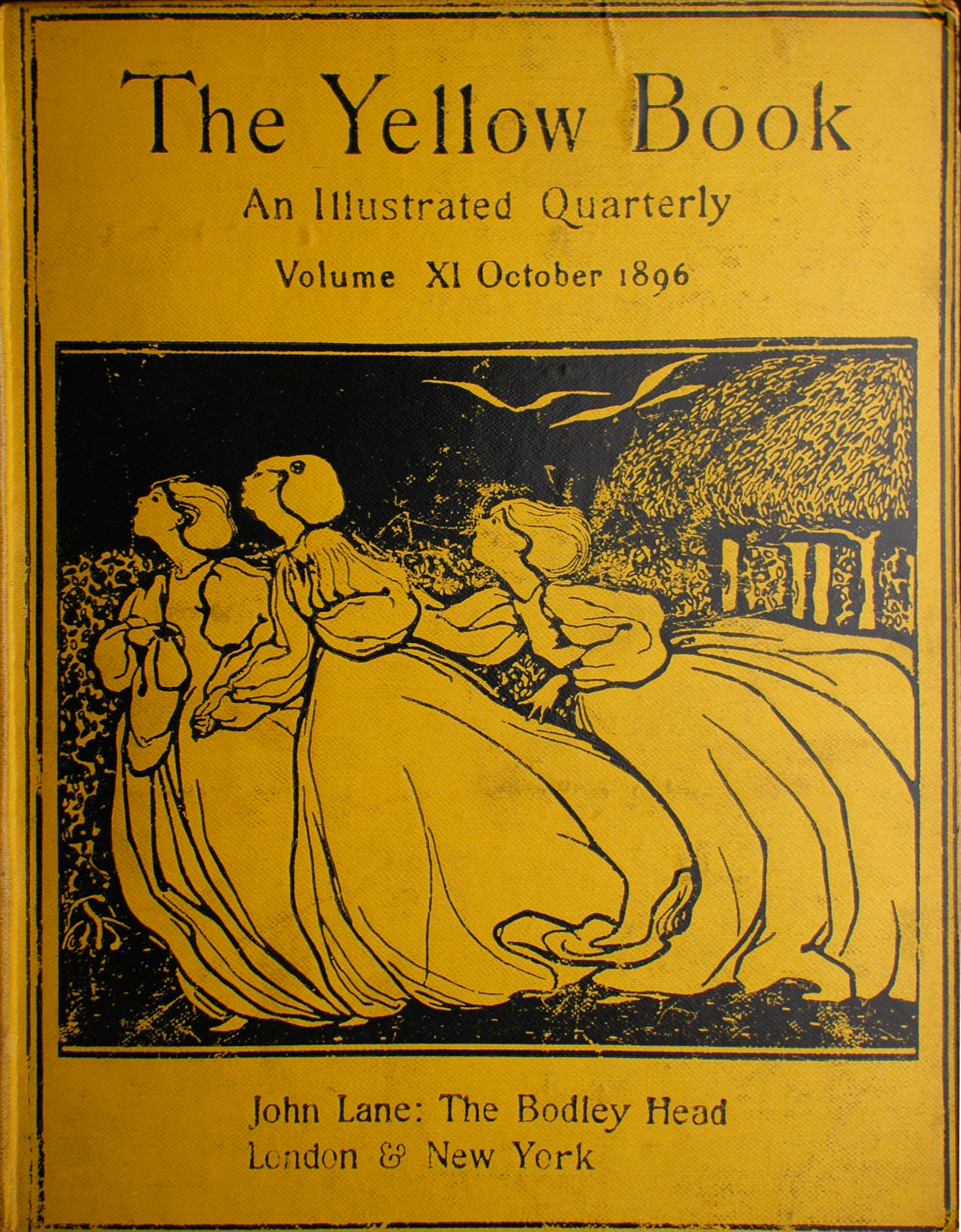

The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume XI October 1896

Contents

Literature

I. The Happy Hypocrite . By Max Beerbohm . Page 11

II. A Ballad of Cornwall . F. B. Money Coutts . 45

III. The Friend of Man . Henry Harland . . 51

IV. The Poetry of John Barlas . H. S. Salt . . . 80

V. The White Statue . Olive Custance . . 91

VI. Scarlet Runners . J. S. Pyke Nott . . 97

VII. The Elsingfords . . Robert Shews . . . 101

VIII. The Love Germ . . Constance Cotterell . 125

IX. Stories Toto Told Me . Baron Corvo. . . 143

X. Two Poems . . . Alma Strettell . . 163

XI. An Early Chapter . . H. Gilbert . . . 168

XII. The Heavenly Lover B. Paul Neuman . . 184

XIII. The Uttermost Farthing B. Paul Neuman . . 184

XIV. The Secret . . . T. Mackenzie . . 233

XV. A Chef d’œuvre . . Reginald Turner . . 237

XVI. The Closed Manuscript . Constance Finch . . 248

XVII. Chopin Op. 47 . . Stanley V. Makower . 250

XVIII. Lot 99 . . . . Ada Radford . . . 267

XIX. The Wind and the Tree Charles Catty . . 282

XX. Gabriele d’Annunzio . Eugene Benson . . . 284

