XML PDF

Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf

No. 11, 1904

The colour palette Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951) uses to tint the images in The Green Sheaf’s eleventh number express its elegiac and memorial themes in somber shades of deep purple, dark green, dull turquoise, and neutral hues (fig. 1). With only two of the three illustrations hand-coloured, and a total of five poems printed across its eight pages, black-and-white lines predominate in this issue. Frequent contributors Dorothy Ward (1879-1969) and Alix Egerton (1870-1932) are joined by newcomers Mary Grace Walker (1849-1920) and Yone Noguchi (1875-1947). Smith selects an anonymous medieval lyric to round out the contents.

Smith opens the number with “The Changed World,” a lyric enclosed within an illustrative pen-and-ink frame by Dorothy Ward on the verso, and “The Violet,” by Japanese poet Yone Noguchi on the recto. Although both poems draw on natural imagery and a night setting, they differ dramatically in poetic style and form. The child speaker in Ward’s “The Changed World” ponders the “many gay colours” evident in “the daytime . . .world” in comparison to the gray and black shades visible at night (Ward 2). In contrast to Ward’s rhyming quatrains, Noguchi’s “The Violet” is a mood poem written in modern free verse. The lyric speaker, a flaneur catching a glimpse of a “girl’s shape” in crowded city streets at night, remembers his lost love, O Yen, and contrasts her violet-like soul with his own: “smitten by noise and storm, / [It] is like a dead leaf on the stream to the Unseen” (Noguchi 3). Smith’s inclusion of Noguchi in The Green Sheaf is in keeping with the magazine’s transnational reach, if not its local-colour interests. It may, however, have been Irish Revivalist William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) who brought editor and poet together; Yeats met Noguchi in New York in the fall of 1903 (Marx 339). It is also possible that Smith met Noguchi through artist Yoshio Markino (1869-1956) and author Arthur Ransome (1884-1967), who lived nearby in Chelsea and attended her Bohemian “at homes” (Marx 288; Ransome 51-56). Noguchi also had ties with other members of London’s little magazine community, including Richard Le Gallienne, Laurence Housman, Joseph Pennell, and Arthur Symons (Marx 22). The first Japanese poet to publish in English, Noguchi and his work were admired on both sides of the Atlantic in the first half of the twentieth century; recent scholars, however, have questioned his ambivalent and complicated record of production and reception (Marx 31). In any case, his poetry clearly appealed to Smith: she was to publish two more lyrics by Noguchi in The Green Sheaf’s next monthly number.

