THE DIAL

NO. 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

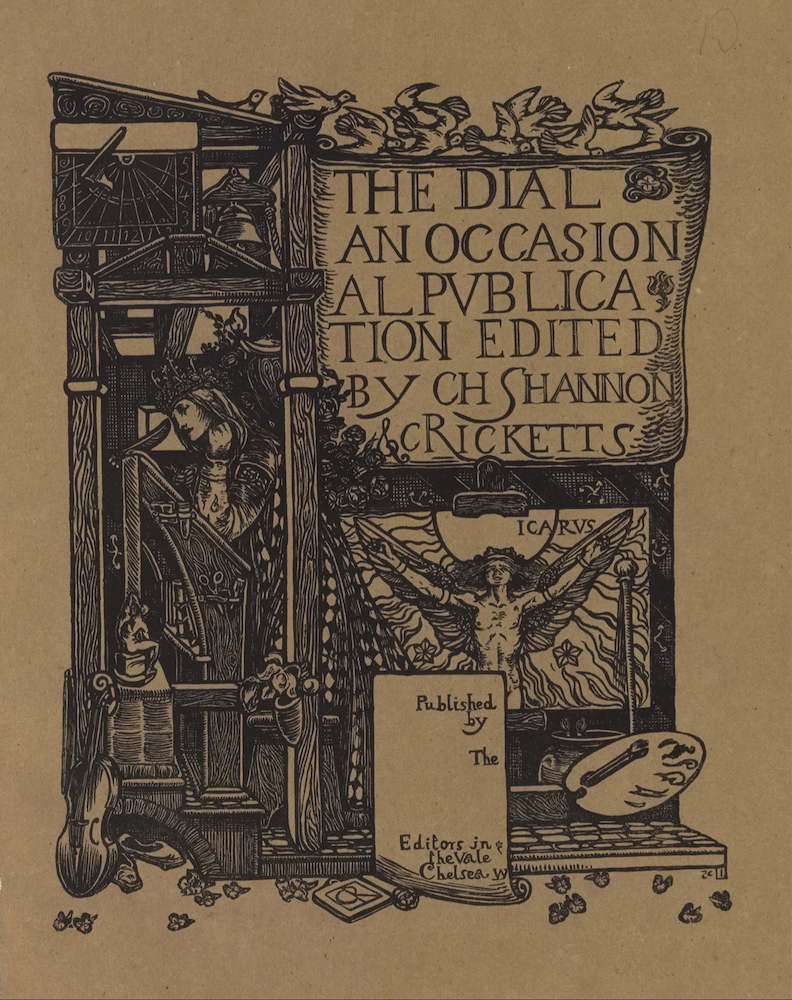

Front Cover designed and engraved by Charles Ricketts

❧ Full Page Illustrations

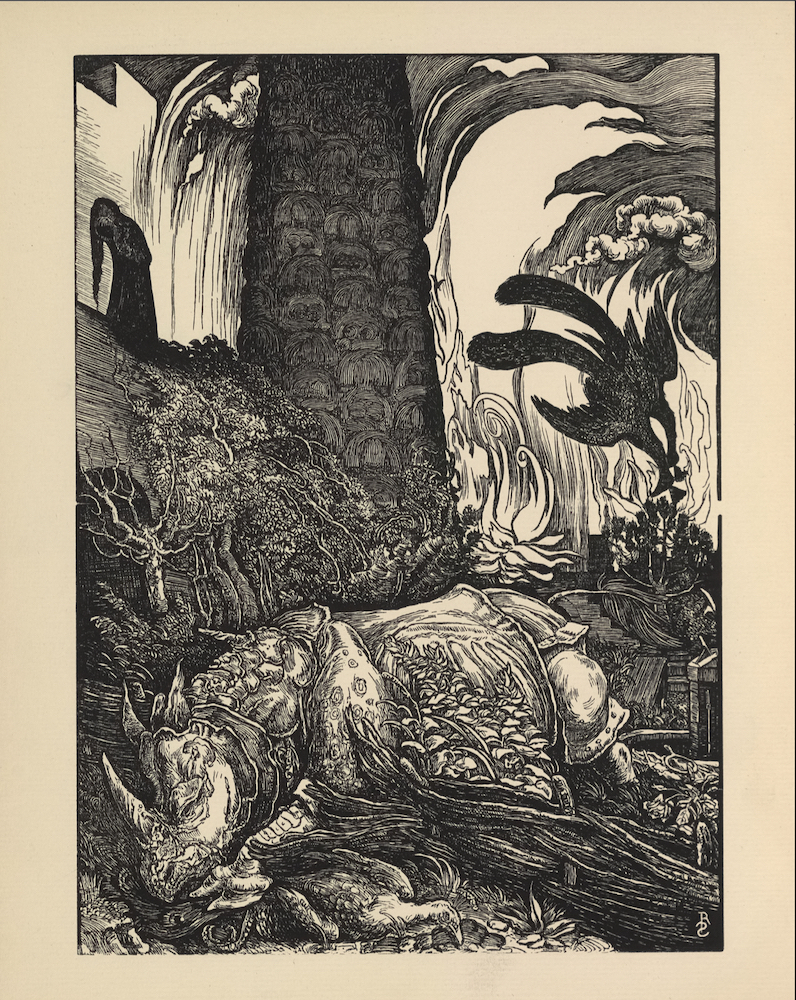

Frontispiece: THE PALACE BURNS AND BEHEMOTH designed and engraved on the wood by Reginald Savage

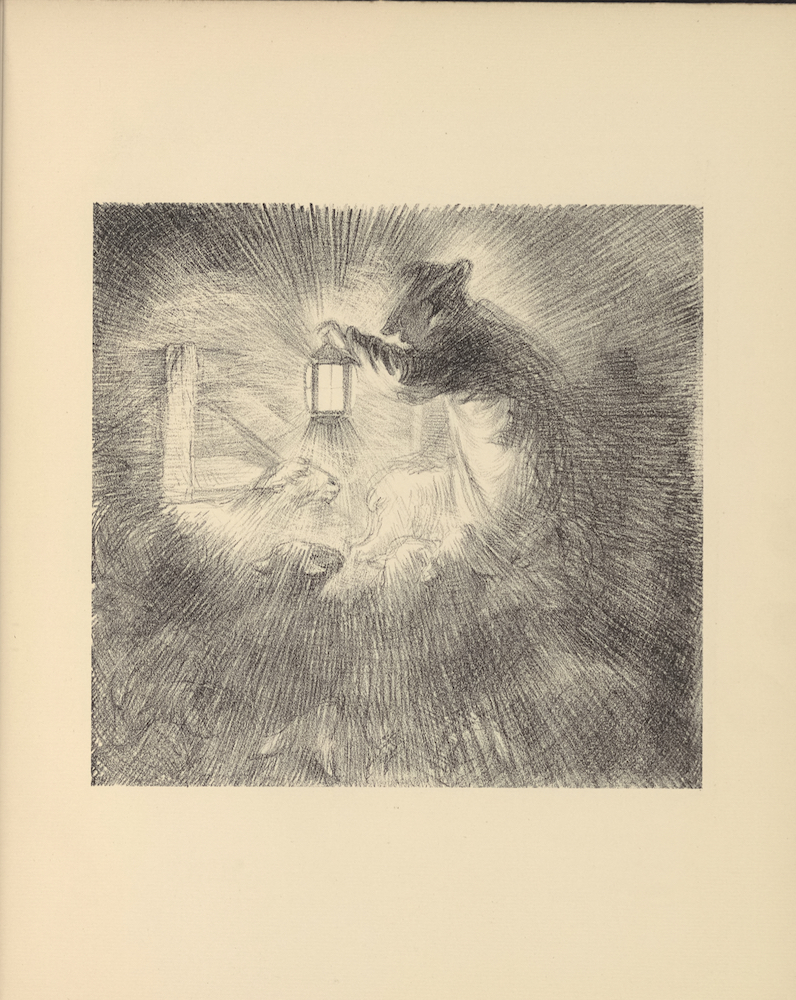

SHEPHERD IN A MIST drawn on the stone and bitten by Charles Haselwood Shannon . . . facing page 8

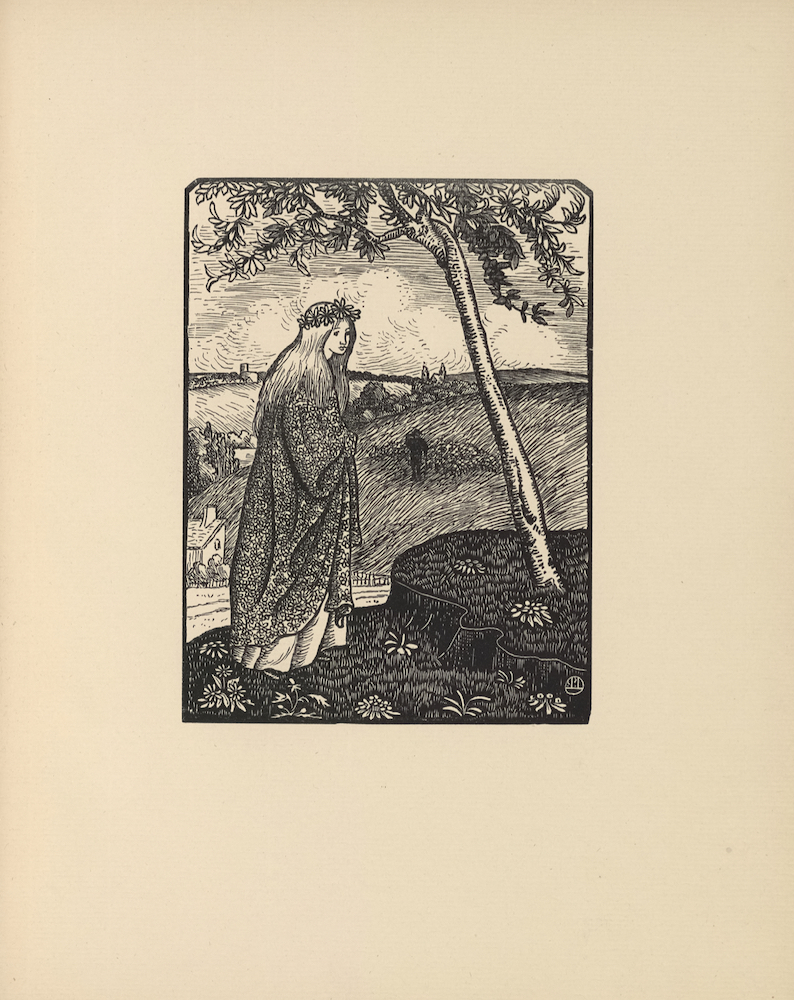

SISTER OF THE WOODS designed and engraved on the wood by Lucien Pissarro . . . facing page 14

