The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume IX April 1896

Contents

Literature

I. A Birthday Letter . From “The

Yellow Dwarf”. Page 11

II. Hand and Heart .. By Francis

Prevost . . 29

III. Cousin Rosalys

.. Henry Harland . . 35

IV. Wolf-Edith … Nora Hopper

.. 65

V. On the Art of Yvette GuilbertStanley V. Makower . 60

VI. A Ballad of the Heart’s BountyLaurence Alma Tadema . 85

VII. Stories Toto Told Me .Baron

Corvo … 86

VIII. Mary Astell . .

.Mrs. J. E. H. Gordon . 105

IX. Rideo . . . . R. V. Risley

. . . 188

X. The Fishermen (from the French of

Emile Verhaeren)Alma Strettell . . 135

XI. Death’s Devotion . . Frank Athelstane Swet-

tenham . . . 145

XII. Song

of Sorrow . . Charles Catty . . 157

XIII. The Sweet o’ the Year . Ella Hepworth Dixon . 158

XIV. Two

Sonnets from PetrarchRichard Garnett, LL.D.,

C.B. . . . . 167

XV. Poor Romeo! . .

.Max Beerbohm . . 169

XVI. Sunshine . . . Olive Custance . . 187

XVII. A Journey of Little ProfitJohn Buchan . . 189

XVIII. A Guardian of the Poor . T. Baron Russell .

. 205

XIX. A Ballad of Victory . Dollie Radford . . 229

XX. Four Prose Fancies . Richard Le Gallienne .

237

Art

The Yellow Book — Vol. IX. — April, 1896

Art

I. The Missing Boat in Sight. . By Edward S. Harper Page 7

II. The Fishing

House

III. Stanstead AbbotsE. H. New . 23

IV. Study

of Trees . Mary J. Newill 32

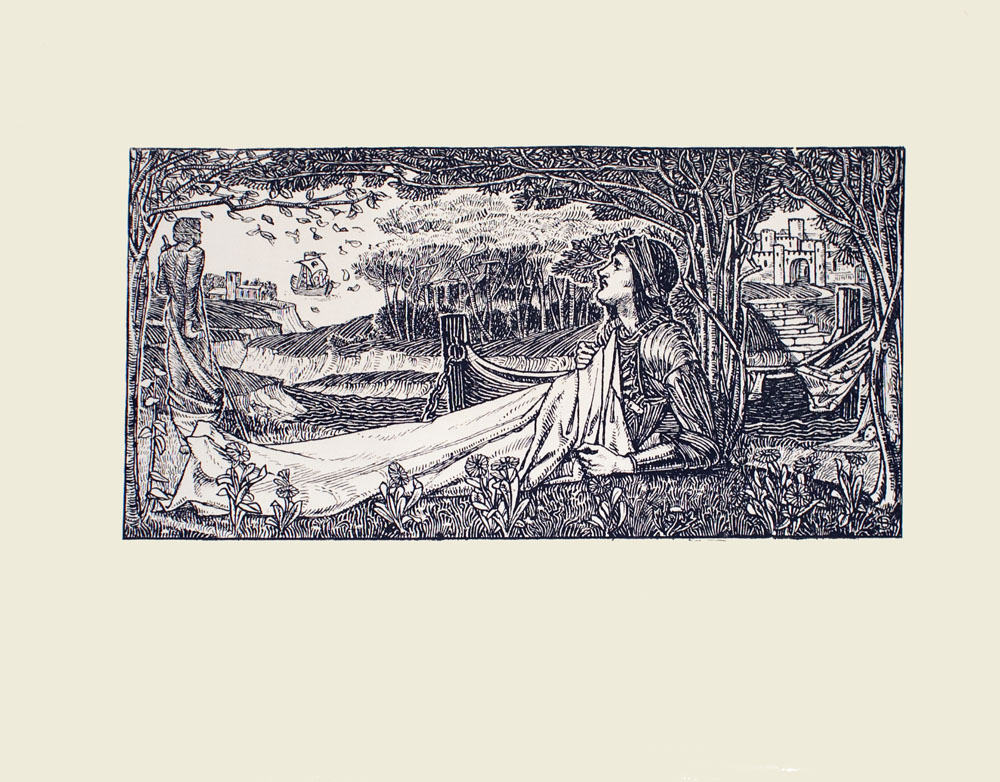

V. The Lady of Shalott . Florence

M. Rudland 54

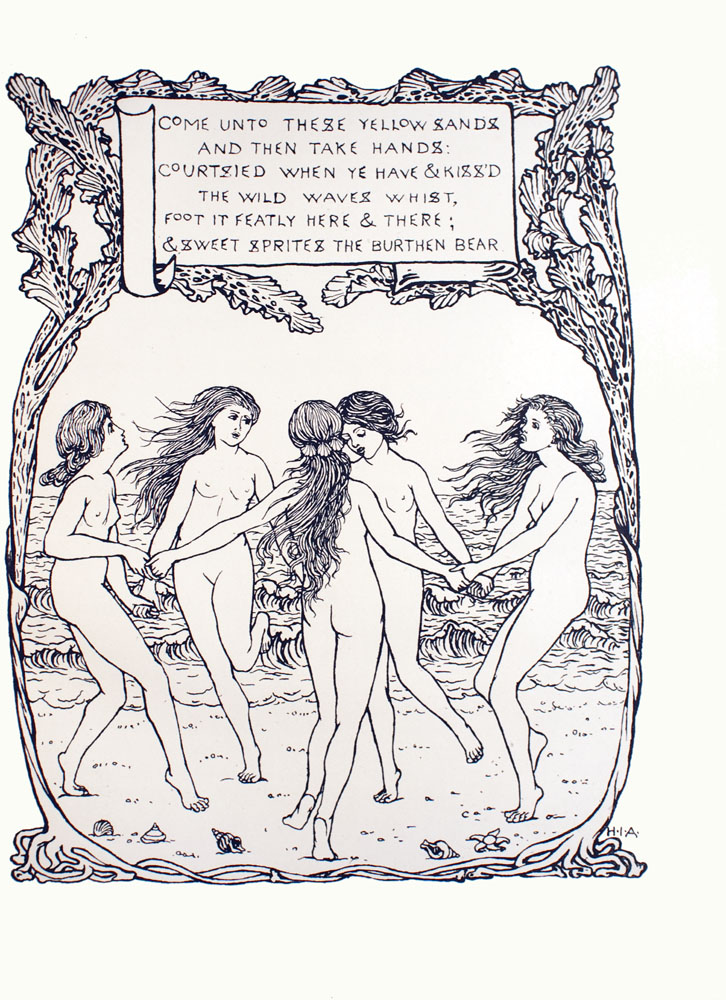

VI. “Come Unto These

Yellow Sands”H. Isabel Adams . 82

VII. A Reading from HerrickCelia A. Levetus . 102

VIII. Night …. J. E. Southall .

132

IX. Hermia and Helena

X. Port Eynon, GowerC. M. Gere . . . 140

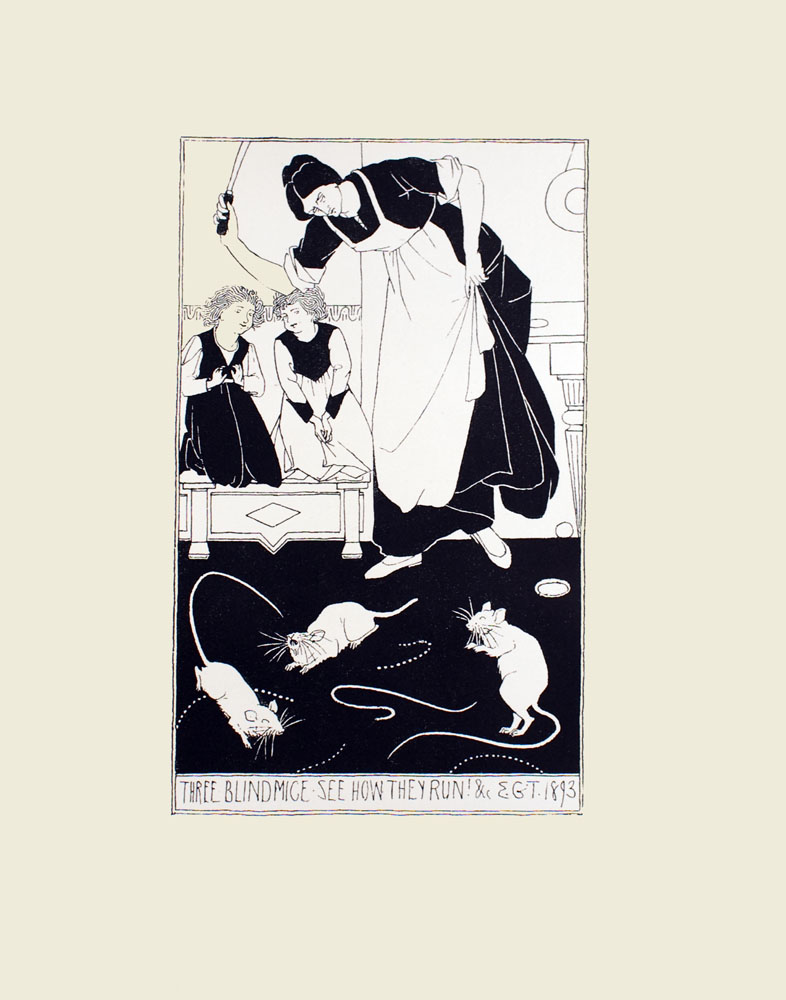

XI. “Three Blind Mice” . E. G. Treglown 153

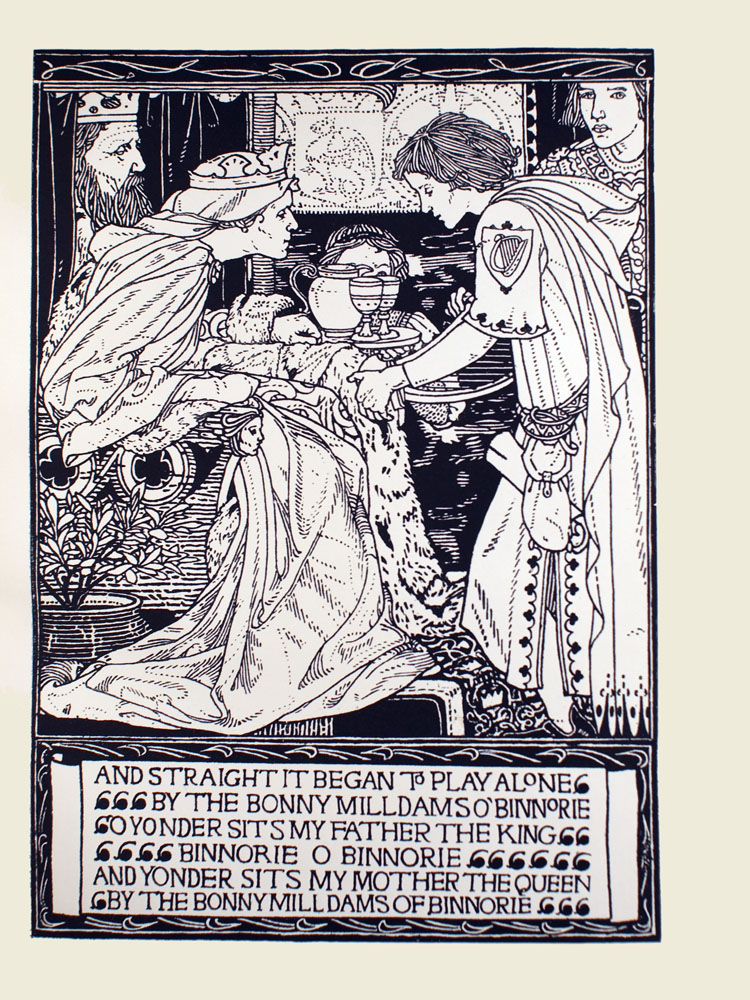

XII. “Binnorie, O Binnorie”Evelyn Holden . 164

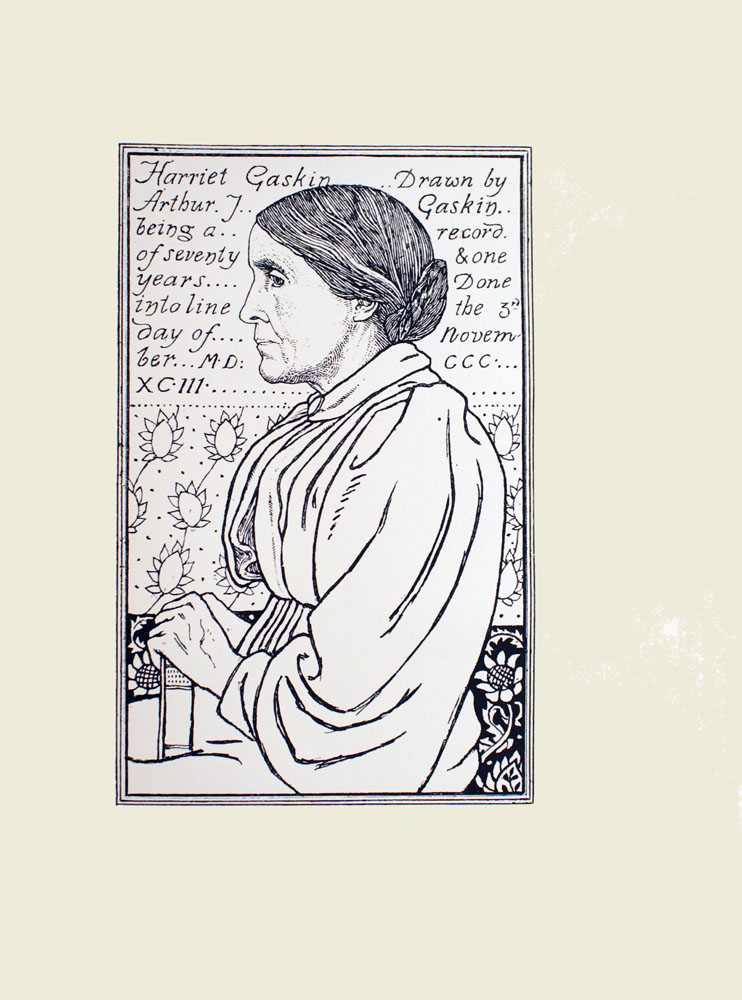

XIII. The Artist’s Mother

XIV. A Book Plate . A. J. Gaskin . . 182

XV. Tristram and

IseultBernard Sleigh 2O2

XVI. Cupid . Sydney Meteyard . 233

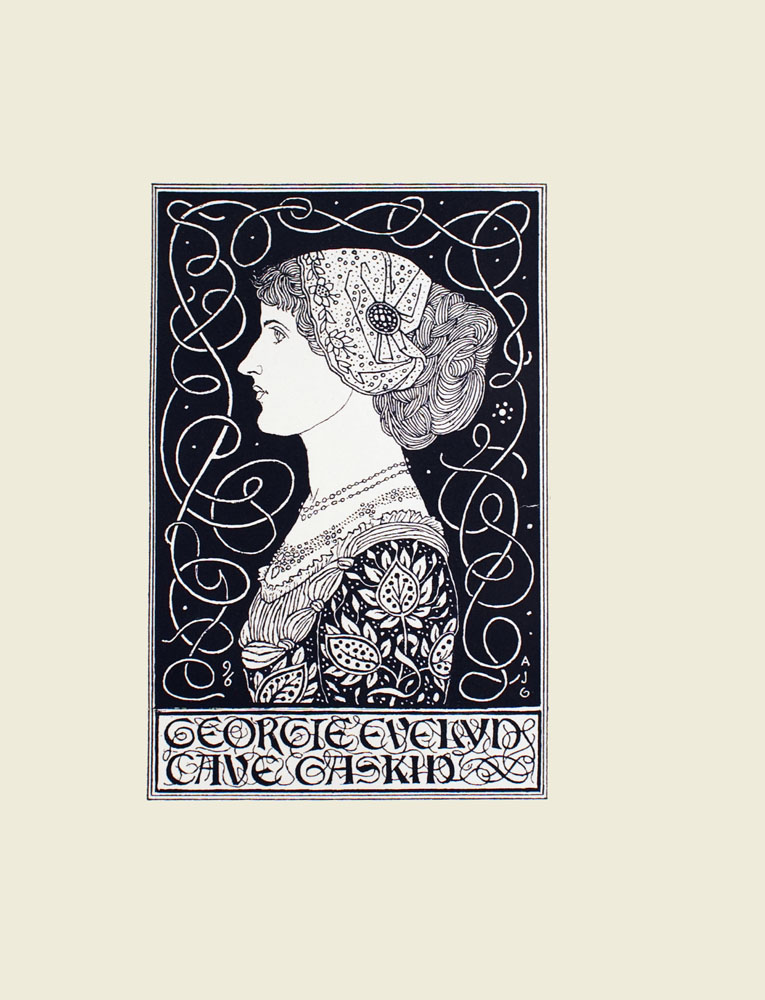

XVII. A Book PlateMrs. A. J. Gaskin . 257

