XML PDF

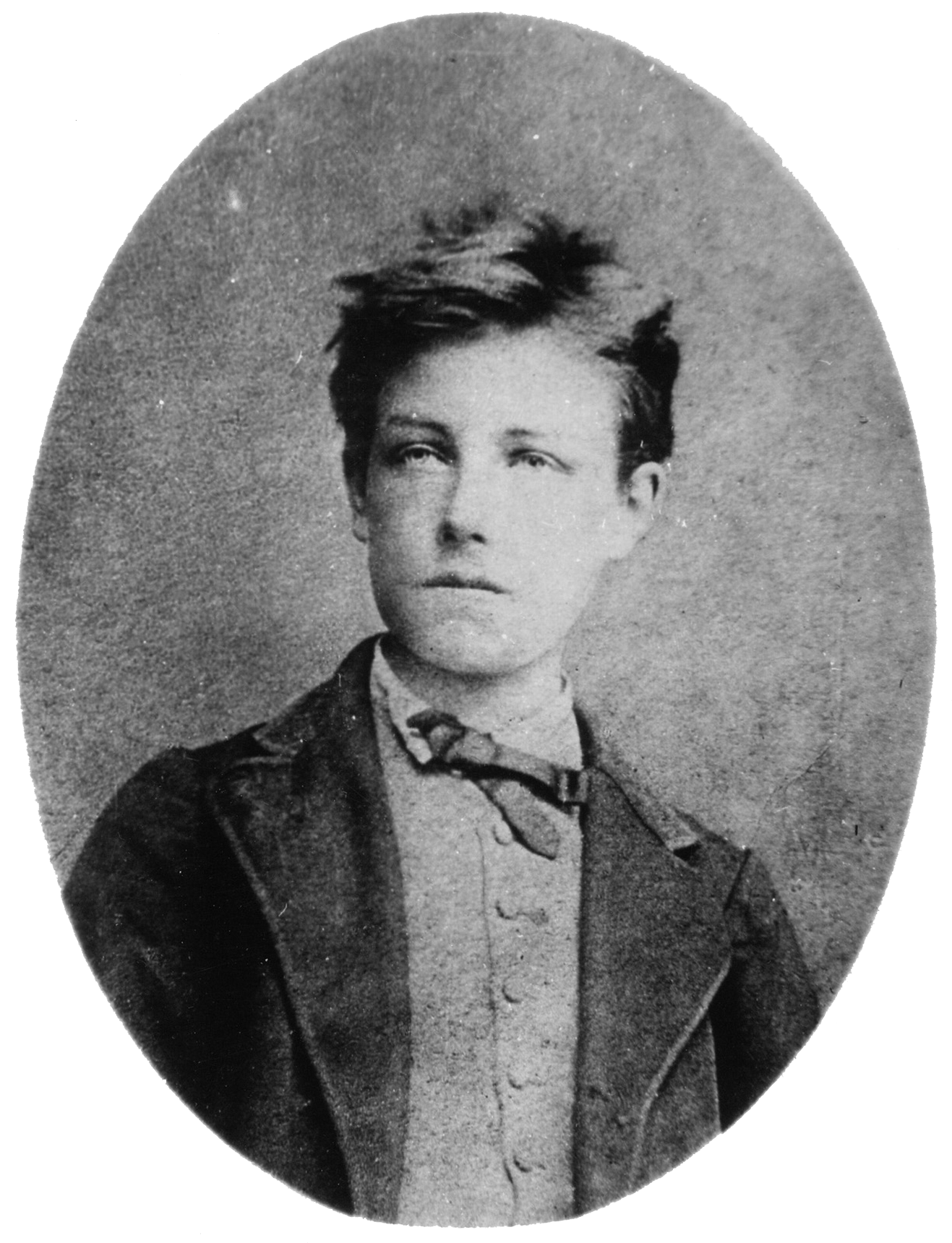

Arthur Rimbaud

(1854 – 1891)

The precocious French rebel poet associated with Decadence and Symbolism, Arthur Rimbaud was born on 20 October 1854 in the small town of Charleville in the North of France. He began writing poetry in his early teens, and rapidly came to feel that he had exhausted what his hometown had to offer. In August 1870 he made his way to Paris, only to be arrested for vagrancy, bailed out by friends and family and sent back home. Charleville couldn’t hold him though: after further rambles round the North of France, he returned to Paris in September 1871.