XXI. The Darkened Room . Elsie Higginbotham . 300

XXII. A Marriage . . . Ella D’Arcy . . . 309

Art

The Yellow Book — Vol. XI. — October, 1896

Art

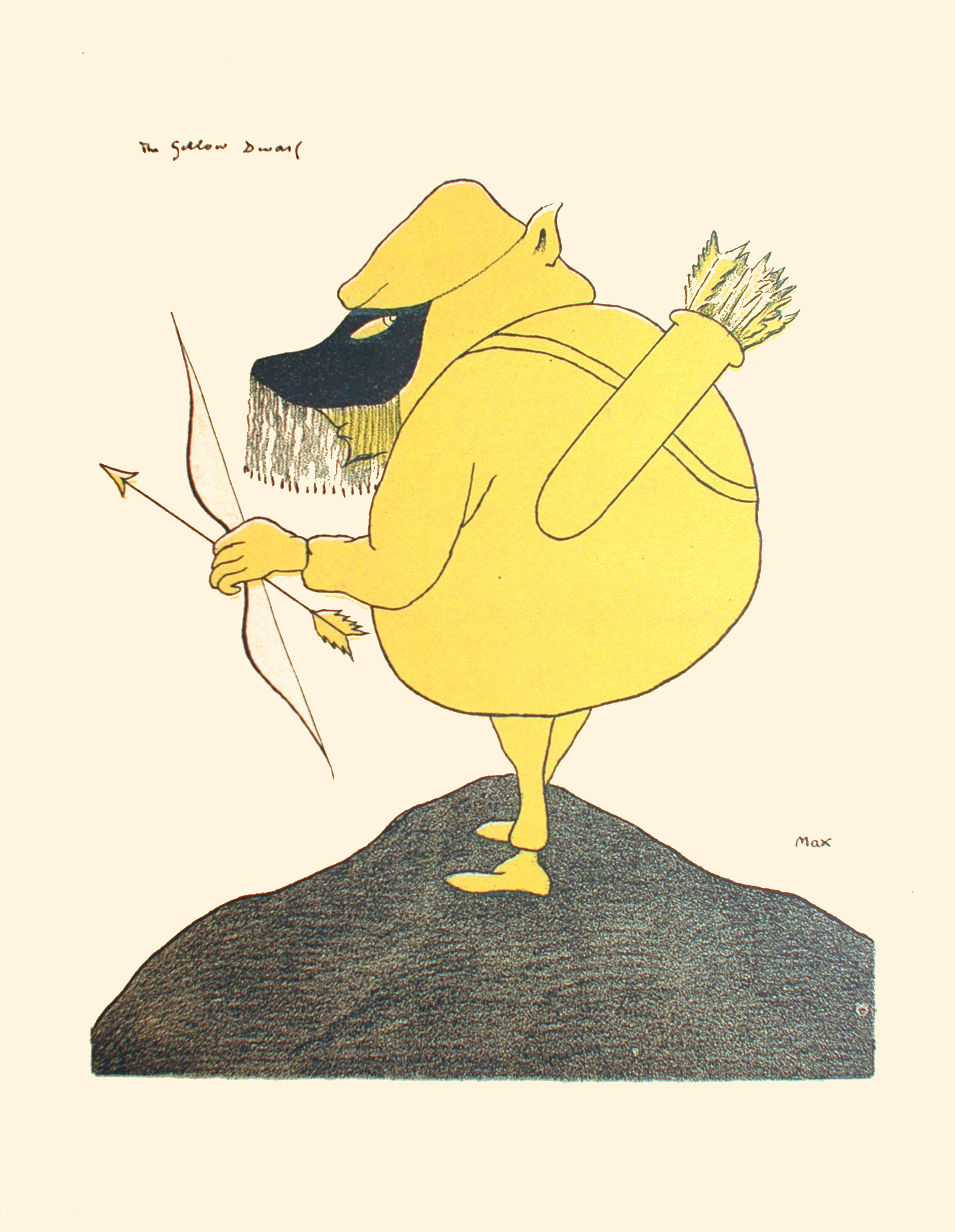

I. The Yellow Dwarf. By Max Beerbohm . Page 7

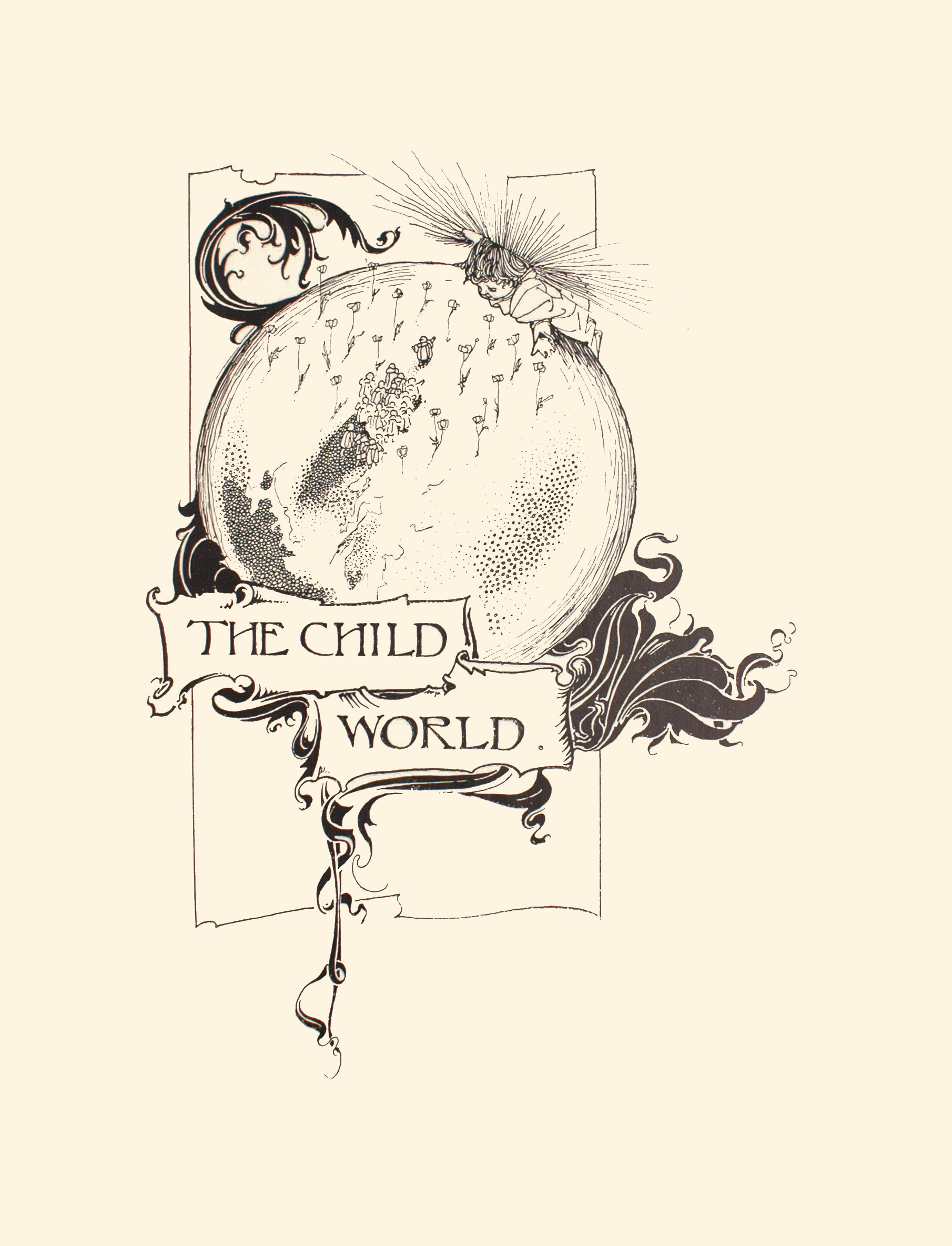

II. The Child’s World . Charles Robinson . . 48

III. Recreations of Cupid . Charles Condor . . 92

IV. A Romance . . . Charles Condor . . 92

V. St. Columb’s Porth, CornwallGertrude Prideaux-Brune . 140

VI. Bodley Heads, No. 5—Portrait of Mr. G. S. Street Francis Howard . . 230

VII. Bradda Head, Isle of Man . . . C. F. Pears . . . 259

VIII. Aberystwith, from Constitution Hill . . C. F. Pears . . . 259

IX. Study of a Head . . C. F. Pears . . . 259

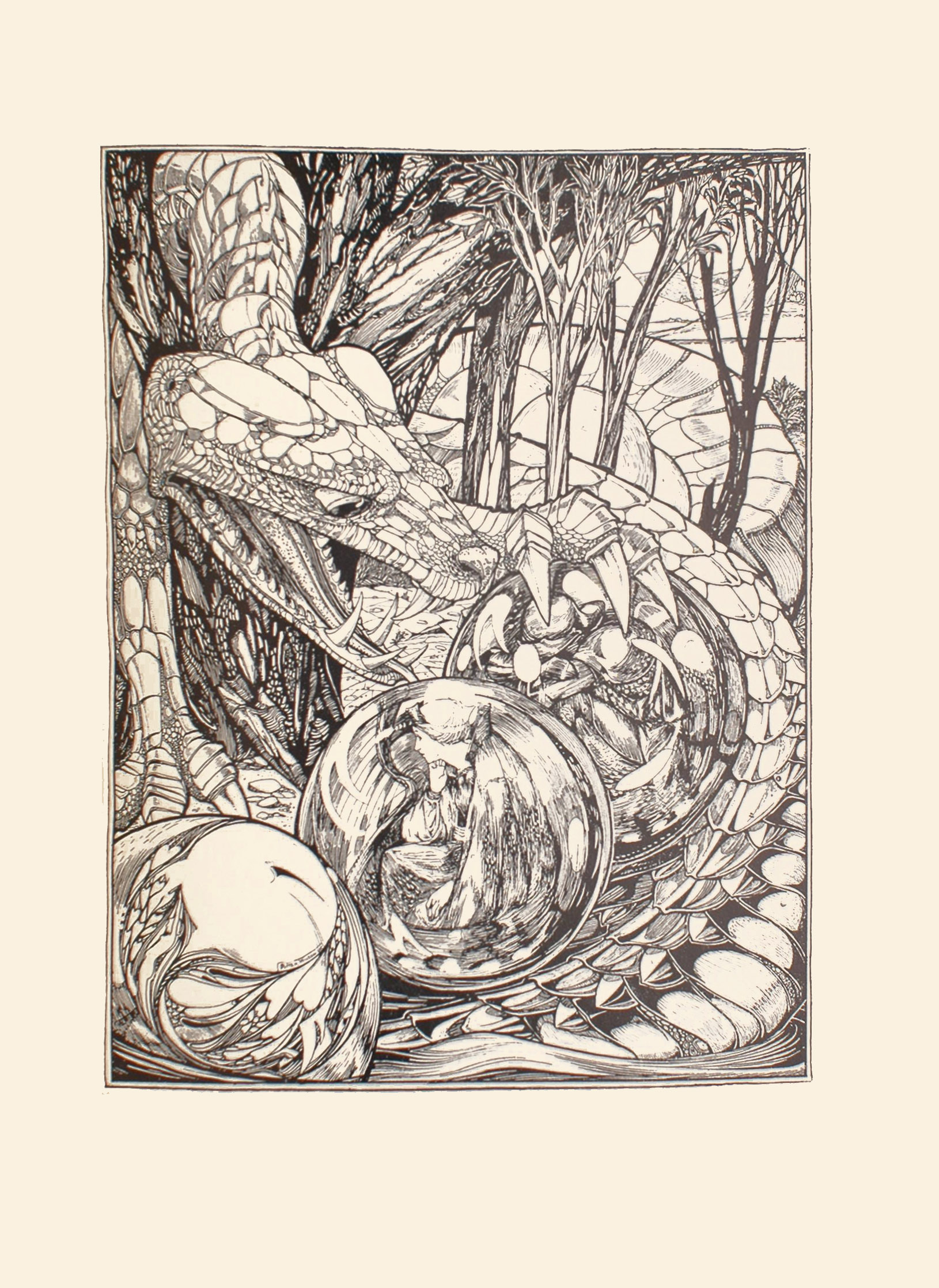

X. The War Horses of Rustem . . . Patten Wilson . . . 301

XI. A Phantasy . . . Patten Wilson . . . 301

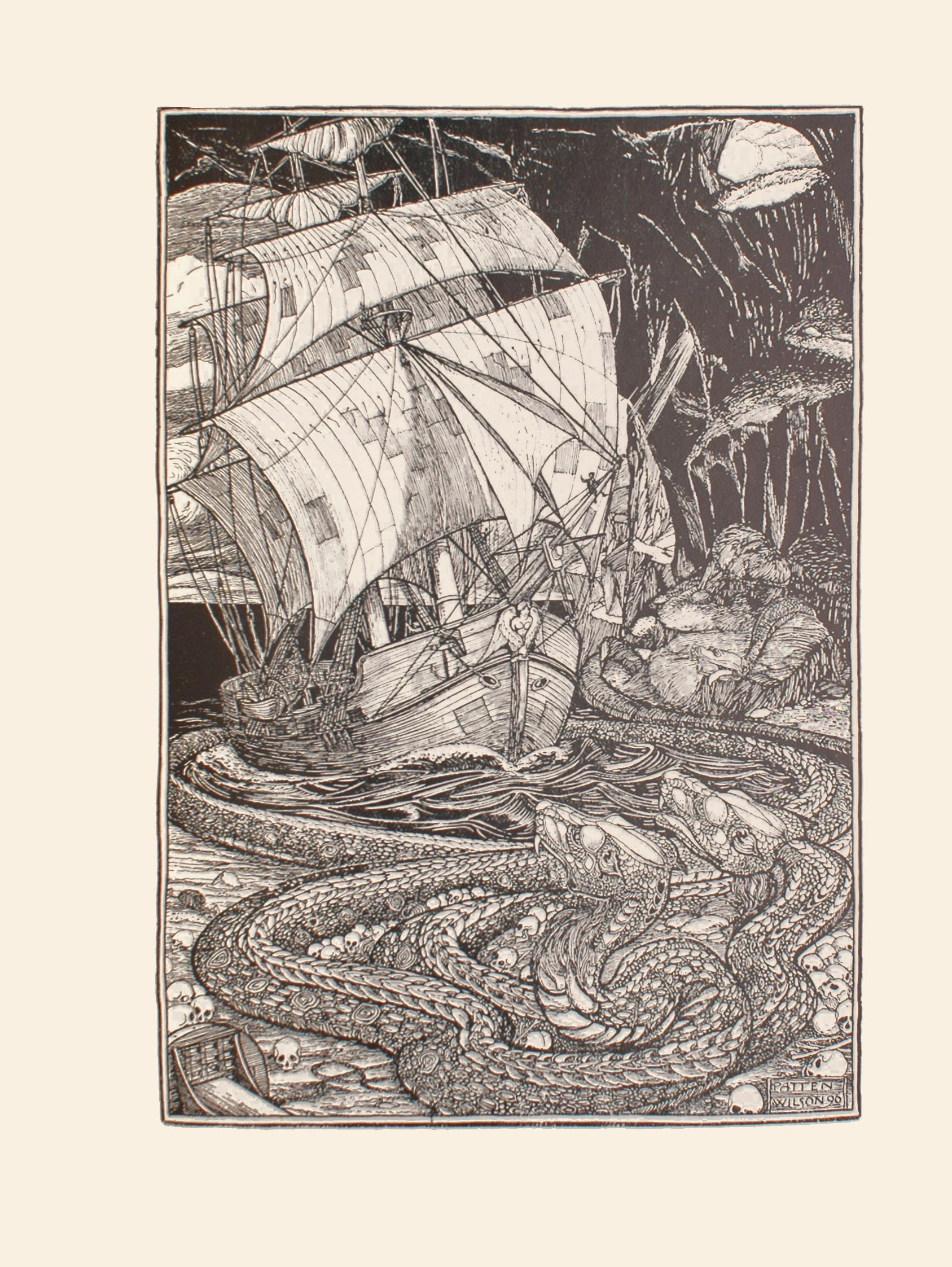

XII. ” So the wind drove us on Patten Wilson . . . 301

to the cavern of gloom

Where we fell in the toils

of the foul sea-snake ;

Their scaly folds drew us on

to our doom

Pray for us, stranger, for

Christ’s sweet sake.

