XML PDF

Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf

No. 5, 1903

Keying to September’s autumnal tints, Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951) draws on red, yellow, and green to offset the duller tones of gray, beige, and khaki in her hand-coloured images for the fifth monthly number of The Green Sheaf (fig. 1). Notably missing are blue and purple, which, with green, red, and yellow, comprise the five primary hues in the Munsell colour system Smith learned while studying with Arthur Wesley Dow (1857-1922) at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn (Dow 102). Smith’s use of colour is always intentional and symbolic. In addition to colour theory, she incorporated her own synesthetic perceptions and developed original pigments to express her visual ideas. This aspect of her art was highlighted in contemporary reviews. In a feature story on Smith published in the American magazine The Reader at about the same time as The Green Sheaf’s fifth number came out, the critic noted: “her colors and color-schemes are all her own. Though fantastically fanciful and in a way impossible, the blendings always please. From recipes which she has evolved, she herself prepares many of the unusual shades which she employs, adding more individuality to the general effect thereby” (“Writers and Readers,” 332). In Green Sheaf No. 5, Smith employs her artistic and editorial skills to explore the experience of the idiosyncratic individual facing a moment of decisive change, for good or for ill.

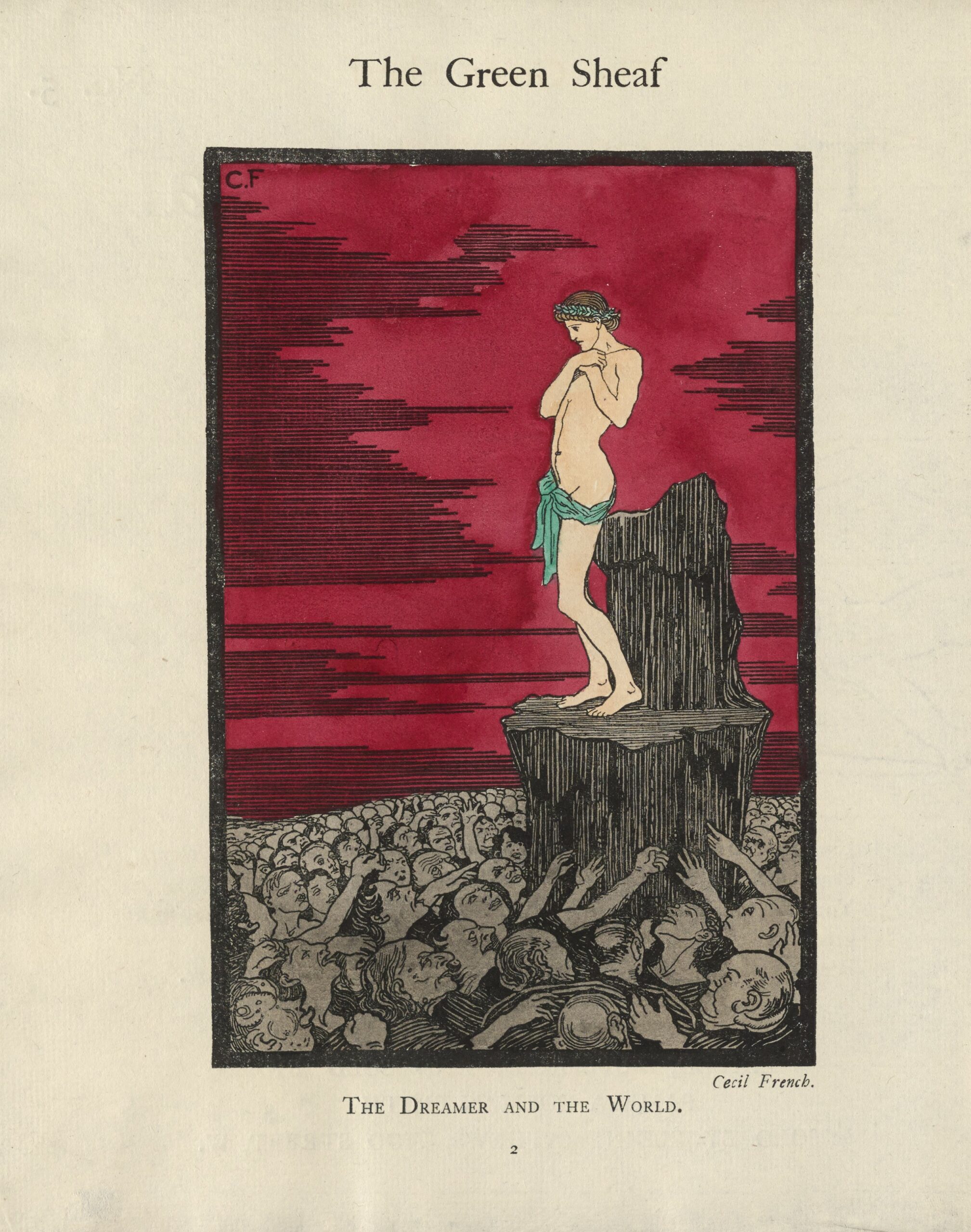

The issue’s thematic keynote is established in the dramatic opening image, “The Dreamer and the World,” by The Green Sheaf’s regular Irish contributor, Cecil French (1879-1953). Luminously vulnerable against a lurid red sky, a naked figure swaddled in a green loin cloth and wearing a laurel wreath is perched on a standing stone above a dense and jeering mob (fig. 2). With downturned chin resting on clasped hands, the androgynous figure seems to represent the dreamer who is mocked for seeing life differently and taking an idiosyncratic path. Across the double-page opening, Smith places “Cael and