THE CONTENTS

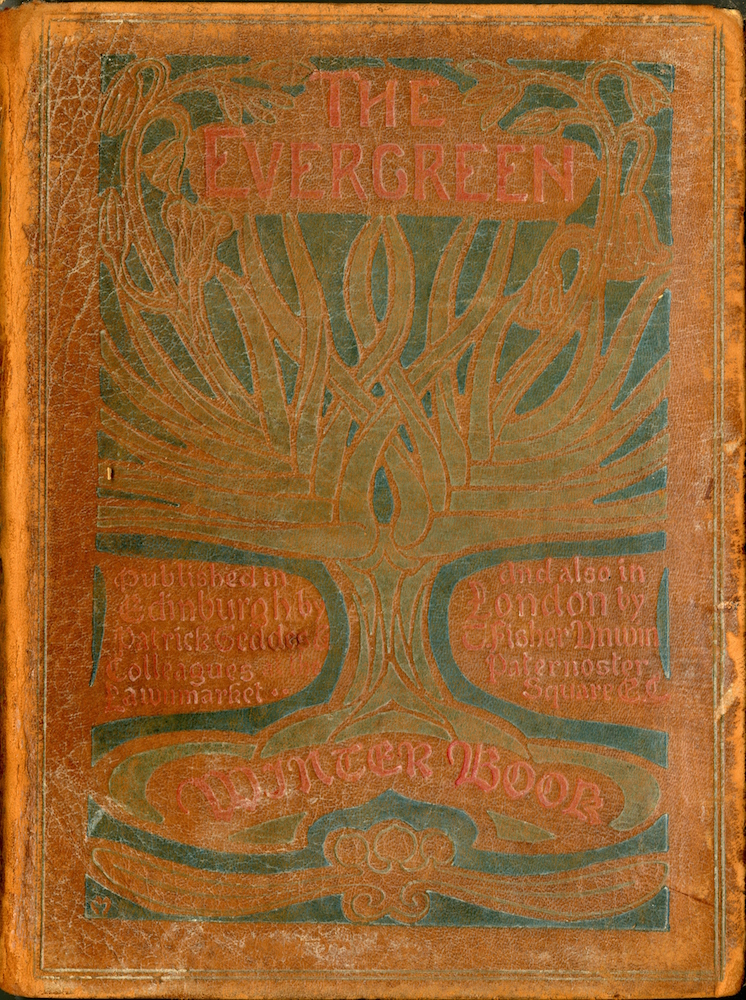

Cover . . . . . by

CHARLES H. MACKIE.

[1] Half-title

page . . . [artist

unknown.]

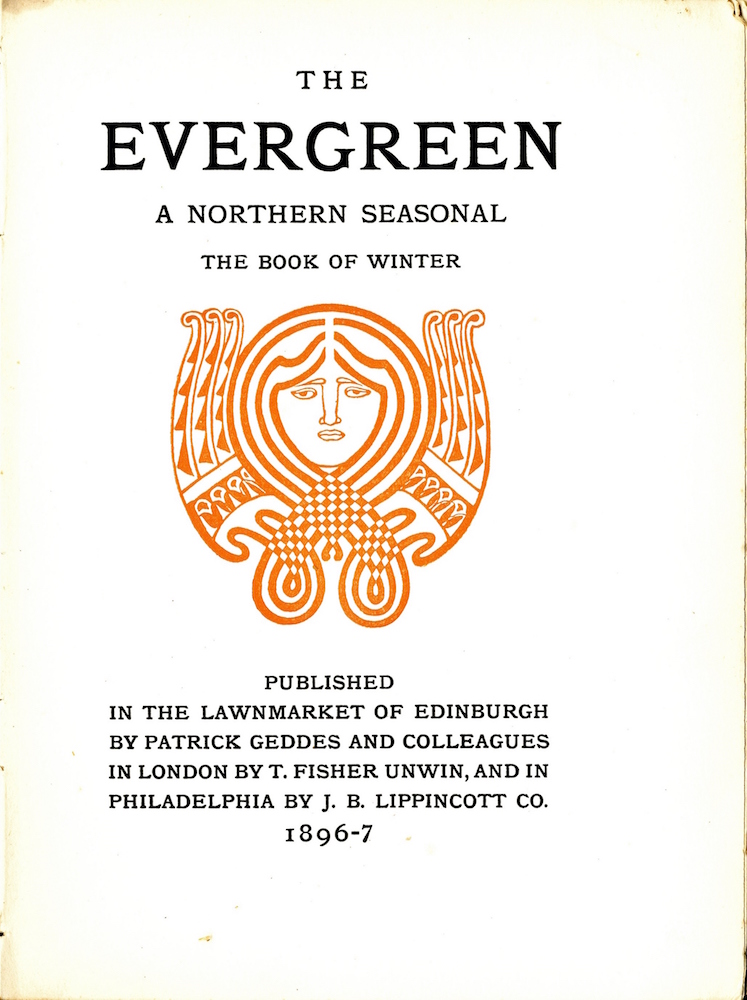

[3] Title-page . . . . decorated

by JOHN DUNCAN.

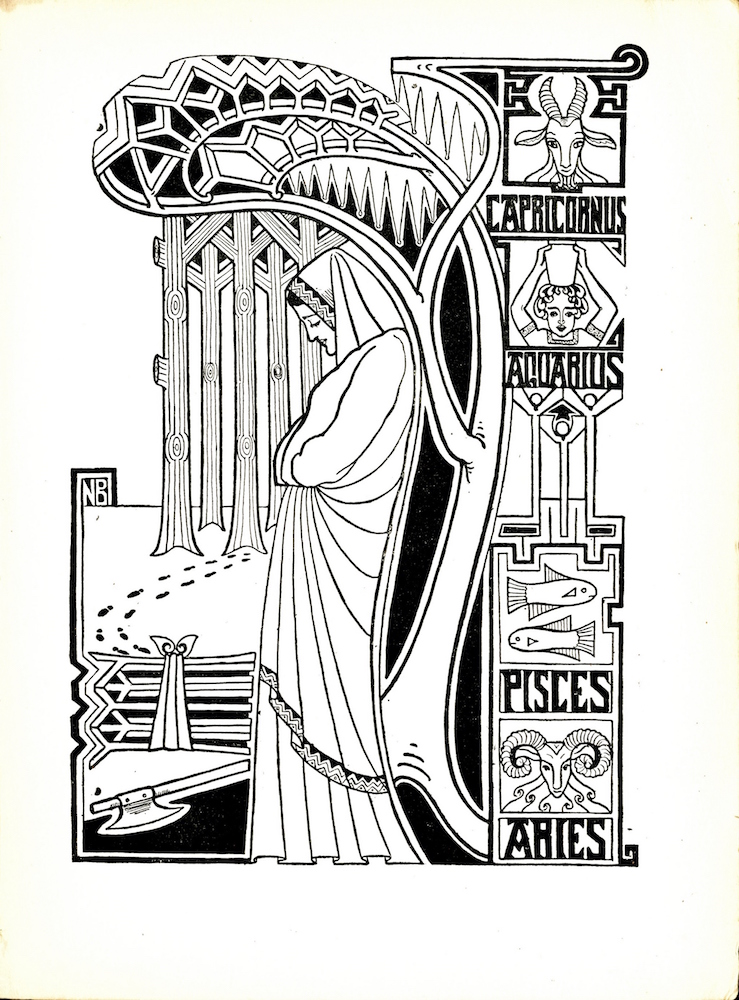

5 Almanac . . . . by NELLIE BAXTER.

6 The

Contents . . . decorated

by NELLIE BAXTER.

THE CONTENTS

I. WINTER IN NATURE

8 The Biology of

Winter . . J. ARTHUR THOMSON.

21 A Winter

Song . . . . SIR GEORGE DOUGLAS.

22 Impressions

of

Winter . . . DR. EDWARD B. KOSTER.

28 Winter . . . . . . ROSA MULHOLLAND

II. WINTER IN LIFE

35 Fantasies . . . . . J. H. PEARCE.

1. A Year and a Day.

2. An Odd Coincidence.

43 When the

Dew is

Falling . . FIONA MACLEOD.

44 The Mother

of Jesus

. . . KATHARINE TYNAN.

51 Symbols . . . . . . W. J. ROBERTSON.

53 Frost . . . . . . ELIZABETH A. SHARP.

61 Between the

Ages . . . . NIMMO CHRISTIE.

63 Il

neige . . . . . . PAUL DESJARDINS.

III. WINTER IN THE WORLD

67 The

Dream . . . . . H. C. LAUBACH.

and

The

Fulfilment . . . . W.M.

69 Sant

Efflamm and King Arthur . EDITH WINGATE RINDER.

75 All Souls’

Day . . . . . NORA HOPPER.

75 Pourquoi

des Guirlandes Vertes . ELIE

RECLUS.

à

Noël . . . . . .

91 Christmas

Alms . . . . DOUGLAS HYDE, LL.D.

99 The

Love-Kiss of Dermid

and FIONA MACLEOD.

Grainne . . . . .

101 Dermot’s

Spring . . . . STANDISH O’GRADY

106 A Devolution of

Terror . . . CATHARINE A. JANVIER.

IV. WINTER IN THE NORTH

115 Grierson of

Lag . . . . W. CUTHBERTSON.

118 The Snow Sleep of Angus

Ogue . FIONA MACLEOD.

127 The Chiefs’ Blood in

Me . . SARAH ROBERTSON MATHE-

SON.

128 The Story of Castaille

Dubh . MARGARET THOMSON.

132 The Black

Month . . . . M. CLOTHILDE BALFOUR.

