XML PDF

CRITICAL INTRODUCTION

TO VOLUME 1 OF THE SAVOY (January 1896)

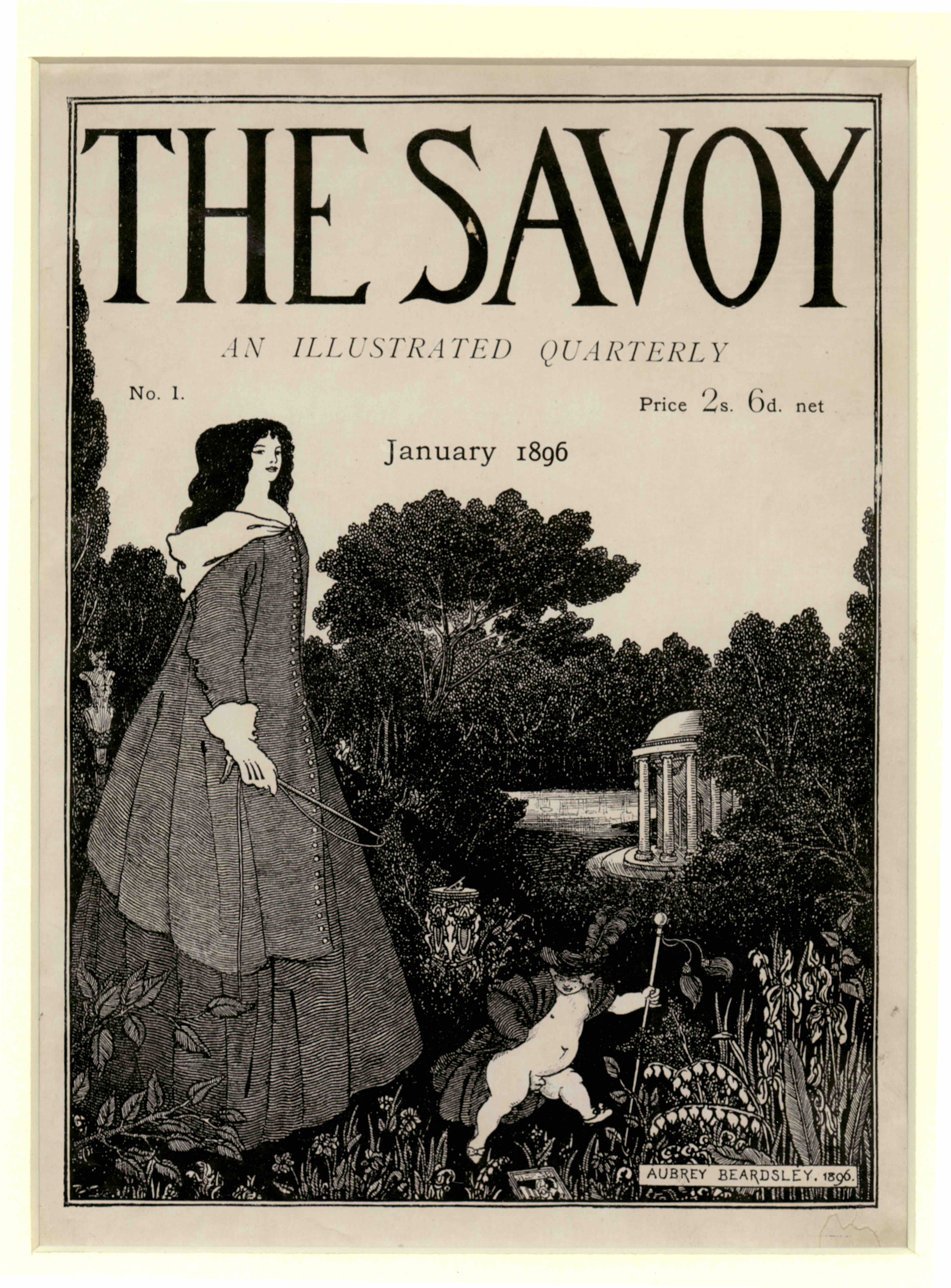

Sporting a sumptuous cover design and a list of contributors that included many of the most noteworthy writers and artists of the day, the first issue of The Savoy appeared on 4 January, 1896. It had been originally scheduled for December, in the hopes that it would benefit from appearing on the shelves during the gift-buying season. To add an additional incentive for holiday shoppers, Leonard Smithers, the magazine’s publisher, commissioned Aubrey Beardsley to produce a large Christmas card that would be included free with each copy; buyers might send the card to a friend or family member and thereby increase the public’s awareness of the magazine. Beardsley completed the card (an ornate depiction of the Madonna and child with strongly mystical rather than religious overtones), but problems with the other artwork, as described in the General Introduction, resulted in the issue not appearing until January. The cover shows a woman of almost Pre-Raphaelite demeanor pursuing a naked cherub through the gardens of a stately Georgian manor house—the mischievous creature (an alter ego for Beardsley himself) has apparently made off with the woman’s hat and she is giving chase. As originally designed, however, the cherub pauses in his dance to urinate on a copy of The Yellow Book, an implicit comment, no doubt, on how Beardsley (who had served as The Yellow Book’s art editor) felt about his former employer (fig.1). At Smithers’s insistence, Beardsley excised the image of the competitor’s cover, but the woman’s masses of flowing, dark hair, partially unbuttoned jacket, and prominent riding crop still lend the image a powerful sexual charge. If the forest into which the imp lures the woman is to be interpreted as a figure for the literary and artistic delights that await the reader, the cover design implies that these will be of a decidedly dark and sensual kind.

Another Beardsley design, of a strutting John Bull bearing an oversized pencil and quill pen, the former referring to the magazine’s art and the latter to its letterpress, accompanies the magazine’s two tables of contents (fig. 2). This image, too, had to be altered from its original design, when it first appeared as the cover to the magazine’s widely-distributed Prospectus. A group of the magazine’s more conservative contributors, headed up by George