THE DIAL

NO. 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

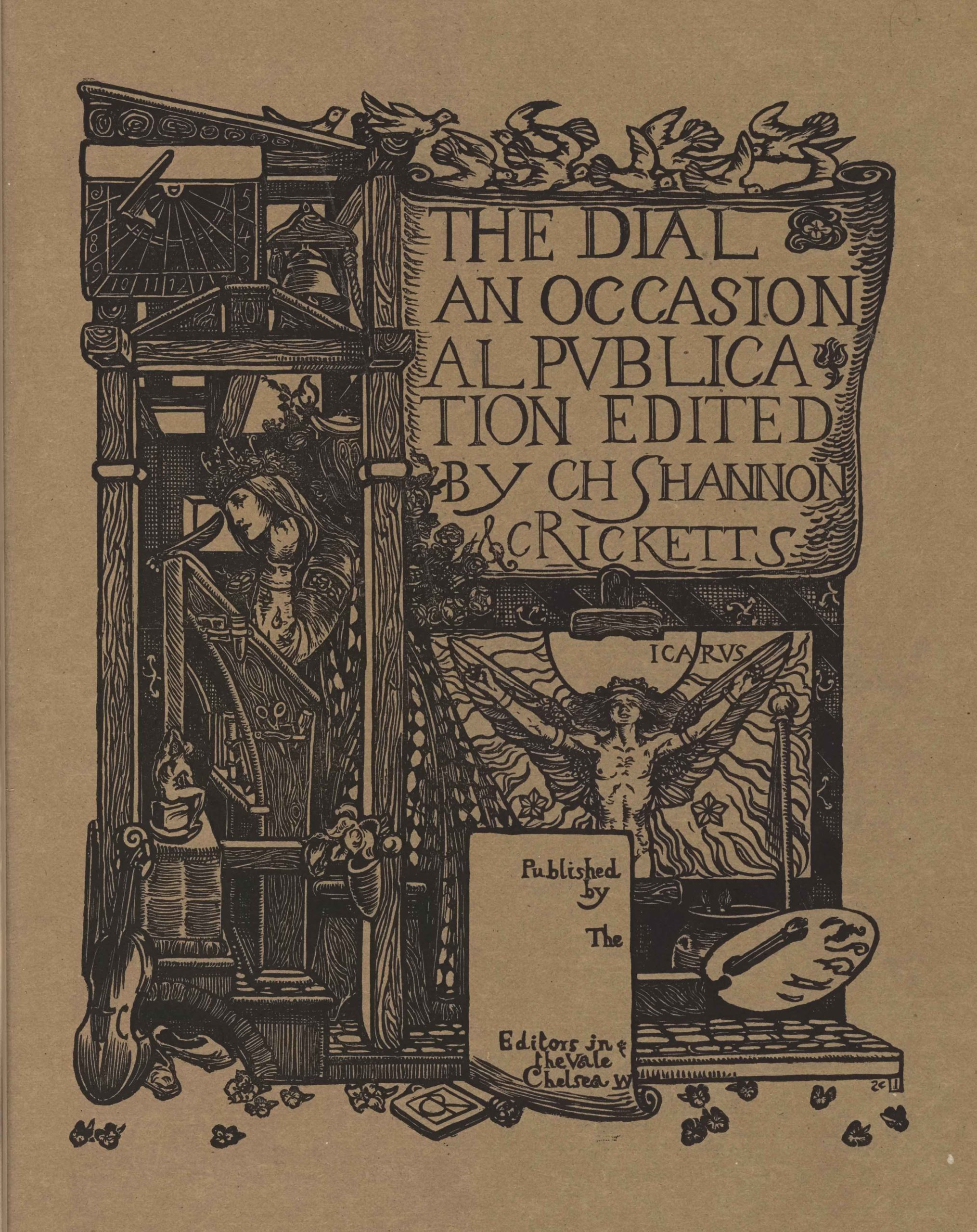

Front Cover designed and engraved by Charles Ricketts

Table of Contents . . . [iii]