141 The Best of

All . . . . W. MACDONALD.

142 The Megalithic

Builders . . PATRICK GEDDES.

155 Envoy . . P.G. and W.M.

DECORATIONS

Cover . . . . . . CHARLES H. MACKIE.

5 Almanac . . . . . . N. BAXTER.

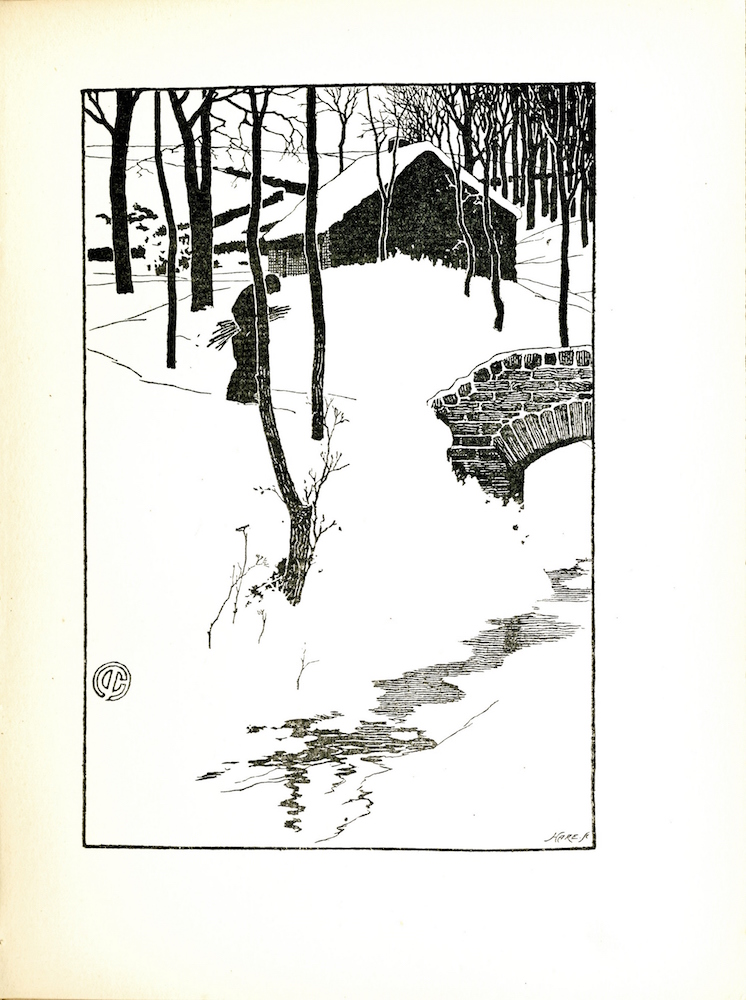

19 A Cottage in

a

Wood . . . JAMES CADENHEAD, R.S.W.

33 A Winter

Harvest . . . . A. G. SINCLAIR.

49 Madonna and

Child with St. John ANDREW K.

WOMRATH.

65 The

Sphinx . . . . . JOHN DUNCAN.

77 Winter . . . . . . W.G. BURN MURDOCH.

97 ‘By the

Bonnie Banks o’ Fordie’ . CHARLES H. MACKIE.

113 Aslavga’s

Knight . . . . ROBERT BURNS.

125 St. Simeon

Stylites . . . ANDREW K. WOMRATH.

139 Felling

Trees . . . . . CHARLES H. MACKIE.

153 Winter

Landscape . . . . JAMES CADENHEAD, R.S.W.

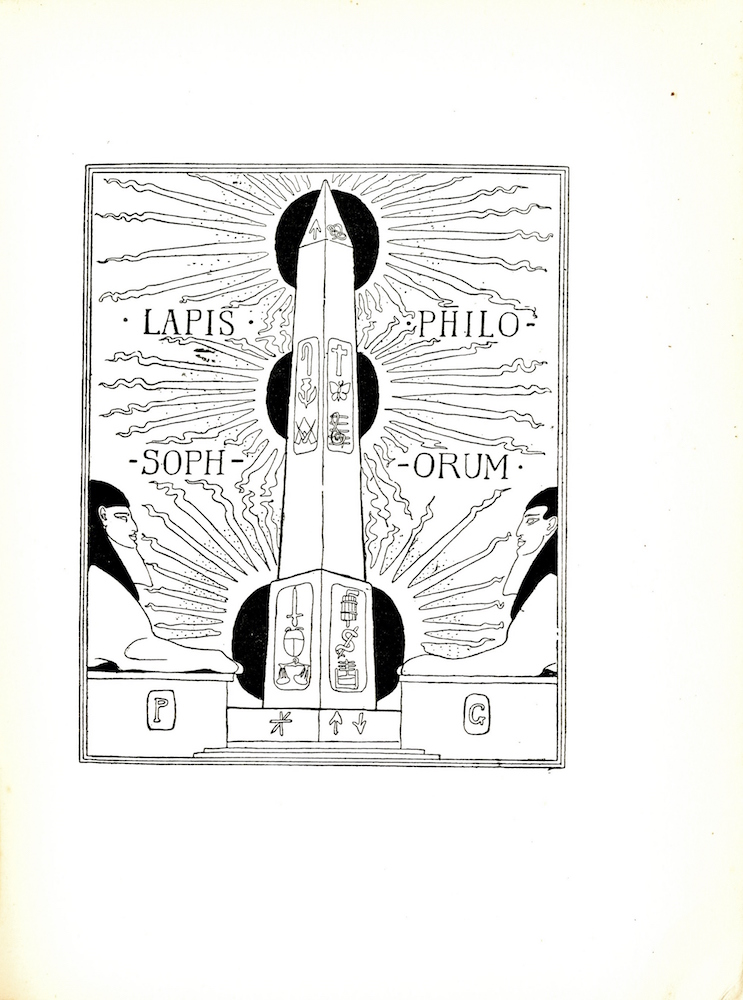

157 Lapis Philosophorum

HEADPIECES AND TAILPIECES BY

NELLIE

BAXTER . . Headpieces:

6, 21, 27, 43, 44, 51, 67, 69, 79, 106, 115

Tailpieces: 22, 60, 90, 131

ANNIE

MACKIE . . Headpieces:

35, 101 Tailpieces: 31, 52, 151

EFFIE

RAMSAY . .

Headpieces: 8, 91 Tailpieces:

62, 95

JOHN

DUNCAN . . Headpieces:

28, 53, 62, 99, 118, 127, 128, 132, 141, 142, 155

Tailpieces: 74, 100

[158] T. and C. Constable

Printers Colophon

Back

cover . . .

. . by

Charles H. Mackie

THE BIOLOGY OF WINTER

ARGUMENT.—I. An appreciation of the full biological import of Winter

is not altogether easy for us, here and now. We must think of peoples with

less artificial environment, of more wintry regions, and of Glacial Epochs.

II. The Sagas of the Biology of Winter are to be found in such stories as

those of the Sleeping Beauty and Balder. III. The astronomical facts bear

out our vaguer impressions. IV. Reactions to the cold and scarcity of

Winter are very variable:—flight, concealment, colour-change, and so on.

V. Hibernation in its varying degrees is a common solution. VI. Yet to

many death is inevitable. Winter is the time of intensest elimination. This

affects not only individuals, but races. The tree of life grows, but it is also

pruned. The only biological consolation is that the fruition of the tree has

improved.

I

A TRUE judgment as to the biological import of a

Northern Winter is not altogether easy for us,

here and now. It is not easy for us, who are

cunning and far-sighted, clothed and fire-making

organisms; it is not easy here, for, in spite of our

grumbling, a British Winter is usually a mild

affair; it is not altogether easy now, for our worst winters are but

far-off echoes of the Glacial Epoch, when Winter not only con-

quered Summer, but remained victorious for Ages. Thus it is

evident that to do Winter justice we have need to question the

Lapps and Samoyedes and other dwellers in the Far North,

or, where they have not voices, explorers like Nansen and

9

Peary; we must think of the Polar Regions, of Alpine life

above the snow-line, or of that dark, silent, plantless, intensely

cold world—the Deep Sea—where the spell of Winter is un-

relieved and perennial; and we must let our imagination travel

back to the Ice Ages—the Ages of Horror—during which

whole faunas shuddered. Unless we make some such efforts,

which we can only now suggest, we are likely to estimate the

power of Winter too lightly, and fail in seeing to what degree

it casts a spell, often a fatal one, upon life.

II

A true appreciation of Winter was long since expressed in the

story of the Sleeping Beauty. She was richly dowered, we

remember, with vigorous beauty and joyous grace, but all her

gifts were shadowed by the foreboded doom of early death.

Yet by a friendly fairy in reserve, to wit, the residual beneficence

of Nature, the doom was transmuted into a kinder spell, which

bound her to sleep but not to dying. All care notwithstanding,

the spindle pierced her hand, she fell into deep sleep, whence

at last the Prince’s kiss served for her awakening. Various

commentators apart, the meaning seems plain: the Princess

was our fair earth with all its glow of life, her youth was

Summer—often shadowed—the fatal spindle was the piercing

cold, the spell-bound sleep was Winter’s long rest, the kiss that

awakened was the first strong sunshine of Spring. The beauti-

ful old story is literally one of the ‘fairy-tales of Science.’

In the same way, though there is doubtless much else in

the myth, we can have no doubt that Balder the Beautiful

represented the virility and vitality of the sunny Summer, and

that the twig of gloom, the Mistletoe, which flourishes and

fruits in Winter, was the emblem of the freezing cold which so

oftefi brings sudden death or the quiet peace of sleep. A

similar interpretation holds for the not less subtle allegory of

Proserpina.