Credhe,” the second and final contribution to The Green Sheaf by Irish Revivalist Lady Augusta Gregory (1852-1932). Gregory translates a traditional Irish tale about the Fenian warrior Cael, who sees Credhe the Beautiful in a dream, then woos and wins the Sidhe princess through poetry and song. Smith positions her hand-coloured illustration at the end of Gregory’s three-page story. The dramatic image depicts the hero and his leader, Finn, knocking on the hillside door of the Sidhe with their long-shafted spears, while their army waits below (P. Smith, “Cael and Credhe,” 5). The picture recalls the moment of cliff-edge decision, with the outcome yet to be decided, introduced in French’s opening image (fig. 2).

French’s other contributions to the issue elaborate on this motif. His lyric speaker in “The Turning of the Tide” considers “triumph” and “failure” in terms of “Fate’s ebb and flow” (French 11). In the layout, Smith balances French’s three couplets on the bottom of the page with two tercets of her own at the top; her subject is the cyclical nature of “Time,” which knows “every secret” (P. Smith 11). French also supplies a pictorial initial for “Will o’ the Wisp,” by Leslie Moore (aka Ida Constance Baker, 1888-1978). This is the only Green Sheaf contribution by the fifteen-year-old author, who was then attending school in London with her life-long friend and sometime lover, the New Zealand born writer Katherine Mansfield (1888-1923), who renamed her “Leslie Moore” or, simply, “L.M.” (Murry 177, 185; Moore, Katherine Mansfield). Moore’s story retells a common Irish folktale about the ignis fatuus (“foolish fire”), swamp gasses said to mislead travellers by appearing to be flickering lights. Separating interior from exterior, human from supernatural, French’s Initial “T” is set into a window frame, out of which a child reaches toward the ghostly light in the swamp below. That glimmer, he knows, is “the soul of his little sister who had died unbaptized” (Moore and French 13). Unlike Gregory’s tale, where the protagonist’s decision leads to a wedding feast, Moore’s story ends grimly, with the main character’s disappearance and assumed death.