Moore, objected to what appeared to be a slight bulge in the breeches of this much-loved embodiment of the English people (Richards 19). Beardsley, at Smithers’s insistence, reluctantly removed the offending mark. Just as the altered cover design manages to retain much of its original acerbity, however, the neutered “John Bull” loses none of the swaggering braggadocio with which Beardsley imbues so many of his designs of this period.

Smithers had 3,000 copies of the first number printed by H.S. Nichols, the firm with whom he had previously worked in his publication of translations of Ancient Greek and Roman works of what the Victorian press deemed pornography (Nelson 85). But there was, in fact, little to worry the censors here. The issue opens with George Bernard Shaw’s “On Going to Church.” Following the success of Arms and the Man (1893), Shaw was one of the most notable playwrights of the fin de siècle, but he was equally well known for his contributions to the founding of the Independent Labour Party (the forerunner of the modern Labour Party), and as a theatre critic for the Saturday Review. Shaw’s contribution not only gave The Savoy a marquee name for its premiere issue, but helped underline the claim of the magazine’s editor, Arthur Symons, that the new venture would feature writers and artists from all schools, not just the decadent movement with which he and Beardsley were commonly associated (“Editorial Note”). But the essay also helps to set the tone for the magazine as a whole. It begins with a bold assertion: “As a modern man, concerned with matters of fine art and living in London by the sweat of my brain, I dwell in a world which, unable to live by bread alone, lives spiritually on alcohol and morphia” (13). Shaw’s willingness to countenance drug use, claiming that there is little to distinguish between food and stimulants, and, further, that the great advances of civilization appear to require some form of biochemical support, may seem to indulge in a notably decadent sentiment, recalling perhaps Max Beerbohm’s scandalous celebration of cosmetics from the first number of The Yellow Book. But the essay quickly tacks away from this argument to propose that the intoxication that modern men and women seek in artificial stimulants might be best achieved through a pleasure to which not even the most conservative moralist could take exception: touring the countryside to visit small parish churches.

