The Yellow Book

An Illustrated Quarterly

Volume V April 1895

Contents

Literature

I. Hymn to the Sea . . By William Watson . Page 11

II. The Papers of Basil Fillimer H. D. Traill . . . 19

III. A Song . . . . Richard Le

Gallienne . 33

IV. The Pleasure-Pilgrim

. Ella D’Arcy . . . 34

V. Two Songs . . . Rosamund

Marriott-Watson 71

VI. The Inner Ear

. . Kenneth Grahame . . 73

VII. Rosemary for Remembrance Henry Harland . . 77

VIII. Three Poems . . Dauphin

Meunier . . 101

IX. Two Studies

. . . Mrs. Murray Hickson . 104

X. The Ring of Life . . Edmund

Gosse . . 117

XI. Pierre Gascon

. . Charles Kennett Burrow . 121

XII. Refrains . . . Leila Macdonald

. . 130

XIII. The Haseltons . . Hubert Crackanthorpe . 132

XIV. Perennial . . . Ernest

Wentworth . . 171

XV. For Ever and Ever

. . C. S. . . . . 172

XVI. Mr. Meredith in Little . G. S.

Street . . . 174

XVII. Shepherds’ Song

. . Nora Hopper . . . 189

XVIII. The Phantasies of Philarete James Ashcroft Noble . 195

XIX. Pro Patria . . . B. Paul

Neuman . . 226

XX. Puppies and

Otherwise . Evelyn Sharp . . . 235

XXI. Oliver Goldsmith’s Grave W. A. Mackenzie . . 247

XXII. Suggestion . . . Mrs. Ernest

Leverson . 249

XXIII. The Sword of

Cæsar Borgia Richard Garnett, LL.D., C.B….. 258

XXIV. M. Anatole France . The Hon.

Maurice Baring 263

XXV. The Call

. . . Norman Gale . . . 280

XXVI. L’Evêché de Tourcoing . Anatole France . . 283

XXVII. A Fleet

Street Eclogue . John Davidson . . 299

Art

The Yellow Book—Vol. V.—April, 1895

Art

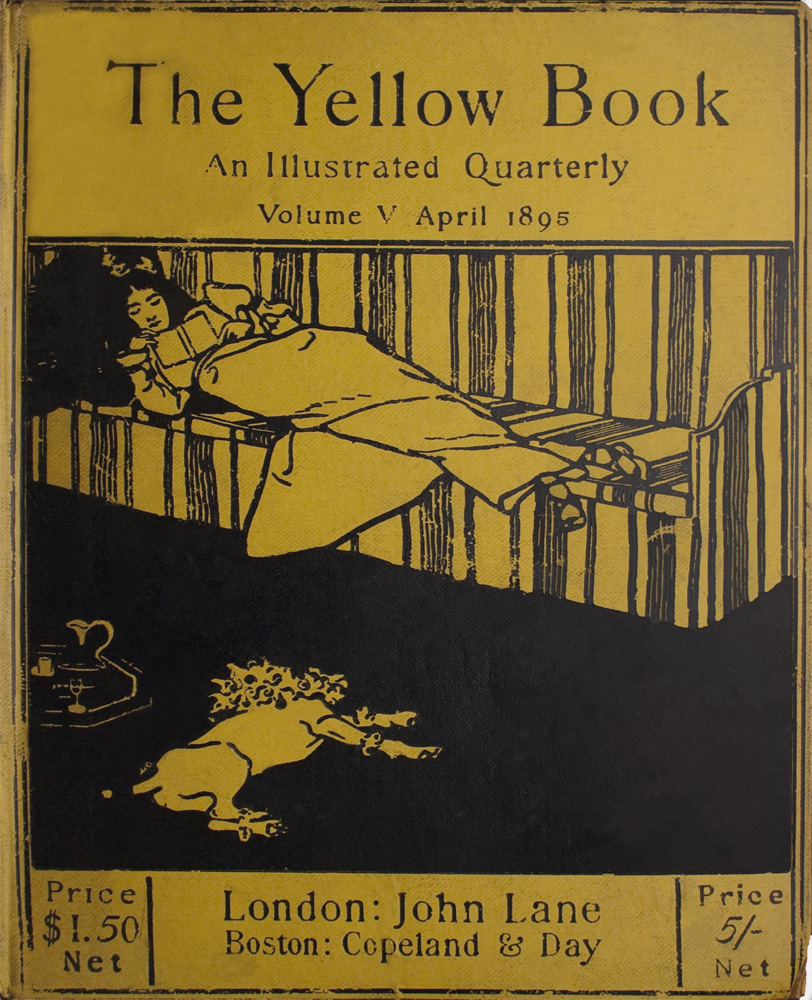

Front Cover, by Patten Wilson

Title Page, by Walter Sickert

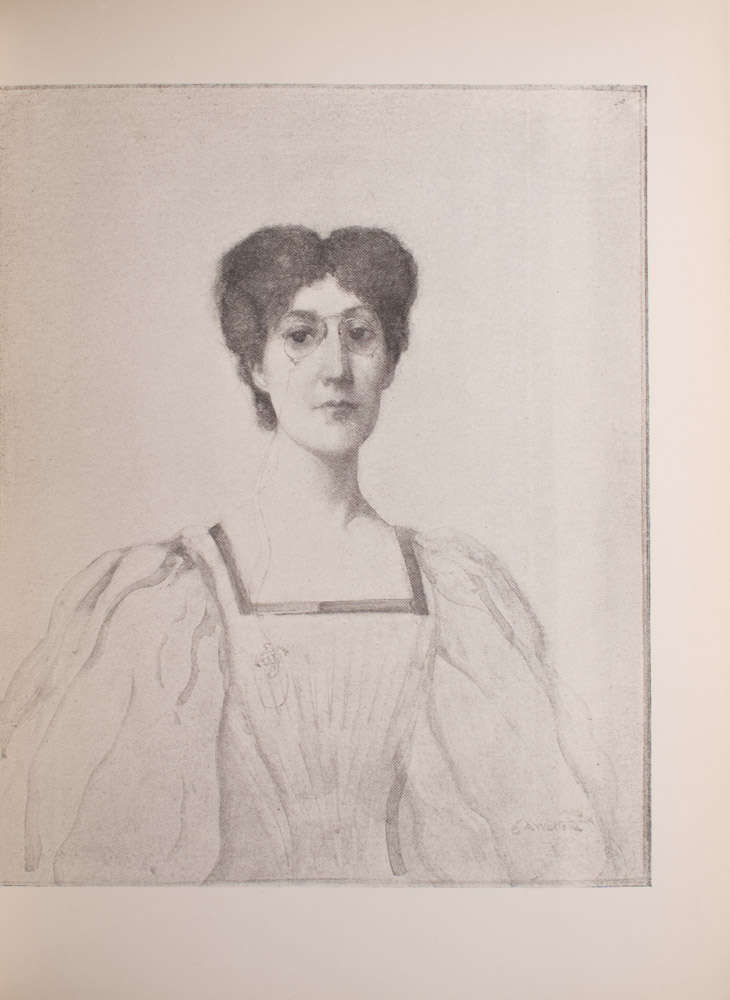

I. Bodley Heads. No. 3 : George Egerton By E. A. Walton . . Page 7

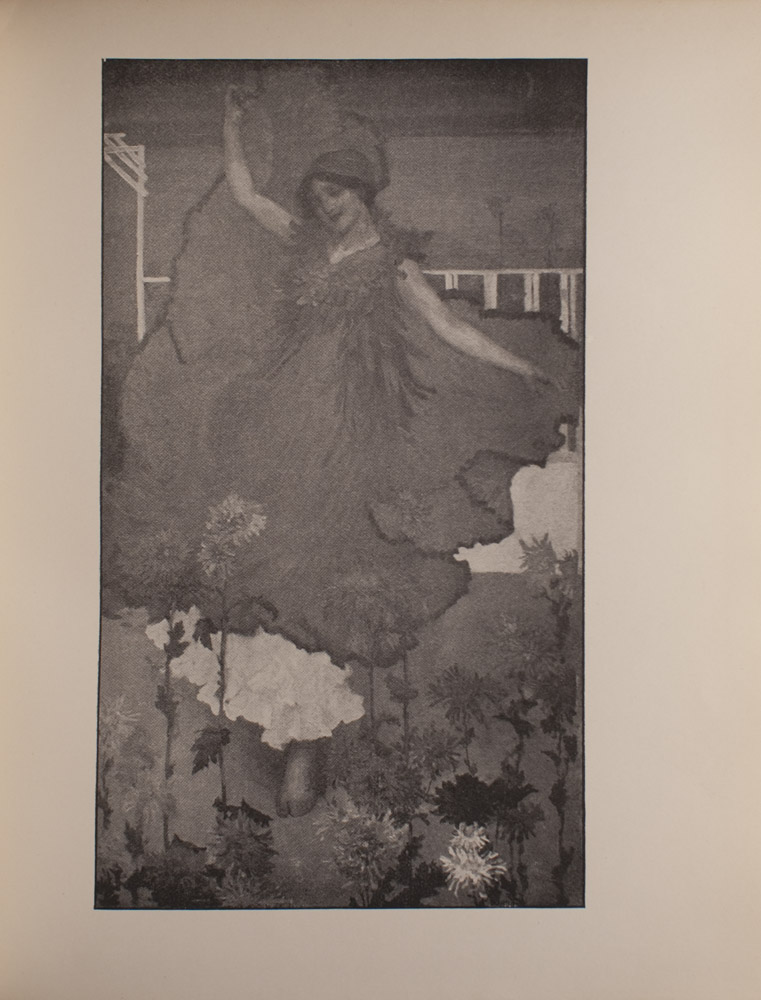

II. The Chrysanthemum Girl R. Anning Bell . . 68

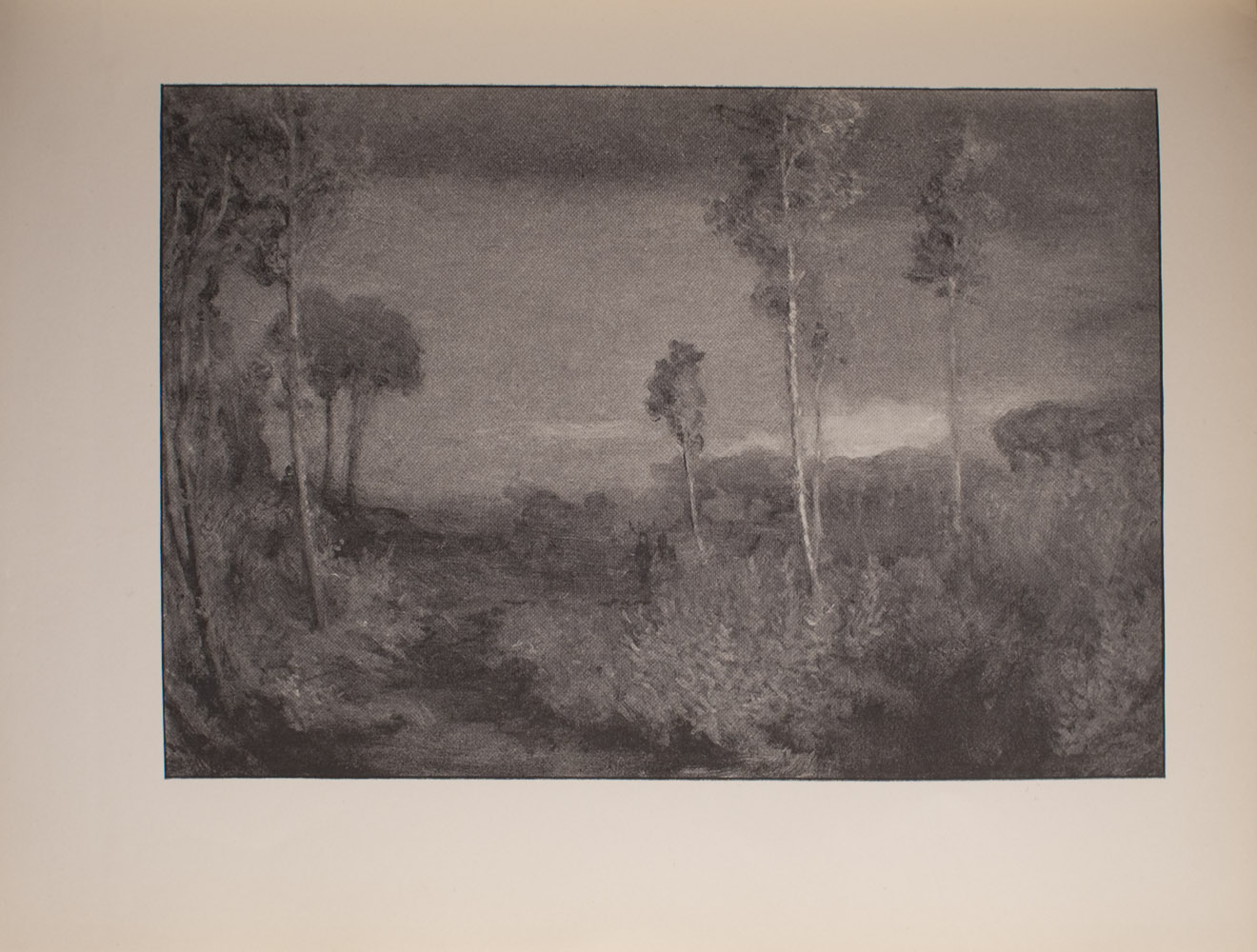

III. Trees . . . . Alfred Thornton

. . 97

IV. Study of Durham . . F. G. Cotman . . 118

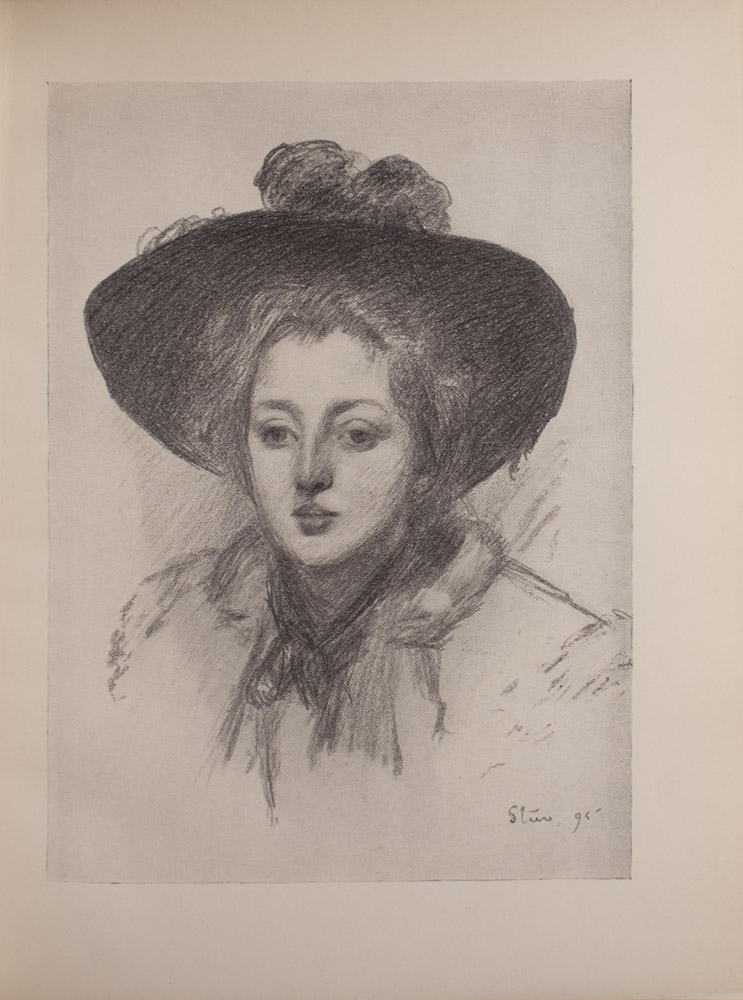

V. Portrait of Mrs. James Welch P. Wilson Steer . . 164

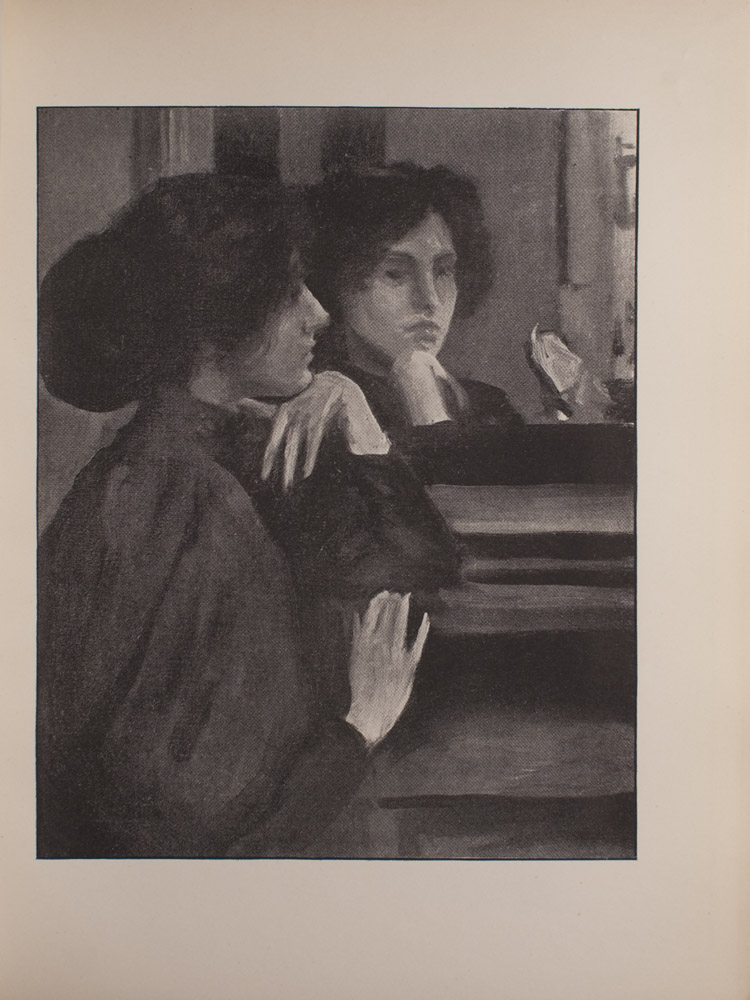

VI. The Mantelpiece .

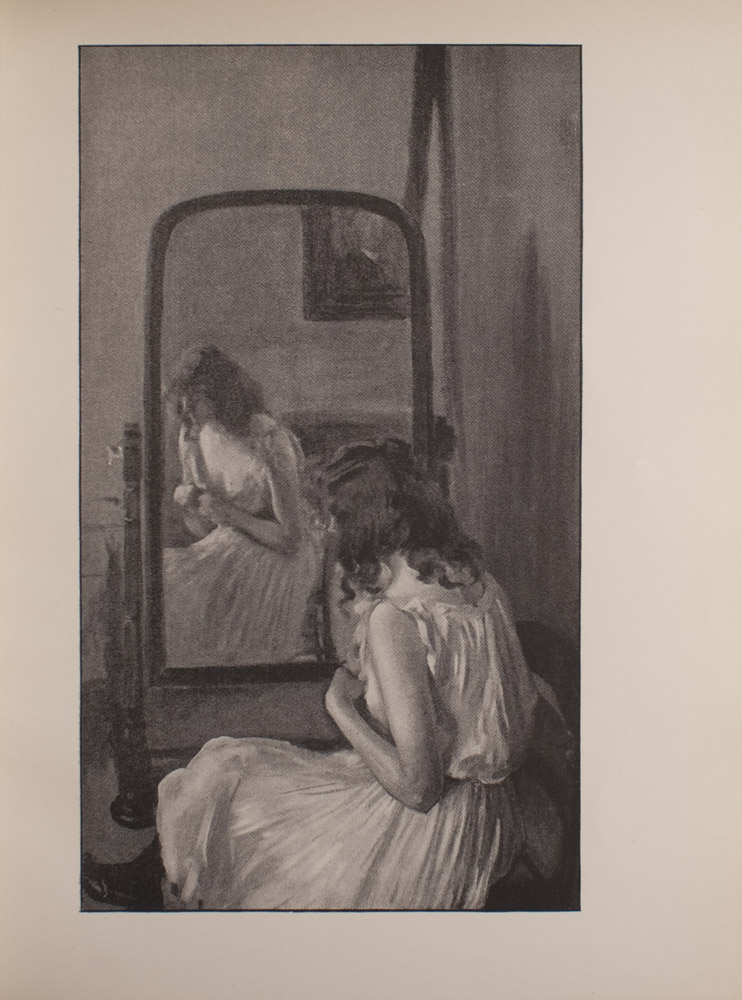

VII. The Mirror . .

VIII. The Prodigal Son . . A. S.

Hartrick . . 186

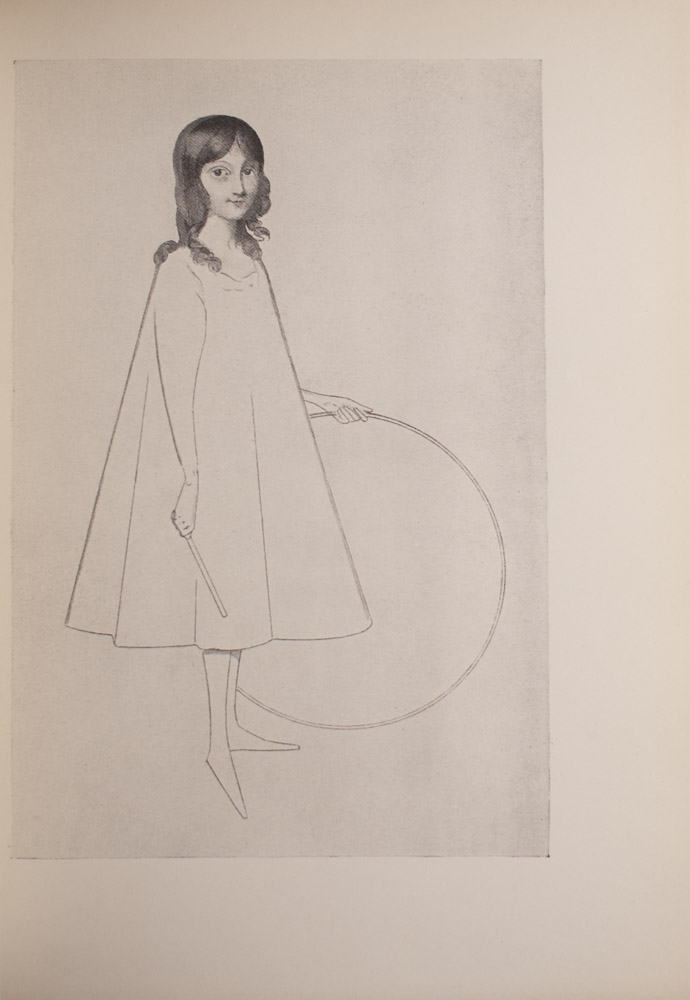

IX. Portrait of a Girl

. . Robert Halls . . . 191

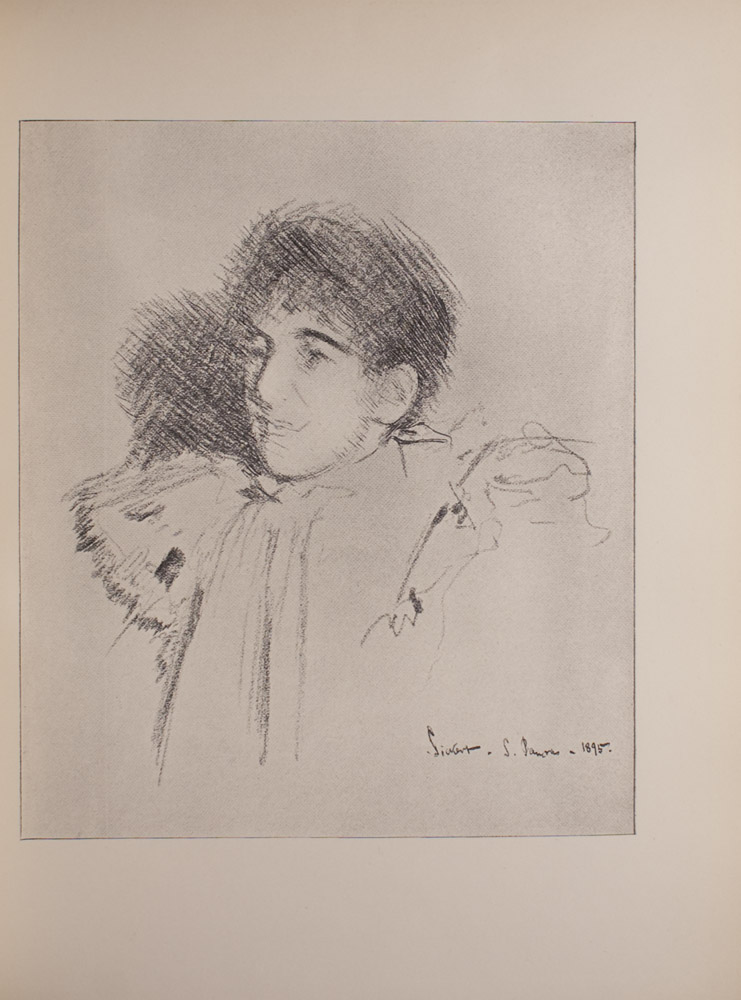

X. Portrait of Mrs. Ernest Leverson Walter Sickert . . 229

XI. The Middlesex Music Hall

XII. A Sketch . . . Constantin Guys

. . 259

XIII. Study of a Head . .

Sydney Adamson . . 290

XIV. A Drawing . . . Patten Wilson

. . 293

Back Cover, by Aubrey Beardsley

Advertisements

The Editor of THE YELLOW BOOK can in no case

hold himself responsible for rejected manuscripts ;

when, however, they are accompanied by stamped

addressed envelopes, every effort will be made to

secure their prompt return. Manuscripts arriving un-

accompanied by stamped addressed envelopes will be neither

read nor returned.

Hymn to the Sea*

By William Watson

I

