THE VENTURE: An Annual of Art and Literature

THE VENTURE

An Annual of Art and Literature

Edited by

LAURENCE HOUSMAN AND

W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM.

LONDON

AT JOHN BAILLIE’S

1, PRINCES TERRACE,

HEREFORD ROAD, W. 1903.

PRINTED AT THE PEAR TREE PRESS,

15 HOLBORN, LONDON, E. C.

LITERARY CONTENTS.

PAGE

When Bony Death Has Chilled Her Gentle Blood by John Masefield. 1

The Philosophy of Islands by G. K. Chesterton. 2

The Market Girl by Thomas Hardy. 10

Open Sesame by Charles Marriott. 13

To Any Householder by Mrs. Meynell. 31

The Oracles by A. E. Housman. 39

The Genius of Pope by Stephen Gwynn. 40

Poor Little Mrs. Villiers by Netta Syrett. 53

Blindness by John Masefield. 74

The Merchant Knight by Richard Garnett. 77

Earth’s Martyrs by Stephen Phillips. 112

The Gem and Its Setting by Violet Hunt. 115

Marriage in Two Moods by Francis Thompson. 131

An Indian Road-Tale by S. Boulderson. 133

Madame de Warens by Havelock Ellis. 136

The Clue by Laurence Binyon. 158

Richard Farquharson by May Bateman. 161

Jill’s Cat by E. F. Benson. 175

Proverbial Romances by Laurence Housman. 187

Marriages are Made in

Heaven by W. Somerset Maugham. 209

A Concert at Clifford’s Inn by John Todhunter. 235

WOOD-CUTS.

FRONTISPIECE

The Dove Cot by Charles Hazelwood Shannon.

