The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume X July 1896

Contents

Literature

I. Dogs, Cats, Books, and the Average Man) By “The Yellow Dwarf”Page 11

II. An Idyll in

Millinery . Ménie Muriel Dowie . 24.

III. D’Outre tombe . . Rosamund

Marriott-Watson . . . . 54

IV. The

Invisible Prince . Henry Harland . . 59

V. An Emblem of Translation Richard Garnett, C.B., LL.D. . . . 88

VI. La Goya : a Passion of the Peruvian Desert Samuel Mathewson Scott 95

VII. Lady Loved a Rose . Renée de

Coutans . .167

VIII. Our River. .

. Mrs. Murray Hickson . 169

IX. Kathy . . . . Oswald

Sickert . . 179

X. Sub Tegmine

Fagi . . Marie Clothilde Balfour . 199

XI. Finger-Posts . . . Eva

Gore-Booth . . 214

XII. Lucretia .

. . . K. Douglas King . . 223

XIII. The Serjeant-at-Law . Francis

Watt . . . 245

XIV. Night and

Love . . Ernest Wentworth . . 259

XV.

Two Stories . . . Ella

D’Arcy . . . 265

XVI. Prince Alberic and

the Snake Lady Vernon Lee . . . 289

The Yellow Book—Vol. X—July, 1896

Art

Art

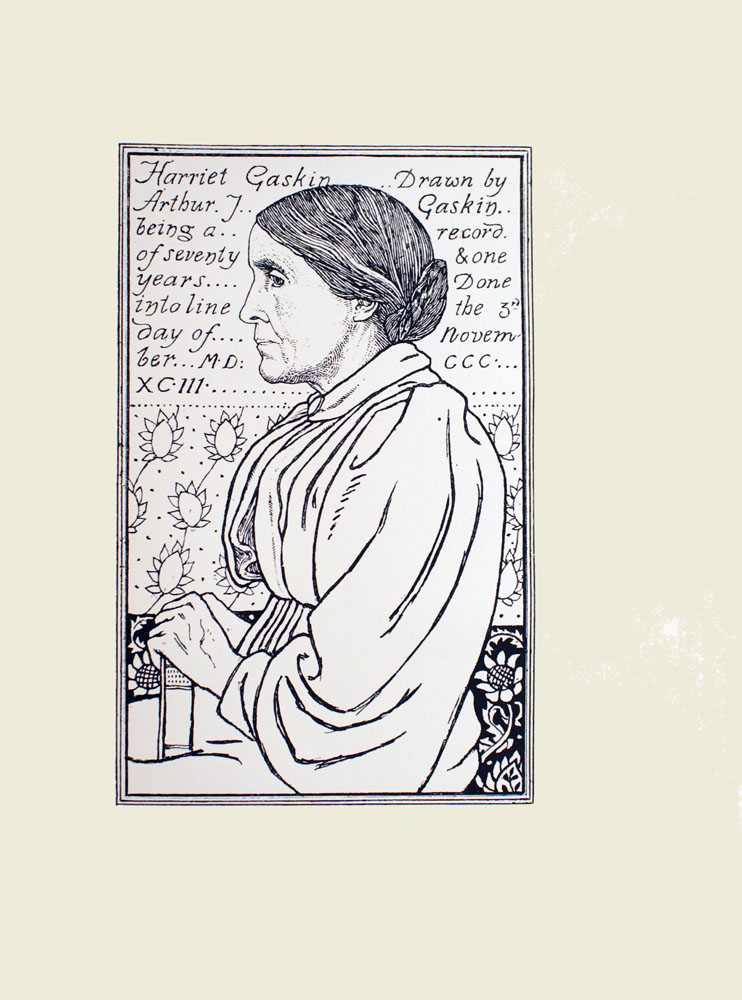

I. A Dutch Woman . . By Mrs.

Stanhope Forbes Page 7

II. Babies and

Brambles . Katharine Cameron . 55

III.

The Dew . .

IV. Ysighlu . J. Herbert

McNair . . 89

V. A Dream

VI. Mother and Child . Margaret Macdonald . 162

VII. Ill

Omen

VIII. The Sleeping Princess Frances Macdonald . 173

IX. Dieppe Castle . .

X. The Butterflies D. Y. Cameron . . 218

XI. The Five Sweet Symphonies Nellie Syrett . . . 256

XII. Barren Life . . . Laurence Housman

. 261

XIII. Windermere . .

. Charles Conder . . 286

The Title-page and Front Cover Design are

by J.

ILLINGWORTH KAY.

Dogs, Cats, Books, and

The Average Man

A Letter to the Editor

From “The Yellow Dwarf”

SIR :

I hope you will not suspect me of making a bid for his

affection, when I

remark that the Average Man loves the Obvious.

By consequence (for, like

all unthinking creatures, the duffer’s

logical), by consequence, his

attitude towards the Subtle, the

Elusive, when not an attitude of mere

torpid indifference, is an

attitude of positive distrust and dislike.

Of this ignoble fact, pretty nearly everything—from the

popularity

of beer and skittles, to the popularity of Mr. Hall

Caine’s novels ; from

the general’s distaste for caviare, to the

general’s neglect of Mr. Henry James’s tales—pretty nearly every-

thing

is a reminder. But, to go no further afield, for the moment,

than his own

hearthrug, may I ask you to consider a little the

relative positions

occupied in the Average Man’s regard by the

Dog and the Cat ?

The Average Man ostentatiously loves the Dog.

The Average Man, when he is not torpidly indifferent to that

princely

animal, positively distrusts and dislikes the Cat.

I have used the epithet “princely” with intention, in speaking

of

of the near relative of the King of Beasts. The Cat is a Princess

of the

Blood. Yes, my dear, always a Princess, though the

Average Man, with his

unerring instinct for the malappropriate

word, sometimes names her Thomas.

The Cat is always a

Princess, because everything nice in this world,

everything fine,

sensitive, distinguished, everything beautiful, everything

worth

while, is of essence Feminine, though it may be male by the

accident of sex ;—and that’s as true as gospel, let Mr. W. E.

Henley’s lusty young disciples shout their loudest in celebration

of the

Virile.—The Cat is a Princess.

The Dog, on the contrary, is not even a gentleman. Far

otherwise. His

admirers may do what they will to forget it, the

circumstance remains,

writ large in every Natural History, that

the Dog is sprung from quite the

meanest family of the Quad-

rupeds. That coward thief the wolf is his

bastard brother ; the

carrion hyena is his cousin-german. And in his

person, as in his

character, bears he not an hundred marks of his base

descent ? In

his rough coat (contrast it with the silken mantle of the

Cat) ; in

his harsh, monotonous voice (contrast it with the flexible organ

of

the Cat, her versatile mewings, chirrupings, and purrings, and

their innumerable shades and modulations) ; in the stiff-jointed

clumsiness of his movements (compare them to the inexpressible

grace and

suppleness of the Cat’s) ; briefly, in the all-pervading

plebeian

commonness that hangs about him like an atmosphere

(compare it to the

high-bred reserve and dignity that invest the

Cat). The wolf’s brother, is

the Dog not himself a coward ?

Watch him when, emulating the ruffian who

insults an un-

protected lady, he puts a Cat to flight in the streets :

watch him

when the lady halts and turns. Faugh, the craven ! with his

wild show of savagery so long as there is not the slightest danger

—and his sudden chopfallen drawing back when the lady halts and

turns !

turns ! The hyena’s cousin, is he not himself of carrion an

impassioned

amateur ? At Constantinople he serves ( ’tis a labour

of love ; he

receives no stipend) he serves as Public Scavenger,

swallowing with greed

the ordures cast by the Turk. Scripture

tells us to what he returneth :

who has failed to observe that he

returneth not to his own alone ? And the

other day, strolling

upon the sands by the illimitable sea, I came upon a

friend and

her pet terrier. She was holding the little beggar by the

scruff of

his neck, and giving him repeated sousings in a pool. I stood a

pleased spectator of this exercise, for the terrier kicked and

spluttered and appeared to be unhappy. “He found a decaying

jelly-fish

below there, and rolled in it,” my friend pathetically

explained. I should

like to see the Cat who could be induced to

roll in a decaying jelly-fish.