The Title-page and Front Cover are by

Mrs. PERCY DEARMER.

Back Cover, by Patten Wilson

Advertisements

The Pictures in this Volume are by Members

of the BIRMINGHAM SCHOOL.

A Birthday Letter

From “The Yellow Dwarf”

MR. EDITOR :

I was vastly diverted (as no doubt were you) by the numerous

and various

results that followed the appearance of my letter about

books and things in

the October number of your Quarterly.

May we not reckon amongst these, for

instance, the departure

of Mr. Frank Harris for South Africa, and the

reorganisation by

Mr. William W. Astor of the entire staff of the Pall Mall

Gazette? And I love to think it was with

a view to soothing

the hurt I had inflicted upon a whole Tribe of

Pressmen,that a

compassionate Government nominated a representative

Pressman

to the post of Laureate.

I was diverted, too, by the numerous and various guesses that

were hazarded

at my identity. Perhaps it will be kind if I

” make a statement ” upon this

subject. Roundly, then, one and

all the guessers were at fault. I am not

Mr. Max Beerbohm,

nor Professor Saintsbury, nor Mr. Rider Haggard ; still less, if

possible, am

I Mrs. Humphry Ward ; and least of all, sir,

yourself. I’m reluctant to

deprive you of the glory, but I mauna

tell a lee. I can’t deny—I

wish to gracious I could—that you

tampered a little with my proofs,

expunging choice passages,

appending footnotes, and even here and there

inserting a comma

or

or a parenthesis in the text ; that, I suppose, is the Editor’s

consolation.

But beyond that, you had no more to do with the

composition of my letter,

than I myself had to do with the funny

little explosive paragraph in the

Saturday Review, which attri-

buted it to

you. It was sweet, by the bye, to hear the Saturday

Review pathetically complaining of anonymity. Are the ” slatings

“

in its own columns invariably signed ? Do tell me, àpropos of

this,

and if the question be not indiscreet, what is the

secret of

the Saturday Review’s perennial

state of peevish animosity towards

yourself? Is it possible that in the

course of your editorial duties

you have ever had occasion to reject a

manuscript offered by a

member of its staff?

