The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume II July 1894

Contents

Literature

I. The Gospel of Content . By Frederick Greenwood Page 11

II. Poor Cousin

Louis . . Ella D’Arcy . . . 34

III. The Composer of “Carmen” Charles Willeby . . 63

IV.

Thirty Bob a Week . John

Davidson . . 99

V. A Responsibility . .

Henry Harland . . 103

VI. A

Song . . . . Dollie Radford . . 116

VII. Passed . . . . Charlotte M. Mew

. 121

VIII. Sat est Scripsisse . . Austin Dobson . . 142

IX. Three

Stories . . . V., O., C.S. . . . 144

X. In a

Gallery . . . Katharine de Mattos . 177

XI.

The Yellow Book, Philip Gilbert Hamerton

criticised LL.D. . . .

179

XII. Dreams . . . . Ronald

Campbell Macfie 195

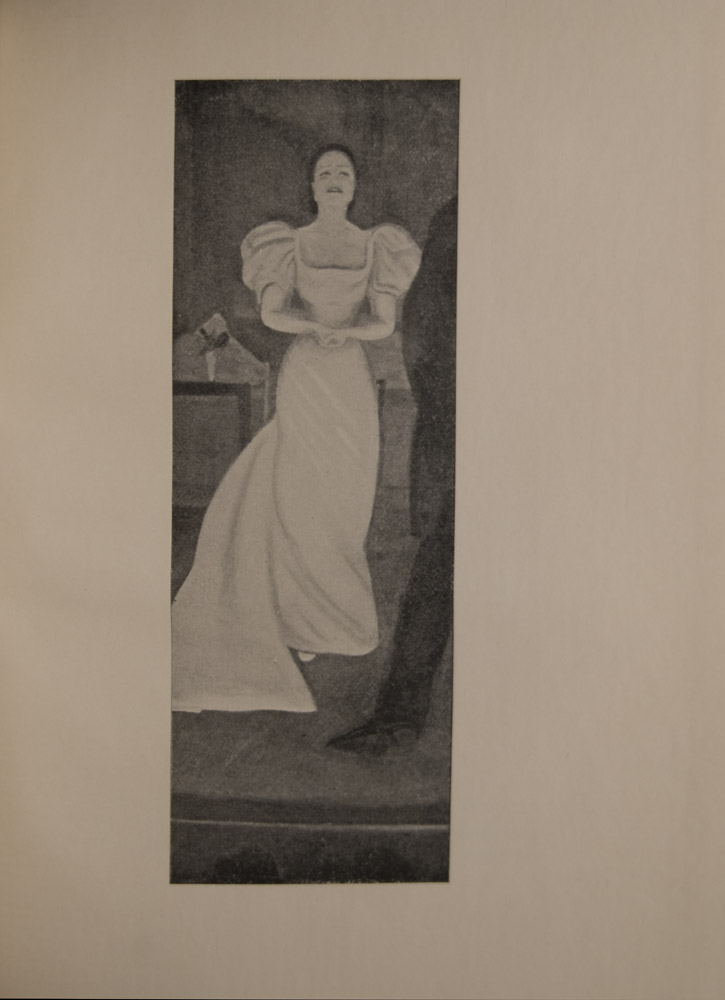

XIII. Madame Réjane

. . Dauphin Meunier . . 197

XIV. The Roman Road . . Kenneth

Grahame . . 211

XV. Betrothed . . . Norman Gale . . 227

XVI. Thy

