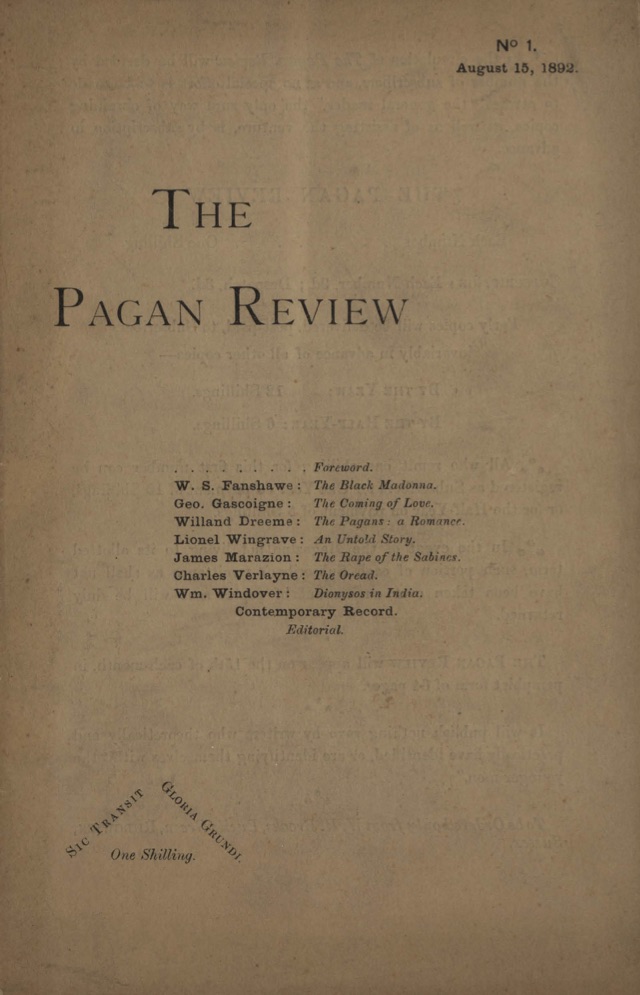

THE PAGAN REVIEW

No. 1

August 15, 1892

THE

PAGAN REVIEW

Subscription Information . . .

[ii-iii]

The Editor: Foreword . . . 1

W.S. Fanshawe: The Black Madonna . . . 5

Geo. Gascoigne: The Coming of Love . . . 19

Willand Dreeme: The Pagans: a Romance . . . 20

Lionel Wingrave: An Untold Story . . . 29

James Marazion: The Rape of the Sabines . . . 30

Charles Verlayne: The Oread . . . 41

Wm. Windover: Dionysos in India . . . 48

S: Pastels in Prose [Review of Book by

Stuart Merrill] . . . 54

W. H. B[rooks]: Contemporary Record

[Reviews of new books and plays] . . . 59

W. H. Brooks, Assistant Editor:

The Pagan Review [Editorial] . . . 5

Advertisements . . . 65

SIC TRANSIT

GLORIA GRUNDI.

One Shilling.

* As the circulation of The Pagan Review will be decided

by

the number of subscribers, and as no special effort is to be made

to

attract “the general reader,” the only sure way of obtaining

copies, as well as

of assisting the venture, is by subscription in

advance.

THE PAGAN REVIEW

Each number . . . . . . . . One Shilling.

SUBSCRIPTION: Each number, 9d. ; Despatch, 3d.

Early

copies will be delivered, post-paid to Subscribers

invariably in advance

of all other copies—

BY THE

YEAR: 12 Shillings.

BY THE HALF-YEAR: 6 Shillings.

⁂ All who remit one shilling for this first number can be

registered as

Subscribers for One Year on payment of 10 Shillings,

or for the Half-Year on

payment of 5 Shillings.

⁂ In the event of the Magazine not living to its allotted

term, such

portion of each Subscriber’s remittance as shall not

have been taken over on

account of copies sent will be duly

returned.

⁂

THE PAGAN REVIEW will appear on the 15th of each month, in

pamphlet form of 64 pages.

⁂

It will publish nothing save by writers who theoretically

and

practically have identified, or are identifying themselves with “the

younger men.”

⁂

To be Ordered only from W.H. Brooks, Buck’s Green, RUDGWICK,

Sussex.

* If filled up, please send to address as below.

THE PAGAN REVIEW.

(Subscription Form.)

Name in Full: ________________________________________

Permanent Address: ___________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

For One Year _________________________________

For Six Months _______________________________

* If subscription be sent herewith, fill

in amount and initial

here ( ____________________ )

[If no wish to the contrary be expressed, any subscription remitted—

unless

remittance for current number be sent separately—will be understood

to include

this number: thus, a subscription for one year will be from and

inclusive of No.

I. (See Editorial Notes at end of current number.]

SUGGESTIONS.

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

⁂ALL COMMUNICATIONS TO BE ADDRESSED TO THE ASSISTANT EDITOR:—

MR. W.H. BROOKS,

BUCK’S

GREEN, RUDGWICK, SUSSEX.

FOREWORD.

Editorial prefaces to new magazines

generally lay

great stress on the effort of the directorate, and

all

concerned, to make the forthcoming periodical

popular.

We have no such expectation: not even, it may be

added, any such intention. We aim at thorough-going

unpopularity: and

ther is every reason to believe

that, with the blessed who expect

little, we shall not be

disappointed.

⁂

In the first place, THE PAGAN REVIEW is frankly

pagan: pagan in sentiment, pagan in

convictions,

pagan in outlook. This being so, it is a magazine

only for those who, with Mr. George Meredith, can ex-

claim in all

sincerity—

“O sir, the truth, the truth! is’t in the skies,

Or in the grass, or in this heart of ours?

But O, the truth, the truth! . . . . “—

and at the same time, and with the same author, are

not

unready to admit that truth to life, external and

internal, very

often

“. . . . . . is not meat

For little people or for fools.”

To quote from Mr. Meredith once more:

“. . . . . these things are life:

And life, they say, is worthy of the Muse.”

But we are well aware that this is just what “they”

don’t

say. “They”, “the general public”, care very

little about the “Muse” at

all; and the one thing they

never advocate of wish is that the “Muse”

should be so

indiscreet as to really withdraw from life the approved

veils of Convention.

Nevertheless, we believe that there is a by no means

numerically insignificant public to whom THE PAGAN

REVIEW may appeal; though our paramount difficulty

will be to

reach those who, owing to various circum-

2 THE PAGAN REVIEW

stances, are out of the way of hearing aught concerning

the most recent developments in the world of letters.

⁂

THE PAGAN REVIEW conveys, or is meant to convey,

a good deal by its

title. The new paganism is a potent

leaven in the yeast of the “younger

generation”, without

as yet having gained due recognition, or even any

suffi-

ciently apt and modern name, any scientific designation.

The

“new paganism,” the “modern epicureanism,” and

kindred appellations, are

more or less misleading. Yet,

with most of us, there is a fairly definite

idea of what

we signify thereby. The religion of our forefathers has

not only ceased for us personally, but is no longer in

any vital and

general sense a sovereign power in the

realm. It is still fruitful of vast

good, but it is none

the less a poer that was rather than a power that

is.

The ideals of our forefathers are not our ideals, except

where

the accidents of time and change can work no

havoc. A new epoch is about

to be inaugurated, is,

indeed, in many respects, already begun; a new

epoch

in civil law, in international comity, in what, vast

and

complete though the issues be, may be called

Human Economy. The long

half-acknowledged, half-

denied duel between Man and Woman is to

cease,

neither through the victory of hereditary overlordship

nor the

triumph of the far more deft and subtle if

less potent weapons of the

weaker, but through a frank

recognition of copartnery. This new

comradeship will

be not less romantic, less inspiring, less worthy of

the

chivalrous extremes of life and death, than the old

system of

overlord and bondager, while it will open

perspectives of a new-rejoicing

humanity, the most

fleeting glimpses of which now make the hearts of

true men and women beat with gladness. Far from

wishing to disintegrate,

degrade, abolish marriage, the

“new paganism” with fain see that sexual

union

become the flower of human life But, first, the rubbish

must be

cleared away; the anomalies must be replaced

by just inter-relations; the

sacredness of the individual

must be recognized; and women no longer have

to look

upon men as usurpers, men lo longer to regard

women as

spiritual foreigners.

