The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume XIII April 1897

Contents

Literature

I. The Blessed . . . By W. B. Yeats . . Page 11

II. Merely Players . .Henry Harland . . 19

III. Sonnets from the

Portuguese Richard Garnett, C.B.,

LL.D. . . . . 51

IV. The Christ of Toro . Mrs. Cunningham Grahame 56

V. The Question . . Stephen Phillips . . 74

VI. Concerning Preciosity . John M. Robertson . . 79

VII. Sir Dagonet’s QuestF. B. Money Coutts . . 107

VIII. The Runaway . . Marion Hepworth Dixon . 110

IX. Pierrot . . . . Olive Custance . . 121

X. On the Toss of a PennyCecil de Thierry . . 129

XI. April of England . . A. Myron . . . 143

XII. At Old Italian Case-mentsDora Greenwell McChesney 144

XIII. The Rose . . . Henry W. Nevinson . . 153

XIV. An Immortal . . Sidney Benson Thorp . 156

XV. The Noon of Love . J. A. Blaikie . . . . 167

XVI. The Other Anna . . Evelyn Sharp . . . 170

XVII. Two Poems . . . Douglas Ainslie . . 194

XVIII. A Melodrama . . T. Baron Russell . . 205

XIX. Oasis . . . . Rosamund Marriott Watson 212

XX. A Pair of Parricides . Francis Watt . . . 213

XXI. Kit: an American Boy . Jennie A. Eustace . . 237

XXII. Forgetfulness . . . R. V. Risley . . . 257

XXIII. Lucy Wren . . . Ada Radford . . . 272

XXIV. Sir Julian Garve . . Ella D’Arcy . . . 291

XXV. Two Prose Fancies . Richard Le Gallienne . 308

The Yellow Book— Vol. XIII. — April, 1897

Art

Art

I. Vanity . . . By D.Y. Cameron . Page 7

II. Winter Evening on the

Clyde Muirhead Bone . . 14

III. Old Houses off the Dry

Gate, Glasgow

IV. The Black Cockade . Katharine Cameron . . 76

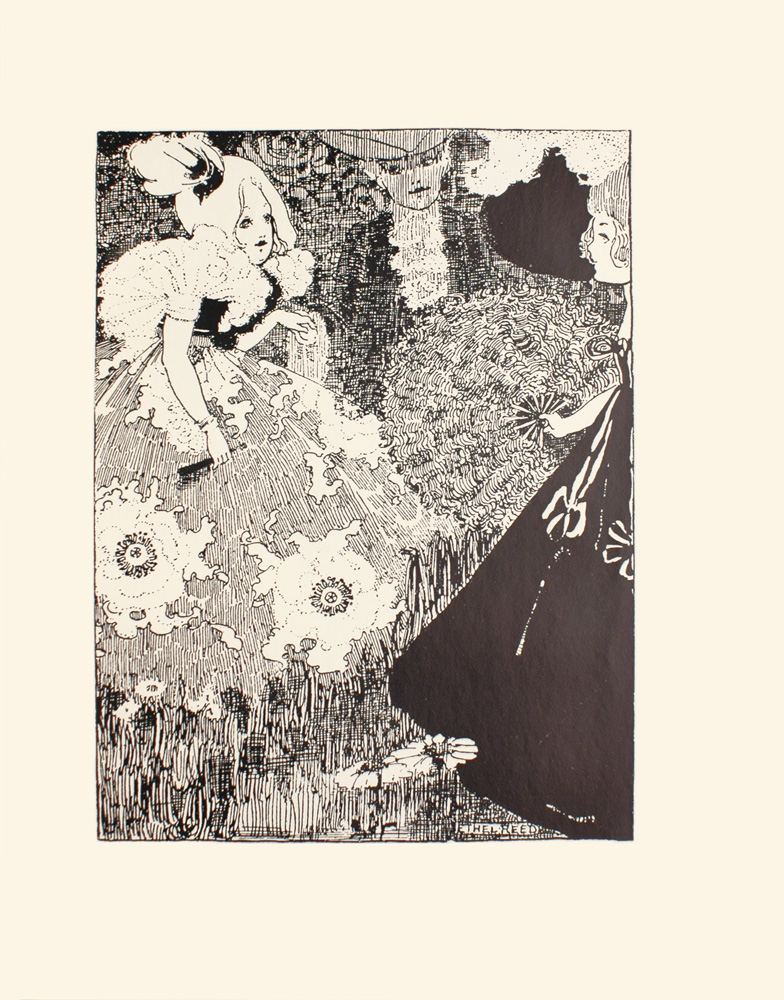

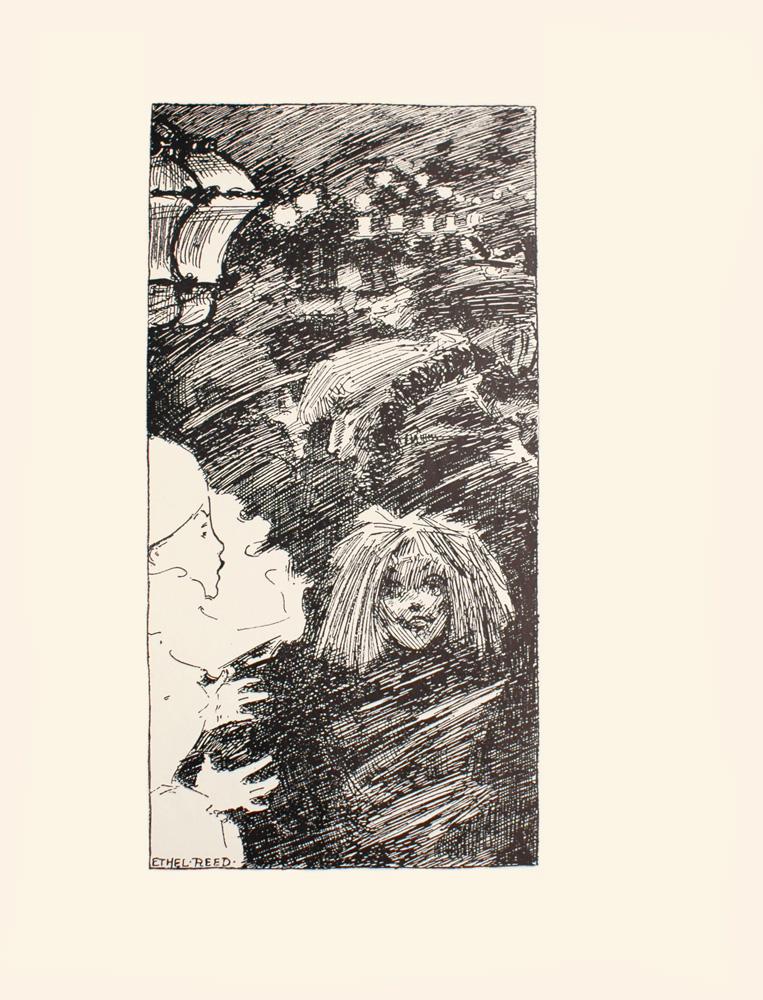

V. An Introduction . . Ethel Reed . . . 123

VI. A Vision . . .

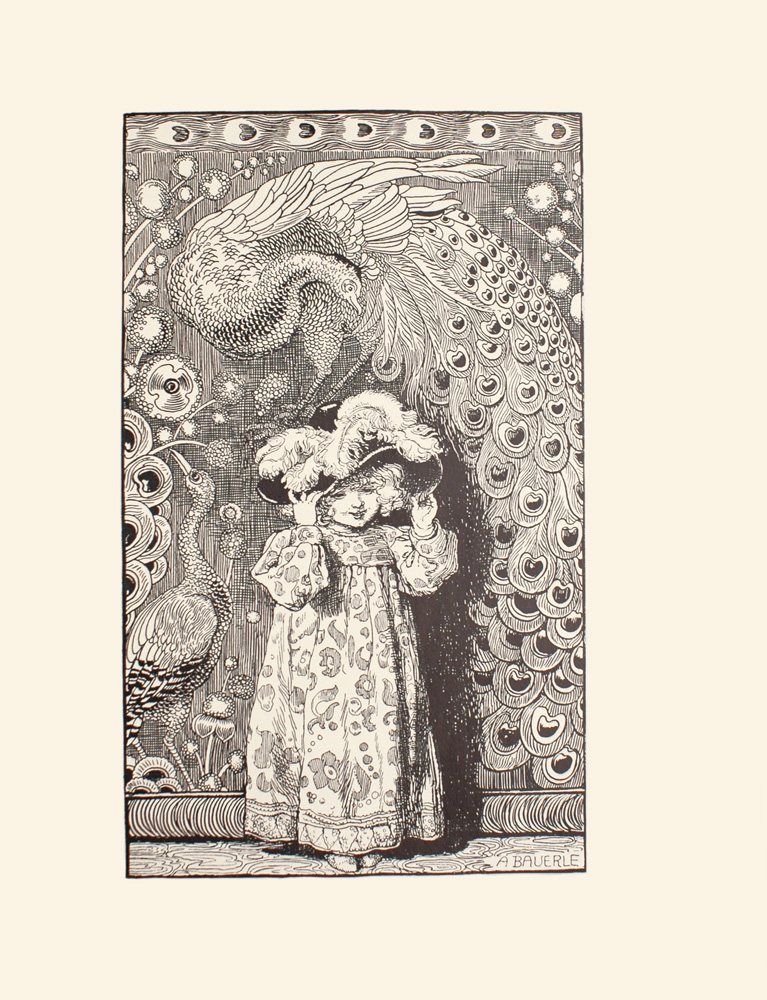

VII. Fine Feathers make Fine

Birds . . . A. Bauerle . . . 149

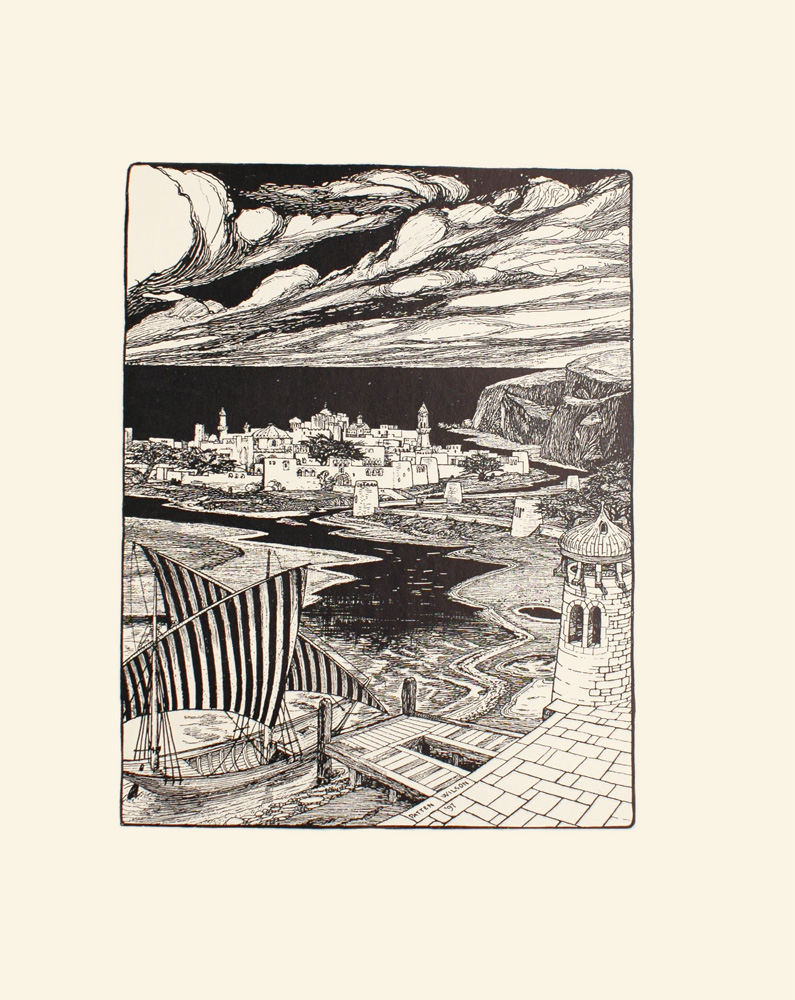

VIII. An Eastern TownPatten Wilson . . . 197

IX. Book-plate of Egerton

Clairmonte, Esq.

X. Book-plate of H. B.

Marriott Watson, Esq.

XI. Book-plate of S. Carey

Curtis, Esq..

XII. Helen . . . E. J. Sullivan . . 227

XIII. The Sorceress . .

XIV. The Couch . .

XV. The Mirror . .

XVI. The Fairy Prince . Charles Conder . . 285

XVII. A Masque . . .

XVIII. A Shepherd Boy . . E. Philip Pimlott . . 317

The cover-design is by

Mabel Syrett, the

