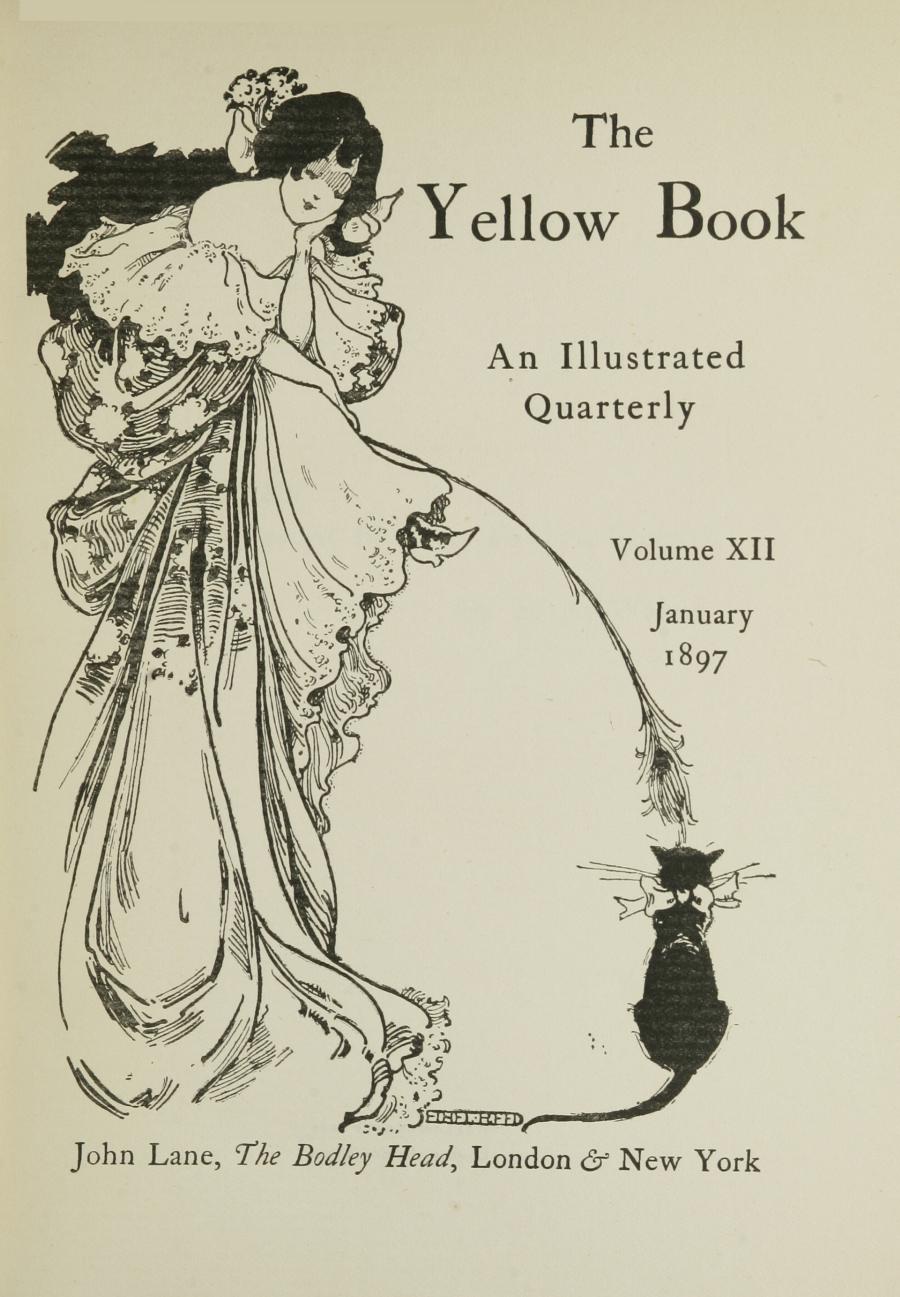

The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume XII January 1897

Contents

Literature

I. The Lost Eden . . By William

Watson . Page 11

II. She and He: Recent Documents Henry James . . . 15

III. My Note-Book in the Weald Menie Muriel Dowie . 39

IV. Flower o’ the Clove . Henry

Harland . . 65

V. The Ghost

Bereft . . E. Nesbit . . .110

VI. Three Reflections . . Stanley

V. Makower . 113

VII. Marcel : An Hotel

Child Lena Milman . . . 141

VIII. To Rollo . . . Kenneth

Grahame . . 165

IX. The Restless

River . Evelyn Sharp . . . 167

X. The Unka . . . Frank

Athelstane Swettenham, C.M.G. . . 191

XI. A Little Holiday . . Oswald

Sickert . . . 204

XII. St. Joseph and

Mary Marie Clothilde Balfour . 215

XIII. Alexander the Ratcatcher Richard Garnett, C.B., LL.D. . . .221

XIV. Natalie. . . . Renee de

Coutans . . 245

XV. The Burden of

Pity . A. Bernard Miall . . 248

XVI.

Far Above Rubies . .