10

III

But let us turn from fancy to fact! The astronomers tell us of

the general law that on either hemisphere 63 per cent, of the

total heat of the year is received during Summer, and 37 per

cent, in “Winter; but we feel that this statement, fundamental as

it is, hardly expresses the full force of the case. First of all,

the astronomers are thinking, and, from their point of view,

rightly, of a year with only two seasons; therefore, as we are

dealing with four, we must refer part of the 37 per cent, received

in Winter to late Autumn and part to early Spring, leaving

Winter poor indeed. The same authorities also tell us that the

length of Summer and Winter is variable; thus we have now 186

days of Summer, and 179 days of Winter (in the two-season

sense), while it is but a geological yesterday since in the Ice

Ages the Summer lasted for only 166 days, while 199 lay in the

grasp of Winter. This is again very important, for the total

amount of warmth received has obviously to be divided by the

number of days in the season, to give us a numerical expression

of the mean daily sun-heat at any given time. Yet finally, this

must not hide from us the commonplace of experience that it

is not the average temperature which, so to speak, says yea or

nay to this or that form of life ; it is rather the occurrence of

certain maxima and minima, a terrible heat-wave or a week of

fatally frosty nights.

IV

To the cold and scarcity of food which Winter involves in this

and more northerly latitudes, there is great variety of reaction

on the part of organisms. Of this variety we can only give a

few illustrations. Thus most of our birds, emblems of freedom,

escape the spell by flight, and, though death is often fleeter

still and overtakes them by the way, there can be no doubt

that the migration-solution is an effective one. Among those

11

who are hardy enough, or foolhardy enough, to remain with us,

the rate of mortality is often disastrously high.

Other creatures, unequal to the long and adventurous journeys

of the birds, retire into winter-quarters, in which they lie low,

awaiting happier days. Thus the earthworms burrow more

deeply than ever, the lemmings tunnel their winding ways be-

neath the icy crust of the Tundra, the pupae and cocoons of

insects lie inert in sheltered corners, the frogs bury themselves

deeply in the mud, and the slow-worms coil up together in the

penetralia of their retreats.

Others, again, such as the Arctic fox, the mountain hare, the

ermine, the Hudson’s Bay lemming, and the ptarmigan, face

the dread enchantment, but turn paler and paler under the

spell, until they are white as the snow itself—a safety-giving

pallor. It seems likely that a seasonal colour-change of this

nature is, in the formal language of the schools, a modification,

induced by the cold, but superposed upon a constitutional

variation or hereditary predisposition to change. Thus it is

well known of Arctic fox and mountain hare, for instance, that

the degree of whiteness varies from year to year with the

intensity of the Winter. As for its utility, this is at least

twofold—the white dress is of service alike in the chase and in

flight, while on the other hand it is the warmest dress when

the external temperature is less than that of the body.

Man, himself, gets inside other creatures’ skins, and bids

defiance to weather, or, having in his cunning tapped one of

the earth’s great stores of energy, sits by the hearth gloating

in the warmth of a larger sun than that which now sends him

too little cheer. His indifference is, however, in part artificial,

as a prolonged coal-strike shows; in part, a privilege of the

few, as a glance at the tattered and torn suffices to prove; and

in part, merely local, as a short journey northwards convinces

us; and he, too, like the birds, often migrates even from our

British mildness to a sunnier South, and knows, like many

a beast, of winter-refuges, whether in Scottish poor-house or

Mentone ‘pension.’

12

V

To many organisms, both of high and low degree, the alterna-

tive comes,—to sleep or die. The spindle cannot be escaped,

the cold shall pierce like a sword:—but sleep! and it may be

well. Of this sleep there are indeed many degrees, from the

mysterious latent-life of frozen seeds and animal germs, to the

almost equally mysterious true hibernation of marmot and

hedgehog. Often, too, it must be confessed that what began

in slumber ends by becoming sleep’s twin-sister, Death. Yet,

we understand so little of any of these more or less dormant

states in their relations to one another, or, indeed, of any one

by itself, that we may avoid an analysis which would be in-

appropriate here, and think of Winter as the sleep-bringer.

The great hypnotist lifts his hands, and the sap stands still in

the tree, and the song is hushed in the bird’s throat; he makes

his passes, and growth ceases in bud and seed, in cocoon and

egg; he breathes, and sleep falls upon marmot, hamster, and

hedgehog, upon tortoise, frog, and fish, upon snail and insect;

he commands—his voice is the North Wind,—and the water

stands in the running brooks, and the very waves of the fiord

are still. Even in our own mild country, is not the freezing of

Loch Fyne upon record?

Apart from the state of latent life—in which a paste-eel, for

instance, may lie neither living nor dead for fourteen long years,

and seeds for many decennia—there is no form of sleep so near

to death as this to which the Wizard of the North commands

the true hibernators. Somnolence penetrates to the deep

recesses of the creature’s being, as the histologist well knows,

who tells us of the minute structural changes observed in the

cellular elements of the sleeping hedgehog.

The heart beats feebly and intermittently, breathing is at long

intervals and very sluggish, the food-canal is empty, income is

almost at zero, and expenditure but little more. The sleeper

may be immersed in water for twenty minutes, or subjected

without apparent result to noxious gases. The fat, accumulated

13

in days of plenty, is slowly burnt away, sustaining in some

measure the animal heat. Yet temperature falls very markedly,

to a degree which in ordinary life would be fatal; irritability

wanes to a minimum; the ordinary reflexes are at most faint;

and the creature steadily loses weight. The wonder is that it

keeps alive.

The slumberers differ much in the soundness of their sleep. Thus

there are light sleepers, like the dormouse, the harvest mouse,

and the squirrel; and heavy sleepers, like hedgehog, hamster,

and marmot, or like the tortoise, whom the crack of doom

would scarce disturb. Quaint is the somnolence of the mother

polar bear, who, after awaking in her snowy couch to give birth

to her two cubs, sets them a-sucking, yawns, and falls asleep

again. But she, and even the seven sleepers, must yield to the

snail who overslept himself so far that when he awoke it was

in a case in the British Museum wherein he bore a ticket already

many years old. There was another Rip van Winkle snail who

awoke to find himself an extinct species, but that, as they

say, is another story!’

After we allow for the tendency cold has to produce coma, of

which Alpine travellers have told us tales; for the drowsiness

which is said—let us hope it is true—to take the edge off starva-

tion ; for the sleepiness induced, e.g., in church or lecture-room

by confined atmosphere, of which no proof is required, there

seems to be need of further physiological explanation. It has

been suggested, and wisely it seems to us, that the retention

of waste-products induces a state of ‘auto-intoxication’—a

drugging or poisoning of the system with its own excretions,

a banking-up of the fire of life with its own ashes. It seems

plausible that this will tend to keep the sleepy sleeping, and

the idea maybe hazarded that one of the reasons why plants

are not more wide awake is just this retention of nitrogenous

waste-products. For it is well known that plants do not get

rid of these. The same is in a measure true of the sea-squirts

or Ascidians, which in their adult life are notoriously plant-like

and sleepy animals.

14

The general import of hibernation is in most cases plain. Life

saves itself by ceasing to struggle, by retiring within its en-

trenchments. Death is baffled by a device in which activity

virtually ceases without life itself being surrendered. Yet

there are other aspects of the Winter’s sleep. To some it is a

time of repair—a long night—after the nervous fatigue of a

longer day. Thus, it is not difficult to understand that, quite

apart from the weather, it is good that the queen humble-bee

should sleep through the Winter, just as it is well for the fisher-

man that he should weep after the storm. In short, we return

to our main thesis, that life is rhythmic, and that the seasons

punctuate it.

To others the sleep is in some measure a preparation for a new

day. Thus in the seeds which slumber in the earth, each a

young life, there is a rotting away of the husks which the

delicate embryo could scarce burst, and later on there are pro-

cesses of fermentation, by which the legacy of hard, condensed

food is made available for the young plant. That it is not

merely the unpropitious weather and the hard soil which

make it necessary for the seeds to sleep may be proved by

experiment, and is also shown by the fact that not a few

normally lie dormant for several years. Similarly, within the

cocoons there lie the chrysalids, quaintly mummy-like and

inert to all appearance, but slowly undergoing that marvellous

transformation, the result of which is the winged butterfly—the

Psyche.

VI

It seems a true paradox that one of the great facts in the

Biology of Winter is the Frequency of Death. Not that there

is any season when Death is not busy, or any opportunity which

he does not seize; he winnows among the newborn weaklings

of the early Spring, he lays pitfalls for the adolescent, he thins

the ranks of Summer’s industry, he puts in a full stop at the

limit of growth, he forces open the door which love seeks to

15

keep closed, he harvests in Autumn; but it is in Winter that

his power is most felt. It is the time of the least heat, least

light, least food; and life hurries on the downgrade to death.

The influence on plant-life is most obvious and direct; a large

fraction of the income of radiant energy is cut off, the water-

supply is also reduced, and there is further risk that the frost

cause bursting of cells and vessels within the plant just as in

our houses. The diminished vigour of plant-life means less

food for the animals, and on them too the relative lack of

warmth and light has a directly disastrous effect. Given

‘A winter such as when birds die

In the deep forests, and the fishes lie

Stiffened in the translucent ice, which makes

Even the mud and slime of the warm lakes

A wrinkled clod, as hard as brick,’

the decimating influences are perceptible on every side. Thus

of the mortality during the hard winter 1894-95 we have eloquent

statistical evidence from moor and forest lake and seashore.

