THE VENTURE: An Annual of Art and Literature

THE VENTURE

LITERARY CONTENTS

The Intellectual Ecstasy. Edmund Gosse. . . . 1

The Valley of Rocks. Charles Marriott. . . . 3

Pierrot. Althea Gyles. . . . 8

In the New Oriental Department. W. B. Maxwell. . . . 9

The Immortal Hour. Alfred Noyes. . . . 14

The Skeleton. Edward Thomas. . . . 17

Otho and Poppaea. Arthur Symons. . . . 27

Customs of Publicity. Alice Meynell. . . . 32

A Sonnet on Love. (From the French of Claudius

Popelin.)

Maurice

Joy. . . . 39

The Last Journey. Netta Syrett. . . . 40

A Face in the Street. T Sturge Moore. . . . 55

Scene-Shifting. E. . . . 56

Via Vita Veritas. John Gray. . . . 62

The Ebony Box. R. Ellis Roberts. . . . 65

The Mystery of Time. Florence Farr. . . . 74

A Painter of a New Day. Cecil French. . . . 85

Two Songs. James A. Joyce. . . . 92

On staying at an Hotel with a Celebrated

Actress. Vincent

O’Sullivan. . . . 95

John de Waltham. A Fragment of a Play. Benjamin Swift. . . . 111

A Solution. Nora Murray Robertson. . . . 114

A Study in Bereavement. E. S. P. Haynes. . . . 131

Two Songs. Oliver Gogarty. . . . 138

A Tuscan Melody. Arthur Ransome. . . . 141

Two Worlds. From the

Danish of J.P. Jacobson. Hermione

Ramsden.. . . . 147

For the King. Claude Monroe. . . . 153

A Game of Confidences. Paul Creswick. . . . 154

Megalomania. Vincent O’Sullivan. . . . 161

Old Songs. Gordon Bottomley. . . . 165

Five Poems in Prose. Maurice Joy. . . . 176

Love. Maurice Joy. . . . 181

Rhapsodie Capriccioso. Christopher Sandeman. . . . 182

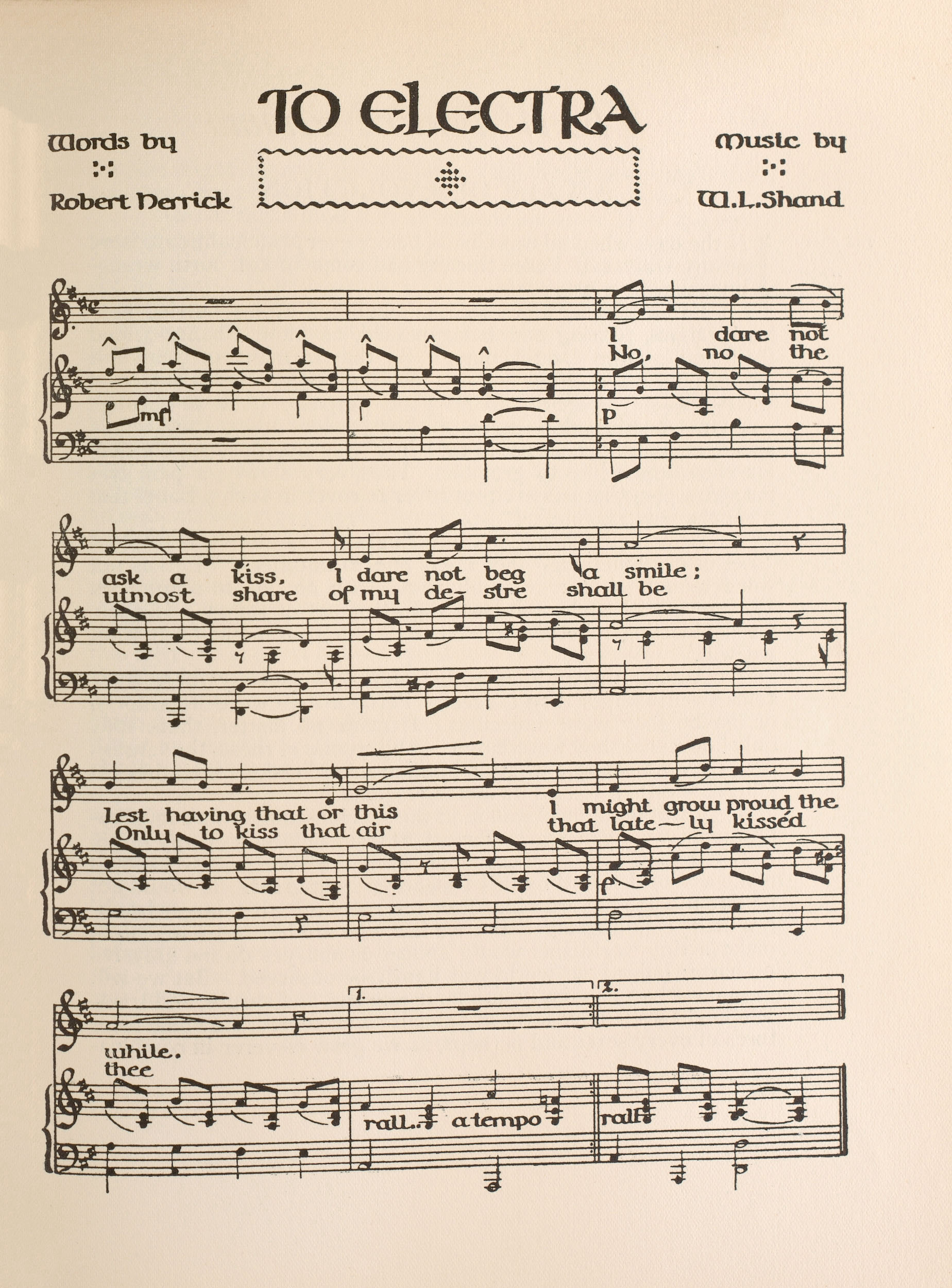

Herrick’s “I dare not ask a Kiss.” Set to Music by W.

L.

Shand. . . .

183

The Wayward Atom. Desmond F. T. Coke. . . . 184

Snake Charmer’s Song. Sarojini Naidu. . . . 188

ART CONTENTS

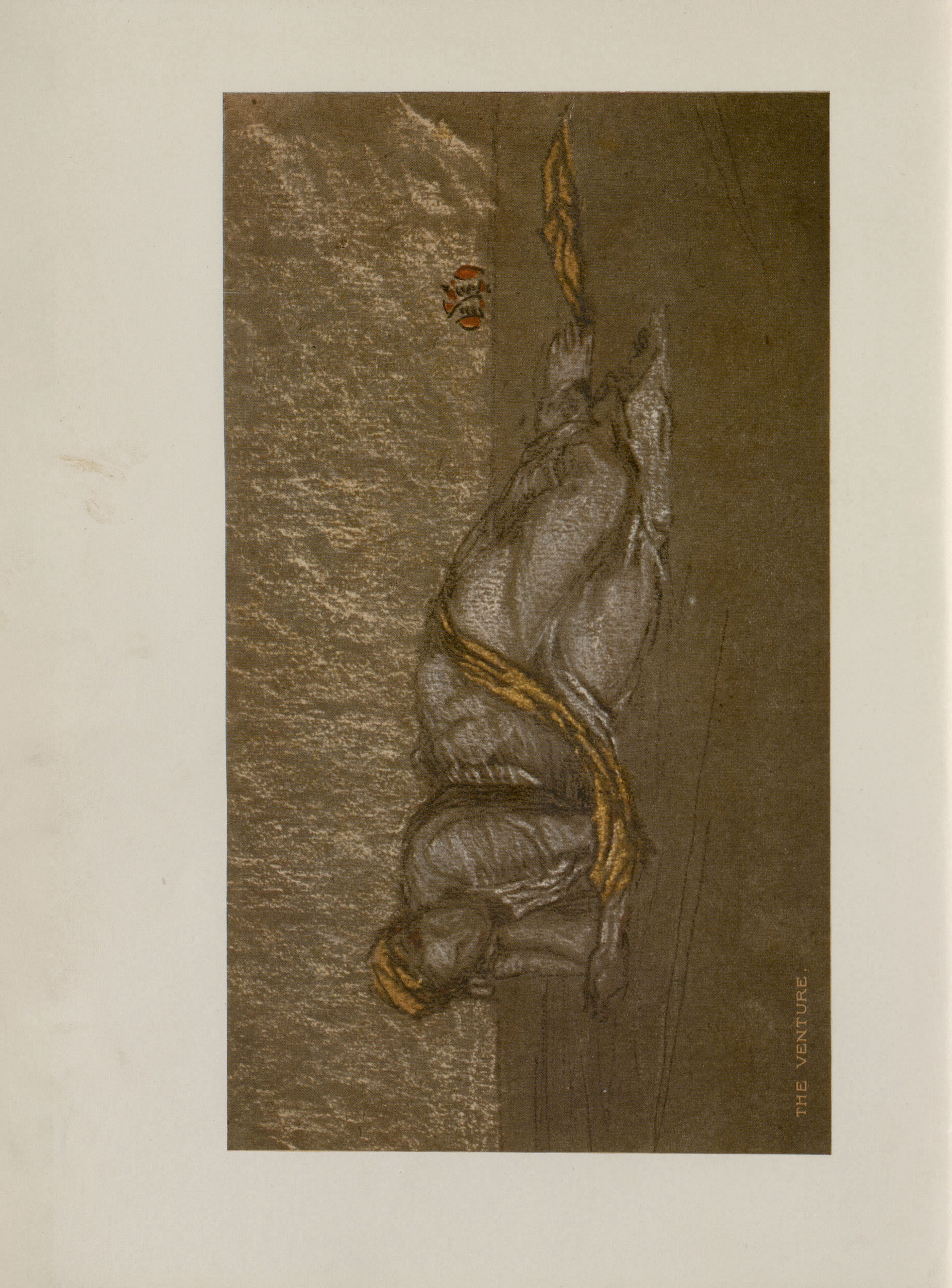

Arrangement in Brown and Gold. Facsimile in Colour.

J. McNeil

Whistler. . . .

Frontispiece

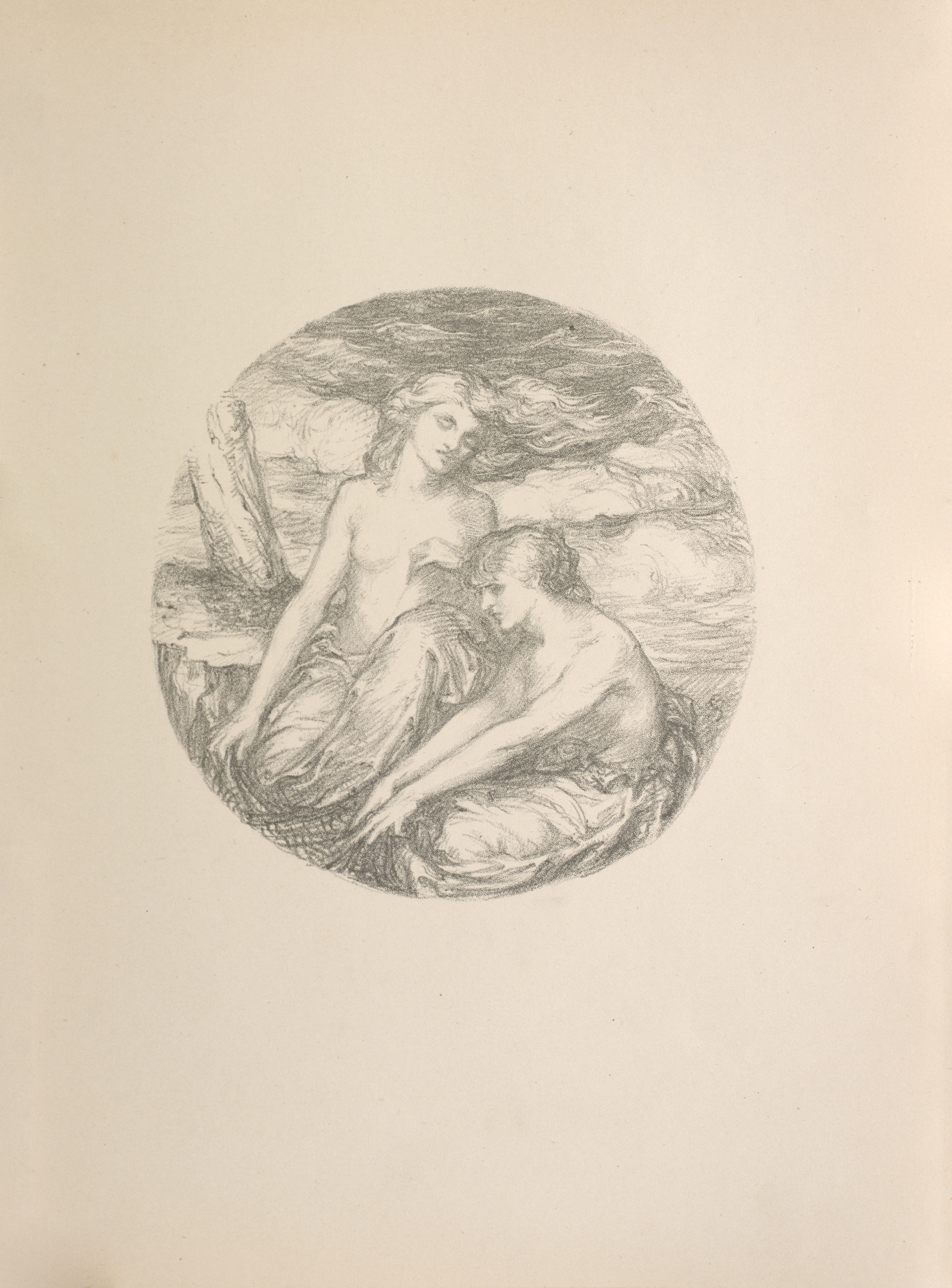

Tresses of the Surf. Lithograph. Clinton Balmer. . . . 1

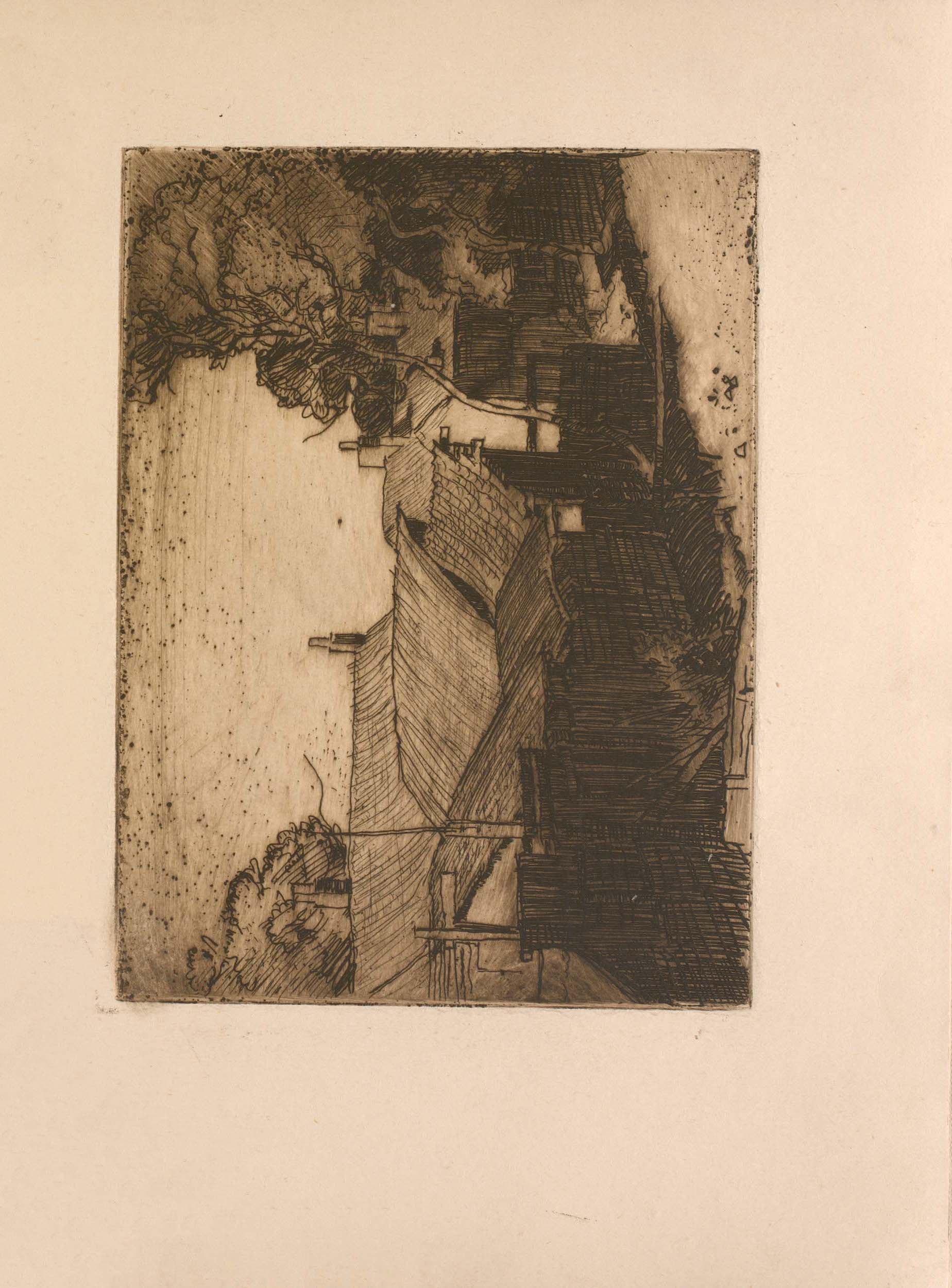

An Old Farm on the Outskirts of London. Etching. Frank

Brangwyn, A. R. A.