Netta Syrett . . . 250

XVII. At the

Article of Death . John Buchan . . . 273

XVIII. Children of the Mist . Rosamund Marriott Watson 281

XIX. A Forgotten Novelist .

Hermione Ramsden . . 291

XX. A

Fire Stephen Phillips . . 306

XXI. At Twickenham . . Ella

D’Arcy . . .313

XXII. Two Prose

Fancies . Richard Le Gallienne . 333

The Yellow Book — Vol. XII. — January, 1897

Art

Art

I. Bodley Heads. No. 6 Portrait of Miss Evelyn

Sharp. By E. A. Walton . . “Page 7

II. Puck .

III. Enfant Terrible .

IV. A Nursery Rhyme

Heroine

V. Almost a Portrait . . Ethel Reed . 55

VI. A Landscape

. Alfred Thornton . 138

VII. The Muslin Dress . Mabel

Dearmer . . 188

VIII. A Pathway to the

Moon

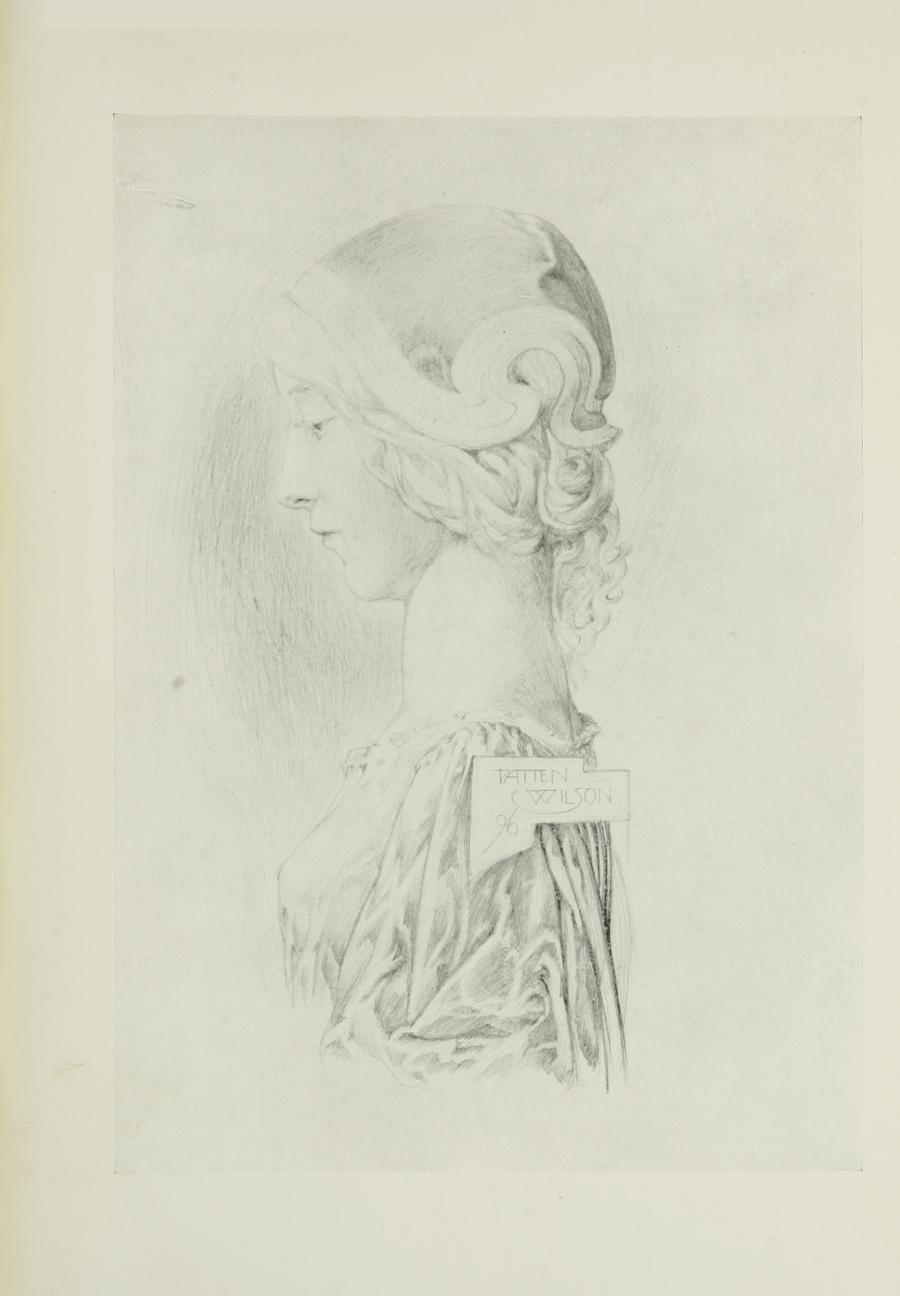

IX. A Silverpoint . . Patten Wilson . . 243

X. Maternity

XI. Grief .

XII. A Study of Trees . Aline

Szold . . 283

XIII. Ferry Bridge

.

XIV. The Harvest MoonCharles Pears . . 307

The Front Cover Design and

Title-page are

by ETHEL REED.

The Lost Eden

By William Watson

PROFFERING fortunes

Out of his indigence,

Royal the dowry

Man promised his soul.

“Not as the beasts

That perish, am I,” he said.

“Mine is eternity,

Theirs the frail day.”

Crown of creation

Long he conceited him

Next to their fashioner,

Lord of the worlds.

So

* Copyright in America by John Lane.

So in an Eden

Dwelt he, of fantasies.

Here and not otherwhere

Eve was his bride.

Eve the hot-hearted !

Eve the wild spirit

Of quest the adventurer !

Eve the unslaked.

She it was showed him

Where, in the midst

Of his pleasance, the knowledge-tree

Waiting him grew.

Wondrous the fruitage,

Maddening the taste therof;

Fiery like wine was it,

Fierce like a sting.

Straightway

Straightway his Eden

Irked like a prison-house.

Vastness invited him.

“Come,” said the stars.

Thunderous behind him

Clang the gold Eden-gates.

Boundless in front of him

Opens the world.

Never returns he !—

Never again,

In the valleys that nurtured him,

Breathes the old airs !

Only in dreams

He seeks his lost heritage,

Knocks at the Eden-gate,

Wistful, athirst.

Ah,

Ah, he is changed—

The sentinels know him not !

Here, ev’n in dreams,

He may enter no more.

She and He: Recent Documents

By Henry James

I HAVE been reading in the Revue de Paris for November

1st

1896 some fifty pages, of an extraordinary interest, which

have

had, as regards an old admiration, a very singular effect.

For many other

admirers, doubtless, who have come to fifty year

—admirers, I mean,

once eager, of the distinguished woman in

question—the perusal of

the letters addressed by Madame George

Sand to Alfred de Musset in the

course of a famous friendship

will have stirred in an odd fashion the

ashes of an early ardour. I

speak of ashes because early ardours, for the

most part, burn

themselves out, and the place they hold in our lives

varies, I

think, mainly according to the degree of tenderness with which

we gather up and preserve their dust ; and I speak of oddity

because

in the present case it is difficult to say whether the agita-

tion of the

embers results, in fact, in a returning glow or in a yet

more sensible

chill. That indeed is perhaps a small question

compared with the simple

pleasure of the reviving emotion. One

reads and wonders and enjoys again,

just for the sake of the

renewal. The small fry of the hour submit to

further shrinkage,

and we revert with a sigh of relief to the free genius

and large

life of one of the greatest of all masters of expression. Do

people

still handle the works of this master—people other than

young

ladies

ladies studying French with La Mare au Diable and a

dictionary ?

Are there persons who still read Valentine? Are there others who

resort to Mauprat ? Has André, the exquisite,

dropped out of

knowledge, and is any one left who remembers Teverino ? I ask

these questions for the mere

sweet sound of them, without the

least expectation of an answer. I

remember asking them twenty

years ago, after Madame Sand’s death, and not

then being hopeful

of the answer of the future. But the only response that

matters

to us perhaps is our own, even if it be after all somewhat

ambig-

uous. André and Valentine, then, are rather on our shelves than

in our hands,

but in the light of what is given us in the Revue de

Paris who shall say that we do not, and with avidity,

“read”

George Sand ? She died in 1876, but she lives again intensely

in these remarkable pages, both as to what in her spirit was most

interesting and what most disconcerting. We are vague as to

what they may

represent to the generation that has come to the

front since her death ;

nothing, I dare say, very imposing or even

very becoming. But they give

out a great deal to a reader for

whom, thirty years ago—the best

time to have taken her as a

whole—she was a high clear figure, a

great familiar magician.

This impression is a strange mixture, but perhaps

not quite

incommunicable ; and we are steeped as we receive it in one of

the most curious episodes in the annals of the literary race.

I

It is the great interest of such an episode that, apart from its

proportionate place in the unfolding of a personal life, it has a

wonderful deal to say to us on the much larger matter of the

relation

between experience and art. It constitutes an eminent

special

special case, in which the workings of that relation are more or

less

uncovered ; a case, too, of which one of the most remarkable

features is

that we are in possession of it almost exclusively by

the act of one of

the persons concerned. Madame Sand at least,

as we see to-day, was eager

to leave nothing undone that could

make us further acquainted than we were

before with one of the

liveliest chapters of her personal history. We

cannot, doubtless,

be sure that her conscious purpose in the production of

Elle et

Lui was to show us the process by which private

ecstacies and

pains find themselves transmuted in the artist’s workshop

into

promising literary material—any more than we can be certain of

her motive for making toward the end of her life earnest and

complete arrangements for the ultimate publication of the letters

in which

the passion is recorded and in which we can remount to

the origin of the

volume. If Elle et Lui had been the inevitable

picture, postponed and retouched, of the great adventure of her

youth, so

the letters show us the crude primary stuff from which

the moral

detachment of the book was distilled. Were they to

be given to the world

for the encouragement of the artist-nature

—as a contribution to

the view that no suffering is great enough,

no emotion tragic enough to

exclude the hope that such pangs may

sooner or later be aesthetically

assimilated ? Was the whole pro-

ceeding, in intention, a frank plea for

the intellectual and in some

degree even the commercial profit, for a

robust organism, of a

store of erotic reminiscence ? Whatever the reasons

behind the

matter, that is to a certain extent the moral of the strange

story.

It may be objected that this moral is qualified to come home

to us only

when the relation between art and experience really

proves a happier one

than it may be held to have proved in the

combination before us. The

element in danger of being most

absent from the process is the element of

dignity, and its presence,

so

so far as that may ever at all be hoped for in an appeal from a

personal

quarrel, is assured only in proportion as the aesthetic event,

standing on

its own feet, represents a solid gain. It was vain,

the objector may say,

for Madame Sand to pretend to justify by so

slight a performance as Elle et Lui that sacrifice of all delicacy

which

has culminated in this supreme surrender. “If you sacrifice

all delicacy,”

I hear such a critic contend, “show at least that

you were right by giving

us a masterpiece. The novel in ques-

tion is no more a masterpiece,” I

even hear him proceed, “than

any other of the loose, liquid, lucid works

of its author. By your

supposition of a great intention you give much too

fine an account

on the one hand of a personal habit of laxity and on the

other of

a literary habit of egotism. Madame Sand, in writing her tale

and in publishing her love-letters, obeyed no prompting more

complicated than that of exhibiting her personal (in which I

include her

verbal) facility, and of doing so at the cost of whatever

other persons

might be concerned ; and you are therefore—and

you might as well

immediately confess it—thrown back, for the

element of interest, on

the attraction of her general eloquence, the

plausibility of her general

manner and the great number of her

particular confidences. You are thrown

back on your mere

curiosity—thrown back from any question of

service rendered to

‘art.'” One might be thrown back, doubtless, still

further even

than such remarks would represent, if one were not quite

prepared

with the confession they recommend. It is only because such a

figure is interesting—in every manifestation—that the line

of its

passage is marked for us by traces, suggestions, possible lessons.

And to enable us to find them it scarcely need, after all, have

aimed so extravagantly high. George Sand lived her remark-

able life and

drove her perpetual pen, but the illustration that

I began by speaking of

is for ourselves to gather—if we can.

