were very fresh and

pleasing,

delicately coloured, with lots of air in them, and a

dreamy, suggestive

sentiment. His brother sculptors declared

that his statuettes were modelled

with exceeding dash and direct-

ness ; they were certainly fanciful and

amusing. I remember one

that I used to like immensely—Titania

driving to a tryst with

Bottom, her chariot a lily, daisies for wheels, and

for steeds a pair

of mettlesome field-mice. I doubt if he ever got a

commission

for a complete house ; but the staircases he designed, the

fire-

places, and other bits of buildings, everybody thought original

and

graceful. The tunes he wrote were lively and catching, the words

never stupid, sometimes even strikingly happy, epigrammatic ; and

he sang

them delightfully, in a robust, hearty baritone. He

coached the youth of

France, for their examinations, in Latin and

Greek, in history,

mathematics, general literature—in goodness

knows what not ; and his

pupils failed so rarely that, when one

did, the circumstance became a nine

days’ wonder. The world

beyond the Students’ Quarter had never heard of

him, but there

he was a celebrity and a favourite ; and, strangely enough

for a

man with so many strings to his bow, he contrived to pick up a

sufficient living.

He was a splendid creature to look at, tall, stalwart, full-

blooded, with a

ruddy open-air complexion ; a fine bold brow and

nose ; brown eyes,

humorous, intelligent, kindly, that always

brightened flatteringly when

they met you ; and a vast quantity

of bluish-grey hair and beard. In his

dress he affected (very

wisely, for they became him excellently) velvet

jackets, flannel

shirts, loosely-knotted ties, and wide-brimmed soft felt

hats.

Marching down the Boulevard St. Michel, his broad shoulders

well

thrown back, his head erect, chin high in air, his whole

person

person radiating health, power, contentment, and the pride of

them : he was

a sight worth seeing, spirited, picturesque, pre-

possessing. You could not

have passed him without noticing

him—without wondering who he was,

confident he was somebody

—without admiring him, and feeling that

there went a man it

would be interesting to know.

He was, indeed, charming to know ; he was the hero, the idol,

of a little

sect of worshippers, young fellows who loved nothing

better than to sit at

his feet. On the Rive Gauche, to be sure,

we are, for the most part, birds

of passage ; a student arrives,

tarries a little, then departs. So, with

the exits and entrances of

seniors and nouveaux,

the personnel of old Childe’s following varied

from season to season ; but

numerically it remained pretty much

the same. He had a studio, with a few

living-rooms attached,

somewhere up in the fastnesses of Montparnasse,

though it was

seldom thither that one went to seek him. He received at his

café,

the Café Bleu—the Café Bleu which has since blown into

the

monster café of the Quarter, the noisiest, the rowdiest, the most

flamboyant. But I am writing (alas) of twelve, thirteen, fifteen

years ago

; in those days the Café Bleu consisted of a single

oblong room—with

a sanded floor, a dozen tables, and two

waiters, Eugène and

Hippolyte—where Madame Chanve, the

patronne, in lofty insulation behind her counter,

reigned, if you

please, but where Childe, her principal client, governed.

The

bottom of the shop, at any rate, was reserved exclusively to his

use. There he dined, wrote his letters, dispensed his hospitalities;

he had

his own piano there, if you can believe me, his foils and

boxing-gloves ;

from the absinthe hour till bed-time there was

his habitat, his den. And

woe to the passing stranger who, mis-

taking the Café Bleu for an ordinary

house of call, ventured,

during that consecrated period, to drop in.

Nothing would be

said,

said, nothing done ; we would not even trouble to stare at the

intruder. Yet

he would seldom stop to finish his consommation,

or he would bolt it. He

would feel something in the air ; he

would know he was out of place. He

would fidget a little, frown

a little, and get up meekly, and slink into

the street. Human

magnetism is such a subtle force. And Madame Chanve

didn’t

mind in the least ; she preferred a bird in the hand to a brace

in

the bush. From half a dozen to a score of us dined at her long

table every evening ; as many more drank her appetisers in the

afternoon,

and came again at night for grog or coffee. You see,

it was a sort of club,

a club of which Childe was at once the

chairman and the object. If we had

had a written constitution,

it must have begun : ” The purpose of this

association is the

enjoyment of the society of Alfred Childe.”

Ah, those afternoons, those dinners, those ambrosial nights !

If the weather

was kind, of course, we would begin our session on

the terrasse, sipping our vermouth, puffing our cigarettes, laugh-

ing our laughs, tossing hither and thither our light ball of gossip,

vaguely conscious of the perpetual ebb and flow and murmur of

people in the

Boulevard, while the setting sun turned Paris to a

marvellous water-colour,

all pale lucent tints, amber and alabaster

and mother-of-pearl, with

amethystine shadows. Then, one by

one, those of us who were dining

elsewhere would slip away ;

and at a sign from Hippolyte the others would

move indoors,

and take their places down either side of the long narrow

table,

Childe at the head, his daughter Nina next him. And presently

with what a clatter of knives and forks, clinking of glasses, and

babble of

human voices, the Café Bleu would echo. Madame

Chanve’s kitchen was not a

thing to boast of, and her price, for

the Latin Quarter, was rather

high—I think we paid three francs,

wine included, which would be for

most of us distinctly a prix–

de-luxe.

de-luxe. But oh, it was such fun ; we were so young ;

Childe

was so delightful. The fun was best, of course, when we were

few, and could all sit up near to him, and none need lose a word.

When we

were many there would be something like a scramble

for good seats.

I ask myself whether, if I could hear him again to-day, I

should think his

talk as wondrous as I thought it then. Then I

could thrill at the verse of

Musset, and linger lovingly over the

prose of Théophile, I could laugh at

the wit of Gustave Droz,

and weep at the pathos …. it costs me a pang to

own it, but

yes, I m afraid …. I could weep at the pathos of Henry

Mürger ; and these have all suffered such a sad sea-change since.

So I

could sit, hour after hour, in a sort of ecstasy, listening to

the talk of

Nina’s father. It flowed from him like wine from a

full measure, easily,

smoothly, abundantly. He had a ripe,

genial voice, and an enunciation that

made crystals of his words ;

whilst his range of subjects was as wide as

the earth and the sky.

He would talk to you of God and man, of metaphysics,

ethics, the

last new play, murder, or change of ministry ; of books,

of

pictures, specifically, or of the general principles of literature

and

painting ; of people, of sunsets, of Italy, of the high seas, of

the

Paris streets—of what, in fine, you pleased. Or he would

spin

you yarns, sober, farcical, veridical, or invented. And, with

transitions infinitely rapid, he would be serious, jocose—solemn,

ribald—earnest, flippant—logical, whimsical, turn and turn

about.

And in every sentence, in its form or in its substance, he

would

wrap a surprise for you—it was the unexpected word, the

un-

expected assertion, sentiment, conclusion, that constantly

arrived.

