XML PDF

The name Stanley Victor Makower rarely sparks recognition, even amongst literary scholars familiar with fin-de-siècle literature and print culture. Yet the music critic and writer of fiction was a well-respected figure, and his literary contributions won him esteem amongst some of the period’s best-known figures, including Oscar Wilde. Makower authored The Mirror of Music (1895), one of the most curious and unfairly neglected novels of the period, and his frequent contributions to The Yellow Book include fiction and non-fiction, much of which concerns unusual musical figures and themes.

Makower was born on the 20th of June 1872 in Marylebone, London. He was the son of Polish Jewish immigrants—Moritz Makower and his wife Jessie (née Isaacs)—who arrived in England after fleeing religious persecution in the 1850s. Makower was educated at Trinity College Cambridge, where he studied law (Bassett 2023). Although he was called to the bar, it would appear he never practised. Instead, he turned to literature and published his first short story in collaboration with fellow Cambridge classmates, Oswald Sickert and Arthur Cosslett Smith (Lasner 1998). Published by T. Fisher Unwin’s Pseudonym Library, The Passing of a Mood (1893) is a collection of short stories that explores the transient and ephemeral nature of human experiences and emotions. As its title implies, the purpose of this series was to provide a platform for authors to publish works under pseudonyms, allowing them to explore different genres or writing styles without being tied to their established identities. This collection could offer insights into the versatility and creativity of these writers beyond their known personas. The trio signed their names, V., O., and C.S. (Makower, Sickert, and Smith). Makower, Sickert, and Smith went on to collaborate on “Three Stories,” published in volume 2 of The Yellow Book under the same initials, each writing one of the three. Makower’s contribution was the third short story, “Sancta Maria,” which narrates the experiences of a young woman named Maria who is deeply devoted to her Roman Catholic faith. The narrative delves into Maria’s internal struggles and the challenges she faces as she navigates her unwavering beliefs in a modern world that often conflicts with traditional religious values.

Later that year, Makower published an article in The New Review under his own name. “Reminiscences of Bülow” was written in memory of the late German pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow (1830-1894). Although it is not currently known where Makower obtained his musical training, it is certain that he used it to his advantage in his music journalism and fiction writing.

“A Beautiful Accident” was the first short story published under his own name in The Yellow Book, volume 6 (July 1895), and his first novel The Mirror of Music (also under his own name) was published in John Lane’s Keynote Series in 1895. Oscar Wilde, who was one of Makower’s prominent correspondents, wrote to him to praise the book:

My Dear Stanley, I think your book intensely interesting: a most subtle analysis of the relations between music and a soul. I know nothing else in literature where this motif is treated with anything like your skill of analysis and power of presentation. (Wilde)