The Cat’s fastidiousness, her

meticulous cleanliness, the time and the

pains she bestows upon

her toilet, and her almost morbid delicacy about

certain more

private errands, are among the material indications of her

patrician

nature. It were needless to allude to the vile habits and

impudicity

of the Dog.

Have you ever met a Dog who wasn’t a bounder ? Have you

ever met a Dog who

wasn’t a bully, a sycophant, and a snob ?

Have you ever met a Cat who was

? Have you ever met a Cat

who would half frighten a timid little girl to

death, by rushing at

her and barking ? Have you ever met a Cat who, left

alone with

a visitor in your drawing-room, would truculently growl and

show

her teeth, as often as that visitor ventured to stir in his chair ?

Have you ever met a Cat who would snarl and snap at the

servants,

Mawster’s back being turned ? Have you ever met a

Cat who would cringe to

you and fawn to you, and kiss the hand

that smote her ?

Conscious of her high lineage, the Cat understands and accepts

the

the responsibilities that attach to it. She knows what she owes to

herself,

to her rank, to the Royal Idea. Therefore, it is you who

must be the

courtier. The Dog, poor-spirited toady, will study

your eye to divine your

mood, and slavishly adapt his own mood

and his behaviour to it. Not so the

Cat. As between you and

her, it is you who must do the toadying. A guest

in the house,

never a dependent, she remembers always the courtesy and the

consideration that are her due. You must respect her pleasure.

Is it

her pleasure to slumber, and do you disturb her : note the

disdainful

melancholy with which she silently comments your

rudeness. Is it her

pleasure to be grave : tempt her to frolic, you

will tempt in vain. Is it

her pleasure to be cold : nothing in

human possibility can win a caress

from her. Is it her pleasure to

be rid of your presence : only the

physical influence of a closed

door will persuade her to remain in the

room with you. It is

you who must be the courtier, and wait upon her

desire.

But then !

When, in her own good time, she chooses to unbend, how

graciously, how

entrancingly, she does it ! Oh, the thousand

wonderful lovelinesses and

surprises of her play ! The wit, the

humour, the imagination, that inform

it ! Her ruses, her false

leads, her sudden triumphs, her feigned despairs

! And the

topazes and emeralds that sparkle in her eyes ; the satiny

lustre of

her apparel ; the delicious sinuosities of her body ! And her

parenthetic interruptions of the game : to stride in regal progress

round the apartment, flourishing her tail like a banner : or

coquettishly

to throw herself in some enravishing posture at

length upon the carpet at

your feet : or (if she loves you) to leap

upon your shoulder, and press

her cheek to yours, and murmur

rapturous assurances of her passion ! To be

loved by a Princess !

Whosoever, from the Marquis de Carabas down, has

been loved

by

by a Cat, has savoured that felicity. My own particular treasure

of a Cat,

at this particular moment is lying wreathed about my

neck, watching my pen

as it moves along the paper, and purring

approbation of my views. But

when, from time to time, I

chance to use a word that doesn’t strike her

altogether as the

fittest, she reaches down her little velvet paw, and

dabs it out. I

should like to see the Dog who could do that.

But—the Cat is subtle, the Cat is elusive, the Cat is not to be

read

at a glance, the Cat is not a simple equation. And so the

Average Man,

gross mutton-devouring, money-grubbing mechan-

ism that he is, when he

doesn’t just torpidly tolerate her, distrusts

her and dislikes her. A

great soul, misappreciated, misunderstood,

she sits neglected in his

chimney-corner ; and the fatuous idgit

never guesses how she scorns him.

But—the Dog is obvious. Any fool can grasp the meaning of

the Dog.

And the Average Man, accordingly, recreant for once

to the snobbism which

is his religion, hugs the hyena’s cousin to his

bosom.

What of it ?

Only this : that in the Average Man’s sentimental attitude

towards the Dog

and the Cat, we have a formula, a symbol, for

his sentimental attitude

towards many things, especially for his

sentimental attitude towards

Books.

Some books, in their uncouthness, their awkwardness, their

boisterousness,

in their violation of the decencies of art, in their

low truckling to the

tastes of the purchaser, in their commonness,

their vulgarity, in their

total lack of suppleness and distinction,

are the very Dogs of Bookland.

The Average Man loves ’em.

Such as they are, they’re obvious.

And other books, by reason of their beauties and their virtues,

their

their graces and refinements ; because they are considered

finished ;

because they are delicate, distinguished, aristocratic ;

because their

touch is light, their movement deft and fleet ;

because they proceed by

omission, by implication and suggestion ;

because they employ the demi-mot and the nuance;

because, in

fine, they are Subtle—other books are the Cats of

Bookland.

And the Average Man hates them or ignores them.

Yes. Literature broadly divides itself into Cat-Literature,

despised and

rejected of the Average Man, and Dog-Literature,

adopted and petted by

him. What is more like the ponderous,

slow-strutting, dull-witted Mastiff,

than the writing of our

tedious friend Mr. Caine ? What more like a

formless, undipped

white Poodle, with pink eyes, than the gushing of Miss

Corelli ?

In the lucubrations of Mr. J. K. Jerome and his School, do we

not recognise the Dog of the Public House, grinning and

wagging his

tail and performing his round of inexpensive tricks

for whoso will chuck

him a biscuit ? And in the long-drawn

bellowings of Dr. Nordau, hear we

not the distempered Hound

complaining to the moon ? The books of Mr. Conan

Doyle are

as a litter of assorted Mongrels, going cheap—regardez moi leurs

pattes ! Mr. Anthony Hope produces the smart Fox

Terrier ;

Mr. George Moore, the laborious Dachshund ; whilst Messrs.

Crockett and MacLaren breed you the sanctimonious Collie.

To cross the

Channel, for an instant, we find the works of Mons.

Crapule Mendès, poking

their noses into whatever nastiness is

going, and doing the other usual

canine thing. And then, to

come back to England, and to turn our attention

upon Journal-

ism, we mustn’t forget Mr.

Punch’s collaborator Toby ; nor

Lo-Ben, the former ruling

spirit of the Pall Mall Gazette;

nor the

Jackals and Pariahs of Lower Grubb Street ; nor the

Butcher’s Dog, whose

carnivorous yawling is the predominant

note

note of a certain sixpenny weekly, which I will not advertise by

naming.

Cat-Literature, in the nature of things, it is less easy to put

one’s

finger on. Good books have such an unpleasant way of

being rare. Still, in

Paris, there are MM. France, Bourget, and

Pierre Loti (oh, that sweet

Pierre Loti, with his Moumoutte

Blanche and his Moumoutte Chinoise!); and,

in England, at

least two or three Literary Cats are born every year. There

are

many sorts of Cats, to be sure ; and some Cats are not so nice as

other Cats ; but even the shabbiest, drabbiest Cat, lurking in the

area, is interesting to those who have learned the Cat language,

and so

can commune with her. That is one of the prettiest

differences between the

Dog and the Cat :—the Dog will learn

your language, but you must

learn the Cat’s. Dog-Literature is

written in the language of the Average

Man, a crude, unlovely

language, necessarily. Cat-Literature is written in

a complex

shaded language all its own, which the Average Man is too stupid

or too indolent to learn.

Yes, even in poor old England, we may be thankful, a Literary

Cat is born

two or three times a year. Miss Dowie and Miss

D’Arcy, Mr. Grahame, Mrs.

Meynell, Mr. Crackanthorpe—they

are among the most careful and

successful of our native breeders.

Mr. Harland

has given us some very pretty Grey Kittens ; and

for the artificially

educated Cat, in green apron and periwig, we

naturally turn to Mr. Beerbohm — whose collected works, by

the

bye, I am glad to see have at last been published, accompanied

by a

charming Cat-like bibliography and preface from the hand of

Mr. Lane. But

of course, in any proper Cat Show, the Cats of

Mr. Henry James would carry off the special grand prix d’honneur.

And now, Mr. Editor, these philosophical

reflections may be

not inappositely punctuated by a piece of news.

I beg

I beg to announce to you the recent appearance in Cat-Literature

of a highly

curious and diverting sport or variation. Perhaps your

attention has

already been directed to it ? Have you seen March

Hares ?