If, as a matter of fact, the elevation of Mr. Alfred Austin

to the

Laureateship was determined by words of mine, I can-

not but rejoice. All

things considered, a more appropriate

selection could scarcely have been

made. Equally to ” Press

and Public,” in this age of the Pressman’s

ascendency, a Press-

man Laureate should be a gratifying spectacle. For me,

the

choice always lay between Mr. Alfred Austin and Sir Edwin

Arnold— on the one hand the Bourgeois Gentilhomme, on the

other hand

the Tartufe, of the kind of scribbling that now-

adays has come to take the

place of Literature. Talk of

Mr. Swinburne, of Mr.

Morris, of Mr. Meredith, of Mr.

Watson, always seemed to me beside the mark

; these gentle-

men are Poets ; what have they in common with ” Press

and

Public” ? And how precipitantly and perfectly did Mr. Austin

prove

his mettle, vindicate his qualifications for ” the job.” I

allude, of

course, to that singularly pure example of journalese,

Jameson’s Ride. Most people, to be sure, write it

(and some

even pronounce it) Raid—Jameson’s Raid. But Mr. Austin

knows

knows his readers (which is more than I do), and boldly

and obligingly he

spells it Ride; thus incidentally ranging

himself with the advocates of Orthographical Reform. I was

disappointed to

observe that a subsequent performance of the

Pressman Laureate’s was a

celebration of the virtues of Alfred

the Great.

Why this backsliding ? Why not Alfred the

Grite

?

And now, sir, can you, can any sane Christian man, can Mr.

George du Maurier

himself, explain the success of Trilby ? That

the book should have had a certain measure of success, nay, a

considerable

measure of success, were, indeed, explicable enough.

It is the production

of a gentleman who for years and years has

charmed and amused us by his

drawings. Curiosity to see what

he could turn out in the way of a novel

illustrated by himself,

might account for an edition or two. (Imagine a

volume of

black-and-white sketches published to-morrow from the pencil

of

Mr. Edmund Gosse, with legends in prose and

verse by the

artist. I, for one, should not sleep till I possessed it.)

And

then the book itself is an amiable, sugar-and-watery sort of book

enough, and that ought to account for a few more editions. But

the furious,

but the uncontrollable, but the unprecedented success

of Trilby—explain me that.

One has always known that to command an immediate success

in

English-speaking lands (their inhabitants, as Mr. Carlyle

vigorously put

it, being mostly—what they are), a novel must

either discuss a ”

problem,” or attain a certain standard of silliness,

vulgarity, and

slipshod writing, or haply do both : and if there are

exceptions to this

rule, they only prove it. Well, one can hardly

accuse Trilby of discussing a ” problem.” And as for silliness,

vulgarity, and slipshod writing—honestly, does Trilby, in point of

these qualities, surpass just the usual

slipshod, vulgar, and silly

English

English novel, which perchance sells it five or ten thousand

copies, and

mercifully stops at that ?

Oh, Trilby is slipshod, vulgar, and silly enough, in

all conscience.

The question I propound is exclusively a question of excess.

Trilby is slipshod, vulgar, and silly ; and Trilby is exquisitely

tiresome and irritating,

into the bargain. I have read it. Yes,

though loth to appear boastful, yet

with a natural pride in my

perseverance, I may pledge you my word that I

have read it.

Laboriously, patiently, doggedly, I have plodded through its

four

hundred and forty-seven mortal pages—four hundred and

forty-

seven ! I have learned in suffering what I am fain to teach. It

is true, from his title-page, the humane and complimentary

author warned me

of what I must expect :

” Aux nouvelles que j’apporte

Vos beaux yeux vont pleurer.”

But I was foolhardy, and pressed on. My “beaux yeux” did

indeed weep much

and often, for sheer weariness, for sheer

exasperation, for sheer disgust

sometimes, before I had reached the

last of his ” nouvelles.” The very

first of them was rather a

staggerer. Fancy a fellow-man, at this hour of

the afternoon, as

the very first of his “nouvelles,” informing you that

“goods

trains in France are called la Petite

Vitesse.” But if we once

begin to cry “Fancy” over Trilby, we shall never have done.

The book fairly

bristles with solecisms and ineptitudes. Fancy

any gent but a commercial

gent blithely writing of ” Botticelli,

Mantegna, and Co.” Fancy any scholar

but a board-school

scholar writing, “Not but what little Billee had his

faults.”

Fancy any author but an author of the rank of Mr. Jerome

Jerome writing, “It was the fashion to do so”—that is, to wear

long

side-whiskers—”it was the fashion to do so, then, for such of

our

our gilded youth as could afford the time (and the hair).” And

fancy

this—on page 13, ominous number—this dark, mysterious

intimation that the exciting parts are coming : ” He never forgot

that

Impromptu, which he was destined to hear again one day in

strange

circumstances.”

Yes, Trilby is slipshod enough, vulgar enough, silly

enough, in

all conscience. But upon my soul, I cannot see that it is

more

slipshod, or vulgarer, or sillier, than the common run of con-

temporary English novels. Indeed, on the whole, I should say it

was, if

anything, a shade less silly, a shade less vulgar and slipshod,

than the

novels of Miss Marie Corelli, for example, or those of

” Rita.” Why, then,

should it excel them as it does in

popularity ?

I think Trilby’s advantage is an advantage of kind,

rather than

of degree. I think the silliness of Trilby is a more insidious kind

of silliness, its vulgarity a

more insidious kind of vulgarity, its

slipshod writing a more insidious

kind of slipshod writing, than

the feeble-minded multitude have been baited

with before, in a

novel. The writing, for instance, if you will study it,

resembles

no other form of human writing quite so much as that

jauntily

familiar, confidential, colloquial form of writing which all

lovers

of advertisements know and appreciate in the circulars of Mother

Seigel’s Syrup. Nay, do you rub your eyes ?

Listen to this

excerpt :

” It is a wondrous thing, the human foot—like the human hand ;

even

more so, perhaps ; but, unlike the hand, with which we are so

familiar, it

is seldom a thing of beauty in civilised adults who go about

in leather

boots and shoes.

” So that it is hidden away in disgrace, a thing to be thrust out of

sight

and forgotten. It can sometimes be very ugly indeed—the

ugliest

thing there is, even in the fairest and highest and most gifted

of

of her sex ; and then it is of an ugliness to chill and kill romance, and

scatter love s young dream, and almost break the heart.

“And all for the

sake of a high heel and a ridiculously pointed toe

—mean things, at

the best !

” Conversely, when Mother Seigel——”

Ah, no—I beg your pardon—it is ” Mother Nature.” But

doesn t

one instinctively expect “Mother Seigel ” ? And wouldn’t

the effect have

been better if one had found ” Mother Seigel”? And

hadn’t the author of

Trilby a sound commercial inspiration when

he

selected the style of Mother Seigel’s circulars as the model on

which to form his own ? No doubt the selection was unconscious;

but there

it stands ; and I cannot but believe it has had much to

do with the book’s

success. When we remember that the over

whelming majority of people who

read, in these degenerate days,

belong to the class of society one doesn t

know, that they are

destitute of literary traditions, that they have

received what they

fondly misname their ” education ” at the expense of the

parish

and that they come to Trilby hot from the

works of Mr. All Kine,

surely we need not marvel that the Mother Seigel

style of

writing is the style of writing that “mostly takes their

hearts.”

The peculiarly insidious kind of silliness which, hand in hand

with its

sister graces, a peculiarly insidious kind of vulgarity, and

a peculiarly

insidious kind of slipshod writing, is presumably a

super-inducing cause of

Trilby’s popularity, one would have diffi-

culty in characterising by a single word. One feels it everywhere;

everywhere, everywhere, from first line to last ; but the appropriate

epithet eludes one. Is it a sentimental silliness ? A fatuously

genial

silliness ? A priggish silliness ? A pruriently prudish silli-

ness ? Yes,

yes ; it is all this ; but it is something else. The

essential flavour of

it is in something else. If you will permit

me to use the word, sir, I

would suggest that the crowning

quality

quality of the silliness of Trilby is WEGOTISM. I mean

that the

author s constant attitude towards his reader is an attitude

of

Me-and-Youness. “Me and you—we see these things thus ; we

feel thus, think thus, speak thus ; and thereby we approve our

selves a

couple of devilish superior persons, don’t you know ?

Common, ordinary,

unenlightened persons wouldn’t understand

us. But we understand each

other.” That is the tone of Trilby

from first

line to last. The author takes his reader by the arm,

and flatters his

self-conceit with a continuous flow of cheery,

unctuous, cooing Wegotism.

Conceive the joy of your average

plebeian American or Briton, your

photographer, your dentist,

thus to be singled out and hob-a-nobbed with by

a ” real gentle-

man ” ; made a companion of the recipient of his

softly-mur-

mured reminiscences and reflections, all of them trite and

obvious,

and couched in a language it is perfectly easy to understand.

” Botticelli, Mantegna, and Co.” ! Why, that phrase alone,

occurring on

page 2, would make your shop-walker’s lady feel at

home from the

commencement.

I have mentioned the priggishness of Trilby. Were

there ever

three such insufferable prigs as Taffy, the Laird, and little

Billee

?—No, no ; I don’t mean three ; two, two ; for Taffy and

the

Laird are one and indistinguishable.—Were there ever two

such

insufferable prigs as Taffy-the-Laird and Little Billee ? And

isn’t

their priggishness all the more offensive because they are

vainly

posing the whole time for devil-may-care, rollicking good fellows

?