This was a tumultuous period: the French capital had been besieged during the final months of 1870 by invading Prussian forces. Their withdrawal was followed in April 1871 by the formation of a revolutionary government, the Paris Commune, which was then bloodily suppressed by the French authorities in May. Both Rimbaud’s writings and experiences resonated with this broader social and historical turmoil. Having begun by imitating his precursors, Rimbaud rapidly moved towards a break with literary conventions. He experimented with line lengths and rhyme combinations and played loose with the medial caesura associated with traditional French verse. Works such as “Le Bateau ivre” (“The Drunken Boat”), written in the autumn of 1871, combine daring prosody with unusual subjectivities: the poem is narrated by a boat let loose upon the waves. It was around this time that Rimbaud wrote to his friend and former school teacher, George Izambard (1848-1931) of his ambition to transform himself into a visionary poet through a “déreglement de tous les sens” (“a derangement of all the senses”).

In practice, Rimbaud’s assault on the senses involved a disordered round of drinking in various bohemian dives in Paris with his new friend, the poet Paul Verlaine (1844-1896). Having been drawn together by mutual literary admiration, the two men began a sexual relationship, prompting the breakdown of Verlaine’s marriage. They joined an unconventional group of artists and writers known as “Les Zutistes” who specialised in controversial and obscene verse. Rimbaud’s contribution included a sonnet to the anus, composed with Verlaine.

His abrupt and rude manners led to the ostracization of Rimbaud by the literary elite in Paris, who also found his relationship with Verlaine difficult to accept. The two men roamed further afield, travelling around Belgium and Northern France and spending periods of time in London, working as journalists and language teachers. Their turbulent relationship broke off when Verlaine shot Rimbaud in the wrist during a drunken altercation in Brussels on 10 July 1873. Fearful for his life, Rimbaud called the police, who arrested Verlaine. During the trial that followed, intimate details of their lives together were held up to the scrutiny of the court. Verlaine was imprisoned and Rimbaud left town, heading first to his family home in France. Soon afterwards he travelled back to England with a new friend, the poet Germaine Nouveau (1851-1920) who, briefly, became a literary disciple of sorts (it is not clear whether they were also lovers).

In terms of his poetic output, during the brief and chaotic period of his relationship with Verlaine, Rimbaud had begun to experiment with the prose poem as a literary form, finding it congenial to creative and fantastic modes of autobiography. In 1873 whilst in Brussels he arranged for the publication of a short collection of these, entitled Une Saison en enfer. But Rimbaud took away only ten copies and didn’t pay the printer, so the remainder of the initial print run of 500 copies languished in obscurity until a chance discovery in 1901. Not long after the break-up with Verlaine, Rimbaud abandoned his literary career altogether.

This laissez-faire attitude towards his work and his decision to abandon writing left Rimbaud’s literary reputation largely in the hands of others. During a last meeting with Verlaine in Stuttgart during 1875 (after his release from prison) Rimbaud handed over another cache of prose poems, asking him to pass them on to Nouveau in London. But Verlaine kept the poems, publishing them as Illuminations in the journal La Vogue during 1886. Edited by another poet, Gustave Kahn (1859-1936), this publication was closely associated with the Symboliste movement. As such, it was one of a number of little magazines that served as vehicles for avant-garde contemporary artistic and literary movements in France. This publication helped introduce Rimbaud to a younger generation of writers who were more receptive to his literary experiments than the older generation he had upset in Paris during the 1870s.

Verlaine also wrote about Rimbaud in Poètes maudits (1888), a collection of critical profiles of writers including Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-1898) and Villiers de l’Isle Adam (1838-1889), which construed them as “cursed poets,” fostering their association with decadence and transgression. Focussing on the poet’s youth and precocity, Verlaine’s entry on Rimbaud (first published in the magazine La Lutece in October 1883) incorporated full quotations of several poems, including “Les Effarés” (The Aghast), “Voyelles” (Vowels) and “Les Chercheuses de Poux” (The Lice Seekers), as well as partial quotations from other works such as “Le Bateau ivre.” It served in this way as a mini-anthology, helping to disseminate Rimbaud’s work. His synaesthetic mapping of colours and sensations onto vowel sounds in the sonnet “Voyelles” caught particular attention amongst the Symbolistes.

