XML PDF

Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf

No. 1, 1903

When it appeared in May 1903, the first issue of The Green Sheaf exhibited a material format more akin to fin-de-siècle American chapbooks than British exemplars of the form such as The Evergreen and The Yellow Book, whose hard-bound contents extend to hundreds of pages. In contrast, The Green Sheaf is a small demy quarto measuring about 8 ½ x 10 7/8 inches whose front and back “covers” are made of the same hand-made paper as its contents: the first issue was created by folding a single sheet twice to create eight pages. The entire contents are comprised of a decorated cover (which also serves as the title page), four pieces of literature, five illustrations, an illustrated advertisement, and a back page containing the magazine’s manifesto and providing the following bibliographic information: “Published and Edited by Miss Pamela Colman Smith, 14 Milborne Grove, The Boltons, London S.W.” (Advertisement for The Green Sheaf). Smith’s premises in Chelsea doubled as the location of her Green Sheaf School of Hand-Colouring. Its students may have helped produce the issue’s six hand-coloured images using Smith’s specially mixed pigments of quiet blues, greens, grays, and tans, offset with warm golds and reds (fig. 1). Although the same basic palette is used for the entire number, individual copies vary in tonal depth, colour details, brush strokes, and washes. The pages of the first issue are not numbered, and, in keeping with her practice throughout the print run, Smith provides no Table of Contents to acknowledge the magazine’s contributors and guide readers’ selections. In short, The Green Sheaf made its first appearance as a work of art asking to be judged in its totality.

Although the back page identifies eight “principal contributors” for the “Pictures” and “Letterpress” in the Green Sheaf’s projected 13-issue print run, the first number includes only a handful of these (Advertisement for The Green Sheaf). Smith’s terminology for the magazine’s contents recalls the precedent of The Yellow Book, which famously aimed to equalize literature and art by naming them Letterpress and Pictures in its first number of April 1894 (Kooistra and Denisoff). In other respects, The Green Sheaf could not be more different from The Yellow Book, whose hard-bound issues generally exceeded 250 pages of segregated text and image, all reproduced by photomechanical processes. The hand-printed and hand-coloured Green Sheaf aimed to integrate, rather than separate, image and text, not only on the page itself, but also—in keeping with the arts-and-crafts principles underlying the fin-de-siècle fine-printing revival—within the design of each double-page opening. The Green Sheaf is also unique in making its advertising pages integral to the design of each number, rather than either supplemental or omitted altogether, as is the case in other fin-de-siècle little magazines (see General Introduction to The Green Sheaf). Not surprisingly for a magazine conceived with the enthusiastic input of William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), The Green Sheaf was intimately associated with the contemporary Irish Revival movement at the start of its print run and featured local-colour writing throughout its thirteen issues. Notably, four of the six contributors to the inaugural number were Irish (Lady Alix Egerton, Cecil French, Lady Augusta Gregory, and Elinor Monsell); only Smith and her friend Christopher St. John were not. The latter’s presence in the magazine testifies to The Green Sheaf’s equally important connections to London-based performance communities and feminist networks.

![Figure 2. First Double-Page Opening in The Green Sheaf, No. 1, 1903 [ii-iii].](https://1890s.ca/wp-content/uploads/GS1_Double-Page-Opening.png)

The number opens with “The Book-worm,” a full-page image by Elinor Monsell (1871-1954), hand-coloured in soft greens, blues, and golds, with a single splash of reddish-pink (fig. 2). The image depicts an eighteenth-century gentleman with a pigtail and lorgnette seated on a stool, examining a massive tome propped up on a stack of books in front of a large revolving globe. A talented printmaker involved in the Irish Revival, Monsell created the Abbey Theatre logo and the pressmark for the Dun Emer Press (“Drawn to the Page”). Although named as a principal contributor in the Advertisement for The Green Sheaf, Monsell was to appear only in the first number of Smith’s magazine. Well-connected in the network of wood-engraving revivalists, Monsell also published her prints in Vale Press books produced by Charles Ricketts (1866-1931) and The Venture (1903, 1905), co-edited by Laurence Housman (1865-1959) and Somerset Maugham (1874-1965).