REPEATED BEND an original lithograph by Charles H. Shannon . . . facing page 16

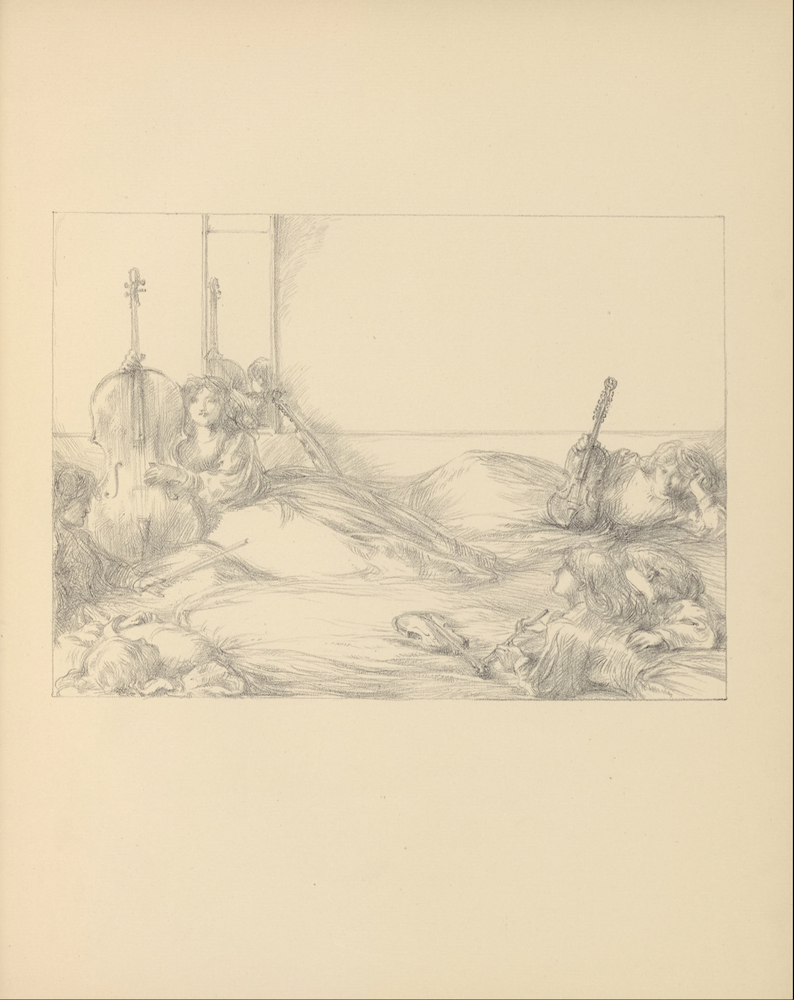

WITH VIOL AND FLUTE an original lithograph by Charles H. Shannon . . . facing page 17

MY HAIR IS FILLED WITH THE DROPS OF THE NIGHT designed and engraved on the wood by Charles Ricketts . . . facing page 22

Ballantyne Press Colophon by Charles Ricketts . . . page [36]

❧ Literary Contents

THE MARRED FACE by Charles Ricketts . . . 1

Pictorial Border and Initial by

Charles Ricketts . . . 1

TO THE FLOWERS, TO WEEP by Herbert P. Horne . . . 9

TO THE MEMORY OF ARTHUR RIMBAUD by T. Sturge Moore . . . 10

MAURICE DE GUÉRIN by Unsigned [Charles Ricketts] . . . 11

Pictorial Border and Initial by

Charles Ricketts . . . 11

ON A PICTURE BY PUVIS DE CHAVANNES by T. Sturge Moore . . . 11

BITTEN APPLES by T. Sturge Moore . . . 15

LOVE LIES BLEEDING by T. Sturge Moore . . . 16

THE LITTLE BROWN WOOD-MOUSE by T. Sturge Moore . . . 16

GUST-DISGUSTED GEESE by T. Sturge Moore . . . 16

LES CHERCHEUSES DE POUX (After Arthur Rimbaud) by T. Sturge Moore . . . 17

PYGMALION by T. Sturge Moore . . . 18

ON A DRAWING BY C. H. S. by T. Sturge Moore . . . 18

KING COMFORT by T.

Sturge Moore . . . 19

Pictorial Headpiece and

Initial by Charles Ricketts . . . 19

HEART’S DEMESNE by John Gray . . . 23

LES DEMOISELLES DE SAUVE by John Gray . . . 24

THE UNWRITTEN BOOK by Unsigned [Charles Ricketts] . . . 25

Pictorial Headpiece and

Initial by Charles Ricketts . . . 25

THREE FAIRY TALES by Unsigned [Charles Ricketts] .

. . 29

THE BRIDAL . . . 29

Pictorial Border by Charles

Ricketts . . . 29

ELLA THE SHE-BEAR . . .

30

SNOW IN SPRING . . .

32

TABLE OF CONTENTS . . . 34

THE MARRED FACE

MY MOUNTAINS ARE MY OWN

AND I WILL KEEP THEM

TO

MYSELF

W. BLAKE

I

BOTH city and suburbs re-

joiced. From roof to roof-

top swayed the

bell-like

weight of large lanterns that

mimicked the languorous

airs of lilies on the nod, yet

more duskily, like fruit again become

blossom,

against a faint pink sky still pale with the

lingering

trail of sunset; for Chang Tei had

laid low that haughty head of his upon

Mount

Torment, below the prison gates; and with the

dawn of even,

when a wan moon-crescent

beckoned to clustering stars, and mimic lights

from the bridges swam with them in the river,

a glow from his still

burning house put a dull

redness in the air, through which, now and

again, shot rapidly a light more acute, when a

charred wall crumbled in.

This was watched, long after curfew and into

mmm the night, for some

beggars sat at a town gate.

The sound of the patrol’s retreating footfalls

was echoed by overhanging

eaves, with this the tremulous expostulations of

some belated tippler hurried

away; the night-wind swept past, and the

stillness from circling hills sank

upon the city.

“Curse me!” quoth beggar Foo, “but Ling must have found a sweet-

heart.” At

this the pent hatred of the others clamoured against those limbs,

that

whole nose of his: “He a sweetheart forsooth!” They glanced hate-

fully at

each other’s maimed limbs; as the wind tosses dead tree-branches,

so their

arms became shaken, for with Ling was their common fund for food.

AH!

curse him; to hide thus from the patrol since sun-down was not

pleasant,

for the night became cold when the pre-morning wind, that shudders

in the

chimneys, adds its shriller coolness to the air.

Their hoarse clamour soon spluttered, and gradually ceased; dull gleams

only answered the fixed gleam of hungry eyes; one idea only troubled their

shrivelled lips: then with tacit consent the beggars bent towards the place

1

of Sudden Death, the muffled clank of plodding hand-rests beat a wooden

tune to their shadows cast upon the walls they passed.

Some dogs, upon the place of execution, snapped sullenly from right to

left, with fangs still clenched in shreds of flesh. Foo was bitten on the

hand; at his jarring cry the curs scampered away in a retreat of pattering paws.

About Mount Torment lay what remained, flesh made nameless, then

left there

by the torturer. One beggar shook from a bamboo stake a head

so placed not

to be stolen; a silent tussle began for this, in which blows fell

upon

unelastic shoulders that sounded like bumped wood. In the struggle,

this

prize had fallen to Foo; his wounded hand still maddened him, and this

gave energy to body bent in the effort to propel his little cart; the turning

of a few streets soon brought him into security, for the chase had grown

slack, a feeble shower of hurled stones ended it.

When he rested to take breath, his hunger had gone, which but now so

tormented him. Like an unequal runner, the taste of blood was in his

mouth, and he grasped at an oppression near his chest; so he placed the

head upon the ground, for it had grown heavy.

Something, as yet but half understood, flashed suddenly upon him, as

if an

oblique light, full of revelation, had been cast between his eyes and the

dead man’s eyes; vanishing, it left a partial recollection, or echo, in his

brain,

vibrant as a splash of white upon a ground of black, but, like it,

formless.

When, gradually, colour upon colour, the past, unrolled, swam upon the

filmy web, many things came back unbidden, as if, in sleep, he walked some

ominous strand girt with the refluent sweep of persistent recollection,

repeating—

“Do you remember, do you remember?” the dead man’s eyes added,

“You left by

the wrong gate, I lost you in the garden; I, Chang Tei, have

hated her,

ever since”—“ever since,” whispered the little memories,

“Ever since!”

Now, Foo understood why the night-watch had seized him beyond the

gate—as a

robber? or conspirator? he had never known; things had been

wrenched from

him, groaned in excess of anguish, when blinded by torture;

things whose

purport he had not then understood.