The Title-page and Front Cover are by

NELLY SYRETT.

The Happy Hypocrite

By Max Beerbohm

NONE, it is said, of all who revelled with the Regent, was half

so wicked as Lord George Hell. I will not trouble my

little readers with a long recital of his great naughtiness. But it

were well they should know that he was greedy, destructive, and

disobedient. I am afraid there is no doubt that he often sat up

at Carlton House until long after bed-time, playing at games,

and that he generally ate and drank far more than was good for

him. His fondness for fine clothes was such, that he used to

dress on week-days quite as gorgeously as good people dress on

Sundays. He was thirty-five years old and a great grief to his

parents.

And the worst of it was that he set such a bad example to

others. Never, never did he try to conceal his wrong-doing; so

that, in time, every one knew how horrid he was. In fact, I

think he was proud of being horrid. Captain Tarleton, in his

account of Contemporary Bucks suggested that his lordship’s great

Candour was a virtue and should incline us to forgive some of his

abominable faults. But, painful as it is to me to dissent from any

opinion expressed by one who is now dead, I hold that Candour is

good, only when it reveals good actions or good sentiments, and

that, when it reveals evil, itself is evil, even also.

Lord

Lord George Hell did, at last, atone for all his faults, in a way

that was never revealed to the world during his life-time. The

reason of his strange and sudden disappearance from that social

sphere, in which he had so long moved and never moved again, I

will unfold. My little readers will then, I think, acknowledge

that any angry judgment they may have passed upon him must be

reconsidered and, it may be, withdrawn. I will leave his lordship

in their hands. But my plea for him will not be based upon that

Candour of his, which some of his friends so much admired.

There were, yes ! some so weak and so wayward as to think it a

fine thing to have an historic title and no scruples. ” Here comes

George Hell,” they would say. ” How wicked my lord is looking ! ”

Noblesse oblige, you see, and so an aristocrat should be very careful

of his good name. Anonymous naughtiness does little harm.

It is pleasant to record that many persons were unobnoxious to

the magic of his title and disapproved of him so strongly that,

whenever he entered a room where they happened to be, they

would make straight for the door and watch him very severely

through the key-hole. Every morning, when he strolled up

Piccadilly, they crossed over to the other side in a compact body,

leaving him to the companionship of his bad companions on that

which is still called the ” shady ” side. Lord George—οχετλιος—

was quite indifferent to this demonstration. Indeed, he seemed

wholly hardened, and, when ladies gathered up their skirts as they

passed him, he would lightly appraise their ankles.

I am glad I never saw his lordship. They say he was rather

like Caligula, with a dash of Sir John FalstafF, and that sometimes,

on wintry mornings in St. James s Street, young children would

hush their prattle and cling in disconsolate terror to their nurses’

skirts, as they saw him come (that vast and fearful gentleman ! )

with the east wind ruffling the round surface of his beaver,

ruffling

ruffling the fur about his neck and wrists, and striking the purple

complexion of his cheeks to a still deeper purple. ” King Bogey ”

they called him in the nurseries. In the hours when they too were

naughty, their nurses would predict his advent down the chimney or

from the linen-press, and then they always ” behaved.” So that, you

see, even the unrighteous are a power for good, in the hands of nurses.

It is true that his lordship was a non-smoker—a negative virtue,

certainly, and due, even that, I fear, to the fashion of the day—

but there the list of his good qualities comes to an abrupt con-

clusion. He loved with an insatiable love the Town and the

pleasures of the Town, whilst the ennobling influences of our

English lakes were quite unknown to him. He used to boast that

he had not seen a buttercup for twenty years, and once he called

the country ” A Fool’s Paradise.” London was the only place

marked on the map of his mind. London gave him all he wished

for. Is it not extraordinary to think that he had never spent a

happy day nor a day of any kind in Follard Chase, that desirable

mansion in Herts., which he had won from Sir Follard Follard, by

a chuck of the dice, at Boodle’s, on his seventeenth birthday ?

Always cynical and unkind, he had refused to give the broken

baronet his revenge. Always unkind and insolent, he had offered

to instal him in the lodge—an offer which was, after a little hesi-

tation, accepted. ” On my soul, the man s place is a sinecure,”

Lord George would say, ” he never has to open the gate to me.” *

So rust had covered the great iron gates of Follard Chase, and

moss had covered its paths. The deer browsed upon its terraces.

There were only wild flowers anywhere. Deep down among

the weeds and water-lilies of the little stone-rimmed pond he had

looked down upon, lay the marble faun, as he had fallen.

Of

* Lord Colerainis Correspondence, page 101.

Of all the sins of his lordship’s life, surely not one was more

wanton than his neglect of Follard Chase. Some whispered (nor

did he ever trouble to deny) that he had won it by foul means, by

loaded dice. Indeed no card-player in St. James s cheated more

persistently than he. As he was rich and had no wife and family

to support, and as his luck was always capital, I can offer no

excuse for his conduct. At Carlton House, in the presence of

many bishops and cabinet ministers, he once dunned the Regent

most arrogantly for 5000 guineas out of which he had cheated

him some months before, and went so far as to declare that he

would not leave the house till he got it ; whereupon His Royal

Highness, with that unfailing tact for which he was ever famous,

invited him to stay there as a guest ; which, in fact, Lord, George

did, for several months. After this, we can hardly be surprised

when we read that he ” seldom sat down to the fashionable game of

Limbo with less than four, and sometimes with as many as 7 aces up

his sleeve.” * We can only wonder that he was tolerated at all.

At Garble’s, that nightly resort of titled rips and roysterers, he

usually spent the early part of his evenings. Round the illumin-

ated garden, with La Gambogi, the dancer, on his arm and a

Bacchic retinue at his heels, he would amble leisurely, clad in

Georgian costume, which was not then, of course, fancy dress, as it

is now.☨ Now and again, in the midst of his noisy talk, he would

crack a joke of the period, or break into a sentimental ballad, dance

a little

* Contemporary Bucks, vol. i. page 73.

☨It would seem, however, that, on special occasions, his lordship

indulged in odd costumes. ” I have seen him,” says Captain Tarleton

(vol. i. p. 69), “attired as a French clown, as a sailor, or in the crimson

hose cf a Sicilian grandee—peu beau spectacle. He never disguised his

face, whatever his costume, nevertheless.”

a little, or pick a quarrel. When he tired of such fooling, he

would proceed to his box in the tiny al fresco theatre and patronise

the jugglers, pugilists, play-actors and whatever eccentric persons

happened to be performing there.

The stars were splendid, and the moon as beautiful as a great

camellia, one night in May, as his lordship laid his arms upon the

cushioned ledge of his box and watched the antics of the Merry

Dwarf, a little, curly-headed creature, whose dèbut it was. Cer-

tainly, Garble had found a novelty. Lord George led the applause,

and the Dwarf finished his frisking with a pretty song about

lovers. Nor was this all. Feats of archery were to follow. In

a moment, the Dwarf reappeared with a small, gilded bow in his

hand and a quiverful of arrows slung at his shoulder. Hither and

thither he shot these vibrant arrows, very precisely, several into

the bark of the acacias that grew about the overt stage, several

into the fluted columns of the boxes, two or three to the stars.

The audience was delighted. “Bravo! Bravo Saggitaro !

murmured Lord George, in the language of La Gambogi, who

was at his side. Finally, the waxen figure of a man was carried

on by an assistant and propped against the trunk of a tree. A scarf

was tied across the eyes of the Merry Dwarf, who stood in a

remote corner of the stage. Bravo indeed ! For the shaft had

pierced the waxen figure through the heart, or just where the

heart would have been, if the figure had been human, and not

waxen.

Lord George called for port and champagne and beckoned the

bowing homuncle to his box, that he might compliment him on

his skill and pledge him in a bumper of the grape.

” On my soul, you have a genius for the bow,” his lordship

cried, with florid condescension. ” Come and sit by me, but

first

first let me present you to my divine companion the Signora

—Gambogi Virgo and Sagittarius, egad ! You may have met on

the Zodiac.”

” Indeed, I met the Signora many years ago,” the Dwarf replied,

with a low bow. “But not on the Zodiac, and the Signora

perhaps forgets me.”

At this speech the Signora flushed angrily, for she was indeed

no longer young, and the Dwarf had a childish face. She thought

he mocked her. Her eyes flashed. Lord George’s twinkled rather

maliciously.

” Great is the experience of youth,” he laughed. ” Pray, are

you stricken with more than twenty summers ? ”

“With more than I can count,” said the Dwarf. “To the

health of your lordship ! ” and he drained his long glass of wine.

Lord George replenished it and asked by what means or miracle

he had acquired his mastery of the bow.

” By long practice,” the little thing rejoined; “long practice

on human creatures.” And he nodded his curls mysteriously.

” On my heart you are a dangerous box-mate.”

” Your lordship were certainly a good target.”

Little liking this joke at his bulk, which really rivalled the

Regent’s, Lord George turned brusquely in his chair and fixed

his eyes upon the stage. This time it was the Gambogi who

laughed.

A new operette, The Fair Captive of Samarcand, was being

enacted, and the frequenters of Garble s were all curious to behold

the new dèbutante, Jenny Mere, who was said to be both pretty

and talented. These predictions were surely fulfilled, when the

captive peeped from the window of her wooden turret. She

looked so pale under her blue turban. Her eyes were dark with

fear. Her parted lips did not seem capable of speech. “Is it

that

that she is frightened of us ? ” the audience wondered. ” Or of

the flashing scimitar of Aphoschaz, the cruel father who holds her

captive ?” So they gave her loud applause, and when, at length,

she jumped down, to be caught in the arms of her gallant lover,

Nissarah, and, throwing aside her Eastern draperies, did a simple

dance, in the convention of Columbine, their delight was quite

unbounded. She was very young and did not dance very well, it

is true, but they forgave her that. And when she turned in the

dance and saw her father with his scimitar, their hearts beat swiftly

for her. Nor were all eyes tearless, when she pleaded with him

for her life.