Meanwhile it would enhance your enjoyment mightily to watch

his physiognomy, the movements of his great, grey, shaggy head,

the

lightening and darkening of his eyes, his smile, his frown,

his

his occasional slight shrug or gesture. But the oddest thing was

this, that

he could take as well as give ; he could listen—surely a

rare talent

in a monologist. Indeed, I have never known a man

who could make you feel so interesting.

After dinner he would light an immense brown meerschaum

pipe, and smoke for

a quarter-hour or so in silence ; then he

would play a game or two of chess

with some one ; and by and by

he would open his piano, and sing to us till

midnight.

I speak of him as old, and indeed we always called him Old

Childe among

ourselves ; yet he was barely fifty. Nina, when I

first made their

acquaintance, must have been a girl of sixteen or

seventeen ;

though—tall, with an amply rounded, mature-seeming

figure—if

one had judged from her appearance, one would have

fancied her three or

four years older. For that matter, she looked

then very much as she looks

now ; I can perceive scarcely any

alteration. She had the same dark hair,

gathered up in a big

smooth knot behind, and breaking into a tumult of

little ringlets

over her forehead ; the same clear, sensitive complexion ;

the

same rather large, full-lipped mouth, tip-tilted nose, soft chin,

and

merry, mischievous eyes. She moved in the same way, with the

same

leisurely, almost lazy grace, that could, however, on

occasions, quicken to

an alert, elastic vivacity ; she had the same

voice, a trifle deeper than

most women’s, and of a quality never so

delicately nasal, which made it

racy and characteristic ; the same

fresh, ready laughter. There was

something arch, something a

little sceptical, a little quizzical, in her

expression, as if, perhaps,

she

The Yellow Book—Vol. IV. B

she were disposed to take the world, more or less, with a grain of

salt ; at

the same time there was something rich, warm-blooded,

luxurious, suggesting

that she would know how to savour its

pleasantnesses with complete

enjoyment. But if you felt that she

was by way of being the least bit

satirical in her view of things,

you felt too that she was altogether

good-natured, and even that,

at need, she could show herself spontaneously

kind, generous,

devoted. And if you inferred that her temperament

inclined

rather towards the sensuous than the ascetic, believe me, it did

not

lessen her attractiveness.

At the time of which I am writing now, the sentiment that

reigned between

Nina and Old Childe’s retinue of young men

was chiefly an esprit-de-corps. Later on we all fell in love with

her ; but for the present we were simply amiably fraternal. We

were united

to her by a common enthusiasm ; we were fellow-

celebrants at her ancestral

altar—or, rather, she was the high

priestess there, we were her

acolytes. For, with her, filial piety

did in very truth partake of the

nature of religion ; she really,

literally, idolised her father. One only

needed to watch her for

three minutes, as she sat beside him, to understand

the depth and

ardour of her emotion : how she adored him, how she

admired

him and believed in him, how proud of him she was, how she

rejoiced in him. ” Oh, you think you know my father,” I

remember her saying

to us once. ” Nobody knows him. No-

body is great enough to know him. If

people knew him they

would fall down and kiss the ground he walks on.” It

is certain

she deemed him the wisest, the noblest, the handsomest, the

most

gifted, of human kind. That little gleam of mockery in her eye

died out instantly when she looked at him, when she spoke of him

or

listened to him ; instead, there came a tender light of love and

her face

grew pale with the fervour of her affection. Yet, when

he

he jested, no one laughed more promptly or more heartily than

she. In those

days I was perpetually trying to write fiction ; and

Old Childe was my

inveterate hero. I forget in how many

ineffectual manuscripts, under what

various dread disguises, he

was afterwards reduced to ashes ; I am afraid,

in one case, a

scandalous distortion of him got abroad in print. Publishers

are

sometimes ill-advised ; and thus the indiscretions of our youth

may

become the confusions of our age. The thing was in three

volumes,

and called itself a novel ; and of course the fatuous

author had to make a

bad business worse by presenting a copy to

his victim. I shall never forget

the look Nina gave me when I

asked her if she had read it ; I grow hot even

now as I recall it.

I had waited and waited, expecting her compliments ;

and at last

I could wait no longer, and so asked her ; and she answered

me

with a look ! It was weeks, I am not sure it wasn’t months,

before

she took me back to her good graces. But Old Childe

was magnanimous ; he

sent me a little pencil-drawing of his

head, inscribed in the corner, ” To

Frankenstein from his

Monster.”

It was a queer life for a girl to live, that happy-go-lucky life of

the

Latin Quarter, lawless and unpremeditated, with a café for her

school-room,

and none but men for comrades ; but Nina liked it ;

and her father had a

theory in his madness. He was a Bohemian,

not in practice only, but in

principle ; he preached Bohemianism

as the most rational manner of

existence, maintaining that it

developed what was intrinsic and authentic

in one’s character,

saved one from the artificial, and brought one into

immediate

contact

contact with the realities of the world ; and he protested he could

see no

reason why a human being should be ” cloistered and

contracted ” because of

her sex. ” What would not hurt my son,

if I had one, will not hurt my

daughter. It will make a man of

her—without making her the less a

woman.” So he took her

with him to the Café Bleu, and talked in her

presence quite as

freely as he might have talked had she been absent. As,

in the

greater number of his theological, political, and social

convictions,

he was exceedingly unorthodox, she heard a good deal, no

doubt,

that most of us would scarcely consider edifying for our

daughters’

ears ; but he had his system, he knew what he was about. ”

The

question whether you can touch pitch and remain undefiled,” he

said, ” depends altogether upon the spirit in which you approach

it. The

realities of the world, the realities of life, the real things

of God’s

universe—what have we eyes for, if not to envisage

them ? Do so

fearlessly, honestly, with a clean heart, and, man

or woman, you can only

be the better for it.” Perhaps his

system was a shade too simple, a shade

too obvious, for this

complicated planet ; but he held to it in all

sincerity. It was in

pursuance of the same system, I daresay, that he

taught Nina to

fence, and to read Latin and Greek, as well as to play the

piano,

and turn an omelette. She could ply a foil against the best

of

us.

And then, quite suddenly, he died.

I think it was in March, or April ; anyhow, it was a premature

spring-like

day, and he had left off his overcoat. That evening

he went to the Odéon,

and when, after the play, he joined us for

supper at the Bleu, he said he

thought he had caught a cold, and

ordered hot grog. The next day he did not

turn up at all ; so

several of us, after dinner, presented ourselves at his

lodgings in

Montparnasse. We found him in bed, with Nina reading to

him.

He

He was feverish, and Nina had insisted that he should stop at

home. He would

be all right to-morrow. He scoffed at our

suggestion that he should see a

doctor ; he was one of those men

who affect to despise the medical

profession. But early on the

following morning a commissionnaire brought me

a note from

Nina. ” My father is very much worse. Can you come at

once

? ” He was delirious. Poor Nina, white, with frightened

eyes, moved about

like one distracted. We sent off for Dr.

