TABLE OF CONTENTS

No. 6

Front Cover, by Pamela Colman Smith [i]

The Rim of the Sea, poem by Pamela Colman Smith 2

Illustration and decoration by Pamela Colman Smith 2

The Mermaid of Zennor, by L.C. Duncombe Jewell 3

A Deep Sea Yarn, by John Masefield 4-9

Pictorial Initial by Pamela Colman Smith 4

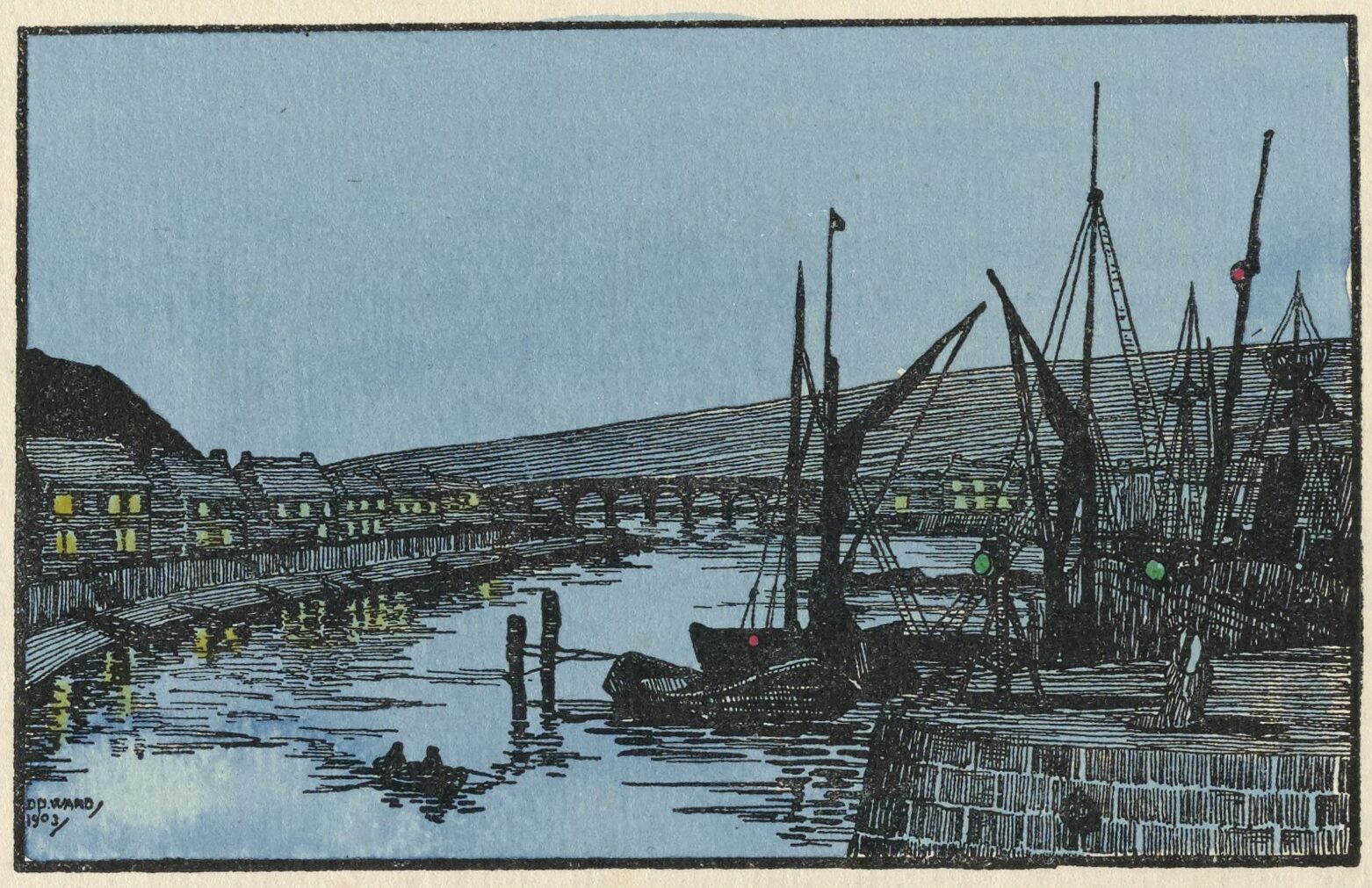

The Tidal River, poem by Dorothy Ward 10

Illustration by Dorothy Ward 10

Untitled. [from “Bright Star”], by John Keats 11

Illustration by W.T. Horton 11

Cobus on Death, translated by Christopher St. John from H. Heijermans’s The Good Hope 12