March Hares, by George Forth, is a most spirited,

lithe-limbed,

and surprising Cat. It will mystify and irritate the Average

Man,

as much as it will rejoice his betters. He will discover that he

has been made a fool of, at the end of every bout ; for it is Cat’s

play perpetually—a malicious sequence of ruses and false leads.

He

will declare that it is madder even than its name, for the

method that

governs its capricious pirouettings is a method much

too subtle for his

coarse senses to apprehend. Indeed, I can almost

hope that March Hares was conceived and brought to parturition,

for the deliberate purpose of giving the Average Man a headache.

If

it were frank Opéra-bouffe, he wouldn’t mind ; but it is Opéra-

bouffe

masquerading as legitimate drama. The Average Man will

take it

seriously—and presently begin to stare and swear. He will

feel as

if Harlequin were circling round him, jeering at him and

flouting him,

making disrespectful gestures in his face, whacking

his skull with wooden

sword, and throwing his sluggish intellects

promiscuously into a whirl of

bewilderment and anger.

Mr. David Mosscrop, self-defined as an habitual criminal, is a

dissipated

young Scottish Professor of Culdees, who draws a salary

of four-hundred

odd pounds per annum, and, for forty-nine weeks

out of the fifty-two,

renders no equivalent of service. Accordingly,

he lives in chambers, at

Dunstan’s Inn, and lounges at seven

o’clock in the morning of his

thirtieth birthday, against the low

stone parapet of Westminster Bridge,

nursing a bad attack of

vapours, and wondering vaguely whether a chap “who

does not

know enough to keep sober over-night, should not be thrown like

garbage into the river.”

What

What more natural than that he should here encounter a young

lady “almost

tall,” with “butter-coloured hair,” and treat her to

an outfit of silk

stockings and a pair of patent-leather boots “of

the best Parisian make” ?

Inevitably, after that, he invites her to

breakfast at an Italian

ordinary, where she drinks freely of Chianti

and Maraschino, and lies to

him like fun about her identity and

her extraction. “My name is Vestalia

Peaussier. My father

was a French gentleman—an officer, and a man

of position. He

died—killed in a duel—when I was very young.

. . . . My

mother was the daughter of a very old Scottish house.” And

Vestalia has just been turned out of her lodgings for non-payment

of

rent, and insinuates that she is looking to the streets for a

career.

Mosscrop, properly enough shocked at this, hurries her away

upon his arm to

the British Museum, where he entertains her

with his ideas about Nero,

Richard Cœur de Lion, King John,

the Monkish Chroniclers, and the lions of

Assur-Banipal. She

listens, with her shoulder against his—” but now

he has other

auditors as well.”

” Excuse me, sir,” the urgent and anxious voice of a stranger

says close

behind him, ” but you seem to be extraordinarily well

posted indeed on

these sculptures here. I hope you will not object

to my daughter and me

standing where we can hear your re-

marks.”

The stranger is Mr. Skinner, from Paris, Kentucky, U.S.A.

His daughter,

Adele, is a handsome girl with “coal-black tresses,”

who looks askance at

the “butter-coloured” locks of Vestalia

Peaussier.

Skinner persists in his advances. “I should delight, sir, to have

my

daughter be privileged to profit by your remarks.” David

speaks somewhat

abruptly : “You are certainly welcome, but it

The Yellow Book—Vol. X. B

happens

happens that I have finished my remarks, as you call them.”

Skinner

observes, and the reader will agree with him, that “that’s

too bad ;” for

David’s remarks were lively and instructive. And

Skinner, with a view to

mutual intellectual improvement, asks

David to call upon him at the Savoy

Hotel.

Then David and Vestalia lunch together at the Café Royal,

drinking a bottle

of 34A, cooled to 48. And then they go to

Greenwich and eat fish. And at

last David conducts her to his

chambers, and sends her to bed in the room

of his absent neigh-

bour Linkhaw, supposed to be seeking recreation in

Uganda, or

“maybe in the Hudson Bay Territory.” And Linkhaw, in-

opportune villain, chooses, of course, this night of all nights for

playing the god from the machine. Footsteps come echoing up

the staircase.

A key rattles in Linkhaw’s lock. “Stop that, you

idiot !” David commands

fiercely. “Ah, Davie, Davie, still at

the bottle,” replies a well known

voice from out of the obscurity ;

and Linkhaw is dragged by Davie into

Davie’s den.

From the advent of Linkhaw the plot thickens terribly, the

Cat’s play

becomes fast and furious. First of all, Linkhaw isn’t

Linkhaw, but the

Earl of Drumpipes, in the Peerage of Scotland.

And secondly, Vestalia

isn’t Vestalia, but Linkhaw’s thoroughly

bad lot of a wife, whom he

imagines “dead as a mackerel, thank

God.” And thirdly, she isn’t either,

but the entirely virtuous

niece of Mr. Skinner, who turns out to be a

renegade Englishman

himself. And Peaussier was only Skinner Gallicised !

Then the

question rises, Is Mosscrop a gentleman ? Drumpipes, with

northern caution, admits that he is “a professional man, a person

of

education.” It is certain, anyhow, that Drumpipes would be

blithe to make

a Countess of Miss Skinner : she is rich, and she

is pleasing. Her Popper

is in Standard oil. But there are

democratic prejudices against his title,

though David reminds him

that

that it is “nothing better than a Scottish title,” and Drainpipes

retorts

that the Pilliewillies were great lords in Slug-Angus

“before the

Campbells were ever heard of, or the Gordons had

learned not to eat their

cattle raw.” Whereupon they almost

come to blows about the compensation to

be paid for a ruined

“moosie.” After some persuasion, however, Mosscrop

good-

naturedly consents to assume his friend’s embarrassment, and

while Drumpipes, as Linkhaw, makes love to the dark Adele,

Mosscrop, as

Drumpipes, arranges a coaching-party, a luncheon,

and a

tableau—whereof he and Vestalia are the central figures.

Then the

waiter comes in with the tureen ; and the Cat’s play is

ended. Voilà as the French say, tout.

March Hares, by George Forth. Who is George Forth ?

I’ll bet half-a-sovereign that “George Forth” is a pseudonym,

and

that it covers at least two personalities, perhaps three or four.

If March Hares is not the child of a collaboration, then

my eye-

sight is beginning to fail. Who are the collaborators ? Oddly

enough, they are quite manifestly members of a group I have

never

professed to love—they are manifestly pupils of Mr. W. E.

Henley. I

can only gratefully suppose either that the Master’s

influence is waning,

or that the Publisher’s Adviser pruned their

manuscript, and the Printer’s

Reader put the finishing touches to

their proofs ; for Brutality is

absent. I saw it stated in a daily

paper, a week or so ago, that George

Forth was Mr. Harold

Frederic ; but that’s a rank

impossibility. Mr. Harold Frederic

has proved that he can cross Bulldogs

with Newfoundlands, that

he can write able, unreadable Illuminations in choice Americanese.

He could no more flitter

and flutter and coruscate, and turn

somersaults in mid-air, and fall

lightly on his feet, in the Cat-

fashion of George Forth, than he could

dance a hornpipe on the

point of a needle. It is barely conceivable that

Mr. Harold

Frederic

Frederic may have been one of the collaborators, but, in that case,

I’ll eat

my wig if the others didn’t mightily revise his “copy.”

Nenni-da ! George Forth were far more likely to be,

in some

degree, Mr. George Steevens—late of the P.M.G., much chastened

and improved. Perhaps he is also, in

some degree, Mr. Marriott

Watson ? And (cherchez la

femme) who knows that a lady may

not supply an element of his

composition ? But these are mere

conjectures. The long of it is and the

short of it is that I’m

devoured by curiosity ; and I’ll offer a bottle of

his favourite wine

to any fellow who’ll provide me with an authenic

version of George

Forth’s “real names.”

You will remember, Mr. Editor, the magnificent retort of the

French King to

the malapert counsellor who ventured to remind

him of that silly old Latin

saw about vox populi and vox

Dei.