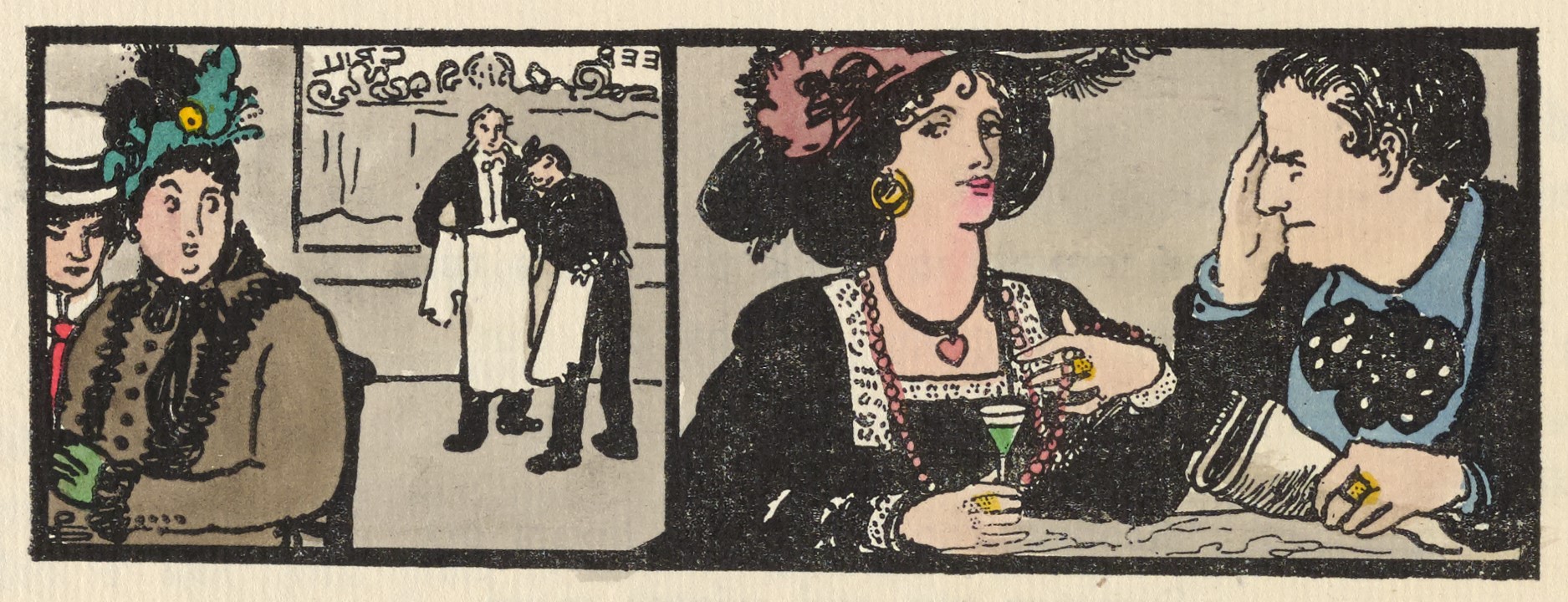

Green Sheaf No. 5 introduces four new names among its eight contributors. In addition to Moore, two other authors may be using pseudonyms: Mary Brown and Bernhard Smith. Each of these unknown writers supplies an engaging tale on a theatrical theme, rendered almost exclusively in dramatic dialogue. It is possible that Pamela Smith herself may be the writer behind the scenes in each case. It is also possible that the Bernhard Smith pseudonym was used by either William Arthur Hans Bernhard-Smith (?-1927), an author and surgeon, or his artistic wife, Alice Mary Bernhard-Smith (1874-1969), who had a wide circle of friends in London’s bohemian crowd of actors, artists, authors, and musicians and may have met the Green Sheaf’s editor-publisher through this shared network (“Mrs. A.M. Bernhard-Smith”). Significantly, Pamela Colman Smith’s headpiece illustration for Bernhard Smith’s “Juveniles” suggests that the story’s narrator, who observes a pair of actors in a café and comments on their conversation, is female (fig. 3). Depicting the scene like a divided stage set, with the principal speakers—an enticing actress and her leading man—in the foreground at right, the audience of two women diners at left, and two waiters hovering in the background, Smith plays up the performative theme of the piece. On tour in “the Provinces,” the actors cannot stop acting their parts, “treating us,” as the narrator comments, “to a free rehearsal” (B. Smith 11). As someone who had herself toured the provinces with Henry Irving’s and Ellen Terry’s Lyceum theatre troupe, “Pixie” Smith (as Terry dubbed her) understood the dramatic lives of actors, on and off the set.