Heart’s Desire . . Netta Syrett . . . 228

XVII. Reticence in Literature . Hubert Crackanthorpe . 259

XVIII. My

Study . . . Alfred Hayes . . . 275

XIX. A Letter to the Editor . Max

Beerbohm . . 281

XX. Epigram . . . William Watson . . 289

XXI. The

Coxon Fund . . Henry James . . . 290

Art

The Yellow Book—Vol. II—July, 1894

Art

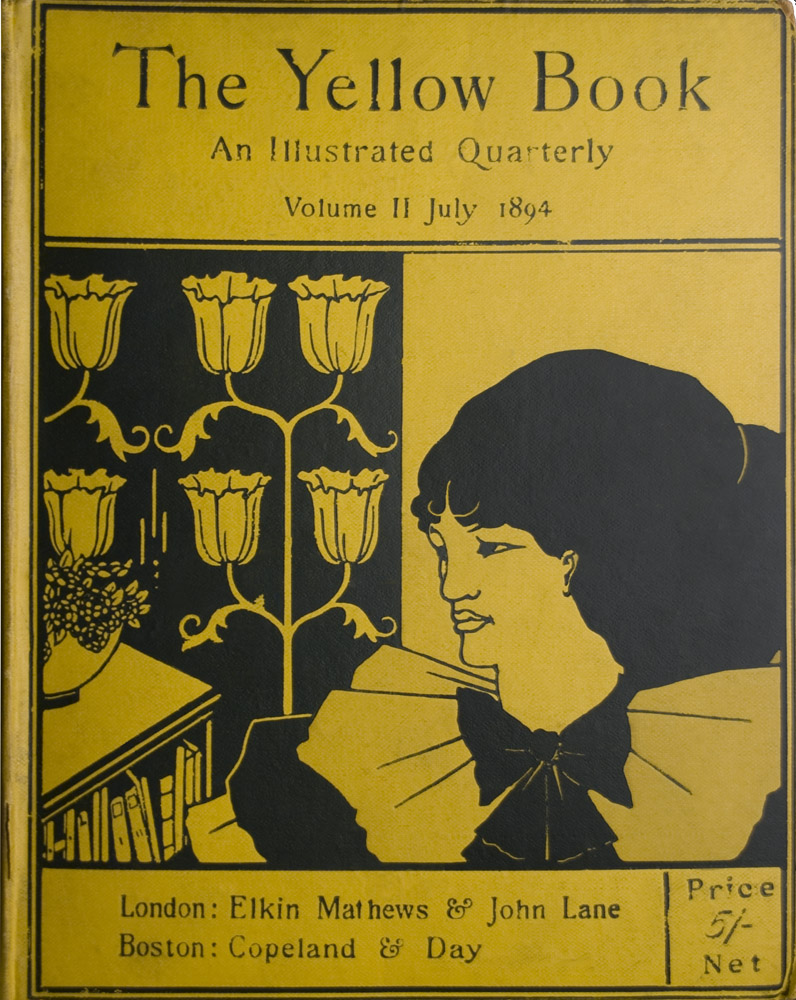

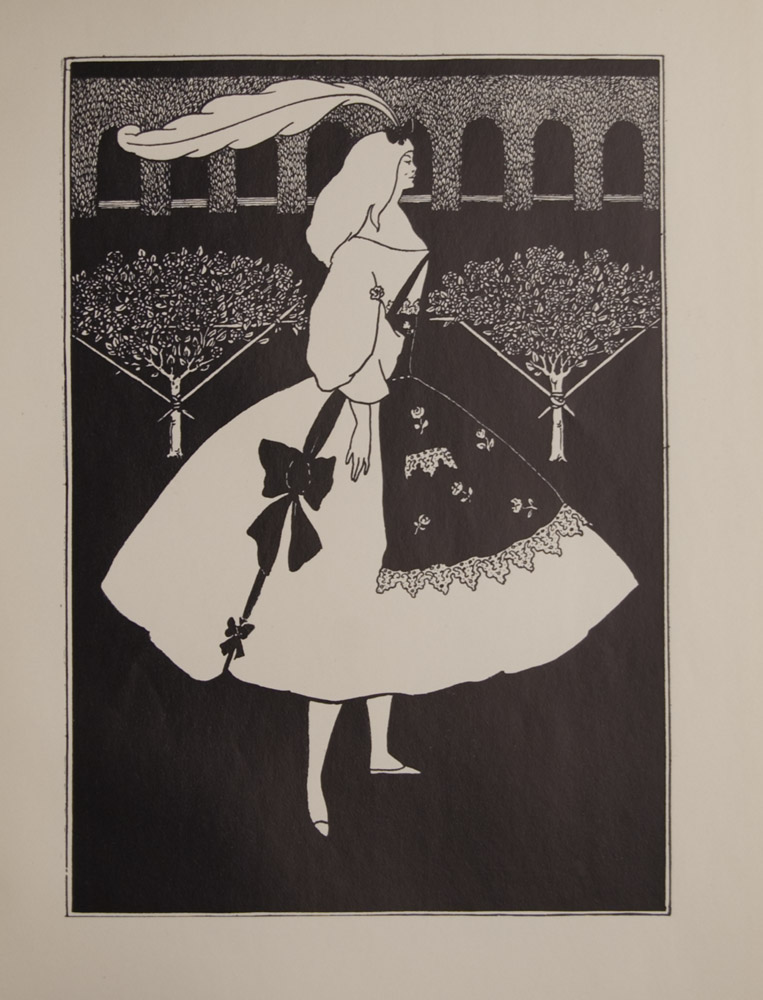

Front Cover, by Aubrey Beardsley

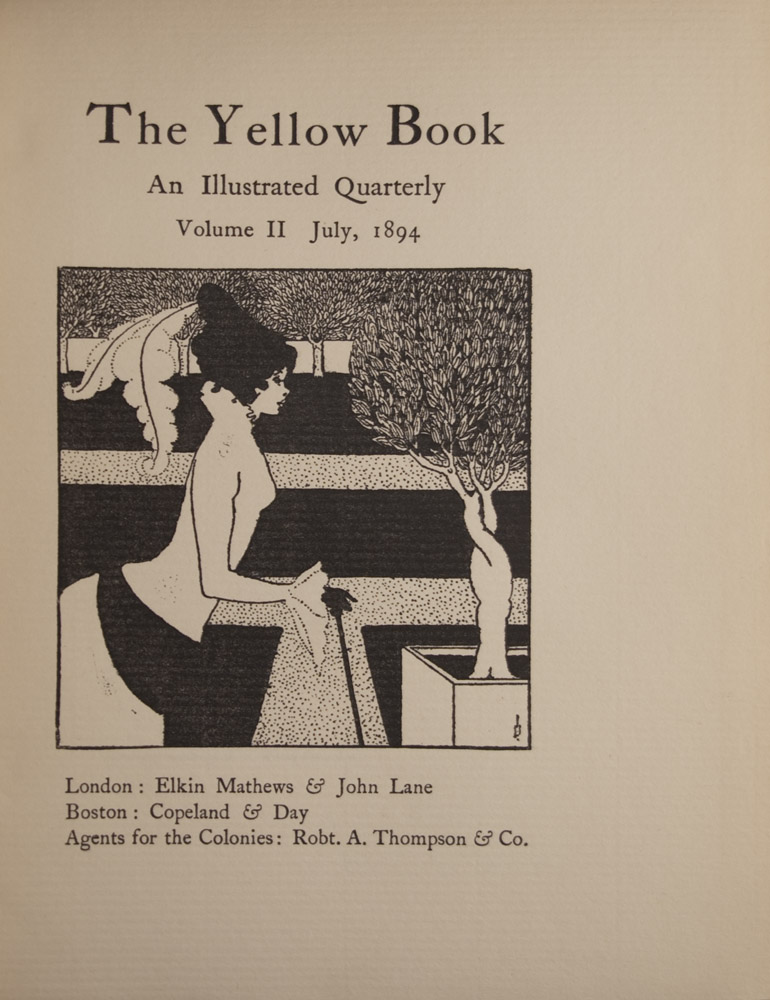

Title Page, by Aubrey Beardsley

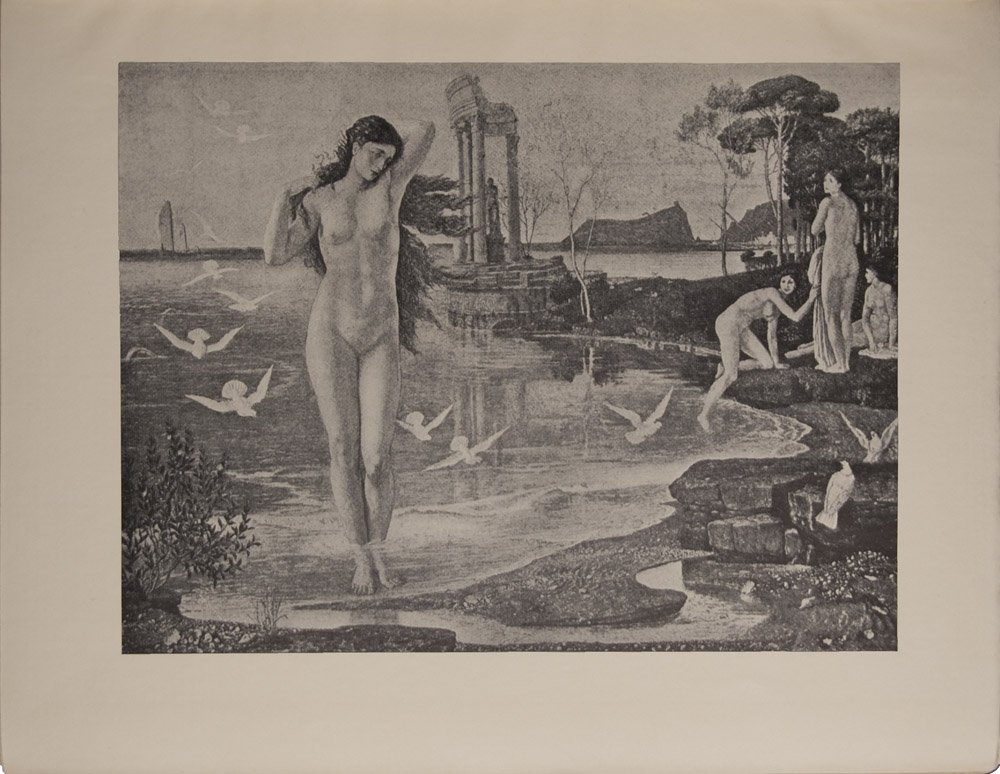

I. The Renaissance of Venus by Walter Crane . . Page 7

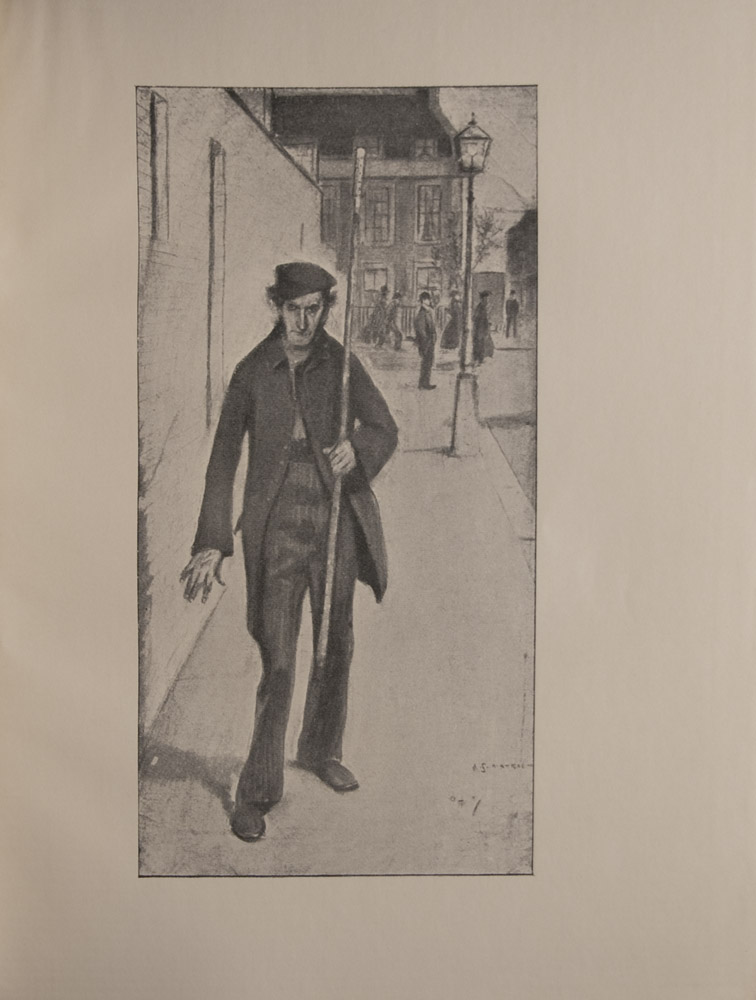

II. The Lamplighter . . A.S.

Hartrick . . 60

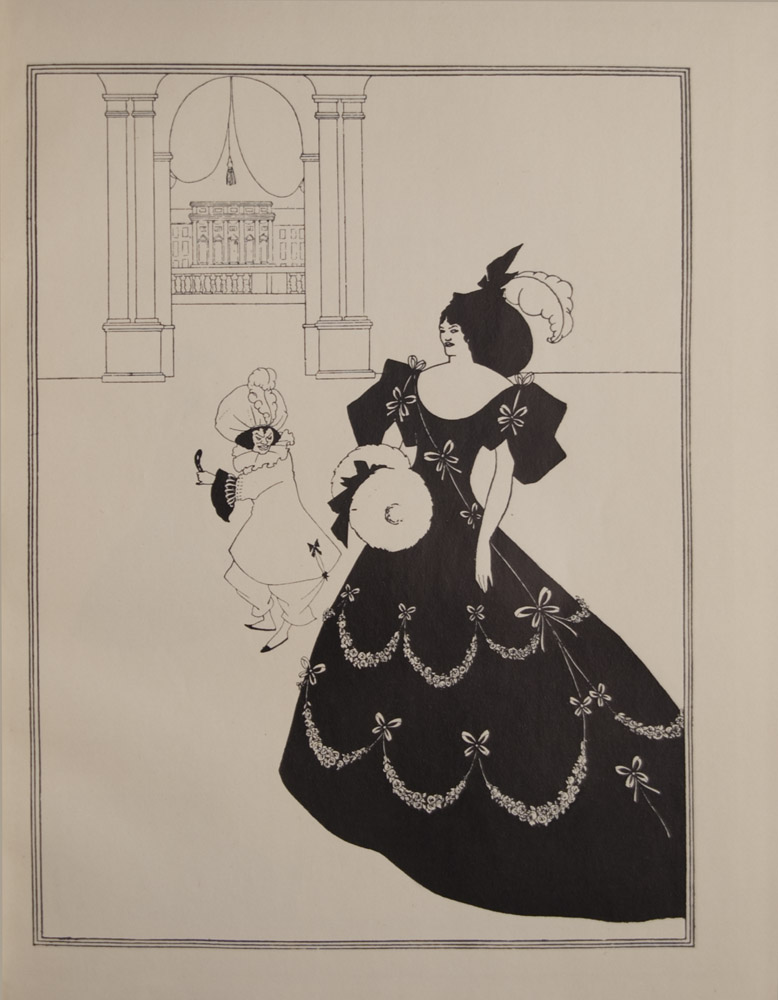

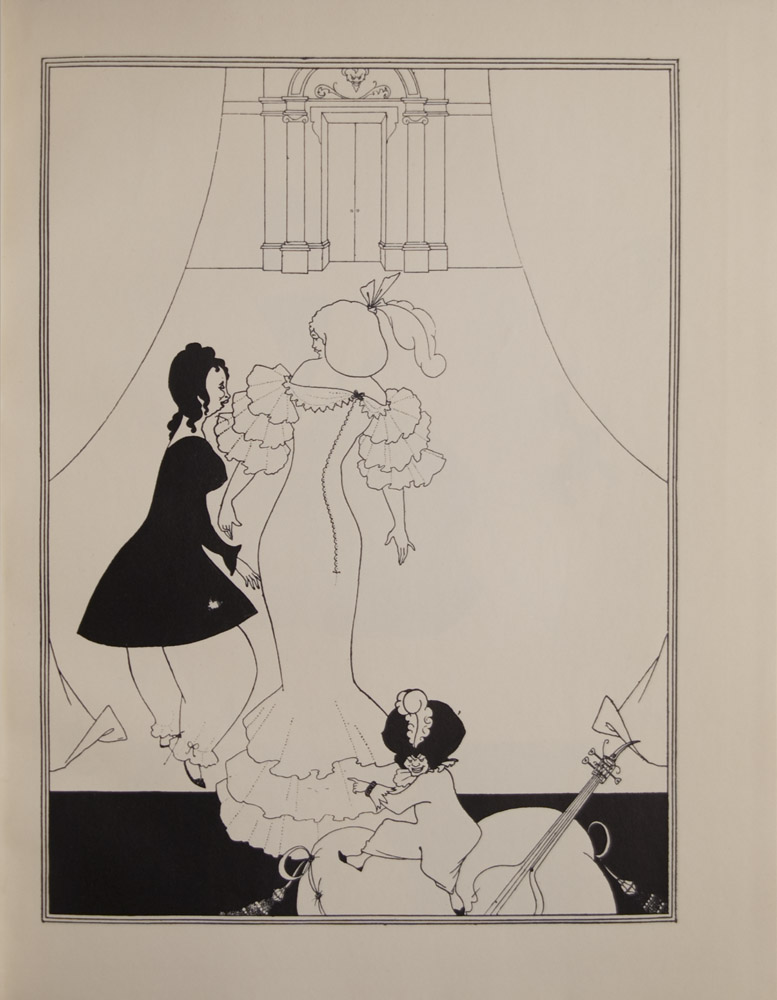

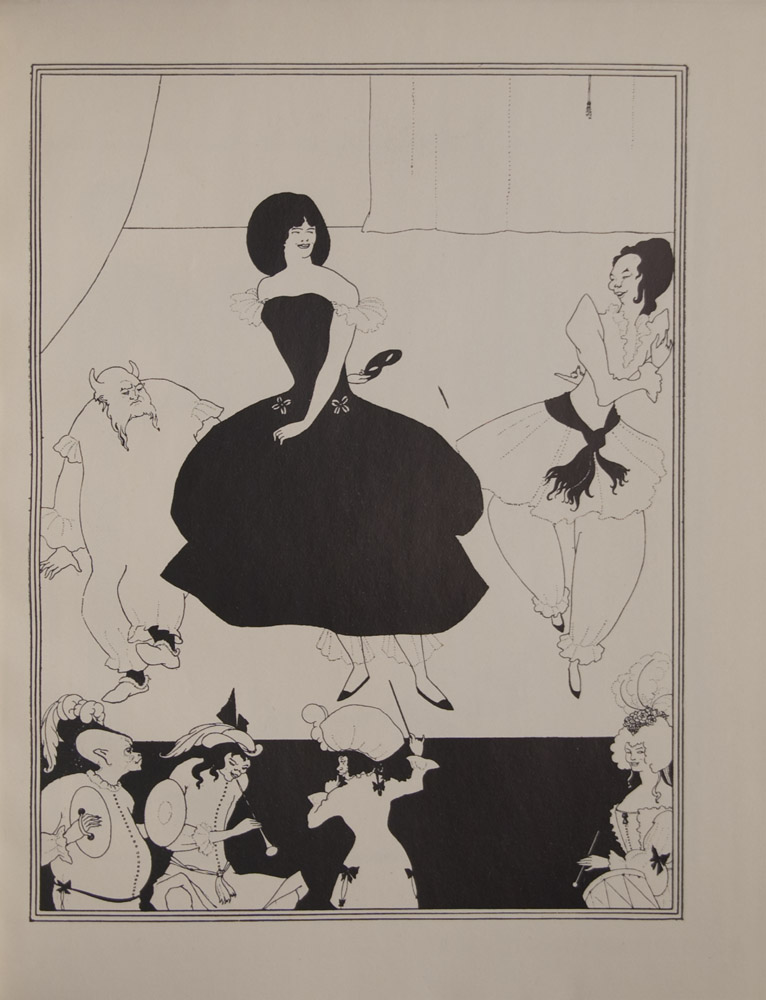

III. The Comedy-Ballet

of

Marionettes . Aubrey Beardsley . . 85 .