GRANT, O regal in bounty, a subtle and delicate largess ;

Grant an ethereal alms, out of the wealth of thy soul :

Suffer a tarrying minstrel, who finds and not fashions his

numbers,—

Who, from the commune of air, cages the volatile

song,—

Here to capture and prison some fugitive breath of thy

descant,

Thine and his own as thy roar lisped on the lips of a

shell,

Now while the vernal impulsion makes lyrical all that hath

language,

While, through the veins of the Earth, riots the ichor

of Spring,

While,

* Copyright in America by John Lane.

While, with throes, with raptures, with loosing of bonds,

with unsealings,—

Arrowy pangs of delight, piercing the core of the

world,—

Tremors and coy unfoldings, reluctances, sweet agitations,—

Youth, irrepressibly fair, wakes like a wondering rose.

II

Lover whose vehement kisses on lips irresponsive are squan-

dered,

Lover that wooest in vain Earth’s imperturbable heart ;

Athlete mightily frustrate, who pittest thy thews against

legions,

Locked with fantastical hosts, bodiless arms of the

sky ;

Sea that breakest for ever, that breakest and never art broken,

Like unto thine, from of old, springeth the spirit of

man,—

Nature’s wooer and fighter, whose years are a suit and a

wrestling,

All their hours, from his birth, hot with desire and with

fray ;

Amorist

Amorist agonist man, that immortally pining and striving,

Snatches the glory of life only from love and from

war ;

Man that, rejoicing in conflict, like thee when precipitate

tempest,

Charge after thundering charge, clangs on thy resonant

mail,

Seemeth so easy to shatter, and proveth so hard to be

cloven ;

Man whom the gods, in his pain, curse with a soul that

endures ;

Man whose deeds, to the doer, come back as thine own

exhalations

Into thy bosom return, weepings of mountain and vale ;

Man with the cosmic fortunes and starry vicissitudes tangled,

Chained to the wheel of the world, blind with the dust

of its speed,

Even as thou, O giant, whom trailed in the wake of her

conquests

Night’s sweet despot draws, bound to her ivory car ;

Man with inviolate caverns, impregnable holds in his nature,

Depths no storm can pierce, pierced with a shaft of the

sun ;

Man

Man that is galled with his confines, and burdened yet more

with his vastness,

Born too great for his ends, never at peace with his

goal;

Man whom Fate, his victor, magnanimous, clement in

triumph,

Holds as a captive king, mewed in a palace divine :

Wide its leagues of pleasance, and ample of purview its

windows ;

Airily falls, in its courts, laughter of fountains at play ;

Nought, when the harpers are harping, untimely reminds

him of durance ;

None, as he sits at the feast, whisper Captivity’s name ;

But, would he parley with Silence, withdraw for awhile

unattended,

Forth to the beckoning world ‘scape for an hour and be

free,

Lo, his adventurous fancy coercing at once and provoking,

Rise the unscalable walls, built with a word at the

prime ;

