Lionel Johnson

(1867–1902)

Poet and critic, Roman Catholic convert and staunch proponent of the faith, and an inveterate alcoholic, Lionel Pigot Johnson typifies the spirit of the doomed “yellow nineties.” Johnson also embodies contradiction. “One should be quite unnoticeable” (Yeats 167), he said once to his friend and comrade, W. B. Yeats (1865-1939). But even though Johnson was a recluse whose personality bloomed in backstage settings in the wee hours of the morning, his name is virtually synonymous with the period. His relationship with decadence is similarly complicated. Johnson consciously sidesteps the label and yet he is in its midst as he is invariably grouped with fellow poets Ernest Dowson and Arthur Symons.

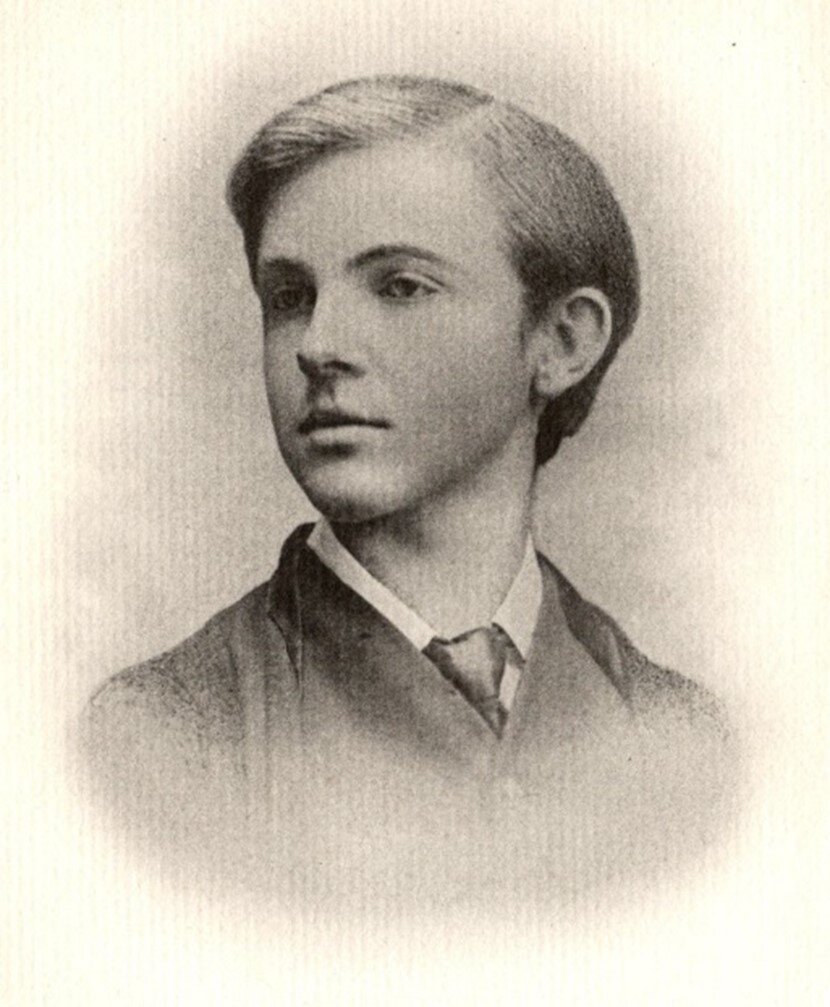

The son of William Victor, an infantry captain, and Catharine Delicia Walters, Johnson was born in 1867 in Broadstairs, Kent, and was of English and Welsh stock. Although he had only traces of Irishness in his blood, he participated in the Celtic Revival and became a patriotic supporter of Irish history and culture. The novelist and Savoy contributor Olivia Shakespear (1863-1938), who at one point became intimate with Yeats, was Johnson’s cousin and a fervent admirer of him. Johnson was of short stature, fair-complexioned and cherubically baby-faced, yet with a stern, grave temperament. Frank Harris summed him up as “a sort of young old man” (180). He was a repressed homosexual who led a life of seclusion, devotion, and reflection. His strong Catholic faith helped him seek solace and self-control in cultivated celibacy. He read Classics at St. Mary’s, Winchester College, Hampshire for six years and, following a scholarship, resumed his studies in New College, Oxford in 1886 for four years, graduating with a first in Literae Humaniores. At Winchester he edited the Wykehamist to great success, and at Oxford he became president of the New College Essay Society. He won prizes for his poems and essays at both institutions.