With the same splendid and conclusive scorn might you and

I

dismiss the opinions of the Average Man—especially his opinions

about Dogs, Cats, and Books. So long as they remain his own,

and are

not shared by his superiors, they import as little as the

opinions of the

Average Dugong. But the tiresome thing is,

they are infectious ; and his

superiors are constantly exposed to

the danger of catching them. When he

speaks as an individual,

the Average Man only bores without convincing

you. But when

he speaks by the thousand, somehow or other, he is as like

as not

to set a fashion, or even to establish a tradition. He has

already

established a tradition about Dogs and Cats ; and nowadays he is

beginning to set the fashion about Books. Nice people are begin-

ning to accept his opinions upon this, the one subject above all

subjects

which he is least qualified to touch. I actually know

nice people who have

read Mr. Conan Doyle ! And I have

actually met nice people who do not read

Mr. Henry James !

And

And that is all the fault of the Average Man. Why can’t the

dunce be gagged

? Mr. James, for instance, has just published

a new volume of his

incomparable tales. Embarrassments ’tis

called.

Of course, it must be as a volume composed in Coptic

for the Average Man ;

but nice people would find it a casket of

inexpressible delights, if only

the Average Man could be silenced

long enough to let them hear of it. For

my part, I do what I

can. I remember the example of Martin Luther, and I

hurl my

ink-pot. But the Devil is still abroad in the world, seeking

whom he may devour ; and the Average Man will no doubt go

on

gabbling—the Devil take him !

I have the honour, dear Mr. Editor, to subscribe myself, as

ever,

Your obedient servant,

THE YELLOW

DWARF.

An Idyll in Millinery

I

THE actual reason why Liphook was there does not matter :

he was there, and

he was there for the second time within

a fortnight, and on each occasion,

as it happened, he was the only

man in the place—the only

man-customer in the place. A pale,

shaven young Jew passed sometimes about

the rooms, in the

background.

Liphook could not stand still ; the earliest sign of mental

excitement,

this ; if he paused for a moment in front of one of

the two console tables

and glanced into the big mirror, it was

only to turn the next second and

make a step or two this way

or that upon the spacious-sized,

vicious-patterned Axminster

carpet. His eye wandered, but not without a

mark of resolution

in its wandering—resolution not to wander

persistently in one

direction. First the partings in the curtains which

ran before

the windows seemed to attract him, and he glanced into the gay

grove of millinery that blossomed before the hungry eyes of

female

passers-by in the street. Sometimes he looked through

the archways that

led upon each hand to further salons in which

little groups of women,

customers and saleswomen, were collected.

sometimes

Sometimes his eye rested upon the seven or eight unemployed

shop-ladies who

stood behind the curtains, like spiders, and looked

with an almost

malevolent contemptuousness upon the street

starers who came not in to

buy, but lingered long, and seemed to

con the details of attractive

models. More than once, a group

in either of the rooms fascinated him for

full a minute. One

particularly, because its component parts declared

themselves so

quickly to his apprehension.

A young woman, with fringe carefully ordered to complete

formlessness and

fuzz, who now sat upon a chair and now rose

to regard herself in a glass

as she poised a confection of the toque

breed upon her head. With her, a friend, older, of identical

type,

but less serious mien, whose face pringled into vivacious

comment upon

each venture ; comment which of course Liphook

could not overhear. With

them both, an elder lady, to whom

the shopwoman, a person of clever dégagé manner and primrose

hair, principally

addressed herself; appealingly, confirmatively,.

rapturously,

critically—according to her ideas upon the hat in

question. In and

out of their neighbourhood moved a middle-

aged woman of French

appearance, short-necked, square-

shouldered, high-busted, with a keen

face of chamois leather

colour and a head to which the black hair seemed

to have been

permanently glued—Madame Félise herself. When she

threw

a word into the momentous discussion the eyes of the party

turned respectfully upon her ; each woman hearkened. Even

Liphook divined

that the girl was buying her trousseau millinery ;

the older sister, or

married friend, advising in crisp, humorous

fashion, the elder lady

controlling, deciding, voicing the great

essential laws of order,

obligation and convention ; the shop-

woman playing the pipes, the

dulcimer, the sackbut, the tabor or

the viol—Madame Félise the

while commanding with invisible

bâton

bâton her intangible orchestra ; directing distantly, but with

ineludable

authority, the very players upon the stage. At this

moment She turned to

him and his attention necessarily left the

group. How did he find this ?

Did he care for the immense

breadth in front ? Every one in Paris was

doing it. Wasn’t he

on the whole a little bit sick of

hydrangeas—every one, positively

every one, had hydrangeas just

now, and hydrangeas the size

of cauliflowers. He made replies; he assumed

a quiet interest,

not too strong to be in character ; he steered her away

from the

Parisian breadth in front, away from the hydrangeas, into a con-

sideration of something that rose very originally at the back and

had a ruche of watercresses to lie upon the hair, and

three

dahlias, and four distinct colours of tulle in aniline shades, one

over

the other, and an osprey, and a bird of Paradise, and a few paste

ornaments; and a convincing degree of chicin

its abandoned

hideousness. Then he took a turn down the room towards the

group aforesaid.

“It looks so fearfully married to have that tinsel

crown, don’t

you know !” the elder sister or youthful matron was saying.

“I

mean, it suggests dull calls, doesn’t it ? Dull people always have

tinsel crowns, haven’t you noticed ?

I don’t want to influence

you, but as I said before, I liked you in the

Paris model.”

Every hat over which you conspicuously hover at Félise’s,

becomes, on the

instant, a Paris model.

“So smart, Madam,” cut in the shop-lady. “And you can’t

have anything newer

than that rustic brim in shot straw with

just the little knot of gardenias

at the side. Oh I do think it

suits you !”

Liphook turned away. After all, he didn’t want to hear what

these poor,

silly, feeble people were saying ; he wanted to

look. . . .

“But

“But Jim always likes me so much in pale blue, that I think

—” began

the girl.

“Why not have just a little tiny knot of forget-me nots with

the gardenia. Oh, I’m shaw you’d like it.”

Thus flowed the oily current of the shop-lady, reaching his ear

as Liphook

returned down the room. He could look again in the

only direction that won

his eyes and his thoughts ; five minutes

had been killed ; there was time

left him yet, for She had just

been seized with the idea that something

with a little more brim

was really her style. After all, She craved no

more than to be

loose at Félise’s, amid the Spring models lit by a palely

ardent

town sun, and Harold’s cheque-book looming in the comfortable

shadow of his pocket.

At the back of each gilt and mirrored saloon was placed a

work-table—in the manner of all hat-shops—surrounded by chairs

in which, mostly with their backs to the shops sat the girls who

were making up millinery ; their ages anywhere from sixteen to

twenty-one.

Seldom did the construction of a masterpiece appear

to concern them ; but

they were spangling things ; deftly turning

loops into bows, curling

feathers, binding ospreys into close sheaves;

their heads all bent over

their work, their neat aprons tied with

tape bows at the back, their dull

hair half flowing and half coiled—

the inimitable manner of the

London work girl—their pale faces

dimly perceived as they turned

and whispered not too noisily: the

whole thing recalling the soft, quietly

murmurous groups of

pigeons in the streets gathered about the scatterings

of a cab-

horse’s nose-bag. Sometimes shop-girls with elaborately

distorted

hair came up and gave them disdainful-seeming orders ; but the

flock of sober little pigeons murmured and pecked at its work and

ruffled no plumage of tan-colour or slate. And one of them,

different from

the others—how Liphook’s eyes, in the brief looks

he

he allowed himself, ate up the details of her guise. Dressed in

something—dark-blue, it might have been—that fitted with a

difference over her plump little figure; a fine and wide lawn collar

spread over breast and shoulders ; a smooth head, with no tags and

ends

upon the pale, yellow-tinted brow ; a head as sleek and as

sweetly-coloured as the coat of the cupboard-mouse ; a face so

softly

indented by its features, so fleckless, so mat in its

flat tones,

so mignon in its delicate lack of prettiness as to be

irresistible.

Lips, a dull greyish-pink, but tenderly curved at the

pouting bow

and faithfully compressed at the dusk-downy

corners—terribly

conscientious little lips that seemed as if never

could they be kissed

to lighter humour. Eyes, with pale ash-coloured

fringes, neither

long nor greatly curved, but so shy-shaped as ever eyes

were ; eyes

that could only be imagined by Liphook, and he was sometimes

of mind that they were that vaporous Autumn blue ; and at other

times that they were liquid, brook-coloured hazel.