Winter is indeed a time of rest and sleep, but as truly of

elimination and death.

Death always means the irrecoverable cessation of bodily life,

but it has so many forms—violent, bacterial, and natural,—each,

again, with its subdivisions, that we cannot without inquiry say

for any particular case that the rate of mortality is greatest in

Winter. Yet the general induction appears safe that in our

latitude Winter is the time of severest elimination. Thus the

season which is apt to seem dull to the field-naturalist is full of

interest to the evolutionist. The hedgerows are bare, and the

woods silent, the pools are clear and apparently devoid of life,

the shore is comparatively barren, even the sea has lost much

of its wonted abundance. And, though much of this scarcity is

only apparent—life lying low, or asleep, or on a journey—we

must allow that it is often altogether sped. Proserpina has

gone down to Hades. Balder is dead. We have, in short, to

face the inexorable process of natural selection, whereby the

16

relatively less fit to the conditions of their life tend to be elimi-

nated, i.e. tend to die before the normal time, and to leave

behind them less than the normal number of offspring. Winter

is the time when the tree of life is most rigorously pruned.

In our study of the decadence of Autumn, we spoke of the

death of individuals and of the consolation which is offered in

the persistence of the race, but we cannot think long over such

matters without recognising that the race itself may perish.

We need only reverse the hands of the geological clock a few

seconds to be convinced of this. We need only go back to the

more recent ice-ages—the ages of Winter’s tyranny—which are

not long past, as time goes. Indeed, we need not leave human

or even modern history at all to find sadly abundant illustra-

tion of lost races.

Keeping, however, to recent animal history, where are the

bears who had their dens in Athole, or the wild boars of the

great Caledonian forest, or the busy beavers who cut their logs

in the Pass of Killicrankie, or the white bulls who wallowed in

the dark waters of the hidden tarns, or the wolves with which

Wales paid her tax to King Edgar?

Or, again, where are the early companions and rivals of our

forefathers in Britain—the cave-lion, the cave-bear, the cave-

hysena, the shaggy mammoth, and the woolly rhinoceros?

Do we know of them at all except in so far as our inheritance

includes some of that hardihood, wisdom, and gentleness which

they and others helped to work out in man?

Or, going much further back, where are the delicately beautiful

graptolites, the quaint trilobites, the great sea-scorpions, the

ancient heavily-armoured fishes, the giant amphibians, the

monstrous reptiles, the dragons, the toothed birds, the old-

fashioned mammals? The most powerful, the most fertile have

not been spared, even those which seem as though they had

been built not for years but for eternity, have wholly passed

away. This is no mere case of leaves falling from off the tree,

it is a lopping of branches.

For some of these lost races, competition was doubtless too

17

keen—they outlived their prosperity and went to the wall; for

others the force of changing circumstances was too strong—

they were not plastic enough to change; for others, perhaps,

over-specialisation or feverish activity was fatal; for others it

may be that their constitution was at fault, and that they went

down to destruction, as Lucretius finely phrased it, ‘hampered

all in their own death-bringing shackles.’ We cannot console

ourselves with any vague notion that such disappearance is a

misnomer for transmutation into some nobler form; that may

be true of certain species, but it is not true of the wholly

extinct races. Nor is there consolation in the notion that the

atoms which were once wrapped up in that whilom bundle of

life known as the Ichthyosaurus may now be part and parcel

of us; for we feel that those particular combinations which we

have called lost races—those smiles of creative genius,—have

gone, gone as utterly as the snows of yester year.

Thus from the elimination now observable around us in this

wintry season our thoughts naturally pass to the great world-

wide process, continuous since life began, which embraces us

also in its inexorable sifting. It does not indeed explain us,

nor the organisms we know, any more than the pruning-hook

explains the tree; but given life and growth, we cannot under-

stand their history apart from elimination. In short, we need

our Winter to explain our Summer, and this perhaps is the only

consolation which the biologist can suggest to the discontented

—that the history of the world as a whole is the history of

a progressive development. The fruition of the tree im-

proves. Perhaps the impersonality of this consolation is

the reason why he who was a very Gallio in Summer

becomes a religious man in Winter.

J. ARTHUR THOMSON.

A COTTAGE IN THE WOOD

BY JAMES CADENHEAD, R.S.W.

A WINTER SONG

THE wreath is faded from the reveller’s brow,

Never a flower remains!

Where is the beauty, where the gladness now—

The lip the vintage stains?

Fled as a dream! But, by my dying fire,

As I sit here alone—

The snowflakes spotting all her dusk attire

Enters a wrinkled crone:

‘Cottage and hall alike must ope to me,’

Quoth the unwelcome wife;

‘I come, uncalled, to bear you company,

And leave you but with life!’

GEORGE DOUGLAS.

IMPRESSIONS OF WINTER¹

A BLEAK day in the beginning of winter which

has come over the land with showers and fitful

gusts. With a sudden whistling sound these

showers and gusts make themselves heard, dying

away again with long-drawn, rasping soughs,

like the falsetto tones of an old worn-out singer.

The sky is greyish blue, with here and there a wandering cloud,

which borrows a yellow glare from the sun’s glory.

On the horizon a faintly undulating line denotes the limit of a

mass of violet-grey clouds. In this deep bed the tempests go

to rest after their distant raids, when they have chased before

them the last stricken leaves; raised in yellow nebulous whirls

the sand of the downs to a fearful height; swept the foam of

the sea like a snowstorm of large, bewildering flakes; and

ruthlessly whistled through the branches of the trees which

shiver in their nakedness.

Now, however, the fury of the wind, that, after the calm death

of autumn, rode on the wings of the tempest to sway sky and

earth, has spent itself. Yet, every now and then, swelling

gusts, like the last breathings of an exhausted wrestler, gasp

through the air, curling the while the steel-blue water into

gentle ripples.

¹Translated by the author from his Dutch originals.

23

Over the river the sea-gulls are flapping their wings; or, with

stiff stretched pinions skimming the surface, they glide slowly

into the water. Some of them for a while soar in stately circles

through the sky until they suddenly shoot down, their bills

stretched forward, describing a slight perpendicular in the air.

Their hoarse shrieks mingle with the groanings of the wind

as from time to time it rises.

But at nightfall birds and gusts are hushed, and the water is

lying in dead calm under the deep red glare of the sinking sun.

II

The sun has burst forth. By the intense glow of his pomp of

rays he has in the morning overcome the cold, pale hosts of

nebula and triumphantly entered the high-roads of the sky

which open in blue splendour for his jubilant march. Now,

ruler of the skies, he casts his dazzling brilliancy upon the

hoary snow-sheets of the earth.

The sky is streaked with long-drawn feather clouds like unto

the tender down on a dove’s neck. Layers of them glide over

each other and lie in a rising undulation on the dull blue, like

great palms of peace.

A subtle, tremulous, transparent haze appears on the horizon.

Without absorbing the forms, it pleasantly softens all sharp

outlines in its dreamy embrace.

The cart-ruts, glittering in the sunlight, run in two parallel

lines over the hard trodden road ; and on either side, from the

tops of the trees, in the silence of the calm, and the splendour

of the gently loosening sun, small white flakes of rime slowly

descend.

The row of gradually undulating hills, sloping away into the

distance, bright in places with grey uneven snow-plots, looms

in the shadowy violet dimness against the sun-drenched haze.

Before the walker’s feet small crested larks, plump and tame,

hop about, every now and then flying short distances and

boring into the hardened layer of snow. Greedily they peck

24

with their little bills, these tiny town-marauders tamed by

winter.

The steam-tram, with a hollow rattling, rushes along the

glittering rails. For a considerable time its crest of steam

remains hanging in the white net of branches, entangled in

them like a flimsy cobweb veil. The impetuous bound of its

course sends a short shudder through the tawny, withered

oak-groves by the roadside, startling them for a moment from

their rigid repose.

III

A hazy sun-blot, dimly shimmering like tarnished brass, is

lingering still in the western sky. Beneath it stretches a

narrow band of yellow-red, whose hues gradually fade and

dwindle, passing on either side into pale grey. On the lower

skirt of the sky, descending to the earth, is seen a purple-grey

pile of clouds, upon which the trees of the horizon — faint,

spectral skeletons, misty like the images of a dream— raise their

lank shapes.

On the left, by the side of the fading edges of the bright band,

there appears, only just perceptible against the almost equally

tinted sky, the ridge of hills ascending and descending in even

slopes. The hills themselves have a more compact, purplish-

grey tint.

Further down, interrupted here and there by a projection, and

grooved with ditches, which glare yellow-light in the monotony

of the white expanse, like tramrails lit by the fiery eyes of the

engine, a great white plain extends as far as the main road.

The bark of the birches, at other seasons so glittering, appears

sallow and dull amidst the snow accumulated around the tree-

roots, and their overhanging, hairy boughs, delicately twined

against the grey-blue upper sky, move with a faint quiver.

At some distance stands a grove of fir-trees, those harps of the

winter wind, when with a wailing rustle he sweeps through

their stately branches.

Toy-like, as if a child at play had placed them at random,

white-roofed cottages far away lie scattered.

25

And, in the foreground, close to the road, the faint gleam of the

dying sun, wearily descending into a pile of clouds, glides over

the silent, velvety snow-field.

IV

Brightly the sun has its play on the blanched plain ; when the

radiant sunlight meets the crystals, thousands of diamonds

sparkle up out of the white monotony. Then their facets

glitter in lustrous splendour like the clear touches of the sun

on a sheet of water, and all the wide white surface is alive

with a tremor and gleam of radiance which seems to shoot up

and hover in the air, filling all the broad expanse of ether with

an aureole of crystalline scintillation.