Across the double-page spread, Monsell’s image faces the work of the ardent Irish Revivalist Lady Augusta Gregory (1852-1932). For her first contribution to The Green Sheaf, Gregory translates “The Hill of Heart’s Desire” from the original Irish of the peasant poet Anthony Raftery (1779-1835), said to be the last of the strolling bards. In the year The Green Sheaf launched, Gregory published Poets and Dreamers: Studies and Translations from the Irish, where she translated Rafferty’s “Cnocin Saibhir” as “the Plentiful Little Hill” rather than “The Hill of Heart’s Desire” (Gregory, Poets 30). Gregory may have provided the alternative translation of Rafferty’s title for The Green Sheaf to reinforce the magazine’s keynote, which Yeats told her was to be “The Art of Happy Desire” (Yeats, Letters 3.271). Smith’s coloured headpiece illustration depicts the blind poet standing in the extreme left foreground, leaning on his shillelagh, or wooden walking stick (fig. 2). Spread out below him is a valley of farmhouses, rivers, and woodlands; a white castle with red turrets nestles against green hills, behind which loom blue and purple mountains. Across this first opening of The Green Sheaf’s first number, Smith balances the particularity of the region and its local-colour fiction against the generality of the wider world and its printed books. Her editorial combination of the local and transnational was to continue throughout the magazine’s thirteen numbers.

![Figure 3. Cecil French, "The Parting of the Ways," The Green Sheaf, no. 1, 1903, [p. v].](https://1890s.ca/wp-content/uploads/GSV1-french-parting.jpg)

The magazine’s next double-page opening features two illustrated poems. Smith places “A Song of the Pyrenees” by Lady Alix Egerton (1870-1932) on the verso and “The Parting of the Ways” by Cecil French (1879-1953) on the recto. Smith’s hand-coloured tailpiece for Egerton’s love lyric is a triptych responding to each stanza’s mood as the speaker’s relationship undergoes changes symbolically marked by sun, storm, and “slumbering moon” (iv). On the facing page, French’s self-illustrated eight-line poem records an emotional message from his inner spirit, promising that his quest for Beauty will ultimately be realized at the end of time, when all becomes one (v). French’s headpiece for the poem shows the anthropomorphic face of a rose “hung upon the Rood / Of Time” (i.e., the Cross that forms the intersection of the mortal and the eternal). Although French was not, like Smith and Yeats, a known member of the occult Order of the Golden Dawn, his symbolism of the Rose and the Cross relies on its identifying iconography, which in turn gestures toward a Rosicrucian mysticism frequently seen in The Green Sheaf (fig. 3). More immediately, French’s image and text pay homage to Yeats’s call for an Irish Revival in “To the Rose Upon the Rood of Time” (1893).