FOREWORD 3

⁂

These remarks, however, must not be taken too liter-

ally as indicative of the literary aspects of THE PAGAN

REVIEW.

Opinions are one thing, the expression of

them

another, and the transformation or reincarna-

tion of them through

indirect presentment another still.

This magazine is to be a purely literary, not a

philosophical, partisan, or propagandist periodical.

We are concerned

here with the new presentment of

things rather than with the phenomena

of change and

growth themselves. Our vocation, in a word, is to

give artistic expression to the artistic “inwardness”

of the new

paganism; and we voluntarily turn aside

here from such avocations as

chronicling every ebb

and flow of thought, speculating upon every fresh

sur-

prising derelict upon the ocean of man’s mind, or

expounding

well or ill on the new ethic. If those who

sneer at the rallying cry,

“Art for Art’s sake,” laugh

at our efforts, we are well content; for

even the lungs

of donkeys are strengthened by much braying. If, on

the other hand, those who, by vain pretensions and

paradoxical clamour,

degrade Art by making her

merely the more or less seductive panoply of

mental

poverty and spiritual barrenness, care to do a grievous

wrong by openly and blatantly siding with us, we are

still content; for

we recognise that spiritual byways

and mental sewers relieve the

Commonwealth of much

that is unseemly and might breed contagion.

THE

PAGAN REVIEW, in a word, is to be a

mouthpiece—we

are genuinely modest enough to disavow the definite

article–of the younger generation. In its

pages there will be found a

free exposition of the myriad

aspects of life, in each instance as

adequately as possible

reflective of the mind and literary temperament

of the

writer. The pass-phrase of the new paganism is ours:

Sic

transit gloria Grundi. The supreme interest of Man

is—Woman: and the

most profound and fascinating

problem to Woman is Man. This being so,

and quite

unquestionably so with all the male and female pagans

of

our acquaintance, it is natural that literature domi-

nated by the

various forces of the sexual emotion should

prevail. Yet, though

paramount in attraction, it is,

4 THE PAGAN REVIEW

after all, but one among the many motive forces of

life;

so we will hope not to fall into the error of some

of our French confreres

and be persistently and even

supernaturally awake to the functional

activity and

blind to the general life and interest of the common-

wealth of sould and body. It is LIFE that we preach,

if

perforce we must be taken as preachers at all; Life to

the full,

in all its manifestations, in its heights and

depths, precious to the

uttermost moment, not to be bar-

tered even when maimed and weary. For

here, at any

rate we are alive; and then, alas, after all—

“how few Junes

Will heat our pulses quicker. . . “

⁂

“Much cry for little wool”, some will exclaim. It

may

be so. Whenever did a first number of a new

magazine fulfil all its

editor’s dreams or even inten-

tions? “Well, we must make the best of

it, I suppose.

‘Tis nater after all, and what pleases God”, as

Mrs.

Durbeyfield says in “Tess of the Durbervilles.”

⁂

Have you read that charming roman à quatre, the

“Croix de Berny?” If so, you will recollect the

fol-

lowing words of Edgar de Meilhan (alias Théophile

Gautier), which I (“I” standing for editor, and asso-

ciates, and pagans in general) now quote for the delec-

tation of all

readers adversely minded or generously

inclined, or dubious as to our

real intent—with blithe

hopes that they may be the happier therefor:

“Frankly,

I am in earnest this time. Order me a dove-coloured

vest, apple-green trousers, a pouch, a crook; in short

the entire

outfit of a Lignon Shepherd. I shall have a

lamb washed to complete the

pastoral.”

⁂

This is “the lamb.”

⁂ Readers are requested to note the administra-

tional remarks on

the inside of the cover (p. ii.), and the

Forecast and Editorial intimations

printed at the end

of the text.

THE BLACK MADONNA.

The blood-red sunset turns the dark fringes of the

forest into a wave of flame. A hot river of light streams

through the

aisles of the ancient trees, and, falling over the

shoulder of a vast,

smooth slab of stone that rises solitary

in this wilderness of dark growth

and sombre green, pours

in a flood across an open glade and upon the

broken columns

and inchoate ruins of what in immemorial time had been

a mighty temple, the fane of a perished god, or of many

gods. As the sun

rapidly descends, the stream of red

light narrows, till, quivering and

palpitating, it rests like

a bloody sword upon a colossal statue of black

marble,

facing due westward. The statue is that of a woman,

and is as

of the Titans of old-time.

A great majesty is upon the mighty face, with its

moveless yet seeing eyes, its faint inscrutable smile.

Upon the

triple-ledged pedestal, worn at the edges like

swords ground again and

again, lie masses of large white

flowers, whose heavy fragrances rise in a

faint blue

vapour drawn forth with the sudden suspiration of the

earth by the first twilight-chill.

In the great space betwixt the white slab of

stone—

hurled thither, or raised, none knoweth when or how-is

gathered

a dark multitude, silent, expectant. Many are

Arab tribesmen, the remnant

of a strange sect driven

southward; but most are Nubians, or that

unnamed

swarthy race to whom both Arab and Negro are as chil-

dren.

All, save the priests, of whom the elder are clad in

white robes and the

younger girt about by scarlet sashes,

are naked. Behind the men, at a

short distance apart, are

the women; each virgin with an ivory circlet

round the

neck, each mother or pregnant woman with a thin gold

band

round the left arm. Between the long double-line

of the priests and the

silent multitude stands a small

group of five youths and five maidens;

each crowned with

6 THE PAGAN REVIEW

heavy drooping white flowers; each motionless, morose;

all with eyes fixt

on the trodden earth at their feet.

The younger priests suddenly strike together square

brazen cymbals, deeply chased with signs and letters

of a perished tongue.

A shrill screaming cry goes

up from the people, followed by a prolonged

silence.

Not a man moves, not a woman sighs. Only a shiver

contracts

the skin of the foremost girl in the small

central group. Then the elder

priests advance slowly,

chanting monotonously,

CHORUS OF THE PRIESTS:

We are thy children, O mighty Mother!

We are the slain

of thy spoil, O Slayer!

We are thy thoughts that are fulfilled, O

Thinker!

Have pity upon us!

screaming voice:

Have pity upon us! Have pity upon us! Have pity

[upon us!

THE PRIESTS:

Thou wast, before the first child came through the dark

[gate of the womb!

Thou wast, before ever woman knew man!

Thou wast, before the

shadow of man moved athwart

[the grass!

Thou wast, and thou art!

THE MULTITUDE:

Have pity upon us! Have pity upon us! Have pity

[upon us!

THE PRIESTS:

Hail, thou who art more fair than the dawn, more dark

[than night!

Hail thou, white as ivory or veiled in shadow!

Hail,

thou of many names, and immortal!

Hail, Mother of God, Sister of the

Christ, Bride of the

[Prophet!

THE MULTITUDE:

Have pity upon us? Have pity upon us! Have pity

[upon us!

THE BLACK MADONNA 7

THE PRIESTS:

O moon of night, O morning star! Consoler! Slayer!

Thou, who lovest shadow, and fear, and sudden death!

Who art the smile

that looketh upon women and children!

Who hath the heart of man in thy

grip as in a vice;

Who hath his pride and strength in thy sigh of

yestereve;

Who hath his being in thy breath that goeth forth, and

[is not!

THE MULTITUDE:

Have pity upon us! Have pity upon us! Have pity

[upon us!

THE PRIESTS:

We knew thee not, nor the way of thee, O Queen!

But we

bring thee what thou loved’st of old, and for ever!

The white flowers

of our forests and the red flowers of

[our bodies!

Take them and slay not, O Slayer!

For we are thy

slaves, O Mother of Life,

We are the dust of thy tired feet, O Mother

of God!

As the white-robed priests advance slowly towards

the

Black Madonna, the younger tear off their scarlet

sashes, and seizing the

five maidens, bind them together,

left arm to right, and hand to hand.

Therewith the

victims move slowly forward till they pass through the

ranks of the priests, and stand upon the lowest edge of the

pedestal

of the great statue. Towards each steppeth, and

behind each standeth, a

naked priest, each holding a

narrow irregular sword of antique

fashion.