❧ Full Page Illustrations

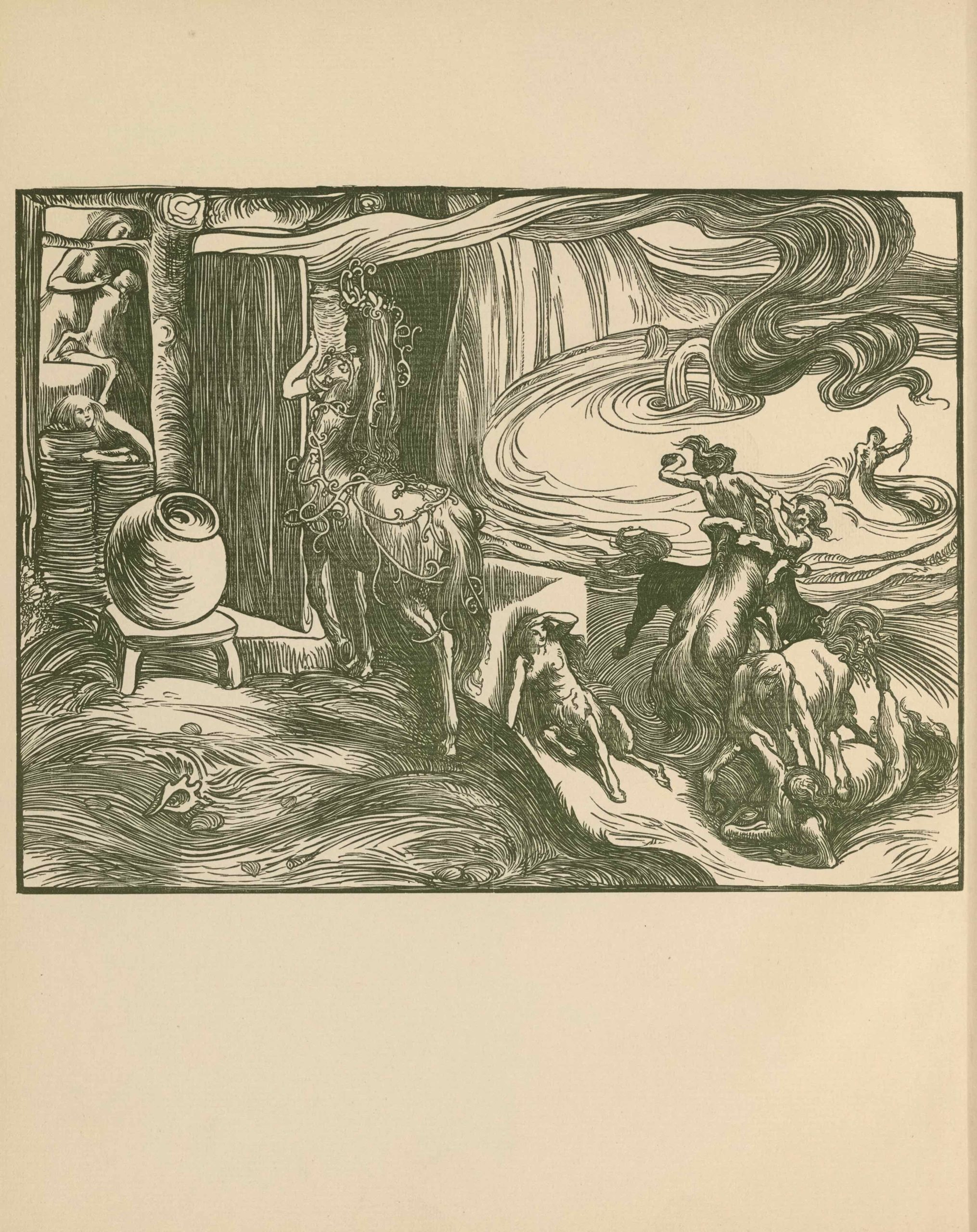

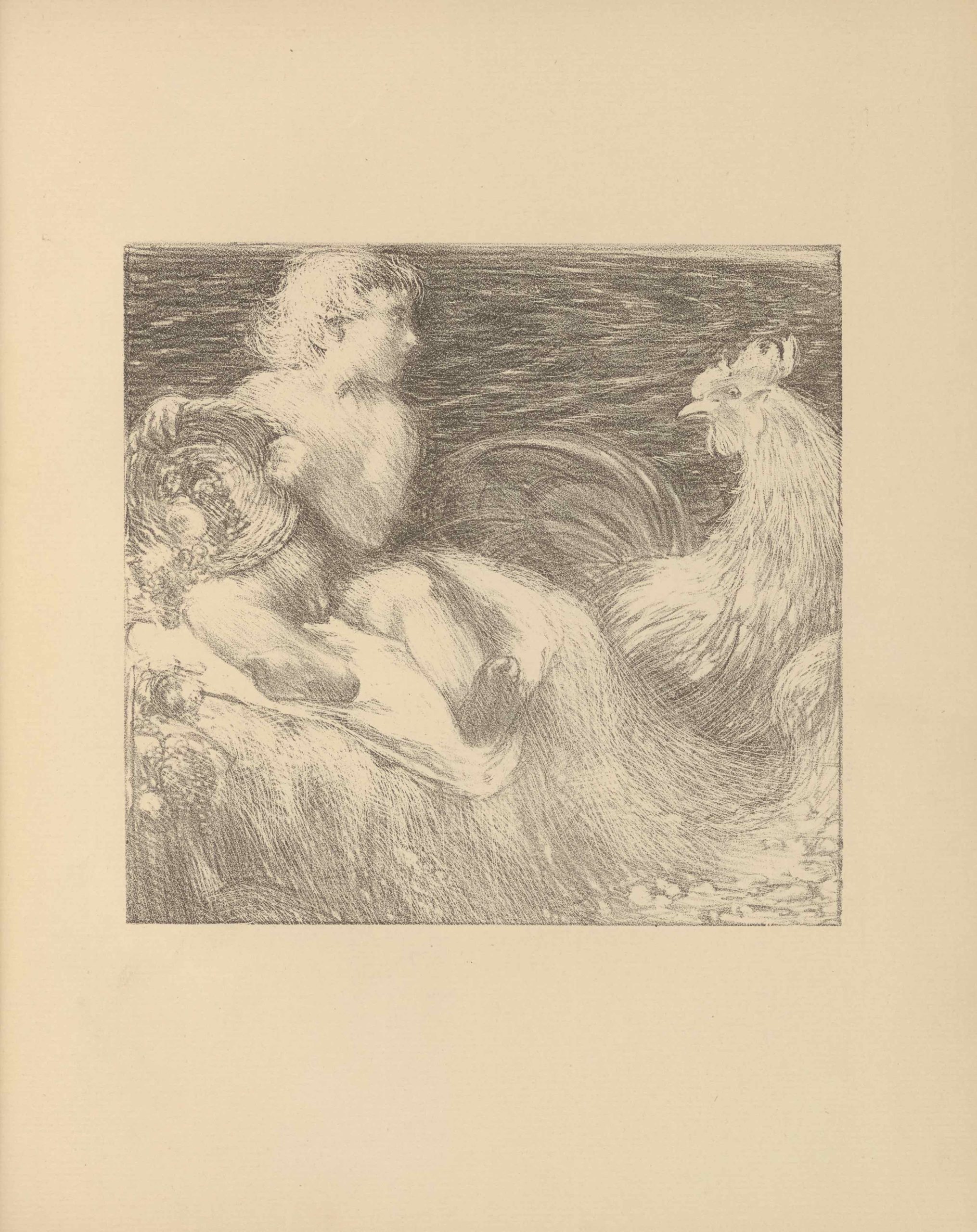

Frontispiece: CENTAURS an experiment in line designed by Reginald Savage

drawn and engraved on the wood by Charles S. Ricketts . . . facing page 1

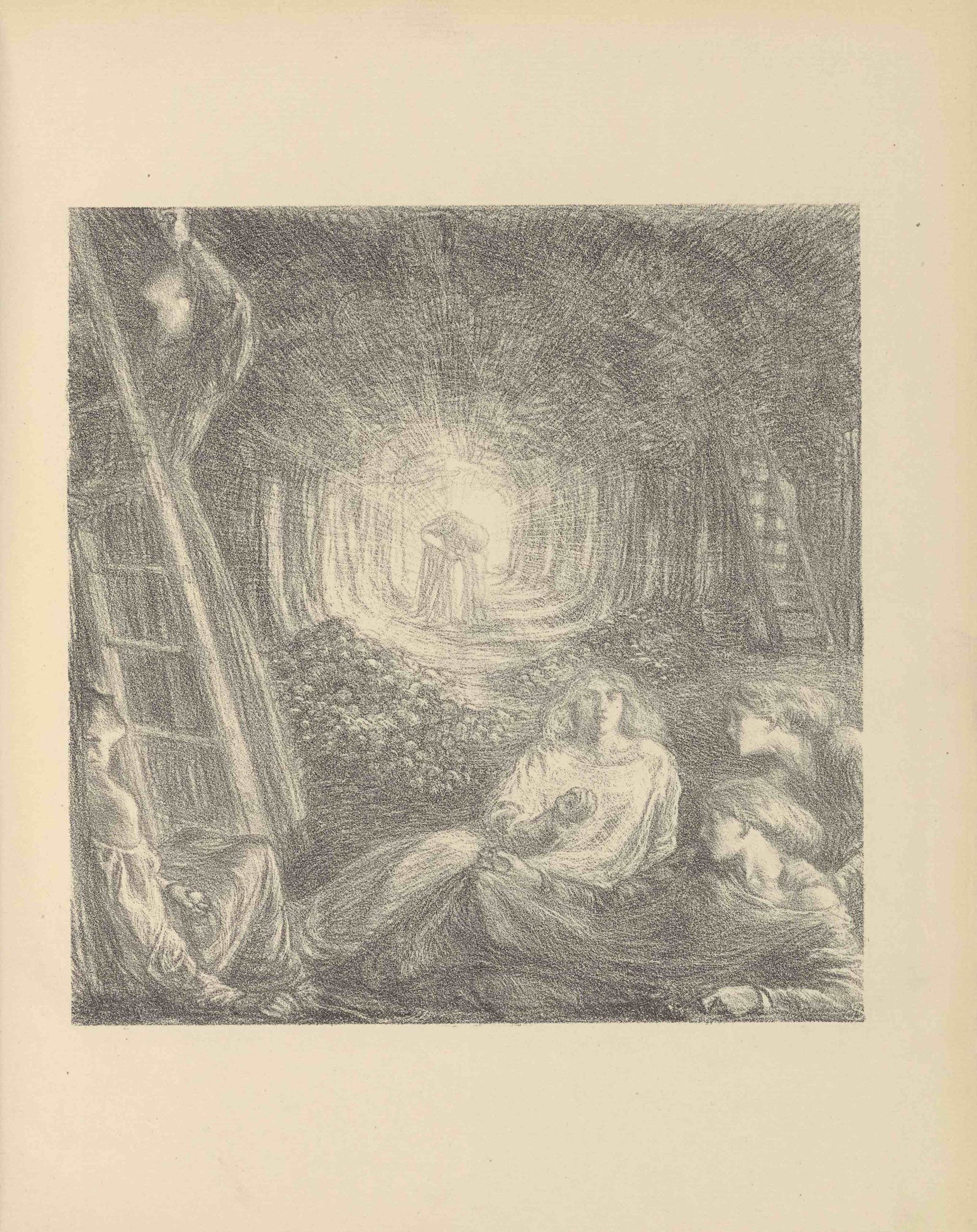

A ROMANTIC LANDSCAPE an original lithograph drawn upon the stone by Charles Haselwood Shannon . . . facing page 5

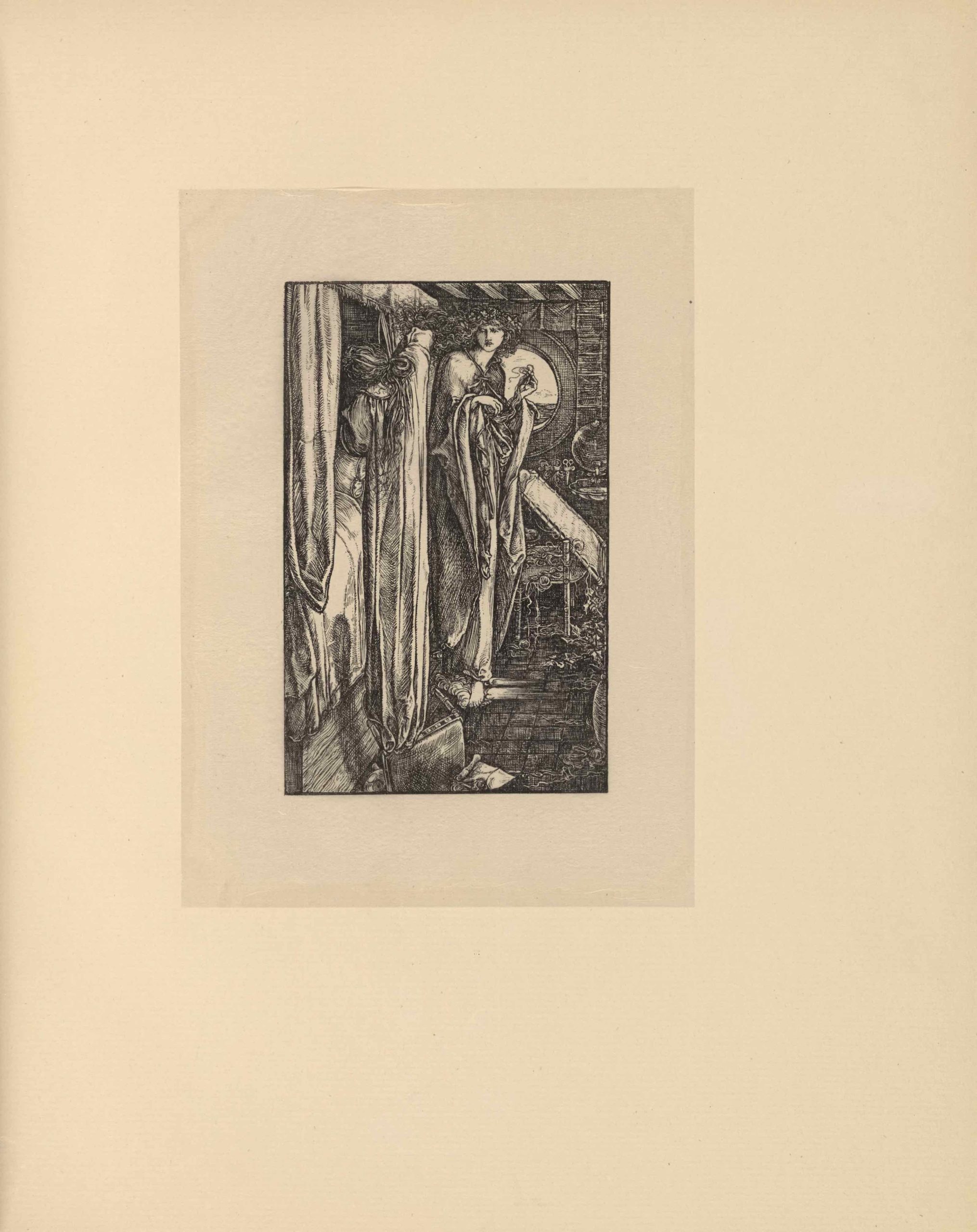

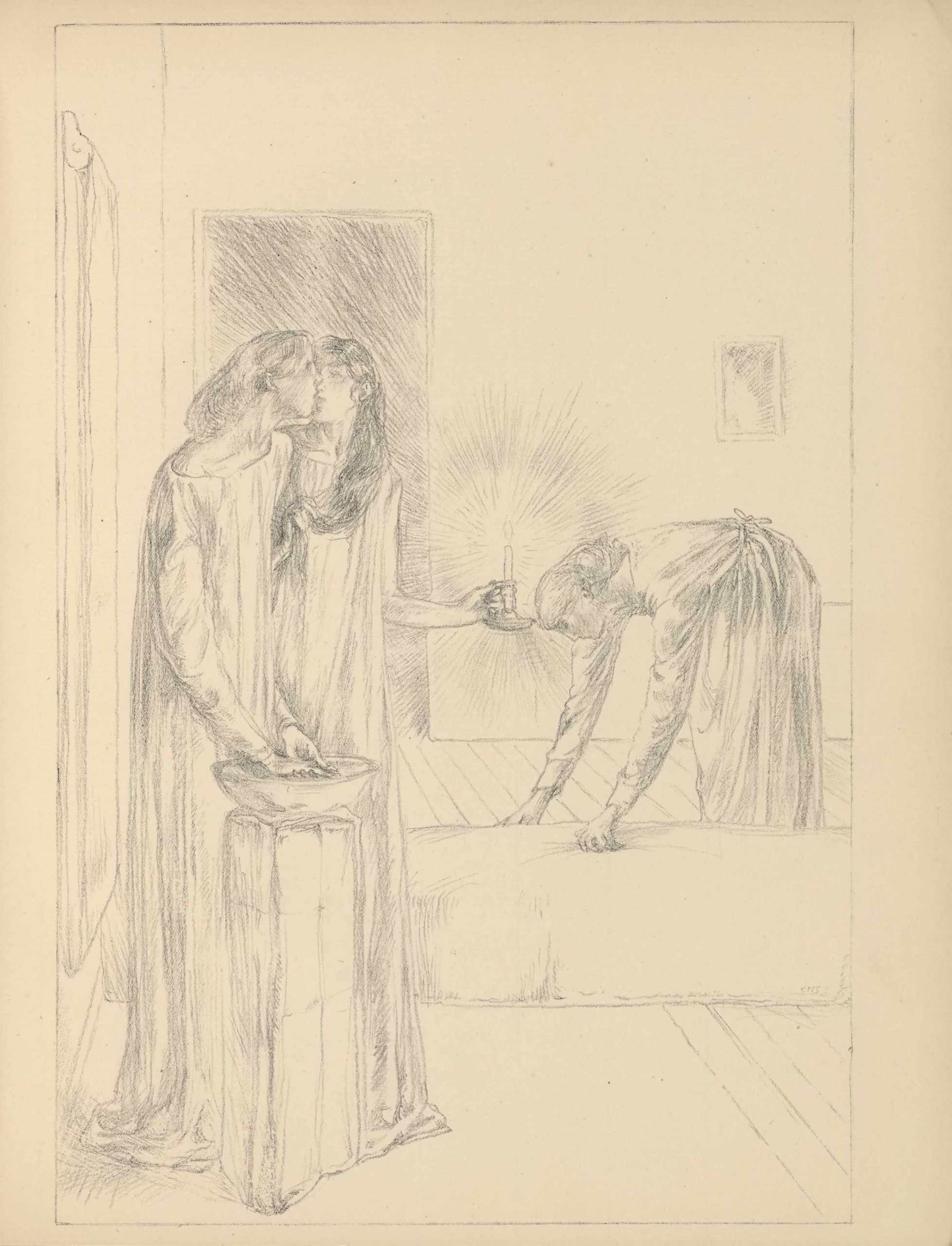

PHÆDRA AND ARIADNE

—“And you will see Ariadne gazing at her sister Phædra who hangs by a rope” ❧ Pausanius.