Strangely absorbed, quite callous of his two companions, Lord

George gazed over the footlights. He seemed as one who is in a

trance. Of a sudden, something shot sharp into his heart. In

pain he sprang to his feet and, as he turned, he seemed to see a

winged and laughing child, in whose hand was a bow, fly swiftly

away into the darkness. At his side, was the Dwarf s chair. It

was empty. Only La Gambogi was with him and her dark face

was like the face of a fury.

Presently he sank back into his chair, holding one hand to his

heart, that still throbbed from the strange transfixion. He

breathed very painfully and seemed scarce conscious of his sur-

roundings. But La Gambogi knew he would pay no more

homage to her now, for that the love of Jenny Mere had come

into his heart.

When the operette was over, his love-sick lordship snatched up

his cloak and went away without one word to the lady at his side.

Rudely he brushed aside Count Karoloff and Mr. FitzClarence,

with whom he had arranged to play hazard. Of his comrades, his

cynicism, his reckless scorn—of all the material of his existence—

he was oblivious now. He had no time for penitence or diffident

delay

delay. He only knew that he must kneel at the feet of Jenny

Mere and ask her to be his wife.

” Miss Mere is in her room,” said Garble, ” resuming her

ordinary attire. If your lordship deign to await the conclusion of

her humble toilet, it shall be my privilege to present her to your

lordship. Even now, indeed, I hear her footfall on the stair.”

Lord George uncovered his head and with one hand nervously

smoothed his rebellious wig.

” Miss Mere, come hither,” said Garble. , ” This is my Lord

George Hell, that you have pleased whom by your poor efforts

this night will ever be the prime gratification of your passage

through the roseate realms of art.”

Little Miss Mere, who had never seen a lord, except in fancy or

in dreams, curtseyed shyly and hung her head. With a loud

crash, Lord George fell on his knees. The manager was greatly

surprised, the girl greatly embarrassed. Yet neither of them

laughed, for sincerity dignified his posture and sent eloquence

from its lips.

” Miss Mere,” he cried, ” give ear, I pray you, to my poor

words, nor spurn me in misprision from the pedestal of your

Beauty, Genius and Virtue. All too conscious, alas ! of my pre-

sumption in the same, I yet abase myself before you as a suitor

for your adorable Hand. I grope under the shadow of your raven

Locks. I am dazzled in the light of those translucent orbs, your

Eyes. In the intolerable whirlwind of your Fame I faint and am

afraid.”

“Sir—” the girl began, simply.

” Say < My Lord, ” said Garble, solemnly.

” My lord, I thank you for your words. They are beautiful.

But indeed, indeed, I can never be your bride.”

Lord George hid his face in his hands.

“Child,”

” Child,” said Mr. Garble, ” let not the sun rise ere you have

retracted those wicked words.”

” My wealth, my rank, my irremediable love for you, I throw

them at your feet,” Lord George cried, piteously. ” I would wait

an hour, a week, a lustre, even a decade, did you but bid me

hope ! ”

“I can never be your wife,” she said, slowly. “I can never be

the wife of any man whose face is not saintly. Your face, my

lord, mirrors, it may be, true love for me, but it is even as a

mirror long tarnished by the reflection of this world s vanity. It

is even as a tarnished mirror. Do not kneel to me, for I am

poor and humble. I was not made for such impetuous wooing.

Kneel, if you please, to some greater, gayer lady. As for my

love, it is my own, nor can it be ever torn from me, but given, as

true love must needs be given, freely. Ah ! rise from your knees.

That man, whose face is wonderful as are the faces of the saints,

to him I will give my true love.”

Miss Mere, though visibly affected, had spoken this speech with

a gesture and elocution so superb, that Mr. Garble could not help

applauding, deeply though he regretted her attitude towards his

honoured patron. As for Lord George he was immobile as a

stricken oak. With a sweet look of pity, Miss Mere went her

way, and Mr. Garble, with some solicitude, helped his lordship to

rise from his knees. Out into the night, without a word, went

his lordship. Above him the stars were still splendid. They

seemed to mock the festoons of little lamps, dim now and gutter

ing, in the garden of Garble s. What should he do ? No

thoughts came. Only his heart burnt hotly. He stood on the

brim of Garble s lake, shallow and artificial as his past life had

been. Two swans slept on its surface. The moon shone strangely

upon their white, twisted necks. Should he drown himself?

The Yellow Book Vol. XI. B

There

There was no one in the garden to prevent him, and in the

morning they would find him floating there, one of the noblest of

love s victims. The garden would be closed in the evening.

There would be no performance in the little theatre. It might

be that Jenny Mere would mourn him. ” Life is a prison, without

bars,” he murmured, as he walked away.

All night long he strode, knowing not whither, through the

mysterious streets and squares of London. The watchmen, to

whom his figure was most familiar, gripped their staves at his

approach, for they had old reason to fear his wild and riotous

habits. He did not heed them. Through that dim conflict

between darkness and day, which is ever waged silently over our

sleep, Lord George strode on in the deep absorption of his love

and of his despair. At dawn, he found himself on the outskirts of

a little wood in Kensington. A rabbit rushed past him through

the dew. Birds were fluttering in the branches. The leaves

were tremulous with the presage of day, and the air was full of

the sweet scent of hyacinths.

How cool the country was ! It seemed to cure the feverish

maladies of his soul and consecrate his love. In the fair light of

the dawn he began to shape the means of winning Jenny Mere,

that he had conceived in the desperate hours of the night. Soon

an old woodman passed by, and, with rough courtesy, showed him

the path that would lead him quickest to the town. He was

loth to leave the wood. With Jenny, he thought, he would live

always in the country. And he picked a posy of wild flowers for

her.

His rentrée into the still silent town strengthened his Arcadian

resolves. He, who had seen the town so often in its hours of

sleep, had never noticed how sinister its whole aspect was. In its

narrow streets the white houses rose on either side of him like

cliffs

cliffs of chalk. He hurried swiftly along the unswept pavement.

How had he loved this city of evil secrets ?

At last he came to St. James’s Square, to the hateful door of his

own house. Shadows lay like memories in every corner of the

dim hall. Through the window of his room, a sunbeam slanted

across his smooth bed, and fell ghastly on the ashen grate.

It was a bright morning in Old Bond Street, and fat little Mr.

Aeneas, the fashionable mask-maker, was sunning himself at the

door of his shop. His window was lined as usual with all kinds of

masks—beautiful masks with pink cheeks, and absurd masks with

protuberant chins ; curious πρooδωπα copied from old tragic models ;

masks of paper for children, of fine silk for ladies, and of leather

for working men ; bearded or beardless, gilded or waxen (most of

them, indeed, were waxen), big or little masks. And in the

middle of this vain galaxy hung the presentment of a Cyclops’

face, carved cunningly of gold, with a great sapphire in its brow.

The sun gleamed brightly on the window, and on the bald head

and varnished shoes of fat little Mr. Aeneas. It was too early for

any customers to come, and Mr. Aeneas seemed to be greatly

enjoying his leisure in the fresh air. He smiled complacently as

he stood there, and well he might, for he was a great artist, and

was patronised by several crowned heads and not a few of the

nobility. Only the evening before, Mr. Brummell had come into

his shop and ordered a light summer mask, wishing to evade, for a

time, the jealous vigilance of Lady Otterton. It pleased Mr.

Aeneas to think that his art made him recipient of so many

high secrets. He smiled as he thought of the titled spendthrifts,

who, at this moment, perdus behind his masterpieces, passed un-

scathed among their creditors. He was the secular confessor of

his day, always able to give absolution. An unique position !

The

The street was as quiet as a village street. At an open window

over the way, a handsome lady, wrapped in a muslin peignoir, sat

sipping her cup of chocolate. It was La Signora Gambogi, and

Mr. Aeneas made her many elaborate bows. This morning,

however, her thoughts seemed far away, and she did not notice

the little man’s polite efforts. Nettled at her negligence, Mr.

Aeneas was on the point of retiring into his shop, when he saw

Lord George Hell hastening up the street, with a posy of wild

flowers in his hand.

” His lordship is up betimes ! ” he said to himself. ” An early

visit to La Signora, I suppose.”

Not so, however. His lordship came straight towards the

mask-shop. Once he glanced up at the Signora s window and

looked deeply annoyed when he saw her sitting there. He came

quickly into the shop.

” I want the mask of a saint,” he said.

” Mask of a saint, my lord ? Certainly ! ” said Mr. Aeneas,

briskly. “With or without halo ? His Grace the Bishop of St.

Aldreds always wears his with a halo. Your lordship does not

wish for a halo ? Certainly. If your lordship will allow me to

take his measurement—

” I must have the mask to-day,” Lord George said. ” Have

you none ready-made ? ”

” Ah, I see. Required for immediate wear,” murmured Mr.

Aeneas, dubiously. ” You see, your lordship takes a rather large

size.” And he looked at the floor.

” Julius ! ” he cried suddenly to his assistant, who was putting

the finishing touches to a mask of Barbarossa which the youno-

king of Ztirremberg was to wear at his coronation, the following

week. “Julius ! Do you remember the saint’s mask we made

for Mr. Ripsby, a couple of years ago. ”

“Yes,

” Yes, sir,” said the boy. ” It s stored upstairs.”

“I thought so,” replied Mr. Aeneas. ” Mr. Ripsby only had

it on hire. Step upstairs, Julius, and bring it down. I fancy it

is just what your lordship would wish. Spiritual, yet hand-

some.”

“Is it a mask that is even as a mirror of true love?” Lord

George asked, gravely.

” It was made precisely as such,” the mask-maker answered.

” In fact it was made for Mr. Ripsby to wear at his silver wedding,

and was very highly praised by the relatives of Mrs. Ripsby.

Will your lordship step into my little room ?”

So Mr. Aeneas led the way to his parlour behind the shop. He

was elated by the distinguished acquisition to his clientèle, for

hitherto Lord George had never patronised his business. He

bustled round his parlour and insisted that his lordship should take

a chair and a pinch from his snuff-box, while the saint’s mask was

being found.

Lord George’s eye travelled along the rows of framed letters

from great personages, which lined the walls. He did not see

them, though, for he was calculating the chances that La Gambogi

had not observed him, as he entered the mask-shop. He had

come down so early that he had thought she would be still abed.

That sinister old proverb, La jalouse se lève de bonne heure, rose in

his memory. His eye fell unconsciously on a large, round mask

made of dull silver, with the features of a human face traced over

its surface in faint filigree.