design on

the title-page by

Patten Wilson.

The half-tone blocks in this Volume, and

in Volumes XI. and XII., are by W. H. Ward & Co.

The line-blocks are by Carl Hentschel

& Co.

The Blessed

By W. B. Yeats

CUMHAL the king, being angry and sad,

Came by the woody way

To the cave, where Dathi the Blessed had gone,

To hide from the troubled day.

Cumhal called out, bowing his head,

Till Dathi came and stood,

With blinking eyes, at the cave s edge,

Between the wind and the wood.

And Cumhal said, bending his knees,

” I come by the windy way

To gather the half of your blessedness

And learn the prayers that you say.

” I can bring you salmon out of the streams

And heron out of the skies.”

But Dathi folded his hands and smiled

With the secrets of God in his eyes.

And

And Cumhal saw like a drifting smoke

All manner of blessedest souls,

Children and women and tonsured young men,

And old men with croziers and stoles.

” Praise God and God s Mother,” Dathi said,

” For God and God s Mother have sent

The blessedest souls that walk in the world

To fill your heart with content.”

” And who is the blessedest,” Cumhal said,

” Where all are comely and good ?

Is it those that with golden thuribles

Are singing about the wood ? “

” My eyes are blinking,” Dathi said,

“With the secrets of God half blind.

But I have found where the wind goes

And follow the way of the wind ;

” And blessedness goes where the wind goes

And when it is gone we die ;

And have seen the blessedest soul in the world,

By a spilled wine-cup lie.

” O blessedness comes in the night and the day,

And whither the wise heart knows ;

And one has seen, in the redness of wine,

The Incorruptible Rose :

“The

“The Rose that must drop, out of sweet leaves,

The heaviness of desire,

Until Time and the World have ebbed away

In twilights of dew and fire ! ”

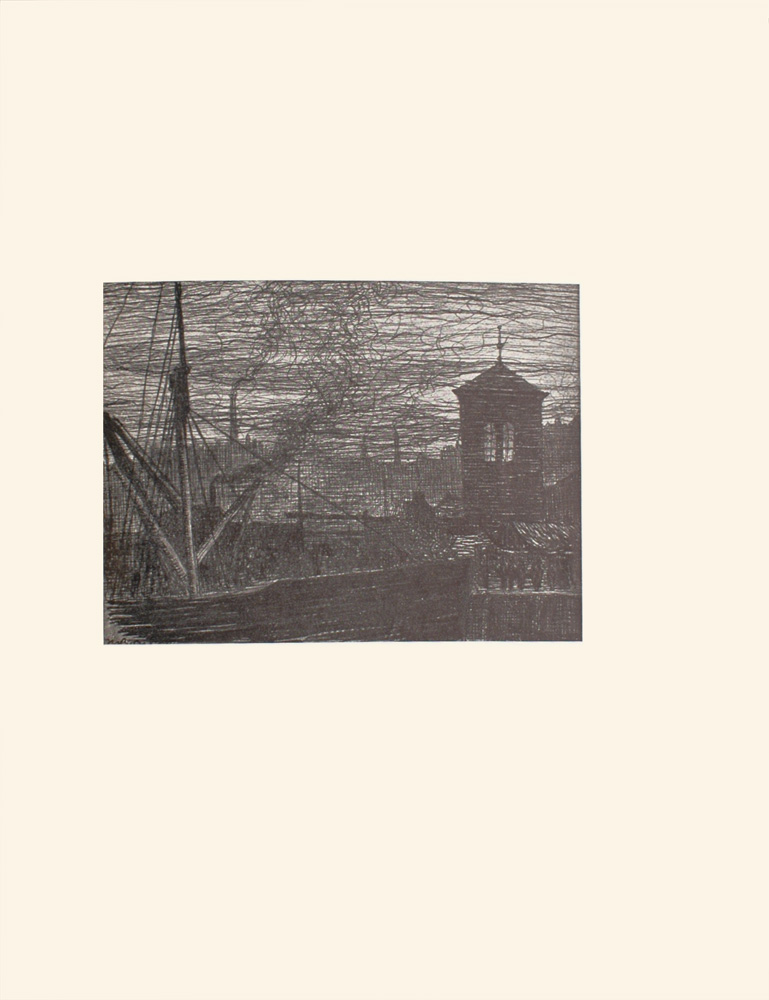

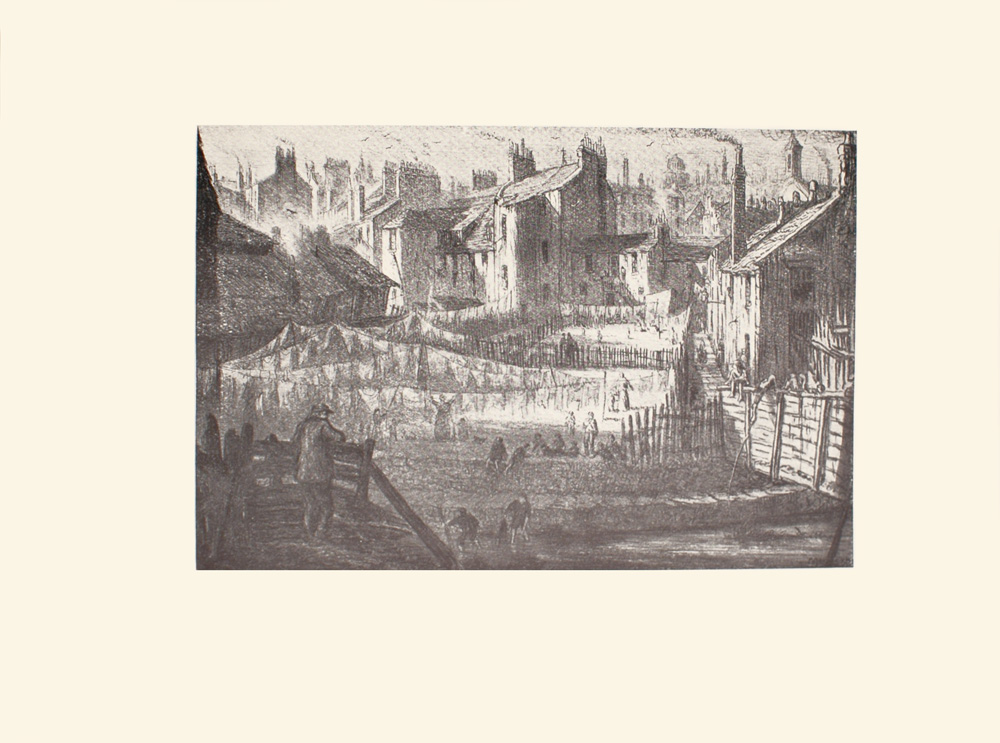

Two Pictures

By Muirhead Bone

I. Winter Evening on the Clyde

II. Old Houses off the Dry Gate, Glasgow

Merely Players

I

“MY dear,” said the elder man, “as I’ve told you a thousand

times, what you need is a love-affair with a red-haired

woman.”

“Bother women,” said the younger man, “and hang love-affairs.

Women are a pack of samenesses, and love-affairs are damnable

iterations.”