I remember

I remember hearing many years ago, in Paris, an anecdote for

the truth of

which I am far from vouching, though it professed

to come direct—an

anecdote that has recurred to me more than

once in turning over the

revelations of the Revue de Paris, and

without

the need of the special reminder (in the shape of an

allusion to her

intimacy with the hero of the story), contained in

those letters to

Sainte-Beuve which are published in the number

of November 15. Prosper

Mérimée was said to have related—

in a spirit I forbear to

qualify—that during a close union with

the author of Lélia he once opened his eyes, in the raw winter

dawn, to see his companion, in a dressing-gown, on her knees

before the

domestic hearth, a candlestick beside her and a red

madras round her head, making bravely, with her own

hands, the

fire that was to enable her to sit down betimes to urgent pen

and

paper. The story represents him as having felt that the spectacle

chilled his ardour and tried his taste ; her appearance was un-

fortunate, her occupation an inconsequence, and her industry a

reproof—the result of all of which was a lively irritation and an

early rupture. For the firm admirer of Madame Sand’s prose the

little

sketch has a very different value, for it presents her in an

attitude

which is the very key to the enigma, the answer to most

of the questions

with which her character confronts us. She rose

early because she was

pressed to write, and she was pressed to

write because she had the

greatest instinct of expression ever

conferred on a woman ; a faculty that

put a premium on all passion,

on all pain, on all experience and all

exposure, on the greatest

variety of ties and the smallest reserve about

them. The really

interesting thing in these posthumous laideurs is the way the gift,

the voice, carries its possessor

through them and lifts her, on the

whole, above them. It gave her, it may

be confessed at the

outset and in spite of all magnanimities in the use of

it, an unfair

The Yellow Book—Vol. XII B

advantage

advantage in every connection. So at least we must continue to

feel

till—for our appreciation of this particular one—we have

Alfred de Musset’s share of the correspondence. For we shall

have it at

last, in whatever faded fury or beauty it may still possess

—to

that we may make up our minds. Let the galled jade wince,

it is only a

question of time. The greatest of literary quarrels

will in short, on the

general ground, once more come up—the

quarrel beside which all

others are mild and arrangeable, the eternal

dispute between the public

and the private, between curiosity

and delicacy.

This discussion is precisely all the sharper because it takes

place, for

each of us, within as well as without. When we wish

to know at all we wish

to know everything ; yet there happen to

be certain things of which no

better description can be given than

that they are simply none of our

business. “What is, then,

forsooth, of our

business ?” the genuine analyst may always ask ;

and he may easily

challenge us to produce any rule of general

application by which we shall

know when to go in and when to

back out. “In the first place,” he may

continue, “half the

‘interesting’ people in the world have, at one time or

another,

set themselves to drag us in with all their might ; and what in

the

world, in such a relation, is the observer, that he should absurdly

pretend to be in a greater flutter than the object observed ? The

mannikin, in all schools, is at an early stage of study of the human

form

inexorably superseded by the man. Say that we are to give

up the attempt

to understand : it might certainly be better so,

and there would be a

delightful side to the new arrangement. But in

the name of common sense

don’t say that the continuity of life is

not to have some equivalent in

the continuity of pursuit, the

continuity of phenomena in the continuity

of notation. There is

not a door you can lock here against the critic or

the painter

not

not a cry you can raise or a long face you can pull at him that

are not

absolutely arbitrary. The only thing that makes the

observer competent is

that he is not afraid nor ashamed ; the only

thing that makes him

decent—just think !—is that he is not

superficial.” All this

is very well ; but somehow we all equally

feel that there is clean linen

and soiled and that life would be

intolerable without an element of

mystery. M. Emile Zola, at

the moment I write, gives to the world his

reasons for rejoicing

in the publication of the physiological enquête of Dr. Toulouse—a

marvellous

catalogue or handbook of M. Zola’s outward and

inward parts, which leaves

him not an inch of privacy, so to

speak, to stand on, leaves him nothing

about himself that is for

himself, for his friends, his relatives, his intimates, his lovers, for

discovery, for emulation, for fond conjecture or flattering deluded

envy. It is enough for M. Zola that everything is for the public

and that

no sacrifice is worth thinking of when it is a question of

presenting to

the open mouth of that apparently gorged but still

gaping monster the

smallest spoonful of truth. The truth, to his

view, is never either

ridiculous or unclean, and the way to a better

life lies through telling

it, so far as possible, about everything and

about every one.

There would probably be no difficulty in agreeing to this if it

didn’t

seem, on the part of the speaker, the result of a rare

confusion between

give and take, or between “truth” and

information. The true thing that

most matters to us is the

true thing we have most use for, and there are

surely many

occasions on which the truest thing of all is the necessity of

the

mind—its simple necessity of feeling. Whether it feels in order

to learn or learns in order to feel, the event is the same : the side

on which it shall most feel will be the side to which it will most

incline. If it feels more about a Zola functionally undeciphered,

it

it will be governed more by that particular truth than by the truth

about

his digestive idiosyncrasies, or even about his “olfactive

perceptions”

and his “arithomania or impulse to count.” An

affirmation of our “mere

taste” may very supposably be our

individual contribution to the general

clearing-up. Nothing,

often, is less superficial than to skip or more

constructive (for

living and feeling at all) than to choose. If we are

aware that in

the same way as about a Zola undeciphered we should have

felt

more about a George Sand unexposed, the true thing we have

gained becomes a poor substitute for the one we have lost ; and I

scarce

know what difference it makes that the view of the elder

novelist appears,

in this matter, quite to march with that of the

younger. I hasten to add

that as to being, of course, asked why

in the world, with such a leaning,

we have given time either to

M. Zola’s physician or to De Musset’s

correspondent, that is

only another illustration of the bewildering state

of the

subject.

When we meet on the broad highway the rueful denuded figure

we need some

presence of mind to decide whether to cut it dead

or to lead it gently

home, and meanwhile the fatal complication

easily occurs. We have seen, in a flash of our own wit, and

mystery has

fled with a shriek. These encounters are indeed

accidents which may at any

time take place, and the general

guarantee, in a noisy world, lies, I

judge, not so much in any

hope of really averting them as in a regular

organisation of the

combat. The painter and the painted have duly and

equally to

understand that they carry their life in their hands. There are

secrets for privacy and silence ; let them only be cultivated on the

part of the hunted creature with even half the method with which

the love

of sport—or call it the historic sense—is cultivated on

the

part of the investigator. They have been left too much to

the

the natural, the instinctive man ; but they will be twice as effec-

tive

after it begins to be observed that they may take their place

among the

triumphs of civilisation. Then at last the game will

be fair and the two

forces face to face ; it will be “pull devil,

pull tailor,” and the

hardest pull will doubtless constitute the

happiest result. Then the

cunning of the inquirer, envenomed

with resistance, will exceed in

subtlety and ferocity anything we

to-day conceive, and the pale forewarned

victim, with every track

covered, every paper burnt and every letter

unanswered, will, in

the tower of art, the invulnerable granite, stand,

without a sally,

the siege of all the years.

II

It was not in the tower of art that Madame Sand ever shut

herself up ; but

I come back to a point already made in saying

that it is, in a manner, in

the citadel of style that, in spite of all

rash sorties, she continues to hold out. The outline of the

complicated story that was to cause so much ink to flow gives,

even with

the omission of a hundred features, a direct measure of

the strain to

which her astonishing faculty was exposed. In the

summer of 1833, as a

woman of nearly thirty, she encountered

Alfred de Musset, who was six

years her junior. In spite of their

youth they were already somewhat bowed

by the weight of a

troubled past. Musset, at twenty-three, had that of his

confirmed

libertinism—so Madame Arvède Barine, who has had access

to

materials, tells us in the admirable short biography of the poet

contributed to the rather markedly unequal but very interesting

series of

Hachette’s Grands Ecrivains Françis. Madame Sand

had a husband, a son and a daughter, and the impress of that

succession of lovers—Jules Sandeau had been one, Prosper

Mérimée

Mérimée another—to which she so freely alludes in the letters to

Sainte-Beuve, a friend more disinterested than these and qualified

to give

much counsel in exchange for much confidence. It

cannot be said that the

situation of either of our young persons

was of good omen for a happy

relation ; but they appear to have

burnt their ships with much promptitude

and a great blaze, and in

the December of that year they started together

for Italy. The

following month saw them settled, on a frail basis, in

Venice, where

Madame Sand remained till late in the summer of 1834 and

where she wrote, in part, Jacques and the Lettres d’un Voyageur, as

well as André and Leone-Leoni, and

gathered the impressions to be

embodied later in half-a-dozen stories with

Italian titles—notably

in the delightful Consuelo. The journey, the Italian climate, the

Venetian

winter at first agreed with neither of the friends ; they

were both taken

ill—the young man very gravely—and after a

stay of three

months De Musset returned, alone and much ravaged,

to Paris.

