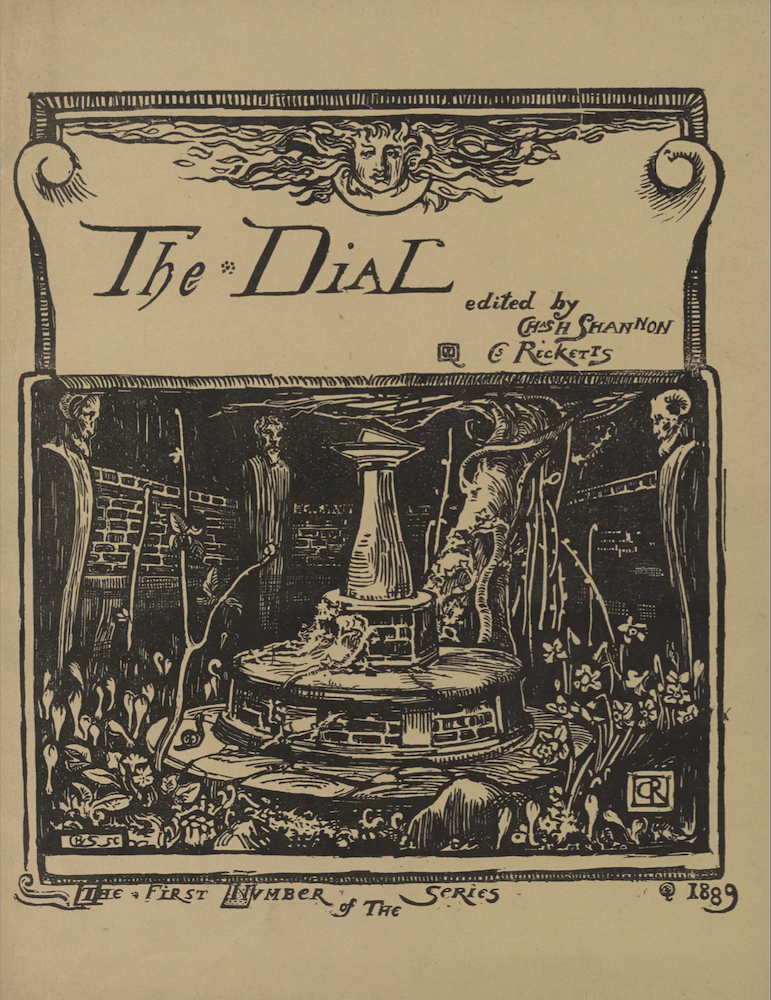

The Database of Ornament

THE sound rolls through the reddening

air, the muffled thum! the dumb! of a

monotonous

drum. Lamps flash ruddily

on gaudy pictures of the promised piece,

The Giant and Maiden. Again ’tis the

chart of the human frame flaming by

lamp-

light, with bright red veins, and liver a

beautiful yellow.

Shouting clowns hoarsely

proclaim the virtues and cures of an elixir,

a magic goblet; or lift the curtain to show

the careworn princess in

her tinsel and

spangles. And drums are rolled.

Come in! Come in!

Tis a trick; a dear old-world trick;

and in my quality of clown, I pray you,

let

me rattle my bells, show my happy cup, or

make each weary puppet

walk before the

crowd, shout, declare the oldness of my

piece; for

it is a play, and not a medicine after all, my Cup

of Happiness; not an

elixir, a cure for the liver; it is a

farce, an old farce; I vouch to its

age, for it was begun by

Madam Thalia, when the world was still young,

still a

delightful green, the beautiful green of a newly-painted

cupboard; but the play lasted too long, and has changed

considerably

since; however, do not hesitate, I vow the

play is old, old as Comedy

herself.