They were seated at a round table, gay with glass and silver,

fruit and wine, in a pretty, rather high-ceiled little grey-and-gold

breakfast-room. The French window stood wide open to the soft

June day. From the window you could step out upon a small

balcony ; the balcony overhung a terrace ; and a broad flight of

steps from the terrace led down into a garden. You could not

perceive the boundaries of the garden ; in all directions it offered

an indefinite perspective, a landscape of green lawns and shadowy

alleys, bright parterres of flowers, fountains, and tall, bending

trees.

I have spoken of the elder man and the younger, though really

there could have been but a trifling disparity in their ages : the

elder was perhaps thirty, the younger seven or eight and twenty.

In

In other respects, however, they were as unlike as unlike may be.

Thirty was plump and rosy and full-blown, with a laughing good-

humoured face, and merry big blue eyes ; eight and twenty, thin,

tall, and listless-looking, his face pale and aquiline, his eyes dark,

morose. They had finished their coffee, and now the plump man

was nibbling sweetmeats, which he selected with much careful

discrimination from an assortment in a porcelain dish. The thin

man was drinking something green, possibly chartreuse.

“Women are a pack of samenesses,” he grumbled, “and love-

affairs are damnable iterations.”

“Oh,” cried out his comrade, in a tone of plaintive protest, “I

said red-haired. You can’t pretend that red-haired women are the

same.”

“The same, with the addition of a little henna,” the pale young

man argued wearily.

“It may surprise you to learn that I was thinking of red-haired

women who are born red-haired,” his friend remarked, from an

altitude.

“In that case,” said he, “I admit there is a difference—they

have white eyelashes.” And he emptied his glass of green stuff.

“Is all this àpropos of boots ?” he questioned.

The other regarded him solemnly. “It’s àpropos of your

immortal soul,” he answered, nodding his head. “It’s medicine

for a mind diseased. The only thing that will wake you up, and

put a little life and human nature in you, is a love-affair with a red-

haired woman. Red in the hair means fire in the heart. It

means all sorts of things. If you really wish to please me, Uncle,

you’ll go and fall in love with a red-haired woman.”

The younger man, whom the elder addressed as Uncle, shrugged

his shoulders, and gave a little sniff. Then he lighted a cigarette.

The elder man left the table, and went to the open window.

“Heavens,

“Heavens, what weather !” he exclaimed fervently. “The day

is made of perfumed velvet. The air is a love-philtre. The

whole world sings romance. And yet you—insensible monster !

—you can sit there torpidly—” But abruptly he fell silent.

His attention had been caught by something below, in the

garden. He watched it for an instant from his place by the

window; then he stepped forth upon the balcony, still watching.

Suddenly, facing half-way round, “By my bauble, Nunky,” he

called to his companion, and his voice was tense with surprised

exultancy, she’s got red hair !”

The younger man looked up with vague eyes. “Who ?

What ?” he asked languidly.

“Come here, come here,” his friend urged, beckoning him.

“There,” he indicated, when the pale man had joined him,

“below there—to the right—picking roses. She’s got red hair.

She’s sent by Providence.”

A woman in a white frock was picking roses, in one of the

alleys of the garden ; rather a tall woman. Her back was turned

towards her observers ; but she wore only a light scarf of lace over

her head, and her hair—soft-brown, fawn-colour, in its shadows—

where the sun touched it, showed a soul of red.

The younger man frowned, and asked sharply, “Who the devil

is she ?”

“I don’t know, I’m sure,” replied the other. “One of the

Queen’s women, probably. But whoever she is, she’s got red

hair.”

The younger man frowned more fiercely still. “What is she

doing in the King’s private garden ? This is a pretty state of

things.” He stamped his foot angrily. “Go down and turn her

out. And I wish measures to be taken, that such trespassing may

not occur again.”

But

But the elder man laughed. “Hoity-toity ! Calm yourself,

Uncle. What would you have ? The King is at a safe distance,

hiding in one of his northern hunting-boxes, sulking, and nursing

his spleen, as is his wont. When the King’s away, the palace mice

will play—at lèse majesté, the thrilling game. If you wish to

stop them, persuade the King to come home and show his face.

Otherwise, we’ll gather our rosebuds while we may ; and I’m not

the man to cross a red-haired woman.”

“You’re the Constable of Bellefontaine,” retorted his friend,

“and it’s your business to see that the King’s orders are

respected.”

“The King’s orders are so seldom respectable ; and then, I’ve

a grand talent for neglecting my business. I’m trying to elevate

the Constableship of Bellefontaine into a sinecure,” the plump

man explained genially. “But I’m pained to see that your sense

of humour is not escaping the general decay of your faculties.

What you need is a love-affair with a red-haired woman ; and

yonder’s a red-haired woman, dropped from the skies for your

salvation. Go—engage her in talk—and fall in love with her.

There’s a dear,” he pleaded.

“Dropped from the skies,” the pale man repeated, with mild

scorn. “As if I didn’t know my Hilary ! Of course, you’ve

had her up your sleeve the whole time.”

“Upon my soul and honour, you are utterly mistaken. Upon

my soul and honour, I’ve never set eyes on her before,” Hilary

asseverated warmly.

“Ah, well, if that’s the case,” suggested the pale man, turning

back into the room, “let us make an earnest endeavour to talk of

something else.”

The

II

The next afternoon they were walking in the park, at some

distance from the palace, when they came to a bridge over a bit of

artificial water ; and there was the woman of yesterday, leaning

on the parapet, throwing bread-crumbs to the carp. She looked

up, as they passed, and bowed, with a little smile, in acknowledg-

ment of their raised hats.

When they were out of ear-shot, “H’m,” muttered Hilary,

“viewed at close quarters, she’s a trifle disenchanting.”

“Oh ?” questioned his friend. “I thought her very good-

looking.”

“She has too short a nose,” Hilary complained.

“What’s the good of criticising particular features ? The

general effect of her face was highly pleasing. She looked intel-

ligent, interesting ; she looked as if she would have something to

say,” the younger man insisted.

“It’s very possible she has a tongue in her head,” admitted

Hilary ; “but we were judging her by the rules of beauty. For

my fancy, she’s too tall.”

“She’s tall, but she’s well-proportioned. Indeed, her figure

struck me as exceptionally fine. There was something sumptuous

and noble about it,” declared the other.

“There are scores of women with fine figures in this world,”

said Hilary. “But I’m sorely disappointed in her hair. Her hair

is nothing like so red as I’d imagined.”

“You’re daft on the subject of red hair. Her hair’s not carrot-

colour, if you come to that. But there’s plenty of red in it. It’s

brown, with red burning through. The red is managed with

discretion—suggestively. And did you notice her eyes? She

The Yellow Book—Vol. XIII. B

has

has remarkably nice eyes—eyes with an expression. I thought

her eyes and mouth were charming when she smiled,” the pale

man affirmed.

“When she smiled ? I didn’t see her smile,” reflected Hilary.

“Of course she smiled—when we bowed,” his friend reminded

him.

“Oh, Ferdinand Augustus,” Hilary remonstrated, “will you

never learn to treat words with some consideration ? You call

that smiling ! Two men take off their hats, and a woman gives

them just a look of bare acknowledgment ; and Ferdinand

Augustus calls it smiling !”

“Would you have wished for a broad grin ?” asked Ferdinand

Augustus. “Her face lighted up most graciously. I thought

her eyes were charming. Oh, she’s certainly a good-looking

woman, a distinctly handsome woman.”

“Handsome is that handsome does,” said Hilary.

“I miss the relevancy of that,” said Ferdinand Augustus.

“She’s a trespasser. ‘Twas you yourself flew in a passion

about it yesterday. Yesterday she was plucking the King’s

roses : to-day she’s feeding the King’s carp.”

“‘When the King’s away, the palace mice will play.’ I venture

to recall your own words to you,” Ferdinand remarked.

“That’s all very well. Besides, I spoke in jest. But there are

limits. And it’s I who am responsible. I’m the Constable of

Bellefontaine. Her trespassing appears to be habitual. We’ve

caught her at it ourselves, two days in succession. I shall give

instructions to the keepers, to warn her not to touch a flower, nor

feed a bird, beast, or fish, in the whole of this demesne. Really,

I admire the cool way in which she went on tossing bread-crumbs

to the King’s carp under my very beard !” exclaimed Hilary,

working himself into a fine state of indignation.

“Very

“Very likely she didn’t know who you were,” his friend

reasoned. “And anyhow, your zeal is mighty sudden. You

appear to have been letting things go at loose ends for I don’t

know how long ; and all at once you take fire like tinder because

a poor woman amuses herself by throwing bread to the carp. It’s

simply spite : you’re disappointed in the colour of her hair. I

shall esteem it a favour ir you’ll leave the keepers’ instructions as

they are. She’s a damned good-looking woman ; and I’ll beg you

not to interfere with her diversions.”

“I can deny you nothing, Uncle,” said Hilary, by this time re-

stored to his accustomed easy temper; “and therefore she may make

hay of the whole blessed establishment, if she pleases. But as for

her good looks—that, you’ll admit, is entirely a question of taste.”

“Ah, well, then the conclusion is that your taste needs

cultivation,” laughed Ferdinand. “By-the-bye, I shall be glad if

you will find out who she is.”

“Thank you very much, “cried Hilary. “I have a reputation

to safeguard. Do you think I’m going to compromise myself,

and set all my underlings a-sniggling, by making inquiries about

the identity of a woman ?”

“But,” persisted Ferdinand, “if I ask you to do so, as

your—”

“What ?” was Hilary’s brusque interruption.

“As your guest,” said Ferdinand.

“Mille regrets, impossible, as the French have it,” Hilary

returned. “But as your host, I give you carte-blanche to make

your own inquiries for yourself—if you think she’s worth the

trouble. Being a stranger here, you have, as it were, no

character to lose.”

“After all, it doesn’t matter,” said Ferdinand Augustus, with

resignation,

But

III

But the next afternoon, at about the same hour, Ferdinand

Augustus found himself alone, strolling in the direction of the

little stone bridge over the artificial lakelet ; and there again was

the woman, leaning upon the parapet, dropping bread-crumbs to

the carp. Ferdinand Augustus raised his hat ; the woman bowed

and smiled.

