THE DIAL

NO. 5

LA VIE ÉLARGIE

En ces villes d’ombre et d’ebène,

Où buissonnent des feux prodigieux,

En ces villes, où se démènent,

Avec leurs pleurs, leurs ruts et leurs blasphèmes,

A grande houle, les foules ;

En ces villes soudain terrifiées

De fête rouge ou de nocturne effroi,

Je sens grandir et s’exalter en moi,

Et fermenter soudain, mon cœur multiplé.

La fièvre, avec de frémissantes mains,

La fièvre, au vent de la folie et de la haine,

M’entrâine

Et me roule, comme un caillou, par les chemins.

Ma volonté s’annule et se supprime,

Mon cœur bondit, soit vers la gloire ou vers le crime,

Et tout-à-coup je m’apparais celui

Qui s’est, hors de soi même, enfui

Vers un irrésistible appel des forces unanimes.

Soit rage ou bien amour ou bien démence,

Tout passe, en vol de foudre, au fond des consciences,

Tout se devine, avant qu’on ait senti

Le clou d’un but profond entrer dans son esprit.

Des gens hagards échevèlent des torches,

Une rumeur de mer s’engouffre au fond des porches ;

Murs, enseignes, maisons, palais, gares,

Dans le soir fou, devant mes yeux, s’effarent ;

Sur les places, des poteaux d’or et de lumière,

Tendent, vers les cieux noirs, des feux qui s’exaspèrent ;

Un cadran luit, couleur de sang, au front des tours ;

Qu’un tribun parle, au coin d’un carrefour,

Avant que l’on comprenne un sens â ses paroles,

Deja l’on suit son geste—et c’est, avec fureur,

Qu’on jette à terre et qu’on outrage un empereur,

Qu’on brise et qu’on abat le socle, où luit l’idole.

La nuit est colossale et géante de bruit,

Une électrique ardeur brule dans l’atmosphère,

Les cœurs sont à prendre ; l’âme se serre

En une une angoisse énorme, et se délivre en cris ;

On sent qu’un seul instant est maître

D’épanouir ou d’écraser ce qui va naître ;

Le peuple est à celui que le destin

Dota d’assez puissantes mains,

Pour manœuvrer la foudre et les tonnerres,

1 Et

Et dévoiler parmi tant de lueurs contraires

L’astre nouveau que chaque ère nouvelle

Choisit pour aimanter la vie universelle.

Oh dis, sens tu, qu’elle est belle et profonde,

Mon cœur,

Cette heure,

Qui crie et frappe au cœur du monde?

Que t’importent et les vieilles sagesses,

Et les soleils couchants des dogmes dans la mer ;

Void l’heure qui bout de sang et de jeunesse,

Voici la formidable et merveilleuse ivresse

D’un vin si fou, que rien n’y semble amer.

Un large espoir, venu de l’lnconnu, déplace

L’équilibre ancien dont les âmes sont lasses ;

La nature parait sculpter

Un visage nouveau à son éternité ;

Tout bouge—et l’on dirait les horizons en marche.

Les ponts, les tours, les arches

Tremblent au fond du sol profond,

La multitude et ses brusques poussées

Semblent faire éclater les villes oppressées,

L’heure a sonné des debâcles et des miracles

Et des gestes d’éclair et d’or,

Là bas au loin, sur les Thabors.

Comme une vague en des vagues fondue,

Comme une aile perdue au fond de l’étendue,

Engouffre toi

Mon cœur, en ces foules, battant les capitales

De leurs terreurs et de leurs rages triomphales.

Vois s’irriter et s’exalter

Chaque clameur, chaque folie et chaque effroi ;

Fais un faisceau de ces milliers de fibres,

Muscles tendus et nerfs qui vibrent ;

Aimante et réunis tout ces courants—et prends

Si large part à ces brusques métamorphoses

D’hommes et choses,

Que tu sentes l’obscure et formidable loi

Qui les domine et les opprime

Soudainement, à coups d’éclairs, se préciser en toi.

Mets en accord ta force avec les destinées

Que la foule, sans le savoir,

Promulgue en cette nuit d’angoisse illuminée.

Ce que sera, demain, le droit de devoir,

2 Seule,

Seule, elle en a l’instinct profond,

Et l’univers total s’att èle et collabore

Avec ses millions de causes qu’on ignore

A chaque effort vers le futur, qu’elle élabore

Rouge et tragique, au fond des horizons.

Oh! l’avenir, comme on l’écoute

Crever le sol, casser les voûtes,

En ces villes d’ébène et d’or, où l’incendie

Rôde, comme un lion dont les crins s’irradient ;

Minute unique, où les siècles tressaillent,

Nœud que les victoires dénouent dans les batailles,

Grande heure, où les aspects du monde changent

Où ce qui fut juste et sacré parait étrange

Où l’on monte vers les sommets d’une autre foi,

Où la folie, en ses tempêtes,

Forge la vérité nouvelle, et la décretè,

Et l’affranchit de la gâine de lois

Comme un glaive trop grand pour le fourreau

Et trop clair et trop pur pour le bourreau.

En ces villes soudain terrifiées

De fête rouge et de nocturne effroi,

Pour te grandir et te magnifier

Mon âme, enferme toi.

EMILE VERHAEREN

3

OPEN THE DOOR, POSY!

POSY and her mother lay side by side, quite still and white

upon the bed. The air was hot and dry and still, and out of

the window of their poor cabin the heat-haze could be seen

overhanging the roofs of the town. But Posy and her mother

never lifted a finger to disturb themselves as they lay, nor

raised an eyelid to look out.

At the end of the bed sat Death, the Taxman, looking at them.

Presently he said, “Where is my loaf of bread ? How is it you have not

got my loaf of bread for me?”

Posy’s mother answered, “We were too poor. We were a week with-

out food ourselves ; and then came the fever ; and then you came.”

“ That is a common story in these parts just now ! ” said Death. “ But

to make an end of this ; if you cannot buy me a loaf you must go to the

Poor-house to get it.”

Then Posy got down off the bed, and went to the door. She felt quite

light and thin in the sunshine ; and as she walked through the town

nothing moved out of her way, or recognised her at all. In the middle of

the town she came to the sluggish market-place : there were the booths

standing, but few people bought or sold. She wanted to cry, but her

tears would no longer go out into the living world, but fell back upon her

heart, burning it like fire.

“ If I could get some one to give me a loaf here,” she said to herself, “ I

need not go on to the Poor-house.” She stopped at the first booth and

asked. The woman went on crying her wares. She stopped at the

second booth and asked ; but the woman only cried her wares. “ They

cannot see me,” she thought ; and she stopped at the third booth, and put

out her hand.

She reached up on tip-toe : she was very small. “ I have asked,” she

said to herself, “and they have not said no.” And she took a loaf.

When she got back she gave the loaf to Death the Taxman, and lay

down by her mother again. As he was going, he called back through the

doorway, “ Mind you be ready for Death the Undertaker when he comes.

And if he doesn’t come soon you’d better call him.”

Posy and her mother lay still on the bed for the rest of that day and all

the night. In the morning the mother said, “ Get up and lookout, Posy ;

and if you see him, call him in.” Posy got up, and looked, and came

back again. “ I don’t see any one, mother, except a pedlar going along

the road carrying his pack.”

After a little time her mother said, “ Look again! ” And Posy looked,

and came and lay down, saying, “ I only saw a man going along carrying

a Punch and Judy show on his back.”

Then after a time her mother said, “ Look again ! ” and Posy looked

and said, “ There is a man coming up to the door with a coffin on his

back ; and it is the same as the pedlar and the Punch and Judy man.”

When Death the Undertaker unlatched the door and looked in, he saw

the mother and daughter both lying still on the bed, all ready in their

4 shrouds

shrouds. They were so thin he put them both into the same coffin, and

seemed hardly to feel their weight as he carried them away. On the road

he grumbled to himself because they were paupers and had left no money

for him. Presently he threw the coffin down on the ground, and went

away leaving it.

In a little while came Death the Sexton ; and he, when he saw them,

grumbled to his shovel because there was no money left on the coffin to

pay him for digging the hole. He dug only a little way and then

stopped, slipping the coffin in endways. Then he covered it over with

earth which he trampled and beat down with a spud ; and at last he too

went away.

There was no fireplace, and no window, only a plain door ; and the

mother and her child lay for a long time side by side, just as they had lain

on the bed in their little cabin by the town.

Presently there was a sound outside of a scraping in the earth, and the

knock of a hand on the wood. “Get up, and open the door, Posy,” said

her mother. And Posy went and opened the door.

There was an old man, and with him two old women rubbing the

mould from their eyes and looking in to see who was there. “So you are

here, are you?” said the old man, “you who were always so proud !”

“You kept yourself pretty stiff and highty-tighty, Missus ; you did that,”

remarked one of the old women ; “ but you’ve committed felony, it seems,

and were a pauper, which is worse.” “Well, we’re neighbours now,”

added the other woman ; “ you being in pauper’s ground, which is next to

the criminals. It isn’t any of them proud folk who’ll come and look in on

you now.”

Posy’s mother began smoothing down the crinkles of her shroud, as her

habit had been with her apron when she was a decent body in the world

above. In a little while she would let them know something ! Who

were these disreputable old neighbours that dared come and speak to her

now? She peered round the door to make out what they were like.

“ I know you, Daddy Springfeather,” she cried at last, “you that was

hung for sheep-stealing, to be sure !”

“ Not so bad as loaf-stealing !” answered the old man and the two old

women.

“ And you, and you,” went on Posy’s mother, pointing at them angrily ;

“you were the two old rag-pickers who never spent’a penny but on drink,

and died of that !”

“ Better than dying a pauper,” answered the two old women.

“Better it isn’t : but I’m neither a pauper nor a loaf-stealer !” cried

Posy’s mother. “ And you can get out of my doorway, for my coffin’s

paid for in the hem of the skirt that hangs up behind the door !”

“ This coffin,” said the old man feeling it with his thumb, “is no more

paid for than it’s mahogany: and if you didn’t send your daughter to

steal a loaf off Mealyman the baker at his booth in the market-place, you

go round and ask him; for he’s just come down, having been struck on

the left cheek by Fever, while he was loving of Famine with his right.”

5 “Posy,”

“ Posy,” said her mother, shutting the door against her assailants, so as

to speak with her daughter alone, “what did you do when you went to

fetch the bread ?”