I personally know nothing about the Latin Quarter ; but you,

sir,

are regarded as its exegetist. May I ask you for a little

information ? In

your day, in the Latin Quarter, wouldn’t the

students amongst whom they

dwelled have risen in a mass and

“done something” to Taffy-the-Laird and

little Billee? I

have heard grisly stories. I have heard that students in

the

Latin

Latin Quarter, especially students of Art, are sometimes not

without a

certain strain of unrefinement in their natures. I

have heard that they

devoutly hate a prig. I have heard that,

though you may be as virtuous and proper as ever you like in the

Latin

Quarter, you were exceedingly well-advised not to seem

so ; that if you would ” do good,” you must indeed do it ”

by

stealth,” and not blush merely, but suffer corporal penalties, if

you

” find it fame.” I have heard of prigs being seized at midnight

by

mobs armed with cudgels ; of their clothing being torn from

their backs,

and their persons embellished with symbolic pictures

and allusive texts, in

paint judiciously mixed with siccatif, so that

it dried in before soap and water were obtainable. Tell us, sir,

why didn t

“something happen” to Taffy-the-Laird and little

Billee ?

Though I may seem to address you in a gladsome spirit,

believe me, it is

with pain that I have brought myself to write

unkind things of Trilby. Its author is a highly distinguished

gentleman, whose work in his own department of art, everybody

with an eye

for good drawing, and a sense of humour, should be

thankful for. But the

fact of the matter is that the art of writing

must be learned ; must be as thoroughly and as industriously

studied

and practised and considered as any other art. They

understand this in

France ; but in England people imagine that

any fool can write a

novel—” it’s as easy as lying.” That is why

English novels, for

downright absolute worthlessness, take the

palm amongst the novels of the

world. It is no shame to a

highly distinguished draughtsman that, trying

his hand in the

art of fiction, he should have achieved a grotesque

artistic failure.

You or I would probably achieve a grotesque artistic

failure, if

we should try our hands at a cartoon for Punch. The shame is

to the public, which has hailed an artistic

failure as an artistic

triumph.

Sometimes, for brief intervals, one forgets how elemen-

tally imbecile our

Anglo-Saxon Public is ; and then things like

the success of Trilby come to make us remember it, and put on

mourning.

And now, hence loathed melancholy, and let me turn to the

more inspiriting

business of congratulating the YELLOW BOOK

upon the completion of the

second year of its existence, and the

beginning of the third. I have

followed your adventurous career,

sir, from the first, with sympathy, with

curiosity, with amusement.

You have made a sturdy fight against tremendous

odds. From the

appearance of your initial number until quite recently, you

have

had all the newspapers of England, with half-a-dozen whimsical

exceptions, all the dear old fusty, musty newspapers of England

arrayed

against you, striving in their dear old wheezy, cumbrous

way, to crush you,

treating you indeed (please don’t run your pen

through this) as the book-émissaire of modern publications. You

have

survived ; and many of your erstwhile enemies have become

your lukewarm

friends. (I wish you joy of ’em ; I’m not sure you

weren’t better off

without ’em.) That is surely a merry record.

It was always droll, the hysterical anger the YELLOW BOOK

provoked in those

village scolds, the newspapers. I remember

reading with peculiar glee an

article which used to be inserted

periodically in the columns of the Pall Mall Gazette, before its

reformation, in

which you were compared at once to the Desert

of Sahara and the Family Herald ; my eye, what a combination !

The

real truth is that in spite of many faults (I’ll speak of them

again in a

minute), in spite of many faults, the YELLOW BOOK

has been from the

commencement a very lively and entertaining

sort of YELLOW BOOK indeed ; in

literary and artistic interest, and

in mechanical excellence, far and far

and far-away superior to any

The Yellow Book—Vol. IX. B

other

other serial in England—though that, to be sure, you may object,

isn’t saying much. Consider, for an instant, your first number

alone : the

printing of it, the paper, the binding, the shape of its

page, the

proportion of text and margin ; the absence of advertise-

ments, so that we

could approach its contents without being

preoccupied by a consciousness of

the merits of Eno’s Fruit Salt

and Beecham’s Pills ; and the pictures, and

the care with which

they were reproduced, and then—and then the

Literature ! There

was Mr. Henry James, a great

artist at his best, in The Death of

the Lion ;

there was Mr. Max Beerbohm, with his delicious, his

immortal Defence of Cosmetics, that unique masterpiece of

affec-

tation, preciosity, and subtle fooling ; there were Mr. Hubert

Crackanthorpe and Mr. Edmund Gosse, Professor

Saintsbury and

Mr. Richard Le Gallienne, Mr. William Watson and Dr.

Garnett, Mr. George Moore and Mr. John Davidson ; and there

was Miss Ella D’Arcy, with her Irremediable, a short story which

has since made a long

reputation. Wasn’t it a jolly company ? I

shall

be grateful if any one will tell me of a single number of any

other

periodical one quarter so fresh, so varied, so diverting. I

protest it was

a thing that England ought to have been proud of.

And yet, what happened ?

Oh, nothing which, taking one

consideration with another, you might not

have expected. All

the newspapers of England, with two or three

cool-headed

exceptions, went into paroxysms of frenetic rage. The foolish

old

things pulled horrid faces, called naughty names, hissed,

spluttered,

shook their fists, and in short, did all that could be done, by

mere

mouthings and gesticulations, to frighten the tender infant to

death in its cradle. The noise was deafening, the spectacle far

from

pretty, but the infant seemed to like it. He smiled, and

crowed, and

flourished, and—may live to be hanged yet.

Why were the newspapers so vexed, you wonder ? Partly, I

surmise,

surmise, because, like the wicked fairies in the fairy-tales, they hadn’t

been invited to the christening ; partly because you, sir, had perhaps

declined offers of ” copy ” from some of their enterprising young

men ; but

chiefly, chiefly, because the YELLOW BOOK, was new,

and daring, and

delightful, and seemed likely to please the intelli-

gent remnant of the

public, and to become a power in the land.

The old story of envy, hatred,

malice, and all uncharitableness.

” For was there ever anything projected

that savoured of newness

or renewing, but the same endured many a storm of

gainsaying or

opposition.” Fortunately, however, there was neither murder

nor

sudden death. The YELLOW BOOK smiled and flourished, and

from

season to season has continued to smile and flourish—till now,

here

am I, giving it a Reader’s benediction on its third birthday.

At the same time, however, I must beg leave to accompany my

benediction by a

few words of wholesome counsel. Brilliant as

your first number was,

brilliant as on the whole all your numbers

have been, each and every one of

them, if the truth must be told,

has contained more than a delicate

modicum—yea, even an

unconscionable deal—of rubbish. Why do

you do it, sir ? As

a concession to the public taste ? Bother the public

taste !

Because better stuff you can’t procure ? You could hardly

procure worse stuff than some of the stuff I have in mind.

I won’t specify

; ‘twould be invidious to do so, and labour

lost besides, for I know your

habits of mangling people’s proofs.

But examine your own conscience and

your tables of contents

—vous verrez!

Against certain evil editorial courses, sir, do

let me warn you. Don’t

publish rubbish because it is signed

by “a name ;” and don’t do so, either,

because it is written by a

friend, or a friend’s friend, or a friend’s

young lady, or a friend’s maiden aunt. Don’t in a word permit yourself to be

“got at.”

Cultivate your discoveries. Cultivate that admirable Baron

Corvo,

whose

whose contributions to your seventh volume no pressman noticed

and no reader

skipped ; those exquisitely humorous renderings

of an Italian peasant’s

saint-lore, which read almost as if

they had been taken down verbatim from

an Italian peasant’s

lips. Cultivate Mrs. (or Miss?) Mary Howarth, whose Nor-

wegian story The

Deacon many of us thought the most

notable thing in your Volume

VIII. Cultivate Mr. Stanley

Makower ; and the ”

C.S.” and the ” O.” whom you have

cultivated too little of

late—cultivate them. Cultivate Mr.

Marriott Watson (despite his tendency to stand on

tip-toe

and grope for rare words in the upper ether) ; cultivate Mr. Kenneth

Grahame ; and if I do not say cultivate Mr. Henry Harland, it’s

because I rejoice to see that

you’ve never shown the faintest

disposition to neglect him. And drop,

drop—ah, how I should

like to tell you whom to drop ; but you

wouldn’t print it.

One word more, and I’ll have done. Don’t make your volumes

too thick. Your

last ran to upwards of four hundred pages ; it’s

too much ; it discourages

people ; stop at three hundred, or at two

hundred and fifty. And, if you

want to be really kind, reduce

your price. Five shillings a quarter for

mere Literature is more

than flesh and blood can bear. Reduce your price to

three-and

sixpence or half-a-crown. Five shillings ? Lord-a-mercy, sir,

do

you think we are made of money ?

Your obedient servant,

THE YELLOW DWARF.

P. S.—And—abolish your ” Art Department.” What on

earth can

any one want with pictures in a Literary Magazine ?

Believe me, they only

interrupt. It ain’t the place for them.

They don’t hang sonnets and stories

between the paintings at the

Royal Academy.

Hand and Heart

By Francis Prevost

CLEAN heart—clean hands,” he said, and looked at mine,

And caught them ‘ere unclasped ; for one was red

That had besprinkled his white lips with wine :

” Clean heart—clean hands,” he said.

(What meant it ? He had whispered, on my breast,

Love’s converts should therewith be christened :

And so my hand was soiled at his request.

” Heart’s passover ! ” he’d said).

And then he drew the fingers pale apart,

And with a kiss the cold, stained palm outspread,

And pressed it thus, down o’er his strenuous heart :

” So hand and heart,” he said.

When, through my thoughts, storm-fire in summer’s night,

Flashed the dolt’s aimless face I had loathed and wed :

He kissed my fingers still, wine-stained and white ;

” Sweet hands, sweetheart,” he said.

“Sour

” Sour both ! ” I gasped, and shook myself away ;

Required my mare : he fetched her, proudly staid ;

Tightened the girths, and closed the curb-chain’s play :

” So hearts,” sadly he said.

And, stooping, set me deftly in my seat,

Pulled straight my skirt, and to the stirrup led

My spurred foot, kissed it, ranged the reins, and, sweet,

” Light hand—light heart,” he said.