. . . 2

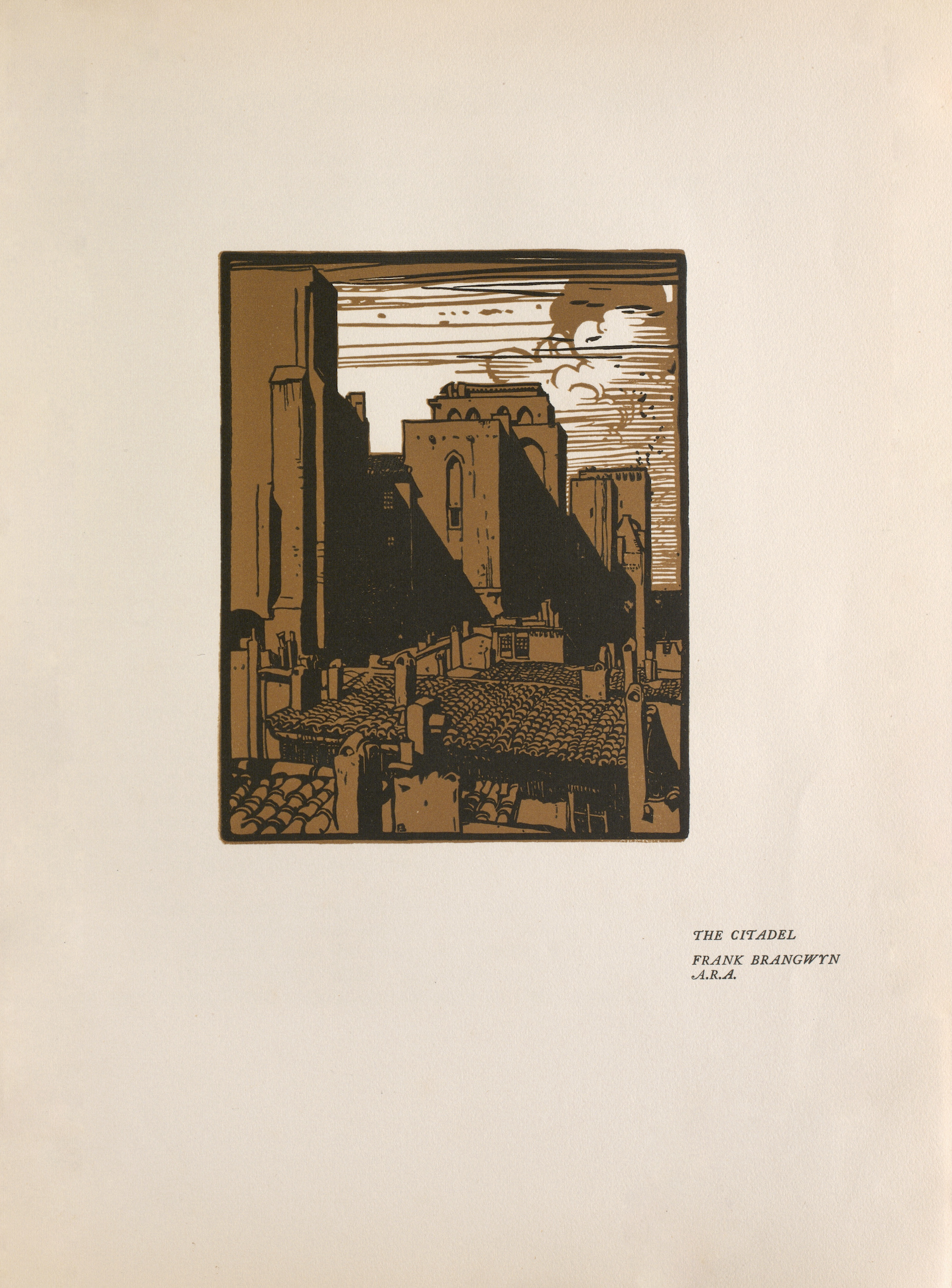

The Citadel. Woodcut in two colours. Frank Brangwyn. . . . 8

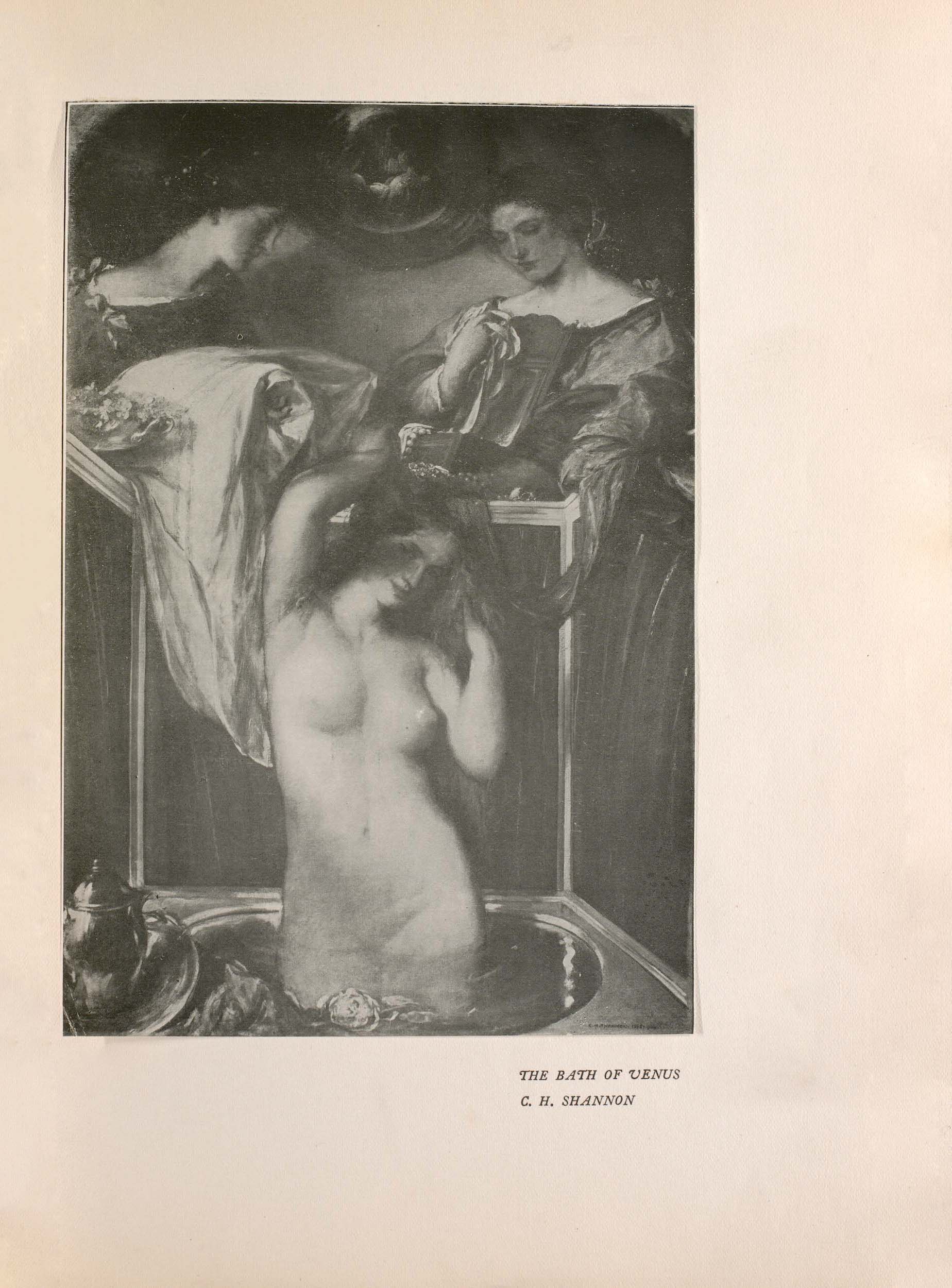

The Bath of Venus. Charles Hazelwood Shannon. . . . 15

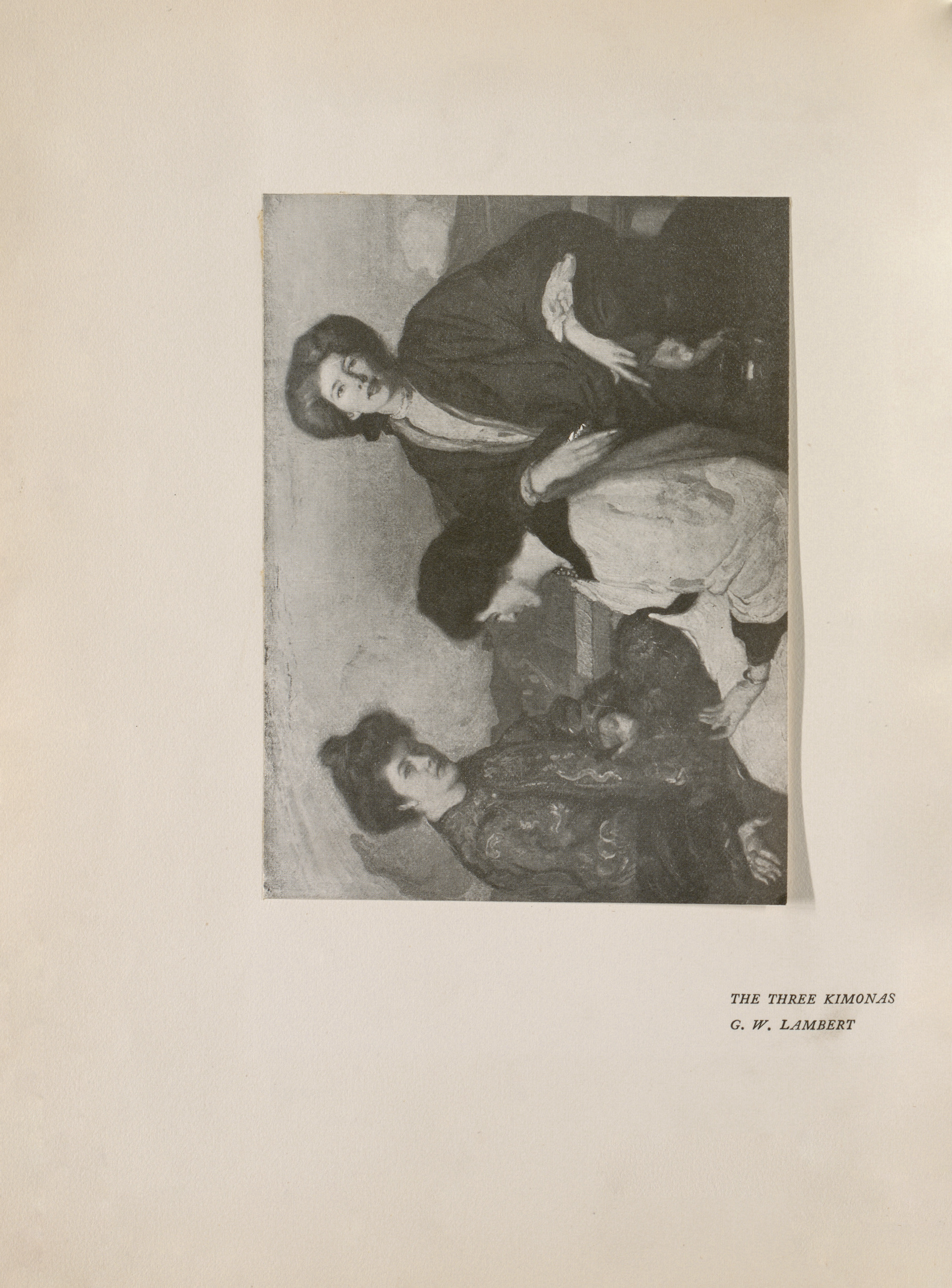

The Three Kimonas. G. W. Lambert. . . . 16

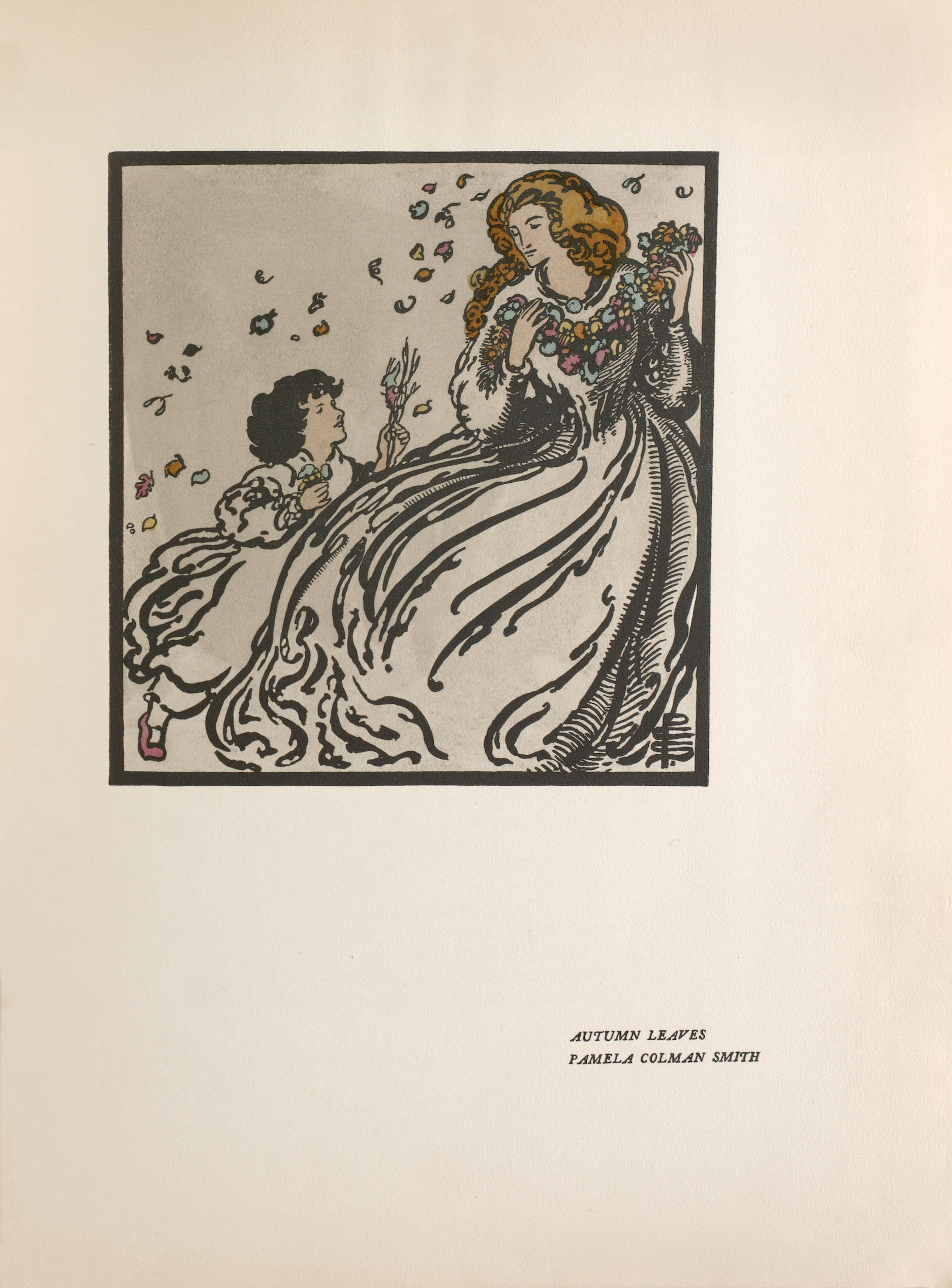

Autumn Leaves. Hand-Coloured Print. Pamela Colman

Smith. . . . 28

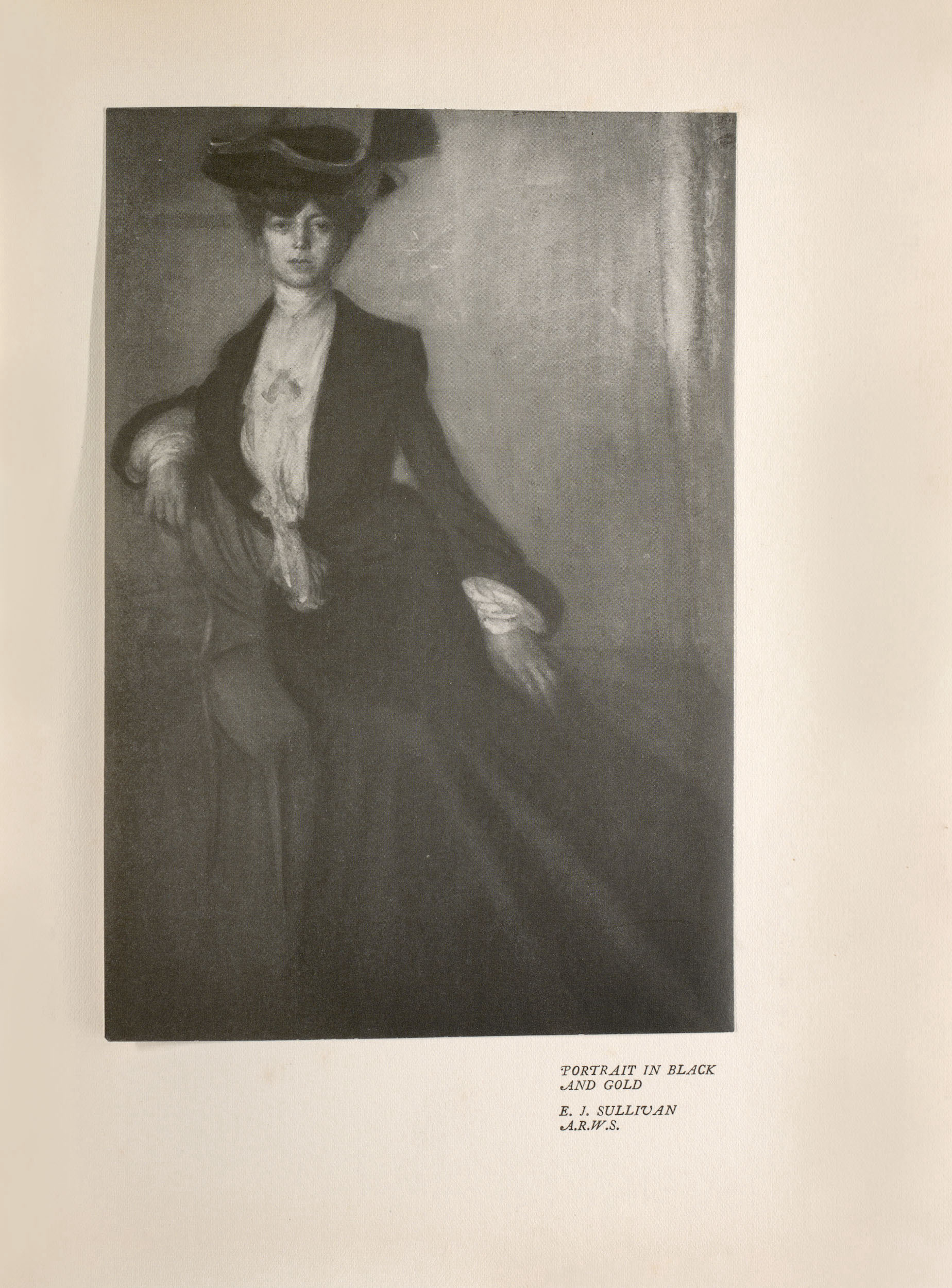

Portrait in Black and Gold. E.J. Sullivan, A. R. W. S. . . . . 34

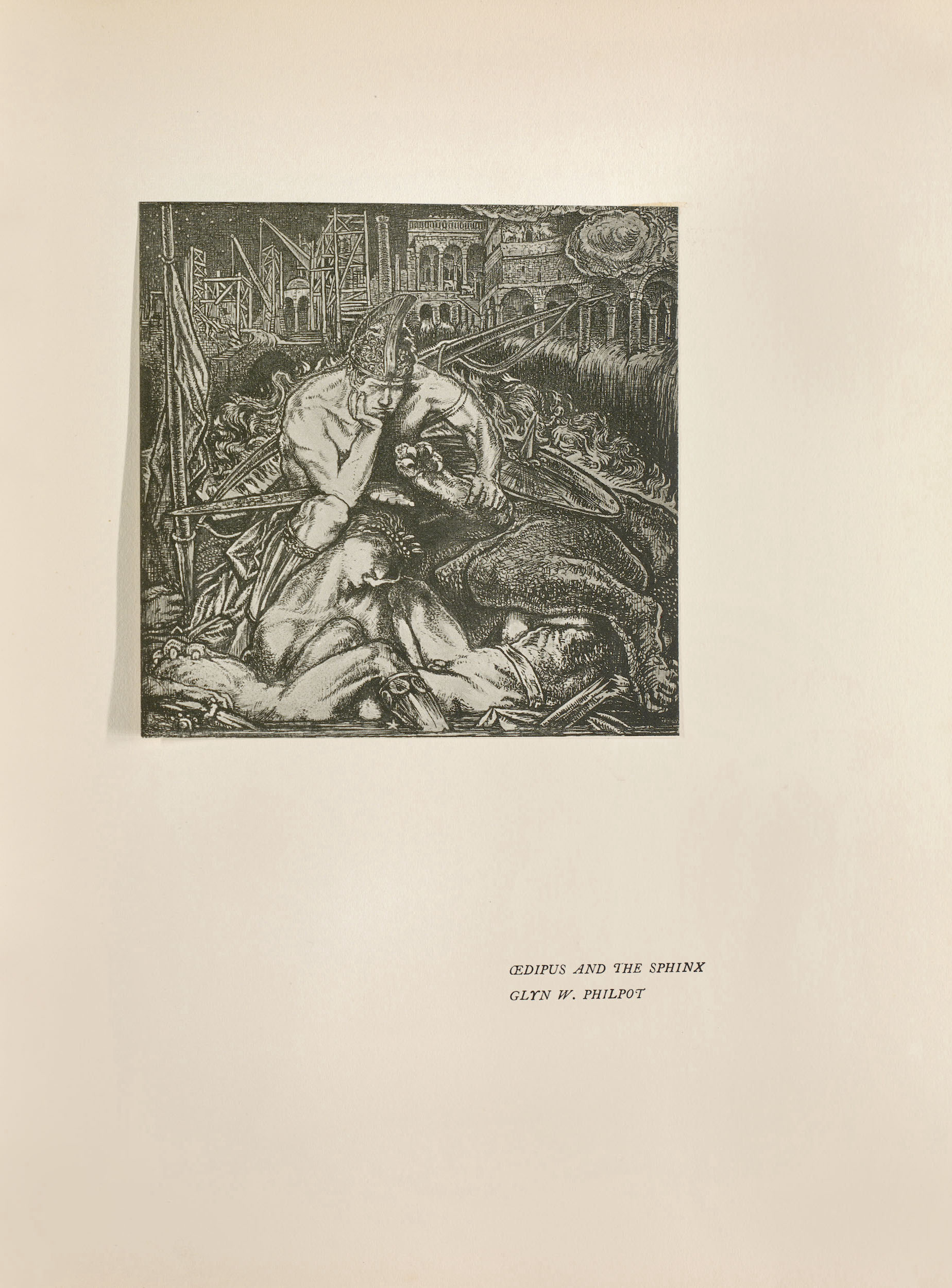

Œdipus and the Sphinx. Glyn W. Philpot. . . . 41

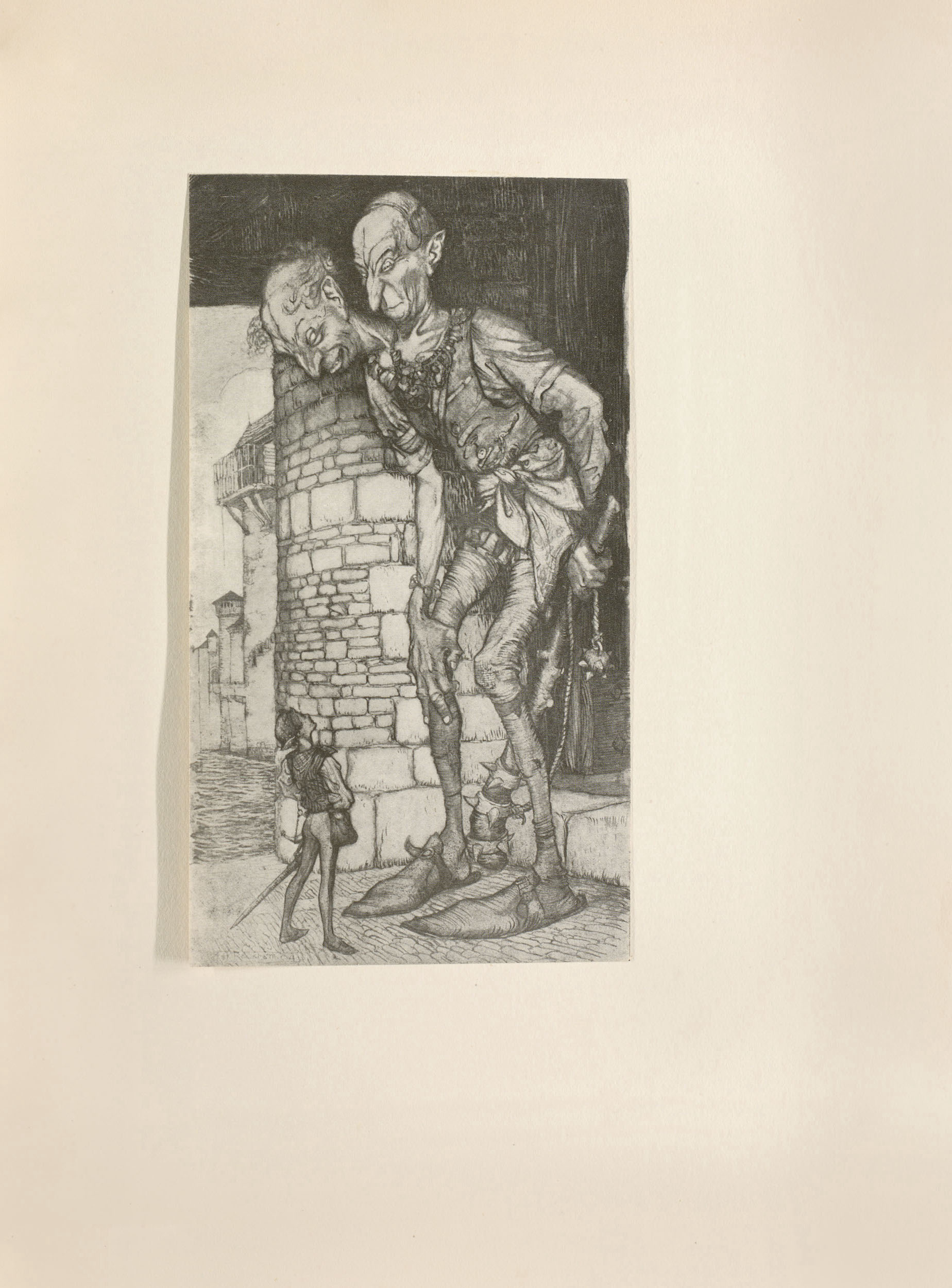

The Giant. Arthur Rackham, A. R. W. S. . . . 42

The Bath. W. Orpen. . . . 47

Chasse aux Amoureux. Walter Bayes, A. R. W. S. . . . 53

The Redemption. Photogravure. J. S. Sargent, R. A. . . . 64

The Little Child Found. F. Cayley Robinson. . . . 84

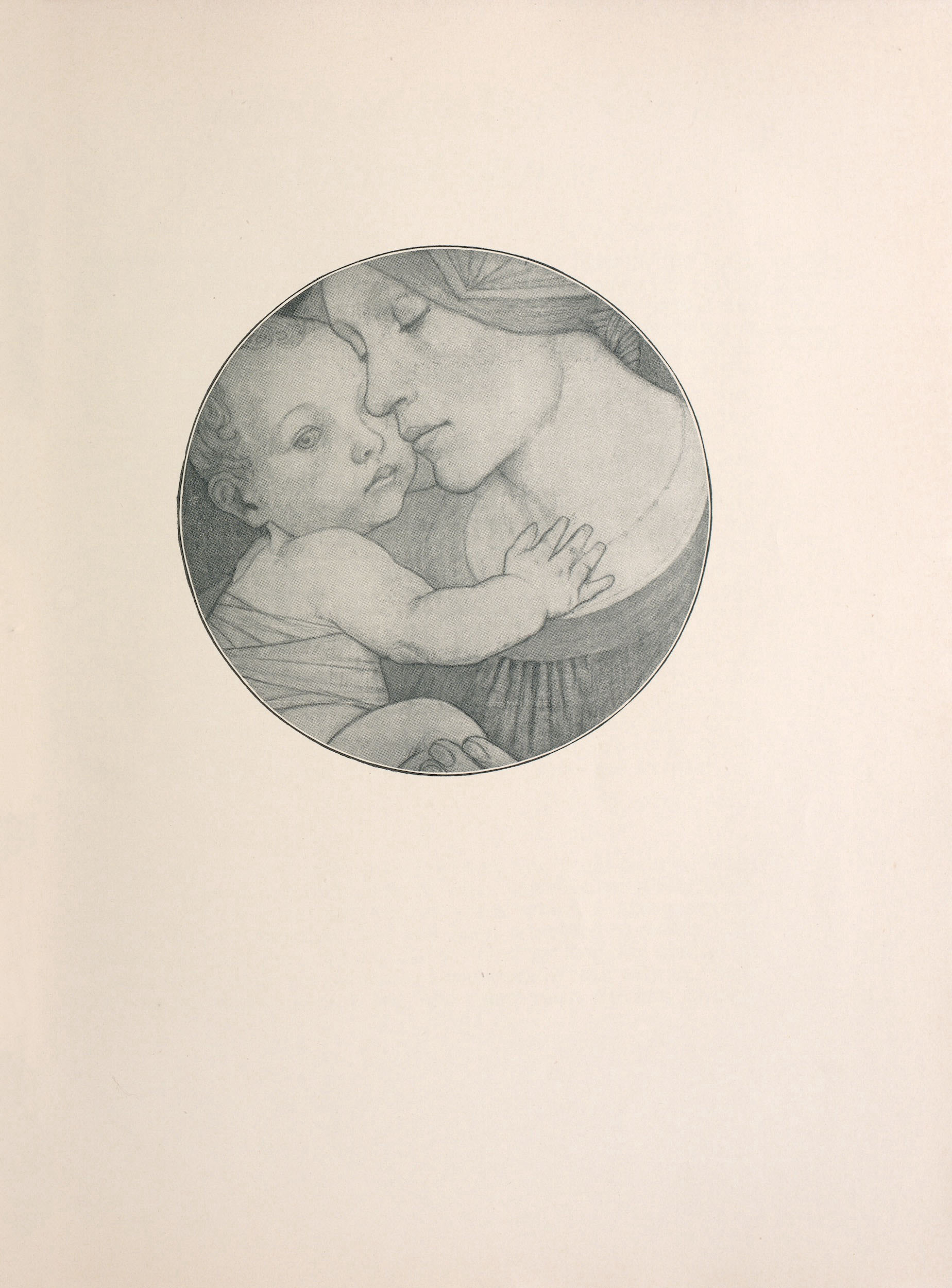

Mother and Child. Winifred Cayley Robinson. . . . 94

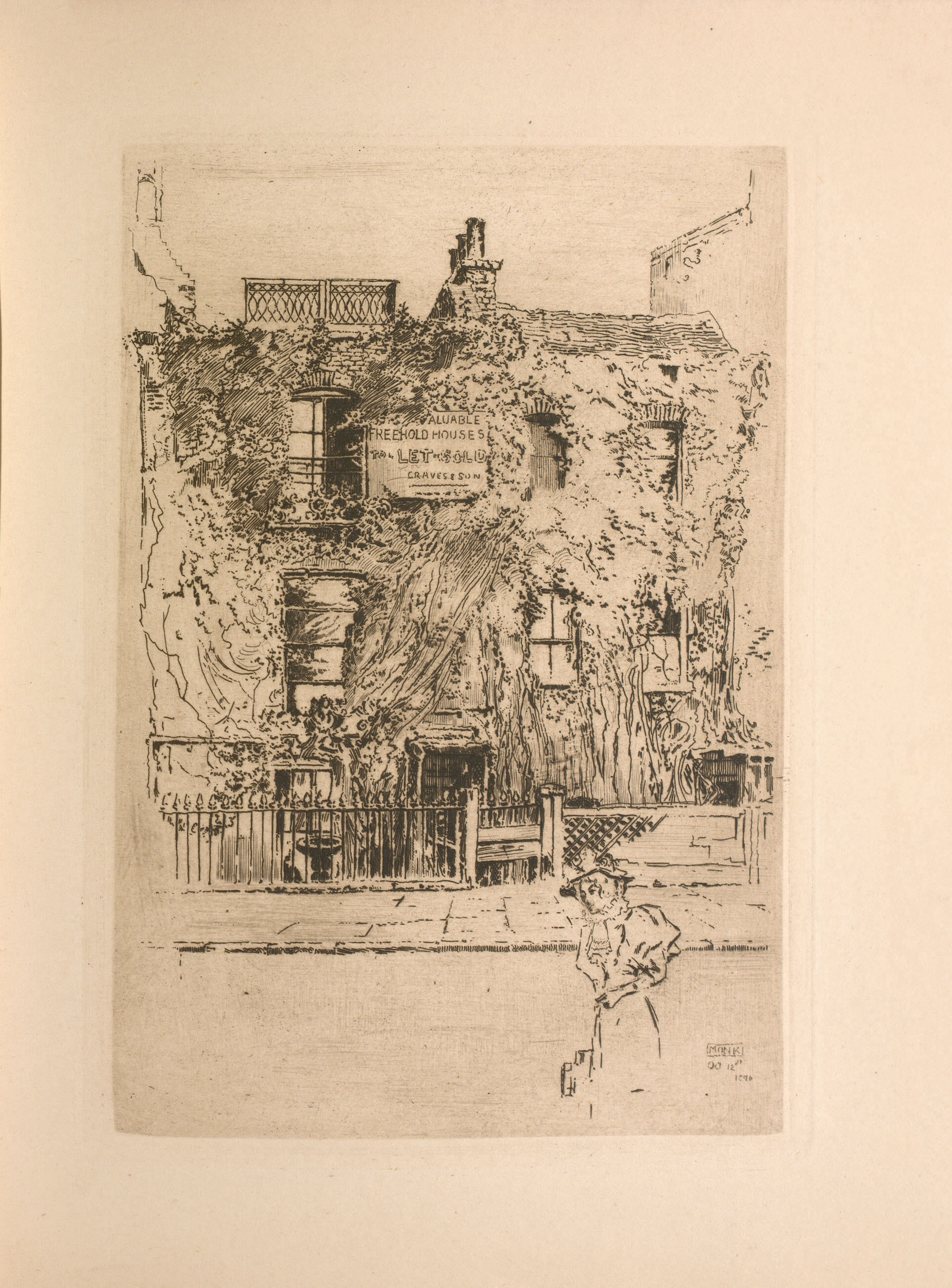

Turner’s House at Chelsea. Etching by W. Monk, A. R. P. E. . . . 97

Centaur Idyll. Charles Ricketts. . . . 105

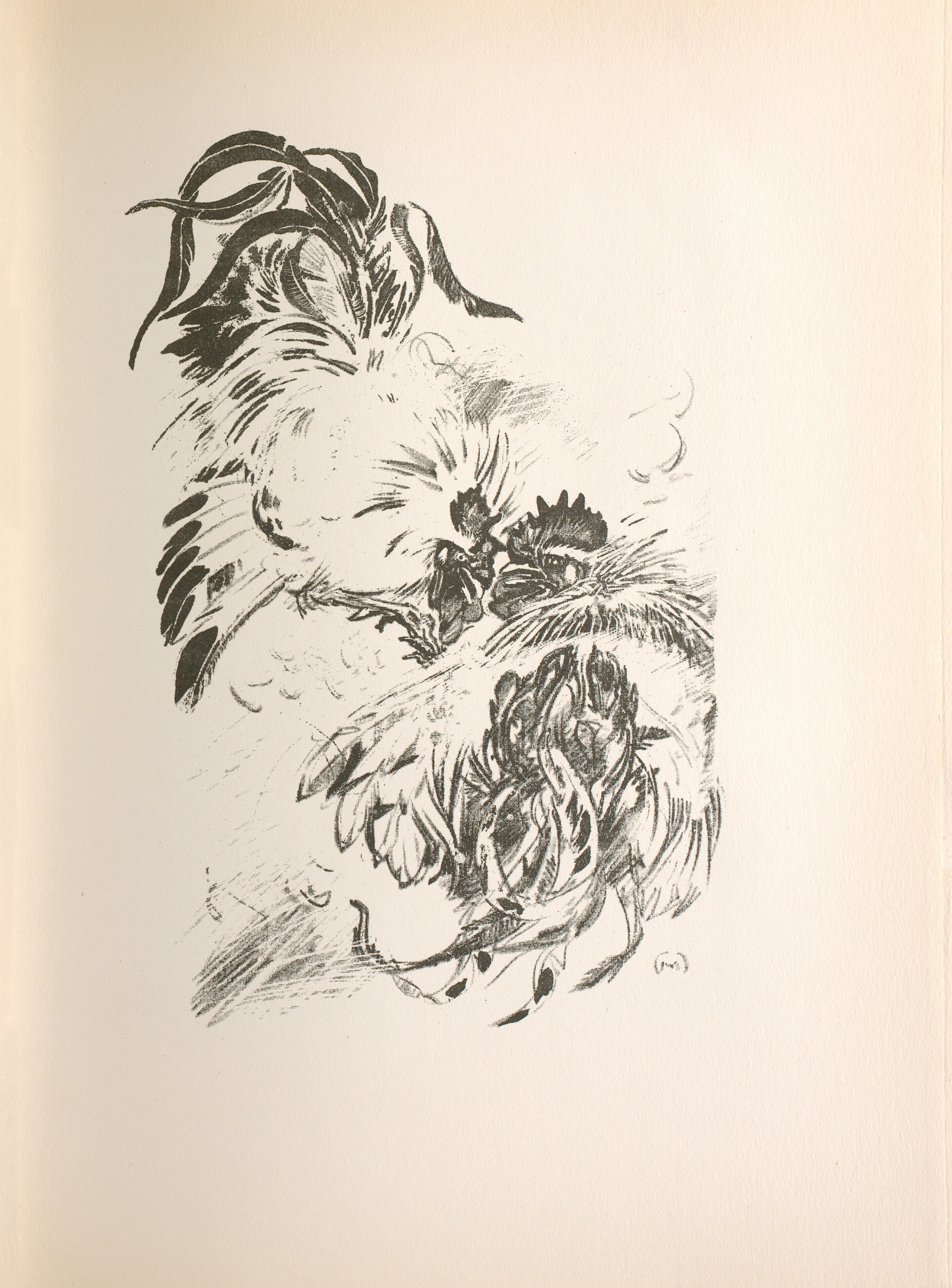

The Cockfight. Lithograph. Carton Moore Park. . . . 115

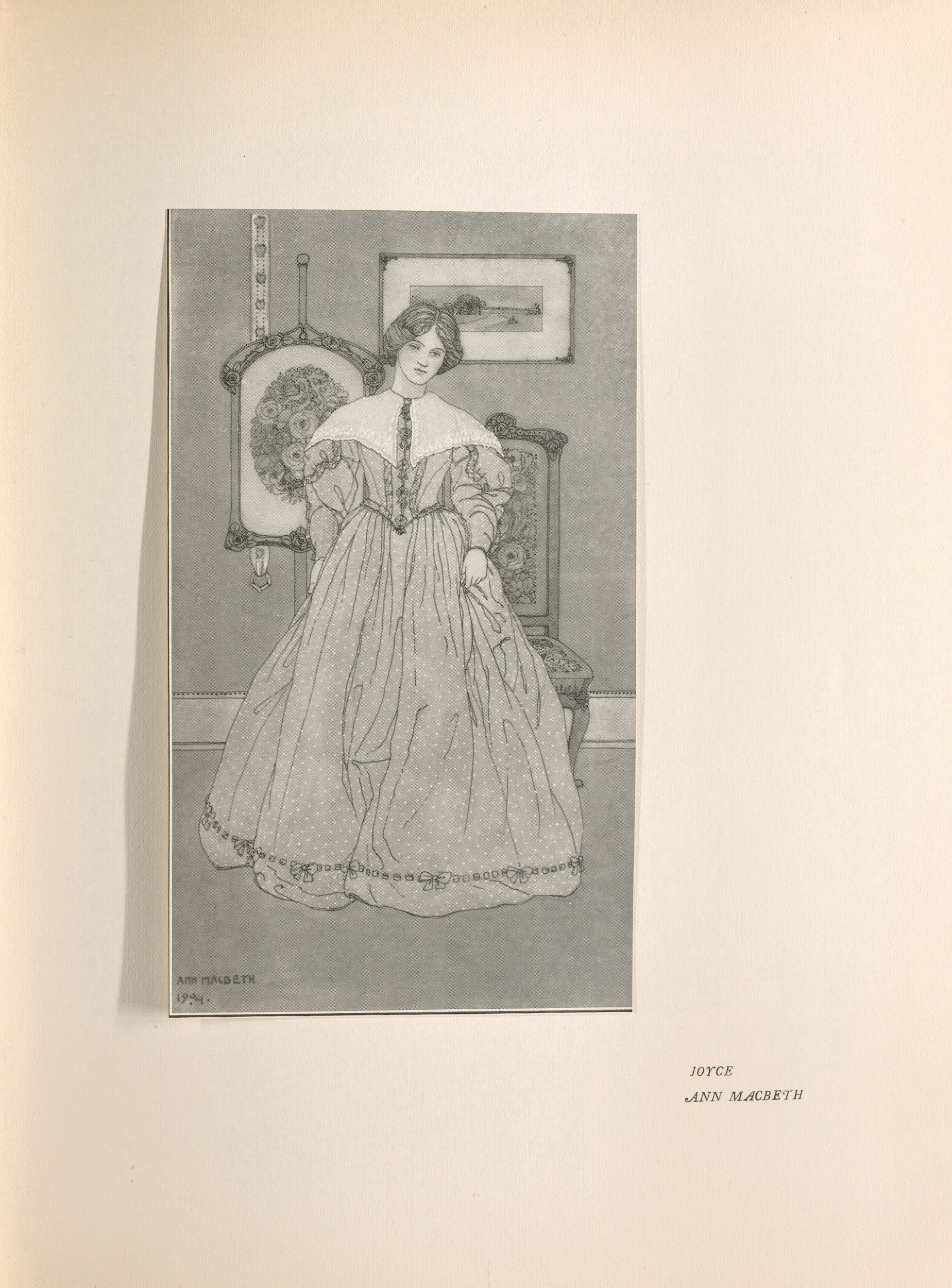

Joyce. Ann Macbeth. . . . 123

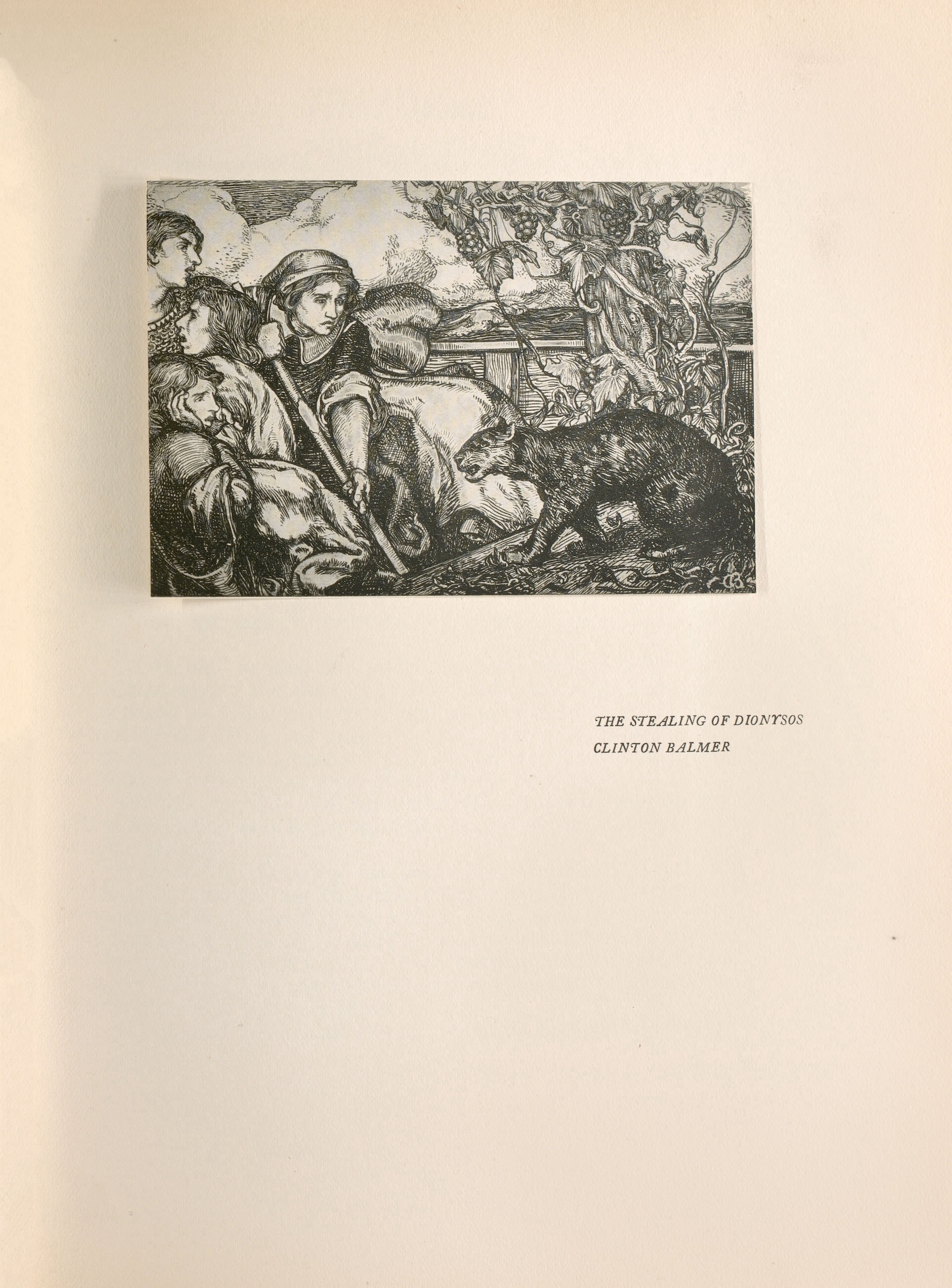

The Stealing of Dionysos. Clinton Balmer. . . . 133

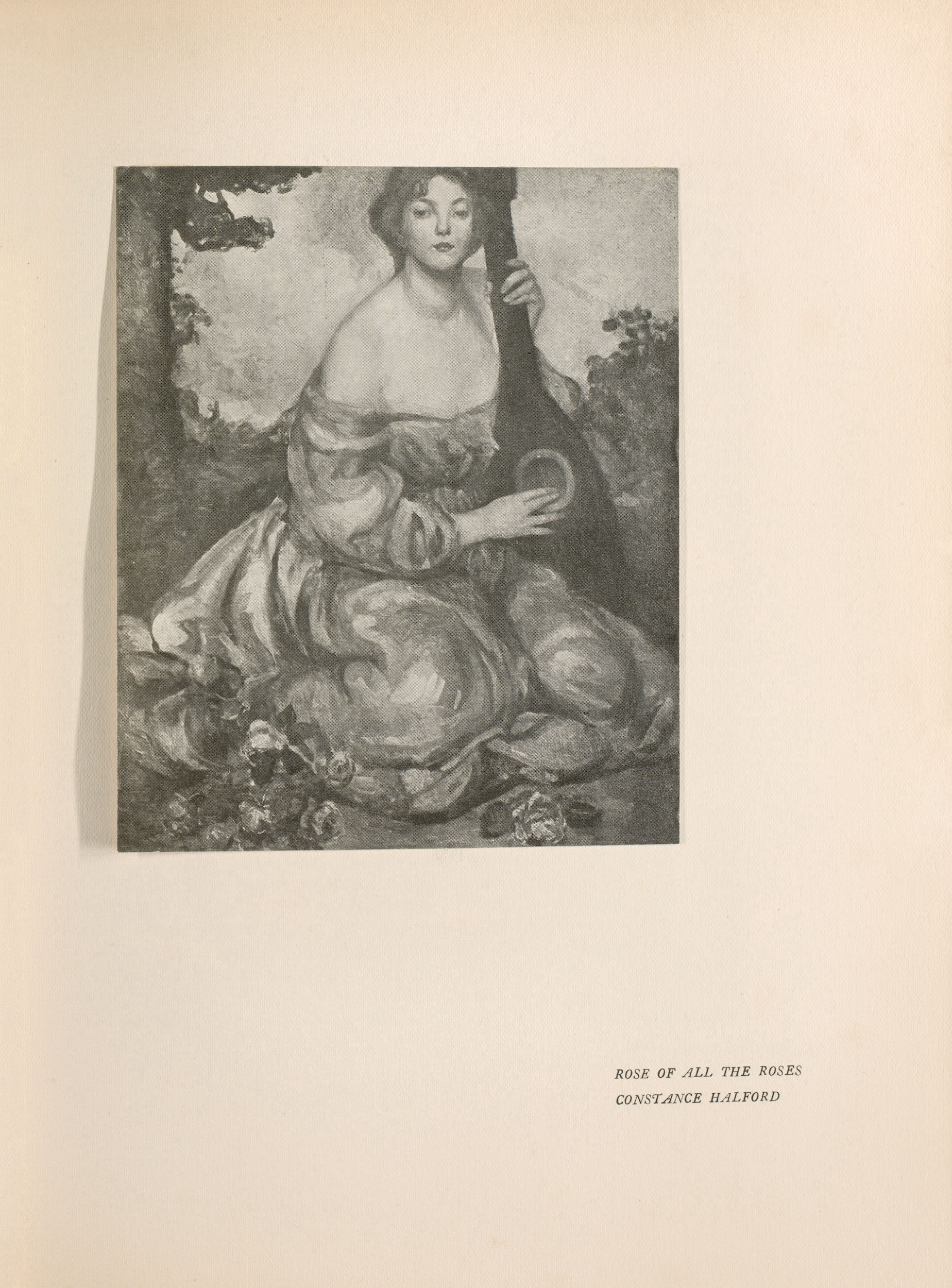

Rose of all the Roses. Constance Halford. . . . 140

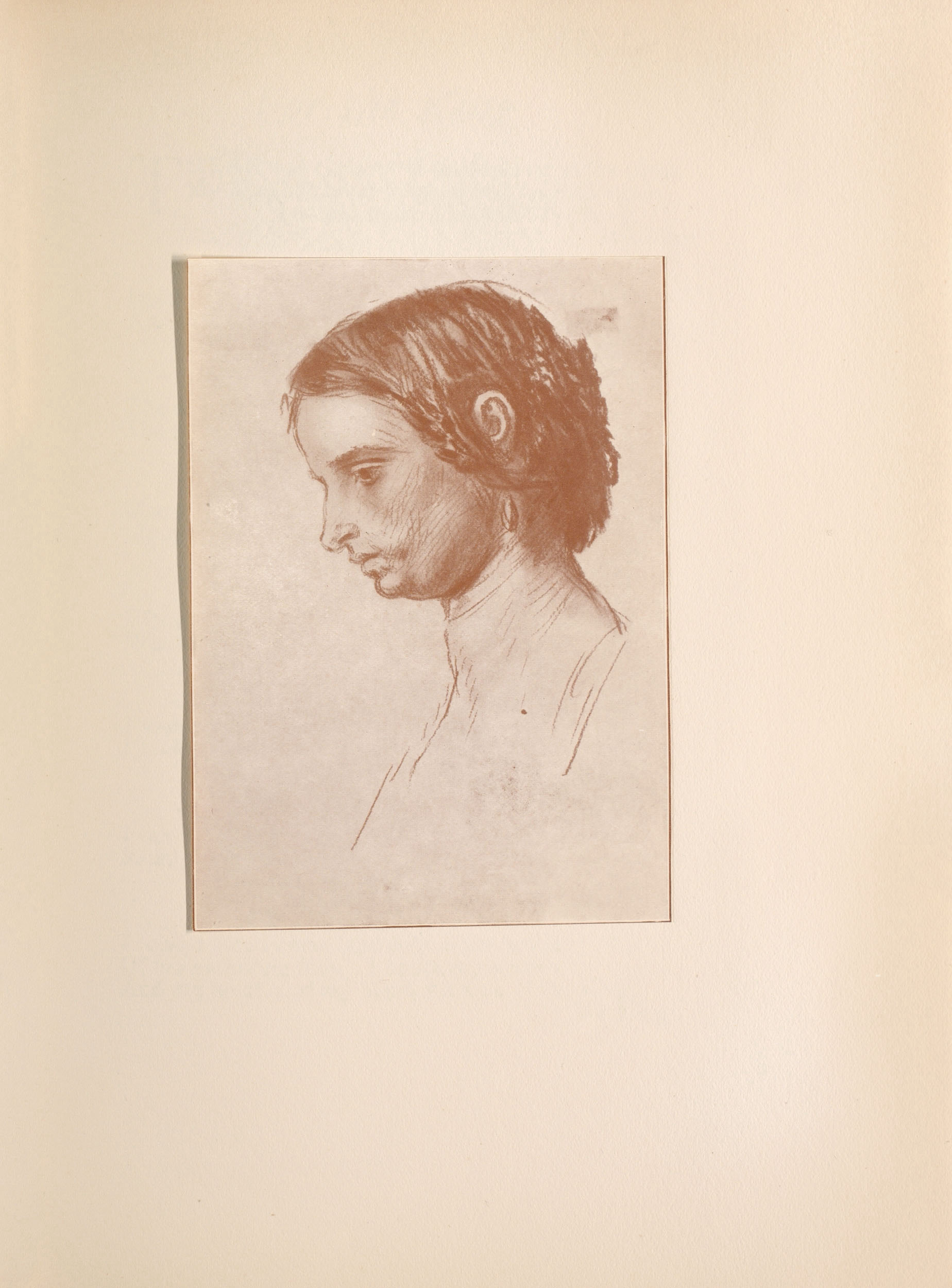

Study of a Head. Augustus John. . . . 151

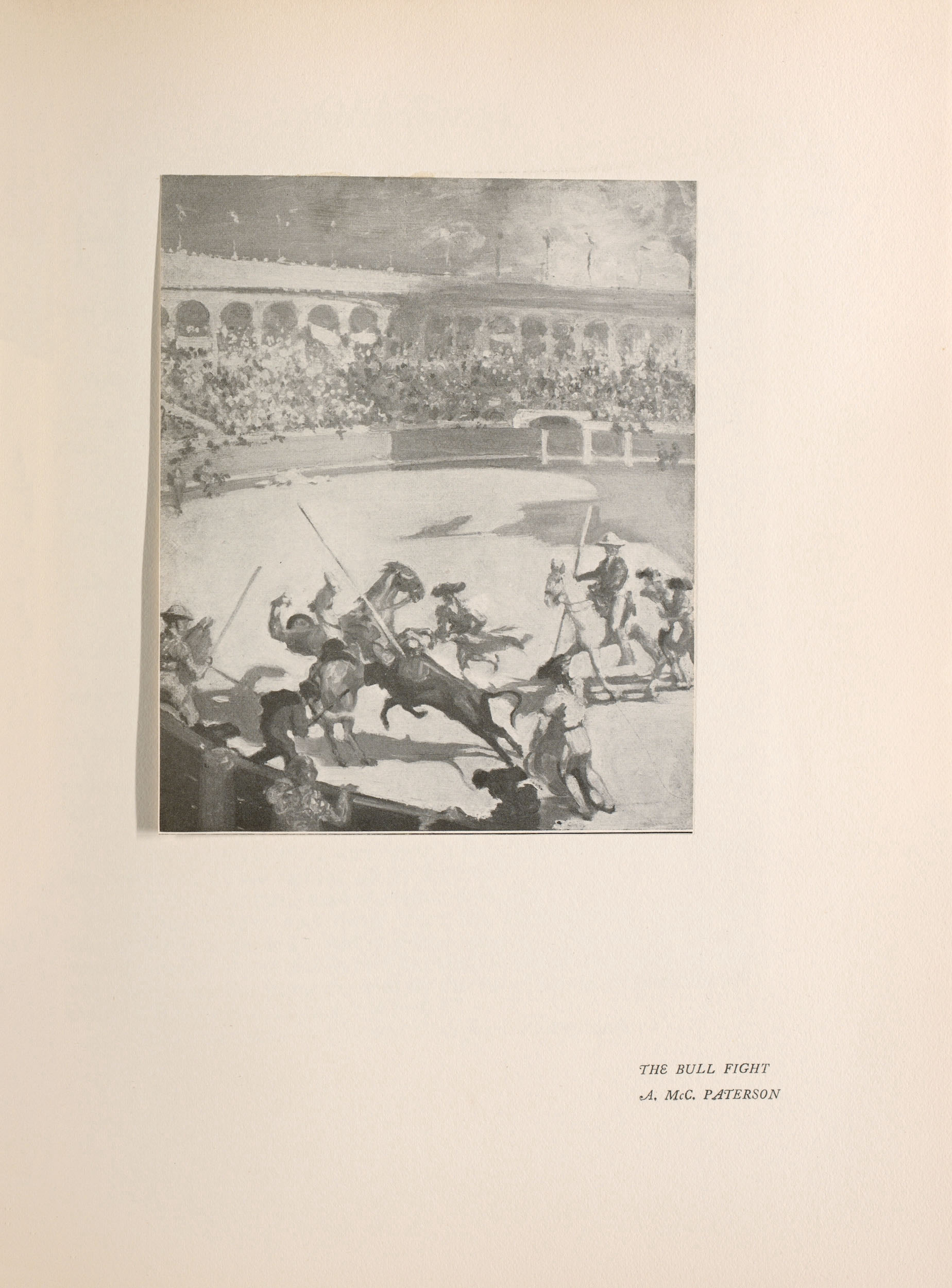

The Bull Fight. A. McC. Paterson. . . . 163

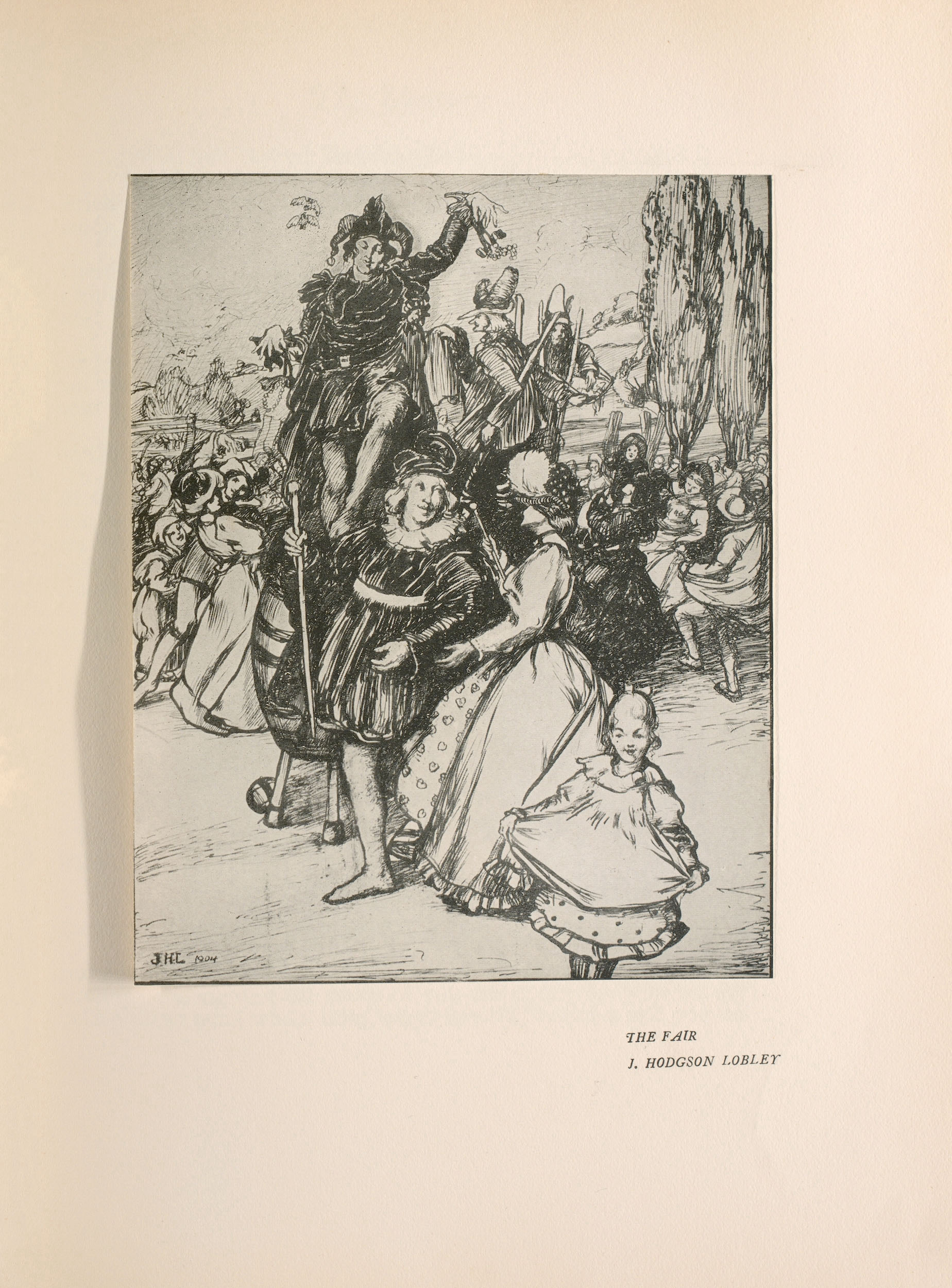

The Fair. J. Hodgson Lobley. . . . 167

The Intellectual Ecstasy

“Hinc Stygias ebrius hausit aquas”

DIOGENES LAERTIUS

I

OF Epicurus it is told

That growing weak and faint and cold,

And falling towards that frigid state

By doctors held as desperate,

He drowned his senses in a flood

Of th’ ancient vine’s ebullient blood,