A reproduction of a pen drawing by Charles Ricketts . . . facing page 9

WHITE NIGHTS an original lithograph by Charles Shannon . . . facing page 13

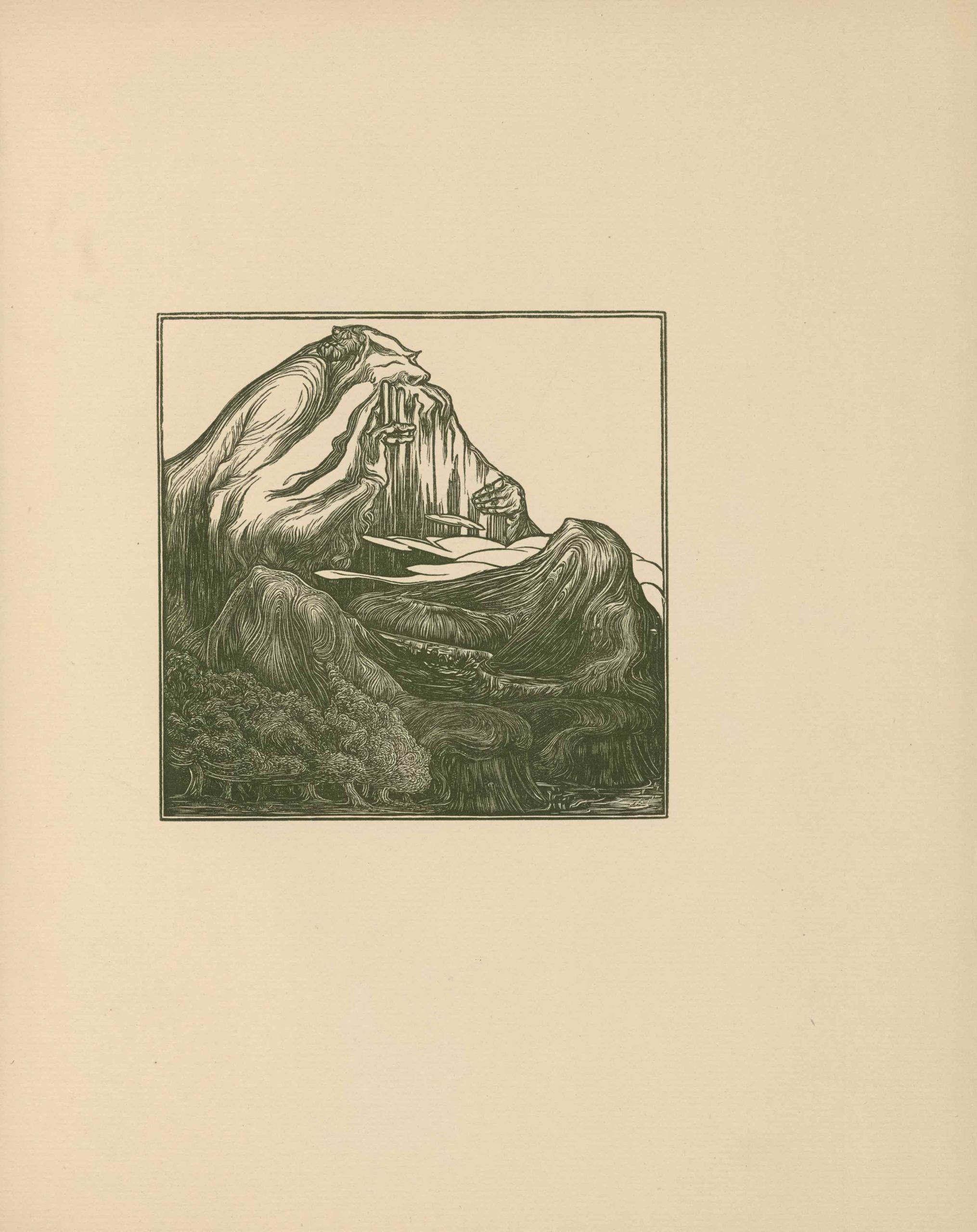

PAN MOUNTAIN an original woodcut designed and engraved on the wood BY T. Sturge Moore . . . facing page 17

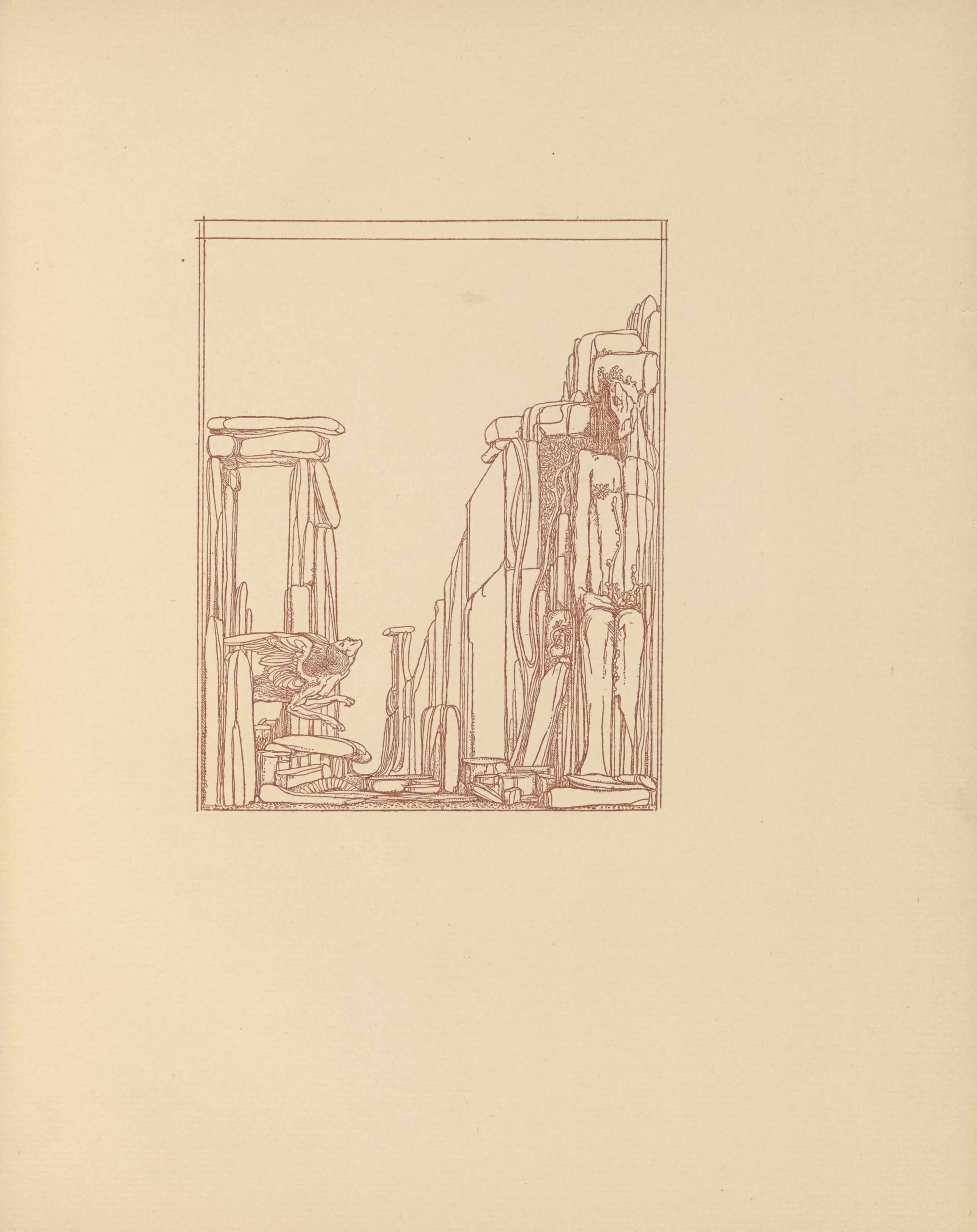

IN THE THEBAID an illustration to a poem “The Sphinx” by Oscar Wilde

to be published at the sign of the Bodley Head ❧ a reproduction of a pen drawing by

Charles Ricketts . . . facing page 19

AN INTRUDER an original lithograph drawn upon the stone by Charles Shannon . . . facing page 21

SOLITUDE an original woodcut drawn and engraved on the wood by Lucien Pissarro . . . facing page 25

THE TOPMOST APPLE an original woodcut from the Vale edition of “Daphnis and Chloe”

designed and engraved on the wood by Charles Shannon . . . facing page 27

THE LOTOS-EATERS ❧ a reproduction of a pen drawing by Reginald Savage . . . facing page 29

Ballantyne Press Colophon by Charles Ricketts . . . facing page [33]

❧ Literary Contents

DANÆ by T. Sturge Moore . . . 1

A NOTE ON GUSTAVE MOREAU by Charles R. Sturt [aka Charles Ricketts] . . . 10

Initial by Charles Ricketts. . . 10

SOME SHADOWS OF A THOUGHT by T. Sturge Moore . . . 17

SONNET AFTER RONSARD by T. Sturge Moore . . . 17

THE PIMPERNEL by T. Sturge Moore . . . 18

ENFANCE (after Rimbaud) by T. Sturge Moore . . . 19

THROUGH A CHILD’S EYES by T. Sturge Moore . . . 19

CHORUS OF GREEK GIRLS by T. Sturge Moore . . . 20

Tailpiece by T. Sturge Moore. . . 20

GARTH WILKINSON by John

Gray . . . 21

Initial by Charles Ricketts. . . 21

OLD KITTY by T. Sturge Moore . . . 27

Initial by Charles Ricketts. . . 27

A HYMN TRANSLATED FROM THE ITALIAN OF ST FRANCIS OF

ASSISI

by JOHN GRAY . . . 31

Three full page illustrations marked above

with a device ❧ have been reproduced by

Messrs. Walker and Boutall.

PERSONAL NOTE

“Poems Dramatic and Lyrical” The Plate

facing page 200 and appearing to illustrate

the poem “The Prodigal (after Albert

Dürer)” was done as an illustration to a

different poem by Lord De Tabley on the

same subject “The Prodigal” Page 189 “Re-

hearsals.” Through inadvertence no men-

tion was made of this mistake in the second

edition of “Poems Dramatic and Lyrical.”

DANAË.

Still, brilliant with bright brass, the tower derides

The sun’s gold shafts ; which strike and on all sides,

Like ridicule-lit laughter, spread ; and some

In bravery bend back whence they have come,

And try their strength with those that come direct,

With first impetuous potency unchecked,

From the god’s bow. For this the heat is great

O’er all the land of Argolis of late.

The king, Acrisius, hopes his tower may prove

Impregnable to liquid light and love

Rolled round it in a golden ocean-tide

Whose ebb is a June night : and so all dried

And dusty have the ways become ; the fields,

They wind among, with grain a rich soil yields

Should glow, not thus discover to the eye,

Between scant straws, their crops, what black cracks lie

And lengthen snake-like on baked brittle earth.

Nor dewed nor girlish comes the Dawn, a birth

Militant ; not a sole dwarfed hare-bell dares

To laugh : Night’s tearless glitter naught repairs.

Old Inachus scarce finds the strength to stretch

On his hot bed—stirs like a fevered wretch,

And limps round stones—so feebly seaward creeps.

While in the tower-top small Danae sleeps,

Unconscious how a god close, closer steals

Across her painted prison-floor, nor feels

His burning kiss the hand he reaches first.

She sleeps half-swooned: with sweat her brow has burst;

Pale lips apart show teeth like maids in bower,

Nor past them has her sweet breath stirred this hour.

Leaves lap and overlap, and trees ; the lily,

Deep-delled and fragile, grows up very stilly,

Decked with bead-bells adroop, yet so abashed,

She sees but couch-moss by rill-frolic splashed.

So silken shade and shawls of varied hue

Hid Danaë’s limbs which whiter daily grew;

And nothing saw she, save her room’s few things,

Beside the well-conned window-view; and brings

Each year no increase to her life’s thin store

Of sights—the only one not known before

A larger loveliness, that might be found

By searching the great mirror’s polished round :

Which had advent so imperceptible

It dwelt unnoticed there ; although, whimful,

She loved to see—no soil of levity

1 In

In her fresh silent mind—in nudity,

No flush-faced shame dared hinder to enjoy,

Her beauty—purely with no least alloy

Of vanity, since she had never seen

Eyes like to those which modest maidens screen

Themselves from, neither knew that any girls

There were less fair than she, or who wore curls

Less copious or of poorer purple sheen

On lustre-lacking black. Oft would she lean

As through a thunder-rain, while combing it,

Nor then alone before her mirror sit;

For when—cool after washing with well-water,

Nurse daily stooping up the steep stair brought her—

She gravely sat to musingly commune

With her companion-self a June forenoon,

To gain a smile’s return sometimes she smiled.