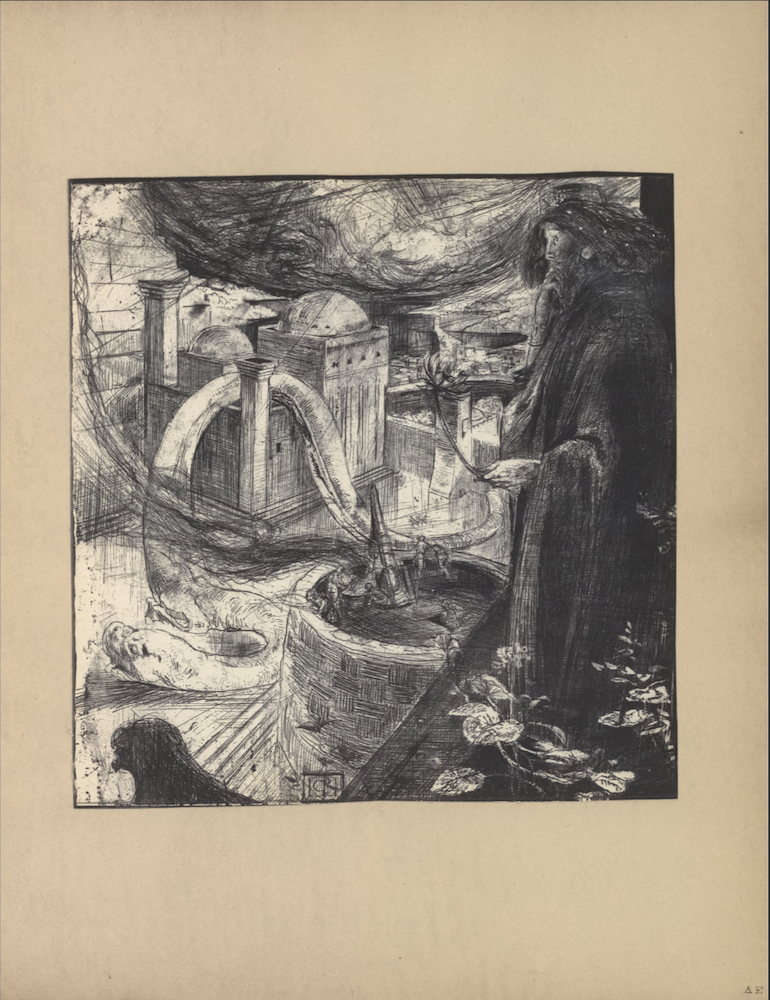

In a bright garden, near a rail, stands a strange statue,

but bitten to

death is La Comédie Humaine, and writhes

behind her stone-white mask.

27

The muse laughed on; so did the mask, grimly, growing heavy,

too heavy. She

danced with mad rapture, laughing shrilly, whilst

her nervous hands,

convulsed, clutched its grinning cheeks; but the mask

of stone laughed the

more at this, growing heavy, heavier still. Then

her agonized hands could

hold it no longer, the mask fell to the ground

and broke its nose.

The muse? she vanished in a frenzied hickup, for all the world like

the

snapping string of a violin.

Since this the white mask has been shown, with its sunken eyes, its

broken

nose, and its hollow awful eternal laugh, with castagnettes rattled

to an

ominous tune, with exaggerated tibias.

Schumann, like many, once saw this mask, this fatal mask, and has

sung of

it, a sob that is sobbed with clenched hands, accompanied by the

throbs of

a beating heart—Warum.

But this song is older than father Schumann’s song; the swelling

waves chant

the older melody, a Warum more minor, but laugh ironically

as they sweep

from the beach, trimmed with rippling bubbles, inviting to

their

liquidness, to the secret of their song, Warum?

How the water splashes and spreads, in grinning circles, if you fling

it a

stone. Is it a laugh? No,—a sob; for though rimmed with golden

sands it is

not a cup of happiness after all; frankly, the water is sad.

You see it can think back for a considerable time, and since the

breaking

of the mask, so many things have changed.