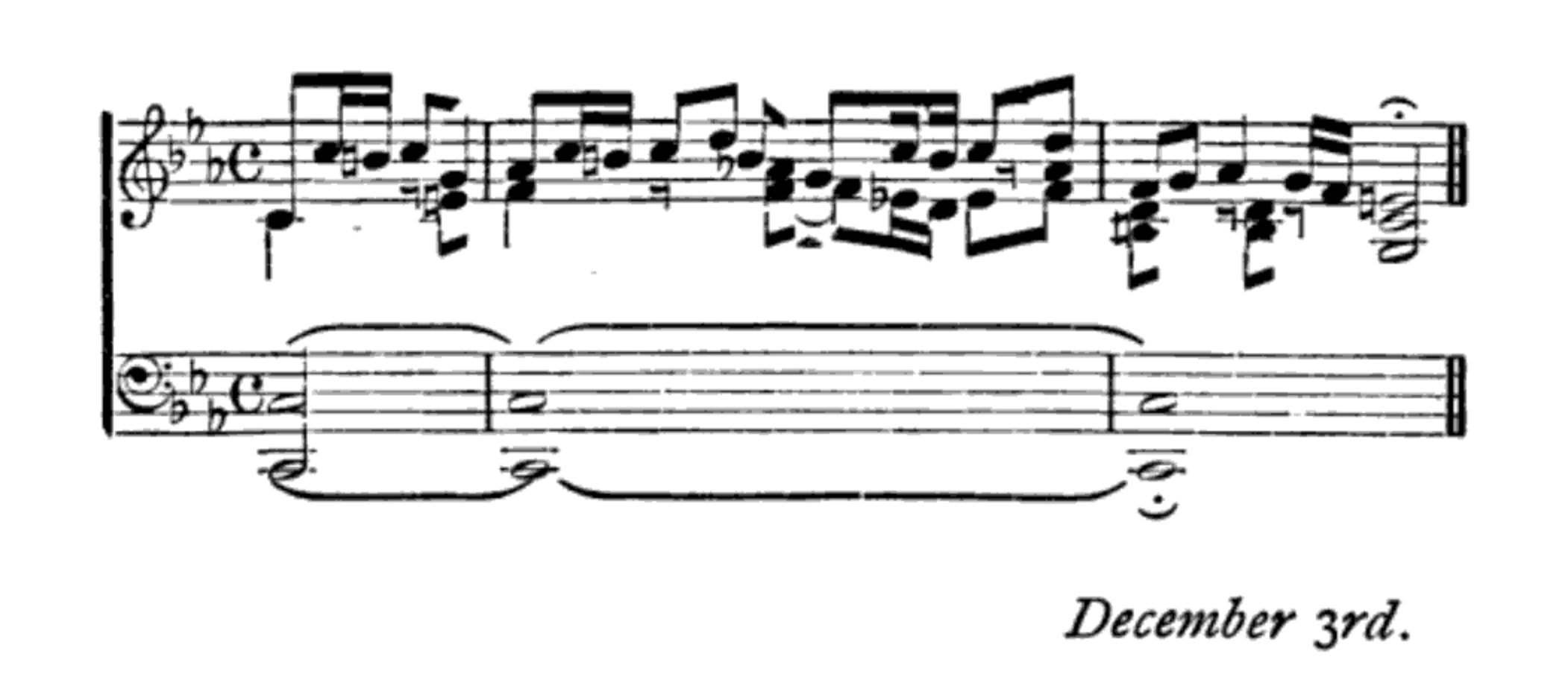

Makower dedicated his novel to the French cabaret singer Yvette Guilbert (1865-1944), an internationally celebrated figure who had several well-known devotees, including Sigmund Freud and George Bernard Shaw. Makower had the pleasure of seeing Guilbert perform at The Empire music hall in London in 1894 and she later became a correspondent. Makower’s veneration of Guilbert is conspicuous in his article, “On the Art of Yvette Guilbert,” published in The Yellow Book, volume 9 (April 1896). In it, he writes “of the extraordinarily vivid effect of physical violence which Yvette Guilbert conveys by the use of sounds—which cannot be spelt. She really manufactures a language of her own which no one could talk but which everyone understands” (76). Some pages later he writes: “her face bears in it the irregularities of genius, and moreover it never seems to look the same twice running. It has in it something insaisissable, something which evades the precision of mental as well as actual portraiture” (81). Although Makower’s assessment of Guilbert’s genius is itself somewhat impressionistic, the implication of these words is that Makower believes Guilbert’s ability to move the British public in her performance effectively short-circuits language. Of course, on a practical level this meant that those unfamiliar with the French language could access meaning through Guilbert’s emotive expression. More than this, though, her “use of sound” becomes, for Makower, a kind of universal language of emotion (76).Makower may well have imagined himself enacting a similar function in his writing through the inclusion of musical notation. The Mirror of Music is a novel about the intricate psychological experiences of a female composer named Sarah Kaftal. The story opens at a London gentleman’s club where a group of men are discussing the career of Kaftal with much derision. The homosocial discourse of what initially appears as a typical “club narrative” breaks down as the reader is granted privileged access to Kaftal’s voice through her diary entries. Through this means, Makower explores the complexities of the protagonist’s inner world, focusing on her experiences, emotions, and interactions as a musician. In Kaftal’s diary entries, Makower uses musical notation to allow the reader to imagine hearing the music rise from the page (fig. 1).

Makower used his fiction to champion the cause of women. Literary Decadence, to which movement he arguably belongs, is not the obvious vehicle for such treatment, given the charge that it was often misogynistic. Elaine Showalter argues that the male decadent defined himself against the feminine and biological creativity of women, portraying women as objects of value only when they were anesthetized as corpses or phallicised as femme fatales (Showalter 1993). With its perverse fascination in the female composer’s decline and profound meditation on the sensory effects of music and aesthetic experience more generally, The Mirror of Music exhibits many hallmarks of Decadent writing. However, Makower’s writing has commonalities with female Decadent authors, such as George Egerton and Vernon Lee, for whom “a key point of contention [. . .] had been the tendency of men […] to depict women as little more than objects of desire or symbols of sexual aberrancy and decay” (Denisoff 48). In short, Makower’s writing is attuned to, and subverts, the misogynistic tropes we so often encounter in this movement.

Despite his not being frequently named among the most prominent writers in The Yellow Book, Makower appeared in six of its thirteen volumes, making him one of the more regular contributors. “Chopin. Op.47,” published in volume 11 (October 1896), is a short story about a female pianist. Makower’s obsession with the female creative genius was indeed a recurring theme within his work. In 1897, he published his second novel, Cecilia: The Story of a Girl and some Circumstances, again with John Lane. The book describes the plight of a talented vocalist who is manipulated by her scheming mother into securing a match which will elevate their position in society. In this novel, Makower is particularly concerned with what might be described as a form of genteel poverty, and the anxieties that emerge out of various forms of social performance. Whether his characters hide their national identity or take pains to conceal the small privations which threaten to cast them to the fringes of respectable bourgeois society, there is always a sense of the need to perform “other” versions of oneself. Makower takes further steps to redefine and recover his Jewish heritage by repudiating the stereotypical Jewish caricature that was so prominent in novels at the time. In the 1850s, his parents had migrated from the Polish town of Maków, which was at that time a province of the Russian empire. The Russians authorities were conducting an ethnic cleansing of the area, and Jewish families were forced to flee west. At that time, many did not have surnames, but used patronymics. The family name Makower would have been given to them at the German border as this was a compulsory stipulation. Cecilia registers this complicated experience of displacement and social performance and unites it with a sympathetic exploration of gendered oppression which similarly demands the enactment of restrictive social roles.