Though no kinsman dared succour him, he had escaped; ten years had

passed

since the paying of her kisses with his blood.

For hours the silent dialogue continued between the dead man and the

maimed.

Dawn tinged a summer pavilion near the royal orchards, when the

beggar

again reached the terrible Present, with its livid light that streaked

the

opposite walls, as with the stain of tears.

A lamp-ray shot from a lattice, for a moment opened; the sound of

trailed

viol strings floated past with the projected glimmer.

Then, he remembered the time and place; taking the head, he hurled it

through the unclosed window.

The marred face fell upon the queen’s lap; when she rose with suddenly

clenched eyelids, she felt its weight bite into her robe.

2

No one stirrred, their terror had not passed; from a word gasped by a

servant, her casual lover knew his mistress was the queen; he dared not

move whilst her eyes remained shut.

Her teeth clattered, and from the throat came forth a shuddering sound,

as

of something unwound slowly.

The fatal head merely looked at her; between its eyes and hers, one

recollection had grown, at first impalpably, but gradually, with such oppres-

sion that she opened them wide and closed her hands convulsed.

“Water! give me wine!”

A great silence fell. She became aware that her lips moved inaudibly.

A sense of void, that yet seemed conscious with a threat and terribly

near,

hung upon her. Had the world slipped away, out of time’s control?

and the

idea of calling for assistance seemed so absurd.

Of its own accord the head rolled over. Once more she gurgled from

the

throat, with short, hurt moans, and leant over the dead face, as if dragged

there perforce; in rapid succession came the remembered sensation of a

jostling palanquin, some women beckoning from a balcony, and a great

sense of fear that made her remember his name: but the angle of a villa

swam past in moonlight; with it the sensation of a nestling kiss; she

remembered the rest, and became conscious.

She feared the attendants heard these certain things, and motioned

unsteadily to them to go, to leave the room; and all this had taken but a

little while, for the wine still flowed from the gullet of a fallen jar, it

ceased

with a loud “Sob”; remembering her lover’s presence, she saw his

face

was frightful; with a terrified murmur she said “Go away”!—he turned

and left very suddenly.

Birds inaudible by day made the air acute with bleeding sounds, pulsed

from

red throats unassuaged. Above the lawns, the morning mists hung

loose a

silvery green which clung about and tinged the lower tree-trunks.

When the queen, with dull, relaxed eyelids, gazed through the window,

the

summer pavilions without seemed diminutive in the morning light, as

if

shrunken in the new sense of air, of space; the room was no longer doubly

stained by blended dawn and lamp haze, the lamp had gone out.

She felt stunned with all that face had said to her, from the time that a

hesitating blueness had been let in with the opening of a shutter, to the Now

that filled the walls with a diffused radiance that bleached the lattice;

those

lips had mumbled all their hatred, explaining, accusing and

repeating; then,

haggard images faced her on all sides, peopling many

mirrors that circled

or ceiled the love chamber,—might they not mirror the

marred face? This

gave her strength to rise, and fold it in her robe; she

would take it to the

river.—Several times she pushed the head from the

shore, for the river there

seemed without current; heedless of her

efforts, his lips smiled, as if they

sketched a kiss in the air and said

“why do you try? you cannot do this

thing.”

When Summer came, and the days brooded and grew still, beneath a sky

that

drooped, a glance of his would cling to her, his voice remembered would

3

seem Time’s central voice, heard only at intervals; sometimes it sobbed, like

the river beyond the gardens, whilst the fountains tall beat time without

and

dreamt they touched the eaves.—“You did not know that we should meet

so soon? but see!”—she even heard this after having locked the head in a

box; and sometimes a mirror remembered his face; she had this covered

up, never returning to that part of the palace. People said these mirrors

were covered because the queen was daily losing her beauty; there was some

truth in this; her dead lover haunted her with unforgiving eyes, only the

more implacable when she closed hers to the light; and, through this

terrible

obsession, the ghost of another feeling would sometimes steal

upon her and

make still, for a second only, the unrelenting fierceness

with which his eye-

balls looked at her; then she would cry, in pity of

herself.

Once his face had looked at her from the burnished gilding of an

oratory,

where she had gone to complain. Her pride was broken. If, at

times, her

old haughtiness returned, and, with it, deep gusts of wantonness,

she

found terror painted upon love’s face; some occasional lovers had even

to

be executed, for they had talked; those were such troubled times. Their

death seemed to her useless, foolish, but the laws of the country forbade

the slandering of the queen.

Slowly, she sank into a torpor, vague, but almost delightful; she dreamt

of

shadeful places, deep with boughs, long murmurous grasses,—places where

the large flowers seemed mellow sounds,—and that his glance had there

grown still. A belief in this would flow through her limbs with a soft,

velvety sensation.

Gradually, in these hallucinations, the dead man’s voice whispered

gently,

in tones that till then had been forgotten; and the newer sound

would

swell within her, like the long sun-streaks that glow and fade across

a

stretch of famished grass. Thus, something of the waning summer’s

pleasantness sank into her life, as it grew more and more unreal and blent

with the moods of the sleeping palace, giving moment to the yawn of a

curtain gently swayed by the breeze, the shimmer from the floors, their

clinging coolness poured beneath the cedar beams that cracked and stretched;

those things that give the sense of the hours as they fall from the hands

of

time like the beads from a chaplet; till once, in very sooth his voice

did

call from the sealed and spiced box in which she had placed this dead

face

to embalm.

Like one in a trance she rose to go to him.

But the head rolled over with a branding peal of laughter; exasperated,

she

struck it passionately, again and again, till her hands were wet with tears

—great tears streamed from his eyes; and her bowels yearned, as thick

drops gathered about her lashes, that she could have done this thing! she

kissed him, and they wept together.

Facing the queen was a picture she had often, if but vaguely, noted;

rich

with age, as with clinging incense haze, the painted figure was clothed

in

a violet robe that curved outwardly; it held a tongueless bell in one hand,

the other rose to close its laboured lips; the eyes were fixed

unfathomably

into space, they got their strangeness by the rigid

distinctness with which

4

the artist had pencilled them—those eyes seemed to have grown pallid in the

effort to forget.

Through her clustering tears she suddenly remembered the picture; the

resemblance of its lips to those of her lover broke upon her like a sudden

bell-sound heard in the centre of a wood. The painting had been called

“Silence”; some said it represented Fate: beneath the queen’s kisses

Chang

Tei very slowly closed his eyes.

Time passed, the summer days returned; legends about the queen took

clearer, if still fragmentary form; she was of alien blood, remotely of Tartar

origin. During the disturbances the Chang Tei rebellion had left in the

larger towns, those voices had grown louder that sing little, forbidden

songs, or give vent to exclamations in an amused crowd.

Some things were coarse and cruel, their infamy delightful to those who

could best understand it. When a few are gathered together, will not a song-

give, sometimes, to the singer a flattering sense of nationality?—some

origi-

nality of feeling steals unawares through a chorus not sung too

loud, but to

which people nod pleasantly as they go by the half-closed

door.

There were other things, however, not to be understood; the queen’s

poignant passions, this one supreme renunciation seemed only able to

assuage—how unaccountable this! She used to terrify her lovers, about this

there were many ingenious tales. Now, it was said she would wash this

marred face with her tears, wipe, devoutly, with her hair, the precious oint-

ments she poured upon its many wounds, kissing the spiced mouth; she

was as one who has listened to much prolonged music, or who half fears the

approach of a vision.

And men, with shrill voices, said a curse was upon her for her lewdness;

that an iron circle weighed upon her brow from nightrise to sunrise, but

that her lover had no cause to fear, being but a face; and people would

laugh exceedingly at this; also, was that Face not deeply marred?

Though trouble, ever increasing, raged in the provinces, the queen’s life

did not change; none but a few servants who had seen the head’s coming

had

access to her.

In long rooms, hung with violet veils, or dark bronze mirrors filled only

with a remote radiance, she nightly feasted with him, raising empty goblets

to her lips, breaking untasted bread sacramentally;—though a banquet was

laid nightly, she tasted but a little rice. When morning came she would

motion towards a window and say, “My Lord! the Dawn breaks.” Rising,

she would bear the head in her hands, devoutly, as a young priest does a

relic, through darkened corridors, where the purple shapes seemed absorbed

in the recreating of forms half remembered, of colours half effaced; and

she would murmur the while quaint foolish songs she had learnt in her

youth.

And behold! rebellion stood boldly at the gates of her capital with a

rejoicing populace issuing thence with appropriate presents, whilst in the

queen’s house all was still, as a place the south wind has swept over and left

withered.

5

News reached the palace; the servants issued from lateral gates; they

looked sharply about them as if to see if it rained, dropping ostentatiously

their long lances, or feathered brooms, if any one chanced to be near; but

as

yet no crowd circled the many royal buildings. Here and there stood a

few

men only, who blinked somewhat at the light, and watched, quietly, as

birds

watch a dying traveller. Some amongst them swung long arms, with

hooked

hands a little distance from their sides, scarcely knowing what to

do with

them.

When the sudden crowd came with the Deliverers beating their drums,

the

imperial peacocks and other birds flew, clamouring, into the air to perch

on unaccustomed roof projections and pinnacles. A deaf old servant came

out after this noise; crossing the main drawbridge, he held one hand to his

ear as if to listen. At this the crowd laughed merrily.

Room after room was crossed, in good order as yet, with a little laughter

only when there was no exit, and the same rooms had to be crossed again.

In the halls, the many paintings looked at the crowd; some represented

princes battling with waves or waterfalls; ladies among peonies; there were

pictures of gentle beasts, preciously wrought; portraits of beautiful Em-

presses,—one had been covered with a dish-clout, for her servants, wishing

to conceal the picture, had not dared destroy it, not knowing the town

would

open all its gates to the insurgents, so many things might have

happened.

