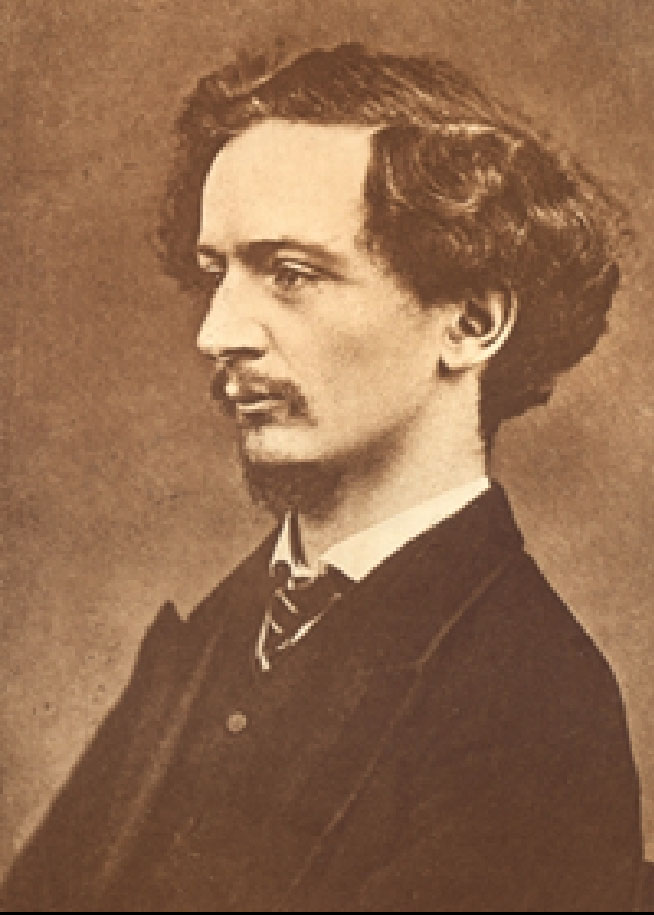

Algernon Charles Swinburne

(1837 – 1909)

Algernon Charles Swinburne was one of the most controversial literary figures of the Victorian period. His first collection of poetry, Poems and Ballads Series 1, caused outrage on its publication in 1866 due to the frank sexuality of its subject matter. Inspired in part by the greater license of French writers, especially Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), whose Les Fleurs du mal (1857) was an important influence, Swinburne interrogated the darker side of sexual love and emotion in poems that featured, among other things, lesbianism, necrophilia, and sado-masochism. Particularly galling to his critics was the fact that subjects generally considered beyond the pale were celebrated in verse that showed a brilliant mastery of poetic form. Swinburne’s superb metrical capability, fluent lyricism, and consummate craftsmanship challenged the convention that only low, coarse, and reprehensible forms of expression could communicate matter deemed dubious or morally improper. In this and subsequent verse collections, Swinburne’s mastery of poetic forms such as the sestina, ballade, border ballad, canzone, sonnet, and roundel helped spur successors such as Ernest Dowson (1867-1900), Edmund Gosse (1849-1928), Agnes Mary Frances Robinson (1857-1944), and Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) to their own experimentation with traditional forms. Many decadent poets were also indebted to Swinburne’s sexual daring, which made it easier for them to tackle provocative subjects, although none of their poems would ever raise the storm generated by Swinburne’s first volume. The variety of mood and tone in Swinburne’s verse ensured that his rhythms and cadences echo in many late-Victorian poets.

Poems and Ballads Series 2 (1878), predominantly elegiac and wistful in tone, strikes a very different note from its better-known predecessor, and arguably inspires the reflective melancholy and nostalgia of many fin-de-siècle lyrics. Swinburne was also a distinguished critic who wrote the first English review of Baudelaire’s poems (1862) and the first literary monograph on William Blake (1868). Part influenced by the art and literary criticism of the French writer Théophile Gautier, he pioneered an impressionistic “aesthetic” style of prose that, perfected by Walter Pater (1839-1894), would be taken up with diverse variations by a host of late nineteenth-century writers including Vernon Lee (1856-1935), Arthur Symons (1865-1945), and W. B. Yeats (1865-1939).

The eldest of six surviving children, Swinburne was born on 5 April 1837 into an aristocratic High-Church family. His father Captain (later Admiral) Swinburne and his mother Lady Jane (née Ashburnham) settled at East Dene, Bonchurch, on the Isle of Wight, where Swinburne spent his childhood and developed his love of the sea. He quickly showed a keen interest in literature, especially poetry, and his mother, a gifted linguist, taught him French and Italian. Aged twelve, he entered Eton College where he won the Prince Consort’s Prize for Modern Languages in 1852. However, the larger part of his formal education was in the classics, which dominated the public school curriculum at this time. His love of Greek literature, in particular the lyrical fragments of Sappho first encountered at Eton, would have a lasting impact on his poetry. His enduring sexual obsession with pain and flagellation also dates from his school days, when discipline was commonly enforced by flogging, a rite de passage for many middle- and upper-class men that, in some cases like Swinburne’s, engendered a sexual fixation with corporal punishment. In 1854 he left Eton and in 1856 entered Balliol College, University of Oxford. There he spent much time reading widely and writing poetry. He also became a member of the Old Mortality Society, an intellectual group founded by his close friend John Nichol (1833-1894), who encouraged his rejection of Christianity. At Oxford, he also met the Pre-Raphaelites William Morris (1850-1934), Edward Jones (1833-1898) (later Burne-Jones), and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) painting the walls of the Oxford Union, and began important friendships with all three.