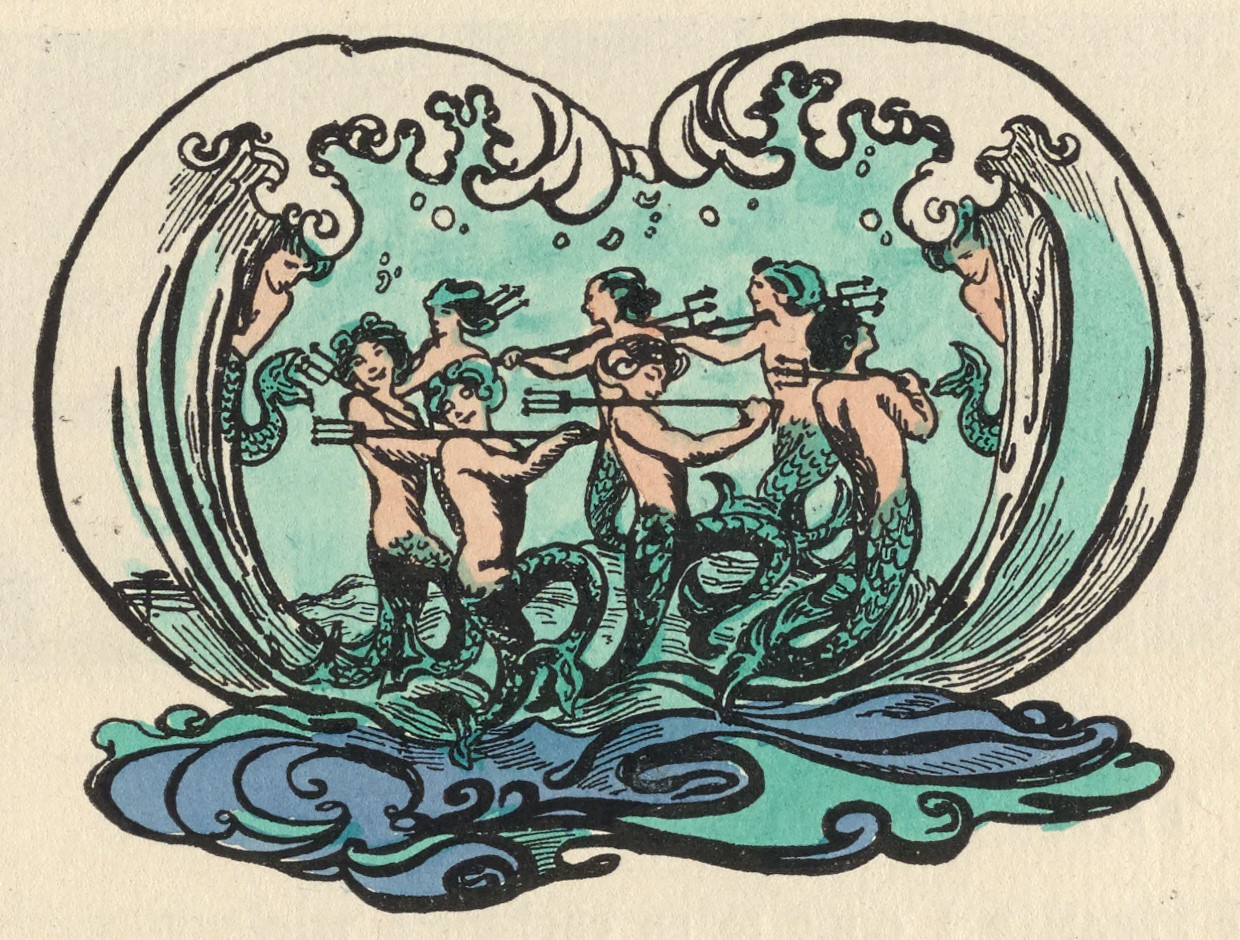

A Hymn in Praise of Neptune, poem by Thomas Campion 13

Illustration by Pamela Colman Smith 13

The Waters of the Moon, poem by Cecil French 14

Illustration by Cecil French 14

Advertisements 15-16

Advertisement for West Indian Folk Stories Told by Gelukiezanger, illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith 16

THE MERMAID OF ZENNOR.

“Fisher hast thou seen the mermaid combing her hair, yellow as gold, by the noontide

sun, at the edge of the water?”

emph rend=”indent”>“I have seen the fair mermaid: I have also heard her singing her songs plaintive

as the waves.”

— Breton Ballad.

Come! for the night and the wind are here,

And I am here:

Hard is your heart, but soft my arms,

And soft the sea,—

Come!

O human man, leave humanity

For these deeper depths:

Lean from the land, O human love,

And come to me,—

Come!

My bright hair burns, and the waves burn,

And my lips burn:

Strange is your heart, and strange the land,

And life is strange,—

Come!

Warm is the wind, and warmer the waves,

And my heart is warm:

Cold is your heart, my body cold,

And death is cold,—

Come!

L. C. Duncombe Jewell.

Written for the Psaltery,

10 Mis Merh,

1903.

A DEEP SEA YARN.

By John Masefield

P away north, in the old days, in Chester, there was a

man who somehow never throve. Nothing he put

his hand to ever prospered, and folk came to look

upon him as an unchancy fellow, one of the better-

dead and so forth.

Like enough he was just one of these weak

give-aways, but, as his state worsened, his friends

fell away, and he grew a sort of desperate, having

none to lean against, and moped more than was

good, and thought the black thoughts more than

was purely Christian.

So one night when he was alone in his room,

thinking of the rent due in two or three days and the money he couldn’t scrape

together, he says (being sore put to it) “I wish I could sell my soul to the Devil

like

that man the old books tell about.”

Now just as he spoke the clock struck “Twelve,” and, while it chimed, a queer