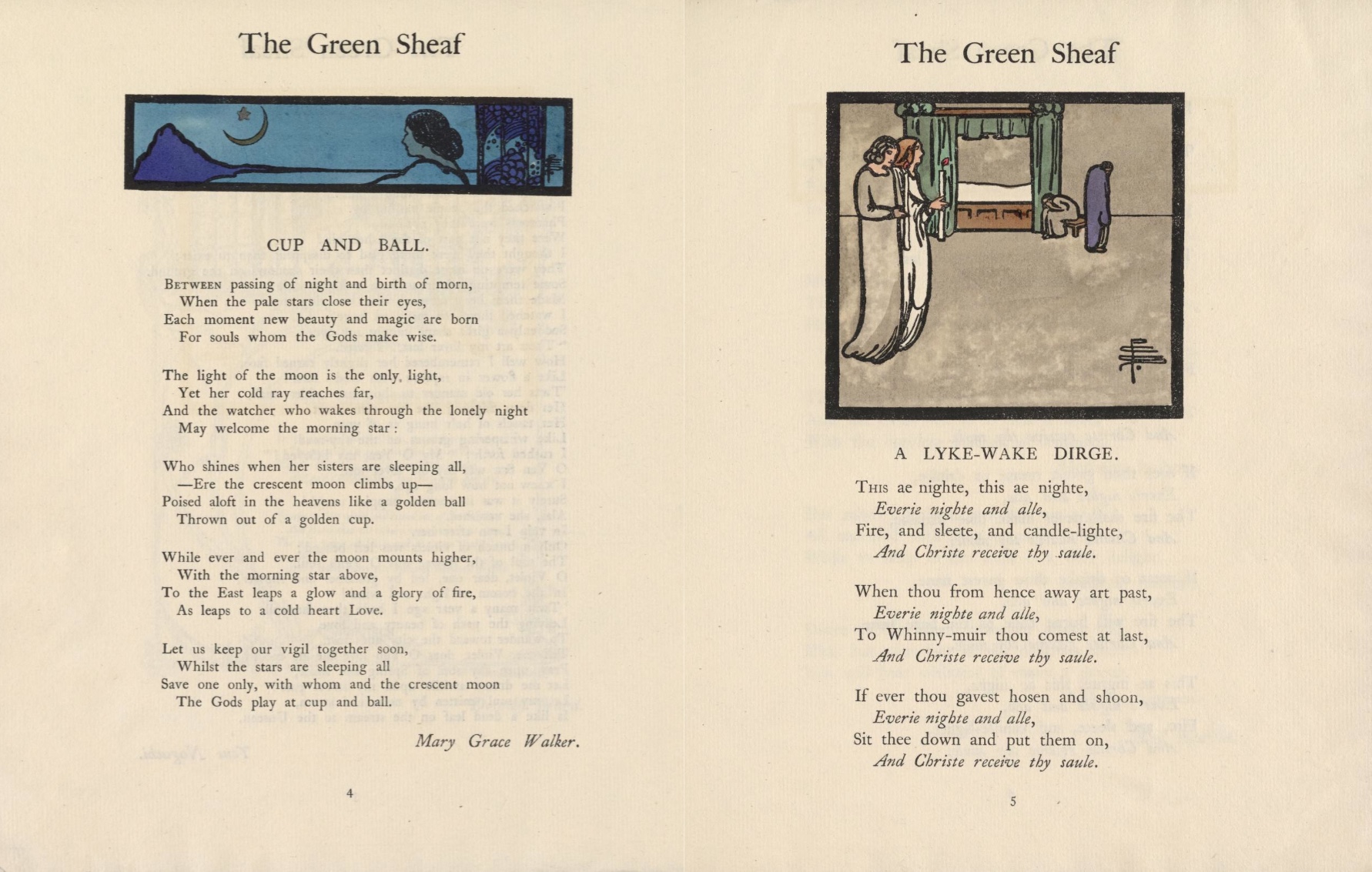

After the stark black-and-white presentation of the first double-page spread, the magazine’s second opening is illuminated by a pair of Smith’s hand-coloured illustrations (fig. 2). Smith positions a horizontal headpiece above Mary Grace Walker’s “Cup and Ball” on the verso and places a half-page illustration for the traditional English folk song “A Lyke-Wake Dirge” on the recto. In Smith’s illustration for “Cup and Ball,” a woman stands in three-quarter view with her back to the viewer, gazing out at a sickle moon with a single star poised above its tilted horns. In keeping with the verses, this view of the night sky suggests the stellar orb may have been tossed by the lunar projectile. Walker’s lyric reimagines the titular child’s toy as if it were made of celestial bodies for the gods to play with in the liminal moment between night and dawn, when “new beauty and magic are born / For souls whom the Gods make wise” (Walker 4). The dark-haired woman keeping vigil at the window in Smith’s design may represent the poet herself. Mary Grace’s ill health often kept her in the country, rather than in London at the family’s Hammersmith home (Loxley 3). The Guest Book Smith kept for her “at homes” indicates that Mary Grace did not join her daughter Dorothy (1878-1963) and husband Emery Walker (1851-1933) in their visits to the Green Sheaf editor’s Chelsea studio (“Visitors Book,” 151). As seen in both her Green Sheaf magazine and the titles later produced by her Green Sheaf Press, Smith shared Emery Walker’s interest in ornament and letterpress. The famous typographer’s 1888 lecture for the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society inspired the fin-de-siècle fine printing revival and launched the little magazine movement that began with The Dial in 1889 and continued into the twentieth century with The Green Sheaf and The Venture (See General Introduction to The Dial: An Occasional Publication). While the family connection may have prompted Smith’s inclusion of Mary Grace Walker’s poem, the poet’s birth in Ireland—she hailed from county Sligo—also ensured Alix Egerton would not be the only Irish contributor in The Green Sheaf’s eleventh number.

Smith supplies a hand-coloured illustration and devotes two whole pages to the anonymous medieval lyric, “A Lyke-Wake Dirge” (Anon). Written in Yorkshire dialect, the poem expresses the tradition of mourners keeping watch (a “wake”) over a corpse (“lyke”) on the night before burial, when the soul was thought to travel to purgatory, where its deeds in life for good or for ill would be judged. Smith edges her illustration in a heavy black border reminiscent of the kind used in Victorian mourning stationery to indicate recent loss (fig. 2). The illustration itself is suggestive of a theatrical stage set. Against the back wall, the corpse is laid out in a curtained bed, with a figure on a low stool bent over in grief at its foot; a purple-robed figure departs the scene at right. In the left foreground, two androgynous figures in long robes enter the room, carrying lit candles. Apart from the green, purple, and white of variously coloured textiles, the entire image is washed in a dull taupe, expressive of the lyric’s sombre mood. Smith seems to have had a very personal connection to the poem and her illustration of it. In January 1907, when she became the first non-photographic artist to show her work at Alfred Stieglitz’s photo-secession gallery in New York, she gave Stieglitz (1864-1946) the original (uncoloured) drawing, with the hand-written message: “To one who appreciates what this means, with good wishes from Pamela Colman Smith” (Kaplan 231; Smith, “A Dirge”).