Swinburne left Oxford in 1860 without taking his final examinations and moved to London, where he published two verse-plays as the collection The Queen-Mother and Rosamond . The next five years were spent perfecting his verse and writing some early essays and reviews, a witty epistolary novel of sexual manners later published pseudonymously in The Tatler as the serial A Year’s Letters (1877), and his book on Blake. Critics now believe that his disappointment at the marriage of his cousin Mary Gordon (1840-1926) to Captain Disney Leith (1819-1892) in 1864 coloured a number of poems in his 1866 collection that deal with the pain of the abandoned male lover. In 1865 he published his highly acclaimed classical verse drama Atalanta in Calydon , and Chastelard, a verse play about Mary Queen of Scots and the French poet, Chastelard, featuring one of his favourite themes — the femme fatale and her masochistic male lover.

Swinburne’s only known sexual relationship was a brief affair in 1867 with the actress and poet Adah Menken (1835-1868), which was probably unconsummated. He frequented a flagellant brothel in St John’s Wood in 1868-1869. During the 1870s he suffered increasingly poor health due to alcoholism but was eventually rescued from an untimely death by his friend Theodore Watts (1832-1914) (Watts-Dunton after 1896), a solicitor and literary critic, who took him off to recuperate in Putney. The pair moved into No. 2 “The Pines,” where Swinburne lived peacefully for the rest of his life, protected by Watts, who weaned him off alcohol and kept him out of the way of his more disreputable acquaintances. He died on 10 April 1909.

Swinburne’s poetry after 1866 was much less sexually provocative although he never managed to shrug off his early notoriety. His political passion for a reunified Italy resulted in the revolutionary verse of Songs before Sunrise (1871). Many critics believe his best work to be his Arthurian verse epic Tristram of Lyonesse (1882), a treatment of the fatal romance between the singer-harpist Tristram and Iseult, wife of King Mark of Cornwall, which, like Swinburne’s strongest later poems such as “A Nympholept” and “The Lake of Gaube,” explores the rhythms and energies of the natural world. The collection A Century of Roundels (1883) shows his lyrical gifts and mastery of form. Much of his best earlier criticism is collected in Essays and Studies (1875), although there are many valuable insights in the later work on Charlotte and Emily Brontë, Shakespeare, Victor Hugo, and Charles Dickens among others. His letters brim with wit and vitality.

© 2011, Catherine Maxwell

Catherine Maxwell is Professor of Victorian Literature at Queen Mary, University of London, and author of The Female Sublime from Milton to Swinburne: Bearing Blindness (Manchester UP, 2001), Swinburne (Northcote House, 2006, and Second Sight: The visionary Imagination in Late Victorian Literature (Manchester UP, 2008).

Selected Publications by Swinburne

- Swinburne, Algernon. The Poems of Algernon Charles Swinburne . 6 vols. London: Chatto & Windus, 1904.

- —. The Swinburne Letters. Ed. Cecil Y. Lang. 6 vols. New Haven: Yale UP, 1959-62.

- —. Swinburne as Critic. Ed. C.K. Hyder. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972.

- —. A Year’s Letters. Ed. Francis Jacques Sypher. New York: New York UP, 1974.

- —. Poems and Ballads & Atalanta in Calydon. Ed. Kenneth Haynes. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2000.

- —. Uncollected Letters of Algernon Charles Swinburne . Ed. Terry Meyers, 3 vols. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2004.

- —. Swinburne: The Major Poems and Selected Prose. Ed. Jerome McGann and Charles Sligh. New Haven: Yale UP, 2005.

Selected Publications about Swinburne

- Levin, Yisrael, ed. A. C. Swinburne and the Singing Word: New Perspectives on the Mature Work . Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010.

- Maxwell, Catherine. The Female Sublime from Milton to Swinburne: Bearing Blindness . Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001.

- —. Swinburne. Writers and Their Work. Tavistock: Northcote House, 2006.

- McGann, Jerome. Swinburne: An Experiment in Criticism . Chicago: U Chicago P, 1972.

- Riede, David. Swinburne: A Study of Romantic Myth-Making . Charlottesville: U of Virginia P, 1978.

- Rooksby, Rikky. Swinburne: A Poet’s Life. Aldershot: Scolar, 1997.

- —, and Nicholas Shrimpton, eds. The Whole Music of Passion: New Essays on Swinburne . Aldershot: Scolar, 1993.

MLA citation:

Maxwell, Catherine. “Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909),” Y90s Biographies, 2011. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019, https://1890s.ca/swinburne_bio/.