Ingurgitating draughts of fire

To lull his fear and his desire.

II

But was he sober when he died?—

Whereto an epigram replied:

“He was too drunk to taste or care

How bitter Stygian waters were;

Blest was he therefore.” Can we draw

A sweetness from this cynic saw,

Or of this mithridate distil

An antidote for life’s long ill?

III

Perchance: since, as we linger thus,

’Twixt dawn and dark swung pendulous,

Supported through our irksome state

By fond illusions of past date,

The mind within itself retires,

And there inspects its dead desires—

A soothsayer, revolving thrice

Around the ambiguous sacrifice.

IV

In vain we toil to waken flame

Where once without a breath it came;

In vain old auguries invoke

Of swarming bees and stricken oak;

The Venture

2

The spirit feels no secret stir

O’ the exquisite remembrancer,

And into depths, unsealed in vain,

Drop hollow-sounding tears like rain.

V

But still, in philosophic sense,

A purple cluster glows intense,

And from an intellectual vine

Rich madness gushes, half divine;

Droops the dull vein in chill eclipse?

A heavenly beaker slakes our lips,

And cups of thrilling freshness lend

Fantastic aid as we descend.

VI

So, drunk with knowledge, only fed

With rapture from the fountain-head,

Until the bells of God shall call

The flush’d, insatiate bacchanal,

Let her go smiling toward her rest

On tottering footsteps, faintly blest,

And, in that fair delirium dight,

Walk down to darkness in great light.

The Valley of Rocks

TOWARDS evening he came to a sudden valley in the bare-

bosomed hills, where, as in an alembic, the vital humours of

the land, the rains

and the dews drawn from the sky by tall

white cliffs with violet shadows that

looked like thunder-clouds,

were caught and distilled to be transmuted into quick,

fierce crops

of grapes and corn. In many places the naked rock was clothed

with gourd pens growing like cables and bearing great yellow

flowers. Wherever

there was a hollow in the gleaming limestone

or hold for a man’s foot, mould of a

