XML PDF

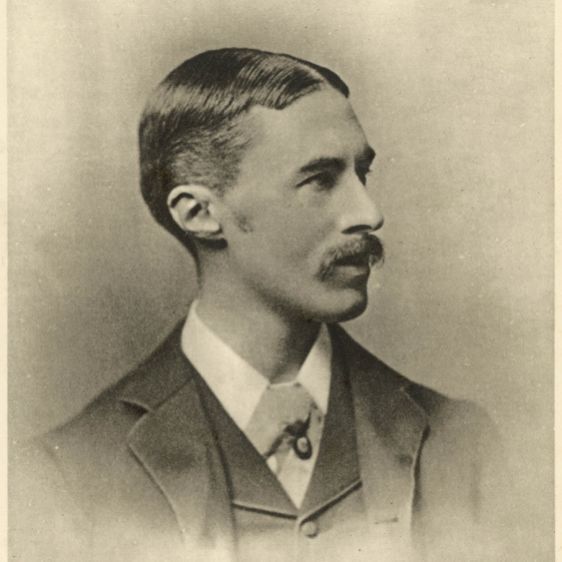

A.E. (Alfred Edward) Housman

(1859 – 1936)

Poet and classical scholar A. E. Housman would probably have objected to having his biography listed alongside those of Arthur Symons (1865-1945) and Ernest Dowson (1867-1900). Reflecting on his decision not to reprint some of his work in A Book of Nineties Verse, he wrote in 1928 that “to include me in an anthology of the Nineties would be just as technically correct, and just as essentially inappropriate, as to include Lot in a book of Sodomites; in saying which I am not saying a word against sodomy” (Letters 2.93). Indeed, A Shropshire Lad (1896), Housman’s best-known book of poetry, is often associated either with pastoral timelessness or with the First World War (during which soldiers read it in the trenches and its popularity soared). Nonetheless, his writing should be understood in the context of late nineteenth-century culture.

Housman was born in 1859, the oldest of seven siblings. His brother Laurence (1865-1959) and sister Clemence (1861-1955) would both become artists, writers, and activists. The Housmans were a tight-knit family, and Alfred was deeply affected by the loss of his mother Sarah on his twelfth birthday. Though the Housman children’s upbringing had been one of middle-class comfort, their father Edward—a solicitor—tended to live beyond his means, and the family experienced financial troubles. Academically gifted from an early age, in 1877 Alfred won a scholarship to study Classics at St. John’s College, Oxford.

However, he shocked his family and friends when in 1881 he failed his final examinations. This may have been because he was pursuing his own interests instead of the assigned curricula (Norman Page posits that Oxford satisfied “neither his appetite for exact scholarship nor his love of poetry” [40]); it may have been because he was worried about his father’s bad health; it may have been because he was too confident in his own abilities. And it may have been because he had fallen hopelessly in love with his friend and classmate Moses Jackson (1858-1923).

Failure at Oxford meant that Housman spent a decade away from academia. He passed the Civil Service exam in 1882, joining Jackson at the Patent Office in London; the two men lodged together with Jackson’s brother Adalbert until 1885, when Housman moved out. Jackson relocated to India in 1887, returning briefly in 1889 to marry Rosa Chambers (Housman was not invited to the wedding). It seems likely that Jackson became aware of Housman’s feelings for him and that this drove the friends apart, although they continued to correspond throughout their lives.

Housman stayed at the Patent Office after Jackson’s departure. While working there, he kept up his classical scholarship, publishing dozens of papers on Ovid, Aeschylus, Horace, and more. In 1892, despite his lack of traditional credentials, he secured a job as Professor of Latin at University College London. Here he acquired a reputation as a brilliant scholar, an aloof and formal teacher, and a caustic wit—which made it even more surprising when in 1896 he published A Shropshire Lad, a slim volume of plaintive ballad-like verses that has never gone out of print since.

These sixty-three short poems form the main basis of Housman’s literary reputation. Occasionally inhabiting the perspective of a young rustic named Terence Hearsay, A Shropshire Lad depicts regretful nostalgia, lost happiness, exile, ill-fated love, and early death. The citified hedonism stereotypically associated with fin-de-siècle poetry here manifests itself as a quiet rejection of Christian consolation (“I shall have lived a little while / Before I die for ever”) and a concomitant longing not for urban artifice but for natural beauty. Facing mortality, speakers urge “Think no more, lad; laugh, be jolly,” and resolve that “About the woodlands I will go / To see the cherry hung with snow.” Housman’s terse and repetitive language is deceptively simple and hauntingly beautiful. It is peppered with Biblical, Shakespearean, and classical allusions; it also shows the influence of Matthew Arnold (1822-1888), whom Housman admired, and of the border ballads. Poems from A Shropshire Lad have frequently been set to music, notably by Arthur Somervell (1863-1937), Ralph Vaughn Williams (1872-1958), and George Butterworth (1885-1916). The volume has also inspired numerous theatrically despondent parodies. Hugh Kingsmill (1889-1949), for instance, begins his imitation with “What, still alive at twenty-two, / A clean, upstanding chap like you?” (see Richards 345). Housman, himself an occasional writer of comic verse, acknowledged this parody as “the best I have seen, and indeed the only good one” (Letters 1.597).

