XML PDF

Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf

No. 4, 1903

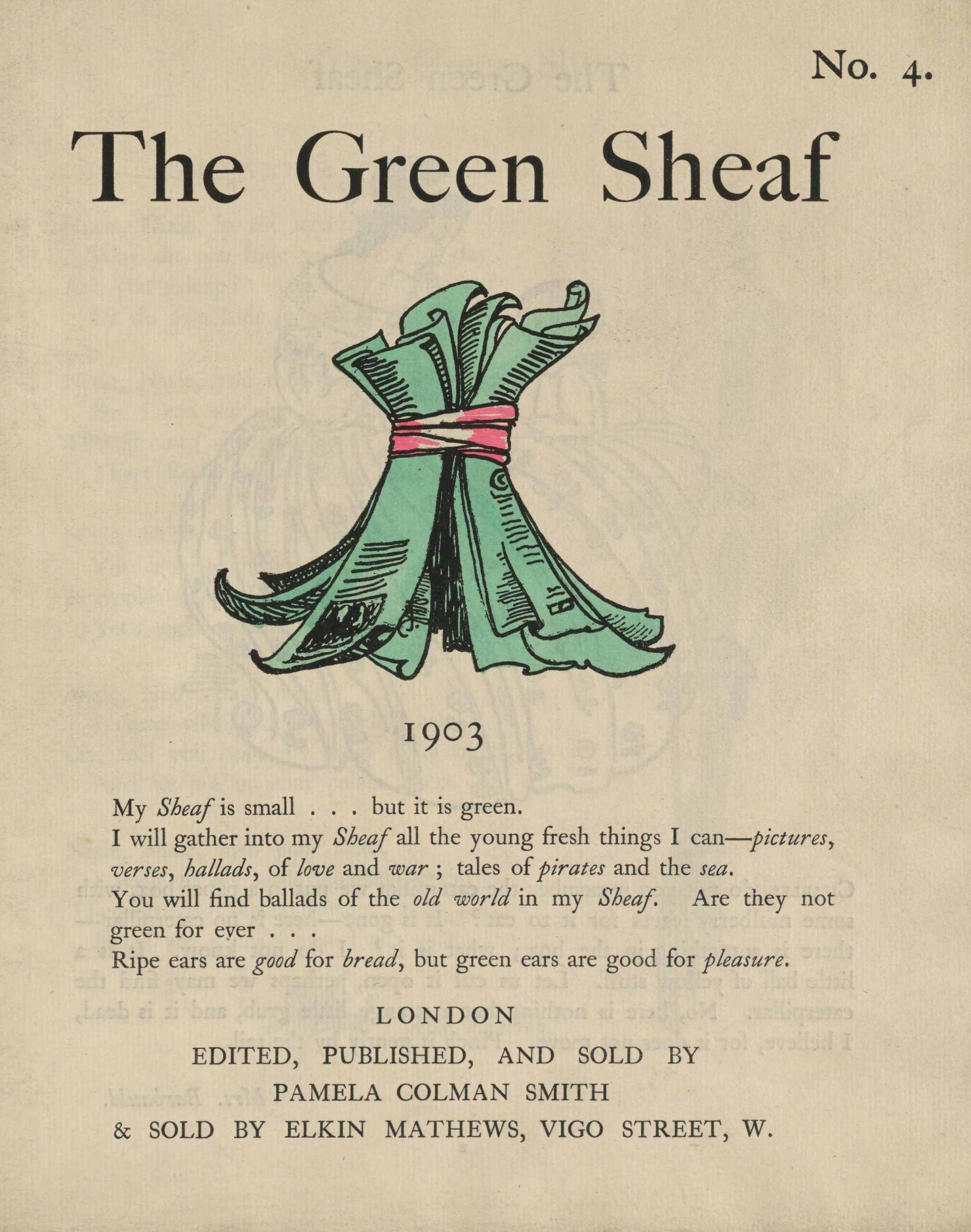

The Green Sheaf’s fourth monthly number offers readers a new look and fresh topics to explore. In contrast to the previous issue, which had been keyed to acts of interactive performance, the contents concentrate on acts of individual perception and experiences of separation and transformation. Editor and hand-colourist Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951) uses a subdued palette of dull tans, grays, yellows, and greens, offset by dusky roses and purples, to express the issue’s themes and enhance the colour harmonies across its sixteen pages (fig. 1). The fourth number also presents a new public face: its cover is the first to display the magazine’s manifesto and to give Smith prominent billing as editor, publisher, and seller of the magazine (Smith, Cover). Henceforth these elements would front every issue, together with the familiar iconography of stacked green sheaves tied up with red ribbon (fig. 2).

Contents include five poems and four prose pieces, an array of hand-coloured illustrations and decorations, two pages of advertisements, and an Illustrative Supplement. The supplement must surely have been an enticing souvenir for purchasers of Smith’s magazine, which was associated with the Irish Revival movement. Mounted on heavy art paper, the halftone reproduction of “The Lake at Coole,” a pastel drawing by William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), offers a visual memento of a celebrated locale from the hand of an esteemed national poet. The home of Yeats’s patron Lady Augusta Gregory (1852-1832), Coole Park was the site of the poet’s summer writing retreats. The pastel had special meaning for Yeats, who was pleased with his artistic effort and the associations it evoked (Patke 484). According to Katharine