In some places a broad stream of golden light flows over the

snow-field, while the shadow of a slight cloud suddenly passing

over it dims, as if suffused with a breath, the dazzling splendour

of white and crystal. And round the blue-grey range of hills on

the horizon, above which the sun spreads its lustre, a golden

band runs like a diadem around the head of some stern old

king.

The snow crackles under the feet, and the winter wind sends

its low-moving gusts over the landscape. On every side, as

far as the eye reaches, snow, snow, snow. Everything is white

except part of the trunks of the trees, and the walls of the farm-

houses standing out like dark blots of shadow between the

sparkling white of the snow and the sparkling blue of the sky.

So, surrounded by winter’s jubilee, inhaling the cold, dry,

subtle air, and crushing the frozen snow under my feet, I

proceed. The snow creaks and crepitates, and, after my

treading it down, remains flat on the ground with a last half-

groaning sigh, as if it would reproach me with violating its

white smoothness and disturbing its icy repose. My cheeks

feel the pure, ice-cold breeze, the blood-strengthening, nerve-

bracing exhilaration, the fresh essence of winter.

And, walking on, I come to an orchard whose trees are wholly

white, the trunks painted white by human hands, the branches

26

and twigs hoar-frosty by the work of winter, so prodigal of

white. One of them is strangely formed, like a hunch-backed

dwarf, with its fantastically distorted, undergrown trunk, and

its branches horribly wrenched and twisted, like the massive

white skeleton of some wondrous monstrosity which has lost

itself and wasted away in a winter garden of fairyland.

And with every strong gust of wind a shower of white, tiny

flakes comes down from the trees. First they hover hesitat-

ingly in the air, hanging ‘twixt heaven and earth, then slowly

descend and quietly settle down on the ground.

Heavily thundering over the groaning rails, a long railway train

is with violent puffs of steam just slowly passing by the barrier.

First the steam shoots straight up into the air like a nebulous

geyser-spout, a fountain of sun-golden mist, whose extremities,

hued with fire-yellow topaz, encircle a nucleus of dull amethyst.

And, suffused with light, slowly the steam-cloud extends, but

continues lingering over the dark train, that, with grim grinding

of axle-trees and perches, creeps slowly along.

V

Faintly blows from afar the winter wind, with long-drawn

breathings, that cause an idle flapping of the withered leaves

against each other as they whizz among the sere-leafed shrubs.

Slowly the rime-laden branches of the fir-trees, stretched out

like solemnly blessing arms, are moving up and down.

Upon all the country the thick winter fog has settled, weighing

down everything with its mass of moisture, vaporising the

distant trees, and absorbing the thin extremities of the branches

in its densely clinging veil. Dreamily the white roofs of the

farm-houses dwindle in the mist. Cold grey, the sky vaults

the tawny land.

Leaning against a hill, and looking like grotesque giant-crests,

the black-green pine-trees stain dark tints in the white. The

slender entwined twigs of the hedge, set with pure rime,

resemble a broad lace garniture fringing the snow-covered

27

ground. And beyond there is everywhere the close mantle of

snow, uneven with trees and slightly waving stems, decked

with wind-blown, fine, white-feathered plumes, clothing the

ribbed bands of the earth.

In a fallow field, working the hard frozen soil, men come into

sight. With long-drawn strokes of the mattock one of them

sturdily loosens the stubborn glebe. With their spades others

are throwing the sandy lumps in heaps, and darkly they stand

out against the whitish background like dim magic-lantern

shadows, cast by a faintly burning wick. Under the fog,

which dims the objects and penetrates them with its chill,

wet breath, everything lies hushed and quiet.

EDWARD B. KOSTER.

WINTER

THIS is no weakling pale

Driven before the gale,

A strong one he, as giant Ophero

Who bore the wayfarer upon his shoulder,

His shoulder mighty as a mountain boulder,

And from happy shore to shore

Carried him safely o’er

The turgid torrent, even so

Doth sturdy winter come and go,

To cross a strait,

And landing them where they may run

To overtake the sun.

The bridge of his great arm

Rescueth from harm,

His freezing grip

Warmeth the blood,

The kiss of his cold lip

Is good

For stinging vital sparks to fire,

And wholesome in a frail world is his despotic ire.

29

Winter, with limbs bare and brown,

A furred skin on his shoulders thrown,

Driving the gales he hath come swiftly down

Behind the sea-gulls that have landward flown:

Music from his mouth

Blowing, north to south,

A leash of whirlwinds in each ruthless hand

To let loose o’er sea and land.

Good ships, fear ye him

When days are short and dim,

Demons of the air,

All baleful things and grim,

Of him beware,

The purifier,

Of him, the thurifer

With thurible of frost and fire,

Scattering the seedlings of a white desire

As swift he goes

Amid his frosts and snows,

Keen of eye and strong of limb,

Cleansing the world with righteous wrath no poison

can withstand.

His dark head white starred with frost

Moves amid the racked and tost

Boughs of the disgracéd trees,

Suffering mysterious penalties

For sins of which the legend is long lost,

For he hath them in ward

And doth their secret guard,

He hath stripped them of the royal cover

Summer gave

When each brave

Tree of the forest was her lover,

And the gold

Flung to them by autumn’s grace

30

He will take and hold

Down in a dark place,

For he hath got the key

Of the earth’s treasury.

Hid within the deeps

Of Nature, where she keeps

In long unconsciousness her darling rose,

The pear that golden grows

When the sun hath found it

With reddening leaves around it,

Hath with delight caressed it

And for sweet uses blessed it.

Far down in the darkness where the seed sleeps,

And into which the long rain weeps and creeps,

Doth winter hoard up gems,

Coronals and diadems

For beauteous daughters that will yet be born

On many a radiant morn

Winter will never see

When the queen Summer shall

Hold her high festival,

Ruling by love a raptured world on flowery hill and lea.

When the ascending sun

Signalleth his race is run,

Whither goeth he?

Folding up his tent of snow,

Taking the mountain tranquilly?

Where?

Lifting his bugle once to fling

On the air

A silver call to waken Spring ?

Doth he straightway go

Out amid the stars from yonder peak,

Still offering his service to the weak

31

In spheres we do not know,

Where things faint to death,

Languish for his ice-cold breath

Bringing vigour to their veins?

With his hand upon the reins

Of the storm-wind he will come

Back to us when woods are dumb,

When our summer glory

Is departed, when the story

Of the nightingale is told,

And no more is autumn gold,

In the misty morn

We shall hear his lusty horn

Blowing, and our eyes see fain

Ice-tents glittering in the plain.

Then shall hearts be glad, and say

The roses have another day

To live, for lo, the strong one’s at his mighty work again!

ROSA MULHOLLAND.

A WINTER HARVEST

BY A. G. SINCLAIR

FANTASIES

I

A YEAR AND A DAY

ONE November day, when they had been married

about a twelvemonth, there came to the door a

strange-looking girl and asked the master if they

were in want of a servant.

The mistress had just had her first baby and was

still weak, though her heart was good, and the

master, after asking the girl a few questions, said to the mis-

tress, Well. . . he thought they might engage her.

‘I don’t altogether like her look,’ said the mistress; for the

girl’s peaked face was so white and still that, if it hadn’t been

for her eyes, one would have taken her for a corpse.

‘I can sew and knit, and there isn’t a bit of housework I can’t

manage, and I can milk and make butter with the best,’ said

the girl.

And the master remarked again that he thought they might

try her; she seemed to be strong and willing, for all she looked

so pale.

‘And I love children,’ added the girl, glancing wistfully at the

baby; ‘I can quiet them however fretful they may be.’

The infant in the mother’s arms had been crying lustily for a

minute or two, either from wanting the breast or for some other

reason, and hush it as she might the mother couldn’t quiet it.

But now the girl fixed on it her great, mournful eyes and

began to hum softly some old-world lullaby; and almost as soon

36

as her lips began to move the little one blinked and closed its

eyes, and there it lay peacefully asleep.

That settled the matter as far as the mistress was concerned.

‘Well, I’m willing to engage you,’ said she to the girl.

But the master said nothing. He was watching the girl

strangely out of the corners of his eyes.

‘If you engage me,’ said the girl, ‘it must be for a year and a

day.’

‘Very well,’ said the mistress, who was admiring the baby

sleeping so peacefully in her arms; ‘and what wages will you

want?’

‘Oh, I don’t want money,’ said the girl carelessly. ‘Let me

have anything that may take my fancy on the night I’m

leaving.’

‘Very well,’ said the mistress, ‘I’m agreeable to that.’

‘You agree to it too?’ asked the girl of the master.

‘Yes. . .I agree to it. . . if the mistress does,’ said he. And

all the time he couldn’t take his eyes off the girl. ‘What ‘s your

name?’ he asked her, watching her closely.

‘Piggy-widden,’¹ said the girl.

‘What a ridiculous name for a servant,’ said the mistress. ‘I

shall call you Peggy,’ said she to the girl.

The girl glanced at the master; but the latter held his tongue:

so Peggy she became without further protest.

Peggy proved a perfect treasure in the house: early and late

she was scouring and cleaning, and it was impossible to find

fault with her in a single thing.

Or, at any rate, so the master thought. But the mistress

thought the girl looked too often at the master (who had been

a bit wild in his day, though he had sobered down since his

marriage), and though the master said nothing, she was not far

wrong.

Go where the master would the girl’s eyes followed him. Yet

she never addressed him, unless compelled to do so, and made

¹Piggy-widden=little white pig, is in Cornwall a term of endearment for the last-born

in a family.