The crowd by this time a little awed again laughed, then moved

on.

At last a cry of rage broke from them all; the queen could nowhere be

found. Some among the rebels said the carved figures on a roof represented

all the sins, that the topmost figure, tulip-shaped, was an image of sterility;

at any rate the splendours of this temple roof maddened them,—had it not

been built with what might have been in each man’s larder? And the prince,

of royal Chinese descent, who had headed the crowd, borne in a long

litter,

made a sign with his hands; his followers knew he wished nothing

to remain

of this palace, builded by an alien dynasty, and torches became

spontaneous

in the crowd.

The noise, which had hitherto filled the fantastic palace pavilions, ceased,

even without, and an oppressive lull swept heavily through the open doors,

and thence into the gardens.

On the lawns the birds had settled again, but once more they twisted

their

necks and bent their legs as if for flight; the Royal Tigers walked up

and

down their cages, or, lifting their front paws, they snuffed the air, as cats

do at a scented flower they do not think they like; white hares shot from

cover to cover and listened. No smoke was as yet visible—but a thin crack-

ling sound disturbed them.

When lithe flames bent from some windows, the alarm scarcely increased;

the

birds strutted about or took little foolish flights; out of the bamboo

stubble came the quaint squeak of the quail, the flutter of partridges.

Upon the walls, large painted spaces retained their surface colour unto

the

last, between the bursting and licking of the flames. Creeping plants

writhed from heated bricks. The clatter of tiles sliding away to where their

6

fall was no longer heard came, repeatedly, from a portion of the palace now

a widening flame.

A flight of peacocks wheeled round and round, as they fell, suffocated,

into the fire. The great sullen Behemoth then broke from his tank, in which

he loves to wallow in ooze and mire; first among the beasts he had

snuffed,

but had not moved, he had rolled little red eyes long before the

outbursting

of the flames. When, indeed, the heat grew terrible, he ran

with his snout

low down, hurling out of existence beasts that stood in his

path, to beat

against a part of the palace not yet on fire.

After the garden fountains had ceased, and their water had grown choked

and

turbid with fallen sparks, all the animals howled with a terrible voice

that had a blare as of brass, echoing to the very innermost room, where the

queen sat beneath the picture of Silence.

The palace burns, and Behemoth! but in her ears the roar was faint as

the

booming of a neighbouring sea, as the fall of land down some hill-slope.

Slowly, but very slowly, some smoke drifted between those walls that

were

covered with burnished bronze.

“Love!” she said, “I think the dawn has come! for there is a redness

in the

air, love! see, the morning mist is on the floor, filtered to this room.”

She laughed quietly, remembering it was still day, not even twilight, for no

servant had come, and without them she knew not, nor troubled to know,

how the spent hours waned.

Then it seemed to her the palace burned, as a little sound like a mouse

crept among the hangings that smouldered duskily, near the chink of a

bronze door; and the mist was filmy with smoke.

She knew that, owing to the gold upon them and the silver woven in

their

web, the curtains could scarcely burn; the burnished walls and finished

floors were covered with bronze plating; heat only, and suffocation, could

overtake her.

“My love,” she said, “the palace burns, let us go away.” Donning a fastidious robe, entirely radiant with wings outstretched upon its tissue, she nodded to him and sang vaguely, she also unwound her hair and painted her eyes, that he might be proud of her beauty; they would go away, the palace burned, the gods were so envious.

Door after door was crossed and left behind; the muffled rooms burnt

noiselessly, each sinking into A past as she walked

to meet the future. Her

dilated eyes caught glimpses of the whiteness of

her skin, the morsels of

beauty that remained to her; the black mirrors

had veiled the ageing of her

face.

Some of the insurgents saw her glide above a tall, smooth wall that led

to

a disused pavilion near the palace orchards, the culminant fire behind her

as a frame. The fixity of her gaze was centred on the dead man’s eyes.

Some one in the crowd hurled a javelin that stuck into a door before her.

But still she kissed her lover’s face, as if she inhaled the deep fragrance of a

flower. Then, as the pavilion had no outer door, as she could go no

further,

she reverentially kissed his marred face before them all.

Some say that owing to her great sinfulness she sang a wanton song.

7

PARSIFAL

IMITATED FROM THE FRENCH OF PAUL VERLAINE.

Conquered the flower maidens, and the wide embrace

Of their round proffered arms that tempt the virgin boy:

Conquered the trickling of their babbling tongues; the coy

Back glances; and the mobile breasts of supple grace.

Conquered the WOMAN BEAUTIFUL; the fatal charm

Of her hot breast; the music of her babbling tongue:

Conquered the gate of Hell; into the gate the young

Man passes, with the heavy trophy at his arm—

The holy javelin that pierced the Heart of God.

He heals the dying king; he sits upon the throne,

King; and high priest of that great gift the living Blood.

In robe of gold the youth adores the glorious Sign

Of the green goblet; worships the mysterious Wine.

And o, the chime of children’s voices in the dome!

8

TO THE FLOWERS, TO WEEP

Weep, roses, weep; and straightway shed

Your purest tears.

Weep, honeysuckles, white and red:

And with you, all those country dears;

Violets, and every bud of blue,

More blue than skies;

Pinks, cowslips, jasmines, lilies too,

Pansies and peonies.

For she, that is the Queen of flowers,

Though called the least,

Lies drooping beneath dreadful Hours,

Megaera has from Hell released.

Weep, till your lovely heads are bent:

Weep, you, that fill

The meadow-corners; and frequent

All the green margins of the rill.

Flood, flood your cups with crystal tears,

Until each leaf,

Each flower, through all the upland, wears

The dole and brilliance of your grief.

So that the Lark, who had from heaven withdrawn,

Re-sing to you

His song, mistaking noon for dawn,

And those your tears for dew.

Herbert P. Horne.

9

TO THE MEMORY OF ARTHER RIMBAUD

Thou sprung of warrior loins amid hill shade,

A wind-like variance maketh odd thy life,

With wild adventure rife.

Thy child’s-feet, racing with thy thoughts unstaid

By fagging flesh, then won thee wider scope,

To fly thy kite of hope,

Than childhood can command. “All breaths are laid;

Flints glare; how far all birds and springs appear.

Hush! draws the world’s end near.”

Thy wondrous virile youth all Europe made

An unfenced hunting-park; its every tongue

Speaking, thou yet wert young:

And sun-got children met thee down each glade

-Familiar god or godess-gave thy days

A memorable face.

Yet she by all who fashion forms obeyed,

To whom the waves give birth eternally,

Alone was wooed by thee.

Fate-filled thy friendships were; and it is said,

Like Marlowe, forebear of heroic verse,

Thou wert where women curse,

And in a broil his price had all but paid.

Once manhood reached, world-wide became thy range

In search of new and strange.

The rumours of thy progress hardly fade

On those shores named by waves no vessels ride;

And sun-scorched sand-seas wide,

Are haunted by suspicion thou hast strayed

O’er them. For thou rov’dst like thy losel boat,

Which tenantless did float

Past monumental dreams on shores displayed

(Down world-long rivers) till dissolved by these

And drunk up by deep seas;

It, like thee, o’er their aspects sovereign swayed.

T. STURGE MOORE

10

MAURICE DE GUÉRIN

CERTAIN mansions in Art’s home, without being wealthy,

splendid,

magisterial orofgod-gauged proportions,though

not always without, have a

quality of apartness strangely

attractive. When the afternoon mist gnaws

the hill-

hollow leech-like, till it become cavitous in the twilight,

and the head and shoulders of the mountain hang–like

of a crystal

palace—above receding halls of quietude,

vaguely visible through the

vapour-veil (transparent to the eye of Turner,

that man who scaled heaven

every week-day, and on Sundays went to

Wapping; to other eyes but

tantalizingly suggestive of discovery); there,

or, as Swinburne sings,

“Here, where the world is quiet,”

by the hearth of a mind, when the evensong dies down, Memory is a mother,

Passion a soulless woman of perfect charm, and, quite separate from her,

Love like a sister or dear friend clothed and in her right mind: there too

Mystery moves a maiden, Awe is a child, and Fear impossible.

Such is the aspect of mind or mountain not unfitly to be termed holy—

but

for the narrow and squalid daily application of the word—which is found

from time to time the only, the chief or one of the decorations of a room

in our Lady’s House.

To me especially certain works, singly or collectively, of a few artists

seem to be the produce of such holy seclusion, not from the world, but in it:

the preface of Boccaccio’s Decameron, with its sweet all-fatherly

benignity;

Dante’s Vita Nuova, the conceited, imaginative masque of love

and attendant

sorrows.

To Chérie, the tragedy of love-starved maidenhood, De Goncourt has

imparted

something of the parental tenderness of the old Italian; while

Rossetti’s

House of Life has more than surpassed, at least in scope, the old

love-drama.

Other names might be added, other works particularized. I do not

attempt

that completeness of criticism, necessarily futile, which leaves nought

unsaid: striving merely to give form to my own impression on reading the

work of De Guérin; ascribing to him the quality I have attempted to single

out from among the rich dowries of the masters.

11

The clatter of centaur heels has not the harsh factual ring of realism,

yet

is perfectly whole in life-likeness; though separated by the immense

fog

of time’s breath, palpable in the cold embrace of space, from our

ears.

“The rumbling of my going is more beautiful than the plaints of woods,

than

the noise of water.”

When, cooled by night’s exhalation of day’s sweat, he in the mouth of

the

cavern hears the inarticulate sleep-speech of the earth mother,—

“Then the foreign life, that had penetrated me during the day, detached

itself drop by drop, returning to the peaceful bosom of Cybele; as, after the

shower, the remnants of the rain attached to the leafage have their fall

and

rejoin the runnels.”

