THE DIAL

NO. 4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Front Cover designed and engraved by Charles Ricketts

Table of Contents . . . [vii]

❧ Full Page Illustrations

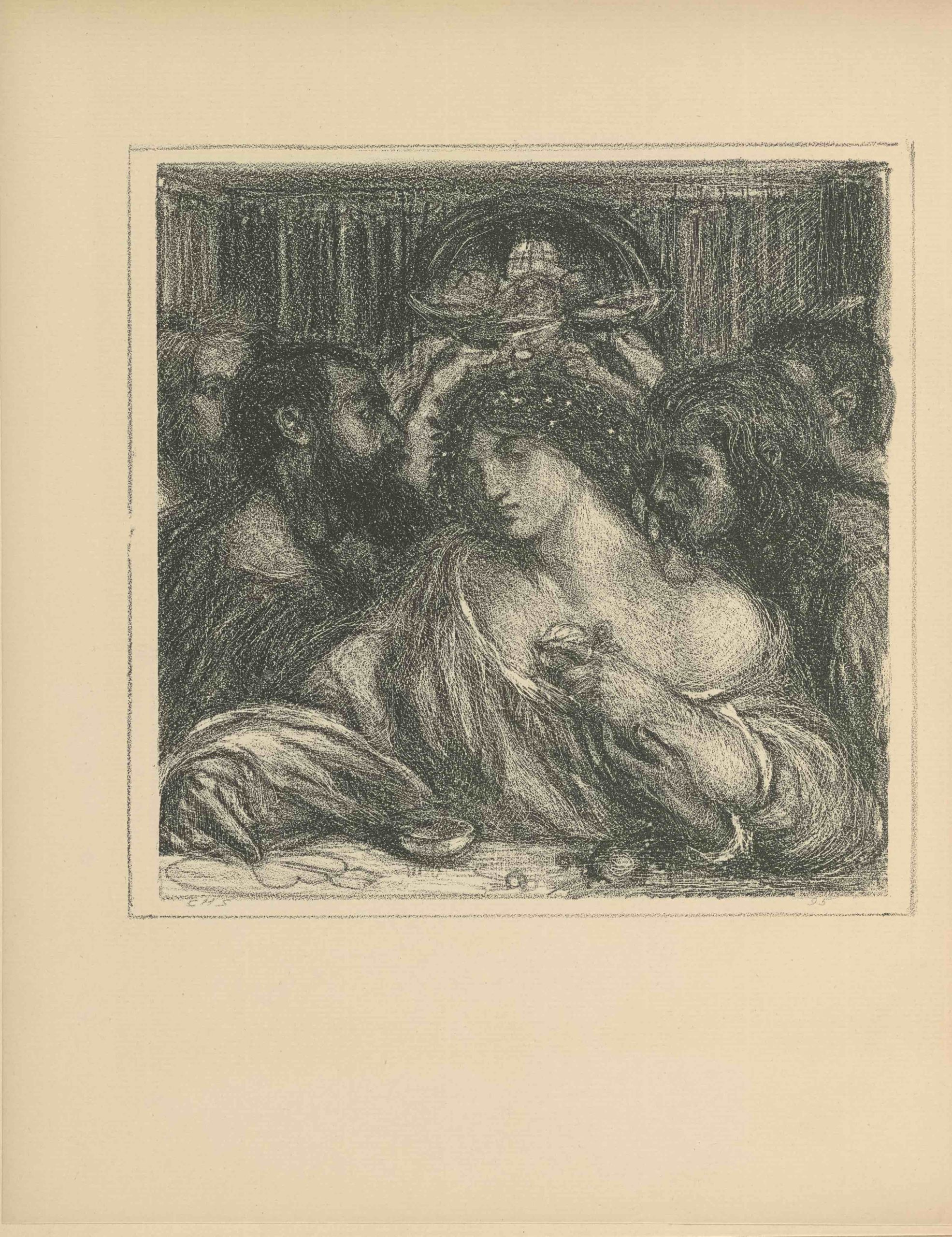

Frontispiece: DELIA an original lithograph drawn upon the stone by Charles H. Shannon

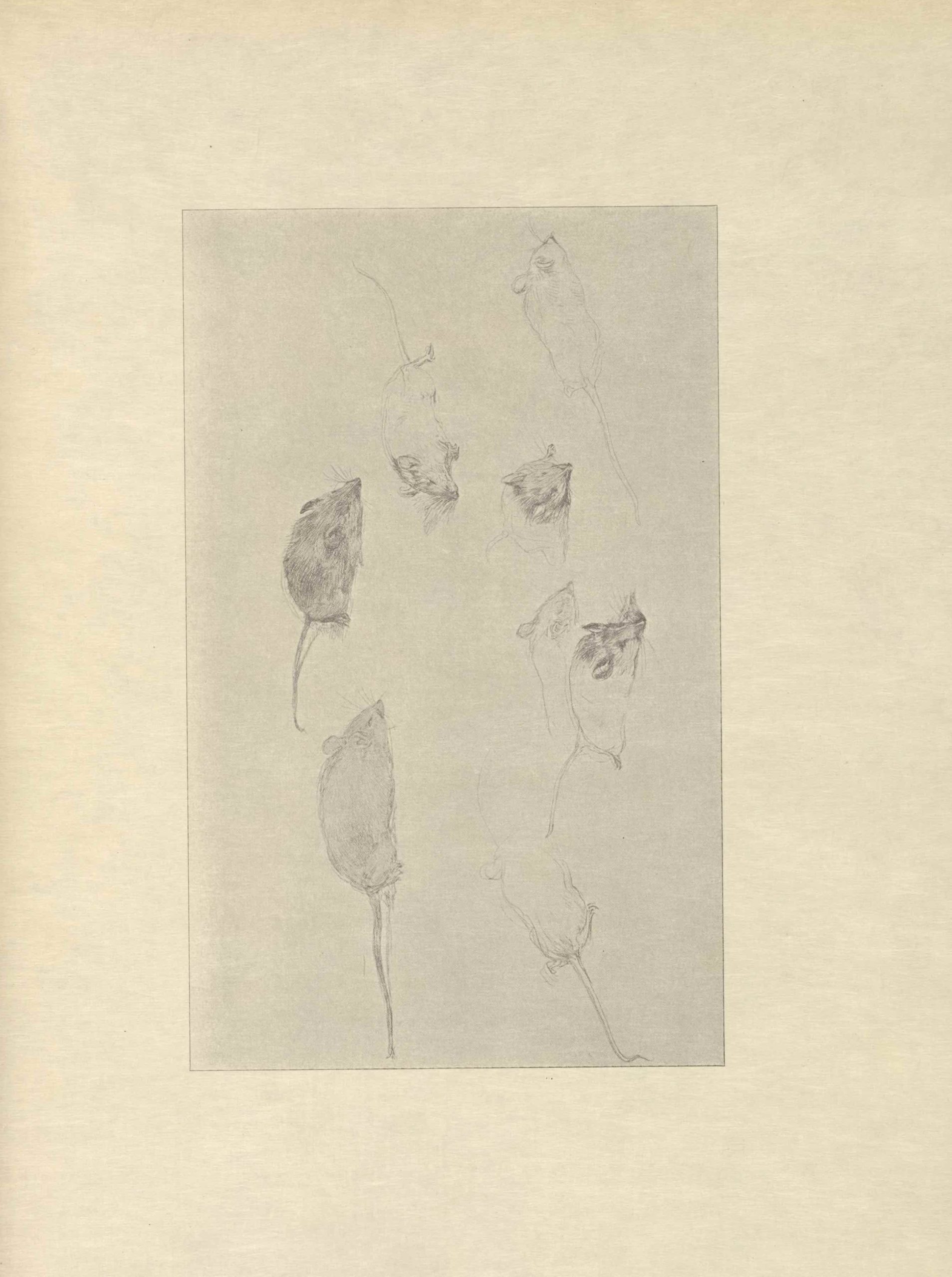

A STUDY OF MICE ❧ after a silverpoint drawing by Charles H. Shannon . . . facing page 5