Oxonian traditionalism resonated with Johnson’s interest in Roman Catholicism and classicism. He developed a branch of anti-dogmatic Catholicism informed by the ideas of Tractarian theologian Cardinal John Henry Newman (1801-1890) and was inspired by Matthew Arnold’s latitudinarian Christianity. Some of his close friends at Oxford included Campbell Dodgson (1867-1948), Arthur Galton (1852-1921), and Lord Alfred Douglas (1870-1945) who was also a Wykehamist confrere. One of Johnson’s tutors was Walter Pater (1839-1894) whom he idolized and praised in his writings throughout his life. In a poignant elegy of “Walter Pater” that could not have been published during his lifetime, Johnson referred to his mentor as a “Hierarch of the spirit, pure and strong, / Worthy Uranian song” (Poetical Works 288). But his devotion to Paterian intense moments and sensuous impressions does not exactly feed into the aestheticist religion of art as it does with Dowson and Oscar Wilde. Instead, Pater’s “moments” in Johnson’s work are in harmony with, yet subject to, Catholicism’s sense of divine beauty in simple things. Johnson’s letters to his friend Earl Frank Russell (1865-1931) (brother of philosopher Bertrand Russell) at Winchester show that in the 1880s he was interested in the tenets of theosophic Buddhism, notably the spiritual principles that link the Buddha with Christ. These letters, published by Russell in 1919, are intellectually vigorous, performative, self-conscious, and hence consistent with Johnson’s predisposition to express himself in clandestine or private settings. The young Johnson flirted with the idea of taking holy orders. Eventually he was baptized a Roman Catholic in 1891 on St. Alban’s Day.

Johnson accumulated bad habits; he was an insomniac and a dipsomaniac. His drinks of choice were whiskey and absinthe. Wilde noted the contrast between Johnson’s exquisite youthfulness combined with his short stature and his deleterious excesses, remarking wittily “that any morning at eleven o’clock you might see him come out very drunk from the Café Royal, and hail the first passing perambulator” (qtd in Sturgis 407). Johnson admired The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) and composed a paean to Wilde’s novel in Latin, “In Honorem Doriani Creatorisque Eius.” He was the person who introduced Douglas to Wilde in the latter’s residence in Tite Street. But later he came to resent Wilde due to the scandalous aspect of the relationship with Douglas, recording his feelings in the poem “The Destroyer of the Soul” (Poems).

The 1890s was the decade when Johnson was most successful as a man of letters. He took rooms in 20 Fitzroy Street and made a living by penning literary reviews and critical essays, many of them unsigned, in The Spectator, The Academy, The Daily Chronicle, and The Anti-Jacobin, with mostly signed pieces in The Outlook and The Speaker. His reviews tackled a vast array of literary personages and intellectuals from Classical Antiquity to his own day. Johnson liked to insert Latin phrases in his prose, which was erudite yet clear, breathing a fresh air into any topic. Around 1894 he delivered a portentous lecture on Ireland’s “Poetry and Patriotism” for the Irish Literary Society in London. He visited Ireland a few times in the decade to give lectures. Most importantly, he joined the famous Rhymers’ Club, founded by Yeats and Ernest Rhys (1859-1946), based in the pub, “Ye Old Cheshire Cheese,” in Fleet Street. According to Yeats, Johnson was the “theologian” (211) of the group. Johnson contributed a dozen of his most accomplished poems across the club’s two anthologies, in 1892 and 1894.

Johnson published three books during his lifetime: The Art of Thomas Hardy (1894), Poems (1895), and Ireland with Other Poems (1897). These came out with Elkin Mathews’ publishing house. Religious experience, sensuous beauty, musical imagery, and Irish patriotism dominate his verses. He employed a wide variety of metrical, rhyming, and stanzaic schemes, with an unusual fondness for the heroic couplet. His poetry is chiselled and full of round, melodious accents. He often preferred the forms of the lofty hymn, praise, and ode, shot through with a mellow hint of melancholia. Poems is the capstone of his work and contains several outstanding pieces such as “The Precept of Silence,” “By the Statue of King Charles the First at Charing Cross,” “Mystic and Cavalier,” “To a Passionist,” and “The Dark Angel.” The latter, with its teasing ambiguity, pulsating atmosphere, split self and obsession with sin and damnation, is an iconic masterpiece and a favourite with anthologists. “The Dark Angel” offers a fascinating glimpse into Johnson’s spiritual and physical wrestling with his homosexuality.