IV. The Comedy-Ballet of Marionettes .

V. The Comedy-Ballet of Marionettes .

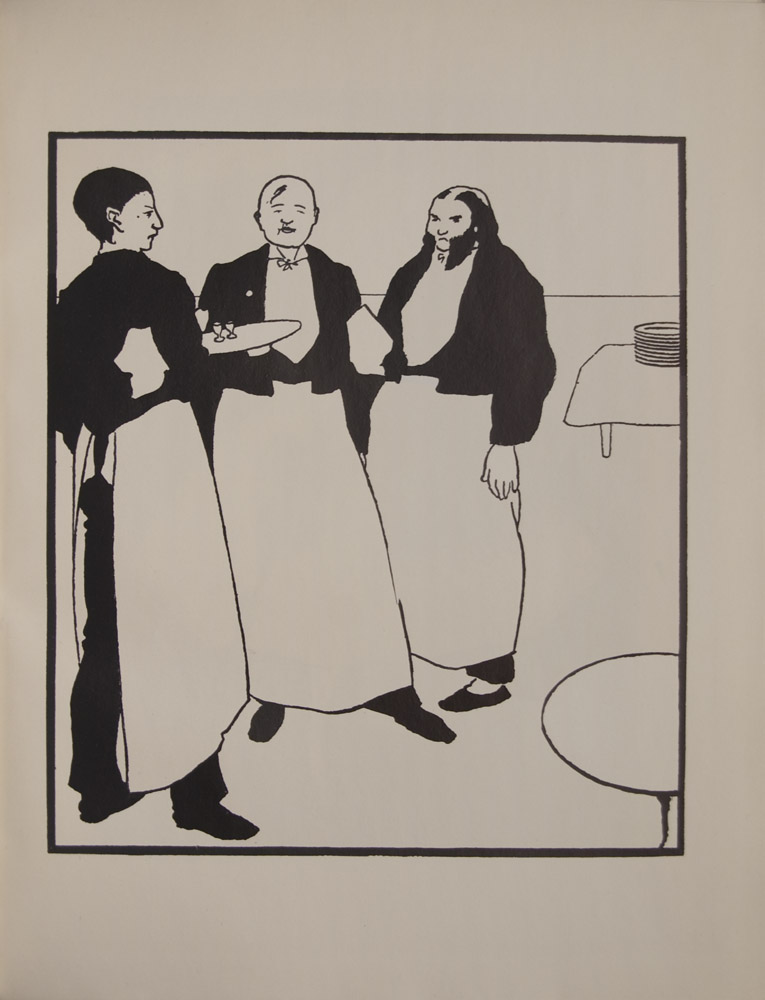

VI. Garcons de Cafe .

VII. The Slippers of

Cinderella . .

VIII. Portrait of Madame

Réjane . .

IX. A Landscape . . . Alfred

Thornton . . 117

X. Portrait of

Himself P. Wilson Steer . . 171

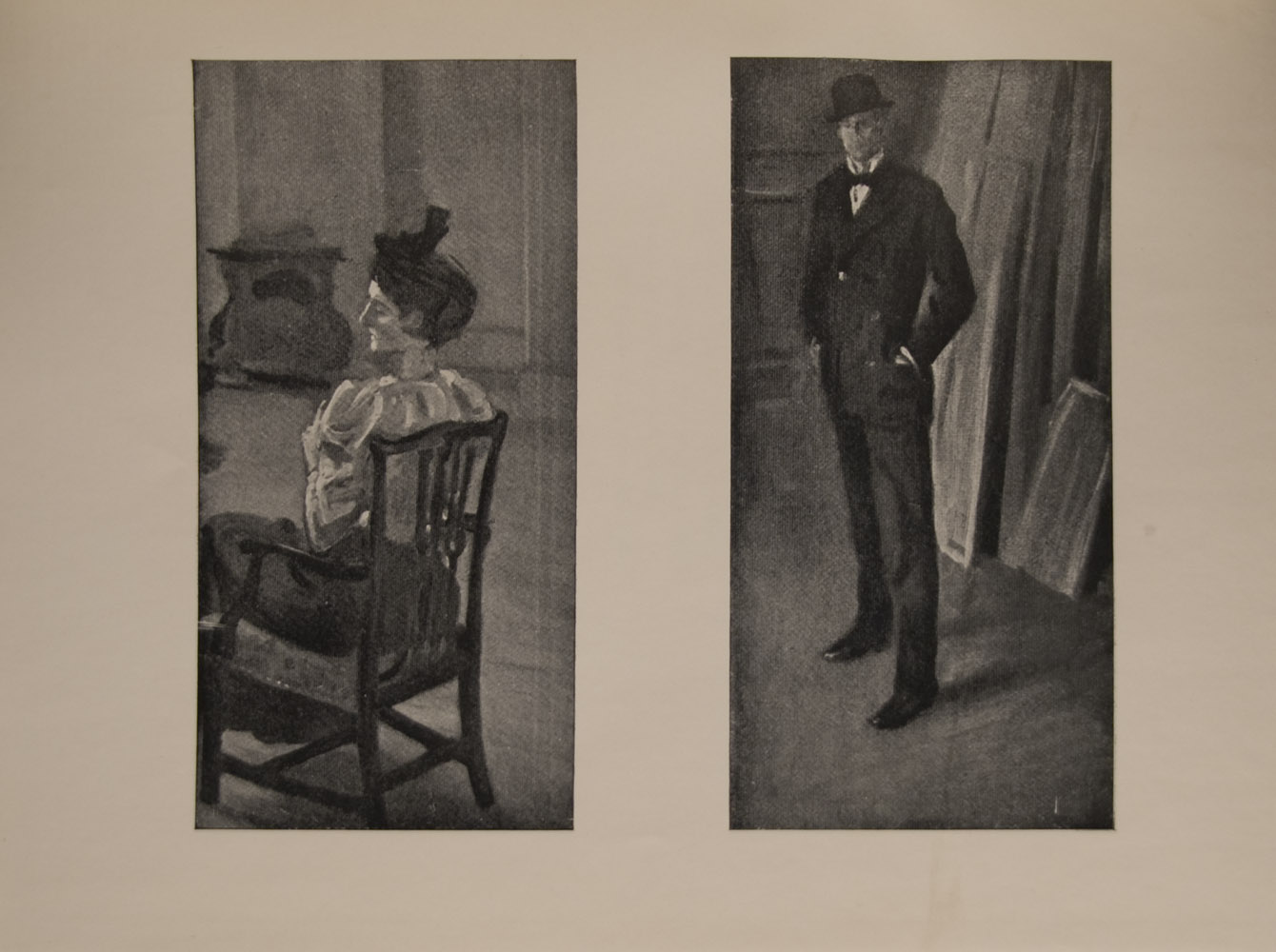

XI. A Lady . . .

XII. A

Gentleman . .

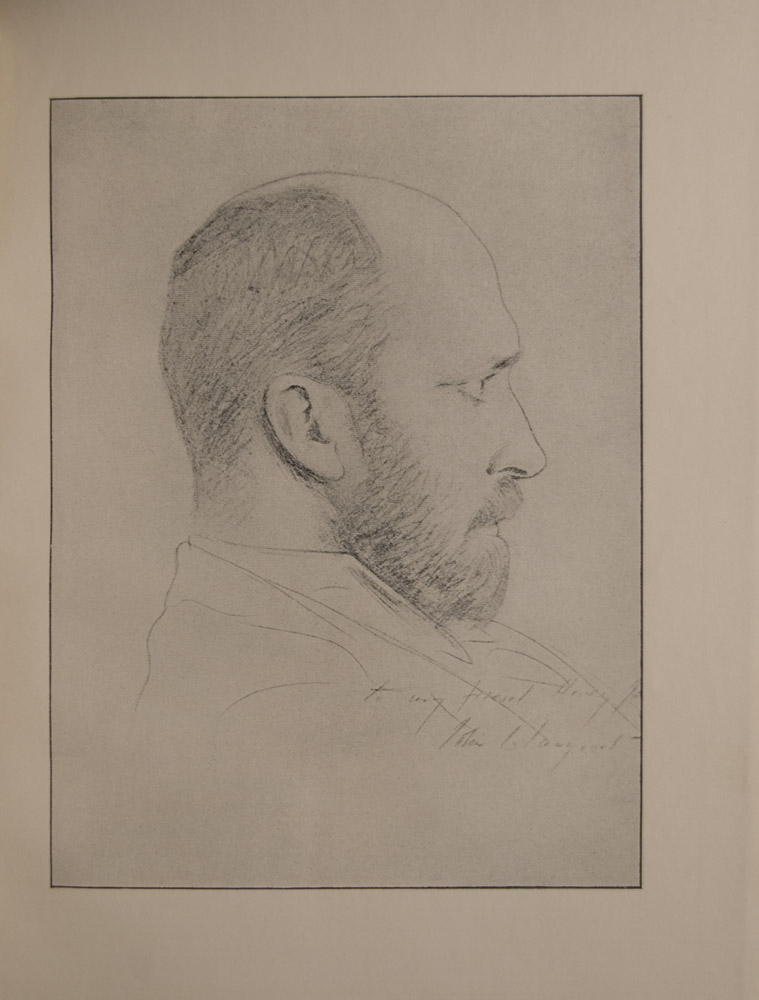

XIII. Portait of Henry

James John S. Sargent, A.R.A. .