Then Posy told her mother all about it : and said her mother—“ Where

were our wits that we forgot to tell Death the Undertaker of the money in

the hem of the skirt behind the door ; which we never touched during the

famine because it was to be for our funerals? Posy, my child, a pauper’s

coffin is a thing I can’t sleep in ! This has got to be set right.”

Before long she heard Death the Sexton digging near, for it was

paupers’ ground, and the deaths were numerous. Then she began to cry

—“Death the Sexton, come and take us out ! Death the Sexton, come

and take us out !”

When Death the Sexton heard that he laughed. “ Oh, I daresay ! ” he

said. “ And why should that be?”

Said Posy’s mother, “ Because you have buried us in a pauper’s coffin.”

“ And what have you to say against that?” “Only this,” said Posy’s

mother; “ the money for our funeral is in the hem of my skirt that is

hanging behind the door ; and unless I’m dug up, and buried again

properly, how can you expect to get paid?”

Directly Death the Sexton heard that, about being paid, he came in a

great hurry and dug up Posy and her mother and the coffin, and dumped

them down outside the burial ground.

Presently Death the Undertaker came by, and Posy’s mother began to

cry, “Death the Undertaker, come and carry us back to my house !

Death the Undertaker, come and carry us back to my house ! ”

Death the Undertaker stopped, and began laughing. “Why that?” he

asked at last. “ Because,” said Posy’s mother, “you have put us into a

pauper’s coffin, when all the time the money for the coffin is in the hem of

my skirt hanging behind the door ; and we want to go back and pay our

way from the beginning properly.”

Directly Death the Undertaker heard her speak about paying her way,

he stopped laughing quickly enough, and took up the coffin and carried it

back to the little cabin, and laid Posy and her mother back on to the bed, an

went away to get a better coffin.

Presently the mother heard Death the Taxman going by. “ Death the

Taxman, Death the Taxman ! ” she cried ; “ come and give us back the

loaf we stole for you ! ”

Death the Taxman came in grumbling. “ You may well say ‘ stole’;

I wasn’t able to eat it. I never found out till afterwards, or you

shouldn’t have got buried. What I eat for my wage has to be come by

honestly.”

“Well,” said Posy’s mother, “all you have got to do is to let us go, for

there’s money in the hem of the skirt hanging there behind the door; and

then we can buy you bread that you can eat.”

So Death the Taxman let Posy and her mother go. And when they

came to life again they found themselves quite well and hearty after their

long rest ; and the fever was gone from the town, and the famine was

6 over;

over ; and said Posy’s mother, looking round, and beginning to tidy the

house, “Since we are here again, we had better stop.”

But in a short time came Death the Taxman, and Death the

Undertaker, and Death the Sexton, all clamoring to be paid and have

their victims.

“ All in good time,” said Posy’s mother. “ You send back Famine and

Fever, and set them to catch us ; and as soon as ever they’ve caught us

again, depend upon it, well come! But until then⸺My word ! what

are you Silly Billies standing there for ? Shut the door, Posy ! ”

7

PHANTOM SEA-BIRDS.

Sirs, though ocean’s gapless bound

Ever-same do gird us round,

Fix the eye on glowing haze

Which the sun’s late-lingering rays

Crimson like anemones

That butterflies in woodland kiss :—

With the East-wind at our back,

Ere the tilting blue turn black,

Though the prow duck to the dips,

And abrupt waves slap the ship’s

Bellied bows whose timber thrills,

We may see the poppied hills,

Safe in ward of magic, steer,

Summer-sweet, o’er surges drear,

With the rambling palace, rich

Home of Circe, island-witch,

Daughter of the misled Sun,

Whom false Persa lured and won,

Long held fast and kissed and kissed,

Having couched her like a mist,

Where the salt, waste, marshy fens

Find sea-monsters brackish dens :

Helios lay there on the rushes

Which the booming storm-wind crushes,

Blushing gorgeously for shame—

Lay for hours all the same.—

Hark, perhaps a Siren sings,

Viewless talons, tail and wings ;

Deadly, deadly now their charm

With no outward show of harm.

Listen, listen, back the ear

With the hollow hand, to hear.

“The air is alive, yet fear no ill ;

Let the helm loose, and trust our skill ;

Free the tugging sail with a jerk,

For we can do all manner of work.

Safe as a bubble on milk new drawn,

Drift like a curled moon before the dawn :—

Dreams that merge in a dream more vast,

Your lives shall merge in life at last,

Where death shall loom no more, but frame the past,

As frames a park an open palace-door,

Where leaves blown in ne’er reach across the floor

To kings whose minds hark back, but their wounds grow

not sore.

8 Fear,

Fear, there, seems childish passion, known no longer;

Each sense has leisure ; memory, though stronger,

Yet veils what else might tempt the fond heart to deplore.

A queen shall fill the crystal up with wine,

To bathe your lips still smarting from the brine ;

And you shall tread,

Bare-foot, on petals shed ;

And you shall lie in jasmine-trellised bed,

Dream, meet with any friend alive or dead ;

Obedient sleep,

Prolonged for rapture deep,

Shall let each soul her chosen comrade keep

And to the full in boon communion steep.—

Turn once to hear,

True lips will brush your ear,

Our bodies in your arms be real and dear—

One whom you loved in vain, at last, drawn near.

“Woe! woe!

Let honey flow,

Let the sharp blush come and go,

Draw thick drops from the breast’s too passive snow!

O talons, let

A warm red rainfall wet

The unmoved faces, dew the stiff beard’s jet !

Ere it be vain,

Choke down this sobbing pain !

Sing, with the lips where many found great gain,

The whole of love,

The births and deaths thereof,

Timed to the wings of some spray-drenchèd dove,

Whose pink feet dip

In the long wave’s eager lip,

While faintness numb invades each frail plume-tip!—

Love, in our arms

We nurse and lull thy qualms,

Yet never felt or feel thy sovereign charms.

Our hearts are cold ;

Love, a new tale, was told

In our young ears—now has the tale grown old,

Love still unknown,

Whose praise, and that alone,

Has mocked our ears : our hearts are still our own.

Those who praised him,

Knit with us limb in limb,

Died blind with bliss while yet our eyes were dim.

9 Still

Still would we try,

Before our sweetness fly,

With you to capture Love, share Love, and die.”

Turn, turn with a welling tear

And a pleasure-cozened ear :—

See, the huge black canvas bars

Half the fully-wakened stars,

While the tackle’s tarry smell

Faintly from the hold doth tell.

Ah! the bleak mid-ocean plain,

Sad Persephone’s cold field,

Heaves with no rich golden grain,

But salt tears and sleep its yield.—

Queen, now on these furrows rocked,

May our brains from dreams be locked.

T. STURGE MOORE.

10

THE FATE OF THE CROSSWAYS.

THE roads met and crossed in front of an angle of wayside

grass, across which ran the wall of an olive-farm. Along the

top of this wall a dozen or more pollard cypresses grew

together, the elastic forwardness of their growth restrained

by informal wattles. Two cypresses, unstinted in height,

stood erect at either end of the dark hedge, with beautiful formality like

towers, a little in advance of the others, since the wall made a shallow

curve just where they rose. Against the wall, half-way up its grey surface,

a stone seat had been built, a seat transformed by weather and use almost

to a natural object.

It seemed as if the builders expected that many people would sit down

on the long bench at that place ; yet as I approached I only saw one

figure in the centre—a woman’s. Her dress was dark and her thin fingers

lay on it at the knee, quite white and without movement of any kind. Her

feet had such hold of the ground they seemed to chain it. But the veil

round her head was fluttering and milky, her pale eyeballs drew in the

light till they were full of its beatitude, and the whole face conveyed to the

beholder such activity of an indwelling mind, in spite of the unusual

features, that the impression weighed down one’s breath. She seemed to

be a goddess, to belong to the universe just by the way she sat in that

common afternoon glow, beside that bit of wall.

I could not speak to her, and she did not move to look at me, although

I felt she drew me into her eyes, as she drew the light. I stood before her,

because I had to choose my road, for I was at crossways in my journey.

Should I turn to right or left? As I hesitated and cast about, a most

singular sense came over me that the seat was crowded. I could see

nothing; but as one feels there is teeming life in the grass, or in the stream,

when one’s perception is sensitive with its own life, so I felt that seat

occupied by presences, from the woman’s figure in the centre to the cypress

towers at each end. And I knew that as I was drawn into the goddess’s

eyes like the light, so these unseen companions of hers hung on my

choice as earthly things hang on the changes of the weather. With a fear

that was nearly blind, and intensity that was actual anguish, I made my

choice. . . . . I will not say whether to right or left.

But I had not gone far along the road, before all the fierce dogs in the

neighbouring farms began to howl in chorus, as if it had been midnight

instead of afternoon. I looked back—the woman was gone and the seat

was empty with the extreme voidness of a church at mid-day.

Then the truth came to me clear.

I had been in the presence of Hecate—the dogs howled again—of

Hecate and the Souls of the Dead who wander with her.

I sank down on my new road—if with adoration or mere collapse I

cannot tell.

Ye Fates of the Wheel of Necessity, Clotho, Lachesis and Atropa, ye

are nothing as compared with the Fate of the Crossways, Hecate, who

wanders with the Dead.

The dogs no longer howled, but whimpered, and I went on direct.

SAINT IVES, CORNWALL.

The rock is all a piled and burrowed town,

As though the sea had wrought its balanced shelves

And crannies, wherein men may hide themselves,

Like lobsters in dark nooks, and lie them down.

The slimy-booted rockman, in his brown

Hard vest, glides slipperily as the elves

He hunts ; not loutishly like him who delves ;

The man of prey thus different from the clown.

’Twas he who built this fortress. Is its shape

His overcraft towards the fish, to ape

The rock the fishes fear not ? Glideth he

Lest peeping fish should mark him from the sea ?

And when he speaketh, is’t with wave-tuned breath

Lest the shy fish should hear him, what he saith ?

12

LEDA.

The heavy air hangs faint

And tangled ; so no bird complaint

Athwarts it; songs of beetles swoon

Upon the heavy afternoon.

Leda, for greed of shade,

And eager faltering through the glade

Of stammering, pleading feet, lets fall

The fetter of her purple pall ;

And, folding her bright hair

Within the twin frail fillet, bare

Lays all the treasure of her neck,

Adorned with one blue jewel fleck

Hung to a tender cord,

The circling crease, which doth afford

Steadfast, exact similitude :

The ring of Venus and her brood.