sort of sparkle began to burn and glimmer all about the room, and the air, all at

once,

began to smell very foul of brimstone.

“Will these terms suit you?” asked a voice.

He started and looked at the table and saw that someone had just placed there a

great parchment, red-written, the ink yet moist, which had wicked black figures at

the

head, at the foot and in the margins of it.

He picked it up, shuddering, reading it through by the bluey corpse-light still

glimmering in the room, and being so sore-driven he answered “yes,” though maybe

he was stricken too fear-sick to say “no,” to a cold quiet voice without visible body

(just a pale glimmer of wild fire to it instead thereof), so he answered “yes” and

looks

around for a pen.

“Take and sign,” says the voice again, “but first consider what it is you do. Do

nothing rashly. Consider.”

Which was said of course because an ill-deed done after taking thought is far

worse and fouler than one of these hot-blooded, done-in-a-clock-tick sins which are

merely the copper coin in the Black Account Book.

So this poor, tempted human error thinks awhile, then “yes” he says again,

“I’ll sign,” and with that he gropes for the pen.

The Green Sheaf

“Take this and sign,” says the voice, and at that he sees a ghostly finger (with a

talon to it like a hawk’s claw, and burning, as it were, in a thin reddish flame),

which

held a pen towards him.

“Blood from your left thumb and sign,” says the voice.

So he pricks his left thumb and signs. “Blue Snakes,” he says, “what sort of pen

is this I write with?”

The voice just chuckled, “Why ’tis a thorn o’ the tree where Judas hanged himself.”

Now when our poor lamb heard that you may well think of the cold sweat was

on him.

“Here,” he gasps, “give me back that scroll” (for somehow, you see, the scroll

vanished as soon as his name was on it) “I’ll cancel that mark o’ mine. Honour-

bright I was but fooling.”

“Here is your earnest money,” replied the voice, “nine and twenty silver pennies.