The soft, brown glove brushed o’er his sun-brown veins;

He breathed as though it burnt him ; there, instead

Of its doe-skin, seemed still the wine’s wet stains :

” Hands are but hands,” he said.

I pricked her ; felt the bridle draw my hand ;

Bent down an icy face and burning head,

And passed. Yet so, his eyes pierced mine to brand

The ” Heart of hearts,” he said.

* * * *

The yellow, green-girt road rushed by and roared

Beneath, beside us. Like a silver shred

O’er briar and bank the thin moon swept and soared :

” Hands have high ways,” he’d said.

I leant back, straight and stiff, against the reins,

Yet pressed her when she slackened ; half afraid

To hear my heart beat ; till the grass-grooved lanes—

(“Hearts have by-ways,” he’d said),

Dulled

Dulled the hoof-hammers : up the beech-bowered chase,

My face against her glossy neck I laid,

And, with the palm he had kissed, sped fast her pace :

“Hands hold their fires,” he’d said.

Her hot breath jetted through my ruffled hair,

The loose mane on my cheek beat out her tread,

And so we cleared the park ditch. (“Would I dare

To risk my heart ? ” he’d said.)

And, thence, walked slowly o’er the withered brake,

While still his questioning face before me fled,

And where he had leaned his head my arm would ache :

“Hearts ache and break,” he had said.

The Grange gleamed out ; within its hall I found,

Scattered and torn, my letters lying—read !

My lord sat in the card-room, muffled round ;

” I’ve taken cold,” he said.

Cousin Rosalys

ISN’T it a pretty name, Rosalys? But, for me, it is so much

more ; it is a

sort of romantic symbol. I look at it written

there on the page, and the

sentiment of things changes ; it is as

if I were listening to distant music

; it is as if the white paper

turned softly pink, and breathed a

perfume—never so faint a per-

fume of hyacinths. Rosalys, Cousin

Rosalys….. London

and this sad-coloured February morning become shadowy,

remote.

I think of another world, another era. Somebody has said that

” old memories and fond regrets are the day-dreams of the disap-

pointed,

the illusions of the age of disillusion.” Well, if they are

illusions,

thank goodness they are where experience can’t touch

them—on the

safe side of time.

* * *

Cousin Rosalys—I call her cousin. But, as we often used to

remind

ourselves, with a kind of esoteric satisfaction, we were not

“real”

cousins. She was the niece of my Aunt Elizabeth, and

lived with her in Rome

; but my Aunt Elizabeth was not my

” real ” aunt—only my great-aunt

by marriage, the widow of my

father’s uncle. It was Aunt Elizabeth herself,

however, who

dubbed us cousins, when she introduced us to each other ; and

at

that

that epoch, for both of us, Aunt Elizabeth’s lightest words were

in the

nature of decrees, she was such a terrible old lady.

I’m sure I don’t know why she was terrible, I don’t know how

she contrived

it ; she never said anything, never did anything,

especially terrifying ;

she wasn’t especially wise or especially witty

—intellectually,

indeed, I suspect she might have passed for a

paragon of respectable

commonplaceness : but I do know that

everybody stood in awe of her. I

suppose it must simply have

been her atmosphere, her odylic force ; a sort

of metaphysical chill

that enveloped her, and was felt by all who

approached her—

“some people are like

that.” Everybody stood in awe of her,

everybody deferred to her :

relations, friends, even her Director,

and the cloud of priests that

pervaded her establishment and gave

it its character. For, like so many

other old ladies who lived in

Rome in those days, my Aunt Elizabeth was

nothing if not

Catholic, if not Ecclesiastical. You would have guessed as

much,

I think, from her exterior. She looked

Catholic, she looked Eccle-

siastical. There was

something Gothic in her anatomy, in the

architecture of her face : in her

high-bridged nose, in the pointed

arch her hair made as it parted above her

forehead, in her promi-

nent cheek-bones, her straight-lipped mouth and

long attenuated

chin, in the angularities of her figure. No doubt the

simile must

appear far-sought, but upon my word her face used to remind

me

of a chapel—a chapel built of marble, fallen somewhat into

decay.

I’m not sure whether she was a tall woman, or whether she only

had a false air of tallness, being excessively thin and holding her-

self

rigidly erect. She always dressed in black, in hard black silk

cut to the

severest patterns. Somehow, the very jewels she wore

—not merely the

cross on her bosom, but the rings on her fingers,

the watch-chain round her

neck, her watch itself, her old-fashioned,

gold-faced watch—seemed

of a mode canonical.

She

She was nothing if not Catholic, if not Ecclesiastical ; but I

don’t in the

least mean that she was particularly devout. She

observed all requisite

forms, of course: went, as occasion demanded,

to mass, to vespers, to

confession ; but religious fervour was the

last thing she suggested, the

last thing she affected. I never

heard her talk of Faith or Salvation, of

Sin or Grace, nor indeed

of any matters spiritual. She was quite frankly a

woman of the

world, and it was the Church as a worldly institution, the

Church

corporal, the Papacy, Papal politics, that absorbed her

interests.

The loss of the Temporal Power was the wrong that filled

the

universe for her, its restoration the cause for which she lived.

That it was a forlorn cause she would never for an instant even

hypothetically admit. ” Remember Avignon, remember the

Seventy Years,” she

used to say, with a nod that seemed to attri-

bute apodictic value to the

injunction.

“Mark my words, she’ll live to be Pope yet,” a ribald young

man murmured

behind her chair. ” Oh, you tell me she is a

woman. I’ll assume it for the

sake of the argument—I’d do any-

thing for the sake of an argument.

But remember Joan, remember

Pope Joan.! ” And he mimicked his Aunt

Elizabeth’s inflection

and her conclusive nod.

* * *

I had not been in Rome since that universe-filling wrong was

perpetrated—not since I was a child of six or seven—when, a

youth approaching twenty, I went there in the autumn of 1879 ;

and I

recollected Aunt Elizabeth only vaguely, as a lady with a

face like a

chapel, in whose presence—I had almost written in

whose

precincts—it had required some courage to breathe. But

my mother’s

last words, when I left her in Paris, had been, “Now

mind you call on your

Aunt Elizabeth at once. You mustn’t

let

let a day pass. I am writing to her to tell her that you are

coming. She

will expect you to call at once.” So, on the

morrow of my arrival, I made an

exceedingly careful toilet (I

remember to this day the pains I bestowed

upon my tie, the

revisions to which I submitted it !), and, with an anxious

heart,

presented myself at the huge brown Roman palace, a portion of

which my formidable relative inhabited : a palace with grated

windows,

and a vaulted, crypt-like porte-cochère, and a tremendous

Swiss concierge,

in knee-breeches and a cocked hat : the Palazzo

Zacchinelli.

The Swiss, flourishing his staff of office, marshalled me (I can’t

use a

less imposing word for the ceremony) slowly, solemnly,

across a courtyard,

and up a great stone staircase, at the top of

which he handed me on to a

functionary in black—a functionary

with an ominously austere

countenance, like an usher to the

Inquisition. Poor old Archimede ! Later,

when I had come to

know him well and tip him, I found he was the mildest

creature,

the amiablest, the most obliging, and that tenebrious mien of his

only a congenital accident, like a lisp or a club-foot. But for the

present he dismayed me, and I surrendered myself with humility

and

meekness to his guardianship. He conducted me through a

series of vast

chambers—you know those enormous, ungenial

Roman rooms, their sombre

tapestried walls, their formal furniture,

their cheerless, perpetual

twilight—and out upon a terrace.

The terrace lay in full sunshine. There was a garden below it,

a garden with

orange-trees, and rose-bushes, and camellias, with

stretches of green

sward, with shrubberies, with a great fountain

plashing in the midst of it,

and broken, moss-grown statues : a

Roman garden, from which a hundred sweet

airs came up, in the

gentle Roman weather. The balustrade of the terrace

was set at

intervals with flowering plants, in big urn-shaped vases ; I

don’t

remember

remember what the flowers were, but they were pink, and many

of their petals

had fallen, and lay scattered on the grey terrace

pavement. At the far end,

under an awning brave with red and

yellow stripes, two ladies were

seated—a lady in black, presumably

the object of my pious pilgrimage

; and a lady in white, whom,

even from a distance, I discovered to be young

and pretty. A

little round table stood between them, with a carafe of water

and

some tumblers glistening crisply on it. The lady in black was

fanning herself with a black lace fan. The lady in white held a

book in her

hand, from which I think she had been reading aloud.

A tiny imp of a red

Pomeranian dog had started forward, and was

barking furiously.

This scene must have made a deeper impression upon my

perceptions than any

that I was conscious of at the moment,

because it has always remained as

fresh in my memory as you see

it now. It has always been a picture that I

could turn to when I

would, and find unfaded : the garden, the blue sky,

the warm

September sunshine, the long terrace, and the two ladies seated

at

the end of it, looking towards me, an elderly lady in black, and a

young lady in white, with dark hair.

My aunt quieted Sandro (that was the dog’s name), and giving

me her hand,

said ” How do you do ? ” rather drily. And then,

for what seemed a terribly

long time, though no doubt it was only a

few seconds, she kept me standing

before her, while she scruti-

nised me through a double eye-glass, which

she held by a

mother-of-pearl handle ; and I was acutely aware of the

awkward

figure I must be cutting to the vision of that strange young

lady.

At last, ” I should never have recognised you. As a child you

were the image

of your father. Now you resemble your mother,”

Aunt Elizabeth declared ;

and lowering her glass, she added, ” this is your cousin Rosalys.”