noisome richness had been

deposited. Here were terraced gardens overbrimming with

hot

flowers like some passion of the soil made visible; and secret

caves

full of twisted stalactites, like strange dreaming, pillared

and aisled and

reverberating with the organ music of subter-

ranean water. Every now and nea a

spring of very cold

water gushed out suddenly from the bare stone to run a few

yards and as suddenly disappear. Cottages, half built, half ex-

cavated, as

if they were but the sculptured portals to a labyrinth

of hidden ways, clung to

the cliff side, and the men and women

that came out to stare at the stranger were

heavy eyed and ivory

ale as if they belonged to a separate race bred in darkness

and

feaine the light only to snatch a livelihood from the shallow soil.

They

kept no cattle, they said, but a few goats, and no children

had been born in the

valley for many years. Many of the women

were goitred, and all spoke like persons

that use words to hide

their thoughts; talking rapidly, with their eyes fixed on

the

stranger’s face, beseeching him to begone. They told him that

the place

was called the valley of rocks, and that here the corn

was richer, the wine

stronger, the ay sweeter and all medicinal

plants more active in their properties

than anywhere else in that

country. Dealers in drugs, they said, came here every

autumn to

collect roots and herbs. When he asked them where he should

find

lodgings for the night, they looked one at the other, and

hastily directed him to

the inn at the head of the valley. They

told him to beware of the vipers which

here were very rare

themselves were often bitten as they contrived the union of

the

gourd flowers, in which art they were very cunning, but they took

no

harm.

As he walked up the road which wound like a snake be-

neath

the crumpled cornice of the impending cliff, a curved billow

of stone, he was possessed by the thought that the place held a

meaning, hinted

at but not expressed, in its passionate fecundity:

that he was drawing nearer to a

final statement, a summing-up in

human shape of strength and sweetness and

soothing. At the

head of the valley he came to the inn, a long, low-browed build-

ing with a line of windows under the eaves, standing in a clove-

scented

garden, with its back to the cliff and looking as if seaward

but where no sea was.

He passed through the open door, and as

if guided by a dream, to a little room

where from the wall there

leaned the picture of a woman in whose eyes and on whose

lips

were concentrated the strength and sweetness and soothing of

wine and

honey and narcotic flowers.

Now suddenly he felt that his coming here had been pre-

destined. The woman’s face, fierce though tender-eyed, with bared

throat and

offered lips, hot though virgin, lawless as a flower yet

like a flower the

concrete symbol of many secret laws working

together, was the answer to riddles

that had long vexed him.

Here was the unsatisfied desire of all the earth made

evident in

a single face. He knew that in all his wandering, apparently so

agliggainhet nothing had been left to chance. All his life he had

een seeking her,

and step by step he had been drawn hither.

The innkeeper and his wife came into the room while he

stood

before the picture. They glanced from him to each other

with lowered lids and

furtive smiles so that the question which

rose to his lips was never spoken. The

man was pot-bellied and

thin-shanked, the woman’s face a white mask of decorum:

they

were old and feeble, but had not the dignity of age. They asked

his

wants with pandering obsequiousness, consulting together in

whispers so that the

preparation of his meal seemed like a con-

spiracy. They tended him with knowing

deference, as if he were

long expected, rubbing their hands gently together and

answering

his questions eagerly to prevent his asking the one question which

his lips would not frame. They made no mention of the woman

whose picture leaned

from the wall though all the house thrilled

with her presence.