But this was the maddest obsession that was riding him ! A

London workgirl

in a West-end hat shop, a girl whose voice he had

never heard, near whom

he had never, could never, come. And

Heaven forbid he should come near

her; what did he want with

her ? Before Heaven, and all these hats and

mirrors, Viscount

Liphook could have sworn he wanted nothing of her. Yet

he loved

her completely, desperately, exclusively. What name was there for

this feeling other than the name of love ? Soiled with all ignoble

use, this name of love ; though to do him justice, Liphook was not

greatly

to blame in that matter. He was but little acquainted

with the word ; he

left it out of his affaires de cœur, and very

properly, for it did not enter into them. Still, his feeling for this

girl, his craving for the sound of her voice, his eye fascinated by

her

smallest movement, his yearning for the sense of her nearer

presence—novel, inexplicable as this all was, might it not be love?

He

He stood there ; quiet, inexpressive of face, in jealous hope of—

what next ? And then She claimed his attention—in a whisper

which

brought her head with its mahogany hair, and her face with

its ground-rice

surface, close to his ear. She said :

“You don’t mind five, eh? It’s a model—and—don’t you

think it

becomes me ? I do think this mushroom-coloured velvet

and just the three

green orchids divine—and it’s really very

quiet !”

He assented, careful to look critically at the hat—a clever mass

of

evilly-imagined, ill-assorted absurdities. He had looked too

long at that

work-table, at that figure, at that face—he dropped

into a

chair—let his stick fall between his knees and cast his eyes

to the

mirror-empanelled ceiling ; there the heads, and feet of the

passers-by

were seething grotesquely in a fashion that recalled the

Inferno of an old

engraving.

Well, it would be time to look again soon—ah ! she had risen ;

thank

goodness, not a tall woman—(She was five foot nine)—

small,

and indolent of outline.

“I’ll take it to the French milliner now, Madam, and she’ll pin

a pink rose

in for you to see !”

It was a shop-woman speaking to some customer, who with a

hat in her hand,

approached the work-table.

“If you please, Mam’zelle Mélanie,” she began, in a voice

meant to impress

the customer, ” would you pin in a rose for

Madam to try ? Madam thinks

the pansy rather old-looking—”

&c., &c., &c.”

The French milliner ; French, then ! And what a dear

innocent, young,

crusty little face ! what delicious surliness : the

little brown bear that

she was, growling and grumbling to do a

favour. Well, bless that

woman—and the pansy that looked old—

he knew her name ;

enough to recognise her by, enough to address

a note

a note to her—and it should be a note ! A note that would bring

out

a star in each grey eye—they were grey—after all. (The

grey

of a lingering, promising, but unbestowing twilight.)

Reflecting, but

unobservant, his glance left her face and focussed

the pale, fair, young

Jew, who was seated, in frock coat and hat,

gloating over a pocket-book

that had scraps of coloured silk

and velvet pinned in it. He recalled his

wandering senses.

” How much ? Eight ten?”

” Well, I’ve taken a little black thing as well ; it happens to be

very

reasonable. There, you don’t mind ?” Mrs. Percival always

went upon the

principle of appearing to be careful of other

people’s money ; she found

she got more of it that way.

“My dear !—as long as you are pleased ! ” It was weeks

since this

tone had been possible to him. He scribbled a cheque

and they got away.

” I know I’ve been an awful time, old boy,” said the mahogany-

haired one,

with rough good humour—the good humour of a vain

woman whose vanity

has been fed. “Are you coming ?”

“Er—no ; in fact, I’m going out of town, I shan’t see you for

a

bit—Oh, I wasn’t very badly bored, thanks.”

She made no comment on his reply to her question ; her coarsely

pretty face

hardly showed lines of relief, for it was not a mobile

face ; but she was

pleased.

“Glad you didn’t fret. I’d never dreamt you’d be so good

about shopping.

Yes, I’ll take a cab. There is a call for 12.30,

and I see it is nearly

one now.”

He put her into a nice-looking hansom, lifted his hat and

watched her drive

away. Then he turned and looked into the

gaudy windows. His feelings were

his own somehow, now that

She had left him. He smiled ; love warmed in

him. Was the

old pansy gone and the pink rose in its place ? Had she

pricked

those

those creamy yellow fingers in the doing of it ? No, she was

too deft.

Tired, flaccid little fingers ! Was he never to think

of anything or

anyone again, except Mam’zelle Mélanie ?

II

Now the mahogany-haired lady was not an actress : she was

nothing so common

as an actress ; she belonged to a mysterious

class, but little understood,

even if clearly realised, by the public. It

was not because she could not

that she did not act ; she had never

tried to, there had been no question

of capability—but she con-

sented to appear at a famous West-end

burlesque theatre, to

oblige the manager who was a personal friend of

long-standing.

She “went on” in the ball-room scene of a hoary but ever-

popular “musical comedy,” because there was—not a part—but

a pretty gown to be filled, and because she was surprisingly

handsome, and of very fine figure, and filled that gown amazingly

well.

The two guineas a week that came her way at “Treasury”

went a certain

distance in gloves and cab-fares, and the neces-

saries of life she had a

different means of supplying. Let her

position be understood : she was a

very respectable person : there

are degrees in respectability as in other

things ; there was no fear

of vulgar unpleasantnesses with her and her

admirers—if she had

them. Mr. John Holditch, the popular manager of

several

theatres had a real regard for her ; in private she called him

“Jock, old boy,” and he called her “Mill”—because he recollected

her début; but the public knew her as Miss

Mildred Metcalf, and

her lady comrades in the dressing-room as Mrs.

Percival, and it

was generally admitted by all concerned that she was

equally

satisfactory under any of these styles. Oh, it will have been

noticed

noticed and need not be insisted on, that Liphook called her

“my dear,” and

if it be not pushing the thing too far, I may add

that her mother spoke of

her as “our Florrie.”

Liphook was a rich man whose occupation, when he was in

town, was the

dividing of days between the club, his rooms in

Half Moon Street, his

mother’s house in Belgrave Square, and

Mrs. Percival’s abode in Manfield

Gardens, Kensington. The

only respect in which he differed from a thousand

men of his

class was, that he had visited the hat shop of Madame Félise,

in

the company of Mrs. Percival, and had conceived a genuine

passion

for a little French milliner who sewed spangles on to

snippets of

nothingness at a table in the back of the shop.

The note had been written, had been answered. This answer,

in fine,

sloping, uneducated French handwriting, upon thin,

lined, pink paper of

the foreign character, had given Liphook a

ridiculous amount of pleasure.

The club waiters, his mother’s

butler, his man in Half Moon Street, these

unimportant people

chiefly noted the uncontrollable bubbles of happiness

that floated

to the surface of his impassive English face during the days

that

followed the arrival of that answer. He didn’t think anything in

particular about it ; few men so open to the attractions of women

as

this incident proves him, think anything in particular at all,

least of

all, at so early a stage. He was not—for the sake of his

judges it

must be urged—meaning badly any more than he was

definitely meaning

well. He wasn’t meaning at all. He cannot

be blamed, either. The world is

responsible for this sense of

irresponsibility in men of the

world—who are the world’s sole

making. Herein he was true to type ;

in so far as he did not think

what the girl meant by her answer, type was

supported by

individual character. Liphook was not clever, and did not

think

much or with any success, on any subject. And if he had he

wouldn’t

wouldn’t have hit the real reason ; only experience would have

told him

that a French workgirl, from a love of pleasure and the

national measure

of shrewd practicality combined, never refuses

the chance of a nice

outing. She does not, like her English

sister, drag her virtue into the

question at all.