Cockin, these associations touched on the faerie realm: “the site depicted in Yeats’s drawing in The Green Sheaf is where the gamekeeper heard footsteps of deer from ancient times. The place reminded him of that knowledge available only through the effort of spiritual pursuit” (“Bram Stoker,” 167). In keeping with the issue’s themes of perception and transformation, the Illustrative Supplement evokes the intersection of past and present, material and mystical.

Like Yeats, Smith was drawn to esoteric knowledge rooted in the Irish landscape and the fairy faith. According to Lady Archibald Campbell’s article on “Faerie Ireland” in the Occult Review, Smith and Alix Egerton (1870-1932) had a vision of the Sidhe and heard their magic music on a visit to the Peacock Well around this time (266-267). Campbell recalls that W.B. Yeats and A.E., Ireland’s “great seers,” also visited this “gentle glen,” known to be “haunted by the Passing People” (262). For all these reasons, Yeats’s drawing of an Irish locale infused with mystic meaning likely carried deep personal significance for The Green Sheaf’s editor. The paratextual supplement was, however, to be Yeats’s final contribution to the magazine. Although he participated in the original planning of The Green Sheaf and contributed to its second, dream-themed number, Yeats’s involvement with the magazine ended with the fourth issue. Reasons are not hard to find. As discussed in the General Introduction, Smith and Yeats had different ideas for the little magazine from the start. The two came into further conflict when their individual engagement with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn took separate paths in 1903. More interested in a Judeo-Christian mysticism than in magic and the occult, Smith stayed with the Arthur Waite (1857-1942) contingent of the Order, rather than following Yeats in the schism (Kaplan et al, 352).

