XML PDF

Edith Nesbit

(1858 – 1924)

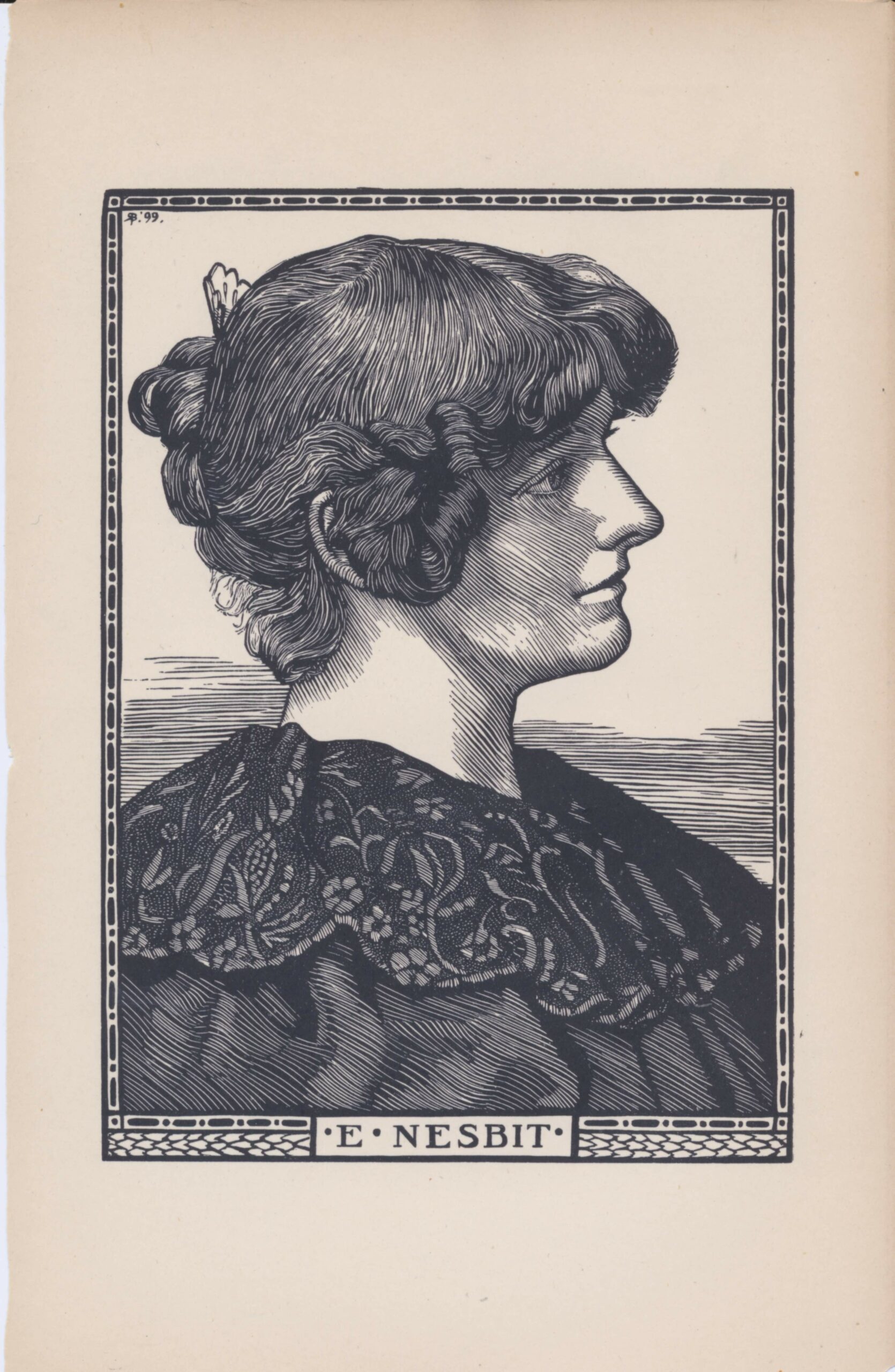

Edith Nesbit is remembered today as a popular and influential writer of Edwardian children’s literature. But she made her name as a prolific Victorian poet and short story writer, who wrote on horror, poverty, the New Woman, enchanted gardens and “marital discontent” (Murphy 497). Her fairy tales and ghost stories reached a wide audience. Her usual signature was E. Nesbit, sometimes leading early reviewers to assume male authorship. By the 1890s she had become a well-known figure in socialist, artistic, and literary circles, whose friends and acquaintances included radical writers and activists such as Olive Schreiner (1855-1920), Eleanor Marx (1855-98), Annie Besant (1847-1933), Dollie Radford (1858-1920), George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), H.G. Wells (1866-1946) and Richard le Gallienne (1866-1947).

