XML PDF

General Introduction to The Venture:

An Annual of Art and Literature (1903-1905)

The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature may be unique as a little magazine brought out by an art dealer. The New Zealand-born artist and London-based gallery owner John Baillie (1868-1926) opened his Art Gallery in Bayswater from his home at 1 Princes Terrace, Hereford Road, in 1902. The press soon hailed its exhibitions as “the most artistic in town” and advised art-lovers that “the little pilgrimage to Mr. Baillie’s Gallery…is thoroughly worth making” (“What the Press Says,” [vi]). Baillie quickly developed a reputation as an alternative curator whose exhibitions featured non-realist art, artisanal printmaking, and “Neglected Artists”—including Australasian colonials, gays, and women. These curatorial preferences map onto Baillie’s editorial selections for his new magazine, dubbed The Venture to signal the risk and uncertainty he must have felt in becoming a London publisher only a year after opening his gallery. “The enterprising John Baillie” (Mackle 62) was clearly energetic and innovative. Baillie seems to have conceptualized the annual, in part at least, as a kind of advertising vehicle for his showroom and its unconventional artists—in effect, as a portable art gallery. The promotion went both ways, however. Announcing that The Venture was “Now Ready,” an exhibition catalogue in late 1903 urged gallery visitors to “Make it a Success by Ordering a Copy” (Some Woodcuts, [viii]). In the magazine’s advertising supplement, “John Baillie request[ed] Readers of the Venture to honour his Gallery by a visit” (“The Gallery,” [vi]). Responding to the impressive list of contents published in advance notices in September, the Athenaeum critic observed that “‘The Venture’ seems already to belie its name by its promise of success” (“Literary Gossip,” 351).

Aiming to capitalize on the Victorian tradition of buying illustrated gift books and annuals during the holiday season, Baillie brought out The Venture in late November two years in a row. The novice publisher’s timing was a little off, however, as gift books were typically published in early October to take maximum advantage of the Christmas and New Year’s markets. Baillie’s inexperience is also evident in the dating of his annual’s two volumes. Victorian publishing practice was to forward-date seasonal gift books so that they could be reviewed and marketed as new titles two years running. By dating Volume 1 of The Venture 1903, Baillie effectively made it appear outmoded by the time the reviews came out in the new year. He attempted to correct this misstep by dating the second volume 1905 and re-naming the first number “The Venture, 1904” in the magazine’s advertising supplement. Baillie’s creative treatment of metadata has confused bibliographers, who have consequently understood the annual to have skipped a year in its serialization. In fact, The Venture’s two volumes came out within twelve months of each other.

Although he did not give himself title-page credit for this role, Baillie acted as art editor as well as publisher for The Venture (“Literary Gossip,” 351). In this capacity, Baillie was able to correlate the Gallery’s exhibitions and the magazine’s visual contents. For example, in spring 1903, Baillie had a show of drawings by Laurence Housman (1865-1959), with wood engravings by Louise Glazier (1870-1917) and Clemence Housman (1861-1955); later that year their work appeared in the annual’s first volume. In November 1903, the Baillie Gallery held an exhibition of water-colour drawings by Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951) and her Green Sheaf colleague Cecil French (1879-1953), both of whom contributed to The Venture’s second volume. A few weeks later, Baillie showcased the woodcuts of Charles Ricketts (1866-1931) and Charles Shannon (1863-1937), together with the latter’s lithographs and painted fans by Nora Murray Robertson (d. 1949) (Some Woodcuts); all three were Venture contributors. Other artists featured in both Baillie’s Gallery and his annual publication include E. Gordon Craig (1872-1966), James J. Guthrie (1874-1952), Constance Halford (1865-1952?), Elinor Monsell (1879-1954), Carton Moore Park (1876-1956), Glyn Philpot (1884-1937), Lucien Pissarro (1863-1944), Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862-1927), E. J. Sullivan (1869-1933), and Paul Woodroffe (1875-1954) (Baillie Gallery Exhibitions).