In the meantime a great deal had happened, for their union had

been stormy

and their security small. Madame Sand had nursed

her companion in illness

(a matter-of-course office, it must be

owned) and her companion had railed

at his nurse in health. A

young doctor, called in, had become a close

friend of both parties,

but more particularly a close friend of Madame

Sand, and it was to

his tender care that, on withdrawing, De Musset

solemnly

committed the lady. She lived with Pietro Pagello—the

transi-

tion is startling—for the rest of her stay, and on her

journey back

to France he was no inconsiderable part of her luggage. He

was

simple, robust and kind—not a man of genius. He remained,

however, but a short time in Paris. In the autumn of 1834 he

returned to

Italy, to live on till our own day, but never again, so

far as we know, to

meet his illustrious mistress. Her intercourse

with

with De Musset was, in all its intensity—one may almost say its

ferocity—promptly renewed, and was sustained in this key for

several months more. The effect of this strange and tormented

passion on

the mere student of its records is simply to make him

ask himself what on

earth is the matter with the subjects of it.

Nothing is more easy than to

say, as I have intimated, that it has

no need of records and no need of

students ; but this leaves out of

account the thick medium of genius in

which it was foredoomed

to disport itself. It was self-registering, as the

phrase is, for the

genius on both sides happened to be the genius of

eloquence. It

is all rapture and all rage and all literature. The Lettres d’un

Voyageur spring from the thick of the fight ; La Confession d’un

Enfant du Siècle and Les

Nuits are immediate echoes of the con-

cert. The lovers are

naked in the market-place and perform for

the benefit of humanity. The

matter with them, to the perception

of the stupefied spectator, is that

they entertained for each other

every feeling in life but the feeling of

respect. What the absence

of that article may do for the passion of hate

is apparently nothing

to what it may do for the passion of love.

By our unhappy pair, at any rate, the luxury in question—the

little

luxury of plainer folk—was not to be purchased, and in the

comedy

of their despair and the tragedy of their recovery nothing

is more

striking than their convulsive effort either to reach up to

it or to do

without it. They would have given for it all else they

possessed, but they

only meet in their struggle the inexorable

never. They strain and pant and gasp, they beat the

air in vain

for the cup of cold water of their hell. They missed it in a

way

for which none of their superiorities could make up. Their great

affliction was that each found in the life of the other an armoury

of

weapons to wound. Young as they were, young as Musset

was in particular,

they appeared to have afforded each other in that

direction

direction the most extraordinary facilities ; and nothing in the

matter of

the mutual consideration that failed them is more sad

and strange than

that even in later years, when their rage, very

quickly, had cooled, they

never arrived at simple silence. For

Madame Sand, in her so much longer

life, there was no hush, no

letting alone ; though it would be difficult

indeed to exaggerate

the depth of relative indifference from which, a few

years after

Musset’s death, such a production as Elle

et Lui could spring.

Of course there had been floods of

tenderness, of forgiveness ;

but those, for all their beauty of

expression, are quite another

matter. It is just the fact of our sense of

the ugliness of so much

of the episode that makes a wonder and a force of

the fine style,

all round, in which it is presented to us. This force, in

its turn,

is a sort of clue to guide—or perhaps rather a sign to

stay—our

feet in paths after all not the most edifying. It gives a

degree of

importance to the somewhat squalid and the somewhat ridiculous

story, and, for the old George-Sandist at least, lends a positive spell to

the smeared and yellowed paper, the blotted and faded ink. In this

twilight of association we seem to find a reply to our own challenge

and

to be able to tell ourselves why we meddle with such old, dead

squabbles

and waste our time with such grimacing ghosts. If we

were superior to the

weakness, moreover, how should we make our

point (which we must really

make at any cost) about the value of

this vivid proof that a great talent

is the best guarantee—that it

may really carry off almost anything

?

The rather sorry ghost that beckons us on furthest is the rare

personality

of Madame Sand. Under its influence—or that of old

memories from

which it is indistinguishable—we pick our steps

among the laideurs aforesaid : the misery, the levity, the

brevity

of it all, the greatest ugliness, in particular, that this life

shows us,

the way the devotions and passions that we see heaven and

earth

called

called to witness are over before we can turn round. It may be

said that,

for what it was, the intercourse of these unfortunates

surely lasted long

enough ; but the answer to that is that if it had

only lasted longer it

wouldn’t have been what it was. It was not

only preceded and followed by

intimacies, on one side and the

other, as unrestricted, but it was mixed

up with them in a manner

that would seem to us dreadful if it didn’t,

still more, seem to

us droll ; or rather perhaps if it didn’t refuse

altogether to come

home to us with the crudity of contemporary things. It

is

antediluvian history, a queer, vanished world—another Venice,

another Paris, an inextricable, inconceivable Nohant. This rele-

gates it to an order agreeable somehow to the imagination of the

fond

quinquegenarian, the reader with a fund of reminiscence.

The vanished

world, the old Venice, the old Paris are a bribe to

his judgment ; he has

even a glance of complacency for the lady’s

liberal foyer. Liszt, one lovely year at Nohant, “jouait du piano

au

rez-de-chaussée, et les rossignols, ivres de musique et de soleil,

s’égosillaient avec rage sur les lilas environnants.” The beautiful

manner

confounds itself with the conditions in which it was exer-

cised, the large

liberty and variety overflow into admirable prose,

and the whole thing

makes a charming faded medium in which

Chopin gives a hand to Consuelo and

the small Fadette has her

elbows on the table of Flaubert.

There is a terrible letter of the autumn of 1834, in which

Madame Sand has

recourse to Alfred Tattet in a dispute with the

bewildered

Pagello—a very disagreeable matter, hinging on a

question of money.

“A Venise il comprenait,” she somewhere

says ; “à Paris il ne comprend

plus.” It was a proof of remark-

able intelligence that he did understand

in Venice, where he had

become a lover in the presence and with the

exalted approbation

of an immediate predecessor—an alternate

representative of the

part,

part, whose turn had now, on the removal to Paris, come round

again and in

whose resumption of office it was looked to him to

concur. This

attachment—to Pagello—had lasted but a few

months ; yet

already it was the prey of disagreement and change,

and its sun appears to

have set in no very graceful fashion. We

are not here, in truth, among

very graceful things, in spite of

superhuman attitudes and great romantic

flights. As to these

forced notes, Madame Arvède Barine judiciously says

that the

picture of them contained in the letters to which she had had

access, and some of which are before us, “presents an example

extraordinary and unique of what the romantic spirit could do

with beings

who had become its prey.” She adds that she regards

the records in

question, “in which we follow step by step the

ravages of the monster,” as

“one of the most precious psycho-

logical documents of the first half of

the century.” That puts

the story on its true footing, though we may

regret that it should

not divide these documentary honours more equally

with some

other story in which the monster has not quite so much the best

of it. But it is the misfortune of the comparatively short and

simple annals of conduct and character that they should ever

seem to us,

somehow, to cut less deep. Scarce—to quote again

his best

biographer—had Musset, at Venice, begun to recover

from his illness

than the two lovers were seized afresh by le vertige

du sublime et de l’impossible. “Ils imaginèrent les

déviations de

sentiment les plus bizarres, et leur intérieur fut le

théâtre de scènes

qui égalaient en étrangeté les fantaises les plus

audacieuses de la

littérature contemporaine ; ” that is of the literature

of their own

day. The register of virtue contains no such lively

items—

save indeed in so far as these contortions and convulsions

were a

conscious tribute to virtue.

Ten weeks after Musset has left her in Venice Madame Sand

writes

writes to him in Paris: “God keep you, my friend, in your

present

disposition of heart and mind. Love is a temple built by

the lover to an

object more or less worthy of his worship, and

what is grand in the thing

is not so much the god as the altar.