Never in his life, so it chanced, had Liphook gone forth to an

interview in

such a frame of mind as on the day he was to meet

Mélanie outside the

Argyll Baths in Great Marlboro’ Street at

ten minutes past seven. Apart

from the intoxicating perfume

that London seemed to breathe for him, and

the gold motes that

danced in the dull air, there was the unmistakable

resistant pres-

sure of the pavement against his feet (thus it seemed)

which is

seldom experienced twice in a lifetime ; in the lifetime of such

a

man as Liphook, usually never. The Argyll Baths, Great

Marlboro’

Street : what a curious place for the child to have

chosen, and she would

be standing there, pretending to look into

a shop window. Oh, of course,

there were no shop windows to

speak of in Great Marlboro’ Street. (He had

paced its whole

length several times since the arrival of the pink glazed

note).

What would she say ? What would she look like ? Her eyes,

drooped or raised frankly to his, for instance ? That she would

not greet

him with bold, meaning smile and common phrase he

knew—he felt.

Dreaming and speculating, but wearing the

calm leisured air of a gentleman

walking from one point to

another, he approached and—yes ! there

she was ! A scoop-

shaped hat rose above the cream-yellow brow ; a big

dotted veil

was loosely—was wonderfully—bound about it ; a

little black

cape covered the demure lawn collar; quite French bottines peeped

below the dark-blue skirt.

But—she was not alone, a man was

with her. A man whom, even at some

distance, he could discern

to be unwelcome and unexpected, the pale fair

young Jew

in

in dapper frock-coat and extravagantly curved over-shiny hat.

Loathsome-looking reptile he was, too, so thought Liphook as he

turned

abruptly with savage scrape of his veering foot upon the

pavement, up

Argyll Street. Perhaps she was getting rid of him;

it was only nine

minutes past seven, anyhow ; perhaps he would

be gone in a moment. Odious

beast ! In love with her, no

doubt ; how came it he had the wit to

recognise her indescribable

charm ? (Liphook never paused to wonder how

himself had

recognised it, though this was, in the circumstances, even

more

remarkable). Anyway, judging by that look he remembered, she

would not be unequal to rebuffing unwelcome attention.

Liphook walked as far as Hengler’s Circus and read the bills ;

the place

was in occupation, it being early in March. He studied

the bill from top

to bottom, then he turned slowly and retraced

his steps to the corner. Joy

! she was there and alone. His pace

quickened, his heart rose ; his face,

a handsome face, was strung to

lines of pride, of passionate anticipation.

He had greeted her ; he had heard her voice ; so soft—dear

Heaven !

so soft—in reply ; they had turned and were walking

towards Soho,

and he knew no word of what had passed.

“We will have a cab ; you will give me the pleasure of dining

with me. I

have arranged it. Allow me.” Perhaps these were

the first coherent words

that he said. Then they drove along and

he said inevitable, valueless

things in quick order, conscious of the

lovely interludes when her smooth

tones, now wood-sweet, now

with a harp-like thrilling timbre in them, again with the viol—or

was it the

lute-note?—a sharp dulcidity that made answer in him as

certainly

as the tuning-fork compels its octave from the rosewood

board. The folds

of the blue gown fell beside him ; the French

pointed feet, miraculously

short-toed, rested on the atrocious straw

mat of the wretched hansom his

blindness had brought him ; the

scoop-hat

scoop-hat knocked the wicked reeking lamp in the centre of the

cab ; the

dotted veil, tied as only a French hand can tie a veil,

made more

delectable the creams and twine-shades of the monoto-

nous-coloured kitten

face. They drove, they arrived somewhere,

they dined, and then of all

things, they went into a church, which

being open and permitting organ

music to exude from its smut-

blackened walls, seemed less like London

than any place they

might have sought.

And it happened to be a Catholic Church, and he—yes, he

actually

followed the pretty ways of her, near the grease-smeared

pecten shell with

its holy water, that stuck from a pillar : some

Church oyster not uprooted

from its ancient bed. And they sat

on prie-dieus, in the dim incense-savoured gloom ; little un-

aspiring lights seemed to be burning in dim places beyond ; and

sometimes

there were voices, and sometimes these ceased again

and music filled the

dream-swept world in which Liphook was

wrapped and veiled away. And they

talked—at least she talked,

low murmurous recital about herself and

her life, and every detail

sunk and expanded wondrously in the hot-bed of

Liphook’s abnor-

mally affected mind. The evening passed to night, and

people

stepped about, and doors closed with a hollow warning sound that

hinted at the end of lovely things, and they went out and he

left

her at a door which was the back entrance to Madame

Félise’s establishment

; but he had rolled back a grey lisle-thread

glove, and gathered an

inexpressibly precious memory from the

touch of that small hand that posed

roses instead of pansies all the

day.

And of course he was to see her again. He had heard all

about her. How a

year since she had been fetched from Paris at

the instance of Goldenmuth.

Goldenmuth was the fair young

Jewish man in the frock-coat and supremely

curved hat. He was

The Yellow Book—Vol. X. C

a “relative”

a “relative” of Madame Félise, and travelled for her, in a certain

sense,

in Paris. He had seen Mélanie in an obscure corner of the

Petit St. Thomas when paying an airy visit to a lady

in charge of

some department there. An idea had occurred to him ; in three

days he arrived and made a proposition. He had conceived the

plan of

transplanting this ideally French work-flower to the

London shop, and his

plan had been a success. Her simple,

shrewd, much-defined little character

clung to Mélanie in London,

as in Paris ; she had clever fingers, but

beyond all, her appearance

which Goldenmuth had the art to appreciate,

soft but marked and

unassailable by influence, told infinitely at that

unobtrusive but

conspicuous work-table.

Half mouse, half dove ; never to be vulgarised, never to be

destroyed.

Mélanie had a family, worthy épicier of Nantes, her

father ;

her mother, his invaluable book-keeper. Her sister Hortense,

cashier at the Restaurant des Trois Epées ; her sister Albertine,

in

the millinery like herself. Every detail delighted Liphook,

every word of

her rapid incorrect London English sank into his

mind ; in the

extraordinarily narrow circumscribed life that

Liphook had

lived—that all the Liphooks of the world usually

do live—a

little, naïvely-simple description of some quite different

life is apt to

sound surprisingly interesting, and if it comes from

the lips of your

Mélanie, why . . . . .

But previous to the glazed pink note, if Liphook had crystal-

lised any

floating ideas he might have had as to the nature

of the intimacy he

expected, they would have tallied in no

particular with the reality. In

his first letter had been certain

warmly-worded sentences ; at their first

interview when he had

interred two kisses below the lisle-thread glove, he

had incohe-

rently murmured something lover-like. It had been too dark to

see

see Mélanie’s face at the moment ; but when since, more than

once, he had

attempted similar avowals she had put her head on

one side, raised her

face, crinkled up the corners of the grey eyes,

and twisted quite

alarmingly the lilac-pink lips. So there wasn’t

much said about love or

any such thing. After all, he could see

her three or four times a week ;

on Sunday they often spent the

whole day together ; he could listen to her

prattle ; he was a

silent fellow himself, having never learnt to talk and

having

nothing to talk about ; he could, in hansoms and quiet places,

tuck her hand within his arm and beam affectionately into her

face,

and they grew always closer and closer to each other ; as

camarades, still only as camarades. She never spoke of Goldenmuth

except incidentally,

and then very briefly ; and Liphook, who had

since seen the man with her

in the street on two occasions, felt

very unanxious to introduce the

subject ; after all he knew more

than he wanted to about it, he said to

himself. It was obvious

enough. He had bought her two hats at Félise’s ;

he had begged

to do as much, and she had advised him which he should

purchase,

and on evenings together she had looked ravishing beneath them.

He knew many secrets of the hat trade ; he knew and delightedly

laughed over half a hundred fictions Mélanie exploded ; he was in

a fair

way to become a man-milliner ; even Goldenmuth could not

have talked more

trippingly of the concomitants of capotes.

One Sunday, when the sunniest of days had tempted them

down the river, he

came suddenly into the private room where

they were to lunch and found her

coquetting with her veil in

front of a big ugly mirror ; a mad sort of

impulse took him, he

gripped her arms to her side, nipped her easily off

the floor, bent

his head round the prickly fence of hat-brim and kissed

her several

times ; she laughed with the low, fluent gurgle of water

pushing

through a narrow passage. She said nothing, she only laughed.

Somehow

Somehow, it disorganised Liphook.

“Do you love me ? Do you love me ?” he asked rapidly, even

roughly, in the

only voice he could command, and he shook her a

little.