Rénoult, we had in a Sister of

Charity. Everything that could

be done was done. Till the very end, none of

us for a moment

doubted he would recover. It was impossible to conceive

that

that strong, affirmative life could be extinguished. And even

after the end had come, the end with its ugly suite of material

circumstances, I don’t think any of us realised what it meant. It

was as if

we had been told that one of the forces of Nature had

become inoperative.

And Nina, through it all, was like some

pale thing in marble, that breathed

and moved : white, dazed,

helpless, with aching, incredulous eyes,

suffering everything,

understanding nothing.

When it came to the worst of the dreadful necessary businesses

that

followed, some of us, somehow, managed to draw her from

the death-chamber

into another room, and to keep her there,

while others of us got it over.

It was snowing that afternoon, I

remember, a melancholy, hesitating

snowstorm, with large moist

flakes, that fluttered down irresolutely, and

presently disintegrated

into rain ; but we had not far to go. Then we

returned to Nina,

and for many days and nights we never dared to leave her.

You

will guess whether the question of her future, especially of her

immediate future, weighed heavily upon our minds. In the end,

however, it

appeared to have solved itself—though I can’t pretend

that the

solution was exactly all we could have wished.

Her

Her father had a half-brother (we learned this from his papers),

incumbent

of rather an important living in the north of England.

We also learned that

the brothers had scarcely seen each other

twice in a score of years, and

had kept up only the most fitful

correspondence. Nevertheless, we wrote to

the clergyman, de-

scribing the sad case of his niece ; and in reply we got

a letter,

addressed to Nina herself, saying that of course she must come

at

once to Yorkshire, and consider the rectory her home. I don’t

need

to recount the difficulties we had in explaining to her, in

persuading her.

I have known few more painful moments than

that when, at the Gare du Nord,

half a dozen of us established

the poor, benumbed, bewildered child in her

compartment, and

sent her, with our godspeed, alone upon her long

journey— to her

strange kindred, and the strange conditions of life

she would have

to encounter among them. From the Café Bleu to a

Yorkshire

parsonage ! And Nina’s was not by any means a neutral

personality, nor her mind a blank sheet of paper. She had a will

of her own

; she had convictions, aspirations, traditions, prejudices,

which she would

hold to with enthusiasm because they had been

her father’s, because her

father had taught them to her ; and she

had manners, habits, tastes. She

would be sure to horrify the

people she was going to ; she would be sure to

resent their criti-

cism, their slightest attempt at interference. Oh, my

heart was

full of misgivings ; yet—she had no money, she was

eighteen

years old—what else could we advise her to do ? All the

same,

her face, as it looked down upon us from the window of her rail-

way carriage, white, with big terrified eyes fixed in a gaze of

blank

uncomprehending anguish, kept rising up to reproach me

for weeks

afterwards. I had her on my conscience as if I had

personally wronged

her.

It

It was characteristic of her that, during her absence, she hardly

wrote to

us. She is of far too hasty and impetuous a nature to

take kindly to the

task of letter-writing ; her moods are too incon-

stant ; her thoughts, her

fancies, supersede one another too

rapidly. Anyhow, beyond the telegram we

had made her promise

to send, announcing her safe arrival, the most

favoured of us got

nothing more than an occasional scrappy note, if he got

so much ;

while the greater number of the long epistles some of us felt

in

duty bound to address to her, elicited not even the semblance of an

acknowledgment. Hence, about the particulars of her experience

we were

quite in the dark, though of its general features we were

informed,

succinctly, in a big, dashing, uncompromising hand,

that she ” hated ”

them.

I am not sure whether it was late in April or early in May that

Nina left

us. But one day towards the middle of October, coming

home from the

restaurant where I had lunched, I found in my

letter-box in the concierge’s

room two half-sheets of paper, folded,

with the corners turned down, and my

name superscribed in pencil.

The handwriting startled me a

little—and yet, no, it was im-

possible. Then I hastened to unfold

and read, and of course it

was the impossible which had happened.

” Mon cher, I am sorry not to find you at home, but I’ll wait at

the café at

the corner till half-past twelve. It is now midi juste.”

That

That was the first. The second ran : ” I have waited till a

quarter to one.

Now I am going to the Bleu for luncheon. I

shall be there till three.” And

each was signed with the initials,

N. C.

It was not yet two, so I had plenty of time. But you will

believe that I

didn’t loiter on that account. I dashed out of the

loge—into the street—down the Boulevard

St. Michel—into the

Bleu, breathlessly. At the far end Nina was

seated before a marble

table, with Madame Chanve in smiles and tears beside

her. I heard a

little cry ; I felt myself seized and enveloped for a moment

by some-

thing like a whirlwind—oh, but a very pleasant whirlwind,

warm and

fresh, and fragrant of violets ; I received two vigorous kisses,

one on

either cheek ; and then I was held off at arm’s length, and

examined

by a pair of laughing eyes.

And at last a voice—rather a deep voice for a woman’s, with just

a

crisp edge to it, that might have been called slightly nasal, but

was

agreeable and individual—a voice said : ” En voilà assez.

Come and

sit down.”

She had finished her luncheon, and was taking coffee ; and if

the whole

truth must be told, I’m afraid she was taking it with a

petit-verre and a cigarette. She wore an exceedingly

simple black

frock, with a bunch of violets in her breast, and a hat with

a

sweeping black feather and a daring brim. Her dark luxurious

hair

broke into a riot of fluffy little curls about her forehead, and

thence

waved richly away to where it was massed behind ; her

cheeks glowed with a

lovely colour (thanks, doubtless, to Yorkshire

breezes ; sweet are the uses

of adversity) ; her eyes sparkled ; her

lips curved in a perpetual play of

smiles, letting her delicate little

teeth show themselves furtively ; and

suddenly I realised that this

girl, whom I had never thought of save as one

might think of

one’s younger sister, suddenly I realised that she was a

woman,

and

and a radiantly, perhaps even a dangerously handsome woman. I

saw suddenly

that she was not merely an attribute, an aspect of

another, not merely

Alfred Childe’s daughter ; she was a person-

age in herself, a personage to

be reckoned with.

This sufficiently obvious perception came upon me with such

force, and

brought me such emotion, that I dare say for a little

while I sat vacantly

staring at her, with an air of preoccupation.

Anyhow, all at once she

laughed, and cried out, ” Well, when you

get back . . . ? ” and, ”

Perhaps,” she questioned, ” perhaps you

think it polite to go off

wool-gathering like that ? ” Whereupon

I recovered myself with a start, and

laughed too.

” But say that you are surprised, say that you are glad, at least,”

she went

on.

Surprised! glad! But what did it mean? What was it all

about ?

” I couldn’t stand it any longer, that’s all. I have come home.

Oh, que

c’est bon, que c’est bon, que c’est bon ! ”

” And—England ?—Yorkshire ?—your people ? “

” Don’t speak of it. It was a bad dream. It is over. It

brings bad luck to

speak of bad dreams. I have forgotten it. I am

here—in

Paris—at home. Oh, que c’est bon ! ” And she smiled

blissfully

through eyes filled with tears.