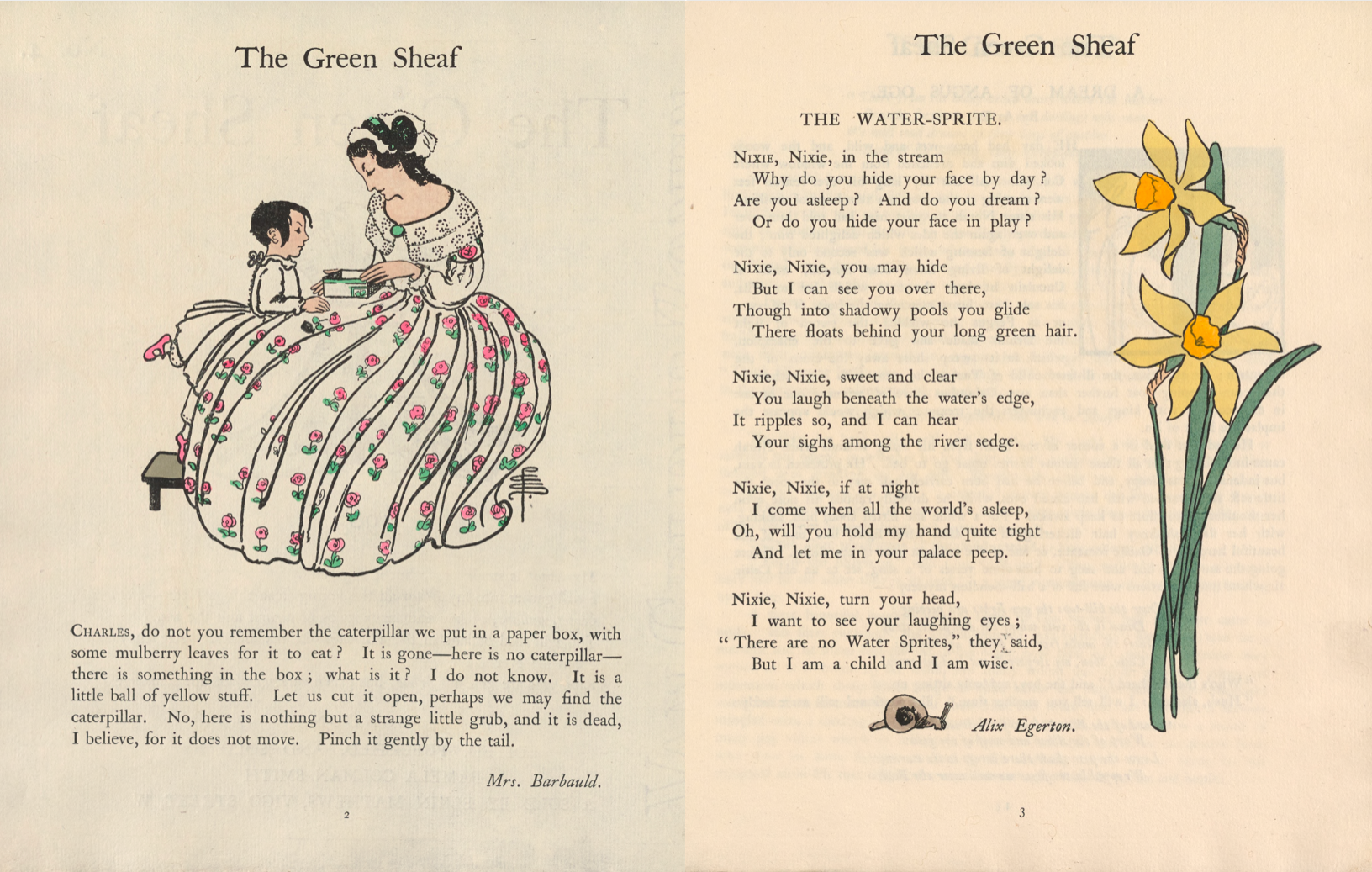

Smith opens the fourth number with an excerpt from one of her favourite authors, the late-eighteenth century educationalist Anna Laetitia Barbauld (1743-1825). Although unconnected with either Ireland or the fairy faith, the Barbauld piece aptly sets the issue’s theme with its perceptive exploration of transformation in the natural world. When she first arrived in London at the turn of the century, Smith had tried unsuccessfully to interest London publishers in an illustrated edition of Barbauld’s Lessons for Children (1778-79). Smith subsequently published illustrated excerpts of this work in both A Broad Sheet (1902), which she co-edited with Jack Yeats (1871-1957), and The Green Sheaf (1903-4).