Why should you be afraid of the risk

?”—of a new mistress, she

means. There would seem to be reason

enough why he should

have been afraid ; but nothing is more characteristic

than her

eagerness to push him into the arms of another woman—more

characteristic either of her whole philosophy of these matters or

of

their tremendous, though somewhat conflicting, effort to be

good. She is

to be good by showing herself so superior to jealousy

as to stir up in him

a new appetite for a new object, and he is to

be so by satisfying it to

the full. It appears not to occur to any

one that in such an arrangement

his own virtue is rather

sacrificed. Or is it indeed because he has

scruples—or even a

sense of humour—that she insists with

such ingenuity and such

eloquence? “Let the idol stand long or let it soon

break, you

will in either case have built a beautiful shrine. Your soul

will

have lived in it, have filled it with divine incense, and a soul like

yours must produce great works. The god will change perhaps ;

the

temple will last as long as yourself.” “Perhaps,” under the

circumstances,

was charming. The letter goes on with the

ample flow that was always at

the author’s command—an ease of

suggestion and generosity, of

beautiful melancholy acceptance, in

which we foresee, on her own horizon,

the dawn of new suns.

Her simplifications are delightful—they

remained so to the end ;

her touch is a wondrous sleight-of-hand. The

whole of this

letter, in short, is a splendid utterance and a masterpiece

of the

particular sympathy which consists of wishing another to feel as

you feel yourself. To feel as Madame Sand felt, however, one

had to

be, like Madame Sand, a man ; which poor Musset was far

from

from being. This, we surmise, was the case with most of her

lovers, and the

verity that makes the idea of her liaison with

Mérimée, who was one, sound almost like a union

against nature.

She repeats to her correspondent, on grounds admirably

stated,

the injunction that he is to give himself up, to let himself go,

to

take his chance. That he took it we all know—he followed her

advice only too well. It is indeed not long before his manner of

doing so draws from her a cry of distress. “Ta conduite est

déplorable,

impossible. Mon Dieu, à quelle vie vais-je te laisser ?

1’ivresse, le vin,

les filles, et encore et toujours !” But apprehen-

sions were now too late

; they would have been too late at the

very earliest stage of this

celebrated connection.

III

The great difficulty was that, though they were sublime, the

couple were

not serious. But, on the other hand, if, on a lady’s

part, in such a

relation, the want of sincerity or of constancy is a

grave reproach, the

matter is a good deal modified when the lady,

as I have mentioned, happens

to be—I won’t go so far exactly as

to say a gentleman. That George

Sand just fell short of this

character was the greatest difficulty of all

; because if a woman, in

a love-affair, may be—for all she is to

gain or to lose—what she

likes, there is only one thing that, to

carry it off with any degree

of credit, a man may be. Madame Sand forgot

this on the day

she published Elle et Lui ; she

forgot it again, more gravely, when

she bequeathed to the great snickering

public these present shreds

and relics of unutterably delicate things. The

aberration connects

itself with the strange lapses of still other

occasions—notably with

the extraordinary absence of scruples with

which, in the delightful

Histoire

Histoire de ma Vie, she gives away, as we say, the

character of her

remarkable mother. The picture is admirable for

vividness, for

touch ; it would be perfect from any hand not a daughter’s,

and

we ask ourselves wonderingly how, through all the years, to make

her capable of it, a long perversion must have worked and the

filial

fibre—or rather the general flower of sensibility—have been

battered. Not this particular anomaly, however, but some others

certainly,

clear up more or less in the light of the reflection that

as, just after

her death, a very perceptive person who had known

her well put it to the

author of these remarks, she was a woman

quite by accident. Her immense

plausibility was almost the only

sign of her sex. She needed always to

prove that she had been in

the right ; as how indeed could a person fail

to, who, thanks to the

special equipment I have named, might prove it so

easily ? It is

not too much to say of her gift of expression—and I

have already

in effect said it—that, from beginning to end, it

floated her over

the real as a high tide floats a ship over the bar. She

was never

left awkwardly straddling on the sandbank of fact.

For the rest, at any rate, with her free experience and her free

use of it,

her literary style, her love of ideas and questions, of

science and

philosophy, her camaraderie, her boundless tolerance,

her intellectual patience, her personal good-humour and perpetual

tobacco (she smoked long before women at large felt the cruel

obligation),

with all these things and many I don’t mention, she

had morally more of

the notes of the other sex than of her own.

She had above all the mark

that, to speak at this time of day with

a freedom for which her action in

the matter of publicity gives us

warrant, the history of her personal

passions reads singularly like a

chronicle of the ravages of some male

celebrity. Her relations

with men closely resembled those relations with

women that, from

the age of Pericles or that of Petrarch, have been

complacently

commemorated

commemorated as stages in the unfolding of the great statesman

and the

great poet. It is very much the same large list, the same

story of free

appropriation and consumption. She appeared in

short to have lived through

a succession of such ties exactly in the

manner of a Goethe, a Byron or a

Napoleon ; and if millions of

women, of course, of every condition, had

had more lovers, it was

probable that no woman, independently so occupied

and so

diligent, had ever had, as might be said, more unions. Her

fashion was quite her own of extracting from this sort of experi-

ence all

that it had to give her, and being withal only the more

just and bright

and true, the more sane and superior, improved

and improving. She strikes

us, in the benignity of such an

intercourse, as even more than maternal :

not so much the mere

fond mother as the supersensuous grandmother of the

wonderful

affair. Is not that practically the character in which Thérèse

Jacques studies to present herself to Laurent de Fauvel ? the light

in which Lucrezia Floriani (a memento of a friendship

for

Chopin, for Liszt) shows the heroine as affected toward Prince

Karol and his friend ? George Sand is too inveterately moral, too

preoccupied with that need to do good which is often, in art, the

enemy of

doing well ; but in all her work the story-part, as

children call it, has

the freshness and good faith of a monastic

legend. It is just possible

indeed that the moral idea was the real

mainspring of her course—I

mean a sense of the duty of avenging

on the unscrupulous race of men their

immemorial selfish success

with the plastic race of women. Did she wish

above all to turn

the tables—to show how the sex that had always

ground the other

in the intellectual mill was on occasion capable of being

ground ?

However this may be, nothing is more striking than the im-

punity with which

she gave herself to conditions that are usually

held to denote or to

involve a state of demoralisation. This

impunity

impunity (to speak only of consequences or features that concern

us) was not, I

admit, complete, but it was sufficiently so to

warrant us in saying that no one

was ever less demoralised. She

presents a case prodigiously discouraging to the

usual view—the

view that there is no surrender to “unconsecrated” passion

that

we escape paying for in one way or another. It is, frankly, diffi-

cult to

see where this eminent woman conspicuously paid. She

positively got off from

paying—and in a cloud of fluency and

dignity, benevolence, intelligence.

She sacrificed, it is true, a

handful of minor coin—met the loss by

failing, in her picture of

life, wholly to grasp certain shades and certain

differences. What

she paid was just this loss of her touch for them. That is one

of

the reasons, doubtless, why to-day the picture in question has

perceptibly

faded—why there are persons who would perhaps even

go so far as to say

that it has really a comic side. She doesn’t

know, according to such persons,

her right hand from her left,

the crooked from the straight and the clean from

the unclean : it

was a sense she lacked or a tact she had rubbed off, and her

great

work is, by this fatal twist, quite as lopsided a monument as the

leaning

tower of Pisa. Some readers may charge her with a

graver confusion

still—the incapacity to distinguish between

fiction and fact, the truth

straight from the well and the truth

curling in steam from the kettle and

preparing the comfortable

tea. There is no word oftener on her pen, they will

remind us,

than the verb to “arrange.” She arranged constantly, she ar-

ranged

beautifully ; but from this point of view—that of suspicion

—she

always proved too much. Turned over in the light of it

the story of Elle et Lui, for instance, is an attempt to prove

that

the mistress of Laurent de Fauvel was a regular prodigy

of virtue. What is there

not, the intemperate admirer may be

challenged to tell us, an attempt to prove

in L’Histoire de ma

Vie?

Vie ?—a work from which we gather every

delightful impression

but the impression of an impeccable veracity.

These reservations may, however, all be sufficiently just

without affecting

our author’s peculiar air of having eaten her cake

and had it, been

equally initiated in directions the most opposed.