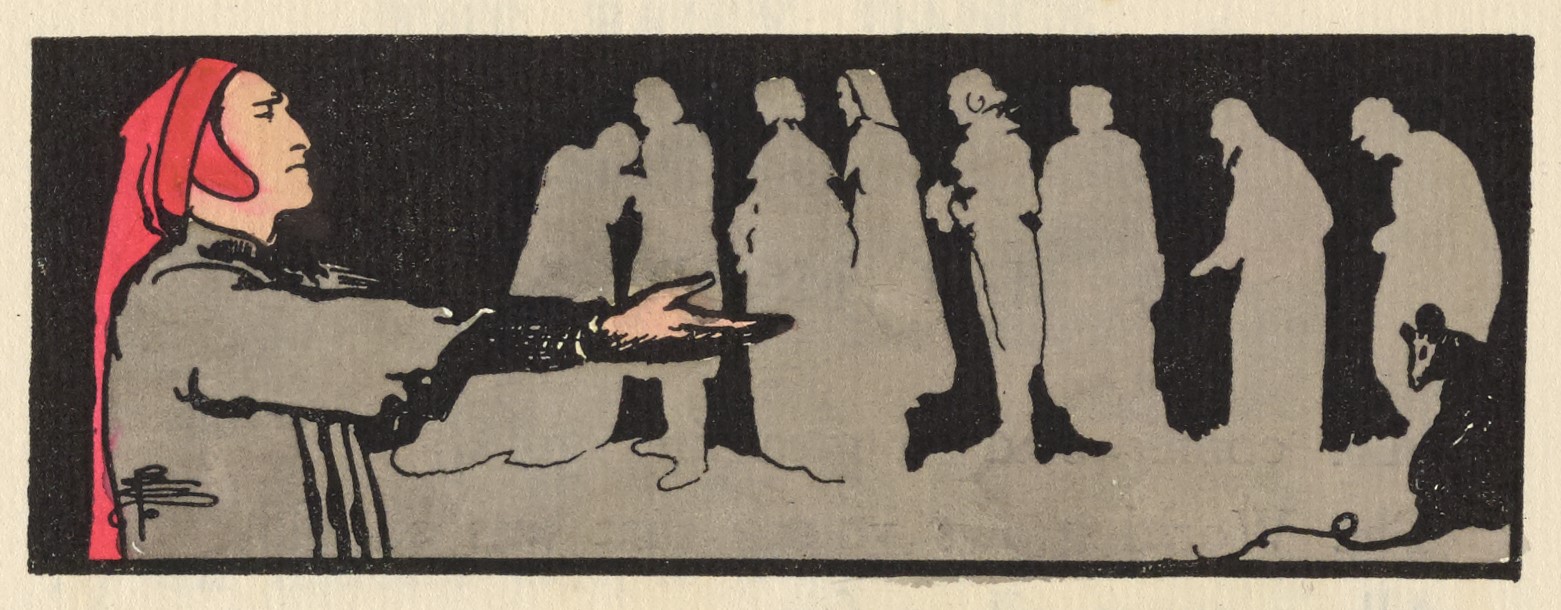

Mary Brown’s three-page story, “The Lament of a Lyceum Rat,” shows a similar familiarity with the world of actors, this time from the perspective of one ensconced in London’s West End. The rodent narrator shows an insider’s wry sympathy with the plight of actor-manager Henry Irving (1838-1905) on the loss of the Lyceum Theatre, which he had managed since 1878 with Smith’s friend Ellen Terry (1847-1928) as his leading lady. According to Katharine Cockin, Pixie Smith and Terry’s daughter Edith Craig (1869-1947), who worked together on costume and set designs, were dubbed “the Lyceum devils” (159). There is certainly an impish quality to Brown’s elegiac and fanciful tale, supposedly given to an unidentified human by the last rat to abandon the Lyceum Theatre after insolvency forced Irving to leave. The Reader article tags the reproduced illustrations for Brown’s story as “published in ‘The Green Sheaf’ (colored, of course) at the time Sir Henry Irving was giving his farewell performances at the old Lyceum Theatre, now being torn down” (“Writers and Readers,” 332). The Reader is off by more than a year: whereas the illustrated “Lament” was published in The Green Sheaf in September 1903, Irving’s final performance on the Lyceum stage occurred on 19 July 1902 (Tetens 279). In both of her illustrations for Brown’s story, Smith portrays Irving in his role as Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). Notably, the play about the medieval poet by Victorien Sardou (1831-1908) and Emile Moreau (1852-1922) became “the principal feature” of Irving’s post-Lyceum season in 1902-1903 (“Dramatic Gossip,” 136).

Smith’s headpiece illustration evokes the rat’s dream-vision of the empty stage, populated with the shades of Hamlet, Shylock, Mephistopheles, Faust, Robespierre, Richelieu, and other roles played by Irving over his long career (fig. 4). In the extreme left foreground, Irving stands in profile in the character of Dante. Forming a line at the back of the stage are the gray shades of his past roles with Terry, dramatically silhouetted against an inky black background. Also inky black, but less melodramatic and more whimsical, is the outsized rat in the right foreground, whose curly tail, coiling toward Irving, seems to imitate Smith’s idiosyncratic signature at left, where it embellishes the actor’s gray robes. Cockin names Smith’s signature “her devilish mark—a monogram that resembles a caduceus with snake-entwined staff formed by the etiolated letter P overlaid with a C and an S” (170)—and in this location on the image it does indeed seem to be calling deliberate attention to the artist-editor’s role as a Lyceum devil.