In the untitled extract from Barbauld’s Lessons, the mother asks little Charles to notice the transformations undergone by the caterpillar they had previously put into a box lined with mulberry leaves. Smith’s illustration, coloured in pink, green, and tan, shows Charles on tiptoe, looking into the box his mother holds on her lap (fig. 3). The restricted palette and generous use of white bring the pair and their shared activity into quiet harmony. Smith was to include illustrated excerpts of Barbauld’s Lessons in Numbers 9 and 13 of The Green Sheaf as well. Indeed, work by this deceased English author actually appears more frequently than some of the living Irish revivalists who collectively dominate the magazine’s list of contributors. For example, there are more pieces by Barbauld than either Jack or William Butler Yeats, and her contributions appear almost as often as those of A.E. (George Russell). While it is accurate to identify The Green Sheaf as a little magazine associated with the Irish Revival, Smith’s eclectic selections suggest that her personal interest in folklore and her inclinations toward the mystical and symbolic superseded considerations of nationalist politics.

Excluding the supplement, the fourth number of The Green Sheaf features three Irish contributors: A.E. (1867–1935), Alix Egerton, and Cecil French (1879-1953). The Irish contributors are significantly outnumbered by English authors and artists, however. In addition to Smith herself, these include artists Lewis Grant (dates unknown) and W. T. Horton (1864-1819), actor Laurence Irving (1871-1914), poet/illustrator Dorothy Ward (1879-1969), and two pseudonymous contributors, “Lucilla” (whose work had first appeared in Green Sheaf No. 2) and “C.H.,” who translated a song from the popular La Princesse Lointaine (“The Far Princess”) by French dramatist Edmond Rostand (1868-1918). While the identity of “C.H.” is unknown, “Lucilla” was the pen name of Grace E. Tollemache (1869-1934), an activist in feminist and animal rights causes who published with Green Sheaf distributor Elkin Mathews.

The romantic belief that young children can perceive what adults cannot—particularly with respect to the supernatural—is explored in two of the issue’s works. In Alix Egerton’s poem “The Water Sprite” a child talks to nixies (water sprites in German mythology), while A.E.’s story “A Dream of Angus Oge takes as its premise “the frailty of the link binding childhood to earth in its dreams” (5). Framed by a contemporary setting in which young Norah tells the traditional tales of Cuculain to her brother Con at bedtime, the dream narrative relays how Con, together with a golden-hued Shepherd, flies over fairyland to a cave in the Land of the Immortals, where “the ruddy and eternal glow” of the sun reveals that earth is “but a smoky shadow” in comparison (6). Just before Con awakes, the Shepherd identifies himself as Angus the Young— the Celtic god of youth and beauty. A.E.’s version of this ancient tale participates in a wider revival of Celtic lore across countries and nationalities. In the Winter volume of the Edinburgh-based Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal, for instance, Fiona Macleod’s “The Snow Sleep of Angus Ogue” offers a variant tale about this ancient god of eternal Spring, Youth, and Hope, who in this version also symbolically represents the enduring Celtic spirit (Macleod 122-23). Pamela Colman Smith’s hand-coloured pictorial initial for A.E.’s story gestures toward the mythic realm in both its composition and its tinting (fig. 4). The square initial letter presents itself to the viewer as a window through which the seen and unseen can be glimpsed together. The central capital “T” dramatically separates the material world on the left, represented by the young Con sitting up in bed, and the eternal world on the right, represented by the saffron-robed spirit of Angus. Smith’s gold-tinted background brings the apparent dichotomies of earth and spirit into unified harmony, connected by the strong diagonal of the god’s arm descending across the spatial divide.

The changes in perception and experience wrought by separation in time and space is the theme taken up in the sequence of five poems Smith places between “A Dream of Angus Oge” and the issue’s final prose piece, “Prince Siddartha.” Cecil French’s “Friends” appears at the end of A.E.’s story of the Celtic god, positioned below a decorative frieze by Lewis Grant showing two nude youths sleeping under a bramble of roses while doves circle above them. French’s lyric expands on the theme of separation and transformation. The lyric speaker reassures his beloved that, despite their spatial and social separation, they will continue to be together in spirit.