37

no attempt to attract his attention. Always sparing of her

speech, and always with that deathly pallor on her countenance,

the girl moved about as noiselessly as a ghost: her great, mourn-

ful eyes apparently fixed on vacancy (unless the master happened

to be near), and all her faculties seemingly sunk in torpor, except

for the mechanical needs of the moment Yet the master

seemed oddly attracted towards her. His eyes sought her still,

white face persistently, whenever he was anywhere where it was

possible to get a glimpse of her; and when their glances met,

the girl would hold him with her eyes with a control so uncanny

that the master would shiver chilly, as if ice were in his blood.

At last the term of the girl’s engagement drew to an end: on

the morrow she would have served them a twelvemonth and a

day.

As she sat by the big turf fire in the evening, playing with the

baby that crowed upon her lap, the wife began to speculate, with

languid indifference, on what the girl would ask for her wages.

Would it be clothes, or china, or goods from the linen-chest?

Or perhaps it would be the baby’s silver christening-cup, which

she had once or twice seen the girl examining when she was

cleaning it? Well, anything, even the cup (though she would

be loth to part with this), would be cheap as payment for the

girl’s services, for a better servant, as far as work was con-

cerned, she could never hope to get. And with that she pro-

ceeded to give the baby the breast, and lazily dismissed the

subject from her thoughts.

On the morrow came the girl’s last day at the farmhouse; and

it was All Souls’ Eve, and a wild day to boot.

‘A poor day for the end of your engagement,’ said the mistress;

‘where are you thinking of going to when you leave us?’

‘To my home,’ said the girl.

‘And where is that?’ asked the mistress.

‘Maybe you’ll be coming there one day,’ said the girl. ‘I think

I’ll keep its name as a surprise for you,’ said she.

‘Oh, very well; as you please,’ said the mistress. ‘And what

do you want for wages?’ she asked her presently.

38

And at that moment the master entered the kitchen.

‘Only a kiss from the master,’ said the girl.

‘You bold young hussy!’ cried the mistress furiously. ‘Get

out of my house this instant, or I’ll sweep you out with the

broom!’

‘I have served a year and a day for my wages,’ said the girl,

‘and the master will pay them honestly’; and she held him with

her eyes.

‘He sha’n’t!’ cried the mistress, rushing between them.

‘He will,’ said the girl, in her dull, lifeless tones.

And immediately the master thrust his wife aside and kissed the

girl on her unresponsive lips.

‘Now, he’s mine!’ cried the girl exultantly: her white face

turning to the colour of clay.

The mistress fell back from her with a look of horror; but the

master stood still, staring in her eyes.

‘Are you Eileen, then?’ asked the master, shuddering.

‘When the time came I thought you would know me,’ said the

girl.

‘But Eileen died. . . .’

The girl fixed her eyes on him steadily.

‘And who says that I am not dead?’ asked the girl.

And at that moment the windows and doors began to rattle, as

if unseen hands were busy with their fastenings.

‘My year and a day is up: I am wanted,’ said the girl. And

she held out her cold, white hand to the master.

The man took it mechanically, and his face began to pale.

‘Come!’ said the girl, and the door flew open; a sudden icy

gust blowing through the kitchen so that the lights went out

and the child began to wail.

‘It is cold,’ muttered the master, as she led him to the door.

‘It will be colder where we are going,’ said the girl.

‘It is dark.’

‘It will be darker where we’ll have to sleep together.’

And out they went into the wild, mirk night.

39

II

AN ODD COINCIDENCE

ONE moonlight night, as Abe Chynoweth and his

comrade Joe Branwell were whiffing for mackerel

between Treen Dinas and the Runnelstone, Abe

Chynoweth, in a struggle with a powerful conger,

unfortunately overbalanced himself and plunged

headlong into the sea.

The sullen waters closed over him with an angry growl, as if

the old Sea Mother had gotten her prey at last and snarled her

satisfaction as she savagely dragged him down, and Abe, with

the waters sounding in his ears, as though the world were

drifting, drifting away from him, felt the solemnity of death fall

suddenly on his thoughts.

The next moment, however, he was surprised to find himself

flung violently on the strand, the huge waves grumbling and

rumbling as they sullenly recoiled from him.

As he rose to his feet he perceived a large black boat beached

on the sand about a dozen yards away from him; and the oddity

of her appearance at once set him wondering.

To his eyes—but perhaps it was the salt water still smarting in

them—she seemed like a monstrous black coffin, fashioned pre-

cisely on the same lines as the latter, and as sinister and gloomy

in the memories she awoke. To add to the strangeness, she had

a stunted mast carrying a square black sail, and in her bow

stood a lean, dwarfish figure, with a face whose pits and hollows

were so extravagantly accentuated that it resembled nothing

so much as a skeleton’s.

While Abe stood gaping at the boat with a strange shivering,

which he found it quite impossible to control, he could hear the

bell on the Runnelstone tolling solemnly as the heaving surges

swung it sullenly to and fro, and on the beach the waves

moaned eerily all the while.

40

Suddenly the odd little figure in the bow of the boat put a horn

to his mouth, and blew a long, wailing blast.

A sound more drearily mournful Abe had never heard; it was

as though the weepings and sobbings of unnumbered genera-

tions were concentrated in their sorrow in that long, deep

wail.

As the last dreary note died away mournfully, Abe was aware

of a string of shadows descending to the cove through the deep,

black cutting that led up the cliffs.

Strange indeed was the procession; its like Abe had never seen.

The thin, misty shadows, as tremulous as wisps of vapour, yet

with their lifelong identities wrought into them indelibly,

appeared to be filled with the most agitating sorrow, to judge

by the wild abandonment of their gestures, yet from the long

procession winding down the beach not a single sound rose

into the air. It was all as silent as if Abe had been looking at

a picture, and the terror of the dumb scene chilled him to the

bone.

In the throng of shadows Abe scanned the faces curiously, but

with the curiosity of a terror that oppressed him like a night-

mare, and his heart seemed to swell and ache as he scanned

them.

One after the other, and still in silence, the figures entered the

boat, wringing their hands helplessly, and Abe watched them

with the blood congealing in his veins.

Suddenly he perceived among the gliding throng an ashen-

faced, wet-eyed, frightened little child, her tiny feet showing

beneath her long white night-dress, and her wee hands clutch-

ing at the skirt of a woman in front of her; a great, dim terror

evidently bursting her little heart.

In an instant Abe recognised his own wee daughter, and with

the great and mighty cry of a parent’s anguish—so loud, so

deep, so appallingly poignant that even the lean white figure in

the boat started visibly—Abe darted forward to clasp the little

maid.

But it was too late.

41

Just at that instant the figure at the bow of the boat uttered

another long, deep wail through his horn, and the ghostly

procession drifted into the boat: drifted into it so rapidly

that Abe, rushing after them, found the last thin shadow already

in the boat and the latter floating outwards into the grey

immensity at the very moment that he arrived at the edge of the

water.

Across the side of the boat his little daughter leaned implor-

ingly, her blue eyes entreating and full of the agony of separa-

tion—her dumb appealing cutting him to the heart.

Into the waves Abe rushed, regardless of their depth, following

the retreating boat with passionate despair.

Up crept the waters to his waist, to his shoulders—up to his

neck, to his chin, to his mouth—till at last he was struggling

chokingly in the flood, his hands thrown up and the waters

deepening above his head.

. . . ‘All right agen, Abe?’ a voice called to him suddenly;

a voice from somewhere out of the depths of his past, dead

life.

Abe opened his eyes feebly, and saw Joe bending over him as he

lay in the bottom of the boat with the water streaming from his

clothes.

‘So close a shave as that I never seed!’ said Joe. ‘Thee went

down like a stone. Thought I should never git’ee aboard

agen. Thee’rt lookin’ whisht,¹ sure ’nuff. Feelin’ all right?’

Abe sat up with an effort, and gazed around dazedly: his eyes

sweeping the horizon in every direction.

There was nothing to be seen except the headlands black in the

moonlight and the shimmering track of silver across the water;

and nothing to be heard but the weary rumour of the waves,

and the slow and heavy tolling of the Runnelstone bell.

‘Feelin’ all right agen? ‘Joe repeated.

‘Iss,’ said Abe slowly; ‘iss, b’leeve I am.’ Then shaking the

water from him, with his tanned and bearded face looking

ghastly in the moonlight, he remarked to Joe, ‘I must go

¹Mournful, or melancholy.

42

ashore, you; caan’t haul anawther line to-night for the life

o’ me.’

Joe tried to argue with him, but it was quite useless. Abe

protested that ashore he must go at once. Good catch or bad

catch, he couldn’t help it: he must go.

In the end, Joe began to suspect that his comrade had had his

nerves unstrung by his sudden plunge overboard; so he sub-

mitted to the inevitable with the best grace he could, and,

hauling in their lines, they rowed ashore.

Immediately the boat’s bow grated on the beach Abe jumped

out into the shallow water. Splashing through the frothing edge

of the waves, he hauled the boat high and dry on the pebbles

almost before Joe could collect his wits. Then waving his hand,

with a shouted ‘Good night, you!’ he strode off grimly, with his

head on his breast.

As he laid his hand on the latch of his little thatched cottage,

one of the neighbours came out of her house and hurried

towards him.

‘Beer up, Abe, for the sake o’ thy wife!’ said the grey-haired

gossip, eyeing him anxiously.

‘What es it? Wha’s wrong?’ Abe articulated hoarsely.

‘She’s gone, li’l dear! Failed ower cleff, playin’ weth her dolly.’

The crabber abruptly turned his face away from her.