Irish author John Todhunter (1839-1916) makes his first appearance in The Green Sheaf’s fifth number; he would contribute to three more issues in the print run. A friend of Irish Revivalist W. B. Yeats (1865-1939), Todhunter was also, like Yeats and Smith, a member in the occult Order of the Golden Dawn. Smith positions his two-stanza “May Madrigal” in a double-page opening, facing “The Fairy Dance” by his compatriot, Alix Egerton (1870-1932). While Todhunter’s lyric celebrates spring woodlands and love, Egerton’s explores how “The girl who has danced on the Fairy Hill” on the “Eve of May” becomes separated from “The World” in a way that recalls French’s isolated “Dreamer” of the frontispiece. While it might seem strange to include two works about spring in an autumn issue, the poems maintain the magazine’s ongoing interest in Irish local-colour literature, while also supporting the number’s thematic concern with individuals set apart by life choices and circumstances.

The sixteen-page issue concludes, as usual, with two pages of advertising. Smith always uses these pages to make her professional networks visible and to support the work of her friends and herself. In addition to advertising her hand-coloured prints of Ellen Terry in various acting roles, Smith offers the services of her Green Sheaf School of Hand-Colouring for “small Editions of books, programmes, cards, etc., for private Theatricals and Dances.” The select publisher’s list offered by Elkin Mathews (1851-1921) is headed with “A Broad Sheet—for the Year 1902: With Pictures by Pamela Colman Smith and Jack B. Yeats.” Mathews’s list also advertises A Broad Sheet “for the year 1903 (now proceeding), which Jack Yeats (1871-1957) edited and illustrated on his own after Smith left to launch a little magazine of her own, The Green Sheaf (Advertisements, 15). The final page prominently features Smith’s hand-coloured advertisement for Edith Craig’s costume shop and promotes the exhibitions and art classes on offer at John Baillie’s (1868-1926) Art Gallery in Bayswater. The Advertisements conclude with a prospectus for The Green Sheaf’s upcoming number, hinting that No. 6 would make good on the editor’s promise that there would be “tales of pirates and the sea” in her magazine (Advertisements, 16; Smith, Front Cover).