Don’t tell me that happiness is an illusion. It is her habit, if

you will,

to flee before us and elude us ; but sometimes, sometimes

we catch up with

her, and can hold her for long moments warm

against our hearts.

” Oh, mon père ! It is enough—to be here, where he lived,

where he

worked, where he was happy,” Nina murmured afterwards.

She had arrived the night before ; she had taken a room in the

Hôtel

d’Espagne, in the Rue de Médicis, opposite the Luxem-

bourg Garden. I was

as yet the only member of the old set she

had

had looked up. Of course I knew where she had gone first

—but not to

cry—to kiss it—to place flowers on it. She

could not

cry—not now. She was too happy, happy, happy.

Oh, to be back in

Paris, her home, where she had lived with

him, where every stick and stone

was dear to her because of

him !

Then, glancing up at the clock, with an abrupt change of key,

” Mais allons

donc, paresseux !—You must take me to see the

camarades. You must

take me to see Chalks.”

And in the street she put her arm through mine, laughing and

saying, ” On

nous croira fiancés.” She did not walk, she tripped,

she all but danced

beside me, chattering joyously in alternate

French and English. ” I could

stop and kiss them all—the men,

the women, the very pavement. Oh,

Paris ! Oh, these good,

gay, kind Parisians ! Look at the sky ! look at the

view—down

that impasse—the sunlight and shadows on the

houses, the door-

ways, the people. Oh, the air! Oh, the smells! Oue c’est

bon

—que je suis contente ! Et dire que j’ai passé cinq mois,

mais

cinq grands mois, en Angleterre. Ah, veinard, you—you

don’t

know how you’re blessed.” Presently we found ourselves labour-

ing knee-deep in a wave of black pinafores, and Nina had plucked

her bunch

of violets from her breast, and was dropping them

amongst eager fingers and

rosy cherubic smiles. And it was con-

stantly, ” Tiens, there’s Madame

Chose in her kiosque. Bonjour,

madame. Vous allez toujours bien ? ” and ”

Oh, look ! old

Perronet standing before his shop in his shirt-sleeves,

exactly as he

has stood at this hour every day, winter or summer, these

ten

years. Bonjour, M’sieu Perronet.” And you may be sure that

the

kindly French Choses and Perronets returned her greetings

with beaming

faces. ” Ah, mademoiselle, que c’est bon de vous

revoir ainsi. Que vous

avez bonne mine!” ” It is so strange,”

she

she said, ” to find nothing changed. To think that everything

has gone on

quietly in the usual way. As if I hadn’t spent an

eternity in exile ! ” And

at the corner of one street, before a vast

flaunting ” bazaar,” with a

prodigality of tawdry Oriental wares

exhibited on the pavement, and little

black shopmen trailing like

beetles in and out amongst them, ” Oh,” she

cried, ” the ‘ Mecque

du Quartier ‘ ! To think that I could weep for joy at

seeing the

‘ Mecque du Quartier ‘ ! ”

By and by we plunged into a dark hallway, climbed a long,

unsavoury

corkscrew staircase, and knocked at a door. A gruff

voice having answered,

” ‘Trez!” we entered Chalks’s bare,

bleak, paint-smelling studio. He was

working (from a lay-figure)

with his back towards us ; and he went on

working for a minute

or two after our arrival, without speaking. Then he

demanded,

in a sort of grunt, ” Eh bien, qu’est ce que c’est ? ” always

with-

out pausing in his work or looking round. Nina gave two little

ahems, tense with suppressed mirth ; and slowly,

indifferently,

Chalks turned an absent-minded face in our direction. But,

next

instant, there was a shout—a rush—a confusion of forms

in the

middle of the floor—and I realised that I was not the only

one to

be honoured by a kiss and an embrace. ” Oh, you’re covering

me

with paint,” Nina protested suddenly ; and indeed he had

forgotten to drop

his brush and palette, and great dabs of colour

were clinging to her cloak.

While he was doing penance,

scrubbing the garment with rags soaked in

turpentine, he kept

shaking his head, and murmuring, from time to time, as

he

glanced up at her, ” Well, I ll be dumned.”

” It’s very nice and polite of you, Chalks,” she said, by and by,

” a very

graceful concession to my sex. But, if you think it

would relieve you once

for all, you have my full permission to

pronounce it —amned.”

Chalks

Chalks did no more work that afternoon ; and that evening

quite twenty of us

dined at Madame Chanve’s ; and it was almost

like old times.

” Oh, yes,” she explained to me afterwards, ” my uncle is a good

man. My

aunt and cousins are very good women. But for me,

to live with

them—pas possible, mon cher. Their thoughts were

not my thoughts, we

could not speak the same language. They

disapproved of me unutterably. They

suffered agonies, poor

things. Oh, they were very kind, very patient.

But—! My

gods were their devils. My father—my great, grand,

splendid

father— was ‘ poor Alfred,’ ‘ poor uncle Alfred.’ Que

voulez-

vous ? And then—the life, the society ! The

parishioners—the

people who came to tea—the houses where we

sometimes dined !

Are you interested in crops ? In the preservation of game

? In

the diseases of cattle ? Olàlà ! (C’est bien le cas de s’en

servir,

de cette expression-là.) Olàlà, làlà ! And then—have you

ever

been homesick ? Oh, I longed, I pined, for Paris, as one

suffocating would long, would die, for air. Enfin, I could not

stand it any

longer. They thought it wicked to smoke cigarettes.

My poor

aunt—when she smelt cigarette-smoke in my bed-room !

Oh, her face !

I had to sneak away, behind the shrubbery at the

end of the garden, for

stealthy whiffs. And it was impossible to

get French tobacco. At last I

took the bull by the horns, and

fled. It will have been a terrible shock

for them. But better

one good blow than endless little ones ; better a

lump-sum, than

instalments with interest.”

But what was she going to do ? How was she going to live ?

For,

For, after all, much as she loved Paris, she couldn’t subsist on its

air and

sunshine.

” Oh, never fear! I’ll manage somehow. I’ll not die of

hunger,” she said

confidently.

And, sure enough, she managed very well. She gave music

lessons to the

children of the Quarter, and English lessons to

clerks and shop-girls ; she

did a little translating ; she would pose

now and then for a painter

friend—she was the original, for

instance, of Norton’s ” Woman

Dancing,” which you know.

She even—thanks to the employment by

Chalks of what he called

his ” inflooence

“—she even contributed a weekly column of Paris

gossip to the Palladium, a newspaper published at Battle Creek,

Michigan, U.S.A., Chalks’s native town. ” Put in lots about

me, and talk as

if there were only two important centres of

civilisation on earth, Battle

Crick and Parus, and it’ll be a boom,”

Chalks said. We used to have great

fun, concocting those

columns of Paris gossip. Nina, indeed, held the pen

and cast a

deciding vote ; but we all collaborated. And we put in lots

about

Chalks—perhaps rather more than he had bargained for.