PAGE

John Woolman by Reginald Savage. viii

Psyche’s Looking Glass by Charles S. Ricketts. 11

Pan and Psyche by T. Sturge Moore. 29

Queen of the Fishes by Lucien Pissarro. 37

Birdalone by Bernard Sleigh. 51

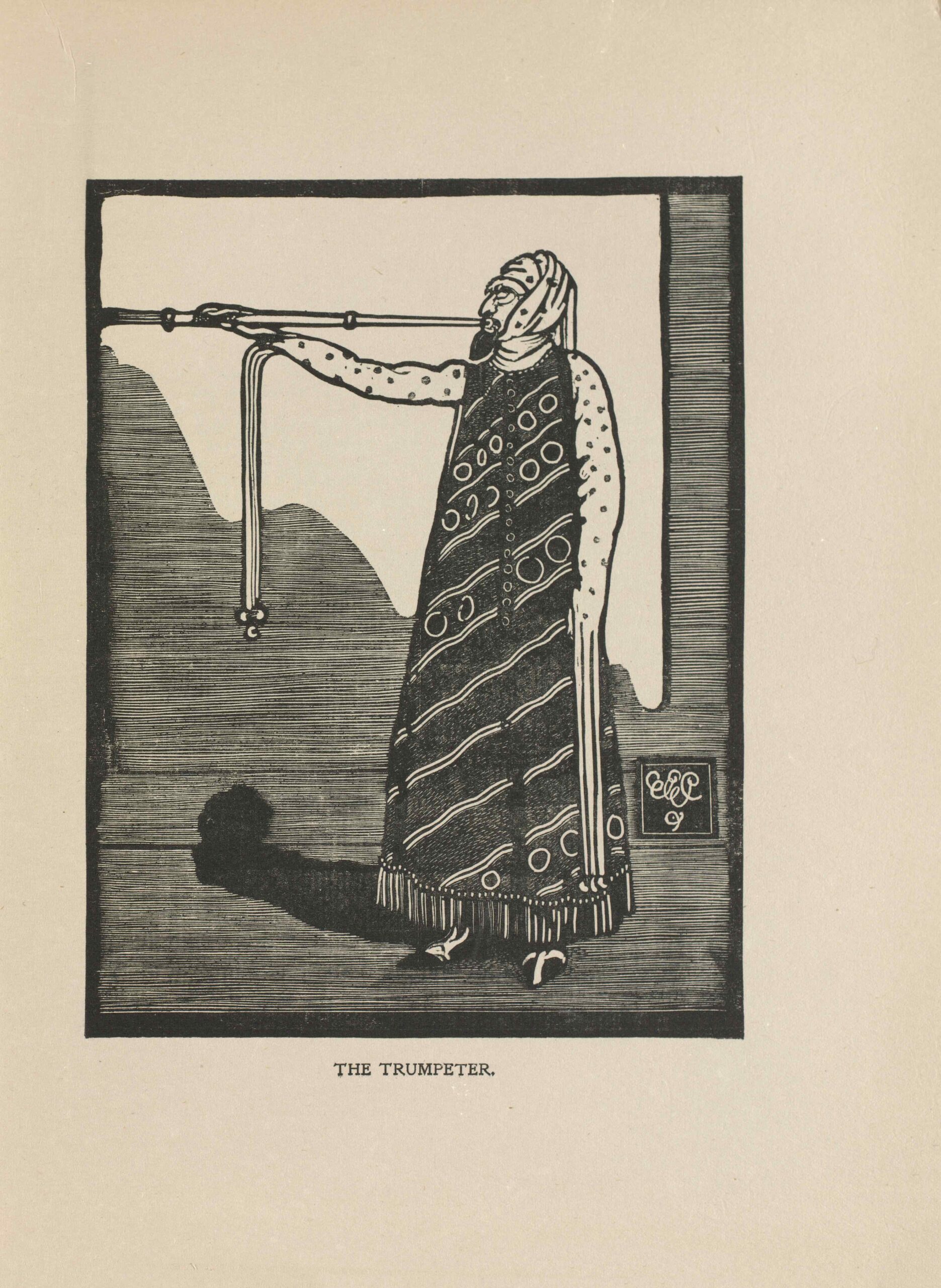

The Trumpeter by E. Gordon Craig. 75

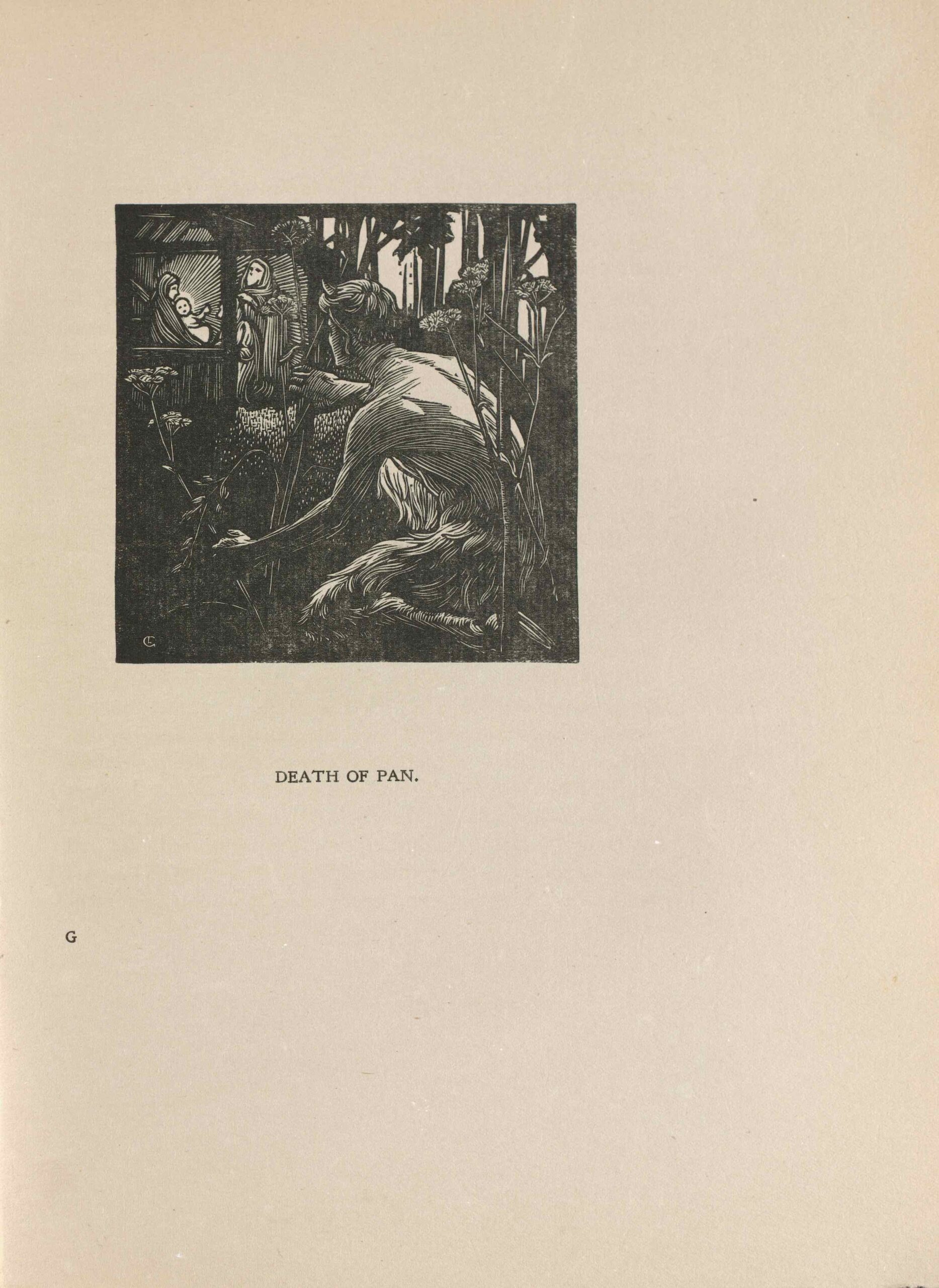

The Death of Pan by Louise Glazier. 97

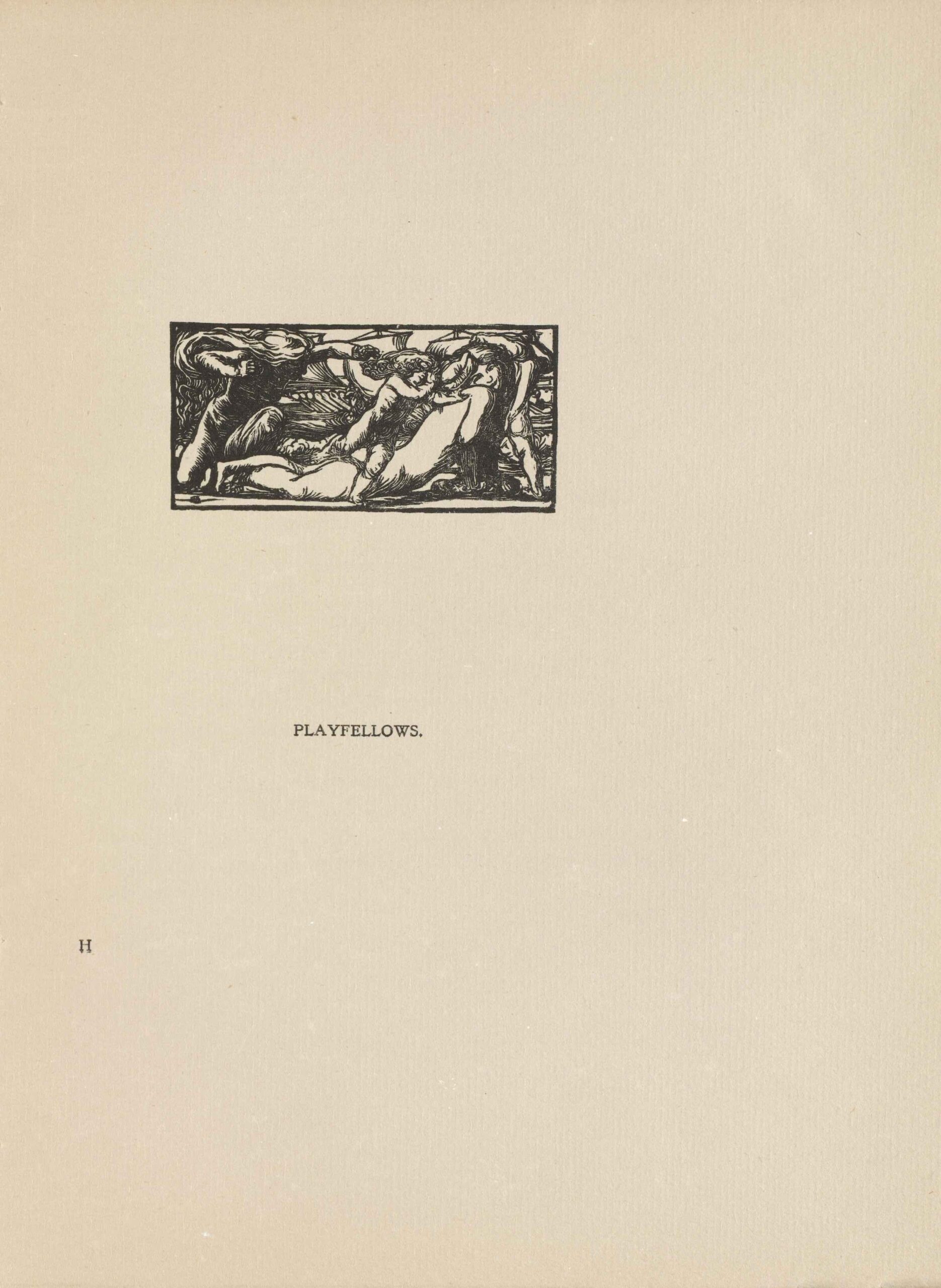

Playfellows by T. Sturge Moore. 113

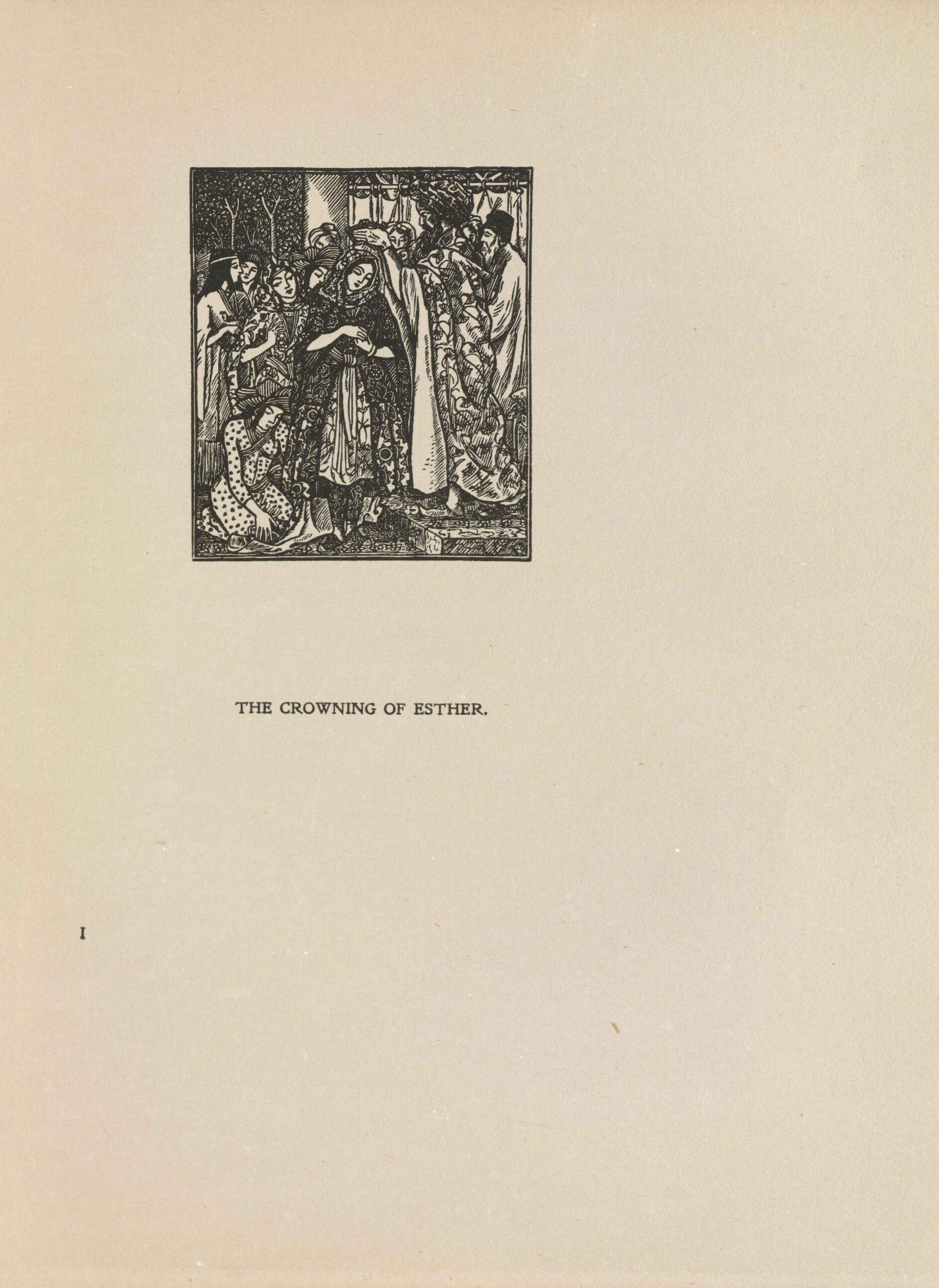

The Crowning of Esther by Lucien Pissarro. 129

Daphne and Apollo by Elinor Monsell. 159

The World is old to-night by Paul Woodroffe. 173

The Gabled House by Sydney Lee. 185

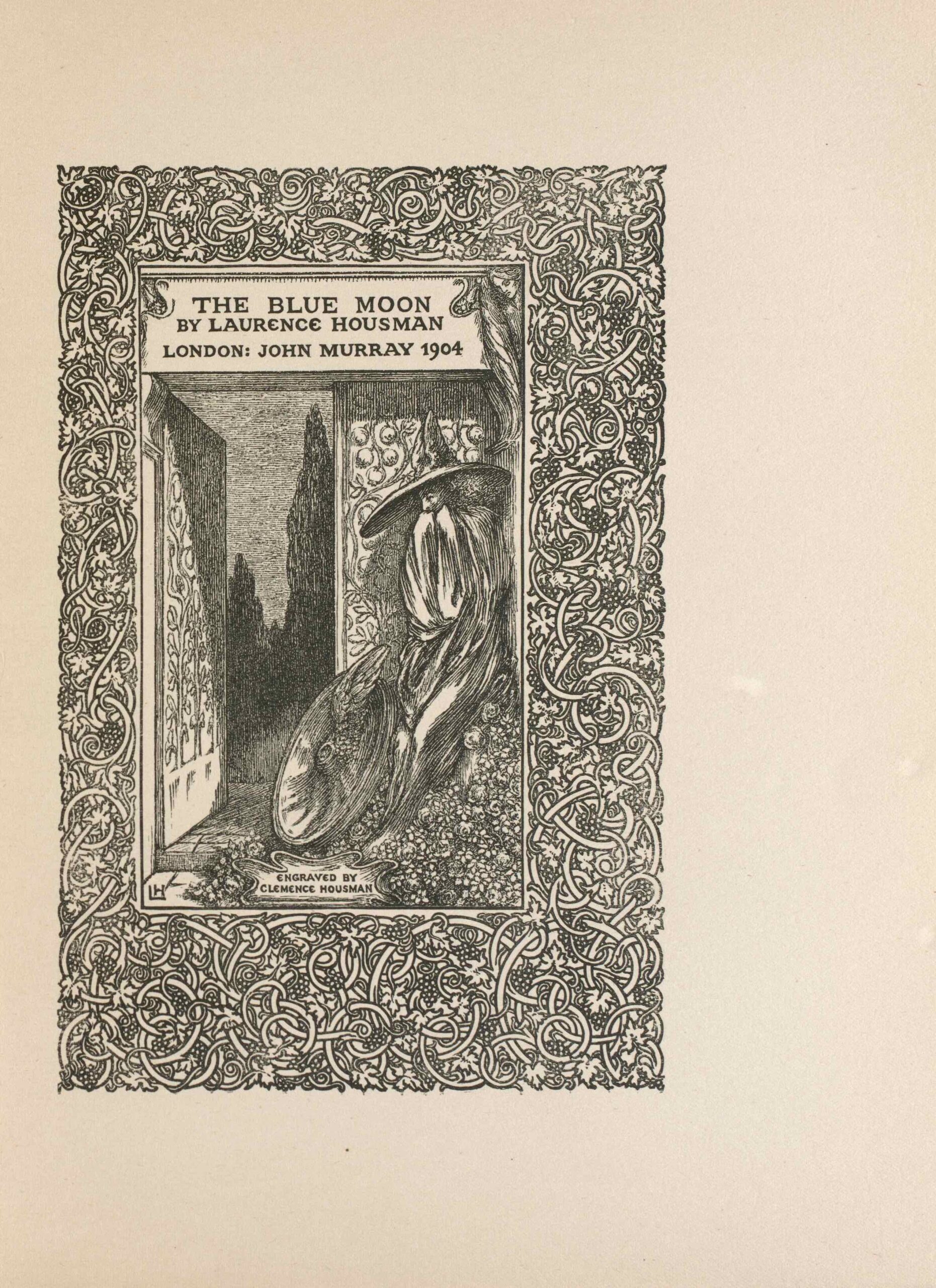

The Blue Moon by Laurence Housman. 207

The Bather by Bernard Sleigh. 231

The Editors have to thank the Essex House Press for permission

to print the “John Woolman” engraving of Mr. Reginald Savage;

Mr. Alexander Moring for the use of Mr. Paul Woodroffe’s illus-

tration to the song “ The World is Old To-night,” published with

music by the De La More Press; and Mr. John Murray for first

use of “ The Blue Moon ” title-page.

WHEN BONY DEATH HAS CHILLED HER GENTLE BLOOD.

When bony Death has chilled her gentle blood

And dimmed the brightness of her wistful eyes,

And stamped her glorious beauty into mud

By his old skill in hateful wizardies.

When an old lichened marble strives to tell

How sweet a grace, how red a lip was hers ;

When rheumy gray-beards say, “I knew her well,”

showing the grave to curious worshippers.

When all the roses that she sowed in me

Have dripped their crimson petals and decayed

Leaving no greenery on any tree

That her dear hands in my heart’s garden laid,

Then grant, old Time, to my green mouldering skull

These songs may keep her memory beautiful.

JOHN MASEFIELD.

THE PHILOSOPHY OF ISLANDS.

Suppose that in some convulsion of the planets there fell

upon this earth from Mars, a creature of a shape totally

unfamiliar, a creature

about whose actual structure we were

of necessity so dark that we could not tell

which was creature

and which was clothes. We could see that it had, say, six

red tufts on its head, but we should not know whether they

were a highly

respectable head-covering or simply a head.

We should see that the tail ended in

three yellow stars, but it

would be very difficult for us to know whether this was

part

of a ritual or simply part of a tail. Well, man has been from

the

beginning of time this unknown monster. People have

always differed about what part

of him belonged to himself,

and what part was merely an accident. People have

said

successively that it was natural to him to do everything and

anything

that was diverse and mutually contradictory; that

it was natural to him to worship

God, and natural to him to

be an atheist; natural to him to drink water, and

natural to

him to drink wine; natural to him to be equal, natural to be

unequal; natural to obey kings, natural to kill them. The

divergence is quite sufficient to justify us in asking if there are

not many

things that are really natural, which really appear

early and strong in every

normal human being, which are not

embodied in any of his after affairs. Whether

there are

not morbidities which are as fresh and recurrent as the

flowers of

spring. Whether there are not superstitions whose

darkness is as wholesome as the

darkness that falls nightly

on all living things. Whether we have not treated

things

essential as portents; whether we have not seen the sun as a

meteor, a

star of ill-luck.

It would at least appear that we tend to become

separated

from what is really natural, by the fact that we always talk

about those people who are really natural as if they were goblins.

There are three

classes of people for instance, who are in a

greater or less degree elemental:

children, poor people, and to

some extent, and in a darker and more terrible

manner, women.

The reason why men have from the beginning of literature

talked

about women as if they were more or less mad, is

simply because women are natural,

and men, with their

formalities and social theories, are very artificial. It is the

same

with children; children are simply human beings who are

allowed to do

what everyone else really desires to do, as for

instance, to fly kites, or when

seriously wronged to emit pro-

longed screams for several minutes. So again, the

poor man

is simply a person who expends upon treating himself and his

friends

in public houses about the same proportion of his

income as richer people spend on

dinners or hansom cabs, that

is a great deal more than he ought. But nothing can be done

until people give up

talking about these people as if they were

too eccentric for us to understand,

when, as a matter of fact, if

there is any eccentricity involved, we are too

eccentric to under-

stand them. A poor man, as it is weirdly ordained, is

definable

as a man who has not got much money; to hear philan-

thropists talk

about him one would think he was a kangaroo.

A child is a human being who has not

grown up; to hear

educationalists talk one would think he was some variety of

a

deep-sea fish. The case of the sexes is at once more obvious

and more

difficult. The stoic philosophy and the early church

discussed woman as if she were

an institution, and in many

cases decided to abolish her. The modern feminine

output of

literature discusses man as if he were an institution, and