“Your lordship wonders what mask that is ?” chirped Mr.

Aeneas, tapping the thing with one of his little finger nails.

“What is that mask ?” Lord George murmured.

” I ought not to divulge, my lord,” said the mask-maker. ” But

I know your lordship would respect a professional secret, a secret

of

of which I am pardonable proud. This,” he said, is a mask for

the sun-god, Apollo, whom heaven bless !

” You astound me,” said Lord George.

” Of no less a person, I do assure you. When Jupiter, his

father, made him lord of the day, Apollo craved that he might

sometimes see the doings of mankind in the hours of night time.

Jupiter granted so reasonable a request. When next Apollo had

passed over the sky and hidden in the sea, and darkness had fallen

on all the world, he raised his head above the waters that he might

watch the doings of mankind in the hours of night time. But,”

Mr. Aeneas added, with a smile, ” his bright countenance made

light all the darkness. Men rose from their couches or from their

revels, wondering that day was so soon come, and went to their

work. And Apollo sank weeping into the sea. Surely, he

cried, it is a bitter thing that I alone, of all the gods, may not

watch the world in the hours of night time. For in those hours,

as I am told, men are even as gods are. They spill the wine and

are wreathed with roses. Their daughters dance in the light ot

torches. They laugh to the sound of flutes. On their long

couches they lie down at last, and sleep comes to kiss their eye

lids. None of these things may I see. Wherefore the bright

ness of my beauty is even as a curse to me and I would put it

from me. And as he wept, Vulcan said to him, I am not the

least cunning of the gods, nor the least pitiful. Do not weep,

for I will give you that which shall end your sorrow. Nor need

you put from you the brightness of your beauty. And Vulcan

made a mask of dull silver and fastened it across his brother’s face.

And that night, thus masked, the sun-god rose from the sea and

watched the doings of mankind in the night time. Nor any

longer were men abashed by his bright beauty, for it was hidden

by the mask of silver. Those whom he had so often seen haggard

over

over their daily tasks, he saw feasting now and wreathed with red

roses. He heard them laugh to the sound of flutes, as their

daughters danced in the red light of torches. And when at

length they lay down upon their soft couches, and sleep kissed

their eyelids, he sank back into the sea and hid his mask under a

little rock in the bed of the sea. Nor have men ever known that

Apollo watches them often in the night time, but fancied it to be

some pale goddess.”

” I myself have always thought it was Diana,” said Lord George

Hell.

” An error, my lord ! ” said Mr. Aeneas, with a smile. ” Ecce

signum ! ” And he tapped the mask of dull silver.

” Strange ! ” said his lordship. ” And pray how comes it that

Apollo has ordered of you this new mask?”

” He has always worn twelve new masks every year, inasmuch

as no mask can endure for many nights the near brightness of his

face, before which even a mask of the best and purest silver soon

tarnishes, and wears away. Centuries ago, Vulcan tired of making

so very many masks. And so Apollo sent Mercury down to

Athens, to the shop of Phoron, a Phoenician mask-maker of great

skill. Phoron made Apollo’s masks for many years, and every

month Mercury came to his shop for a new one. When Phoron

died, another artist was chosen, and when he died, another, and so

on through all the ages of the world. Conceive, my lord, my

pride and pleasure when Mercury flew into my shop, one night

last year, and made me Appolo s warrant-holder. It is the highest

privilege that any mask-maker can desire. And when I die,”

said Mr. Aeneas, with some emotion, ” Mercury will confer my

post upon another.”

” And do they pay you for your labour ? ” Lord George asked.

Mr. Aeneas drew himself up to his full height, such as it was.

“In

“In Olympus, my lord,” he said, “they have no currency. For

any mask-maker, so high a privilege is its own reward. Yet the

sun-god is generous. He shines more brightly into my shop than

into any other. Nor does he suffer his rays to melt any waxen

mask made by me, until its wearer doff it and it be done with.”

At this moment, Julius came in with the Ripsby mask. ” I must

ask your lordship s pardon for having kept you so long,” pleaded

Mr. Aeneas. ” But I have a large store of old masks and they

are imperfectly catalogued.”

It certainly was a beautiful mask, with its smooth, pink cheeks

and devotional brow. It was made of the finest wax. Lord

George took it gingerly in his hands and tried it on his face. It

fitted à merveille.

“Is the expression exactly as your lordship would wish ?” said

Mr. Aeneas.

Lord George laid it on the table and studied it intently. “I

wish it were more as a perfect mirror of true love,” he said at

length. ” It is too calm, too contemplative.”

” Easily remedied ! ” said Mr. Aeneas. Selecting a fine pencil,

deftly he drew the eyebrows closer to each other. With a brush

steeped in some scarlet pigment, he put a fuller curve upon the

lips. And, behold ! it was the mask of a saint who loves dearly.

Lord George s heart throbbed with pleasure.

“And for how long does your lordship wish to wear it ? ” asked

Mr. Aeneas.

” I must wear it until I die,” replied Lord George.

” Kindly be seated then, I pray,” rejoined the little man.

” For I must apply the mask with great care. Julius, you will

assist me ! ”

So, while Julius heated the inner side of the waxen mask over

a little lamp, Mr. Aeneas stood over Lord George, gently smearing

his

his features with some sweet-scented pomade. Then he took the

mask and powdered its inner side, all soft and warm now, with

a fluffy puff. “Keep quite still, for one instant,” he said, and

clapped the mask firmly on his lordship s upturned face. So

soon as he was sure of its perfect adhesion, he took from his

assistant s hand a silver file and a little wooden spatula, with

which he proceeded to pare down the edge of the mask, where it

joined the neck and ears. At length, all traces of the “join”

were obliterated. It remained only to arrange the curls of the

lordly wig over the waxen brow.

The disguise was done. When Lord George looked through

the eyelets of his mask into the mirror that was placed in his

hand, he saw a face that was saintly, itself a mirror of true love.

How wonderful it was ! He felt his past was a dream. He felt

he was a new man indeed. His voice went strangely through the

mask s parted lips, as he thanked Mr. Aeneas.

” Proud to have served your lordship,” said that little worthy,

pocketing his fee of fifty guineas, while he bowed his customer

out.

When he reached the street, Lord George nearly uttered a

curse through those sainted lips of his. For there, right in his

way, stood La Gambogi, holding a small, pink parasol. She laid

her hand upon his sleeve and called him softly by his name. He

passed her by without a word. Again she confronted him.

” I cannot let go so handsome a lover,” she laughed, ” even

though he spurn me ! Do not spurn me, George. Give me

your posy of wild flowers. Why, you never looked so lovingly at

me in all your life ! :

” Madam,” said Lord George, sternly, ” I have not the honour

to know you.” And he passed on.

The lady gazed after her lost lover with the blackest hatred in

her

her eyes. Presently she beckoned across the road to a certain

spy.

And the spy followed him.

Lord George, greatly agitated, had turned into Piccadilly. It

was horrible to have met this garish embodiment of his past on the

very threshold of his fair future. The mask-maker’s elevating

talk about the gods, followed by the initiative ceremony of his

saintly mask, had driven all discordant memories from his love-

thoughts of Jenny Mere. And then to be met by La Gambogi !

It might be that, after his stern words, she would not again

seek to cross his path. Surely she would dare not mar his sacred

love. Yet, he knew her dark, Italian nature, her passion of

revenge. What was the line in Virgil ? Spretaeque—something.

Who knew but that, somehow, sooner or later, she might come

between him and his love ?

He was about to pass Lord Barrymore’s mansion. Count

Karoloffand Mr. FitzClarence were lounging in one of the lower

windows. Would they know him under his mask ? Thank

God, they did not. They merely laughed as he went by, and

Mr. FitzClarence cried in a mocking voice, ” Sing us a hymn,

Mr. Whatever-your-saint’s-name-is ! ; The mask, then, at least,

was perfect. Jenny Mere would not know him. He need fear

no one but La Gambogi. But would not she betray his secret ?

He sighed.

That night he was going to visit Garble’s and to declare his

love to the little actress. He never doubted that she would love

him for his saintly face. Had she not said, u That man whose

face is wonderful as are the faces of the saints, to him I will

give my true love ” ? She could not say now that his face

was as a tarnished mirror of love. She would smile on

him.

him. She would be his bride. But would La Gambogi be at

Garble’s ?

The operette would not be over before ten that night. The

clock in Hyde Park Gate told him it was not yet ten ten o the

morning. Twelve whole hours to wait, before he could fall

at Jenny’s feet ! ” I cannot spend that time in this place of

memories,” he thought. So he hailed a yellow cabriolet and bade

the jarvey drive him out to the village of Kensington.

When they came to the little wood where he had been but a

few hours ago, Lord George dismissed the jarvey. The sun, that

had risen as he stood there thinking of Jenny, shone down on his

altered face. But, though it shone very fiercely, it did not melt his

waxen features. The old woodman, who had shown him his way,

passed by under a load of faggots and did not know him. He

wandered among the trees. It was a lovely wood.

Presently he came to the bank of that tiny stream, the Ken,

which still flowed there in those days. On the moss of its bank

he lay down and let its water ripple over his hand. Some bright

pebble glistened under the surface, and, as he peered down at it, he

saw in the stream the reflection of his mask. A great shame

rilled him that he should so cheat the girl he loved. Behind that

fair mask there would still be the evil face that had repelled her.

Could he be so base as to decoy her into love of that most in

genious deception ? He was filled with a great pity for her, with

a hatred of himself. And yet, he argued, was the mask indeed a

mean trick ? Surely it was a secret symbol of his true repentance

and of his true love. His face was evil, because his life had been

evil. He had seen a gracious girl, and of a sudden his very soul

had changed. His face alone was the same as it had been. It

was not just that his face should be evil still.

There was the faint sound of some one sighing. Lord George

looked

looked up, and there, on the further bank, stood Jenny Mere,

watching him. As their eyes met, she blushed and hung her

head. She looked like nothing but a tall child, as she stood there,

with her straight, limp frock of lilac cotton and her sunburnt

straw bonnet. He dared not speak ; he could only gaze at her.

Suddenly there perched astride the bough of a tree, at her side,

that winged and laughing child, in whose hand was a bow. Be

fore Lord George could warn her, an arrow had flashed down

and vanished in her heart, and Cupid had flown away.

No cry of pain did she utter, but stretched out her arms to her

lover, with a glad smile. He leapt quite lightly over the little

stream and knelt at her feet. It seemed more fitting that he

should kneel before the gracious thing he was unworthy of. But

she, knowing only that his face was as the face of a great saint,

bent over him and touched him with her hand.