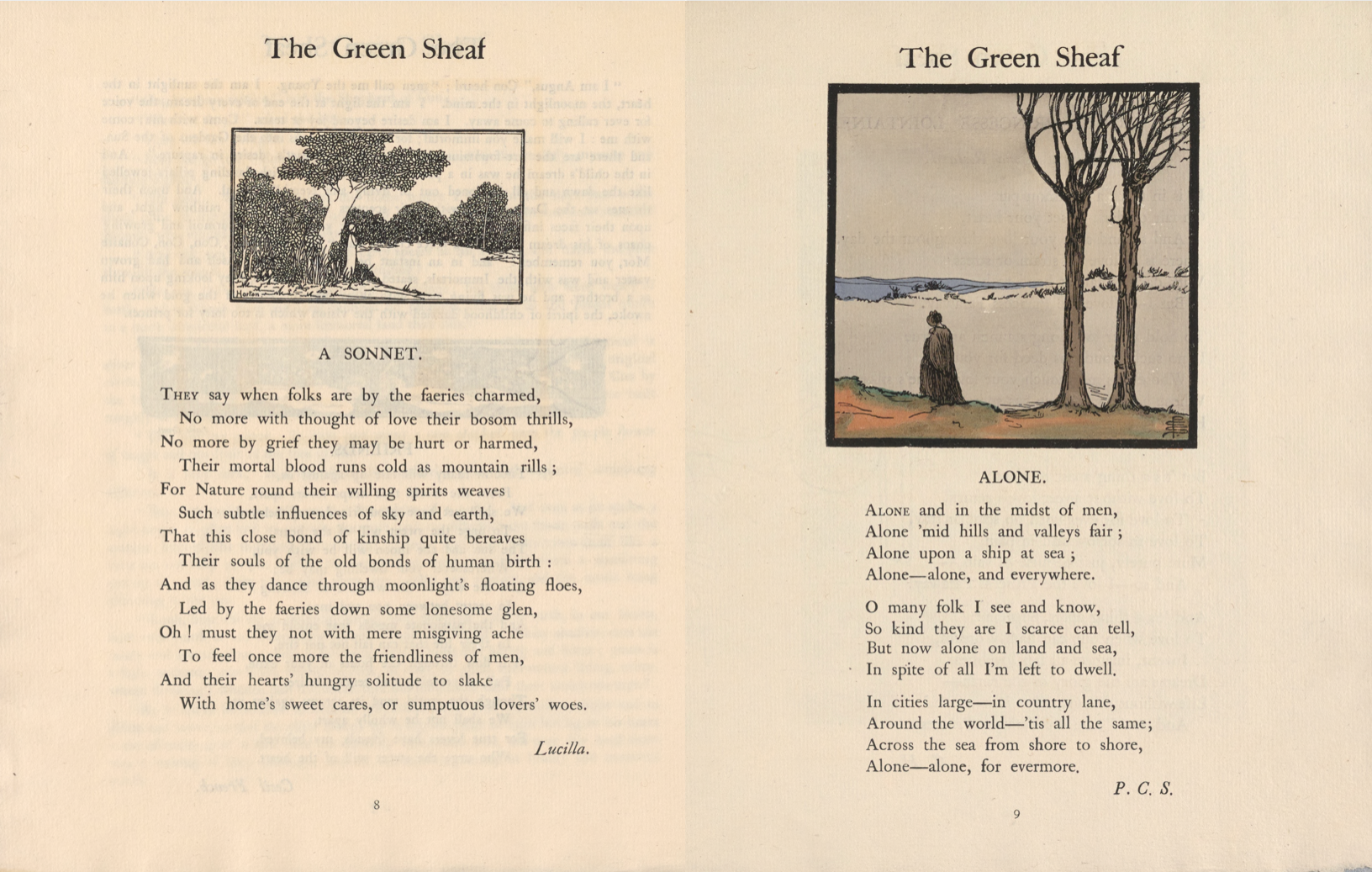

The following double-page opening features two facing poems, each exploring experiences of separation in women’s voices. On the verso, Lucilla’s “A Sonnet” describes the separation from earthly kin that results “when folks are by the faeries charmed” (10). Pamela Colman Smith’s “Alone” on the recto engages with the experience of solitude in a social world. Katharine Cockin argues that the three-stanza lyric exemplifies “the introspective and individual dream/vision” that inspired much of her work (“Pamela Colman Smith,” 77). Elizabeth O’Connor reads the poem biographically, as an expression of the poet’s increasing sense of isolation (169). However, Smith’s editorial choice to place her lyric across from Lucilla’s sonnet suggests another possible reading. In the context of The Green Sheaf page opening, Lucilla’s poem about mortals encountering faeries invites readers to interpret Smith’s lyric as the expression of one thus charmed, now forced to live “Alone—alone, for evermore” (Smith 11). Notably, Smith reinforces the association of the two poems through design, placing a framed headpiece illustration above each set of verses (fig. 5). W. T. Horton’s black-and-white headpiece for Lucilla’s “Sonnet” shows a lonely figure standing under a large tree in a verdant setting. His composition is echoed on the recto in Smith’s hand-coloured illustration of a similar but sadder scene, in which the branches are barren and the isolated figure more downcast (fig. 5). Overleaf, the translation of Edmond Rostand’s “Song from ‘Princess Lointaine’” by C.H. continues the poetic theme, reaching back into the medieval troubadour tradition to do so. Here, the singer laments his separation from “Princess Faraway,” knowing he and his beloved can only be together in dreams (C.H., 10). The last lyric in the issue’s sequence of five poems, Dorothy Ward’s illuminated “Evening,” celebrates the separation of day and night, earth and sky. Here, the liminal offers the opportunity to escape quotidian cares in the land of dreams, where transformation always seems possible.