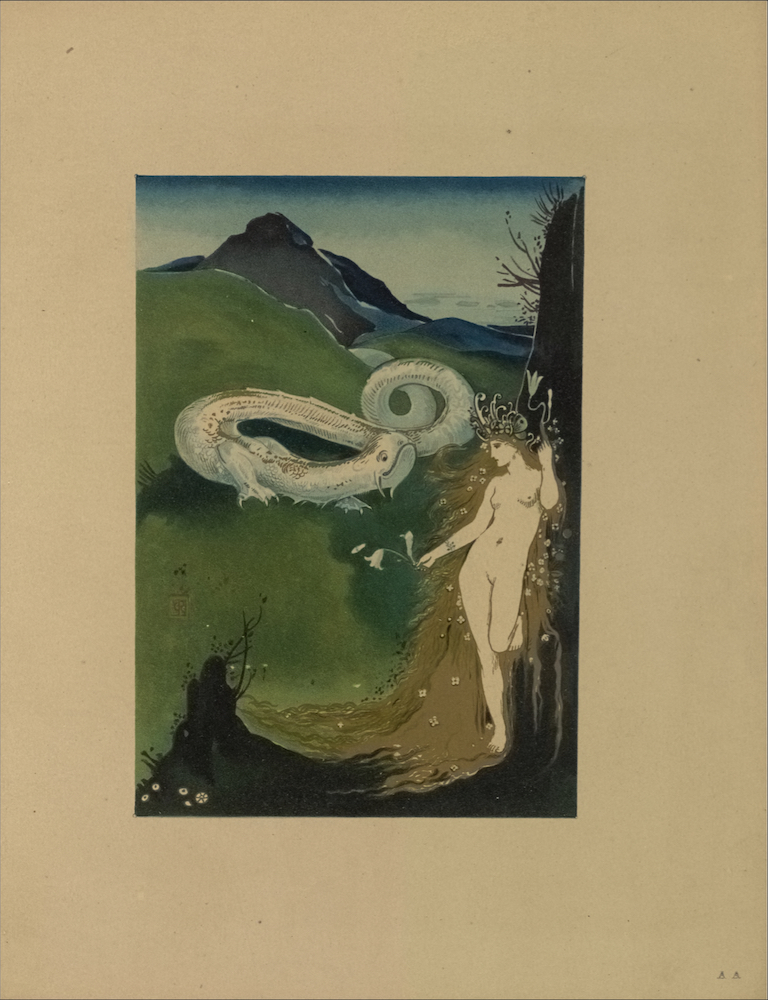

Once the sweet and gracious lady Venus rose from its depths, through

trails

of these bright chiming bubbles, on dancing foam. The worlds

of Gods and

men went mad ; the stars danced, till they fell like drunken

bees—hark!

the trees still groan, and the rivers moan!

Oh beautiful Lady Aphrodite Anadyomene! mercifully wring the

glittering

drops from your flaming mane into my cup, my Cup of

Happiness; and for the

sake of your beauty, I beseech you do not be

dumb, and in plaster, with

your eyes fixed afar on desolate Cnydos.

Ah, if my fancy, with exquisite tints, could quicken your limbs into

supple

life! perhaps—who knows?—you might tell me you are not Venus

after all,

but Eve, a Jewess; and not wring balm from your splendid

tresses.

Friends! you will see all I say is old, an old tune, with orthodox

Princess

and Prince; even an occasional, and quite accidental, virtue in

the story

is drawn as an initial. It was on a certain night when that

virtue lost

her head—but this is not quite true, as the play will show, for

all

virtues are Byzantine, and cannot bend their limbs.

As clown, I have shouted my talents, vaunted my magic goblet;

and if my

young fingers pull too nervously and obviously at my puppet

strings, know

I am only a pleasant amateur, and not a poor devil ; let

my laughingly

rattle my fool’s bells, my symbolical bells, shaped like

happy cups

reversed ; for all plays want bells, or the Warum song would

continue

monotonously throughout, till the veiled god of comedy, like

28

that mythical old man at the theatre door, puts out the lights one by one,

and shrouds most things with dusty covers; for he is deaf to unlimited

Warum songs, deaf even to the song of the crumbling and changing

atoms,—so

away with narrowing symbolism! laugh! and rattle the bells,

not hung on a

hyacinth sash as a prelude to a mystery—there is no-

mystery—I have pulled

up the curtain.