Edith was the fifth child of teacher and chemist John Nesbit, who ran the Nesbit College of Agriculture and Chemistry in London. The college had been founded by his father and Edith’s grandfather Anthony Nesbit in 1841. Her mother Sarah had a daughter Saretta from a previous marriage, who remained close to her half-siblings (Fitzsimons 6-7). After her father died in 1862, Edith was raised in London and Brighton, before spending some of her childhood on the Continent in the attempt to improve the ill-health of her sister Mary Nesbit. Mary’s short-lived engagement to the poet Philip Bourke Marston (1850-87) brought the Nesbit family in contact with the Pre-Raphaelite circle. The Marstons were friendly with Ford Madox Brown (1821-93), William Morris (1834-96), and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-82) (Fitzsimons 27). Mary’s early death from consumption in 1871 ended the possibility of marriage but the family connections remained.

Nesbit married Hubert Bland (1855-1914) in 1879, giving birth to their first child two months later. She then became notorious for her unconventional household, which accommodated her husband’s lover Alice Hoatson and their two children as well as her own. She cut her hair short, wore loose-fitting Liberty gowns, and smoked incessantly, in adoption of what she considered “advanced” views (Briggs 84). Alongside her husband, Nesbit was one of the co-founders of the Fabian Society in 1884. Their brand of Fabian socialism included a commitment to bettering the conditions of the working class by fostering cross-class solidarity (Livesey 46-7). She spent most of her married life at Well Hall in Eltham, London, which was often thrown open to visitors from socialist, artistic, and publishing networks. The untimely death of her fifteen-year-old son Fabian Bland after adenoidal surgery in 1900 caused her much grief, but her enjoyment of her family, of playing games and hosting parties, continued into old age.

As a prolific contributor to fin-de-siècle journalism, Nesbit published short stories and poetry in Longman’s Magazine (1882-1905), Temple Bar (1860-1906), the Sketch (1893-1959), the Weekly Dispatch (1801-1928), Sylvia’s Home Journal (1878-94), the Sunday Chronicle (1885-1955), Argosy (1865-1901), Home Chimes (1884-94), the London Magazine (1875-9), the Pall Mall Magazine (1893-1917), the Woman’s World (1886-90) and the Illustrated London News (1842-2003) (Freeman 456; Briggs 464-74). She also illustrated and wrote verse for greetings cards, a lucrative industry in the Victorian period. Her story collections Grim Tales (1893) and Fear (1910) showed her flair for fashionably decadent tales of the supernatural. Critics concur that “the politics of Nesbit’s fiction remain under-examined” (Freeman 456); Melissa Edmondson’s new edition of her ghost stories (2024) will hopefully generate more research.

With her husband, Nesbit edited the socialist journal To-Day (1883-89) from 1885-88 and they published collaboratively under the name of “Fabian Bland.” In To-Day her New Woman-themed poems such as “The Husband of Today” and “The Wife of all Ages” were placed alongside the aesthetic poetry of Ernest Radford (1857-1919) and his wife Dollie Radford (1858-1920). Nesbit was also acquainted with Ernest’s sister and Yellow Book short story writer Ada Radford (1859-1934) and her Fabian husband Graham Wallas (1858-1932). Some of Nesbit’s work was published under her married name of Mrs Hubert Bland. Like Ada Radford, who usually published under her married name of Ada Wallas, it is likely that Nesbit chose to signal her socialist allegiances through using her husband’s name.