©2022 Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, FRSC, Emerita Professor of English and Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Digital Humanities, Toronto Metropolitan University

Works Cited

- Advertisements. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, pp. 15-16. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-ads/

- Brown, Mary. “The Lament of the Lyceum Rat,” illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, pp. 8-10. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-brown-lyceum/

- Cockin, Katharine. “Bram Stoker, Ellen Terry, Pamela Colman Smith and the Art of Devilry.” Bram Stoker and The Gothic: Formations to Transformations, edited by Catherine Wynne, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 159-171.

- Dow, Arthur Wesley. Composition: A Series of Exercises in Art Structure for the Use of Students and Teachers. Doubleday, 1913.

- “Dramatic Gossip.” The Athenaeum, 26 July 1902, p. 136. British Periodicals, ProQuest.

- Egerton, Alix. “The Fairy Dance,” decorated by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 6. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-egerton-fairy/

- French, Cecil. “The Dreamer and the World.” The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 2. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-french-dreamer/

- —. Pictorial Initial for “Will o’ the Wisp,” by Leslie Moore. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 13. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://ornament.library.torontomu.ca/items/show/197

- —. “The Turning of the Tide,” The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 11. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-french-tide/

- Gregory, Lady Augusta, trans. “Cael and Credhe,” illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, pp. 3-5. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-gregory-cael/

- Moore, Leslie. Katherine Mansfield: The Memories of L.M. Taplinger Publishing, 1972.

- —. “Will o’ the Wisp,” pictorial initial by Cecil French. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, pp. 13-14. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. [url]

- “Mrs. A.M. Bernhard-Smith.” Obituary copied from St. Nicholas at Wade Parish Magazine, 1969? St Nicholas-at-Wade website, accessed 28 September 2021. http://www.stnicholasatwade.org.uk/molly.html,

- Murry, John Middleton and Ruth Elvish Mantz. The Life of Katherine Mansfield, Constable, 1933. New Zealand Electronic Text Collection, Katherine Mansfield Texts Collection, University of Wellington, Victoria.

- Smith, Bernhard. “‘Juveniles’,” illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 12. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-french-tide/

- Smith, Pamela Colman. Front Cover. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. [i]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-smith-front-cover/

- —. Illustration for “Cael and Credhe,” by Lady Augusta Gregory. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 5. The Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-smith-cael/

- —. Headpiece Illustration for “The Lament of the Lyceum Rat,” by Mary Brown. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 8 Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-smith-lyceum-illustration-p8/

- —. Illustration for “The Lament of the Lyceum Rat,” by Mary Brown. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 9. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-smith-lyceum-illustration-p9/

- —. Illustration for “Juveniles,” by Bernhard Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 12. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-smith-juveniles-headpiece/

- —. “Time,” The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 11. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-smith-time/

- Tetens, Kristan. “‘A Grand Informal Durbar’: Henry Irving and the Coronation of Edward VII.” Journal of Victorian Culture, vol. 8, no. 2, 2003, pp. 257-291. https://doi.org/10.3366/jvc.2003.8.2.257.

- Todhunter, John. “A May Madrigal,” The Green Sheaf, No. 5, 1903, p. 7. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV5-todhunter-madrigal/

- “Writers and Readers: Illustrated Notes of Authors, Books, and the Drama.” The Reader, vol. 2, no. 4, September 1903, pp. 330-332.

MLA citation:

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf No. 5, 1903.” Green Sheaf Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2023. https://1890s.ca/gsv5_introduction/.