BY WAY OF PROLOGUE.

The name of my prince is formed of the names of all the Cardinal

Virtues,

composed into an euphonic whole. The greatest care, the most

loving pains,

had been lavished on his education; his bon mots were

printed on pink

paper by public subscription, trimmed with lace designed

by the best

artists only—yet he was not happy! though the welfare of

his kingdom could

only be gauged by the literary degradation of his

foreign neighbours, and

public opinion had placed his portrait in the

National Gallery as an old

master—no, he was not happy.

He tossed, in his troubled sleep, on his orthodox and princely

cushions, on

a golden and orthodox couch; he sighed in his painted

chamber, the walls

politely re-echoing his sighs, for they were painted

with virtues each

overcoming a dragon, each holding a hall-marked Cup-

of Happiness in

tapering hands, each daintily curving the little finger in

so doing.

The Cup of Happiness! The Cup of Happiness! groaned the prince

in his

attempts to recall gems of modern poetry; he suffered from

insomnia, as

should all well-bred and crowned heads, on cushions and

couches of gold.

His princely eyes were dizzied with following the allegorical twist of

the

enamelled and painted dragons, mysterious in the moonlit room.

Here

glistened a gem, lighted by a gem, twinkling in the gray light that

trickled down delicate tracings of incrusted silver, to flash in one vivid

spot, where a virtue held an embossed cup beneath her face, wreathed

with

lingering light gliding round a contour. The faces smiled in the

luminous

gloom.

How his temples ached, as he clasped them with dissolving hands

how the

obstinate smile of one virtue haunted his brain! Yea, in his very

orthodox

cushions.

She lingeringly moved her taper fingers round the rim of the cup,

her eyes

fixed on his, weaving circles of exquisite sound, distant, faint,

but full

of passion, like a bar from Lohengrin; round and round

slowly,

caressingly; the web of visible melody floated from the golden

rim. She

poured a gummy liquid, opalescent at her touch; it glowed,

bubbled,

throbbed, and rose passionately towards her; now incandescent

it sweeps

through the prince’s veins, dancing and seething there; it

bubbles round

him, blending his being with its dazzling liquidness. The

prince staggered

to his feet, the cold floor electrified him; he flung away

his heavy

wreath, heavy with a relentless and sickly scent.

29

The moonlight flowed on the veined pavement.

The breath of endless flowers was tossed towards him as from a

censer,

sickening him; sickly was the colour of his royal robes, sickly

the

pavement reflecting the sinuous yellow folds gliding languidly on

the

glassy surface of polished steps.

The moonlight flowed on moon-coloured jade, slept in a dreamy

haze on steps

of jet, in a copper basin it melted among strange dreaming

water-plants

with fat buds.

The Prince feared he loathed all flowers, as he bathed his head with

wetted

hands, then flung himself on a grassy bank.

There swarmed small tribes in worlds of mosses, in worlds of

lichen on tree

trunks; a moth flew by, brave with its symbols painted

on its wings, its

rainbows, its blood-coloured hearts.

The Cup of Happiness! The Cup of Happiness!

The grasses sighed, and rolled, to the night air, full of that passionate

murmur, the pulsing of the sap, the yearning lisp of the whispering leaves

and rustle of heavy petals.

Something tinkled and trilled, ecstatically kissing soft mosses,

and chiming

through pebbles, to swim through lush stalks, where pined

some melancholy

toad, gasping a mournful, monotonous croak that made

the drooping poppies

swoon on their stalks. A flower hung near, shaped

like an amorous mouth, a

flower with lips! He flung his slipper into a

fragrant bush, and the rose

petals fell in a mass, with the swish of a

trailing robe.

The king felt sick, so he left his kingdom.

The orchestra rolls into a despairing wail. The curtain rises

’mid peals of thunder; twisted

trees sway to and fro in agony. In the

foreground, filled with trailing thorns, beneath which

crawl wicked

snakes, croaks a raven. The sun sets lurid in the distance with extended and

poetical rays. Now and again a faint flash of lightning shines

fitfully at a side wing, near a

palm-tree.