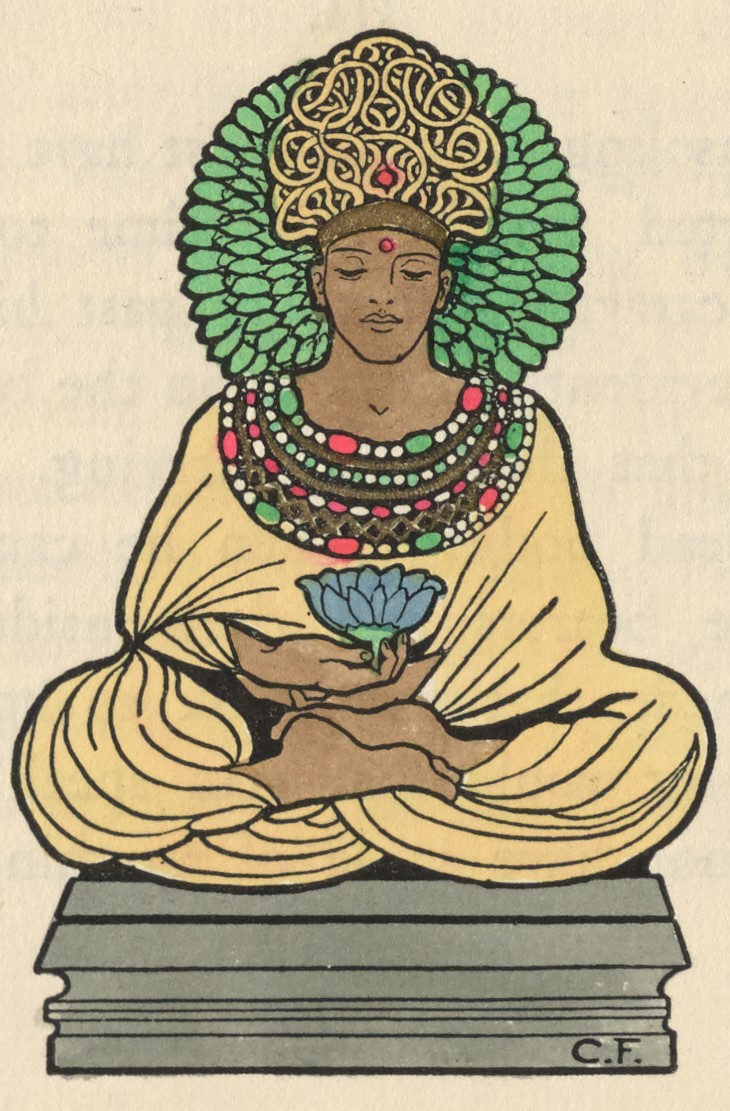

Smith concludes the contents of The Green Sheaf’s fourth number with an eastern tale of enlarged perception and spiritual transformation: Laurence Irving’s four-part retelling of “Prince Siddartha,” the ancient story describing the road to enlightenment. Smith’s inclusion of an Indian religious legend in a little magazine associated with the Irish Revival attests to her editorial interest in things she asserts are “green for ever” (Smith, Cover), irrespective of their connection to Celtic lore. For Smith, it was the enduring truths of folklore—whether Oriental legend, Jamaican trickster tale, or Celtic fairy faith —that opened a portal into the mystic and visionary, revealing an eternal world of spiritual meaning beyond the mutable and mortal. Irving’s version of the story of the privileged prince’s transformation into perceptive Buddha thus provides a fitting end to a Green Sheaf issue that explores the inadequacy of clinging to impermanent states and things.

Smith frames “Prince Siddartha” with two coloured illustrations. She heads the tale with her own illustration of the pivotal scene in which the prince meets the beggar and punctuates it with an illustration by Cecil French showing the Buddha seated in the lotus position, meditating with closed eyes (fig. 6). As she did for the Celtic god Angus Oge (see fig. 3), Smith tints the Buddha’s robes with saffron, the colour symbolic of spiritual enlightenment (Roa 2; Kooistra and Grant, np).

The last double-page opening is a study in contrasts, with the spiritualized Buddha on the verso signalling detachment from earthly things, and Pamela Colman Smith’s page of self-advertisements on the recto assertively trying to sell things to make a living. This is the first issue in which Smith devotes an entire page to marketing her own wares, and the first, too, to advertise her Green Sheaf