With

an irony (we trusted) too subtle to be suspected by the good

people of Battle Creek, we would introduce their illustrious fellow-

citizen, casually, between the Pope and the President of the

Republic ; we

would sketch him as he strolled in the Boulevard

arm-in-arm with Monsieur

Meissonier, as he dined with the Per-

petual Secretary of the French

Academy, or drank his bock in the

afternoon with the Grand Chancellor of

the Legion of Honour ;

we

we would compose solemn descriptive criticisms of his works,

which almost

made us die of laughing ; we would interview him

—at

length—about any subject ; we would give elaborate bulletins

of his

health, and brilliant pen-pictures of his toilets. Sometimes

we would

betroth him, marry him, divorce him ; sometimes,

when our muse impelled us

to a particularly daring flight, we

would insinuate, darkly, sorrowfully,

that perhaps the great man’s

morals—— But no ! We were

persuaded that rumour accused him

falsely. The story that he had been seen

dancing at Bullier’s

with the notorious Duchesse de Z—— was a

baseless fabrication.

Unprincipled ? Oh, we were nothing if not

unprincipled. And

our pleasure was so exquisite, and it worried our victim

so. ” I

suppose you think it’s funny, don’t you ? ” he used to ask, with

a

feint of superior scorn which put its fine flower to our hilarity.

”

Look out, or you’ll bust,” he would warn us, the only uncon-

vulsed member

present. ” By gum, you’re easily amused.” We

always wrote of him

respectfully as Mr. Charles K. Smith ; we

never faintly hinted at his

sobriquet. We would have rewarded

liberally, at that time, any one who

could have told us what the K

stood for. We yearned to unite the cryptic

word to his surname

by a hyphen ; the mere abstract notion of doing so

filled us with

fearful joy. Chalks was right, I dare say ; we were easily

amused.

And Nina, at these moments of literary frenzy—I can see

her

now : her head bent over the manuscript, her hair in some dis-

array, a spiral of cigarette-smoke winding ceilingward from

between the

fingers of her idle hand, her lips parted, her eyes

gleaming with

mischievous inspirations, her face pale with the

intensity of her glee. I

can see her as she would look up, eagerly,

to listen to somebody’s

suggestion, or as she would motion to us

to be silent, crying, ”

Attendez—I’ve got an idea.” Then her

pen would dash swiftly,

noisily, over her paper for a little, whilst

we

we all waited expectantly ; and at last she would lean back,

drawing a long

breath, and tossing the pen aside, to read her

paragraph out to us.

In a word, she managed very well, and by no means died of

hunger. She could

scarcely afford Madame Chanve’s three-franc

table d’hôte, it is true ; but

we could dine modestly at Leon’s,

over the way, and return the Bleu for

coffee,—though, it must

be added, that establishment no longer

enjoyed a monopoly of

our custom. We patronised it and the Vachette, the

Source, the

Ecoles, the Souris, indifferently. Or we would sometimes

spend

our evenings in Nina’s rooms. She lived in a tremendously

swagger house in the Avenue de l’Observatoire—on the sixth

floor, to

be sure, but ” there was a carpet all the way up.” She

had a charming

little salon, with her own furniture and piano

(the same that had formerly

embellished our café), and no end

of books, pictures, draperies, and pretty

things, inherited from

her father or presented by her friends.

By this time the inevitable had happened, and we were all in

love with

her—hopelessly, resignedly so, and without internecine

rancour, for

she treated us, indiscriminately, with a serene, im-

partial, tolerant

derision ; but we were savagely, luridly, jealous

and suspicious of all

new-comers and of all outsiders. If we could

not

win her, no one else should ; and we formed ourselves round

her in a ring

of fire. Oh, the maddening mock-sentimental,

mock-sympathetic face she

would pull, when one of us ventured

to sigh to her of his passion ! The way

she would lift her eye-

brows, and gaze at you with a travesty of pity,

shaking her head

pensively, and murmuring, ” Mon pauvre ami ! Only fancy !

“

And then how the imp, lurking in the corners of her eyes, with

only

the barest pretence of trying to conceal himself, would

suddenly leap forth

in a peal of laughter ! She had lately read

Mr. Howells’s

Mr. Howells’s ” Undiscovered Country,” and had adopted the

Shakers’

paraphrase for love : ” Feeling foolish.”—” Feeling pretty

foolish

to-day, air ye, gentlemen ? ” she inquired, mimicking the

dialect of

Chalks. ” Well, I guess you just ain’t feeling any

more foolish than you

look ! “—If she would but have taken us

seriously ! And the worst of

it was that we knew she was

anything but temperamentally cold. Chalks

formulated the

potentialities we divined in her, when he remarked,

regretfully,

wistfully, as he often did, ” She could love like Hell.”

Once,

in a reckless moment, he even went so far as to tell her this

point-

blank. ” Oh, naughty Chalks ! ” she remonstrated, shaking her

ringer at him. ” Do you think that’s a pretty word ? But—I

dare say

I could.”

” All the same, Lord help the man you marry,” Chalks con-

tinued

gloomily.

” Oh, I shall never marry,” Nina cried. ” Because, first, I

don’t approve of

matrimony as an institution. And then—as you

say—Lord help my

husband. I should be such an uncomfortable

wife. So capricious, and

flighty, and tantalising, and unsettling,

and disobedient, and exacting,

and everything. Oh, but a horrid

wife ! No, I shall never marry. Marriage

is quite too out-of-date.

I shan’t marry ; but, if I ever meet a man and

love him—ah ! “

She placed two fingers upon her lips, and kissed

them, and waved

the kiss to the skies.

This fragment of conversation passed in the Luxembourg

Garden ; and the

three or four of us by whom she was accom-

panied glared threateningly at

our mental image of that not-

impossible upstart whom she might some day

meet and love.

We were sure, of course, that he would be a beast ; we hated

him

not merely because he would have cut us out with her, but

because

he would be so distinctly our inferior, so hopelessly

unworthy

unworthy of her, so helplessly incapable of appreciating her. I

think we

conceived of him as tall, with drooping fair moustaches,

and contemptibly

meticulous in his dress. He would probably

not be of the Quarter ; he would

sneer at us.

” He’ll not understand her, he’ll not respect her. Take her

peculiar views.

We know where she gets them. But he—he’ll

despise her for them, at

the very time he’s profiting by ’em,”

some one said.