“It’s a fine day,” said Ferdinand Augustus.

“It’s a fine day—but a weary one,” the woman responded, with

an odd little movement of the head.

Ferdinand Augustus was perhaps too shy to pursue the con-

versation ; perhaps he wanted but little here below, nor wanted

that little long. At any rate, he passed on. There could be no

question about her smile this time, he reflected ; it had been

bright, spontaneous, friendly. But what did she mean, he

wondered, by adding to his general panegyric of the day as fine,

that special qualification of it as a weary one ? It was astonishing

that any man should dispute her claim to beauty. She had really

a splendid figure ; and her face was more than pretty, it was

distinguished. Her eyes and her mouth, her clear-grey sparkling

eyes, her softly curved red mouth, suggested many agreeable

possibilities—possibilities of wit, and of something else. It was

not till four hours later that he noticed the sound of her voice.

At dinner, in the midst of a discussion with Hilary about a

subject in no obvious way connected with her (about the Orient

Express, indeed—its safety, speed, and comfort), it suddenly came

back to him, and he checked a remark upon the advantages of

the corridor-carriage, to exclaim in his soul, “She’s got a delicious

voice. If she sang, it would be a mezzo.”

The

The consequence was that the following day he again bent his

footsteps in the direction of the bridge.

“It’s a lovely afternoon,” he said, lifting his hat.

“But a weary one,” said she, smiling, with a little pensive

movement of the head.

“Not a weary one for the carp,” he hinted, glancing down at

the water, which boiled and bubbled with a greedy multitude.

“Oh, they have no human feelings,” said she.

“Don’t you call hunger a human feeling ?” he inquired.

“They have no human feelings ; but I never said we hadn’t

plenty of carp feelings,” she answered him.

He laughed. “At all events, I’m pleased to find that we’re on

the same way of thinking.”

“Are we ?” asked she, raising surprised eyebrows.

“You take a healthy pessimistic view of things,” he submitted.

“I ? Oh, dear, no. I have never taken a pessimistic view of

anything in my life.”

“Except of this poor summer’s afternoon, which has the fatal

gift of beauty. You said it was a weary one.”

“People have sympathies,” she explained ; “and besides, that is

a watchword.” And she scattered a handful of crumbs, thereby

exciting a new commotion among the carp.

Her explanation no doubt struck Ferdinand Augustus as obscure;

but perhaps he felt that he scarcely knew her well enough to press

for enlightenment. “Let us hope that the fine weather will last,”

he said, with a polite salutation, and resumed his walk.

But, on the morrow, “You make a daily practice or casting

your bread upon the waters,” was his greeting to her. “Do you

expect to find it at the season’s end ?”

“I find

“I find it at once,” was her response, “in entertainment.”

“It entertains you to see those shameless little gluttons making

an exhibition of themselves !” he cried out.

“You must not speak disrespectfully of them,” she reproved

him. “Some of them are very old. Carp often live to be two

hundred, and they grow grey, for all the world like men.”

“They’re like men in twenty particulars,” asserted he,” though

you, yesterday, denied it. See how the big ones elbow the little

ones aside ; see how fierce they all are in the scramble for your

bounty. You wake their most evil passions. But the spectacle

is instructive. It’s a miniature presentment of civilisation. Oh,

carp are simply brimful of human nature. You mentioned

yesterday that they have no human feelings. You put your finger

on the chief point of resemblance. It’s the absence of human

feeling that makes them so hideously human.”

She looked at him with eyes that were interested, amused, yet

not altogether without a shade of raillery in their depths. “That

is what you call a healthy pessimistic view of things ?” she

questioned.

“It is an inevitable view if one honestly uses one’s sight, or

reads one’s newspaper.”

“Oh, then I would rather not honestly use my sight,” said she ;

“and as for the newspaper, I only read the fashions. Your healthy

pessimistic view of things can hardly add much to the joy of life.”

“The joy of life !” he expostulated. “There’s no joy in life.

Life is one fabric of hardship, peril, and insipidity.”

“Oh, how can you say that,” cried she, “in the face of such

beauty as we have about us here ? With the pure sky and the

sunshine, and the wonderful peace of the day ; and then these

lawns and glades, and the great green trees ; and the sweet air,

and the singing birds ! No joy in life !”

“This

“This isn’t life,” he answered. “People who shut themselves

up in an artificial park are fugitives from life. Life begins at the

park gates with the natural countryside, and the squalid peasantry,

and the sordid farmers, and the Jew money-lenders, and the

uncertain crops.”

“Oh, it’s all life,” insisted she, “the park and the countryside,

and the virgin forest and the deep sea, with all things in them.

It’s all life. I’m alive, and I daresay you are. You would

exclude from life all that is nice in life, and then say of the

remainder, that only is life. You’re not logical.”

“Heaven forbid,” he murmured devoutly. “I’m sure you’re

not either. Only stupid people are logical.”

She laughed lightly. “My poor carp little dream to what far

paradoxes they have led,” she mused, looking into the water, which

was now quite tranquil. “They have sailed away to their myste-

rious affairs among the lily-roots. I should like to be a carp for a

few minutes, to see what it is like in those cool, dark places under

the water. I am sure there are all sorts of strange things and

treasures. Do you believe there are really water-maidens, like

Undine ?”

“Not nowadays,” he informed her, with the confident fluency

of one who knew. ” There used to be ; but, like so many other

charming things, they disappeared with the invention of printing,

the discovery of America, and the rise of the Lutheran heresy.

Their prophetic souls——”

“Oh, but they had no souls, you remember,” she corrected

him.

“I beg your pardon ; that was the belief that prevailed among

their mortal contemporaries, but it has since been ascertained that

they had souls, and very good ones. Their prophetic souls warned

them what a dreary, dried-up planet the earth was destined to

become,

become, with the steam-engine, the electric telegraph, compulsory

education (falsely so-called), constitutional government, and the

supremacy of commerce. So the elder ones died, dissolved in

tears ; and the younger ones migrated by evaporation to

Neptune.”

“Dear me, dear me,” she marvelled. “How extraordinary

that we should just have happened to light upon a topic about

which you appear to have such a quantity of special knowledge !

And now,” she added, bending her head by way of valediction, “I

must be returning to my duties.”

And she moved off, towards the palace.

IV

And then, for three or four days, he did not see her, though he

paid frequent enough visits to the feeding-place of the carp.

“I wish it would rain,” he confessed to Hilary. “I hate the

derisive cheerfulness of this weather. The birds sing, and the

flowers smile, and every prospect breathes sodden satisfaction ;

and only man is bored.”

“Yes, I own I find you dull company,” Hilary responded, “and

if I thought it would brisk you up, I’d pray with all my heart for

rain. But what you need, as I’ve told you a thousand times, is a

love-affair with a red-haired woman.”

“Love-affairs are tedious repetitions,” said Ferdinand. “You

play with your newpartner precisely the same game you played with

the old : the same preliminary skirmishes, the same assault, the

sune feints of resistance, the same surrender, the same subsequent

disenchantment. They’re all the same, down to the very same

scenes, words, gestures, suspicions, vows, exactions, recriminations,

and

and final break-ups. It’s a delusion of inexperience to suppose that

in changing your mistress you change the sport. It’s the same

trite old book, that you’ve read and read in different editions,

until you’re sick of the very mention of it. To the deuce with

love-affairs. But there’s such a thing as rational conversation,

with no sentimental nonsense. Now, I’ll not deny that I should

rather like to have an occasional bit of rational conversation with

that red-haired woman we met the other day in the park. Only,

the devil of it is, she never appears.”

“And then, besides, her hair isn’t red,” added Hilary.

“I wonder how you can talk such folly,” said Ferdinand.

“C’est mon métier, Uncle. You should answer me according to

it. Her hair’s not red. What little red there’s in it, it requires

strong sunlight to bring out. In shadow her hair’s a sort of dull

brownish-yellow,” Hilary persisted.

“You’re colour-blind,” retorted Ferdinand. “But I won’t

quarrel with you. The point is, she never appears. So how can

I have my bits of rational conversation with her ?”

“How indeed ?” echoed Hilary, with pathos. “And there-

fore you’re invoking storm and whirlwind. But hang a horseshoe

over your bed to-night, turn round three times as you extinguish

your candle, and let your last thought before you fall asleep be the

thought of a newt’s liver and a blind man’s dog ; and it’s highly

possible she will appear to-morrow.”

I don’t know whether Ferdinand Augustus accomplished the

rites that Hilary prescribed, but it is certain that she did appear on

the morrow : not by the pool or the carp, but in quite another

region of Bellefontaine, where Ferdinand Augustus was wandering

at hazard, somewhat disconsolately. There was a wide green

meadow, sprinkled with buttercups and daisies ; and under a great

tree, at this end of it, he suddenly espied her. She was seated on

the

the moss, stroking with one finger-tip a cockchafer that was

perched upon another, and regarding the little monster with in-

tent, meditative eyes. She wore a frock the bodice part of which

was all drooping creamy lace ; she had thrown her hat and gloves

aside ; her hair was in some slight, soft disarray ; her loose sleeve

had fallen back, disclosing a very perfect wrist, and the beginning

of a smooth white arm. Altogether she made an extremely

pleasing picture, sweetly, warmly feminine. Ferdinand Augustus

stood still, and watched her for an instant, before he spoke.

Then—

“I have come to intercede with you on behalf of your carp,”

he announced. “They are rending heaven with complaints of

your desertion.”

She looked up, with a whimsical, languid little smile. “Are

they ?” she asked lightly. “I’m rather tired of carp.”

He shook his head sorrowfully. “You will permit me to

admire your fine, frank disregard of their feelings.”

“Oh, they have the past to remember,” she said. “And per-

haps some day I shall go back to them. For the moment

I amuse myself very well with cockchafers. They’re less

tumultuous. And then carp won’t come and perch on your

finger. And then, one likes a change.—Now fly away, fly away,

fly away home ; your house is on fire, and your children will

burn,” she crooned to the cockchafer, giving it never so gentle a

push. But instead of flying away, it dropped upon the moss, and

thence began to stumble, clumsily, blunderingly, towards the open

meadow.