Lo, immobile as statues, with pitiless faces of iron,

Armed at each obstinate gate, stand the impassable guards.

Miser

III

Miser whose coffered recesses the spoils of eternity cumber,

Spendthrift foaming thy soul wildly in fury away,—

We, self-amorous mortals, our own multitudinous image

Seeking in all we behold, seek it and find it in

thee :

Seek it and find it when o’er us the exquisite fabric of

Silence

Briefly perfect hangs, trembles and dulcetly falls ;

When the aërial armies engage amid orgies of music,

Braying of arrogant brass, whimper of querulous reeds;

When, at his banquet, the Summer is purple and drowsed

with repletion ;

When, to his anchorite board, taciturn Winter repairs ;

When by the tempest are scattered magnificent ashes of

Autumn ;

When, upon orchard and lane, breaks the white foam

of the Spring :

When, in extravagant revel, the Dawn, a bacchante up-

leaping,

Spills, on the tresses of Night, vintages golden and red ;

When,

When, as a token at parting, munificent Day, for remem-

brance,

Gives, unto men that forget, Ophirs of fabulous

ore ;

When, invincibly rushing, in luminous palpitant deluge,

Hot from the summits of Life, poured is the lava of

noon ;

When, as yonder, thy mistress, at height of her mutable

glories,

Wise from the magical East, comes like a sorceress

pale.

Ah, she comes, she arises,—impassive, emotionless, blood-

less,

Wasted and ashen of cheek, zoning her ruins with

pearl.

Once she was warm, she was joyous, desire in her pulses

abounding :

Surely thou lovedst her well, then, in her conquering

youth !

Surely not all unimpassioned, at sound of thy rough seren-

ading,

She, from the balconied night, unto her melodist

leaned,—

Leaned

Leaned unto thee, her bondsman, who keepest to-day her

commandments,

All for the sake of old love, dead at thy heart though it

lie.

IV

Yea, it is we, light perverts, that waver, and shift our alle-

giance ;

We, whom insurgence of blood dooms to be barren

and waste ;

We, unto Nature imputing our frailties, our fever and

tumult ;

We, that with dust of our strife sully the hue of her

peace.

Thou, with punctual service, fulfillest thy task, being con-

stant ;

Thine but to ponder the Law, labour and greatly

obey :

Wherefore, with leapings of spirit, thou chantest the chant

of the faithful,

Chantest aloud at thy toil, cleansing the Earth of her

stain ;

Leagued

Leagued in antiphonal chorus with stars and the populous

Systems,

Following these as their feet dance to the rhyme of the

Suns ;

Thou thyself but a billow, a ripple, a drop of that Ocean,

Which, labyrinthine of arm, folding us meshed in its

coil,

Shall, as now, with elations, august exultations and ardours,

Pour, in unfaltering tide, all its unanimous waves,

When, from this threshold of being, these steps of the

Presence, this precinct,

Into the matrix of Life darkly divinely resumed,

Man and his littleness perish, erased like an error and can-

celled,

Man and his greatness survive, lost in the greatness of

God.