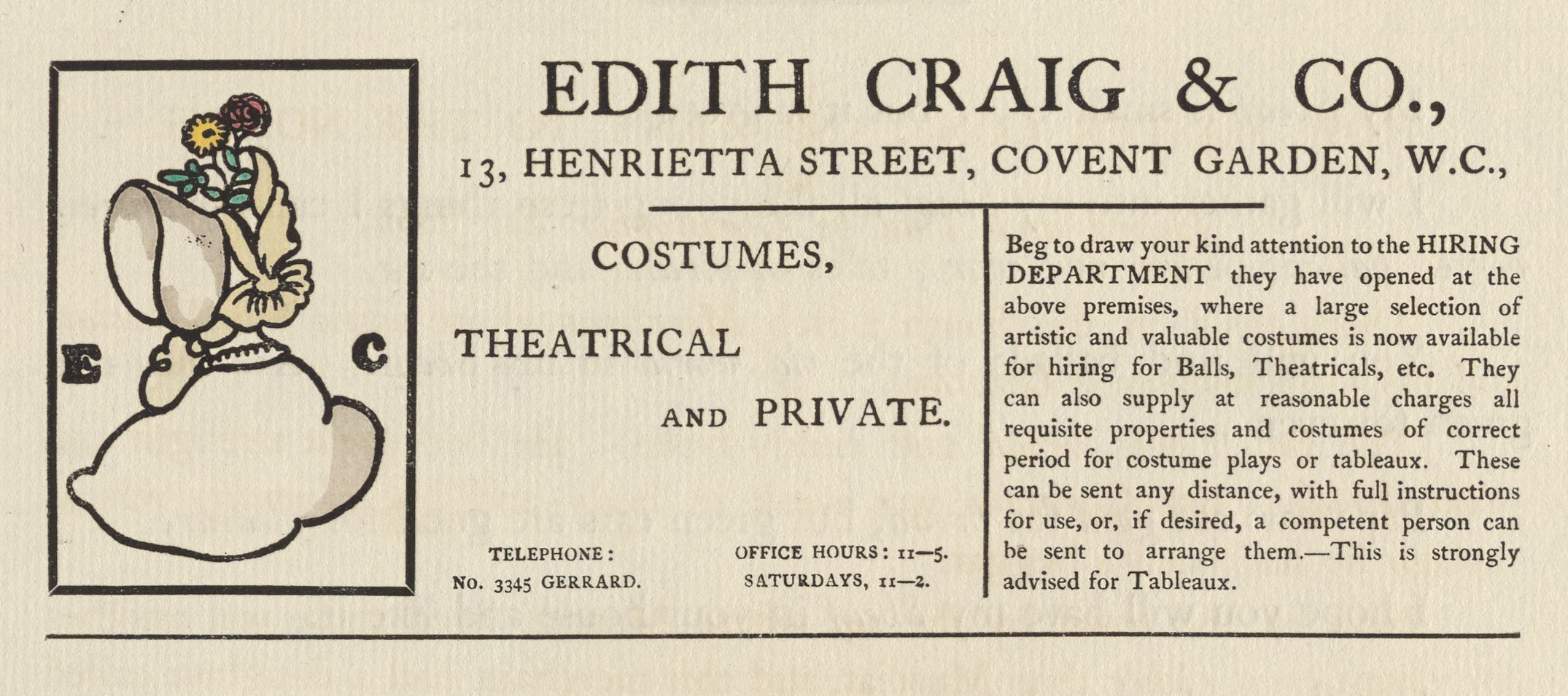

The final double-page opening in the first number features the first part of the romantic tale, “How Master Constans Went to the North,” by Christopher St. John (aka Christabel Marshall, 1871-1960) on the verso, and an illustrated advertisement for the costume rental shop of her partner Edith Craig (1869-1947) on the recto. A suffragist, playwright, and author, St. John was, like Craig and her mother, actress Ellen Terry (1847-1928), a close friend of Smith’s. In keeping with The Green Sheaf’s editorial agenda, St. John contributes a piece of local-colour fiction. This first installment tells how Constans sees the Princess of the North in his dreams and, in defiance of his wealthy father, goes on a quest to find her, as “she is my fellow” [vi]. Limited to a single, unillustrated page, the story promises “to be continued in the next Number” (ibid.). When the second and last installment appeared the following month, the story extended to two pages to accommodate a half-page illustration supplied by Smith.

As editor-publisher of The Green Sheaf, Smith was in a position to support women entrepreneurs, including herself, by featuring their businesses in the back pages of her magazine and its supplements. Marion Grant argues that Smith’s advertising pages may be more focused on promoting goods and services by women art workers than on generating income for the magazine itself (Grant, par.11). While most of the Green Sheaf’s advertisements are simply set up in letterpress, five are given illustrative treatment by Smith; notably, these are all in support of women entrepreneurs. The illustrated ads promote Smith’s for-hire performances of West Indian folktales (No. 6), custom bookplates and Christmas cards (No. 7), and newly opened Green Sheaf shop in Knightsbridge (No. 13), as well as Alice Quin’s home-made sweets (No. 9) and Edith Craig’s costume shop (Nos. 1-5). Smith devotes about a third of the page to the illustrated ad for Craig’s shop, which features a hand-coloured image depicting a woman’s gray bonnet topped with yellow daisy, red rose, and green leaves, mounted on a display stand draped by a short cape (fig. 4). Smith’s personal interest in performance art and historical costuming aligns with the premise of Craig’s hiring company. In the ad, Craig encourages prospective customers to ensure historical accuracy for their domestic Tableaux by soliciting her advice for staging and for “costumes of correct period” (Smith, Illustrated Advertisement). Similarly, in an article for The Craftsman, Smith recommends that designers study portraits for signs of the sitter’s place and time. “When you see a portrait of a historical person,” she urges, “note the dress, the type of face; note the pose, for often pose will date a picture as correctly as the hair or clothes.” If the period is not immediately evident, Smith advises illustrators to “make a pencil sketch and take it with you to some reference library,” a practice she clearly followed herself (“Should the Art Student Think?” 391).

The prominence of Smith’s illustrated ad for Craig’s costume shop in The Green Sheaf’s first five numbers highlights the intricate connections between the magazine’s Irish Revival interests and its theatrical and feminist networks. Smith first built and produced plays using a miniature theatre while living in Jamaica; later, her performances in New York and Great Britain included a production of Yeats’s The Countess Cathleen (O’Connor 166). After her father’s death in 1899, Smith came to England with Ellen Terry and began collaborating with Edith Craig on designs for the Lyceum Theatre (Cockin, 159). In spring 1903, Craig and Smith joined Yeats and others in the short-lived Masquers Society, which held its meetings at Craig’s shop in Covent Garden (Schuchard 434). In 1904, Craig and Smith collaborated on the design of Yeats’s Where There is Nothing, produced in London by the Stage Society (Schuchard 144). Later, the two were to work together on feminist plays put on by the Pioneer Players, founded by Craig in 1911, or affiliated with the Suffrage Atelier, founded by Laurence Housman in 1909 (Morton 632).