For a minute, perhaps more, he fingered the door-

latch. . . it was lifted from within, and he passed

silently into the house.

J. H. PEARCE.

WHEN THE DEW IS FALLING

WHEN the dew is falling

I have heard a calling

Of aerial sweet voices o’er the low green hill;

And when the moon is dying

I have heard a crying

Where the brown burn slippeth thro’ the

hollows green and still.

And O the sorrow upon me,

The grey grief upon me,

For a voice that whispered once, and now for aye is still!

O heart forsaken, calling

When the dew is falling.

To the one that comes not ever o’er the low green hill!

THE MOTHER OF JESUS

IT was night in the little thatched house by the roadside.

The last cart had creaked on its homeward way, and

silence had fallen on the house, silence broken now and

again by the sharp cry of a child in suffering.

A group in the kitchen gathered around the smoulder-

ing turf-embers, and talked in subdued voices. Over

all these lay the hush of expectation that comes before a death.

The neighbour women had been in and out all day, but now as

the time grew shorter they had left the mother with the child,

alone but for her old mother, who sat on a creepy stool by the

hearth and watched both with eyes of suffering.

When the child cried the young mother drew a sharp breath as

though she endured intolerable suffering in silence. They were

saying down in the kitchen that the baby was too young to

have laid hold upon her life, but to her he was as much a

human personality, loving and understanding her as though he

were a man and old.

‘Oh,’ she said, when once again the child cried, ‘if he is not

to live would I keep him to suffer? Oh, why must he suffer, he

who has never known sin?’

The old mother made no answer to the unanswerable question.

‘Pray, jewel,’ she said;’ there is great power in prayer. Many

a child have I seen given back that was farther gone than he.’

45

‘If prayer could keep him I should never do anything but pray

again,’ said the child’s mother, but no spark of hope lit up her

hopeless eyes.

‘Whisht, dearie, whisht! Pray that the will of God may be

done in regard to him.’

‘I cannot pray. What am I to say to Alick when he comes

back and asks me for his son?’

‘He will comfort you, and love you better because of what you

suffered without him.’

‘I was alone in the terror before he was born. I was alone in

my agony, but afterwards I had the child. Now I shall be

more alone than any woman in all the world.’

The old mother winced.

‘You have your father and me. You were our darling before

you ever laid eyes on Alick McCarthy and his fine red coat.’

The girl did not seem to have heard her. She was watching

the tiny face on which the shadows were growing darker.

‘He is easier, I think.’

‘The pain is leaving him, acushla,’ said the old mother, her

eyes full of a deeper pain.

‘His breathing is easier. Oh, what it would be if he could live!

I think I should die of joy.’

‘Pray, child!’

‘Mother, God is powerful and kind. Do you think if I could

give Him the child up that He would give him back to me?’

‘If He saw it was good, child. He can do better for him than

you can. If He takes him, it is in love.’

‘But He cannot want him as I do. I would rear him to be a

good man.’

Her eyes prayed for hope to be given her. The old mother

came out of her corner and looked at the child.

‘Give him to me for a bit, and do you go to the altar in the other

room and pray. Rest if you can, child. I am troubled about

you, for ’tis only a few weeks since you left your bed. Give him

to me; I will call you if there is any change.’

The young mother let the child be taken from her knee. He

46

still lay quietly without a moan. In the dark room adjoining

one little star of light quivered. It was the lamp before Our

Lady’s Altar.

The statue glimmered whitely above it. There was a handful

of flowers set on each side in poor little vases. The arms of the

figure were outstretched benignly, and the head was bent a little

forward.

A sense of rest and quietness came over the young mother.

She knelt at the foot of the statue, and rested her cheek against

the linen altar-cloth. In the whitewashed wall a death-watch

was ticking monotonously. She put her hands to her ears to

shut out the sound, and began to pray.

Now that the suffering child was no longer before her, she

prayed with passion. She reached out her hand and clutched

at a fold of the statue’s garments as though it were a living

woman.

‘You saw your Son die,’ she cried, ‘but He was with you three-

and-thirty years. You nursed and fed and washed and clothed

Him. You had all that joy. Ask Him to spare me mine,—if it

is His will, if it is His will.’

She added the words with difficulty, hardly as if her heart were

in them, but she felt that if she did not say it her prayers would

have less chance. She lifted up her head and prayed with

exaltation. She lay at the statue’s foot, and prayed with

anguish. She was so still that the old mother in the next room

said to herself—

‘The Lord has sent her rest and sleep to strengthen her against

what is coming. Blessed be His Name.’

How long she prayed she knew not. Once, when the silence

in the other room had lasted long, the thought came to her

that the child was dead.

She thought in a strange, stupefied way of how Alick would

hear it. Would it be at night in the barrack-room with the

ribaldry and jests going on about him, or would it be in the

morning as he came from parade all gay with the soldierly

smartness she loved in her hero? Would he think she had

47

been careless of the child and let him die, or would he wish

he had married that other girl who was noisily full of health

and life, and would have given him strong children? She was

paying the price of her delicate, nervous prettiness, which had

made her a pet with the officers’ wives, and something infinitely

precious and perdurable to her young husband.

Then another cry broke the silence, one thinner and more

feeble than before. Her heart came out of its sluggish lethargy,

and she would have sprung to her feet and gone to the child,

but a strange thing happened. ‘The arms of the statue had

closed about a baby, and the baby was her own little one that

lay dying a few feet away.’

A moment, and she went back to the cradle-side, and stretched

her arms mutely for the child.

‘Bear up, acushla,’ said the old mother; ‘he’s going fast.’

‘I wouldn’t keep him,’ she said, ‘now that I know what he’s

going to.’

Her voice was low and intense, but so new a tone was in it that

the old mother looked at her with alarm. Then she nodded

her head, reassured.

‘The grace of God has strengthened you,’ she said.

‘Yes, the grace of God,’ said the young mother, coming to

the child as if he were but sleeping.

KATHARINE TYNAN.

MADONNA AND CHILD WITH ST. JOHN

BY ANDREW KAY WOMRATH

SYMBOLS

SPLENDOUR of dawn on the hills, in the rose-coloured

blossom of morn;

Splendour of moonlight unmuffled and glassed in the

shimmering sea;

Splendour of melody rolling on surges of harp and

of horn:

But the splendour of sunset on cloud is the symbol of splendour

to me.

Glory of legions embattled, with wind-blown banners for

wings;

And of brows that are laurelled and lit with the vision of glories

to be;

Glory of birth, and the blazon of heralds and triumph of kings:

But the glory of grass on the grave is the symbol of glory to

me.

Beauty of noon in the cloudless blue and the full-blown flower;

Beauty of minds that are pure, and beauty of souls that are

free;

Beauty of woman unveiled in the bloom of the Lesbian bower:

But the beauty of love in the bud is the symbol of beauty to

me.

52

Sorrow of hopes unfulfilled in the blight of unholy desire,

And voices of love that are hushed in the shade of the church-

yard tree;

Sorrow of sins that grow black in the flame of the cleansing

fire:

But the sorrow of wasted youth is the symbol of sorrow to me.

Mystery of wings that are furled in the flesh of the grovelling

worm;

Mystery of wisdom that slumbers embalmed in the cell of the

bee;

Mystery of fragrance and colour congealed in the core of a

germ:

But the mystery of life from the dead is the symbol of mystery

to me.

W. J. ROBERTSON.

FROST

QUIETLY the snow fell, in large soft flakes which

floated in the still air. Janet stood at her

window and looked helplessly at the stealthy

narrowing of the familiar horizon. The oppres-

sive stillness of the clouds had waked her early;

and, as she dressed, she watched the drifting

flakes. Now they fell faster, thicker. The grey veil gradu-

ally drew its folds over hill and valley till the girl’s outlook

was narrowed to the garden wall with its irregular line of

trees. The desolation of the scene sank deeply into her mind,

and intensified her despondency. The grey outer world with

its obscure horizon, its immediate limitations, seemed to sym-

bolise her own life, to echo her present mood. Janet turned

and surveyed the sombre comfort of her room wherein she

had lived so much of her twenty-two years. Familiarity had

dulled her perception of her usual surroundings; but, to-day,

the unloveliness of her room, of the whole house, jarred on her

nerves acutely. Greyness, she realised with a shiver, was the

prevailing tone in her life, despite her many resolutions, her

fitful efforts to colour it afresh, to make it fuller and more vital.

No prince, alas! had kissed her sleep into throbbing wakeful-

ness. Yesterday’s lurid sunset had aroused afresh her flagging

determination to control the tenour of her life, and no longer to

be the slave of her environment. This morning, the remorse-

54

less snowflakes wove a pall over her starved hopes, and froze

them into inanition.

‘Janet,’ a gentle old voice cried from the staircase, ‘your break-

fast will be cold if you do not come!’ and the girl, quitting her

window with a sigh, entered upon the day’s routine.

It was in an old manse, in a quiet northern strath, that Janet

lived with her grand-parents. Her grandfather had ministered

to the scattered souls of his parish for over fifty years, in his life

illustrating the love of God, and preaching of the wrath to come

from his pulpit. The children born in the old manse settled

elsewhere, and Janet’s parents had sent her from India to her

grandmother’s fostering care when she was five years old.

As a child she ran wild about the garden, in fields and woods,

and by the rocks on the river. But as she grew out of child-

hood, the requirements of social decorum were laid upon her

by an instructress who strictly debarred her from the com-

panionship of her cotter playmates. Conventional restrictions

sowed seeds of dreariness early in her young life, whose imposed

boundaries narrowed in proportion as she grew old enough to

understand the increasing needs of her nature. Her home,

once her kingdom, became her prison; and she hailed with

joy the day that saw her conveyed to a boarding-school in the

nearest town. Here, at least, she gained companionship; at

least she saw an aspect of life different from that in the familiar

strath. Here, too, was new ground whereon to raise castles in

the air; here were new materials, in part furnished by her

companions, wherewith to build. The future surely held

enchanting possibilities and adventures in keeping for her.

