XML PDF

Critical Introduction to The Venture:

An Annual of Art and Literature Volume 2 (1905)

The second volume of The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature came out in late November 1904, forward dated 1905 in accordance with Victorian publishing practice for seasonal gift books. Forward dating maximized sales potential by allowing a publisher to announce the same title as “new” two years running. The Venture’s publisher, New Zealand-born artist and London-based gallery owner John Baillie (1868-1926), was no doubt hoping for improved sales, since he conducted his magazine “on the profit-sharing system” (Housman, Unexpected, 202). Despite positive reviews, the first Venture had not garnered any profit. Unsurprisingly, given their lack of reimbursement, few contributors— including co-editors Laurence Housman (1865-1959) and W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1965)— continued their connection with the annual into the second volume. The novice publisher consequently assumed editing responsibilities for The Venture’s literary contents in addition to its artworks. This must have been a demanding time commitment, given the regular exhibition schedule Baillie maintained at his Art Gallery in Bayswater, coupled with his decision to publish another title that year as well, The Dream-Garden: A Children’s Annual, edited by Netta Syrett (1865-1943). Although contributors were not paid for their submissions to either title (Housman, Unexpected, 202; Syrett, Sheltering, 148), Baillie’s financial outlay to cover production costs must have been considerable. To compensate for this expenditure, Baillie raised the price of The Venture from five shillings to seven shillings sixpence.

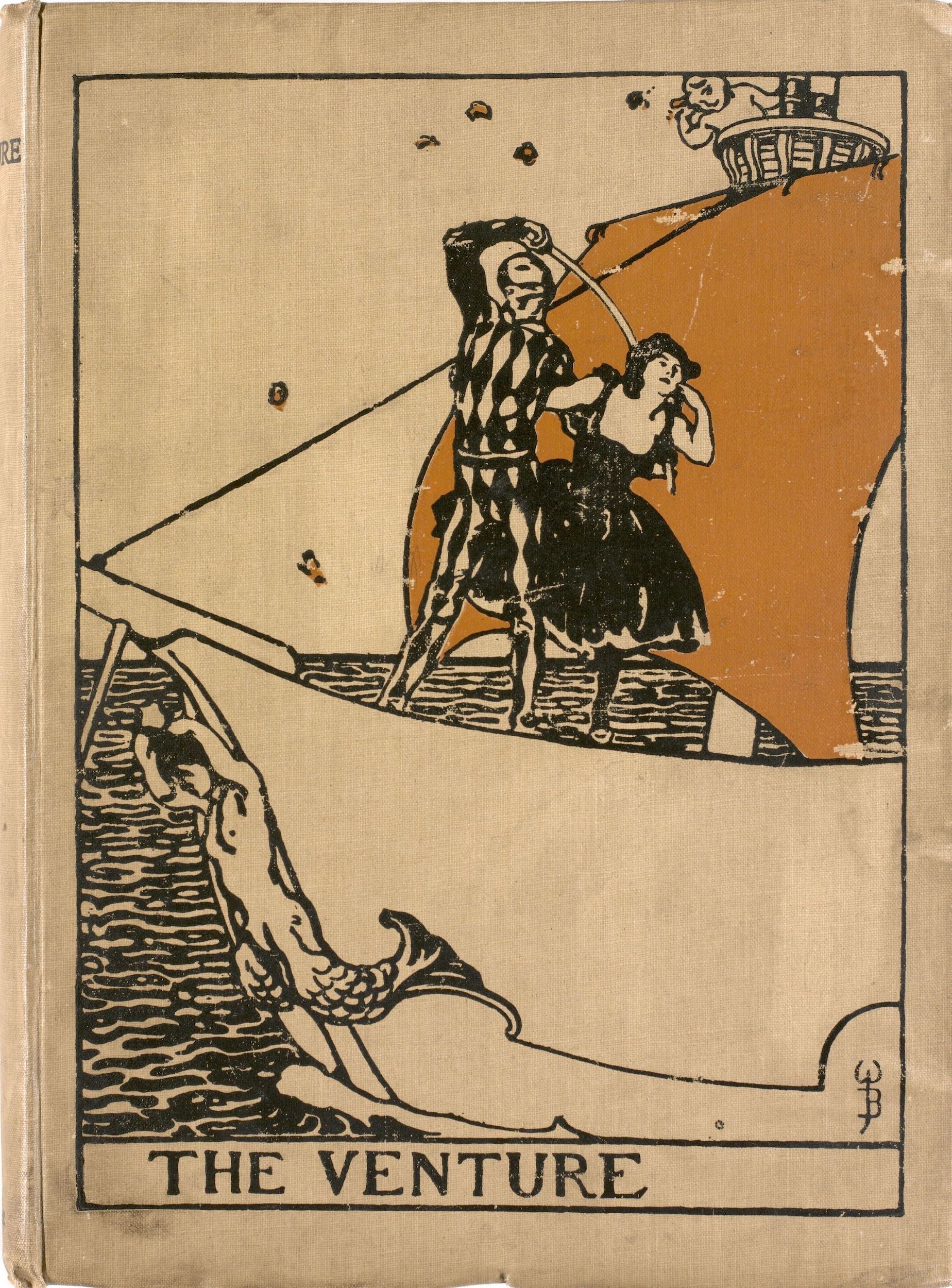

The Bookman summarized Baillie’s magazine as “an annual of art and literature…as clever throughout as its decorated and decorative covers would lead one to hope” (“Notes,” 181). Hardbound in buff-coloured grosgrain cloth with a black-and-orange cover design, The Venture had decorative endpapers printed in soft green, a rubricated title page, and numerous illustrations, some of them in colour. The crown quarto of 188 pages included 24 works of art and 34 pieces of literature by both well-known and up-and-coming artists and authors. The first volume, by contrast, had included only 15 works of art and 22 pieces of literature, about 20% supplied by female contributors. To maintain this percentage in the second volume while increasing the overall number of items, Baillie almost doubled the total number of women artists and authors (from 6 to 11). As he was in his Gallery, Baillie was committed to showcasing work by women in his annual. Notably, the ratio of female to male contributors in The Venture is unusually high for late-Victorian little magazines, particularly with respect to visual contents. The Yellow Book (1894-97), for example, published 70 pictures in its first year of publication; only one was by a woman, Margaret L. Sumner (dates unknown). In its entire print run of eight issues, The Savoy (1896) included a single woman artist, Mabel Dearmer (1872-1915). Neither The Dial (1889-1897) nor The Pageant (1896-97) published art by women. Like The Evergreen (1895-96) and The Green Sheaf (1903-4), The Venture is important to periodicals scholarship and the history of art for its inclusion of women artists.