decides

to abolish him. It can only timidly be suggested that

neither man nor woman are

institutions, but things that are

really quite natural and all over the place.

If we take children for instance, as examples of the

uncor-

rupted human animal, we see that the very things which

appear in

them in a manner primary and prominent, are the

very things that philosophers have

taught us to regard as

sophisticated and over-civilised. The things which

really

come first are the things which we are accustomed to think

come last.

The instinct for a pompous intricate and recurring

ceremonial for instance, comes

to a child like an organic

hunger; he asks for a formality as he might ask for a

drink of

water.

Those who think, for instance, that the thing called

super-

stition is something heavily artificial, are very numerous; that

is those who think that it has only been the power of priests or

of some very

deliberate system that has built up boundaries,

that has called one course of

action lawful and another un-

lawful, that has called one piece of ground sacred and

another

profane. Nothing it would seem, except a large and powerful

conspiracy

could account for men so strangely distinguishing

between one field and another,

between one city and another,

between one nation and another. To all those who

think

in this way there is only one answer to be given. It is to

approach each

of them and whisper in his ear: “Did you

or did you not as a child try to step on

every alternate paving-

stone?” Was that artificial and a superstition ? Did

priests

come in the dead of night and mark out by secret signs the

stones on

which you were allowed to tread? Were children

threatened with the oubliette or the

fires of Smithfield if they

failed to step on the right stone? Has the Church

issued a

bull “Quisquam non pavemento?” No! On this point on

which we were

really free, we invented our servitude. We

chose to say that between the first and

the third paving-stone

there was an abyss of the eternal darkness into which

we

must not fall. We were walking along a steady, and safe and

modern road,

and it was more pleasant to us to say that we

were leaping desperately from peak to

peak. Under mean and

oppressive systems it was no doubt our instinct to free

our

-selves. But this truth written on the paving-stones is of even

greater emphasis, that under liberal systems it was our instinct

to limit

ourselves. We limited ourselves so gladly that we

limited ourselves at random, as

if limitation were one of the

adventures of boyhood.

People sometimes talk as if everything in the religious

history of men had been done by officials. In all probability

things like the

Dionysian cult or the worship of the Virgin

were almost entirely forced by the

people on the priesthood.

And if children had been sufficiently powerful in the

state,

there is no reason why this paving-stone religion should not

have been

accepted also. There is no reason why the streets

up which we walk should not be

emblazoned so as to com-

memorate this eternal fancy, why black stones and

white

stones alternately, for instance, should not perpetuate the

memory of a

superstition as healthy as health itself.

For what is the idea in human nature which lies at the

back

of this almost automatic ceremonialism? Why is it that a

child who

would be furious if told by his nurse not to walk

off the curbstone, invents a

whole desperate system of foot-

holds and chasms in a plane in which his nurse can

see little

but a commodious level? It is because man has always had

the

instinct that to isolate a thing was to identify it. The flag

only becomes a flag

when it is unique; the nation only becomes

a nation when it is surrounded; the hero

only becomes a hero

when he has before him and behind him men who are not

heroes; the paving-stone only becomes a paving-stone when

it has before it and

behind it things that are not paving-stones.

There are two other obvious instances, of course, of

the

same instinct, the perennial poetry of islands, and the perennial

poetry of ships. A ship like the Argo or the Fram is valued

by the mind because it

is an island, because, that is, it carries

with it floating loose on the desolate

elements the resources,

and rules, and trades, and treasuries of a nation, because

it

has ranks, and shops, and streets, and the whole clinging like

a few

limpets to a lost spar. An island like Ithaca or England

is valued by the mind

because it is a ship, because it can find

itself alone and self-dependent in a

waste of water, because its

orchards and forests can be numbered like bales of

merchandise,

because its corn can be counted like gold, because the starriest

and dreariest snows upon its most forsaken peaks are silver

flags flown from

familiar masts, because its dimmest and most

inhuman mines of coal or lead below

the roots of all things

are definite chatels stored awkwardly in the lowest locker

of

the hold.

In truth nothing has so much spoilt the right artistic

attitude

as the continual use of such words as ” infinite” and

“immeasur-

able.” They were used rightly enough in religion because

religion,

by its very nature, consists of paradoxes. Religion

speaks of an identity which is

infinite, just as it spoke of an

identity that was at once one and three, just as

it might

possibly and rightly speak of an identity that was at once

black and white.