School of Hand-Colouring, whose services were available for “small Editions of Books, Programmes, Cards, etc.,” as well as for “advertising purposes” (Advertisements, 15). Smith also offers Green Sheaf readers a series of hand-coloured prints of her friend, the actress Ellen Terry (1847-1928), in various theatrical roles; a portfolio of three hand-coloured prints entitled The Basket Maker, the Wind, and the Farm House; and two of her folktale collections, first published by Doubleday and McClure in 1899, and now appearing on Elkin Mathews’ list: The Golden Vanity and the Green Bed and Widdicombe Fair. In addition to the usual advertisements for Edith Craig’s (1869-1947) costume shop and John Baillie’s (1868-1926) art gallery, the final page provides a forecast of The Green Sheaf’s next number. The difference between what is forecast here and the contributors who actually appear in No. 5 suggests the challenges Smith faced in bringing out her little magazine of literature and hand-coloured art from her studio in Chelsea every month.

©2022 Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, FRSC, Emerita Professor of English and Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Digital Humanities, Toronto Metropolitan University

Works Cited

- Advertisements. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, pp. 15-16. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-ads/

- A.E. [George Russell]. “A Dream of Angus Oge,” pictorial initial by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, pp. 4-7. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-ae-angus/

- Barbauld, Anna. Untitled. [“Charles, do you not remember”], illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, vol. 4, 1903, p. 2. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-barbauld-charles/

- Campbell, Lady Archibald. “Faerie Ireland.” Occult Review, November 1907, pp. 259-74.