He ate and drank alone in the dusk, overlooked by the

woman’s face, her eyes fierce with desire, her lips smiling at him

with a strange

confidence. Afterwards the old couple came into

the room and they sat talking of

all that went on in the great

The Valley of Rocks

world outside the valley. Every time he involuntarily glanced up

at the picture

they dropped their eyes upon their folded hands and

smiled secretly, and when he

strained his ears to catch what

seemed like a footfall on the stairs and the

rustle of a gown they

glanced quickly one at the other behind his back.

Towards midnight the innkeeper lighted him to his chamber,

with many soft spoken wishes for his pleasant slumbers. By the

door of a room the

old man paused, as if listening intently, with

eyes discreetly lowered, and a

little guarded cough. Then looked

up, as if in answer to a question which had not

been asked, with

“I beg your pardon, sir?” But immediately he passed on to the

guest-chamber, threw open the door, and showed a carved and

canopied bed and

hangings shaken by the night air, with a muttered

hope that the stranger had

everything necessary for the night.

Then he placed the candle on a table, bowed

and withdrew,

slamming a door at the far end of the passage, as if to intimate

that this part of the house was private to his guest.

He flung wide the lattice, and leaning on the sill, gave him-

self up to musing upon the painted desire in the room downstairs.

The wind

came up the valley in hot puffs, bearing the scent of

many flowers and the murmur

of hidden water. He remembered

with a thrill that this was midsummer eve. He was

always im-

pressed by dates and seasons; not those arbitrary days named

after events sacred or secular, but those profoundly related to the

intertwined

orbits of the planetary system. He believed that at

the intersection of those

larger forces human life was deeply

stirred, as quivering overtones are struck out

when one note of

music jars upon another; and he could understand why ancient

peoples leaped through fires at the standing still of the sun. Now

was the

time and here was the place; and a dozen things, the half-

betrayed confidence of

the valley, the veiled manner of the inn-

keeper and his wife, told him that the

woman expected him.

That he had neither seen her nor heard her name only

deepened his feeling that this meeting was ordained. A chance

encounter, the

making of them known one to the other with the

necessary forms of speech, would

have blurred the mysterious

directness of their coming together. He wondered how

the inn

people came by such a daughter, for so without any definite reason

he supposed her. Then he remembered that, like exquisite wine

in unworthy vessels, rare types are often transmitted through

common people, for

generations degraded or lost altogether, re-

appearing now and again to uplift men

in grey times or to hearten

them in blazing times of war. He thought of her less

as a woman

than as the incarnation of the valley’s secret, which he was to dis-

cover from the touch of her lips. The innkeeper and his wife took

on the

character not of parents, but of priest and priestess, guar-

dians of a vessel

holding rare essences of the soil; the inn became

a temple. All that he had ever

done seemed meaningless and

trivial, except in so far as it had been a preparation

for this en-

counter. For this end only his life had been enriched with dreams

and aspirations beyond the common.

For a time his mind was disturbed with thoughts of danger.

What if the woman were a decoy for purposes of robbery or even

of murder? Again,

his heightened imagination pursued wilder

paths: he had read of dragons taking the

shape of beautiful

women and of strangers incited to their embraces to rid a

desperate

people of ascourge. A moment later he laughed at his childishness.

He wondered when and how she would appear to him.

Whether at

dawn in the garden, or on the hot limestone ledges

among the yellow gourd fone or

in the pillared alleys of the

secret caves. He knew that if words were needed at

their meet-

ing words would be given.

The house was very still, and from the room next his own

came delicate intimations of a woman’s presence: sighs, a low mur-

muring, movings

to and fro, and once a subdued noise of crying—

or was it the wind whimpering

under the eaves?

His will ceased to be his own and he fell a prey to bold

fancies born of the heat of his blood. Before his impassioned eyes

the wall was

gone and he saw her waiting for him now: a mystical

night-blooming flower unfolded

on this night only of all time.

Yet it was not she that waited, but all nature

working to an aim

through her: the crude aspiration of the earth rising up through

corn and grape, distilled and rectified through human channels,

informed

with soul as blood is brightened by air, until its essence

was offered in such a

vessel as gods might drink at.

And then the other part of him, the creature of reason and

everyday habit and convention asserted itself. Like a grey rock

thrusting in

through the ribs of a dream galley, ideas of duty and

The Valley of Rocks

honour pierced his mind. His imagination leaped ahead and he

saw the future in cold outlines. He remembered a dozen sordid

stories: the phrase “a rustic entanglement” sounded in his ears.

If he yielded to the prompting of the hour and the place, what could

be the outcome but shame for her, disillusion and boredom for

himself?

But then again the sense of a larger duty, owed not to con-

vention but to the universe, obtruded itself. He was less the

pursuer than the pursued; no more wanton than the moth to the

flower. Like two people seeking each other blindly through a

wood, guided by a cry ora word, the se of a bird, the quiver

of grass where a snake rustled, he and she had been pushed for-

ward through generation after generation of human life, with here

a check, there an encouragement, until on this night of all nights

they were watching the sky side by side with but a thin wall be-

tween them. Of all creatures was not he who shirked the purpose

of his being the most abject?

Out of the conflict of moods was born another, not of better

or worse choice but of renunciation. Perhaps, after all, the aim of

desire was not union nor even the furtherance of life, but rather

the release of the finer things of the soul as latent fire is released

at the approach of metal to metal. He had been ready and she

had been ready, but while their bodily eyes watched the sky where

one day trod upon the skirts of another on this night of all the year,

somewhere on another plane their desires had met and mingled

with the release of some new and better desire dowered with some-

thing of each, to return upon and enrich their lives asa rain-cloud,

enlace: of sun and earth, returns to bless and fertilize.

Early morning found him in the garden sobered and uplifted

with a new purpose. To him came the innkeeper with downcast

eyes and lips creased ina crafty smile, asking him how he had slept.

is question was answered with another.

“My daughter? No; we have no child. Years ago a strange

woman, waiting in vain for her lover, died by her own hand in the

room next your own. Since then, they say, the valley has been

under a curse: people may wed, but there are never any children.

The picture downstairs was painted by a man who lost his reason

seeking her whom he had never seen.”

CHARLES MARRIOTT

Pierrot

O SOME there are who bury deep

Lost joy in a grave far out of sight,

Saying, “O trouble me not, but sleep

In silence by day and night.”

But I have left my joy to stray

Alive in the wood of my Delight,

Where the thrush and the linnet sing by day

And the nightingale by night.

But I—I wander away, away

Far down where the high road stretches white,

And I laugh and sing for the crowd by day

And weep for my heart by night.

I wait for the Hour when Death shall say:

“O come to the wood of thy Delight,

Where thy Love shall sing to thee all the day

And lie on thy breast all night.”

ALTHEA GYLES

In the New Oriental Department

ONE hour to closing time in the X and Y Stores.

Here, in the

new Oriental Department, the air is heavy

and enervating—pungent with odours of

Eastern woodwork,

laden with the perfumed dust from piles of rich Eastern fabrics

and

warmed with the fumes of incense in metal boxes and the vapour

from

quaint little coloured lamps. Especially oppressive and ex-

hausting in the

dimly-lit corner where the pale-haired assistant

half leans against the Indian

screen and languidly sweeps the

“new line” of Persian glass with his long peacock

feather brush.

“Wike up, Alf,” whispers a passing confrére, “yer’ ‘arf

asleep, and guvnor’s piping yer.”

The friendly warning was needed.

“Mr Nasher—attention!”

It is the voice of the superintendent—short and sharp, like

the crack of a whip.

“Oh, yes, madam,” says Mr Alf Nasher, rousing himself

from

his languorous reverie. ‘Quite a new line. The ’ole of

these trays of glorss was

purchased by aar trav’lers in the market

place of Bagdad. Nothing like it ever

reached London before.

Sim’lar to Bo’emian, but the Bo’emians can’t produce these

exqui-

site opal tints, nor blow the threads so fragile-like. Perfect spider’s

web! Make a very beautiful wedding present, that tall pair, I

should say,

madam, or the small ones, or one alone, madam.”

But, while he cries his wares in orthodox fashion, keeping

his almost colourless grey eyes fixed upon the lady’s animated

face, the pupils

dilate until nearly the whole iris is swallowed by

their net shade; then slowly

contract, become smaller and

smaller until they are as black spots in their vague

surroundings,

and the young man begins to dream.

All this afternoon, since his indigestible, salt-beef dinner, he

has been assailed by the press and throng of his trance-world,

finding

vehicles for brain-wanderings in every detail of his work,

in despite of his

struggles to keep his feet on the solid ground of

everyday life.

The lady customers—and in this department nearly all the

customers are of the softer sex—at once enervate and torment by

drawing him,

blindfold, into the realm of luminous shadows and

diffused and rose-coloured

light. Blondes and brunettes—the

young specimens fresh, innocent, adorable in

their gauche sim-

plicity; the maturer types in the flush and fire of high-toned and

dragon-fly

loveliness; the faint carmine tints of old poe era lips

like geranium petals,

curls like spun gold; the thick, white skins

and heavy, black tresses, long

lashes, full eyelids veiling the mys-

tery of amorous Sphinxes; diffident Madonnas;

flashing Cleo-

patras; all moulds, all forms of feminine grace or seductiveness—

all troubling, tormenting him, since the clogging mid-day meal, all

furnishing irresistible material for dreams.

Suppose that he were rich, pepe ey wealthy, rich

enough to

buy up the X and Y, stock, lot and barrel, if the fancy

moved him, from the roof

tree and Toys No. 1 to the cellars and

the overflow of sewing-machines from No.

20.

Ransacking departments, building them in with invoiceless

goods, could he not win them—buy them all? Why shy at the

word? Are they not all of them to be bought if you are rich

enough to pay

the price? Who among them would long with-

stand the virtue-sapping seduction of

the Jewellery Department—

all his, from the tiaras on sale or return from the

great Midland

houses, to the little “merry-thought” brooches (9 carat, one split

pearl, 18s. 9d.), bought net and stocked by the gross? He could

gauge the

power of the Jewellery Department by those merry-

thoughts. For had he not given

one to Sybil Cartwright, of the

middle counter of “Gloves, Hose and

Underwear”?

A brown-haired, moon-faced maid—Sybil—with hair swept

over

egg-shell ears, and almond eyes, darkly lustrous as a summer’s

night on the banks

of the Karun, and the haughty insouciance

which can laugh at the wooing of a

rosetted shop-walker or a

ground-floor desk clerk, not to mention an undecorated

assistant!

But to be bought, no doubt, like the countesses and duchesses

whose fur-clad menials fill the “out” benches of the hall. “What

are in all those

saddle-bag sacks which I see the warehouse men

carrying all day long into the

Deposit Account Office?” asks

Sybil disdainfully. Gold, young lidy, my gold. Same as what

I’ve bought the ole Stores with.”

“Praad” she might be, and cold too, and dignified in de-

meanour; but he could set her dancing for his pleasure in a mar-

vellous, secret

flat, obtained through the X and Y House Agency,

and furnished “remorseless” out

of this very department, within

a month—yes, dancing before him, dressed like some

Nautch girl,

In the New Oriental Department

and all jingling and jangling with diamonds, rubies and sapphires,

as she twisted

and squirmed about to the muffled music of an

X and Y “ten clay band,” hidden away

in the next room.

“Praad, may be! but mine at last!”

Yet how restricted the power, how feeble the effect, of the

vastest treasure here in England, in these prosaic, convention-

ruled days! But to

have. the wealth and the power, too: to be an

Eastern potentate, absolute,

uncontrolled lord of all the land! Ah,

Sultan and King! sensual, merciless, if you

like, but splendid even

in his depravement; capable of fine flashes of magnanimity

to

illumine the dark background of his soul’s demoralization. ‘Lord

of all

this, my humming, bustling market-place, my walled city

and my palace all in

one—all these busy clerks and assistants my

troops, bearers and servants; the

liftmen my bronzed captains;

the frock-coated commissionaires my corpulent,

white-faced body-

guard, safe and harmless guardians of the new block of women’s

sleeping accommodation, which I herewith appropriate as my sera-

glio, and

over which I set them on guard.” …

And now is seen one of those terrible occurrences, frightful

examples of a despot’s tyranny, which have made this young

monarch at once famous

and execrable in Oriental history.

“Well, let the historians talk! What must be,

must be. Kis-

met. I have spoken.”

Throwing himself down on the finest of the embroidered

divans, while ready hands bring forward the huge hookah—that

reat unsaleable thing

that has stood by the A desk of the

obacco Department for the last three years—he

summons the

now trembling secretary, his grand vizier; issues his brief but

awful commands; and, wrapping himself in wreaths of fragrant

smoke, calmly awaits

their fulfilment.

Crunch! clink, clank! The sounds of bolts and bars; then

the

rumble of the iron fireproof doors, as they fall in their sockets

throughout the

great building, leaving only the little wickets

wee from floor to floor, between

department and department.

What does it mean? Closing at half after five! Fire?

What

is it

Alas, the panic-stricken cries, the shrieks of women, the

groans of men, too well indicate a premonition of the horrible

truth. It is nothing more nor less than one of the Sultan’s gigantic

raids for

the re-stocking of his harem.

“All out! All out! All men and boys,

outside!” the unflinch-

ing guards are already roaring on the staircases,

and husbands are

being torn from wives, brothers from sisters, on every landing.

A shriek and an oath. The astrakan toque has fallen from the

head of a tall

girl—a well-known customer—her hair is half down,

and she is struggling madly to

retain the hand of a tall guards-

man, probably her betrothed. Quick as life, the

guardsman

snatches from the wall one of those huge Afghan knives, heavy

as a

hatchet, sharp as a razor, and clears a space all round him.

In a moment he is

overpowered and hurled back through the little

wicket. Killed? Who shall say? He

has resisted the Sultan’s

command. Death were a light punishment. “Besides, it

ain’t so

easy to see through the ’ooker smoke.”

“All out! All out! All females over the age of

thirty-five

outside!” roar the guards. The men are all gone. It is the

turn

of the agonized mothers and aunts and elderly sisters. Oh,

lamentable

scene! Oh, pitiful wailings! The most valuable

parcels thrown away in anguish, the

floors littered with mono-

grammed purses, muffs, fur capes, powder boxes, card

cases, hair-

pins, and what not; a screaming and raving and sobbing and gasp-

ing which might melt a granite rock to tears, as the ensnared

matrons and

maids rush to and fro, beating against their prison

bars like a flock of trapped

doves. In a voice broken with emotion

and with humble deprecating obeisance, the

Secretary-Vizier

a that some daughters of shareholders may be set at

liberty.

But he laughs cruelly.

“That new block of buildings must be filled. I have

spoken.”

In the midst of the uproar a stout, middle-aged dame, over-

looked by the Janissaries, appeals to him for mercy. With hideous

mockery he bids

her depart.

Her prayer is in truth on behalf of her nieces—two bright’

girls from Hastings, her brother’s pride and joy, on a New Year’s

visit to their

aunt at Earl’s Court—but he affects to misunderstand,

mischievously assumes that

she is pleading for her own freedom,

and she is hustled from his sight.

“Marshal them all through the Grocery and Candles,” he

In the New Oriental Department

commands. “Then march them before me to their quarters. Give

them food. If

necessary drug them all. To-morrow we will en-

large the meshes of our royal net

and let many fish pass through.

To-night I am too weary to pick and choose. “I

have spoken.”

But what is this? A slim and plainly-dressed girl forces

her

way through the agonized throng and throws herself at his

feet. It is Sybil, from

counter 5 Ladies’ Hose, etc. Crouched

down like a spaniel before the divan, her

nice brown hair trembling

on the back of her neck, upturned towards him, three

times she

touches the dusty matting with her white forehead, then raises her

tear-stained eyes to his, and speaks.

“Oh, great Master and King! Do not do this thing. Turn

your

thoughts away from this monstrous wickedness. For my

sake let them off. For the

sake of a poor girl, open the doors and

let them go. Don’t go and do anything so

mean and low as this.”

“For your sake, girl? And what is the

ransom you offer?

Body and soul were too small a price for thwarting a king’s

fancy.”

“No ransom, O King, if they might pay it, but a free gift.

I have always loved you”; and now the lovely girl’s pale face

is

suffused with blushes.

“Then rise” he cries, in clarion tones, himself springing to

his full height; “and stand here beside me, my empress and my

queen. Open all

doors. Let the mob loose. Poor frightened

slaves! your master needs ye not.”

And with a superb gesture of dismissal he flings wide his

open arms….

Down they all go—‘“the new line”—tray upon tray—

Bagdad’s

glory, the “fragile-like” novelties of the season, shivered

into thousands of

tinkling fragments—and, as he kneels amidst

the ruin he has wrought, the merciless

voice of the Superintendent

hisses in his ear.

“Secretary’s Office. Explain it as best you can. ’Ope for

nothing from me. I’m sick and tired of you.”

W. B. MAXWELL

The Immortal Hour

I

HEART of my heart, the world is young

Love lies hidden in every rose;

Every song that the skylark sung

Once we thought must come to a close;

Now we know the secret of song

Song the glory and might of the soul,

Hand in hand as we pass along

What should we doubt of the years that roll?

II

Heart of my heart, we cannot die!

Love triumphant in flower and tree,

Every life that laughs at the sky

Tells us nothing can cease to be;

One, we are one with a song to-day,

One with the clover that scents the wold;

One with the Unknown far away,

One with the stars when earth grows old.