PALM-TREE.

Colophium, away! you are singeing my leaves. I was painted by

an

Academician. You must strike that conceited Oak; ’tis your part. I

am a

symbol of virtue.

LIGHTNING.

I flash where I am told, pitiful canvas. Do you not believe in

Providence?

You have made me miss my thunder, which has rolled

twice.

THUNDER (behind).

Silence there! how came you in this scene? Your place is in the

next act.

We are in an imaginative landscape.

Snakes hiss approvingly; carrion birds, flying across the sun,

cry, Away! away! On the

other hand some Oak-trees in the background

blame the levity of the Lightning, for a palm-tree

is a palm-tree,

etc., …. after all. The Lightning flashes again.

30

PALM-TREE.

Ugh! it has singed my paint. The world has turned atheist since

I was

young.

Gnarled roots and brambles writhe and clutch. A bird is caught

by thorny branches to be

devoured by a snake gliding from a rose-bush

on which hangs a spider web with a butterfly wing

earnestly

painted.

Enter MONSTER

who, fortunately for our story, has spent years in getting a

regulation thorn quite thoroughly into

his right paw, that a hero or

saint passing his way might be the means to higher ends; for he felt

himself worthy of higher things, longed to be fed on tipsy-cake, to own a

pastrycook’s shop, and

saw the Cup of Happiness in a mincemeat

bowl.

When? whither? where?

Takes out a pocket-book, eagerly notes this down to write

verses on, and groans aloud.

Trees, Orchestra, Thunder, all groan

lugubriously. The Lightning flashes near Palm-tree;

this excites

universal indignation, and the snakes and thorns shout Away with both of

them!

Away! Away!

LIGHTNING (to Palm-tree).

We are misunderstood. I did not notice how beautifully you are

drawn.

Thorns and snakes are -a great mistake in nature.

PALM-TREE.

Young friend! you are wise for your years; let us form a society to

suppress them—and immodest literature.

MONSTER.

I swirled into Renaissance arabesques unnoticed. The world is

without

decorative instincts.

The limelight falls on the floor, flashes on the Palm-tree (who

feels flattered), and settles

itself on right entrance.

Enter PRINCE.

For three days I have wandered in a too uncongenial atmosphere; all

strength lacks grace—how true!—all grace, of course, lacks strength—

so I

was offered a post on a review. There is an incompleteness about

most

things, if I may be allowed to say so. This spot, however, seems

tuned to

a nobler key, not so grossly realistic as most; I really think my

higher

nature will be touched presently, and my ominously swelling cloak

makes, I

feel, a nobly decorative mass against the setting sun.

Monster introduces himself with frank manliness. The thorn is

extracted to the huge

appreciation of pit and gallery. The situation

is too literary—The Prince and Monster—the

latter rubs his claws

complacently; gives so full and fruity a sound to “Your Highness,” the

honest scenery feels quite jealous; quotes a few well-chosen verses on

Happiness, and remains

in an ecstacy with tearful eyes before a vision

of a mincemeat bowl floating through space to slow

music.

PALM-TREE (sotto voce).

If you don’t flash brightly against me, I’ll break up the partnership.

BUTTERFLY-WING.

All is not gold that glitters.