THE ELDER PRIESTS:

O Mother of God!

THE YOUNGER PRIESTS:

O Slayer, be pitiful!

THE VICTIMS:

O Mother of God! O Slayer! be merciful!

THE MULTITUDE (in a loud screaming voice):

Have pity upon us! Have pity upon us! Have pity

[upon us!

The last blood-red gleam fades from the Black

Ma-

donna, and flashes this way and that for a moment from

8 THE PAGAN REVIEW

the ten sword-knives that cut the air and plunge between

the shoulders and

to the heart of each victim. A wide

spirt of blood rains upon the white

flowers at the base of

the colossal figure; where also speedily lie, dark

amidst

welling crimson, the swarthy bodies of the slain.

THE PRIESTS:

Behold, O Mother of God,

The white flowers of our

forests and the red flowers of

[our bodies!

Have pity, O

Compassionate,

Be merciful, O Queen!

THE MULTITUDE:

Have pity upon us! Have pity upon us! Have pity

[upon us!

But at the swift coming of the darkness, the priests

hastily cover the dead with the masses of the white

flowers; and one by

one, and group by group, the mul-

titude melteth away. When all are gone

save the young

chief, Bihr, and a few of his following, the priests

pros-

trate themselves before the Black Madonna, and pray to

her to

vouchsafe a sign.

From the mouth of the carven figure cometh a hollow

voice, sombre as the reverberation of thunder among

barren hills.

THE BLACK MADONNA:

I hearken.

THE PRIESTS (prostrate):

Wilt thou slay, O Slayer?

THE BLACK MADONNA:

Yea, verily.

THE PRIESTS (in a rising chant):

Wilt thou save, O Mother of God?

THE BLACK MADONNA:

I save.

THE PRIESTS:

Can one see thee, and live?

THE BLACK MADONNA:

At the Gate of Death.

Whereafter, no sound cometh from the statue, already

dim in the darkness that seems to have crept from the

THE BLACK MADONNA 9

forest. The priests rise, and disappear in silent groups

under the trees.

The thin crescent moon slowly rises. A phosphorescent

glow from orchids and parasitic growths shimmers inter-

mittently in the

forest. A wavering beam of light falls

upon the right breast of the Black

Madonna; then

slowly downward to her feet; then upon the motionless

figure of Bihr, the warrior-chief. None saw him steal

thither: none

knoweth that he has braved the wrath of

the Slayer; for it is the sacred

time, when it is death to

enter the glade.

BIHR (in a low voice):

Speak, Spirit that dwelleth here from of old . . .

Speak, for I would

have speech with thee. I fear thee

not, O Mother of God, for the priests

of the Christ who

is thy son say that thou wert but a woman. . .

And

it may be—it may be—what say the children of

the Prophet: that there is

but one God, and he is Allah.

(Deep silence. From the desert beyond the forest

comes the hollow roaring of lions.)

BIHR (in a loud chant):

To the north and to the east I have seen many figures

like unto thine,

gods and goddesses: some mightier than

thee—vast sphinxes by the flood of

Nilus, gigantic faces

rising out of the sands of the desert. And none

spake,

for silence is come upon them; and none slays, for the

strength of the gods passes even as the strength of men.

come snarling cries, 1ong-drawn howls, and the

low moaning sigh of the wind.)

BIHR (mockingly):

For I will not be thrall to a woman, and the priests shall

not bend me to

their will as a slave unto the yoke. If

thou thyself art God, speak, and I

shall be thy slave to

do thy will . . . . Thrice have I come hither

at

the new moon, and thrice do I go hence uncomforted

. . . .What

voice was that that spoke ere the

victims died? I know not; but it hath

reached mine

ears never save when the priests are by. Nay (laughing

low), O Mother of God, I—

10 THE PAGAN REVIEW

(Suddenly he trembles all over and falls on his

knees,

for from the blackness above him cometh a

voice:)

THE BLACK MADONNA:

What would’st thou?

BIHR (hoarsely):

Have mercy upon me, O Queen!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

What would’st thou?

BIHR

I worship thee, Mother of God! Slayer and Saver!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

What would’st thou?

BIHR (tremulously):

Show me thyself, thyself, even for this one time, O

Strength and

Wisdom!

Deep silence.. The wind in the forest passes away

with a faint wailing sound. The dull roaring of lions

rises and falls in

the distance. A soft yellow light

illumes the statue, as though another

moon were rising

behind the temple.

A great terror comes upon Bihr the Chief, and he

falls prostrate at the base of the Black Madonna.

His eyes are open, but they see not, save the burnt

spikes of trodden grass, sere and stiff save where damp

with newly-shed

blood; and deaf are his ears, though

he waits for he knoweth not what

sound from above.

Suddenly he starts, and the sweat mats the hair on

his forehead when he feels a touch on his right shoulder.

Looking slowly

round he sees beside him a woman, tall,

and of a lithe and noble body. He

seeth that her skin

is dark, yet not of the blackness of the south.

Two

spheres of wrought gold cover her breasts, and from the

serpentine zone round her waist is looped a dusky veil

spangled with

shining points. In her eyes, large as

those of the desert-antelope, is the

loveliness and the

pathos and the pain of twilight.

BIHR (trembling):

Art thou—Art thou—

THE BLACK MADONNA:

I am she whom thou worshippest.

THE BLACK MADONNA 11

BIHR

(looking at the colossal statue, irradiated by thestrange light that cometh he knows not whence;

and then at the beautiful apparition by his side.)

Thou art the Black Madonna, the Mother of God?

THE BLACK MADONNA:

Thou sayest it.

BIHR

Thou hast heard my prayer, O Queen!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

Even so.

BIHR

(Taking heart because of the sweet and thrillinghumanity of the goddess.)

O Slayer and Saver, is the lightning thine and the fire

that is in the

earth? Canst thou whirl the stars as

from a sling, and light the

mountainous lands to the

south with falling meteors? O Queen, destroy me

not,

for I am thy slave, and weaker than thy breath: but

canst thou

stretch forth thine hand and say yea to the

lightning, and bid silence

unto the thunder ere it breeds

the bolts that smite? For if—

THE BLACK MADONNA:

I make and I unmake. This cometh and that goeth,

and I am—

BIHR

And thou art—

THE BLACK MADONNA:

I was Ashtaroth of old. Men have called me many

names. All things change,

but I change not. Know

me, O Slave! I am the Mother of God. I am the

Sister

of the Christ. I am the Bride of the Prophet.

BIHR (with awe):

And thou art the very Prophet, and the very Christ, and

the very God! Each

speaketh in thee, who art older

than they—

THE BLACK MADONNA:

I am the Prophet.

BIHR

Hail, O Lord of Deliverance!

12 THE PAGAN REVIEW

THE BLACK MADONNA:

I am the Christ, the Son of God.

BIHR

Hail, O most Patient, most Merciful!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

I am the Lord thy God.

BIHR

Hail, Giver of Life and Death!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

Yet here none is; for each goeth or each cometh as I

will. I only am

eternal.

BIHR

(Crawling forward, and kissing her feet.)Behold, I am thy slave to do thy will: thy sword to slay:

thy spear to

follow: thy hound to track thine enemies.

I am dust beneath thy feet. Do

with me as thou wilt.

THE BLACK MADONNA:

(Slowly, and looking at him strangely.)Thou shalt be my High Priest. . . . .Come back

to-morrow an hour after the

setting of the sun.

As Bihr the Chief rises and goeth away into the

shadow she stareth steadily after him; and a deep fear

dwells in the

twilight of her eyes. Then, turning, she

standeth awhile by the slain

bodies of the victims of the

sacrifice; and having lightly brushed away

with her foot

the flowers above each face, looketh long on the

mystery

of death. And when at last she glides by the great

statue and

passes into the ruins beyond, there is no

longer any glow of light, and a

deep darkness covereth

the glade. From the deeper darkness beyond comes

the

howling of hyenas, the shrill screaming of a furious beast

of

prey, and the sudden bursting roar of lion answering

lion.