The gleaming grass lies prone :

The yews seem bronze, the poplars stone.

The very flowers at Leda’s feet

Distil a desolating heat.

Refreshing shade is not.

The darkness of the mossy plot

The willows shelter, doth oppress

The air with added heaviness.

All palpitant and dazed,

Across the lawn doth Leda haste,

To where the dreaming water lies ;

Therein to cool her mirrored eyes.

A bubbly fount makes wet

The low contiguous parapet ;

Recumbent in a wealth of green,

Against the same doth Leda lean.

The fountain’s splash beyond,

In stiller reaches of the pond,

Where weakest ripples spend their strength,

Despairing to attain its length,

The awful heavens burn

Repeated in the hollows ; yearn

With ruddier purpose, to unfold

The swelling destiny they hold.

13 And,

And, in a certain place,

Suspended on the water’s face,

The doubled swans sit motionless,

For ease against the summer stress.

Yet, lo, why stoop their crests

Contritely to their fluttering breasts,

Which hurrying wavelets break upon ?

Hush, Leda, whence this goodly swan,

This new majestic third,

Unmated, as becomes a bird

So proud imperious ? (For so fair

A fowl were matchless anywhere.)

Incomparable down

Of breast, and red-billed royal frown,

And gradual wings outspread to fold,

And back most lustrous to behold,

Are but the little part

Of his enticement, which doth start

From jocund curl of every plume,

A stalwart song, a cool perfume.

THE SWAN :

Though grasses deep

Contrive to keep

Whole for memory, and cherish

The print thy form

Leave deep and warm,

Leda, lady, grasses perish.

Essay the pool,

O beautiful

Leda, for a softer cushion ;

Glorious float

About thy throat,

Pillow fair, thy hair’s profusion.

Thine arm let deck

My willing neck,

Naught let trouble or afear thee ;

So on the tide

Against his side

Haughtily thy swan shall bear thee

14 Into

Into a nook

Of gorgeous look,

Gay with strange and varied shadow,

Whereof the floor

Is even more

Flowered than the Elysian meadow.

With which the swan floats near ;

And bidding Leda not to fear

Adventure with him, by the beck

Of his keen eyes and writhing neck,

Enticeth till her breast

Beyond the parapet doth rest ;

Until a timid hand leans out

And folds his downy breast about.

Over the margin slips

The lithe blithe line of Leda’s hips ;

And straightway hence the swan doth speed,

Exultant for his rapturous deed,

The glory of their course :

Whence his quick gesture and his force

Excite the like in Leda’s limbs,

Who, like a sturdy swimmer, swims

Beside her feathered lord,

And swift assistance doth afford.

Athwart where pendant vines above

Curtain a shallow water grove,

The swan and Leda break

Triumphant from the spreading lake ;

And pause beneath acacias’ shade,

Which drops perfume, a sheer cascade.

Till sudden lightnings split

The burning sky, and empty it ;

And raucously as eagles cry

An eagle screamed across the sky.

15

THE CENTAUR.

(From the French of Maurice de Guerin.)

IT was given me to be born in the caves of these mountains.

As with the river of this valley, whose first drops flow

from some rock weeping in a deep recess, the earliest

moments of my life fell upon the gloom of a secluded

abode, and that without disturbing its silence. When

the mothers of our race feel themselves about to be

delivered, they keep apart, and near the caverns; then, in the most forbidding

depths, in the thickest of the darkness, they bear, without a cry, offspring

as silent as themselves. Their mighty milk enables us to surmount the

early straits of life without languor or doubtful struggle ; nevertheless we

leave our caverns later than you your cradles. For it is generally received

among us, that one should withhold and everyway shield existence at the

outset, counting those days to be engrossed by the gods. My growing-up

ran almost its entire course in that darkness wherein I was born.

Our abode at its innermost lay so far within the thickness of the

mountain, that I should not have known on which side there might be

an issue, if, turning astray through the entrance, the winds had not some-

times driven in thither freshets of air and sudden commotions. Also, at

times, my mother returned, having about her the perfume of valleys, or

streaming from waters which she frequented. These home-comings, which

she made without ever instructing me about glens or rivers, but followed by

their emanations, disquieted my spirit, so that, much agitated, I roamed the

darkness. “What are they,” I said to myself, “these withouts whither my

mother betakes herself, and what is it that reigns there of such power as

to call her to itself so frequently? But what can that be, which is

experienced there, of nature so contrarious, that she returns every day

diversely moved ?” My mother came home, now animated by a deep-

seated joy, then again sad, trailing her limbs, and as it were wounded. The

joy which she brought back announced itself from afar in certain features

of her walk and was shed abroad in her glances. It was communicated

throughout my whole being ; but her prostration gained on me even more

and drew me much farther along those conjectures into which my spirit

would go forth. At such moments I was perturbed on account of my

own powers, and used to recognise therein a principle that could not dwell

alone ; then betaking myself either to whirl my arms about, or to redouble

my galloping in the spacious darkness of the cavern, I spurred myself on to

discover, by the blows which I struck in the void and the rush of the pace

I made, that toward which my arms were intended to reach out and my

feet to carry me… Since then I have knotted my arms about the bust

of centaurs, and the bodies of heroes, and the trunks of oaks ; my hands

have gained experience of rocks, of waters, of the innumerable plants, and

of subtilest impressions from the air : for I lift them up, on blind calm

nights, in order that they may take knowledge of any passing breaths and

draw from thence signs of augury to determine my path. For my feet,

behold, O Melampus ! how they are worn away ! And nevertheless, all

16 numbed

numbed as I am—subject to the extremities of old age, there are days

whereon, in broad daylight upon the hilltops, I start off on those racings

of my youth in the caverns—to the same end brandishing my arms and

putting forth all that remains of my fleetness.

Those fits of turbulence would alternate with long periods of cessation

from all unquiet movement. Straightway, throughout my entire being, I

no longer possessed any other sensation save that of growth, and of the

gradual progress of life as it mounted within my breast. No more caring

to career about, recoiled upon an absolute repose, I used to savour in its

integrity the good effected by the gods while it worked through me. Calm

and darkness preside over the secret charm of conscious life. Ye glooms,

which dwell in caverns of these mountains, to your tendance I owe the

underlying education that has so powerfully fostered me, and this, also,

that in your keeping I tasted life wholly pure, such as it flows at first,

welling from among the gods. When I descended from your fastnesses

into the light of day, I staggered and saluted it not. For it laid hold on

me with violence, making me drunk as some malignant liquor might

have done, suddenly poured through my veins; and I felt that my being,

till then so compact and simple, underwent shaking and loss, as though it

had been destined to disperse upon the winds.

O Melampus, by what design of the gods have you, who desire

knowledge of the life led by centaurs, been guided to me, the oldest and

saddest of them all ? It is now a long while that I have ceased from all

active share in their life. I no longer leave the heights of this mountain

whereon age has confined me. The point of my arrows serves now only to

root up tenacious plants. Tranquil lakes know me still, but the rivers

have forgotten me. To you I will impart certain things concerning my

youth ; but such memories, issuing from a dried-up source, lag like the

streams of a niggard libation, falling from a damaged urn. I easily

pictured for you my earliest years, because they were calm and perfect ;

simple life, and that only, slaked all craving. Such things are both retained

in the mind and recounted without difficulty. If a god were besought

to narrate his life, it would be done in two words, O Melampus.

My youth was of wont hurried and full of agitation. I lived for

movement and knew no limit to my going. In the pride of my unfettered

powers, I wandered about, visiting all parts of these wildernesses. One

day as I was following a valley little frequented by centaurs, I came upon

a man making his way along by the river, on its opposite bank. He was

the first my eyes had chanced upon ; I despised him. “There at most,”

said I, “is but the half of me ! How short his steps are, and how uneasy

his gait ! His eyes seem to measure space with sadness. Doubtless it is

some centaur, degraded by the gods, one whom they have reduced to

dragging himself along like that.”

Often, for relaxation after the day, I would seek some river bed. One

half of me, beneath the surface, was exerted to keep me up, while the

other raised itself tranquilly, and I carried my arms idly, out of reach of

the waves ; becoming oblivious thus in the midst of the waters, and

17 yielding

yielding to the sweep of their course, which would bear me far away, and

escort their wild guest past every charm of their banks. How many

times, overtaken by night, have I not followed the stream under the

spreading darkness, that let fall, even to the depths of the valleys, the

nocturnal influence of the gods ! Then my headlong life would become

tempered till there was left but a faint sense of existence, equably apportioned

throughout my whole being ; even as throughout the waters in which I

was swimming, there was a glimmer infused, shed by that goddess who

traverses the night. Melampus, my old age yearns after the rivers ;

peaceful and monotonous for the most part, they take their appointed way

with more calm than centaurs, and with a wisdom more beneficent than

that of men. On coming up out of them I was followed by their

bounties, which would continue with me for whole days, and take long

in dispersing, after the manner of perfumes.

My steps used to be at the disposal of a wild and blind waywardness.

In the midst of the most violent racings it would happen that my gallop

was suddenly broken off, as though my feet had stopped short of an abyss,

or as though a god stood upright before me. Such sudden immobility

would allow me to savour my life thrilled through in the very heat of a

present access. In those days, too, I have cut branches in the forest, that,

while running, I have held above my head ; the swiftness of my motion

would suspend the restlessness of the foliage, which no longer caused any

but the faintest rustle ; but on the least pause, the wind and tumult re-

entered the bough, which again resumed the volume of its wonted

murmur. Thus my life, on the sudden interruption of the impetuous

rush that I could command across these valleys, quivered throughout me.

I used to hear it course, all boiling, as it drove on the internal fire which

had been kindled by passage through space so ardently traversed. My

flanks, exhilarated, opposed the tides by which they were crushed from

within, and savoured, during such storms, that luxury, only known else to

the shores of the sea, of shutting in, without chance of escape, a life

raised to acme pitch and goaded still. Meanwhile, with head inclined to

the breeze, which brought me a cool freshness, I contemplated the

summits of mountains, distant since a few minutes only—I considered too

the trees on the banks and the waters in the rivers, these borne on by a

lagging flow, those fastened into the bosom of the earth and only so far

endowed with movement as their branches are submissive to the breath

of air that compels them to sigh. “Mine only,” I said, “is free motion ;

at will, I transport my life from one end of these valleys to the other. I

am happier than torrents that descend mountains never to re-ascend.