The old mystics spoke of an existence without end or a

happiness without end, with a deliberate defiance, as they

might have spoken of a bird without wings or a sea

without

water. And in this they were right philosophically, far more

right than the world would now admit because all things grow

more paradoxical as we

approach the central truth. But for

all human imaginative or artistic purposes

nothing worse

could be said of a work of beauty than that it is infinite; for

to be infinite is to be shapeless, and to be shapeless is to be

something more than

mis-shapen. No man really wishes a

thing which he believes divine to be in this

earthly sense

infinite. No one would really like a song to last for ever, or

a

religious service to last for ever, or even a glass of good ale

to last for ever.

And this is surely the reason that men have

pursued towards the idea of holiness,

the course that they have

pursued; that they have marked it out in particular

spaces,

limited it to particular days, worshipped an ivory statue,

worshipped

a lump of stone. They have desired to give to it

the chivalry and dignity of

definition, they have desired to save

it from the degradation of infinity. This is

the real weakness

of all imperial or conquering ideals in nationality. No one

can love his country with the particular affection which is

appropriate to the

relation, if he thinks it is a thing in its

nature indeterminate, something which

is growing in the night,

something which lacks the tense excitement of a

boundary.

No Roman citizen could feel the same when once it became

possible

for a rich Parthian or a rich Carthaginian to become

a Roman citizen by waving his

hand. No man wishes the

thing he loves to grow, for he does not wish it to alter.

No

Imperialist would be pleased if he came home in the evening

from business and

found his wife eight feet high.

The dangers upon the side of this transcendental

insularity

are no doubt considerable. There lies in it primarily the

great

danger of the thing called idolatry, the worship of the object

apart

from or against the idea it represents. But he must

surely have had a singular

experience who thinks that this

insular or idolatrous fault is the particular fault

of one age.

We are not likely to suffer from any painful resemblance to

the

men of Thermopylae, the Zealots, who raged round the

fall of Jerusalem, to the

thunderbolts of Eastern faith and

valour who hurled themselves on the guns of Lord

Kitchener.

If we are rushing upon any destruction it is not, at least, upon

this.

G. K. CHESTERTON.

THE MARKET GIRL.

(Country Song.)

I.

Nobody took any notice of her as she stood on the causey-

kerb,

A-trying to sell her honey and apples, and bunches of garden

herb;

And if she had offered to give her wares, and herself with

them too, that day,

I doubt if a soul would have cared to take a bargain so choice

away.

II.

But chancing to trace her sunburt grace that morning as I

passed nigh,

I went and I said, “Poor maidy, dear! And will none o’ the

people buy?”

And so it began; and soon we knew what the end of it all

must be,

And I found that though no others had bid, a prize had been

won by me.

THOMAS HARDY.

OPEN SESAME.

Interested strangers who tried to talk to Mr. Trembath

about the West Country were apt to be disappointed because,

although he had many

memories, he found it difficult at the

moment to get hold of the proper end. If you

happen to be on

Trevenen Quay towards the end of September you may see

fishermen home from the North Sea groping in the hold of a

lugger for the tail of a

herring net. When found it is pulled

out, not in yards, but in miles. So with Mr.

Trembath’s

memories. A chance word more often than not apparently

irrelevant,

put the thread into his hand, and you found it just

as well to sit down while the

grey man in a toneless voice

reeled you off a whole warp of his life. Only—to

pursue the

simile—in his case you had not only the net but all the fish

as

well; bright and curious, so vivid and explicit that if you had

any

imagination you tasted the brine on your lips, and saw

the little cows over the

ash-tops climbing the flank of Carn

Leskys. Like the ancient mariner, Mr. Trembath

found relief

rather than pleasure in telling his reminiscences; indeed, it is

probable that he craved forgetfulness. They did their best in

Packer’s Rents to make him forget, but an inheritance of six

centuries is perhaps

not the best preparation for a countryman

coming to live in London. The traditions

of six hundred

years, and the flower soft though ineffaceable impressions of

sixty others by moor and sea tend to use up a man’s acquisi-

tive powers, so that

the facts of to-day, however striking, are

not properly assimilated, and are always

novel.

Thus, after five years, Mr. Trembath still talked about

the wonderful things they did in London Churchtown. If

he had been capable of

expressing himself clearly, or even of

retaining a definite idea in his nebulous

mind, he would have

told you that the most surprising things in London were

the

milk and the children. He never found fault with the milk;

it was just too

perplexing for that. Mr. Trembath took in

the milk because Mable Elsie, his

daughter-in-law, found his

invincible innocence a convenient barrier to

importunate

creditors. Every day when the milk had been thrown from

the

measure into the jug with that masterly “plop” which

only the London milkman can

achieve, Mr. Trembath peered

into the ostentatiously foaming fluid and muttered

“Well well,”

much as if he had seen a cat with wings. Every day he

meant to

look for the machinery by which the milk was made,

but forgot in the fresh wonder

of its appearance. He never

got so far as criticism, partly from courtesy, party

because

the milkman was gone before he reached the verbal stage of

his

meditations. The one thing that would have startled him

into speech was the

information that the milk came from real

cows.

The children, and there were a great many children in

Packer’s Rents, affected him differently. Besides wonder he

had an uncomfortable

feeling of responsibility about them

He never could get rid of the idea that

“somebody ought to be

told;” and might often have been seen lifting up a baby

out

of the gutter or stooping to wipe a small nose with his red

pocket-handkerchief. He had come to believe that they were

human children because

Mabel Elsie shamelessly discussed

their incidence with her friend Mrs. Ellis in his

hearing. In

spite of his general haziness he remembered to be glad that he

had

no grandchildren in Packer’s Rents, and frequently said so

aloud, with embarrassing

disregard for Mabel Elsie’s presence.

Mr. Trembath never quarrelled with his daughter-in-law.

She made him wonder, but not more than when fourteen years

ago his son brought her

home with her voice and her clothes

to Rosewithan. Most personal matters, things to

be glad or

sorry about, were so far off now that Mr. Trembath had

ceased to

grieve over the relationship. He sometimes addressed

her as “my dear,” and then

would pull up short with a pathetic

look of non-recognition. Could this be the

woman his son had

chosen for bed and board? The incredible idea caused him to

forget his manners, and, staring at Mabel Elsie, to observe

aloud in a mildly

deprecating voice:

“Well, what a woman, eh?”

Then Mabel Elsie would throw back her head and scream

with laughter.

“Just like the green woodpeckers down to Rosewithan,

my

dear,” he would say, and go on to discuss a matter which

had long troubled his

conscience. Years ago, tempted by the

green and scarlet, he had shot a

woodpecker—here he would

illustrate “and a good shot it was, my

dear”—in the mating

season. The bird had built in one of the elms which

stood

in front of his door, and ever afterwards the round black hole

haunted

him like an empty eye-socket in which he himself had

quenched the fire of life.

Then Mabel Elsie would laugh again

more loudly, whereat Mr. Trembath would shrink

and pain-

fully try to show her how the women laughed down to Rose-

withan. But

Mabel Elsie only called him a “silly ole man”

for his pains.

For Mr. Trembath’s daughter-in-law had a proper sense

of practical benefits, and was not easily wounded. A weak

minded old gentleman

whose only interest in his life annuity

was to sign the quarterly cheques, was

worth indulging in his

conversation. When Mr. Trembath’s only son migrated to

London he acquired habits, including Mabel Elsie, which did

not make for material

prosperity. Love of the land was not

enough to make life worth while to his mother

after he had

left her roof and she presently died, if not of a broken heart,

at least in a moral vacuum. For a time Mr. Trembath tried

to forget his loneliness

in his farm, but dairy farming without

a mistress is a rather forlorn industry. At

last the craven

letters of his son who daily sank lower under the

circum-

stances of his choice, confirmed Mr. Trembath in his disastrous

opinion that he ought to leave Rosewithan to “see what he

could do for John.” So

he came to London, but only in time

to learn that the only thing he could do for

John was to bury

him. Having dropped the lease which his ancestors had held

under the same landlords for six hundred years, Mr. Trembath

remained in London to

look after John’s wife.

Mabel Elsie would have put it the other way, and

indeed,

she was eminently able to take care of herself. She certainly

managed Mr. Trembath’s income. Money so easily come by

was naturally not handled in

a narrow spirit of economy;

hence the friendship of Mrs. Ellis and others; for the

less

recreative consideration of daily bread, as also for appearances,

Mabel

Elsie worked in a box factory. On the fluctuating

margin of these economies, and to

enable him to sign the

quarterly cheques, Mr. Trembath was badly fed, worse

clad,

and allowed to do pretty much as he liked.

What he liked was usually not inconvenient to the

general

disorder of Packer’s Rents. But with the progressive cloud-

ing

of his mind to the immediate present and recent past,

Mr. Trembath’s memories of

Rosewithan became clearer

though less coherently related. This would not have

mattered

if he had been able to indulge his fancies at will, but they were

rather thrust upon him like the gift of prophecy, and you never

knew when a

careless word would set him going. Sometimes,

too, the urgency of his recollections

and his inability to place

them in point of time, drove him to action. He would get

up

very early in the morning and disturb the house looking for

his gaiters, because in the night there had been borne in upon

him the pressing

necessity to cut furze. The spectacle of a

tall, thin old man with a vacant eye

stalking down Tarbuck

Street armed with a furze hook naturally caused people

to

intimate to Mabel Elsie that she ought to take more care of

her

father-in-law in the interests of the general public.

Mr. Trembath also suffered from the obsession of market

day. Packer’s Rents came to spending Thursday between

the doorstep and sharing

pints on the off chance of Mr. Trem-

bath being run in. Greengrocers were apt to

misunderstand

his motives in selecting samples of their wares “to show to

friend Trevorrow,” and he once came perilously near horse-

stealing. Loitering in

the neighbourhood of the “Duke of

York” he recognised his own horse and gig

standing at the

street corner. A clock striking five warned him that it was

time to be driving home to Rosewithan. He crossed the road,

and giving twopence to

the boy who held the horse, patted

him on the head, bade him be a good lad, and was

preparing

to climb into the gig when it’s owner came out of the “Duke

of

York.” This man failed to appreciate Mr. Trembath’s

courteous offer of a lift, and

was for haling him to the police

station. Luckily Bill Ellis was attracted by the

little crowd,

and with difficulty set matters right by explaining that Mr.