Shaw, of course, is not urging his readers to repent their sins and seek forgiveness; quite the opposite. What delights him in church-going is not the moral instruction (he is disdainful of sermons), but the sense of spiritual ease and repose that one occasionally finds in well-designed and constructed places of worship—even in modern urban churches. In its appeal to the “master builders,” the essay is more reminiscent of William Morris or John Ruskin than Oscar Wilde: “Mirror this cathedral for me in enduring stone; make it with hands; let it direct its sure and clear appeal to my senses, so that when my spirit is vaguely groping after an elusive mood my eye shall be caught by the skyward tower, showing me where, within the cathedral, I may find my way to the cathedral within me” (17). “On Going to Church” thus sounds the keynote for the new magazine: unabashedly modern, cosmopolitan, and sophisticated, The Savoy was willing to push the boundaries of propriety in pursuit of a higher (and often secular or aesthetic) principle, but never lost sight of the need to observe middle-class proprieties.

The first number also signals Symons’s intention to use the magazine to showcase his own poetry, prose essays, and fiction. In addition to his “Editorial Note,” this issue includes Symons’s translation from the French of a poem by the controversial symboliste Paul Verlaine, a poem of his own, and an essay that draws on his experiences in Dieppe, the French coastal village where the plans for The Savoy had been drawn up the previous summer. Much as his earlier collection of poems, London Nights (1895), had demonstrated Symons’s interests in what Guy Debord would subsequently call “psychogeography,” that is to say, “the study of the specific effects of the geographical environment (whether consciously organized or not) on the emotions and behavior of individuals,” so, too, this autobiographical article captures the poet attending closely to the physical details of life in a French holiday town and their particular emotional effects: “And then the sea, at night, from the jetty; the vast space of water, fading mistily into the unseen limits of the horizon, a boat, a sail, just distinguishable in its midst, the lights along the shore, the glow of the Casino, with all its windows golden, an infinite softness in the air” (“Dieppe” 100). The article’s point of attention is not on the factual details of the town’s geography and amenities (as would be the case in a conventional travel memoir). Symons’s concern is, rather, for the shifting sense impressions that Dieppe, in its material and temporal specificity, makes on the observing eye, and how these impressions might serve as the raw material for a poetical rather than informational rendering of a time and place.

“Dieppe: 1895” is a remarkable experiment in the poetics of space, but the narrator’s gaze, taking in all it sees as a form of visual pleasure to which he feels wholly entitled, is distinctly male. The article returns repeatedly to images of women as objects of nearly fetishistic contemplation: women bathers emerging from the surf on the beach; female sex workers plying their trade in the faux glamour of the gambling rooms; a popular actress being sewn into her costume at the theatre. Laurel Brake argues that such scenes are indicative not only of Symons’s personal predilections, but of the magazine’s intended reader: “The Savoy was coded as an ‘advanced’ magazine, unsuitable for respectable women and the drawing-room, to be read by a male readership in the safety of the club and the privacy of the study” (151). Women appear in the pages of The Savoy far more often as objects of study or desire than as authors and artists in their own right.

Brake’s criticism of The Savoy’s male bias is well founded. Volume 1 includes only one contribution by a woman writer or artist, Mathilde Blind’s “Sea-Music.” Blind was a friend of Symons (who became her literary executor), and this was her last published sonnet. While many decadent writers abjured the Romantic valorization of nature in their preference for the artificial and manufactured, Blind’s late poetry often shows no such aversion. As James Diedrick writes of another sonnet from the same period, “The Evening of the Year,” “the obsessiveness, morbidity, and perversity conventionally associated with literary decadence—and the human subject—are projected onto nature itself (641). “Sea Music” is a less radical work, but the logical inversion at the heart of its central conceit is still worth noting. Nature here is no longer the origin for art, that which art, as a secondary order of creation, reproduces; it is itself a form of techné, an instrument for making strange, uncanny music; the wave-hollowed rocks act as the “fluted” chambers of a church organ, causing the “hollow mountain shell” to “reverberate” with “unearthly harmonies.” Nature becomes, in a sense, unnatural—the very figure of decadence.