Reviewers praised the high quality of Baillie’s editorial selections and celebrated The Venture’s important place in the late-Victorian little magazine movement. Noting that “Les Jeunes, since the prolific nineties, have had few shows of this sort,” the Athenaeum “congratulate[d] Mr. Baillie on his enterprise in continuing” the tradition inaugurated by the innovative periodicals of the previous decade (Rev. of The Venture, 805). The Bookman made an even more direct link, suggesting that “The ‘Yellow Book’…would seem to have come back to us under the title of The Venture.” While commending both the visual and verbal contents, this critic focused especially on the volume’s artwork: “It is a matter for praise when an attempt is made to bring within general reach a collection of careful and admirable art” (“Notes,” 181). It is not surprising that The Venture’s art contents should be singled out in this way. In his capacity as art editor, Baillie leveraged the annual’s potential as a portable art gallery, featuring many of the unconventional artists represented in his showroom. In this way, The Venture uniquely brought London’s exhibition and print cultures together.

In contrast to the first volume of The Venture, which restricted its art contents to original wood engravings that could be printed on the same hand press as the texts (see Introduction to The Venture, vol. 1), the second included a wide variety of artistic media. Aiming to reproduce each type of image optimally in print, Baillie employed four different reproduction companies. In addition to providing photomechanical line blocks for all black-and-white drawings, the highly regarded firm of Messrs Carl Hentschel and Co. supplied the colour block for the volume’s frontispiece, a facsimile of James McNeill Whistler’s “Arrangement in Brown and Gold.” The Rembrandt Intaglio Co. produced photogravures of tonal artwork such as paintings. Messrs T. Brooker and Co. printed the etchings and Messrs J. Miles and Co. printed the lithographs (Colophon, [viii]).

The textual contents were printed in Leamington by the Arden Press, directed by Bernard Newdigate (1869-1944) and his father Alfred (1829-1923). The firm also had a small shop front in the shadow of London’s Westminster Cathedral; given its origin as a private press founded by a Benedictine monk in 1880, this was an apt location. Originally called St. Gregory’s Press, it was renamed the Arden Press in 1904 (Page 264). Joseph Thorp (1873-1962), the former Catholic priest turned letterpress printer, who met and married artist Nellie Syrett (1874-1970) in the process of producing Baillie’s Dream-Garden, claimed to have suggested the new name. Thorp averred that printing at the Arden Press “was more distinguished aesthetically than any in England, except perhaps that of the Chiswick Press under [Charles] Jacobi” (Thorp 86). Baillie seems to have agreed. When he selected the Arden Press for his two annuals of 1905, Baillie described Thorp to Dream Garden editor Netta Syrett (sister of Nellie, who designed the cover and contributed the coloured frontispiece) as a printer “then making a special study of the art of beautiful printing” (Syrett, Sheltering 148). Volume 2 of The Venture is, indeed, an outstanding example of the period’s “book beautiful.” Thorp was mentored in his craft by Emery Walker (1851-1933), whose lecture on typography at London’s first Arts and Crafts Exhibition in 1888 was one of the inspirations for the fin-de-siècle’s fine-printing revival and little magazine movement. Walker’s influence is evident across the titles on the Y90s Magazine Rack, from the first Dial in 1889 to the last Venture in 1905.

From its eye-catching cover to its interior contents, The Venture’s second volume attests not only to the close relationship between Baillie’s showroom and his annual, but also to their shared intermedial connection with alternative theatre. Baillie strategically used the Venture cover to foreground work by one of his Gallery’s artists, Walter Bayes (1869-1956), whose exhibition that September had included a significant group of pastels featuring Harlequin and Columbine. In the Victorian Harlequinade that developed from the sixteenth-century Italian Commedia dell’Arte, the love scene between these stock figures had been reduced to a brief epilogue to the pantomime (“Harlequinade,” np). However, as theatrical historian James Fisher shows, the Harlequinade became an important aesthetic undercurrent, as “artists … seeking alternatives to the tidal wave of realism and naturalism sweeping the early twentieth-century theatre” turned to the commedia “to revivify modern” drama (Fisher 30).

Baillie’s support of alternative theatre brought exhibition, print, and performance cultures together from the edges of London’s Bayswater. In the first year of operating his Gallery, Baillie provided an alternative box office service for playwright Laurence Housman and designer E. Gordon Craig’s production of Bethlehem (1902), which had been refused a licence by the censor (see Introduction to The Venture, vol. 1). Notably, Craig and Housman, two of the most significant proponents of the Harlequinade revival, were both Venture contributors and Baillie Gallery exhibitors. The energetic Craig (1872-1966) was the movement’s most “outspoken” advocate in Britain (Fisher 30); Housman collaborated with Harley Granville-Barker (1877-1946) on a Pierrot play: Prunella, or Love in a Dutch Garden (1906). Baillie’s exhibition of Harlequinade pictures at his Gallery in September 1904, coupled with his decision to feature one of Bayes’s designs from this show on the Venture cover, highlights his interest in stylized artforms like the commedia. In effect, his choice of cover design made The Venture the public face of this anti-realist, intermedial movement in 1905. Unlike the ephemerality intrinsic to exhibition and performance, a print object, able to travel to readers in their own space and live with them there, has the twin powers of mobility and permanence.

Signed with the monogram “WB,” but not otherwise credited on the Table of Contents, Bayes’s dramatic composition shows the lovers Harlequin and Columbine on a sailing ship, with the annual’s title, “The Venture,” printed below the scene as if to signal the uncertain outcome of the voyage (fig. 1). Bayes was a founding member of the Camden Town Group of artists, replaced Roger Fry as art critic for the Athenaeum in 1906, and served as headmaster of the Westminster School of Art from 1918 to 1934 (“Walter Bayes,” np). In his review of the Baillie Gallery exhibition for the Art Journal, Frank Rinder commented that Bayes saw the vicissitudes of Harlequin and Columbine as symbolic of the “tragi-comedy of life…where the whole world is the stage” (299). Baillie reproduced one of the most significant works in this exhibition, a “large and ambitious pastel” entitled “Chasse Aux Amoureux” (Rinder 297), as a halftone print in The Venture. Another work, described by Rinder as a small pastel of Harlequin and Columbine on the prow of a ship (ibid.), seems to have provided the basis for Bayes’s cover design.