Trembath was “a bit barmy.”

Mr. Trembath was indebted to Bill in more ways than

one, for it was through little Elfred Ellis that he came to grips

with his memory,

and made smooth his way to the Rosewithan

of his dreams. As Blondel to the Captive Richard, Elfred

revealed his proper self

by whistling “We wont go home till

morning.” That belonged to Rosewithan sure

enough; how

and why Mr. Trembath could not at first remember. He saw

something

in Elfred’s face which reminded, but with observa-

tion, escaped him. When the

teasing recollection at last found

words Mr. Trembath gripped Elfred by the arm and

said,

somewhat testily for him:—

Yes, yes, that was the tune, but he didn’t whistle it;

he

played it on some sort of instrument; it was a—no” he loosed

his hold and shook his head; “you must excuse me, but I

can’t remember.” Nor did

Mr. Trembath appreciate the ironical

fact that it was John’s perseverance in the

spirit of the song

which brought him to an early grave and himself to Packer’s

Rents.

Elfred for his part was attracted by the old man’s

courtly

gravity so different from anything in Packer’s Rents; the

discovery that, like all men of his native place, Mr. Trembath

could play marbles

cemented their friendship and freshly

vindicated Mabel Elsie’s opinion that her

father-in-law was

“a silly ole man.”

Thus Elfred became a link between the past and the

present. Mr. Trembath talked to him familiarly about Rose-

withan affairs, Sally’s

calf and the relative merits of Tango

and Spot as hunting dogs, and Elfred

remembered; so that

the old man and the little child reached a common ground

in

the forgetfulness of the one, the ignorance of the other of the

distance in time and place. Very naturally it happened one

morning that Mr.

Trembath took Elfred by the hand and pro-

posed that they should go and look for

bull gurnards in the

pullans. Elfred thought they were a long time getting to

the

sea, but kept implicit faith in Mr. Trembath until his aimless

conduct at

a crossing attracted the notice of a policeman.

Then the youngster began to howl

dismally, though it was

from him rather than his elder that the man in blue

discovered

whence they came.

When the two, Elfred still blubbering, appeared at the

corner of Packer’s Rents, Mrs. Ellis was in the act of telling

how much she gave

for Elfred’s button boots to a group of

sympathisers who speculated exactly how

long Bill would get

for bashing her when he learned that his offspring was

missing. It was the sudden change in her voice from woe to

piercing anger which

caused the others to turn their heads. In

a moment Elfred was being shaken to

pieces. Whenever

Mrs. Ellis paused for breath a supporter yelled in the boy’s

ear

what he would get supposing he were her child. Until Mrs.

Ellis in a

dangerously quiet voice reminded all and sundry

that she owned a monopoly in

Elfred. The little group already

cheated of a sensation trailed away sniffing their

sentiments.

Then Mrs. Ellis turned her attention to Mr. Trembath,

who was patiently trying to make out what all the noise was

about. As a result of

her communicated views about himself,

his appearance, his family and his family’s

failings, Mabel

Elsie and Mrs. Ellis did not speak for several weeks, and Mr.

Trembath and Elfred were deprived of each other’s society.

The approach of August Monday however, mended all that.

After five reconciliatory jugs contributing to the decision that

Hampstead and

Greenwich were both played out, Mr. Trem-

bath was told that if he “kep out of

mischief and didn’t cause

no more rows” he should be taken to the Crystal

Palace.

Mr. Trembath was moved, but with an emotion more pressing

than

gratitude.

“Yes, my dear,” he said, nodding. “Now I’ll tell you

about that. If you’ll look upon the left hand side of the cove

just above the

boulders you’ll see a square block of granite all

finished off beautifully. That

was made for the pedestal of an

obelisk or monument, if you will, weighing eighteen

tons and

taken out of the Rosewithan Quarry to be sent to the Great

Exhibition

of ‘5i. The obelisk was sent, but the pedestal

never followed because old Cap’n

Hosken who leased the

quarry went scat.”

Oh, chuck it!” cried Mabel Elsie. “Who wants to

hear

your mouldy stories.”

But my dear,” said Mr. Trembath patiently, “this is

important, because it was the only time I ever went to law

with any man. Cap’n

Hosken had hired horses of me, and

seeing that his affairs were in the Court I

thought it only just

to put forward my claim. They awarded me—”

“For Gawd’s sake,” said Mabel Elsie in desperation, “go

along to the corner for a quart and don’t muddle your silly ole

‘ead with drinking

out of the jug.”

This was Mabel Elsie favourite joke, and invariably

recalled her father-in-law to his dignity.

You know, my dear,” he said, “we are all Rechabites

down to Rosewithan and don’t belong to touch anything except

perhaps a little sloe

or blackberry wine hot and with sugar, at

Christmas time. That is good for the

system and cheerful as

well.”

Mr. Trembath was infected with the excitement of August

Monday, though he had a very hazy notion of what was going

forward. Long before

Mabel Elsie had finished curling her

hair he had shaved and brushed his clothes,

and stood in

everybody’s way consulting his watch. Though he did not

realise

that he paid the score, he still was persuaded that he

was in command of the party.

Bill Ellis good humouredly

undertook to keep the old man out of mischief, leaving

his wife

and Mabel Elsie free to celebrate or to quarrel as their fancy

led

them. Bill, who perfectly recognised the distance between

himself and Mr. Trembath,

regarded him vaguely as a thing

which might be broken he always addressed him as

“Sir,”

and with the extraordinary gestures and grimaces which every

Englishman

knows are necessary to reach the intelligence of

the foreigner.

Mr. Trembath caused some trouble in the train by

insist-

ing that they had passed Exeter and must presently come to

the

sea; but on the whole behaved tolerably well. At the

Palace, however, he became a

nuisance. Misled by certain

objects he remembered, or thought he remembered, from

’51 he

wanted to act as showman, though, as Mabel Elsie said, she

had’nt come to see

things or to be preached to, but to enjoy

herself, which apparently meant laughing

very loud without

visible reason, and taking varied refreshments with the

still

more varied acquaintances of half an hour. Bill Ellis as a

distinct

personality grew vaguer and vaguer, and finally was

absorbed into a beery crowd. To

the relief of the women

Mr. Trembath actually did find the obelisk and asked

nothing

better than to be left beside it. Here he sat with the pathetic

air of

an unaccustomed traveller clinging to his luggage, but

with something of

proprietorship as well. Quite a number of

people were interested in the dignified

old man, and went away

persuaded that he was an unusually affable official told off

for

the special convenience of visitors.

Sitting half asleep under the great stone Mr. Trembath

dreamed vivid but incoherent pictures of the valley when, with

a jerk, they fell

into relation like the pieces of glass in a

kaleidoscope. Somewhere out of sight

someone was haltingly

playing a familiar air as if of the upper notes of a

harmonium.

It was the one emotional touch wanting, bringing everything

into

focus, yet Mr. Trembath could not place the sound either

in time or character. It

was familiar, yet so familiar that he

felt he had not taken due note of it at the

time, as a man may

be at a loss when suddenly asked the colour of his friend’s

eyes. Then other noises intervened, and the painfully groped

for memory was lost.

Yet the germ of it must have remained,

for in the brutal rush for the station,

something glittering on a

stall caught Mr. Trembath’s eye. He hesitated, felt in his

pocket, but was swept

away. Bill Ellis, who had emerged

from the crowd morally and physically the least

happy version

of himself, was clamouring for a policeman; not, as he

care-

fully explained, because he bore any ill-will to the force, but

because

he felt an urgent desire to confide in one particular

member, and resented his

absence.

During the journey home Mr. Trembath was quiet, but

with so shining a face that Mabel Elsie and Mrs. Ellis

exchanged uneasy glances,

and the former cautiously questioned

him:

“Well, father, enjoyed yourself?”

His answer, all about heather, was not illuminating,

and

Mabel Elsie cut him short with “Garn you silly ‘ole man” in

a tone

of great relief.

Mr. Trembath had found out what he wanted, and with

a

definite need he grew very cunning. Mabel Elsie held that

he was not fit to be

trusted with pocket money, and his oppor-

tunity seemed a long while coming, but one

Saturday evening

he found sixpence on the corner of the dresser. Too

instinct-

ively honest to justify himself with the argument that it was

his own

money, he pounced upon it without hesitation. A

theft so artless was certain to be

discovered, but Mabel Elsie

forgot her anger before this glaring vindication of her

apparent

harshness. She made the most of her opportunity, and called

in

witnesses to prove that nobody but Mr. Trembath had

access to the coin, but for

once the old man turned stubborn.

Though he did not deny the accusation he would neither pro-

duce the sixpence, nor

say what he had done with it. It was

a fine moment for his daughter-in-law, and won

her floods of

sympathy.

She soon had genuine cause for anxiety, for Mr.

Trem-

bath’s health began rapidly to decline. He seemed very con-

tented,

but kept his own room and refused society. As Mabel

Elsie confided to Mrs. Ellis

over a quart of bitter, he could not

live for ever, and with him the annuity ended.

Not that she

minded that, for she was prepared to swear before any Court

in

the land that she never saved a penny out of her father-in-

law—which was

perfectly true—let alone his pilfering habits;

but there was the funeral to

be considered. If Mr. Trembath

died between two quarter days, when the one cheque

was well

disposed of on his behalf, the next would never be paid. That

she

understood, was the iniquitous rule; and she left it to

Mrs. Ellis’ judgment how

awkward it would be for her to have

to bury him at her own expense.