Her peculiar views of the institution of matrimony, the speaker

meant. She

had got them from her father. ” The relations of

the sexes should be as

free as friendship,” he had taught. ” If

a man and a woman love each other,

it is nobody’s business but

their own. Neither the Law nor Society can,

with any show

of justice, interfere. That they do interfere, is a survival

of

feudalism, a survival of the system under which the individual,

the

subject, had no liberty, no rights. If a man and a woman

love each other,

they should be as free to determine for themselves

the character, extent,

and duration of their intercourse, as two

friends should be. If they wish

to live together under the same

roof, let them. If they wish to retain

their separate domiciles, let

them. If they wish to cleave to each other

till death severs them

—if they wish to part on the morrow of their

union—let

them, by heaven. But the couple who go before a priest or

a

magistrate, and bind themselves in ceremonial marriage, are

serving

to perpetuate tyranny, are insulting the dignity of human

nature.” Such was

the gospel which Nina had absorbed (don’t,

for goodness’ sake, imagine that

I approve of it because I cite it),

and which she professed in entire good

faith. We felt that the

coming man would misapprehend both it and

her—though he

would not hesitate to make a convenience of it. Ugh,

the

cynic !

We

The Yellow Book—Vol. IV. c

We formed ourselves round her in a ring of fire, hoping to

frighten the

beast away. But we were miserably, fiercely

anxious, suspicious, jealous.

We were jealous of everything in

the shape of a man that came into any sort

of contact with her :

of the men who passed her in the street or rode with

her in the

omnibus ; of the little employés de

commerce to whom she gave

English lessons ; of everybody. I

fancy we were always more or

less uneasy in our minds when she was out of

our sight. Who could

tell what might be happening ? With those lips of

hers, those

eyes of hers—oh, we knew how she could love : Chalks had

said

it. Who could tell what might already have happened ? Who

could

tell that the coming man had not already come ? She was

entirely capable of

concealing him from us. Sometimes, in the

evening, she would seem absent,

preoccupied. How could we be

sure that she wasn’t thinking of him ?

Savouring anew the hours

she had passed with him that very day ? Or

dreaming of those

she had promised him for to-morrow ? If she took leave of

us—

might he not be waiting to join her round the corner ? If

she

spent an evening away from us…..

And she—she only laughed ; laughed at our jealousy, our fears,

our

precautions, as she laughed at our hankering flame. Not

a laugh that

reassured us, though ; an inscrutable, enigmatic

laugh, that might have

covered a multitude of sins. She had

taken to calling us collectively Loulou ” Ah, le pauv’ Loulou—

so now he has

the pretension to be jealous.” Then she would be

interrupted by a paroxysm

of laughter ; after which, ” Oh, qu’il

est drôle,” she would gasp. ” Pourvu

qu’il ne devienne pas

gênant ! ”

It was all very well to laugh ; but some of us, our personal

equation quite

apart, could not help feeling that the joke was of a

precarious quality,

that the situation held tragic possibilities. A

young

young and attractive girl, by no means constitutionally insus-

ceptible, and

imbued with heterodox ideas of marriage—alone in

the Latin Quarter.

I have heard it maintained that the man has yet to be born, who,

in his

heart of hearts, if he comes to think the matter over, won’t

find himself

at something of a loss to conceive why any given

woman should experience

the passion of love for any other man ;

that a woman’s choice, to all men

save the chosen, is, by its very

nature, as incomprehensible as the

postulates of Hegel. But, in

Nina’s case, even when I regard it from this

distance of time, I

still feel, as we all felt then, that the mystery was

more than

ordinarily obscure. We had fancied ourselves prepared for

any-

thing ; the only thing we weren’t prepared for was the thing that

befell. We had expected ” him ” to be offensive, and he wasn’t.

He was,

quite simply, insignificant. He was a South American,

a Brazilian, a member

of the School of Mines : a poor, undersized,

pale, spiritless, apologetic

creature, with rather a Teutonic-looking

name, Ernest Mayer. His father, or

uncle, was Minister of

Agriculture, or Commerce, or something, in his

native land ; and

he himself was attached in some nominal capacity to the

Brazilian

Legation, in the Rue de Téhéran, whence, on State occasions,

he

enjoyed the privilege of enveloping his meagre little person in a

very gorgeous diplomatic uniform. He was beardless, with vague

features,

timid light-blue eyes, and a bluish anæmic skin. In

manner he was nervous,

tremulous, deprecatory—perpetually

bowing, wriggling, stepping back

to let you pass, waving his

hands, palms outward, as if to protest against

giving you trouble.

And

And in speech—upon my word, I don’t think I ever heard him

compromise

himself by any more dangerous assertion than that

the weather was fine, or

he wished you good-day. For the most

part he listened mutely, with a

flickering, perfunctory smile.

From time to time, with an air of casting

fear behind him and

dashing into the imminent deadly breach, he would

hazard an

” Ah, oui,” or a ” Pas mal.” For the rest, he played the

piano

prettily enough, wrote colourless, correct French verse, and was

reputed to be an industrious if not a brilliant student—what we

called un sérieux.

It was hard to believe that beautiful, sumptuous Nina Childe,

with her wit,

her humour, her imagination, loved this neutral little

fellow ; yet she

made no secret of doing so. We tried to frame

a theory that would account

for it. ” It’s the maternal instinct,”

suggested one. ” It’s her chivalry,”

said another ; ” she’s the sort

of woman who could never be very violently

interested by a man

of her own size. She would need one she could look up

to, or

else one she could protect and pat on the head.” ” ‘God be

thanked, the meanest of His creatures boasts two soul-sides, one to

face

the world with, one to show a woman when he loves her,'”

quoted a third. ”

Perhaps Coco “—we had nicknamed him Coco

—” has luminous

qualities that we don’t dream of, to which he

gives the rein when they’re

à deux.”

Anyhow, if we were mortified that she should have preferred

such a one to

us, we were relieved to think that she hadn’t fallen

into the clutches of a

blackguard, as we had feared she would.

That Coco was a blackguard we never

guessed. We made the

best of him, because we had to choose between doing

that and

seeing less of Nina ; in time, I am afraid—such is the

influence

of habit—we rather got to like him, as one gets to like

any

innocuous, customary thing. And if we did not like the situation

—for

—for none of us, whatever may have been our practice, shared

Nina’s

hereditary theories anent the sexual conventions— we

recognised that

we couldn’t alter it, and we shrugged our shoulders

resignedly, trusting it

might be no worse.

And then, one day, she announced, ” Ernest and I are going to

be married.”

And when we cried out why, she explained that—

despite her own

conviction that marriage was a barbarous institu-

tion—she felt, in

the present state of public opinion, people owed

legitimacy to their

children. So Ernest, who, according to both

French and Brazilian law, could

not, at his age, marry without

his parents’ consent, was going home to

procure it. He would

sail next week ; he would be back before three months.

Ernest

sailed from Lisbon ; and the post, a day or two after he was

safe

at sea, brought Nina a letter from him. It was a wild,

hysterical,

remorseful letter, in which he called himself every sort of

name.

He said his parents would never dream of letting him marry her.

They were Catholics, they were very devout, they had prejudices,

they had

old-fashioned notions. Besides, he had been as good as

affianced to a lady

of their election ever since he was born. He

was going home to marry his

second cousin.

Shortly after the birth of Camille I had to go to London, and

it was nearly

a year before I came back to Paris. Nina was

looking better than when I had

left, but still in nowise like her

old self—pale and worn and

worried, with a smile that was the

ghost of her former one. She had been

waiting for my return,

she said, to have a long talk with me. ” I have made

a little plan.