191

XIV. A Girl Resting . . Sydney Adamson . . 207

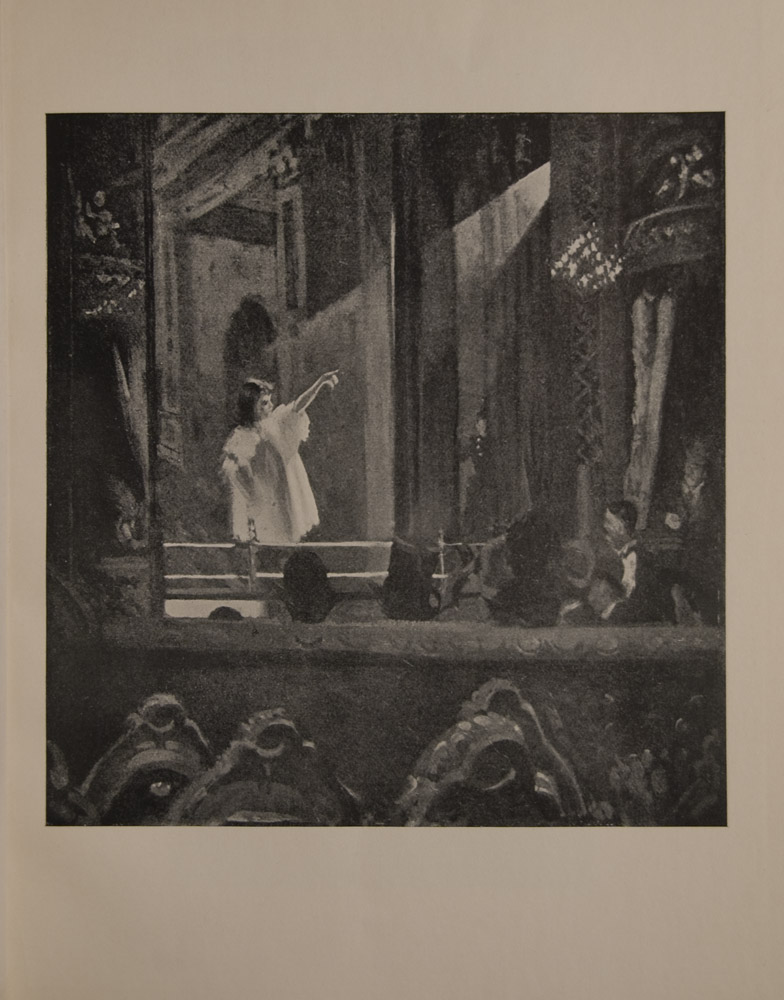

XV. The Old Bedford

Music

Hall

. . . Walter Sickert . . 220

XVI. Portrait of Aubrey

Beardsley

XVII. Ada Lundberg .

XVIII. An Idyll . . . W.

Brown Mac Dougal . 256

XIX. The Old Man’s

Garden. . . E.J. Sullivan . . . 270

XX. The Quick and the

Dead

XXI. A Reminiscence of

“The Transgressor” Francis Forster . . 278

XXII. A Study . . . . Bernhard

Sickert . . 285

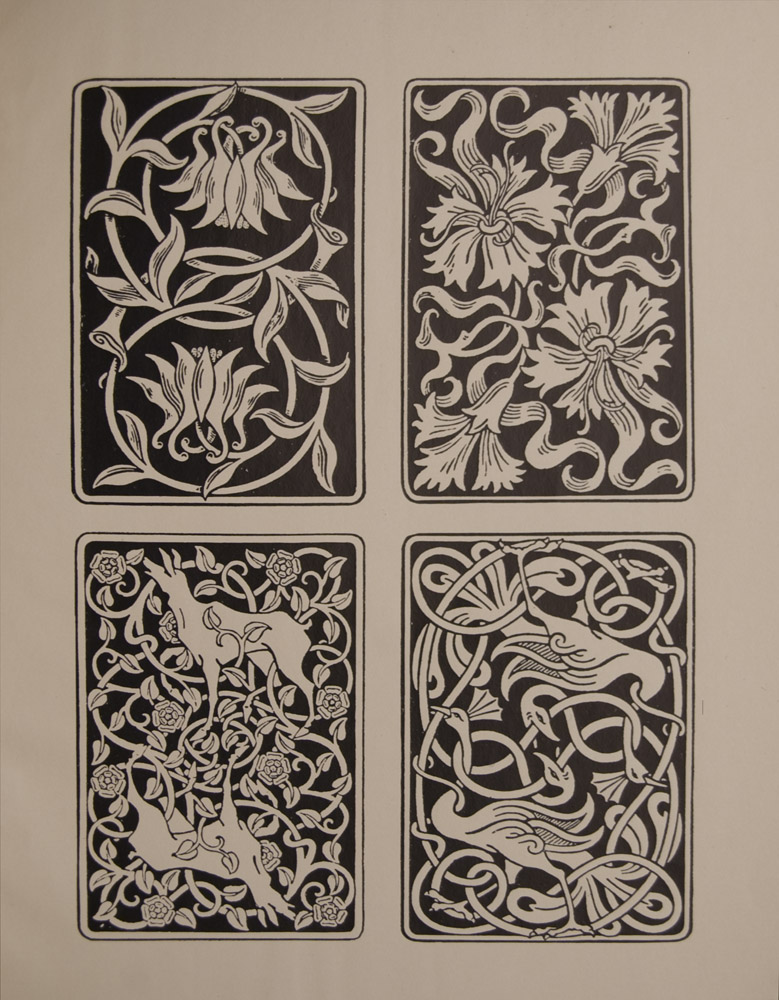

XXIII. For the Backs of

Playing

Cards

. . By Aymer Vallance . 361

Back Cover, by Aubrey Beardsley

Advertisements

The Gospel of Content

By Frederick Greenwood

How it was that I, being so young a man and not a very tactful

one,

was sent on such an errand is more than I should be

able to

explain. But many years ago some one came to me with

a request

that I should go that evening to a certain street at King’s

Cross, where would be found a poor lady in great distress; that I

should take a small sum of money which was given to me for the

purpose in a little packet which disguised all appearance of

coin,

present it to her as a ” parcel ” which I had been desired

to deliver,

and ask if there were any particular service that

could be done for

her. For my own information I was told that she

was a beautiful

Russian whose husband had barely contrived to get

her out of the

country, with her child, before his own arrest for

some deep

political offence of which she was more than cognisant,

and that

now she was living in desperate ignorance of his fate.

Moreover,

she was penniless and companionless, though not quite

without

friends ; for some there were who knew of her husband and

had a

little help for her, though they were almost as poor as

herself.

But none of these dare approach her, so fearful was she

of the

danger of their doing so, either to themselves or her

husband or

her

her child, and so ignorant of the perfect freedom that political

exiles could count upon in England. “Then,” said I,” what ex-

pectation is there that she will admit me, an absolute stranger

to

her, who may be employed by the police for anything she

knows

to the contrary ? ” The answer was : ” Of course that has

been

thought of. But you have only to send up your name, which,

in

the certainty that you would have no objection, has been

com-

municated to her already. Her own name, in England, is

Madame

Vernet.”

It was a Saturday evening in November, the air thick with

darkness

and a drizzling rain, the streets black and shining where

lamplight fell upon the mud on the paths and the pools in the

roadway, when I found my way to King’s Cross on this small

errand

of kindness. King’s Cross is a most unlovely purlieu at its

best,

which must be in the first dawn of a summer day, when the

innocence of morning smiles along its squalid streets, and the

people of the place, who cannot be so wretched as they look, are

shut within their poor and furtive homes. On a foul November

night nothing can be more miserable, more melancholy. One or

two

great thoroughfares were crowded with foot-passengers who

bustled

here and there about their Saturday marketings, under the

light

that flared from the shops and the stalls that lined the road-

way. Spreading on every hand from these thoroughfares, with

their

noisy trafficking so dreadfully eager and small, was a maze

of

streets built to be ” respectable ” but now run down into the

forlorn poverty which is all for concealment without any rational

hope of success. It was to one of these that I was directed—a

narrow silent little street of three-storey houses, with two

families

at least in every one of them.

Arrived at No. 17, I was admitted by a child after long delay,

and

by her conducted to a room at the top of the house. No

voice

voice responded to the knock at the room door, and none to

the

announcement of the visitor’s name ; but before I entered I

was

aware of a sound which, though it was only what may be

heard in

the grill-room of any coffee-house at luncheon time, made

me feel

very guilty and ashamed. For the last ten minutes I had

been

gradually sinking under the fear of intrusion—of intrusion

upon

grief, and not less upon the wretched little secrets of poverty

which pride is so fain to conceal ; and now these splutterings of a

frying-pan foundered me quite. What worse intrusion could

there be than to come prying in upon the cooking of some poor

little meal ?

Too much embarrassed to make the right apology (which, to

be right,

would have been without any embarrassment at all) I

entered the

room, in which everything could be seen in one

straightforward

glance : the little square table in the centre, with

its old

green cover and the squat lamp on it, the two chairs, the

dingy

half carpet, the bed wherein a child lay asleep in a lovely

flush

of colour, and the pale woman with a still face, and with the

eyes that are said to resemble agates, standing before the

hearth.

Under the dark cloud of her hair she looked the very

picture of

Suffering—Suffering too proud to complain and too

tired to speak.

Beautiful as the lines of her face were, it was

white as ashes and

spoke their meaning ; but nothing had yet

tamed the upspringing

nobility of her tall, slight, and yet

imperious form.

Receiving me with the very least appearance of curiosity or any

other kind of interest, but yet with something of proud

constraint

(which I attributed too much, perhaps, to the untimely

frying-

pan), she waved her hand toward the farther chair of the

two, and

asked to be excused from giving me her attention for a

moment.

By that she evidently meant that otherwise her supper

would be

spoiled. It is not everything that can be left to cook

unattended ;

and

and since this poor little supper was a piece of fish scarce bigger

than her hand, it was all the more likely to spoil and the less

could be spared in damage. So I quietly took my seat in a

position

which more naturally commanded the view out of window

than or

the cooking operations, and waited to be again

addressed.

On the mantel-board a noisy little American clock ticked as it

its

mission was to hurry time rather than to measure it, the frying-

pan fizzed and bubbled without any abatement of its usual habit

or any sense of compunction, now and then the child tossed upon

the bed from one pretty attitude to another ; and that was all

that

could be heard, for Madame Vernet’s movements were as silent

as

the movements of a shadow. In almost any part of that

small

room she could be seen without direct looking; but at a

moment

when she seemed struck into a yet deeper silence, and

because of

it, I ventured to turn upon her more than half an eye.

Standing

rigidly still, she was staring at the door in an

intensity of listening

that transfigured her. But the door was

closed, and I with the

best of hearing directed to the same place

could detect no new

sound : indeed, I dare swear that there was

none. It was merely

accidental that just at this moment the

child, with another toss of

the lovely black head, opened her

eyes wide ; but it deepened the

impressiveness of the scene when

her mother, seeing the little one

awake, placed a finger on her

own lips as she advanced nearer to

the door. The gesture was for

silence, and it was obeyed as if in

understood fear. But still

there was nothing to be heard without,

unless it were a push of

soft drizzle against the window-panes.

And this Madame Vernet

herself seemed to think when, after a

little while, she turned

back to the fire—her eyes mere agates

again which had been all

ablaze.

Stooping to the fender, she had now got her fish into one warm

plate, and had covered it with another, and had placed it on the

broad

broad old-fashioned hob of the grate to keep hot (as I surmised)

while she spoke with and got rid of me, when knocking was heard

at the outer door, a pair or hasty feet came bounding up the

stair, careless of noise, and in flashed a splendid radiant

creature

of a man in a thin summer coat, and literally drenched

to the skin.

It was Monsieur Vernet, whose real name ended in ” ieff.”

By daring

ingenuity, by a long chain of connivance yet more

hazardous, by

courage, effrontery, and one or two miraculous

strokes of good

fortune, he had escaped from the fortress to which

he had been

conveyed in secret and without the least spark of

hope that he

would ever be released. For many months no one

but himself and

his jailers knew whether he was alive or dead : his

friends

inclined to think him the one thing or the other according

to

the brightness or the gloominess or the hour. Smuggled into

Germany, and running thence into Belgium, he had landed in

England the night before ; and walking the whole distance to

London, with an interval of rour hours’ sleep in a cartshed, he

contrived to bring home nearly all of the four shillings with

which he started.

But these particulars, it will be understood, I did not learn

till

afterwards. For that evening my visit was at an end from

the

moment (the first of his appearance) when Vernet seized his

wife

in his arms with a partial resemblance to murder. Un-

observed, I

placed my small packet on the table behind the lamp,

and then

slipped out ; but not without a last view of that affecting

”

domestic interior,” which showed me those two people in a

relaxed embrace while they made me a courteous salute in response

to another which was all awkwardness, their little daughter stand-

ing up on the bed in her night-gown, patiently yet eagerly

waiting to be noticed by her father. In all likelihood she had

not

to wait long.

This

This was the beginning of my acquaintance with a man who

had a

greater number of positive ideas than any one else that ever

I

have known, with wonderful intrepidity and skill in expound-

ing

or defending them. However fine the faculties of some

other

Russians whom I have encountered, they seemed to move

in a

heavily obstructive atmosphere ; Vernet appeared to be oppressed

by none. His resolutions were as prompt as his thought ; what-

ever resourse he could command in any difficulty, whether the

least or the greatest, presented itself to his mind instantly, with

the occasion for it ; and every movement of his body had the

same

quickness and precision. His pride, his pride of

aristocracy, could

tower to extraordinary heights ; his

sensibility to personal slights

and indignities was so trenchant

that I have seen him white and

quivering with rage when he

thought himself rudely jostled by a

fellow-passenger in a

crowded street. And yet any comrade in

conspiracy was his

familiar if he only brought daring enough

into the common

business ; and wife, child, fortune, the exchange

of ease for the

most desperate misery, all were put at stake for

the sake of the

People and at the call of their sorrows and

oppressions. And of

one sort of pride he had no sense whatever—

fine gentleman as he

was, and used from his birth to every refine-

ment of service and

luxury : no degree of poverty, nor any

blameless shift for

relieving it, touched him as humiliating. Priva-

tion, whether

for others or himself, angered him ; the contrast

between

slothful wealth and toiling misery enraged him ; but he

had no

conception of want and its wretched little expedients as

mortifying.