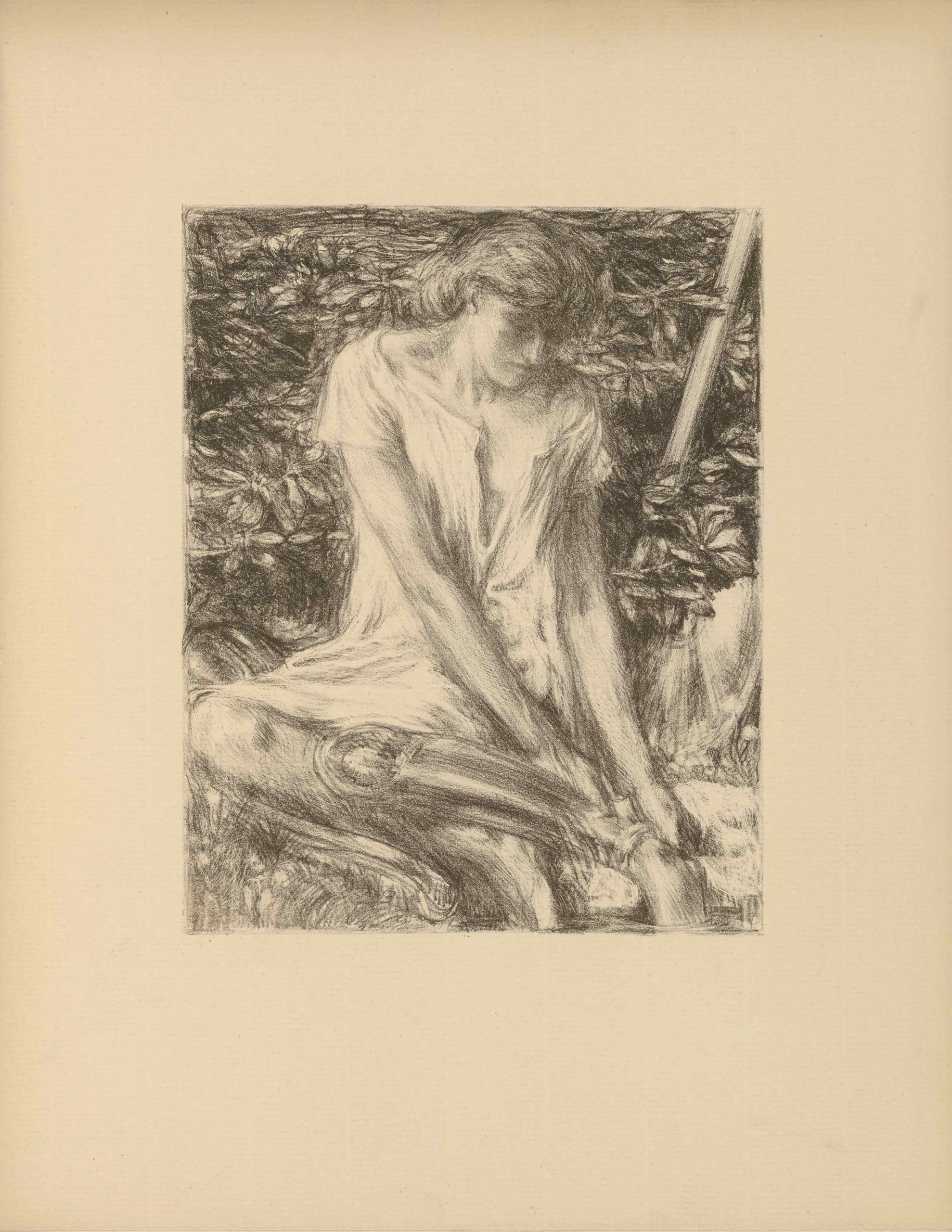

ATALANTA an original lithograph drawn upon the stone by Charles H. Shannon . . . facing page 9

LE PETIT CHAPERON ROUGE an original woodcut designed and cut on the wood by Lucien Pissarro . . . facing page 13

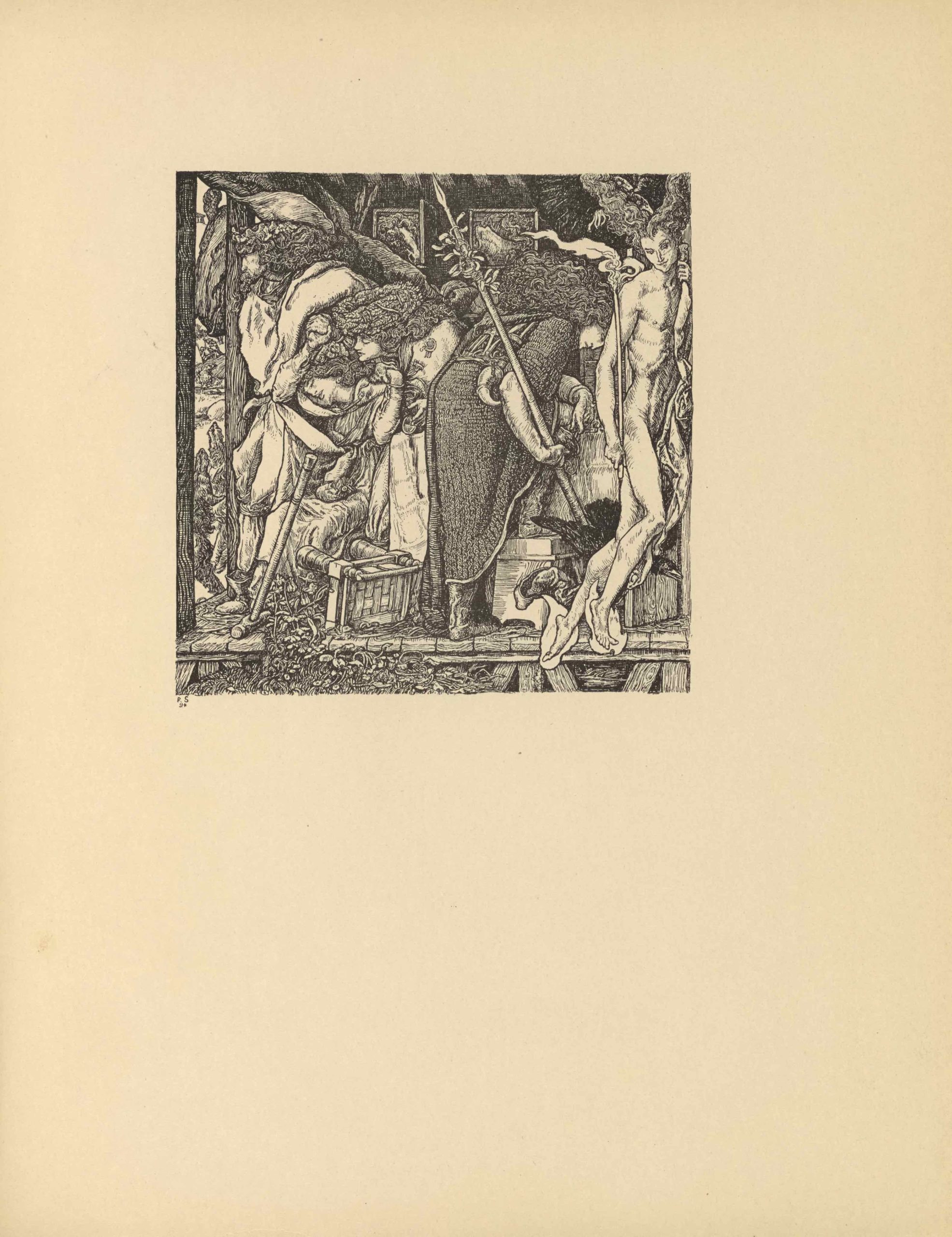

DEATH OF THE DRAGON an original woodcut designed and cut on the wood by T. Sturge Moore . . . facing page 17

BABY GIANTS an original woodcut designed and cut on the wood by T. Sturge Moore . . . facing page 21

AN ILLUSTRATION TO THE KING’S QUAIR ❧ after a design by Charles Ricketts . . . facing page 25

TWO PAGES OF THE VALE TYPE (WITH INITIAL) designed by Charles Ricketts . . . inserted pamphlet paginated [i-iv]

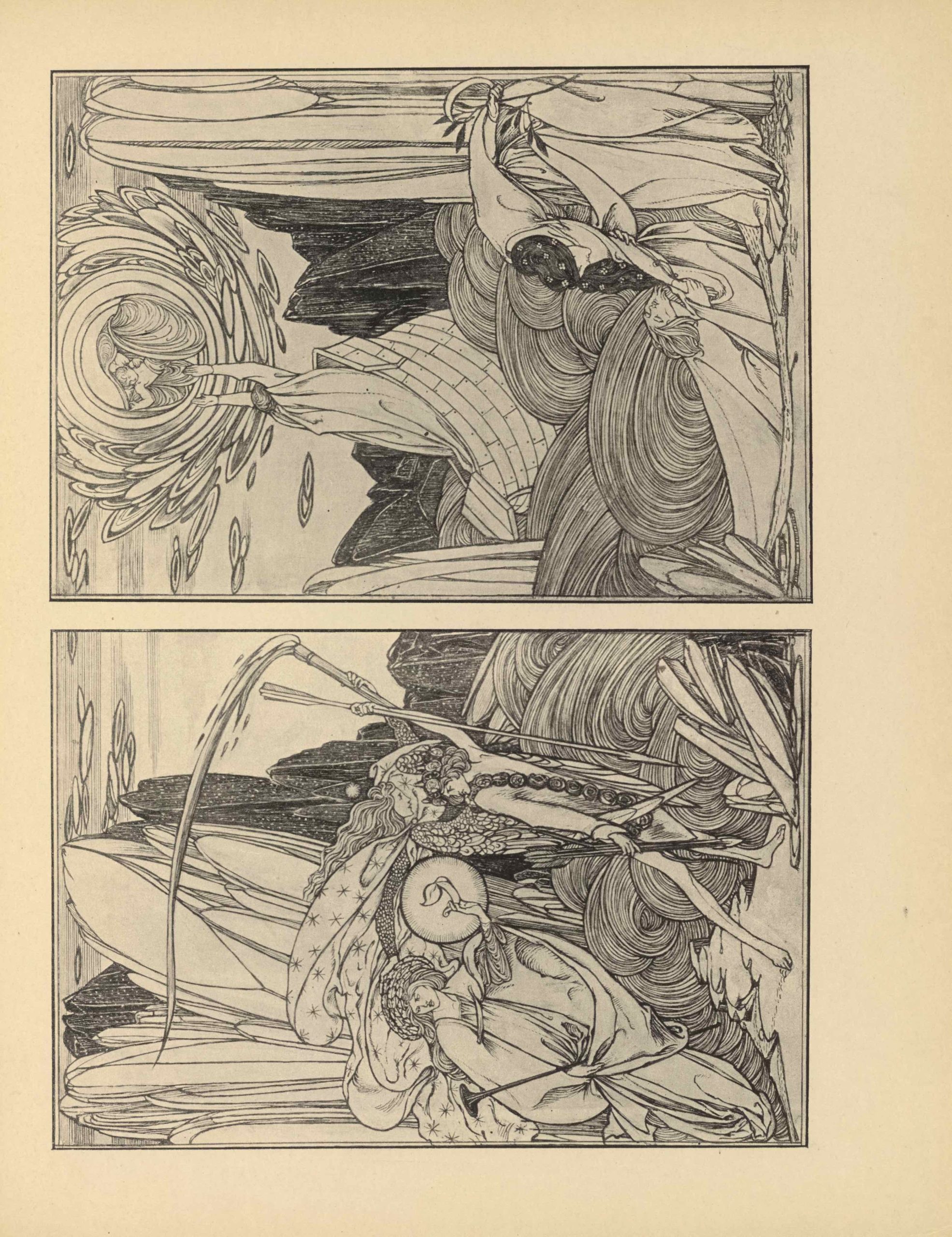

WOTAN AND LOGI DEPART IN SEARCH OF THE REINGOLD ❧ After a pen drawing by Reginald Savage . . . facing page 33

Ballantyne Press Colophon by Charles Ricketts . . . facing page 36

❧ Literary Contents

THE FLYING FISH a poem by John Gray . . . 1

EN ROUTE [The Redemption of Durtal] an article by John Gray . . . 7

Initial by Charles Ricketts . . . 27

A PRAYER TO VENUS a poem by T. Sturge Moore . . . 12

THE BEAUTIES OF NATURE by John Gray . . . 15

Initial by Charles Ricketts . . . 27

A SONNET [On a Portrait] by Michael Field . . . 18

THE WRITING ON THE WALL by W. Delaplaine Scull . . . 19

Initial by Charles Ricketts . . . 27

BATTLEDORE two poems by John Gray . . . 34

Three full page illustrations marked above

with a device ❧ have been reproduced

the first by the Swan Electric Engraving Company

the second and third by Messrs. Walker and Bou-

tall. The lithographs have been printed by Mr.