The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature was as noteworthy for its literary contents as it was for its art and design. The high quality of The Venture’s essays, poems, and stories, which featured both “assured authors” and up-and-coming young writers (Rev. of The Venture, 895), indicates that Baillie wanted his little magazine to be more than a yearly advertisement for his Gallery. Baillie took a keen interest in the annual’s letterpress from the start, working closely with co-editors Laurence Housman and W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1966) on the first volume’s contents. When they did not renew their commitment for the second Venture, the publisher assumed editorial responsibility for the issue’s literary selections as well as its artworks. Notably, Housman and Maugham were as inexperienced in editing as Baillie was in publishing (Hastings 88; Housman, Unexpected, 202). In asking Housman “to edit, and collect contributors for a new annual called The Venture” (Housman, Unexpected, 202), Baillie no doubt balanced Housman’s lack of editorial experience against his exceptional network of artists, artisans, authors, editors, and publishers in the little magazine community. Housman drew on these professional, personal, and familial connections to build an impressive literary list for The Venture’s first volume. In addition to having contributed both art and literature to The Dial, The Pageant, and The Yellow Book, Housman was also acquainted with Green Sheaf editor Pamela Colman Smith and Savoy editor Arthur Symons (1865-1945).

Co-editor Maugham shared Housman’s lack of editorial experience but did not have his connections to the little magazine community. Extant letters from Maugham to Housman suggest that the latter was responsible for securing most of The Venture’s writers (Laurence Housman Papers). Baillie may have selected Maugham, a prolific contributor to mainstream magazines and an author of popular novels, as a counter-balance to Housman’s more avant-garde predilections. In a letter to his co-editor, Maugham confided that Baillie had asked him to check Housman’s contribution for “propriety,” which he declined to do (Laurence Housman Papers). Maugham was also practical about the volume’s market value. Worried that an annual of 200 pages was too slight to justify the Venture’s five-shilling price, Maugham asked for a meeting at the Gallery to discuss the possibility of increasing the volume’s page count to 250 (ibid.). The co-editors managed to extend The Venture’s first volume to 249 pages, with 21 individual writers and 12 artists. When Baillie became sole editor of the annual, he increased the number of authors to 32 and artists to 21, but was not able to add to its bulk. At 188 pages, the second volume was significantly shorter than the first, but priced higher.

To offset his costs for printing, image reproduction, and binding, Baillie raised the annual’s price from five shillings to seven shillings sixpence. Some charges must also have been incurred from distributing The Venture. In addition to offering copies for sale through subscription and at The Gallery, Baillie supplied the trade through London’s largest distributor, Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., in Stationer’s Hall (Advertisement for The Venture, 667). Baillie saved significant expense, however, by paying nothing for the annual’s contents. In an arrangement designed to limit risk, the magazine was run “on the profit-sharing system: no contributor was to be paid except on results” (Housman, Unexpected, 202). This policy may account for the co-editors’ departure after the first issue and the annual’s few returning contributors. In the event, the publisher made no profit, the contributors were not paid, and The Venture did not extend beyond a second annual volume.

The Venture is unusual in using different printers for its two volumes. Although this did not affect the quality of production, it did result in material changes to the annual’s design and appearance. Committed to bringing out The Venture as an art object in the “book beautiful” tradition, Baillie worked with leading printers of the fine-press revival. The first volume (1903) was printed at The Pear Tree Press (1899-1951) by artist and print maker James J. Guthrie, known for his effective union of art and craft (McCleery, np). Because Baillie selected exclusively woodcuts for The Venture’s first issue, Guthrie was able to print art and text on the same laid paper, using his hand press. The second volume (1905) was printed at the Arden Press (fl 1888-1920s) under the direction of Bernard Newdigate (1869-1944) and his father Alfred (1829-1923). According to compositor James Thorp (1873-1962), their small press in Leamington produced “printing more distinguished aesthetically than any in England, except perhaps that of the Chiswick Press under [Charles] Jacobi” (Thorp 86). Baillie described Thorp, the Arden Press printer he worked with for the two titles he published in 1905—The Venture and The Dream-Garden (edited by Netta Syrett)—as a craftsman “then making a special study of the art of beautiful printing” (Syrett 148). It was likely Thorp who advised Baillie on how to achieve optimal reproduction values for the various artistic mediums featured in the Venture’s second volume. High quality reproduction required the use of four different firms. Messrs T. Brooker and Co. printed the etchings; Messrs Carl Hentschel and Co. supplied the line blocks; Messrs J. Miles and Co. printed the lithographs; and the Rembrandt Intaglio Co. produced photogravures of tonal artwork (Colophon).