I wondered,

I wondered, as I made my bow, why I had never heard before

that I had such a

pretty cousin, with such a pretty name. She

smiled on me very kindly, and I

noticed how bright her eyes

were, and how white and delicate her face. The

little blue veins

showed through the skin, and there was no more than just

the

palest, palest thought of colour in her cheeks. But her

lips—

exquisitely curved, sensitive lips—were warm red. She

smiled on

me very kindly, and I daresay my heart responded with an

instant

palpitation. She was a girl, and she was pretty ; and her name

was Rosalys ; and we were cousins ; and I was eighteen. And

above us

glowed the blue sky of Italy, and round us the golden

sunshine ; and there,

beside the terrace, lay the beautiful old

Roman garden, the fragrant,

romantic garden….. If at

eighteen one isn’t susceptible and sentimental

and impetuous, and

prepared to respond with an instant sweet commotion to

the smiles

of one’s pretty cousins (especially when they’re named Rosalys),

I

protest one is unworthy of one’s youth. One might as well be

thirty-five, and a literary hack in London.

After that introduction, however, my aunt immediately re-

claimed my

attention. She proceeded to ask me all sorts of

questions, about myself,

about my people, uninteresting questions,

disconcerting questions, which

she posed with the air of one who

knew the answers beforehand, and was only

asking as an examiner

asks, to test you. And all the while, the expression

of her face, of

her deprecating, straight-lipped mouth, of her half-closed

sceptical

old eyes, seemed to imply that she already had her opinion of

me,

and that it wouldn t in the least be affected by anything I

could

say for myself, and that it was distinctly not a flattering

opinion.

” Well, and what brings you to Rome?” That was one of

her questions. I felt

like a suspicious character haled before the

local

local magistrate to give an account of his presence in the parish ;

putting

on the best face I could, I pleaded superior orders. I had

taken my baccalauréat in the summer ; and my father desired me

to pass some months in Italy, for the purpose of ” patching

up my

Italian, which had suffered from the ravages of time,”

before I returned to

Paris, and settled down to the study of a

profession.

” H’m,” said she, manifesting no emotion at what (in my

simplicity) I deemed

rather a felicitous metaphor ; and then, as it

were, she let me off with a

warning. ” Look out that you don’t

fall into bad company. Rome is full of

dangerous people—painters,

Bohemians, republicans, atheists. You

must be careful. I shall

keep my eye upon you.”

By-and-by, to my relief, my aunt’s director arrived, Monsignor

Parlaghi, a

tall, fat, cheerful, bustling man, who wore a silk

cassock edged with

purple, and a purple netted sash. When he

sat down and crossed his legs,

one saw a square-toed shoe with a

silver buckle, and an inch or two of

purple silk stocking. He

began at once to talk with his penitent, about

some matter to

which I (happily) was a stranger; and that gave me my

chance

to break the ice with Rosalys.

She had risen to greet the Monsignore, and now stood by the

balustrade of

the terrace, half turned towards the garden, a

slender, fragile figure, all

in white. Her dark hair swept away

from her forehead in lovely, long

undulations, and her white face,

beneath it, seemed almost spirit-like in

its delicacy, almost

immaterial.

” I am richer than I thought. I did not know I had a Cousin

Rosalys,” said

I.

It looks like a sufficiently easy thing to say, doesn’t it ? And

besides,

hadn’t I carefully composed and corrected and conned it

The Yellow Book—Vol. IX. c

beforehand,

beforehand, in the silence of my mind ? But I remember the

mighty effort of

will it cost me to get it said. I suppose it is in

the design of nature

that Eighteen should find it nervous work to

break the ice with pretty

girls. At any rate, I remember how my

heart fluttered, and what a hollow,

unfamiliar sound my voice had;

I remember that in the very middle of the

enterprise my pluck

and my presence of mind suddenly deserted me, and

everything

became a blank, and for one horrible moment I thought I was

going to break down utterly, and stand there staring, blushing,

speechless. But then I made a further mighty effort of will, a

desperate

effort, and somehow, though they nearly choked me,

the premeditated words

came out.

“Oh, we’re not real cousins,” said she, letting her

eyes shine for

a second on my face. And she explained to me just what

the

connection between us was. “But we will call ourselves cousins,”

she concluded.

The worst was over ; the worst, though Eighteen was still, no

doubt,

conscious of perturbations. I don t know how long we

stood chatting

together there by the balustrade, but presently I

said something about the

garden, and she proposed that we should

go down into it. So she led me to

the other end of the terrace,

where there was a flight of steps, and we

went down into the

garden.

The merest trifles, in such weather, with a pretty new-found

Cousin Rosalys

for a comrade, are delightful, when one is eighteen,

aren’t they ? It was

delightful to feel the yielding turf under our

feet, the cool grass curling

round our ankles—for in Roman

gardens, in those old days, it wasn t

the fashion to clip the grass

close, as on an English lawn. It was

delightful to walk in the

shade of the orange-trees, and breathe the air

sweetened by them.

The stillness, the dreamy stillness of the soft, sunny

afternoon was

delightful

delightful ; the crumbling old statues were delightful, statues of

fauns and

dryads, of Pagan gods and goddesses, Pan and Bacchus

and Diana, their noses

broken for the most part, their bodies

clothed in mosses and leafy vines.

And the flowers were delightful;

the cyclamens, with which—so

abundant were they—the walls of

the garden fairly dripped, as with a

kind of pink foam ; and the

roses, and the waxen red and white camellias.

It was delightful

to stop before the great brown old fountain, and listen

to its

tinkle-tinkle of cold water, and peer into its basin, all green with

weeds, and watch the antics of the gold-fishes, and the little

rainbows the sun struck from the spray. And my Cousin Rosalys’s

white frock

was delightful, and her voice was delightful ; and that

perturbation in my

heart was exquisitely delightful—something

between a thrill and a

tremor—a delicious mixture of fear and

wonderment and beatitude. I

had dragged myself hither to pay a

duty-call upon my grim old dragon of a

great-aunt Elizabeth ;

and here I was wandering amid the hundred delights

of a romantic

Italian garden, with a lovely, white-robed, bright-eyed sylph

of a

cousin Rosalys.

Don’t ask me what we talked about. I have only the most

fragmentary

recollection. I remember she told me that her

father and mother had died in

India, when she was a child, and

that her father (Aunt Elizabeth’s “ever so

much younger

brother”) had been in the army, and that she had lived

with

Aunt Elizabeth since she was twelve. And I remember she

asked me

to speak French with her, because in Rome she almost

always spoke Italian

or English, and she didn’t want to forget her

French ; and ” You’re, of

course, almost a Frenchman, living in

Paris.” So we spoke French together,

saying ma cousine and

mon cousin, which was very intimate and pleasant ;

and she spoke

it so well that I expressed some surprise. ” If you don’t put

on at

least

least a slight accent, I shall tell you you’re almost

a Frenchman

too,” I threatened. ” Oh, I had French nurses when I was

little,” she said, “and afterwards a French governess, till I

was sixteen.

I’m eighteen now. How old are you ? ” I had

heard that girls always liked a

man to be older than themselves,

and I answered that I was nearly twenty.

Well, and isn’t

eighteen nearly twenty ? . . . . Anyhow, as I walked back

to

my lodgings that afternoon, through the busy, twisted, sunlit

Roman

streets, Cousin Rosalys filled all my heart and all my

thoughts with a

white radiance.

* * *

You will conceive whether or not, during the months that

followed, I was an

assiduous visitor at the Palazzo Zacchinelli.

But I couldn’t spend all my time there, and in my enforced

absences I

needed consolation. I imagine I treated Aunt Eliza-

beth’s advice about

avoiding bad company as youth is wont

to treat the counsels of crabbed age.

Doubtless my most frequent

associates were those very painters and

Bohemians against whom

she had particularly cautioned me—whether

they were also re-

publicans and atheists, I don’t think I ever knew ; I

can’t

remember that I inquired, and religion and politics were

subjects

they seldom touched upon spontaneously. I dare say I joined

the

artists’ club, in the Via Margutta, the Circolo Internazionale

degl’ Artisti ; I am afraid the Caffè Greco was my favourite café ;

I

am afraid I even bought a wide-awake hat, and wore it on the

back of my

head, and tried to look as much like a painter

and Bohemian myself as

nature would permit.

Bad company ? I don’t know. It seemed to me very good

company indeed. There

was Jack Everett, tall and slim and

athletic, with his eager aquiline face,

his dark curling hair, the

most

most poetic-looking creature, humorous, whimsical, melancholy,

imaginative,

who used to quote Byron, and plan our best

practical jokes, and do the

loveliest little cupids and roses in

water-colours. He has since married

the girl he was even then

in love with, and is still living in Rome, and

painting cupids and

roses. And there was d’Avignac, le

vicomte, a young French-

man, who had been in the Diplomatic

Service, and—superlative

distinction!—”ruined himself for a

woman,” and now was

striving to keep body and soul together by giving

fencing lessons :

witty, kindly, pathetic d’Avignac—we have vanished

altogether

from each other’s ken. There was Ulysse Tavoni, the musician,

who, when somebody asked him what instrument he played,

answered

cheerily, ” All instruments.” I can testify from personal

observation that

he played the piano and the flute, the guitar,

mandoline, fiddle, and

French horn, the ‘cello and the zither.

And there was König, the Austrian

sculptor, a tiny man with a

ferocious black moustache, whom my landlady (he

having called

upon me one day when I was out), unable to remember his

transalpine name, described to perfection as ” un Orlando Furioso

—ma

molto piccolo.” There was a dear, dreamy, languid,

sentimental Pole,

blue-eyed and yellow-haired, also a sculptor,

whose name I have totally

forgotten, though we were sworn to

” hearts’ brotherhood.” He had the most

astonishing talent for

imitating the sounds of animals, the neighing of a

horse, the

crowing of a cock ; and when he brayed like a donkey, all

the donkeys within earshot were deceived, and answered him.

And then there

was Father Flynn, a jolly old bibulous priest from

Cork. An uncle of his

had fought at Waterloo ; it was great to

hear him tell of his uncle’s part

in the fortunes of the day. It was

great, too (for Father Flynn was a

fervid Irish patriot) to hear

him roar out the “Wearing of the Green.”