‡ “At times, when watching in the caverns, I have believed that I was about

to overhear the dreams of the sleeping Cybele; and that the mother of

gods,

betrayed by sleep, was babbling secrets: but I have never recognized

aught

but sounds which dissolved in the breath of the night, or words

inarticulate

as the bubbling hum of rivers.”

When his mother returns with material memories of the Unknown fresh

on her

body,—

“My growing-up was almost entirely in the shades where I was born.

My abode

was buried at such a depth in the thickness of the mountains,

that I

should have been ignorant of the side of issue, if, turning astray some-

times in at this opening, the winds had not driven there freshets of air and

sudden troubles. Sometimes also my mother returned, surrounded with the

perfume of valleys, or dripping from waves she frequented. And, these

incomings she made without ever instructing me of valleys or rivers, but

followed by their emanations, disquieting my spirits, I roved to and fro

agitated in my shades. ‘What are they,” I said to myself, ‘these withouts,

to which my mother betakes herself, and in which reigns something of such

power that it calls her to it so frequently?’”

When, turning, he views his flanks’ labour,—

“Thus, while my agitated flanks possessed the inebriation of the course,

above them I relished its pride, and turning my head, I stayed myself

some

time to consider my smoking crupper.”

When arrested in full gallop by imminent approach to the Unseen,—

“In the midst of the most violent courses, it has happened to me

suddenly

to break off my gallop, as if an abyss yawned up to my feet, or a

god

stood upright before me.”

Pervading these passages is the home-feeling of such rooms as reveal

Art

housewifely. This sense within the sense is not perhaps the grandest

quality for the artist; yet is it not one of the rarest? and to it is here added

beauty of detailed—especially of landscape—description, as, in The

Bacchante,

of the wind-cradled birds.

“When they, obeying the shades, lower their flight towards the forests,

their feet stay themselves against branches, which, piercing into the sky, are

easily rocked by gusts which pass across the night.

For even into their sleep they revel in the seizure of the wind; and like

‡ Many, probably, may here stop, surprised to find

freshly handled, work already

once finished and signed by Matthew

Arnold. He, in remodelling each sentence,

seems not only to become a

distinct but a distant echo. “What is it,’ I cried, ‘this

outside world

whither my mother is borne, &c.,’” this is not literal, and tastes

ready

made to my palate; as does not the piquant personal use of the

word “dehors” as

exceptional in French as its literal transcript in

English.

12

their plumage to shiver and dispart at the least breaths that come upon

the

top of the woods.”

After a day which the warm wine of Bacchus has made drowsy,—

“The birds lifted themselves above the woods, searching the sky, if the

going of the winds is re-established; but, still drunken, their wings barely

furnished a rickety flight full of error.”

A marvel too this latter work; though not approaching The Centaur

in

realization, yet has it, and perhaps on this account, a more unbridled

sympathy with the moodiness of Nature melting Maenad mountain and

moving

sea into a common existence.

“Sometimes from the hesitation of her steps, seeking assurance, and from

the air of her head, constrained and laden, one had said she walked at the

bottom of the ocean.”

“When I stayed my feet on the highest of the hills, I shook like the statues

of the gods in the arms of priests who lift them up to the sacred

pedestals.”

This oneness with Nature was his as a little lad, when the wind went

through him, standing under, as through the branches bending over, and

drew from both an adequate expression.

“Oh! how beautiful they are, those noises of Nature, those noises abroad

in

the airs, which rise with the sun and follow him; follow the sun as a

grand concert follows a king.

Those noises of waters, of winds, of woods, of hills, of valleys; the

rollings of thunders and of globes in space; magnificent noises, with which

are mixed the finer voices of birds and of thousands of chanting beings.

At

each step, under each leaf, is a little violin.

Oh! how beautiful they are, those noises of Nature, those noises abroad

in

the airs.

How full of them are the days of summer! What resoundings, when the

plains

burst into life and joy like big grown-up girls; when from all sides

rise

laughter and songs; the cadence of flails through the air, with the

accompaniment of crickets …. and those harmonious and inexpressible

breaths that are without doubt the guardian angels of the fields; those

angels who have for hair the rays of the sun.

Oh! how beautiful they are, those noises of Nature, those noises abroad

in

the airs.”

Of the man, author of these few pages where one scents, plucked in

Mnemosyne’s hand, flowers which bloomed nigh two thousand years ago,

finding them just as sweet as to-day’s with this difference, the pungency of

immortality, we know all that is ever known of the dead, friends’

opinions,

letters, journal, and all, to the least facts of his life,

uninteresting, apparently

unimportant, except as fetters. Many, whom his

work attracts, by its

freedom from the cloying of modern circumstance so

pitifully visible even

in the best work, would turn in disgust from the

man, never freed entirely

from a repulsive Christianity, to which his

nature was antipathetic. His

journal and letters are, however, enlivened

by draughtsmanlike sketches

of landscape, though burdened by much

soul-questioning, doubting and

obduracy of dogmatic faith.

13

Among his most famous critics have been Georges Sand, Sainte-Beuve

and

Matthew Arnold. The first wrote him a worthy panegyric, by way of

introduction to fame: with the two latter, however much we may admire

their characters as men, the foolish notion of immaculate criticism blights

all freshness of individual sympathy, or nearly all, in their work; both

seem

chiefly engrossed with the capacity for wear presented by the cloak

of acci-

dent, which in this case proves too heavy for the spirit-fire and

ends by

smothering it.

‡ Matthew Arnold, when he leaves the man for the essential artist, com-

pares him to Keats; which comparison seems to me inept. De Guérin had

none

of the splendid virility and spontaneity of Keats; Keats had not De

Guérin’s exquisite taste and next to perfect finish. Keats is ardent, creative,

curious; De Guérin reflective, analytical, nice. They have in common deli-

cate susceptibility,—a small link to chain the frank revelry of the

Englishman

to the composed reserve of the Frenchman.

To my mind the work presenting the closest English equivalent to De

Guérin’s is the Marius of Pater, though wider in scope, more difficult of

execution, and less evidently perfect in realization; there is a staid manner-

liness in their treatment, and a ruminant delectation of after-thought, so

at

variance with Keats’s masterly relish of attainment, which to the manly

might of his impetuosity appeared always discovery.

He said, “If a sparrow come before my window, I take part in its exis-

tence and pick about the gravel.” How different the “Toutes choses mieux

ressenties que senties” of De Guérin; whose nature, if not ample like that

of Keats, is rare, refined, a thing set apart for the delight of separate

natures,

lulling them into the reflective mood of long interminable summer

afternoons,

the indolent mental season of mature comprehensive

possession!

‡ Had I read Mr. Swinburne’s essay on Matthew Arnald, I

had rejoiced to have quoted

pas-sages in my corroboration; and I only

regret none could have been found to

confirm a, to my mind, right

appriciation of De Guérin’s masterly prose.

14

ON A PICTURE BY PUVIS DE CHAVANNES.

A spacious land lies large in broad daylight;

A warm wind healthily goes to and fro,

As a dear woman here might come and go;

In courtesy the trees incline their height,

Rustling their robes as folk at a wedding might;

And full of flowers the grass, by scythes laid

low,

Scents the sunshine, while peeps the weak

willow

Into pride’s paradise in waters bright.

A patriarchal people dwell in peace

And plenty perfect without wealth’s increase;

Nursed in the lap of lowland hills, their

homes

Are gay with flowers; both morn and evening airs

Are guests within their doors; and for their prayers

Cows safely calve, bees build big honeycombs.

BITTEN APPLES.

Their couch the pliant strength of lusty grass,

Cool shade of leaves their canopy, “Alas,”

Sing many maidens, crouched upon their knees

Or lain full-length among the flowers for ease,

“Alas, how slow, how slow,

Time’s hobby-horse does go.”

Some hold their hands above their heads, to touch

And handle—Eve-forgetting—fruit, so much

Their cheeks’ colour yet cool unlike their cheeks.

Their taste-stung tongues still tell, how “Every week’s

A week of weeks; so slow

Time’s hobby-horse can go.”

To idle hearts the day is weariness,

And to lax limbs the land heart’s heaviness;

For all their hearts are healed: long time ago

Hunter Love satisfied hung up his bow.

Their song dies down as slow

As Time’s play-horse can go.

15

LOVE LIES BLEEDING.

SONG FROM A FAIRY TALE.Love lies bleeding,

Fevers feeding

On flesh which swords have stricken.

Should sweet blood clot and thicken?

How could they slay him so,

When were pleading

Such eyes as his, you know?

Such eyes, such woe!

THE LITTLE BROWN WOOD-MOUSE.

A little brown wood-mouse

His ample fur cloak doffed,

Then tied his comforter

Before he left the house;

’Twas lamb’s wool, bleached and soft.

To see his tail was there,

He turned his head;

Then off he sped,

To look if beech-nuts were

Silver or red.

GUST-DISGUSTED GEESE.

The sun makes dust on the highways;

The wind pokes fun at the geese;

With feathers blown all sideways,

In walking they find no ease.

Let them spread wings, in it rushes,

As though to bulge out a sail;

Away they’re blown, on the bushes

To wreck like yawls in a gale.

16

LES CHERCHEUSES DE POUX.

AFTER ARTHUR RIMBAULD.When, forehead full of torments hot and red,

The child invokes white crowds of hazy dreams,

Two sisters tall and sweet draw near his bed,

Whose fingers frail nails tip with silv’ry gleams.

The child before a window open wide,

Where blue air bathes a maze of flowers, they sit;

And in his heavy hair dew falls, while glide

Their fingers terrible with charm through it.

So hears he sing their breath which dread hush curbs;

How rich with rose and leafy sweets it is!