India, at all events, was a promised land of vaguely remem-

bered brightness to which she should return.

But with the ending of her schooldays came the first crumbling

of Janet’s dreams. An epidemic of cholera robbed her of both

her parents and of her sojourn in that ardently longed-for land

of sunshine and of love.

The grey old manse in the north-east of Scotland was hence-

forth to be her home, varied only by visits to schoolfellows in

55

Edinburgh, or to an aunt in the bewildering city of London.

Her dream, too, of being a painter was shattered by her

grandfather’s unconquerable prejudice against the preparatory

student life away from home control. ‘Paint by all means,

child, if it amuses you; but paint here. I have heard dreadful

tales of student life in London and Paris, and dare not take so

great a responsibility on my conscience, or allow you to run

such terrible risks.’

So the weeks passed in an ever-growing monotony; and the

young life began to falter for lack of vital nourishment. The

prevailing silence, broken only by the sound of a cart-wheel or

the lowing of a cow, or rendered more audible by the sudden

cawing of the rooks, weighed on Janet’s spirits. The lack of

young companionship depressed her; the inadequacy of her

daily duties rendered them distasteful to her; the lack of

mental outlook and stimulus starved her intellectually.

Springtide brought fresh hope, fresh vigour; the summer,

with its flowering beauty of field and hill, fresh joy. With

autumn came the sportsmen, and for a short season the

countryside was gay. Janet utilised the warm bright days

in trying to find a way of putting upon canvas her impressions

of green summer and ruddy autumn, for a solace throughout

the long winter and a promise of the spring to be. But with

the fall of the year her ardour waned, her courage dissipated.

The dull quiet, the chill greyness of winter with its steely sun-

shine, ate into her life and robbed her of all impulse. Against

the winter lethargy she fought fitfully but unavailingly.

Janet’s breakfast greeting on this snowy January morning was

of a kind she little expected.

‘Well, dearie, here’s news for you—for granny and I have quite

made up our minds about the matter. You have been ailing

all winter, and now an unlooked-for chance has come to make

you well again.’

The girl’s heart leapt, and the colour rushed into her pale face.

Any change would be an unspeakable relief to her.

‘Your aunt has written to tell me that she and your cousin are

56

going to Rome for three months, and she is quite pleased that

you should go with them. Three months in Italy ought to

make a strong girl of you; and you will come back to us in

April with the spring flowers.’

. . . . . .

Every incident of the journey was an excitement. Dreamland,

hope, desire, lay before her. The morrow was no longer a

barren waste bounded by a narrow horizon. Her way lay now

through the unknown, whose sign-posts she could discern

faintly in the flooding sunshine. The minor discomforts of

travel Janet welcomed, for they suggested a practical aspect

of dreamland to which she had never given a thought.

Genoa was the first halting-place. Genoa, the great amphi-

theatre of Ligurian prosperity, with its tier above tier of

Oriental-looking houses flanking the tree-clad hills, and

separated from the crescent bay by its white marble quay.

The great cool palaces; the luxuriant foliage dotted with

pendent oranges and warm-red roses, and pierced by feather

fronds of palm-trees or the spiky growth of cactus and of aloe;

the great harbour with its shipping, the blue-green waters

alive in the sunlight;—these things awoke in Janet’s brain

forgotten memories and mental pictures of an Oriental city

girt by its great harbour, rich, too, in colour, and full of strange

forms and features that long ago, in early childhood, had been

familiar to her if then unnoted.

Rome was reached in the early morning, and the girl’s first

vision of the great city was from the terrace roof of her room

high above the Spagna steps. There she stood motionless,

breathless almost, as she watched the delicate dawn-mist float

away and reveal countless domes and spires, and beyond

these the Alban and Sabine hills, as the sun rose above the

Apennines and turned the quiet twilight into the radiance of

morning.

Day by day the beauty and effluence of the southern winter

awoke a deep and eager response in Janet’s nature. She

became conscious of new needs, new desires. Already the

57

cramping influence of familiar parochial life was melting in

the cosmopolitan breath of the eternal city. Janet scarcely

recognised herself as the old landmarks vanished; she felt

happy in this sun-swept, but, to her, pathless land. Her

ignorance appalled her; her insular and Puritan prejudices

were perpetual stumblingblocks which met her with fatiguing

monotony. The artistic side of her nature, however, expanded

joyously in the congenial environment. So keen was her

pleasure, she did not realise how the outward tenour of her

sojourn resembled that of every ninety-and-nine tourists to

whom Baedeker is an infallible guide. To Janet, Rome was a

newly discovered country, and she found herself full of unrecog-

nised possibilities. Ruins, galleries, churches, were visited in

due course. Much as these interested her, she loved best of

all to escape alone to the Pincio and gaze over its ilex-shaded

parapet at the city below; to watch the endless coming and

going of smart carriages, or the strings of collegiates, in their

distinctive soutanes and hats, wind along the pathways; or to

saunter towards the Porta del Popolo and feast her eyes on

the moist greensward and the fresh foliage of the exotic trees

which make a summer of the Roman winter. And how beautiful,

too, in the early mornings was the Piazza di Spagna, abloom

with sprays of early blossoming shrubs—wattle, with its per-

fumed golden balls; eucalyptus, with its thin, scimitar-shaped

leaves; roses and violets and narcissi, till the fountain in the

centre seemed to spring and sparkle from the heart of a flower-

garden.

The churches with their wealth of mosaics and paintings, their

coloured trappings, their strange, picturesque ceremonies,

attracted yet repelled Janet. Her sensuous impulses rebelled

desperately against her religious convictions, trained as she

had been in the severe Calvinistic atmosphere. The harsh

unloveliness of the little strath kirk had always been dis-

tasteful, though she loved the austere purity of her grand-

father’s teaching. Here, in Rome, the aesthetic attractions of

the great churches affected her profoundly by their subtle

58

suggestiveness, by their repose; but their religious appeal left

her unmoved, or frankly hostile.

In the hotel she made few friends. The girl’s natural shyness,

increased by the remoteness of her home, was a constant barrier

to social intercourse. At table her position between her soci-

able aunt and cousin relieved her, she felt, of the necessity of

continuous talking, and leisure to watch and listen unheeded.

The three months at length drew to a close, the longest and

most eventful of her life. As Janet stood on the terrace roof

for the last time, and watched the sun set in flaming crimson

and orange, against which the dome of St. Peter’s stood out-

lined in sombre purple, she sighed farewell to the mysterious

Campagna beyond, to the ancient city at her feet. She knew

that her regret would grow into an ever-deepening longing

as time drifted her further away from this flowering oasis she

had chanced upon in the colourless desert of her life.

. . . . . .

The elation that Janet had brought back with her from Italy

lasted throughout the ensuing summertide. The beauty of the

summer, the rich fruition of tree and flower, the mantling

green, gold, and purple of hill and vale, Janet saw through eyes

wherein lingered the glamour of the southern land she had

left. Nevertheless, it was a shock, on her return to the old

sleepy manse, to find neither stick nor stone out of its accus-

tomed place, to see nothing altered in any one or anything that

answered to the wonderful change she felt in herself. Nothing

differed: the same voices, the same routine, the same daily

remarks, just as she remembered them ever since her child-

hood. Yet not quite the same. A curious shrinkage seemed

to have taken place. The greater world outside this familiar

daily life made the smaller world grow smaller still, showed it

by comparison to be antiquated, asleep, left behind by the

great wave of extension and expansion.

Losing sight of the warm human hearts that beat in the little

strath, of the equality of suffering it shared with the rest of the

world, Janet felt herself chilled to the heart by its parochialism,—

59

in other words, by the absence of any definite outlet for her

unsatisfied and untried possibilities. The even tcnour of her

life had been abruptly confused by her visit to Rome. An angel

had stepped into the quiet pool and had troubled it; but alas!

the waters were gradually settling once more into stagnation.

Would no lasting good remain?

One by one the autumn sportsmen and their visitors left the

neighbouring hills, and the strath resumed its normal unevent-

fulness. Was there no escape? Should she not go back to

Rome, or even to London, and learn to paint? She was of age,

should she not choose her own course of life? But whenever

this suggestion created an alluring picture in her mind, it was

immediately effaced by another—that of two wrinkled, pathetic

faces, of two frail old bodies awaiting the close of their tired

lives. This picture seemed to Janet to leave her no alternative.

Clearly she realised her present duty, and accepted it; but the

blight of bitter regret and futile longing withered the delicate

tentatives of her heart.

Autumn faded into barrenness; the leaves lay brown and sodden

in the strath. Here and there a straggling bunch of mountain-

ash berries gleamed scarlet among the skeleton branches;

ruddy haws presaged a severe winter. Early frosts turned the

low grey clouds into falling rain, and the enshrouding mists

hung above the river, and were shredded against the pine-trees

on the banks.

The uneventful days crawled on, and, as the year waned, Janet

felt herself paralysed by an inertia that robbed her of all power

of adapting her environment to her own ends. Since she could

not shape her destiny, she had to suffer; since she could not

attune herself to her surroundings, she had to endure.

One December afternoon, after a windless, brooding morn-

ing, Janet stood at the parlour window disconsolately watching

the little eddies of wind which whirled the dust into spirals, and