As editor of the Woman’s World, Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) had already admired and published Nesbit’s social protest poetry when she was invited to contribute to the Yellow Book (Fitzsimons 94). By the 1890s Nesbit’s poetry displayed the influence of aestheticism in its sensual decadent language and obsession with rich, gem-like colours. Alongside the appearance of two of Nesbit’s poems in the Yellow Book, John Lane (1854-1925) published her collection A Pomander of Verse (1895). This had an elaborate title page designed by Laurence Housman (1865-1959), who later illustrated some of her stories and acted in the Christmas dramas she staged for local children (Fitzsimons 133). Lane also published her short stories in Kentish dialect, In Homespun (1896), in his Keynotes series. He listed her alongside Alice Meynell (1847-1922), Rosamund Marriott Watson (aka Graham R. Tomson, 1860-1911), Katharine Tynan Hinkson (1859-1931) and Dollie Radford as one of the “five great women poets of the day” he was fortunate to have published in The Yellow Book (Barrie 6).

One outraged critic of the Yellow Book Volume 4 complained about the “indecent poems and stories [which] pander to a depraved taste” (“A Yellow Indecency”). Nesbit’s first Yellow Book poem “Day and Night” appeared in this volume alongside other poems of excessive nocturnal passion, such as “Rondeaux D’Amour” by Dolf Wyllarde (aka Dorothy Lowndes; 1871-1950) and “Vespertilia” Graham M. Tomson (aka Rosamund Marriott Watson). The longing for the night in women’s poetry can be read in terms of extra-marital desire (Adams 105). Nesbit’s second Yellow Book poem, “A Ghost Bereft” in Volume 12, draws on the technique of the ghost as speaker often used in late-Victorian ghost stories and in other Yellow Book lyrics by women writers. Marriott Watson’s “D’Outre Tombe” (Volume 10) addresses the lover from the grave: “I with the dead and you among the living,” a technique also deployed by Olive Custance (1874-1944) in “Pierrot” in Volume 13. Nesbit’s fascination with death and the silent house of secrets suffuses “A Ghost Bereft”: “What lurks in the silence that fills the room?” (111). Travelling through the wind and the rain, the ungendered ghost anticipates what it will find on looking through a past lover’s window, only to discover her dead body on a lily-draped bier: “Her body lies here deserted, cold; /And the body that loved it creeps in the mould” (112). The rhyming couplets, with their wind and rain refrain, establish a melancholy tone, reiterated through the repeated references to the sadness of the funereal lilies.

Nesbit’s decadent collection A Pomander of Verse also used ghosts as poetic personae. Imagery of coldness, death, and estrangement infuses “The Ghost,” in which the shrouded dead female body symbolises the unspoken importance of sexuality in marriage: “And on her narrow bed the rose /Is stark laid out in snow” (Pomander 46; Murphy 489-90). As in “The Ghost Bereft,” the “shrivelling” of flowers and hope gives a decadent atmosphere of decay and “the old despair” to the bedroom (46). Echoing the deathly voices in the poetry of Christina Rossetti (1830-94), “The Past” is spoken from the grave:

In the golden noon – by the lovers’ moon

My shadow bars your way

My shroud shows white in the blackest night

And grey in the gladdest day. (Pomander, 57)

Lilies and roses appear in many of these poems of enchantment, twilight, lush gardens, and spider queens.

Alongside Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), Nesbit became one of the star contributors to the long-running Strand Magazine (1891-1950), publishing fairy tales, ghost stories and serialised fantasy fiction for children between 1899 and 1915. Her enduringly popular novels The Psammead (1902; later published as Five Children and It), The Phoenix and the Carpet (1903-04), and the Egyptian-themed The Story of the Amulet (1905-06) helped to boost sales of this illustrated family magazine. Featuring evil scientists, unearthly catacombs, and mock-Gothic haunted houses, her chilling ghost stories “The Haunted House,” “The Three Drugs,” “The House of Silence,” and “The Power of Darkness” typify the clash between science and spiritualism in the Strand’s pages (Liggins 22-3). Stories worth rereading include the Rapunzel variant “Melisande” (1901) and her foray into plant horror “The Pavilion” (1915), in which a magic Virginia creeper strangles male victims who scoff at the supernatural.