Of how much cake she

partook the letters to Musset and Sainte-

Beuve well show us, and yet they

fall in at the same time, on

other sides, with all that was noble in her

mind, all that is

beautiful in the books just mentioned and in the six

volumes of

the general Correspondance :

1812-1876, out of which Madame

Sand comes so immensely to her

advantage. She had, as liberty,

all the adventures of which the dots are

so put on the i’s by the

documents lately published, and then she had, as

law, as honour

and serenity, all her fine reflections on them and all her

splendid,

busy, literary use of them. Nothing perhaps gives more relief to

her masculine stamp than the rare art and success with which she

cultivated an equilibrium. She made, from beginning to end, a

masterly

study of composure, absolutely refusing to be upset,

closing her door at

last against the very approach of irritation and

surprise. She had arrived

at her quiet, elastic synthesis—a good-

humour, an indulgence that

were an armour of proof. The great

felicity of all this was that it was

neither indifference nor renun-

ciation, but on the contrary an intense

partaking ; imagination,

affection, sympathy and life, the way she had

found for herself of

living most and living longest. However well it all

agreed with

her happiness and her manners, it agreed still better with her

style,

as to which we come back with her to the sense that this was

really her point d’appui or sustaining force. Most

people have to

say, especially about themselves, only what they can; but

she

said—and we nowhere see it better than in the letters to

Musset—

everything in life that she wanted. We can well imagine

the

effect

effect of that consciousness on the nerves of this particular corre-

spondent, his own poor gift of occasional song (to be so early

spent)

reduced to nothing by so unequalled a command of the

last word. We feel

it, I hasten to add, this last word, in all her

letters : the occasion, no

matter which, gathers it from her as the

breeze gathers the scent from the

garden. It is always the last

word of sympathy and sense, and we meet it

on every page of the

voluminous Correspondance.

These pages are not so “clever”

as those, in the same order, of some other

famous hands—the writer

always denied, justly enough, that she had

either wit or drollery—

and they are not a product of high spirits

or of a marked avidity

for gossip. But they have admirable ease, breadth

and generosity ;

they are the clear, quiet overflow of a very full cup.

They speak

above all for the author’s great gift, her eye for the inward

drama.

Her hand is always on the fiddle-string, her ear is always at the

heart. It was in the soul, in a word, that she saw the play begin,

and to the soul that, after whatever outward flourishes, she saw it

confidently come back. She herself lived with all her perceptions

and in

all her chambers—not merely in the showroom of the shop.

This

brings us once more to the question of the instrument and

the tone, and to

our idea that the tone, when you are so lucky as

to possess it, may be of

itself a solution.

By a solution I mean a secret for saving not only your reputa-

tion but your

life—that of your spirit ; an antidote to dangers

which the

unendowed can hope to escape by no process less

uncomfortable or less

inglorious than that of prudence and

precautions. The unendowed must go

round about ; the others

may go straight through the wood. Their

weaknesses, those of

the others, shall be as well redeemed as their books

shall be well

preserved ; it may almost indeed be said that they are made

wise

in spite of themselves. If you have never, in all your days, had a

The Yellow Book—Vol. XII. c

weakness,

weakness, you can be, after all, no more, at the very most, than

large and

cheerful and imperturbable. All these things Madame

Sand managed to be on

just the terms she had found, as we see,

most convenient. So much, I

repeat, does there appear to be in a

tone. But if the perfect possession

of one made her, as it well

might, an optimist, the action of it is

perhaps more consistently

happy in her letters and her personal records

than in her “creative”

work. Her novels to-day have turned rather pale and

faint, as

if the image projected—not intense, not absolutely

concrete—failed

to reach completely the mind’s eye. And the odd

point is that

the wonderful charm of expression is not really a remedy for

this

lack of intensity, but rather an aggravation of it through a sort of

suffusion of the whole thing by the voice and speech of the author.

These things set the subject, whatever it be, afloat in the upper

air,

where it takes a happy bath of brightness and vagueness or

swims like a

soap-bubble kept up by blowing. This is no draw-

back when she is on the

ground of her own life, to which she is

tied, in truth, by a certain

number of tangible threads ; but to

embark on one of her confessed

fictions is to have—after all that

has come and gone, in our time,

in the trick of persuasion—a

little too much the feeling of going

up in a balloon. We are

borne by a fresh, cool current, and the car

delightfully dangles ;

but as we peep over the sides we see

things—as we usually know

them—at a dreadful drop beneath.

Or perhaps a better way to

express the sensation is to say what I have

just been struck with

in the re-perusal of Elle et

Lui ; namely that this book, like

others by the same hand,

affects the reader—and the impression is

of the oddest—not

as a first but as a second echo or edition of the

immediate real, or in

other words of the subject. The tale may

in this particular be taken as

typical of the author’s manner ;

beautifully told, but told, as if on a

last remove from the facts, by

some

some one repeating what he has read or what he has had from

another and

thereby inevitably becoming more general and super-

ficial, missing or

forgetting the “hard” parts and slurring them

over and making them up. Of

everything but feelings the pre-

sentation is dim. We recognise that we

shall never know the

original narrator and that Madame Sand is the only

one we can

deal with. But we sigh perhaps as we reflect that we may never

confront her with her own informant.

To that, however, we must resign ourselves ; for I remember

in time that

the volume from which I take occasion to speak

with this levity is the

work that I began by pronouncing a

precious illustration. With the aid of

the disclosures of the

Revue de Paris it was, as I hinted, to show us that

no mistakes

and no pains are too great to be, in the air of art,

triumphantly

convertible. Has it really performed this function ? I thumb

again my copy of the limp little novel and wonder what, alas !

I

shall reply. The case is extreme, for it was the case of a

suggestive

experience particularly dire, and the literary flower

that has bloomed

vipon it is not quite the full-blown rose.

“Oeuvre de rancune” Arvède

Barine pronounces it, and if we take

it as that we admit that the artist’s

distinctness from her material

was not ideally complete. Shall I not

better the question by

saying that it strikes me less as a work of rancour

than—in a

peculiar degree—as a work of egotism ? It becomes

in that light,

at any rate, a sufficiently happy affirmation of the

author’s

infallible form. This form was never a more successful

vehicle for the conveyance of sweet reasonableness. It is all

superlatively calm and clear ; there never was a kinder, balmier

last

word. Whatever the measure of justice of the particular

picture, moreover,

the picture has only to be put beside the

recent documents, the “study,”

as I may call them, to illustrate

the

the general phenomenon. Even if Elle et Lui is not the

full-

blown rose, we have enough here to place in due relief an

irrepressible tendency to bloom. In fact I seem already to

discern that

tendency in the very midst of the storm ; the

“tone” in the letters too

has its own way and performs on its

own account—which is but

another manner of saying that the

literary instinct, in the worst

shipwreck, is never out of its depth.

Madame Sand could be drowned but in

an ocean of ink. Is

that a sufficient account of what I have called the

laying bare

of the relation between experience and art ? With the two

elements, the life and the genius, face to face—the smutches

and quarrels at one end of the chain, and the high luminosity

at the

other—does some essential link still appear to be missing ?

How do

the graceless facts, after all, confound themselves with

the beautiful

spirit ? They do so, incontestably, before our

eyes, and the mystification

remains. We try to trace the process,

but before we break down we had

better perhaps hasten to

grant that—so far at least as George Sand

is concerned—some

of its steps are impenetrable secrets of the

grand manner.

My Note-Book in the Weald

THE title of these sketches has reference to many wanderings,

afoot,

driving, but mainly on horseback, which I have enjoyed

from time to time

in the wealds of Surrey and Sussex. If you

stand on Blackdown or on Witley

Hill and look out over the folds

and oak-forests spread below you to the

very verge of the downs,

you see the country where Stephen Yesser still

carves the haunch

of mutton—as I believe, inimitably : and the

country where the

landlord’s wedding, at which I assisted, is still

remembered as one

of the merriest days in Puddingfold.

I—Stephen Yesser

To see him standing by the sideboard in his loose-fitting dress-

suit, his

eye upon the table in the window no less than on

the table by the fire and

the table in the centre, his ear hanging

upon the tinkle of the bell from

the commercial room and the

private sitting-room upstairs, where a party

was dining, his mind

upon the joint delicately furrowed by his unerring

carver—to see

him so, you might have mistaken him for an ordinary

waiter.

But even to call him a waiter of unusual ability would have

been

to

to show yourself obtuse. This large, fair fat man with the shaven

face,

double chin, even brick colour and eye of oyster blue, had a

character, and

it came out when I happened to be the only person

in the coffee-room that

evening.

“Nice little dog, Miss ?” he began, insinuatively stroking my

self-centred,

unresponsive terrier—”I’m very fond of dogs myself;

bulls, I mostly

fancy, tho’ I’ave kep’ all sorts one way an’ another.”

His voice had the

low, furtive quality that distinguishes the sport-

ing class in the South

country, the class, in fact, that “‘as kep’ all

sorts.” If his clothes had

fitted more tightly upon his big

frame, you would have suspected him of

having been a prize

fighter.

I made an encouraging reply.

“If you was once to ‘ave one you’d never take to no other sort.”