She put her head on one side and made that same sweet

crinkled-up kind of

moue moquante, then she spread her palms out

and shook them and laughed and ran away round the table.

“Est-ce que

je sais, moi ?” she cried in French. Liphook didn’t

speak. Oh, he

understood her all right, but he was getting him-

self a little in hand

first. A man like Liphook has none of the

art of life ; he can’t do

figure-skating among his emotions like

your nervous, artistic-minded,

intellectually trained man. After

that one outburst and the puzzlement

that succeeded it, he was

silent, until he remarked upon the waiter’s

slowness in bringing up

luncheon. But he had one thing quite clear in his

thick English

head, through which the blood was still whizzing and

singing.

He wanted to kiss her again badly ; he was going to kiss her

again at the first opportunity.

But, of course, when he wasn’t with her his mind varied in its

reflections.

For instance, he had come home one night from

dining at Aldershot—a

farewell dinner to his Colonel it was—

and he had actually caught

himself saying : “I must get out of

it,” meaning his affair with Mélanie.

That was pretty early on,

when it had still seemed, particularly after

being in the society

of worldly-wise friends who rarely, if ever, did

anything foolish,

much less emotional, that he was making an ass of

himself, or

was likely to if he didn’t “get out of it.” Now the thing had

assumed a different aspect. He could not give her up ; under no

circumstances could he contemplate giving her up ; well then,

why give her

up ? She was only a little thing in a hat shop, she

would do very much

better—yes, but, somehow he had a certain

feeling

feeling about her, he couldn’t—well, in point of fact, he loved

her

; hang it, he respected her ; he’d sooner be kicked out of his

Club than

say one word to her that he’d mind a fellow saying to

his sister.

Thus the Liphook of March, ’95, argued with the Liphook of

the past two and

thirty years !

III

Liphook’s position was awkward—all the other Liphooks in the

world

have said it was beastly awkward, supposing they could have

been made to

understand it. To many another kind of man this

little love story might

not have been inappropriate ; occurring in

the case of Liphook it was

nothing less than melancholy. Not that

he felt melancholy about it, no

indeed ; just sometimes, when he

happened to think how it was all going to

end, he had rather a

bad moment, but thanks to his nature and training he

did not

think often.

Meantime, he had sent a diamond heart to Mrs. Percival ; there

was more

sentiment about a heart than a horse-shoe ; women

looked at that kind of

thing, and she would feel that he wasn’t

cooling off ; so it had been a

heart. That secured him several more

weeks of freedom at any rate, and he

wouldn’t have the trouble of

putting notes in the fire. For on receiving

the diamond heart

Mrs. Percival behaved like a python after swallowing an

antelope ;

she was torpid in satiety, and no sign came from her.

But one morning Liphook got home to Half Moon Street after

his Turkish bath,

and heard that a gentleman was waiting to see

him.

“At least, hardly a gentleman, my lord ; I didn’t put him in

the library,”

explained the intuitive Sims.

Some

Some one from his tailor’s with so-called “new” patterns, no

doubt ;

well—

He walked straight into the room, never thinking, and he saw

Goldenmuth.

The man had an offensive orchid in his buttonhole.

To say that Liphook was

surprised is nothing ; he was astounded,

and too angry to call up any

expression whatever to his face ; he

was rigid with rage. What in hell had

Sims let the fellow in for ?

However, this was the last of Sims ; Sims

would go.

The oily little brute, with his odious hat in his hand, was speak-

ing ;

was saying something about being fortunate in finding his

lordship,

&c.

“Be good enough to tell me your business with me,” said

Liphook, with

undisguised savagery. Though he had asked him

to speak, he thought that

when her name was mentioned he would

have to choke him. His

rival—by gad, this little Jew beggar

was Liphook’s rival.

Goldenmuth hitched his sallow neck, as

leathery as a turtle’s, in his

high, burnished collar, and took his

pocket-book from his breast

pocket—which meant that he was

nervous, and forgot that he was not

calling upon a “wholesale

buyer,” to whom he would presently show a

pattern. He pressed

the book in both hands, and swayed forward on his

toes—swayed

into hurried speech.

“Being interested in a young lady whom your lordship has

honoured with your

attentions lately, I called to ‘ave a little

talk.” The man had an

indescribable accent, a detestable fluency,

a smile which nearly warranted

you in poisoning him, a manner

—! There was silence. Liphook waited

; the snap with

which he bit off four tough orange-coloured hairs from his

mous-

tache, sounded to him like the stroke of a hammer in the street.

Then an idea struck him. He put a question :

“What has it got to do with you ?”

“I am

“I am interested—”

“So am I. But I fail to see why you should mix yourself up

with my

affairs.”

“Madame Félise feels—”

“What’s she got to do with it?” Liphook tossed out his

remarks with the

nakedest brutality.

“The lady is in her employment and—”

“Look here ; say what you’ve got to say, or go,” burst from

Liphook, with

the rough bark of passion. He had his hands be-

hind his back ; he was

holding one with the other in the fear that

they might get away from him,

as it were. His face was still im-

mobile, but the crooks of two veins

between the temples and the

eye corners stood up upon the skin ; his

impassive blue eyes

harboured sullen hatred. He saw the whole thing. That

old

woman had sent her dirty messenger to corner him, to “ask his

intentions,” to get him to give himself away, to make some pro-

mise. It

was a kind of blackmail they had in view. The very

idea of such creatures

about Mélanie would have made him sick at

another time ; now he felt only

disgust, and the rising obstinacy

about committing himself at the unsavory

instance of Goldenmuth.

After all, they couldn’t take Mélanie from him ;

she was free, she

could go into another shop ; he could marry . . . .

Stop—

madness !

“Mademoiselle Mélanie is admitted to be most attractive—

others have

observed it—”

“You mean you have,” sneered Liphook ; in the most un-

gentlemanly manner,

it must be allowed.

“I must bring to the notice of your lordship,” said the Jew,

with the

deference of a man who knows he is getting his point,

“that so young as

Mademoiselle is, and so innocent, she is not

fitted to understand business

questions ; and her parents being at

a distance

a distance it falls to Madame Félise and myself to see that—

excuse

me, my lord, but we know what London is !—that her

youth is not

misled.”

“Who’s misleading her youth ?” Liphook burst out ; and his

schoolboy

language detracted nothing from the energy with which

he spoke. “You can

take my word here and now that she is in

every respect as innocent as I

found her. And now,” with a

sudden reining in of his voice, “we have had

enough of this talk.

If you are the lady’s guardians you may reassure

yourselves : I am

no more to her than a friend : I have not sought to be

any more.”

Liphook moved in conclusion of the interview.

“Your lordship is very obliging ; but I must point out that a

young and

ardent girl is likely, in the warmth of her affection, to

be

precipitate—that we would protect her from herself.”

“About this I have nothing to say, and will hear nothing,”

exclaimed

Liphook, hurriedly.

Goldenmuth used the national gesture ; he bent his right

elbow, turned his

right hand palm upwards and shook it softly to

and fro.

“Perhaps even I have noticed it. I am not insensible !”

Liphook had never heard a famous passage—he neither read nor

looked

at Shakespeare, so this remark merely incensed him.

“But,” went on the

Jew, “since she came to England—for I

brought her—I have

made myself her protector—”

“You’re a liar !” said Liphook, who was a very literal person.

“Oh, my lord !—I mean in the sense of being kind to her and

looking

after her, with Madame Félise’s entire approval ; so

when I noticed the

marked attentions of a gentleman like your

lordship—”

“You’re jealous,” put in Liphook, again quite inexcusably.

But it would be

impossible to over-estimate his contempt for this

man.

man. Belonging to the uneducated section of the upper class he

was a man of

the toughest prejudices on some points. One of

these was that all Jews

were mean, scurvy devils at bottom and

that no kind of consideration need

be shown them. Avoid them

as you would a serpent ; when you meet them,

crush them as you

would a serpent. He’d never put it into words ; but that

is

actually what poor Liphook thought, or at any rate it was the

dim

idea on which he acted.

“Your lordship is making a mistake,” said Goldenmuth with a

flush. “I am

not here in my own interest ; I am here to act on

behalf of the young

lady.” Had the heavens fallen ? In her

interest

? Then Mélanie ? Never ! As if a Thing like this

could speak the truth !

