XML PDF

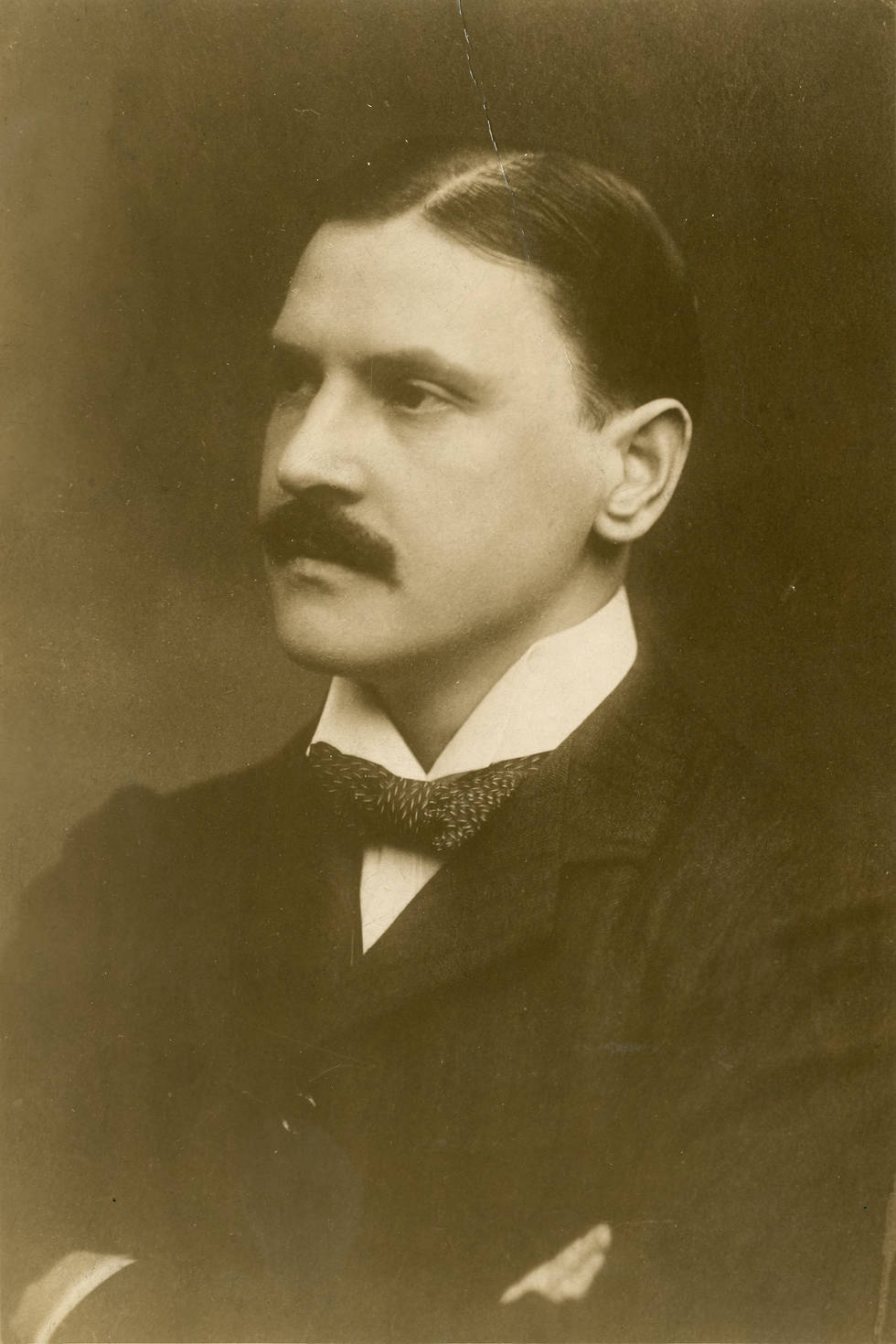

W. Somerset Maugham

(1874 – 1966)

In his day, William Somerset Maugham was one of the most famous, and wealthiest, writers in the world. Incredibly prolific, he was at home in almost every genre, except poetry—“I am not a poet,” he confessed in a 1903 letter to Laurence Housman (1865–1959) (Housman Papers). By all accounts, his prolific output was a remarkable feat, for the writer had started out as a boy with a stammer and poor English. Maugham in fact grew up speaking exclusively French. He had been born at the British Embassy in Paris, where his father was a lawyer, so as to sidestep a local law that made all boys born on French soil eligible for conscription. The writer reportedly only learned English from having to read police court news in The Standard out loud to a clergyman at the embassy church (Summing Up 13).