III

Heart of my heart, we are one with the wind,

Far we shall wander o’er land and sea,

One in many; for Love is blind;

But Love will bring you again to me.

Ay; when Life seems scattered apart,

Darkens, ends as a tale that is told.

One, we are one, O heart of my heart,

One still one, while the world grows old.

ALFRED NOYES

The Skeleton

WHEN Philaster was alive, he and I were often busy with

records of great beauty that had long ago flourished. In

solitary places, and in

hours removed and hedged around

from the straight main road of time’s advance, we

pondered the

names of Calypso, Ariadne, Electra, Eurypyle, Megalostrate, Dido,

Camilla, Lucrezia Borgia, the two Isouds, Olwen and Mary Hynes

of Ireland

and many more. Together we framed their features

and their motion. Sometimes, as

we sat, we heard their voices in

the outside darkness which our lamps made

wonderful and more

dark, and in the wind we heard the voice of Medea calling for

Jason, Andromache calling for Hector. There was a distant lawn

among woods,

watched for many days with surmising but incurious

eyes from our window, and never

visited, which was not simply

grass, but grass refined by sunlight and memory

until it seemed as

far off in time as in space and as secluded; and there, on one

day,

we saw Helen, not so proud but that she was regretful, talking

with

Achilles, while Thetis and Aphrodite, who had brought

him to her presence for the

first and only time, stood by. “Had

I been Paris,” he was saying, “I should have

been content not to

have been Achilles.” To which Helen answered: “Had you been

Paris, you had not been content to have been less than Achilles.”

Foolishly and passionately—and so, perhaps, wisely—we

talked

of the immortality of beauty, though the last hair of Lucre-

zia were lost; and

told one another that in the sculpture and poetry

of Greece no woman that was not

beautiful is remembered. And

while he lived I could not do other than believe.

Once we

watched a blade of emerald flame in the fire; but soon he clapped

his hands impatiently and it disappeared; and once it was gone

it was immortal, so

he said; and he loved best those vanishing

things which the mind quickly makes its

own, since nothing dies

save what we let die.

Whether in the fields, or in the streets, or in chambers en-

closing and opening upon beauty, we locked ourselves in the past.

Many days

I can recall when we looked out into a rich, lonely

country under rain, and the

two things real to us were the Virgils

in our hands and the soft oblivious rain

that made a solitude and

made us lords of it. Our chamber and the quiet fields

differed not

in kind from the places where the mind beholds the past with

closed eyes. Not for us those books which are but a plagiarism

from life! Rather those from which our lives sometimes dare

to plagiarize. . . .

But now Calypso, Ariadne, Electra, Eurypyle,

Megalostrate are dead; Dido, Camilla,

Lucrezia Borgia, the two

Isouds, Olwen, Mary Hynes of Ireland, are dead: for

Philaster is

dead. And how can I tell of him? for his presence gave me the

great wisdom which made me care for him. That wisdom has

flown with him. If I

declare what voice and features, what know-

ledge and wit were his, a diligent

lover might think that he could

guess, from such an inventory, what Philaster was.

It will be no

more than a brazen image of what he was. I am the fond Holin-

shed of his story, and cannot translate out of silence.

The face, which is in any man the subtle result of a hundred

centuries of thoughts and sensations and emotions, in him was not

so much a result

as the first draft of a wonderful achievement, to-

wards which I saw it ever on

its way. Every moon, every sun,

and all the winds cherished and changed him, as if

it had been

their sweetest toil. The splendour and the beauty and the sorrow

of all his books entered his face, and not merely as passing shadows

enter a lake,

but as it would be if that lake were the richer for

these transient deposits.

Shakespeare, Leonardo, Pheidias, were

as musicians that played upon some strings

of his soul. He might

be counted among their inventions. I have walked with him in

the dawn, and as the cold light and half-seen, half-imagined beauty

had

their way with his face—speech having ceased an hour before

—I could have bowed to

him in worship, so much was he an

emanation or ivory image of the dawn; he knew

all things, it

seemed, and was at one with them. But when he spoke after such an

adventure, it was with difficulty and faults that went strangely with

the

glory in his face. The words came asif against his will. Hu-

man speech seemed to

be wrong and far astray from the path it

would have taken had there been a

Philaster in the old time. It

was as a foreign tongue, uncouth and unintelligible.

Moreover it

frightened the things that fitted his brain, as a human voice

frightens a copse of nightingales. .. . After a long June day on

the Cherwell he

once walked into Oxford for a bottle of wine,

and when he returned to the boat he

told me laughingly that his

brain had been full of compliments like sapphires for

the woman

who served him, and that he had not found it in his heart to say

a

word. …I have seen him in the autumn come bemused with

The Skeleton

spiritual joy into a country inn, and raise a fear by his wild accent

and wild

eyes and his nostrils wide as if he smelt pines or the sea.

Slowly the beer and

tobacco altered the sphere of his devotions.

His own pipe was lit, his tankard

filled. He joined with a religious

ardour in Bacchic and other songs, and could

not laugh at them as

others did. And he would say that in such an inn he could wish

it were always autumn, always evening, and his capacity fathoms

deep. For,

with all his variety, I think he would gladly have ac-

cepted one experience for

ever. Nothing became stale to him, and

so his mutability was the more marvellous.

Wherever he was,

he seemed to have been born there. As one moment will now

and then, often in dreams of sleep, sometimes in other dreams,

assume the puissance

and everything essential of years, so he

assumed the puissance of great and varied

experiences which

never had been and never would be his. Hardly could his calm

physical splendour destroy the sense of terror to which the sur-

prising

tyranny of his untried, untutored mind gave rise. He

confessed, indeed, an

imperfect capacity of appreciation in regard

to many things; but from none of

these would he turn without

a salute. He brought me a long way to admire a noisy

hawker

who produced one note in his cry more notably that he ever heard

it

elsewhere.

I remember one day in March as particularly his, because

without him it would have been a task to live it.

It was a delicate, still, grey morning—cold, but with the

first heat of spring suggested behind the mist. The sun had shone

early, and the

last night’s frost, turned into a white steam on the

ploughlands, wavered a

little, like a sheet with some one stirring

beneath it, and disappeared. Not a

bird was singing; there was

no flower in the hedge; the grass was hardly green. On

the low

hills we could see a small white wreath of snow. The roads were

heavy; a coarse school-bell jangled; the sordid corpse of a squirrel

lay in the

hedge. But the very snow, which had seemed to me as

a slave’s collar on the day,

to Philaster gave the air a sad poig-

nancy that was sweet. “Look!” he cried, as

we first saw the

white form of snow among the woods on the hill, “Pan has caught

Luna at last, and there she lies, too pleased with his quiet woods

ever to

rise again.” If there were no flowers, there was a sense of

innumerable buds. If

there was no song, the air was rich as when

a great music has ceased, and contained song as in a bud. Gradu-

ally, as we

watched the mist, we dreamed of what lay behind.

Were they really the hills and

woods we knew? For they were

as they had never been before. No one was near. We

would

pursue the footpath and surprise Pan making new pipes for the

Spring.

So we set forth, but had hardly reached the crest of the

first hill when we

stopped together. The air had become softer

and caressing, and clearly said that

it was of no use to walk and

that all things come to him who dreams under a hedge

and is con-

tent to dream. So clearly did the air speak that we had not

rested long before we rose. “This is some plot,” said Philaster;

“in the next

hollow, perhaps, Pan is hiding. Let us go.” But he

was not there; at least, we saw

him not. And again, at a hill-top,

we reclined; again we thought that the air had

a purpose in thus

imprisoning us and even making us acquiesce in our bonds: again

we walked, and this time crossed several hills and hollows; and

ever, at a

summit, the next hill, clothed in wood and mist, seemed

to be the one we desired.

At last we paused again, and watched

the sun set beyond the next hill. “Yonder he

must be,” we said,

and, as we gazed and gazed, and darkness darkened and a diffi-

dent moon grew white, we were thinking of the hill beyond, until

our senses

became aware of more than is ever seen or felt or

heard, and a great sigh passed

through the wood, and we knew

that what we sought was there. The sky was of a

tender and

solemn blue that lasts five minutes and looks eternal. It was a

colour that had for us the same exquisite and surprising quality as

the blue of

thrush’s eggs found in childhood and in loneliness, be-

fore time “brought death

into the world and all our woe.”

Philaster and I had found our first thrush’s eggs at about

the same time in the same wood. We had met in the days when

the morning air was

stronger than wine is now. As each new

day shone upon the glass of a bedside

picture and awakened us,

we thought of it as never to end; evening was as if it

had never

been. We were confident, important; bragging as a rose brags

with

all its leaf and flower; never considering the six feet of earth

and an

unnecessary stone.

But every man has two childhoods: first, the early years of

his life; second, those early years as they appear to him after-

wards, moulded by

the art of reminiscence, with changes, gains

The Skeleton

and losses, until the end. Men in whom these two differ greatly

are not often

happy, and perhaps they are always melancholy. In

Philaster’s case the two were

almost invariably different. They

differed as failure and success. The real (if I

may so distinguish

it from the other, which was far more real and impressive to

his

mind)—the real was the failure: for it was foolish and not wild;

selfish

and not independent; coarse and not obtuse; fond and not

loving; fitful and not

passionate. But one or two incidents there

were of a painful kind, which,

happening in notable, beautiful sur-

roundings, were likely to be seared along

with them into his brain,

as indeed they were. How easily and pleasantly does old

pain

help us to remember! how the sudden, cruel fall from a tree helps

us to

recall that the reddest apples in all the world hung there

on one October dawn—as

if they hung there still somewhere in

the dim lands of the brain! And what early

books are remem-

bered like those whose words fell upon a brain languidly

sensitive

after long discomfort or pain?

One May day, when he was yet of an age to run fast and

hopefully towards the horizon to catch the white cloud which was

calmly sailing

thither, he was running so, when he was tripped,

and fell and tore the collar of

his tunic in the fall. It was a fair

tunic, and a fair thorn bush that tore it;

but the rent was foul; so

he lay and consoled himself by being sad. The day was

one of

many cold, bright days which had delayed the hawthorns. But

there,

upon the bush, was the first May flower. As he went to

pluck it, the white cloud

reached the horizon and the air was very

still. The yellow flowers, that had

flamed before, now glowed,

warmer but more dim. The white flowers lost

distinctness and

made a still haze along the hedge. The lark ceased to sing,

or

rose but to the height of the oaks and forgot and descended. The

white

road that had seemed but a cheerful link from village to vil-

lage was now so

long, so long, that it was as a road in a picture

and could never be travelled;

and instead of making the hawthorn

bush a half-mile mark, it made it lonely and

strange, and Philaster

could not pluck the flower. Then, suddenly, as if it had

been the

work of that strange, lonely land, of all those dim flowers and

silent birds, the noise of bells arose, and Philaster began to walk,

and sang

continually new phrases for the notes of the six bells,

until he came to the

churchyard. There, in all the warmth of the

tower and the bells that were but the murmur of that warmth, he

fell asleep. And

long he would have slept, because the air was

seething and bubbling over with the

sound of the bells. But the

headstone that was his pillow was hard though warm,

and rough

with a permanent gold and copper dust like the remains of em-

bossed work, and a voice as sweet as the bells and more shrill was

repeating their

notes. The voice, too, had a face and hands and

hair and a short green frock, and

the hands were breaking up

flowers and dropping them on Philaster’s face, so that

he awoke.

As he opened his eyes he saw the girl, as if she had grown out of

the sound as the sound had grown out of the morning that was so

lonely and so

strange. At first her beauty alarmed him, and,

thinking of a book, he asked: “Is

your name Isoud?” But she

laughed, and he knew that she was not Isoud. Then he had

the

courage to ask if she would pin up his collar. “Yes,” she said;

“and then

I must go away. fon going a long way to-day. We

shall drive past here, and 1 must

wait and watch me go.”

“Yes,” he said. “Tell me if I hurt,” said she, as she

pinned up his

collar. Then she ran away. In half-an-hour he saw her go by

with a laugh; but he cried bitterly when she was out of sight, be-

cause the pin

had gone into his neck, and more gorgeous than all

the flowers, and warmer than

the sun, was the purple blood. And

so, dimly and bitterly desired on that first

day, gravely remem-

bered for a week, and then for a few years forgotten, and

again re-

covered in memory on another day like that, she grew into the

perfect lost rose, with the memory of which he would never part,

with the loss of

which he would never acquiesce. . . .

Such a one was Philaster. But that was in the time when

the

world was no more to us than a stoat’s skin, shrivelled and

hairless, not even

foul-scented, on a stable wall. As we went on

through time, our conversation

became the most intimate I ever

had. With him I discovered myself; he had,

perhaps, a like ex-

perience. But at all times he indolently monarchized in

silence

and in speech when we were together. His sympathy was so

acute and,

in expression, so womanly; his intelligence so free

from principles, conclusions,

generalizations; his joy so splendid;

his melancholy so tender and yet without

languor or submission;

his voice so perfect, that I was often made ashamed of my

own

passionate words. He echoed my deepest emotions with easy

The Skeleton

luxuriance. Had I thought or dreamed or loved in such a way,

then so had he. Had

I learned in some potent solitary wood or

crowded street that the soul affirms

many things which the reason

has neither the right nor the ability to deny, then

so had he.

A day came when I went chilled and lonely away from his

company, and could be restored only by his presence and the

strange security and

isolation which his voice and look established.

I dared to think that he was but a

flawless marble effigy above the

bones {of his dead youth, and that prudence was

the sculptor.

Where he used to be unaware of the world, he came to despise it

and use it. And I became a rebel: yet the object of my rebellion

could quell

it by his simple presence, and my plots vanished at his

appearance as ghosts at

sunrise. For still he kept his lovely gift

of penetrating the secret of every hour

and using it. Still, as we

sat by the fire, would our souls be now blown about

together by

the great winds to which the chimneys were a many-reeded pipe,

and now warmed by the calm glow; and still would he be as one

of the gods again,

come to me, surely, in direct descent from the

past and speaking of Olympus as

plainly as the last beacon spoke

to the watchman on Agamemnon’s house of the

burning of Troy.

So it happened one year that, when Spring was at hand,

I

could think of nothing pleasanter than to go with him to meet it

in a country

which we knew.

On the first morning our shoes rang like a peal of bells to-

ether on the cobbled village path; the horses’ hoofs on the moist

rm road made a

clear “cuck-oo” as they rose and fell; and far off,

for the first time in the year,

we heard a plough-boy, who remem-

bered spring and knew that it would come again,

shouting “Cuckoo!

cuckoo!”

Often it happened that a lane led us to the sudden top of a

hill and seemed to end in the blue, white-clouded sky. As when,

on the stage, a

window is opened and someone invisible is heard

to sing below it—to sing, perhaps,

but a serenade, and yet some-

thing so heavy laden that if we could only

understand it. . . . So

for a moment, at the end of the aspiring lane, a window

seemed to

be thrown open in the sky and let in a music that silenced

thought

and even regret. I say regret: yet, indeed, as the fire

round the martyr burned to

roses, so our pleasant sorrows were

changed, and never were we lighter-hearted

than when we shared

a heavy grief. And I know not whether we were happier each

morning as we set out

lazily under sun or rain; or when, each

night, we hastened to our lodging with the

speed which comes of

hearty and rejoicing fatigue, and quietness and talk set in

around

a fire that we watched as if it were an invalid, until its sudden

sighing death sent us (already with one hand in the hand of sleep)

to bed.

Slowly we came to that wild, lonely and delicate land which

we had seen in our childhood; and our dreams, when we remem-

bered many things,

were of nothing lovelier than that land. So

clearly was one dream of mine a

recollection that once again

I struck Philaster for laughing at my fears for some

young finches

that a cuckoo ejected from a nest. I awoke a little pleased at

thinking of the blow, but when we met in the morning I repented

as I told the

tale.

It was, as we saw it from the slope of its first hill, a grey,

vast land; and its intolerable vastness made the soul ache as it

wandered

ignorantly and curiously, sore and yet eager, from hill to

hill, as far as the

verge, where clouds seemed mountains, and

mountains clouds. For while Philaster

and I stared and stared,

our souls went out from us over the hills, and we were

vacant,

submissive and terribly alone. They went out further than the

white,

thin moon of twilight that rose, like a weird bird from a

weird nest, from the

furthest valley. As we possessed our souls

again, we felt a little separate and

strange. The landscape had

apparently a power of extracting all the fruits of our

characters,

good and bad. We became odd even to ourselves, wondering

what we

should bring forth under that large influence. For a

moment I forgot all that I

knew of Philaster in perceiving what

I had never known. Always fond of deep diving

in the silent

waters of consciousness, we lost our way and came disappointed

back. But, looking down at the hamlet that stood as a lighthouse

at the edge of

that land, we saw that the valley was soft, with large

lawns running to the edges

of woods, all of that melting colour

which green becomes at twilight.