This day twenty years hence you will have your scroll. You will find your silver

alright I think. Good morning.”

Here that bluish marsh-light flickered and died out, leaving our poor dummel

creature dithering in the dark (’tis thought he swooned) and as he went off, something

ghostly, not of this world, whispered him a chilly sentence in his ear to hearten

him.

Later on ye’ll hear more of it.

Now early next morning, towards second cock-crow, our friend came to himself

and felt like one of the drowned. “What a dream I’ve had,” he says. Then he wakes

up and minds a bit clearer what sort of game he was at in the mid-watch, and when

he

sees those nine and twenty silver pennies and smelt a faint smell of brimstone I tell

you

he went as cold as a dead cod.

So he sits in his chair there, and thinks of things, remembering that he had sold

his soul to the Black Fiend for twenty years of heart’s-desire, and whatever fears

he

may have had in him as to what might chance at the end of those twenty years, like

enough he found a warm clove of comfort in the thought that, after all, twenty years

was a goodish stretch of time, and that throughout them he could eat, drink, merry-

make, roll in gold, dress in silk, and be care-free, heart at ease, and jib-sheet

to

windward.

So for nineteen years and nine months he lived in great state, having his

heart’s desire in all things; but, when his twenty years were nearly run through,

my

grief, there was no sicker man in all the world than that poor lamb. So he throws

up his house, his position, riches, everything, and away he goes to the port o’ Liverpool,

where he signs on as A.B., aboard a Black Ball packet, a tea clipper, bound to the

China Seas.

My heart, they were the ships, those Black Ball clippers—there are none

such in blue waters nowadays.)

The Green Sheaf

They made a fine passage out, and when our poor lad had but a three days more,

there they were in the Indian Ocean (lat. and long, just so-and-so) lying lazy, looking

for a slant o’ wind, in a belt o’ blue calm.

Now it was our lad’s wheel that forenoon, and it being dead calm, all he had

to do was to take his plug like a sailor, and just think of things; the ship of

course having no way on her.

So he stood there, hanging onto the spokes, groaning like a foul block, and

weeping the scuppers full. Just twenty minutes or so before eight bells were made,

up comes the old man for a turn on deck before he takes the sun.

He goes aft o’ course, takes a squint aloft, and sees our poor lad blubbering

like a martyrdom. “Hello, my man,” he says, “Why, what’s all this ? Ain’t you

well? You’d best lay aft for a dose o’ salts at four bells to-night.”

“No, cap’n,” comes his answer, “There’s no salts nor Gregory Powder’ll ever

cure my sickness.”

“Why, what’s all this?” says the old man. “You must be powerful rocky

if it’s as bad as all that. But come now, tell a fellow, your cheek is all sunk,

and you look as if you ain’t slept well. What is it ails you, anyway? Have

you anything on your mind?”

“Cap’n,” he answers very solemn, “I have. I’ve sold my soul to the Devil.”

“Blue snakes,” cries the old man, “ Why that’s bad. That’s powerful bad.

I never thought them sort o’ things ever happened outside a Penny Blood.”

“But, cap’n,” says our friend, “That’s not the worst of it, cap’n. At this

time three days hence the Devil will fetch me home.”

“Heart-alive,” groans the old man, “Here’s a nice hurrah’s nest to happen

aboard my ship,” (and he stumps up and down in a mighty flurry). “But come

now,” he goes on, “Did the Devil give you no chance—no saving-clause like?

Just think calm for a moment.”

“Yes, cap’n,” says our friend, “Just when I made the deal, there come a

cold whisper like, right in my ear. And,” he says, speaking very quiet, so as

not to let the mate hear, “if i can give the devil three jobs to do which

he cannot do, why then, cap’n,” he says, “ I’m saved, and that deed of mine is

reckoned ripped up and slung overboard.”

Well, at this the old man grins like a mess-kid, “Why,” he says, “You

just leave things to me, my son. I’ll fix the Devil for you. Aft there, one o’

you lads, and relieve the wheel. Now, sonny, you run forrard, and have a good

watch below. Be quite easy in your mind, I’ll foul his hawse for him. Buy

your soul, would he—the Black Dog ? Well, we’ll see.”