It sometimes a salival lisp disturbs

On th’ lip drawn back, or deep desires to kiss.

Through perfumed silences their lashes black

Beat slow; from soft electric fingers he,

In colourless grey indolence, hears crack

’Neath tyrant nails the death of each small flea.

Then wells in him the wine of idleness,

Delirious power, the harmonica’s soft sigh:

The child still feels to their long drawn caress

Ceaselessly heave and swoon a wish to cry.

17

PYGMALION.

To work at sunrise nor till sunset rest,

Week’s end spliced in week’s end: ’twas thus he

wrought;

Tools blunt—not patience tempered by hot

thought.

With eager bare arms leant across her breast

He chiselled chin or cheek, and, where they pressed,

His labour’s sweat made bright the marble

bust.

At length she stands amid the workshop dust

In proudest pose of loveliness undressed.

His work once stayed, he, weakened by long strife,

Falls like a swathe from summer-heat’s keen scythe:

So sees he, waking at the day’s decease,—

Not the sea-mothered mother of all life,

Then vanished—but alone, alive he sees

A naked woman quailing at the knees.

ON A DRAWING BY C.H.S.

Deep-noted thy bucolic peace,

Such as no rose-lured insect hum

Or witty water-splash can tease;

In staid divine delirium

Entranced till princely Palma come

T. STURGE MOORE.

18

KING COMFORT

GATHERED together on the lea-slopes, trees jostle

elbows in sheer

jolliness; wind makes cornfields heave

in waves, like the sunny locks

spread over a little girl’s

shoulders, who on the nursery floor lies

laughing over

her Nonsense Book; and blue skies grow jealous of the

rival beauty of many streams, which gladden that land

where stands, under

steep tile roofs, the red-brick, slit-windowed, tail-

towered castle of

King Comfort.

This fortress was never even shaken by fierce assault or battery’s bluff

bluster; first, because the mortar its walls were built with had been welded

with dragon’s blood; secondly, as no one ever made attack or fired cannon

against its walls.

On its blue bosom a moat bore water-lilies beneath the ladies’ bower;

and

not infrequently apple-parings, crayfish claws, and other refuse swam

on

its shadow-blackened surface under the scullery-grate.

“Creak, creak,” went the well-winder, while chain and pail rattled down

to

the depths; the groom, scratching his poll, stood and watched pigeons,

whose nerves, never wrung with headache, give not the least start at the

harsh cry of the iron; which stopped, he ejaculates “I’ll swill ditch slush

rather than believe but what the king lives,” then bends his back and

lengthens his arms as he labours at the now weighted handle. But when

the bucket arrived at the top, mopping himself, he groaned out “By all the

wool-spools my mother’s spun, bless her heart, I’m as sure as that crabs

are

less sweet than pippins that good old Comfort’s stone dead.”

Then, the stable-lad flung the kennel doors open, and bulldogs, beagles,

harriers, spaniels, retrievers, black, piebald, fox-coloured,

milk-splashed,

rush yelping, barking, and bounding into the court, while

the pigeons wheel

into the air; a great mastiff oversets the newly drawn

water.

What Gunter said after the second descent of the pail, cannot be

recorded;

for it was more fit to have issued forth from the gargoyles, which

yawned,

like griffins, devils, belial-men, and bishops, round the roof, while

swallows built nests between their rumps and the coping.

Prince Pleasaunce, straddling his legs as wide as the arch of a stone

19

bridge, stood in breeches of tan kid, which sprung, like sturdy oak saplings,

from green velvet shoes gashed with white puffs; his coat, lined with fox-

fur, hung open to the knees, within it a saffron doublet crossed by a maze

of straps shining with buckles, to which hung his hunting-horn, knives,

and

wallets; he held between his teeth the lithe end of a dog-lash, while

the short

handle, made from a hart’s foot, swung among a litter of

boar-hound pups;

they frisked, gambolled, and tumbled together in attempts

to seize it, while

their mother blinked at them from the sunlight that

streamed through the

hall-windows, over the head of his cousin Gascoigne.

Who, legs out-thrust, lounged on a settle, dressed scarcely less gaily than

the other (capped with grey blue satin, a black plume of cock’s feathers

a-top), now and again grabbing at motes which spun in the large rays above.

“Say, Pleassy, I don’t mind waging a sly couple of cousin Nell’s

kisses,

the old boy’s heart’s cold, that is to say, you’re king, lad.” Presently,

receiving no answer from his pup-engrossed cousin, he got up; strolled

out

over the drawbridge, then round by the moat, till he was under

the

bower-lattice; flopped down on the bank; and began to throw small

stones

in the moat, striking up at the same time a roundelay. In a few

moments a

display of wonderful caps flowered out from the windows, and

showerlike

little laughs, “Good morning, cousin,” “Holiday health to Sir

Gascoigne,”

“A merry matin,” “Fine day, Sir,” “Hope ye quit bed the

right side,” and

like pleasant phrases dropt in the grass all round.

“Is poor Leonine’s foot healed?”

“O, don’t bother about dogs! I can’t bear them, they always smell

fusty.”

“O, how can you! not when they’re kept sweet.”

“No, indeed, my sweet mistresses; there’s many a gallant, I assure you,

prefers his dogs to the ladies, though, in my opinion, with loss thereby of

right to the title.”

“Ah! they rank equally with you.”

“No! now give me a chance; I’d swop a whole pack against any of

your neat

selves.”

“Oh! oh! flattery.”

“ Does one of my witching queens know whether the king, haply, yet

lives ?

”

All the girl-flowers vanish instantly; presently one only returns with

“Hush, you must not shout so; but this moment there was light along the

gallery, and the king’s daughter walked.”

“Ah, you lazy lout, stealing the dripping! There you go, slobberin’ it

on

your face!—Body of me! if thou wasn’t such a wain-load, I’d ha’ caught

the

knave, and lugged his ear for’im,—them boys’s always got their lips to

sucking something they’d no right touch.—Bless my puckered thumbs!

what’s

a’ that? Lor! beg pardon, I’m sure, sir, but your black hat is that

tall,—well it just be nothing more nor less than a witch’s steeple.”

“Good cook, have no fears. I come from my prince, commissioned to

add a wee

pinch of spice, some little tit-bit, dainty morsel, or as the French

20

put it ‘bonne bouche,’ to the apple charlotte I hear you have prepared so skil-

fully for the daughter of our royal master.”

“O, sir, it’s no great matter to make a charlotte; I’ve done billions on

’em in my time.—Well! I wouldn’t have thought that white powder ’Id make

mickle difference; looks just like sugar.”

“Yes, my good woman, it indeed is a subtle sweetener, most calming to

the

constitution. Have you a boy, haply, who might precede me with it to the

king’s chamber? I would not let it out of my sight, for fear of accidents.”

“Aye, sir, I bet there be a plenty hanging round ready to filch some’at

when one’s back’sturned.—Here,Tom—Sid—one o’ you lubbers; make your-

self

a bit spruce off to the pump.—He’ll be back ’fore a flea jumps, your

worship.”

The upper hall, weakly illumined with tallow dips; a gallery across its

further end, to which leads a stairway on the left; on the right a huge hearth

with its piled unlit logs; stray gleams twinkle like stars from false

eyes, jetty

claws, or shiny teeth all round; a long table runs under the

gallery loaded

with viands; servants move to and fro.

While, at the near end of the hall, under windows against which rain

rattles, talk, almost lost in shadows, a group of courtiers.

“I say she’s a witch.”

“Nay, nay, for she’s my sister.”

“I beg your highness’s pardon, but I think you must admit there’s excuse.”

“Well, may be so.”

“I hope that your highness would not take it ill, should she die

suddenly?”

“No, my fondness could bear the strain.”

“Master Fustian is barely descended to the kitchen, so if you’d rather—”

“No, she is a traitor; for any who intercepts the authority of a sovereign

is such.”

“What I’m afraid of is, frankly, her tricks.”

“I fear failure.”

“Failure, pooh! barely possible, so far as I see.”

“But look, here comes Master Fustian with the dish.”

“There!”

“Bah! what a clumsy clown! he’s got stumbling at the first step.”

“Up they go.”

Along the gallery light shines, and the king’s daughter walks.

The boy stumbles and falls back on Master Fustian; they finish the descent

together. Master Fustian, spitting all over the floor,—

“Gracious me! I believe—Oh! have pity, pity, my God! I think I have

got some

of it on my lips, my tongue. Oh! I’m lost, as good as dead!

Poisoned!

Arsenic!”

Confusion.

In which enters from a side door the prince’s pretty wife and her maidens.

Her he had married and a bad temper; he rather would have had her

alone,

but could in no way help himself.

21

That night, getting her tantrums, she broke from its gold mount the

coral

branch which stood on the dressing-table for her rings to hang on;

caught

her foot in the new silver-embroidered bed-testers, tearing loose half

a

dozen yards; flounced about; stamped her feet so hard she hurt them;

then

cried, and said it was his fault; at last said she would not have him

in

bed with her, and with an “I hate you” bade him crawl under.

Which he, though brave enough on horseback, began to do.

When a draught blew open the half-latched door, and a light shone in;

outside there walked the king’s lonely daughter.

The prince scrambled out and slammed the door; nevertheless, seemingly,

the

tantrums had found time to escape, for his wife said no more about going

under the bed.

If on getting in he was pinched black and blue, as she had threatened, he

made no one wiser about it.

Gusts teased the jolly trees till, wrathful, they cursed; the sky, black and

rugged as an old tarred barge-bottom, took a rusty glow of resentment from

the torches; all the folk stood shivering round the Home of Comfort.

The prince advances towards a great pile of combustibles heaped against

the

walls, a torch in his hand.