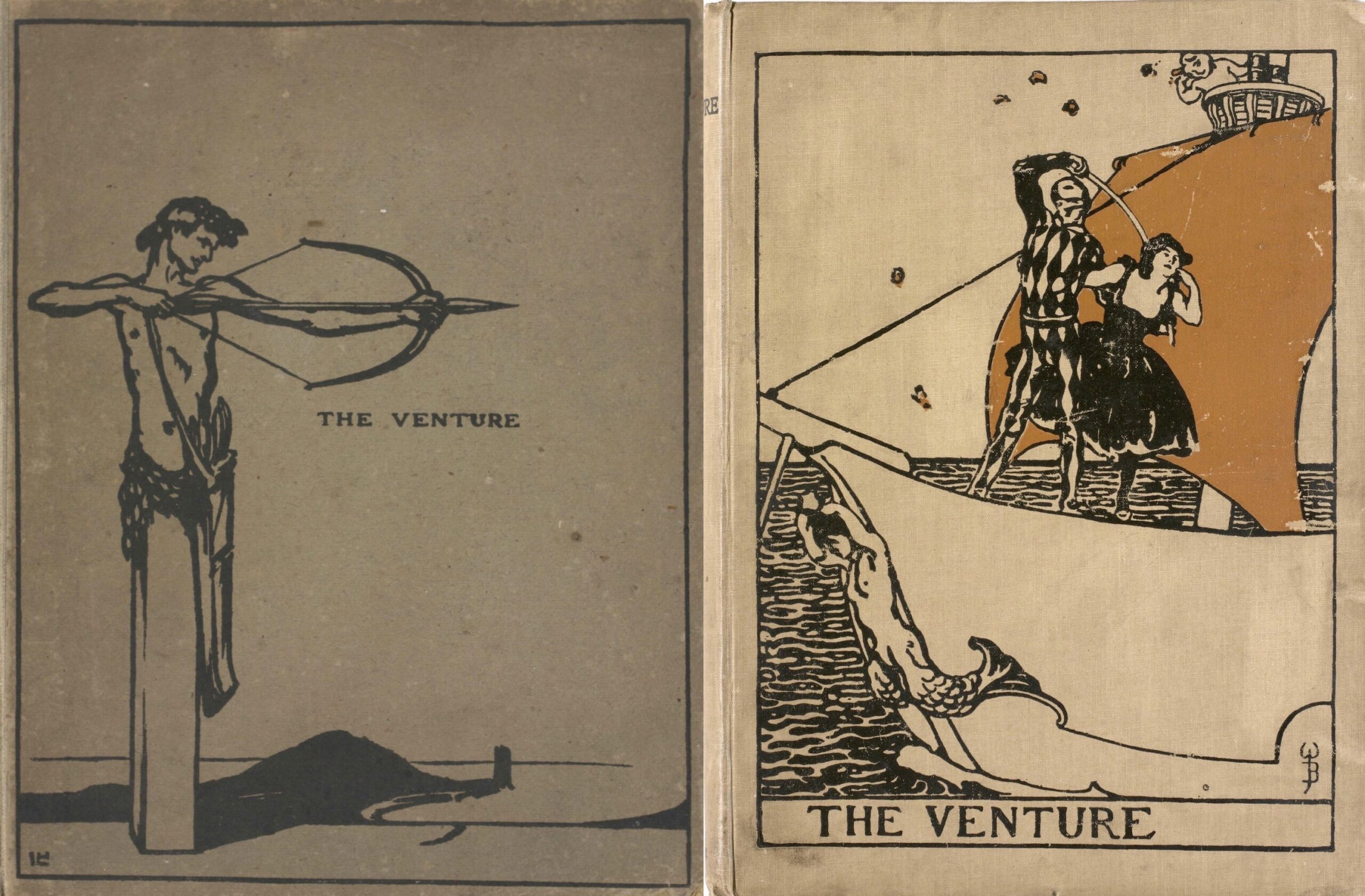

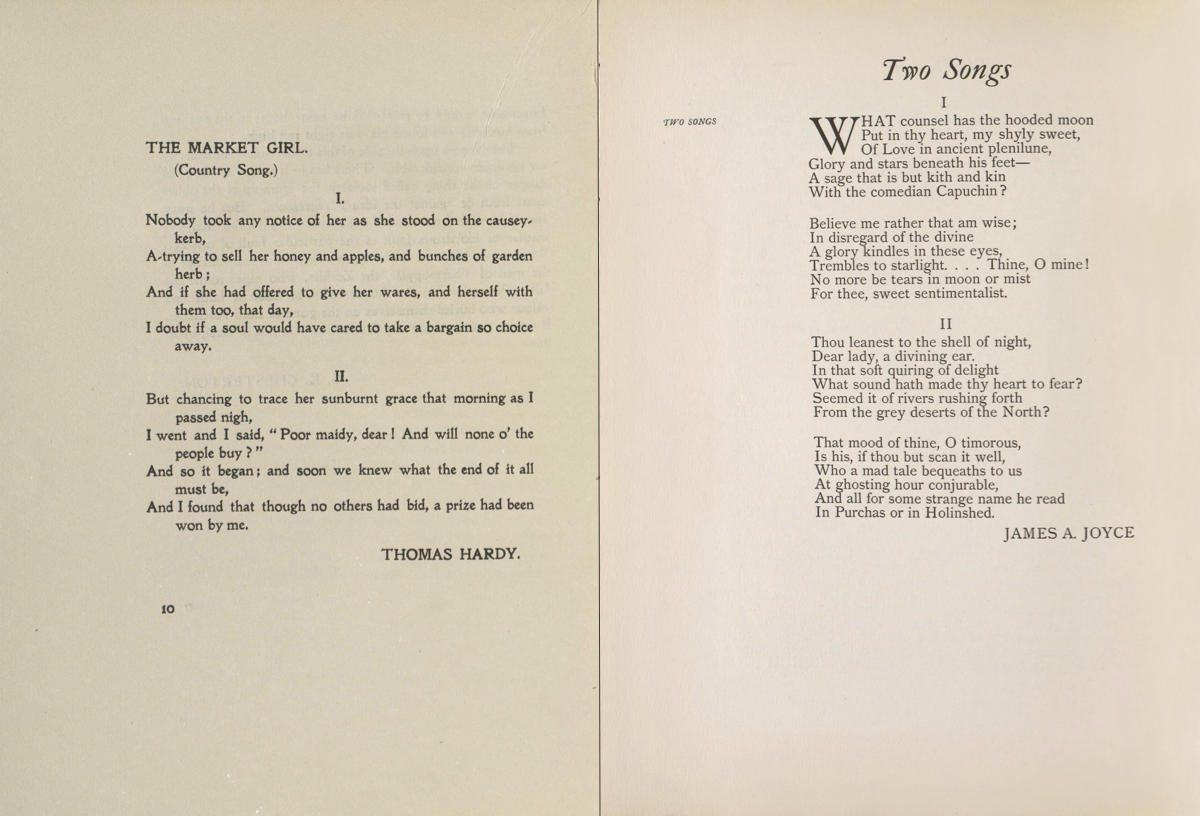

The differences in the physical design of the two volumes are evident in their distinct bindings and layouts. Instead of the paper boards with cloth spine used for The Venture’s first issue, the second was bound in a single piece of grosgrain cloth. To ensure the two volumes would harmonize when lined up on a library shelf, the colour of the cloth for the second issue was similar to the buff-coloured paper boards used for the first, and the cloth spine for each displayed similar decorative devices and information. Housman’s cover illustration for the first volume was printed in black, while that by Walter Bayes (1869-1956) for the second made dramatic use of orange ink (fig. 1). Although designed by different artists, the decorative endpapers in each volume were printed in a similar soft green. In terms of typography and layout, both volumes featured wide margins and good quality paper. However, in the Pear Tree Press printing, which used “solid old English type on antique paper” (“The Venture,” 184), “due regard,” as the Sunday Special noted, was “paid to the traditions of [William] Morris” (Advertisement for The Venture, 1904, [iii]). In contrast, the Arden Press used lighter type, which makes the second volume appear more modern in design (fig. 2). The Arden Press also moved page numbers from the bottom margin to the top, employed drop caps to introduce items, and used both side notes and italicized running heads for titles. Due to the variety of its image reproduction technologies, the artwork for the second volume could not always be printed on the same British Bond as the letterpress. Unlike the wood engravings bound into the first Venture, most images in the second volume are tipped in, reproduced on special paper, and protected by a tissue paper guard, with credits for title and artist printed on the glassine.