When the dawn breaks, and a pale, wavering light

glimmers athwart the great white slab of stone that,

on the farther verge

of the forest, faces the Black

Madonna, there is nought upon the pedestal

save a ruin

of bloodied trampled flowers, though the sere yellow

grass is stained in long trails across the open. The dawn

withdraws again,

but ere long suddenly wells forth, and

THE BLACK MADONNA 13

it is as though the light wind were bearing over the

forest a multitude of

soft grey feathers from the breasts

of doves. Then the dim concourse of

feathers is as

though innumerable leaves of wild-roses were falling,

falling, petal by petal uncurling into a rosy flame that

wafts upward and

onward. The stars have grown sud-

denly pale, and the fires of Phosphor

burn wanly green in

the midst of a palpitating haze of pink. With a

great

rush, the sun swings through the gates of the East, tossing

aside his golden, fiery mane as he fronts the new day.

And the going of the day is from morning silence

unto

noon silence, and from the silence of the afternoon

unto the silence of

the eve. Once more, towards the

setting of the sun, the multitude cometh

out of the

forest, from the east and from the west, and from the

north and from the south: once more the Priests sing the

sacred hymns:

once more the people supplicate as with

one shrill screaming voice, Have pity upon us! Have

pity upon us! Have pity upon

us! Once more the

victims are slain of little children who might

one day

shake the spear and slay, five; and of little children who

would one day bear and bring forth, five.

Yet again an hour passeth after the setting of the

sun. There is no moon to lighten the darkness and the

silence; but a soft

glow falleth from the temple, and

upon the mall who kneels before the

Black Madonna.

But when Bihr, having no sign vouchsafed, and hearing

no sound, and seeing nought upon the carven face,

neither tremour of the

lips nor life in the lifeless eyes,

suddenly seeth the goddess, glorious

in her beauty that

is as of the night, coming towards him from out of

the

ruins, his heart leapeth within him in strange joy and

dread.

Scarce knowing what he doth, he springeth to

his feet, trembling as a reed

that leaneth

against the flank of a lioness by the water-pool.

BIHR (yearningly, with supplicating arms):

Hail, God! . . . .Goddess, Most Beautiful!

She draws nigh to him, looking at him the while

out

of the deep twilight of her eyes.

THE BLACK MADONNA:

What would’st thou?

14 THE PAGAN REVIEW

BIHR

(Wildly, stepping close, but halting in dread.)Thou art no Mother of God, O Goddess, Queen, Most

Beautiful!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

What would’st thou, O blind fool that is so in love with

death?

BIHR (hoarsely):

Make me like unto thyself, for I love you!

Deep silence. From afar, on the desert, comes the

dull roaring of lions by the water-courses; from the

forest a murmurous

sound as of baffled winds snared

among the thick-branched ancient

trees.

BIHR

(Sobbing as one wounded in flight by an arrow.)For I love thee: I—love-thee! I—

Deep silence. A shrill screaming of a bird fascinated

by a snake comes from the forest. Beyond, from the

desert, a long,

desolate moaning and howling, where the

hyenas prowl.

THE BLACK MADONNA:

When . .did . . thy folly . .this madness

. . come upon thee . . O Fool?

BIHR (passionately):

O Most Beautiful! Most Beautiful! Thou—Thou—

will I worship!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

Go hence, lest I slay thee!

BIHR

Slay, O Slayer, for thou art Life and Death!

. . . But I go not hence. I

love thee! I love thee! I love

thee!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

I am the Mother of God.

BIHR

I love thee!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

God dwelleth in me. I am thy God.

BIHR

I love thee!

THE BLACK MADONNA 15

THE BLACK MADONNA:

Go hence, lest I slay thee!

BIHR

Thou tremblest, O Mother of God! Thy lips twitch,

thy breasts heave, O

thou who callest thyself God!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

(raising her right arm menacingly.)Go hence, thou dog, lest thou look upon my face no more.

Then suddenly, with bowed head and shaking limbs,

Bihr the Chief turneth and passes into the forest. And

as he fades into

the darkness, the Black Madonna stareth

a long while after him, and a deep

fear broodeth in the

twilight of her eyes. But by the bodies of the

slain

children she passes at last, and with a shudder looks

not upon

their faces, but strews the heavy white flowers

more thickly upon

them.

The darkness cometh out of the darkness, billow

welling forth from spent billow on the tides of night.

On the obscure

waste of the glade nought moves, save

the gaunt shadow of a hyena that

crawls from column

to column. From the blackness beyond swells the

long

thunderous howl of a lioness, echoing the hollow blasting

roar

of a lion standing, with eyes of yellow flame, on the

summit of the great

slab of smooth rock that faces the

carven Madonna.

And when the dawn breaks, and long lines of

pearl-

grey wavelets ripple in a flood athwart the black-green

sweep

of the forest, there is nought upon the pedestal

but red flowers that once

were white, rent and scattered

this way and that. The cool wind moving

against the

east ruffles the opaline flood into a flying foam of

pink,

wherefrom mists and vapours rise on wings like rosy

flames, and

as they rise their crests shine as with

blazing gold, and they fare forth

after the Morn that

leads towards the Sun.

And the going of the day is from morning silence

unto

noon silence, and from the silence of the afternoon

unto the silence of

eve. Once more towards the setting

of the sun, the multitude cometh out of

the forest, from

the east and from the west, and from the north and

from

the south. Once more the priests sing the sacred

16 THE PAGAN REVIEW

hymns: once more the people supplicate as with one

shrill screaming voice,

Have pity upon us! Have pity

upon us! Have pity

upon us! Once more the vic-

tims are slain: five chiefs of

captives taken in war, and

unto each chief two warriors in the glory of

youth.

Yet an hour after the setting of the sun. Moonless

the silence and the dark, save for the soft yellow light

that falleth from

the temple, and upon the man who,

crested with an ostrich-plume bound by a

heavy circlet

of gold, with a tiger-skin about his shoulders, and

with

a great spear in his hand, standeth beyond the statue

and nigh

unto the ruins, where no man hath ventured

and lived.

BIHR (with loud triumphant voice):

Come forth, my Bride!

Deep silence, save for the sighing of the wind among

the upper branches of the trees, and the panting of the

flying deer beyond

the glade.

BIHR

(striking his spear against the marble steps.)Come forth, Glory of my eyes! Come forth, Body of

my Body.

Deep silence. Then there is a faint sound, and the

Black Madonna stands beside Bihr the Chief. And the

man is wrought to

madness by her beauty, and lusteth

after her, and possesseth her with the

passion of his eyes.

THE BLACK MADONNA:

(Trembling, and strangely troubled.)What would’st thou?

BIHR

Thou!

THE BLACK MADONNA (slowly):

Young art thou, Bihr, in thy comeliness and strength

to be so in love

with death.

BIHR

Who giveth life, and who death? It is not thou, nor I.

THE BLACK MADONNA (shuddering):

It cometh. None can stay it.

BIHR

Not thou? Thou can’st not stay it, even?

THE BLACK MADONNA 17

THE BLACK MADONNA (whisperingly):

Nay, Bihr; and this thing thou knowest in thy heart.

BIHR (mockingly):

O Mother of God! O Sister of Christ! O Bride of the Prophet!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

(putting her hand to her heart.)What would’st thou?

BIHR

Thou!

THE BLACK MADONNA:

I am the Slayer, the Terrible, the Black Madonna.

BIHR

And lo, thy God laugheth at thee, even as at me, and

mine. And lo, I have

come for thee; for I am become

His Prophet, and thou art to be my

Bride!

As he finisheth he turns towards the great Statue of

the

Black Madonna and, laughing, hurls his spear against its

breast,

whence the weapon rebounds with a loud clang.

Then, ere the woman knows

what he has done, he leaps

to her and seizes her in his grasp, and kisses

her upon

the lips, and grips her with his hands till the veins sting

in her arms. And all the sovereignty of her lonely

godhood passeth from

her like the dew before the hot

breath of the sun, and her heart throbs

against his side

so that his ears ring as with the clang of the gongs

of battle. He sobs low, as a man amidst baffling waves;

and in the hunger

of his desire she sinks as one who

drowns.

Together they go up the long flat marble steps:

together they pass into the darkness of the ruins.