Between the

stanzas

stanzas he would brandish his blackthorn stick at Everett, and call

him a

“murthering English tyrant,” to our huge delectation.

There were others and others and others ; but these six

are those who come

back first to my memory. They seemed to

me very good company indeed ; very

merry, and genial, and

amusing ; and the life we led together seemed a very

pleasant

life. Oh, our pleasures were of the simplest nature, the

traditional

pleasures of Bohemia ; smoking and drinking and talking,

ramb-

ling arm-in-arm through the streets, lounging in studios, going

to

the play or perhaps the circus, or making excursions into the

country. Only, the capital of our Bohemia was Rome. The

streets through

which we rambled were Roman streets, with their

inexhaustible

picturesqueness, their unending vicissitudes : with

their pink and yellow

houses, their shrines, their fountains, their

gardens, their motley

wayfarers— monks and soldiers ; shaggy

pifferari, and contadine in

their gaudy costumes, and models

masquerading as contadine ; penitents,

beggars, water-carriers,

hawkers ; priests in their vestments, bearing the

Host, attended

by acolytes, with burning tapers, who rang little bells,

whilst

men uncovered and women crossed themselves ; and everywhere,

everywhere, English tourists, with their noses in Bædeker. It

was Rome with

its bright sun, and its deep shadows ; with its

Ghetto, its Tiber, its

Castle Sant’ Angelo ; with its churches, and

palaces, and ruins ; with its

Villa Borghese and its Pincian Hill ;

with its waving green Campagna at its

gates. We smoked and

talked and drank—Chianti, of course, and sunny

Orvieto, and

fabled Est-Est-Est, all in those delightful pear-shaped,

wicker-

covered flasks, which of themselves, I fancy, would confer a

flavour upon indifferent wine. We made excursions to Tivoli

and

Frascati, to Monte Cavo and Nemi, to Acqua Acetosa. We

patronised

Pulcinella, and the marionettes, and (better still) the

imitation

imitation marionettes. We blew horns on the night of

Epiphany,

we danced at masked balls, we put on dominoes and romped in

the

Corso during carnival, throwing flowers and confetti, and strug-

gling to extinguish other people’s moccoli. And on

rainy days

(with an effort I can remember that there were some rainy days),

Everett and I would sit with

d’Avignac in his fencing gallery, and

talk and smoke, and smoke and talk

and talk. D’Avignac was

six-and-twenty, Everett was twenty-two, and I was

“nearly

twenty.” D’Avignac would tell us of his past, of his

adventures

in Spain and Japan and South America, and of the lady for

the love of whom he had come to grief. Everett and I would

sigh

profoundly, and shake our heads, and exchange sympathetic

glances, and

assure him that we knew what love was—we were

victims of unfortunate

attachments ourselves. To each other we

had confided everything, Everett

and I. He had told me all

about his unrequited passion for Maud Eaton, and

I had

rhapsodised to him by the hour about Cousin Rosalys. “But

you,

old chap, you’re to be envied,” he would cry. ” Here you

are in the same

town with her, by Jove ! You can see her,

you

can plead your cause. Think of that. I wish I had half

your luck. Maud is

far away in England, buried in a country-

house down in Lancashire. She

might as well be on another

planet, for all the good I get of her. But

you—why, you

can see your Cousin Rosalys this very hour if you like!

Oh,

heavens, what wouldn’t I give for half your luck ! ” The wheel

of

Time, the wheel of Time ! Everett and Maud are married, but

Cousin Rosalys

and I…. Heigh-ho ! I wonder whether, in

our thoughts of ancient days, it

is more what we remember or

what we forget that makes them sweet ? Anyhow,

for the

moment, we forget the dismal things that have happened since.

* * *

Yes,

Yes, I was in the same town with her, by Jove ; I could see

her. And indeed I did see her many times every week. Like

the villain

in a melodrama, I led a double life. When I was not

disguised as a

Bohemian, in a velvet jacket and a wide-awake,

smoking and talking and

holding wassail with my boon companions,

you might have observed a young

man attired in the height of the

prevailing fashion (his top-hat and

varnished boots flashing fire in

the eyes of the Roman populace), going to

call on his Aunt Eli-

zabeth. And his Aunt Elizabeth, pleased by such

dutiful atten-

tions, rewarded him with frequent invitations to dinner. Her

other guests would be old ladies like herself, and old gentlemen,

and

priests, priests, priests. So that Rosalys and I, the only

young ones

present, were naturally paired together. After dinner

Rosalys would play

and sing, while I hung over her piano. Oh,

how beautifully she played

Chopin ! How ravishingly she sang !

Schubert’s Wohin, and Röslein, Röslein,Röslein roth ; and Gounod’s

Sérénade and his Barcarolle :

” Dites la jeune belle,

Ou voulez-vous aller ? “

And how angelically beautiful she looked ! Her delicate, pale

face, and her

dark, undulating hair, and her soft red lips ; and then

her eyes—her

luminous, mysterious dark eyes, in whose depths,

far, far within, you could

discern her spirit shining starlike. And

her hands, white and slender and

graceful, images in miniature of

herself; with what incommunicable wonder

and admiration I used

to watch them as they moved above the keys. ” A woman

who

plays Chopin ought to have three hands—two to play with, and

one for the man who’s listening to hold.” That was a pleasantry

which

I meditated much in secret, and a thousand times aspired

to murmur in the

player’s ear, but invariably, when it came to the

point

point of doing so, my courage failed me. ” You can see her, you

can plead

your cause.” Bless me, I never dared even vaguely to

hint that I had any

cause to plead. I imagine young love is

always terribly afraid of revealing

itself to its object, terribly afraid

and terribly desirous. Whenever I was

not in cousin Rosalys’s

presence, my heart was consumed with longing to

tell her that I

loved her, to ask her whether perhaps she might be not

wholly

indifferent to me ; I made the boldest resolutions, committed to

memory the most persuasive declarations. But from the instant I

was in her presence again—mercy, what panic

seized me. I

could have died sooner than speak the words that I was dying

to

speak, ask the question I was dying to ask.

I called assiduously at the Palazzo Zacchinelli, and my aunt

bade me to

dinner a good deal, and then one afternoon every week

she used to drive

with Rosalys on the Pincian. There was one

afternoon every week when all

Rome drove on the Pincian ; was

it Saturday ? At any rate, you may be very

sure I did not let

such opportunities escape me for getting a bow and a

smile from

my cousin. Sometimes she would leave the carriage and join me,

while Aunt Elizabeth, with Sandro in her lap, drove on, round and

round the consecrated circle ; and we would stroll together in the

winding

alleys, or stand by the terrace and look off over the roofs

of the city,

and watch the sunset blaze and fade behind St. Peter’s.

You know that

unexampled view—the roofs of Rome spread out

beneath you like the

surface of a troubled sea, and the dome of

St. Peter’s, an island rising in

the distance, and the sunset sky

behind it. We would stand there in silence

perhaps, at most say-

ing very little, while the sunset burned itself out ;

and for one of

us, at least, it was a moment of ineffable, impossible

enchantment.

She was so near to me, so near, the slender figure in the

pretty

frock, with the dark hair, and the captivating hat, and the furs

;

with

with her soft glowing eyes, with her exquisite fragrance of girl-

hood ; she

was so near to me, so alone with me, despite the crowd

about us, and I

loved her so ! Oh, why couldn’t I tell her ?

Why couldn’t she divine it ?

People said that women always

knew by intuition when men were in love with

them. Why

couldn’t Rosalys divine that I loved her, how I loved her, and

make me a sign, and so enable me to speak

?

Presently—and all too soon—she would return to the carriage,

and drive away with Aunt Elizabeth ; and I, in the lugubrious

twilight,

would descend the great marble Spanish staircase (a

perilous path, amongst

models and beggars and other things) to

the Piazza, and seek out Jack

Everett at the Caffe Greco.

Thence he and I would go off to dine together

somewhere, con-

doling with each other upon our ill-starred passions.

After

dinner, pulling our hats over our eyes, two desperately tragic

forms,

we would set ourselves upon the traces of d’Avignac and König

and Father Flynn, determined to forget our sorrows in an evening

of

dissipation, saying regretfully, ” These are the evil courses to

which the

love of woman has reduced us—a couple of the best-

meaning fellows

in Christendom, and surely born for better ends.”

When we were children

(hasn’t Kenneth Grahame written it for

us in a

golden book?) we played at conspirators and pirates.

When we were a little

older, and Byron or Musset had superseded

Fenimore Cooper, some of us found

there was an unique excite-

ment to be got from the game of Blighted Beings.

Oh, why couldn’t I tell her ? Why couldn’t she divine it, and

make me an

encouraging sign ?

* * *

But of course, in the end, I did tell her. It was on the night

of my

birthday. I had dined at the Palazzo Zacchinelli, and with

the

the dessert a great cake was brought in and set before me. A

number of

little red candles were burning round it, and embossed

upon it in frosting

was this device :

A birthday-piece

From Rosalys,

Wishing birthdays more in plenty

To her cousin ” nearly twenty.”

And counting the candles, I perceived they were nineteen.

Probably my joy was somewhat tempered by confusion, to think

that my little

equivocation on the subject of my age had been dis-

covered. As I looked up

from the cake to its giver, I met a pair

of eyes that were gleaming with

mischievous raillery ; and she

shook her head at me, and murmured, ” Oh,

you fibber ! ”

” How on earth did you find out ? ” I wondered.

” Oh—a little bird,” laughed she.

” I don’t think it’s at all respectful of you to call Aunt Elizabeth

a

little bird,” said I.

After dinner we went out upon the terrace. It was a warm

night, and there

was a moon. A moonlit night in Italy—dark

velvet shot with silver.