The sound of my going is more beautiful than the sighing of woods, or

than the noise of waters, and, with a voice as of thunder, bespeaks the

wandering centaur, who is his own guide.” Thus, while my flanks were

still possessed by the intoxication of the race, higher up I indulged its

pride and, turning my head, remained so for some time, in contemplation

of my smoking crupper.

Similar to green and leafy forests teased by winds, Youth heaves to

18 every

every side with the rich dower of life, and some profound murmur con-

tinuously prevails throughout its foliage. Abandoning myself to existence

as rivers do, ceaselessly inhaling the effluence of Cybele, were it

in the lap of valleys or upon the summit of the mountains, I

bounded along every-whither, a mere life, blind and at large. But

when the night, replete with the calm of the gods, found me upon the

mountain slopes, she constrained me to seek the threshold of some cavern,

and soothed me there as she soothes the billows of the sea, permitting

survival of such gentle undulations as kept sleep aloof, without however

flawing the perfection of repose. Couched on the threshold of my retreat,

with flanks hidden in its lair and head under the sky, I followed the

pageant of the dark hours with my eyes. Then it was that the foreign life,

which interpenetrated me during the day, detached itself little by little,

returning to the peaceful bosom of Cybele, as, after the downpour,

fragments of rain, caught in the foliage, fall, they too, and rejoin the

runnels. It is said that the gods of the sea, during the night-watches,

quit their palaces in the deep, and, seating themselves on the promontories,

gaze out over the waves. Thus did I keep watch, having at my feet a

live expanse resembling a sea drowsed to torpor. Rendered back to

full and clear consciousness, it would seem to me as though I came forth

from a womb, and that the deep waters, which had conceived me, were but

just returned from depositing me upon the height of the mountain, even as

a dolphin is left stranded on quicksands by the waves of Amphitrite

Goddess of the Shore.

My gaze roved freely and pierced to immense distances. Like an ever

humid sea-beach, the range of mountains in the west retained traces of a

glory but ill expunged by the darkness. Out there in the wan clearness,

persisted, live yet, peaks naked and pure. There I used to watch

coming down, now the god Pan, habitually solitary ; now a choir of occult

divinities ; or else a mountain nymph would pass, intoxicated by the night.

Sometimes the eagles of Mount Olympus traversed the highest heaven and

melted away among remote constellations, or vanished, dipping under the

inspired woods. The potency of the gods, suddenly rousing into activity,

troubled the calm of the old oaks.

You pursue wisdom, O Melampus, wisdom which is science concerning the

will of the gods ; and you wander among the nations like a mortal turned

from his true path by the destinies. There is hereabouts a stone which, so

soon as it is touched, gives forth a sound like to that of the snapping chord

of an instrument, and men tell how Apollo, having set down his lyre on

this stone, left therein that melodious cry. O Melampus, the wandering

gods have rested their lyres upon stones, but none—none has ever for-

gotten his there. Of old, when I used to keep the night-watches in the

caverns, I have sometimes believed that I was about to overhear the dreams

of sleeping Cybele, and that the mother of the gods, betrayed by a vision,

would let secrets escape her; but I have never made out more than sounds

which dissolved in the breath of night, or words inarticulate as the

bubbling hum of rivers.

19 “ O Macareus,”

“ O Macareus,” said to me one day the great Chiron, whom I was

accustomed to follow in his old age, “both of us are mountain-bred

centaurs, but how diverse are we in our habits! As you see, all the

solicitude of my days is spent upon research among plants, but you

resemble those mortals who have picked up on the waters or in the

woods, and carried to their lips, fragments of some reed-pipe broken

by god Pan; thenceforth those mortals, having inhaled from such relics

of the god a zest for wild life, or being seized on by some occult frenzy,

enter the wilderness, plunge into forests, keep company with running

waters, or become involved among the mountains, restless, and carried

forward on some unconscious enterprise. Mares, paramours of the wind

in farthest Scythia, are not wilder than you, nor more downcast at night-

fall, when Aquilo has withdrawn himself. Search you after the gods, O

Macareus, inquisitive as to whence men are derived, animals and the main-

springs of universal fire ? But the old Ocean, father of all things, keepeth

these secrets to himself, and, chanting, the nymphs ring him round in an

eternal.choir, that they may drown whatever might else escape from his

lips parted in slumber. Mortals, who by reason of virtue draw nigh to

the gods, have received from their hands lyres wherewith to charm nations,

or the seeds of new plants wherewith to enrich them ; but from their inex-

orable lips, nothing.

“ In my youth Apollo inclined my heart towards the plants, and

taught me how to despoil their veins of cordial juices. Since then I

have remained faithful to these mountains, my grand abode, restless,

but turning with ever renewed application to the quest for simples, and

to making known the virtues that I discover. Do you see yonder the

bald crown of Mount Oeta ? Alcides stripped it in order to construct his

pyre. O Macareus ! that heroes, children of the gods, should spread out

the spoil of lions upon their pyres, and burn themselves to death upon

the mountain tops ! that the infections of earth should so ravage blood

derived from the immortals! And we, centaurs, begotten by an insolent

mortal in the womb of a cloud which had the semblance of a goddess, what

help should we look for from Jupiter, whose thunderbolt struck down the

father of our race? By the god’s decree a vulture eternally tears at the

entrails of him who fashioned the first man. O Macareus ! men and cen-

taurs alike recognise, in the authors of their race, subtractors from the

privileges of immortals, apart from whom, perhaps, all that moves is only

a petty theft—mere dust of their essence, borne abroad, like seed that

floats in the air, by the almighty current of destiny. It is noised about,

that Ægeus, father of Theseus, hid, under the weight of a boulder by the

sea-side, remembrances and tokens by which his son might, on a future

day, recognise his parentage. Somewhere the jealous gods have buried

the evidences of universal descent; but by the shore of what sea have

they rolled to the stone that covers them, O Macareus ?”

Such was the wisdom toward which the great Chiron inclined my heart.

Brought down to the extreme verge of old age, that centaur used still to

foster in his spirit the loftiest discourse. His bust, vigorous yet, had but

20 little

little settled back upon his flanks, slightly inclined o’er which, it rose like

an oak saddened by the winds ; and the firmness of his step had scarcely

been shaken in the course of years. One might have said that he still

kept some remnants of the immortality received by him in time past from

Apollo, but which he had delivered back to the god.

As for me, O Melampus, I decline into old age calmly, as do the setting

constellations. Though I preserve vigour enough to enable me to gain the

summit of the crags, whereon I belate myself at nightfall, be it to consider

the restless and inconstant clouds, be it to watch mounting up from the

horizon the rainy Hyades, the Pleiades or the giant Orion ; none the less I

perceive that I dwindle away and suffer loss rapidly, even as a clot of snow

floating on a stream, and that in a little I shall make hence, to be mingled

with the rivers that take their way across the vast bosom of the earth.

T. STURGE MOORE.

21

OUTAMARO.

IF the art of Japan has made no lasting impression upon

England as to its real significance, in France a similar error

has been averted by the effort of a few artists and men

of letters. It is to them we owe the discovery of Japan.

I do not refer here to French imitations of Japanese con-

ventions in the decorative arts, or to mannerisms often

common enough to prove that vulgarity is possible even in a country

with a “live” tradition, as was the case with Japan some thirty years ago.

Efforts have been made abroad that must not be overlooked to under-

stand and class the achievements of Japanese art. If, at the present, there

are serious gaps in our knowledge, if much that passes to-day will be set

aside to-morrow, modern research has at least brought us thus far. It is

now more than thirty years since some coloured prints, rich and strange in

tone, excited the attention of a few—among them Edmond de Goncourt.

We owe to him the picture of Outamaro in a monograph that places all

subsequent admirers in the writer’s debt, and from which only generalities

and minor inaccuracies may be removed by subsequent research, leaving

to him, nevertheless, the first shadowing forth of an artistic personality

that is at once definite and elusive, limited yet suggestive, troublesome to

the dunce and pedant as the art of Watteau is troublesome.

The qualities of Outamaro have stood the test of various manners of

approach, and the exercise of that peculiar gift of fascination that is his,

has forced itself upon the attention even of those who had entered upon

the study of Japan under the spell of its later magnificent realism. The

art of Outamaro will win one also from reactionary mood, due to an over

familiarity with the excellent, in a country like Italy, that has had its

specious primitives and decadents. We would place Outamaro in a phase

of art at once attractive and dangerous, in a phase where, as with Botticelli,

an art has refined strangely upon itself, accepting, however, certain signs

of fatigue, not, as with the Italian, in technique as from callousness or

haste even, but in a tendency towards monotonous trains of thought. In

Europe the art of Schöngauer with its over-sweetness, of Zasinger with its

delicacy, would hardly prepare one for the might and passion of a Durer,

whose art was influenced by them. So the art of Outamaro does not

prepare one for the advent of a Hokusai. It is there that he will seem

at once primitive and decadent, but, like Botticelli or Mending, Outamaro

escapes at times into charmed spaces, and divines, intermittently perhaps,

much that those who came before or after him did not divine, or were

unable to achieve. A feeling that with this Japanese a monotonous and

even feminine bent of mind mars an infinite refinement in form and colour

may lead men of intelligence to suspect him, and with him the eighteenth-

century art of Japan.

I take it that a certain impatience is manifest among serious art-lovers

towards the trade-primitives of Italy, whose hold upon men of the last

generation was excusable in the light of discovery and surprise. I do not

think, however, that the bankruptcy in the delicate tradition of eighteenth-

22 century

century art of Japan is entirely comparable to that notable break in the

great Tuscan school after the death of Piero della Francesca, a Tuscan by

temper. In Japan in the eighteenth century the technical side was

developed; we may add that this technical refinement became subse-

quently a burden. The impeachment of Italy implies a technical collapse.

The mind passes from Piero della Francesca to Leonardo for a continuity

in restraint and technical perfection. The great violent art of Mantegna

and Luca Signorelli seems contemporary with that of Paolo Uccello, and

to contain efforts and experiments that Donatello had solved successfully.

In Japan, one of the three centres whose tradition may be viewed in its

entirety, the art-lover who is never angry or prone to reactionary moods,

will accept this phase in which the love of women has absorbed all other

attention, and will accept it for what it is.