I want

I want you to advise me. Of course you must advise me to stick

to it.”

And when we had reached her lodgings, and were alone in the

salon, ” It is

about Camille, it is about her bringing-up,” she

explained. ” The Latin

Quarter ? It is all very well for you,

for me ; but for a growing child ?

Oh, my case was different ;

I had my father. But Camille ? Restaurants,

cafés, studios, the

Boul’ Miche, and this little garret—do they form

a wholesome

environment ? Oh, no, no—I am not a renegade. I am

a

Bohemian ; I shall always be ; it is bred in the bone. But my

daughter—ought she not to have the opportunity, at least, of being

different, of being like other girls ? You see, I had my father ;

she will

have only me. And I distrust myself ; I have no

‘ system.’ Shall I not do

better, then, to adopt the system of the

world ? To give her the

conventional education, the conventional

‘ advantages ‘ ? A home, what they

call home influences.

Then, when she has grown up, she can choose for

herself.

Besides, there is the question of francs and centimes. I have

been able to earn a living for myself, it is true. But even that is

more

difficult now ; I can give less time to work ; I am in debt.

And we are two

; and our expenses must naturally increase from

year to year. And I should

like to be able to put something

aside. Hand-to-mouth is a bad principle

when you have a growing

child.”

After a little pause she went on : “So my problem is, first, how

to earn our

livelihood, and, secondly, how to make something like

a home for Camille,

something better than this tobacco-smoky,

absinthe-scented atmosphere of

the Latin Quarter. And I can

see only one way of accomplishing the two

things. You will

smile—but I have considered it from every point of

view. I have

examined myself, my own capabilities. I have weighed all

the

chances.

chances. I wish to take a flat, in another quarter of the town,

near the

Etoile or the Pare Monceau, and—open a pension. There

is my plan.”

I had a much simpler and pleasanter plan of my own, but of

that, as I knew,

she would hear nothing. I did not smile at hers,

however ; though I confess

it was not easy to imagine madcap

Nina in the rôle of a landlady,

regulating the accounts and pre-

siding at the table of a boarding-house. I

can’t pretend that I

believed there was the slightest likelihood of her

filling it with

success. But I said nothing to discourage her ; and the

fact that

she is rich to-day proves how little I divined the resources of

her

character. For the boarding-house she kept was an exceedingly

good

boarding-house ; she showed herself the most practical of

mistresses ; and

she prospered amazingly. Jeanselme, whose

father had recently died, leaving

him a fortune, lent her what

money she needed to begin with ; she took and

furnished a flat in

the Avenue de l’Alma ; and I—I feel quite like

an historical

personage when I remember that I was her first boarder.

Others

soon followed me, though, for she had friends amongst all the

peoples of the earth—English and Americans, Russians, Italians,

Austrians, even Roumanians and Servians, as well as French ;

and each did

what he could to help. At the end of a year she

overflowed into the flat

above ; then into that below ; then she

acquired the lease of the entire

house. She worked tremendously,

she was at it early and late, her eyes were

everywhere ; she set an

excellent table ; she employed admirable servants ;

and if her

prices were a bit stiff, she gave you your money’s worth,

and

there were no ” surprises.” It was comfortable and quiet ; the

street was bright, the neighbourhood convenient. You could

dine in the

common salle-à-manger if you liked, or in your

private sitting-room. And

you never saw your landlady except

for

for purposes of business. She lived apart, in the entresol, alone

with

Camille and her body-servant Jeanne. There was the

” home ” she had set out

to make.

Meanwhile another sort of success was steadily thrusting itself

upon

her—she certainly never went out of her way to seek it ; she

was

much too busy to do that. Such of her old friends as remained

in Paris came

frequently to see her, and new friends gathered

round her. She was

beautiful, she was intelligent, responsive,

entertaining. In her salon, on

a Friday evening, you would meet

half the lions that were at large in the

town—authors, painters,

actors, actresses, deputies, even an

occasional Cabinet minister.

Red ribbons and red rosettes shone from every

corner of the

room. She had become one of the oligarchs of la haute Bohème, she

had become one of the

celebrities of Paris. It would be tiresome

to count the novels, poems,

songs, that were dedicated to her, the

portraits of her, painted or

sculptured, that appeared at the

Mirlitons or the Palais de l’Industrie.

Numberless were the

partis who asked her to marry them (I know one, at

least, who

has returned to the charge again and again), but she only

laughed,

and vowed she would never marry. I don’t say that she has

never had her fancies, her experiences ; but she has consistently

scoffed

at marriage. At any rate, she has never affected the least

repentance for

what some people would call her ” fault.” Her

ideas of right and wrong have

undergone very little modification.

She was deceived in her estimate of the

character of Ernest Mayer,

if you please ; but she would indignantly deny

that there was

anything sinful, anything to be ashamed of, in her relations

with

him. And if, by reason of them, she at one time suffered a good

deal of pain, I am sure she accounts Camille an exceeding great

compensation. That Camille is her child she would scorn to

make a secret.

She has scorned to assume the conciliatory title

of

of Madame. As plain Mademoiselle, with a daughter, you must

take her or

leave her. And, somehow, all this has not seemed to

make the faintest

difference to her clientèle, not even to the

primmest of the English. I can’t think of one of them who

did not treat her

with deference, like her, and recommend

her house.

But her house they need recommend no more, for she has

sold it.

Last spring, when I was in Paris, she told me she was about to

do

so. ” Ouf ! I have lived with my nose to the grindstone long

enough. I am going to ‘retire.'” What money she had saved from

season to

season, she explained, she had entrusted to her friend

Baron C * * * * *

for speculation. ” He is a wizard, and so

I am a rich woman. I shall have

an income of something like

three thousand pounds, mon cher ! Oh, we will

roll in it. I have

had ten bad years—ten hateful years. You don’t

know how I

have hated it all, this business, this drudgery, this

cut-and-dried,

methodical existence—moi, enfant de Bohème ! But,

enfin, it was

obligatory. Now we will change all that. Nous reviendrons

à

nos premières amours. I shall have ten good years—ten years

of

barefaced pleasure. Then—I will range myself—perhaps.

There

is the darlingest little house for sale, a sort of châlet, built of

red

brick, with pointed windows and things, in the Rue de Lisbonne.

I

shall buy it—furnish it—decorate it. Oh, you will see. I

shall

have my carriage, I shall have toilets, I shall entertain, I

shall

give dinners—olàlà ! No more boarders, no more bores,

cares,

responsibilities. Only, my friends and—life! I feel like one

emerging from ten years in the galleys,

ten years of penal

servitude. To the Pension Childe—bonsoir ! ”

” That’s all very well for you,” her listener complained sombrely.