And the air was intoxicant with the

scent of hyacinths. We were in March ;

the garden had become

a wilderness of spring flowers, narcissi and

jonquils, crocusses,

anemones, tulips, and hyacinths ; hyacinths,

everywhere hyacinths.

Rosalys had thrown a bit of white lace over her hair.

Oh, I

assure you, in the moonlight, with the white lace over her hair,

with her pale face, and her eyes, her shining, mysterious

eyes—oh,

I promise you, she was lovely.

” How beautiful the garden is, in the moonlight, isn’t it ? ” she

said. “The

shadows, and the statues, and the fountains. And

how sweet the air is.

They’re the hyacinths that smell so sweet.

The

The hyacinth is your birthday flower, you know. Hyacinths

bring happiness to

people born in March.”

I looked into her eyes, and my heart thrilled and thrilled. And

then,

somehow, somehow …. Oh, I don’t remember what I

said ; only, somehow,

somehow …. Ah, but I do remember

very clearly what she answered—so

softly, so softly, while her

hand lay in mine. I remember it very clearly,

and at the memory,

even now, years afterwards, I confess my heart thrills

again.

We were joined, in a minute or two, by Monsignor Parlaghi,

and we tried to

behave as if he were not unwelcome.

* * *

Adam and Eve were driven from Eden for their guilt ; but it

was Innocence

that lost our Eden for Rosalys and me. In our

egregious innocence, we had

determined that I should call upon

Aunt Elizabeth in the morning, and

formally demand her sanction

to our engagement ! Do I need to recount the

history of that

interview ? Of my aunt’s incredulity, that gradually changed

to

scorn and anger ? Of how I was fleered at and flouted, and

taunted

with my youth, and called a fool and a coxcomb, and sent

about my business

with the information that the portals of the

Palazzo Zacchinelli would

remain eternally closed against me for

the future, and that my people ”

would be written to ” ? I was

not even allowed to see my cousin to say

good-bye. ” And mind

you, we’ll have no letter writing,” cried Aunt

Elizabeth. ” I

shall forbid Rosalys to receive any letters from you.”

Guilt (we are taught) can be annulled, and its punishment

remitted, if we do

heartily repent. But innocence ? Goodness

knows how heartily I repented ;

yet I never found that a penny-

weight of the punishment was remitted. At

the week’s end I got

a letter from my people recalling me to Paris. And I

never saw

Rosalys

Rosalys again. And some years afterwards she married an Italian,

a nephew of

Cardinal Badascalchi. And in 1887, at Viareggio,

she died. . . . .

Eh bien, voila! There is the little inachieved, the

little unful-

filled romance, written for me in her name, Cousin

Rosalys.

What of it ? Oh, nothing—except—except—Oh,

nothing.

” All good things come to him who waits.” Perhaps. But

we know how apt they

are to come too late ; and—sometimes

they come too early.

Wolf-Edith

By Nora Hopper

WOLF-EDITH dwells on the wild grey down

Where the gorse burns gold and the bent grows brown

She goes as light as a withered leaf,

She has not tasted of joy or grief.

With wild things’ beauty her face is fair,

A bramble-flower in a web of hair,

Fine as thistle-down tossed abroad

When the soul of the thistle goes home to God.

Her lips know songs that will lure away

A dull-eared clown from his buxom may.

But never a man she hath hearkened sing

And followed home from her wandering—

And never a man the bents above

Might call Wolf-Edith his mate and love.

Oh

Oh fair are the women of stead and town,

And winds are sharp on the barren down :

Yet heather blooms in the wind’s despite,

And wild-fire burns in the blackest night :

And out on the moor and the mists thereof

Wild Wolf-Edith has found her a love.

She knows not his kindred’s place and name,

But her sleeping soul he hath set aflame.

He has kindled her soul with his first long kiss :

How shall she quit such a grace as this ?

A barrow far on the windy heath,

Her love is a handful of dust beneath.

For here when Senlac was lost and won,

Her lover perished for Godwin’s son :

Died, and was laid here to sleep his fill

While Saxons bent to a Norman’s will.

Still Normans sit on the Saxon throne ;

A Saxon girl to the moor has gone,

A Saxon’s ghost is her lover sworn

And who shall sever them, night or morn ?

One in the barrow and one above ;

Wild Wolf-Edith has found her a love.

And

And sweeter than ever her wild songs go

Drifting down to the thorpes below.

Wolf-Edith’s pale as a winter-rose

When lonely over the bents she goes,

Though sweet i’ the gorses the wild bees hum—

But when the night and her lover come,

He lifts her soul as a flickering fire

Is lifted up, with the wind’s desire.

His eyes drink light from Wolf-Edith’s face,

‘Gainst the time he goes to his sleeping place :

Dead and living the bents above

Wild Wolf-Edith has found her a love.

The Yellow Book Vol. IX.

On the Art of Yvette Guilbert

By Stanley V. Makower

IN a few days Yvette Guilbert will be here once more, and all

London will be

flocking to Leicester Square to secure seats at

the Empire Theatre. The

chief cities of Europe and America

through which the French singer has now

passed in triumphal

procession have subscribed to an almost unparalleled

success with

a truly rare enthusiasm. One obscure town in Europe* is

said

to have sprung into notoriety owing to an obstinate refusal to

recognise a genius to which the whole civilised world has done

honour. But

this, the sole exhibition of hostility with which

the great artist has met

in her wide travels, has only served to

enhance her reputation.

The extraordinary wave of enthusiasm that greets Yvette

Guilbert when she is

here is only another proof that London is

the most cosmopolitan city in the

world. We are constantly

having evidence of this, not the least striking

being that last year

a play by a German author † was being acted at

three different

London theatres at the same time in French, German, and

Italian.

Nevertheless it is singular that a genius essentially French,

though

in

* Napoli—on the western coast of Italy. † Suderrmann’s ” Die Heimath.”

in no sense a type of France, exercised in a department of art

peculiar to

one side of Paris, should win unanimous applause from

every class of London

society.

The crisis which the drama has reached in England and in

France is in some

respects the same, but there is a point at which

the parallel ceases. In

both countries the drama is corrupt, but

France with characteristic

precocity is the first to teach the lesson.

It has said the last word about

the drama of this generation in

providing the glorious impossibility of a

Sarah Bernhardt. It is

on the great actress that has fallen the task of

showing that drama

written and conceived from outside has reached its

culminating

point in the latest manuscript plays from the pen of

Victorien

Sardou. No one with a personality less splendid could have

proved that the history of the drama during this century has been

almost

exclusively the history of an art entirely alien to that which

made

Shakespeare a writer of plays. In England we have no

personality great

enough to sum up the whole situation, and the

consequence is that we are

still at the mercy of those who line the

pavement of the Haymarket with

gold to witness ” Trilby,” or

who pour with equal profusion to the doors of

the St. James’ theatre

to see Mr. Alexander in ” The Prisoner of Zenda.”

And all the

conscientious endeavours of Mr. Pinero and Mr. H. A. Jones

fail

to stem the tide, for the very simple reason that they are

neither

of them great men.

It is to Norway then that we have to look for the future welfare

of the

drama, and whilst Henrik Ibsen has given a fresh impulse

to the literary

minds of France and England, an impulse which

has as yet had insufficient

time to translate itself to any appreciable

extent into the dramatic

literature of these countries, there is a

temporary transference of the

popular interest in England from

the Stage to the Music Hall, in France

from the Stage to the

Cabaret

Cabaret or the Café Chantant. But there is a wide difference

between the

Music Hall and the Cabaret. The history of both

is still to be written, but

it will be found that the circumstances,

the traditions or the art

displayed in each are different, and, more

important than all, the literary

value and artistic significance of

each are different. In England the text

of the songs sung is

written by illiterate people, the artistic part lies

in the performer,

and even then the performer is quite unconscious of his

art. In

France the songs written for the Cabaret are mostly written,

as

we shall see later on, by men of culture, of University education,

and though there is perhaps on the whole less ability to be found

in the

ranks of the French than in those of the English performers,

each performer

in France knows that he is engaged in an artistic

pursuit requiring talent

of a special kind.

Yvette Guilbert constitutes the one brilliant exception to the

general

statement, advanced with some hesitation through want of

sufficient

knowledge, that we have more individual ability on the

Music Hall Stage

than the French have in the Café Chantant.

But the weight of Yvette

Guilbert’s individuality goes far to

counterbalance the deficiency if there

is one. It is an individuality

so marked, so rare, that it almost

constitutes by its own force a

development by itself, independent of a

place in the history of its

art, in the same way that the strength of

Chopin’s individuality

makes it almost impossible to put him into relation

with other

composers of music. Curiously enough we find that during

the

life-time of Chopin there was the same tendency to call him

”

modern,” ” new-fangled ” and so forth, that we observe in those

critics who

have used the word fin-de-siècle in connection

with

Yvette Guilbert. In both cases the epithets are idle. It is the

misfortune which attends all histrionic art that it cannot be handed

down

to posterity, but if it were possible to preserve something of

the

the art of Yvette Guilbert, we should want to preserve the beauty

which she

conceives internally, the look of inward imagination

that comes from her

eyes, whilst the simplicity of her dress, the

almost conventional quality

of her gestures, and the long black

gloves, which she adopted at the

beginning of her career and has

never abandoned, are at the most evidence

of an unerring taste and

of a distinguished simplicity.

There is then nothing essentially contemporary in Yvette

Guilbert, nor

indeed is there anything contemporary in the form

of the art, which her

instinct has guided her to select for the dis-

play of her genius, for it

is a compromise between the dramatic

and lyrical form which has its

parallel in early classical times.

Nothing could equal the obtuseness of

more than one English

critic who has advised Yvette Guilbert to forsake

this quasi-lyrical

form for the drama—advice which goes conclusively

to prove that