Thomas Way.

THE FLYING FISH

I

MYSELF am Hang, the buccaneer,

Whom children love and brave men fear,

Master of courage, come what come,

Master of craft and called Sea-Scum;

Student of wisdom and waterways,

Course of moons and the birth of days:

To him in whose heart all things be

I bring my story from the sea.

The same am I as that sleek Hang,

Whose pattens along the stone quay clang

In sailing time; whose pile is high

In the mart when the merchants come to buy;

Am he who lounges, blue-cotton dressed,

With petticoat, and a sailor’s vest;

Am he who dissimulates therein

The beard you see adorn my chin;

Am he who cumbers his lowly hulk

With refuse bundles of feeble bulk;

Turns sailor’s eyes to the weather skies;

Bows low to the master of merchandise;

Who hoists his sail with the broken slats;

Whose lean crew is scarcely food for his rats;

Am he who creeps from tower-top ken

And utmost vision of all men.

Ah then! am he who changeth line,

And no man knoweth that course of mine;

Am he, sir Sage, who sails to the sea

Where an island and other wonders be.

After six days we sight the coast;

And my palace top; (should the sailor boast)

Sail rattles down; and then we ride,

Mean junk and proud, by my palace side.

For there lives a junk in that ancient sea,

Where the gardens of Hang and his palace be;

O my fair junk! which once aboard

The pirate knows no living lord.

1

Its walls are painted water-green

Like the green sea’s self, both shade and sheen,

Lest any mark it. (The pirate’s trade

Is to hover swiftly and make afraid.)

Its sails are fashioned of lithe bamboo,

All painted blue as the sky is blue,

So it be not seen till the prey be nigh.

(Hang loves not that the same should fly.)

In midst of the first a painted sun

Gleams gold like the celestial yon.

In midst of the second a tender moon,

That a lover might kiss his flute and swoon,

Or maid touch lute at sight of the third,

Pictured with all the crystal herd.

So the silly ships are mazed at sight

Of night by day and day by night:

For wind and water a goodlier junk

Than all that have ever sailed or sunk.

Which junk was theirs: none fiercer than

My fathers since the fall of man.

So cotton rags lays Hang aside;

Lays bare the sailor’s gristly hide;

He wraps his body in vests of silk,

Ilk is as beautiful as ilk.

Then Hang puts on his ancient mail,

Silver and black, and scale on scale

Like dragons’, which his grandsire bore

Before him, and his grandsire before.

He binds his legs with buskins grim,

Tawny and gold for the pride of him.

His feet are bare, like his who quelled

The dragon; his feet are feet of eld.

His head is brave with a lac wrought casque,

The donning which is a heavy task;

Its lappets are spiked like a dolphin’s fin;

’Tis strapped with straps of tiger skin.

2

The passions of his fathers whelm

The heart of Hang when he wears their helm.

Then Hang grows wrinkled betwixt his eyes,

He frowns like a devil, devilwise.

His eyeballs start, his mask is red

Like to the last judge of the dead;

His nostrils gape; his mouth is the mouth

Of the fish that swims in the torrid south.

His beard the pirate Hang lets flow.

He lays his hand on his father’s bow;

Wherewith a cunning man of strength

Might shoot a shaft the vessel’s length.

I have another, of crimson lac,

Of a great man’s height, so the silk be slack.

The bolt departs with a brazen clang.

’Tis drawn with the foot, and the foot of Hang.

Such house and harness become me when

I wait upon laden merchant men;

’Twixt tears and the sea, ‘twixt brine and brine,

They shudder at sight of me and mine.

Of the birds that fly in the furthest sea,

Six are more strange than others be;

Under its tumble, among the fish,

Six are a marvel passing wish.

First is a hawk, exceeding great;

He dwelleth alone, he hath no mate;

His neck is bound with a yellow ring;

On his breast is the crest of an ancient king.

The second bird is exceeding pale,

From little head to scanty tail;

She is striped with black on either wing,

Which is roselined, like a costly thing.

Though small the bulk of the brilliant third,

Of all blue birds ’tis the bluest bird.

They fly in bands; and, seen by day,

By the side of them the sky is gray.

3

I mind the fifth, I forget the fourth,

Save that it comes from east and north;

The fifth is an orange, white-billed duck;

He diveth for fish like the god of Luck;

He hath never a foot on which to stand,

For water yields and he loves not land.

This is the end of many words,

Save one, concerning marvellous birds.

The great-faced dolphin is first of fish,

He is devil-eyed and devilish.

Of all the fishes is he most brave:

He walks the sea like an angry wave.

The second, the fishes call their lord.

Himself a bow, his face is a sword:

His sword is armed with a hundred teeth:

Fifty above and fifty beneath.

The third hath a scarlet suit of mail.

The fourth is naught but a feeble tail.

The fifth is a whip with a hundred strands ;

And every arm hath a hundred hands.

The last strange fish is the last strange bird.

Of him no sage hath ever heard;

He roams the sea in a gleaming horde,

In fear of the dolphin and him o’ the sword.

He leaps from the sea with a silken swish.

He beats the air, does the flying fish.

His eyes are round with excess of fright,

Bright as the drops of his pinions’ flight.

In sea and sky he hath no peace,

For the five strange fish are his enemies.

And the five strange fowls keep watch for him.

They know him well by his crystal gleam.

Oftwhiles, sir Sage, on my junk’s white deck,

Have I seen this fish-bird come to wreck;

Oftwhiles (fair deck !) ’twixt bow and poop,

Have I seen that piteous skyfish stoop.

4

Scaled bird, how his snout and gills dilate,

All quivering and roseate!

He pants in crystal and mother of pearl,

While his body shrinks and his pinions furl.

His beauty passes like bubbles blown;

The white bright bird is a fish of stone.

The bird so fair, for its putrid sake,

Is flung to the dogs in the junk’s white wake.

II

Have thought, son Pirate, some such must be

As the beast thou namest in yonder sea.

Else, bring me a symbol from nature’s gear

Of aspiration born of fear.

Hast been, my son, to the doctor’s booth

Some day when Hang had a qualm to soothe?

Hast noted the visible various sign

Of each flask’s virtue, son of mine?

Rude picture of insect seldom found,

Of plant that thrives in marshy ground,

Goblin of east wind, fog or draught,

Sign of the phial’s potent craft?

’Tis even thus where the drug is sense,

Where wisdom is more than frankincense,

Wit’s grain than a pound of pounded bones;

Where knowledge is redder than ruby stones.

Hast thou marked how poppies are sign of sin?

How bravery’s mantle is tiger skin?

How earth is dark and dumb with care?

How song is the speech of all the air?

(Thou hast ? Thou’rt wise in thy sailor kind.

Not every fruit is known by its rind.)

I’ve a truth distilled and strained and casked;

Thou hast brought the symbol it sorely asked.

(Thou’rt wise, son Hang; mayhap thou know’st

Though truth be much, its sign is most?)

How deep man’s heart, in its symbol truth

Is hidden;—and this is the art of sooth.

5

A tree is the sign most whole and sure

Of aspiration plain and pure,

Of the variation one must wend

In search of the sign to the world’s wide end.

Thy fish is the fairest of all that be

In the throbbing heart of yonder sea.

He says in his iridescent heart:

I am gorgeous-eyed and a fish apart ;

My back has the secret of every shell,

The Hang of fishes knows me well;

Scales of my breast are softer still,

The ugly fishes devise my ill.

He prays the maker of water-things

Not for a sword but cricket’s wings;

Not to be one of the sons of air;

To be rid of the water is all his prayer.

All his hope is a fear-whipped whim,

All directions are one to him.

There are seekers of wisdom no less absurd,

Son Hang, than thy fish that would be a bird.

6

THE REDEMPTION OF DURTAL*

HUYSMANS has treated the subject of repentance;

rarest of all perhaps in pure literature. The degree

of the treatment, if such an expression may be used,

makes the new book peculiar; certainly as prose and

fiction: the penitent being a man of profound baseness;

the spiritual progress being narrated both as far as an

author dare, and as exhaustively as skill and patience are capable.

The friends between whom he isolated himself intellectually, des Hermies

and Carhaix, dying within two months one of the other, Durtal is thrown

upon silence and solitude. From the desolation immediate upon his loss,

by way of a projected life of Blessed Lidwine, he comes to a point of

spiritual uncertainty, that is to say, to the only spiritual situation possible

for him. Then begins the story of any conversion in the world’s memory,

not restricted to the era of grace.

Durtal, with his history of the Maréchal Gilles de Rais, Durtal, who

goes the length of digging up the Satanism of the Middle Age from

modern cloaques of revolting depravity, whose vanity it would have been

to be the last possible recipient of grace, is the object of an “attouchement

divin.” This is the spiritual crisis well known to what is called Mysticism,

the science which, for want of a name, has taken this most misleading of

all names. The germ once planted grows with irresistible force, so assumes

the direction, so absorbs the attention, of Durtal, that suddenly he is aware

only of the fact that he believes, as he says, with not a trace in his memory

of any step by which he has passed from the lethargy of decay to the

anxieties of a living growth.

Then it is a ravenous pursuit of all the spiritual writings the Romance

languages hold, from Saint Denys the Areopagite to Father Faber (a

reservation later), a restless pilgrimage through all the churches of Paris.

The torment ensues; the struggle of habit with the inexorable, unknown

impulse; till agony drives Durtal to an earlier acquaintance, the abbé

Gévresin. Follow the conferences of the two men, the one deeply skilled

in the malady, the other floundering in all the helplessness such a patient

can exhibit. The great stage is reached when, through means of the

abbé’s monitions, Durtal, at length pushed by a power he feels has taken

possession of his very will, goes into a retreat with the Trappistes, makes

his confession, is absolved and communicates. The ten days passed at

La Trappe occupy half the book.