Flames leap, roar, and flare up into the sky; but the spiteful wind drives

them over, not on the castle but on the crowd, scattering it on all sides.

They would, in another instant, have caught autumn-dried hedge and tree,

and have stretched devastating away over the country. But the king’s

daughter’s taper gleams out of the great hall-window where she walks; at

the same instant the flames gobble one another up, and die away like fire-

works.

Then a voice roared out from the interior, as from a giant’s huge

chest—

“Both hale and well and blithe and bland

I live when no one cares for me:

But he that would close grasp my hand

A dwindling death is sure to see.

But I’m King Comfort after all;

Sins I can pardon great and small,

And need none handy to my call

Save my dear daughter, Privacy.”

T. STURGE MOORE.

22

HEART’S DEMESNE

Listen, bright lady, thy deep pansie eyes

Made never answer when my eyes did pray,

Than with those quaintest looks of blank surprise,

But my love-longing has devised a way

To mock thy living image, from thy hair

To thy rose toes, and keep thee by alway.

My garden’s face is o! so maidly fair,

With limbs all tapering, and with hues all fresh;

Thine are the beauties all that flourish there.

Amaranth, fadeless, tells me of thy flesh;

Briar-rose knows thy cheek; the Pink thy pout;

Bunched kisses dangle from the Woodbine mesh.

I love to loll, when Daisy stars peep out,

To hear the music of my garden dell,

Hollyhock’s laughter, and the Sunflower’s shout,

And many whisper things I dare not tell.

23

LES DEMOISELLES DE SAUVE

Beautiful ladies through the orchard pass;

Bend under crutched-up branches, forked and low,

Trailing their samet palls o’er dew-drenched grass.

Pale blossoms, looking on proud Jacqueline,

Blush to the colour of her finger tips,

And rosy knuckles, laced with yellow lace.

High-crested Berthe discerns, with slant, clinched eyes,

Amid the leaves, pink faces of the skies:

She locks her plaintive hands Sainte-Margot-wise.

Ysabeau follows last with languorous pace;

Presses, voluptuous, to her bursting lips,

With backward stoop, a bunch of eglantine.

Courtly ladies through the orchard pass;

Bow low, as in lords’ halls, and springtime grass

Tangles a snare to catch the tapering toe.

24

THE UNWRITTEN BOOK

THE accusation was brought against our first Dial of

mere art eclecticism;

one thing, keenly attractive to us,

might explain this reprehensible

selectiveness, a little

thing we think common to all good art. Inseparable

from the garment of individuality, the word Document

perfectly explains this.

Record of some remembered delight, record perhaps of a mere moment in

transfigured life, producing and controlling it, the word Document represents

some exquisite detail in a masterpiece,

convincing to the spectator as a thing

known, yet not of necessity the

symbol of borrowed story—possibly, there,

the mere symbol of time. A thing

easily imagined away from a picture, but

authoritative there, as a

gesture, or poetical recollection, the lattice-light cast

upon the wall in

Rossetti’s “Proserpine,” the azalea near the scattered hair

in Whistler’s

“White Harmony, number three,” might be chosen to prove

that Document is

not necessarily the mere machinery giving vraisemblance

to positive

subject, for these pictures are almost without it.

Rossetti, it is true, adds to his work a sonnet, and between this and the

picture some delicate interchime penetrates the sense with a conviction in

its symbol, adding meaning to the well-like light; to the fatality that seems

to brood about the shadows; to this face that listens to the ebb and flow

of

footsteps hastening. The fateful pomegranate might, however, be put

into

the hand of many an Italian portrait, the title Donna Innominata painted

25

on the frame would not destroy this picture’s memorableness—to-morrow the

name Proserpine might be given to Da Vinci’s Monna Lisa, and so, seem-

ingly, unseal its secret. In Whistler’s “White Harmony” the subject is

intentionally fugitive,—a chosen place where ladies live, with something of

the pale life of lilies listening to the music of their shapes. Yet in

this

secret air that drowses over the perfume of hair and flower, and

penetrating,

as it were, this mute harmony, some stray notes would convey

undertone-

symbol, preexistence, and chime about the picture faintly, like

evening music

echoed by a river.

These works have been chosen for their lack of story, in its common

acceptance; and so we come easily to the colour exclamation on some Chinese

enamel, dabbed there in vibrant crimson on a liquid purple, where no

subject

can exist at all; yet this thing, by its cunning spontaneity, will

give the emo-

tion that sudden movement adds to nature—the ripple of grass

in a summer

landscape for instance—and so become

Document —that monument of moods.

A viol left on a lowering

bough by some singer who has ceased, one mari-

gold drowned in a space of

water, would convey, within a picture and with-

out, this sense of

existence and preexistence, this sense of time.

In the work of the English Pre-Raphaelites, document has been chiselled

in

new-cleft gems; in Impressionism, it has been wrapped in strokes that

waved into air, or that palpitated into light; far be it then from us to claim

it treasure trove, for we think it inseparable from all art

excellence—capable

even of being spun to the veriest gossamer thread of

definition. More

common thirty years ago than at present, it may appear

unfamiliar, its

recentness has made it obsolete and strange.

We make no claim to originality, not feeling wiser than did Solomon who

doubtless wrote the Song of Songs; for all art is but the combination of

known quantities, the interplay of a few senses only; that some spirit seems

to transfuse these, is due to a cunning use of a sixth sense—the sense of

possible relation commonly called Soul, probably a second sense of touch

more subtle than the first—and this sense is more common to the craftsman

used to self-control than habit would allow.

We would therefore avoid all taint of announced reform for those patheti-

cally persistent in demanding it; dawn itself promises day only to some,

not to all; and Art has been, Art is, this is the pledge that it will be

again.

“Fresh with some colour, a cloud breaks upon the sky. Dawn grows,

wanes,

and stretches fibres of frail light; this is the signal to white hazy

moths to shimmer above the gummy vines; and stagnant water grows

steel-like and hard.

“Suddenly the cock crows; he is awake; long before, he has mistaken one

or

two accidents in the night for signals that he should announce the light, his

accuracy in utterance is merely sentimental.”

One word more of apology.

All past effort has seemed more conscious of aim, more direct, than it was

really; we imagine an effort towards renaissance, springing from a white

26

hand beckoning above the ashes of some forgotten city, and seen at some

time by one in whom the possible germ of a new art was placed. Again,

revelation has come to one reading a book, or to one who fancies he has seen

a grey torso beneath a cliff in some forgotten creek, and that it rocked

with

the water’s motion. We forget those previous years, wasted in barren

yearn-

ing, satisfied at last by something contemporary; imitation

following, too

often without knowledge of the new result attained.

To-day the announcement that you believe in Nature, or in Ideas, affords

claim to originality, and we would avoid this

announcement. By the word

Idea is meant, that formulated experience of the

many, their guarantee in

life against future failure. Strange, this

flattery of common thought, this

useless pandering to the crowd, incapable

in its appreciation to surpass the

annual shilling or two, for some

exhibition; for its characteristic is peevish

lassitude—the bankruptcy of

disinterest; the reviews have long since assured

it as to contemporary

lack of originality, separating this work from that

master, to attribute

it to his wife.

Indifference is only crested at times by little exasperated words, frost-

bitten fronds, crooked and meaningless: let admiration be one of the reasons

for the Dial to exist; admiration, so often fruitful of self-respect, nay

more,

it is “the essence of all art”—it is that which makes us wish in

childhood,

when power is not yet, and before experience has shut the

gates, for larger

flowers, something that would prevent soft, gentle

beasts from walking away,

the growth of berried twigs so out of reach, for

these are the first stray waifs

of all art feeling. Let the great artists

yet alive be witness that copybook

culture is the only reason for this

colourless currency in art and thought;

the rainbow of Art is still there

for Hope to look through, all pleasantness

has not been snatched from the

meadows and hills of Nature’s royalty, Art

has been, Art is, so the

present touches wings with the past.

“In the naif delight and fantastic objectiveness we call primitive art

feeling, space was found for the august and reticent personality of Piero

della Francesca; his work was sweet besides with occasional convolvulus ten-

dril, or nestling finch, gay in some trick of dress revealing personality,

some

shapely gem or crown of selected leaf. Giorgione painted the Greek

Theseus

—but as St. George naked in a brook, his work fulfilled. Since

then the

world would expect this development

with the budding of the garden peas,

that quality with the bursting of the pod. Experience

would, for conveni-

ence, separate the quality of form from its blossoming

into colour, little caring

to note its oneness—for in continuance from

environing space, to the central

surfaces, Form, Greek Form, as it is

called, is colour; colour is continued

line; without it, form is but some

personal conviction not visual at all, a

mental building into air, a

reasoned spanning of given space. Change, with

its contradiction, its

return to the past, appears again in Romantic Art, which,

nevertheless,

would control Art and Nature more than did the older styles;

dominate it

by individuality at high vibrant pitch—Nature strained into

symbolic

action, and in an atmosphere dyed by personal feeling.—Slowly

27

the old fantastic details of primitive art return, with these, the old

ornamental-

ness; lyrical movement recoils, becomes arrested, a tense

immobility ensues,

more ultimate than the great calm of the Antique, for

upon the Parthenon,

the great divine limbs leap and rebound, the draperies

cling close to flesh,

deep with the possibility of sweat.”

28

1 THE BRIDAL ❧ 2 ELLA THE SHE-BEAR

1 2

“HOW SEEMETH, HOW

SEEMETH “THIS IS NOT A SAVAGE

BEAR;

OUR ANNA

MITREVNA?”

IT IS ELKA, THE SHE-DRAGON.”