After the medieval poem on life and death, Smith closes the issue with a lyric by frequent contributor Alix Egerton (1870-1932). Using the Irish dialect word “Husheen” as the burden of a lullaby, Egerton imagines Memory in the form of a comforting mother: “to sleep in her arms is a dear delight.” While admitting the inevitable losses that come with the mortal condition—“The roses are born and the roses die”—the lyric speaker asserts that “They live again as do you and I, / In the heart and the dreams of Memory.” By personifying Memory as a woman in a blue robe spangled with stars, Egerton evokes a pagan goddess reminiscent of the Virgin Mary, “wise as a God is wise / With the limitless wisdom of centuries” (Egerton 7). Her poem provides a fitting end to an issue that explores the themes of death and loss and the mitigating powers of memory.

As usual, Smith advertises the work of friends and associates on the back cover of the magazine and offers subscribers the opportunity to purchase her hand-coloured prints of actress Ellen Terry (1847-1928) in various theatrical roles (Advertisements). In addition to printing The Green Sheaf manifesto and supplying subscription information on the front cover, Smith uses this public-facing space to advertise the upcoming issue. Green Sheaf Number 12, she promises, would include pictures by Eric Maclagan (1879-1951) as well as herself, and poems by returning contributors Alix Egerton, Cecil French (1879-1953), Yone Noguchi, and John Todhunter (1839-1916).

©2022 Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, FRSC, Emerita Professor of English and Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Digital Humanities, Toronto Metropolitan University

Works Cited

- Advertisements. The Green Sheaf, No. 11, 1904,

p. 8. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by

Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0,

Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022.

https://1890s.ca/GSV11-ads/

- Anon. “A Lyke-Wake Dirge,” illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith. The Green Sheaf, No. 11, 1904, pp. 5-6. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine

Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto

Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022.

https://1890s.ca/GSV11-lyke-wake/

- Egerton, Alix. “Memory.” The Green Sheaf, No.

11, 1904, p. 7. Green Sheaf Digital Edition,

edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties

2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital

Humanities, 2022.

https://1890s.ca/GSV11-egerton-memory/

- Kaplan, Stuart R, with Mary K. Greer, Elizabeth Foley O’Connor, and Melinda Boyd Parsons. Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story. U.S. Games Systems, 2018.

- Loxley, Simon. Emery Walker: Arts, Crafts and a World in Motion. Oak Knoll Press, 2019.

- Marx, Edward. Yone Noguchi: The Stream of Fate. Volume 1: The Western Sea. Botchan Books, 2019.

- Noguchi, Yone. “The Violet.” The Green Sheaf,

No. 11, 1904, p. 3. Green Sheaf Digital Edition,

edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties

2.0, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital

Humanities, 2022.

https://1890s.ca/GSV11-noguchi-violet/

- Ransome, Arthur. Bohemia in London. Stephen Swift, 1912; Forgotten Books, 2015.

- Smith, Pamela Colman. “A Dirge.” Ink and pencil on paper, 1907. Alfred

Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keefe Archive, Series VI: Works by Alfred Stieglitz

Contemporaries, Beinecke Library, Yale University.

https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/archival_objects/752993

- —. Front Cover for The Green Sheaf, No. 11,

1904, p. [i]. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited

by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0,

Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022.

https://1890s.ca/GSV11-smith-front-cover/

- —. Illustration for “Cup and Ball,” by Mary Grace Walker. The Green Sheaf, No. 11, 1904, p. 4. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine

Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto

Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022.

https://1890s.ca/GSV11-smith-cup/

- —. Illustration for “A Lyke-Wake Dirge,” by Anon. The Green Sheaf, No. 11, 1904, p. 5. Green

Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto Metropolitan

University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022.

https://1890s.ca/GSV11-smith-lyke-wake/

- “Visitors Book 1901-1905.” Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story, by Stuart R. Kaplan, with Mary K. Greer, Elizabeth Foley O’Connor, and Melinda Boyd Parsons, U.S. Games Systems, 2018, pp. 149-159.

- Walker, Mary Grace. “Cup and Ball,” illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith.

The Green Sheaf, No. 11, 1904, p. 4. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine

Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto

Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022.

https://1890s.ca/GSV11-walker-cup/

- Ward, Dorothy, “The Changed World,” illustrated by Dorothy Ward. The Green Sheaf, No. 11, 1904, p. 2. Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine

Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Toronto

Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022.

https://1890s.ca/GSV11-ward-changed/

MLA citation:

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “Critical Introduction to The Green Sheaf No. 11, 1904.” Green Sheaf Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Toronto Metropolitan University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2023. https://1890s.ca/gsv11_introduction/.