There was

a gentle defiance in his round, even voice, a voice that

had the training

of an ostler with a dash of a gentleman’s servant in

it. Sometimes his

lips moved as though turning a straw about in

his mouth ; his face in

repose had the eyebrows raised, the lines

from nostril to lip-corner

deeply marked, the mouth pulled down

but with no effect of sneering in its

sneer ; rather the acrid cheer-

fulness of a man not too successful, but

still nowise to be accounted

a failure, a man acquainted with the

compensations of life. “I

shouldn’t recommend the brindle myself ; now a

nice pure w’ite

with a butterfly nose would be as neat a pet as any lady

could wish

to have. I’ve not long parted with my Snowdrop ; won a rare

lot o’ prizes with ‘er, till a gentleman—well, you might know him

Miss, Captain Soames of the Cawbineers ? ‘E awffered me

twenty-two

pound for ‘er an’ I let ‘er go.” Melancholy triumphed

in the waiter’s

broad face for a moment ; his sad eye roved mechani-

cally to my plate.

“Cut you a little bit more off the ‘aunch,

Miss ? One of ‘er puppies took

second at the Palace and would

‘ave

‘ave ‘ad first, only the judge ‘e ‘ad a fancy for another pound or

so of

weight.”

I threw in the appropriate remark.

“There’s Mrs. Dempsey of Colmanhatch—you might ‘ave

noticed the

‘ouse as you come along, Miss, stands back a bit from

the road in a

s’rubbery—she wanted one of Snowdrop’s puppies,

an’ wouldn’t have

stopped at money neither, but I promised the

last to Mr. Hutton of the

‘George.'”

I foresaw tears on the part of the waiter if we didn’t speedily

abandon the

records of the Snowdrop family. I interposed with

a red herring.

“Yes, Miss, I daresay they are, but for my part I’d sooner ‘ave

a nice

sharp fox-terrier after game than any of them wiry-‘aired

ones. Now, one

Sunday morning I was up early walkin’ round

by Burley Rough—in the

summer I often takes a early turn that

way just to see the rabbits. Well,

this little fox-terrier I ‘ad

with me” (the waiter has an elusive

narrative habit, and though

with intelligence he can be followed, use is

really of most assist-

ance in gleaning his facts), “she started a rabbit

in a bit of

furze an’ off after it before I could holler.” I am not sure

if

Stephen really wished me to believe that he was at all likely to have

hollered. “She run it well out of sight, I never see a dog more

nimbler on her legs than what she was, an’ me after her. All at

wunst, I

‘eard ‘er sing out ; that fetched me on the track, and if

you’ll believe,

she was in the mouth of a burrer with her forefoot

in a steel trap an’ ‘ad

the rabbit in ‘er mouth, ‘an never left ‘old of

it. The rabbit bein’

lighter like ‘ad run clean over the trap an’

she’d just come up in time to

snap it from be’ine.”

I had two more courses to eat through and I perceived that the

waiter was

likely to draw heavily upon my appreciation. I econo-

mised with the

caution and the dexterity that come only of long

practice,

practice, at the same time I offered a perfectly adequate com-

ment.

“They pay men eighteen shillings a week to keep the rabbits

down and yet if

you was to ketch one in a snare an’ be found out

you’d ‘ave six

weeks.”

I tried to see myself, on the waiter’s suggestion, in this predica-

ment,

and admitted in the full glow of sympathy that it did seem

hard.

“An’ it is ‘ard,” said the waiter with conviction.

“You can’t

get a full-grown rabbit not under eighteenpence in the town,

an’

I’d sooner ketch one myself”—he dropped his voice to a note of

rapture—”I think they eat sweeter.”

It was impossible not to respond to the unquenchable human

nature in the

waiter’s eye. After all, they weren’t my rabbits.

A venal warmth chequered

the restraint of my smile. As the

irrigator directs the waterflow by a

slight turn of his foot, I

directed, just so quietly, the

conversation.

“Oh there is, Miss, a deal of poaching, to be sure. You see,

in the

winter-time, a man may be out of work and he knows

where ‘is two-and-nine is waitin’ for him when ‘e’s wearin’ ‘is

fur-lined overcoat, as the sayin’ goes. Yes, Miss ; two-an’-nine’s

what

they give for a hare—so I’ve been told.” Some day we may

have an

actor capable of this delicate manipulation of the pause—

I know of

none just now. “An’ then there’s them that does it

for the love of sport.”

I wanted some cheese, but I caught sight of the glow in the

oyster-eyes and

I prayed that nothing might divert the waiter to

a sense of his duties at

that moment. There is poetry in every

soul, we know ; by long study I have

learned to detect sometimes

the moment of the lighting of its fires. There

was that in the

waiter s kiln-brick face which a keen eye could recognise.

So

looks

looks the man who tells you of the one “woman in the world,”

so looks the

poet who describes his last sonnet, so look the faces

of them that dream

of heart’s desire.

“You see there’s a deal of preservin’ done round here, and

when a labourin’

man has say six or seven of a family and takes

‘is nine shillin’ a week,

as some of em do in winter, an’ ‘as coal to

find and boots to keep on the

children, well, ‘e ‘as to git it some-

where, asn’t he, Miss ? You can’t

wonder that some of ’em steps

out of a night an’ nooses a brace of

pheasants.” I maintained a

steady but an unexaggerated air of sympathy ;

there was no use

in the waiter putting it off, we had heard the

utilitarian side,

what about “them as does it for the love o’ sport ?” But

I was

much too wary to ask ! “An’ you see, Miss, since this frozen

meat come in, why eighteenpence ’11 buy a man ‘is leg of lamb

at the

stall. As for the poorer parts, they pretty near give it

away of a

Saturday night, an’ for two shillin he’ll get what’ll

keep ‘is family in

meat for a week.”

Very well, if I had to wait, I could wait.

“Every bit as good, Miss,” in answer to my query. “Of

course, it wants a

knack in cookin’, it don’t want to be put in no

fierce oven ; you want to

‘ang it in the kitchen and thor it out

gradual, an’ it’ll make twice its

size; then, if it’s nicely basted, you

won’t want to eat no sweeter bit of

meat.”

“Then they never eat the pheasants themselves ?” I remarked,

with the air

of one whose mind is on the central problem. “I

don’t wonder, for I think

a pheasant is nothing to rave about. I’d

as soon have a chicken.”

“If you’d ever tried one stuffed with chopped celery, then

closed up so the

water don’t get to it in a bit of nice paste, and

boiled for about two

hours, Miss,” said the waiter, in tender

remonstrance, “you’d never say

that again.” I was on the point

of

of offering never to say it again, when the waiter’s eyes again

sought the

furthest gas-burner at the end of the room, and an air

of reverie and

fervour again gleamed in his oyster-eye. “Wonderful

silly birds pheasants

are, Miss. You can go out with a line in

your pocket, an’ a fish ‘ook on

the end of it, an’ bait it with a

raisin, and ‘ang it over the

fence—”

“Do pheasants like raisins ?” I was idiot enough to interject ;

but

fortunately poetry and prudence may not burn in the same

brain at the same

time, and the waiter had abandoned himself to

poetry.

“Oh, marvellous fond of raisins, pheasants are. Of course, it

wants artful

doin’ ; the line wants to be ‘ung just so, and a

raisin

or two dropped where he’s likely to run, an’ ten to one ‘e’ll make a

peck at it—an’ the best of it is w’en ‘e’s got it the bird can’t

‘oller.”

I suppressed a weak desire to say it was shockingly cruel.

Mentally, I

surveyed myself with cold dislike as I heard myself

remark that it must be

very exciting work.

“I should say it was, Miss. These old poachers ‘as some fine

stories to

tell of it. Some likes a pea at the end of a few strands

of horse-hair.

‘Ow is it done ? Oh, you want to dror it long

from the horse’s tail, an’

then you twist it fine together an’ runs

it through the pea and makes a

knot. Some prefers a ‘ook in the

pea. Then, you see, the bird just

swallows it, and there he is.

With either the raisin hor the pea it wants to be ‘ung so’s the

bird, when he pecks

an’ takes it, ‘as ‘is feet just awf the ground.

It’s wonderful how quick they are to see it, too. Of course, it

has to be

a fine night, but I don’t care for too much moon my-

self.” The waiter was

unaware of this change of pronoun. “But

it’s wonderfully taking sport.

Well,” with a deprecatory smile,

which displayed an irreproachable set of

false teeth, ” I’ve ‘ad as

many as three in one evening.”

My

My morality being once in abeyance I did not stick at a hearty

encomium.

“Seen a bit of all sorts of life, I ‘ave. Well, I was in Tom

Hotchkiss’s

racing stables till I got too heavy, but I’ve always

been a great one for

sports or anything of that. Fine sideboardful

o’ cups I’ve got wot I’ve

won running ; I ‘ad a butter cooler,

silver-plated, only last year for the

Married Men’s ‘Undred Yard

Race.” Melancholy again descended like a mist

upon the waiter’s

cheerful countenance.