“Tell me not Now”

By William Watson

TELL me not now, if love for love

Thou canst return,

Now while around us and above

Day’s flambeaux burn.

Not in clear noon, with speech as clear,

Thy heart avow,

For every gossip wind to hear ;

Tell me not now !

Tell me not now the tidings sweet,

The news divine ;

A little longer at thy feet

Leave me to pine.

I would not have the gadding bird

Hear from his bough ;

Nay, though I famish for a word,

Tell me not now !

The Yellow Book—Vol. III. B

But

But when deep trances of delight

All Nature seal ;

When round the world the arms of Night

Caressing steal ;

When rose to dreaming rose says, “Dear,

Dearest ;” and when

Heaven sighs her secret in Earth’s ear,

Ah, tell me then !

The Papers of Basil Fillimer

By H. D. Traill

MY name is Johnson, just plain John Johnson—nothing more

subtle

than that ; and my individuality is, as they say, “in a

concatenation

accordingly.” In other words, the character of my

intellect is exactly

what you would expect in a man of my name.

This was well known to my old

friend, schoolmate, and fellow-

student at Oxford, the late Basil Fillimer

; a man of the very

subtlest mind that I should think has ever housed

itself in human

body since the brain of the last mediæval schoolman ceased

to

“distinguish.” Yet Basil Fillimer must needs appoint me—me of

all men in the world—his literary

executor, and charge me with

the duty of making a selection from his

papers and preparing them

for publication. They include a series of ”

Analytic Studies,” a

diary extending over several years, and a

three-volume novel

turning on the question whether the hero before

marrying the

heroine was or was not bound to communicate to her the fact

that he had once unjustly suspected her mother of circulating

reports injurious to the reputation of his aunt.

Basil knew, I say—he must have known—that I was quite

unable

to follow him in these refined speculations. Hence I can

only suppose that

at the time when his will was drawn he had not

yet discovered my

psychological incompetence, and that after he

had

The Yellow Book—Vol. V. B

had made that discovery his somewhat sudden death prevented

him from

appointing some one of keener analytical acumen in my

place.

It would not be fair to the novel, in case it should ever be

published, to

give any specimens of it here ; it might discount the

reader’s interest in

the development of the plot. But this is the

sort of thing the diary

consists of:

“June 15.—Went yesterday to call on my aunt

Catherine and

found her more troubled than ever about the foundations of

her

faith. It is a singular phenomenon this awakening of doubt in

an

elderly mind—this ‘St. Martin’s summer’ of scepticism if I

may so

call it ; an intensely curious and at the same time a

painful study. For

me it has so potent a fascination, that I

never say or do anything, even

in what at the time seems to me

perfect good faith, to invite a

continuance of my aunt’s con-

fidences, without afterwards suspecting my

own motives. My

first inclination was to divert her mind to other

subjects. Why,

I asked myself, should an old lady of seventy-two who has

all her

life accepted the conventional religion without question be

encouraged to what the French call faire son âme at

this

extremely late hour of the day ? Still you can’t very well tell any

old lady, even though she is your aunt, that you think she is too

old to begin bothering herself with these high matters. You

have to put it

just the other way, and suggest that she has

probably many years of life

before her, and will have plenty of

time for such speculations later on.

But the first sentence I tried

to frame in this sense reminded me so

ludicrously of Mrs.

Quickly’s consolations of the dying Falstaff, that I

had to stop

for fear of laughing, and allow her to go on. For reply I put

her

off at the time with commonplaces, but she has since renewed the

conversation so often that I feel I shall be obliged to disclose

some

some of my own opinions, which are of course of a much

more advanced

scepticism than hers. I have considered the

question of disguising or

qualifying them, and have come

without doubt—or I think without

much doubt—to the con-

clusion that I am not justified in doing so.

I have never believed

in the morality of—

Leave thou thy sister, when she prays,

Her early Heaven, her happy views ;

Nor thou with shadowed hint confuse

A life that leads melodious days.

“Besides, there is no interpretation clause at the end of In

Memoriam to say that the term ‘sister’ shall include ‘maiden

aunt.’

Moreover, I have every reason to suspect that my aunt Catherine

has ceased to pray, and I am sure her days are anything but

‘melodious’ just now, poor old soul. It is all very well to respect

other

people’s religious illusions as long as they remain undisturbed

in the

minds of those who harbour them. So long the maxim

Wen Gott betrügt ist wohl betrogen undoubtedly

applies. But what

if the Divine Deceiver begins to lose his power of

deceiving ? Is

it the business of any of his creatures to come to his

assistance ?

“June 20.—I have just returned from an hour’s

interview with

my aunt, who almost immediately opened out on the question

of

her doubts. She spoke of them in tones of profound, indeed of

almost tragic agitation ; and I could not bring myself to say any-

thing

which would increase her mental anguish, as I thought might

happen if I

confessed to sharing them. I accordingly found

myself reverting after all

to the old commonplaces,—that ‘these

things were mysteries’ and so

forth (which of course is exactly the

trouble), and the rest of the

‘vacant chaff well meant for grain.’

It had a soothing effect at the time,

and I returned home well

pleased

pleased with my own wise humanity, as I thought it. But now

that I look

back upon it and examine my mixed motives, I am

forced to admit that there

was more of cowardice than compassion

in the amalgam. I was not even quite

sincere, I now find, in

pleading to myself my aunt’s distress of mind as

an excuse for the

concealment, or rather the misrepresentation, of my

opinions. I

knew at the time that she had had a bad night and that she is

suf-

fering severely just now from suppressed gout. In other words, I

was secretly conscious at the back of my mind that the abnormal

excess of her momentary sufferings was due to physical and not

mental

causes, and would yield readily enough to colchicum or

salicylic acid,

which no one has ever ranked among Christian

apologetics. Yet I persuaded

myself for the moment that it was

this quite exceptional and transitory

state of my aunt’s feelings

which compelled me to keep silence.

“June 23.—To-day I have had what

seems—or seemed to me, for

I have not yet had time for a thorough

analysis—a clear indication

of my only rational and legitimate

course. My aunt Catherine said

plainly to me this afternoon that as she

had gathered from our

conversations that my views were strictly orthodox,

she would not

pain me in future by any further disclosures of her own

doubts.

At the same time, she added, it was only right to tell me that my

pious advice had done her no good, but, on the contrary, harm, since

there was to her mind nothing so calculated to confirm scepticism

as the

sight of a man of good understanding thus firmly wedded

to certain

received opinions of which nevertheless he was unable to

offer any

reasonable defence or even intelligible explanation whatso-

ever. Upon

this hint I of course spoke. It was clear that if my

silence only

increased my aunt’s trouble, and that if, further, it

threatened to

convict me unjustly of stupidity, I was clearly

entitled, as well on

altruistic as on self-regarding grounds, to reveal

my

my true opinions. In fact, I thought at the time that I had never

acted

under the influence of a motive so clearly visible along its

whole course

from Thought to Will, and so manifestly free from

any the smallest fibre

of impulse having its origin in the subliminal

consciousness. Yet now I am

beginning to doubt.

“June 24.—On a closer examination I feel that

my motive was

not, as I then thought, compounded equally of a

legitimate desire

to vindicate my own intelligence and of a praiseworthy

anxiety not

to add to my aunt’s spiritual perplexities, but that it was

subtly

tainted with an illegitimate longing to continue my study of her

curious case. Consequently, I cannot now assure myself that if I

had

not known that further concealment of my opinions would

arrest my aunt’s

confidences and thus deprive me of a keen

psychological pleasure (which I

have no right to enjoy at her

expense) the legitimate inducements to

candour that were

presented to me would of themselves have prevailed.”

There is much more of the same kind ; but I will cut it short

at this

point, not only to escape a headache, but to ask any

impartial reader into

whose hands this apology may fall, whether,

I—who as I said before

am not only John Johnson by name but

by nature—am a fit and proper

person to edit the posthumous

papers of Basil Fillimer.

I come now, however, to what I consider my strongest justifi-

cation for

declining this literary trust. Though I had, and

indeed still retain, the

highest admiration for Basil Fillimer’s

intellectual subtlety, and though,

confessing myself absolutely

unable to follow him into his refinements of

analysis, I hazard

this opinion with diffidence, I do not think that,

except in their

curiosity as infinitely delicate and minute mental

processes, his

speculations are of any value to the world. I have formed

this

opinion in my rough-and-ready way from a variety of circum-

stances ;

stances ; but in support of it I rely mainly upon an incident

which

occurred within a few months of my lamented friend’s

death, and which

formed to the best of my knowledge the sole

passage of sentiment in his

intensely speculative career.

To say that he fell in love would be to employ a metaphor of

quite

inappropriate violence. He “shaded off” from a colourless

indifference to

a certain young woman of his acquaintance

through various neutral tints of

regard into a sort of pale sunset

glow of affection for her. Eleanor

Selden was a first cousin of

my own. We had seen much of each other from

childhood

upwards, and I knew—or thought I knew—her well.

She was a

lively, good-natured, commonplace girl, without a spark of

romance about her, and all a woman’s eye to the main chance. I

don’t mean

by this that she was more mercenary than most girls.

She merely took that

practical view of life and its material

requirements which has always

seemed to me (only I am not a

psychologist) to be so much more common

among young people

of what is supposed to be the sentimental sex, than of

the other.

I daresay she was not incapable of love—among

appropriate

surroundings. Unlike some women, she was not constitutionally

unfitted to appear with success in the matrimonial drama ; but

she

was particular about the mise-en-scène. “Act I., A

Cottage,”

would not have suited her at all. She would have played the

wife’s part with no spirit, I feel convinced. As to “Act V., A

Cottage,” with an “interval of twenty years supposed to elapse”

between

that and the preceding act, I doubt whether she would

ever have reached it

at all.

I imparted these views of mine as delicately as I could to my

accomplished

friend, but they produced no impression on him.

He told me kindly but

firmly that I was altogether mistaken.

He had, he said, made a

particularly careful study of Eleanor’s

character

character and had arrived at the confident conclusion that absolute

unselfishness formed its most distinctive feature. Nor was he at

all

shaken in this opinion by the fact that when a little later on

he informed

her of the nature of his sentiments towards her, he

found that she agreed

with him in thinking that his then income

was not enough to marry upon,

and that they had better wait

until the death of an uncle of his from whom

he had expectations.

I felt rather curious to know what passed at the

interview between

them, and questioned him on the subject.