Of his parents, Maugham once noted: “I know little of them but from hearsay” (Summing Up 10). Orphaned at an early age, the boy was sent abroad for his education, first to the King’s School in Canterbury and then to the University of Heidelberg. In 1892, the author entered St Thomas’ Hospital in London to train as a physician, often penetrating deep into the city’s working-class districts to provide medical services. These experiences fed into his first novel, Liza of Lambeth (1897), the naturalistic story of a young woman in a slum. “I do not know a better training for a writer than to spend some years in the medical profession,” Maugham later claimed (Summing Up 43). He took to writing “as a duck takes to water” (Summing Up 9). After the publication of Liza, Maugham’s early fiction followed in quick succession, including a short story collection, Orientations (1899), and novels, The Making of a Saint (1898), The Hero (1901) and Mrs Craddock (1902). Turn-of-the-century London was a great place to be a young writer. The period witnessed the founding of publishing houses such as Heinemann, Hutchinson, Methuen, T. Fisher Unwin and the Bodley Head. With so many new publishers around, looking for young talent to fill their rosters, it had become easier to see one’s work to print. Of this opportunity, his biographers show, Maugham made eager use.

In the final years of the nineteenth century, Somerset Maugham began submitting stories not to avant-garde magazines, but to more established, mainstream titles. These were the kinds of middle-brow publications with which his career would come to be associated. Upon rejecting an early manuscript, Edward Garnett (1868–1937), then a reader at Unwin, advised the inexperienced author “to try the humbler magazines for a time” (qtd. Secret Lives 53). Maugham’s early stories were published in Cosmopolis (1896–98), a short-lived, trilingual magazine printed in English, German, and French; Black & White (1891–1912), a London-based illustrated periodical; and Punch (1841–2002), the satirical political weekly. Some of these early stories in Punch, including “Cupid and the Vicar of the Swale” and “Lady Habart,” both published in 1900, would later be reworked and expanded into novels and plays.

In 1903, Maugham was himself asked to edit a magazine, The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature, together with Laurence Housman. The nature of the request—Maugham was apparently “invited” (Secret Lives 88); Housman, too, was “asked to edit” (Unexpected Years 202)—remains vague. It likely came through John Baillie (1868–1926), the magazine’s publisher who also owned a gallery, where both editors would meet on occasion (Kooistra, General Introduction to The Venture) While the precise details are unclear, it is evident that this turn to editorship was a unique move for Maugham. Unlike the mainstream magazines in which his early work had appeared, The Venture was an avant-garde publication. The annual anthology had a limited readership, and was only published twice: in 1903 (printed at the Pear Tree Press) and in 1905 (printed at the Arden Press).

Together, Maugham and Housman actively sought out literary contributors, with the latter casting himself in the role of lead editor (as two surviving letters in the Housman papers at Bryn Mawr College suggest). Both men were new to editorial work. Still, by relying on their networks, they managed to gather a cast of budding and established voices, including John Masefield (1878–1967), Thomas Hardy (1840–1928), Alice Meynell (1847–1922), Laurence Binyon (1869–1943), A. E. Housman (1859–1936), T. Sturge Moore (1870–1944), E. Gordon Craig (1872–1966) and James Joyce (1882–1941). None of these contributors ever received payment for their work. Maugham also asked his co-editor if he might contact Pearl Craigie (1867–1906), Richard Price, Laurence Hope (1865–1904), and Alfred Pollock, but these writers never made it into the anthology. He did recruit Violet Hunt (1862–1942), his lover at the time, who would later also be associated with the English Review (1908–37).

Maugham himself contributed a piece to The Venture which in a letter to Housman he described as “my little play” (Housman Papers). “Marriages are Made in Heaven” had been written in 1896, while its author was still a medical student at St. Thomas’s Hospital. The one-act play, a curtain-raiser influenced by Henrik Ibsen and Oscar Wilde, turns to a dominant trope in Maugham’s oeuvre: marriage. It brings the story of Lottie Vivyan, a handsome woman who receives a large sum from a former lover and, newly of means, plans to marry Jack Raynor, a poor Oxford graduate and Boer War veteran. The couple is warned that the marriage will prove socially ruinous for both, but they refuse to part ways. Under the title of Schiffbruchig (Shipwrecked), the play was performed a dozen times, between January and May 1902, in an avant-garde cabaret theatre in Berlin. Maugham then recycled the text for publication in the first issue of The Venture, where it appeared alongside Violet Hunt’s play “The Gem and Its Setting.” It was to be the second of his plays in print; earlier that year, A Man of Honour had appeared in a supplement to the prestigious Fortnightly Review (1865–1954).