From the deeper

darkness beyond cometh no sound, for

the forest is strangely still. Not a

beast of prey comes

nigh unto the slain victims of the sacrifice, not a

vulture

falleth like a cloud through the night. Only, from afar,

the

dull roaring of the lions cometh up from the water-

courses on the

desert.

And the wind that bloweth in the night cometh with

rain and storm, so that when the dawn breaks it is as a

sea of sullen

waves grey with sleet. But calm cometh

out of the blood red splendour of

the east.

18 THE PAGAN REVIEW

And on this, the morning of the fourth and last day

of

the Festival of the Black Madonna, the multitude of her

worshippers come forth from the forest, singing a glad

song. In front go

the warriors, the young men brandish-

ing spears, and with their knives in

their left hands slicing

the flesh upon their sides and upon their thighs:

the men

of the north clad in white garb and heavy burnous, the

tribesmen of the south naked save for their loin-girths,

but plumed as for

war.

But as the priests defile beyond them upon the glade,

a strange new song goeth up from their lips; and the

people tremble, for

they know that some dire thing hath

happened.

THE PRIESTS (chanting):

Lo, when the law of the Queen is fulfilled, she

passeth

from her people awhile. For the Mother of God loveth

the

world, and would go in sacrifice. So loveth us the

Mother of God that

she passeth in sacrifice. Behold,

she perisheth, who dieth not! Behold,

she dieth, who

is immortal !

Whereupon a great awe cometh on the multitude, as

they behold smoke, whirling and fulgurant, issuing from

the mouth and

nostrils of the Black Madonna. But this

awe passeth into horror, and

horror into wild fear, when

great tongues of flame shoot forth amidst the

wreaths

of smoke, and when from forth of the Black Madonna

come

strange and horrible cries, as though a mortal

woman were perishing by the

torture of fire.

With shrieks the women turn and fly; hurling their

spears from them, the men dash wildly to the forest,

heedless whither they

flee.

But those that leap to the westward, where the great

white rock standeth solitary, facing the Black Madonna,

see for a moment,

in the glare of sunrise, a swarthy,

naked figure, with a tiger-skin about

the shoulders,

crucified against the smooth white slope. Down from

the

outspread hands of Bihr the Chief trickle two long

wavering

streamlets of blood: two long streamlets of

blood drip, drip, down the

white glaring face of the

rock, from the pierced feet.

THE COMING OF LOVE.

In and out the osier beds, all along the

shallows

Lifts and laughs the soft south wind, or swoons

among

the grasses.

But ah, whose following feet are these that bend the

gold

marsh-mallows,

Who laughs so low and sweet? Who

sighs—and

passes?

Flower of my heart, my darling, why so slowly

Lift’st thou thine eyes to mine, deep wells of

gladness?

Too deep this new-found joy, and this new pain too

holy—

Or is there dread in thy heart of this

divinest mad-

ness?

Who sighs with longing there?—who laughs alow—

and passes?

Whose following feet are these that bend the gold

marsh-

mallows?

Who comes upon the wind that stirs the heavy seeding

grasses,

In and out the osier beds, and hither

through the

shallows?

Flower of my heart, my dream—who whispers near so

gladly?

Whose is the golden sunshine-net o’erspread for cap-

ture?

Lift, lift thine eyes to mine who love so wildly,

madly—

Those eyes of brave desire, deep wells

o’erbrimmed

with rapture!

THE PAGANS.

A MEMORY.

“Ma contrée de dilution n’existe pour aucun

touriste et jamais guide ou médecin ne la

recommandera.”

GEO. EECKHOUD. Kermesses.

“Come, my beloved, let us go forth into the

fields; let us lodge in the villages.”

Song of Solomon.

“. . . . . lo! with a little rod

I did but touch the honey of romance—

And must I lose a soul’s inheritance?”

OSCAR WILDE.

BOOK I.

I.

The wind and the sunshine. I think of them always

when I

whisper to myself her name—the name I loved

best to can her by. To others she

was Claire Auriol;

to a privileged few she was Sans-Souci. To myself, and

myself only, she was—ah, Sweet-Heart, no, the word is

ours, and ours only, for

ever.

We ought to have been born gipsies. Certainly we

both loved

the sunshine, and the blithe freedom

of nature, with a passion. It was under

the trees, under

the deep blue wind-swept sky, that we first realised

each

had won from the other a lifetime of joy. True, it

was still winter. The snow

lay deep by the hedges, and

we had to slip through many a drift before we

reached

the lonely woodland height whither we were bound.

But was there

ever snow so livingly white, so lit with

golden glow? Was ever summer sky more

gloriously

blue? Was ever spring music sweeter than that exqui-

site

midwinter hush, than that deep suspension of breath

before the flood of our

joy?

THE PAGANS 21

How poignantly bitter-sweet was our separation so

soon

thereafter! You had to rejoin your brother in

Paris, and resume your painting in

his studio; and I

had to go to the London I hated so much, there to

write

concerning things about which I cared not a straw,

while my heart was full of

you, and my eyes saw you

everywhere, and my ears were haunted day and night

by echoes of your voice.

And oh, what joy it was when at last I had enough

money in

hand to be independent of London, if not for

good, at least for a year or so;

and when once more I

found myself in Paris. What joy to meet you again:

to

find that we had not changed: that it was not all a

dream: that we loved each

other more than ever.

II.

What happy days those were in that bygone spring!

I wonder

if ever two people were happier? Yes; we

were, when we left Paris behind us, and

went away

together, as light-hearted as the April birds, as free as

the

wind itself. But even in Paris, what glad hours we

had! Ah, those Sunday

breakfasts at Suresnes, by the

riverside: those idle mornings on the sunlit

grass at

Longchamp, or amid the elms and chestnuts of St. Cloud:

those

happy days at Fontainebleau or Rambouillet:

those hours on the river when even

forlorn Ivry seemed

a lovely and desirable place: those hours, at twilight,

in the Luxembourg Gardens, when the thrush would

sing as, we were sure, never

nightingale sang in forest-

glade, or Wood of Broceliande: those hours in

the

galleries, above all before our beloved Venus in the

Louvre: ah,

beautiful hours, gone for ever, and yet im-

mortal, because of the joy that they

knew and whereby

they live and are even now fresh and young and sweet

with

their exquisite romance.

III.

And that day, that golden day, when we said that we

would

waste no more of the happy time of youth, but

go away together, and live our

life as seemed to us best!

Can I ever forget how I came round to the studio in

the

little Hôtel Soleil du Midi, shining white in the

22 THE PAGAN REVIEW

sunshine as a chalk cliff, but dappled and splashed all

over with bluish shadows

from the great chestnuts of

the Luxembourg Gardens: and how I found you

alone,

and in tears, before that too flattering portrait of me

which you

had painted so lovingly, through such joyous

hours, with beneath it, in

fantastic letters which you

would persist were Old German, but bore no

resemblance

to any known caligraphy, the blithe couplet—

“Douce nuit et joyeux jour,

O Chevalier de bel amour.”

How angry you were with your brother Raoul because he

had told you he did not

approve of your free Bohemian

life—because he had mocked your “douces nuits”

and

“joyeux jours”—and had told you at last that you

must choose between

him and your “chevalier de bel

amour:” the real, not the painted, one.

IV.

Is it all a dream? How well I remember how beauti-

ful she

looked, as she stood before the easel which held

my portrait, her palette and

brushes lying on a low

paint-daubed table beside her, her hands clasped as

they hung despondingly before her. Let me essay her

portrait, though there is no fear that I can flatter her,

dear heart, as she flattered me. Tall she was, and grace-

ful as a mountain-ash, or as a wild deer, or as a wave

upon the sea, or any

other beautiful thing that one

loves to look upon for its exquisiteness of poise

and

movement. It was this characteristic, I think, that first

made me liken

her in my mind to a flower; and that

was the origin of a name I often called her

by, and that

she loved to hear, White Flower. Not that, in a sense,

the

word “white” was literally apt. She was not blonde,

and her skin, though fair

and soft, was in keeping with

the rich dark of her hair and sweeping eyebrows

and

long lashes. Paler than ivory, it was touched with a

delicious brown,

the kiss of sunshine and fresh air; and

yet was so sensitive that it would

redden at a moment—

a flush so lovely and blossom-like that her beauty be-

came at once bewilderingly enhanced by it. White,

certainly, were the teeth that

gleamed like hawthorn-

THE PAGANS 23

buds behind the wild roses of her curved lips, and pink

and white the small

sensitive ears that clung like

swallows under the eaves of her shadowy hair:

but

lovely as dusk was she otherwise. Her lustrous dark

hair, that looked

quite black at night, had a crisp and

a wave in it that caught all manner of

wandering lights ;

so that, in full sunlight, and sometimes by firelight or

even lampiight, it seemed as though shot with bronze.