“Thenks; if its me you’re meaning,” said Mrs. Ellis

bitterly; “I’m sure I’ve no wish to be beholden to anybody

for

what the Doctor orders me; and I’m not one to be over fond

of a glass but

the spirit in which it is offered, Misses Trim-

bath.” Mabel Elsie hastened to

assure her, to the extent of

another jug, that nothing of the sort was implied, but

that she

trusted she knew her duty better than to allow Packer’s Rents

an

opening for criticism when her father-in-law was taken.

Ultimately Mrs. Ellis was

dissolved to a correct appreciation

of Mabel Elsie’s grievance.

“The mean ole scut to go and take to ‘is bed after all

you

done for ‘im,” she said, and assured her hostess that let her

hear

any nasty talk among the neighbours she would have a

word to say in the matter.

With the dismal foresight of their class the neighbours

discussed Mr. Trembath’s death as a fact accomplished.

Packer’s Rents was not

superstitious, but the presence of a

man who already might be considered dead

aroused a morbid

interest which presently became whispering.

There were the noises. One hinted, another swore that

while Mabel Elsie was at the box factory things went on in

number seventeen which

could not be explained on any human

grounds. Mrs. McGrath was frankly of the

opinion that

Mr. Trembath had celestial visions, and announced her fervent

desire to visit his chamber on behalf of her daughter three

years in Purgatory. For

some time consideration for Mabel

Elsie kept the whispering under a forcing pot, as

it were; until

the tales engendered were too horrible, and heads began to

shake. Finally Mrs. Ellis out with it and declared that while

she had a tongue in

her head no neighbour of hers should have

her character taken away, and tearfully

made her way to

Mabel Elsie’s door. Mabel Elsie took it the wrong way.

A pack of scandal mongering hussies. Hadn’t her

father-

in-law all that a man could want, and didn’t she hope she

might

drop dead where she stood if she had ever touched a

penny of his dirty money beyond

what was her lawful due from

a troublesome lodger? Father-in-law or no father-in-law, she

should like to know

which among them would have refrained

from prosecuting when the very change out of

their Saturday’s

shopping was stolen from the dresser? It was time folks

looked nearer home, and talking of that, how could Mrs. Ellis

afford a new sofa out

of Bill’s wages and him always at the

corner?

“And I’m sure I never breathed a word,” panted Mrs.

Ellis, “and if you ask me its more a matter for the parson

than the police”; and a

sympathetic murmur went up about

the judgment of God. All this took place in the

passage down

stairs, and in the midst of it came a thin sound from Mr.

Trembath’s bedroom. The women drew together; but all

agreed that though they were

sorry for Mabel Elsie it couldn’t

have happened at a better moment. Mabel Elsie’s

jaw dropped,

and she turned white and red.

One suggested that it was like a child singing, though

Mrs. McGrath, as the mother of seven, firmly asserted that no

earthly babe could

make a noise like that. She was for going

upstairs, but Bill Ellis happened to come

in the nick of time.

“W’y its a ‘cordian!” he cried. “Listen, the ole

juggins

is tryin’ to play ‘We wont go ‘ome till mornin”;” and with

uplifted finger he hoarsely sang the words. Some time was

wasted in argument, and

the sound brokenly ended. At last

Bill took his courage in both hands, and with a

great deal of

unnecessary noise ascended the stairs. But when he reached

Mr.

Trembath’s room he found the grey man lying dead,

clasping in his hand a sixpenny mouth organ. From his

peaceful expression it may

be surmised that the morning had

come.

CHARLES MARRIOTT.

TO ANY HOUSEHOLDER.

Some general instinct has remained with men, so that

the

consensus of nations has been in favour of light

colours—light

tones, rather, of whatever colours—for the outward

colouring

of towns; with some lamentable exceptions. As a rule it has

been

accident, and not design, that has darkened the exterior

of modern houses; we have

in London the darkest walls that

ever rebuffed the sun. It is the water-colour of

the rain, with

soot in her colour-box, and no fresco of man’s preparation,

that has arrayed them so. The washing of the exterior of

St. Paul’s would have been

a better enterprise than the applica-

tions we know of within. But, short of this

supreme degree

of darkness, London had some time ago the unlucky inspiration

to paint its houses, all about the West, in oil-colour of dark

red. It was the

complaint of the silk-stockinged century that

the pedestrian must needs fare ill in

town, for the same mud

made black splashes on the white stockings, and white

splashes on the black. In like manner the London climate

that painted the light

stone black, made the dark red (a most

intolerable colour) a shade or two lighter

with dust in time;

after which some of the painted houses were reloaded with

the

red, and the owners of others had misgivings, and went back

to the sticky

white of custom.

The sticky white is bad enough, but it is witness to

the

general acknowledgment of the prohibition of dark colour,

whether

on our luckless walls of paint, or on the flattered,

fortunate plaster of the south

that softly lodges the warming

day, and has its colour broken by the weather as an

artist

chooses to let a tint be effaced or an outline lapse. There is

no surer

distinction between an old Italian coloured house and

a new than this: the new is

dark and the old is pale. True,

the new is coloured ill as well as darkly, and the

old coloured

finely (always warmly with variants of rose and yellow) as

well

as lightly; but the deep tone and the high are difference

enough. The new man

choses chocolate-colour and dark

blue; blue is his preference, and his blue jars

with the sky.

The ancient man so used his beautiful distemper that it

always looked not merely like a colour, but like a white

coloured. The old

under-white enlivens the thin and careless

colour, somewhat like the soft flame of

a lamp by day within

a coloured paper. Moreover, the painter did his large and

slight work on a simple wall, and not on the detail of cornice

or portal. His

colour took no account of the architectural

forms; it was arbitrary, a decoration

that neither followed nor

contradicted the builder’s design, but stood independent

thereof,

merely taking the limit of the wall as the boundary of the paint-

ing.

Here again all the right guidance has forsaken the man

of to-day, who takes the

mouldings of his house one by one,

and gives them separate colours.

Needless to say, the original colour of the stone is better

even than this happy plaster, when there

is real colour in

stone, greyish, greenish, yellowish, the natural metallic

stain.

It is all light in tone; nothing darker, I suppose, than the

brown of

the stone that built the Florentine palaces, and all

else lighter. The quarry

yields light colours in all countries,

colours as pale as dust, but brighter in

their paleness, with the

greater keenness and freshness of the rock. But the

nobler

old stone has a kind of life in its colour, as though you could

see

some little way into it, as into a fruit or a child’s flesh.

Such is the old

marble, but not the new.

We may suppose that it was because they had new marble

and not old, as we understand old age for marble, that the

Greeks were obliged to

colour their temples. It is with some-

thing like dismay that we look where Ruskin

points, at

“temples whose azure and purple once flamed above the

Grecian

promontories.” Were they azure indeed? It seems

impossible to set any blue against

a sky. Nay, the sky forbids

blue walls. Be they dark or light, they must either

repeat the

celestial blue, or vary from it with an almost sickening effect.

Who has not seen a blue Italian sky, blue as it is at midsummer

right down to the

horizon, at odds with a great blue house,

either a little greener or a little more

violet than itself? Blue is a

colour that cannot bear such risks. And “purple”

sounds dark,

as though Greece might have had to endure a distress of colour

such as that which comes of the thin dark slates of purple where-

with our suburbs

are roofed. If one could be justified, by any

trace of colour in any chink, in

believing that transparent

yellow and red, lighted by the marble,

glowed upon those

seaward heights and capes towards the sunrise, and that the

noble stone was not quenched by azure and purple paint! Why

then there would not be

this discomfort in our thoughts of

Grecian colour. Of some among the boldly and

delicately-

tinted old palaces of the Genoese coast you can hardly tell,

at

the hour of sunset, whether their rose is their own or the light’s.

To the Londoner eye of Charles Dickens there seems to

have been something gaily incongruous in a fortress house

with walls centuries old,

and barred with ancient iron across

the lower windows, yet thus softly coloured; he

expressed

the cheerful liberal ignorance in which he travelled by calling

one

such palace a pink gaol; but this old faint scarlet is a

strong colour as well as a

soft; and above all it is warm.

A cold colour, and no other, suggests meanness,

insecurity,

and indignity. Colour the battering walls of Monte Cassino,

now

warm with the hue of their stone, a harsh blue, and their

visible power is gone;

whereas no daubing with orange or

rose, however it might disfigure them, would make

them seem

to fail. But a dark colour of any kind, whether hot or cold,

would

make them visibly lose their profound hold on their

rock, and their long,

searching, and ancient union with their

mountain.

This is what the householder should be persuaded to

consider—the harshness and weakness of the dark colour, the

harmony and

strength of that which is rather a white warmly

coloured. Any householder is master of a

landscape, and the

view is at his mercy. Everything may be set out of order by

the hard colour and the paper thinness of his slate roof. See

the dull country that

the Channel divides, half of it on the

Dover heights, and half on those of the Pas

de Calais. It is

all one dull country. It has not the beauty of downs, nor of

pasture; it has neither trees nor a beautiful bareness; it has

no dignity in the

outlines of the hills; but the French side has

the beauty of roofs, and the English

side makes the very

sunshine unsightly with towns and villages covered with

slate. All the French roofs are light in their tone, silver greys,

greenish greys

in the towns, a pure high scarlet in the solitary

farms. This kind of French tile

retrieves all the poor land-

scape of patchwork fields, green and dull in their

unshadowed

noons. The red is strong, simple, and abrupt, a vermilion

filled

with yellow.

It is true that old village tiles are fine, although they

be

dark, but only on condition that the cottages they roof should

be

whitewashed or of a cheerful brick. There is brick and

brick, and all the very

light colours are good. Light rosy

bricks and very small, long in shape, seem the

most charming,

and these are rare. Next come the coarse but admirable light

yellow-red. But any man who builds a house of dark bricks

inclining to purple and

pointed with slate colonr, would have

done better to erect something in stucco with

pillars and a

portico. All kinds of red villas continue to crowd upon our

sight, and it is to be feared that many a purchaser is afraid

that he shall be reproached with the

crudity or the brightness

of his house, and so makes the lamentable choice of

dark

bricks. But there is nothing more unreasonable than this

perpetual

complaint of the newness of new houses. Let the

owner of a new house have the

courage of his date. Let him

be persuaded that a new house ought to look new, that

the

Middle Ages in their day looked as new and tight as a box of

well-made

toys, that he is bound to pay the debt of his own

time, and that the light of the

sky asks for recognition, for

signals and conspicuous replies from the dwellings of

men.