“Surely,” she said, “you are that good man for whom I have

waited. Therefore do not kneel to me, but rise and suffer me to

kiss your hand. For my love of you is lowly, and my heart is all

yours.”

But he answered, looking up into her fond eyes, ” Nay, you are

a queen, and I must needs kneel in your presence.”

And she shook her head wistfully, and she knelt down also, in

her tremulous ecstasy, before him. And as they knelt, the one to

the other, the tears came into her eyes, and he kissed her. Though

the lips that he pressed to her lips were only waxen, he thrilled

with happiness, in that mimic kiss. He held her close to him in

his arms, and they were silent in the sacredness of their love.

From his breast he took the posy of wild flowers that he had

gathered.

” They are for you,” he whispered, ” I gathered them for you,

hours ago, in this wood. See ! They are not withered.”

But

But she was perplexed by his words and said to him, blushing,

” How was it for me that you gathered them, though you had

never seen me ? ”

” I gathered them for you,” he answered, ” knowing I should

soon see you. How was it that you, who had never seen me, yet

waited for me ? ”

” I waited, knowing I should see you at last.” And she kissed

the posy and put it at her breast.

And they rose from their knees and went into the wood, walk

ing hand in hand. As they went, he asked the names of the

flowers that grew under their feet. “These are primroses,” she

would say. “Did you not know? And these are ladies feet,

and these forget-me-nots. And that white flower, climbing

up the trunks of the trees and trailing down so prettily from the

branches, is called Astyanax. These little yellow things are

buttercups. Did you not know ? And she laughed.

” I know the names of none of the flowers,” he said.

She looked up into his face and said timidly, “Is it worldly and

wrong of me to have loved the flowers ? Ought I to have

thought more of those higher things that are unseen ? ”

His heart smote him. He could not answer her simplicity.

“Surely the flowers are good, and did not you gather this posy

for me ? ” she pleaded. ” But if you do not love them, I must

not. And I will try to forget their names. For I must try to

be like you in all things.”

” Love the flowers always,” he said. ” And teach me to love

them.”

So she told him all about the flowers, how some grew very

slowly and others bloomed in a night ; how clever the convol

vulus was at climbing, and how shy violets were, and why honey-

cups had folded petals. She told him of the birds, too, that sang

in

in the wood, how she knew them all by their voices. That is

a chaffinch singing. Listen ! ” she said. And she tried to

imitate its note, that her lover might remember. All the birds,

according to her, were good, except the cuckoo, and whenever

she heard him sing she would stop her ears, lest she should for

give him for robbing the nests. ” Every day,” she said, ” I have

come to the wood, because I was lonely, and it seemed to pity

me. But now I have you. And it is glad.”

She clung closer to his arm, and he kissed her She pushed

back her straw bonnet, so that it dangled from her neck by its

ribands, and laid her little head against his shoulder. For a while

he forgot his treachery to her, thinking only of his love and her

love. Suddenly she said to him, ” Will you try not to be angry

with me, if I tell you something ? It is something that will seem

dreadful to you.”

” Pauvrette” he answered, “you cannot have anything very

dreadful to tell.”

“I am very poor,” she said, “and every night I dance in a

theatre. It is the only thing I can do to earn my bread. Do

you despise me because I dance ? She looked up shyly at him

and saw that his face was full of love for her and not angry.

” Do you like dancing ? ” he asked.

“I hate it,” she answered, quickly. “I hate it indeed. Yet

to-night, alas ! I must dance again in the theatre.”

” You need never dance again,” said her lover. ” I am rich

and I will pay them to release you. You shall dance only for me.

Sweetheart, it cannot be much more than noon. Let us go

into the town, while there is time, and you shall be made my bride,

and I your bridegroom, this very day. Why should you and I be

lonely ? ”

” I do not know,” she said.

So

So they walked back through the wood, taking a narrow path

which Jenny said would lead them quickest to the village. And,

as they went, they came to a tiny cottage, with a garden that was

full of flowers. The old woodman was leaning over its paling,

and he nodded to them as they passed.

“I often used to envy the woodman,” said Jenny, “living in

that dear little cottage.”

” Let us live there, then,” said Lord George. And he went

back and asked the old man if he were not unhappy, living there

all alone.

” Tis a poor life here for me,” the old man answered. ” No

folk come to the wood, except little children, now and again, to

play, or lovers like you. But they seldom notice me. And in

winter I am alone with Jack Frost. Old men love merrier com-

pany than that. Oh ! I shall die in the snow with my faggots on

my back. A poor life here ? ”

” I will give you gold for your cottage and whatever is in it,

and then you can go and live happily in the town,” Lord George

said. And he took from his coat a note for two hundred guineas,

and held it across the palings.

“Lovers are poor, foolish derry-docks,” the old man muttered.

“But I thank you kindly, sir. This little sum will keep me

finely, as long as I last. Come into the cottage as soon as soon

can be. It s a lonely place and does my heart good to depart

from it.”

“We are going to be married this afternoon, in the town,”

said Lord George. ” We will come straight back to our

home.”

” May you be happy ! ” replied the woodman. ” You ll find me

gone when you come.”

And the lovers thanked him and went their way.

“Are

“Are you very rich?” Jenny asked. “Ought you to have

bought the cottage for that great price ?

“Would you love me as much if I were quite poor, little

Jenny ? ” he asked her, after a pause.

” I did riot know you were rich when I saw you across the stream,” she said.

And in his heart Lord George made a good resolve. He would

put away from him all his worldly possessions. All the money

that he had won at the clubs, fairly or foully, all that hideous

accretion of gold guineas, he would distribute among the comrades

he had impoverished. As he walked, with the sweet and trustful

girl at his side, the vague record of his infamy assailed him, and a

look of pain shot behind his smooth mask. He would atone. He

would shun no sacrifice that might cleanse his soul. All his

fortune he would put from him. Follard Chase he would give

back to poor Sir Follard. He would sell his house in St. James’s

Square. He would keep some little part of his patrimony, enough

for him in the wood with Jenny, but no more.

“I shall be quite poor, Jenny,” he said.

And they talked of the things that lovers love to talk of, how

happy they would be together and how economical. As they were

passing Herbert’s pastry-shop, which, as my little readers know,

still stands in Kensington, Jenny looked up rather wistfully into

her lover s ascetic face.

” Should you think me greedy,” she asked him, ” if I wanted a

bun ? They have beautiful buns here ! ”

Buns ! The simple word started latent memories of his child

hood. Jenny was only a child, after all. Buns ! He had for

gotten what they were like. And as they looked at the piles of

variegated cakes in the window, he said to her, ” Which are buns,

Jenny ? I should like to have one, too.”

“I am

” I am almost afraid of you,” she said. ” You must despise me

so. Are you so good that you deny yourself all the vanity and

pleasure that most people love ? It is wonderful not to know

what buns are ! The round, brown, shiny cakes, with little raisins

in them, are buns.”

So he bought two beautiful buns, and they sat together in the

shop, eating them. Jenny bit hers rather diffidently, but was

reassured when he said that they must have buns very often in the

cottage. Yes ! he, the famous toper and gourmet of St. James’s,

relished this homely fare, as it passed through the insensible lips of

his mask to his palate. He seemed to rise, from the consumption

of his bun, a better man.

But there was no time to lose now. It was already past two

o clock. So he got a chaise from the inn opposite the pastry-shop,

and they were driven swiftly to Doctors’ Commons. There he

purchased a special license. When the clerk asked him to write

his name upon it, he hesitated. What name should he assume ?

Under a mask he had wooed this girl, under an unreal name he

must make her his bride. He loathed himself for a trickster. He

had vilely stolen from her the love she would not give him. Even

now, should he not confess himself the man whose face had

frightened her, and go his way ? And yet, surely, it was not

just that he, whose soul was transfigured, should bear his old name.

Surely George Hell was dead, and his name had died with him. So

he dipped a pen in the ink and wrote ” George Heaven,” for want

of a better name. And Jenny wrote ” Jenny Mere ” beneath it.

An hour later they were married according to the simple rites

of a dear little registry office in Covent Garden.

And in the cool evening they went home.

In the cottage that had been the woodman s they had a wonderful

The Yellow Book Vol. XI. C

honeymoon.

honeymoon. No king and queen in any palace of gold were

happier than they. For them their tiny cottage was a palace, and

the flowers that filled the garden were their courtiers. Long and

careless and full of kisses were the days of their reign.

Sometimes, indeed, strange dreams troubled Lord George’s

sleep. Once he dreamt that he stood knocking and knocking at

the great door of a castle. It was a bitter night. The frost

enveloped him. No one came. Presently he heard a footstep in

the hall beyond, and a pair of frightened eyes peered at him through

the grill. Jenny was scanning his face. She would not open to

him. With tears and wild words he beseeched her, but she would

not open to him. Then, very stealthily, he crept round the castle

and found a small casement in the wall. It was open. He

climbed swiftly, quietly through it. In the darkness of the room,

some one ran to him and kissed him gladly. It was Jenny.

With a cry of joy and shame he awoke. By his side lay Jenny,

sleeping like a little child.

After all, what was a dream to him ? It could not mar the

reality of his daily happiness. He cherished his true penitence for

the evil he had done in the past. The past ! That was indeed

the only unreal thing that lingered in his life. Every day its

substance dwindled, grew fainter yet, as he lived his rustic honey

moon. Had he not utterly put it from him ? Had he not, a few

hours after his marriage, written to his lawyer, declaring solemnly

that he, Lord George Hell, had forsworn the world, that he was

where no man would find him, that he desired all his worldly

goods to be distributed, thus and thus, among these and those of

his companions ? By this testament he had verily atoned for the

wrong he had done, had made himself dead indeed to the world.

No address had he written upon this document. Though its

injunctions were final and binding, it could betray no clue of his

hiding-place.

hiding-place. For the rest, no one would care to seek him out.