For example. It was in November, that dreary and inclement

month,

when he began life anew in England with a capital or

three

shillings and sevenpence. It was a bleak afternoon in

December,

sleet lightly falling as the dusk came on and melting

as

as it fell, when I found him gathering into a little basket what

looked in the half-darkness like monstrous large snails. With as

much indifference as if he were offering me a new kind of

cigarette, Vernet put one of these things into my hand, and I

saw

that it was a beautifully-made miniature sailor’s hat. The

strands of which it was built were just like twisted brown straw

to the eye, though they were of the smallness of packthread ; and

a neat band of ribbon proportionately slender made all complete.

But what were they for ? How were they made ? The answer

was that the design was to sell them, and that they were made of the

cords—more artistically twisted and more neatly waxed than

usual

—that shoemakers use in sewing. As for the bands, Madame

Vernet had amongst her treasures a cap which her little daughter

had worn in her babyhood ; and this cap had close frills of

lace,

and the frills were inter-studded with tiny loops of

ribbon—a

fashion of that time. There were dozens of these tiny

loops, and

every one of them made a band for Vernet’s little toy

hats.

Perhaps in tenderness for the mother’s feelings, he would

not let her

turn the ribbons to their new use, but had applied

them himself;

and having spent the whole of a foodless day in the

manufacture

of these little articles, he was now about to go and

sell them. He

had selected his ” pitch ” in a flaring bustling

street a mile away ;

and he asked me (” I must lose no time,” he

said) to accompany

him in that direction. I did so, with a cold

and heavy stone in

my breast which I am sure had no counterpart

in his own. As he

marched on, in his light and firm soldierly

way, he was loud in praise

of English liberty : at such a moment

that was his theme. Arrived

near his ” pitch,” he bade me good-night with no abatement of

the high and easy air that was natural to him ; and though I

instantly turned back of course, I knew that at a few paces farther

the violently proud man moved off the pathway into the gutter,

and

and stood there till eleven o clock ; for not before then did he

sell

the last of his little penny hats. Another man, equally

proud,

might have done the same thing in Vernet’s situation, but

not

with Vernet’s absolute indifference to everything but the

coldness

of the night and the too-great stress of physical want.

But this Russian revolutionist was far too capable and versatile

a

man to lie long in low water. He had a genius for industrial

chemistry which soon got him employment and from the sufficiently

comfortable made him prosperous by rapid stages. But what of

that ? Before long another wave of political disturbance rose in

Europe ; Russia, Italy, France,’twas all one to Vernet when his

sympathies were roused ; and after one or two temporary

disappear-

ances he was again lost altogether. There was no news

of him for

months ; and then his wife, who all this while had

been sinking back

into the pallid speechless deadness of the

King’s Cross days,

suddenly disappeared too.

II

For more than thirty years—a period of enormous change in all

that

men do or think—no word of Vernet came to my know-

ledge. But

though quite passed away he was never forgotten long,

and it was

with an inrush of satisfaction that, a year or two ago, I

received this letter from him :

“. . . . I have been reading the ——Review, and

it determines

me to solicit a pleasure which I have been at

full-cock to ask for

many times since I returned to England in

1887. Let us meet. I

have something to say to you. But let us

not meet in this horrifically

large and noisy town. You know

Richmond ? You know the Star

and

and Garter Hotel there ? Choose a day when you will go to find

me

in that hotel. It shall be in a quiet room looking over the trees

and the river, and there we will dine and sit and talk over our

dear

tobacco in a right place.

“To say one word of the past, that you may know and then forget.

Marie is gone—gone twelve years since ; and my daughter, gone. I

do not speak of them. And do not you expect to find in me any

more the Vernet of old days.”

Nor was he. The splendidly robust and soldierly figure of

thirty-five had changed into a thin, fine-featured old man, above

all things gentle, thoughtful, considerate. Except that there was

no suggestion of a second and an inner self in him, he might

have

been an ecclesiastic ; as it was, he looked rather as if he

had been all

his life a recluse student of books and state

affairs.

It was a good little dinner in a bright room overlooking the

garden

; and it was served so early that the declining sunshine of

a

June day shone through our claret-glasses when coffee was brought

in. Our first talk was of matters of the least importance—our

own changing fortunes over a period of prodigious change for the

whole world. From that personal theme to the greater mutations

that affect all mankind was a quick transition ; and we had not

long been launched on this line of talk before I found that in

very truth nothing had changed more than Vernet himself. It

was the story of Ignatius Loyola over again, in little and with

a

difference.

“Yes,” said he, my mind filling with unspoken wonder at this

during

a brief pause in the conversation, ” Yes, prison did me

good.

Not in the rough way you think, perhaps, as of taking

nonsense

out of a man with a stick, but as solitude. Strict

Catholics go

into retreat once a year, and it does them good as

Catholics:

whether otherwise I do not know, but it is possible.

The Yellow Book—Vol. II. B

You

You have a wild philosopher whom I love ; and wild philosophers

are

much the best. In them there is more philosophic sport, more

surprise, more shock; and it is shock that crystallises. They

startle the breath into our own unborn thoughts—thoughts formed

in the mind, you know, but without any ninth month for them :

they wait for some outer voice to make them alive. Well, once

upon a time I heard this philosopher, your Mr. Ruskin, say that

only the most noble, most virtuous, most beautiful young men

should be allowed to go to the war ; the others, never. And he

maintained it—ah ! in language from some divine madhouse in

heaven. But as to that, it is a great objection that your army is

already small. Yet of this I am nearly sure ; it is the wrong

men

who go to gaol. The rogues and thieves should give place to

honest

men—honest reflective men.

Every advantage of that conclusive

solitude is lost on

blackguard persons and is mostly turned to harm.

For them

prescribe one, two, three applications of your cat-o’-nine

tails——”

” There is knout like it ! ” said I, intending a severity of retort

which I hoped would not be quite lost in the pun.

“——and then a piece of bread, a shilling, and dismissal to the

most

devout repentance that brutish crime is ever acquainted with,

repentance in stripes. Imprisonment is wasted on persons of so

inferior character. Waste it not, and you will have accommodation

for wise men to learn the monk’s lesson (did you ever think it

ah

foolishness?) that a little imperious hardship, a time of

seclusion

with only themselves to talk to themselves, is most

improving.

For statesmen and reformers it should be an

obligation.”

” And according to your experience what is the general course

of

the improvement ? In what direction does it run ? ”

” At best ? In sum total ? You know me that l am no monk

nor lover

of monks, but I say to you what the monk would say

were

were he still a man and intelligent. The chief good is rising

above

petty irritation, petty contentiousness ; it is patience with

ills that must last long; it is choosing to

build out the east wind

instead of running at it with a sword.”

“And, if I remember aright, you never had that sword out of

your

hand.”

“From twenty years old to fifty, never out of my hand. But

there

were excuses—no, but more than excuses ; remember that

that was

another time. Now how different it is, and what satisfac-

tion

to have lived to see the change ! ”

” And what is the change you are thinking of! “

” One that I have read of—only he must not flatter himself that

he

alone could find it out—in some Review articles of an old

friend

of Vernet’s whose portrait is before me now.” And then,

a little

to my distress, but more to my pleasure, he quoted from two

or

three forgotten papers of mine on the later developments of

social humanity, the “evolution of goodness ” in the relations

of men to each other, the new, great and rapid extension of

brotherly kindness ; observations and theories which were welcomed

as novel when they were afterwards taken up and enlarged upon

by Mr. Kidd in his book on ” Social Evolution.”

” For an ancient conspirator and man of the barricades,” con-

tinued Vernet, by this time pacing the room in the dusk which he

would not allow to be disturbed, ” for a blood-and-iron man who

put all his hopes of a better day for his poor devils of fellow-

creatures on the smashing of forms and institutions and the sub-

stitution of others, I am rather a surprising convert, don’t you

think ? But who could know in those days what was going on

in

the common stock of mind by—what shall we call it ? Before

your

Darwin brought out his explaining word ‘evolution’ I should

have

said that the change came about by a sort of mental chemistry ;

that

that it was due to a kind of chemical ferment in the mind, unsus-

pected till it showed entirely new growths and developments.

And

even now, you know, I am not quite comfortable with

‘evolution’

as the word for this sudden spiritual advance into

what you call

common kindness and more learned persons call

‘altruism.’ It

does not satisfy me, ‘evolution.'”

” But you can say why it doesn’t, perhaps.”

” Nothing, more, I suppose, than the familiar association of

‘evolution’ with slow degrees and gradual processes. Evolution

seems to speak the natural coming-out of certain developments

from certain organisms under certain conditions. The change comes,

and you see it coming ; and you can look back and trace its

advance. But here? The human mind has been the same for ages ;

subject to the same teaching ; open to the same persuasions and

dissuasions ; as quick to see and as keen to think as it is now

; and

all the while it has been staring on the same cruel scenes

of misery

and privation : no, but very often worse. And then,

presto ! there

comes a sudden growth of fraternal sentiment all

over this field of

the human mind ; and such a growth that if it

goes on, if it goes on

straight and well, it will transform the

whole world. Transform

its economies ?—it will change its very

aspect. Towns, streets,

houses will show the difference ; while

as to man himself, it

will make him another being. For this is

neither a physical

nor a mere intellectual advance. As for that,

indeed, perhaps

the intellectual advance hasn’t very much

farther to go on its

own lines, which are independent of

morality, or of goodness

as I prefer to say : the simple word !

Well, do you care if

evolution has pretty nearly done with

intellect ? Would you

mind if intellect never made a greater

shine ? Will your heart

break if it never ascends to a higher

plane than it has reached

already ? ”

“Not

” Not a bit ; if, in time, nobody is without a good working share

of what intellect there is amongst us.”

” No, not a bit ! Enough of intellect for the good and happi-

ness

of mankind if we evolve no more of it. But this is another

thing

! This is a spiritual evolution, spiritual

advance and develop-

ment—a very different thing ! Mark you,

too, that it is not

shown in a few amongst millions, but is

common, general. And

though, as you have said, it may perish at

its beginnings, trampled

out by war, the terrible war to come

may absolutely confirm it.

For my part, I don’t despair of its

surviving and spreading even

from the battle-field. It is your

own word that not only has the

growth of common kindness been

more urgent, rapid and general

this last hundred years than was

ever witnessed before in the whole

long history of the world,

but it has come out as strongly in

making war as in making

peace. It is seen in extending to

foes a benevolence which not

long ago would have been thought

ludicrous and even unnatural.

Why, then, if that’s so, the feeling

may be furthered and

intensified by the very horrors of the next

great war, such

horrors as there must be ; and—God knows !

God

knows !—but from this beginning the spiritual nature of man

may

be destined to rise as far above the rudimentary thing it is

yet (I

think of a staggering blind puppy) as King Solomon’s wits

were

above an Eskimo’s.”

” Still the same enthusiast,” I said to myself, ” though with so

great a difference.” But what struck me most was the reverence

with which he said ” God knows ! ” For the coolest Encyclopedist

could not have denied the existence of God with a more settled

air than did ” the Vernet of old days.”

” And yet,” so he went on, ” were the human race to become

all-righteous in a fortnight, and to push out angels wings from its

shoulders, every one ! every one ! all together on Christmas

Day,

it

it would still be the Darwinian process. Yes, we must stick to it,

that it is evolution, I suppose, and I’m sure it contents me well

enough. What matter for the process ! And yet do you know

what I think ?

Lights had now been brought in by the waiter—a waiter who

really

could not understand why not. But we sat by the

open window

looking out upon the deepening darkness of the

garden, beyond

which the river shone as if by some pale effulgence

of its own,

or perhaps by a little store of light saved up from the

liberal

sunshine of the day.

“Do you know what I think ?” said Vernet, with the look of

a man

who is about to confess a weakness of which he is ashamed.

” I

sometimes think that if I were of the orthodox I should draw

an

argument for supernatural religion, against your strict materi-

alists, from this sudden change of heart in Christian countries.