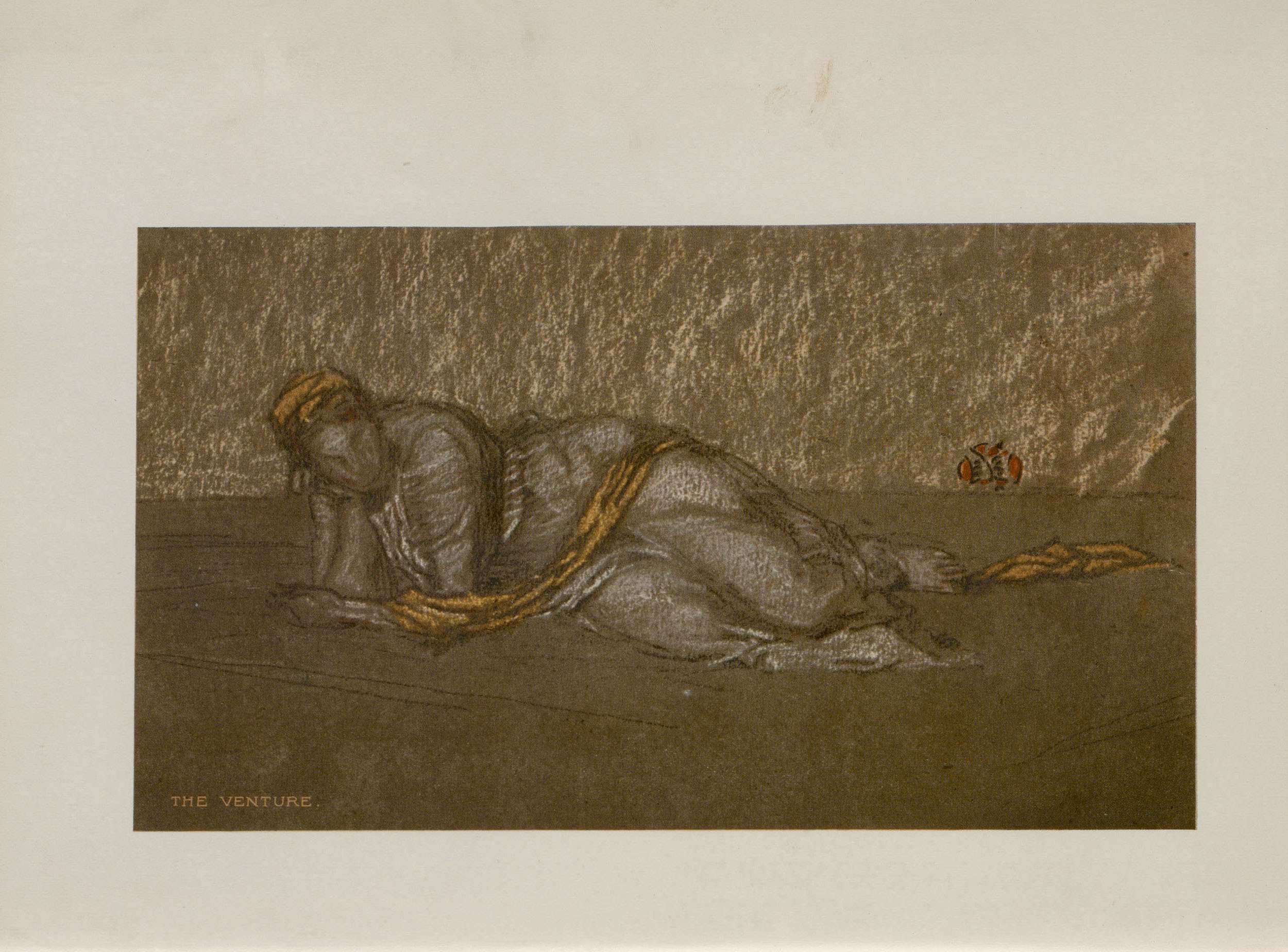

Baillie enhanced the desirability of The Venture by selecting a frontispiece by celebrity artist James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), who had died the previous year (fig. 2). Taken from the collection of Pickford Wallace (1849-1930), Whistler’s “Arrangement in Brown and Gold” appears as a “facsimile in colour” with the magazine’s title “THE VENTURE” printed in golden letters in the bottom left corner of the image. Baillie may have intended this proprietorial branding to signal the picture’s print-culture provenance, should any magazine buyer choose to remove the page for framing and display. In any case, each owner of The Venture possessed a high-quality reproduction of the original pastel on brown paper, which was soon to be on view at the Memorial Exhibition of the Works of the Late James McNeill Whistler, held between February and April 1905 in the New Gallery in Regent Street (Memorial 65). In this retrospective show of the artist’s oeuvre, the Venture frontispiece appeared under a slightly different title, “Harmony in Gold and Brown” (ibid.).