The record is closely consecutive; digressions are few and under the

direct warranty of M. Huysmans’ art. The bridge-work from LÀ-BAS

is such as might be expected from so accomplished a writer; the

solidification of the setting in which Durtal has to move bears the cachet

of the Magician. Elaborate information, pitiless visual observation, a

rare sensibility, under the play of an obstinate method, which advances

fearlessly upon the longest category, ready at each shift with a more

*J. K. Huysmans, “ La-Bas.” Paris : Tresse & Stock, 1891. J. K. Huysmans, “ En Route.” Paris : Tresse & Stock, 1895.

7

exasperated epithet, lacerate every scene, make nervous and vibrant each

of the panorama before which the haggard, despicable hero is for ever

hounded.

Above all, what is seen is through the eyes of Durtal; the comments

upon the scene are those of the deteriorated Sensitive. M. Huysmans

has not hesitated, in the enthusiasm of his subject, to expose the genus

scriptor as few who know the truth have the courage to do, priggish,

vulgar. Here is the perfection of the attempt less perfect before, to present the

baggage of the écrivain with his finical person; M. Huysmans evidently

agreed with his friends’ verdict on LÀ-BAS in this feature, for now

complete fusion has repaired the earlier fault.

Choice must be recognised in the circumstance of Durtal’s conversion

being brought about in the lap of the Church. Hence (and of course

it could have been effected directly) applause falls to the judgment

of M. Huysmans. What a bait to his talent the modern, actual aspect

of the Church, its agglomerations of styles and traditions ! The sen¬

sitiveness of Durtal discerns a whole new facet of a mysterious gem

at any moment when he is set down to assist at an office. Hearing

the voice of a priest whom he cannot see, he can speak of “la vaseline

de son débit;” and at the same time find the due expression of the

plain-chant a worthy pursuit of a life-time. Its architecture and

structural accessories; its images, music, liturgies ; the orders of religious,

their dress, rules, even pronunciation; the amount of light, the smell,

the quality of the worshippers; nothing about the Church which is not

of deep interest. But nearer yet to the author’s purpose the Church is of

vital importance to Durtal; during the period of his spiritual conval¬

escence it gives him something to do. Without its insinuations, its

constant allurements, its demands upon the laborious attention of the

sufferer, it is safe to say EN ROUTE could not have been written; as it

is M. Huysmans is obliged to resort to a fully pardonable deceit, and

simply omit to mention what Durtal did with the great part of his day.

Having chosen the Church, M. Huysmans shows further wisdom in

keeping his hero to an orthodox route. Here again he tacitly asks

indulgence of the interested reader, and surely not in vain. As a matter

of fact, Durtal, as we have been brought to know him, could not have

been kept away from the Heresies. M. Huysmans’ caution, in view of

this certainty, is extreme. Though one or two German mystics (out of

scores) are named, Dr. Tauler, Suso, the two Eckharts and Catherine

Emmerich, not one (save the last) is suffered more than a mention by

Durtal, for the reason that these are the door of ceremony to the most

absorbing of the heresies. Durtal among die Brüder des freien Geistes!

Durtal with the history of der Gottesfreund vom Oberland in that valise

of his, with the chocolate and the laudanum! The most remarkable

“attouchement ” ever recorded, that of Tauler, cannot be alluded to.

Catherine Emmerich, for reasons, falls across the hard boundary; she is

almost alone in this century a mediaeval visionary and stigmatisée; the

passion of her life and utterances is all an excuse, in face of a tactic

8

however severe. But doubled discretion has to forbear carefully from

mention of Clemens Brentano; lest Durtal, studying the voluminous diary

of nine years’ daily intercourse with the illuminated sister, should recog-

nise himself in Clemens, himself with more aplomb, more verve, and lose

his road beyond hope.

The whole scheme of this history required a certain harshness, dryness,

poverty. Much had to be sacrificed to the purpose of making a novel

of such a subject. This accounts for here and there the begging of a

question. M. Huysmans holds the novel form to be almost as exacting

as that of the sonnet. The length of the book determined from the

outset within the limit of half a page, the need for proper balance of

all the considerations the novelist has to bear compels him to set his

face sternly against any but the most urgent situations. Add to all the

proper restrictions of the form M. Huysmans’ deliberate rejection of the

symbol. This is the writer of MARTHE, EN MÉNAGE,the unflinching

realist, whose faith is that his system can employ all possible subtlety.

One example of dexterity in turning humble circumstance to beauty,

of skilful determination, by simple refinement of observation, of the

hour, the vibration of the atmosphere, the pulse even of the supposed

observer: Le temps était tiéde, ce matin-là; le soleil se tamisait dans le

crible remué des feuilles ; et le jour, ainsi bluté, se muait au contact du

blanc, en rose. Durtal, qui s’apprêtait à lire son paroissien, vit les pages

rosir et, par la loi des complémentaires, toutes les lettres, imprimées à

l’encre noire, se teindre en vert.

One brilliant episode suffers quotation by its shortness:

II faisait nuit noire; à la hauteur d’un premier étage, un œil de bœuf

ouvert dans la mur de l’église trouait les ténèbres d’une lune rouge.

Durtal tira quelques bouffées d’une cigarette, puis il s’achemina vers la

chapelle. II tourna doucement le loquet de la porte; le vestibule où; il

pénétrait était sombre, mais la rotonde, bien qu’elle fût vide, était illuminée

par de nombreuses lampes.

Il fit un pas, se signa et recula, car il venait de heurter un corps; il

regarda à ses pieds.

Il entrait sur un champ de bataille.

Par terre, des formes humaines étaient couchées dans des attitudes de

combattants fauchés par la mitraille; les unes à plat ventre, les autres à

genoux; celles-ci, affaissées les mains par terre, comme frappées dans le

dos, celles-là étendues les doigts crispés sur la poitrine, celles-là encore se

tenant la tête ou tendant les bras.

Et, de ce groupe d’agonisants, ne s’élevaient aucun gémissement, aucune

plainte.

This can only delight, not surprise, coming from the master of this mode.

And though it will inform no one, the flawlessness must be noted of the

nevropathy which is so important a feature of the book.

Of the study of Durtal himself one feels that, isolated, it would have

been more interesting than the whole presentment as it stands. The frag-

ment of a spiritual career is exact enough to support the application of the

9

gauge, the maxim actually cited : La Mystique est une science absolument

exacte. It is necessary to remember that what is given us is really only a frag-

ment ; not, as the ignorant are certain to say, the whole course and exhaustion

of spiritual operation in a man; a fragment, to speak truly, quite elementary,

and scarcely spiritual at all in results.

All through, Durtal remains deeply ignorant of what is taking place,

when a very small amount of insight in the study of the books with which he

thinks himself saturated should at least sometimes inform him. All the

utterances of the saints he has the fortune to fall among are servilely

reported by him, with never a word of spiritual criticism on his part, not

even the most rudimentary. We do not find him ever admitted to the

simplest “communion of saints; “the impulse within him, the “touche

divine,” the “angelic influx,” the “Kingdom of God,” Goethe’s “dämon-

ische,” to cite a few of its thousand names, never says to Durtal directly

anything more complicated than: Do what this man tells you. He is always

in the wretchedness of his spiritual beggary. What really surprises is that

he should not blunder upon the first truth of an awakening, that he must

go back over the way by which he came. Usually this is easy to a man

who has been so wicked as Durtal; the keen quest of infamy being extra

physical in some aspects, a mode of inverted spiritism, in a manner to make a

spiritual process seem known already the moment it is suggested.

He is found constantly looking, stupidly, for a miracle to take place in

him, a violent destruction of his past, the swift summoning to being of

some fruit of long, laborious growth. The “attouchement” is not miracle

enough for him. He craves, in his peculiar vulgarity, in the vanity of his

worthlessness, a theatrical sign, an explosion of redemption and miraculous

repair, an alchemistic operation in favour of his rag of spiritual disposition.

The only reflection he can make upon the contemptuous refusal of the

abbé to work in his behalf as he considers himself entitled is a culinary:

tons ses conseils se réduisent à celui-ci; cuisez dans votre jus et attendez.

Herein is seen the fidelity of the author already remarked, not to let

wriggle out of sight the radical vulgarity of Durtal. His basest sophistry

does not make him contemptible enough; the real bitter drop he is forced to

swallow again is his vulgarity: . . . ces messes gargotées comme l’on en cui-

sine tant à Paris . . . ils me verseront à pleins bols leur bouillon de veau

pieux! . . . Ses chantres y barattent une margarine de sons vraiment ranees!

Durtal has much to say upon all the graces and exquisitenesses, a great

deal about the Primitives; for every sound he will have an epithet at all

hazards, often drawn from a mute source. But at every few pages the

reader falters upon the reiterated signature of one of these unpleasant

metaphors. Durtal, further, had exhausted the paregoric virtues of the

Gospels. Saint Bonaventura condense en unesorte d’of meat des modes pour

méditer sur la communion. The reward of translating this criticism upon

Saint Bonaventura is the image of a little tin box containing a disgusting

chemical aliment.

The Trappistes were right who told Durtal that every wonder was small

beside the fact of his being in any disposition of penitence soever. The

10

great thing for Durtal was to be kept ignorant of his real state and pros-

pect; it would have been very little encouraging for him to know. His

confessor at La Trappe told him that he had been so sick that one might

say of his soul: Jam fœtet; he did not tell him that no other thing could

be said of his body. The body of Durtal is as lost as is possible; there

is no more hope for that. The soul of Durtal has to make a journey so

long that a view of it would ruin him. At the point of utmost progress

in EN ROUTE he is at the beginning of the purgative life. In a very long

time he will still be at the beginning.

11

A PRAYER TO VENUS.

MARVELLOUS Venus, listen, please,

For all comes back to me again,

While in the limes the pilfering bees

Hum, as once did each suburb-lane

Where loitered idle mercenaries.

For thou wast very good to me

Long since when war was in the land

And with loud quarrels soldiery

Made it unsafe for girls to stand

Changing their chatter fair and free.

Then was I precious in all eyes;

And to thine own men would compare

Her charms, who, with a prim disguise

Of glee that knew they needs must stare,

Noticed no jot their courtesies.