The mere accidents of a tradition would make of Outamaro an early

master of the modern school, “the school of life,” and a pioneer in revolt

against the conventions of older academies, in a revolution that may be

said to culminate in the works of the great Hokusai. This definition, if

commonly accepted, is to some extent inaccurate. I would urge that his

unique prominence in an epoch of change has numbered him among the

quite realistic masters. To aims of his own he added some interests

common to the realistic schools, but did they not borrow from him in

their earlier works? The spirit in which Outamaro painted has affinities

with aristocratic and æsthetic conditions of the Tosa school, whose import-

ance in Japanese art has been too constantly overlooked. I think he

shows this mental bent more than his immediate forerunners or older

contemporaries in the eighteenth century, with whom the realistic move-

ment is latent, though their manner, like that of Outamaro, has no affinity

with Chinese methods ; and out of these grew the realistic school.

By the excursions of an exquisite fancy he extended or transformed the

subject-matter of his forebears, who treated by preference scenes in the

every-day life of ordinary people : scenes noticed by the aristocratic Tosas

only in the background of a Court procession. As with the earlier eighteenth-

century masters, he retained the Tosa convention of a chastened outline,

a recollection of their aristocratic interiors, and the care for dress ; some-

thing also of their over-wrought languor. The affinities of the Tosa school

do not lean towards China. In method the Tosas were an offshoot of those

miniaturists come from India with the Buddhist religion. Wewill find traces

of Indian formulæ, in time transformed, it is true, but opposed to the more

calligraphic influences of China, that were to be revived by Hokusai, and,

at this moment, one is seized with a sense of hallucination ; the half-

revealed whiteness of an apparition passes across one’s eyes beyond the

perspective of sanctuaries, as we remember that touch of Hellenic sweetness

at the heart of Indian Buddhism, carried with it into the farthest East

among a new people and new conditions, not dead at all, but altered, and

putting a trace of some remote European manner into this later phase of

Japanese art in this eighteenth century.

23 Whatever

Whatever maybe the influences upon the work of Outamaro, his colour-

harmonies fulfil his own needs and the exigences of the colour print; to

the subject-matter of his immediate forerunners he has brought a gift of

analysis, an element of the strange, the exquisite, that mere nothing making

for grace. His name conjures up the vision of cloud-like colours, and

shapes that have the curve of fountains, upon a world remote yet actual,

as it would seem to us, for its newness and for its trivialities even, he has

shed that grace as of faded things, the troubled hues of a fresco about to

disappear, of a flower dying in the twilight.

With Outamaro the attention given to an act, a movement all bright, all

gay, all trivial, has acquired by the subtleties of his art a tint of seriousness,

of sadness, that never leaves him, that will class him among poetic painters,

painters of fancy and of mood. Unlike Hokusai, we are told that dramatic

effect lay beyond his aim. He was proud of his achievement as the mere

painter of the spring, the painter, the portrait-painter of fair women. At

home he was sometimes despised as the artist for the tea-houses, a minister

to those frivolous needs of women to whom he brought the new things of

fashion and the ways in dress, as a talent full of charm but devoid of all

seriousness. Tragic episodes treated by some notion of his, as if acknow-

ledging his limitation, have been given over to women instead of to men,

where a haunting sense culminates in the dramatic opposition of an unique

black dress to the folds of fairer dresses; or, perhaps, the anxiety faintly

shadowed forth about the hour and place by the presence of a naked sword,

the implied presence of an end beyond the motions of his actresses. A

twist of mind breaks through the constant preoccupation to charm, some-

times the urging of inverted energies pushes him to the erotic and the

terrible, but even here he will use majestic lines and chosen colours ; we

may well marvel at a train of thought so strange to the more downright

ways of Europe. Yet we may be mistaken to wonder overmuch. An

artist always grasps at hints, giving variety to the aspects of his work,

in indifference to the probable effect upon those who would have praised his

limitations without effort, or with hostility; such moods of delicate falsity

remain not too distinct to the artist himself, for in the exercise of the

imaginative faculties thoughts will take motion curiously, as it were from

freshets of strange winds, blown from quarters remote ; he will feel the

countershock of distant events, and there is danger from without in the

censure of such “digressions”; they will be found not to answer to the

cravings of the affectation or imposture, but to the requirements in the

health of an exceptional state. With Outamaro, whose mind was without

anxiety or trouble, something of shadow may become noticeable, for half

the passions of life and the terribleness of things make their appeal through

the eyes to the mind. Let me repeat : his nature leant out towards the

fairer aspects of life ; it was untroubled by choice, by any emotion out-

side a world that lived very close to the flowers, in an immunity from

anxiety and under conditions we can hardly imagine now and here ; yet we

have the evidence of other emotions forcing themselves upon him, and he

has enriched his work with a passing allusion to them.

24 He

He died having loved too well. He was a great lover of women,

whence curious intuitions, feminine intuitions—often present in men of

his stamp—expressed here almost for the first time. Natures like his are

not averse to the sight of maternity, and in his rendering of women

ministering to the little wants of their children he retains a charm denied

to the more grave Italian painters of the Madonna. His printed works

are numerous. During his lifetime he enjoyed a great reputation that

penetrated even to China, and leaf after leaf reveals his quest of the

unexpected, directed by a preoccupation for delicate nuances—I can find

no other word, and not for the sensational element therein. He will select

from the fleeting graces of a game, or from the motions of reverie alike.

This he clothes with the tints of early anemones and of faded leaves, with

tender grey retaining an inward glow or flush, as of colours absorbed by

time ; his mere paper will be mottled with traces of colour that has been

removed, or glazed with a frosted substance like the dried white of an egg.

He possesses to the full the resources of a colourist who is always sensitive

in the matter of surfaces—the colourist of a country that has several names

for white. A common characteristic in his work is the love of mirrors, and

of reflections in water used to repeat or introduce an element of interest.

In composition he will affect the half-drowned appearance of things bathed

in water, as in the two magnificent triptych prints, Les Plongeuses and Les

Porteuses de Sel, veiling the limbs of his women in the twilight of a wave.

It serves his purpose to reduce what might be too definite for him, by

means of spangled and translucent materials become playthings in the

hands of women, as in one of those magnificent prints where a courtesan

passes a veil across her mouth and eyes, or in that design charming with

its yellows and greens (now in the Louvre), in which a mother peeps at a

child from behind a scarf. With him the green haze of mosquito-nets is

used for the shadowing forth, beyond, of the half-hidden whiteness of a

face, or to make emerge from the shadow a hand or arm with the effect of

some flower rising from the water.

If as a colourist he works in a key that rests in a quietude of tones

unusual in the art of Europe, we may add to this that time and use have

made amort the stronger oppositions of blacks and yellows, or the vivid

crossings of white used to freshen any languor of effect, and have given a

quality that cannot be found in new surfaces, wearing the crispness of the

size out of the paper, making his means more elusive and his colour more

grave.

There is often a great attractiveness about things once bright, meant

from the first to be captivating when thus greyed by the handling of time ;

for this reason men have been found who, like Baudelaire, divined the

charm even in old-fashion plates, apart from any sententious interest to be

drawn from them, as with our own Thackeray, who wore spectacles. The

art of Tanagra passes as a fortunate addition to our enjoyment, brought

about by things originally of slight importance, but found now to be

exquisite indeed. For the moment the prints of Outamaro do not share

this suffrage, in England they are known as yet to the few merely as

25 things

things of curiosity. That I have dwelt upon the slightness of their aims

may seem against their being treated too seriously; but art in Japan

dwells close to every movement in life, a ministrant jealous of all possible

exactness, yet without fear of the indifference of persons like ourselves,

jaded to all but novelty, whose appreciation is only one of sudden exclama-

tions, and who ask art to be something added to life, like opium perhaps.

The cultured of his country are light of heart, they dismiss the over-

positive and the vague alike, but gracefully for what it is ; a glint of light,

a waif of perfume, the all-absorbing, the gluttonous melancholy at the

heart of the East, touches them but little ; they are apt to be ironical about

it, to pass it by in a verse or a simile with a gaiety that is foreign to us

also, at any rate recognising it nobly, as the passion for the few. One of

their greatest artists, Outamaro, has accepted these conditions, ministering

exquisitely to the needs of an audience that to him was never dull and

rarely tired. A great sense of perfection, alone reveals that finer sadness

from which all sense of perfection is seldom entirely free.

Among slight things of grace few will be found to equal the grace, the

charm that is his ; his deftness of hand is no mere slightness of execution ;

and if in this matter it is a little languid beside the more direct brush-

work of some Greek vase painters (at times strangely akin to Japanese

workers with the brush), his sense of grace will be found to contain also a

latent spark of strength almost wholly denied to the sweet popular

figurettes of Tanagra ; his conventions retain a franker, swifter sense of

truth, for which reason he is sometimes classed as a realist ; he also meant

no more than to please, but to please a people whose possibilities for the

future had not ceased, and, with all his self-consciousness of means,

however complex, he represents the subtlety, the complexity of a tradition

that is young, and for this reason his results will remain unforeseen and

fresh to us.

CHARLES STURT.