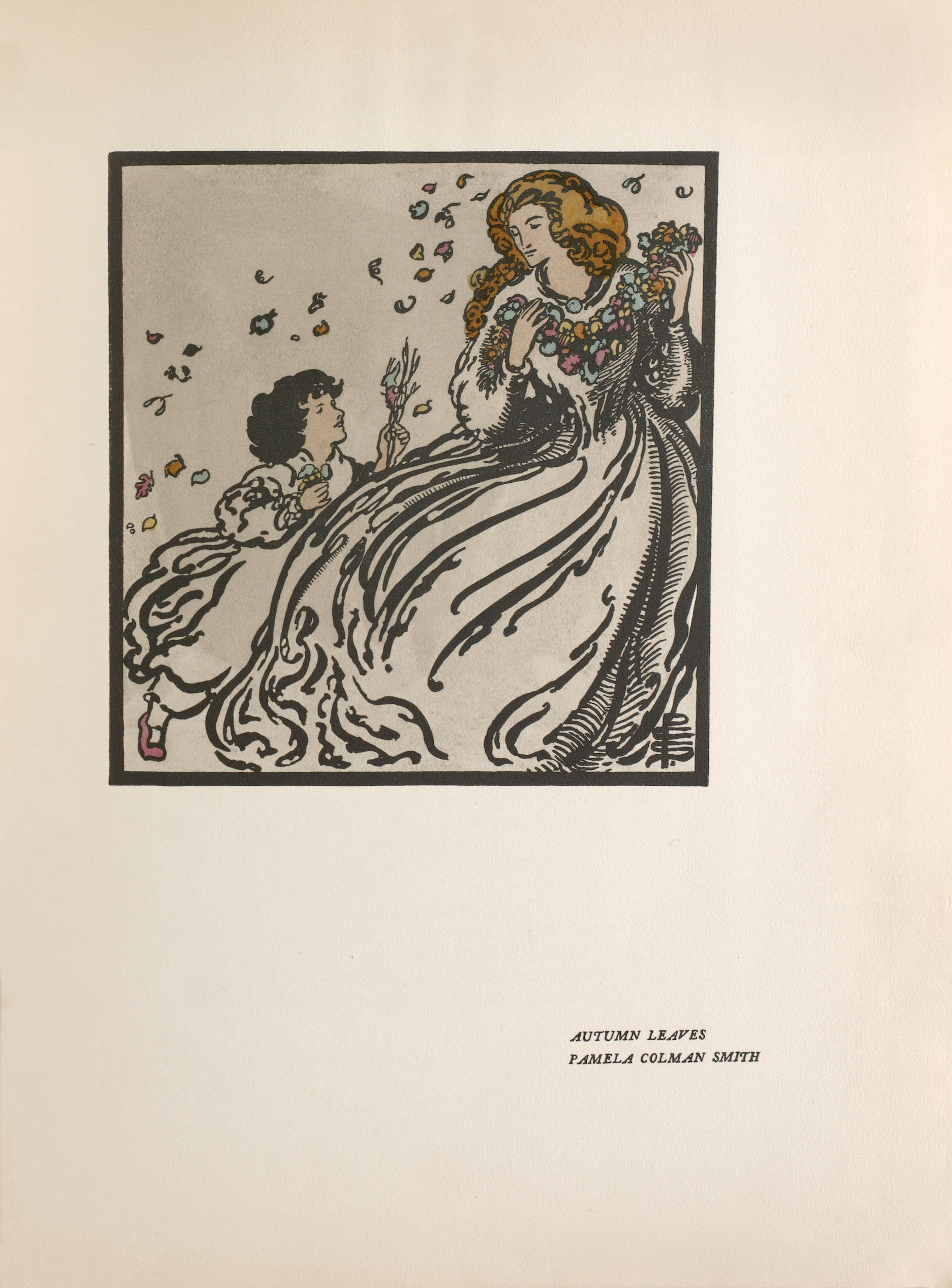

The cost and care Baillie lavished on The Venture are evident in the publisher’s willingness to enhance the magazine’s interior artworks with colour. While Whistler’s print was a colour block reproduction, the volume’s two other coloured images, “The Citadel” by Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) and “Autumn Leaves” by Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951), were produced by manual rather than photomechanical methods. Brangwyn’s “woodcut in two colours” (Table of Contents) was printed from two separate blocks in brown and black ink. Smith’s contribution, in contrast, was a hand-coloured print (fig.3). After receiving the pages from Hentschel’s line-block engraving firm, Smith painted each copy of her reproduced drawing with a water-colour wash. Smith honed this artisanal practice in her books of illustrated folklore and the little magazines she edited, The Green Sheaf (1903-4) and (with Jack Yeats) A Broad Sheet (1902) (Kooistra and Grant; Kooistra, “A Paper of her Own,” np). An artist represented by the Baillie Gallery, Smith also made use of the space for public performances of her West Indian “Annancy” tales (“Miss Colman Smith’s Story Telling”). Smith promoted Baillie’s Art Gallery, and the classes associated with it, in her magazine’s advertising pages. In turn, Baillie advertised Smith’s new venture, The Green Sheaf “shop for the sale of Hand Coloured Prints, Engravings, Drawings, Pictures & Books,” in The Venture’s back pages (Advertisement for The Green Sheaf, [v]). In some ways, “Autumn Leaves” functions as an advertisement for Smith’s shop in Knightsbridge, which housed her Green Sheaf School of Hand Colouring and its associated Green Sheaf Press (1904-6), which produced limited edition illustrated books by subscription.

Baillie’s promotion of original prints as fine art at his Gallery is also evident in the artistic contents he selected for The Venture. Whereas the first volume had printed exclusively wood engravings, the second celebrated modern printmaking more broadly by including etchings and lithographs as well. A skilful etcher as well as a wood engraver, decorative artist, and mural painter, the versatile Brangwyn—who had apprenticed with William Morris in the 1880s—contributed an etching printed in sepia tones, “An Old Farm on the Outskirts of London.” Baillie Gallery exhibitor William Monk (1863-1937), who enjoyed an international reputation for his architectural etchings (Bailey et al, np), contributed a print memorializing “Turner’s House at Chelsea.” The volume’s two lithographs were supplied by Clinton Balmer (1879-1967) and Carton Moore Park (1876-1956), both associated with Baillie’s Gallery. A Liverpool artist who trained with Augustus John (1878-1961) and was influenced by the lithographs of Charles Shannon (1863-1937), Balmer had recently illustrated The Gate of Smaragdus (1904) for Gordon Bottomley (Houfe 36). Baillie boosted the artist’s career by giving Balmer’s lithograph, “Tresses of the Surf,” pride of place as the leading image in the volume’s contents. The print is well placed to introduce the bath-themed pictures in the volume, contributed by Shannon and William Orpen (1878-1931) in different media. Park’s lithograph, “The Cockfight,” offers a stark contrast to Balmer’s romantic scene in both style and subject. Trained at the Glasgow School of Art, Park displays his decorative approach to printmaking and his strengths as a zoological illustrator (Steenson 27).

The Venture’s remaining art contents are photogravure reproductions of a variety of media. One of the most significant of these is “The Little Child Found” (fig. 4) by Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862-1927), who is hailed in an accompanying article by Cecil French (1862-1927) as the visionary “Painter of a New Day.” Referencing Robinson’s exhibition at the Baillie Gallery held earlier that autumn, French praises the artist for creating “imaginative art” to counter “the prevailing heresy of realism” (85). Imaginative art was the Gallery’s forte, as French well knew; his own work had been exhibited, along with Pamela Colman Smith’s, in Baillie’s “Dreams and Visions” show the previous year (see Introduction to The Green Sheaf, No. 7). French situates Robinson in the tradition of “spiritual art” and “romantic painting” established by William Blake (1757-1827) and the Pre-Raphaelites (86-7). Winifred Cayley Robinson (1861-1936), an illustrator who sometimes collaborated with her better-known husband, contributed “Mother and Child” to the volume. Baillie positions her tender pencil drawing immediately before French’s essay, and places her husband’s “The Little Child Found” immediately after. According to a review by C. Lewis Hind (1862-1927) in The Studio, the picture’s theme is in keeping with F.C. Robinson’s oeuvre as a whole, as his paintings always return to the same subject: “a helpless creature, found, restored” (236).

The theme of restoration is also evident in the photogravure of a cast made by John Singer Sargent (1865-1925) for The Triumph of Religion, his enormous mural cycle for the Boston Public Library (fig. 5). With an eye to editorial flow and thematic connection, Baillie places Sargent’s “The Redemption” after “Via Vita Veritas” (the Way, the Life, and the Truth), a religious poem by John Gray (1866-1934). A decadent poet whose work had appeared in a number of fin-de-siècle little magazines, including The Dial, The Pageant, and The Savoy, Gray was then serving as a Catholic priest in Edinburgh.