If the first number provided ample scope for Symons’s writing, and that of his friends and associates such as Verlaine and Blind, it was no less a showcase for the prodigious talents of its de facto art editor. Beardsley designed not only the cover, title page, and table of contents, but also provided several further illustrations, including “The Bathers” and “Moska” for Symons’s “Dieppe 1895,” an indication that, at this early stage of the magazine’s development, the two were willing to work in tandem, a situation that would soon change. These illustrations show, too, that The Savoy was willing to present text and image on the same page, something that Beardsley resisted during his tenure at The Yellow Book (fig. 3).

The issue also features Beardsley’s first published work of prose fiction, together with three illustrations. Under the Hill is a re-working of the story of Venus and Tannhäuser. Derived from a German folktale, this legend tells of how Tannhäuser, a poet knight, discovered the grotto of Venus, how he worshipped the goddess of love in her subterranean bower, and came to regret his decision to return to the human world above. The legend has much in common with other tales of questing knights seduced and abandoned by elfin women, such as John Keats’s “La Belle Dame sans Merci” (1819), but Beardsley’s immediate inspiration was musical: a production of Richard Wagner’s three-act opera, Tannhäuser (1845) at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1895 (Sturgis 208). Beardsley had originally promised the story to Lane, who had planned to publish it as an illustrated book. Following his dismissal as art editor of The Yellow Book, however, Beardsley reworked the text so that he could publish it in another venue without Lane’s knowledge. He changed the characters’ names (Venus becomes Helen and Tannhäuser is transformed into the Abbé Fanfreluche) and expurgated many of its more explicitly sexual passages. In its new guise, he planned to feature it as a serial novel in The Savoy, another editorial practice that distinguished the magazine from its rival, The Yellow Book. The first installment opens with an elaborate dedication to a fictitious cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, followed by descriptions (and illustrations) of Franfreluche arranging his dress as her prepares to meet Helen, Helen speaking with her courtiers at her toilette, and the wildly decadent dinner party which follows. Beardsley was well-known for his willingness to set his designs at odds with the literary works he had been commissioned to illustrate. The “very oblique connection” between the text of Wilde’s Salome (1891) and some of Beardsley’s drawings, for example, led Lane to proclaim on the title page for the first English edition of the play that it had been “pictured” rather than “illustrated” by the artist (Sturgis 161). But this is not the case with the designs for his own text. They clearly reference the characters and actions of the main scenes of the first installment, and their densely embellished backgrounds, crowded pictorial space, and exuberant sense of sexual energy are stylistically in perfect harmony with the story’s ornate prose. By turns deeply sensual, grotesque, and absurd, Under the Hill was left incomplete at the time of Beardsley’s death (this was one of only two installments that appeared in The Savoy). Even so, the text and its accompanying designs remain, as Lorraine Janzen Kooistra notes, “a fantastic exploration of sexual border crossing and the freedom from proscribed social roles that such ambiguity licenses” (189).

This issue includes another example of serial fiction, the first of Frederick Wedmore’s two stories recording the correspondence between an aging painter and a young, lower-class singer and dancer. “To Nancy,” and its sequel in Volume 2, “vThe Deterioration of Nancy,” are indicative of two recurrent topics in The Savoy: the demi-monde of the theatre and music hall, and the figure of the fallen woman. In this story, the male narrator styles himself as a kind of Basil Hallward figure from Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray: the artist whose passion for youth and beauty draws him to observe the moral progress of a younger person. In this instance, however, the object of study is not a handsome young man, but an under-aged girl: Nancy is only fourteen when the two meet, and sixteen at the time of her obliquely described “fall.” The result is less an ironic play on the dangers of decadent thought (as in the case of Dorian Gray) than a patronizing “advice letter.” Clemence Ashton, the royal academician who rather unconvincingly claims to have only the young performer’s best interests at heart, is wholly oblivious to Nancy’s agency, both in her career (working hard to improve her act and gradually rising up the ladder of theatrical success) and her emotional life. As Anne Margaret Daniel writes, “‘To Nancy’ really appears to have been included to refute any contemporary suggestion that The Savoy might be read and enjoyed by New Women” (170).