Makower’s last publication in the Yellow Book was “Three Reflections” in January 1897. It revolves around the lives of three individuals who are each facing a moment of crisis and must reflect on their past actions and decisions. As they contemplate their past, they come to realisations about themselves and their relationships with others.

In 1905 Makower married Maria Agnes Brügger, whom he had met while visiting Switzerland; they went on to have four children. Makower continued to write about female artists. His lengthy novel, Perdita: A Romance in Biography (1908), is a fictionalised biography of the once celebrated poet, novelist, and actress Mary Robinson (1756–1800), who controversially was a mistress of the Prince of Wales, among others. In 1909 he published a further historical study of the poet, pamphleteer, and carousing friend of Samuel Johnson, Richard Savage: A Mystery in Biography.

Makower died in 1911 from pernicious anaemia at the age of thirty-nine and was buried in Chiswick Old Cemetery in West London. His main contribution to fin-de-siècle literature was his skill in applying the emotive power of music to signpost the journeys of his female characters while at the same time discussing the necessity for social performance, and women’s changing roles in society.

©2024, Suzy Corrigan.

Suzy Corrigan is an AHRC-funded PhD student at Teesside University and in the early stages of her research. She is interested primarily in music and cosmopolitanism in late-nineteenth and early twentieth century women’s writing, particularly Vernon Lee. As a mature student, Suzy has recently returned to academia after a successful career in performing arts, where her theatrical experience provided her with an insight into the act of musical performance.

Selected Publications by Stanley V. Makower

- “Reminiscences of Bülow.” The New Review, December 1894, pp. 647-654.

- “A Beautiful Accident.” The Yellow Book, vol. 6,

July 1895, pp. 297-306. Yellow Book Digital Edition,

edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2010-2014. Yellow Nineties 2.0 rev. ed., Toronto Metropolitan

University Centre for Digital Humanities 2020.

https://1890s.ca/ybv6_makower_beautiful/

- The Mirror of Music. John Lane, 1895.

- “Chopin Op. 47.” The Yellow Book, vol. 11, October

1896, pp. 250-258. Yellow Book Digital Edition, edited

by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow

Nineties 2.0.

https://1890s.ca/YBV11_makower_chopin/

- “On the Art of Yvette Guilbert.” The Yellow Book,

vol. 9, April 1896, pp. 60-81. Yellow Book Digital

Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0.

https://1890s.ca/YBV9_makower_guilbert/

- Makower, Stanley V. “Three Reflections.” The Yellow

Book, vol. 12, January 1897, pp. 113-137. Yellow

Book Digital Edition, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen

Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0.

https://1890s.ca/YBV12_makower_three/

- Cecilia: The Story of a Girl and some Circumstances. John Lane, 1897.

- “Man and Woman as Concert-Goers.” The Speaker: The Liberal Review, 8 December 1906, pp. 294-295.

- Perdita: A Romance in Biography. Hutchinson, 1908.

- Richard Savage: A Mystery in Biography. Hutchinson, 1909.

- A Book of English Essays (1600-1900). Selected by Stanley V. Makower and Basil H. Blackwell. Oxford University Press, 1912.

Works Cited

- Bassett, Troy J., “Author: Stanley Victor Makower.” At The

Circulating Library: A Database of Victorian Fiction, 1837—1901, 25 June

2023,

http://www.victorianresearch.org/atcl/show_author.php?aid=2617, accessed 16 May 2024.

- Denisoff, Dennis. “Decadence and Aestheticism.” The Cambridge Companion to the Fin de Siècle, edited by Gail Marshall, Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp. 31-52.

- Lasner, Mark Samuels. The Yellow Book: A Checklist and Index, Occasional Series No. 8, The 1890s Society, 1998.

- Showalter, Elaine. “Introduction.” Daughters of Decadence: Women Writers of the Fin de Siècle, Virago Press Limited, 1993.

- Wilde, Oscar. Letter to Stanley V. Makower, 27th September 1897. Makower family archive, London. Box 4. With kind permission of the Makower family.

MLA citation:

Corrigan, Suzy. “Stanley V. Makower (1872 – 1911),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2024. https://1890s.ca/makower_stanley_bio/.