Since off her nurse’s knee at first, beguiled,

When little, by the bright resemblance to

Her young glad life, she tottered towards the new-

Perceived child, whose fresh rosy limbs resembled

Eros’ own in deep-dimpled mould, and trembled

Like cress-framed skies gladdened to recognise

Another blue,—deception friendly-wise

Lingered, though she no longer patted, pleased

To meet a pud like hers, and, seized

With love, put out her lips to join the lips

Out-thrust to them: no Years’ hand quite down-strips

The veil with child-dreams broidered ; in her head

Still someway separate existence led

The twin, and not so much more silent, sister

With her up-grown. Not once had she yet missed her,

As o’er their earliest chubby limbs had come

A gradual change, a whimsical, winsome

Awkwardness peeping out till plumpness went :

O’er salient points a certain tightness lent

A peevish pinched appearance; in sight too

Their shoulder-blades moved looselier ; a new

Sly meagreness had crept o’er them ; as shoots,

They sprouted up to taller growth ; like roots

Sent down into dark mould, grew whiter daily.

Strange inner effervescence sparkled gaily

Out through their eyes. The undecided place

Of budding breasts, dissimulating grace

As March flakes feign the snowdrop’s calm, shows forms

Hazy like mushrooms when the night-time warms,

That globe and gleam, yet leave the stars in doubt

If on the dewy slopes they shift about.

2 When

When moulds the potter on his whirling wheel

Dumb clay, a hint of final curves will steal

From clever hands in sapience sure ; just so

Quaint querulous suggestions of a flow

Of contour simpler, more capacious, slips

From God’s thumb when he moulds a woman’s hips.

Her thighs will lengthen faster than they round,

Till their delightful devious line be found.

The heels, too narrow, of the little feet

Will give her steps a wayward wav’ring sweet.

As when, unpropped, the heavy dahlias lean,

Her head nods, nods. A mere caged white-mouse, seen

Through close-strung wires, will writhe its sleek length high,

And hold with pinky paws, and seem to sigh

As, sniffing tainted air, it seeks a vent

From prison ; and then scurries back, as bent

On finding in the oft-searched farther end

Some small escape ; and, since its birth there penned,

Yet lives on, never losing childish hope

Somehow eventually its sense may cope

With most perplexing life-imprisonment:

Thus Danaë, with like hopeful discontent,

Led to and fro her white shape in her life’s

Wall-hampered home ; and still this useless strife’s

Fatigue can barely disappoint a mind

So scantly versed in freedom, or unblind

To fate’s fell force eyes closed by charity

To real and might-be sights’ disparity.

Now, like whole fallen statues on old lawns,

Deep puzzles for the country-minded fauns

Who peep, the sisters sleep. While mimic sun

Up one outstretched arm, cautious, crawls, up one

Real sun-lips yearn, aquiver yet to scare,

So lose, their prize; who Zeus is well aware

Lies not apurpose in his path. From fear,

He e’en forbids the swallows twitter near.

For daily—when, bold grown, some hour entered

In at her casement high, he has e’en dared

Come close up to the tall embroid’ring frame—

Just as his fingers set her wools aflame,

She started up to move more in the shade ;

Still on he crept, and still she was afraid

To feel his touch ; so his light widened, till

Was left, except beneath the window-sill,

No shade ; there crouched she in the broad’ning belt

And watched the crimson of his last rays melt.

3 She

She liked to see and dodge him round the room,

Which was great fun ; he gone, all grew to gloom.

’Twas then of old her nurse would lift her where

She might well watch old darkness overbear

The youthful light whom all things plead for—sheep

Who bleat and lowing herds and, half asleep,

Birds, ever loath to note how day’s cup fills

With joy ; and stables, then, and woods and hills

Hush up ; nymphs, centaurs, folk with tails and horns,

Settle themselves in nooks near lulling bourns.

Then, floated to her head, came children’s chatter,

And she, it may be, startled by such clatter,

Would let her eyes droop down to dark’ning earth,

And watch them playing in their noisy mirth.

Perchance they, quarrelling, fell by the ears

For some small sudden play-chance ; then her tears

Ran fast, and such upheaving sobs would rend

Her slight frail frame as would not know an end,

Till she was tucked up in her neat white bed;

When would commence a coursing through her head

Of wond’ring queries, how their love and hate

Were roused, till stunned by sleep importunate.

So tall and slender later on she grew

That, planted on a footstool, she could view

The many lanes that led up through the fields,

In which—towards where a deeper shadow shields

First-fallen leaves, while the withdrawing sky

Pities feet slow in dust—two wandered by

Who late, in most reposeful country life,

Have found unrest and something of the strife

Of hearts, which cruel Eros loves to see.

What balm was theirs to soothe? as peacefully

They went, arm-linked, what made them so content

In silence thus to walk, together leant?

Boundless and vague, deep wishes welled in her;

Wide grew her eyes ; and through the echoing air

A memory—sad, single, precious scrap

Of love-lore—sang,—while round her eyes she’ld wrap

Her hair to blind them,—what she once had heard

A poor girl sing:—so sorrow’s tide recurred.

“Haste thee, haste thee to my arms;

Emptily

Hang they, voided of thy charms.

Marry me!”

4 Like

Like some sick leaf, a fierce wind hunts alone

Proving its gold rings false on stem and stone,

This feather from Love’s wing to Danaë blew.

Ignorant of his name was she, nor knew

Aught of his antic gambols with the maids,

As, when she questions, her old nurse upbraids.

For the crook’d crone has had instruction strict,

To see how ’tis she lets herself be tricked

To talk of love, men’s manners, women’s wiles;

Therefore, well-taught how innocence beguiles

The weak lips to unwise discovery,

Has bound her tongue to stay most silently

Within her mouth, till grown so taciturn

Her gossip’s-heart has learnt to never yearn

For converse, though she truly loves the child—

Who, the song sung, let loose her hair and smiled.

Soon lifted eyes were tempted off anew

Among the stars, those eyes most simply true,

Thought but small holes drilled through a roof, the sky:

What should she know of gods or destiny,

Of Zeus, sky-king, or Kypris and her doves ?

What was to tell of them except their loves ?

No prayer she said ; nor had she learnt to muse

How life’s a dream, or of the soul that sues

For speech from out the frigid lips of fate ;

Nor knew she aught of the omniscience great,

Or how her small mind some w r ould father so.

Yet there of mystery was what she might know,

Who had found tokens in her tiny round,

That little limit of her life was ground

Sufficient for a larger lovelier growth,

Attaching meanings to the light: how loath

It was to shine, she thought, by such small holes,

When the vast void, through which the day’s sun rolls,

It could flood, driving forth the sad dark sea

Of night ; yet could not clothe her sweet fancy

In words. Since her vocabulary small,

Drafted from out her nurse’s, could not call

Her thoughts by name, she smiled them to her side,

A mind’s eye-harvest sweeter, not more wide,

Than filled a miser barrel’s critic-round

Of sky-blue. Disentangled and unwound,

Her idea of the home of blessedness,

Whence stars shone, could not bind such vague distress

As bosky gardens feed in glow-worm eyes,

Peering through gloom, whence if a tuft arise,

’Tis shown by light which haunts them like a ghost,

5 Those

Those few tufts just the things her life loves most.

Her swoon’s dream is, that she, transported thither,

Loves, wanders, close-companioned, near a river;

Un-characterized the friend, whose arms embrace her

Slow pacing down a path star-daisies trace there.

Meanwhile, at home and far from such a place,

The sun, stretched o’er her, showers on her face

Kisses, that meet no blush, nor dint the snow :

Thus summer wastes, for all the high peaks know.

Her life, love-stinted over-much,—for, save

Her nurse, no one to love, or that could crave

Her love, she knew—had let heart-worship fall

Portioned to dead things—as some silken shawl,

That she would hold against her cheek, kiss it,

Space out, and bid its folds her fancy fit;

Till thus an afternoon was whiled away,

Fondling its foolish yards. Another day

Brought flowers that came in pitchers, or a load

Plumping an apron, or else singly stowed

In with the butter, sprinkled o’er the fruit,

Or making dewy nests for eggs. First mute

For gladness, next with clapping hands on feet

That totter with impatience, see her greet

With airy kisses little friends—small eyes

Glorious with gazing on the liberal skies,

Sent by the open-hearted folk who wonder

“How fares small prisoner princess penned up yonder?”

Next in her favour stood some exile shells—

Large lips, agape with wonder-working spells

Which the ear hearing, vainly the mind strove

To dredge a meaning from. So, oft she wove

With nets and toils of hair one to her ear,

Deep in that cushion sunk she found most dear,

Her feet out-thrust on th’ mat most to her mind

Because, ’mid green waved lines, it showed a kind

Of ready needle-pictured likeness to

Her whole bare body, over which there flew

Much smaller portraits of herself, as she

Is to her mind brought back by memory.

As thus she sits, her treasures piled about,

Words foil her ears that, in a sailor’s, shout—

“ Aphrodite,

Each wave mothers

Thine almighty

Form; uncovers

It each breeze,

6 Thee

Thee to please,

And to tease

All thy lovers.”

Sun down, the thick swoon from her body lifted:

So, with trailed wings, is some slow eagle shifted

By fed uneasiness. A vivid grey

Blinded her ; night’s cold coming drove away

Her sense once more : she slept, while pain did drum

With muffled hands her temples dull and numb.

Confusedly capricious dreams have wrung

Those tones from her with which that girl had sung,

While, like sea-chants climb twisted stairs to bed,

Male words through dainty doors have reached her head.

And from that night, as some fond woman sits

Beside her love, she with the sun, when its

First matin wealth plunged on her shoulder, till,

Having bathed and blessed her, it slipped o’er the sill.

So changed she was, life wholly seemed becalmed.

All summer-wonts, too, lingered unalarmed ;

For the fierce forest-fires of autumn sped

Slower, glowed larger with less hectic red,

To equal the great glow of July gold.

It seemed that ne’er, they fallen low, their cold

White ashes would be huddling round the farms

And choking in at doors. On false alarms

Birds flew to sea: still the bland weather stayed;

Oft, too, the roof of clouds, rent through or frayed,

On winter’s lap let warm boons drop, to cheer

Men’s hearts. Such fondling had the tower dear,

Where each and all those gleams are welcomed like

A lover’s letter.

When young breezes strike

A tune, and Spring, spry wanton, comes, her nurse

Looks puzzled, makes her pinched up lips to purse

And her eyes blink, bewildered, at the maid,

Who goldly glimmers in the gleam,—afraid

They have not told her of the thing aright.

She falls to rubbing them with all her might;

For, what! a woman with child, no maid, she saw

Sit where the maid had sat a year before.

She fain had got to scolding but delayed,

So clear the eyes she met; and then she prayed

She might be much mistaken, and still knew

She was not; such a queer knot how undo?

For she had ne’er an instant left the tower,

7 Scarcely

Scarcely the room for much more than an hour.

Who could have done this thing ? O ye great gods!

Walls, locks, and all man’s cares make little odds

To you, when once ye have a mind a thing

Shall be: well may a man stare, whistle, sing,

And blow upon his nails, if ye have entered

With him a race on which perhaps had centered

Dozens of spangled hopes—or life ; ’tis one,

And the race won before ’tis ever run.