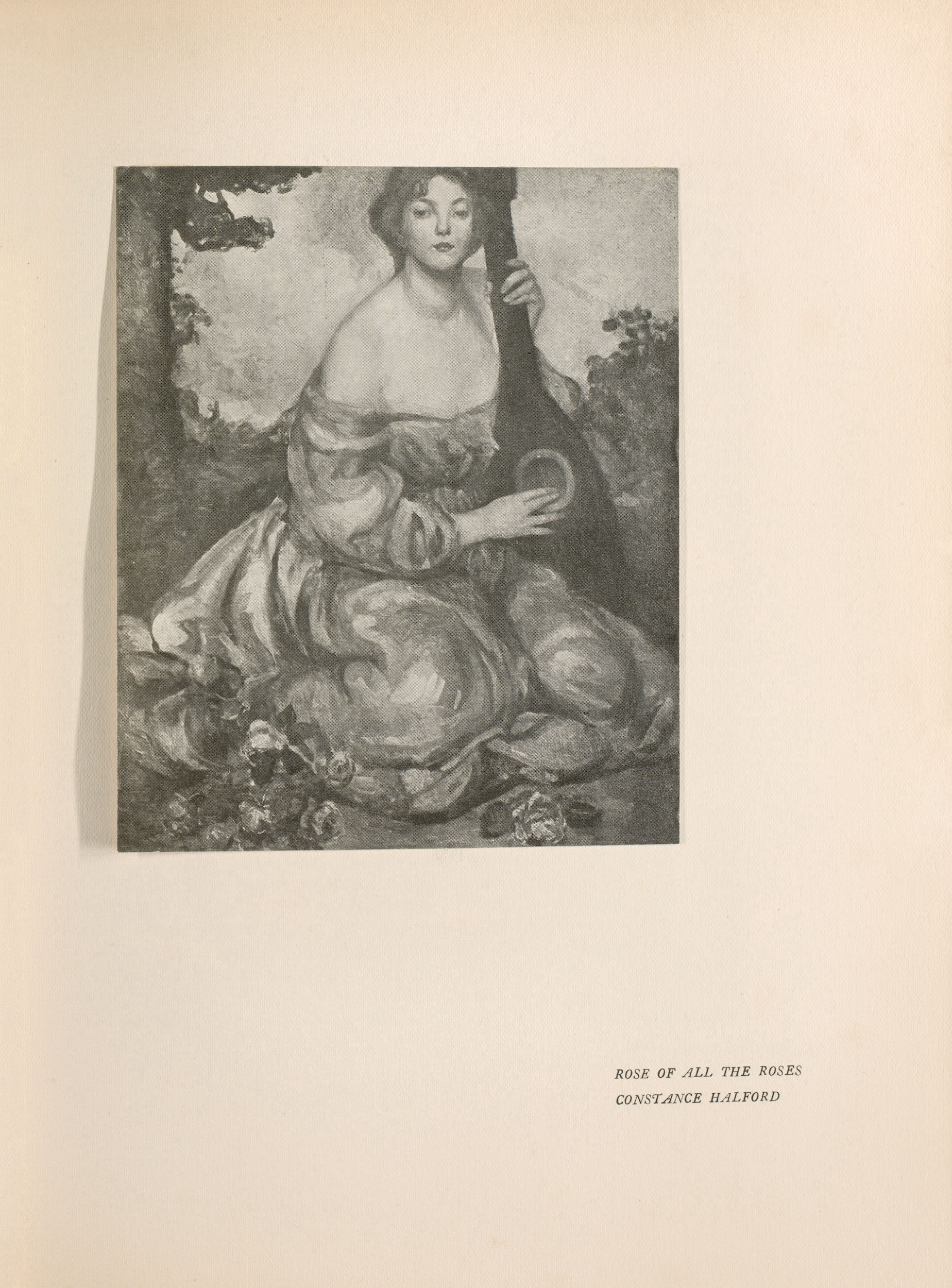

The subjects and styles of The Venture’s artworks are as varied as their mediums and technologies of reproduction. In addition to architectural drawings, religious reliefs, and portraits, the visual contents include mythical illustrations and paintings. Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), famed for his illustration of The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (1900), contributed “The Giant.” Classical subjects are represented in “The Stealing of Dionysos,” Balmer’s second contribution to the volume; “Oedipus and the Sphinx,” by Glyn W. Philpot (1884-1937); and “Centaur Idyll,” by Charles Ricketts (1866-1931). Unlike the volume’s original prints, the photogravures of tonal artwork are not always high-quality reproductions. The photogravure of Ricketts’s painting, for example, does not do justice to “Centaur Idyll,” and the same might be said of the tonal reproductions of paintings by Walter Bayes, J. Hodgson Lobley (1878-1954), and A. McC. Paterson (dates unknown). The photogravures of “The Bath of Venus” by Charles Shannon and “The Three Kimonas” by George W. Lambert (1873-1930) are more effective reproductions. Part of the Australasian colonial community Baillie cultivated in London, Lambert produced his painting on a New South Wales Travelling Art Scholarship (Lambert, np). While living in London, Lambert often visited the Halfords, an expatriate Australian family. Venture contributor and Baillie Gallery exhibitor Constance Halford and her sister Mary, both painters, sometimes acted as models for Lambert, but it is unclear whether they did so for “The Three Kimonas” (Morgan 2).

Baillie’s curation of portraits in The Venture shows his appreciation of contemporary taste and, at the same time, his commitment to cultivating interest in the work of “colonials and other outsiders” (Mackle 65), both at his Gallery and in his annual. Contemporary taste was represented in halftone prints of work by two of the foremost portrait painters of the day, Augustus John and E.J. Sullivan (1869-1933). Baillie also took care to include work by talented women artists less connected to central London’s art scene. Ann Macbeth (1875-1948), a teacher at the Glasgow School of Art and an active suffragist (Ewan et al, 258), offered “Joyce,” a decorative portrait attesting to both her Scottish art training and her feminism. Constance Halford (1865-1962?), an Australian artist represented by Baillie’s Gallery, contributed the symbolic portrait “Rose of all the Roses” (fig. 6). Baillie was ahead of his time in featuring Halford in his showroom and circulating her work in his magazine. According to Pamela Gerrish Nunn, Halford “formed a clique” with her Australian compatriot Thea Proctor (1879-1966) and British painter Isabel Gloag (1865-1917), countering the masculine cliques “that…characterized the foundation of Aestheticism.” The untold story of this trio of women painters, Nunn argues, has the power to disrupt the “established picture of British Aestheticist art” (7).