He, who had done no good to human creature, would pass

unmourned out of memory. The clubs, doubtless, would laugh

and puzzle over his strange recantations, envious of whomever he

had enriched. They would say ’twas a good riddance of a rogue

and soon forget him.* But she, whose prime patron he had

* I would refer my little readers once more to the pages of

Contemporary Bucks, where Captain Tarleton speculates upon the

sudden disappearance of Lord George Hell and describes its effect

on the town. ” Not even the shrewdest,” says he, ” ever gave a guess

that would throw a ray of revealing light on the disparition of this

profligate man. It was supposed that he carried off with him a little

dancer from Garble’s, at which haunt of pleasantry he was certainly on

the night he vanished, and whither the young lady never returned

again. Garble declared he had been compensated for her perfidy, but

that he was sure she had not succumbed to his lordship, having in

fact rejected him soundly. Did his lordship, say the cronies, take

his life—and hers ? Il n’y a pas d’epreuve. The most astonishing

matter is that the runaway should have written out a complete will,

restoring all money he had won at cards, etc. etc. This certainly

corroborates the opinion that he was seized with a sudden repentance

and fled over the seas to a foreign monastery, where he died at last in

religious silence. That’s as it may, but many a spendthrift found his

pocket chinking with guineas, a not unpleasant sound, I declare. The

Regent himself was benefited by the odd will, and old Sir Follard

Follard found himself once more in the ancestral home he had for-

feited. As for Lord George’s mansion in St. James’s Square, that was

sold with all its appurtenances, and the money fetched by the sale, no

bagatelle, was given to various good objects, according to my lord’s

stated wishes. Well, many of us blessed his name—we had cursed it

often enough. Peace to his ashes, in whatever urn they be resting, on

the billows of whatever ocean they float ! ”

been,

been, who had loved him in her vile fashion, La Gambogi, would

she forget him easily, like the rest ? As the sweet days went by,

her spectre, also, grew fainter and less formidable. She knew his

mask indeed, but how should she find him in the cottage near

Kensington ? Devia dulcedo latebrarum ! He was safe hidden

with his bride. As for the Italian, she might search and search—

or had forgotten him, in the arms of another lover.

Yes ! Few and faint became the blemishes of his honeymoon.

At first, he had felt that his waxen mask, though it had been the

means of his happiness, was rather a barrier ‘twixt him and his

bride. Though it was sweet to kiss her through it, to look at her

through it with loving eyes, yet there were times when it incom=

moded him with its mockery. Could he but put it from him!

yet, that, of course, could not be. He must wear it all his life.

And so, as days went by, he grew reconciled to his mask. No

longer did he feel it jarring on his face. It seemed to become

an integral part of him, and, for all its rigid material, it did

forsooth express the one emotion that filled him, true love. The

face, for whose sake Jenny gave him her heart, could not but be

dear to this George Heaven, also.

Every day chastened him with its joy. They lived a very

simple life, he and Jenny. They rose betimes, like the birds, for

whose goodness they both had so sincere a love. Bread and

honey and little strawberries were their morning fare, and in the

evening they had seed cake and dewberry wine. Jenny herself

made the wine, and her husband drank it, in strict moderation,

never more than two glasses. He thought it tasted far better

than the Regent’s cherry brandy, or the Tokay at Brooks’s. Of

these treasured topes he had, indeed, nearly forgotten the taste.

The wine made from wild berries by his little bride was august

enough for his palate. Sometimes, after they had dined thus

he

he would play the flute to her upon the moonlit lawn, or tell

her of the great daisy-chain he was going to make for her

on the morrow, or sit silently by her side, listening to the

nightingale, till bedtime. So admirably simple were their

days.

One morning, as he was helping Jenny to water the flowers,

he said to her suddenly, ” Sweetheart, we had forgotten ! ”

” What was there we should forget ? ” asked Jenny, looking

up from her task.

” Tis the mensiversary of our wedding,” her husband answered,

gravely. ” We must not let it pass without some celebration.”

” No, indeed,” she said, ” we must not. What shall we

do ? ”

Between them they decided upon an unusual feast. They

would go into the village and buy a bag of beautiful buns and eat

them in the afternoon. So soon, then, as all the flowers were

watered, they set forth to Herbert s shop, bought the buns and re-

turned home in very high spirits, George bearing a paper bag that

held no less than twelve of the wholesome delicacies. Under the

plane tree on the lawn Jenny sat her down, and George stretched

himself at her feet. They were loth to enjoy their feast too soon.

They dallied in childish anticipation. On the little rustic table

Jenny built up the buns, one above another, till they looked like

a tall pagoda. When, very gingerly, she had crowned the struc-

ture with the twelfth bun, her husband looking on with admira-

tion, she clapped her hands and danced round it. She laughed so

loudly (for, though she was only sixteen years old, she had a great

sense of humour), that the table shook, and, alas ! the pagoda

tottered and fell to the lawn. Swift as a kitten, Jenny chased the

buns, as they rolled, hither and thither, over the grass, catching

them

them deftly with her hand. Then she came back, flushed and

merry under her tumbled hair, with her arm full of buns. She

began to put them back in the paper bag.

” Dear husband,” she said, looking timidly down to him, ” why

do not you smile too at my folly ? Your grave face rebukes me.

Smile, or I shall think I vex you. Please smile a little.”

But the mask could not smile, of course. It was made for a

mirror of true love, and it was grave and immobile. ” I am very

much amused, dear,” he said, ” at the fall of the buns, but my lips

will not curve to a smile. Love of you has bound them in

spell.”

” But I can laugh, though I love you. I do not understand.”

And she wondered. He took her hand in his and stroked it

gently, wishing it were possible to smile. Some day, perhaps, she

would tire of his monotonous gravity, his rigid sweetness. It was

not strange that she should long for a little facial expression.

They sat silently.

“Jenny, what is it?” he whispered, suddenly. For Jenny,

with wide-open eyes, was gazing over his head, across the lawn.

” Why do you look frightened ? ”

” There is a strange woman smiling at me across the palings,”

she said. ” I do not know her.”

Her husband s heart sank. Somehow, he dared not turn his

head to the intruder. He dreaded who she might be.

” She is nodding to me,” said Jenny. ” I think she is foreign,

for she has an evil face.”

” Do not notice her,” he whispered. ” Does she look evil ? ”

” Very evil and very dark. She has a pink parasol. Her teeth

are like ivory.”

“Do not notice her. Think ! It is the mensiversary of our

wedding, dear ! ”

“I wish

” I wish she would not smile at me. Her eyes are like bright

blots of ink.”

“Let us eat our beautiful buns ! ”

” Oh, she is coming in ! ” George heard the latch of the gate

jar. ” Forbid her to come in ! ” whispered Jenny, ” I am afraid ! ”

He heard the jar of heels on the gravel path. Yet he dared

not turn. Only he clasped Jenny s hand more tightly, as he

waited for the voice. It was La Gambogi’s.

” Pray, pray, pardon me ! I could not mistake the back of so

old a friend.”

With the courage of despair, George turned and faced the

woman.

” Even,” she smiled, ” though his face has changed marvel-

lously.”

” Madam,” he said, rising to his full height and stepping

between her and his bride, ” begone, I command you, from this

garden. I do not see what good is to be served by the renewal of

our acquaintance.”

“Acquaintance!” murmured La Gambogi, with an arch of

her beetle-brows. ” Surely we were friends, rather, nor is my

esteem for you so dead that I would crave estrangement.”

” Madam,” rejoined Lord George, with a tremor in his voice,

” you see me here very happy, living very peacefully with my

bride—”

” To whom, I beseech you, old friend, present me.”

” I would not,” he said hotly, ” desecrate her sweet name by

speaking it with so infamous a name as yours.”

” Your choler hurts me, old friend,” said La Gambogi, sinking

composedly upon the garden-seat and smoothing the silk of her

skirts.

“Jenny,” said George, ” then do you retire, pending this lady’s

departure,

departure, to the cottage.” But Jenny clung to his arm.

were less frightened at your side,” she whispered. ” Do not send

me away ! ”

“Suffer her pretty presence,” said La Gambogi. “Indeed I am

come this long way from the heart of the town, that I may see

her, no less than you, George. My wish is only to befriend her.

Why should she not set you a mannerly example, giving me

welcome? Come and sit by me, little bride, for I have things

to tell you. Though you reject my friendship, give me, at least,

the slight courtesy of audience. I will not detain you overlong,

will be gone very soon. Are you expecting guests, George ?

On dirait une masque champêtre ! ” She eyed the couple critic-

ally. “Your wife’s mask,” she said, “is even better than

yours.”

“What does she mean ? ” whispered Jenny. “Oh, send her

away !

“Serpent,” was all George could say, “crawl from our Eden,

ere you poison with your venom its fairest denizen.”

La Gambogi rose. ” Even my pride,” she cried passionately,

” knows certain bounds. I have been forbearing, but even in my

zeal for friendship I will not be called serpent. I will indeed

begone from this rude place. Yet, ere I go, there is a boon I

will deign to beg. Show me, oh show me but once again, the

dear face I have so often caressed, the lips that were dear to

me !”

George started back.

” What does she mean ? ” whispered Jenny.

” In memory of our old friendship,” continued La Gambogi,

” grant me this piteous favour. Show me your own face but for

one instant, and I vow I will never again remind you that I

live. Intercede for me, little bride. Bid him unmask for me.

You

You have more authority over him than I. Doff his mask with

your own uxorious ringers.”

” What does she mean ? ” was the refrain of poor Jenny.

” If,” said George, gazing sternly at his traitress, ” you do not

go now, of your own will, I must drive you, man though I am,

violently from the garden.”

“Doff your mask and I am gone.”

George made a step of menace towards her.

” False saint ! ” she shrieked, ” then I will unmask you.”

Like a panther she sprang upon him and clawed at his waxen

cheeks. Jenny fell back, mute with terror. Vainly did George

try to free himself from the hideous assailant, who writhed round

and round him, clawing, clawing at what Jenny fancied to be his

face. With a wild cry, Jenny fell upon the furious creature and

tried, with all her childish strength, to release her dear one. The

combatives swayed to and fro, a revulsive trinity. There was a

loud pop, as though some great cork had been withdrawn, and La

Gambogi recoiled. She had torn away the mask. It lay before

her upon the lawn, upturned to the sky.

George stood motionless. La Gambogi stared up into his face,

and her dark flush died swiftly away. For there, staring back at

her, was the man she had unmasked, but, lo ! his face was even as

his mask had been. Line for line, feature for feature, it was the

same. ‘Twas a saint’s face.

” Madam,” he said, in the calm voice of despair, ” your cheek

may well blanch, when you regard the ruin you have brought

upon me. Nevertheless do I pardon you. The gods have

avenged, through you, the imposture I wrought upon one who

was dear to me. For that unpardonable sin I am punished. As

for my poor bride, whose love I stole by the means of that waxen

semblance, of her I cannot ask pardon. Ah, Jenny, Jenny do

not

not look at me. Turn your eyes from the foul reality that I

dissembled.” He shuddered and hid his face in his hands. ” Do

not look at me. I will go from the garden. Nor will I ever

curse you with the odious spectacle of my face. Forget me,

forget me.”