So, when a boy-child came to light, her father

Had to be told he was grandsire; though rather

His ears had heard his daughter, pined away

In prison lone, was gone to swell, that day,

The dim ranks of his dead, who wait in earth’s

Strongholds, all kings, or issue by their births

Of kings, or queens, or queenly-motheréd.

He felt as though an ire-forged bolt o’erhead

Was hurtling with intention, like the disc

Young men in rivalry hurl, whereby great risk

Is run by such as watch : so, all at once,

Fear, worst midwife for action, did ensconce

Herself within the unheroic head

Of king Acrisius. Thus, straightway, from bed

They drag poor Danaë, waked to foreign sights:—

The dead night bruised and wounded by torch-lights;

Rooms loud with jest, where girls dance wagers bare,

Where wine-cups crashing wound no thrifty care ;

Close-huddled houses, lanes whence unfed howls

Of unowned dogs disturb. All, which befouls

A town, behind at length is left; the heels

Of the guard, arm-weighted, clog in clay; she feels

A fresh wet wind, and hears the weltering wash

Of waters ; then is lifted up, feet splash,

And, when, set down again, she raised her eyes,

She saw the simple stars, that in surprise

Were crowded close together, and she, dazed,

Lay like a fallen wing’d-thing ; while the raised

Male voices dwindled till the dipping oars

Could make their rhythm felt. Then low-banked shores

Parade black blotted groups of ilex-trees

(The chest was hewn from such stout trunks as these,

She floats in)—pyramids processional

Of night-obliterated leaves, ranged tall

Like mutes ; while, like white lines of silent tombs,

On either side behind the night-mist glooms;

And like some broken-hearted woman bent,

That heaves her hair with sobs,—as on she went—

8 A willow

A willow kneels among them here and there.

The water wakes and louder wails to her—

Nay, wails with old choked sorrows now no more:

Triumphant shouts, borne from a sonorous shore,

Break on her ears; and happy hurried airs

Make haste—lest she, when shaken unawares

On Aphrodite’s cradle-rockers, fear—

To whisper good-will tidings in her ear.

A boat had laboured with the chest in tow:

Dull wooden sounds faint; homeward it does go.

All this long time she held her baby tight,

And stared the poor stars out with all her might:

Now, looking down, she sees his waking eyes

Claim—as his curled gold locks the sun—the skies

In parentage. She dandles in the air

The pretty wanton; who then clips her hair

In fist-fulls, crows, and o’er her shoulder spies

Hermes with Zephyrs wing’d like dragon-flies,

Who, watchful how such frolic crew behaves,

Pilots them o’er blue inly-varied waves.

So many blues, yet each unlike the other,

Grow all greens, when a Zephyr flies his brother.

In vain the gallant Hermes doffs his hat;

For jealous Zeus gave strict commandment, that

His messenger should do his duty, dight

In form impalpable to mortal sight:

Yet, well seen of the baby demi-god,

He from the merry knave receives a nod

Now and again. The far grey tower stands

Against the north, as left by Night’s rash hands

On brilliant-breasted Dawn a bruise of blue,

To fade as her hale pulse revives anew.

This god-freed, god-loved woman hail aloud,

Breezes ! your king the sun mounts o’er a cloud.

Swell your big-chested conchs, strain trumpet-throats;

He hears and knows you, though she little notes.

Still the sad silent home, that distance veils,

Each moment bears behind, as on she sails

To new life, lit with large affinities ;

And for her son Perseus what destinies

Await, beyond the sounding straits that sunder

Dead past from future life! Still sailing under

The blood-thick blue, at length Seriphos, reared

Above a million moving waves, appeared.

T. STURGE MOORE

9

A NOTE ON GUSTAVE MOREAU.

IT is at first necessary to separate some of Gustave Moreau’s

characteristics from the loose admiration they have brought

about. A dim recognition of his excellence has been caught

by the current of opinion, for it has root in an old longing,

that touch of nostalgic unrest we have, wrapped among the

habits and renunciations forming our ways—in that truly

spiritual leaven, to push circumstances at times beyond their common scope,

in our craving for manna, at least, upon the alien sand. But whatever in the

present finds self-expression in his work has, after all, gathered there into

some special thing, lifted out and beyond the capacities of his surroundings ;

and the existence of so complete, so finished an art utterance amid the

unkind haste of to-day becomes strange if one forgets for the moment how

irresistible is all art growth, whatever may be its everyday conditions, how

separate is always its real achievement, contemporary opinion concerning it

being merely a matter of accident. If an air of pallour in its fruition marks

this obstinacy in growth, art, nevertheless, has become gifted by the effort

with a new sense of beauty, or one, that, for its degree, seems different from

the older sense that was only enamoured of health; the temptation to see

things by this newer knowledge will in part explain the fascinated return

of the art mind to the past, for we watch it in perspective, conscious of

its calm (tinged possibly with weariness), through an atmosphere coloured

by the atoms of our many experiences and ways of thought,—through a

subtile apperception of our weakness, become a subject also of interest in our

half-longing return to that past, so divine in shoulder, so youthful in its

immunity from failure. Yet such retrospective curiosity may prove new

only for its present degree; one may be tempted to imagine it part of all

art effort, in revolt from the immediate, were not opposition too partial, too

limited in work, too separate from the grave sense of growth and expansion,

that is art, to be of serious value as suggestion.

In a characteristic phrase Gautier once sketched this desire to possess

the past with the added charm it now has for us; he ends with a mention

of Flaubert as incurable in this matter, and Flaubert’s correspondence teems

with revealing touches evoked at the actual contact with facts meaningless

to others as mere loose rubble or dust of the past, but, to his gift of divina-

tion, redolent of rare sensations, intense, even to the verge of awe; so that

a stray aroma of rose or balm from the rent in some sepulchre conjured

up to him the shapes, the passions of a world whose being, passed into his

books, yields the essence of that magic he felt so keenly, with much, to the

reader, of that sunset glamour, of nostalgia.

This love of forgotten things joined to Flaubert’s admiration for Moreau’s

pictures, has led to obvious comparison between the two artists, though a

slight pause in judgment might show how false all such comparisons

must be. With Flaubert that haunting force was vivid to create the

real light of a possible past with each detail cast out into clearness, or

troubled only by the emotions of his actors to whom these realities become

10 strange

strange at times, as so many things must have been in those periods of

unquestioning expression.

With the painter the case is all different, for Gustave Moreau remains a

lover of mythical half-light, light not yet lost in the encroaching night nor

absorbed by the approach of day, of emotions in a morning twilight when

Cerberus, forgetting his chain, may wander beside dark pools, near ghostly

reeds ; for time, a thing so present with the author, has become suspended

to the moment when neither ship nor god need be gone yet; and nothing

is importunate with its reality. We are in a world only of mid-distances,

bounded by low-breathing seas, with littoral towns against the sky ; in a

place where the passing of a bird, for its suddenness, is an emotion. Here

are flowers with strings of crystals made sharp in hue and texture, for

appeal to our visual-touch, to forbid the conviction that all this may be

mirage, that his mystic creatures must soon vanish with the perfumes

ceasing to breathe in those censers, and leave with us but a handful of

aromatic dust, the dust of hair, dust of laurel leaf, and the glimmer in

the grey of forgotten things ; as, in ancient urns, we find a tarnished coin

among the faded ash, a gilded siren as symbol of some story it is unable to

recall. Thus all resemblance to Flaubert lies only in the compass of their

hatred for the commonplace.

In a book of impressions on art (Certains) Monsieur Huysmans lays too

great stress on the element of contrast in some designs Gustave Moreau

executed toward the illustration of La Fontaine. With him, for the

sake of critical emphasis, much of the painter’s work becomes too para-

doxical in means not to be somewhat mechanical. His descriptions else-

where of other pictures, as well as this note, abound, it is true, with acuteness

of feeling; they have unfortunately over-influenced subsequent criticisms

more general in tone. It is through these, possibly, that Monsieur Huysmans’

statements become annoying ; nevertheless, in justification of him, Gustave

Moreau’s consent to become involved in such a task was strange it must

be admitted, in some degree unlucky, none of the fables suggesting a subject

fitted to his great, but entirely lyrical scope. Animals under unaccustomed

conditions—at the best, persons sententious on manners—lay outside the

world of his vision ; not to seem purposeless, they had to be clothed with

a new air of unreality, to move in the flora and cloud of a fairyland empty

of those gracious figures that meet him there half-way, for his great know-

ledge of them. The number of these drawings became troublesome, and,

despite the beauty of many, one turned with a sense of relief to other works

where his handling, with its virile nervousness, moved with more freedom ;

where motives dear to him made quick his hand and pleasured his vision,

realising those instants so suggestive, when the fury of an act has passed

or gathers into new purpose beneath skies flushed by an aftermath of sun

that recall for their touches of orange and bands of brooding purple these

words, “quelles violettes frondaisons vont descendre?”—words so expressive

of that hush in nature, become strange in expectation of some countersign

pregnant for the future.

It is against a sky like this an all-persuasive figure moves away, the

11 head

head of Orpheus lies between her hands, and one scarcely knows if her

fastidious dress, decked with so many outlandish things, has been clasped

to her wrists and chaste throat in real innocence of the burden she holds

mystically ; but this hint of sentiment is too slight, too fugitive in the

picture to become heavy or morbid. Enigmatic forms in contemplation

move through other works; the Salomé, for instance, where she is already

conscious of the doom between her and this face whose nimbus grows in

the declining daylight, as the dawn might grow on a blind when the lamp

goes out ; the sky centres to a blood-like spot, half cloud, half garment of

the executioner passing beyond, a fearful messenger to God. It is a spot

of blood like this, in the shape of a little cloud above the sea—clasping in

its most secret blue the future Rhodes,—that gives to the picture of Helen

an undercurrent of doom to which the actors in it are half or all indifferent.

This picture, unless my memory deceives me as to its execution, confirms

his tendencies in one effort whose elements of beauty had haunted him

before, but, till then, not achieved so supreme an aspect. From the brow

of a cliff that is a town Helen moves, pedestailed on broken colours that

creep upward across her dress in a succession of amulets and fronds, to

twine and twist into frail leaves, with stray spilths of ruby towards the

chalice of a blossom she holds near her face whose flesh is luminous against

the samite sky. And below her rainbow garments in which the colours of

the clouds and earth are married, so grouped and so clasped together to form

part of the ramparts, are the wan faces and faded hands of those who, for

her sake, have been won to Death ; and their mouths smile yet, for, at the

moment of death, when the lips grow wreathed, and the eyes profound,

they have sunk into the arrested sleep of some Elysian place, to wait, with

“that touch of irony that must have been Persephone’s,” their return to

life, or the prolonging of their rest into this hour plucked from out of

time. Thus, leaves of laurel and gathered buds are still in their hands,

or the swords whose edge was fashioned against themselves. And that

silent brotherhood, this buttress to the house that must not stand, is

clothed with wreaths and incense haze, as if about a mystic sacrifice for

which nothing can be too good, too strong, nothing too fair. What touch

of foreboding may linger here smoulders, away in the cloud and horizon,

for the artist does not tell if she, who found nothing but praise between

the lips of man, and praise gazing from his eyes, is capable of happiness

even ; if hand over hand she is about to leave this place whose nights and

days have become bitter with the ache of love and grief ; if this phantom

knows herself to be more than woman, a symbol in some divine semblance,

and would exult could she know laughter or tears. In this picture Baude-

laire’s hymn to beauty has become visible, but purged of whatever, through

the limitations of a language, may be touched by posture, epigram ; and

her eyes know they have no need to see.