The literary contents of the volume show that Baillie was as adept at selecting and arranging verbal material in The Venture as he was at presenting its artwork, though his inexperienced copy-editing failed to reconcile a few divergences between the Table of Contents and individual items. Diverse in subject, style, and authorship, the issue’s fifteen poems, thirteen stories, three plays and three essays are united in the high quality of their writing. Notably, Baillie’s literary selections display the same preference for “imaginative art” over realism noted above in the discussion of the volume’s art contents. In addition to this tendency to the visionary and fantastic, letterpress and pictures share an interest in classical and religious subjects; represent topics of love, sex, and death; and explore the edges of subjective experience. Baillie took care to reinforce the volume’s thematic correlations in his arrangement of literary sequences and images, generating visual-verbal dialogue through adjacency and contiguity. Halford’s “Rose of all the Roses,” for instance, follows “Two Songs” by Irish poet Oliver Gogarty (1878-1957), whose speaker celebrates the beauty of his beloved, “dark as damask roses are” (138).

The Venture’s lyrics—there are no narrative poems—derive from both unknown and celebrated poets. For example, the poetic contents of the volume are notable for another set of verses by an Irishman published, like Gogarty’s, under the title “Two Songs.” This contribution is from the poet’s then unknown friend and future novelist James Joyce (1862-1941), who at the time had only published a few items in the Irish Homestead. Joyce was, however, hoping he would soon see his first book in print, a collection of poetry entitled Chamber Music. Likely because of the gallery owner’s busy schedule, Joyce had some difficulty getting Baillie to reply to his request to republish “Two Songs” when he was negotiating with Grant Richards (Joyce, Letters, 72, 76, 80). After Grant Richards declared bankruptcy in 1905, Joyce had to seek another publisher. Ultimately, when Elkin Mathews published Chamber Music in 1907, Joyce’s “Songs” from The Venture were included in the collection.

Joyce was a “young protégé” (Lhombreaud 222) of Arthur Symons (1865-1945), who also mentored two of The Venture’s women poets (Lhombreaud 221). Althea Gyles (1868-1949), an Irish artist better known as the designer of books by W. B. Yeats (1865-1939) than as a poet, contributed “Pierrot.” The poem reinforces the volume’s interest in the stock figures of the Harlequinade, first signalled in Bayes’s cover design. Indian poet Sarojini Naidu (1879-1949) contributed “Snake Charmer’s Song.” In 1896, Symons had published Naidu’s “Eastern Dancers” in The Savoy, where it appeared under her maiden name of Chattopâdhyây. 1905 saw the publication of Naidu’s first collection of poetry, The Golden Threshold, introduced by Symons and dedicated to Edmund Gosse (1849-1928), another of her supporters in London. Naidu continued her poetic output in Britain while being deeply involved in political causes in India: freedom from colonial rule; the rights of women; and Hindu-Muslim unity. Both her poetic mentors, Symons and Gosse, also contributed to The Venture. Gosse—an acknowledged arbiter of turn-of-the-century taste and a leader in the little magazine community—introduced the volume’s literary contents with “The Intellectual Ecstasy.” Other well-known poets in the issue include John Gray, T. Sturge Moore (1870-1944), Alfred Noyes (1880-1958), and Vincent O’Sullivan (1872-1940). Maurice Joy (dates unknown) and Christopher Sandeman (dates unknown) are more obscure.

Of the thirteen stories in the volume, only six might be called realist. Three of these are set in contemporary London and three have European settings. Paul Creswick (1866-1947), an insurance clerk and boys’ fiction writer who founded the short-lived little magazine The Windmill (1898), contributed “A Game of Confidences” (Oxford Companion). “Scene-Shifting,” by the unknown “E.,” a rambling anecdotal story narrated by a theatrical scene painter “while he waits for his distemper to dry and eats his sandwiches,” is addressed directly to “my dear Baillie,” so the pseudonymous author must have been part of the gallery owner’s circle, although his identity remains unknown (56). R. Ellis Roberts (1879-1933) contributed “The Ebony Box,” a story about a gas-lighting husband who torments his wife throughout their marriage with the unknown contents of what proves, on his death, to be an empty container; unable to accept this vacuity as real, the widow devotes the rest of her life to studying secret Indian societies. Arthur Ransome (1884-1967), a prolific author and friend of Venture contributors Gordon Bottomley and Pamela Colman Smith, offered “A Tuscan Melody.” The story tells how a love song written in Tuscany 700 years before spread across Italy, Europe, Scandinavia, and Britain, and was still being sung in the present. Bodley Head author Hermione Ramsden (1875-1951) translated “Two Worlds” from the Danish of J. P. Jacobsen (1847-1885), a naturalist story that shows the grim effect of local superstitions on human lives. Irish artist Nora Murray Robertson (d. 1949), who later served as secretary to George Moore (1852-1933), contributed “A Solution,” a dramatic story about a rich heiress raised with the independence of a boy, who marries a gambling Hungarian violinist; she loses all her money, but finds peace in the Alps (Fleming, np, fn 16).

The remaining stories are all fanciful; some involve horror and haunting. The latter include works by Charles Marriott (1869-1957), W. Maxwell (1866-1938), Netta Syrett, and Edward Thomas (1878-1917). Maxwell was the son of popular novelist M.E. Braddon (1835-1915), whom he served as secretary while publishing his own fiction (Oxford Companion). Maxwell’s “In the New Oriental Department” is an unsettling tale of sexual obsession, commodity culture, and orientalist fantasy. Similarly set in a contemporary London suddenly transformed into an exotic realm, Syrett’s “The Last Journey” tells of a woman who departs from Piccadilly atop an omnibus and arrives in Fairyland. In contrast, Marriott and Thomas set their stories in the countryside, connecting the natural environment to those who died there and continue to haunt the place. The stories contributed by Gordon Bottomley, Desmond F.T. Coke (1879-1931), and E.S.P. Haynes (1879-1949) imaginatively explore past and future worlds. Bottomley’s four “Old Songs” offer short retakes on well-known literary characters and authors. Haynes, a solicitor as well as a writer, offers “A Study in Bereavement: Written by Mr. Thomas Parker in 1954,” an ironic vision of a future in which death can be reversed. Coke’s “The Wayward Atom: A Tale of Evolution” ends the volume’s fiction on an unpleasant note. A misogynistic account of evolution, Coke’s tale heaps scorn on womankind, the titular atom whose refusal to help in the making of the world condemns her to being laughed at by men forever after. The story seems out of place in a volume containing so much fine work by women artists and authors, including feminists like Florence Farr, Ann Macbeth, Alice Meynell, Sarojini Naidu, and Pamela Colman Smith.