Let the mere white-washer, too, whose work is generally

beneficent, and who has received undeserved reproaches for a

long time now, let him

beware of chillling his pail with blue

tinges. The coastguard huts on the Cornish

coast would be

the better if their common touch of blue were forbidden them.

All this advice is, I know well, inexpert, and backed by

no

learning. But it is urged with care and with comparison of

countries

by one who, in search of roofs and intent upon

colours, has, in the remarkable

words of Walt Whitman,

“journeyed considerable.”

ALICE MEYNELL.

THE ORACLE.

‘Tis mute, the word they went to hear on high Dodona

mountain

When winds were in the oakenshaws, and all the cauldrons

tolled,

And mute’s the midland navel-stone beside the singing fountian,

And echoes list to silence now where gods told lies of old.

I took my question to the shrine that has not ceased from

speaking,

The heart within, that tells the truth and tells it twice as

plain;

And from the cave of oracles I heard the priestess shrieking

That she and I should surely die and never live again.

O priestess, what you cry is clear, and sound good sense I

think it,

But let the screaming echoes rest and froth your mouth

no more;

‘Tis true there’s better boose than brine, but he that drowns

must drink it;

And oh, my lass, the news is news that men have heard

before.

The King with half the East at heel is marched from lands of

morning,

Their fighters drink the rivers up, their shafts benight

the air;

And he that stands will die for naught, and home there’s no

returning.

The Spartans on the sea-wet rock sat down and combed

their hair.

A. E. HOUSMAN.

THE GENIUS OF POPE.

It can be easily shown that although the Restoration

inaugurated in England an age of prose, yet the position of

poetry as the chief and

natural medium for pure literature was

still accepted almost without question. For

that reason Pope

was taken in his own day to be the undisputed head and front

of

English letters. His contemporaries probably felt, as we feel,

that Swift’s

was immeasurably the greater genius; but they

held, and held rightly, that Pope in

his work was the true

representative of what has come to be called the

Augustan

literature. The two works in prose dating from that period

which have

sunk deepest into the mind of the race—Robinson

Crusoe and Gulliver’s Travels—were written by

men who

stood outside the main literary movement; for Defoe never at

any time

attained a place in the great literary coterie of which

Swift, while he kept in

touch with England, was a brilliant

member; and Swift wrote Gulliver when lonely and rebel-

lious in Ireland, thinking his own

thoughts. Now the

distinctive characteristic of the Augustan literature is

that

we have no longer in a book the mind of an individual, but

the mind of a

Society finding expression through the

mouth of one of its members. It was a

natural result of that

intellectual ascendency of France, which at this time made

itself so strongly

felt; for the Frenchman is always social

rather than individualist; and, at least

in criticism, men had

come to take their beliefs from France.

The cardinal point in these beliefs was that literature

admitted of rules, which had been first formulated by Aristotle,

after him by

Horace, and finally by Boileau; and consequently,

that the first duty of a writer

was to be correct; to conform

in poetry not only to the laws of grammar and of

rhyme, but

to certain other canons of taste hardly less definite. It is true

that Milton, in no way touched by French ideas, attached

importance to the

Aristotelian criticism, and that in his Samson

he worked

on a Greek model. But then Milton knew Greek

a great deal better than Pope knew any

language but his own.

In nothing is Pope more typical of his school than in

constant

lip-homage to the ancients whom he had never read. He trans-

lated

Homer, it is true, but he founded his rendering mainly on

other versions; he knew

Virgil somewhat, but was evidently

deaf and blind to the note of lyricism which

pervades Virgil as

it pervades the work of all great poets. What he did know

was Horace; but all that he saw in Horace was the admirable

expression of a

sententious philosophy, the work of a “great

wit.” The word “wit” recurs

perpetually in Pope’s writings;

it represents the goal of his ambitions; and he has

defined it

in a characteristic couplet:

True wit is nature to advantage

dressed:

What oft was thought, but ne’er so well

expressed.

But the function of a poet is not to separate and crystallise

into compactness the

common thought; it is rather to link it

to infinities of association, to send it

out trailing clouds of

glory; to show the “primrose by the river brim” or the

“flower in the crannied wall” as a single expression of forces

making for beauty

that sweep through the cosmos. Shake-

speare abounds in sententious utterance; for

instance:

We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little

life

Is rounded with a sleep.

But here, apart from the large harmony of sound, apart from

the intrinsic beauty

of the words, is their dramatic fitness in

Prospero’s mouth, when his fairy masque

fades suddenly, and

he evokes the solemn images of all that we take to be

least

dreamlike, ending with “the great globe itself, yea all that it

inherit.” We cannot separate his aphorism and feel that we

can see all around it,

as we can with any characteristic utter-

ance of Pope’s, such as:

What can ennoble sots or fools or

cowards?

Alas! not all the blood of all the

Howards.

If one can assert anything positively in criticism, it is

that

Pope’s ideal of poetry is unpoetic. But it does not follow that

Pope was not a poet. That he was a great writer no one will

deny. The disservice

which Pope did to English literature

—and it has been much

exaggerated—is that he used his

authority to formulate as possessing

universal validity the

rules which it suited his own genius to observe. His

first

study was to be “correct;” to make the expression of his

thought sharply defined

in form, and completely intelligible; to

exhaust in each phrase the content of his

own meaning. Now,

this is much easier to do if the thought is limited in

volume,

and Pope was never troubled with more thought than he could

express.

The words of the great poets came to us charged

with suggestion; they convey more

than they utter. Pope

also can suggest, can hint by innuendo; but the innuendo

is

definite as the voice of scandal—as here:

Not louder shrieks to threat’ning heaven are

cast

When husbands or when lapdogs breathe their

last.

But he is never, at his best, able to do more than give perfect

expression to a

brilliant observation, so concise and logical,

that it would seem to admit

perfectly of translation into any

language, losing nothing but the clench of rhyme;

though here

and there some individual colour given to a word might baffle

rendering:

Narcissa’s nature, tolerably

mild,

To make a wash, would hardly stew a

child.

Yet it sometimes happens that the master of prose can

beat him on his own ground. “Who are the critics?” says

Mr. Phoebus in Lord

Beaconsfield’s Lothalt, “The critics

are those who have

failed in literature or in art.” That is

happier than Pope’s lines:

Some are bewildered in the maze of

schools,

And some made coxcombs nature meant but

fools.

In search of wit these lose their common

sense,

And then turn critics in their own

defence.

It is seldom, however, that Pope can be excelled in

con-

densation and the happy turn of a phrase. His workmanship

everywhere approaches perfection. The inherent weakness of

his poetry is, as Mark

Pattison has pointed out, that the

workmanship often outvalues the matter; that our

admiration

is compelled for the expression of a mean sentiment, a half-

truth,

or an ignorant fallacy. To his mastery of style Pope

united no store of knowledge,

no wide and lofty range of feel-

ing. When his matter is intrinsically valuable

apart from

expression it consists in reflections upon the human life with

which he was in contact socially. He is the poet of Society,

and his observation,

if acute, is often petty and malicious to a

degree that spoils our pleasure in his

triumphant mastery of

language.

Yet if ever a man had a right to clement consideration,

Pope was he. Externally, circumstances were kind to him.

Born in 1688, the son of

rich and kindly parents, he was stinted

for nothing; his amazing precocity was in

all ways encouraged.

The Pastorals, which he published

at the age of twenty-one

(though much of them was written in boyhood), earned

applause, and two years later his Essay on Criticism fixed

his

fame, and brought him into close personal relations with the

leaders of

taste. But to offset all this was the abiding misery

of his physical disabilities.

Dwarfish and deformed, he went

through life in “one long disease.” The stigma which

de-

formity sets on a face in hard drawn lines of pain is often an

evidence of

tense intellectual power and resolute will; but it

often also indicates dangerous temper. Pope had much of the

dwarf’s traditional

malice and long-minded resentment. His

life was a long triumph, unaffected by

political changes (for

he stood outside of parties); but it was marred by the

temper which made him see hostility where none existed, and

poisoned every scratch

of criticism; so that the most famous

things in his work are bound up with the

memory of literary

feuds. Yet he inspired deep friendship. No letters in the

world show a warmer feeling of one man for another than

those which Swift wrote to

him and about him.

Pope was best known in his own day by his translation

of Homer—the most profitable book, financially, to its author

that had ever

been published in England. His most pretentious

work, the Essay

on Man, abounds in much-quoted distichs and

is singularly barren of real

thought. Those poems of Pope

which the average reader to-day is likely to enjoy are

first, the

Essay on Criticism; secondly, the Rape of

the Lock; and

thirdly, the Moral Essays. To

these may be added some

superb passages in The

Dunciad.

The Essay on Criticism will always please by sheer

cleverness, and nothing could exceed it as a formal expiration

of that age’s

aesthetic tenets. But its arrangement into

headings and sub-headings like the model

prize essay is too

obvious, and even its cleverness is the precocious talent

of

immaturity.

Pope was never young. Yet something of the glow of

youth is to be found in his exquisite Rape of the Lock

(written at the age of twenty-four) which

can be best

compared to one of those Fetes Galantes in

which Watteau

depicts a group of fine ladies and gentlemen taking their

pleasure, and depicts it with a rich mastery of style which

gives a dignity to the

slight and artificial subject. The

comparison, however, is inadequate, for

throughout Pope’s

description, even while it conveys the very flutter of a

fan,

there runs an undertone of trenchant raillery. Here is

Belinda at her

first arising on the fatal day:

And now, unveiled, the

toilet stands displayed,

Each silver vase in mystic

order Laid.