I

The ground-mist folds round the green earth in a

robe that is grey below,

but rose against the sky,

circling tree-tops as a sea circles islands; the

tree-

tops look wan. Rises the sun refreshed like a bride-

groom;

Mother Earth shivers through her veils, like

a bride ; the hills sigh

softly; hedge-flowers gleam

with a whiteness of morning stars, raising

tiny cups,

tiny crowns, all, save those that muse till it is day.

Now the high roads echo, echo loudly, with brisk

footfalls, gay talking,

and much laughter; each

maiden, in a green or new red kirtle, each

beautiful

damsel, is bright with ribands and neatly braided

hair.

Fine young fellows, on swift horses, ride up

from the cross-roads, with

greetings to the chatting

parents, brightest glances for the daughters,

and

they ask—“Where is this feast and beautiful be-

trothal of Anna

Mitrevna, the fair Anna Mitrevna,

to that powerful lord Ivan

Timofeievich?”—and all

give prompt answer, with hands raised forward to

sweep the horizon, “There! there is no bidding, all

are welcome;

and, oh! how merry will be this

merry wedding, and glad with many people;

so bide with us, as we are

going there.”

Fresh grass becomes trodden by hastening feet; the morning air tingles

to

the sound of gay guslas; the White House gleams in dew-dipped sun-

light;

about jump happy people, with heavy feet they jump in circles,

thumping

the ground, they dance with outstretched arms, singing—“Oh!

singing ha,

and ha, this merry wedding!”

“Come, come, bright

sun!

Come forth, good

people!

I have caught

Katenka, Katenka,

In my cornfield, nigh

the oak-grove,

Katenka, to be my

bride.”

Within the house, fair Anna Mitrevna sits among the tire-maidens. They

have

washed her white limbs, they have robed them in silk, and combed her

pale

thin hair with a silver comb, they have braided her hair till it hangs

below her girdle, the girdle is of silk well spun: in a diadem of gold, she sits

among the maidens; they laugh softly, but she does not laugh; her mother

has fallen on her neck and passionately kissed her, yet she could not

weep.

29

Anna Mitrevna is tall, slender as a Rousalka, her face is white, her eyes

are like hawk’s eyes, and she sits among the maidens.

Lord Ivan has come, with all his kinsmen, to woo, to seek the damsel;

he

asks of some of her near companions, “How seemeth, but how seemeth,

our

Anna Mitrevna?” and they chant and sing the bridal song, and answer

him,

that she is tall, and very slender, as a Rousalka, her hair is plaited to

her waist,—golden the hair, but light beneath the golden crown—and her

eyes are like a hawk’s.

Anna’s portly father donned a flowered robe and called loudly to his

daughter, whilst hired singers carol a merry song; yet the bridegroom waits.

Her mother has folded in stately folds the wedding veil; but the bride

does

not move.

Ivan’s father has taken her by the hand, her parents push gently at her

shoulders: they leave the room, the outer threshold, where waits the noble

wooer looking handsome. His mantle is of marten’s skin, his curly head

bonny with a scarlet cap, trimmed about with silver; thus he stands before

the hazel-coppice.

“You, you can not hold

me.

Yet you would kiss

me,

Boris, with your

lips, Boris!

Yours pout like a

grey mushroom,

Mine laugh like a

rose”

But, faltering, she grapples with his sturdy shoulders, cries in his face

“Thou red-eyed devil! cruel devil! ah! with those red eyes! red with

blood! also thy hands, that most treacherously slew Vladimir Kamarazin,

my

comely, my beloved lover!”

She tears the dagger from his belt, thrusts it in his breadth of breast,

holding on with both hands till his cruel heart is pierced, and with gaze

revulsed he falls to the damp earth for a bridal-bed, a dead bride by his side

upon the chilly ground, for his brothers have slain her.

The red sun sets behind the forest, now it is time for her soul to depart,

departing thus it addresses the sinful body and bitterly laments:

“Farewell! farewell! oh thou, my white body! poor body! thou hast

felt but

little joy, yet so much sorrow; thou goest, sinful body, to the cold

earth

to be devoured, to be dissolved.—There lies Vladimir Kamarazin.

I cannot dissolve, or lie in the still ground with Vladimir Kamazarin! for

I, the soul, must go to grief eternal, to a terrible, an eternal agony.”

2 ELLA THE SHE-BEAR.

“Since thou hast parted from thy

mother

Thou art a pale yellow.

Like a yellow orange,

And like a green bush.”

How snug was the bears’ house in winter: it was pleasant to listen to the

tinkle of the falling snow as it crept without, or cunningly clomb the pine-

trunks, to get back to Mother Sky; but the bears’ house was pleasanter in

30

summer, for about it a cool black pine-wood hummed and talked, broad

fragrant boughs drooped above the door; yet, in a damp cave, some few

rocks beyond the thinning of the trees, lived the She-Dragon Elka, the

White Enchantress who loved beautiful men, but doted most upon young

husbands. She was wicked and subtle, so many mothers had she made to

mourn, in the hamlets through the absence of lovers the gardens drooped,

and the graves blossomed. Bridal sheets, well spun with loud singing,

remained unbleached, for the brooks were full of tears. Prowling at night

in the shape of a She-Bear, she called the youthful shepherds “sweetheart,”

and by her cunning enchantments seemed to them a white woman; tall as

a green palm, softer than driven snow, white cream, or the sprinkling of

the

plum in blossom; when they had tasted of her treacherous lips, they

grew

very wan and yellow; as bushes do in autumn, they faded away. But to

those Elka did not love she seemed a grey She-Bear; and the bears hated

her, gladly they would have killed her, but how could they? They bitterly

cursed her when she was not near; mother-bears were troubled if the father

spake of her doings, and they would have slain her, but they dared

not.

One Saturday, the little Ella heard these things, as her mother combed

her

fur; the little She-Bear seemed as though she did not listen, yet her

honied eyes flashed, like sungleams caught in cruel icicles; she shut them

that she might the better remember, and thought “it would be very pleasant

to be an enchantress, seemingly like a soft woman, with a face like a blossom-

ing tree, soft as the drift of the blossoming plum, and to love beautiful

men.”

Came the young spring coyly as a betrothed—like a bride, with nosegays

upon

her green kirtle—and she whispered to the black pines who laughed

into

light buds: running among the trees she filled them with scents and

airs,

the banks with soft strawberries and furry mosses. When the tender

corn

skipped from the ground the very rills sang like birds. Ella’s desire

burst from bud into blossom, her coat shone like silk, with a lovesong in

each ear, she has left her mother; to each stranger she has said, “I am Elka

the White Dragon.”

Malemka, Sirma, Daria, sweet maidens all, washed winding-sheets in the

brook, Irma made poppy-cakes. Each sister was stripped to the waist, the

men being away, all save the dead man their brother; as they washed the

winding-cloths, with the flow of the waters they wept.

When they saw Ella they started and fled, so left the linen, to float down

the stream to the eddies, past the mill, to the eddies, to the bridge, where

the little children said, “Look! look! at the drowned white woman in the

stream.”

Young Ella wondered at her wisdom, her spells, for he was of great beauty,

the shepherd Stoyan, and stalwart as he lay on the couch, but a faded lily

his face—his eyes she could not see, for, as the bud hides the honey-drop,

his eyelids hid his glance; he slept.

Ella’s heart throbbed like a cuckoo’s song, she whispered softly, “’Tis I,

’tis I, my dear love! dear love, why dost thou hide thine eyes from me?

’tis I, yes I, thine Elka, thy loving enchantress.”

Now the men have left the pits, and some the kilns, or the hewing of

31

wood; they droop their heads like grass, their hands like falling leaves, for

their sisters and sisters-in-law have told them how the cruel Elka is with

poor Stoyan, Stoyan who has died of her many enchantments, “and we left

the winding-sheets to float down the river;”

“A bird flew away with a poppy-cake, and with it my heart fled away.”

Then all longed to kill the enchantress, but they dared not, they wished

to

slay her, but how could they? Yet a priest who was old, comforted them,

saying:

“Rather let us rejoice, that God, in his goodness, has delivered her into

our hands, for mark ye, good people, that it is day, and not night, for it is

noon; let each man take him a cudgel, and let Michel, the son of Nicholas,

toll the bell, that warns the people of the passing of spirits, perchance

this

spirit is but some stray Lamia not clothed by the night.”

Poor, poor foolish Ella half died with fear when came the pealing and

rolling of the bell; she shook and moaned, and would have entreated the

enchantress, but she dared not; gladly would she have fled, but how could

she? she crept crying to the door, where Basil, the stalwart woodman, struck

her with his axe, and all the brave young fellows beat her into a thousand

pieces.

3 SNOW IN SPRING.

“The streams gush from the heart of the

earth,

The earth as she sorrows.

If the sun knew half the sorrow of the

earth,

The earth in sorrow,

The sun would turn pale and hollow, like

the Moon.”

The Sister. The apple-bloom like snow tinged with

blood drifts to the

earth, my brother, my red sun, do not go away, this is

snow in spring.

The Brother. Do not weep for me, my sister, do not sob

like a labouring

brook, snow melts in water, your tears will not melt this

snow; the apple-

bloom in spring is ever flecked with blood, for the earth

and pine-roots crave

for blood in spring, till the Infidel be driven away;

and, oh my flower-sister!

the little brooks will wash my body of its sins,

each eye they will wash clean

as a separate crystal, that my eyes may

forget. The tree-roots will comb

my hair; the earth kiss and wrap each

limb of mine; for if I die, will not

the birds bury the hero, the willow

and elder sing me to sleep? and the

purple anemones, that are the eyes of

the field, will watch above my grave.

The Sister. Brother! brother! didst thou not hear the

sobbing of the

wood-pigeons to the pines? the pigeons that have stolen

their murmurs

from the brooks. The pine-trunks reel red, drunk with

blood:—Oh, my

brother! the oak-trees tell me that in spring the