Other notable works of fiction in Volume 1 include another tale of doomed romance between an older painter and an independent woman, Ernest Dowson’s “The Eyes of Pride”; a mystical tale characteristic of the Celtic Revival, William Butler Yeats’s “The Binding of the Hair”; and Max Beerbohm’s “A Good Prince,” a satiric take on the future King Edward VIII. The prose non-fiction includes, in addition to Symons’s account of the sights and sounds of Dieppe, Havelock Ellis’s trenchant defense of the novels of Emile Zola, and Joseph Pennell’s study of English book and magazine illustrations of the 1850s and 60s. “A Golden Decade in English Art” is an important example of the fin-de-siècle fascination with the history and material practices of printing; this is the period in which the book re-emerges as an object of artistic interest in its own right, and presses, such as William Morris’s Kelmscott Press, revived artisanal modes of paper making, printing, and binding. Taking particular note of the high quality of the wood-engraved illustrations produced from designs by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, and William Holman Hunt, Pennell’s article is also indicative of The Savoy’s role in bringing renewed attention to the Pre-Raphaelites. The essay is accompanied by reproductions of engravings by Frederick Sandys and James McNeill Whistler that originally appeared in the journal Once a Week.

Volume 1 also presents works of visual art that stand alone and are not supplements to the written word. This policy had been one of the innovations that Beardsley had brought to The Yellow Book, and Smithers agreed to adopt it for his new venture. As its title indicates, Charles Shannon’s “A Lithograph” is offered as a study of its technical mode of production. Just as publishers, such as Morris, were reviving medieval modes of book making, so, too, artists, such as Shannon, sought to develop techniques for the reproduction of visual art, taking up the older, French practice of drawing directly on prepared stone and taking prints from the surface. Important examples of Shannon’s technique appeared in The Dial and The Pageant in the same year. In this instance, Shannon’s use of blurred lines to indicate the two women bending in unison produces an effect akin to that of Étienne-Jules Marey’s chronophotographic studies of the body in motion from this period. Notably, and unusually, the number also includes two contemporary wood engravings, both by Paul Naumann: one after a design by Charles Conder, the other after a Beerbohm caricature of his older half-brother, the theatre manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree. Georges Lemmen’s “Head,” printed in sanguine, also stands out as distinctive for its colour, as well as for the inclusion of a Belgian artist.

As one might expect in the aftermath of the arrest of Wilde, the first number of The Savoy drew a mixed response from members of the press, many of whom were keen to remind readers of its purveyors’ scandalous reputations. The Sketch, for example, noted that the new magazine had been printed by a firm best known for its pornographic literature, and that Smithers himself was “credited with an extensive and peculiar knowledge of rare and curious books, especially facetiae” (“Small Talk” 604). Punch, the widely-read satiric magazine, lampooned the new venture’s pretenses to artistic sophistication by referring to it as “The Saveloy,” which is a type of cheap, spicy sausage. Tongue firmly in cheek, the reviewer opines, “this book should be on every school room table; every mother should present it to her daughter, for it is bound to have an ennobling and purifying influence” (“Book of the Week” 49). But such dismissals were balanced by several positive notices. The Athenaeum claimed that while the two periodicals shared many of the same contributors, The Savoy “declines to be an offshoot of the Yellow Book” and found the new title “free of some of the offences of the older periodical” (“Our Library Table” 117). The Academy also preferred the new magazine’s format to that of its rival. “As to its ‘get up’,” the reviewer writes, “it has a large page, yet is delightfully light in the hand. Very little of the writing in it has the fault of diffuseness, which belongs generally to bulk; and while some of its contents are chiefly entertaining, others are of a not less worthy gravity” (“Magazines and Reviews” 56). As Karl Beckson concludes, “On the whole, then, the appearance of The Savoy was an occasion to be celebrated” (131).

©2021 Christopher Keep, Associate Professor of English, Western University.