26

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Front Cover designed and engraved by Charles Ricketts

❧ Full Page Illustrations

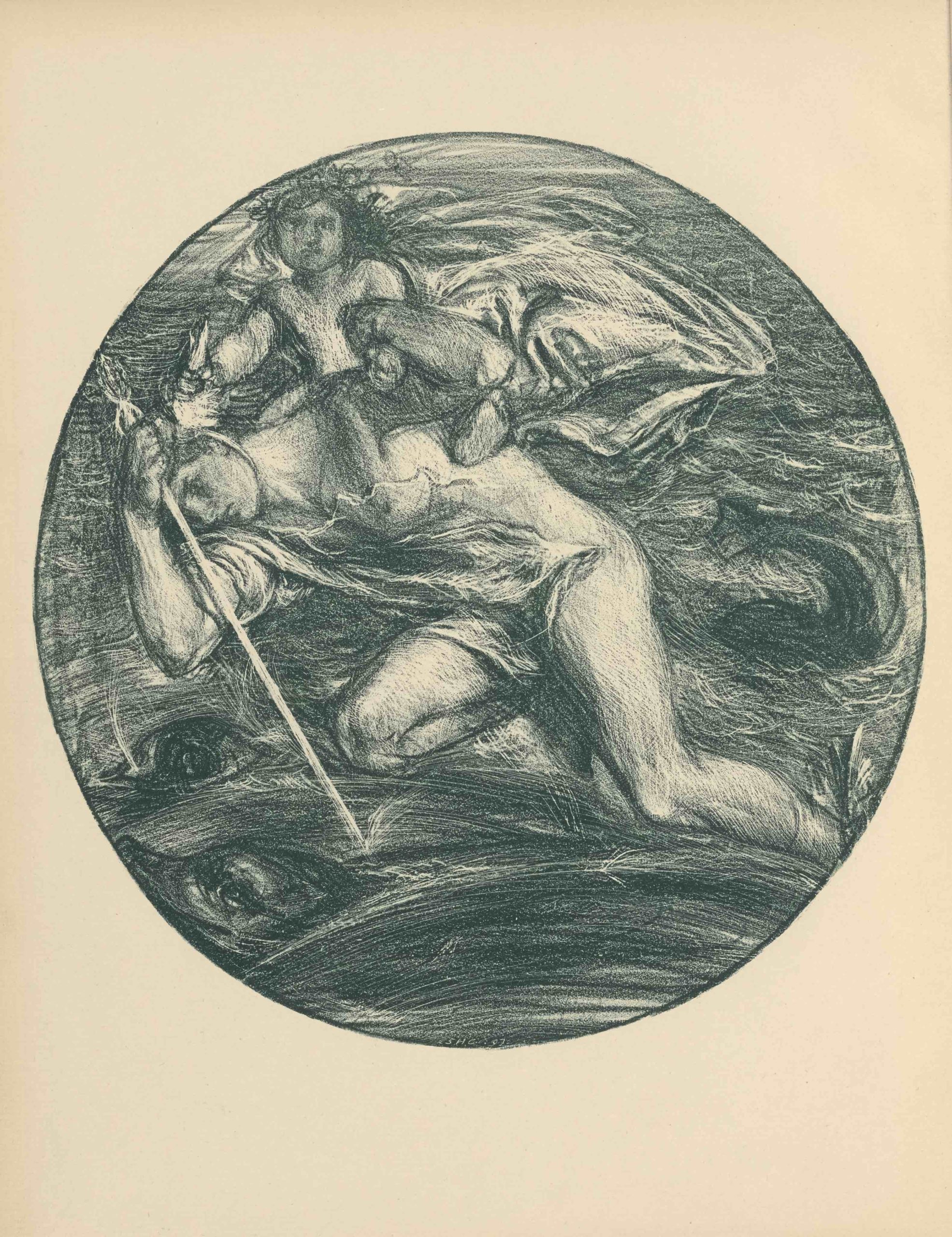

THE INFANCY OF BACCHUS an original lithograph drawn on the stone by C. H. Shannon . . . facing page 1

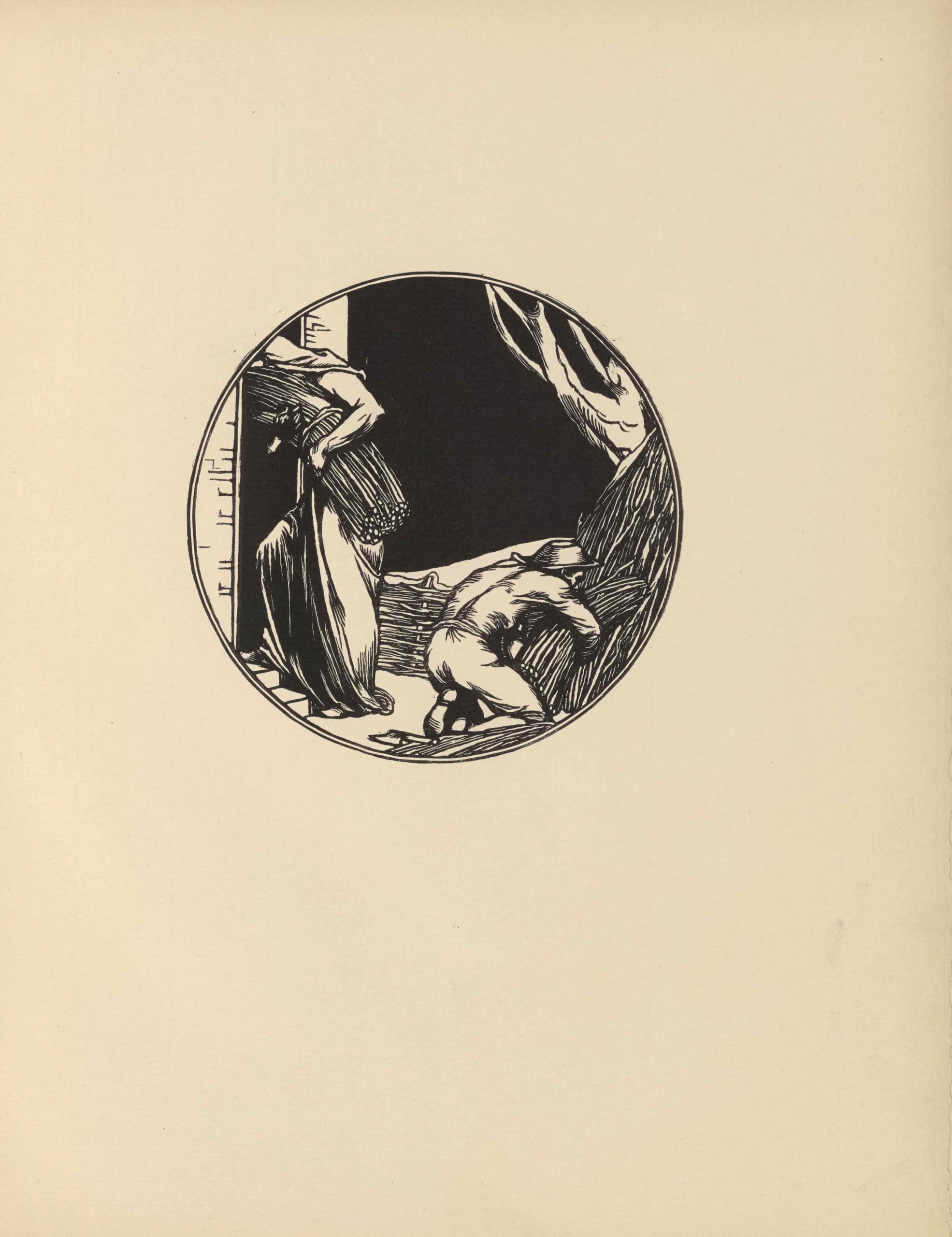

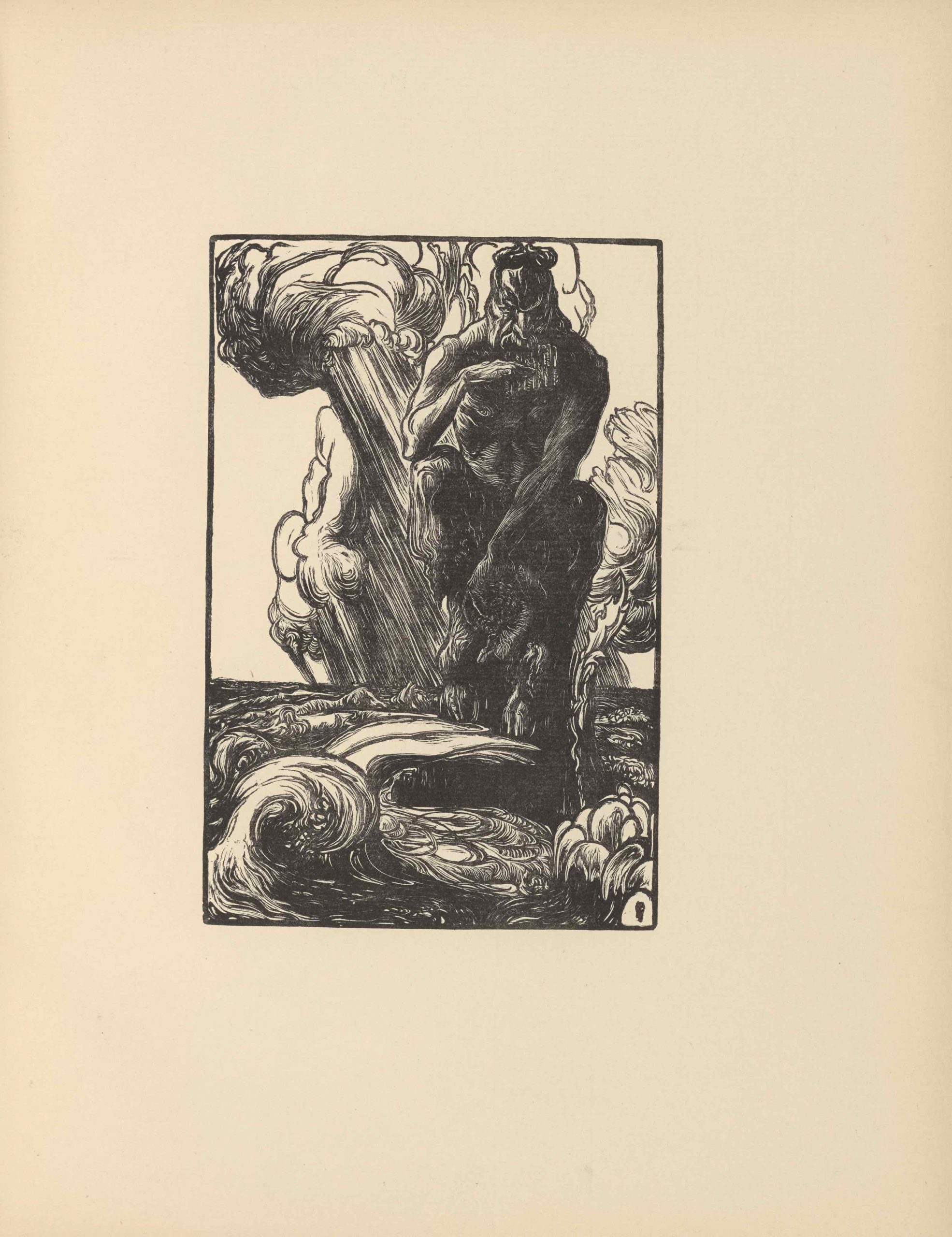

DECEMBER an original woodcut designed and cut upon the wood by C. H. Shannon . . . facing page 5