For that is what it is. It is a change of heart ; or, if you like to

have it so, of spirit ; and the remarkable thing is that it is

nothing

else. Whether it lasts or not, this

awakening of brotherliness cannot

be completely understood

unless that is understood. What else

has changed, these hundred

years ? There is no fresh discovery of

human suffering, no new

knowledge of the desperate poverty and toil

of so many of our

fellow-creatures: nor can we see better with

our eyes, or

understand better what we hear and see. This that

we are talking

about is a heart-growth, which, as we know, can

make the lowliest

peasant divine ; not a mind-growth, which can

be splendid in the

coldest and most devilish man. Well, then,

were I of the

orthodox I should say this. When, after many

generations, I see

a traceless movement of the spirit of man

like the one we are

speaking of—a movement which, if it gains

in strength and goes

on to its natural end, will transfigure human

society and make

it infinitely more like heaven—I think the

divine

divine influence upon the development of man as a spirit may be

direct and continuous ; or, it would be better to say, not without

repetition.”

Vernet had to be reminded that the intellectual development of

man

had also shown itself in sudden starts and rushes toward per-

fection—now in one land, now in another ; and never with an

appearance of gradual progress, as might be expected from the nature

of things. And therefore nothing in the spiritual advance which

is declared by the sudden efflorescence of ” altruism ”

dissociates

it from the common theory of evolution. This he was

forced to

admit. ” I know,” he replied ; ” and as to

intellectual develop-

ment showing itself by starts and rushes,

it is very obvious.” But

though he made the admission, I could

see that he preferred belief

in direct influence from above. And

this was Vernet !—a most

unexpected example of that Return to

Religion which was not so

manifest when we talked together as it

is to-day.

” You see, I am a soldier,” he resumed, ” and a soldier born and

bred does not know how to get on very long without feeling the

presence of a General, a Commander. That I find as I grow

old ;

my youth would have been ashamed to acknowledge the

sentiment.

And for its own sake, I hope that Science is becoming

an old

gentleman too, and willing to see its youthful confidence in

the

destruction of religious belief quite upset. For upset it cer-

tainly will be, and very much by its own hands. Most of the new

professors were sure that the religious idea was to perish at last in

the light of scientific inquiry. None of them seemed to suspect

what I remember to have read in a fantastic magazine article two

or three years ago, that unbelief in the existence of a

providential

God, the dissolution of that belief, would not

retard but probably

draw on more quickly the greater and yet

unfulfilled triumphs of

Christ on earth. Are you surprised at

that ? Certainly it is not

the

the general idea of what unbelief is capable of. ‘And what,’ says

some one in the story, ‘what are those greater triumphs ?’ To

which the answer is : ‘The extension of charity, the diffusion of

brotherly love, greed suppressed, luxury shameful, service and

self-

sacrifice a common law’—something like what we see already

between mother and child, it was said. Now what do you think

of that as a consequence of settled unbelief? As for Belief, we

must allow that that has not done

much to bring on the greater

triumphs of Christianity.”

” And how is Unbelief to do this mighty work ? ” said I.

” You would like to know ! Why, in a most natural way, and

not at

all mysterious. But if you ask in how long a time——!

Well, it is

thus, as I understand. What the destruction of religious

faith

might have made of the world centuries ago we cannot tell ;

nothing much worse, perhaps, than it was under Belief, for belief

can exist with little change of heart. But these are new times.

Unbelief cannot annihilate the common feeling of humanity. On

the contrary, we see that it is just when Science breaks

religion

down into agnosticism that a new day of tenderness for

suffering

begins, and poverty looks for the first time like a

wrong. And

why ? To answer that question we should remember what

cen-

turies of belief taught us as to the place of man on earth

in the

plan of the Creator. This world, it was a ‘scene of

probation.’

The mystery of pain and suffering, the burdens of

life apportioned

so unequally, the wicked prosperous, goodness

wretched, innocent

weakness trodden down or used up in starving

toil—all this was

explained by the scheme of probation. It was

only for this life ;

and every hour of it we were under the eyes

of a heavenly Father

who knows all and weighs all ; and there

will be a future of

redress that will leave no misery

unreckoned, no weakness uncon-

sidered, no wrong uncompensated

that was patiently borne. Don’t

you

you remember ? And how comfortable the doctrine was ! How

entirely

it soothed our uneasiness when, sitting in warmth and

plenty, we

thought of the thousands of poor wretches outside !

And it was a

comfort for the poor wretches too, who believed

most when they

were most miserable or foully wronged that in

His own good time

God would requite or would avenge.

” Very well. But now, says my magazine sermoniser, sup-

pose this

idea of a heavenly Father a mistake and probation a

fairy tale;

suppose that there is no Divine scheme of redress

beyond the

grave : how do we mortals stand to each other then ?

How do we

stand to each other in a world empty of all promise

beyond it ?

What is to become of our scene-of-probation com-

placency, we who

are happy and fortunate in the midst of so much

wrong ? And if

we do not busy ourselves with a new dispensa-

tion on their

behalf, what hope or consolation is there for the

multitude of

our fellow-creatures who are born to unmerited

misery in the

only world there is for any of us ? It is clear that

if we must

give up the Divine scheme of redress as a dream,

redress is an

obligation returned upon ourselves. All willnot be

well in

another world : all must be put right in this world or no-

where

and never. Dispossessed of God and a future life, mankind

is

reduced to the condition of the wild creatures, each with a

natural right to ravage for its own good. If in such conditions

there is a duty of forbearance from ravaging, there is a duty of

helpful surrender too ; and unbelief must teach both duties, unless

it would import upon earth the hell it denies. ‘Unbelief is a

call

to bring in the justice, the compassion, the oneness of

brother-

hood that can never make a heaven for us elsewhere.’ So

the

thing goes on ; the end of the argument being that in this

way

unbelief itself may turn to the service of Heaven and do the

work

of the believer’s God. More than that : in the doing of it

the

spiritual

spiritual nature of man must be exalted, step by step. That may

be

its way of perfection. On that path it will rise higher and

higher into Divine illuminations which have touched it but very

feebly as yet, even after countless ages of existence.

” Do you recognise these speculations ? ” said Vernet, after a

silence.

I recognised them well enough, without at all anticipating that

so

much of them would presently re-appear in the formal theory

of

more than one social philosopher.

There was a piano in the little room we dined in. For a

minute or

two Vernet, standing with his cigar between his lips,

went

lightly over the keys. The movement, though extremely

quick, was

wonderfully soft, so that he had not to raise his voice

in

saying :

” I have an innocent little speculation of my own. How long

will it

be before this spiritual perfectioning is pretty near accom-

plishment ? Two thousand years ? One thousand years ?

Twenty

generations at the least ! Ah, that is the despair of us

poor

wretches of to-day and to-morrow. Well, when the time

comes I

fancy that an entirely new literature will have a new

language.

There will certainly be a new literature if ever spiritual

progress equals intellectual progress. The dawning of conceptions

as yet undreamt of, enlightenments higher than any yet attained

to, may be looked for, I suppose, as in the natural order of

things ;

and even without

extraordinary revelations to the spirit, the spiritual

advance

must have an enormous effect in disabusing, informing

and

inspiring mental faculty such as we know it now. And

meanwhile ?

Meanwhile words are all that we speak with, and

how weak are

words ? Already there are heights and depths of

feeling which

they are hardly more adequate to express than the

dumbness of

the dog can express his love for his master. Yet

there

there is a language that speaks to the deeper thought and finer

spirit in us as words do not—moving them profoundly though

they

have no power of articulate response. They heave and struggle

to

reply, till our breasts are actually conscious of pain sometimes ;

but—no articulate answer. Do you recognise —— ?”

I pointed to the piano with the finger of interrogation.

” Yes,” said Vernet, with a delicate sweep of the keyboard,

” it is

this ! It is music ; music, which is felt to be the most

subtle,

most appealing, most various of tongues even while we

know that

we are never more than half awake to its pregnant

meanings, and

have not learnt to think of it as becoming the last

perfection

of speech. But that may be its appointed destiny. No,

I don t

think so only because music itself is a thing of late, speedy

and splendid development, coming just before the later diffusion of

spiritual growth. Yet there is something in that, something

which an evolutionist would think apposite and to be expected.

There is more, however, in what music is—a voice always under-

stood to have powerful innumerable meanings appealing to we

know not what in us, we hardly know how ; and more, again, in

its being an exquisite voice which can make no use of reason,

nor

reason of it ; nor calculation, nor barter, nor anything but

emotion and thought. The language we are using now, we two,

is animal language by direct pedigree, which is worth

observation

don’t you think ? And, for another thing, when it

began it had

very small likelihood of ever developing into what

it has become

under the constant addition of man’s business in

the world and

the accretive demands of reason and speculation.

And the poets

have made it very beautiful no doubt ; yes, and

when it is most

beautiful it is most musical, please observe :

most beautiful, and

at the same time most meaning. Well, then !

A new nature,

new needs. What do you think ? What do you say

against

music

music being wrought into another language for mankind, as it

nears

the height of its spiritual growth ? “

“I say it is a pretty fancy, and quite within reasonable speculation.”

” But yet not of the profoundest consequence,” added Vernet,

coming

from the piano and resuming his seat by the window.

“No ; but what is of consequence is the cruel tedium of these

evolu-

tionary processes. A thousand years, and how much movement

?

” Remember the sudden starts towards perfection, and that the

farther we advance the more we may be able to help.”

“Well, but that is the very thing I meant to say. Help is not

only

desirable, it is imperatively called for. For an unfortunate

offensive movement rises against this better one, which will be

checked,

or perhaps thrown back altogether, unless the stupid

reformers who

confront the new spirit of kindness with the

highwayman’s demand

are brought to reason. What I most willingly

yield to friend and

brother I do not choose to yield to an

insulting thief ; rather

will I break his head in the cause of

divine Civility. Robbery is

no way of righteousness, and your

gallant reformers who think it

a fine heroic means of bringing

on a better time for humanity should

be taught that some devil

has put the wrong plan into their heads.

It is his way of

continuing under new conditions the old conflict

of evil and

good.”

“But taught ! How should these so-earnest ones be taught ?”

” Ah, how ! Then leave the reformers ; and while they inculcate

their mistaken Gospel of Rancour, let every wise man preach the

Gospel of Content.”

“Content—with things as they are ?”

“Why, no, my friend; for that would be preaching content

with

universal uncontent, which of course cannot last into a

reign of

wisdom and peace. But if you ask me whether I mean

content with

a very very little of this world’s goods, or even con-

tentment

tentment in poverty, I say yes. There will be no better day till

that gospel has found general acceptance, and has been taken into

the common habitudes of life. The end may be distant enough ;

but it is your own opinion that the time is already ripe for the

preacher, and if he were no Peter the Hermit but only another,

another—— ”

” Father Mathew, inspired with more saintly fervour—— “

“Who knows how far he might carry the divine light to which

so many

hearts are awakening in secret ? This first Christianity,

it was

but ‘the false dawn.’ Yes, we may think so.”

Here there was a pause for a few moments, and then I put in a

word

to the effect that it would be difficult to commend a gospel

of

content to Poverty.

“But,” said Vernet, ” it will be addressed more to the rich and

well-to-do, as you call them, bidding them be content with enough.

Not forbidding them to strive for more than enough—that would

never do. The good of mankind demands that all its energies

should be maintained, but not that its energies should be meanly

employed in grubbing for the luxury that is no enjoyment but

only

a show, or that palls as soon as it is once enjoyed, and

then is no

more felt as luxury than the labourer’s second pair

of boots or the

mechanic’s third shirt a week. For the men of

thousands per

annum the Gospel of Content would be the wise,

wise, wise old

injunction to plain living and high thinking,

only with one addi-

tion both beautiful and wise : kind thinking,

and the high and the

kind thinking made good in deed. And it

would work, this gospel ;

we may be sure of it already. For

luxury has became common ; it

is

being found out. Where there was one person at the beginning

of

the century who had daily experience of its fatiguing disappoint-

ments, now there are fifty. Like everything else, it loses dis-

tinction by coming abundantly into all sorts of hands ; and mean-

while

while other and nobler kinds of distinction have multiplied and

have gained acknowledgment. And from losing distinction—

this you

must have observed—luxury is becoming vulgar ; and I

don’t know

why the time should be so very far off when it will be

accounted

shameful. Certain it is that year by year a greater

number of

minds, and such as mostly determine the currents of

social

sentiment, think luxury low ; without going

deeper than the

mere look of it, perhaps. These are hopeful

signs. Here is good

encouragement to stand out and preach a

gospel of content which

would be an education in simplicity,

dignity, happiness, and yet

more an education of heart and

spirit. For nothing that a man

can do in this world works so

powerfully for his own spiritual good

as the habit of sacrifice

to kindness. It is so like a miracle that it

is, I am sure, the

one way—the one way appointed by the laws or

our spiritual

growth.