“You shouldn’t have caused the poor beast such a panic,” he

reproached her. “You should have broken the dreadful news

gradually. As you see, your sudden blurting of it out has

deprived him of the use of his faculties. Don’t believe her,” he

called

called after the cockchafer. “She’s practising upon your credulity.

Your house isn’t on fire, and your children are all safe at school.”

“Your consideration is entirely misplaced,” she assured him,

with the same slight whimsical smile. “The cockchafer knows

perfectly well that his house isn’t on fire, because he hasn’t got any

house. Cockchafers never have houses. His apparent concern is

sheer affectation. He’s an exceedingly hypocritical little cock-

chafer.”

“I should call him an exceedingly polite little cockchafer.

Hypocrisy is the compliment courtesy owes to falsehood. He

pretended to believe you. He would not have the air of doubting

a lady’s word.”

“You came as the emissary of the carp,” she said ; “and now

you stay to defend the character of their rival.”

“To be candid, I don’t care a hang for the carp,” he confessed

brazenly. “The unadorned fact is that I am immensely glad to

see you.”

She gave a little laugh, and bowed with exaggerated ceremony

“Grand merci. Monsieur ; vous me faites trop d’honneur,” she

murmured.

“Oh, no, not more than you deserve. I’m a just man, and I

give you your due. I was boring myself into melancholy madness.

The afternoon lay before me like a bumper of dust and ashes, that

I must somehow empty. And then I saw you, and you dashed

the goblet from my lips. Thank goodness (I said to myself), at

last there’s a human soul to talk with ; the very thing I was

pining for, a clever and sympathetic woman.”

“You take a great deal for granted,” laughed she.

“Oh, I know you’re clever, and it pleases me to fancy that

you’re sympathetic. If you’re not,” he pleaded, “don’t tell me so.

Let me cherish my illusion.”

She

She shook her head doubtfully. “I’m a poor hand at

dissembling.”

“It’s an art you should study,” said he. “If we begin by

feigning an emotion, we’re as like as not to end by genuinely

feeling it.”

“I’ve observed for myself,” she informed him, “that if we

begin by genuinely feeling an emotion, but rigorously conceal it,

we’re as like as not to end by feeling it no longer. It dies of

suffocation. I’ve had that experience quite lately. There was a

certain person whom I heartily despised and hated ; and then, as

chance would have it, I was thrown two or three times into his

company ; and for motives of expediency I disguised my

antagonism. In the end, do you know, I found myself rather

liking him ?”

“Oh, women are fearfully and wonderfully made,” he

said.

“And so are some men,” said she. “Could you oblige me

with the name and address of a competent witch or warlock ?”

she added irrelevantly.

“What under the sun can you want with such an unholy

thing ?” he exclaimed.

“I want a hate-charm—something that I can take at night to

revive my hatred of the man I was speaking of.”

“Look here,” he warned her, “I’ve not come all this distance

under a scorching sun, to stand here now and talk of another

man. Cultivate a contemptuous indifference towards him. Banish

him from your mind and conversation.”

“I’ll try,” she consented ; “though if you were familiar with

the circumstances, you’d recognise a certain difficulty in doing

that.” She reached for her gloves, and began to put one on. “Will

you be so good as to tell me the time of day ?”

He

He looked at his watch. “It’s nowhere near time for you to

be moving yet.”

“You must not trifle about affairs of state,” she said. “At a

definite hour I have business at the palace.”

“Oh, for that matter, so have I. But it’s half-past four. To

call half-past four a definite hour would be to do a violence to the

language.”

“It is earlier than I thought,” she admitted, discontinuing her

operation with the glove.

He smiled approval. “Your heart is in the right place, after

all. It would have been inhuman to abandon me. Oh, yes,

pleasantry apart, I am in a condition of mind in which solitude

spells misery. And yet I am on speaking terms with but three

living people whose society I prefer to it.”

“You are indeed in sad case, then,” she compassionated him.

“But why should solitude spell misery ? A man of wit like you

should have plenty of resources within himself.”

“Am I a man of wit ?” he asked innocently.

Her eyes gleamed mischievously. “What is your opinion ?”

“I don’t know,” he reflected. “Perhaps I might have been, if

I had met a woman like you earlier in life.”

“At all events,” she laughed, “if you are not a man of wit, it

is not for lack of courage. But why does solitude spell misery ?

Have you great crimes upon your conscience ?”

“No, nothing so amusing. But when one is alone, one thinks ;

and when one thinks—that way madness lies.”

“Then do you never think when you are engaged in conversa-

tion ? : She raised her eyebrows questioningly.

“You should be able to judge of that by the quality of my

remarks. At any rate, I feel.”

“What do you feel ?”

“When

“When I am engaged in conversation with you, I feel a

general sense of agreeable stimulation ; and, in addition to that, at

this particular moment—— But are you sure you really wish to

know ?” he broke off.

“Yes, tell me,” she said, with curiosity.

“Well, then, a furious desire to smoke a cigarette.”

She laughed merrily. “I am so sorry I have no cigarettes to

offer you.”

“My pockets happen to be stuffed with them.”

“Then, do, please, light one.”

He produced his cigarette-case, but he seemed to hesitate about

lighting a cigarette.

“Have you no matches ?” she inquired.

“Yes, thank you, I have matches. I was only thinking.”

“It has become a solitude, then ?” she cried.

“It is a case of conscience, it is an ethical dilemma. How do

I know—the modern woman is capable of anything—how do I

know that you may not yourself be a smoker ? But if you are, it

will give you pain to see me enjoying my cigarette, while you are

without one.”

“It would be civil to begin by offering me one,” she suggested.

“That is exactly the liberty I dared not take—oh, there are

limits to my boldness. But you have saved the situation.” And

he offered her his cigarette-case.

She shook her head. “Thank you, I don’t smoke.” And her

eyes were full of teasing laughter, so that he laughed too, as he

finally applied a match-flame to his cigarette. “But you may

allow me to examine your cigarette-case,” she went on. “It

looks like a pretty bit of silver.” And when he had handed it to

her, she exclaimed, “It is engraved with the royal arms.”

“Yes. Why not ?” said he.

“Does

“Does it belong to the King ?”

“It was a present from the King.”

“To you ? You are a friend of the King ?” she asked, with

some eagerness.

“I will not deceive you,” he replied. “No, not to me. The

King gave it to Hilary Clairevoix, the Constable of Bellefontaine;

and Hilary, who’s a careless fellow, left it lying about in his

music-room ; and I came along and pocketed it. It is a pretty

bit of silver, and I shall never restore it to its rightful owner, if I

can help it.”

“But you are a friend or the King’s,” she repeated, with

insistence.

“I have not that honour. Indeed, I have never seen him. I

am a friend of Hilary’s ; I am his guest. He has stayed with me

in England—I am an Englishman—and now I am returning his

visit.”

“That is well,” said she. “If you were a friend of the King,

you would be an enemy of mine.”

“Oh ?” he wondered. “Why is that ?”

“I hate the King,” she answered simply.

“Dear me, what a capacity you have for hating ! This is the

second hatred you have avowed within the hour. What has the

King done to displease you ?”

“You are an Englishman. Has our King’s reputation not

reached England yet ? He is the scandal of Europe. What has

he done ? But no—do not encourage me to speak of him. I

should grow too heated,” she said strenuously.

“On the contrary, I pray of you, go on,” urged Ferdinand

Augustus. “Your King is a character that interests me more

than you can think. His reputation has indeed reached England,

and I have conceived a great curiosity about him. One only

hears

hears vague rumours, to be sure, nothing specific ; but one has

learned to think of him as original and romantic. You know him.

Tell me a lot about him.”

“Oh, I do not know him personally. That is an affliction I

have as yet been spared.” Then, suddenly, “Mercy upon me,

what have I said !” she cried. “I must ‘knock wood,’ or the

evil spirits will bring me that mischance to-morrow.” And

she fervently tapped the bark of the tree beside her with her

knuckles.

Ferdinand Augustus laughed. “But if you do not know him

personally, why do you hate him ?”

“I know him very well by reputation. I know how he lives,

I know what he does and leaves undone. If you are curious

about him, ask your friend Hilary. He is the King’s foster-

brother. He could tell you stories,” she said meaningly.

“I have asked him. But Hilary’s lips are sealed. He depends

upon the King’s protection for his fortune, and the palace-walls

(I suppose he fears) have ears. But you can speak without danger.

He is the scandal of Europe ? There’s nothing I love like scandal.

Tell me all about him.”

“You have not come all this distance under a scorching sun,

to stand here now and talk of another man,” she reminded

him.

“Oh, but kings are different,” he argued. “Tell me about

your King.”

“I can tell you at once,” said she, “that our King is the

frankest egotist in two hemispheres. You have learned to

think of him as original and romantic ? No ; he is simply

intensely selfish and intensely silly. He is a King Do-Nothing,

a Roi Fainéant, who shirks and evades all the duties and respon-

sibilities of his position ; who builds extravagant châteaux in

remote

remote parts of the country, and hides in them, alone with a few

obscure companions ; who will never visit his capital, never show

his face to his subjects ; who takes no sort of interest in public

business or the welfare of his kingdom, and leaves the entire

government to his ministers ; who will not even hold a court, or

give balls or banquets ; who, in short, does nothing that a king

ought to do, and might, for all the good we get of him, be a mere

stranger in the land, a mere visitor, like yourself. So closely does

he seclude himself, that I doubt if there be a hundred people in the

whole country who have ever seen him, to know him. If he

travels from one place to another, it is always in the strictest

incognito, and those who then chance to meet him never have any

reason to suspect that he is not a private person. His very effigy

on the coin of the realm is reputed to be false, resembling him in

no wise. But I could go on for ever,” she said, bringing her

indictment to a termination.

“Really,” said Ferdinand Augustus, “I cannot see that you

have alleged anything very damaging. A Roi Fainéant ? But

every king of a modern constitutional state is, willy-nilly, that.