The Venture folded after only two issues. It had made no profits—an unwelcome fact at a time when Maugham was continually strapped for cash. As Housman put it in his memoir: “The whole thing was, of course, too highbrow to be popular: perhaps had it been published at a guinea instead of at five shillings, it would have done better” (Unexpected Years 203). A respectable figure at the time, but in no way famous, Maugham had made an unlikely editor to begin with. “Around the years that ended the old century and began the new one I was looked upon as a clever young writer,” he recalled in old age, “rather precocious, harsh and somewhat unpleasant, but worth consideration” (Summing Up 116). It is unclear who sought out Maugham for the task, and he never edited a magazine or anthology again. Unlike Housman, who had known Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) and had contributed to The Dial (1889–97), The Pageant (1896–97), and The Yellow Book (1894–97), Maugham must have been a bit out of his element in the avant-garde, aesthetic circles of the little magazines and their coteries. In 1938, he wrote, in a characteristically misogynistic vein:

If one takes the trouble to look through the volumes of The Yellow Book, which at that time seemed the last thing in sophisticated intelligence, it is startling to discover how thoroughly bad the majority of its contributions were. For all their parade these writers were no more than an eddy in a backwater and it is unlikely that the history of English literature will give them more than a passing glance. I shiver a little when I turn those musty pages and ask myself whether in another forty years the bright young things of current letters will appear as jejune as do now their maiden aunts of The Yellow Book. (Summing Up 117)

Despite these later claims, Maugham was still something of an aesthete in the early years of the 1900s. He was shy by nature, yet developed close relationships with people much more at home in bohemian circles, including Robert Ross (1869–1918), Wilde’s first lover; Max Beerbohm (1872–1956); Mabel Beardsley (1871–1916) and Ada Leverson (1862–1933), who used to compare Maugham to Wilde, and wrote him into one of her novels (Encyclopedia 310). For a short time in Paris in 1904, the writer also saw a good deal of Ella D’Arcy (1857–1937), whose stories had appeared in The Yellow Book.

After The Venture, but likely not because of it, Maugham’s career shifted up a gear. He made a name and a fortune for himself as a playwright, composing dozens of plays in the span of a few crowded years. In 1908 he had four successful plays running in the West End, including Lady Frederick, his big break. 1915 saw the publication of a novel that was quickly recognised as his masterpiece: Of Human Bondage. By that year, Maugham had begun to spend more time abroad than in Britain, a place to which he felt “attached” but where he was “never […] at home” (Summing Up 66). Though married (and eventually divorced), Maugham was a homosexual, and a life abroad also offered a way to avoid the aftermath of the Wilde trials. Indeed, so well-travelled was the novelist that he became synonymous with the waning years of British imperialism—his chosen subject. As a rule, Maugham travelled with his “secretary-companion,” Frederick Gerald Haxton (1892–1944), a former advertising manager at the London Times who was his long-time partner. The sights and scenes both men encountered across the globe became fodder for Maugham’s fiction. In 1916, after a spell with the Red Cross in the First World War, Maugham and Haxton travelled to the South Pacific, which inspired The Moon and Sixpence (1919) and The Trembling of a Leaf (1921). A joint journey to Hong Kong and into China, in 1919, resulted in On a Chinese Screen (1922) and The Painted Veil (1925).

Maugham’s stories of the period wrestle with themes already apparent in his early work from the late 1890s: observations on social mores, marriage and love, often written in a tragic vein. In part or wholesale, many of these stories first appeared in the periodical press, though not in little magazines such as The Venture. Maugham preferred the leading middlebrow periodicals; he often came to the defence of these magazines, and especially the kind of popular fiction contained within their pages:

to describe a story as a magazine story is to dismiss it with contumely. But when the critics do this they show less acumen than may reasonably be expected of them. Nor do they show much knowledge of literary history. For ever since magazines became a popular form of publication authors have found them a useful medium to put their work before readers. All the greatest short story writers have published their stories in magazines, Balzac, Flaubert and Maupassant; Chekhov, Henry James, Rudyard Kipling. (Creatures of Circumstance 2)

Maugham published his work on both sides of the Atlantic, in periodicals such as The Bookman (1891–1934), Good Housekeeping (1885–), Life and Letters (1928–35), Nash’s Magazine (1904–37), Pearson’s Magazine (1896–1939), The Saturday Evening Post (1821–1969), and The Smart Set (1900–30), among others. Many of these pieces, especially the early ones, were placed by his agent, J. B. Pinker (1863–1922). Income was the driving force. “Has the Lady’s Realm or whatever it was stumped up?” Maugham asked his agent from abroad in July 1906: “This is the season when my tailor & hatter send in bills” (qtd. Secret Lives 109).