“Yes, and what about preaching the gospel of content to Poverty ?

Well, there we must be careful to discriminate—careful to dis-

entangle poverty from some other things which are the same thing

in the common idea. Say but this, that there must be no content

with squalor, none with any sort of uncleanness, and poverty takes

its own separate place and its own unsmirched aspect. An honour-

able poverty, clear of squalor, any man should be able to endure

with a tranquil mind. To attain to that tranquillity is to

attain to

nobleness ; and persistence in it, though effort fail

and desert go

quite without reward, ennobles. Contentment in

poverty does not

mean crouching to it or under it. Contentment

is not cowardice,

but fortitude. There is no truer assertion of

manliness, and none

with more grace and sweetness. Before it can

have an established

place in the breast of any man, envy must

depart from it—envy,

jealousy, greed, readiness to take

half-honest gains, a horde of small

ignoble sentiments not only

disturbing but poisonous to the

ground

ground they grow in. Ah, believe me ! if a man had eloquence

enough, fire enough, and that command of sympathy that your

Gordon seems to have had (not to speak of a man like Mahomet or

to touch on more sacred names), he might do wonders for mankind

in a single generation by preaching to rich and poor the several

doctrines of the Gospel of Content. A curse on the mean

strivings, stealings, and hoardings that survive from our animal

ancestry, and another curse (by your permission) on the gaudy

vanities that we have set up for objects in life since we became

reasoning creatures.”

In effect, here the conversation ended. More was said, but nothing

worth recalling. Drifting back to less serious talk, we gossiped

till midnight, and then parted with the heartiest desire (I speak for

myself) of meeting soon again. But on our way back to town

Vernet

recurred for a moment to the subject of his discourse,

saying :

” I don’t make out exactly what you think now of the prospect

we

were talking of.”

My answer pleased him. ” I incline to think,” said I, ” what I

have

long thought : that if there is any such future for us, and I

believe there is, we of the older European nations will be nowhere

when it comes. In existence—yes, perhaps ; but gone down.

You see we are becoming greybeards already ; while you in Russia

are boys, with every mark of boyhood on you. You, you are a

new

race—the only new race in the world ; and it is plain that

you

swarm with ideas of precisely the kind that, when you come

to

maturity, may re-invigorate the world. But first, who knows

what

deadly wars ? ”

He pressed his hand upon my knee in a way that spoke a great

deal.

We parted, and two months afterwards the Vernet whose

real name

ended in ” ieff” was ” happed in lead.”

Poor Cousin Louis

By Ella D’Arcy

THERE stands in the Islands a house known as ” Les Calais.”

It has

stood there already some three hundred years, and

do judge from

its stout walls and weather-tight appearance,

promises to stand

some three hundred more. Built of brown

home-quarried stone, with

solid stone chimney-stacks and roof

of red tiles, its door is set

in the centre beneath a semi-circular

arch of dressed granite, on

the keystone of which is deeply cut

the date of construction

:

J V N I

1603

Above the date straggle the letters, L G M M, initials of the

forgotten names of the builder of the house and of the woman

he

married. In the summer weather of 1603 that inscription

was cut,

and the man and woman doubtless read it with pride and

pleasure

as they stood looking up at their fine new homestead.

They

believed it would carry their names down to posterity

when they

themselves should be gone ; yet there stand the

initials to-day,

while the personalities they represent are as lost to

memory as

are the builders graves.

At the moment when this little sketch opens, Les Calais had

belonged

belonged for three generations to the family of Renouf (pro-

nounced

Rennuf), and it is with the closing days of Mr. Louis

Renouf that

it purposes to deal. But first to complete the

description of the

house, which is typical of the Islands : hundreds

of such

homesteads placed singly, or in groups —then sharing in

one

common name— may be found there in a day’ s walk,

although it

must be added that a day’s walk almost suffices to

explore any

one of the Islands from end to end.

Les Calais shares its name with none. It stands alone, com-

pletely

hidden, save at one point only, by its ancient elms. On

either

side of the doorway are two windows, each of twelve small

panes,

and there is a row of five similar windows above. Around

the back

and sides of the house cluster all sorts of outbuildings,

necessary dependencies of a time when men made their own

cider

and candles, baked their own bread, cut and stacked their

own

wood, and dried the dung of their herds for extra winter fuel.

Beyond these lie its vegetable and fruit gardens, which again are

surrounded on every side by its many rich verg^es of pasture

land.

Would you find Les Calais, take the high road from Jacques-

le-Port

to the village of St. Gilles, then keep to the left of the

schools along a narrow lane cut between high hedges. It is a

cart

track only, as the deep sun-baked ruts testify, leading direct

from St. Gilles to Vauvert, and, likely enough, during the whole

of

that distance you will not meet with a solitary person. You

will

see nothing but the green running hedgerows on either hand,

the

blue-domed sky above, from whence the lark, a black pin-point

in

the blue, flings down a gush of song ; while the thrush you

have

disturbed lunching off that succulent snail, takes short

ground

flights before you, at every pause turning back an ireful

eye to

judge how much farther you intend to pursue him. He is

happy

The Yellow Book Vol. II. C

if

if you branch off midway to the left down the lane leading

straight

to Les Calais.

A gable end of the house faces this lane, and its one window in

the

days of Louis Renouf looked down upon a dilapidated farm-

and

stable-yard, the gate of which, turned back upon its hinges,

stood wide open to the world. Within might be seen granaries

empty of grain, stables where no horses fed, a long cow-house

crumbling into ruin, and the broken stone sections of a cider

trough dismantled more than half a century back. Cushions of

emerald moss studded the thatches, and liliputian forests of

grass-

blades sprang thick between the cobble stones. The place

might

have been mistaken for some deserted grange, but for the

con-

tradiction conveyed in a bright pewter full-bellied

water-can stand-

ing near the well, in a pile of firewood, with

chopper still stuck

in the topmost billet, and in a

tatterdemalion troop of barn-door

fowl lagging meditatively

across the yard.

On a certain day, when summer warmth and unbroken silence

brooded

over all, and the broad sunshine blent the yellows, reds,

and

greys of tile and stone, the greens of grass and foliage, into

one harmonious whole, a visitor entered the open gate. This was

a

tall, large young woman, with a fair, smooth, thirty-year-old

face. Dressed in what was obviously her Sunday best, although it

was neither Sunday nor even market-day, she wore a bonnet

diademed with gas-green lilies of the valley, a netted black

mantilla, and a velvet-trimmed violet silk gown, which she

carefully lifted out of dust’s way, thus displaying a stiffly

starched

petticoat and kid spring-side boots.

Such attire, unbeautiful in itself and incongruous with its sur-

roundings, jarred harshly with the picturesque note of the scene.

From being a subject to perpetuate on canvas, it shrunk, as it

were,

to the background of a cheap photograph, or the stage

adjuncts

to

to the heroine of a farce. The silence too was shattered as the

new

comer’s foot fell upon the stones. An unseen dog began

to mouth a

joyous welcome, and the fowls, lifting their thin,

apprehensive

faces towards her, flopped into a clumsy run as

though their last

hour were visible.

The visitor meanwhile turned familiar steps to a door in the

wall

on the left, and raising the latch, entered the flower garden of

Les Calais. This garden, lying to the south, consisted then, and

perhaps does still, of two square grass-plots with a broad gravel

path running round them and up to the centre of the house.

In marked contrast with the neglect of the farmyard was this

exquisitely kept garden, brilliant and fragrant with flowers.

From

a raised bed in the centre of each plot standard rose-trees

shed out

gorgeous perfume from chalices of every shade of

loveliness, and

thousands of white pinks justled shoulder to

shoulder in narrow

bands cut within the borders of the grass.

Busy over these, his back towards her, was an elderly man,

braces

hanging, in coloured cotton shirt. ” Good afternoon,

Tourtel,”

cried the lady, advancing. Thus addressed, he straight-

ened

himself slowly and turned round. Leaning on his hoe, he

shaded

his eyes with his hand. “Eh den! it’s you, Missis

Pedvinn,” said

he ; ” but we didn’t expec’ you till to-morrow ? ”

” No, it’s true,” said Mrs. Poidevin, ” that I wrote I would

come

Saturday, but Pedvinn expects some friends by the English

boat,

and wants me to receive them. Yet as they may be stay-

ing the

week, I did not like to put poor Cousin Louis off so long

without

a visit, so thought I had better come up to-day.”

Almost unconsciously, her phrases assumed apologetic form.

She had

an uneasy feeling Tourtel’s wife might resent her un-

expected

advent ; although why Mrs. Tourtel should object, or

why she

herself should stand in any awe of the Tourtels, she

could

could not have explained. Tourtel was but gardener, the wife

housekeeper and nurse, to her cousin Louis Renouf, master of Les

Calais. ” I sha’n’t inconvenience Mrs. Tourtel, I hope ? Of

course I shouldn’t think of staying tea if she is busy ; I’ll just

sit

an hour with Cousin Louis, and catch the six’o’clock

omnibus

home from Vauvert.”

Tourtel stood looking at her with wooden countenance, in

which two

small shifting eyes alone gave signs of life. “Eh,

but you won’t

be no inconvenience to de ole woman, ma’am,”

said he suddenly, in

so loud a voice that Mrs. Poidevin jumped ;

” only de

apple-gôche, dat she was goin’ to bake agen your visit,

won’t be

ready, dat’s all.”

He turned, and stared up at the front of the house ; Mrs.

Poidevin,

for no reason at all, did so too. Door and windows

were open

wide. In the upper storey, the white roller-blinds were

let down

against the sun, and on the broad sills of the parlour

windows

were nosegays placed in blue china jars. A white

trellis-work

criss-crossed over the façade, for the support of

climbing, rose

and purple clematis which hung out a curtain of

blossom almost

concealing the masonry behind. The whole

place breathed of peace

and beauty, and Louisa Poidevin was

lapped round with that

pleasant sense of well-being which it

was her chief desire in

life never to lose. Though poor Cousin

Louis —feeble, childish,

solitary— was so much to be pitied, at

least in his comfortable

home and his worthy Tourtels he found

compensation.

An instant after Tourtel had spoken, a woman passed across

the wide

hall. She had on a blue linen skirt, white stockings, and

shoes

of grey list. The strings of a large, bibbed, lilac apron

drew

the folds of a flowered bed-jacket about her ample waist ;

and

her thick yellow-grey hair, worn without a cap, was arranged

smoothly

smoothly on either side of a narrow head. She just glanced out,

and

Mrs. Poidevin was on the point of calling to her, when

Tourtel

fell into a torrent of words about his flowers. He had so

much to

say on the subject of horticulture ; was so anxious for

her to

examine the freesia bulbs lying in the tool-house, just

separated

from the spring plants ; he denounced so fiercely the

grinding

policy of Brehault the middleman, who purchased his

garden stuff

to resell it at Covent Garden —”my good! on dem

freesias I didn’t

make not two doubles a bunch !”— that for a long

quarter of an

hour all memory of her cousin was driven from

Mrs. Poidevin’s

brain. Then a voice said at her elbow, “Mr.

Rennuf is quite ready

to see you, ma’am,” and there stood Tourtel’s

wife, with pale

composed face, square shoulders and hips, and feet

that moved

noiselessly in her list slippers.