- C.H., trans. “Song from ‘Princesse Lointaine,” by Edmond Rostand. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. 10. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022 https://1890s.ca/GSV4-rostand-princess/

- Cockin, Katharine. “Bram Stoker, Ellen Terry, Pamela Colman Smith and the Art of Devilry.” Bram Stoker and the Gothic: Formations to Transformations, edited by Catherine Wynne, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 159-171.

- —. “Pamela Colman Smith, Anansi and the Child: From The Green Sheaf (1903) to The Anti-Suffrage Alphabet (1912). Literary and Cultural Alternatives to Modernism, edited by Kostas Boyiopoulos, Anthony Patterson and Mark Sandy. Routledge, 2019, pp. 71-84.

- Egerton, Alix. “The Water-Sprite,” decorated by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. 3. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-egerton-sprite/

- French, Cecil. “Friends,” illustrated by Lewis Grant. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. 7. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-french-friends/

- —. Illustration for “Prince Siddartha,” by Laurence Irving. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. 14. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-french-buddha/

- Grant, Lewis. Illustration for “Friends,” by Cecil French. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. 7. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-grant-frieze/

- Horton, W. T. Illustration for “The Sonnet,” by Lucilla. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. 8. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-horton-sonnet/

- Irving, Laurence. “Prince Siddartha,” illustrated by Cecil French and Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, pp. 12-14. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-irving-siddartha/

- Kaplan, Stuart R, with Mary K. Greer, Elizabeth Foley O’Connor, and Melinda Boyd Parsons. Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story. U.S. Games Systems, 2018.

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “‘A Paper of Her Own’: Pamela Colman Smith’s The Green Sheaf (1903-1904).” Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/green-sheaf-general-introduction/.

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen, and Mary Grant. “Working against ‘that thunderous clamour of the steam press’: Pamela Colman Smith and the Art of Hand-Coloured Illustration.” Nineteenth-century Women Illustrators and Cartoonists, edited by Joanna Devereaux, Manchester University Press. Forthcoming 2023.

- Lucilla. “A Sonnet,” illustrated by W.T. Horton. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. 10. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-lucilla-sonnet/

- Macleod, Fiona. “The Snow Sleep of Angus Ogue.” The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal, vol. 4, Winter 1896-7, pp. 118-123. Evergreen Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/egv4_macleod_snow/

- Patke, Rajeev S. “Yeats Among Painters.” Third Text, vol. 22, no. 4, July 2008, pp. 483-494.

- O’Connor, Elizabeth. “Pamela Colman Smith’s Performative Primitivism.” Caribbean Irish Connections: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Alison Donnell, Maria McGarrity, and Evelyn O’Callaghan, University of the West Indies Press, 2015, pp. 157-173.

- Rao, Bina. “The Sacred Yellow.” Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, October 6-9, 2010, pp. 1-4.

- Smith, Pamela Colman. “Alone,” illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No 4, 1903, p. 9. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-smith-alone/

- —. Cover for The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. [i]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-smith-front-cover/

- —. Illustrated Advertisement for Edith Craig & Co. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. [i]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-craig-ad/

- —. Illustration for Untitled [“Charles, do you not remember…”], by Anna Barbauld. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. 2. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-smith-charles/

- —. Pictorial Initial for “The Dream of Angus Oge,” by A.E. The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p. 4. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://ornament.library.torontomu.ca/items/show/192

- Ward, Dorothy. “Evening.” The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903, p 11. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-ward-evening/

- Yeats, W.B. “The Lake at Coole.” Illustrative Supplement (np) to The Green Sheaf, No. 4, 1903. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022. https://1890s.ca/GSV4-supplement/

MLA citation: Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf No. 4, 1903.” Green Sheaf Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by

Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities,

2023. https://1890s.ca/gsv4_introduction/.