“As to this objection on the ground of the insufficiency of

your income,

did it come from you,” I asked, “or from her ?”

“What a question,” said Basil, contemptuously. “From me

of course.”

“But at once?”

“How do you mean, at once ?”

“Well, was there any interval between your telling her you

loved her and

your adding that you did not think you were well

enough off to marry just

at present ?”

” Any interval ? No, of course not. It would have been

obviously unfair and

ungenerous on my part to have made her a

declaration of love without at

the same time adding that I could

not ask her to share my present poverty

and—”

“Oh,” I interrupted, “you said that at the same time, did you ?

Then she

had nothing to do but to agree ?”

“Well, no, of course not,” said Basil. “But, my dear fellow,”

he continued,

with his usual half-pitying smile, “you don’t see the

point. The point is,

that she agreed reluctantly—indeed with quite

obvious reluctance.”

” Did she press you to reconsider your decision ? ‘

” Well, no, she could hardly do that, you know. It would not

be quite

consistent with maidenly reserve and so forth. But

she

she again and again declared her perfect readiness to share my

present

fortunes.”

” Ah ! she did that, did she ? ”

” Yes, and even after she must have seen that my decision was

inflexible.”

” Oh ! even after that : but not before ? Thank you, I

think I

understand.”

And I thought I did, as also did Basil. But I fancy our read-

ing of the

incident was not the same.

A closer intimacy now followed between the two. They were

not engaged ;

Basil had been beforehand in insisting that her future

freedom of choice

should not be fettered, and she again ” reluctantly,

—indeed with

quite obvious reluctance,” had agreed. They were

much in each other’s

company, and Basil, who used to read her

some of the most intricate

psychological chapters in his novel, in

which she showed the greatest

interest, conceived a very high idea

of her intellectual gifts. “She has,”

he said, “by far the subtlest

mind for a woman that I ever came in contact

with.”

” Do you ever talk to her about your uncle ? ” I asked him one day.

” Oh yes, sometimes,” he replied. ” And, by the way,” he

added, suddenly, ”

that reminds me. To show you how unjust is

the view you take of your

cousin’s motives, as no doubt you do of

human nature generally like most

superficial students of it (excuse

an old friend’s frankness), I may tell

you that although there have

been many occasions when she might have put

the question with

perfect naturalness and propriety, she has never once

inquired the

amount of my uncle’s means.”

” It is very much to her credit,” said I.

” It is true,” he added, after a moment’s reflection and with a

half-laugh, ” I could not have told her if she had. His money is

all in

personalty, and he is a close old chap.”

“Oh,”

” Oh,” I said, ” have you ever by chance mentioned that to

her?”

” Eh ? What ? ” answered Basil, absently, for, as his manner

was, he was

drifting away on some underground stream of his own

thoughts. ” Mentioned

it ? I don’t recollect. I daresay I have.

Probably I must have done. Why

do you ask ? ”

“Well,” said I, ” because if she knew you could not answer the

question

that might account for her not asking it.”

But he was already lost in reverie, and I did not feel justified in

rousing

him from it for no worthier purpose than that of hinting

suspicion of the

disinterestedness of a blood relation.

In due time—or at least in what the survivors considered due

time,

though I don’t suppose the poor old gentleman so regarded

it—Basil’s uncle died, and the nephew found himself the heir to a

snug little fortune of about £,900 a year. As soon as he was in

possession

of it he wrote to Eleanor, acquainting her with the

change in his

circumstances, and renewing his declaration of love,

accompanied this time

with a proposal of immediate marriage. I

happened to look in upon him at

his chambers on the evening of

the day on which the letter had been

despatched, and he told me

what he had done.

” Ah ! ” said I, ” now, then, we shall see which of us is right.

But no,” I

added, on a moment’s reflection, “after all, it won’t

prove anything ; for

I suppose we both agree that she is likely to

accept you now, and I can’t

deny that she can do so with perfect

propriety.”

Basil looked at me as from a great height, a Gulliver conversing

with a

Lilliputian.

” Dear old Jack,” he said, after a few moments of obviously

amused

silence, ” you are really most interesting. What makes

you think she will

say Yes ? ”

” What ! ”

” What ! ” I exclaimed in astonishment. ” Don’t you think

so yourself ? ”

” On the contrary,” replied Basil, with that sad patient smile of

his, ” I

am perfectly convinced that she will say No.”

I did not pursue the conversation, for my surprise at his opinion

had by

this time disappeared. It occurred to me that after all it

was not

unnatural in a man who had conceived so exalted an

estimate of Eleanor’s

character. No doubt he thought her too

proud to incur the suspicion which

might attach to her motives in

accepting him after this accession to his

fortunes. I felt sure,

however, that he was mistaken, and it was therefore

with

renewed and much increased surprise that I read the letter which

he placed in my hand with quiet triumph a few days after-

wards.

It was a refusal. Eleanor thanked him for his renewal of his

proposal, said

she should always feel proud of having won the

affection of so

accomplished a man, but that having carefully

examined her own heart, she

felt that she did not love him enough

to marry him.

Basil, I feel sure, was as fond of my cousin as it was in his

nature to be

of anybody ; but he was evidently much less dis-

appointed by her

rejection than pleased with the verification of his

forecast. I confess I

was puzzled at its success.

” How did you know she would refuse you ? ” I asked. ” I

must say that

I thought her sufficiently alive to her own

interests

to accept you.”

Basil gently shook his head.

“But I suppose you thought that she would reject you

for fear

of being considered mercenary.”

Basil still continued to shake his head, but now with a pro-

vokingly

enigmatic smile.

” No ?

” No ? But confound it,” I cried, out of patience, ” there are

only these

two alternatives in every case of this kind.”

” My dear Jack,” said Basil, after a few moments’ contemplation

of me, ”

you have confounded it yourself. You are confusing act

with motive. It is

true there are only two possible replies to the

question I asked Miss

Selden ; but the series af alternating motives

for either answer is

infinite.”

” Infinite ? ” echoed I, aghast.

“Yes,” said Basil, dreamily. ” It is obviously infinite, though

the human

faculties in their present stage of development can only

follow a few

steps of it. Would you really care to know,” he con-

tinued kindly, after

a pause, ” the way in which I arrived at my

conclusion ? ”

” I should like it of all things,” I said.

” Then you had better just take a pencil and a sheet of paper,”

said Basil.

“You will excuse the suggestion, but to any one un-

familiar with these

trains of thought some aid of the kind is posi-

tively necessary. Now,

then, let us begin with the simplest case,

that of a girl of selfish

instincts and blunt sensibilities, who

looks out for as good a match, from

the pecuniary point of view,

as she can make, and doesn’t very much care

to conceal the

fact.”

(” Eleanor down to the ground,” I thought to myself.)

” She would have said Yes to my question, wouldn’t she ? ”

” No doubt.”

” Very well, then, kindly mark that Case A.”

I did so.

” Next, we come to a girl of a somewhat higher type, not per-

haps

indifferent to pecuniary considerations, but still too proud to

endure the

suspicion of having acted upon them in the matter of

marriage. She would

answer No, wouldn’t she ? ”

“Yes,”

” Yes,” said I, eagerly. ” And surely that is the way in which

you must explain Eleanor’s refusal.”

“Pardon me,” said Basil, raising a deprecating hand, “it is not

quite so

simple as that. But have you got that down? If so,

please mark it Case B. Thirdly, we get a woman of a nobler

nature who would have too much faith in her lover s generosity to

believe

him capable of suspecting her motives, and who would wel-

come the

opportunity of showing that faith. Have you got that

down ? ”

“Yes, every word,” said I. “But, my dear fellow, that is a

woman whose

answer would be Yes.”

“Exactly,” replied Basil, imperturbably. “Mark it Case

C.

And now,” he continued, lighting a cigarette, ” have the

goodness

to favour me with your particular attention to this. There is a

woman of moral sensibilities yet more refined who would fear lest

her lover should suspect her of being actuated by motives really

mercenary, but veiled under the pretence of a

desire to demonstrate

her reliance on his faith in her disinterestedness,

and who would

consequently answer No. Do you follow that ? ”

” No, I’ll be damned if I do ! ” I cried, throwing down the

pencil.

” Ah,” said Basil, sadly, ” I was afraid so. Nevertheless, for

convenience

of reference, mark it Case D. There are of course

numberless others ; the series, as I have said, is infinite. There

is Case E, that of the woman who rises superior to this last-men-

tioned

fear, and says Yes ; and there is Case F, that of the

woman who fears to

be suspected of only feigning such superiority,

and says No. But it is

probably unnecessary to carry the analysis

further. You believe that Miss

Selden’s refusal of me comes under

Case B ; I, on the other hand, from my

experience of the singular

subtlety and delicacy of her intellectual

operations, am persuaded

that

that it belongs to the D category. Her alleged excuse is, of course,

purely

conventional. Her plea that she is unable to love me,” he

added with an

indescribable smile, ” is, for instance, absurd. I will

let a couple of

months or so elapse, and shall then take steps to

ascertain from her

whether it was the motive of Case B or that of

Case D by which she has

been really actuated.”

The couple of months, alas ! were not destined to go by in

Basil’s

lifetime. Three weeks later my poor friend was carried off

by an attack of

pneumonia, and I was left with this unsolved pro-

blem of conduct on my

mind.

I was, however, determined to seek the solution of it, and the

first time I

met Eleanor I referred it to herself. I had taken the

precaution to bring

my written notes with me so as to be sure

that the question was correctly

stated.

” Nelly,” said I, for, as I have already said, we were not only

cousins,

but had been brought up together from childhood, ” I

want you to tell me,

your oldest chum, why you refused Basil

Fillimer. Was it because you were too proud to endure the

suspicion of

having married for money, or was it—now for

goodness’ sake don’t

interrupt me just here,” for I saw Nelly’s

smiling lips opening to speak ;

“or was it,” I continued, carefully

reading from my paper, ” because you

feared lest he should suspect

you of being actuated by motives really mercenary but veiled

under the pretence of a desire to demonstrate your reliance on

his

faith in your disinterestedness ? ”

The smile broke into a ringing laugh.

“Why, you stupid Jack,” cried Eleanor, “what nonsense of

poor dear old

Basil’s have you got into your head ? Why did I

refuse him ? You who have

known me all my life to ask such a

question ! Now did you—did you think I was the sort of girl to

marry a

man with only nine hundred a year ? ”

Candidly,

Candidly, I did not. But poor Basil did. And that, as I said

before, is one

and perhaps the strongest among many reasons why

I think that his studies

of human character and analyses of human

motive, though intellectually

interesting, would not be likely to

prove of much practical value to the

world.