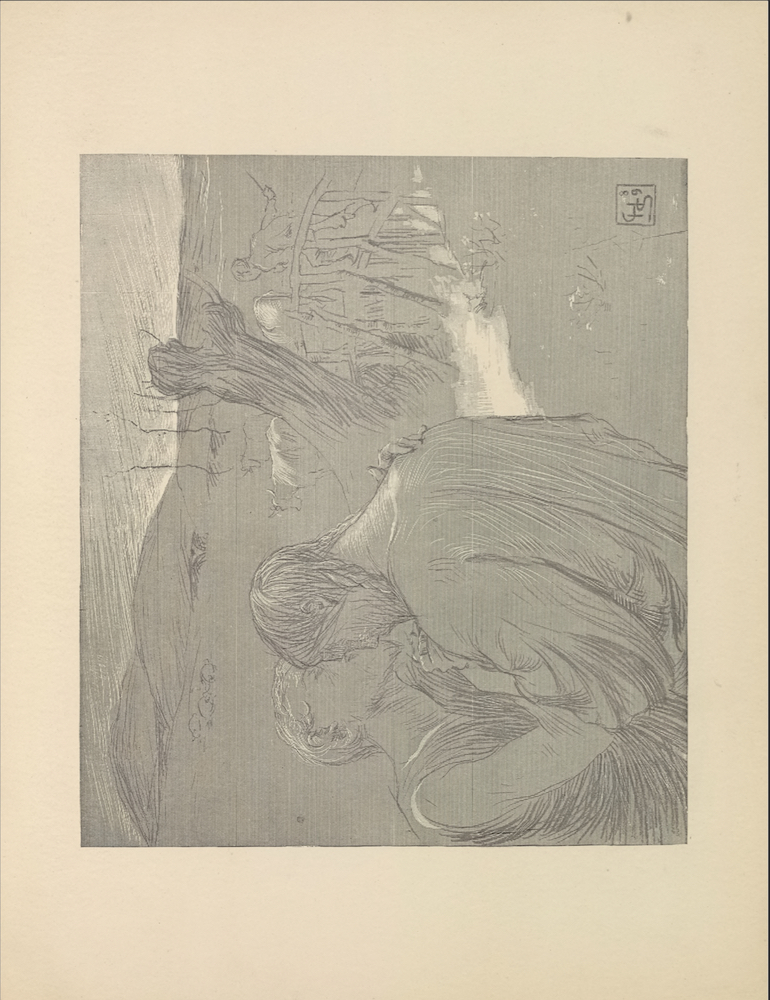

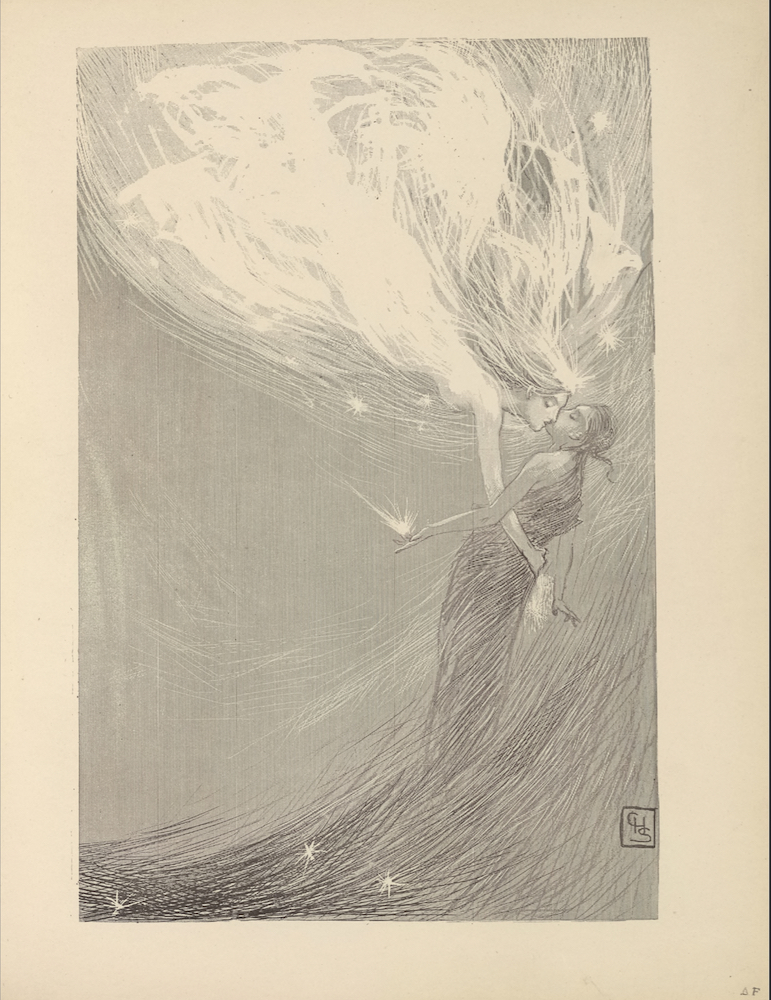

Enter FANTASY.