” But for

me ? Where shall I stop when I come to Paris ? ”

” With me. You shall be my guest. I will kill you if you

ever

ever go elsewhere. You shall pass your old age in a big chair in

the best

room, and Camille and I will nurse your gout and make

herb-tea for

you.”

” And I shall sit and think of what might have been.”

” Yes, we’ll indulge all your little foibles. You shall sit and

‘ feel

foolish ‘—from dawn to dewy eve.”

If you had chanced to be walking in the Bois-de-Boulogne this

afternoon, you

might have seen a smart little basket-phaeton flash

past, drawn by two

glossy bays, and driven by a woman—a

woman with sparkling eyes, a

lovely colour, great quantities of

soft dark hair, and a figure—

” Hélas, mon père, la taille d’une déesse “—

a smiling woman, in a wonderful blue-grey toilet, grey driving-

gloves, and

a bold-brimmed grey-felt hat with waving plumes.

And in the man beside her

you would have recognised your

servant. You would have thought me in great

luck, perhaps you

would have envied me. But—esse, quam videri !—I would I were

as enviable as I

looked.

Vespertilia

IN the late autumn’s dusky-golden prime,

When sickles gleam, and rusts the idle plough,

The time of apples dropping from the bough,

And yellow leaves on sycamore and lime.

O’er grassy uplands far above the sea

Often at twilight would my footsteps fare,

And oft I met a stranger-woman there

Who stayed and spake with me :

Hard by the ancient barrow smooth and green,

Whose rounded burg swells dark upon the sky

Lording it high o’er dusky dell and dene,

We wandered—she and I.

Ay, many a time as came the evening hour

And the red moon rose up behind the sheaves,

I found her straying by that barren bower,

Her fair face glimmering like a white wood-flower

That gleams through withered leaves :

Her mouth was redder than the pimpernel,

Her eyes seemed darker than the purple air

‘Neath brows half hidden—I remember well—

‘Mid mists of cloudy hair.

And

And all about her breast, around her head,

Was wound a wide veil shadowing cheek and chin,

Woven like the ancient grave-gear of the dead :

A twisted clasp and pin

Confined her long blue mantle’s heavy fold

Of splendid tissue dropping to decay,

Faded like some rich raiment worn of old,

With rents and tatters gaping to the day.

Her sandals, wrought about with threads of gold,

Scarce held together still, so worn were they,

Yet sewn with winking gems of green and blue,

Where pale as pearls her naked feet shone through.

And all her talk was of some outland rare,

Where myrtles blossom by the blue sea’s rim,

And life is ever good and sunny and fair ;

” Long since,” she sighed, ” I sought this island grey.

Here where the wind moans and the sun is dim,

When his beaked galleys cleft the ocean spray,

For love I followed him.”

Once, as we stood, we heard the nightingale

Pipe from a thicket on the sheer hillside,

Breathless she hearkened, still and marble-pale,

Then turned to me with strange eyes open wide—

” Now I remember ! …. Now I know ! ” said she,

” Love will be life …. ah, Love is Life ! ” she

cried,

” And thou—thou lovest me ? “

I took her chill hands gently in mine own,

” Dear, but no love is mine to give,” I said,

” My heart is colder than the granite stone

That

That guards my true-love in her grassy bed ;

My faith and troth are hers, and hers alone,

Are hers …. and she is dead.”

Weeping, she drew her veil about her face,

And faint her accents were and dull with pain ;

” Poor Vespertilia ! gone her days of grace,

Now doth she plead for love—and plead in vain :

None praise her beauty now, or woo her smile !

* * * * *

Ah, hadst thou loved me but a little while,

I might have lived again.

Then slowly as a wave along the shore

She glided from me to yon sullen mound ;

My frozen heart, relenting, smote me sore—

Too late—I searched the hollow slopes around,

Swiftly I followed her, but nothing found,

Nor saw nor heard her more.

And now, alas, my true-love’s memory

Even as a dream of night-time half-forgot,

Fades faint and far from me,

And all my thoughts are of the stranger still,

Yea, though I loved her not :

I loved her not—and yet—I fain would see,

Upon the wind-swept hill,

Her dark veil fluttering in the autumn breeze ;

Fain would I hear her changeful voice awhile,

Soft as the wind of spring-tide in the trees,

And watch her slow, sweet smile.

Ever

Ever the thought of her abides with me

Unceasing as the murmur of the sea ;

When the round moon is low and night-birds flit,

When sink the stubble-fires with smouldering flame,

Over and o’er the sea-wind sighs her name,

And the leaves whisper it.

” Poor Vespertilia,” sing the grasses sere,

” Poor Vespertilia,” moans the surf-beat shore

;

Almost I feel her very presence near—

Yet she comes nevermore.

The House of Shame

By H. B. Marriott Watson

THERE was no immediate response to his knock, and, ere he

rapped again, Farrell turned stupidly and took

in a vision of

the street. The morning sunshine streamed on Piccadilly

; a

snap of air shook the tree-tops in the Park ; and beyond, the

greensward sparkled with dew. The traffic roared along the road-

way,

but the cabs upon the stand rode like ships at anchor on a

windless

ocean. Below him flowed the tide of passengers. The dis-

passion of

that drifting scene affected him by contrast with his own

warm flood

of emotions ; the picture—the trees, the sunlight, and

the

roar—imprinted itself sharply upon his brain. His glance

flitted

among the faces, and wandered finally to the angle of the

crossway,

by which his cab was sauntering leisurely. With a shudder

he

wheeled face-about to the door, and raised the clapper. For a

moment yet he stood in hesitation. The current of his thoughts

ran

like a mill-race, and a hundred discomforting impressions

flowed

together. The house lay so quiet ; the sunlight struck the

window-panes with a lively and discordant glare. He put his

hand into

his pocket and withdrew a latchkey, twiddling it

restlessly between

his fingers. With a thrust and a twist the door

would slip softly

open, and he might enter unobserved. He

entertained the impulse but a

moment. He dared not enter in

that

The Yellow Book—Vol. IV. D

that nocturnal fashion ; he would prefer admittance publicly, in

the eye

of all, as one with nothing to conceal, with no black

shame upon him.

His return should be ordinary, matter-of-fact ;

he would choose that

Jackson should see him cool and unperturbed.

In some way, too, he

vaguely hoped to cajole his memory, and

to ensnare his willing mind

into a belief that nothing unusual had

happened.

He knocked with a loud clatter, feet sounded in the hall, and

the door

fell open. Jackson looked at him with no appearance

of surprise.

” Good morning, Jackson,” he said, kicking his feet against the

step. He

entered, and laid his umbrella in the stand. ” Is your

mistress up yet

? ” he asked.

” Yes, sir,” said the servant, placidly; ” she’s in the morning-

room,

sir, I think.”

There was no emotion in the man’s voice ; his face wore no

aspect of

suspicion or inquiry, and somehow Farrell felt already

relieved.

To-day was as yesterday, unmarked by any grave event.

” Ah ! ” he said, and passed down the hall. At the foot of the

stairs he

paused again, with a pretence of dusting something from