I feared he might have been reflecting on his growing handicap,

technical

or physical, and I deployed a reflection upon the variety

of his

experiences. He smiled again, and spoke softly of his lost

youth.

“Well, I began by bein’ apprentice’ to a butcher, an’ I stay’ at

that

eighteen months. Then one morning where I took the

meat down, the gardener

stop’ and ask me if I d care to come

hindoors”—some inner light illuminated this

phrase for me. It

did not mean would he step into the kitchen ; it meant

would he

take indoor service—” because ‘is master wanted a

page-boy, an’ I

jumped at this. Oh, I thought it grand—that was

with Mr.

Beatup at the ‘Bull,’ and I’ve been mostly in hotel service ever

since.” He paused ; he smiled thoughtfully, evidently a new idea

had

struck him. “It seems funny to say it,” he began almost

shamefacedly, “but

there’s one thing I ‘aven’t done, and that’s

drove a fly !” His air of

triumph was so na if and so marked

that I felt it to be a point worth

elucidating. I hunted for the

proper setting of the question ; I was

anxious not to make a

blunder.

“What, have you ever had a chance to ?” I said at last, and I

thought—indeed, still think—this very neat.

“Should ‘ave ‘ad,” said the waiter, quite respectfully but enjoy-

ing

ing the joke none the less, “for my father was a cab-proprietor

down in

Weymouth, since ever I remember. ‘Ad twenty-three

or twenty-four lots

going time he died, landaws and privek

brooms and closed-and-opens. ‘E was

a very curious man my

father, ‘e ‘ad a great belief in luck. Sometimes ‘e

would buy a

horse for luck, other times ‘e’d think one of ‘is carriages

brought

him bad luck. He always used to go about with a carriage dog,

one o’ them spotted—well, Darmations some calls ’em ; oh, she

was a beautiful creature—an’ knowin’! Well, there wasn’t any-

thing

she wouldn’t do. Why, she’d go up to one of the other

horses on the rank,

as it might be, what wasn’t my father’s, you

see, Miss, an’ she’d ackshly

pull the clover out of ‘is nose-bag and

kerry it to one of my father’s own

‘orses.” I blinked, but

got it down. “Ho, wonderful knowin’ she was !

There was

a lady there awffered my father eighteen sov’rins for her, but

‘e wouldn’t sell. ‘No,’ ‘e said, ‘if I sell my dog, I sell my

luck,’

‘e said, ‘besides, she wouldn’t stay with you, she’d always

be back in the

yard,’ ‘e said. Often enough she ask’ ‘im,

but ‘e always said the same

about ‘is luck. At last she came

and said she was goin’ away to live in

Brighton, and she

awffer’ him £20,” the waiter’s figures always came

out with a

suspicious glibness—”so father ‘e was beat, but ‘e says

‘so sure as

my name’s Stephen Yesser’—that was my father’s name an’

‘e

give me the same—’my luck’s sold’, ‘e says ! An’ it wasn’t a

twelvemonth later that ‘e was drivin’ home one night with

a horse

he’d bought in London some time before, an’ it bolted at

the scroop of a

tramway, turn’ the corner short and come down

pitchin’ father out and his

‘ead was all cut to pieces—killed ‘im on

the spot. He was took up

in a bag. Seems he might have fell

free if his coat hadn’t ‘ave caught in

the lamp-iron.” My mind

had filled suddenly with a lurid picture of Mr.

Yesser, senior,

being

being “took up in a bag,” but the waiter’s point was not lost upon

me for

all that. “But it was a funny thing after what he’d said

when ‘e come to

part with the Darmation, wasn’t it, Miss ?” he

said. “Yes, I know, I know,” this to a subordinate who appeared

at

the door, “it’s the hupstairs parlour bell, so you’ll escuse me,

Miss ; I

don’t mind to keep them waitin’ a minute, they ain’t

none of our

lot—business gentlemen from London.”

II—The Landlord’s Wedding

“CAN Mrs. Sollop have the landau this afternoon ? She

wishes to drive out

to Cray’s Wood ; have you a horse

disengaged about three ?”

I recognised the old Rector’s voice at once ; he spoke his

inquiry like a

piece of ritual—or is it rubric ?—in the tone

reserved for

celebrations. The reply was inaudible, but I was

quite sure that Mrs.

Sollop couldn’t have the landau : I had been

in the inn-yard that morning,

and I knew that the landau had

other fish to fry, so to speak. Words would

fail to depict the

ardour with which Tom and Frank, the two ostlers, had

been

assailing the old landau, leathers in hand and scarlet braces flying,

from an early hour ; they had got my wheel jack in use, and pail

after pail of water went through the spokes. They did not

apologise for

borrowing the wheel jack, and I recognised with

them that the occasion

lifted us all above considerations of common

formulae. Within the stable

could be seen the patient heads of

“the Teamster” and “Bay Bob”

(provisionally referred to as

“the pair”) dipping reflectively between the

pillar-chains. Poor

beasts, they knew something was going to happen, if it

were only

from the reek of “compo” on the harness. No hope of Mrs.

Sollop

Sollop getting up to Cray’s Wood—what a name, by the way,

for a

rector’s wife ? And for a Rector ! The Rev. Richard

Grace Sollop ; and it

is their name, too ; it’s certainly none of my

making.

I had a sort of feeling that I would like to lend a carriage and

“a pair,”

but at best I could only have proffered a scratch tandem,

Black Nannie in

the shafts and Nutcracker in front, and this

would certainly have

interrupted the ceremony.

There was an odd sense of stir about the Green. There was

not exactly a

crowd, but two or three more men than usual were

listening to the

blacksmith’s famous story of his six beagle

puppies ; beagle I say, but in

the interests of truth and dog-

breeding I ought to call it “very-nearly

beagle” puppies. The

old man who carries telegrams and wears a grey

surtout with a

rakish air of Stock-Exchange failure about it, has picked

up the

puppy that favours a fox-terrier, and Mr. Remmitt from the

grocer’s shop is explaining why he thinks the “spannel bitch” is

going to

make the best beagle of the lot. Although the whole

six are similarly

spotted in liver and black upon white, they are

all known by separate

names—like the above, of a narrowly

descriptive nature. They were

born and bred in the centre of

the Green, and every dog in the village has

a sort of proprietary

interest in them.

At this moment Mr. Hampshire passed from the telegraph

office ; he has his

bluish-pink trousers on and wears a black coat

and waistcoat, all new, a

black tie, and a straw hat. He is a very

shy man, and he has calculated to

a second when he will change

to a puce satin tie with white lozenges

before he starts ; whereas

the topper that came by post is to be taken

with him and assumed

en route ; I know this, for I saw Frank trying to get

it incon-

spicuously stowed under the cloth flap of the box-seat. What will

they

they do with the pasteboard box, I wonder ? Throw it away in

Ambledon Wood,

no doubt, to be picked up by some hawker and

used for a baby’s cradle or

to put a sitting hen in.

Ten o’clock, and he doesn’t start till eleven, and yet the poor

man cannot

be seen outside his own inn without some joke being

thrown at him, and a

convulsive titter issuing from the knot of

boys gathered on the

corpse-bench below the lych-gate.

Bang ! Now I know that that was a champagne cork

ex-

ploding in the commercial room, and they don’t explode of them-

selves—in an Inn !

Annie runs in to whisper :

“He’s got the ring on his third finger, fear he’d forget.”

“Well ! She must have a large hand if his third finger and

hers are the same size,” I observe. “Oh, it can’t be

the ring.”

Annie looks disheartened, but says she will ask Mrs. Groves.

“By the way, how is Mrs. Groves this morning ?” I had

for-

gotten her till now : she is the housekeeper, only five years Mr.

Hampshire’s senior and a widow ; one or two people had said,

before

the affair which finishes to-day was heard of . . . .

“Oh ! she’s wonderful down, and she gets a deal of chaff in

the bar.” In a

whisper behind a corner of her apron, ” Oh, she

‘as been treated bad.”

“Ah, she’ll be glad when it s over. Is that the carriage ?

Good gracious,

it’s not eleven ? How grand Tom looks on the

box ! and I would never have

said Bob and Teamster stood so

much of a height.”

There is a wild flight of a figure across the sweep as with

scarlet wings

to it, and Frank, pouring with perspiration, slogs at

the Teamster’s mane

with a water-brush, in a last agony of

fervour.

“Well, it really does look smart !” I exclaim at intervals to

Annie,