In later life Nesbit continued to publish fiction for both adults and children. She also edited and wrote stories and drama for a new little magazine The Neolith (1907-08), which also published work by Laurence Housman, George Bernard Shaw and up-and-coming Anglo-Irish fantasy writer and dramatist Lord Dunsany (Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett) (1878-1957). With its blend of pictorial and literary work, the Neolith resembled the Yellow Book and was influential in the establishment of lithography in Britain, though Nesbit explicitly stated that she wanted “no Yellow Book suggestiveness” for her new periodical (Fitzsimons 210). Her socialist intentions found a new outlet in the sale of fruit, vegetables, and eggs to local families and her hosting of garden parties for local children during the war. Three years after Hubert Bland’s death in 1914, she married a family friend from socialist circles, the marine engineer Thomas Terry Tucker. She died in 1924, possibly of lung cancer. A Strand celebrity portrait of 1905 celebrated her versatility, singling out her energy and enthusiasm for the socialist movement, her “revolutionary” early poems, and her well-known children’s stories “with their almost uncanny insight into the psychology of childhood” (“Portraits” 288). Nesbit’s stories and poems are certainly worth reconsidering for their dissident views and decadent, death-laden imagery.

©2024, Emma Liggins, Reader in English and Co-Director of the Manchester Centre for Gothic Studies, Manchester Metropolitan University, United Kingdom.

Selected Publications by E. Nesbit

- Lays and Legends. Longmans, Green & Co, 1886.

- Grim Tales. London, A.D. Innes & Co, 1893. Short stories originally published in Longman’s Magazine, Temple Bar, Argosy, Home Chimes and Illustrated London News.

- “Day and Night.” The Yellow Book, vol. 4, January 1895, p. 260. Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Yellow Nineties 2.0, https://1890s.ca/YBV4_nesbit_day/

- A Pomander of Verse. John Lane, The Bodley Head,

1895.

https://archive.org/details/cu31924013437698/page/n7/mode/2up

- In Homespun. John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1896.

- “A Ghost Bereft,” The Yellow Book, vol.12, January 1897, pp. 110-112. Yellow Nineties 2.0, https://1890s.ca/YBV12_nesbit_ghost/

- Songs of Love and Empire. Constable & Co, 1898.

- Five Children and It. T. Fisher & Unwin, 1902.

- Phoenix and the Carpet. London: George Newnes; New York: Macmillan, 1904.

- The Railway Children. London: Wells, Gardner, Darton & Co; New York: Macmillan, 1906.

- The Story of the Amulet. T. Fisher & Unwin, 1906.

- Ballads and Lyrics of Socialism, 1883 to 1908 (published for the Fabian Society). A.C. Fifield, 1908.

- Daphne in Fitzroy Street. George Allen & Sons, 1909.

- Fear. Stanley Paul & Co, 1910. Short stories previously published in the Strand Magazine.

Selected Publications about E. Nesbit

- Adams, Jad, Decadent Women: Yellow Book Lives. Reaktion Books, 2023.

- “A Yellow Indecency.” Review of The Yellow Book, vol. 4, January 1895, The Critic 16 January 1895, p. 131. Yellow Nineties 2.0, https://1890s.ca/yb4-review-critic-feb-1895/

- Barrie, J. M. “A Publisher of Minor Poets: A Chat with Mr. John Lane.” The Sketch, 4 December 1895, p. 6.

- Briggs, Julia. E. Nesbit: A Woman of Passion. Hutchinson, 1987.

- Edmondson, Melissa (ed.). E. Nesbit, The House of Silence: Ghost Stories, 1887-1920, Handheld Press, 2024.

- Fitzsimons, Eleanor. The Life and Loves of E. Nesbit. Duckworth, 2019.

- Freeman, Nick. “E. Nesbit’s New Woman Gothic,” Women’s Writing, vol. 15, no 3, 2008, pp. 454-69.

- Liggins, Emma, “The Edwardian Supernatural.” Twentieth-Century Gothic, edited by Sorcha Ni Fhlainn and Bernice Murphy, Edinburgh University Press, 2022, pp. 15-32.

- Livesey, Ruth. Socialism, Sex and the Culture of Aestheticism in Britain, 1880-1914, Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Murphy, Patricia. “A State of Discontent and Dismay: E. Nesbit dissects Victorian Marriage,” Victorian Poetry, vol. 58, no. 4, 2020, pp. 475-500.

- “Portraits of Celebrities at Different Ages: No VIII, Mrs Hubert Bland (‘E. Nesbit’),” Strand Magazine, vol. 30, September 1905, pp. 286-88.

MLA citation:

Liggins, Emma. “Edith Nesbit (1858-1924),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2024. https://1890s.ca/nesbit_bio/.