Song

SHE’S somewhere in the sunlight strong,

Her tears are in the falling rain,

She calls me in the wind’s soft song,

And with the flowers she comes again ;

Yon bird is but her messenger,

The moon is but her silver car,

Yea ! sun and moon are sent by her,

And every wistful, waiting star.

The Pleasure-Pilgrim

By Ella D’Arcy

I

CAMPBELL was on his way to Schloss Altenau, for a second

quiet season with

his work. He had spent three profitable

months there a year ago, and now he

was devoutly hoping for a

repetition of that good fortune. His thoughts

outran the train ;

and long before his arrival at the Hamelin railway

station, he was

enjoying his welcome by the Ritterhausens, was revelling in

the

ease and comfort of the old castle, and was contrasting the

pleasures

of his home-coming—for he looked upon Schloss Altenau as a

sort

of temporary home—with his recent cheerless experiences of

lodging-houses in London, hotels in Berlin, and strange indifferent

faces

everywhere. He thought with especial satisfaction of the

Maynes, and of the

good talks Mayne and he would have together,

late at night, before the

great fire in the hall, after the rest of the

household had gone to bed. He

blessed the adverse circumstances

which had turned Schloss Altenau into a

boarding-house, and

had reduced the Freiherr Ritterhausen to eke out his

shrunken

revenues by the reception, as paying guests, of English and

American pleasure-pilgrims.

He rubbed the blurred window-pane with the fringed end of the

strap

strap hanging from it, and, in the snow-covered landscape reeling

towards

him, began to recognise objects that were familiar.

Hamelin could not be

far off….. In another ten minutes the

train came to a standstill.

He stepped down from the overheated atmosphere of his com-

partment into the

cold bright February afternoon, and through

the open station doors saw one

of the Ritterhausen carriages

awaiting him, with Gottlieb in his

second-best livery on the

box. Gottlieb showed every reasonable

consideration for the

Baron’s boarders, but he had various methods of

marking his sense of

the immense abyss separating them from the family. The

use of

his second-best livery was one of these methods. Nevertheless,

he

turned a friendly German eye up to Campbell, and in response

to his

cordial ” Guten Tag, Gottlieb. Wie geht’s ? Und die

Herrschaften ? ”

expressed his pleasure at seeing the young man

back again.

While Campbell stood at the top of the steps that led down to

the carriage

and the Platz, looking after the collection of his

luggage and its bestowal

by Gottlieb’s side, he became aware of

two persons, ladies, advancing

towards him from the direction of

the Wartsaal. It was surprising to see

any one at any time in

Hamelin station. It was still more surprising when

one of these

ladies addressed him by name.

“You are Mr. Campbell, are you not?” she said. “We

have been waiting for you

to go back in the carriage together.

When we found this morning that there

was only half-an-hour

between your train and ours, I told the Baroness it

would be

perfectly absurd to send to the station twice. I hope you

won’t

mind our company ? ”

The first impression Campbell received was of the magnificent

apparel of the

lady before him ; it would have been noticeable in

Paris

The Yellow Book—Vol. V. c

Paris or Vienna—it was extravagant here. Next, he perceived

that the

face beneath the upstanding feathers and the curving hat-

brim was that of

so very young a girl as to make the furs and

velvets seem more incongruous

still. But the incongruity vanished

with the intonation of her first

phrase, which told him she was an

American. He had no standards for

American dress or manners.

It was clear that the speaker and her companion

were inmates of

the Schloss.

Campbell bowed, and murmured the pleasure he did not feel.

A true Briton, he

was intolerably shy; and his heart sank at the

prospect of a three-mile

drive with two strangers who evidently

had the advantage of knowing all

about him, while he was in

ignorance of their very names. As he took his

place opposite to

them in the carriage, he unconsciously assumed a cold

blank stare,

pulling nervously at his moustache, as was his habit in

moments

of discomposure. Had his companions been British also, the

ordeal of the drive would certainly have been a terrible one ; but

these

young American girls showed no sense of embarrassment

whatever.

“We’ve just come back from Hanover,” said the one who had

already spoken to

him. “I go over once a week for a singing

lesson, and my little sister

comes along to take care of me.”

She turned a narrow, smiling glance from Campbell to her

little sister, and

then back to Campbell again. She had red hair,

freckles on her nose, and

the most singular eyes he had ever seen ;

slit-like eyes, set obliquely in

her head, Chinese fashion.

” Yes, Lulie requires a great deal of taking care of,” assented

the little

sister, sedately, though the way in which she said it

seemed to imply

something less simple than the words themselves.

The speaker bore no

resemblance to Lulie. She was smaller,

thinner, paler. Her features were

straight, a trifle peaked ; her

skin

skin sallow ; her hair of a nondescript brown. She was much

less gorgeously

dressed. There was even a suggestion of shabbi-

ness in her attire, though

sundry isolated details of it were hand-

some too. She was also much less

young ; or so, at any rate,

Campbell began by pronouncing her. Yet

presently he wavered.

She had a face that defied you to fix her age.

Campbell never

fixed it to his own satisfaction, but veered in the course

of that drive

(as he was destined to do during the next few weeks) from

point

to point up and down the scale between eighteen and thirty-five.

She wore a spotted veil, and beneath it a pince-nez, the lenses of

which

did something to temper the immense amount of humorous

meaning which lurked

in her gaze. When her pale prominent

eyes met Campbell’s, it seemed to the

young man that they were

full of eagerness to add something at his expense

to the stores of

information they had already garnered up. They chilled

him

with misgivings ; there was more comfort to be found in her

sister’s shifting red-brown glances.

” Hanover is a long way to go for lessons,” he observed, forcing

himself to

be conversational. ” I used to go myself about once a

week, when I first

came to Schloss Altenau, for tobacco, or note-

paper, or to get my hair

cut. But later on I did without, or

contented myself with what Hamelin, or

even the village, could

offer me.”

” Nannie and I,” said the young girl, ” meant to stay only a

week at

Altenau, on our way to Hanover, where we were going

to pass the winter ;

but the Castle is just too lovely for any-

thing,” she added softly. She

raised her eyelids the least little bit

as she looked at him, and such a

warm and friendly gaze shot out

that Campbell was suddenly thrilled. Was

she pretty, after all ?

He glanced at Nannie ; she, at least, was

indubitably plain. ” It’s

the very first time we’ve ever stayed in a

castle,” Lulie went on ;

“and

” and we’re going to remain right along now, until we go home

in the spring.

Just imagine living in a house with a real moat,

and a drawbridge, and a

Rittersaal, and suits of armour that have

been actually worn in battle !

And oh, that delightful iron collar

and chain ! You remember it, Mr.

Campbell ? It hangs right

close to the gateway on the court-yard side. And

you know, in

old days, the Ritterhausens used it for the punishment of

their

serfs. There are horrible stories connected with it. Mr. Mayne

can tell you them. But just think of being chained up there like

a dog ! So

wonderfully picturesque.”

” For the spectator perhaps,” said Campbell, smiling. ” I

doubt if the

victim appreciated the picturesque aspect of the

case.”

With this Lulie disagreed. ” Oh, I think he must have been

interested,” she

said. ” It must have made him feel so absolutely

part and parcel of the

Middle Ages. I persuaded Mr. Mayne to

fix the collar round my neck the

other day ; and though it was

very uncomfortable, and I had to stand on

tiptoe, it seemed to me

that all at once the court-yard was filled with

knights in armour,

and crusaders, and palmers, and things ; and there were

flags flying

and trumpets sounding ; and all the dead and gone

Ritterhausens

had come down from their picture-frames, and were

walking

about in brocaded gowns and lace ruffles.”

” It seemed to require a good deal of persuasion to get Mr.

Mayne to unfix

the collar again,” said the little sister. ” How at

last did you manage it

? ”

But Lulie replied irrelevantly : ” And the Ritterhausens are

such perfectly

lovely people, aren’t they, Mr. Campbell ? The

old Baron is a perfect dear.

He has such a grand manner. When

he kisses my hand I feel nothing less than

a princess. And the

Baroness is such a funny, busy, delicious little round

ball of a

thing.

thing. And she’s always playing bagatelle, isn’t she ? Or else

cutting up

skeins of wool for carpet-making.” She meditated a

moment. “Some people

always are cutting things up in order to

join

them together again,” she announced, in her fresh drawling

little

voice.

” And some people cut things up, and leave other people to do

all the

reparation,” commented the little sister, enigmatically.

And all this time the carriage had been rattling over the

cobble-paved

streets of the quaint mediæval town, where the

houses stand so near

together that you may shake hands with

your opposite neighbour ; where

allegorical figures, strange birds

and beasts, are carved and painted over

the windows and doors ;

and where to every distant sound you lean your ear

to catch the

fairy music of the Pied Piper, and at every street corner you

look

to see his tatterdemalion form with the frolicking children at

his

heels.

Then the Weser bridge was crossed, beneath which the ice-

floes jostled and

ground themselves together, as they forced a way

down the river ; and the

carriage was rolling smoothly along

country roads, between vacant

snow-decked fields.

Campbell’s embarrassment was wearing off. Now that he was

getting accustomed

to the girls, he found neither of them awe-

inspiring. The red-haired one

had a simple child-like manner

that was charming. Her strange little face,

with its piquant

irregularity of line, its warmth of colour, began to

please him.

What though her hair was red, the uncurled wisp which

strayed

across her white forehead was soft and alluring ; he could see

soft

masses of it tucked up beneath her hat-brim as she turned her

head. When she suddenly lifted her red-brown lashes, those

queer eyes of

hers had a velvety softness too. Decidedly, she

struck him as being

pretty—in a peculiar way. He felt an

immense

immense accession of interest in her. It seemed to him that he

was the

discoverer of her possibilities. He did not doubt that the

rest of the

world called her plain, or at least odd-looking. He, at

first, had only

seen the freckles on her nose, her oblique-set eyes.

He wondered what she

thought of herself, and how she appeared

to Nannie. Probably as a very

commonplace little girl ; sisters

stand too close to see each other’s

qualities. She was too young

to have had much opportunity of hearing

flattering truths from

strangers ; and, besides, the ordinary stranger

would see nothing

in her to call for flattering truths. Her charm was

something

subtle, out-of-the-common, in defiance of all known rules of

beauty.

Campbell saw superiority in himself for recognising it, for

formu-

lating it ; and he was not displeased to be aware that it

would,

always remain caviare to the multitude.

II

” I’m jolly glad to have you back,” Mayne said, that same

evening, when, the

rest of the boarders having retired to their

rooms, he and Campbell were

lingering over the hall-fire for a

talk and smoke. ” I’ve missed you

awfully, old chap, and the

good times we used to have here. I’ve often

meant to write to

you, but you know how one shoves off letter-writing day

after

day, till at last one is too ashamed of one’s indolence to write

at

all. But tell me—you had a pleasant drive from Hamelin ?