So away forrard goes our friend, and the old man takes the sun, and chuckles

in his chart room till the dog-watch.

The Green Sheaf

And so that day goes by, and the next, and the one after that, and the one

after that was the day.

Soon as eight bells was made in the morning watch the old man calls

all hands aft.

“Men,” he says, “I’ve got an all-hands job for you this forenoon. Bear a

hand cheerly and you’ll each get a tot of grog in the first dog this evening.”

“Mr. Mate,” he cries, “Get all hands onto the main-tops’l halliards and bowse

the sail stiff up and down.

“Hoist the main taws’l stiff up-and-down ? Ay, ay, sir,” sings out the mate.

So they pass along the halliards, and take the turns off, and old John

Chantyman pipes up.

“There’s a Black Ball Clipper cornin’ down the river,” and away that yard

goes to the mast-head till the bunt-robands jam in the sheave.

“Belay there,” says the mate, “Don’t lose any.” So they belay and one

o’ the boys coils down.

“Very well that,” says the old man. “Now get my dinghey off o’ the top

o’ the half-deck and let her drag alongside.”

So they do that, too, and any sort o’ notions they have o’ the old man’s

brains they just keep among themselves; that being the healthier way aboard

ship as may happen you’ll have found.

“Very well that,” says the old man. “Now forrard with you, to the

chain-locker, and rouse out every inch o’ chain you find there.”

So forrard they go, and the chain is lighted up and flaked along the deck all

clear for running.

“Now, Chips,” says the old man to the carpenter, “just bend a spare anchor,

an old sail full o’ ballast (and any holystone you may have) on to the business end

of that chain, and clear away them fo’c’s’le rails so as we’ll get a fair-lead, like,

when we lets go.”

“Ay, ay, sir,” says Chips, and he makes it so.

“Now,” says the old man, “ get them tubs of slush from the galley. Pass

that slush along there, doctor. Very well that. Now turn to, all hands, and slush

away every link in that chain a good inch thick in grease. Slather it on like

sailors, and don’t go leaving no holidays on the studs.”

So down goes all hands—mates and all—and a fine Bristol job they make of it.

\

I tell you, when they were done, that chain would have rove through a jewel

block, it was that slick.

“Very well that,” cries the old man. “Now get below all hands ! Chips, on

to the fo’c’s’le head with you and stand by! I’ll keep the deck, Mr. Mate! Very

well that.”

The Green Sheaf

So all hands tumble down below; Chips takes a fill o’ baccy to leeward of

the capstan, and the old man walks the weather poop looking for a sign of hell-fire.

It was still dead calm—water all oily blue—with shark’s fins astern cutting up

black and pointed like the fingers on them things called sun-dials.

Presently, towards six bells, he raises a black cloud far away to leeward,

and sees the glimmer o’ the lightning in it; only the flashes, somehow, weren’t

altogether canny. They were too red and came too quick.

“Now,” says he to himself, “stand by.”

Very soon that black cloud works up to wind’ard, right alongside, and there

comes a red flash, and a strong sulphurous smell, and then a loud peal of thunder

as the

Devil steps aboard.

“Mornin’, capt’n,” says he.

“Mornin’, Mr. Devil,” says the old man, “ and what in blazes will you be wantin’

aboard my ship?”

“Why, cap’n,” says the Devil, “I’ve come for the soul o’ one o’ your hands as per

signed agreement; and, as my time’s pretty full up in these wicked days, I hope you

won’t keep me waiting for him longer than need be.”

“Well, Mr. Devil,” says the old man, “the man you come for is down below,

sleeping, just at this moment. It’s a fair pity to call him up till it’s right time. So

\

supposin’ I set you them three tasks. How would that be? Have you any objections?

“Why no,” says the Devil, “fire away as soon as you like.”

“Mr. Devil,” says the old man, “ye see that main-tops’l yard?”

“Not being naturally blind,” says the Devil.

“Quite so,” says the old man. “Well, as I was going to say—suppose you lays

on that main-tops’l yard and takes in three reefs single-handed.”