One of the most interesting aspects of Johnson’s output is his contributions to the little magazines of the period. He wrote essays and poetry for Alfred Douglas’s Oxford undergraduate magazines The Spirit Lamp (1891–1893) and The Chameleon (1894). In the latter he contributed the essay “On the Appreciation of Trifles” anonymously. He joined the coterie of The Century Guild Hobby Horse, an elitist outlet that promoted high aestheticism. The magazine was edited by Herbert Horne (1864-1916) and Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851-1942), and was flanked by Selwyn Image (1849-1930) and others. The headquarters of the Hobby Horse circle were in the same building where Johnson resided in Fitzroy Street. Johnson published poems in the Hobby Horse, as well as prose pieces including an appreciation of Pater’s writings and a review of a performance of Robert Browning’s tragedy Strafford (1837). In the October 1890 volume, Johnson published “A Dream of Youth” (1889), a titillating homoerotic poem in minimally coded sensual language. It unsurprisingly raised eyebrows and was expurgated in later published versions. “A Note upon the Practice and Theory of Verse at the Present Time obtaining in France” (Hobby Horse April 1891) is an atypical and yet indispensable document that provides virtuoso definitions of the decadent and symbolist movements. Johnson’s response to these movements was problematized by his patriotic principles. In his lecture on Irish patriotism and poetry, a few years later, he repudiated the “art for art’s sake” slogan as an English vice in favour of what he called the “curiosa felicitas” (Post Liminium 166) of the Celtic style. The three sonnets he contributed to the August issue of Symons’s The Savoy (1896), “Hawker of Morwenstow,” “Mother Ann: Foundress of the Shakers,” and “Münster: A.D. 1534,” form a rich mingling of “Catholic faith and Celtic joy” (Poetical Works 255).

Johnson is not noted for his short stories, but his scant specimens in this form are of a superb quality and yield useful insights into his worldview and aesthetic ideas. His one-off contribution to The Yellow Book is “Tobacco Clouds” (October 1894), an intense homage to Paterian impressionism. This is an experimental, bookish, meditative short story on indulging in the simple pleasures of life. It should be noted that “Tobacco Clouds” invites comparison with Charles Ricketts’s “Sensations” in the first number of The Dial (1889). Ricketts’s story is about the aesthetic effects of a thunderstorm on a narrator with a morbid fascination with Church Mass. Conversely, the leitmotif of tobacco in Johnson’s story could be also seen as a piece of experiential theology, an inventive subterfuge through which Johnson unfolds his branch of latitudinarian Catholicism in a secular setting. Read in this manner, Johnson’s story advances spirituality in the humble exercise of the senses, the divine presence in little things over prescribed moral mores.

Each of the two lavish volumes of The Pageant, edited by Charles Hazelwood Shannon and J. W. Gleeson White, contains a story by Johnson, “Incurable” (1896) and “The Lilies of France” (1897). A learned satire of the Pre-Raphaelites and his decadent contemporaries, “Incurable” is about a thirty-year old poet, just like Johnson himself at the time of the tale’s publication, who has grown despondent over the futility of his own verses and their being out of tune with the world. His resigned disposition drives him to attempt suicide by plunging into the river, only to climb back ashore. Like “Tobacco Clouds,” “Incurable” is a sketch about introspection and self-absorption that is as psychologically rich as it is ironic. Although Johnson here superbly parodies Symons’s erotic lyrics, at the same time he pokes fun at himself and alludes to his own anxieties about how he is perceived as a poet. Finely crafted yet not well known, “The Lilies of France” is a story deftly laden with historical references and colour symbolism. It is an anti-clerical diatribe and a critique of scientific materialism and impious iconoclasm. The politically-minded, self-righteous Cardinal Gustave Vanier represents the royal purple of power and pomp, the rigid official structures of the ecclesiastical edifice. He is contrasted with the humble Canon Laval (a pun on love-all) who represents humility and the simplicity of the Catholic faith. The Cardinal’s murder at the end of the story is ironic, as it is an event that ends in martyrdom. In many ways the story sheds light on Johnson’s religious views.