One of the most beautiful of all the late-Victorian little magazines, The Venture achieved critical, but not commercial, success. “The whole thing was,” according to Housman, “too highbrow to be popular; perhaps had it been published at a guinea instead of five shillings, it would have done better” (Unexpected, 203). In blaming the magazine’s failure on the buying public rather than its experimental format and cutting-edge contents, Housman echoed the apologia of editor Arthur Symons at the end of The Savoy’s print run in December 1896. Symons recognized that he, art editor Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898), and publisher Leonard Smithers (1861-1907) were foolish to hope “that the happy accident of popularity was going to befall” such an aesthetic production, and concluded that their “first mistake was in giving so much for so little money” (92). Like Beardsley, Smithers, and Symons before them, Baillie, Housman, and Maugham made the mistake of assuming “that there were very many people in the world who really cared for art, and really for art’s sake” (Symons 92).

The Venture’s final appearance in 1905 more-or-less coincides with the end of the late-Victorian little magazine as a distinctive publishing form, whose chronology on the Yellow Nineties begins with The Dial’s first volume of 1889. Notably, contemporary critics drew attention to The Venture’s position within the fin-de-siècle little magazine movement. Recognizing its aesthetic lineage, reviewers hailed The Venture as a worthy successor of The Century Guild Hobby Horse, The Pageant, The Savoy, and The Yellow Book (Advertisement for The Venture, 1904, [iii]). The Athenaeum “congratulate[d] Mr. Baillie for his enterprise” in continuing this tradition, noting that “Les Jeunes, since the prolific nineties, have had few shows of this sort” (Rev. of The Venture, 805). The Bookman went further, suggesting that “The Yellow Book would seem to have come back to us under the title The Venture” (“Notes,” 181). Meanwhile, the critic for To-Day—a weekly magazine that was “literary in tone, up to date, and urban” (Tilley, np)—predicted an eager audience for the annual. “I think there are not a few of my artistically-inclined customers who, now that the ‘Yellow Book’ and ‘Savoy’ are no more will gladly welcome a publication that aims at a high literary and artistic excellence,” wrote the reviewer, who believed that “the volume should appeal to two distinct publics” of artistic connoisseurs and discerning readers (Advertisement for The Venture, 1904, [iii]). The Academy and Literature, however, identified a more limited readership for Baillie’s magazine. Calling The Venture “a tasteful olla podrida [miscellany] of literature and art,” the critic noted that the “artistically got up” annual would appeal only “to the few and fit” (“Short Notices,” 587). Ultimately, The Venture appealed to too few people to justify the Daily Chronicle’s “hope that the authors and artists will… ‘Venture’ again and again” (Advertisement for The Venture, 1904, [ii]). Baillie did not attempt a third issue of his annual and The Venture quietly fell into critical obscurity.

In their Introduction to the Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Little Magazines, Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker rightly identify The Venture as one of the period’s “magazines of interest and significance about which relatively little is known” (4). The Venture’s presence on the Y90s Magazine Rack acknowledges the annual’s significance within the fin-de-siècle little magazine movement by putting its contents and contributors into critical context with comparable titles such as The Dial, The Evergreen, The Green Sheaf, The Pageant, The Savoy, and The Yellow Book. Brooker and Thacker categorize these as “modernist” little magazines. However, while these titles are certainly connected to the still-thriving publishing genre of the little magazine, they should not be subsumed within the category of modernist publications. The late-Victorian little magazine’s roots in the Pre-Raphaelite Germ of 1850 and close connections to the arts-and-crafts revivals of fine printing and original wood engraving are crucial to its aspirations to be, as Koenraad Claes argues, a “Total Work of Art,” integrating “medium and message, form and content, ethics and aesthetics” (1). John Baillie clearly designed his Venture to be a “Total Work of Art.”