For one, my lover recognized,

I fancied no neglect too much,

And overweening tantalized

Him, till my sister’s hand would touch

Mine, pitying so where I despised.

We slept in one room, she and I

With cousin Portia, and they had

The double-bed; for I would lie

Distant, but desperately sad,

Upon a pallet separately.

How oft, disdaining friendly chat,

I stripped apart and slipped to bed—

A queen who could not stoop to that—

Whose heart, dead for each ‘Dear’ they said,

With every kiss went pit-a-pat.

Between chill sheets I lay and ached,

And heard their twin breaths tuned to sleep;

Nor might my longing’s thirst be slaked

By tears which crossed my cheeks, in deep

Self-pity hushed for fear they waked.

Past cornice pillarets I watched

The moon’s proud progress, till I rose

And slow the lattice-door unlatched:

The lamp shook, but I kept it close

Lest from their dreams they should be snatched.

12

When I looked forth, all—all was white,

The up-hill fields, the well-worn road;

Clover with scent had filled the night;

Though far Vesuvius’ crater glowed,

Hay-cocks seemed snow in that wan light.

Nor thought I if, nigh yon fierce glare,

Watching the wild spark fly the flame,

Thou, wrapped at full length in thy hair,

Musedst how many maids, who came

To no good end of love, there were.

All wintry—save one leafy mass

A gust left fondling, to escape,

Kiss my feet cold as in mown-grass

Dead flowers, and thence from heel to nape,

Estranging skin and gown, to pass.

“The moon’s is sheer attractiveness”

I thought “—Gives light but doth not love :

Beauty was meant, may be, to bless;

But can it e’er be blessed enough?

Day’s is such spend-thrift kindliness:—

Swallows with grace, from hammock-huts

Cemented neatly to the wall,

Plunge through light, where the pigeon struts,

As gem-like plumes could never fall.—

Sleep on mere prettiness Night shuts,

Nor brooks a bird her realm serene;

’Twixt mirror-waters and the moon

No forward females intervene,

Nor lass nor lad with lilted tune

Vexes complacence in their queen.”

I closed the shutter, and then turned

With face which, like the moon come close,

Wan from my mirror vaguely yearned;

Then screamed with bare foot on a rose—

His gift which last eve had been spurned.

They woke—I leapt back into bed:

They stared about still dazed with dreams.

“Ah, did you hear it too?” I said,

Feigning to wake at mine own screams,

Squeezing my smarting foot which bled.

13

At first we listened breathing hard,

Then talked ten minutes at the most;

They guessed ’twas some cat in the yard,

But I was sure it was a ghost:

Their dreams were very little marred.

I learned, while they new slumber drank,

My heart had found a voice which wooed

Pillows to life: as drowsed I sank,

Mine seemed plump roosting doves who cooed,

And my head cuddled into rank.

Then dreams through calm night didst thou fling—

Tumultuous birds of passage, borne

From Paphos, battling on the wing

Past Pompeii, till red, at dawn,

Showed villa-rooves with blood-shedding.

My feather-head to penance woke—

Sore plots to hide sheets stained by blood—

With furtive kisses to revoke

Threats that thy trampled deep-wronged bud

Made, flushed like highly-angered folk.

Of such portentous rain the talk

Was awed to whisper all day long—

I saw poor mother white as chalk,

When my joy burst the gates of song;

For he had won me on our walk.—

Marvellous Venus, crowned by time

My locks are white as moon-lit snow,

My children’s chubby children climb

Up by my knees, to sit and crow

Perched on the ruin of my prime.

For one thing I petition thee:—

While generations from these rise,

Let me ne’er lack heiress, to be

Like, as maid may, to her whose eyes

For peril far surpass the sea.

14

THE BEAUTIES OF NATURE.

IN one of the sweetest valleys of Cumberland, far up

beyond that celebrated vale of Troutbeck—in fact,

a very beautiful valley—lived a careful and sin-

cere sheep. The mountains were not crested with

flame at dawn, nor veiled with mist at evening,

in vain for her. In her vale and about it Nature

was at once radiant and sober. On the one hand

an isle-strawn mere lay laughing, cradled in the

bosom of the mighty hills: these were stern of

temperament and laughed but seldom; even when repentant skies crowned

them with rainbows about their tangled foreheads, they drew down their

brows, and, recalling their Point of View, still frowned. The grandeur of

their awful steeps was sweet in harmony where mosses and scant grass

cloaked them; and stranger where the patches of bracken mottled their

gray nakedness. Leftward and deeper yet, the fairest, smoothest valley,

with fields so green, so green; green touched according to the season with

pink, with mauve; touched with yellow, with gold; touched with I know

not what of all that was loveliest and best. Torrents rushed in gorges

of the steep slopes, bubbling and all but dust for their violence, or loitering

in cool, deep, faintly swirling pools, shaded or open to the magic sun, whose

rays came to play with the rillets in pure fire, or damped through shim¬

mering green of fern frond and dainty leaf. And down below, a timid

riband of peace parting the giants who had stood threatening one another

since the world was founded, ran a very brook of Eden; its purity mocked

the bluest noon, its glance was brighter than rain in summer: it was paved

with gold sand and silver pebble. Along its woolly fringes the brightest

flowers grew on stalks more slender than anywhere else; and here the

richest moths balanced themselves on the quivering stems, forecasting in

secret accident the blossoms of Paradise. With the single exception of

glaciers, no beauty was wanting in this valley which a sheep could think of

to desire.

In the fulness of accomplished time God sent this sheep a lamb for her

own. Herself was white, as often depicted in literature; God had given her

lambkin black legs and tail, a black face and most dutiful eyes. Long the

sheep tended and watched her young, suckling it with joyous, over-brimming

tags.. Then tenderest grass was alternated (of tender grass there was no

lack in that fat vale). Sometimes the lamb grew faint and querulous, trotting

after his mother with cries not all content. Then the sheep tinged her kind¬

ness with severity; for she was sincere, and the time comes when a lambkin

must think of becoming a lamb.

“My child,” she would say, “admire the Beauties of Nature,” and thereon

would follow indications suited to a juvenile understanding, the contours of

the crags against green or blue, the swooning dip of the kindly hills. So

the lambkin became a lamb, wise in his order, wotting well for what he had

been born into the world.

In the valley there was an old father. He never spoke to the lamb, but

15

he looked as though he knew a great deal. The lamb was afraid of him, for

he had a terrible way. He was horned; that was not curious, but each of

his horns grew out in a spiral from his head; and his manner was, when he

looked, to look through this spiral with one forbidding eye. No wonder the

lamb was afeared.

At night all the sheep, with their lambs and the old father, went to their

fold which lay lower down, a rock-piled fortress of two apartments, one of

which was larger than the other. The lamb did not know why, but always

the whole flock went into one of the rooms, generally the smaller; they

never shared them. The openings were very narrow, for one only to pass

at a time, but the sheep always went through two, and sometimes ten, abreast.

All rose very early in the morning; and with restored energy scrambled

high up the slopes, so that looking over their shoulders from time to time

they could see the level sun driving loitering night down the vale.

“I have been wondering all night, mamma,” said the lamb one morning,

with that mealiness of demeanour proper to obedient children, “I have

been wondering all night….”

The sheep looked earnest, for he had slept soundly.

“I have been wondering all night whence I came into this happy valley,

to be my mother’s joy by filial obedience, and admire the Beauties of Nature.”

The sheep was not embarrassed for an answer. But she looked round with

care, that marked circumspection might give the lamb a sense of the dignity

of their conversation. The direct answer was simple: that he came from God;

but, considering the extreme youth of her child, she said, pointing with her

ear:

“Do you not see yonder, where the mere head of a lamb is seen above

the herbage, or yon where head and shoulders are seen, or there again added

a white fleecy back; and here are you and I walking about, free and happy,

the fairest of God’s creatures. Therefore, my son, let us eat, and from time

to time look about us to admire the Beauties of Nature. The mountains,

children of time, are emblems of eternity; the white, shining lake we see

down there is a symbol of truth. The sky above us is a beautiful figure of

changing life, which is always blue again sooner or later, however many

clouds cross its bright face. Lastly for the present, the grass, for ever green,

means love, which is the best of all. Now, son, let us eat.”

This wisdom filled the lamb with such sobriety and reflection that he knelt

down to eat his breakfast; and, as it was more convenient, so continued for

a long time. The sheep said nothing, but seeing these things, she thought

with her heart.*

“And whither, mamma,” asked the lamb, on another occasion, “if the

question be a right one, do we go?”

“The question is a right one,” answered the sheep gravely, “ and in a

sense the answer is writ on all we see about us, on every feature of the face

of pious, happy Nature. And, with more precision, thus much may be said:

If we are good and eat a great deal, we go away singing in joyous bands,

led by piping hinds and tanned boys, into valleys more fair than this, though

* Vauvenargues: Les grandes pensées viennent du coeur.

16

now that may not seem possible, where grass is greener and moist, though

the sky above is always blue. It has been wisely said that there is no telling

the wonder and contentment which await us.”

These assurances almost completed the lamb’s education, at least, so far

as his mother was concerned; but still they conversed together as loving

dam and dutiful child. One day the pasturer came into the fold, and taking

the lamb, not without rudeness, painted a fine legible “P. F.” on his white

back. The lamb resented this and showed a certain quarrelsomeness, object-

ing to his mother that a red “P. F.” was a blot on the face of Nature.

“Peter Fancy,” laughed the sheep, in matronly banter, “there are other

things beside Nature, Sir Peter.”

Then, little by little, the lamb trotted less and less closely at his mother’s

heels. On occasion he was known to dictate to her, and his observations

were sometimes conducted without her connivance, and communicated first

by him to “people of his own age.” He gave himself moods, being some¬

times archaic, and sometimes merely pastoral. And last of all, when by

chance they met, mother and son conversed only in monosyllables. The

lamb had found his own pursuits, and he followed them.

17

ON A PORTRAIT BY TINTORET IN THE COLONNA GALLERY

AN old man sitting in the evening light

Touching a spinet ; there is stormy blow

In the red heavens, but he does not know

How fast the clouds are faring to the night:

Hehearsthe sunset as he thrums some slight

Soft tune that clears the track of long ago;

And, his musings wander to and fro

Where the years passed along, a sage delight

Is creeping in his eyes. His soul is old,

The sky is old, the sunset browns to gray;

But he, to some dear country of his youth

By those few notes of music borne away,

Is listening to a story that is told,

And listens, smiling at the story’s truth.