“Who sent you ?” Liphook always went to the point.

“Madame Félise and I talked it over and agreed that I should

make it

convenient to call. We have both a great regard for

Mademoiselle ; we feel

a responsibility—a responsibility to her

parents.”

What was all this about ? Liphook was too bewildered to

interrupt even.

“Naturally, we should like to see Mademoiselle in a position,

an assured

position for which she is every way suited.”

So it was as he thought. They wanted to rush a proposal.

Must he chaffer with them at all ?

“I can tell you that if I had anything to propose I should

write it to the

lady herself,” he said.

“We are not anxious to come between you. I may say I have

enquired—my interest in Mademoiselle has led me to enquire—

and Madame Félise and I think it would be in every way a

suitable

connection for her. Your lordship must feel that we

regard her as no

common girl ; she deserves to be lancéein the

right

right manner ; a settlement—an establishment—some indication

that the connection will be fairly permanent, or if not, that

suitable—

“Is that what you are driving at, you dog, you?”

cried

Liphook, illuminated at length and boiling with passion. “So

you want to sell her to me and take your blasted commission ?

Get out of

my house !” He grew suddenly quiet ; it was an

ominous change. “Get out,

this instant, before—

Goldenmuth was gone, the street door banged.

“God ! God !” breathed Liphook with his hand to his wet

brow, “what a

hellish business !”

* * * * *

It was nine o’clock when Liphook came in that night. He

did not know where

he had been, he believed he had had

something in the nature of dinner, but

he could not have said

exactly where he had had it.

Sims handed him a note.

He recognised a friend’s hand and read the four lines it

contained.

“When did Captain Throgmorton come, then ?”

“Came in about three to ‘alf past, my lord ; he asked me if

your lordship

had any engagement to-night, and said he would

wait at the Club till

quarter past eight and that he should dine at

the Blue Posts after that.”

“I see; well,” he reflected a moment, “Sims, pack my

hunting things, have

everything at St. Pancras in time for the ten

o’clock express, and,” he

reflected again, ” Sims, I want you to

take a note—no, never mind.

That’ll do.”

“V’ry good, my lord.”

Yes, he’d go. Jack Throgmorton was the most companionable

man in the

world—he was so silent. Liphook and he had been

at

at Sandhurst together, they had joined the same regiment. Lip-

hook had

sent in his papers rather than stand the fag of India ;

Throgmorton had

“taken his twelve hundred” rather than stand

the fag of anywhere. He was a

big heavy fellow with a marked

difficulty in breathing, also there was

fifteen stone of him. His

round eyes, like “bulls’-eyes,” the village

children’s best-loved

goodies, stuck out of a face rased to an even red

resentment.

He had the hounds somewhere in Bedfordshire. His friends liked

him enormously, so did his enemies. To say that he was stupid

does

not touch the fringe of a description of him. He had never

had a thought

of his own, nor an idea ; all the same, in any Club

quarrel, or in regard

to a point of procedure, his was an opinion

other men would willingly

stand by. At this moment in his

life, a blind instinct taught Liphook to

seek such society ; no one

could be said to sum up more

completely—perhaps because so

unconsciously—the outlook of

Liphook’s world, which of late he

had positively begun to forget. The

thing was bred into

Throgmorton by sheer, persistent sticking to the

strain, and it came

out of him again mechanically, automatically,

distilled through

his dim brain a triple essence. The kind of man clever

people

have found it quite useless to run down, for it has been proved

again and again that if he can only be propped up in the right

place

at the right moment, you’ll never find his equal inthat

place. Altogether, a handsome share in “the secret of

England’s

greatness” belongs to him. The two men met on the platform

beside a pile of kit-bags and suit cases, all with Viscount Liphook’s

name

upon them in careful uniformity. Sims might have had

the administration of

an empire’s affairs upon his mind, whereas

he was merely chaperoning more

boots and shirts than any one

man has a right to possess.

“You didn’t come last night,” said Captain Throgmorton, as

though

though he had only just realised the fact. He prefaced the re-

mark by his

favourite ejaculation which was “Harr-rr”— he pre-

faced every

remark with “Harr-rr”—on a cold day it was not

uninspiriting if

accompanied by a sharp stroke of the palms ; in

April it was felt to be

somewhat out of season. But Captain

Throgmorton merely used it as a means

of getting his breath and

his voice under way. “Pity,” he went on, without

noticing

Liphook’s silence ; “good bone.” This summed up the dinner

with its famous marrow-bones, at the Blue Posts.

They got in. Each opened a Morning Post. Over the top

of

this fascinating sheet they flung friendly brevities from time to

time.

“Shan’t have more than a couple more days to rattle ’em

about,” Captain

Throgmorton remarked, after half an hour’s

silence, and a glance at the

flying hedges.

Liphook began to come back into his world. After all it was

a comfortable

world. Yet had an angel for a time transfigured it,

ah dear ! how soft

that angel’s wings, if he might be folded within

them . . . . old world,

dear, bad old world, you might roll by.

They were coming home from hunting next day. Each man

bent ungainly in his

saddle ; their cords were splashed ; the going

had been heavy, and once it

had been hot as well, but only for a

while. Then they had hung about a

lot, and though they found

three times, they hadn’t killed. Liphook was

weary. When

Throgmorton stuck his crop under his thigh, hung his reins on

it, and lit a cigar, Liphook was looking up at the sky, where

dolorous clouds of solid purple splotched a background of orange,

flame-colour and rose. Throgmorton’s peppermint eye rolled

slowly round

when it left his cigar-tip ; he knew that when a

man—that is, a man

of Liphook’s sort is found staring at a thing

like the sunset there is a

screw loose somewhere.

“Wha’

“Wha’ is it, Harold ?” he said, on one side of his cigar.

Liphook made frank answer.

“What’s she done then?”

“Oh, Lord, it isn’t her.”

“‘Nother ?” said Jack, without any show of surprise, and got

his answer

again.

“What sort ?” This was very difficult, but Liphook shut his

eyes and flew

it.

“How old ?”

“Twenty,” said Liphook, and felt a rapture rising.

“Jack, man,” he exclaimed, under the influence or the flame

and rose, no

doubt, “what if I were to marry ?”

Throgmorton was not, as has been indicated, a person of fine

fibre. “Do,

and be done with ’em,” said he. And after all, as

far as it went, it was

sound enough advice.

“I mean marry her,” Liphook explained, and the explanation

cost him a

considerable expenditure of pluck.

An emotional man would have fallen off his horse—if the horse

would

have let him. Jack’s horse never would have let him.

Jack said nothing for

a moment ; his eye merely seemed to swell ;

then he put another question :

“Earl know about it ?”

“By George, I should say not!”

“Harr-rr.”

That meant that the point would be resolved in the curiously

composed brain

of Captain Throgmorton, and by common con-

sent not another word was said

on the matter.

Two

IV

Two days had gone by. Liphook’s comfortable sense of having

acted wisely in

coming out of town to think the thing over still

supported him, ridiculous

though it seems. For of course he was

no more able to think anything over

than a Hottentot. Think-

ing is not a natural process at all ; savage men

never knew of it,

and many people think it quite as dangerous as it is

unnatural. It

has become fashionable to learn thinking, and some forms of

education undertake to teach it ; but Liphook had never gone

through

those forms of education. After all, to understand Lip-

hook, one must

admit that he approximated quite as nearly to the

savage as to the

civilised and thinking man, if not more nearly.

His appetites and his

habits were mainly savage, and had he lived

in savage times he would not

have been touched by a kind of love

for which he was never intended, and

his trouble would not have

existed. However, he was as he was, and he was

thinking things

over ; that is, he was waiting and listening for the most

forceful of

his instincts to make itself heard, and he had crept like a

dumb

unreasoning animal into the burrow of his kind, making one last

effort to be of them. At the end of the week his loudest instinct

was

setting up a roar ; there could be no mistaking it. He loved

her. He could

not part from her ; he must get back to her ; he

must make her his and

carry her off.

“Sorry to be leaving you, Jack,” he said one morning at the

end of the

week. They were standing looking out of the hall door