Published at the liminal boundary of the so-called “Victorian” and “modernist” periods, The Venture provokes questions around literary history, periodization, and representation. As the project of a non-mainstream art dealer from New Zealand, The Venture invites new investigations into the transnationality of London’s art scene; the intermedial relationships across exhibition, print, and performance cultures; and the dynamic networks connecting the fine-printing and wood-engraving revivals to late-Victorian little magazines. Its virtually untapped contents include a significant proportion of Australasian, queer, and women contributors. From paratexts to contents and contexts, The Venture’s two volumes offer a rich resource for the study of little magazines as media in transition (Kooistra, “Little Magazines,” 305). Emerging at the fin de siècle in the midst of massive technological and cultural change and continuing to circulate today in both material and digital archives, little magazines such as The Venture can help in the project of “undisciplining” literary studies by insisting on the materiality, multi-modality, and collaborative creation of this counter-cultural form.

©2023 Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, FRSC, Emerita Professor of English, Senior Research Fellow, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities

Works Cited

- Advertisements. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905, pp. [i-vi]. Venture Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2023. https://1890s.ca/vv2-advertisements/

- Advertisement for The Gallery. Advertising Supplement, p. [vi]. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-advertisements/

- Advertisement for The Venture, 1904. Advertising Supplement, pp. [ii-iv]. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-advertisements/

- Advertisement for The Venture. The Athenaeum, No. 3969, 21 November 1903, p. 667.

- Baillie Gallery Exhibitions. Exhibition Culture in London 1878-1908 Database. University of Glasgow, 2006. https://www.exhibitionculture.arts.gla.ac.uk/gall_exhlist.php?gid=797

- Brooker, Peter, and Andrew Thacker. The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, vol. I: Britain and Ireland 1880-1955. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Claes, Koenraad. The Late-Victorian Little Magazine. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Colophon. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-colophon/

- The Dream Garden: A Children’s Annual, edited by Netta Syrett. London: John Baillie, 1905.

- “The Galleries and Ateliers.” Daily Mirror, 18 November, 1903, p. 6.

- Housman, Laurence. The Unexpected Years. Jonathan Cape, 1937.

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Little Magazines and/as New Media.” Cambridge Companion to Literature in Transition: The 1890s, edited by Dustin Friedman and Kristin Mahoney, Cambridge University Press, 2023, pp. 305-327.

- Laurence Housman Papers, Seymour Adelman Collection, Bryn Mawr College Library.

- “Literary Gossip.” The Athenaeum, 12 Sept. 1903, p. 351. ProQuest British Periodicals.

- Mackle, Tony. “The enterprising John Baillie, artist, art dealer and entrepreneur.” Tehinga, vol. 28, 2017, pp. 62-79. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tangarewa.

- McCleery, Alistair. “Pear Tree Press.” British Literary Publishing Houses, 1881-1965, edited by Jonathan Rose and Patricia Anderson, Gale, 1991. Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 112, Literary Resource Centre, 11 January 2016.

- “Notes on New Books.” The Bookman, January 1905, p. 181.

- Rev. of The Venture, vol. 2, 1905. The Athenaeum, No. 4024, 10 Dec. 1904, p. 805. ProQuest British Periodicals.

- “Short Notices.” The Academy and Literature, 28 November 1903, p. 587. ProQuest LLC, 2008.

- Some Woodcuts by Chas. S. Ricketts, Lithographs by Chas. Hazlewood Shannon, and Fans by Mrs. L. Murray Robertson. Exhibition Catalogue, John Baillie’s Gallery, 1903. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, University of Delaware, Libraries, Museums, and Press.

- Symons, Arthur. “A Literary Causerie: By Way of an Epilogue.” The Savoy, vol. 8, December 1896, pp. 91-92. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv8-symons-causerie/

- Syrett, Netta. The Sheltering Tree: An Autobiography. London: Geoffrey Bles, 1939.

- Thorp, Joseph (“T” of Punch). Friends and Adventures. Jonathan Cape, 1931.

- Tilley, Elizabeth. “To-Day: A Weekly Magazine-Journal (1893-1905).” Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism, edited by Laurel Brake and Marysa Demoor, 2009. C19: The Nineteenth-Century Index.

- “The Venture.” The Sketch, vol. 44, No. 565, p. 184. ProQuest British Periodicals.

- “What the Press Says of The Gallery.” Advertising Supplement, p. [vi]. The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 2, 1905. Venture Digital Edition, https://1890s.ca/vv2-advertisements/

MLA citation: Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “General Introduction to The Venture: An Annual of Art and

Literature (1903-1905).” Venture

Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine

Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital

Humanities, 2023. https://1890s.ca/VV-general-introduction/