It rose in an upward wave

from her broad white brow,

and was gathered together in a bewitching mass

behind

in a way that I am sure was hers only. Her features

were more

southern than northern in their classic sweep

and cut, and yet, northerner that

I am, I loved them

the more for certain delicious inconsistencies and

irregu-

larities. Her face, indeed, might almost have been

thought too

square-set about the lower part but for

the loveliness of the general contour

and the redeeming

sweetness and beauty of the mouth. Her eyes—those

eyes

which have so often thrilled me beyond words,

those deep lustrous springs into

which I have gazed so

often, fascinated by the strange joy, the strange

longing,

a longing that was often pathos, and by the still stranger

melancholy that I could never quite divine, and of which

Claire herself was

mostly unconscious—her eyes are in-

describable. They varied from a rich velvety

darkness,

like the colour of midsummer twilight on cloudless eves,

when the

hour is still what in the north they call “the

edge o’ dark,” to a clear

brown-grey or grey-brown, of

that indeterminate light and sparkle one sees in

moun-

tain streams that wimple over sunny shallows of moss

and pebbles. In

certain lights they had that lustrous

green ray which has ever been beloved by

poets and

painters. Lovely, mysterious eyes they were at all times;

though

possibly none felt their mystery save myself, for

they were clear and fresh as

the sunlit sea, as daring

as a flashing sword, as dauntless as a martyr’s

before

the affront of death. Even in the drawing, even in

the photograph of

her that I have before me now, I

find this quality of mysterious

unfathomableness. It is,

indeed, more obvious there—in the photograph pre-

eminently—than it was in life. Even a stranger look-

ing upon this phantom-face

might wonder what manner

24 THE PAGAN REVIEW

of girl, or woman, the original actually was; whether a

bright or a sombre

spirit dwelt in those darkly reticent

eyes.

The poise of her head, the rhythmic sway and carriage

of

her body, every motion, every gesture, made a fresh

delight for all who looked

at her. I have travelled much,

and seen the peasant-women of Italy and Greece,

but

have never elsewhere so realised the poetry of human

motion. Claire

might have served a sculptor as an ideal

model of Youth. She was slight in

figure, and yet so

lithe and strong that she could outwalk and even out-

climb many a robust man. Whether we tramped many

miles together, or rambled

through woods or by river-

sides, we never seemed to tire, till all at once we

felt

the wish or need of rest. Certainly we never tired each

other. I think

this was due to our absolute fitness for

each other. All lovers say that each

was made for the

other, but in the nature of things there must be few

who

are such counterparts as Claire and I were. In

everything. from temperament to

height, she was to me

all that the eyes of the soul and the eyes of the

body

desired in deep comradeship and love.

Then the charm of her blithe, brave spirit! How

often have

I called her Sunshine; how often Dawn, and

Morning? For she was ever to me the

living symbol,

nay, the perfect incarnation of the joy and beauty of

life.

I have never met any woman so fearless; few so

self-reliant, so sunnily joyous

while so easily wrought to

intense feeling.

We were happy in our recognition of the fact that

we could

be, as we latterly were, all in all to each

other; that each was for the other

the supreme lure,

the summoning joy, in the maze of life.

V.

When I entered the little studio that day, in the for-

saken but sunny and charming old hotel where Claire

and Victor Auriol lived, I

knew at once that something

was far wrong; for Sans-Souci, as she was called

by

intimate acquaintances among her artist friends, was

the last person to

give way to tears on a slight excuse.

For tears there were in those beautiful

eyes, though

THE PAGANS 25

but one or two had fallen from the long lashes. In a

few words she told me

all.

Victor was tired of living with her, and had sought

many

excuses recently to justify his ill-mannered hints.

Though both were artists, no

two persons could be more

unlike. He was rigid, formal, conventional;

without

intellectual breadth or even sympathy; with coarse, if

not actually

depraved, tastes, which he possessed and

tantalised rather than gratified. When,

a year or two

before I first met them, during what I called my literary

apprenticeship in Paris (though I am afraid I haunted

the book-shelves on the

left bank of the Seine, and,

above all, the librairie

of Léon Vanier, that literary

sponsor of so many of les

jeunes, much more than more

academic resorts), their father had

followed to the grave

their Irish mother—and Marcel Auriol was himself, I

should add, half English, or rather Scottish, despite his

French name—and left

his two children a moderate

competency. But the conditions of the heritage

were

unfair; for while the annual income of six thousand

francs was to be

looked upon as equally between Victor

and Claire so long as they lived together,

Claire was to

have but two thousand if she married, and only one

thousand

if this marriage were not one approved of by

her brother, or if she voluntarily

lived apart trom him.

Now, as it happened, Victor had a lust of gold that

blunted his sense of honour, and he was eager to part

from his sister, in whose

company be was ever uneasy,

and to appropriate the lion’s share of the

inheritance.

To do him justice, he might have acted otherwise if

Claire had

been different from what he knew her. He

comforted his conscience with the

sophistries that

Claire’s drawings were more saleable than his own, and

that therefore she did not need the money so much

as he did; that she was

beautiful, and would certainly

make a good match; that he was really meeting

her

half-way, since her great craving was for independence.

Still, it was with a certain bitterness, perhaps even a

certain clinging regret, that Sans-Souci (a name, by the

way, her brother hated)

had listened to him that morn-

ing, when he had given his ultimatum. She was, he

demanded, to go with him to the little house

at Sceaux

26 THE PAGAN REVIEW

he thought of taking, and there to act as housekeeper;

to be content with this

life, and to give up once and for

all her Bohemian ways; and, above all, to see

no more,

and to have no further communication with, “that

arrogant and

offensive Scot, Wilfrid Traquair, kinsman

though he be”—in other words, the

present writer!

All this was but a mean way of forcing Claire’s hand.

Victor Auriol knew well that she would refuse to accede

to his demands; and

though she was not blind to his

intent she disdainfully refused to plead or

argue for

her rights.

And the end of it was that they had agreed to part.

Victor

had, with convenient suddenness, decided to give

up the Sceaux house and to

remain in the Hôtel Soleil

du Midi. With a promptness that betrayed how

calcu-

lated everything had been, he explained to his sister

that by her

own folly she would hencetorth be entitled

to but one thousand francs annually;

and that, in view

of all the circumstances, the separation must be a com-

plete one. In other words, Claire was to go; with the

consciousness that the

manner of her going, her imme-

diate destination, and her future movements were

alike

matters of indifferent moment to her brother.

It was then and there, in that sunny studio, with the

white

doves fluttering their wings on the wide green

sill beside the open window, that

Sans-Souci and I

decided to fulfil one of our happy dreams and go away

together.

It was on the morrow following this decision of ours

that

Sans-Souci said good-bye (and, as it happened, a

lifelong farewell) to her

brother. She had packed up

all her few belongings that she cared to keep, and

sent

them to the care of a friend in the Rue Grégoire de

Tours, that

narrow, inconspicuous byway from the great

Boulevard St. Germain, so well known

to the poorer stu-

dents and artists of the neighbourhood. When I reached

the court of the Hôtel Soleil du Midi I saw her standing

there, talking quietly

to the concierge as if she were

about to go forth only to return again, as of

yore.

I was too glad, too wildly elated, to express anything

of

the overmastering happiness that I felt in seeing her

there, alone, and ready to

go forth with me—in the

THE PAGANS 27

recognition that the past night, so interminable in its

sleepless anxiety, was

not a fantastic dream.

“Where are your things, Claire?” was all that I said,

in a

low and somewhat constrained voice: “I mean

your bag, or whatever you have.”