As a first foray for the novice publisher, the initial number of The Green Sheaf was an object of artistic pride for Pamela Colman Smith. In a letter to William Macbeth, the American gallery owner who sold her prints in New York, she declared, “It does look well” (qtd in Kaplan et al, 54). The effort Smith put into “planning it all out” (ibid.) is evident throughout the issue. The design of The Green Sheaf makes a distinctive contribution to the genre of the late-Victorian little magazine as “a Total Work of Art,” integrating form and content, medium and message (Claes 1).

©2022 Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, FRSC, Emerita Professor of English and Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Digital Humanities, Toronto Metropolitan University

Works Cited

- Advertisements. The Green Sheaf, No. 2, 1903, pp. 15-16. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/GSV2-ads/.

- Advertisement for The Green Sheaf. The Green Sheaf, No. 1, 1903, p. [viii]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV1-smith-manifesto/

- Claes, Koenraad. The Late-Victorian Little Magazine. Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

- “Drawn to the Page: Irish Artists and Illustration 1830-1930.” Trinity College Dublin Library. https://dttp.tcd.ie/artist/35

- Cockin, Katharine. “Bram Stoker, Ellen Terry, Pamela Colman Smith and the Art of Devilry.” Bram Stoker and the Gothic: Formations to Transformations, edited by Catherine Wynne, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 159-171.

- Egerton, Alix. “A Song of the Pyrenees,” illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 1, 1903, [p. iv]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV1-egerton-pyrenees/

- French, Cecil. “The Parting of the Ways,” illustrated by Cecil French. The Green Sheaf, No. 1, 1903, [p. v]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV1-french-parting/

- Grant, Marion. “Advertising Women’s Entrepreneurship in The Green Sheaf: Pamela Colman Smith and the Fin-de-Siècle Marketplace.” Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies, Special Issue on “Women and Other ‘Undesirables’: Female Creative and Technical Labor in Nineteenth-Century Print Culture,” edited by Jocelyn Hargrave and Megan Peiser, vol. 18, no. 2, Summer 2022, 22 pp. http://ncgsjournal.com/issue182/index.html

- Gregory, Lady Augusta, trans. “The Hill of Heart’s Desire,” illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 1, 1903, [p. iii]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV1-gregory-hill/

- —. Poets and Dreamers: Studies and Translations of the Irish. Dublin: Hodges, Figges, and Co.; New York: Charles Scriber’s Sons, 1903. Project Gutenberg.

- Kaplan, Stuart R, with Mary K. Greer, Elizabeth Foley O’Connor, and Melinda Boyd Parsons. Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story. U.S. Games Systems, 2018.

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen and Dennis Denisoff. “The Yellow Book: Introduction to Volume 1 (April 1894).” Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2010. Rev. ed., Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/yb-v1-introduction/

- Monsell, Elinor. “The Book-worm.” The Green Sheaf, No. 1, 1903, [p. ii]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV1-monsell-bookworm/

- Morton, Tara. “Changing Spaces: Art, Politics, and Identity in the Home Studios of the Suffrage Atelier.” Women’s History Review, vol. 21, no. 4, 2012, pp. 623-638.

- O’Connor, Elizabeth. “Pamela Colman Smith’s Performative Primitivism.” Caribbean Irish Connections: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Alison Donnell, Maria McGarrity, and Evelyn O’Callaghan, University of the West Indies, 2015, pp. 157-73.

- St. John, Christopher. “How Master Constans Went to the North.” The Green Sheaf, No. 1, 1903, [p. vi]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV1-st-john-constans/

- Schuchard, Ronald. “W.B. Yeats and the London Theatre Societies, 1901-1904.” Review of English Studies, n.s., vol. 29, no. 116, 1978, pp. 415-446.

- Smith, Pamela Colman. Front Cover for The Green Sheaf, No. 1, 1903, [p. i]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV1-smith-front-cover/

- —.Illustrated Advertisement for Edith Craig & Co. The Green Sheaf, No. 1, 1903, [p. vii]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV1-craig-ad/

- —. “Should the Art Student Think?” The Craftsman, vol. 4, no. 4, July 1908, pp. 417-19. Reprinted in Stuart R. Kaplan, et al, Pamela Colman Smith, pp. 389-91.

MLA citation:

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf No. 1, 1903.” Green Sheaf Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2023. https://1890s.ca/gsv1_introduction/.