“Ay, ay, sir,” the Devil says, and he runs up the ratlines, into the top, up the

topmast rigging and lays along the yard.

Well, when he finds the sail stiff up and down, he naturally hails the deck—

“Below there! On deck there! Lower away ya halliards!”

“Quite a pretty view up there, ain’t it?” shouts the old man.

“Lower away ya halliards,” the Devil yells.

“Not much,” sings out the old man. “Nary a lower.”

“Come up your sheets, then,” cries the Devil. “ This main-topsail’s stiff up-and-

down. How’m I to take in tfiree reefs when the sail’s stiff up-and-down?”

“Why,” says the old man, “you can’t do it. Come out o’ that! Down from aloft

you hoof-footed Port Mahon Sodger! That’s one to me.”

“Yes,” says the Devil, when he got on deck again, “ I don’t deny it, cap’n.

That’s one to you.”

“Now, Mr. Devil,” says the old man, going towards the rail, “suppose you was to

step into that little boat alongside there. Will you please?”

The Green Sheaf

“Ay, ay, sir,” he says, and he slides down the forward fall, gets into the stern

sheets, and sits down.

“Now, Mr. Devil,” says the skipper, taking a little salt spoon from his vest pocket,

“supposin’ you bail all the water on yon’ side the boat onto this side the boat, using this

spoon as your dipper.”

Well!—the Devil just looked at him.

“Say!” he says at length, “which o’ the New England States d’ye hail from anyway?”

“That don’t cut any ice as far as I see,” says the old man. “Not Jersey, anyway.

That’s two up, alright; ain’t it sonny?”

“Yes,” growls the Devil, as he climbs aboard. “That’s two up. Two to you and

one to play. Now, what’s your next contraption?”

“Mr. Devil,” says the old man, looking very innocent, “you see, I’ve ranged

my chain ready for letting go anchor. Now Chips is forrard there, and when I sing

out, he’ll let the anchor go, and, if I’m not greatly in error, it’ll go. Supposin’

you

stopper the chain with them big hands o’ yourn and keep it from running out clear.

Will you please?”

So the Devil takes off his coat and rubs his hands together, and gets away forrard

by the bitts, and stands by.

“All ready, cap’n,” he says.

“All ready. Chips?” asks the old man.

“All ready, sir,” replies Chips.

“Then, stand by— Let go the anchor,” and clink, clink, old Chips knocks out

the pin, and away goes the spare anchor, and the sail full of ballast, and a few

hundredweight of spare holystone into a five mile deep o’ God’s sea.

My heart the way the chain skipped.

Well—there was the Devil making a grab here and a grab there, and the slushy

chain just slipping through his claws, and at whiles a bight of chain would spring

clear

and rap him in the eye. You’d understand how if you seen a ranged cable running. I

tell you it’s good to stand from under at them sort of times.

So at last the cable was nearly clean gone, and the Devil runs to the last big link

(which was seized to the heel of the foremast), and he puts both his arms through

it,

and hangs on like grim death.

But, my heart, the chain gave such a Yank when it came-to, that the big link

carried away, and oh, roll and go, out it goes through the hawsehole, in a shower

of

bright sparks, carrying the Devil with it.

’Tisn’t any fault o’ that old man if Mrs. Devil ain’t a widow. You should aheard

the piteous screech he give as he took the water.

As for the old man he just looks over the bows watching the bubbles burst, but the

Devil never rose. Then he goes to the fo’c’s’le scuttle and bangs thereon with a handspike.

“Rouse out, there, the Port Watch,” he shouts, “ an’ get my dinghey inboard.”

THE TIDAL RIVER.

Under the bridge can you hear the water swirling?

Can you feel it drift the boat along, as we rest upon our oars?

Beyond the shadow of the piers, do you see the wavelets curling,

And the twinkling lights move backward, as we slip between the shores?

Against the harbour lamps, do you see the ships loom sable,

As we thread our way between them to the green light on the quay?

Can you hear their timbers creaking, as they strain upon the cable,

While the hurrying tide speeds past them on its mad race to the sea?