She looked at me half surprisedly with her clear,

steadfast

eyes, as she replied, quite simply and naturally,

and as though the concierge

were not beside us:

“Why, Will, dear, I did as we arranged, and sent them

to

Pierre Vicaire’s, near the Pont des Arts. You said

you would do the same, and

that we would call there on

our way to the hirondelle

for Charenton.”

“Of course, of course,” I muttered confusedly, and

half

turned as if eager to go—as indeed I was, particu-

larly as I had just caught

sight of Victor Auriol’s dark,

forbidding face behind a thin lace curtain at one

of the

windows.

With a low laugh, sweet as the sound of rain after a

drought, Sans-Souci slipped her hand into mine.

“At last—at last,” she breathed in a

thrilling whisper,

while her dear eyes shone with a strange light. Then,

turning, and waving her hand to the concierge, she bade

him a blithe

good-bye.

“Au revoir—adieu—adieu, M. Bonnard.

Do not wait

too long before thou takest that little inn in Barbizon

that

you dream of! Adieu!

“Aha!” cried the man, with a roguish smile: “mon-

sieur et madame contemplent une mariage au treizième

arrondissement!

But just as by a side glance I noticed the slight flush

in

Claire’s face, M. Bonnard’s wife handed me a note on

my passing her open

doorway. I guessed rather than

knew that it was from Victor Auriol. It was

addressed

in the following fantastic fashion:—

Á Monsieur Wilfrid Traquair,

Vagrant,

of God-knows-Where.

A hearty shout of laughter from Sans-Souci and my-

self

must have reached his ears. Just before we emerged

upon the street, I glanced

back and saw him abruptly

28 THE PAGAN REVIEW

withdraw his face from behind the lace curtain at the

open window. The contents

of the note ran thus:

“MONSIEUR: That my sister has chosen to unite

herself with

a beggarly Scot is her pitiable misfortune:

that she has done so without even

the decent veil of

marriage is her enormity and my disgrace. Henceforth

I

know as little of the one as of the other, and I beg

you to understand that

neither you nor the young

woman need ever expect the slightest tolerance,

much

less practical countenance, from me. You are both at

liberty to hold,

and carry out, the atrocious opinions (for

I will not flatter you by calling

them convictions) upon

marriage which you entertain or profess to entertain:

I,

equally, am at liberty to abstain from the contagion of

such unpleasant

company, and to insist henceforth upon

an insurmountable barrier between it and

myself.

“VICTOR MARIE

AURIOL.”

The next moment we had hailed and sprung into a

little open

voiture, and in another minute had lost sight

of the Hôtel Soleil du Midi.

Outcasts we were, but two

more joyous pagans never laughed in the sunlight,

two

happier waifs never more fearlessly and blithely went

forth into the

green world.

(To be continued.)

AN UNTOLD STORY.

I.

When the dark falls, and as a single star

The orient planets blend in one white ray

A-quiver through the violet shadows far

Where the rose-red still lingers mid the grey:

And when the moon, half-cirque arm around her

hollow,

Casts on the upland pastures shimmer of green:

And the marsh-meteors the frail lightnings follow,

And wave laps into wave with amber sheen—

O then my heart is full of thee, who never

From out thy beautiful mysterious eyes

Givest one glance at this my wild endeavour,

Who hast no heed, no heed, of all my sighs:

Is it so well with thee in thy high place

That thou canst mock me thus even to my face?

II.

Dull ash-grey frost upon the black-grey fields:

Thick wreaths of tortured smoke above the town:

The chill impervious fog no foothold yields,

But onward draws its shroud of yellow brown.

No star can pierce the gloom, no moon dispart:

And I am lonely here, and scarcely know

What mockery is “death from a broken heart'”

What tragic pity in the one word: Woe.

But I am free of thee, at least, yea free!

No more thy bondager ‘twixt heaven and hell!

No more there numbs, no more there shroudeth me

The paralysing horror of thy spell:

No more win’st thou this last frail worshipping

breath,

For twice dead he who dies this second death.

THE RAPE OF THE SABINES.

A flame of blood-red light streamed, a flying

banner,

from Monte Catillo, over the olive heights of Tivoli, to

Frascati and the flanks of the Albans. Westward, the

Campagna was

shrouded in violet gloom. The tallest

of the pines and cypresses in

Hadrian’s Villa, catching

the last of the sunset-glow, burned slowly to

their

summits, like torches extinguished by currents of air

from

below. Between Castel Arcione and the base of

the Sabines, where the

intermingling summits sweep

upward frolll the Montecelli to Palombara,

and thence

by giant Subiaco to the innumerable peaks and ranges

of

the mountain-land beyond, lay a white mist, wan as

the sheen of a new

moon on burnt grass—save in the

direction of the ancient Lago de’

Tartari, where it hung

heavy and darkly grey, dense as it was with the

sulphur-

fumes of the Acquae Albulae.

On the flat, before the upward swell to Tiveli

begins,

the hill-road curves to the left, the via

Palombara-

Marcellina. To the right there is a rough path,

striking

off waveringly betwixt the Palombara road and the

highway

from Rome to Tivoli: at first like a bridle-way,

then but a sheep-path

or dried-up course of a hill-torrent.

Following this, one enters the

wild and lonely Glen of

the Shepherds, though seldom does any shepherd

wander

there, and even the solitary goatherd rarely descends

from

the steep heights of Sterpara that overhang it from

the west.

The nightingales were in full song. One after

another

had called through the dusk with clear, thrilling notes:

one after another had swung a sudden lilt of music

across the myrtles,

through the thickets of wild rose and

honeysuckles, over the clustered

arbutus, and down by

the birch-hollows, where the narrow stream

crawled

suffocatingly through fern-clumps and tufted grasses.

Close to where some stunted, decrepit olives clung

THE RAPE OF THE SABINES 31

despairingly to a bank of fissured soil rose a wild mag-

nolia, whose

white blooms gleamed in the twilight like

ivory discs. Suddenly, from

where its topmost sprays still

retained a dusky green hue, a thrush

sprang violently

into the air and darted westward against the

crimson

light, clattering loudly and shrilly like a

heavily-feathered

arrow whistling towards the already blood-strewn

flanks

of a beast of prey. A nightingale among the myrtles

near

flew earthward, dipping his breast against the dewy

anemones that

clustered in the shadow; but ere the

spray whence he had slipt like a

rain-drop had ceased

its last tremulous vibration he was swinging, with

out-

spread wings, upon a branch of the deserted magnolia.

Then

came a loud summoning cry, a few low calls, and

all at once a burst of

ecstatic song. In a few moments

all was still around, save for the

shrilling of the locusts

and the distant croaking of frogs. But

suddenly, and

in the midst of his love-song, the nightingale

ceased,

gave a broken, dissonant cry, and with a rapid tilt and

poise of his wings was lost in the under-dark like a

blown leaf.

Something stirred under the lower boughs of the

mag-

nolia. A small, dark figure crept on out, and then a boy

of

some ten or twelve years rose to his feet, stretched

himself warily,

ran his hands through his shaggy black

hair, and began to mutter to

himself. All at once he

inclined his head and listened intently. Before

he could

sink back to his shelter, two young men stepped

noise-

lessly from behind the higher olives, the taller of the

two

coming rapidly forward.

“Do not be afraid, Guido,” he exclaimed, as he saw

the boy alert for flight; “it is I—Andrea Falcone.”

“And he?”

“Marco Vaccaro, of course. Who other, per Bacco?“

“You are late, elder-brothers.”

“We could not get here earlier, unobserved. There

is time enough. What is the message? “

While he was speaking his companion drew near.