The literary contents are rounded out by three pieces of prose non-fiction and three dramatic works. In addition to Cecil French’s appreciation of the art of F. C. Robinson, the volume includes two other essays. Returning author Alice Meynell (1847-1922) and American expatriate writer Vincent O’Sullivan explore, in very different ways, modern issues of celebrity and privacy, representation and publicity. Baillie’s inclusion of three plays indicates his ongoing interest in theatre and connection to London’s performance community. Benjamin Swift (1871?-1935) and Arthur Symons each contribute a dramatic fragment based on historical events. Swift (pseud. of William Romaine Paterson) offers a fourteenth-century scene in which the titular “John de Waltham” is the absent villain, intent on marrying the unwilling Christabel, who meets with a priest and a witch in an attempt to avoid this fate. Set in antiquity, Symons’s “Otho and Poppaea” also takes up the subject of female sexuality, this time in a dramatic exploration of the complicated relationships triangulating among the beautiful Poppaea Sabina and her husbands, Nero and Otho, both Roman Emperors in the first century C.E. The most interesting play in the volume, “The Mystery of Time,” by actress, feminist, and writer Florence Farr (1860-1917), is a touchstone for the turn-of-the-century fascination with the occult. A dialogue between the symbolic characters of Past, Present, and Future, Farr’s masque urges that to live in the present, in the “NOW,” is the supreme truth (82). Produced at the Albert Hall Theatre on 17 January 1905, the play was published as an eleven-page booklet by the Theosophical Society, to which Farr belonged. Its appearance in The Venture thus offered readers a preview of the mystical vision of time later presented on stage and in the booklet.

Baillie used the back pages of The Venture to advertise his publications and his Art Gallery, as well as work by contributors. Headed “John Baillie’s Publications,” the supplement opens with an advertisement for The Dream-Garden: A Children’s Annual, edited by Netta Syrett with a cover design by her sister Nellie Syrett (Advertisement for The Dream Garden). This is followed by several pages advertising “The Venture, 1904,” edited by Laurence Housman and W. Somerset Maugham (Advertisement for The Venture, 1904). The ad promotes the sale of the previous year’s number by including its table of contents, a selection of positive press notices, and a page listing “Some Books by ‘Venture’ Contributors.” The latter is an interesting innovation on the usual publisher’s list, in that it advertises works brought out by individual authors rather than by their common publishing house. Baillie’s innovation does not stop here; his advertisement also plays fast and loose with bibliographic metadata. In an attempt to make the issue appear more current, Volume 1, time-stamped “1903” on its title page, is described in Baillie’s advertisement as “The Venture, 1904.” Baillie’s temporal adjustment was no doubt aimed at bringing the two volumes, which were brought out in November 1903 and November 1904, but dated 1903 and 1905 respectively, into a more proximate annual relationship. Baillie also prominently advertises his show room, “request[ing] Readers of the Venture to honour his Gallery by a visit,” and enticing them to do so by printing extracts of laudatory reviews (Advertisement for The Gallery). Supporting the artistic entrepreneurship of his contributors, Baillie includes an ad for Pamela Colman Smith’s Green Sheaf Shop in the new Knightsbridge Arcade and the Chelsea School of Art run by Augustus John and William Orpen at the Rossetti Studios (Advertisement for The Green Sheaf; Advertisement for the Chelsea School of Art).

Despite the critical success of his high-quality annuals and his energetic attempts to market them, John Baillie did not venture into publishing again after The Dream-Garden and The Venture of 1905. Neither title made any profit, so no contributors were paid, and it seems likely that Baillie himself did not recoup his expenses. In contrast, Baillie’s Art Gallery continued to be, according to Tony Mackle, “a financial and critical success,” thanks to his “hard work and commitment” (67). For the next ten years, Baillie continued to represent “Neglected Artists” at his Gallery, which hosted the first posthumous exhibition of gay Pre-Raphaelite painter Simeon Solomon (1840-1905) in January 1906 (Mackle 65). In 1914, Baillie closed his London Gallery and returned permanently to New Zealand (Mackle 74). As a transnational gallery owner turned publisher, John Baillie made an innovative contribution to the little magazine as a publishing genre, bringing exhibition, print, and performance cultures together in portable form. Featuring original prints and reproduced artwork by a stunning array of artists, and literature by both new and well-known authors in a variety of styles, genres, and media, The Venture is one of the last and best-produced of the late-Victorian little magazines. As the critic for The Bookman rightly concluded, “Contributors and publisher are to be warmly congratulated on the finished appearance of this generously-planned volume” (“Notes” 181).

©2023 Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, FRSC, Emerita Professor of English and Senior Research Fellow, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities

Works Cited

- Advertisement for Chelsea School of Art. Advertising Supplement, p. [v]. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2023. https://1890s.ca/vv2-advertisements/

- Advertisement for The Dream Garden. Advertising Supplement, p. [i]. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-advertisements/

- Advertisement for The Green Sheaf shop. Advertising Supplement, p. [v]. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-advertisements/

- Advertisement for John Baillie’s Art Gallery. Advertising Supplement, p. [vi]. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-advertisements/

- Advertisement for The Venture, 1904. Advertising Supplement, pp. [ii-iv]. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-advertisements/

- Bailey, Alison, Samantha Free, and Martin Pounce. “William Monk (1863-1937).” Amersham Museum. https://amershammuseum.org/history/people/20th-century/william-monk/

- Balmer, Clinton. “Tresses of the Surf.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 1. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-balmer-surf/

- —. “The Stealing of Dionysos.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 133. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-balmer-dionysos/

- Bayes, Walter. “Chasse Aux Amoureux.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 53. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-bayes-chasse/

- —. [W.B.]. Front Cover. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-front-cover/

- Bottomley, Gordon. The Gate of Smaragdus. Illustrated by Clinton Balmer. London: Elkin Mathews, 1904.

- —. “Old Songs.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 165-75. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-bottomley-songs/

- Brangwyn, Frank. “The Citadel.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 8. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-brangwyn-citadel/

- —. “An Old Farm on the Outskirts of London.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 2. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-brangwyn-farm/

- Coke, Desmond F. T. “The Wayward Atom.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 184-187. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-coke-atom/

- Colophon. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-colophon/

- Creswick, Paul. “A Game of Confidences.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 154-160. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-creswick-confidences/

- The Dream Garden: A Children’s Annual, edited by Netta Syrett. London: John Baillie, 1905.

- E. “Scene-Shifting.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 56-61. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-e-shifting/

- Ellis, Richard E. “The Ebony Box.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 65-73. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-roberts-box/

- Ewan, Elizabeth, Sue Innes, Siân Reynolds, eds. The Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women: From the Earliest Times to 2004, Edinburgh University Press, 2007.

- Farr, Florence. “The Mystery of Time.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 74-82. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-farr-time/

- —. The Mystery of Time: A Masque. Theosophical Publishing Society, 1905. Google Books.

- Fisher, James. “Harlequinade: Commedia dell’Arte on the Early Twentieth-Century British Stage.” Theatre Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 1989, pp 30-44.

- Fleming, Brendan. “A Portrait of Margaret Gough and her Memoir, ‘George Moore.’” English Literature in Transition 1880-1920, vol. 55, no. 2, 2012, np. Gale Literature Resource Centre.