18

THE WRITING ON THE WALL

IT was when Sandro Pazzo had seen Diana Rossi

for the third time, upon his fourth visit to the

painter Bonaventura, that he thought of her as

possible inmate of that old grey castello high up

in the Umbrian hills, visited by few save the

birds at early dawn and sunset; on the shoulder

of a ridge it stood, buttressed well and loop-

holed; its one tall watch tower looked down the

valleys and caught the first sun-rays on its face

from over that marsh-land where Arno flowed

seawards. Fifty years before, his people had held it against the Floren-

tine soldiery, and when peace came with honour, it ceased to be a refuge

for the bold spoilers whose son he was. A fine lonely place to guard a

fair woman in, and he desired with all his smouldering heart the beauty

of Diana Rossi.

It was to him evident that she was passionately fond of that ascetic

young painter, who lived easily within the limits of his earnings and had

painted her fair face into the glory of Madonnas and Saints;—it seemed

evident also to this Sandro that such asceticism was not destined

to exist much longer in the glow of her frequent presence, though it

was much to be doubted whether, in the impending conflict between

the spirit and the flesh, the spirit might not at last painfully win back

its high, solitary life again. Bonaventura, in the pure aims of his first

youth, had achieved so successfully the joy of artistic creation that it was

doubtful whether other things could finally prevail against it, even Diana,

who was to that creation one of the most powerful aids. Single-hearted

enthusiast, he worked from morning till nightfall among his panels and

paints, often too sang tunefully as his hand moved, while Diana sat

before him, weary of last night’s pleasure and feasting, envying the

simple happiness of the man who lived hermit in gay Florence. A

slight bond of cousinship was between them, but no true bond of race.

His blood flowed with Northern calmness, hers ran with Southern

changings of languor and fierce energy. Thus it was reposeful to her,

when tired of the crowded life elsewhere, to come hither and sit in the

cool painting-room, and to see the repetitions of her growing in beauty

and colour, while she tuned his little cithara and touched faint melodies

hardly heard in the far corner where he sat. His welcome, so cheerful

and unchanging, refreshed her ear after the flattery of the rich youths

from Pisa who wore jewels in their sword-hilts and fur on their mantles.

In fine, the plain self-contained life had a passing charm for her luxurious

senses, and Sandro Pazzo saw in her eyes, when the painter spoke to

her, a look, of which he knew the meaning.

True it was that, by some caprice of blood which made it none the

less when it came, a passion for the young man was arising within her.

Only by a caprice of sudden change from things naturally most pleasing to

the pleasure-loving heart could this be, that the ruddy-haired girl, bold-

19

eyed, fond of sumptuous places and of revelry, should care to come here

to her cousin’s bare room, where the gentle, bloodless enthusiast sat

working, wrapped in a thick mantle, save in the very hottest days of

summer. But so it was; often and often had he made his canvas

precious with her beauty, and thus it was a regular custom of her life

that she should sit there during two or three afternoons of each week.

He was not of a mind or bodily make to join in the banquets her father

gave to his clients and customers in the double part of banker and gold¬

smith, so he visited the Rossis at odd times, when his work was done.

And there was in him so little of the worldling, that he and his worldly

cousin became friends, in an accidental, easy-going sort of way. Neither

had first sought it. His mind was so enwrapped by the enthusiasm for

his art that he had no room therein for other passion or impression;—

if anything so came to him it was as a picture, and as such he would paint

his way through it, loving the picture at last so dearly that he had but a

faint feeling remaining for the original human creature whence he had

drawn his ideal.

Indeed, it is not natural that such a one should care greatly for his

raw material when there is always the finished result of his labour in the

future; be that as it may, Diana produced no effect upon Bonaventura

other than that of a friendly feeling for a valuable assistant, for this she

was, now that his type of Madonna was becoming famous. And this

gave him a unique position in her eyes. The influence upon her was

good, for she had been a spoiled child and was now a wilful woman, and

to respect anything was much. For some unknown cause the respect

had gone hand in hand with easy comradeship till now, and Sandro

Pazzo, who had studied men and women in many other cities, saw that

the comradeship was, on her side, no more.

Now here it was that Sandro, being too cunning, made his mistake.

He thought that Bonaventura must be one of her many adorers, under a

mask of coldness, —thought that the visits of Diana to him were but a

way of intrigue, bolder than those usual. He was wrong. He could

not understand that man, who, though young and kindly, was thoroughly

and virtuously simple in his life, partly from his very feeble frame, which

at times was tortured by prostrating illness, partly from real purity of

heart. Such folk are rare, yet they do exist, as do other strange things

in this earth, and Sandro’s mistake was in applying common worldly

wisdom to the judgment of him. Men such as Sandro can see worldly

motive in the simplest and most innocent of mortals; the price they pay

for their knowledge of men’s badness is the frequent blindness to the

gold streak amongst the worthless stone. To them it is but brass, if

indeed they see it. For this reason Sandro chose to expend the strength

of secret hatred on Bonaventura, as time went on and he felt himself to

be growing older.

Sandro Pazzo’s full name was Alessandro Patezzi, Count of Castello-

calvo. No one called him Pazzo when he was by, because it was a

nickname, given on account of his odd fondness for curious medical and

20

alchemic studies. Never had he been quite like other men, though none

could attribute to him the ascetic life of Bonaventura. He had stayed

long in Padua and learned much lore in that place, he had travelled

much, eastward, westward, always in a secret, solitary fashion, speaking

little of his experience, even when asked to do so, and taking no part in

the petty wars and state schemes which occupied most nobles, great and

small. Which, however, did not prevent his knowing much of what

was doing and keeping on friendly terms with the ruling powers, for

Mad Sandro did not wish to be brought to poverty through any neglect

of the things so important to most men.

Thus his madness, as it was called, did not bring upon him the con-

tempt of his fellows, but, on the contrary, a respect which became mingled

with fear on the increase of acquaintance. The Count of Castellocalvo

was like most other nobles, a man best not offended.

He spent his summer-time at his castle up in the hills, where cool

winds wafted down the valley. There he read the books he had collected

and passed the time in his own devices, in a separate tower or a certain

room cut into the rock, and peeping out by one window over the cliff-edge

into the vale below, a cool and pleasant place on hot days. Before he

knew Diana Rossi he had been wrapped up in his pursuits, indeed much

as Bonaventura, but more passionately in that his temperament was

ardent and his frame that of the wiry mountaineer parents whence he

was born. Since the death of his young wife many years ago, he had

effectually tamed his sorrow for her loss by his violent studies, and now

as his manhood hovered on the border of old age, behold! the acquaint-

ance with Diana had been potent to inflame him with passions of youth.

So he schemed and plotted, and at last became very friendly with

Diana and her cousin; frequently did he visit the painter’s room in the

warm afternoon, and as often as not would lend his face to Bonaventura

for one of the Magi Kings in a Nativity picture. When the sitting was

ended he would tell travellers’ tales, or they would sing all together while

Diana touched the cithara, and had it not been for his passion he could

have felt that such pleasant comradeship was as good a thing as a man

might desire in life.

For when you become a traveller and set foot every night in a

strange hostelry, it is then that you shall come to put away the taciturnity

of the absorbed scholar. A man talks little to those whom he has known

all his life, or to those whom he has cause for disliking. But when he

has voyaged somewhat over land and sea, and come into perilous places

and passed through many tedious ones, and found how large a share of

a traveller’s, ay, or of any other man’s life, is ruled by the accident of

chance acquaintance, then it is that he comes to prize the pleasure of

talking easily and at random with his fellow men and women. Would

that sunny day in some German city have left so pleasant a remembrance

in Sandro’s mind had the old book bought under the arcades drawn no

one of the passers-by to stop and chat with the queerly-garbed foreigner ?

. . . . And even if Meister Albrecht Diirer had taken the other turning

21

and had not met him after all, might not some other man of scholarly

taste have spoken to Sandro and, in the momentary crossing of their life-

path, discussed Paracelsian mysteries with him? How barren, by com¬

parison, would that day have been had no one spoken. And what

pleasanter thing for three such travellers on the journey of life as the

scholar-nobleman Sandro, the incomparable painter Bonaventura, and

the beautiful woman Diana Rossi, . . . that they should meet for many

days in a room filled with the presence of fine work and should regale

one another with tales, jests, and all manner of good conversation!

Yet perhaps it is but in mortal nature that, having a good thing, man

should at once proceed to mar it. Thus the passion-inflamed Sandro

regularly met his friends, and while adding his part to the cheerfulness

of the hours, meditated how to get his desire, and watched the right

moment to remove the innocent painter without suspicion.

For he was not so foolish as to tell Diana of what burned at his

heart. He knew that she was not now in the temper to listen to such a thing

from him, let alone show him any favour. Day by day he watched her,

and noted the tones of her voice as she spoke to Bonaventura, and the

tremor that ever and anon ran through its melody as with a subtle pain.

Sandro would have given his castle and his fortune to have had her

speak so to him, for it meant that the passion for Bonaventura was

working sorely within her. But the painter was cheerful ever and

serenely unknowing of it; the speech which Diana addressed to him

alone he answered as if it had come from the two, so that after awhile he

was the most frequent of the three to speak. Meanwhile his work went

on and his fame grew apace.

Now the fresh warmth of the late spring was past, and the hot days

had for some while been on the city, when on a certain afternoon the

three friends met in the painter’s room. It was the first time after an

interval, which was caused by the severe illness of Bonaventura, who

now again sat at his easel, looking weak and ghost-like, but happy in his

work as ever. He had sent messages to his two friends, for they were

now very dear to him, and one of them was coming,—prepared for

business.

This was Sandro, the first to enter, his face, so baked and meagre,

with its worn character deeply stamped round the mouth and eyebrows,

looking at once strangely old and strangely youthful. For in his eyes

lived the brilliant hunger of expectation, and the eyes are fed by the

heart.

“Ah! greeting, my friend!” said he; “the sun has roasted me rarely.

I am glad to be here.”

Bonaventura looked up smiling, and waved his brush in reply.