Abandoning literary life in France, Rimbaud travelled through Italy and beyond, first to Greece and Cyprus, then to Aden and Somalia, before settling in Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia) where he worked at a trading outpost. This period of Rimbaud’s life is poorly documented and became the object of mystery and gossip (Verlaine’s account of his disappearance in Poètes maudits contributed to the myths accumulating around Rimbaud). He was said to be running guns and British intelligence reports on his movements later prompted Enid Starkie to suggest that he was involved in the slave trade (Robb 390-91). Rumours even circulated about his death. When he did die (from cancer) in November 1891, much of his literary inheritance was controlled by his sister, Isabelle (1860-1917), who wrote memoirs of her brother that sought to downplay his transgressive actions and construe him as a pious Catholic. Writing under the pseudonym “Paterne Berrichone,” Isabelle’s husband Pierre-Eugène Dufour (1855-1922) also took control, editing the poet’s works and correspondence with as much concern for his own literary ambitions as those of Rimbaud.

Graham Robb observes that Rimbaud was “unknown beyond the avant-garde at the time of his death” (Robb, xiii) and nor was he well-known across the channel. Rimbaud was fascinated by the English language, incorporating cross-linguistic play into his work and, curiously, one of his earliest published poems, a version of “Les Effarés” entitled “Petits pauvres” (“The Little Poor”) appeared in The Gentleman’s Magazine during 1878, but no record of how Rimbaud’s work came to appear in this middle-brow publication survives. (It is likely that he had submitted it five years earlier during one of his visits to London.)

The Irish novelist and critic George Moore (1852-1933) claimed to be the first writer to introduce Rimbaud to an English-speaking public in his article, “Notes and Sensations,” published within The Hawk in 1890. This drew attention to previous discussion of Rimbaud’s work in Moore’s autobiographical novel, Confessions of a Young Man (1887). Moore’s article discusses Rimbaud alongside Jules Laforgue and includes a quotation from the poem “Ma Bohème” (“My Bohemia”). Not long afterwards, T. Sturge Moore published a translation of “Les Chercheuses de Poux” in the second volume of The Dial in 1892, where it was accompanied by his tribute, “To the Memory of Arthur Rimbaud” (10). Sturge Moore also contributed two poems under the collective heading, “Suggested by the Prose of Arthur Rimbaud: ‘Enfance’ and ‘Through a Child’s Eyes’” (19) to the third volume of The Dial the next year.

Around the same time, John Gray included translations of “Sensation” and “A la musique” (as “Charleville: Imitated from the French of Arthur Rimbaud”) in his collection, Silverpoints (1893). Three works by Rimbaud (including “Voyelles”) were also amongst the poems anthologised in translation by William Robertson in A Century of French Verse (1895). Sturge Moore would subsequently incorporate translations of “Sensation” and “Les Chercheuses de poux” (as “The Lice Pickers”) into his collection The Vinedresser (1898).

This suggests a brief vogue for Rimbaud’s work in Britain during the 1890s as part of “The Decadent Movement in Literature” identified by Arthur Symons in his famous essay for Harper’s New Monthly in 1893. Amongst these responses, Sturge Moore’s engagement with Rimbaud is the most notable. His versions of Rimbaud appear in The Dial alongside Gray’s version of Verlaine’s “Parsifal,” reflecting the particular influence of avant-garde and Symboliste French literature upon that magazine (Claes 70-71). These scattered translations, however, are not very substantial. They suggest how Rimbaud’s status derived as much from the myth-making that grew up around his unconventional behaviour as from a sustained engagement with his poetic innovations. Sturge Moore’s responses confirm this by adopting allusive verse forms derived from the autobiographical mythologising in the prose poetry of Une Saison en enfer. His efforts begin to forge new myths of the boy poet for English readers.