Johnson had a weak constitution, but his alcoholism was mostly to blame for his early death in 1902. Looking ill, on 29 September he got dressed for the evening, left his rooms in Clifford’s Inn, and strolled to the Green Dragon pub in Fleet Street. Here he fell from his bar stool, unconscious; he died in St. Bartholomew’s Hospital five days later of a ruptured blood vessel (misdiagnosed post-mortem as a fractured skull). Ezra Pound, who appreciated the “marmoreal” (marble-like; a favourite epithet of Johnson’s) qualities of Johnson’s poetry, immortalized him in Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), adding: “the pure mind / Arose toward Newman as the whiskey warmed” (15). Alongside his bosom friend Ernest Dowson, Lionel Johnson cements the myth of the “tragic generation” of the 1890s. There is much to say about Johnson’s eremitism, Roman Catholicism, Celtic patriotism, and fraught relationship with art for art’s sake, especially in relation with his self-image and Uranian tendencies. What is certain is that Johnson was a soi-disant outsider whose short life and impassioned output were underpinned by internal struggle.

©2021, Kostas Boyiopoulos, Honorary Fellow, Department of English Studies, Durham University, Durham, United Kingdom

Selected Publications by Lionel Johnson

- The Art of Thomas Hardy. London: Elkin Mathews and John Lane; New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1894.

- Incurable: The Haunted Writings of Lionel Johnson, the Decadent Era’s Dark Angel. Edited by Nina Antonia, Strange Attractor Press, 2018.

- Ireland with Other Poems. London: Elkin Mathews; Boston: Copeland and Day, 1897.

- “A Note upon the Practice and Theory of Verse at the Present Time Obtaining in France.” The Century Guild Hobby Horse, vol. 6, 1891, pp. 61–66.

- Poems. London: Elkin Mathews; Boston: Copeland and Day, 1895.

- Poetical Works of Lionel Johnson. 1915; rpt. Elkin Mathews; Macmillan, 1917.

- Post Liminium: Essays and Critical Papers by Lionel Johnson. Edited by Thomas Whittemore. Elkin Mathews, 1911.

- Some Winchester Letters of Lionel Johnson. George Allen and Unwin; Macmillan, 1919.

Selected Publications about Lionel Johnson

- Bartlett, Mackenzie. “Resituating Lionel Johnson.” English Literature in Transition: 1880-1920, vol. 53, no. 1, 2010, pp. 108-110.

- Cevasco, G. A. Three Decadent Poets: Ernest Dowson, John Gray, and Lionel Johnson: An Annotated Bibliography. Garland, 1990.

- Charlesworth, Barbara. Dark Passages: The Decadent Consciousness in Victorian Literature. University of Wisconsin Press, 1965.

- Green, Sarah. “Light on the Dark Angel: Lionel Johnson and the Literary Life of the 1890s.” Times Literary Supplement (TLS), 2 August 2019, 12.

- Harris, Frank. Contemporary Portraits: Second Series. N.p., 1919.

- Lockerd, Martin. Decadent Catholicism and the Making of Modernism. Bloomsbury, 2020.

- Lovatt, Gabriel. “Lionel Johnson’s Modern Ruins.” Victorian Poetry, vol. 52, no. 4, 2014, 679-698.

- Paterson, Gary H. At the Heart of the 1890s: Essays on Lionel Johnson. AMS Press, 2008.

- Pittock, Murray G. H. “The Poetry of Lionel Johnson.” Victorian Poetry, vol. 28, no. 3/4, 1990, 43-60.

- Pound, Ezra. Hugh Selwyn Mauberley. The Ovid Press, 1920.

- Sturgis, Matthew, Oscar: A Life. Head of Zeus, 2018.

- Whittington-Egan, Richard. Lionel Johnson: Victorian Dark Angel. Capella Archive, 2012.

- Yeats, W. B. Autobiographies. 1955; rpt. Macmillan, 1980.

- Invectives. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1896.

- Invectives. Paris: Léon Vanier, 1896.

MLA citation:

Boyiopoulos, Kostas. “Lionel Johnson (1867–1902),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/johnson_bio/