But, as he turned to go, Jenny laid her hands upon his wrists

and besought him that he would look at her. ” For indeed,” she

said, ” I am bewildered by your strange words. Why did you

woo me under a mask ? And why do you imagine I could love

you less dearly, seeing your own face ? ”

He looked into her eyes. On their violet surface he saw the

tiny reflection of his own face. He was filled with joy and

wonder.

” Surely,” said Jenny, ” your face is even dearer to me, even

fairer, than the semblance that hid it and deceived me. I am not

angry. Twas well that you veiled from me the full glory of your

face, for indeed I was not worthy to behold it too soon. But I

am your wife now. Let me look always at your own face. Let

the time of my probation be over. Kiss me with your own

lips.”

So he took her in his arms, as though she had been a little

child, and kissed her with his own lips. She put her arms round

his neck, and he was happier than he had ever been. They were

alone in the garden now. Nor lay the mask any longer upon the

lawn, for the sun had melted it.

A Ballad of Cornwall

By F. B. Money Coutts

I

SIR Tristram lay by a well,

Making sad moan ;

Fast his tears fell,

For wild the wood through,

Stricken with shrewd

Sorrow, he ran,

When he deemed her untrue—

La Beale Isoud !

For he loved her alone.

So as he lay,

Wasted and wan,

Scarce like a man,

Pricking that way

His lady-love came,

With her damsels around,

And her face all a-flame

With the breezes of May ;

While

While a brachet beside her

Still bayed the fair rider,

Still leaped up and bayed her ;

A small scenting hound

That Sir Tristram purveyed her.

So she rode on ;

But the brachet behind

Hung snuffing the wind,

Till seeking and crying

Faster and faster,

Beside the well lying

She found her dear master !

Then licking his ears

And cheeks wet with tears,

For joy never resting

Kept whining and questing.

Isoud (returned,

Seeking her hound)

Soon as she learned

Tristram was found,

Straightway alighting,

Fell in a swound.

Won by her lover

Thence to recover,

Who

Who shall the greeting

Tell of their meeting ?

Joy, by no tongue

E’er to be sung,

Passed in that plighting !

Thus while they dallied,

Forth the wood sallied

An horrible libbard, and bare

The brachet away to his lair !

The Friend of Man

THE other evening, in the Casino, the satisfaction of losing

my money at petits-chevaux having begun to flag a little,

I wandered into the Cercle, the reserved apartments in the

west wing of the building, where they were playing baccarat.

Thanks to the heat, the windows were open wide ; and

through them one could see, first, a vivid company of men and

women, strolling backwards and forwards, and chattering busily,

in the electric glare on the terrace ; and then, beyond them, the

sea—smooth, motionless, sombre ; silent, despite its perpetual

whisper ; inscrutable, sinister ; merging itself with the vast black

ness of space. Here and there the black was punctured by a

pin-point of fire, a tiny vacillating pin-point of fire ; and a lands-

man’s heart quailed for a moment at the thought of lonely vessels

braving the mysteries and terrors and the awful solitudes of the

sea at night. . . .

So that the voice of the croupier, perfunctory, machine-like,

had almost a human, almost a genial effect, as it rapped out

suddenly, calling upon the players to mark their play. ” Marquez

vosjeux, messieurs. Quarante louis par tableau.” It brought one

back to light and warmth and security, to the familiar earth, and

the neighbourhood of men.

One’s

One’s pleasure was fugitive, however.

The neighbourhood of men, indeed ! The neighbourhood of

some two score very commonplace, very sordid men, seated or

standing about an ugly green table, intent upon a game of

baccarat, in a long, rectangular, ugly, gas-lit room. The banker

dealt, and the croupier shouted, and the punters punted, and

the ivory counters and mother-of-pearl plaques were swept now

here, now there ; and that was all. Everybody was smoking, of

course ; but the smell of the live cigarettes couldn’t subdue the

odour of dead ones, the stagnant, acrid odour of stale tobacco, with

which the walls and hangings of the place were saturated.

The thing and the people were as banale, as unremunerative,

as things and people for the most part are ; and dispiriting,

dispiriting. There was a hardness in the banality, a sort of

cold ferocity, ill-repressed. One turned away, bored, revolted.

It was better, after all, to look at the sea ; to think of the lonely

vessel, far out there, where a pin-point of fire still faintly blinked

and glimmered in the illimitable darkness

But the voice of the croupier was insistent. ” Faites vos jeux,

messieurs. Cinquante louis par tableau. Vos jeux sont faits ?

Rien ne va plus.” It was suggestive, persuasive, besides, to one

who has a bit of a gambler’s soul. I saw myself playing, I felt

the poignant tremor of the instant of suspense, while the result is

uncertain, the glow that comes if you have won, the twinge if

you have lost. ” La banque est aux enchères,” the voice

announced presently ; and I moved towards the table.

The sums bid were not extravagant. Ten, fifteen, twenty

louis ; thirty, fifty, eighty, a hundred.

” Cent louis ? Cent ? Cent ?—Cent louis à la banque,” cried

the inevitable voice.

I glanced

I glanced at the man who had taken the bank for a hundred

louis. I glanced at him, and, all at oncv=, by no means without

emotion, I recognised him.

He was a tall, thin man, and very old. He had the hands of a

very old man, dried-up, shrunken hands, with mottled-yellow skin,

dark veins that stood out like wires, and parched finger-nails.

His face, too, was mottled-yellow, deepening to brown about the

eyes, with grey wrinkles, and purplish lips. He was clearly very

old ; eighty, or more than eighty.

He was dressed entirely in black : a black frock-coat, black

trousers, a black waistcoat, cut low, and exposing an unusual

quantity of shirt-front, three black studs, and a black tie, a stiff,

narrow bow. These latter details, however, save when some

chance motion on his part revealed them, were hidden by his

beard, a broad, abundant beard, that fell a good ten inches down

his breast. His hair, also, was abundant, and he wore it long ;

trained straight back from his forehead, hanging in a fringe about

the collar of his coat. Hair and beard, despite his manifest

great age, were without a spear of white. They were of a dry,

inanimate brown, a hue to which they had faded (one surmised)

from black.

If it was surprising to see so old a man at a baccarat table, it

was still more surprising to see just this sort of man. He looked

like anything in the world, rather than a gambler. With his tall

wasted figure, with his patriarchal beard, his long hair trained in

that rigid fashion straight back from his forehead ; with his stern

aquiline profile, his dark eyes, deep-set and wide-apart, melancholy,

thoughtful : he looked—what shall I say ? He looked like

The Yellow Book—Vol. XI. D

anything

anything in the world, rather than a gambler. He looked like a

savant, he looked like a philosopher ; he looked intellectual,

refined, ascetic even ; he looked as if he had ideas, convictions ;

he looked grave and wise and sad. Holding the bank at baccarat,

in this vulgar company at the Grand Cercle of the Casino, dealing

the cards with his withered hand?, studying them with his deep

meditative eyes, he looked improbable, inadmissible, he looked

supremely out of place.

I glanced at him, and wondered. And then, suddenly, my

heart gave a jump, my throat began to tingle.

I had recognised him. It was rather more than ten years since

I had seen him last ; and in ten years he had changed, he had

decayed terribly. But I was quite sure, quite sure.

” By Jove,” I thought, ” it’s Ambrose—it’s Augustus Ambrose !

It’s the Friend of Man ! ”

Augustus Ambrose ? I daresay the name conveys nothing to

you ? And yet forty, thirty, twenty years ago, Augustus Ambrose

was not without his measure of celebrity in the world. If almost

nobody had read his published writings, if few had any but the

dimmest notion of what his theories and aims were, almost every-

body had at least heard of him, almost everybody knew at least

that there was such a man, and that the man had theories and

aims—of some queer radical sort. One knew, in vague fashion,

that he had disciples, that there were people here and there who

called themselves ” Ambrosites.”

I say twenty years ago. But twenty years ago he was already

pretty well forgotten. I imagine the moment of his utmost

notoriety would have fallen somewhere in the fifties or the sixties,

somewhere between ’55 and ’68.

And

And if my sudden recognition of him in the Casino made my

heart give a jump, there was sufficient cause. During the greater

part of my childhood, Augustus Ambrose lived with us, was

virtually a member of our family. Then I saw a good deal of him

again, when I was eighteen, nineteen ; and still again, when I was

four or five and twenty.

He lived with us, indeed, from the time when I was scarcely

more than a baby till I was ten or eleven ; so that in my very

farthest memories he is a personage—looking backwards, I see

him in the earliest, palest dawn : a tall man, dressed in black,

with long hair and a long beard, who was always in our house,

and who used to be frightfully severe ; who would turn upon me

with a most terrifying frown if I misconducted myself in his

presence, who would loom up unexpectedly from behind closed

doors, and utter a soul-piercing hist-hist, if I was making a noise :

a sort of domesticated Croquemitaine, whom we had always

with us.

Always ? Not quite always, though ; for, when I stop to

think, I remember there would be breathing spells : periods during

which he would disappear—during which you could move about

the room, and ask questions, and even (at a pinch) upset things,

without being frowned at ; during which you could shout lustily

at your play, unoppressed by the fear of a black figure suddenly

opening the door and freezing you with a hist-hist ; during

which, in fine, you could forget the humiliating circumstance that

children are called into existence to be seen and not heard, with

its irksome moral that they should never speak unless they are

spoken to. Then, one morning, I would wake up, and find that

he was in the house again. He had returned during the night.

That

That was his habit, to return at night. But on one occasion,

at least, he returned in the daytime. I remember driving with

my father and mother, in our big open carriage, to the railway

station, and then driving back home, with Mr. Ambrose added to

our party. Why I—a child of six or seven, between whom and

our guest surely no love was lost—why I was taken upon this

excursion, I can’t at all conjecture ; I suppose my people had

their reasons. Anyhow, I recollect the drive home with particular

distinctness. Two things impressed me. First, Mr. Ambrose,

who always dressed in black, wore a brown overcoat ; I remember

gazing at it with bemused eyes, and reflecting that it was exactly

the colour of gravy. And secondly, I gathered from his conversa-

tion that he had been in prison ! Yes. I gathered that he had

been in Rome (we were living in Florence), and that one day he

had been taken up by the policemen, and put in prison !

Of course, I could say nothing ; but what I felt, what I

thought ! Mercy upon us, that we should know a man, that a

man should live with us, who had been taken up and put in