The mystery surrounding Rimbaud and a lack of concrete particulars regarding his work is also reflected in critical responses from the late nineteenth century. Symons, for example, omitted Rimbaud from his essay on the Decadent Movement. Instead, he added a chapter on him to The Symbolist Movement in Literature (1899). This decision was based on article he had published in the Saturday Review the previous year, drawing largely on the biographical and textual ministrations of “Paterne Berrichon.” Scattered references and passing mentions of Rimbaud can be found in various avant-garde periodicals at this time too: William Sharp’s piece “Oread” for the Pagan Review (writing as Charles Verlayne) refers briefly to Rimbaud in an opening footnote and Osman Edwards’ essay on “Emile Verhaeren” for the seventh volume of The Savoy alludes to him amongst recent Symbolist writers. However, sustained engagement, such as Charles Whibley’s appreciation of Rimbaud as “A Vagabond Poet” for Blackwood’s Magazine in 1899, is rare.

Even if little was known about him or his work, Rimbaud’s name was often conjured in the 1890s literary criticism: in 1892, for example, an anonymous reviewer for the National Observer could refer to him in passing as “Rimbaud (of the Vowels)” in a longer piece about recent French Bohemian literature. At times, the reach of his work may be surprising. In the autumn of 1898, for example, several regional newspapers, including the Bicester Herald and the Faverhsam News reprinted two short paragraphs on synaesthesia and symbolism under the generic heading of “Science Notes” that made passing reference to “Voyelles.” The source for this material seems to have been an issue of the London-based publication the Globe, but this scissors-and-paste journalism testifies to the circulation of the poet’s name beyond the metropolis, albeit in limited form.

As Jennifer Higgins records, Rimbaud started to acquire a broader influence on English readers during the 1920s and 1930s, when his work became popular amongst Modernist writers and the Surrealists, who were particularly fascinated by the experiments with verse form and altered states of being. At this time, Ezra Pound (1885-1972) projected a collection of translations from Rimbaud (not published until the 1950s) and translations of his prose poems were published by Helen Rootham in Wheels (under the aegis of Edith Sitwell) and George Frederic Lees. Norman Cameron translated “Le Bateau ivre” (“The Drunken Boat”) in New Verse in 1936 and around the same time Samuel Beckett began work on his own version of the same poem (although this was not published until much later). Shortly afterwards, Enid Starkie produced one of the first English-language biographies of Rimbaud, beginning a tentative process of unpicking the mysteries around his life and writings.

Still strongly associated with avant-garde literary circles, Rimbaud and his work didn’t acquire wider popularity until later. In the 1960s, he was adopted as the poster child for literary rebels throughout the world: his image was stencilled on the walls of the Sorbonne during the student demonstrations of May 1968 in Paris; his writings influenced Allen Ginsberg and Jim Morrison; and Patti Smith described him as “the first punk poet” (Robb xv). His slender output has come in this way to be a significant literary influence, central in recent years to decadence studies and queer studies as well as within French literature more generally.

©2022, Matthew Creasy, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, School of Critical Studies, University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK.

Major Works by Rimbaud

- “Les Étrennes des orphelins.” La revue pour tous, January 1870, pp. 489-91.

- “Trois baisers.” La Charge. 13 August 1870.

- “Les Corbeaux.” La renaissance littéraire et artistique, 14 September 1872.

- “Petits pauvres.” The Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. 245, January 1878, p. 94.

- Une Saison en enfer. Brussels: M.J. Poot & Co., 1873.

- Les Illuminations, edited by Paul Verlaine. Paris: Publications de la Vogue, 1886.

- Reliquaire – poésies, intr. Rodolphe Darzens. Paris: L. Genonceaux, 1891.

- Poésies completes, edited by Paul Verlaine. Paris: Vanier, 1895.

Selected Publications by Rimbaud in Anglophone Publications

- Beckett, Samuel. Drunken Boat, intr. James Knowlson. Reading: Whiteknights, 1976.

- Cameron, Norman. “The Drunken Boat.” New Verse, June-July 1936, pp. 9-12.

- Gray, John. Silverpoints. London: Bodley Head, 1893.

- Lees, George Frederic. A Season in Hell. London: Fortune, 1932.