Moreau has shown her elsewhere (in a small water-colour drawing,

L’Enlèvement) under the closer light of actuality, imaginative actuality, but

wrapped always in her separateness from blame. She leans softly in an

amorous bend against Paris, on the foppery of whose Phrygian dress the

12 artist

artist has dwelt with minutest care, making it a delicate setting to her half-

nakedness ; the flight of their chariot drawn by willing horses is past a

landscape of crags, the sky burns its passion out above the sea becoming

black ; and in the blue, among the rocks, the Dioscuri still on horseback

are accomplices. The artist has abandoned the strenuous finish in work-

manship of his masterpiece, to become rapid of hand in the pencilling of

cloud and form, and by an afterthought, half poetic intuition, half sheer

pleasure in colour, he has added a bird dipped in crimson as a stray envoy

of Venus, accentuating by its aerial flight the buoyancy of the lines in the

picture; for he is always lucky in such suggestive touches, and his shrewd

sense of literary suggestion in painting never fails him.

Literature, by gradual process of appeal to the imagination, the sense of

growth through which it brings things about, may show any incident,

implying its degree of import in a hundred ways, conveying a sensation all

pleasurably subtil, where the eye, called to view only a result, might find

mere fact in illustration. Take the sonnet by Ronsard, whose subject at

first sight would appear almost pictorial with its implied winter light and

mirror gleam in which Helen, become old and wrinkled, muses sadly on

her vanished beauty. Imagine it translated in painting with the implied

splendour once hers only dimly shadowed forth, how uncertain would be

the result dramatically ; outside the field of words her momentary bitterness,

or harlot’s petulant frivolity, or whatever might make her more real to us,

would become a record only of that mood.

In an early phase of his art one great painter has succeeded in painted

narrative. When taking up the tangled threads of a remote legend, Rossetti

has cast together under the search-light of an intense and generous imagina-

tion, not only the incidents of a story interwoven with new poetic additions

and suggestions, but the almost digressive element of personal predilec-

tions (predilections with a touch of surprise, discovery) in circumstances

and counter-incidents ; shrinking from no complexity for his certainty of

grasp in close-knit design and handling whose expressiveness never flagged.

With Gustave Moreau, the dramatic element is entirely evocative; one of

undoubted intensity, but under lyrical and ornamental conditions his

creatures would become troubled and shadowy indeed ; if brought face to

face with facts and real passions, they would swoon upon themselves,

called back by some sudden Lethean murmur, or inner portent ; their

realities are confined to a few fair things fostered in the shadow of palaces

and ravines, in the mists from rivers, where light, water and air have

become resolved into the cold limpid colours of the topaz. The evidence

of separate life, of the without, so hotly insisted on by Rossetti, is reduced

to the half-fascinated wheeling, the circular-flight of a bird, fraught at

times with great realistic point, as in the shrieking seamew that flashes

across the fall of Sappho from the rocks. His choice is of half-mystic

things, things of ritual ; in this and his partiality for certain colour har-

monies will be found his greatest limitation ; yet in this lies also a sense

of voluptuous melancholy so attractive to the spectator if unbiassed by the

conventions of French and English habits.

13 The

The danger is great by over-emphasis to deprive a living thing in art,

with its variety and many phases, of lifelikeness and freedom, as bad

painters deprive their subject of all “undulation” by a rule of thumb they

are pleased to consider completeness of rendering. The art of Gustave

Moreau is living, varied and, like all living things, capable of that counter-

change in virtue or personal force that is allowed even to divisions in nature,

through force of will, desire, or in mere reaction and fatigue.

Therefore among his pictures some will be found very different in temper,

pictures impetuous in dramatic feeling, as the Diomède dévoré par ses chevaux,

in which the feet of the tortured man bend back with suffering, and his whole

body is borne from the ground in its fall by a vehement gesture of cursing

and the rush of his horses ; the Phaéton, L’Hydre de Lerne, Le Retour

d’Ulysse, the Sapho expirante. But these are largely a reaction from too

long a brooding in his charmed habitual mood, and in a score of things they

have a sense of nervous refinement, an implied languor in their rage, that

groups them in his enigmatic world of terrible silences. Yet it is odd, not

a little illustrative of the real lack of artistic activity now prevalent, that

such works should be the only pictures that recall the autocratic, the over-

bearing impetuosity of Delacroix, produced by one whose temperament might

well have been averse to this frenzy.

To-day accusations of plagiarism are broadcast against very ordinary per-

formances even, lest, in the hurry, one man should fortunately escape. With

this great artist none of these accusations is reconcileable to the authentic

stamp of his personality, drifting as they do between Mantegna, Turner,

Blake! or vaguely the Italian masters.

Such questions are hopeless, such similitudes would have puzzled King

Solomon himself; had it been on the subject of art similitudes that the

bright queen wished to be enlightened, his wisdom might—who knows?—

have been tasked beyond the powers of his divining ring, and that amulet

of his, for the control of “loose spirits in their places and the very insects

whose ways are in the sand.”

An influence of Chasseriau has been put forward ; an early picture,

belonging, like the Jason et Médée, to a period of transition (of youthful

ingenuity), will largely explain this critical impression, for Moreau inscribes

it, in a dedication near the frame, to the memory of this dead artist. But

the youth (in Le Jeune Homme et La Mort) who crowns himself on the

threshold of Death’s house, a handful of plucked flowers in his hand, is far

removed in purpose from anything seen hitherto in French art, though some

accents to the drawing remind one that Gustave Moreau was once the

winner of a now forgotten Prix de Rome ; and there is a difference of more

than two art centuries between his shape and the passive figure of Death,

whose work of destruction is left to an Anteros, too young, extinguishing a

torch tricked with nightshade.

It might be difficult to account for so many opinions concerning the

genesis of his pictures, did one not know the tendency in most people to

discover similitudes through a lack of some genuine test to their impressions.

With the unaccustomed passer, trailing his feet about a gallery of antiques,

14 all

all remain alike as unaccountable things in stone ; this casts an oblique

light into much criticism that, before work fastidious in its expression,

jealous of its point of view, will recognise the uniform stamp of refinement

on imitation, and, till the word be found by others, expressing our indebted-

ness for this new knowledge, knows but the word Plagiarism, so smooth

to the ears of indifference.

There are many unusual influences blent in the fabric of his creations,

influences of many moods and memories, playing on them, drawing expres-

sion where they strike in some delightful iridescence of tone and thought.

None would resolve the beauty of a crystal into known gases, in some

arrangement of angles ; and art, unlike natural products, besides its

elements of composition, contains some of the divine initial force that brings

it about in emanation, as it were, whose quality calls force to force. To

experience the sense of fascination holding him at work; for its sake, to com-

bine, to hoard, towards that season when this end is achieved, weaving positive

time and emotions into it, must be the only way of enjoying work like his, cer-

tainly of no use to persons of acquired feelings, to whom all new effort remains

objectionable and obscure. Yet the penetration of this obscurity is to find it

enchanted with “ spirit eyes”; this strangeness outside our immediate expe-

rience becomes a simple possession for to-morrow, winding as a stirring

freshness might among the leaves, in that which each day brings of bud to

bloom. In the wrack of the past (“ that approximate eternity certainly

ours ”) this artist has plunged, to bring with his return the evocative chime

on chime of a new thing or message. One sentence of De Guérin’s recalls

to my mind not only this, his great gift, but, very curiously, the possible

aspect of a picture by him ; the lines describe a young fisherman whose

body, for a moment swayed against the sky, plunges among the trouble of

the waters, to return, his head sometimes radiant with wreaths.

His gift of renewing our interest in old, outworn subjects is revealed in many

works—Moïse exposé sur le Nil, La naissance de Vénus, David. It would be

difficult to imagine a more noble picture than this last for invention, yet

more intimate, with all its splendour of detail, though, to some, the

handling might seem thin, for the colour scheme growing into an evening

silver. Each touch is indeed fortunate, from the waning of the incense to

the faded lily David holds in guise of sceptre; this hush over all seems

the soul of the dying man become mystery and colour, wherein a lamp

burns whiter every instant; as each cloud sinks, the weight of a crown

bends the royal head towards the hands whose grasp is loose ; between the

pillars with their symbols moulded in gold, against the marge of the horizon,

a bird sings. But, at the foot of the throne, nestling like a dove upon a

shrine, its limbs and body folded among the kingly vestments, is a visible

spirit of God, clothed with the androgynous garments of the angels ; the

face has, with its awful joy, some suggestion of a Christ at the age when he

disputed with the Doctors, and, by a touch of the imagination really inspired,

the fingers of this apparition pass across the harp whose strings the king

can no longer know.

Hantise is the word by which a new critic has conveyed the secret note

15 whose

whose obsession strikes so weird a sweetness through the work of Gustave

Moreau. And his art is verily haunted by that fantastic and goading

spirit of perfection, who dwells always in the centremost chamber of the

past ; but his personal way of bringing this near to others remains his

grave achievement. In a train of delicate purposes he passes a sponge across

the lost hues of some ancient picture of passion, making it visible, not

only for that moment but for many moments of return; he makes actual

that which must be too frequently but the echo of a remote recollection,

nostalgia, for lack of a better word, an emotion naturally decried of those

passers, whose bread is the wreck and refuse from the sea of circumstance,

and to whom this strange activity seems hectic, even dangerous.

CHARLES R. STURT

16

SOME SHADOWS OF A THOUGHT.

Now, like the silence at the heart of song,

Art mars to make, hope’s bow on life’s rain-fall;

A gilly-flower, she tops the garden-wall

And shames the scare-crow weeds which, stunted, throng

In peace their paddock; she, the seed of wrong,

Maketh life’s beauty’s presence keen; a rope

Of seven sinful withes, she wards the slope

Which pilgrims to perfection climb along.

Her fittest likeness is a looking-glass :

To seize on beauty as life’s pageants pass

She coldly, with a crystal ease, is skilled.

She deigns nor toil nor in the work-shed swelt

And strain ; yet must gross metals glow and melt

Before her latest freak of form be filled.

SONNET DE RONSARD POUR HELENE. LIVRE II., NOS. XLII.

When you, quite old, by night with candles, well

Up to the fire, wind skeins or spin, you’ll keep

Crooning my verse and, plunged in wonder deep,

Say “ Ronsard fames days when I was a belle.”

And you will have no servant hearing tell

Such news, though bowed with labour half-asleep,

But shall, at sound of Ronsard, waking leap,

Blessing your name by praise made durable.

I, under ground and with nor bones nor thew,

A shade shall rest near shadow myrtles; you

Will by the hearth, old, crouching, scarce be blithe,

My love, your proud disdain for constant sorrows.

Live now, believe me, wait for no to-morrows;

Pluck even to-day the roses of your life.

17

THE PIMPERNEL.

The little pink pimpernel,

That border the way to the well,

They saw, they knew, and gazed their fill,

Though sorely against their will

Tied by their stalks to the earth;

And the angel who ruled o’er their birth

Forgot, it is said,

A tongue to each head,

So they had to keep dumb ;

But they all blushed red

Like the nail of a girly’s thumb,

When you bite it a bit

That a kiss may be

The healing of it.

And what did they see?

Why, from the well a woman all white

A woman all naked, fled out of sight!

18

SUGGESTED BY THE PROSE OF ARTHUR RIMBAUD “ENFANCE.”

Parentless, without court, and nobler far

In every land than gods in fables are,

Has azure and verdure insolently fair

For kingdom stretching forth till waves which bear

No vessels, breaking, name its shores by fame’s

Ferociously Greek, Slav, or Celtic names.

In forest-borders—dream’s own blossoms there

Like bells chime softly till they, opening, shine—

Is the girl, orange-lipped ; her knees she yields

Doubled to clear floods welling o’er the fields,

Nakedness shadowed, flecked, and clothed in fine

By rainbow-bands, the flora, and the sea,—

Such insolence and such immensity.

THROUGH A CHILD’S EYES.

Ladies, who there and back again still pace

On terraces close neighbouring the sea,

Fairies and giantesses. Vert-de-gris,

A foam of verdure billows round the place ;

Forbidding, proud, each woman-jewel’s grace

Stands upright on rich soil in shrubbery

Or tiny garden’s sun-nursed liberty—

Young mothers and grown sisters whose deep gaze

Far pilgrimages have with ‘by-gones’ filled,

Sultanas, princesses, tyrannical

In bearing and in costume how self-willed,

Little foreigners and folk amiable

Through mild unhappiness. Last, boredom’s part,

The chat’s hour of “dear body” and “dear heart.”