“You are welcome,” he said, “very welcome. The wine stands on

that shelf at your right hand; I thought you might desire something to

wash the dust out of your mouth; have you any fresh songs? -Sing

something, pray, and I will sketch you meanwhile. For I have an

idea.”

22

Sandro drank and wiped his mouth. “Well, well. What shall it

be?” So, as the painter made no reply, but chose a piece of paper and

took his quill in hand, Sandro jangled a chord or two, and as in thought

he slowly glided into this strain:

Tell me, O Hills, and tell, ye merry Birds,

Tell me, O Brook, that tinklest down the stone,

Know ye the sorrow that my heart engirds,

Hopeless to love, and brood on Love alone?

Know ye what woe Love silent must endure,

And is there aught that such a pain may cure?

To me replied the Hills, replied the Birds,

Replied the Brook that murmured by the stone,

“Alas, a hopeless Fate thy heart engirds

If one thou offerest Love for thee hath none.

We know what woe Love lonely must endure,

We know of Naught that such a pain may cure.”

“Bellissima!” murmured Diana’s voice from the doorway, and

Sandro’s hand trembled as he rose and placed the cithara in her arms.

“It is very sweet indeed,” said Bonaventura, “—and so veryvery applicable

to you, my friend! ” and he laughed gently, but suddenly stopped on

finding that the others did not accompany his mirth. Only Sandro’s

mouth spread out into the line of a smile without creating one, and

Diana bent her head over the instrument and tuned a false note.

“Will it please you to sit down as you were, just for a moment,

Messer Sandro ?” asked the painter in his most courteous tone, for he saw

he had made some mistake, and, though no courtier, was not so foolish

as to lay stress upon it by asking pardon in Diana’s presence,—“ it is a

fine pose, and you shall see in a day or two what I intend with it. Indeed

there is no reason why I should not tell you now. I am going to turn

you into an angel, Messer Sandro, by putting some flowing drapery on

your form and pair of wings on your back. The other day when I looked

at your face as King Melchior I said to myself, ‘surely this is not quite

the best which I have seen in my friend’s face?’ and then I could not tell

why I thought so, for King Melchior was a scholar like yourself, and had

travelled much. I thought about this all the time of my sickness,

without coming to the reason. But yesterday evening I found what my

thought contained, it was the memory of what you had told me of your

voyage to the East, and of the good men who dwelt in the mountains of

the wilderness. And it then seemed to me that it was fittest to paint you as

the angel who sat at the entrance of our Lord’s Sepulchre and told them

who came of the wonderful things they had not before known.”

“See,” he went on, arising and showing the little sketch, besides which

he had roughly indicated the idea of the picture, “do you not think it

better than the other of King Melchior?”

23

Diana sat playing a lively air on the cithara, a melody of the streets,

but she raised her eyes as Bonaventura walked across the floor to her

and Sandro, and cast a glance at it. “How quick you are!” she said,

and went on playing as before. She also looked full into his eyes for one

moment, and Bonaventura was puzzled at the look, its bold intensity, and

the sudden wistfulness which clouded it all at once.

She dropped her gaze before the placid wonderment of his face, and

struck some random notes. Glancing at Sandro, the painter saw him

watching her with eyes that seemed to burn. All for an instant only;

then Sandro took the sketch and commented on it pleasantly, praising

the clever drawing of his face in this new character.

“I did not know I had such inspirations in me,” said he, “but

certainly I like your rendering, and it is a sweet idea of the angel at the

entrance of the grotto singing consolation to those who come seeking

for their Master. Will you not sing something to us, Ma Donna?”

And Diana sang, sweetly and skilfully, a song of the villages which

lie up beyond Samminiato, and when she had ended, there fell a silence,

during which Sandro poured out wine for his two friends.

“Why do you not make Madonna Diana your angel, instead of me?”

he asked as the red fluid bubbled forth; it was in the shadowed end of

the room that he now stood, and neither Diana nor Bonaventura saw

that something else dropped from his hand into one of the long glasses.

There was something too of sarcasm in his tone, but the painter looked

up from his work to which he had returned, took the glass given him

and said simply,

“I will tell you, my friend. It is one of my strange ideas. Madonna

Diana is as beautiful as an angel, it is true, but she has not explored the

perilous passages of this world as you have. I wish my angel to be one

who has been in many terrible places during his fleshly life, and has been

scarred by the talons of the Evil One. His was no easy victory over

malign things, and there have been times when he has been defeated,

but now that he has attained to an honoured part in the guard of our

Lord, he is the fittest to watch in that dreary place of tombs the body of

One who has also fought and conquered. Have I said enough?”

Sandro’s face suddenly quivered all over; he raised his hand. But

the painter drank his glass to the bottom, paused a moment in thought,

then placed it by. Meditatively he resumed his work, and for a long

time nothing broke the silence but the faint tinkle of the silver cords.

At last Sandro arose and bowed. “I must depart,” he said, and so

was gone.

Then Diana laid the instrument aside and sat with folded hands for a

little space, very still. The painter looked up from his work with a sigh,

thinking of something. “Alas! I am sorry for him, for the good he

contains,” he began to murmur, when his glance fell upon the motionless

beautiful figure, watching him with eyes of smouldering flame.

Directly their looks met, the flame burst into blaze; it was the first

time for weeks that they had been alone together, and she was a bold,

24

wilful woman. She stood up, smiled at him, then suddenly tossed back

her hair, so that a red-goldenness glimmered around, and cried, half

laughing, half sobbing …. “Beautiful as an angel—as an angel!

Oh, my cousin! Why have you not said it before ? Yet I love you

better for it too!”

The young painter as suddenly understood, and a gentle trouble filled

his face. But he stepped to her and took her hand. It must not go

further, for the sake of her parents as well as herself. Besides, all would

end before very long, now.

“Madonna,” he said soothingly, yet with a coldness which chilled her

horribly, “do not, do not be angry with me. You are indeed the most

wonderfully beautiful of women, and you are offering me the greatest of

honours, but I am only half a human being and I cannot love you as a

strong man should. You are to me the sweetest and kindliest of

maidens, but that is all I can feel. When half of a man belongs to the

other world, so that at times he knows how little more remains to him

of this, what can he give to such a queen as you?”

“You are cold and cruel!” she said, weeping, and dragged her hand

away.

“Not cold or cruel,” he replied, “but dying fast, and desiring only to

add one more testimony to that Paradise I hope the Great Master of all

things will allow me to enter.”

She gasped and stared at him, saying “What?”

“I knew I should not live out this year, in any case,” he replied, “and I

was at times sorely afraid that my suffering might overturn my reason

before departure. But as soon as I drank the wine just now I knew

that my life had come to a few days’ limit. My heart grieves heavily

that any friend should have found a cause of offence in a few light words,

yet for myself I do not grieve, for I shall have a speedy release from this

uncertain and often-troubled body. And it is best so for us, Diana.

Your parents could not have cared for a poor suitor like myself, even

had I been less of a shadow and more of a man. Farewell, dear cousin,

farewell, and let me paint my last picture in peace.”

She fell on her knees before him and would have flung her arms round

him, but he knelt also, and raised both her hands and his to a crucifix

on the wall.

After a little she rose, and silently went away. They met no more,

and she did not understand more of his words than that he would have

none of her, and that somehow she could not hate him for it.

But one day, as she was sitting with her father and mother and

many guests, some from north and some from south, but all men rich and

loving merriment, and the board was cleared and all were hushed to hear

her sing,—a bell began tolling heavily from the church hard by. And in

that heated air, with every window and door ajar to catch any passing

coolness, that doleful noise disturbed them very much, more and more,

so that the whole place seemed full of it. Very rarely was any one buried

in that churchyard, for its Campo Santo was small, and it was customary

25

for the citizens to take all dead outside the walls of the city. But there

were some who lay there, in the holy earth brought from Jerusalem, and

over their graves grew luxuriantly the strange Eastern flowers whose

seeds had come overseas in that soil, men of goodly life and well-stored

mind, who had served the cause of the Holy Church worthily, though

they did not wear the monk’s gown. Very few they were, but every one

a famous, honoured name.

So, the clangour of the constantly tolling bell seeming endless, and prevent-

ing the full enjoyment of music, Luigi Rossi stood up and begged his

guests’ pardon for the same, proposing that they should go round to the

other side of the house, into the garden, and there carry on their con-

viviality. To this they agreed, and soon were settled beneath the cypress

shadow, hearing the bell indeed, but faintly, so that the noise of talk or

the sound of song overpowered it altogether; many things they sang,

now one, now another, and many hearts beat hard and quickly as Diana’s

rich voice caressed their ears in that hot shadow.

Indeed, to look at her, gleaming ruddy-golden against the dusky

green foliage, as she gazed into every heart by turns with those eyes of

hers, so languorous yet so expressive of veiled delight in that admiration

which all must give her,—she was indeed a very enchantress, like that

Queen Armida of whom the poet Tasso sings. Or rather, as she stood

with silken folds spanning her shapely breast like the bands of a corselet,

and her bare arms so strong and firm with all their beauty, singing in

tones full and deep, never shrill, flinging the notes across the flowers and

upturned faces till they echoed distantly and wandered among the laced

branches like mysterious birds,—she seemed like the most enthralling of

that excellent (albeit mad) poet’s creations, the warrior maiden Clorinda.

So that Count Sandro could have bent his head and burst his heart with

the sweet agony which shook him,—nor was he the only one that day

who was so moved.

All this while the bell tolled, but no one heeded it any longer.

Then as evening came on the gathering dissolved, some going home-

wards to prepare for a night-festa, some otherways, until the afternoon’s

merrymaking was finished, and Diana went to her chamber. There

came to her a servant with a sealed letter, and placed a picture before

her, saying that it had been given to him for her by the servant of

Messer Bonaventura the painter, who had died a day ago by a return of

his former illness.

At that she felt as if some unseen hand had dealt her a fierce blow,

and turned as white as the wall hard by. When the man was gone she

lay for a long time on her bed and wept, not for Bonaventura, but for

herself, loving a youth who had thought no more lovingly of her than of

a comrade or a favourite dog or some other thing which is a pleasant part

of one’s daily life. Nor could she now be angry, because the man

was dead and had shown that his words were no concealment of slight

to her beauty, but stern truth. Thus after awhile she recovered, and

the passion passed like mist away; and she read his letter with a certain

26

melancholy, yet also with a certain relief of heart that it said nothing

which might cause others to ask questions.