On the next morning the blackbird’s note (as it sang alone,

uncertainly, before the light arrived) had not in it more of the

sweetness of soft

rain than the light summons of Philaster beneath

my window; nor was the song, or

the clinking of the dairy pails,

The Skeleton

more in harmony with the kind of morning I guessed at, as I

watched the dimity

curtain whitening, but with gold in it. For

the moment his voice seemed to me to

be superior to it all, to

be the morning’s most perfect flower, to be the

eloquence of

which all else was a superb applause. He dug his heel into the

sweet grass and cut downa daffodil, as a king with his equipage

might trample on a

beggar as he went to be crowned. He was

a captain and discoverer of nature; a

king, and the dawn his ban-

ner, the white stars his crown. Yet I thought at first

that there

was something arrogant in his joy. I find a melancholy in all

sweet music: in his voice there was none. But suddenly he sang

Sumer is icumen in

as he went further among the apple trees, and there was just a

shadow upon the

song, just a glimmer of dew from Phlegethon in

the stream of it. As, when we see a

proud, high summer heaven

of white and blue plunged in a shadowy pool, the shadows

and

the very act of looking down give the true image a sadness: in

that way

the song was charged, and I rejoiced as I moved and

broke up the sleeping beams

and shadows in my room.

Then, for a little while, we sat in a room that was near to

the orchard; and beyond the orchard was a barn. We could not

talk, and I went out

to the barn and found that a lattice window

concealed me and yet allowed me to

look at him. I could see

also the valley and the hills; hundreds of oaks; a river

that

swayed its irises; a grey, distant, unreal house that wanted my

fancy

to people it: but I knew not what they meant, and they

were as things mentioned in

a dull book, until my curving glance

fell again upon Philaster, and then all were

harmonized. In every

wood and hollow we passed that day he strengthened the

natural

spell, and he seemed to stand to them as the artist’s name in the

corner to a picture. A completeness of vitality in limbs and

brains and senses

gave him an importance in his surroundings

of cloud and hill and river, and a

relation to them, such as may

perhaps be discovered in all men by archangelic, in

few by mortal,

eyes. Never have I seen or read or dreamed of a man who was

so

at one with all things. Seing him, I believed that sun and

moon and stars and sea

and trees and beasts and flowers were all

one commonwealth. That this is so I have always known, but the

knowledge mattered

not until I saw Philaster. All that he was,

all that he did, I believe, was related

to all other things. He de-

pended on the great oaks we passed, and they on him,

for some-

thing of their life….

Yet when I saw him last, as was my fortune—a clean skele-

ton, which ants traversed in their business, among fir and bracken

and earth

embossed with moss like moles—he was not less in

harmony with all things than

before, while a dead leaf wandered

past the moon, and the branchwork of a solitary

hemlock stood

mightily up and wrote upon the pale blue sky a legend which said

that October had come and denied April and May and June.

EDWARD THOMAS

Otho and Poppaea

(From an unfinished play.)

SCENE: The Gardens of Agrippina in the Vatican.

Otho. A word, Poppaea!

Pop. I will speak with you

If you will speak for kindness; but your brows

Are sick and stormy: why do you frown on me?

I will not speak unless it is for love.

Otho. Nothing but love, Poppaea; nothing less.

Pop. Then sit by me and take my hand, and tell me

Why you are sick and stormy and unkind

For nothing less than love.

Otho. If I should sit

So near you as to touch you; (she

comes near him) no,

this once

I will not touch you, and this once I will

Speak to the end.

Pop. (sitting down) Why, stand then, and so far,

And come no nearer, and by all the gods

Speak, and if you would have it be the end,

You are the master here, not I.

Otho. Alas,

I fear the end is over. Yet, if once,

As I thought once, you loved me, if you keep

So much remembrance as to have not forgot

How, when, how much, I loved you, tell me now

What you would have me do.

Pop. You love me still?

Otho. Still.

Pop. And no less than when you coveted,

My husband’s wife, and still no less than when

You heated Caesar, praising me?

Otho. No Less?

No more, Poppaea?

Pop. There was a time once,

You loved me lightly; there was a time once

You taught me to love lightly; and a time

Before that time, if you had loved me then

I had not loved you lightly, Otho. Now

I have learned your lesson, and I ask of you

No more than what you taught me.

Otho. Miserable,

And a blind fool, and deadly to myself,

I have undone my life; it is I who ask

What you have taught me; for I cannot live

Without that constant poison of your love

That you have drugged me with, and withered me

Into a craving fever. There is a death

More cruel in your arms than in the grave,

More exquisite than many tortures, more

An ecstasy than agony, more quick

With vital pangs than life is. If I must,

Bid me begone, and let go and die.

Pop. There is no man I would not rather know

Alive to love me. What have I done to you,

Otho, that you should cry against me thus?

Otho. I will ask Nero: you I will not ask.

Pop. Otho, I hold your hand with both my hands,

Look in my face, and read there if I lie;

But I will love you, Otho, if you will.

Otho. I hold your hands, I look into your eyes,

There is no truth in them; they laugh with pride

And to be mistress of the souls of men.

Pop. I will not let you go unless you swear,

That you believe me; tell me, it is true,

Nothing but the truth, and do you really love

Nothing but me?

Otho. There is not in the world

Anything kind or cruel, anything

Worth the remembering, else: but you are false,

False for a crown, and you are Cressida

False for the sake of flaseness.

Pop. On my life,

I love you, and will not let you go.

The crown makes not the Cæsar; have I not found

More than a kingdom here? Take this poor kiss,

And this, and this, for tribute.

Otho and Poppaea

Otho. Either the Gods

Have sent some madness on me, or I live

For the first time in my life.

Nero enters quietly and comes up to Otho and Poppaea.

Nero. My most dear friend,

Once, being with this woman who stands here,

(Do you remember?) you, with her good leave,

Shut to the door upon me: I knocked then,

Hearing your voices merry with the trick,

And no man opened, and | went away.

I ask now of this woman, and not now

As Cæsar, but your rival, Otho, still,

I bid her choose between us. Let her speak,

And you, my Otho, listen.

Otho. If the truth

Live in your soul, speak now, Poppaea, now

The last time in the world.

Nero. (smiling) Poppaea?

Pop. (throwing herself into his

arms). Need

Poppaea speak? Nero knows all her heart.

Nero. Is this enough, Otho?

Otho. Is it enough;

Otho knows all her heart.

Customs of Publicity

NATIONS have so scattered, so various, and so broadcast a

quality of inconsistency that it is not worth while to re-

proach them for that

sin. Ifa man had so little conscience

of his own will, he would hardly be human

enough to bear a man’s

name. But in truth none but those accustomed to think in

the-

toric would require of a country the unity of feeling that proves a

man

to be sane. None the less it is unintelligible that—despite all

our little English

private ways, our blinds, our shrubs, our railings,

the enclosures of which we are

so fond, our separate houses, our

suburbs, our resolute little solitudes at close

quarters, our point-

blank seclusions, the thin screens we make haste to

interpose’

where we cannot shut off the voices and the pianos; despite our

close crowds just at arm’s length, and the cramped hiding-places

that we crouch

in—we should yet take a daily license with names.

The French paper gives no such publicity to the unfortu-

nate. There is not a small malefactor, not a litigant, no citizen

subject to an

ignominious accident, not a man whose affairs are

exposed inevitably to public

inquisition, but the Paris paper leaves

him the privacy of his name. In the case

of conspicuous assas-

sins or criminals of note, of course, it is not so. Some one

must

ultimately content the general curiosity by publishing the names

of

these; therefore no attempt need be made to secure to them

that possession,

escheated once for all. But the others—the un-

lucky, the pauper, the bankrupt,

the plaintiff, the defendant, the

accused, the acquitted, the condemned, the

ridiculous, the reluc-

tantly exposed, the accidentally revealed—does the custom

of the

press in France confirm in their hold upon that last right, the right

to the idle) of their names.

Strange to say, the very word privacy is English and hardly

has a translation, yet the English custom offends and violates the

thing for which

it has the exact and peculiar word, and of which it

has precise consciousness.

Thus the English custom outrages

Privacy to its face—as it were in person. Nay,

does not even the

exhibitor of his own portrait retain in France the dignity of a

sequestered name? The English catalogue prints names in full.

It seems that

the French difference is clear enough: For dealers

with the public, published

names; to those who have nothing

whatever to present before the world except the

strife, the misfor-

tunes, or the errors of their intérieur, or the favour of their faces

as a painter may render it, the appropriate reserve is left. By what

strange

consent is it resigned in England daily, and by those who

have nothing but

confusion to undergo—rich and poor alike? The

last obscurity of mean life is not

obscure enough to suppress a

name. Insignificantly disgraced, it is

insignificantly given to the

world. The slums cannot bury it. Its commonness gives

it no

shelter, except the slight and uncertain shelter of its multitudinous

use—so many share it. Nor is there any possible paltriness of

crime that shall be

permitted to efface a name. oreover the

prosperous, the powerful, must suffer like

things, by the same

general consent. Their salient names have to endure the

peculiar

and unmistaken stain.

It was Charles Kingsley who made much of that human

possession—the eternal, inalienable, and inseparable name. And

even those who have

not conceived his whole idea of this sign and

proclamation of individual life and

destiny, must assuredly have

felt at times the value of their names—not as known,

but as un-

known. For instance, the crowd is free of your aspect; to your

walk and dress and demeanour it has a kind of Hole of sight; it

may overhear your

voice and jostle you by the shoulders. But

while your name is your own secret, as

you walk alone, you re-

serve the heart of your privacy. Why, then, is it to be

compro-

mised by the merest chance? Ifa thief shall have your purse, all

thieves will have your name, forsooth! Or a carriage accident is

to be enough

occasion for unsealing it. As for your poor brother

or sister, the “first

offender,” is it not a cruel custom that makes

the name as public as the crime? A

cruel custom and a useless!

The idle readers of police reports surely find their

amusement in

the anecdote, and not in the name of the unhappy hero, whereas

to him and his acquaintance the name is all-important. Something

else than humane

is this English habit, and it is no small indelicacy

to read the paper; you may

read of the capture of a young thief,

as the Paris paper tells it, with mere

initials, and your conscience be easier.

That our national custom in this respect is of long standing,

old newspapers bear witness, but with the strangest little sign of

pudeur showing consciousness of the act of cruelty. It is

this: In

a magazine of 1750 a monthly list of bankruptcies Is given, and the

title of the column is printed “B—nkr—pts.” Under this shrink-

Customs of Publicity

ing and shocked head-line in its large type appear in full the bap-

tismal and

family names of the whole company of the month’s

b—nkr—pts, headed_by some unhappy

Eliza Hopkins or so,

rocer, say, and of Bristol. It is the sorriest show of

sparing

Eliza Hopkins; nay, the thing is made worse by this lamentable

stammer, which does but add a humiliation. A frank title of

“Bankrupts” would have

had all the indifference of mere business,

but the hesitation is traitorous. It is

a much harder thing to have

the ill-luck of the Bristol grocery made public under

this show of

forbearance and emphasis of indignity. Eliza, being an honour-

able bankrupt, must needs feel something of the reproach of the

fraudulent when

she sees her condition made the subject of this

mock hide-and-seek.

In England to-day we make no show—even so wanton a

show as

was made by this mincing magazine of 1750—of sparing

anybody. Recall the case—the

many cases, rather—of the late

Jane Cakebread. A few years ago there was a woman

of that

name, incorrigibly drunken, in the streets of London. After a

great

number of appearances in the police-courts, some reporter

thought it worth while

to print her extraordinary name. Printed,

it caught the eye. The dull fact of her

being haled before the

magistrates acquired by repetition a cumulative interest:

her re-

plies began to be reported. Soon the paragraph-writer in the

cleverer papers, vain of what he called an “unmoral” view of men

and things (he

did but make one more mongrel word by his Teu-

tonic particle, and he altered the

meaning of the supplanted Latin

negative less perhaps than he thought), began to

follow her with a

bantering applause; she was old, she was courageous; her name

considered, she was unique; she might surely be allowed to enjoy

herself in

her own way, whilst Fleet Street looked on amused.

Tolerance—that was the word,

tolerance and humour. When the

unfortunate was gathered finally into a lunatic

asylum, and died

there confessedly insane, the humourists had less to say. In

Paris

Jane Cakebread would have been Mme C. What a loss such a

suppression

would have been to the inexplicable gaiety of our

single nation! Her career, her

convictions, her indomitable vice,

her cheerfulness—all would have been little

without her name.

Ah, it is we who are the “lively neighbours”! The Parisians

would have taken Jane Cakebread so seriously as to hide her, to

waste her with an initial! That very name which to our papers

was precious is

that which they would have had the gravity to re-

spect. Tell us no more of the

gaiety of France. There is not a

journalist in London but was more gay than

that.

So useful a purpose, I am told, is served by this universal

publicity that my

wonder is thrown away. Business, for example,

is safeguarded by the proclamation

of the failure at Bristol. So

be it; but would it be too much to ask for some

discrimination?

What is safeguarded by the publication of the names of suicides?

Now and then an effort, forlorn enough, is made by family and

friends to

keep some hold upon their own secrets; but they are

De obliged to yield them, unto

the uttermost fact. Granted

that the story has to be told, and that the courts

have to be open,

is it necessary to print and placard the name? It is the name,

the

mere name, that one might plead for. Other countries find no

such

necessity. Then comes the almost crushing rejoinder that

other countries do keep

judicial and official secrets, and with what

consequences to-day in France—with

what consequences! But

none the less should it be possible to have the affairs of

private

life—made public by the anomaly of violence—opened by the pro-

cesses of the law in all their history, but closed from the mere

reader as regards

this one possession of the unfortunate, their

names. Is it not the possession even

of the dead—their only

right? There might be less of this futile, desperate, and

always

defeated attempt to keep hidden the history of a suicide, but for

the

knowledge that if the facts are given to the world, so also will

be the name, and

that from this strong custom of a country there

is no escape.

Paris, in a word, prints in full the name of the critic and the

reviewer, and

hides the name of Jane Cakebread, and hides the

name—in which there is no

amusement, none—of the man who

yesterday breathed the vapour of charcoal in. his

room. London,

on the contrary, generally veils the name of its dramatic critics;

but it prints the unnecessary names of those who had no desire

but to

vanish. It prints the names the printing of which—adding

much to the confusion on

one side, the helpless side—adds little

or nothing to the idle pleasure on the

other, the pleasure of an

idle reader. For, seeing that the names of criminals, of

suicides,

of parties in an amusing lawsuit, of the respondent and the co-

Customs of Publicity

respondent, are, except to one reader out of thousands, the names

of strangers,

the idlest reader would lose nothing of his pastime if

the infamous were allowed

to be the anonymous. Nay, theirs are

names that, even published, will be soon

forgotten. They have

seldom the charm of the name of a Jane Cakebread, and they

are

published to please the briefest curiosity on the part of the world,

and

to inflict a long dismay upon the already wounded.

ALICE MEYNELL

At Twilight

(AFTER THE FRENCH OF CLAUDIUS POPELIN)

CLOSE thine eyes, O close thine eyes, my charming dove,

O close thine eyes, thine eyes so large, thine eyes so

kind,

And gently lean thy breast upon my breast, and wind

Around thy golden dreams, thy robe of satin, Love.

‘Tis growing late; the sun is low; the shades increase,

The gentle night that loves all lovers comes to us,

So softly, softly sleep and linger dreaming thus,

And I will guard thy flocks of dreams, upon my knees.

And thou wilt sleep beneath mine eyes, reclining there;

Already gentle zephyrs steal within the air,

And shining stars of love are moving in the skies.

Bye on! Sleep on! untiring I will watch thy sleep,

For long, for long, and see the golden dreams that creep

Quietly o’er thy moonlit face, with loving eyes.

MAURICE JOY

The Last Journey

ON a summer night, in the year of grace nineteen hundred

and

four, in the age of motor-cars and halfpenny papers,

of the Salvation Army and the

writings of Professor

Metchnikoff, a woman proved to her own, if not to her neigh-

bours’, satisfaction that wonders have not ceased, that enchant-

ments still

obtain, that the magic of ancient days is still true magic,

and that a country

stranger dan any mentioned by travellers in

Fairyland, is close at hand, lies just

beyond the world of every

day, can be reached easily from Piccadilly. For she

drove there

on the top of an omnibus.

She thought it would never come, as she stood what seemed

an

interminable time, near Piccadilly Circus. Omnibus after omni-

bus passed, but

never the one for which she waited.

“Here it is,” exclaimed someone behind her when her

weariness had grown almost insupportable; “it’s the last.”

Cecilia noticed vaguely, as it came swinging up, that the

horses were white, and with more distinctness that there was just

one seat vacant

immediately behind the driver. She hurried up

the steps, and sank into it with a

sigh of exhaustion.

A moment’s pause, and then with a jerk and a straining of

harness the horses started.

She glanced round her appreciatively as they began to move.

The Circus was very wonderful with its thousand lights.

A

yellow flood streamed from the Criterion. Great silver globes

hung against the

front of the Pavilion opposite. Silver globes

swung in the darkness of all the

radiating streets and thorough-

fares. Some of the lamps burnt with a pinkish

lilac flame, others

with gold, some with a hard white radiance. Everywhere the

dark-

ness was stained, flooded, streaked with light, or spotted with

points

of colour. It was beautiful; more beautiful than usual,

surely. “Oram I seeing it

better this evening?” she wondered.

Her eyes were so dazzled that it was not till the omnibus

had crossed the Circus, that Cecilia first noticed the loveliness of

the night.

The strip of sky overhead ran, a river of moonlit blue,

between the houses, deep,

soft, infinitely mysterious. It was,