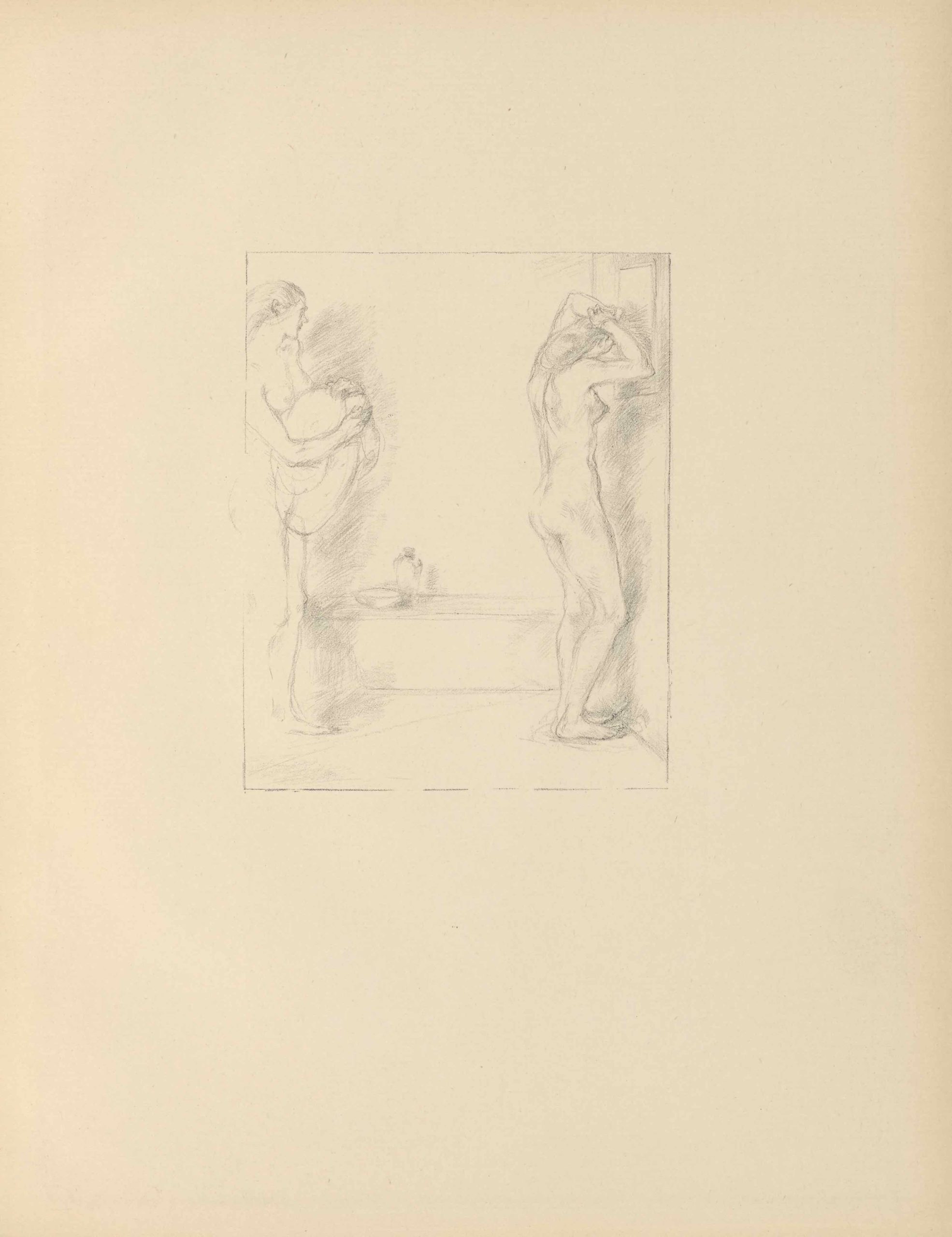

THE DRESSING ROOM from the “Stone Bath Series” a paper lithograph by C. H. Shannon . . . facing page 9

PAN ISLAND an original woodcut designed and cut upon the wood by T. Sturge Moore . . . facing page 13

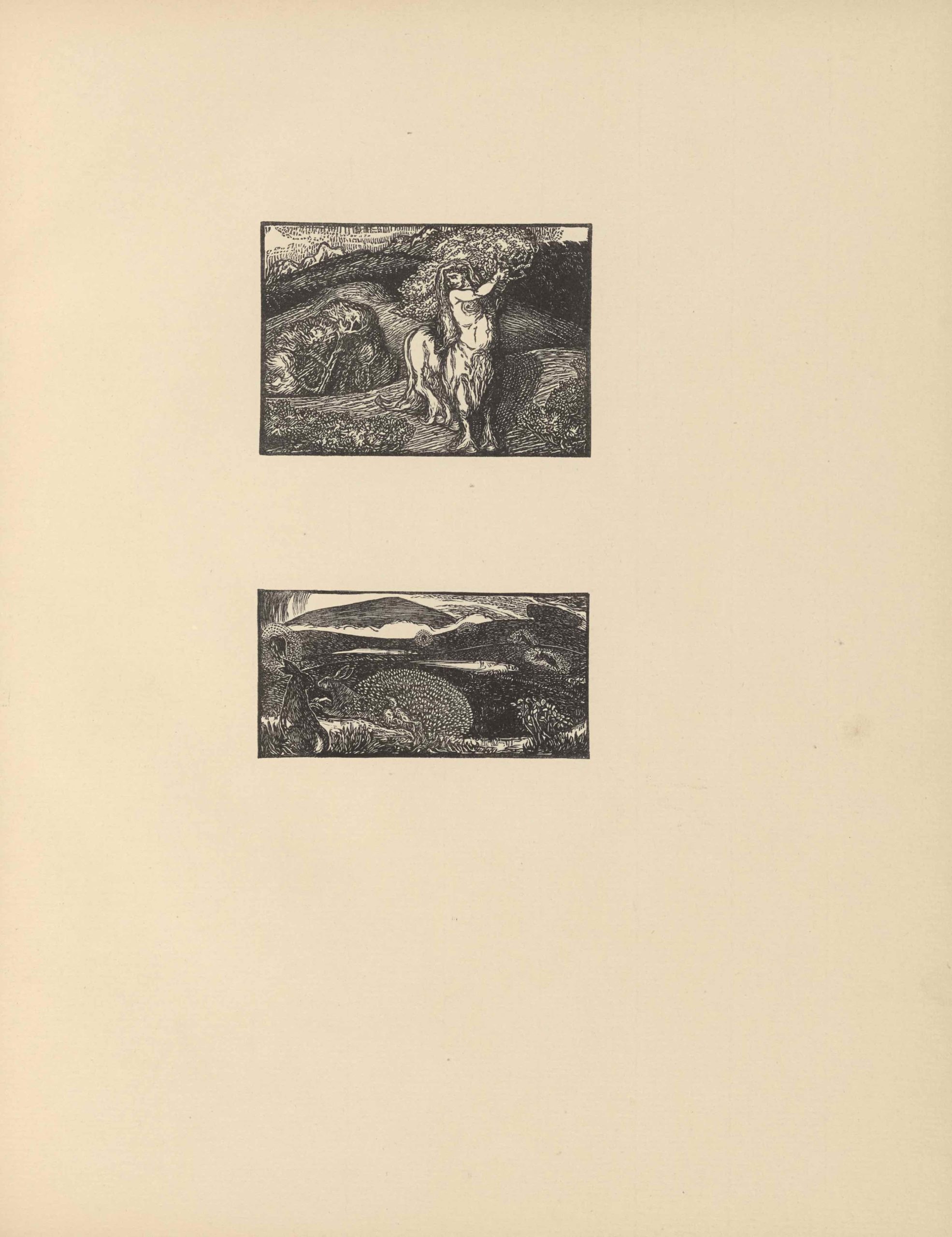

CENTAUR WITH A BOUGH and THE HARE MAKING CIRCLES IN HER MIRTH being two original woodcuts drawn and cut upon the wood by T. Sturge Moore . . . facing page 17

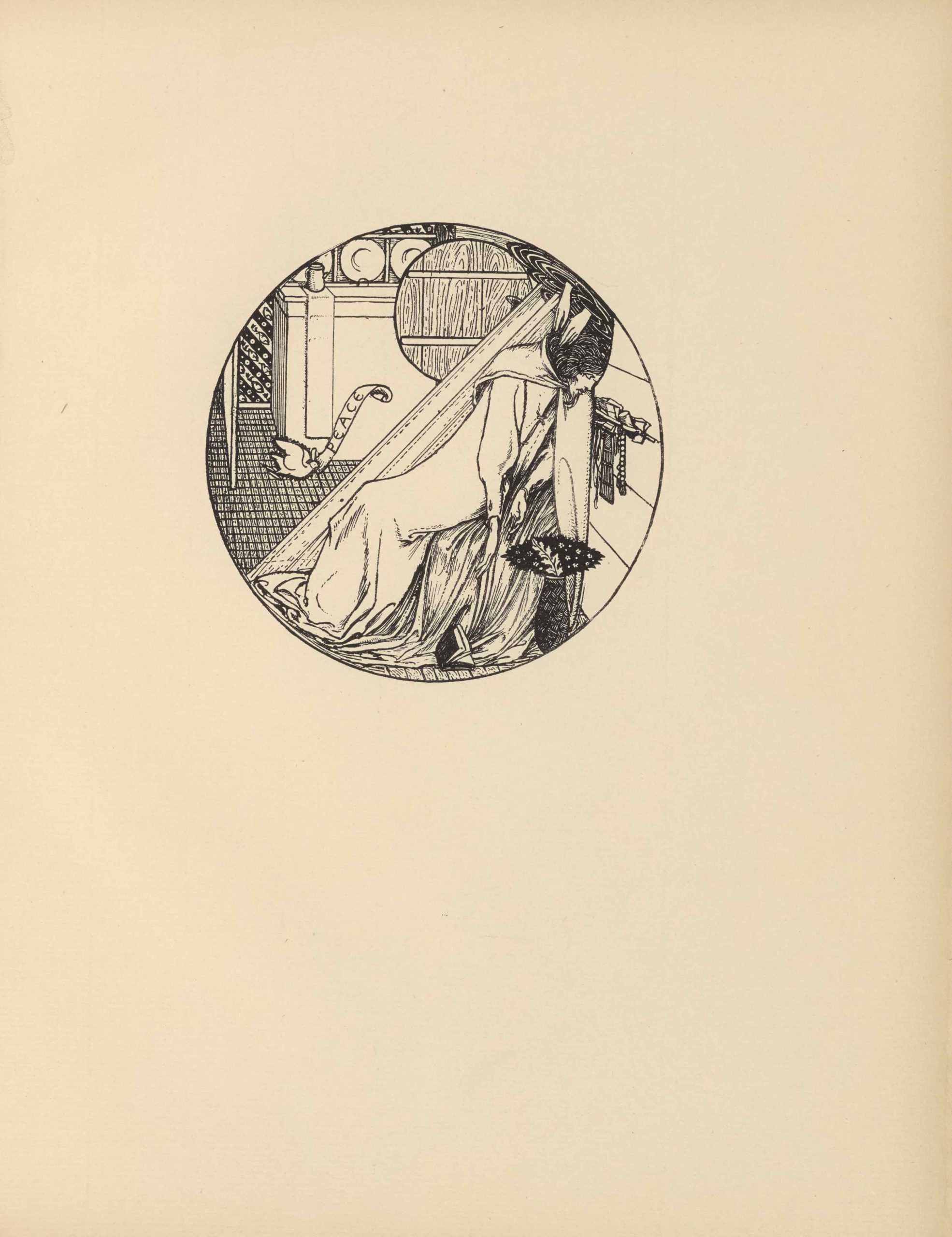

THE VISION OF KING JAMES THE FIRST OF SCOTLAND ❧ after a pen design by C. Ricketts . . . facing page 21