Her form, sinuous as a willow, is swathed in some light

exquisite material, and garlanded

with dainty twigs of jessamine, and

nodding columbine; her jewelled and braided hair knots

31

round an opal; above her brow flutters a black butterfly,

circled by her nimbus tinted like a

dissolved topaz; she holds an iris

twined with ivy, and looks at the Prince over her shoulder

whilst she

holds a red carnation to her parted lips.

Ah! sweet my love! sweet Prince, dear wretch! I love thee! The

word lies

softer than soft velvet tinged a deepening violet, not softer than

my

passion. The word is a poor counterfeit, and apes the truth; as a

dark

shadow, crawling from the sun, is image of the truth that gives it

being.

The word is lourd and gross, I would give sound to it, with a

deep cello’s

note, or sigh of some flosh petal falling with scarce audible

sound, on

floor of ivory flooded with living sun.

How many, how many have been my lovers! They kissed my eyes,

and

passionately my neck, for I am, and was, beautiful. But look you

on my

face, my white face, how many have shed heavy tears; their tears

circle my

throat; for gently I gathered these, and they became bright

pearls to

place upon my bosom, my white breasts like to the domes of

some fair

silvered shrine.

At this she bares her bosom, a pale tea-rose nestles there, the

butterfly flutters to her

mouth.

List! the frightened birds have chirped themselves to drowsiness;

the

muffled sound of distant thunder gives but a deepening zest to the

mad

song of that fond silly bird, that lifts its voice to passion’s utter-

ance. Ah! I could love you thus, and trill a sweet linked text, to melt

your senses into rapt delight, till dazed by throbbing notes, that dance

so swiftly, your heart stops faint within you; and lo! the next notes

drown all remembrance of what has passed—in full enjoyment.

PRINCE.

Bright spirit! your name? I do not know you.

FANTASY.

My name, my name? I have many names; men called me after

some fair women. I

was born of flowers in Adam’s brain; the warm

wind gave me breath; this I

remember me; poor Adam damned!—

They called me Lilith. But the blossoms

still remember me, mimic the

soft veinings of my skin, and glow with

hidden passion they had not then

confessed. Then angels fell, because that

I was sweet to look upon, and

brought from sleepy depths quaint coral

wreaths that yet blush red with

the remembrance. (She sighs.) My presence

moved man to lovely song;

it echoes still, and ever will resound; great

cities grew, piled high like

cliffs, fronted in image of my face, painted

pink in reverence for my flesh.

Soft lyres were turned to curvings of my

waist, to tell how I was fed by

doves. But that was not so royal, or so

glad, as Solomon’s idolatry; he

kissed my footsteps and my dress, on

polished floor of crystal that multi-

plied my image. Poor king! Poor

kings! But no! My love, if

death, is life!

She weaves garlands round her wrists; gradually her eyes close;

she makes a vague ges-

ture towards her head.

32

Ah me! list! list! I hear the tread, the growing dread re-echoes

in my

heart. Tread! tread! and dust in dark clouds as a sign. (She

gives a

scream.) The violet sea is stained with crow-black sails, and sets

a

bloody sun. The city is on flames! on flames! and blots with lurid

red the

circling heaven.

She pauses, dreamily looks for a wound near her bosom, but

finds nothing. Slowly she

takes a pearl from her throat and sadly

drops it. The sound makes her start; but laughingly

she loosens her

hair; it falls round her in a golden cloud; she holds her face with both

hands,

and says:

Ah love! I had many, many, lovers, lovers! look at these ame-

thysts and

pomegranate blossoms; these opals that hold fallen and still

passionate

spirits, glowing in cells of milky crystal; faint beryls that

have dreamt

the dreams of the sea at noon ; these sapphires like dying

eyes; listen to

the song of this splendid ruby, how full of glowing mirth

and rich

delight; it calls the damask rose sick and sentimental. All

these, and

much besides, have men found and devised, to my good

pleasure.