He can do nothing but sign bills which he generally disapproves

of, lay foundation-stones, set the fashion in hats, and bow and

look pleasant as he drives through the streets. He has no power

for good, and mighty little for evil. He is just a State Prisoner.

It seems to me that your particular King has shown some sense

in trying to escape so much as he may of the prison’s irksomeness.

I should call it rare bad luck to be born a king. Either you’ve

got to shirk your kingship, and then fair ladies dub you the scandal

of Europe ; or else you’ve got to accept it, and then you re as

happy as a man in a strait-waistcoat. And then, and then ! Oh,

I can think of a thousand unpleasantnesses attendant upon the

condition of a king. Your King, as I understand it, has said to

The Yellow Book—Vol. XIII. C

himself,

himself, ‘Hang it all, I didn’t ask to be born a king, but since

that is my misfortune, I will seek to mitigate it as much as I am

able. I am, on the whole, a human being, with a human life to

live, and only, probably, three-score-and-ten years in which to live

it. Very good ; I will live my life. I will lay no foundation-

stones, nor drive about the streets bowing and looking pleasant.

I will live my life, alone with the few people I find to my liking.

I will take the cash and let the credit go.’ I am bound to say,”

concluded Ferdinand Augustus, “that your King has done exactly

what I should have done in his place.”

“You will never, at least,” said she, “defend the shameful

manner in which he has behaved towards the Queen. It is for

that, I hate him. It is for that, that we, the Queen’s gentlewomen,

have adopted ‘Tis a weary day as a watchword. It will be a weary

day until we see the King on his knees at the Queen’s feet,

craving her forgiveness.”

“Oh ? What has he done to the Queen ?” asked Ferdinand.

“What has he done! Humiliated her as never woman was

humiliated before. He married her by proxy at her father’s court ;

and she was conducted with great pomp and circumstance into his

kingdom—to find what ? That he had fled to one of his absurd

castles in the north, and refused to see her ! He has remained

there ever since, hiding like—but there is nothing in created space

to compare him to. Is it the behaviour of a gentleman, of a

gallant man, not to say a king ?” she cried warmly, looking up

at him with shining eyes, her cheeks faintly flushed.

Ferdinand Augustus bowed. “The Queen is fortunate in her

advocate. I have not heard the King’s side of the story. I can,

however, imagine excuses for him. Suppose that his ministers,

for reasons of policy, importuned and importuned him to marry a

certain princess, until he yielded in mere fatigue. In that case,

why

why should he be bothered further ? Why should he add one to

the tedious complications of existence by meeting the bride he

never desired ? Is it not sufficient that, by his complaisance, she

should have gained the rank and title of a queen ? Besides, he

may be in love with another woman. Or perhaps—but who can

tell ? He may have twenty reasons. And anyhow, you cannot

deny to the situation the merit of being highly ridiculous. A

husband and wife who are not personally acquainted ! It is a

delicious commentary upon the whole system of marriages by

proxy. You confirm my notion that your King is original.”

“He may have twenty reasons,” answered she, “but he had

better have twenty terrors. It is perfectly certain that the Queen

will be revenged.”

“How so ?” asked Ferdinand Augustus.

“The Queen is young, high-spirited, moderately good-looking,

and unspeakably incensed. Trust a young, high-spirited, and

handsome woman, outraged by her husband, to know how to

avenge herself. Oh, some day he will see.”

“Ah, well, he must take his chances,” Ferdinand sighed.

“Perhaps he is liberal minded enough not to care.”

“I am far from meaning the vulgar revenge you fancy,” she

put in quickly. “The Queen’s revenge will be subtle and unex-

pected. She is no fool, and she will not rest until she has

achieved it. Oh, he will see !”

“I had imagined it was the curse of royalty to be without true

friends,” said Ferdinand Augustus. “The Queen has a very

ardent one in you.”

“I am afraid I cannot altogether acquit myself of interested

motives,” she disclaimed modestly. “I am of her Majesty’s

household, and my fortunes must rise and fall with hers. But I

am honestly indignantly with the King.”

“The

“The poor King ! Upon my soul, he has my sympathy,” said

Ferdinand.

“You are terribly ironical,” said she.

“Irony was ten thousand leagues from my intention,” he pro-

tested, “in all sincerity the object of your indignation has my

sympathy. I trust you will not consider it an impertinence if I

say that I already count you among the few people I have met

whose good opinion is a matter to be coveted.”

She had risen while he was speaking, and now she bobbed him

a little courtesy. “I will show my appreciation of yours by

taking flight before anything can happen to alter it,” she laughed,

moving away.

V

“You are singularly animated to-night,” said Hilary, contem-

plating him across the dinner-table ; “yet, at the same time,

singularly abstracted. You have the air of a man who is rolling

something pleasant under his tongue, something sweet and secret ;

it might be a hope, it might be a recollection. Where have you

passed the afternoon ? You’ve been about some mischief, I’ll

warrant. By Jove, you set me thinking. I’ll wager a penny

you’ve been having a bit of rational conversation with that brown-

haired woman.”

“Her hair is red,” Ferdinand Augustus rejoined, with firmness.

“And her conversation,” he added sadly, “is anything you please

but rational. She spent her whole time picking flaws in the charac-

ter of the King. She talked downright treason. She said he was

the scandal of Europe and the frankest egotist in two hemispheres.”

“Ah ? She appears to have some instinct for the correct use

of language,” commented Hilary.

“All

“All the same, I rather like her,” Ferdinand went on, “and

I’m half inclined to undertake her conversion. She has a gorgeous

figure—there’s something rich and voluptuous about it. And

there are depths of promise in her eyes ; there are worlds of

humour and of passion. And she has a mouth—oh, of a fulness,

of a softness, of a warmth ! And a chin, and a throat, and

hands ! And then, her voice. There’s a mellowness yet a

crispness, there’s a vibration, there’s a something in her voice that

assures you of a golden temperament beneath it. In short, I’m

half inclined to follow your advice, and go in for a love-adventure

with her.”

“Oh, but love-adventures—I have it on high authority—are

damnable iterations,” objected Hilary.

“That is very true ; they are,” Ferdinand agreed. “But the

life of man is woven of damnable iterations. Tell me of any

single thing that isn’t a damnable iteration, and I’ll give you a

quarter of my fortune. The day and the night, the seasons and

the years, the fair weather and the foul, breakfast and luncheon

and dinner—all are damnable iterations. If there’s any reality

behind the doctrine of metempsychosis, death, too, is a damnable

iteration. There’s no escaping damnable iterations : there’s

nothing new under the sun. But as long as one is alive, one

must do something. It’s sure to be something in its essence

identical with something one has done before ; but one must do

something. Why not, then, a love-adventure with a woman that

attracts you ?”

“Women are a pack of samenesses,” said Hilary despondently.

“Quite so,” assented Ferdinand. “Women, and men too,

are a pack of samenesses. We’re all struck with the same die, of

the same metal, at the same mint. Our resemblance is intrinsic,

fundamental ; our differences are accidental and skin-deep. We

have

have the same features, organs, dimensions, with but a hair’s-

breadth variation ; the same needs, instincts, propensities ; the

same hopes, fears, ideas. One man’s meat is another man’s meat ;

one man’s poison is another man’s poison. We are as like to one

another as the leaves on the same tree. Skin us, and (save for

your fat) the most skilled anatomist could never distingush you

from me. Women are a pack of samenesses ; but, hang it all,

one has got to make the best of a monotonous universe. And

this particular woman, with her red hair and her eyes, strikes me

as attractive. She has some fire in her composition, some fire

and flavour. Anyhow, she attracts me ; and—I think I shall try

my luck.”

“Oh, Nunky, Nunky,” murmured Hilary, shaking his head,

“I am shocked by your lack of principle. Have you forgotten

that you are a married man ?”

“That will be my safeguard. I can make love to her with a

clear conscience. If I were single, she might, justifiably enough,

form matrimonial expectations for herself.”

“Not if she knew you,” said Hilary.

“Ah, but she doesn’t know me—and shan’t,” said Ferdinand

Augustus. “I will take care of that.”

VI

And then, for what seemed to him an eternity, he never once

encountered her. Morning and afternoon, day after day, he

roamed the park of Bellefontaine from end to end, in all direc-

tions, but never once caught sight of so much as the flutter of her

garments. And the result was that he began to grow seriously

sentimental. “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai !” It was June,

to

to be sure ; but the meteorological influences were, for that, only

the more potent. He remembered her shining eyes now as not

merely whimsical and ardent, but as pensive, appealing, tender ;

he remembered her face as a face seen in starlight, ethereal and

mystic ; and her voice as low music, far away. He recalled their

last meeting as a treasure he had possessed and lost ; he blamed

himself for the frivolity of his talk and manner, and for the ineffec-

tual impression of him this must have left upon her. Perpetually

thinking of her, he. was perpetually sighing, perpetually suffering

strange, sudden, half painful, half delicious commotions in the

tissues of his heart. Every morning he rose with a replenished

fund of hope : this day at last would produce her. Every night

he went to bed pitying himself as bankrupt of hope. And all the

while, though he pined to talk of her, a curious bashfulness

withheld him ; so that, between him and Hilary, for quite a

fortnight she was not mentioned. It was Hilary who broke the

silence.

“Why so pale and wan?” Hilary asked him. “Will, when

looking well won’t move her, looking ill prevail ?”

“Oh, I am seriously love-sick,” cried Ferdinand Augustus,

welcoming the subject. “I went in for a sensation, and I’ve got

a real emotion.”

“Poor youth ! And she won’t look at you, I suppose ?” was

Hilary’s method of commiseration.

“I have not seen her for a mortal fortnight. She has com-

pletely vanished. And for the first time in my life I’m seriously

in love.”

“You’re incapable of being seriously in love,” said Hilary.

“I had always thought so myself,” admitted Ferdinand

Augustus. “The most I had ever felt for any woman was a sort

of mere lukewarm desire, a sort of mere meaningless titillation.

But

But this woman is different. She’s as different to other women

as wine is different to toast-and-water. She has the feu-sacré.