19

CHORUS OF GRECIAN GIRLS. (VASE E. 783. BM.)

We maidens are older than most sheep,

Though not so old as the rose-bush is;

We are only as pretty as that.

We are gay as the weather. Our minds are deep

Like wells, as any boy tells

By the blushes, he dares not kiss.

The hills are fond of our chat.

We dance and shake like ringing bells,

Till our hair tumbles out of our hoods.

Our feet are bare, our feet are bare ;

But we don’t care, we don’t care,

For the boys are away in the woods,

Hunting the boar or bear.

We pretend to fly

Up into the sky,

Jumping with both feet together,

Holding out like wings

Our sleeves and things.

Feeling as light as a feather,

We don’t wonder whether

The day is long

Or the night short,

Since all our thought,

Is but big as the song

Of a brown fussy bee,

And just fills the flower which we

Each call me.

T. STURGE MOORE.

20

GARTH WILKINSON.

JAMES JOHN GARTH WILKINSON, born so early as

January 1812, still lives; and still his tall strong frame

wears a memory of the robustness of his long youth. The

most of his life abnormally active, the harvest of it is little

“sensational.” For the physician sows seeds of which

others gather the fruit; an exponent of spiritual science

writes for obscurity (and who gives himself with passion to an exalted

materialism, as Emanuel Swedenborg’s, wraps a veil about obscurity itself);

the dilettante has his circle of literary friends and is like to pass with them.

Yet in the New Church Dr. Wilkinson has a great worth, a position

almost apostolic in its dignity ; the man of virtue and knowledge is noble

in spirit circles.

Dr. Wilkinson’s literary labour has been great. His are many of the

accepted translations of Swedenborg into English, and he has written much

commentatory of that seer’s system: works indeed only to be received as

ultimate by a New Churchman, but surely not the exclusive property of the

Swedenborgian in their ultimate value. Their titles speak, wanting only

the small knowledge of Swedenborg’s writings which is universal to explain

them, and indicate their purpose: Epidemic Man; The African and the

True Christian Religion his Magna Charta. Also derived from

Swedenborg, but infinitely expanded, is the marvellous book, not authorised

I think by the College of Surgeons, called The Human Body and its

Connexion with Man, laying down a new scientific method, purporting to

be a beginner’s book of physiology.

These facts merely interesting to a narrower interest.

“The book attracted the attention of Rossetti,” criticism will say, whenever

hunger drives it to Improvisations from the Spirit. The volume is

uncut, thickish; of the size known technically as 24mo. It contains one

hundred and nine poems. It is bound in cloth of a cold piercing green

colour. Its date is 1857.

The poems vary in length from eight verses to fourteen pages: their form

is in all cases rudimentary, without technical ingenuity; especially in the

rhymes. They are narrative and philosophical, the lyric character all but

absent. Some, the most virile and free, have abstractions for subject:

Newness, Gentleness, Uncertainty. Many are addressed to persons, to the

members of the writer’s family and circle, to W. M. Wilkinson, the writer

of the book upon Spirit-drawing, a dozen or so of them. Many again

describe the notable, in remotest symbolic terms; poets, philosophers and

scientific men: Poe, Turner, Hahnemann, Finden the engraver, Berzelius,

Chatterton, Tegnér, taken at random. High ethical and religious dicta are

hung, for the rest, upon a variety of topics, surgical, biblical, physiological,

political and religious; the object of the writer seeming to be to look at all

the world from the very original standpoint he was able to reach, as it lay

around him, radiating from his own heart and brain and soul.

Breadth, fearlessness and indifference give the first shock in the Im-

21 provisations.

provisations. These qualities perhaps the best excuse for the comparison

to Blake’s poems one sees inevitable; better than similarity of strange

epithet and symbol, derived from a common source, let us not say the

spiritual world, (at least yet) but disposition towards it.

Occasionally the impression, the mere vibration produced by the work as

literary composition, is like that produced by some of Wordsworth’s most

lyrical work, the Lucy poems a good instance: where doggerel will break

suddenly into a cry, so shrill and clear and passionate, that the doggerel

becomes an essential to the song’s worth: fusion of idea in Wilkinson

corresponding to fusion of emotion in Wordsworth.

A little extract from Madness will illustrate much at this point:

He lies down to sleep:

Cockatrices come,

Purring from the deep,

From the Demon home:

Purring cats of hell,

Mousing for the mad:

They have left their shell,

For a season glad.

And he dreams their dream:

’Tis a woven lie:

Providence’s stream

Runneth from on high:

They do ride the stream:

They are Kings of God:

And the sun world’s gleam

Issues from their nod.

In great honesty, quotations must not be made from the book except

with reference to subject. The injustice is best annulled by a further

quotation, on the understanding that these extracts from Madness and

Solitude are to represent two poles of expression (moderation has guided

the choice in each case):

I see it now: it lies upon the plain,

Like the big drops of summer’s pregnant rain,

And o’er the city hovers, in the breeze,

And windeth like a river through the trees.

The darkness doth espy it where it lies:

And the night loveth it thro’ many eyes:

And jewels of the morning come and play

Around the footsteps of its wintry way:

22 It

It is a shape in starry garments clad;

It is a joy whose feet are ever sad:

And in its hands it holds a book of light,

Whose leaves are anthems of creation’s height.

Here the element of imagination is sufficient : the cat serpents which

wait upon the mad, and the personification of solitude; but the pulse beats

low in these passages against the quick-following strokes of The Birth of

Adam, where brain and spirit are quick in every verse. Criticism of

Wilkinson will never need to lose itself in eulogy ; but certain summits in

the Improvisations are signal attainments of imagination : The Birth of

Adam among these, and in Patience the mighty image where the vaulted

back of the ass Christ rode into the State of God is become in heaven the

bridge that angels walk. A further point must be touched upon (for a chief

reason of respect to the poet, and others): Dr. Wilkinson’s assertion that

the poems were written by impression. To say no word on this subject

beyond what Dr. Wilkinson has said in the note at the end of Improvisa-

tions is the only way to escape the necessity of going back to radical

principles of sciences not yet fully orthodox.

“A theme,” says Dr. Wilkinson, describing his essays of writing from

Influx, “is chosen and written down.* So soon as this is done, the first

“impression upon the mind which succeeds the act of writing the title, is

“the beginning of the evolution of that theme; no matter how strange

“or alien the word or phrase may seem. That impression is written down

“and then another, and another until the piece is concluded.”

“However odd the introduction may be, I have always found it lead by

“an infallible instinct into the subject.”

“The depth of treatment is in strict proportion to the warmth of heart,

“elevation of mind, and purity of feeling existing at the time.”

“In placing reason and will in the second place, it is indispensable for

“man, whose highest present faculties these are, to be well assured what

“is put in the first place. Hence, Writing from an Influx which is really

“out (-side) of your Self, or so far within your Self as to amount to the

“same thing, is either a religion or a madness. In allowing your faculties

“to be directed to ends you know not of, there is only One Being to whom

“you dare entrust them: only the Lord.† Of consequence, before writing

“by Influx, your prayer must be to Him, for His Guidance, Influx, and

“Protection.”

The argument following exhibits Dr. Wilkinson’s view that the character

of his inspiration was pentecostal, as he proceeds to demonstrate his ortho-

doxy as a New Churchman. “Suffice it to say,” a further explanation

adds, “ that every piece was produced without premeditation or preconcep-

tion :

* Sometimes accompanied by a prayer or spell, invariably trash :

First shall his state be sung : (Turner’s)

Then his art’s bell be rung.

† Cf. Jakob Böhme, Sämmtliche Werke, Vol. vi. page 445 : “Davon weiss ich zu sagen, was das für ein

Licht und Bestättigung sei, wer das Centrum Naturä erfindet. Aber keine eigene Vernunft

erlanget es ; Gott

versperret es zwar Niemandem, aber es muss in Gottesfurcht mit stetem Anhalten und

Beten gefunden werden

. . . .sage ich treulich, als ich hoch im Centro Naturä und im Principio des Lebens

erkannt habe.”

23

“tion: had these processes stolen in, such production would have been

“impossible. The longest pieces in the volume occupied from thirty to

“forty-five minutes.* The production was attended by no feeling, and by

“no fervour, but only by an anxiety of all the circumstant faculties, to

“observe the unlooked for evolution, and to know what would come of it.”

An isolated individual opinion has only a limited worth ; another critic

or occasion may develop the suggestion that the phenomenon of the Wil-

kinson poems is that of Ecstatic Memory. The experience of all poets,

the sharply defined periods of their power, and the links between the life of

thought and the moment of creation, shall come in aid to that intent. For

a heavenly development there are two general requisites. The first is, an

unremitting assiduity in all that naturally concerns the subject: the entire

knowledge and manipulation and progress of the thing as far as industry

can attain them. The second is, the heart’s Prayer to the Lord, in New

Church language, as good for the moment as any other name for spiritual

disposition.

Concerning the speech of angels with man, Swedenborg lays down that

the thought of man coheres with his memory, and his speech flows from it,

therefore, when an angel or spirit is turned to him and conjoined with him.

This is one of a thousand such definitions of Swedenborg which cover

more or less completely, and invest such results as the Improvisations with

authority, in the sense of spiritual knowledge.

P.S.—As an afterthought perhaps there may be no harm in printing out

The Birth of Adam in extenso:

From the rock a sound went forth :

’Twas an echo of the north :

On the sea much people stood :

’Twas the archangelic brood.

There was silver silence heard :

Sound as of creation’s bird,

When with noiselessness of wing,

He doth wake the morning’s string.

Ever and anon the noon

Glowed with deeper presence down,

And the archangelic band,

Mated heart, and clasped hand.

Came a finger o’er the sea,

Shoulder in eternity,

Where the palace infinite

Darkens with excess of light.

And

* The poem called The Second Vüluspá, the longest in the book (336 unrhymed

two-footed verses) occupied from fifty to sixty minutes.

24

And it stooped to rock of earth,

Touched it with a loving girth ;

Spanned it betwixt finger span.

Where a lightning river ran.

Where a love-eternal ray

From each finger-tip did play,

And the rock between was changed,

Where the loving lightning ranged.

And the mood of many things,

Rose into the air on wings,

And the river-lightning ran,

Music in creation-plan.

Then the rock perceived its glow,

And the rock began to flow,

And the image of the skies,

Slowly from the rock did rise.

And the finger-tips alone,

Were applied unto the stone,

And the builded Adam rose,

Like a man of outward shows.

And the mystery now lay

In a second finger-ray,

For the Adam incomplete,

Wanted all his bosom’s heat.

So the fingers once again,

Sprinkled on a lightning rain :

And the mystery of love,

Through Adamic heart did move.

But the fingers wandered now

To his vacancy of brow,

And the place of thought was filled

With the light those fingers willed.

Then his feet were next correct :

And no station circumspect,

But was put within their palms,

Fit for terra firma’s calms.

And his fingers, chosen joints,

That the oil of skill anoints,

Were the last completed tools :—

Over these the spirit rules.

25 So

So was Adam planned and made,

And his form and figure ’rayed

In the heaven, law after law,

In the firmamental jaw.

But no life was yet within :

For the heaven is but a skin:

And Archangels are but flies,

Save for that within them lies.

So in wonder silences,

Moved in rest eternal breeze,

And did mould without all ken

Body-soul in spirit men.

And then Adam lived : and life

Rolled down orders’ stages rife :

And the rock of earth that stood,

Sailed for time on primal flood.

26

OLD KITTY.

“Femme qui n’a filé toute sa vie

Tâche à passer bien des choses sans bruit.”—La Fontaine.