- Moore, T. Sturge. “To the Memory of Arthur Rimbaud,” The Dial, vol. 2, 1892, p. 10. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019.

- —. “Les Chercheuse de Poux: After Arthur Rimbaud,” The Dial, vol. 2, 1892, p. 17. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/dialv2-moore-poux/.

- —. “Suggested by the Prose of Arthur Rimbaud: ‘Enfance’ and ‘Through A Child’s Eyes.’” The Dial, vol. 3, 1893, p. 19. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://1890s.ca/dialv3-moore-suggested/.

- —. The Vinedresser and Other Poems. London: At the Sign of the Unicorn, 1898.

- Pound, Ezra. The Translations of Ezra Pound. London: Faber, 1953.

- Rootham, Helen. “Three Prose Poems from the French of Jean Arthur Rimbaud.” Wheels. 1916, pp. 83-88.

- —. Prose Poems from Les Illuminations of Arthur Rimbaud, intr. Edith Sitwell. London: Faber & Faber, 1932.

- —. “Selection from Illuminations.” Échanges, vol. 4, 1931, pp. 80-89.

- —. “Selection from Illuminations.” Échanges, vol. 5, 1931, pp. 119-35.

Works Cited and Selected Publications about Rimbaud

- Anon. “A Dispassionate Pilgrim.” National Observer, 14 August 1892, pp. 330-31.

- Anon. “Echoes of Science.” Globe, 28 October 1898, p. 8.

- Anon. “Science Notes.” Hants and Sussex News, 16 November 1898, p. 3.

- Anon. “Science Notes.” Radnorshire Standard, 16 November 1898, p. 3.

- Anon. “Science Notes.” Bicester Herald, 18 November 1898, p. 3.

- Anon. “Science Notes.” East and South Devon Advertiser, 19 November 1898, p. 7.

- Anon. “Science Notes.” Faversham News, 19 November 1898, p. 6.

- Anon. “Reviews.” Harrow Observer, 2 December 1898, p. 7.

- Berrichon, Paterne [Pierre-Eugène Dufour]. La vie de Jean-Arthur Rimbaud. Paris: Société du Mercure de France, 1897.

- —. Jean-Arthur Rimbaud: Le Poète – Poèmes, lettres et documents inédits. Paris: Société du Mercure de France, 1912.

- Higgins, Jennifer. English Responses to French Poetry 1880-1940: Translation and Mediation. London: Legenda, 2011.

- Moore, George. “Notes and Sensations.” The Hawk, 23 September 1890, pp. 353-55.

- Rimbaud, Isabelle. Reliques: Rimbaud mourant, Mon frère Arthur, Le Dernier voyage de Rimbaud, Rimbaud catholique. Paris: Mercure de France, 1921.

- Robb, Graham, Rimbaud. London: Picador, 2000.

- Roy, G. Ross. “A Bibliography of French Symbolism in English-language publications to 1910.” Revue de literature comparée, vol. 34, 1960, pp. 645-59.

- Starkie, Enid. Arthur Rimbaud. London: Faber, 1938.

- —. From Gautier to Eliot: The Influence of France on English Literature 1851-1939. London: Hutchinson, 1960.

- Tilby, Michael. “Arthur Rimbaud.” Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English, edited by Olive Classe, London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2000, pp. 1167-73.

- Symons, Arthur. “The Decadent Movement in Literature.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, vol. 87, November 1893, pp. 858-67.

- —. “Arthur Rimbaud.” Saturday Review, 28 May 1898, pp. 706-7.

- —. The Symbolist Movement in Literature, London: William Heinemann, 1899.

- Verlaine, Paul. “Arthur Rimbaud.” The Senate, vol. 2, October 1895, pp. 373-76.

- —. Les poètes maudits. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1888.

- White, Edmund, Rimbaud: The Double Life of a Rebel, London: Atlantic Books, 2008.

- Whibley, Charles. “A Vagabond Poet.” Blackwood’s Magazine. February 1899, pp. 402-12.

- Whidden, Seth, Arthur Rimbaud. London: Reaktion, 2018.

MLA citation:

Creasy, Matthew. “Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/rimbaud_bio/