She kisses her hand to the Prince, who leans against the

Palm-tree. She beckons to him.

PALM-TREE (severely).

Madam, I am married!

Enter LIGHTNING

with a pair of spectacles he has borrowed from a

satirist.

Madam still possesses her illusions!

FANTASY.

Do you wish to appeal to the gallery? Away, poor fly-blown stage

property;

or I’ll blow you out.

[Exit LIGHTNING.

The whole stage looks shocked, even the limelight

blushes.

PALM-TREE.

When I was young, however ….

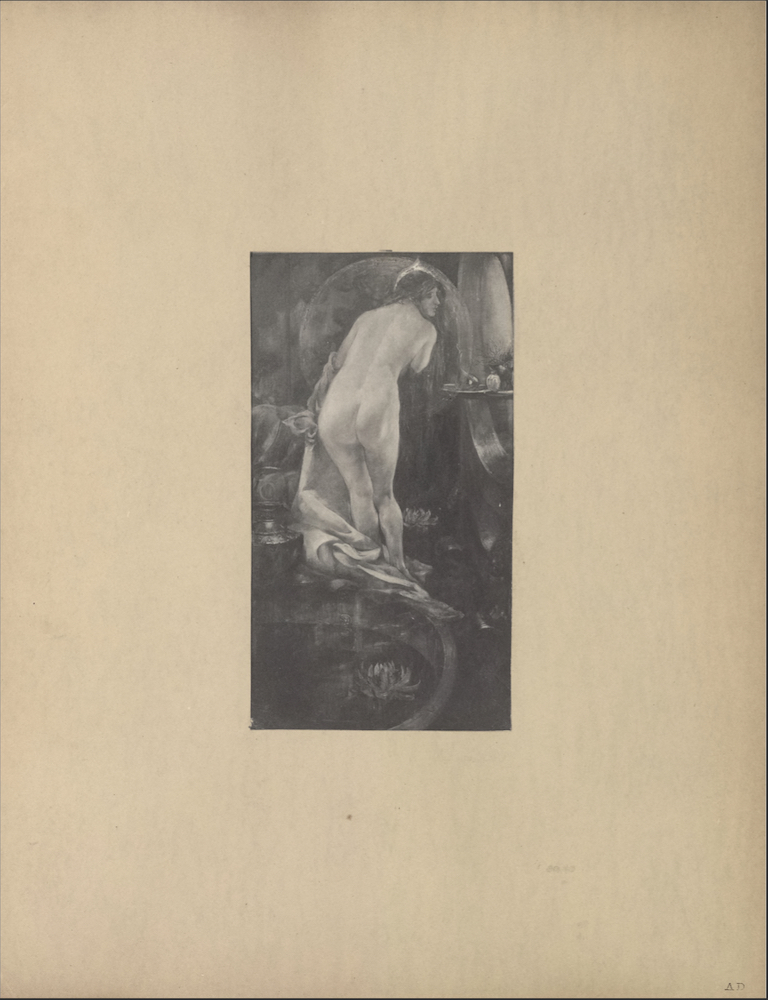

But Fantasy escapes from her clothes, and with her hair

streaming behind her like a comet

dances about the stage

naked.

PRINCE and BACK SCENERY.

The play must stop if this goes on!

MONSTER,

though quite a freethinker, is even more shocked than the

Palm-tree.

The Cup of Happiness will be compromised!

He pulls out an article on. But Fantasy, knotting her white

arms behind her head,

dissolves into space, leaving behind her only the

glimmer of her feet.

[Exeunt.

A SEED.

I swell, I grow, I am growing, I shall be a beautiful tree.

A WORM (pulling at it).

Nonsense! a tree? We are worms! worms!

(To be continued.)

C. RICKETTS.

33