Later in his life, Housman maintained that “I did not begin to write poetry in earnest until the really emotional part of my life was over” and that A Shropshire Lad’s philosophy sprang from “observation of the world” rather than “personal circumstances” (Letters 2.329). But his preface to Last Poems (1922) instead mentions “the continuous excitement under which in the early months of 1895 I wrote the greater part of my other book.” Notably, the trials of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) were taking place in the early months of 1895. Housman did not speak openly of his sexuality, not even to his brother Laurence, who joined a secret homosexual society called the Order of Chaeronea. Yet the elegantly restrained mournfulness of A Shropshire Lad (“Smart lad, to slip betimes away / From fields where glory does not stay”; “But dead or living, drunk or dry, / Soldier, I wish you well”; “With rue my heart is laden / For golden friends I had”) allows Housman both to express and to repress his romantic desires as he gazes wistfully on doomed young men.

When Wilde was released from prison, Housman sent him a copy of the book, echoes of which can be heard in Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol. Though hardly a member of the bohemian set, Housman was also friends with William Rothenstein (1872-1945) and Edmund Gosse (1849-1928), as well as a reader of the erotica of A. C. Swinburne (1837-1909). He was a regular visitor to Paris and, like John Addington Symonds (1840-1893) and Frederick Rolfe (1860-1913), to Venice.

In 1903, he published a poem called “The Oracles” in the first volume of The Venture. Laurence, who co-edited this magazine with W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1965), had asked his brother to contribute an essay on Coventry Patmore (1823-1896). But Housman dismissed this as “an awful job” and instead sent Laurence two poems (“The Oracles” and “Atys”), telling him to “print whichever you think the least imperfect” (Letters 1.153). This uncharacteristic appearance in a little magazine can be attributed to fraternal loyalty: Housman explained to Laurence in 1907 that “I contributed to the Venture only because you were the editor,” adding that he has no interest in appearing in another magazine called The Neolith (Letters 1.206).

This was the first publication of “The Oracles” (which is mistakenly titled “The Oracle” within The Venture’s pages but is given its correct name in this magazine’s table of contents). Although Housman would later write that “I do not admire the oracle poem quite so much as some people do” (Letters 2.495), he did elect to reprint it in Last Poems. The speaker of “The Oracles,” who sounds very much like a refugee from Shropshire, notes that prophecies can no longer be heard at the ancient shrines of Dodona and Delphi. Turning instead to “[t]he heart within” and personifying it as a priestess whom he addresses as “my lass,” he receives its message of universal mortality with stoic resignation (“the news is news that men have heard before”). Housman’s poem concludes with a description of the Battle of Thermopylae, in which the outnumbered Greeks who heroically fought to the death against Persian invaders were said to accept their fate with similar stoicism (“The Spartans on the sea-wet rock sat down and combed their hair”). The classical focus of “The Oracles” sets it apart from the other literary offerings in The Venture’s first volume—although this volume does contain woodcut images of “Pan and Psyche,” “The Death of Pan,” “Daphne and Apollo,” and “Psyche’s Looking-Glass.”

W. H. Auden (1907-1973) was perhaps too flippant, but not entirely misguided, when he wrote of Housman “Deliberately he chose the dry-as-dust, / Kept tears like dirty postcards in a drawer” (182). Housman continued to lead a rather quiet, regimented life after the success of his first volume of poetry. In 1911, he became Professor of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge. His magnum opus, a five-volume edition of Manilius that took him decades to complete and that cemented his reputation as a world-leading scholar, may indeed seem dry to those who know him chiefly as the author of A Shropshire Lad. However, his engagingly acerbic prose style and fierce devotion to accuracy ensure that his textual criticism is still admired today. Housman usually cordoned off his academic life from his identity as a celebrated poet, but he permitted these worlds to come together in his 1933 Leslie Stephen lecture “The Name and Nature of Poetry.” Here he insisted that poetry ought to be sensual and emotional rather than intellectual, identifying his own verse as a “morbid secretion, like the pearl in the oyster” (48).

Having published no new volume of verse since 1896, in 1922 Housman brought out Last Poems. He may have been spurred by news that Moses Jackson was dying—although Jackson, now in Canada, lived long enough to receive a copy of the book. Last Poems appeared in the same year as T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, but in style and tone it still tends to resemble A Shropshire Lad.