What do you think of our young ladies ? ”

“Those American girls? But they’re charming,” said Campbell,

with

enthusiasm. ” The red-haired one is particularly charming.”

At this Mayne laughed so oddly that Campbell questioned him

in surprise. ”

Isn’t she charming ? “

“My

” My dear chap,” said Mayne, ” the red-haired one, as you call

her, is the

most remarkably charming young person I’ve ever met

or read of. We’ve had a

good many American girls here before

now—you remember the good old

Clamp family, of course ?—

they were here in your time, I think

?—but we’ve never had any-

thing like this Miss Lulie Thayer. She is

something altogether

unique.”

Campbell was struck with the name. ” Lulie— Lulie Thayer,”

he

repeated. ” How pretty it is.” And, full of his great discovery,

he felt he

must confide it to Mayne, at least. ” Do you know,”

he went on, ” she is really very pretty too ? I didn’t think so

at

first, but after a bit I discovered that she is positively quite

pretty

—in an odd sort of way.”

Mayne laughed again. ” Pretty, pretty ! ” he echoed in

derision. ” Why,

lieber Gott im Himmel, where are your eyes ?

Pretty ! The girl is beautiful, gorgeously beautiful ; every trait,

every

tint, is in complete, in absolute harmony with the whole.

But the truth is,

of course, we’ve all grown accustomed to the

obvious, the commonplace ; to

violent contrasts ; blue eyes, black

eyebrows, yellow hair ; the things

that shout for recognition.

You speak of Miss Thayer’s hair as red. What

other colour

would you have, with that warm creamy skin ? And then,

what

a red it is ! It looks as though it had been steeped in red

wine.”

” Ah, what a good description,” said Campbell, appreciatively.

” That’s just

it—steeped in red wine.”

“And yet it’s not so much her beauty,” Mayne continued.

” After all, one has

met beautiful women before now. It’s her

wonderful generosity, her

complaisance. She doesn’t keep her

good things to herself. She doesn’t

condemn you to admire from

a distance.”

“How

” How do you mean ? ” Campbell asked, surprised again.

“Why, she’s the most egregious little flirt I’ve ever met.

And yet, she’s

not exactly a flirt, either. I mean she doesn’t flirt

in the ordinary way.

She doesn’t talk much, or laugh, or appar-

ently make the least claims on

masculine attention. And so all

the women like her. I don’t believe there’s

one, except my wife,

who has an inkling as to her true character. The

Baroness, as

you know, never observes anything. Seigneur Dieu ! if she knew

the things I could tell her about

Miss Lulie ! For I’ve had

opportunities of studying her. You see, I’m a

married man, and

not in my first youth ; out of the running altogether.

The

looker-on gets the best view of the game. But you, who are

young

and charming and already famous—we’ve had your book

here, by the

bye, and there’s good stuff in it—you’re going to

have no end of

pleasant experiences. I can see she means to add

you to her ninety-and-nine

other spoils ; I saw it from the way

she looked at you at dinner. She

always begins with those

velvety red-brown glances. She began that way with

March and

Prendergast and Willie Anson, and all the men we’ve had here

since her arrival. The next thing she’ll do will be to press your

hand

under the tablecloth.”

” Oh, come, Mayne ; you’re joking,” cried Campbell, a little

brusquely. He

thought such jokes in bad taste. He had a high

ideal of Woman, an immense

respect for her ; he could not endure

to hear her belittled even in jest.

“Miss Thayer is refined and

charming. No girl of her class would do such

things.”

” What is her class ? Who knows anything about her ? All

we know is that she

and her uncanny little friend—her little

sister, as she calls her,

though they’re no more sisters than you

and I are—they’re not even

related—all we know is that she

and Miss Dodge (that’s the little

sister’s name) arrived here

one

one memorable day last October from the Kronprinz Hotel at

Waldeck-Pyrmont.

By the bye, it was the Clamps, I believe,

who told her of the

Castle—hotel acquaintances—you know how

travelling Americans

always cotton to each other. And we’ve

picked up a few little biographical

notes from her and Miss Dodge

since. Zum

Beispiel, she’s got a rich father somewhere away back

in

Michigan, who supplies her with all the money she wants.

And she’s been

travelling about since last May : Paris, Vienna,

the Rhine, Düsseldorf, and

so on here. She must have had some

rich experiences, by Jove. For she’s

done everything. Cycled in

Paris : you should see her in her cycling

costume ; she wears it

when the Baron takes her out shooting—she’s

an admirable shot,

by the way, an accomplishment learned, I suppose, from

some

American cow-boy. Then in Berlin she did a month’s hospital

nursing ; and now she’s studying the higher branches of the

Terpsichorean

art. You know she was in Hanover to-day. Did

she tell you what she went for

? ”

” To take a singing lesson,” said Campbell, remembering the

reason she had

given.

” A singing lesson ! Do you sing with your legs ? A dancing

lesson, mein lieber. A dancing lesson from the ballet-master of

the

Hof Theater. She could deposit a kiss on your forehead with her

foot, I don’t doubt. I wonder if she can do the grand

écart yet.”

And when Campbell, in astonishment, wondered why on

earth she

should wish to do such things, ” Oh, to extend her

opportunities,”

Mayne explained, “and to acquire fresh sensations. She’s

an

adventuress. Yes, an adventuress, but an end-of-the-century one.

She doesn’t travel for profit, but for pleasure. She has no desire to

swindle her neighbour of dollars, but to amuse herself at his expense.

And

she’s clever ; she’s read a good deal ; she knows how to apply

her reading

to practical life. Thus, she’s learned from Herrick

not

not to be coy ; and from Shakespeare that sweet-and-twenty is the

time for

kissing and being kissed. She honours her masters in the

observance. She

was not in the least abashed when, one day, I

suddenly came upon her

teaching that damned idiot, young Anson,

two new ways of kissing.”

Campbell’s impressions of the girl were readjusting themselves

completely,

but for the moment he was unconscious of the change.

He only knew that he

was partly angry, partly incredulous, and

inclined to believe that Mayne

was chaffing him.

” But Miss Dodge,” he objected, ” the little sister, she is older ;

old

enough to look after her friend. Surely she could not allow

a young girl

placed in her charge to behave in such a way—”

” Oh, that little Dodge girl,” said Mayne contemptuously ;

” Miss Thayer

pays the whole shot, I understand, and Miss Dodge

plays gooseberry,

sheep-dog, jackal, what you will. She finds her

reward in the other’s

cast-off finery. The silk blouse she was wear-

ing to-night, I’ve good

reason for remembering, belonged to Miss

Lulie. For, during a brief season,

I must tell you, my young lady

had the caprice to show attentions to your

humble servant. I suppose

my being a married man lent me a factitious

fascination. But I didn’t

see it. That kind of girl doesn’t appeal to me.

So she employed Miss

Dodge to do a little active canvassing. It was really

too funny ;

I was coming in one day after a walk in the woods ; my wife

was

trimming bonnets, or had neuralgia, or something. Anyhow, I

was

alone, and Miss Dodge contrived to waylay me in the middle

of the

court-yard. ‘Don’t you find it vurry dull walking all by

yourself ?’ she

asked me ; and then blinking up in her strange

little short-sighted

way—she’s really the weirdest little creature—

‘Why don’t you

make love to Lulie ?’ she said ; ‘you’d find her

vurry charming.’ It took

me a minute or two to recover presence

of mind enough to ask her whether

Miss Thayer had commissioned

her

her to tell me so. She looked at me with that cryptic smile of hers ;

‘She’d

like you to do so, I’m sure,’ she finally remarked, and

pirouetted away.

Though it didn’t come off, owing to my bash-

fulness, it was then that Miss

Dodge appropriated the silk bodice ;

and Providence, taking pity on Miss

Thayer’s forced inactivity,

sent along March, a young fellow reading for

the army, with

whom she had great doings. She fooled him to the top of his

bent;

sat on his knee ; gave him a lock of her hair, which, having no

scissors handy, she burned off with a cigarette taken from his

mouth ; and

got him to offer her marriage. Then she turned

round and laughed in his

face, and took up with a Dr. Weber, a

cousin of the Baron’s, under the

other man’s very eyes. You

never saw anything like the unblushing coolness

with which she

would permit March to catch her in Weber’s arms.”

” Come,” Campbell protested, “aren’t you drawing it rather

strong ? ”

“On the contrary, I’m drawing it mild, as you’ll discover pre-

sently for

yourself; and then you’ll thank me for forewarning you.

For she makes

love—desperate love, mind you—to every man she

meets. And

goodness knows how many she hasn’t met, in the

course of her career, which

began presumably at the age of ten,

in some ‘Amur’can’ hotel or

watering-place. Look at this.”

Mayne fetched an alpenstock from a corner of

the hall ; it was

decorated with a long succession of names, which,

ribbon-like, were

twisted round and round it, carved in the wood. ” Read

them,”

insisted Mayne, putting the stick in Campbell’s hands. “You’ll

see they’re not the names of the peaks she has climbed, or the

towns she

has passed through ; they’re the names of the men she

has fooled. And

there’s room for more ; there’s still a good deal

of space, as you see.

There’s room for yours.”

Campbell glanced down the alpenstock—reading here a name,

there

there an initial, or just a date—and jerked it impatiently from him

on to a couch. He wished with all his heart that Mayne would stop,

would

talk of something else, would let him get away. The

young girl had

interested him so much ; he had felt himself so

drawn towards her ; he had

thought her so fresh, so innocent. But

Mayne, on the contrary, was warming

to his subject, was enchanted

to have some one to listen to his stories, to

discuss his theories, to

share his cynical amusement.

” I don’t think, mind you,” he said, ” that she is a bit interested

herself

in the men she flirts with. I don’t think she gets any of

the usual

sensations from it, you know. I think she just does it

for devilry, for a

laugh. Sometimes I wonder whether she does it

with an idea of retribution.

Perhaps some woman she was fond

of, perhaps her mother even—who

knows ?—was badly treated at

the hands of a man. Perhaps this girl

has constituted herself the

Nemesis for her sex, and goes about seeing how

many masculine

hearts she can break by way of revenge. Or can it be that

she is

simply the newest development of the New Woman—she who

in

England preaches and bores you, and in America practises and

pleases ? Yes, I believe she’s the American edition, and so new

that she

hasn’t yet found her way into fiction. She’s the pioneer

of the army coming

out of the West, that’s going to destroy the

existing scheme of things and

rebuild it nearer to the heart’s

desire.”

” Oh, damn it all, Mayne,” cried Campbell, rising abruptly,

“why not say at

once that she’s a wanton, and have done with it ?