Both

young men were singularly handsome, with clear-

cut features, dark,

eloquent eyes, and faces pale as

blanched ivory. Lithe and vigorous

mountaineers, they had

all the grace and dignity of the Roman

peasant;

32 THE PAGAN REVIEW

and though they had the Campagna melancholy in

their faces, each had

that alert look common to all the

Sabine muleteers. Everyone in the

Montecelli knew

the cousins Andrea Falcone and Marco Vaccaro; and

in

the hill-town of S. Angelo in Capoccia itself, there was no

question as to their pre-eminence in all things that,

locally,

constituted good fortune. Not only was the story

of their deep

friendship well known—a friendship so

close that one would never go far

without the other, to

the extent that if a rich forestiero wanted one of them

as a guide up Subiaco, he

would perforce have to engage

both—but, the gossips of the

hill-villages were each and

all aware of the love Andrea and Marco bore

for Vittoria

and Anita, the daughters of Giovan’ Antonio Della

Porta,

the vintner and ex-brigand of that remote and highest

hill-town of the Sabines, San Polo de’Cavalieri. Naturally,

it was

delightful food for these gossips when a feud broke

out between the

muleteers of San Polo and of Palombara

and San Angelo, in consequence

of which neither Andrea

nor Marco dare set foot in the vicinage of the

town—not

only because old Della Porta swore that, whether they

willed or no, his daughters should marry none but men

of pure Sabine

blood, and certainly no accurst Roman

contadini (for all their

hill-folk talk!), but also because

a league of San Polo youths and men,

headed by Simone

Gaetano and Gregorio da Forma, had sworn to

poniard

any” Angelinis” they found within the village boundaries.

It was quite natural that Gregorio da Forma and Gae-

tano should be the

active ministers in this league of hate,

for the former was desirous of

Anita Della Porta and

Simone lusted after the beautiful Vittoria. But

both

girls were closely watched, and though they had several

times

managed to meet their lovers in the woods, or amid

the copses of the

Glen of the Shepherds, such encounters

were no longer possible. The

girls had, indeed, but one

ally, but one emissary—their young

half-brother, Guido.

Guido loved his sisters; but he had another bond

of

fellowship—hatred of their morose and tyrannical father.

Twice

had Vittoria and Anita tried to evade those who

kept an eye on them:

once by attempted flight to

Vicovara and once across Ponte Rotto to

Castel Ma-

dama—for they had imagined success impossible by

THE RAPE OF THE SABINES 33

way of Palombara. It was after the last occasion that

old Della Porta

had publicly proclaimed the approaching

marriage of his daughters with

Simone Gaetano and

Gregorio da Forma.

The Sabine women can be as quick with their long,

thin hair-daggers as the Sabine men with their poniards.

A girl of the

Sabines, moreover, does not hesitate to use

her dagger in offence as

well as in self-defence; and,

when the blood-vow is once sworn, the

steel, as the

saying is, sweats with thirst.

It was at the risk of their lives, then, that

Andrea

Falcone and his friend and kinsman, Marco, were met

in the

Glen of the Shepherds, within an easy eagle’s-

flight of San Polo. If

any muleteer on Sterpara or

goatherd on the slopes should see them, the

cry would

go from coign to coign, and find a score of fierce

echoes

in the dark narrow streets of the mountain vilbge. As

for

Guido, he ran the chance of a flaying from his father,

or eyen a

knifing from cruel, treacherous Simone or from

sullen Gregorio.

“What is the message?” repeated Andrea,

impatiently,

while Marco eyed the neighbourhood like a hawk, and

Guido stood as taut and eager as a goat about to leap.

“There is none, elder brother. I could not see either

Vittoria or Anita. But this is their last night.”

“Their last night? How?” interjected Marco, in a

startled but suppressed voice.

“The last night of their virginity,” said Guido,

simply.

“To-morrow Vittoria will be wed to Simone and Anita

to

Gregorio.”

A silence fell upon the men: a frost of passion,

rather,

that seemed to paralyse even gesture or glance.

“Have they been true women?” said Andrea, at last,

in a thick, husky voice.

“True women?” repeated Guido, interrogatively, his

great black eyes flashing half-inquiringly, half-sus-

piciously.

“Ay, true women. Have they sworn the virgin-vow?”

“Yes: they swore it last night, and before me as

witness. It was in the moonlight, by the old fountain

I beyond the

church.”

“Upon both the blade and the hilt?”

34 THE PAGAN REVIEW

“Si, si, si: and upon their crucifixes also.”

Andrea turned and looked at Marco with a meaning

smile.

“Ecco, Marco: it will be a wet wedding.”

“It will be—and the wet as red as to-night’s

sunset.

But—per Cristo, Andrea mio, you know

the hill-saying:

When ’tis wet, who can say there shall be no

flood?”

“Ay: so. Their kinsfolk would not hold Vittoria and

Anita free of their blood-ban if once they be wedded.”

“Giovan’ Antonio—Holy Virgin, he would kill them

himself for it! “

Suddenly the boy Guido, slipping a rough wooden

cross from his neck, stepped close to the young men.

“Will you swear upon it, Andrea Falcone and Marco

Vaccaro. that henceforth I am your younger brother:

and that your home

in San Angelo in Capoccia shall be

my home: and your kin my kin: and we

be one ever-

more in the curse and in the blessing? Already you

are

my elder-brothers, but you have not sworn. Will

you swear now ?

“Why, Guido, my brother?”

“For I have that to say which being said makes me

no more of my father’s household or even of San Polo.”

“Thou art my brother for evermore, Guido Della

Porta,” said Andrea, solemnly, kissing the cross and

making the sacred

sign upon his forehead and upon his

breast.

When Marco had done likewise, Guido looked

fear-

fully around, and then with downcast eyes and trembling

hands

whispered that he was breaking a solemn vow

which he had perforce taken

that very day.

“Speak, boy,” muttered Marco, hoarsely.

Fear not,” said Andrea, more gently: “Father

Gian-

pietro will absolve thee to-morrow, or as soon as you can

come to San Angelo.”

“I heard—I heard—my father laughing with Simone

Gaetano. When I looked through the chink in the

great barn, I saw

that Gregorio da Forma was also there,

with his hand at his mouth

half-covering his black

beard. Simone’s smooth, fat face was agleam

with

sweat, and he rubbed his bald forehead again and again.

though his eyes narrowed and widened like a cat’s in

THE RAPE OF THE SABINES 35

the twilight. All the time I watched, Simone never

ceased to wipe his

brows, and never once did Gregorio

take away his hand from his

mouth.”

“The cursed traitor knows his weak member,”

mut-

tered Marco, savagely. “Aha! Signore Gregorio da

Forma. I know

that which would bring you to the

hangman in Rome, or the knife

anywhere where men

say Garibaldi and Italia in one breath!”

“Hush, Marco; don’t be a fool! The traitors’ death

is already arranged by God. The ink which was black

is turning red, and

the hour is at hand. Guido, say

what you have to say.”

“Ecco, my elder-brothers: I

heard this thing. My

father at first would have nought to say to

comfort

Simone and Gregorio when they told him of the rumour

that

Vittoria and Anita had sworn the virgin-vow against

them. But at last

Simone, miserly though he be, won

him over. He promised him”—

“Corpo di Cristo, Guido,”

broke in Andrea; “never

mind that. Tell us,

quick, what your father agreed to.”

“He said that, if he got what he wished, Simone and

Gregorio might laugh at the girls’ vows, for he

would

see that his good friends did not marry

virgins.”

Both Andrea and Marco started, and each

instinctively

clasped his knife.

“Yes, I swear it. My father, may God forgive him,

said that no one should be in the house to-night, after

the feast which

he is to give is over; and that Simone

and Gregorio might take that

which would be theirs by

law on the morrow. The virgin-vow would

thus

be made useless as old straw, as void as yesterday’s wind.

There would be none to interfere. If the girls

screamed “—

“Basto! Enough!” shouted

Andrea recklessly;

while Marco made a low, hissing noise like a

wind-eddy

upon ice. “Is this thing to be done to-night? Ay, so:

I

believe you. No, no: I want to hear no more. What

does anything else

matter. We must be there, too,

Marco—if we have to go to our death at

the same time.

“Come: there is no time to lose,” was all that

Marco

replied; though, after a moment’s hesitation, he stooped

36 THE PAGAN REVIEW

and whispered in his cousin’s ear. Andrea smiled grimly.

“What time was the supper to be, Guido?” he asked.

“As soon as the sun had set. And all are to go

to

their homes by nine at latest. There is to be a

sunrise-Sacrament

to-morrow, and everyone will be

abed early. Vittoria and Anita will not

sit long with

the men; but go to their room, where my father will

doubtless lock them in.”

“But you can get into the room by your attic?”

“Ay: and out easily enough by the window

over-

looking the Vicolo da Pozza.”