She’s done something to the very inmost soul of me ; she’s laid it

bare, and set it quivering and yearning. She’s made herself indis-

pensable to me ; I can’t live without her. Ah, you don’t know

what she’s like. She’s like some strange, beautiful, burning spirit.

Oh, for an hour with her, I’d give my kingdom. To touch her

hand—to look into those eyes of hers—to hear her speak to me !

I tell you squarely, if she’d have me, I’d throw up the whole

scheme of my existence, I’d fly with her to the uttermost ends of

the earth. But she has totally disappeared, and I can do nothing

to recover her without betraying my identity ; and that would

spoil everything. I want her to love me for myself, believing me

to be a plain man, like you or anybody. If she knew who I am,

how could I ever be sure ?”

“You are in a bad way,” said Hilary, looking at him with

amusement. “And yet, I’m gratified to see it. Her hair is not

so red as I could wish, but, after all, it’s reddish ; and you appear

to be genuinely aflame. It will do you no end of good ; it will

make a man of you—a plain man, like me or anybody. But your

impatience is not reasoned. A fortnight ? You have not met her

for a fortnight ? My dear, to a plain man a fortnight’s nothing.

It’s just an appetiser. Watch and wait, and you’ll meet her

before you know it. And now, if you will excuse me, I have

business in another quarter of the palace.”

Ferdinand Augustus, left to himself, went down into the

garden. It was a wonderful summer’s evening, made indeed (if

I may steal a phrase from Hilary) of perfumed velvet. The sun

had set an hour since, but the western sky was still splendid, like

a dark

a dark tapestry, with sombre reds and purples ; and in the east

hung the full moon, so brilliant, so apposite, as to seem somehow

almost like a piece of premeditated decoration. The waters of the

fountains flashed silverly in its light ; glossy leaves gave back dim

reflections ; here and there, embowered among the trees, white

statues gleamed ghost-like. Away in the park somewhere, in-

numerable frogs were croaking, croaking ; subdued by distance,

the sound gained a quality that was plaintive and unearthly. The

long façade of the palace lay obscure in shadow ; only at the far

end, in the Queen’s apartments, were the windows alight. But,

quite close at hand, the moon caught a corner of the terrace ; and

here, presently, Ferdinand Augustus became aware of a human

figure. A woman was standing alone by the balustrade, gazing

out into the wondrous night. Ferdinand Augustus’s heart began

to pound ; and it was a full minute before he could command him-

self sufficiently to move or speak.

At last, however, he approached her. “Good evening,” he

said, looking up from the pathway.

She glanced down at him, leaning upon the balustrade.

“Oh, how do you do ? She smiled her surprise. She was in

evening dress, a white robe embroidered with pearls, and she

wore a tiara of pearls in her hair. She had a light cloak thrown

over her shoulders, a little cape trimmed with swan’s-down.

“Heavens !” thought Ferdinand Augustus. “How magnificent

she is !”

“It’s a hundred years since I have seen you,” he said.

“Oh, is it so long as that ? I should have imagined it was

something like a fortnight. Time passes quickly.”

“That is a question of psychology. But now at last I find you

when I least expect you.”

“I have slipped out for a moment,” she explained, “to enjoy

this

this beautiful prospect. One has no such view from the Queen’s

end of the terrace. One cannot see the moon.”

“I cannot see the moon from where I am standing,” said he.

“No because you have turned your back upon it,” said she.

“I have chosen between two visions. If you were to authorise

me to join you, aloft there, I could see both.”

“I have no power to authorise you,” she laughed, “the terrace

is not my property. But if you choose to take the risks——”

“Oh,” he cried, “you are good, you are kind.” And in an in-

stant he had joined her on the terrace, and his heart was fluttering

wildly with its sense of her nearness to him. He could not speak.

“Well, now you can see the moon. Is it all your fancy

painted? “she asked, with her whimsical smile. Her face was

exquisitely pale in the moonlight, her eyes glowed. Her voice

was very soft.

His heart was fluttering wildly, poignantly. “Oh,” he began

—but broke off. His breath trembled. “I cannot speak,”

he said.

She arched her eyebrows. “Then we have made some mistake.

This will never be you, in that case.”

“Oh, yes, it is I. It is the other fellow, the gabbler, who is

not myself,” he contrived to tell her.

“You lead a double life, like the villain in the play?” she

suggested.

“You must have your laugh at my expense ; have it, and wel-

come. But I know what I know,” he said.

“What do you know ?” she asked quickly.

“I know that I am in love with you,” he answered.

“Oh, only that,” she said, with an air of relief.

“Only that. But that is a great deal. I know that I love

you—oh, yes, unutterably. If you could see yourself ! You are

absolutely

absolutely unique among women. I would never have believed it

possible for any woman to make me feel what you have made me

feel. I have never spoken like this to any woman in all my life.

Oh, you may laugh. It is the truth, upon my word of honour.

If you could look into your eyes,—yes, even when you are laugh-

ing at me ! I can see your wonderful burning spirit shining

deep, deep in your eyes. You do not dream how different you

are to other women. You are a wonderful burning poem. They

are platitudes. Oh, I love you unutterably. There has not been

an hour since I last saw you that I have not thought of you, loved

you, longed for you. And now here you stand, you yourself,

beside me ! If you could see into my heart, if you could see what

I feel !”

She looked at the moon, with a strange little smile, and was

silent.

“Will you not speak to me ?” he cried.

“What would you have me say?” she asked still looking

away.

“Oh, you know, you know what I would have you say.”

“I am afraid you will not like the only thing I can say.” She

turned, and met his eyes. “I am a married woman, and—I am

in love with my husband.”

Ferdinand Augustus stood aghast. “Oh, my God !” he

groaned.

“Yes, though he has given me little enough reason to do so, I

have fallen in love with him,” she went on pitilessly. “So you

must get over your fancy for me. After all, I am a total stranger

to you. You do not even know my name.”

“Will you tell me your name ?” asked Ferdinand humbly.

“It will be something to remember.”

“My name is Marguerite.”

“Marguerite !

“Marguerite ! Marguerite !” He repeated it caressingly. “It

is a beautiful name. But it is also the name of the Queen.”

“I am the only person named Marguerite in the Queen’s court,”

said she.

“What !” cried Ferdinand Augustus.

“Oh, it is a wise husband who knows his own wife,” laughed

she.

And then— But I think I have told enough.

Sonnets

By Richard Garnett, C.B., LL.D.

I

WITH thistle’s azure flower my home I hung,

And did with redolence of musk perfume,

And, robed in purple raiment’s glowing gloom,

Low prelude to my coming carol sung.

Spikenard, from Orient groves transported, clung

To brow and hand ; if so my humble room

Might undishonoured harbour her, for whom

Soon should its welcoming door be widely flung.

What princess, fairy, angel from above,

Some radiant sphere relinquishing for me,

Bowed to my habitation poor and cold ?

Princess nor sprite nor fay, but memory

Of thee it was that came to knock where Love

Expecting sat behind a gate of gold.

II

Royal I dream myself, and realm is mine

Isled far apart in Oriental seas,

Where night is lustrous glow and balmy peace,

And the fully moon doth on the waters shine.

Spices their aromatic breath consign

To lucid space untroubled by a breeze,

And ‘neath the shadow of the fringing trees

Gleams the light foamwork of the lipping brine.

There I in ivory pavillion keep,

And question with myself, and find no end ;

But thou, my Love, dost wander through the glade

Of sward secluse, where moon and night contend ;

Or couched beneath a palm dost taste of sleep,

Low at thy feet thy guardian lion laid.

III

When, hand in hand enlinked, we hie to fill

Our baskets with the valley’s modest flowers ;

Or at a bound the grassy crest is ours

Of the high mount, where dews are sparking still ;

Or, gazing from the solitary hill,

View the pale sea remote, as evening lours

And clouds, like ruins of fantastic towers,

Are piled and crumbled at the breeze’s will :

How oft doth silence seize on thee at once !

With light, whence caught who know ? thine eye is rife,

Thy

Thy clasped hand throbs in mine, thy bloom departs.

The water and the wind chant orisons ;

And the eternal poetry of life

Little by little steals into our hearts.

IV

May rose and lily on thy bosom shower !

And hymns triumphal peal around thy way !

Glory and peace to thee, whose spell doth sway

This captive soul submissive to thy power.

Sky dedicate her star, and earth her flower !

Shade, scent and song thy summons all obey !

Sea rol thee dreams from her resounding bay

When slow tides ripple in the moonlit hour !

Preserve no memory of me who weep ;

Be all my worship banished from thy thought ;

But should’st thou pass regardless by, the while

I sit lamenting, from my tears be wrought

A fragrant carpeting, a flowery heap

For thee to crush, or scatter with a smile.

V

O let her go, the bird of brood and nest

By wicked hands despoiled ! forth let her fare

On wings to the illimitable air

Dispread to waft her from the spot unblest.

The drifting bark that tempest from the west

Smote at aunsetting, let the billow bear

O’er the void deep, of mast and rudder bare,

Till the abyss engulf, let drive, ’tis best.

The

The spirit waning to its hour extreme,

That faith and joy and peace may never know,

Away with it to death without a dream !

The last faint notes that falter in the flow

Of dying strains, and dying hope’s last gleam,

Last breath, last love O—let them, let them go !

VI

Where at the precipice’s foot the wave

Ceaseless with sullen monotone doth roar,

And the wild wind flies plaining to the shore,

Be my dead heart committed to the grave.

There let the suns with fiery torrents lave

The parching dust, till summer shines no more,

And eddies of dry sand incessant soar

Around, when whirlblasts of the winter rave.

And with its own undoing be undone,

And with its viewless motes enforced to flit,

Rapt far away upon the hurricane,

All sighs and strifes that idly cumbered it,

And idlest Love, sunk to oblivion

In bosom of the barren bitter main.

VII

This sable steed, whose hoofs with clangour smite

My sense, while dreamful shade on earth is cast,

Onward in furious gallop thundering past

In the fantastic alleys of the night,

Whence

Whence cometh he ? What realms of gloom or light

Behind him lie ? Through what weird terrors last

Thus clothed in stormy grandeur sped so fast,

Dishevelling his mane with wild affright ?