THE sun’s good-will to shine even usually on the place

favoured heavenly origin. A hill, too, each red-cheeked

dawn perchance found tell-tale ; for of it half appeared to

have been crushed by three streets piled against the raw

side of the remnant—mere one-storey cottages the loftiest

gables seemed, seen from the land, while ships, in which

many men might pass months not over-cramped, shadowed with sails the

doorways, and”scrawled with rigging the outlook toward the river.

“ But old women’s tales stumble beginning ; they know the end better,”

so the folk themselves said, who should have been well-informed ; certain it

is children pick flowers, and girls even among green fruit find some sweet.

Kitty’s crib next beneath the sky was made bright by sun-flowers turned

to gaze over the roof ; the fronts being so gay that wharf-loungers got

cricked necks, unable to take eyes off dancing windows attractive as though

a buxom wench were at toilette behind every lattice.

Scattered on several hills, the town showed a general tendency to huddle

in the bottoms, leaving grass, pasture for single donkeys and goats, above,

where wind bullied butterflies.

Each morning old Kitty clattered down, basket on arm, and took her way

through the market ; not that she had, but lacked, business : so from

morning to night went odd-jobbing for anyone.

There was bustle, as when ant-hills stand base to base, on stone steps, on

wooden, through streets which had better have been stairs, of scandal-

mongers who spiced jolly lives with small malice. One stood face to face

with heaven, as did drunkards and idiots, at street-corners; so many the

ups and downs were.

A dwarf innocent started from the wharves at nightfall to climb between

the houses, a great labour foredoomed of unsuccess, yet with smiles

attempted. “ Luck to you ” lads shouted, hurrying past to their sweet-

hearts; or, with a girl, dawdled, and whispering laughed : she coyly looked

pity. Endless steps, on which at length weakly his body found rest : the

dew-moist slab inducing dreams, Kitty, benignant as he whom Jacob saw

from the foot of a ladder mounting higher still, was revealed.

“ I had supper alone last night”—“When none talks in the dark, one

counts every turn between cold sheets,” mornings and evenings, going or

returning, she said to this almost dumb beast, who, adoring through vague

years, had grown as faithful as habit. Crude expectancies of bliss, such as,

inspired by the lubber’s chaff in his vacant head, made song, she, plain of

speech as person, fostered ; thus beer-begotten the drama grew ; rivals

appeared—David, a mason, whose Welsh name was made difficult by

redundance of consonants beyond a legend’s retention (on this simple one

he even wished some grafted), who had come to learn what might be from

foreign stone-cutters at work on the new St. Mary’s church.

Gay fellows, noisy as birds, their jargoning not better understood, like a

27 colony

colony of over-sea daws, busily they laboured and had nigh filled the build-

ing with saints, and covered it in devils. One of them made a second

rival ; after a fortnight of silent acquaintance-making, they would chat

each day, when she passed, for as much as twenty minutes, neither of them

repaid save by the outflow.

To work, of all but a loin-cloth he jauntily stripped himself. So much

coquetry, however, a dandy never got from a fine suit ; such artifice was in

a napkin, neither girl nor matron could pass without her eye being drawn

thither and thus led to contemplation of splendid nudity.

The chips sprang in the sun ; merrily the ring of the chisel on the stone

followed the short thud of the mallet ; industrious, he never turned but for

Kitty and a tavern-wench with flagon, which was perhaps his secret.

David had come, silent man, from mountains. Not caring to ask ques-

tions, he put up at a wharf-side lodging : all gay wags knew the house ;

the riff-raff sneaked thither when honest folk and rooks went home ; damp

dust stank between slatternly scrubbed boards. Fagged, he sat down

(economy lit no candle) and dozed ; laughter hung round him drowsily,

grew harsher, and broke through his nap ; from the next room, up ram-

shackle hoarding, light climbed in lines to the rafters, blotted out evidently

by a huge wardrobe near the door.

Women, who talked loudly to be overheard, using what words ! David

knew he was fallen among harlots. David was pious ; still pious men are

tempted. He was ; and remembered how much had been forgiven to Solo-

mon and that great king his namesake. They were kings.

No curtain hid the stars. These women might not be clean, so many

lewd men as there are in towns. Starting, he discovered they were naked ;

some leant against the planks,’bending them, broadening the chinks, through

which they peeped joking of his sleep’s soundness. The boards so bulged

that light, creeping round, suggested features, hints to discovery; ambi-

guity of indication lured David, as it used old geographers, through slight-

ness of positive knowledge, to locate in unknown parts mountains, fertile

districts, and where rivers ran : sudden fear lest the hoarding give dissi-

pated these studies. Hurriedly, while they, remiss, flagged, he crept

tip-toe, lifting his stool to within the blank caused by the press, got

up, and began working the nails, which held the top where was the most

strain, with strong leathery finger and thumb, till they came out ; with the

third it would do. Descending he set ajar the door, during a burst of

uproar. Just when again his board yearned like a tree about to bring forth

a dryad, ready, he gave the last wrench. The dwarf, sleeping, was passed,

before, slackening speed, he shook the nail free from his indented thumb,

which he put in his mouth. Still with each step a bare arm and leg shot

after the leaning plank awkwardly : uncanny; he almost fancied claws.

Arrived in the fine summer night, he met a meadow-sweet land-breeze, and

saw Kitty awaiting her lover ; dazed, from the stars she turned towards him:

over his stony-passive self, as, after drought, rains revivify the dusty track

of a hill-stream, trust washed ; he asked, as of a mother, a bed.

28 At

At his open lattice next morning, smiling that his bundle had not been

lost in his hurry, he saw her arrive from the well on the second terrace ;

as she lifted her yoke, firm, beaded shoulders, a contrast to last night’s lewd

gleam, shone blithely.

He became her lodger, and giant anxiety to the little half-man far below ;

but returned to his hills and kith, without having once quickened Kitty’s

pulse.

Still well-conditioned, old rather by familiarity than age, her days, like

those of a plant, long ago had, like genet’s trot, kept up and down constantly

not evenly. The blood has a tricksy itch during the teens, which keeps one

a-tip-toe ; lively as a sea-cave all day long, would she laugh like its echoes.

On the road to a bean-feast once she had found every seat taken. When

the going began to jerk, making a confusion of impetus, and balance diffi-

cult to be kept, every one offered their knees, of course ; nearly all somehow

were fellows in that waggon. An uncle who had her in charge sat outside

on the rail singing with no savour of tune ; good man, he had thought

himself equally disgraced not to get drunk on saints’ days and like occa-

sions as to be anything but sober the rest of the year. She tried first one

then another of the proffered laps, none suiting till at last, lured by gay

dark eyes, she settled on knees of a foreign lad ; his jacket he had doubled

across them, though naturally a plump cushion, the whole made to exactly

suit the little romp by his keeping his heels off the ground : so that, in those

lie-a-bed times, no queen’s carriage had such capital springs ; while his

gibberish, sparely sprinkled with recognisable English, kept her in fits.

Suddenly the good uncle, still quite sober, was shot from his precarious

position into a hedge-bank.

Everybody got down in the roused dust to pick him up, his wrist broken,

his neck, wryed by bending above the lasts, only saved by a thick clump

of weeds, partly nettles ; their revenge distracted his attention from the

more serious disaster.

They put him under charge of an ill-grown loon. Then Kitty in tears

drew notice ; vainly was she assured, he would soon get better, this not

being her trouble ; now, she must go back. Such innocent fears were soon

laid : all vowed to take care of her ; the foreign friend repeating “ take

care” so funnily, she had to laugh.

An hour later those two words, so endearingly protective, kept purring

to her ears from amid sleek Gascon. He climbed like a monkey till fear

betrayed her, chased damsel-flies, or brought sprigs of bryony, their budded

green soft as love-bird down, to enrich her hair ; spider-webs, from which

shadows withdrew, shone like wide white disks, till she felt unsafely tall

and wished to sit down. Noon had stilled her limbs’ buoyancy, though

beneath saucy strays of hair her eyes continued dancing. All bodily per-

fections of errant knight and ballad hero—such an upset her young blood,

gaining no due expression in skipping feet, put her wits in—got jolted over

to his account ; every virtue of saint or bible story became part and parcel

of this unintelligible boy ; neither saint or angel stayed her, but she must

29 even

even draft from the blessed Lord himself, none else possessing sufficience.

What wonder she made small objection, when he kissed and they found

themselves alone deep in the sunshine ; nay, into the wood followed him

through mysterious places, which stir has quitted as the tide does caves

where a constant drip seems the faint pulse which tells that some one lives?

Here no heart beat but their own, passing down shady ways even to the

strange land of sleep—birthlike, dawnlit, as baby dreams long obliterated.

Inside the door, just beyond midnight, her mother and a candle first woke

her. The hasty run through late twilight for the waggon, drunken roys-

tering jolted through the night, all far-away : only those cooing unknown

words near, beneath a stuffy cloak : even when, parting, a neighbour dragged

her wrist, it seemed but some waif rudeness, pitiful in heaven.

“I’m in love, and we’ve slept together in the wood,” then questions, then

tears. Noticing the light, the good priest stepped in; taken into confidence,

he thought, seeing she loved him so, reporting with such high eulogy, it

were best to marry them, and undertook to hunt up the bridegroom, whose

name even was not known ; but the description was vivid. After visiting

two or three inns, he found him heavy with sleep as a winter dormouse,

turned the key, and took it away.

In time a new life, from no one knows where, was expected as witness

and consummation to this oddly arranged marriage.

A sharp fellow ; clever at his craft, wood-carving for the new choir;

gaining sufficient to pacify the mother : though often out at nights, drunk

—“ and worse” neighbours said. Winter drawing to a close, he grew dis-

contented, by no will of his married, mewed up with a girl unable to talk

with him ; till, returning one night to find mother-in-law and midwife

installed, being not more sober than uncle Ben on saint days, there ensued

a skirmish; he staggered upstairs into the room that she with a shriek filled:

all resulting in the small life’s return to its place.

Seemingly, she lay dead. When his wits came together, he could hear

neighbours below called by the infuriated beldames ; so let himself out of

window and by backways, hunted of accusing cries ; scuttled down to the

wharves, with fox-like wariness ; smuggled himself aboard a vessel which

stole silently seaward before dawn ; and thenceforth was drifted by un-

stable elements safely home to the unreflecting shallows of a blithe life.

T. STURGE MOORE

30

A HYMN TRANSLATED FROM THE ITALIAN OF SAINT FRANCIS OF ASSISI.

Love setteth me a-burning.

When my new Spouse had won me;

My piteous state discerning,

Had set His ring upon me:

The conqueror’s prize returning,

Love’s knife had all undone me,

All my heart broke with yearning.

Love setteth me a-burning.

My heart was broke asunder:

Earthward my body sprawling,

The arrow of Love’s wonder

From out the crossbow falling,

Like to a shaft of thunder

Made war of peace, enthralling

My life for passion’s plunder.

Love setteth me a-burning.

I die of very sweetness.

Yet be thou not astounded.

That lance of Love’s completeness

So sorrowfully wounded!

Oh, broad the iron’s meetness!

Not one arm’s length, a hundred

Has pierced me with its fleetness.

Love setteth me a-burning.

Then were the lances scattered

The ballister was flinging;

And aye the blows which battered

Upon my shield were ringing.

What could protect me, tattered,

Before that engine sinking?

So was I wholly shattered.

Love setteth me a-burning.

Assailed with such instruction

That all my bulwarks bevelled,*

Well nigh was I destruction

And shamefully dishevelled.

Still hear my sorrow’s fiction:

Anew a crossbow levelled

Vouchsafed me new affliction.

Love setteth me a-burning.

* Dr. Swift.

31 Such

Such perils did it vomit,

Great stones with metal weighted;

And every missile from it

With pounds a thousand freighted.

Plummet on awful plummet,

Hail unenumerated,

Urged with an aim consummate.

Love setteth me a-burning.

None missed; and nought defended

My breast from their unerring.

To earth I fell, distended,

No pulse within me stirring:

No longer I pretended

To meet the blows recurring;