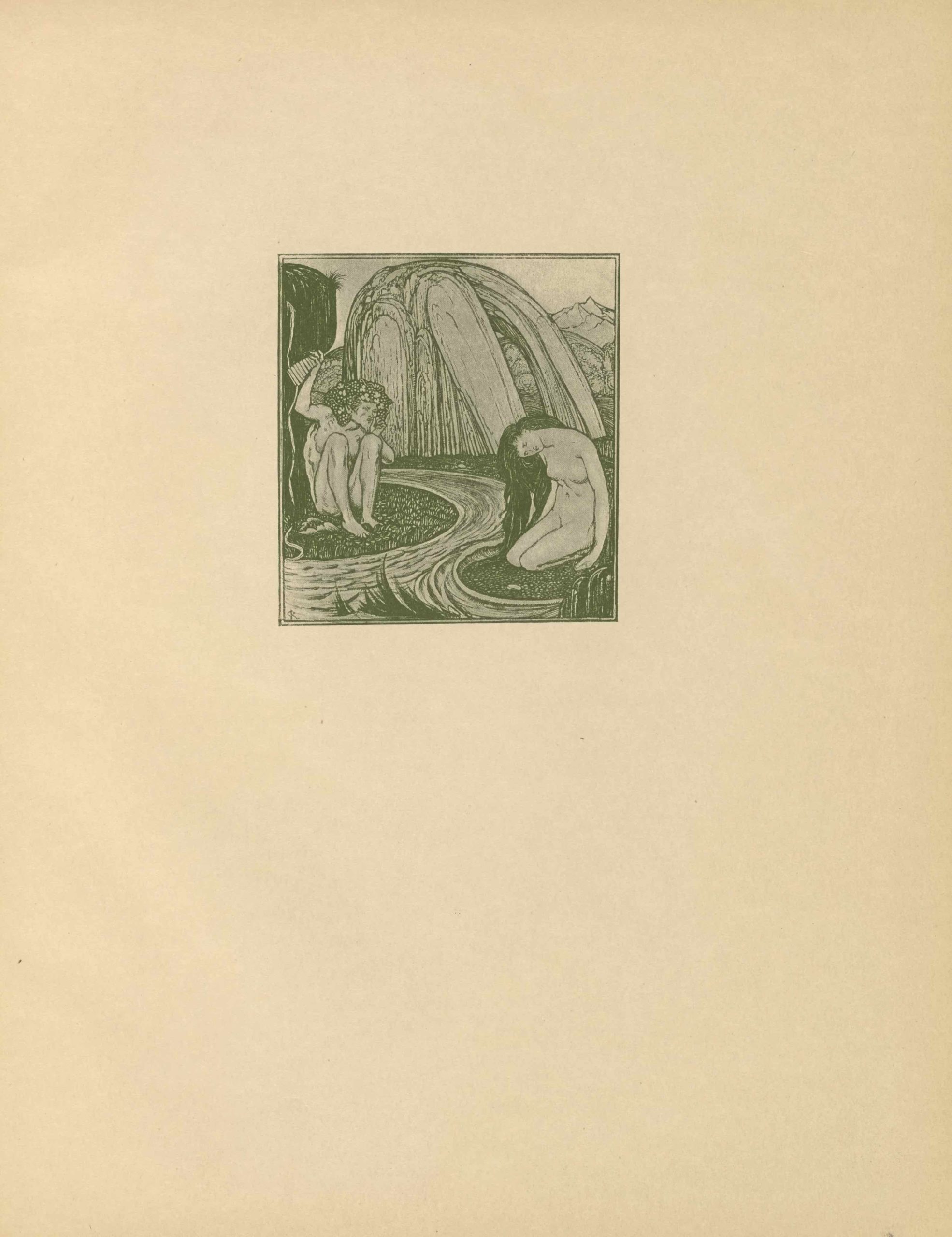

PAN HAILING PSYCHE ACROSS THE RIVER ❧ after a pen design by C. Ricketts . . . facing page 25

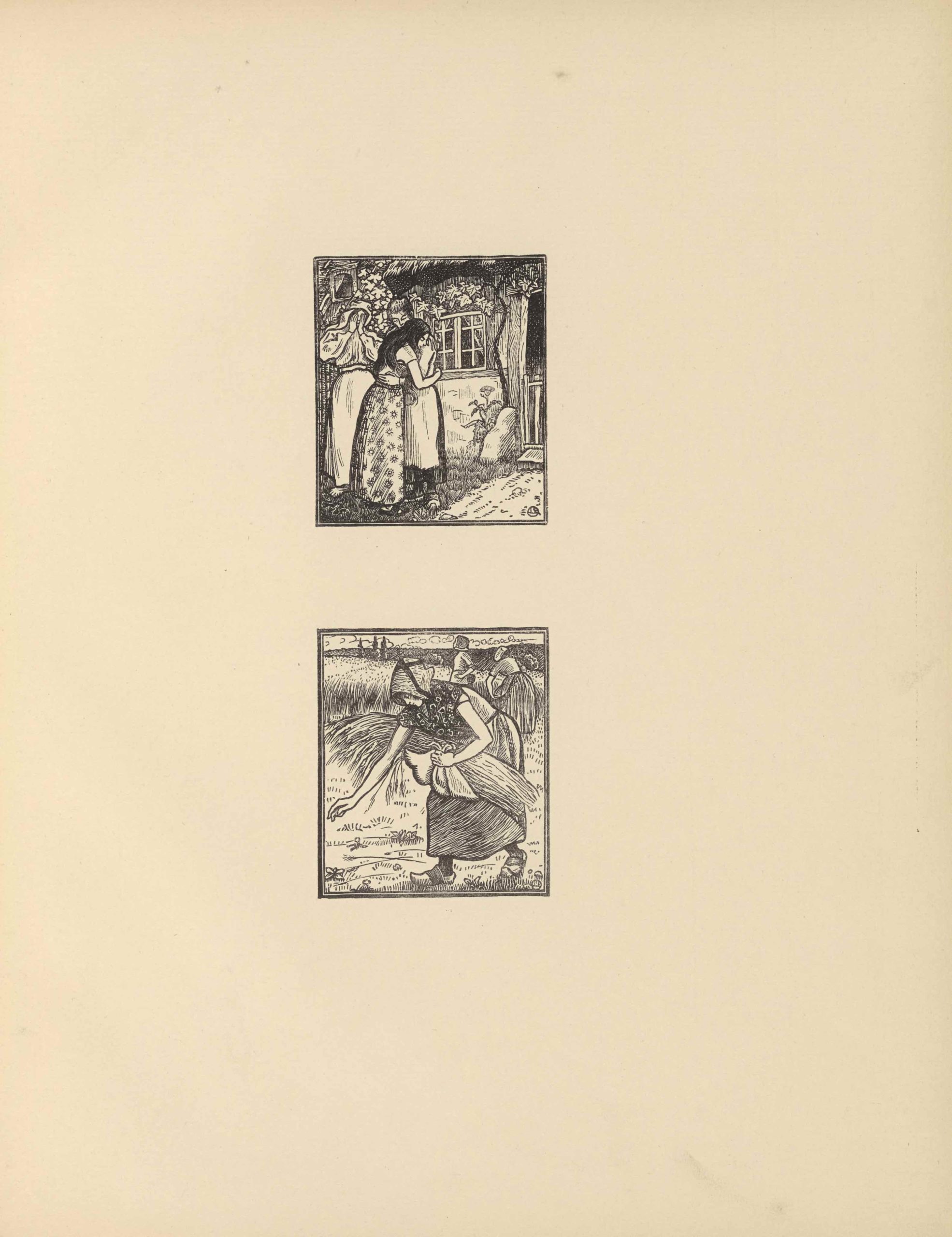

RUTH, ORPAH, AND NAOMI and RUTH THE GLEANER being two original woodcuts drawn and cut upon the wood by Lucian Pizzarro [sic] . . . facing page 27

Ballantyne Press Colophon by Charles Ricketts . . . facing page 36

❧ Literary Contents

LA VIE ÉLARGIE [The Expanded Life] by Emile Verhearen . . . 1

OPEN THE DOOR, POSY! by Laurence Housman . . . 4

Initial by Charles Ricketts . . . 4

THE PHANTOM SEA-BIRD by T. Sturge Moore . . . 8

THE FATE OF THE CROSS-WAYS by Michael Field . . . 11

Initial by Charles Ricketts . . . 11

ST. IVES, CORNWALL by John Gray . . . 12

THE CENTAUR by Maurice de Guérin translated

by T. Sturge Moore . . . 16

Initial by Charles Ricketts . . . 16

THE ART OF OUTAMARO by Charles Sturt [Charles Ricketts] . . . 22

Initial by Charles Ricketts . . . 22

Full-page Illustrations and [Literary] Contents . . . [27]

The two full page pen designs above marked

with a device ❧ have been reproduced

by Messrs. Hentschel and by the

Swan Electric Engraving Company

The lithographs have been printed

by Mr. Thomas Way.

MLA citation:

The Dial, vol. 5, 1897. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://1890s.ca/dialv5-all/