“Ah, Mrs. Tourtel, how do you do?” said the visitor; a

question

which in the Islands is no mere formula, but demands

and obtains

a detailed answer, after which the questioner’s own

health is

politely inquired into. Not until this ceremony had

been

scrupulously accomplished, and the two women were on

their way to

the house, did Mrs. Poidevin beg to know how

things were going

with her ” poor cousin.”

There lay something at variance between the ruthless, calculat-

ing

spirit which looked forth from the housekeeper’s cold eye, and

the extreme suavity of her manner of speech.

“Eh, my good ! but much de same, ma’am, in his health,

an’ more

fancies dan ever in his head. First one ting an’

den anudder, an’

always tinking dat everybody is robbin’ him.

You rem-ember de

larse time you was here, an Mister Rennuf

was abed ? Well, den,

after you was gone, if he didn’t deck-

clare you had taken some

of de fedders of his bed away wid

you. Yes, my good ! he tought

you had cut a hole in de

tick

tick, as you sat dere beside him an’ emptied de fedders away

into

your pocket.”

Mrs. Poidevin was much interested. ” Dear me, is it possible ?

….

But it’s quite a mania with him. I remember now, on

that very day

he complained to me Tourtel was wearing his shirts,

and wanted me

to go in with him to Lepage’s to order some new

ones.”

“Eh! but what would Tourtel want wid fine white shirts

like dem ?”

said the wife placidly. “But Mr. Louis have such

dozens an’

dozens of em dat dey gets hidden away in de presses,

an’ he tinks

dem’ stolen.”

They reached the house. The interior is quite as characteristic

of

the Islands as is the outside. Two steps take you down

into the

hall, crossing the further end of which is the staircase

with its

balustrade of carved black oak. Instead of the mean

painted

sticks, known technically as ” raisers,” and connected

together

at the top by a vulgar mahogany hand-rail —a funda-

mental article

of faith with the modern builder— these old

Island balustrades

are formed of wooden panels, fretted out

into scrolls,

representing flower, or leaf, or curious beaked and

winged

creatures, which go curving, creeping, and ramping along

in the

direction of the stairs. In every house you will find the

detail

different, while each resembles all as a whole. For in the

old

days the workman, were he never so humble, recognised the

possession of an individual mind, as well as of two eyes and two

hands, and he translated fearlessly this individuality of his

into

his work. Every house built in those days and existing down

to these, is not only a confession, in some sort, of the tastes,

the

habits, the character, of the man who planned it, but

preserves

a record likewise of every one of the subordinate minds

employed

in the various parts.

Off

Off the hall of Les Calais are two rooms on the left and one on

the

right. The solidity of early seventeenth-century walls is shown

in the embrasure depth (measuring fully three feet) of windows

and

doors. Up to fifty years ago all the windows had leaded

casements,

as had every similar Island dwelling-house. To-day, to

the

artist’s regret, you will hardly find one. The showy taste of

the

Second Empire spread from Paris even to these remote

parts,

and plate-glass, or at least oblong panes, everywhere

replaced the

mediaeval style. In 1854, Louis Renouf, just three

and thirty,

was about to bring his bride, Miss Marie Mauger, home

to the

old house. In her honour it was done up throughout, and

the

diamonded casements were replaced by guillotine windows,

six

panes to each sash.

The best parlour then became a ” drawing-room ” ; its raftered

ceiling was whitewashed, and its great centre-beam of oak in-

famously papered to match the walls. The newly married couple

were not in a position to refurnish in approved Second

Empire

fashion. The gilt and marble, the console tables and

mirrors, the

impossibly curved sofas and chairs, were for the

moment beyond

them ; the wife promised herself to acquire these

later on. But

later on came a brood of sickly children (only one

of whom

reached manhood) ; to the consequent expenses Les Calais

owed

the preservation of its inlaid wardrobes, its four-post

bedsteads

with slender fluted columns, and its Chippendale

parlour chairs, the

backs of which simulate a delicious intricacy

of twisted ribbons.

As a little girl, Louisa Poidevin had often

amused herself studying

these convolutions, and seeking to puzzle

out among the rippling

ribbons some beginning or some end ; but

as she grew up, even

the simplest problem lost interest for her,

and the sight of the old

Chippendale chairs standing along the

walls of the large parlour

scarcely stirred her bovine mind now

to so much as reminiscence.

It

It was the door of this large parlour that the housekeeper

opened as

she announced, ” Here is Mrs. Pedvinn come to see

you, sir,” and

followed the visitor in.

Sitting in a capacious ” berceuse,” stuffed and chintz-covered,

was

the shrunken figure of a more than seventy-year-old man.

He was

wrapped in a worn grey dressing-gown, with a black

velvet

skull-cap, napless at the seams, covering his spiritless hair,

and he looked out upon his narrow world from dim eyes set in

cavernous orbits. In their expression was something of the

questioning timidity of a child, contrasting curiously with the

querulousness of old age, shown in the thin sucked-in lips, now

and again twitched by a movement in unison with the twitching

of

the withered hands spread out upon his knees.

The sunshine, slanting through the low windows, bathed hands

and

knees, lean shanks and slippered feet, in mote-flecked streams

of

gold. It bathed anew rafters and ceiling-beam, as it had done

at

the same hour and season these last three hundred years ; it

played over the worm-eaten furniture, and lent transitory colour

to the faded samplers on the walls, bringing into prominence

one

particular sampler, which depicted in silks Adam and Eve

seated

beneath the fatal tree, and recorded the fact that Marie

Hoched

was seventeen in 1808 and put her “trust in God” ; and

the

same ray kissed the cheek of that very Marie’s son, who at

the

time her girlish fingers pricked the canvas belonged to the

envi-

able myriads of the unthought-of and the unborn.

“Why, how cold you are, Cousin Louis,” said Mrs. Poidevin,

taking

his passive hand between her two warm ones, and feeling

a chill

strike from it through the violet kid gloves ; “and in

spite of

all this sunshine too ! ”

” Ah, I’m not always in the sunshine,” said the old man ;

“not

always, not always in the sunshine.” She was not sure

that

that he recognised her, yet he kept hold of her hand and would

not

let it go.

“No ; you are not always in de sunshine, because de sunshine

is not

always here,” observed Mrs. Tourtel in a reasonable voice,

and

with a side glance for the visitor.

“And I am not always here either,” he murmured, half to him-

self.

He took a firmer hold of his cousin’s hand, and seemed to

gain

courage from the comfortable touch, for his thin voice

changed

from complaint to command. ” You can go, Mrs.

Tourtel,” he said ;

” we don’t require you here. We want to

talk. You can go and set

the tea-things in the next room. My

cousin will stay and drink

tea with me.”

“Why, my cert’nly ! of course Mrs. Pedvinn will stay tea.

P’r’aps

you’d like to put your bonnet off in the bedroom, first,

ma’am ?

”

“No, no,” he interposed testily, “she can lay it off here. No

need

for you to take her upstairs.”

Servant and master exchanged a mute look ; for the moment

his old

eyes were lighted up with the unforeseeing, unveiled triumph

of a

child; then they fell before hers. She turned, leaving the

room

with noiseless tread ; although a large-built, ponderous

woman,

she walked with the softness of a cat.

” Sit down here close beside me,” said Louis Renouf to

his cousin, ”

I’ve something to tell you, something very impor-

tant to tell

you.” He lowered his voice mysteriously, and glanced

with

apprehension at window and door, squeezing tight her hand.

” I m

being robbed, my dear, robbed of everything I possess.”

Mrs. Poidevin, already prepared for such a statement, answered

complacently, ” Oh, it must be your fancy, Cousin Louis.

Mrs.

Tourtel takes too good care of you for that.”

” My dear,” he whispered, “silver, linen, everything is going ;

even

even my fine white shirts from the shelves of the wardrobe.

Yet

everything belongs to poor John, who is in Australia, and

who

never writes to his father now. His last letter is ten years

old

—ten years old, my dear, and I don t need to read it over,

for I

know it by heart.”

Tears of weakness gathered in his eyes, and began to trickle

over on

to his cheek.

“Oh, Cousin John will write soon, I’m sure,” said Mrs.

Poidevin,

with easy optimism; “I shouldn’t wonder if he has

made a fortune,

and is on his way home to you at this moment.”

” Ah, he will never make a fortune, my dear, he was always

too fond

of change. He had excellent capabilities, Louisa, but he

was too

fond of change….. And yet I often sit and pretend

to myself he

has made money, and is as proud to be with his poor

old father as

he used to be when quite a little lad. I plan out

all we should

do, and all he would say, and just how he would

look …. but

that’s only my make-believe ; John will never

make money, never.

But I’d be glad if he would come back to

the old home, though it

were without a penny. For if he don’t

come soon, he’ll find no

home, and no welcome….. I raised

all the money I could when he

went away, and now, as you know,

my dear, the house and land go

to you and Pedvinn….. But

I’d like my poor boy to have the

silver and linen, and his mother’s

furniture and needlework to

remember us by.”

” Yes, cousin, and he will have them some day, but not for a

great

while yet, I hope.”

Louis Renouf shook his head, with the immovable obstinacy of

the

very old or the very young. ”

Louisa, mark my words, he will get nothing, nothing.

Everything is

going. They’ll make away with the chairs and

the tables next,

with the very bed I lie on.”

“Oh,

“Oh, Cousin Louis, you mustn’t think such things,” said

Mrs.

Poidevin serenely ; had not the poor old man accused her

to the

Tourtels of filching his mattress feathers ?

” Ah, you don’t believe me, my dear,” said he, with a resig-

nation

which was pathetic: “but you’ll remember my words

when I am gone.

Six dozen rat-tailed silver forks, with silver

candlesticks, and

tray, and snuffers. Besides odd pieces, and piles

and piles of

linen. Your cousin Marie was a notable housekeeper,

and

everything she bought was of the very best. The large

table-cloths were five guineas apiece, my dear, British money—

five guineas apiece.”

Louisa listened with perfect calmness and scant attention.

Circumstances too comfortable, and a too abundant diet, had

gradually undermined with her all perceptive and reflective

powers. Though, of course, had the household effects been

coming

to her as well as the land, she would have felt more

interest in

them ; but it is only human nature to contemplate the

possible

losses of others with equanimity.

” They must be handsome cloths, cousin,” she said pleasantly ;

” I’m

sure Pedvinn would never allow me half so much for mine.”

At this moment there appeared, framed in the open window,

the

hideous vision of an animated gargoyle, with elf-locks of

flaming

red, and an intense malignancy of expression. With a

finger

dragging down the under eyelid of either eye, so that the

eyeball

seemed to bulge out with a finger pulling back either

corner of

the wide mouth, so that it seemed to touch the ear-this

repulsive

apparition leered at the old man in blood-curdling

fashion. Then

catching sight of Mrs. Poidevin, who sat dum-

founded, and with

her “heart in her mouth,” as she afterwards

expressed it, the

fingers dropped from the face, the features sprang

back into

position, and the gargoyle resolved itself into a buxom

red-haired

red-haired girl, who, bursting into a laugh, impudently stuck her

tongue out at them before skipping away.

The old man had cowered down in his chair with his hands

over his

eyes ; now he looked up. ” I thought it was the old

Judy,” he

said, ” the old Judy she is always telling me about.

But it’s

only Margot.”

” And who is Margot, cousin ? ” inquired Louisa, still shaken

from

the surprise. ”

“She helps in the kitchen. But I don’t like her. She pulls

faces at

me, and jumps out upon me from behind doors. And

when the wind

blows and the windows rattle she tells me about

the old Judy from

Jethou, who is sailing over the sea on a broom-

stick, to come

and beat me to death. Do you know, my dear,”

he said piteously,

“you’ll think I’m very silly, but I’m afraid up

here by myself

all alone ? Do not leave me, Louisa ; stay with

me, or take me

back to town with you. Pedvinn would let me

have a room in your

house, I’m sure ? And you wouldn’t find me

much trouble, and of

course I would bring my own bed linen, you

know.”

” You had best take your tea first, sir,” said Mrs. Tourtel

from

outside the window ; she held scissors in her hand, and

was busy