Works Cited

- Beardsley, Aubrey. Front Cover. The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896. The Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/savoyv1_beardsley_front_cover/

- —. Title Page. The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, p. 3. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-beardsley-title-page/

- —. Table of Contents. The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, p. 7. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-toc/

- —. “Under the Hill: A Romantic Story.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, pp. 151-70. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-beardsley-hill/

- Beckson, Karl. Arthur Symons: A Life. Clarendon Press, 1987.

- Beerbohm, Max. “A Defence of Cosmetics.” The Yellow Book, vol. 1, April 1894, pp. 65-82. Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2010-2014. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/YBV1_beerbohm_defense/

- —. “A Good Prince.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, pp. 45-47. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-beerbohm-prince/

- Blind, Mathilde. “Sea-Music.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, p. 111. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-blind-sea/

- “Book of the Week.” Punch, vol. 110, 1 Feb., 1896, p. 49. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/punchvol110a111lemouoft/

- Brake, Laurel. Subjugated Knowledges: Journalism, Gender and Literature in the Nineteenth Century. New York UP, 1994.

- Daniel, Anne Margaret. “Arthur Symons and The Savoy.” Literary Imagination: The Review of the Association of Literary Scholars and Critics, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 165-93.

- Debord, Guy. “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography.” Translated by Ken Knabb. Les Lèvres Nues, no. 6, Sept. 1955. Situationist International Online. https://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/presitu/geography.html

- Diedrick, James. “‘The Hectic Beauty of Decay’: Positivist Decadence in Mathilde Blind’s Late Poetry.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol, 34, no. 2, 2006, pp. 631-48.

- Dowson, Ernest. “The Eyes of Pride.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, pp. 51-63. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-dowson-pride/

- Ellis, Havelock. “Zola: The Man and His Work.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, pp. 67-80. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-ellis-zola/

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Sartorial Obsessions: Beardsley and Masquerade.” Haunted Texts: Studies in Pre-Raphaelitism in Honour of William E. Fredeman, edited by David Latham. University of Toronto Press, 2003, pp. 177-95.

- “Magazines and Reviews.” Review of The Savoy, vol.1, January 1896, The Academy, January 1896, p.56. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/Savoy1_Review_TheAcademy_Jan1896/

- Nelson, James G. Publisher to the Decadents: Leonard Smithers in the Careers of Beardsley, Wilde, Dowson. Pennsylvania State UP, 2000.

- “Our Library Table” Review of The Yellow Book, vol. 8, January 1896, and The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, The Athenaeum 25 January 1896, pp. 116-117. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. http://www.1890s.ca/YB8&Savoy1_review_athenaeum_jan_1896/

- Pennell, Joseph. “A Golden Decade in English Art.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, pp. 112-124. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-pennell-golden/

- Richards, Grant. Author Hunting, By an Old Literary Sports Man: Memories of Years Spent Mainly in Publishing, 1897-1925. Coward-McCann, 1925.

- Shannon, C.H. “A Lithograph.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, p. 29. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/savoyv1_shannon_lithograph/

- Shaw, George Bernard. “On Going to Church.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, pp. 13-28. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-shaw-church/

- Sturgis, Matthew. Aubrey Beardsley: A Biography. Flamingo, 1999.

- Symons, Arthur. “Editorial Note.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, p. 5. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-symons-editorial/

- —. “Dieppe: 1895.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, p. 84-102. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-symons-dieppe/

- Wedmore, Frederick. “The Deterioration of Nancy.” The Savoy, vol. 2, April 1896, pp. 99-108. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv2-wedmore-deterioration/

- —.. “To Nancy.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, pp. 31-41. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-wedmore-to-nancy/

- Yeats, W. B. “The Binding of the Hair.” The Savoy, vol. 1, January 1896, pp. 135-138. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-yeats-binding/

MLA citation:

Keep, Christopher. “Critical Introduction to Volume 1 of The Savoy (January 1896)” The Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021, https://1890s.ca/savoyv1-critical-introduction/