Quickly, such concerns would be a thing of the past. Somerset Maugham became one of the richest men in contemporary letters, with a vast fortune amassed through his plays put on in the West End and further increased through television and film adaptations of his fiction. In 1934, Greta Garbo and Bette Davies starred in Hollywood adaptations of The Painted Veil and Of Human Bondage. Later successful publications included novels such as Cakes and Ale (1930), Up at the Villa (1941), and The Razor’s Edge (1944), as well as a spate of autobiographies, including The Summing Up (1938), Strictly Personal (1941), and A Writer’s Notebook (1949). In fact, across his career, Maugham’s work had been lifted from life. “In one way or another,” he tellingly confessed, “I have used in my writings whatever has happened to me in the course of my life” (Summing Up 1).

When not travelling, Maugham made a home for himself on the French Riviera, at the Villa Mauresque on Cap Ferrat, which the Belgian King Leopold II (1835–1909) had constructed with ill-gotten gains from the Congo. It is here that the writer spent his final years. By the time of his death, at the Anglo-American Hospital in Nice in December 1965, Maugham had been awarded a long list of honorary titles and degrees, had donated his manuscripts to institutions across Europe and the U.S. and had established the Somerset Maugham Award, which funds travel for young authors to this day. He was cremated in Marseilles.

©2022 Cedric Van Dijck, postdoctoral fellow in English Literature at the University of Brussels (VUB). He is the author of Modernism, Material Culture and the First World War (forthcoming with Edinburgh University Press), and a co-editor of the Edinburgh Companion to First World War Periodicals (2023) and The Intellectual Response to the First World War (2017).

Selected Publications by W. Somerset Maugham

- Liza of Lambeth. Heinemann, 1966.

- Orientations. Unwin, 1899.

- The Making of a Saint. Floating Press, 2012.

- The Hero. Floating Press, 2012.

- Mrs Craddock. Heinemann, 1967.

- “Marriages are Made in Heaven.” The Venture, vol. 1, 1903, pp. 209-30.

- Of Human Bondage. Heinemann, 1966.

- The Moon and Sixpence. Heinemann, 1961.

- The Trembling of a Leaf. Heinemann, 1967.

- On a Chinese Screen. Heinemann, 1969.

- The Painted Veil. Heinemann, 1967.

- Cakes and Ale. Heinemann, 1966.

- Up at the Villa. Heinemann, 1966.

- The Razor’s Edge. Heinemann, 1967.

- The Summing Up. Heinemann, 1971.

- Creatures of Circumstance. Heinemann, 1954.

- Strictly Personal. Heinemann, 1942.

- A Writer’s Notebook. Heinemann, 1964.

- Collected Short Stories, vol. 1-4. Vintage, 2000–2.

- The Plays of Somerset Maugham, vol. 1-6. Heinemann, 1931–34.

Selected Publications about W. Somerset Maugham

- Aldington, Richard. W. Somerset Maugham: An Appreciation. Doubleday, 1939.

- Connon, Bryan. “Maugham, (William) Somerset.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed 8 August 1922: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-34947;jsessionid=6281B71E7D0E6A60A51095470AA1927D

- Curtis, Anthony and John Whitehead, editors. W. Somerset Maugham: The Critical Heritage. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987.

- Hastings, Selena. The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham. John Murray, 2010.

- Housman, Laurence. The Unexpected Years. Jonathan Cape, 1937.

- Laurence Housman Papers, Bryn Mawr College: Box 2, Folder 16 (two letters by Maugham to Housman about The Venture)

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “General Introduction to The Venture: An Annual of Art and Literature.” Yellow Nineties 2.0.

- Maugham, Robin. Conversations with Willie: Recollections of W. Somerset Maugham. W.H. Allen, 1978.

- Raphael, Frederick. Somerset Maugham and His World. Thames & Hudson, 1976.

- Rogal, Samuel J. A William Somerset Maugham Encyclopaedia. Greenwood Press, 1997.

MLA citation:

Van Dijck, Cedric. “W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1966),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/maugham_bio/