“I, Bonaventura, being conscious that my end is very near, request

the noble lady Diana Rossi to accept the last picture I have wrought, as

a remembrance of the very many pleasant gatherings in my studio.

But I request that the noble lady (hoping that she wall yet remember me

sometimes in her prayers) will not speak of my death to the others who

assembled on those occasions. For above all things do I desire that the

recollection of me should be joyous and not sad.”

That evening her parents noted her to be less gay than usual, and

before they could ask her the cause she showed to them the picture and

letter, at which they also grieved a little, for they considered him a

worthy man. When also they heard that it was for him the bell of

S. Paolo had rung that day to their disturbance, they wondered that a

man now so famous in the city should have died so suddenly without

any one knowing it sooner,—and it gave them much to talk of until more

company came in for the evening, and with the business of entertain¬

ment the death of Bonaventura was forgotten.

The next day Diana went to the Campo Santo of S. Paolo, and saw

the painter’s grave. It was by his own wish that he was buried in that

ground, and his fame was such as fitted him for the place. Yet even as

Diana looked at the piece of turned-up earth she felt the remembrance of

Bonaventura to be less in her than it had been, only felt too that she

would never again meet such a man who could, without any effort on his

part, move her so much, and then while repelling her yet cause no hatred.

Indeed, the more she thought on it the less could she tell why she had

been so drawn forth, so presently departed to think of other things, and

henceforward to remember him only as a picture she liked but could not

understand. So little of a man of this earth had the painter been, and

so soon do those of Southern blood forget their grief.

That same day Sandro also came thither, with regret in his heart

for the man his passion had driven him to send out of this life. It is

not every one who would come thus to see his victim’s grave, but though

Sandro knew quite well that, could he have the last month over again,

he would act not a whit differently, yet he also felt sorry that the pleasant

little gatherings were at an end. In addition to this he had a letter from

the departed, as had Diana, and this is what it said:

“It has been a great grief to me, friend of mine, that I should by

my speech so deeply wound you as to cause you to do—so much. I

would have asked your pardon privately, had chance allowed. Yet

you have unwittingly done me a service, for I have often of late been

troubled by the fear that I must die in madness, so heavy were the

pains of my various maladies, and now the end is soon and speedy,

instead of a terrible tedious waiting for it.”

There was no signature, or name of any kind. Sandro was touched

by such considerateness, and brought a nosegay to place on the earth.

This done, he stood there meditating, no longer about the painter, but

27

about his chance of getting Diana from her parents. Possibly they

might be willing enough, but not she. He resolved to try in three days’

time, and then again by-and-by, and then again after that, until by per-

sistence he had worn down all opposition. The chief thing was to keep

other men away, which would not be hard, for most were afraid of him

and he knew it very well.

The little nosegay on the painter’s grave withered fast in the fierce

glare of the hot weather, now pouring day by day more heavily on the

city, and his memory in men’s hearts withered as fast. A few brief days

after his burial the only creature who had any thought of the thin

placid face was Diana, and that only when her eyes fell upon the picture

he had given her; strange as it may seem, directly he died her passion

for him melted away, and could find no sufficient mind’s image by which

to live. Remained only the spiritual portion of her former feeling,

which in such a woman was small indeed. She remembered him only

as a strange man, whom she must trust and respect entirely, were he

still alive. Such was the variability of her mind that she came near to

laughing at last, when the thought of his face, so puzzled and wistful

at her sudden love-making, flitted for an instant before her. How all the

other young men would have leaped at such a chance! Perhaps she

would not have said what she did, had she not a feeling that he was the

most innocent and temperate of mortals. Then, ceasing from her mirth

as she had ceased from her grief, in her usual sudden way, she hung the

“good cousin’s” picture again on the nail and scanned it while combing

out her great locks for the evening festa. And much she thought of the

gay youths with fur round their mantles, youths of hot, amorous temper.

All of them were rich, and one of rank. And then there was the elderly

Count of Castellocalvo who told such interesting tales. She wished for

the first time that he were rather younger and sighed at the passing

memory that the pleasant meetings had ceased in the studio three streets

away.

These were the thoughts suggested by the picture, a sketch rather than

a finished work, but having genius. There by a rock-sepulchre such as

most other painters represented it, sat an angel with the face of Sandro,

idealised with the expression which the poor painter had thought the

most significant of Sandro’s real nature, and more youthful, but very

resembling. The three Maries were all Diana in this way or that, but

only in the chief one was the whole likeness, with the full lines of figure

and red-gold hair, carried out to completeness.

Thus the dead hand of Bonaventura was causing what Sandro wished,

and made her think much about one whom she had formerly noticed

little more than one does any acquaintance often seen,—and so that

evening, when Sandro spoke to her, instead of returning merely the civil

reply which has no meaning, she conversed with him at length. True,

the subject was their mutual regret for Bonaventura, and the Count, when

he found that Diana appeared so strangely indifferent to the painter’s

memory, turned with a graceful sentence to other things. He was much

28

surprised at this, not believing it possible for her to so forget her cousin.

But their talking went on and he was in heaven during the duration of

it, seeing that at last she was interested in him as not with others. That

night he decided that it was time for him to speak to her parents, so as

to prevent other offers; also he thought that they probably would be

glad to make alliance with a rich noble. And so in truth it proved.

Everything went smoothly and in proper form. Diana seemed a

little surprised when informed that the Count of Castellocalvo wished to

make her his wife, but as the other suitors were no richer and of lesser

name, after a short while she agreed, and became his bride.

Sandro was a changed man from that time. He became generous and

genial, he became a byword for uxoriousness, and even did he begin to

grow fat. And so the winter passed, and with the spring the Countess

del Castellocalvo, who had hitherto allowed herself to be adored with

sufficient complaisance, began to be weary of the indulgent old man.

For now she saw him to be old indeed, and his continual fondness grew

tedious to her; most of all did she regret the gay gatherings which

Sandro strove to lessen as he began to feel the pangs of jealousy. She

took little care to soothe his irritation when the circle of gallants who

had hung round her the whole evening had gone homewards; and at

length Sandro, the man of many rough experiences, found himself

sometimes quailing before the coarse vigour of her tongue when her

anger was touched. For she was no timid or sensitive soul, nor ignorant

of the brutalities of speech, nor sparing in their use when she might

choose.

Worst of all, Sandro felt the weakness of old age now upon him,

and every one of these quarrels made him feel how much less he was

than once he had been, till at length he came to acquiesce sullenly in her

freedom of life, and cast down his eyes when men looked at him with

smiles of jesting pity as he passed them in the street. For it was now

well known that his wife counted off her lovers upon her fingers.

Now he thought again the old thought of his lonely castello up in

the hills, and meditated how he could get her there and hold her in the

way most pleasant to his nature, under lock and key. For days he

brooded over it, and as the hot weather began to come in once more, he

spoke to her in her pleasant moods of the delightful country she had

never seen, cool and airy, much visited by the rich nobles when Florence

had grown too hot for pleasure. Until, by often doing this, he heard her

say at last, “Why have we never yet been to Castellocalvo, my husband?

What is the use of a cool retreat up in those beautiful hills if you never

go there ? And how hot it is getting to be here! Cristo! but I feel

stifled!”

Then Sandro rejoiced, but was cunning in his reply.

“ Oh yes, it is a cool spot,” he said, “there is a fair woodland hard by, and

little brooks flowing down; the breeze comes straight in from the river

mouth and you can at times smell the salt. And the view is wide; you look

over the cliff-edge right into the valley far down and see the boats and

29

ships passing to Pisa. But I do not care to go, I want to stay here in

Florence.”

At this tantalization she stamped her foot, saying, “Why! every one

else is going into the hills. Do you want to be here all alone?”

“Yes, I like it, and we have had as much company as I desire. I

want to stay here and study, as I used to do.”

“Do you, my husband ? And pray what am I to do to pass the time?

I tell you I will not be kept here to roast on a gridiron! If you will stay,

I will not. I will go, and take my friends with me, and leave you here

alone. Do you like that?”

“Well,” said Sandro as if grumbling, “I suppose I must allow you

your will. When shall it be?”

“Now you are good!” said Diana very sweetly, “and I will give

you a kiss. We will go to-morrow. Do you not see how much better

it is for you to let me have my own way?”

“Truly I do,” said Sandro with a grim smile.

And indeed Diana could not complain of any hindrance on the part

of her old husband, that day. There was a great gathering that evening,

and Sandro was blithe as a wrinkled man could be, while his wife drank

merrily with her court of youths at the other end of the long table.

Several times that evening he met her in the groves of their garden,

dealing out a ready response of smiles, laughter, and the hot talk in

which her soul delighted, but there was no more sullenness on his brow,

none whatever. Many of his guests began to pity him somewhat, and

listened charitably to his garrulity.

In truth he was very content with himself, for he had gained what

he wished; she was coming up into the mountains with him, and once

there, with a few well-paid guards, he would have her safe, aud could do

as he pleased,—starve her into humility or experiment on her with love-

philtres.

A messenger had gone up thither as soon as he knew that she had

set her heart on it, and all was ready. Once up there, and Luigi Rossi

would have no power to interfere between his daughter and her husband.

So that last evening in Florence was a very gay one, and Diana received

as much adoration as she desired. The only annoyance, and a serious

one this, was the intense heat that oozed out of the sun-saturated stones

and earth without the faintest breath of breeze to lessen its strength.

There were rumours of plague in the low-lying villages, and most folk

told Diana that they envied her for her possession in the hills, for

mayhap the scourge might visit Florence,—God avert it!

With early dawn the cavalcade set forth through the slumbering

streets and the Roman gate was unbarred to let it pass. The captain of

the guard was a friend of the Countess, and as she and her train filed

through he saluted her with “a rividerla,” to which she responded

laughingly. She was very gay at that fresh hour, and the echo of her

voice came back as the party travelled seawards by the road skirting the

river, leaving the captain disconsolate and wondering where in this

30

empty season he could find another house for his entertainment and

another lady for his compliments.

Sandro rode by her and entered into her mood, which suited him

well, jesting and enduring meekly the wilfulness of her replies. She

made no secret of her dominance over him, turning him to ridicule

before the servants, and it all made the journey pleasant to her. Thus