- French, Cecil. “A Painter of a New Day.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 85-91. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-french-painter/

- Gogarty, Oliver. “Two Songs.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 138. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-gogarty-twosongs/

- Gosse, Edmund. “The Intellectual Ecstasy.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 1-2. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-gosse-ecstasy/

- Gray, John. “Via Vita Veritas.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 62. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-gray-veritas/

- Gyles, Althea. “Pierrot.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 8. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-gyles-pierrot/

- Halford, Constance. “Rose of all the Roses.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 104. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-halford-roses/

- “Harlequinade.” The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre (2nd ed), edited by Phyllis Harnoll and Peter Found, Oxford UP, 2003. Online version.

- Haynes, E.S.P. “A Study in Bereavement.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 131-137. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-haynes-bereavement/

- Hind, Lewis. “Ethical Art and Mr. F. Cayley Robinson.” The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art, vol. 31, 1904, pp. 235-41.

- Houfe, Simon. Fin de Siècle: The Illustrators of the Nineties. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1992.

- Housman, Laurence. The Unexpected Years. London: Jonathan Cape, 1937.

- Joyce, James. Chamber Music. London: Elkin Mathews, 1907.

- —. Letters of James Joyce, vol. 2, edited by Richard Ellmann. London: Faber & Faber, 1966.

- —. “Two Songs.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 92. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-joyce-twosongs/

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “‘A Paper of Her Own: Pamela Colman Smith’s The Green Sheaf (1903-4).” Green Sheaf Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/green-sheaf-general-introduction/

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen, and Marion Tempest Grant. “Working Against ‘that thunderous clamor of the steam press’: Pamela Colman Smith and the Art of Hand-Coloured Illustration.” Nineteenth-Century Victorian Women Illustrators and Caricaturists, edited by Joanna Devereaux, Manchester University Press, 2023, pp. 251-67.

- Lambert, George. “The Three Kimonos (1905).” New South Wales Art Gallery Item. No. 560. https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/560/

- —. “The Three Kimonas.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 16. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-lambert-kimonas/

- Lhombreaud, Roger. Arthur Symons: A Critical Biography. London: The Unicorn Press, 1963.

- Macbeth, Ann. “Joyce.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 123. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-macbeth-joyce/

- Mackle, Tony. “The enterprising John Baillie, artist, art dealer, and entrepreneur.” Tuhinga, vol. 28, 2017, pp. 62-79.

- Maxwell, W.B. “In the New Oriental Department.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 9-13. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-maxwell-oriental/

- Memorial Exhibition of the Works of the Late James McNeill Whistler. New Gallery, Regent Street, London, Twenty-Second February to the Fifteenth of April 1905. William Heinemann, 1905.

- “Miss Colman-Smith’s Story-Telling.” The Times (London), 4 February 1908. Reprinted in Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story, by Stuart R. Kaplan, with Mary K. Greer, Elizabeth Foley O’Connor, and Melina Boyd Parsons, U.S. Games, 2018, p. 284.

- Monk, William. “Turner’s House at Chelsea.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 97. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-monk-chelsea/

- Morgan, Helen. “Thea Proctor in London 1910—her early involvement with fashion.” NGV, Art Journal 36, 1996, 17pp. Department of Fine Arts, University of Melbourne. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/thea-proctor-in-london-1910-11-her-early-involvement-with-fashion/

- Naidu, Sarojini. The Golden Threshold. London: William Heinemann, 1905.

- —. “Snake-Charmer’s Song.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 188. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-naidu-snake/

- —. (Sarojini Chattopâdhyây). “Eastern Dancers. The Savoy, vol. 5, Sept. 1896, p. 84. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep, https://1890s.ca/savoyv5-chattopadhyay-eastern/

- “Notes on New Books.” The Bookman, January 1905, p. 181.

- Nunn, Pamela Gerrish. “Alienation, Adoption, or Adaptation? Aestheticist Paintings by Women.” Cahiers victorienes et édouardiens, vol. 74, Autumn 2011. Accessed 14 June 2022, http://journals.openedition.org/cve/1364

- Oxford Companion to Edwardian Fiction, edited by Sandra Kemp, Charlotte Mitchell, and David Trotter. Oxford Reference Online, 2005.

- Page, William, ed. The Victoria History of the County of Hereford, vol. 4. London: A Constable, 1914.

- Park, Carton Moore. “The Cockfight.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 115. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-park-cockfight/

- Rackham, Arthur. “The Giant.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 42. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-rackham-giant/

- Ransome, Arthur. “A Tuscan Melody.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 141-46. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-ransome-melody/

- Rev. of The Venture, vol. 2. The Athenaeum, No. 4024, Dec. 10, 1904, p. 805. British Periodicals.

- Richard, Jeffrey. The Golden Age of Pantomime: Slapstick, Spectacle and Subversion in Victorian England. I.B. Tauris & Co, Ltd, 2014, p. 47. ProQuest Ebook.

- Ricketts, Charles. “Centaur Idyll.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 105. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-ricketts-idyll/

- Rinder, Frank. “London Exhibitions.” Art Journal, September 1904, pp. 297-99. British Periodicals Online.

- Robertson, Nora Murray. “A Solution.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp.114-130. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-robertson-solution/

- Robinson, Frederick Cayley. “The Little Child Found.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 84. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-robinson-child/

- Robinson, Winifred Cayley. “Mother and Child.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 94. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-robinson-mother/

- Sargent, John Singer. “The Redemption.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 64. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-sargent-redemption/

- Shannon, Charles. “The Bath of Venus.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 15. Venture Digital Edition https://1890s.ca/vv2-shannon-venus/

- Smith, Pamela Colman. “Autumn Leaves.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, p. 28. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-smith-leaves/

- Steenson, Martin. “Carton Moore Park.” Imaginative Book Illustration Society: Studies in Illustration, No. 59, Spring 2015, pp. 26-43.

- Swift, Benjamin. “John de Waltham.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 111-113. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-swift-waltham/

- Symons., Arthur. “Otho and Poppaea.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 27-29. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-symons-poppaea/

- Syrett, Netta. “The Last Journey.” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. 40-52. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-syrett-journey/

- —. The Sheltering Tree: An Autobiography. London: Geoffrey Bles, 1939.

- Thorp, Joseph (“T” of Punch). Friends and Adventures. Cape, 1931.

- “Walter Bayes. (The Camden Town Group in Context).” The Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/walter-bayes-r1105357

- Whistler, James McNeill. “Arrangement in Brown and Gold.” Frontispiece for The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-frontispiece-whistler/

MLA citation:

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Critical Introduction to The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature Volume 2 (1905).” Venture Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2023. https://1890s.ca/VV2-introduction/