Beneath the farther bank where the water shows no motion,

Can you see the dim reflection from every silver star?

And from beyond the sandhills, in the darkness of the ocean,

Feel the throbbing of the waves as they break upon the bar?

Dorothy Ward.

COBUS ON DEATH.

(From The Good Hope. A Sea play by H. Heijermans.

Translated by Christopher St. John.)

Cobus. —It’s a good job for Daan that he’s unconscious. He’s frightened of death.

Clementine. —Why, so is everyone, Cobus.

Cobus. —Everyone? I’m not so sure. If my turn came to-morrow, I should

think to myself:——We must all come to it—all the water in the sea can’t keep it

away. God gives—God takes. You see how it is . . . now don’t laugh . . . God

takes us, and we take the fish. On the fifth day He created the beasts of the sea,

and

all the creeping things that abound in the waters . . . and he said “Be fruitful,”

and

blessed ’em, and the evening and the morning were the fifth day. And on the sixth

day

He made man . . . Well, you may notice He said very much the same to man. And

the evening and the morning were the sixth day. Why do you laugh ? It’s easy

enough to laugh, but I tell you it all comes clear when you’re out herring fishing.

Sometimes I was quite afraid to split and clean the fish . . . When you take a herring’s

head and run your knife into him till the yellow oozes out—I tell you the fish looks

at

you with such an expression—well, you feel ashamed! Yet you split two casks full in

an hour and cut off 1,400 heads. 1,400 heads! That means 2,800 eyes looking at you—

just looking—always looking. How many fish haven’t I killed ! There were few so

good at splitting a herring as I was! The fish were frightened, frightened, I tell

you.

They looked up at the clouds as if to say: “God blessed us as well as you.” What do

you make of that? I say, we take the fish, and God takes us. We must all die—beasts

must die, and men must die … We must all come to it . . . but we can’t all come

to it together. That would be like turning a full cask into an empty one. I might

be

frightened if I stayed behind in the empty cask . . . but not if we all went together

into

the other cask. To be frightened is nothing … to be frightened only means you’ve

stood on tiptoe and looked over the edge . . .

A HYMN IN PRAISE OF NEPTUNE.

Of Neptune’s empire let us sing.

At whose command the waves obey;

To whom the rivers tribute pay,

Down the high mountain sliding;

To whom the scaly nation yields

Homage for the crystal fields.

Wherein they dwell;

And every sea-god pays a gem

Yearly out of his watery cell.

To deck great Neptune’s diadem.

The Tritons dancing in a ring,

Before his palace gates do make

The water with their echoes quake.

Like the great thunder sounding:

The sea-nymphs chant their accents shrill,

And the Syrens taught to kill

With their sweet voice,

Make every echoing rock reply,

Unto their gentle murmuring noise,

The praise of Neptune’s empery.

Thomas Campion.

THE WATERS OF THE MOON.

I dreamed I came to an enchanted vale,

Where, shadowed by dim mountains of delight,

The never-resting opal waters gleamed;

And as the moon hung like a blossom frail

And tremulous athwart the languid night,

I bathed in magic wells of crimson fire,

Whence coming forth with glowing limbs, I dreamed

I met a spirit shining as the dawn.

I looked on eyes filled with night’s mystery,

On slumbering hair more soft than rainbow mist

Of wind-blown fountains on a flowering lawn,

Till the air trembled with the sweet desire

Of murmured laughing speech. Then star-lit eyes

Gleamed at my eyes, rapturous dream lips kissed

My lips and brought their hidden memory.

I knew how I had looked into those eyes,

Kissed those red lips, and loved that slumbering hair

Dim years ago, and while the immortal gaze

Yet held my gaze I strove to cry aloud.

But all things passed; the radiant dreamland ways

Were lost in darkness, as a rising cloud

Fades into mist, and sleep became despair.

I have dreamed many dreams these many years,

But I have never met that shining one,

Whose brow was rapt beyond all hopes and fears,

Sweet as the moon and splendid as the sun.

Cecil French.