A youth with mien of martial prowess, blent

With majesty no shock disquieteth,

Vested in steely armour sheening clear,

Fearless bestrides the terrible portent.

“I,” the tremendous steed declares, “am Death !”

“And I am Love !” responds the cavalier.

The Yellow Book—Vol. XIII. D

The Christ of Toro

By Mrs. Cunninghame Graham

I

The Prediction

VERY many centuries ago, when monastic life was as much a

life of the people as any other life, a man resolved to enter a

certain monastery in a small town of Castille. He had in his

time been many things. The son of a wealthy merchant, he had

spent much of his youth in Flanders, where he went at his

father’s bidding to purchase merchandise and to sell it. Instead

of devoting himself to the mysteries of trade, he learnt those or

painting from the most famous masters of the Low Countries.

His father dead, his father’s fame as one of the greatest merchants

of the day kept his credit going for some time, but at last he fell

into difficulties. Menaced with ruin, he became a soldier, and

fought under Ferdinand and Isabella before the walls of Granada.

His bravery procured him no reward, and he retired from the

wars and married. For a few years he was happy—at least he

knew he had been so when he knelt for the last time beside his

wife’s bier. And then he bethought himself of this monastery

that he had once seen casually on a summer’s day. There he

might

might find rest ; there end the turmoil of an unlucky and dis-

appointed life. He saw the quiet cloisters flooded with sunlight

looking out into the greenery of the monastery garden. He

heard the splashing of the drops from the fountain fall peacefully

on the hot silence. Nay, he even smelt the powerful scent of the

great myrtle bushes whose shadows fell blue and cool athwart the

burning alleys.

His servants’ tears fell fast as he distributed amongst them the

last fragments of his once immense fortune ; they fell faster when

they saw the solitary figure disappearing over the ridge of the

sandy path, for, although they knew not of his resolution, they

felt that they should see his face no more.

But we cannot escape from ourselves, even in the cloister.

There he felt the fires of an ambition that untoward circumstances

had chilled in his youth. The longing to leave some tangible

record of a life that he knew had been useless, fell upon him and

consumed him. He opened his mind to the prior. The prior

was a man of the world (there have always been such in the

cloister), and knew the workings of the human heart.

The monks began to whisper to each other that Brother

Sebastian was changed. Sometimes, at vespers, one or other

would look at him and note that his eyes had lost their

melancholy, and were as bright as stars. Then it got rumoured

about amongst them that he was painting a picture.

The monastery is, and especially a mediaeval one, full or

schisms and cabals. In it the rigour of the ultra-pietists who

stormed heaven by fire and sword, and whose hearts were shut to

all kindliness and charity, was to be found side by side with mild

and gentle spirits, who, through the gift of tears and ecstatic

revery, caught sight of the mystic and universal Bond of Love,

which, linked together in one common union, Nature, animal,

and

and sinner. To them all things palpitated in a Divine Mist of

Benignity and Tenderness—the terrorist and the rigorist on the

one hand ; on the other, serenity, charity, and compassion.

Now there was a certain Brother Matthias in this convent—

the hardest, bitterest zealot in the community, whom even his

own partisans looked at with dread. Of his birth little was

known, for all are equal in Religion, but the knotted joints of

his hairy hands, the hair which bristled black against his low

furrowed brow, were those of a peasant. No arm so strong or

merciless as his to wield the discipline on recalcitrant shoulders

(neither, it is fair to state, did he spare his own). The more

Blood the more Religion ; the more Blood the more Heaven.

He practised austerely all the theological virtues as far as his

lights and his mental capacity permitted, and it was as hard and

as stubborn as the clods which he had ploughed in his youth. He

did not despise, but bitterly loathed, all books or learning as the

works and lures of Satan. If he had had his will he would have

burnt the convent library long ago in the big cloister, all except

the Breviary and the offices therein contained. The liberal

Arts, and those who practised or had any skill in them, he would

fain have banished from the convent. The flowers even that

grew in the friars’ garden he neither smelt nor looked at. They

were beautiful, and Sin lurked in the heart of the rose, and all the

pleasures of the senses, and all the harmonies of sound. It was a

small, black, narrow world that mind of his, heaped up with the

impenetrable shadows of Ignorance, Intolerance, Contempt, and

Fear.

“Better he went and dug in the vineyard,” he would mutter

sourly, when he saw some studious Brother absorbed in a black-

letter Tome of Latinity in the monastery library. Once when

Fray Blas the sculptor had finished one of his elaborate crucifixes

of

or ivory, he had watched his opportunity and, seizing it un-

perceived in his brawny hand, waited until nightfall and threw it

into the convent well with the words, “Vade Retro ! Satanas !”

One day, as he passed through the corridor into which opened

Sebastian’s cell, his steps were arrested by the murmur or voices

which floated through the half-open door. He leaned against the

Gothic bay of the marble pillars that looked into the cloister

below, uncertain whether to go or stay. The hot sunlight filled

the dusky corridor with a drowsy sense of sleep and stillness.

The swallows flitted about the eaves, chirping as they wheeled

hither and thither with a throbbing murmur of content. The

roses climbed into the bay, lighting up the dusky corridors with

sprays of crimson ; they brushed against his habit. He beat

them off contemptuously. The eavesdropper could see nothing,

hear nothing, but what was framed in, or came through, that

half-open door.

Suddenly the two friars, the Prior and Fray Sebastian, were

startled by a tall figure framed suddenly in the doorway.

Blocking the light, it loomed on them like the gigantic and

menacing image of Elijah on the painted retablo of the High

Altar. Its face was livid. From underneath the black bushy

brows the eyes burned like coals of fire. The figure shook and

the hands twitched for a moment of speechless, unutterable

indignation. In that moment Sebastian turned, and placed

the canvas, which stood in the middle of the cell, with its

face against the wall, and the two men quietly faced their

antagonist.

Fray Matthias strode forward, as if to strike them.

“By Him that cursed the money-changers in the temple,” he

thundered, “what abomination is this ye have brewing in the

House of the Lord ? What new-fangled devilries are here ? This

is fasting, this is discipline, this is the prayer without ceasing ye

came here to perform. One holy monk daubing colours on a bit

of rag, and this reverend father, who should be the pattern and

exemplar of his community, aiding and abetting him !”

“Silence !” the Prior said. The one word was not ungently

spoken, but it was that of a man accustomed to command and to

be obeyed, and imposed on the coarse-grained peasant before him ;

nay, even left his burst of prophetic ire trembling on his tongue

unspoken. The Prior had drawn his slender figure up to its full

height ; a spot of red tinged his cheeks, as with quiet composure

he faced his aggressor. Never before had Matthias seen him as

lie was now, for he had always despised him for a timid, delicate,

effeminate soul, scarce fit to rule the turbulent world of the

convent. For a brief moment the Prior of Toro became again

that Count of Trevino who had led the troops of his noble house

to victory on more than one occasion, and whose gallant doings

even then were not quite forgotten in the court and world of

Spain. The habitual respect of the lowly-born for a man of

higher station and finer fibre asserted itself. He stood before his

Prior pale and downcast, like a frightened hound.

“Listen,” the prior continued. “Oh you, my brother, of little

charity. What you call zeal, I call malice. To you has been given

your talent. It led you to these convent walls. Develop it. To

this, my brother, and your brother, although you seem to know it

not, has been entrusted another talent. Who are you, to declaim

against the gifts of God ? There are talents, ay ! and even virtues,

that neither fructify to the owner nor to the world. Will you

have saved other men from sin or helped the sinner by your

flagellations and your fastings ? He who has so little kindness in

his heart, I fear me, would do neither. Yea, he would scarce save

them if he could. Nay, brother,” he added softly, “I doubt me

if

if ye would have done what He did.” Moving swiftly to the wall,

he turned the picture full on the gaze of the astounded brother.

“Behold Love !”

It was a marvellous picture, fresh and living from the brain of

its creator. Every speck of colour had been placed on with a hand

sure of its power. Christ nailed to the cross ; His hands and feet

seemed to palpitate as if still imbued with some mysterious vestiges

of life. The drops of blood which fell slowly down might have

been blood indeed. But it was in the face—not in the vivid

realism of the final scene of the tremendous drama—that the

beauty lay. One doubted if it did not retain some strange element

of life, some hidden vitality, rather felt than actually perceived,

under the pallid flesh. As the light flickered over them, one would

have said that the eyelids had not yet lost their power of con-

tractability, as if at any moment one would find them wide open

under the shadow of the brow ; the mouth seemed still fresh with

ghostly pleadings.

“Go, brother,” said the Prior, “and meditate, and when you

have learnt to do even such as this for your brethren, then turn

the money-changers from the hallowed temple. I tell you”—

and his face grew like one inspired—”I tell you this picture shall

yet save a soul, unbind the ropes of sin, and lead a tortured one to

heaven. Perhaps when we who stand here are gone,” he added

musingly. “Go, brother, and meditate.”

When the picture was finished and its frame ready, the sculp-

tured wood dazzling in its fresh gold and silver, on the day of St.

Christopher, borne high amidst a procession of the monks, it was

taken and hung up before the high altar.

Whether

Whether Brother Sebastian painted any more pictures ; whether

Brother Matthais learnt love and charity when they and the Prior

passed from the generations of men, the old chronicles which tell

the story omit to state, or whether they left any further record of

their lives in the convent beyond this scene which has been kept

alive by a monkish chronicler’s hand.

It is even a matter of doubt what cloister slab covers the dust

of the Count of Treviño, Prior of the Augustinian monastery of

Toro, or of Sebastian Gomez, the painter, or of Fray Matthias,

the peasant’s son.

But now comes the strange part of the relation, for the picture,

the miracle-working picture, is still to be seen in the monastery of

Toro. The Prior, the painter, the peasant died, but the picture

lived. For a century at least after their death it listened from its

station above the high altar to all the sounds of the monastery

church. Vespers trembled in the air before it and the roll of

midnight complines. It felt the priest’s voice strike against its

surface when he sanctified the sacrifice ; the shuffle of the monks’