First, robed in white, the

nymph intent adores,

With head uncovered, the

cosmetic powers.

A heavenly image in the

glass appears,

To that she bends, to that

her eyes she rears;

The inferior priestess, at

her altar’s side,

Trembling begins the sacred

rites of pride.

Unnumbered treasures ope at

once, and here

The various offerings of the

world appear;

From each she nicely culls

with curious toil,

And decks the goddess with

the glittering spoil.

This casket India’s glowing

gems unlocks,

And all Arabia breathes from

yonder box.

The tortoise here and

elephant unite,

Transformed to combs, the

speckled, and the white,

Here files of pins extend

their shining rows,

Puffs, powders, patches,

Bibles, billet-doux.

Now awful beauty puts on all

its arms;

The fair each moment rises

in her charms,

Repairs her smiles, awakens

every grace,

And calls forth all the

wonders of her face;

Sees by degrees a purer

blush arise,

And keener lightnings

quicken in her eyes.

The busy sylphs surround

their darling care,

These set the head, and

those divide the hair,

Some fold the sleeve, whilst

others plait the gown;

And Betty’s praised for

labours not her own.

For ten years (1715-1725) after the Rape of the

Lock,

Pope was busy with his great work of translation; and

during all

these years he accumulated grudges against men who had

vexed him by

criticism a successful rivalry. Once his hands

were free, he turned to a sweeping

revenge, and, after three

years polishing published The

Dunciad, perhaps the greatest

monument that a man ever erected to his

petty personal resent-

ment. It is characteristic of him, both as artist and man,

that

he was not content with the first publication, but issued a

revised

version twelve years later, when Colley Cibber, dis-

placing Theobalds on the throne

of Dulness, showed for a

second time that Pope’s notion of the arch-dunce was a

potential

rival. But most of his victims, competitors in the trial games

instituted by the presiding goddess of Stupidity, are only

remembered by his

allusions; the work cannot be read with-

out detailed commentary; and, like all

satires applied to trivial

dislikes and insignificant persons, the Dunciad has passed out

of general knowledge. Yet it abounds

in superb passages, of

which one may be cited, describing a new labour of the

com-

petitors after the trial by braying:

This labour passed, by

Bridewell all descend,

(As morning prayer and

flagellation end)

To where Fleet-ditch with

disemboguing streams

Rolls the large tribute of

dead dogs to Thames,

The king of dykes! than whom

no sluice of mud

With deeper sable blots the

silver flood.

“Here strip, my children

here at once leap in,

Here prove who best can

dash through thick and thin,

And who the most in love of

dirt excel,

Or dark dexterity of groping

well.”

But the mere technical mastery in expressing unworthy

hatred gives no man a long lease of posterity’s ear. Pope

survives as a satirist by

those Moral Essays (couched in the

form of Epistles to

persons of distinction) which deal with

particular examples of general themes. Here

is a part of the

passage in which he illustrates the persistence of a ruling

passion:

“Odious! in woollen 1

‘twould a saint provoke,”

(Were the last words that

poor Narcissa spoke)

“No, let a charming chintz,

and Brussels lace

Wrap my cold limbs and shade

my lifeless face:

One would not, sure, be

frightful when one’s dead—

And—Betty—give this cheek a

little red.”

Here again from the essay on the characters of women, is a

sketch of what many

take to be a type known only to-day:

Flavia’s a wit, has too

much sense to pray

To toast our wants and

wishes, is her way;

Nor asks of God, but of her

stars, to give

The mighty blessing, “while

we live to live.”

Then all for death, that

opiate of the soul!

Lucretia’s dagger,

Rosamonda’s bowl.

Say, what can cause such

impotence of mind?

A spark too fickle, or a

spouse too kind?

Wise wretch! with pleasures

too refined to please;

With too much spirit to be

e’er at ease;

With too much quickness ever

to be taught;

With too much thinking to

have common thought:

You purchase pain with all

that joy can give,

And die of nothing but a

rage to live.

There is no end to things in Pope as good and as

quotable,

and, perhaps one may say, as little known. What everybody

does know is the portrait which he drew of “Atticus,” and

published when Addison

was dead.

It is worth while to compare this with Dryden’s sketch

of Shaftesbury. Achitophel’s ill qualities as statesman are first

depicted with

damning emphasis; but, as a real offset there

follows the passage that praises the

upright judge. Pope, on

the other hand, leads off with his eulogy, saying of

Addison

what all the world said, and saying it better: then after this

ostentation of impartiality comes the subtle onslaught, stab

upon stab, with the

venom of contemptuous ridicule left in

every wound. The passage has been taken, and

rightly, for

Pope’s most typical achievement in poetry: beside it we can put

nothing from him but the fiercer attack on Sporus (Lord

Hervey), or the close of

the Dunciad which celebrates the final

triumph of the

Dull. These are the things of which we feel

that verse is an essential part; that

emotion so vibrant demands

metrical expression. Such other passages as the eulogy

of

“The Man of Ross,” a Welsh philanthropist, need the verse,—

form in another

sense; without it they would be insignificant.

But Pope’s poetry, where it has the

character of true poetry, is

always the utterance of a strong passion—the

passion of hate.

And herein he differs from many other satirists, but above

all

from the greatest of all British satirists, his friend Swift,

in that his

hatred was not for principles but for persons; not

for man or men, but this or that

individual. Literary and

social jealousy is the strongest of all his feelings. All

the

more wonderful is it that the friendship between him and Swift

should have

lasted out life in both, though tried by so severe

a test as collaboration and

partnership. But the credit of this

belongs, I think, not to Pope.

STEPHEN GWYNN.

POOR LITTLE MRS. VILLIERS.

“Where is little Mrs. Villiers” demanded Miss Hooley.

The

question was prefaced by a disconcerting gaze directed

towards the new-comer in the

seat opposite—a seat presumably

occupied as a rule by the lady of the

diminutive.

Mrs. Lawrence concealed a smile. Though her school-

days were

now somewhat dim memories, she felt distinctly

like the new girl who is expected to

apologize for her existence.

Glancing down the long table she was aware that a

pension

bore a ghastly resemblance to a

boarding-school, twenty years

after. Was “little Mrs. Villiers” the popular girl,

she

wondered? And if so, on what grounds?

“She’s changed her place,” volunteered Miss Pembridge,

a

spare lady, who dressed with the chastened smartness of one

ever mindful of her

high calling as the niece of a bishop.

“Oh! I’m so sorry. She will be a great

loss to our table,

dear little thing,” exclaimed Miss Mullins. She delivered

the

remark, amiable in substance, with the air of one hurling a

bomb-shell,

and Mrs. Lawrence awaited the explosion of the

apparently harmless missile with

some curiosity, Its effect

was almost instantaneous.

“That’s entirely a matter of opinion,” ejaculated Miss

Rigg,

her opposite neighbour. The observation was attended

by a prolonged sniff, and Miss

Mullins’ comfortable fat face

slowly crimsoned with indignation. While she meditated a

sufficiently crushing

retort, her opportunity for making it was

cut short by the first speaker.

“Where’s she going to sit then?” enquired Miss Hooley,

refusing macaroni with the air of one wearied with an oft

repeated performance.

“There, of course,” returned Miss Rigg, sniffing again, as

she nodded in the direction of a small table near the wall.

At the table indicated a young man was already seated.

His

shamefaced manner of glancing about the room while he

eat his soup, not only

proclaimed him a fresh arrival, but one

somewhat overwhelmed by the eternal

feminine.

“That’s too bad of you,” stammered Miss Mullins.

“Poor little

thing!—under the circumstances too.”

“The very circumstances you’d expect it under,” returned

Miss

Rigg, with an acrimony as obvious as her sentence was

obscure.”

“I agree with Miss Mullins entirely. Potatoes raw

again,”

exclaimed Miss Hooley.

During the course of the dinner, Mrs. Lawrence learnt to

disentangle this lady’s ejaculations about the food, from the

main trend of her

conversation, but the effect was at first con-

fusing.

“She’s very late,” ventured Miss Pembridge diluting with

filtered water the dangerous strength of her vin

ordinaire,

“Got to dress up for the occasion of course,” was Miss

Rigg’s

instant explanatinon. “Ah! here she comes, at last.

Now you’ll see whether I’m right!”

Mrs. Lawrence looked up with interest as the door opened,

and

noticed that “little Mrs. Villiers” was not only very pretty

but also singlarly

childish in appearance.

Her hair—soft brown fluffy hair, hung in baby tendrils

on

her forehead and round her little ears, and her wide opened blue

eyes had

the wondering half startled child-look so touching in

baby faces. She was very

simply dressed in white muslin,

and a row of pink corals round her throat,

emphasised her

youth, and the charming innocence of her expression. At the

door she paused a moment, with an air of hesitation, and a

surprised glance to find

all the seats at the long table occupied.

Guiseppe, the waiter, darted forward. “Madame is placed

at

the little table to-night,” he explained, leading the way.

“Oh! is my place changed then?” she murmured,

following.

“Very much surprised, no doubt,”

ejaculated the irrepres-

sible Miss Rigg in a triumphant undertone.

“If there’s anything I despise it’s a spiteful mind. Boiled

beef again,” said Miss Hooley in something that was intended

for a whisper.

Mrs. Lawrence, meanwhile, watched with some curiosity

the

effect produced upon the grave young man across the room,

by the sudden appearance

of youth and beauty at his lonely

table. He reddened visibly; moved forks and

spoons about

with nervous hesitation, and kept his eyes fixed upon the rim

of

his plate.

Little Mrs. Villiers studied the menu,

and Mrs. Lawrence

was recalled to a sense of social duty by a remark from her

too

long neglected left hand neighbour.

Glancing at the small table at a later stage in the dinner,

she was amused to see the young people chattering like a

couple of children. Now

that the boy had lost his awkward

shyness, she thought him a somewhat engaging

youth, frank,