HAND COLOURED PRINTS by Pamela Colman Smith, of

Miss Ellen Terry:—

as “‘Portia’ hurrying to the Railway Station” … … Price Is. Post free.

as “Sans Gêne” … … … … … … ” Is. ”

as “Queen Katharine” … … … … … ” 2s. 6d. ”

as “Mistress Page” … … … … … … ” 2s. 6d. ”

as “Hiördis” (in the Vikings) … … … … ” 2s. 6d. ”

Subscribers to The Green Sheaf may obtain this last print for Is. Post free.

The Green Sheaf School of Hand Colouring, undertakes small Editions of

Books, Programmes, Cards, etc., for private Theatricals and Dances, also cards for

advertising

purposes. The School supplies the designs and executes the orders complete where desired.

For further particulars apply to The Editor, The Green Sheaf, 14 Milborne Grove, The

Boltons, S.W.

⎯

From ELKIN MATHEWS’ LIST.

Amiel (Henri-FrÉdÉric).—PENSEÉS FROM THE JOURNAL IN-

TIME OF. Arranged by D. K. Petano. Globe 8vo. 3s. net.

LOVE LETTERS (THE) OF A PORTUGUESE NUN TO A

FRENCH CAVALIER. By Marianna Alcoforado. Printed on Hand-made paper.

Fcap. 8vo. Bound in leather. 3s. 6d. net.

MEMORIES OF AN OLD COLLECTOR. By Count M.

Tyskiewicz. Translated by Mrs. Andrew Lang. With 9 plates. Crown 8vo. 4s. 6d. net.

POWELL (PROFESSOR F. YORK).—QUATRAINS FROM THE RUBAI-

YAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM. A new version of the Tentmaker’s Philosophy. Printed

on hand-made paper. Pott 4to. 3s. net.

RILEY (J. WHITCOMB). RUBAIYAT OF DOC SIFERS. With 44

Illustrations. Crown 8vo. 2s. 6d. net. (Pub. 6s.)

TOMSON (GRAHAM R.).—CONCERNING CATS: A Book of Poems

by many Authors. Selected by. Illustrated by Arthur Tomson. Post 8vo. 2s. 6d. net.

TYNAN (KATHARINE).—IRISH LOVE SONGS: Selected by. With a

Portrait of Mangan. Post 8vo. 2s. 6d. net.

WEST (J. WALTER, A.R.W.S.).—FULBECK: A Pastoral in Verse.

Printed on Japanese vellum paper from the Author’s own script with binding in vellum

and

gold, end-papers, and 12 Illustrations in photogravure and line from the Author’s

own designs.

WHITE (W. HALE).—AN EXAMINATION OF THE CHARGE OF

APOSTACY AGAINST WORDSWORTH. Crown 8vo. 3s. 6d. net.

YEATS (W. B.)—KATHLEEN NI HOOLIHAN. A Play in One

Act, and in Prose. Pott 8vo. 5s. net.

⎯

London: ELKIN MATHEWS, Vigo Street, W.

15The Green Sheaf

THE GALLERY, ONE PRINCE’S TERRACE,

HEREFORD ROAD, W.

JOHN BAILLIE requests the honour of a visit. Exhibitions every

three weeks.

A fine Collection of Modern Jewellery always on view.

Classes for Enamelling, Metal-work, Carving, Bookcasing, Water

Colours, Fan Painting, Wood Engraving, &c.

Gallery open 10.30 a.m. to 6 p.m.

⎯

The next number of The Green Sheaf will contain a Dream by

John Todhunter, poems by Alix Egerton and Cecil French, and the

First Act of Deirdre by A. E.

Drawings by Dorothy Ward, Cecil French, Pamela Colman Smith.

A few proof copies of the Rossetti drawing of Mrs. Stirling are

for sale at Eighteen pence each, post free.

There will be thirteen Numbers of The Green Sheaf in a year,

printed on antique paper and hand-coloured, and the Subscription is

Thirteen shillings annually, post free. Single Copies may be had at

Thirteen pence each.

Edited and Published by PAMELA COLMAN SMITH,

14, Milborne Grove, The Boltons, London, S.W.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

MLA citation:

The Green Sheaf, No. 6, 1903. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/gsv6_all/