Housman kept lecturing at Cambridge until his death in 1936. Laurence, whom he made his literary executor, soon assembled the posthumous volume More Poems (1936) from his brother’s unpublished manuscripts. Several of these verses, along with some others included in Housman’s collected works and known as Additional Poems, touch on the writer’s unrequited love for Jackson. And memorably, “Oh who is that young sinner with the handcuffs on his wrists?” shows a Wilde-like figure being dragged off to prison for “the nameless and abominable colour of his hair.” In 1967, Laurence’s essay “A. E. Housman’s ‘De Amicitia’” was unsealed (Laurence had stipulated that it be kept unread in the British Library for twenty-five years). The essay frankly addresses Housman’s homosexuality and provides an important interpretive lens for his melancholy, pessimistic poetry. A Shropshire Lad, with its eloquent silences, is very much a product of its time—just as Housman himself, despite his longevity and his unwillingness to be classified as a “Nineties” poet, shaped and was shaped by late nineteenth-century culture.

©2021, Veronica Alfano, Research Fellow, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

Selected Publications by Housman

- “The Application of Thought to Textual Criticism.” Proceedings of the Classical Association, vol. 18, August 1921, pp. 67-84.

- Introductory Lecture: Delivered Before the Faculties of Arts and Laws and of Science, in University College, London, October 3, 1892. Cambridge University Press, 1892.

- Last Poems. Grant Richards, 1922.

- The Letters of A. E. Housman, edited by Archie Burnett. Clarendon Press, 2007.

- More Poems. London: Jonathan Cape, 1936.

- The Name and Nature of Poetry: The Leslie Stephen Lecture Delivered at Cambridge, 9 May 1933. Macmillan, 1933.

- “The Oracle[s].” The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, vol. 1, 1903, p. 39. Venture Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2021. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021, https://1890s.ca/vv1-ae-housman-oracle.

- The Poems of A. E. Housman, edited by Archie Burnett. Clarendon Press, 1997.

- A Shropshire Lad. London: Kegan Paul, 1896.

Selected Publications about Housman

- Alfano, Veronica. “A. E. Housman’s Ballad Economies.” In Economies of Desire at the Victorian Fin de Siècle: Libidinal Lives, edited by Jane Ford, Kim Edwards Keates, and Patricia Pulham, Routledge, 2016, pp. 35-61.

- Auden, W. H. “A. E. Housman.” In Collected Poems, edited by Edward Mendelson. Vintage Books, 1991.

- Bayley, John. Housman’s Poems. Clarendon Press, 1992.

- Blocksidge, Martin. A. E. Housman: A Single Life. Sussex Academic Press, 2016.

- Bristow, Joseph. “How Decadent Poems Die.” In Decadent Poetics: Literature and Form at the British Fin de Siècle, edited by Jason David Hall and Alex Murray, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, pp. 26-45.

- Burnett, Archie. “Silence and Allusion in Housman.” Essays in Criticism, vol. 53, no. 2, 2003, pp. 151-173.

- Efrati, Carol. The Road of Danger, Guilt, and Shame: The Lonely Way of A. E. Housman. Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 2002.

- Gardner, Philip, editor. A. E. Housman: The Critical Heritage. Routledge, 1992.

- Holden, Alan W. and J. Roy Birch, editors. A. E. Housman: A Reassessment. Macmillan, 2000.

- Housman, Laurence. “A. E. Housman’s ‘De Amicitia.’” Encounter, vol. 29, October 1967, pp. 33-40.

- Howarth, Peter. “Housman’s Dirty Postcards: Poetry, Modernism, and Masochism.” PMLA, vol. 124, no. 3, May 2009, pp. 764-781.

- Leggett, B. J. The Poetic Art of A. E. Housman: Theory and Practice. University of Nebraska Press, 1978.

- Page, Norman. A. E. Housman: A Critical Biography. Macmillan, 1983.

- Richards, Grant. Housman: 1897-1936. Oxford University Press, 1942.

- Ricks, Christopher, editor. A. E. Housman: A Collection of Critical Essays. Prentice-Hall, 1968.

- Robbins, Ruth. “‘A very curious construction’: Masculinity and the Poetry of A. E. Housman and Oscar Wilde.” In Cultural Politics at the Fin de Siècle, edited by Sally Ledger and Scott McCracken, Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 137-159.

- Vicinus, Martha. “The Adolescent Boy: Fin-de-Siècle Femme Fatale?” In Victorian Sexual Dissidence, edited by Richard Dellamora, University of Chicago Press, 1999, pp. 83-106.

MLA citation:

Alfano, Veronica. “A. E. (Alfred Edward) Housman (1859-1936),” Y90s Biographies.. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021, https://1890s.ca/aehousman_bio/.