Who wants to hear your

rotten theories ? ” And he lighted his

candle without another word, and

went off to bed.

It

III

It was four o’clock, and the Baron’s boarders were drinking

their afternoon

coffee, drawn up in a circle round the hall fire.

All but Campbell, who had

carried his cup away to a side-table,

and, with a book open before him,

appeared to be reading assidu-

ously. In reality he could not follow a line

of what he read ; he

could not keep his thoughts from Miss Thayer. What

Mayne

had told him was germinating in his mind. Knowing his friend

as

he did, he could not on reflection doubt his word. In spite of

much

superficial cynicism, Mayne was incapable of speaking

lightly of any young

girl without good cause. It now seemed

to Campbell that, instead of

exaggerating the case, Mayne had

probably understated it. The girl repelled

him to-day as much

as she had charmed him yesterday. He asked himself with

horror,

what had she not already known, seen, permitted ? When now

and

again his eyes travelled over, perforce, to where she sat, her red

head

leaning against Miss Dodge’s knee, seeming to attract and

concentrate all

the glow of the fire, his forehead set itself in

frowns, and he returned

with an increased sense of irritation to his

book.

” I’m just sizzling up, Nannie,” Miss Thayer presently com-

plained, in her

child-like, drawling little way ; ” this fire is too hot

for anything.” She

rose and shook straight her loose tea-gown,

a marvellous garment created in

Paris, which would have accused

a duchess of wilful extravagance. She stood

smiling round a

moment, pulling on and off with her right hand the big

diamond

ring which decorated the left. At the sound of her voice

Campbell had looked up ; now his cold unfriendly eyes en-

countered

countered hers. He glanced rapidly past her, then back to his

book. But she,

undeterred, with a charming sinuous movement

and a frou-frou of trailing

silks, crossed over towards him. She

slipped into an empty chair next

his.

” I’m going to do you the honour of sitting beside you, Mr.

Campbell,” she

said sweetly.

” It’s an honour I’ve done nothing whatever to merit,” he

answered, without

looking at her, and turned a page.

” The right retort,” she approved ; ” but you might have said

it a little

more cordially.”

“I don’t feel cordial.”

” But why not ? What has happened ? Yesterday you were

so nice.”

” Ah, a good deal of water has run under the bridge since

yesterday.”

” But still the river remains as full,” she told him, smiling,

” and still

the sky is as blue. The thermometer has even risen

six degrees.

Out-of-doors, to-day, I could feel the spring-time

in the air. You, too,

love the spring, don’t you ? I know that

from your books. And I wanted to

tell you, I think your books

perfectly lovely. I know them, most all. I’ve

read them away

home. They’re very much thought of in America. Only

last

night I was saying to Nannie how glad I am to have met you,

for I

think we’re going to be great friends ; aren’t we, Mr.

Campbell ? At least,

I hope so, for you can do me so much

good, if you will. Your books always

make me feel real good ;

but you yourself can help me much more.”

She looked up at him with one of her warm, narrow red-

brown glances, which

yesterday would have thrilled his blood, and

to-day merely stirred it to

anger.

“You over-estimate my abilities,” he said coldly ; “and on the

whole,

whole, I fear you will find writers a very disappointing race.

You see, they

put their best into their books. So, not to dis-

illusion you too rapidly

“—he rose—” will you excuse me ? I

have some work to do.” And

he left her sitting there alone.

But he did no work when he got to his room. Whether

Lulie Thayer was

actually present or not, it seemed that her

influence was equally

disturbing to him. His mind was full of

her : of her singular eyes, her

quaint intonation, her sweet

seductive praise. Yesterday such praise would

have been delight-

ful to him : what young author is proof against

appreciation of

his books ? To-day, Campbell simply told himself that she

laid

the butter on too thick ; that it was in some analogous manner

she had flattered up March, Anson, and all the rest of the men

that Mayne

had spoken of. He supposed it was the first step in

the process by which he

was to be fooled, twisted round her

finger, added to the list of victims

who strewed her conquering

path. He had a special fear of being fooled. For

beneath a

somewhat supercilious exterior, the dominant note of his

character

was timidity, distrust of his own merits ; and he knew he

was

single-minded—one-idea’d almost ; if he were to let himself go,

to

get to care very much for a woman, for such a girl as this girl,

for instance, he would lose himself completely, be at her mercy

absolutely.

Fortunately, Mayne had let him know her character :

he could feel nothing

but dislike for her—disgust, even ; and yet

he was conscious how

pleasant it would be to believe in her

innocence, in her candour. For she

was so adorably pretty :

her flower-like beauty grew upon him ; her head,

drooping a

little on one side when she looked up, was so like a flower

bent

by its own weight. The texture of her cheeks, her lips, were

delicious as the petals of a flower. He found he could recall with

perfect

accuracy every detail of her appearance : the manner in

which

which the red hair grew round her temples ; how it was loosely

and

gracefully fastened up behind with just a single tortoise-shell

pin. He

recalled the suspicion of a dimple which shadowed

itself in her cheek when

she spoke, and deepened into a delicious

reality every time she smiled. He

remembered her throat ; her

hands, of a beautiful whiteness, with pink

palms and pointed

fingers. It was impossible to write. He speculated long

on the

ring she wore on her engaged finger. He mentioned this ring to

Mayne the next time he saw him.

” Engaged ? very much so I should say. Has got a fiancé in

every capital of Europe probably. But the ring-man is

the fiancé

en titre. He writes to her by every

mail, and is tremendously in

love with her. She shows me his letters. When

she’s had her

fling, I suppose, she’ll go back and marry him. That’s

what

these little American girls do, I’m told ; sow their wild oats

here

with us, and settle down into bonnes

ménagères over yonder.

Meanwhile, are you having any fun with

her ? Aha, she presses

your hand ? The ‘gesegnete Mahlzeit’ business after

dinner is an

excellent institution, isn’t it ? She’ll tell you how much

she

loves you soon ; that’s the next move in the game.”

But so far she had done none of these things, for Campbell

gave her no

opportunities. He was guarded in the extreme,

ungenial ; avoiding her even

at the cost of civility. Sometimes

he was downright rude. That especially

occurred when he felt

himself inclined to yield to her advances. For she

made him all

sorts of silent advances, speaking with her eyes, her sad

little

mouth, her beseeching attitude. And then one evening she went

further still. It occurred after dinner in the little green drawing-

room.

The rest of the company were gathered together in the

big drawing-room

beyond. The small room has deep embrasures

to the windows. Each embrasure

holds two old faded green

velvet

velvet sofas in black oaken frames, and an oaken oblong table

stands between

them. Campbell had flung himself down on one

of these sofas in the corner

nearest the window. Miss Thayer,

passing through the room, saw him, and sat

down opposite.

She leaned her elbows on the table, the laces of her

sleeves

falling away from her round white arms, and clasped her

hands.

“Mr. Campbell, tell me what have I done? How have I

vexed you ? You have

hardly spoken two words to me all day.

You always try to avoid me.” And

when he began to utter

evasive banalities, she stopped him with an

imploring ” Don’t ! I

love you. You know I love you. I love you so much I

can’t

bear you to put me off with mere phrases.”

Campbell admired the well-simulated passion in her voice,

remembered Mayne’s

prediction, and laughed aloud.

” Oh, you may laugh,” she said, ” but I am serious. I love

you, I love you

with my whole soul.” She slipped round the end

of the table, and came close

beside him. His first impulse was to

rise ; then he resigned himself to

stay. But it was not so much

resignation that was required, as

self-mastery, cool-headedness.

Her close proximity, her fragrance, those

wonderful eyes raised so

beseechingly to his, made his heart beat.

” Why are you so cold ? ” she said. ” I love you so ; can’t you

love me a

little too ? ”

“My dear young lady,” said Campbell, gently repelling her,

” what do you

take me for ? A foolish boy like your friends

Anson and March ? What you

are saying is monstrous, pre-

posterous. Ten days ago you’d never even seen

me.”

” What has length of time to do with it ? ” she said. ” I loved

you at first

sight.”

” I wonder,” he observed judicially, and again gently removed

her

The Yellow Book—Vol. V. D

her hand from his, ” to how many men you have not already said

the same

thing.”

“I’ve never meant it before,” she said quite earnestly, and

nestled closer

to him, and kissed the breast of his coat, and held

her mouth up towards

his. But he kept his chin resolutely high,

and looked over her head.

” How many men have you not already kissed, even since you’ve

been here ?

”

“But there’ve not been many here to kiss!” she exclaimed

naïvely.

” Well, there was March ; you kissed him ? “

” No, I’m quite sure I didn’t.”

” And young Anson ; what about him ? Ah, you don’t

answer ! And then the

other fellow—what’s his name—Pren-

dergast—you’ve

kissed him ? ”

“But, after all, what is there in a kiss ? ” she cried ingenuously.

” It

means nothing, absolutely nothing. Why, one has to kiss all

sorts of people

one doesn’t care about.”

Campbell remembered how Mayne had said she had probably

known strange kisses

since the age of ten ; and a wave of anger

with her, of righteous

indignation, rose within him.

” To me,” said he, ” to all right-thinking people, a young girl’s

kisses are

something pure, something sacred, not to be offered in-

discriminately to

every fellow she meets. Ah, you don’t know

what you have lost ! You have

seen a fruit that has been

handled, that has lost its bloom ? You have seen

primroses,

spring flowers gathered and thrown away in the dust ? And

who

enjoys the one, or picks up the others ? And this is what you

remind me of—only you have deliberately, of your own perverse

will,

tarnished your beauty, and thrown away all the modesty,

the reticence, the

delicacy, which make a young girl so infinitely

dear.

dear. You revolt me, you disgust me. I want nothing from you,

but to be let

alone. Kindly take your hands away, and let me go.”

He roughly shook her off and got up, then felt a moment’s

curiosity to see

how she would take the repulse.

Miss Thayer never blushed : had never, he imagined, in her

life done so. No

faintest trace of colour now stained the

warm pallor of her rose-leaf skin

; but her eyes filled up with

tears ; two drops gathered on the

under-lashes, grew large,

trembled an instant, and then rolled unchecked

down her cheeks.

Those tears somehow put him in the wrong, and he felt he

had

behaved brutally to her for the rest of the night.

He began to find excuses for her : after all, she meant no

harm : it was her

up-bringing, her genre : it was a genre he

loathed ; but perhaps he need not have spoken so

harshly to her.

He thought he would find a more friendly word for her

next

morning ; and he loitered about the Mahlsaal, where the boarders

come in to breakfast as in an hotel, just when it suits them, till

past

eleven ; but the girl never turned up. Then, when he

was almost tired of