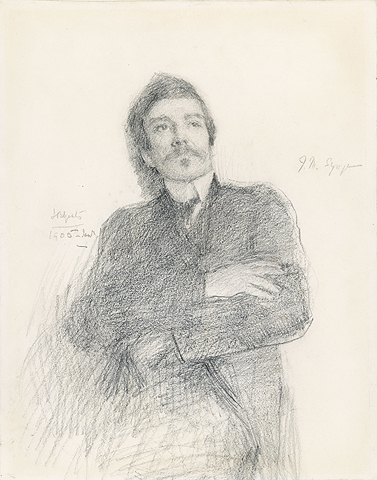

John Millington Synge

(1871 – 1909)

(Edmund) John Millington Synge was an Irish playwright, theatre director, poet, and travel writer. His participation in the early-twentieth-century Irish dramatic revival in Dublin with W. B. Yeats (1865-1939) and Lady Augusta Gregory (1852-1932) and the simultaneous acclaim and controversy of his plays—especially his masterpiece The Playboy of the Western World (1907)—have granted him a place in the pantheon of playwrights and founding figures of Ireland’s national theatre. While reviving Irish culture in an anti-colonial way through attention to vernacular language, locality, residual modes of living and mentalities of rural Ireland, Synge’s plays also critique sexual prudishness, the institution of marriage, patriarchal gender norms, organized religion, and bourgeois society. In addition, his drama offers a canny satire of modes of revivalism in Ireland at the turn of the twentieth century, particularly the Irish nationalist tendencies of equating authentic Irishness uniquely with the Catholic Church and with an idealised version of the Irish-speaking peasantry. Synge’s oeuvre transgresses the perceived insularity and regressive nativism with which the Irish revival is often associated and, through an iconoclastic attitude and articulation of the tensions between tradition and modernity, aligns with modernist aesthetics.

Synge was born on April 16, 1871, in Rathfarnham, Co. Dublin, in a Protestant Anglo-Irish family. He grew up with his mother Catherine (Kathleen) Traill (1838-1908) and seven other siblings in various Dublin suburbs and the neighbouring mountainous region, Wicklow, where his extended family had owned estates. His father, John Hatch Synge (1823-1872), died when Synge was only a year old. Mostly schooled at home due to ill health, Synge displayed a keen interest in the natural world from an early age; his readings of Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) evolutionary writings during his teenage years caused him to reject God and the church, thus distancing himself from the family’s staunch religiosity. Synge went to Trinity College Dublin from 1889 to 1892, graduating in Hebrew and Irish. During his university years, he was a “stay-at-home student” who continued to live with his mother in Rathgar while attending lectures in the city and training as a musician at the Royal Irish Academy of Music (McCormack 82-83).

Throughout the 1890s, however, Synge left home and undertook several formative trips to Europe. This decade was crucial for Synge’s artistic growth as his travels, encounters, and education on the continent contributed to a solid academic foundation for his artistic practice and to the European and radical outlook of his work. In 1893 and 1894 he first travelled to Koblenz and Würzburg in Germany to perfect his musical training. He decided, however, not to pursue a career in music as he did not feel comfortable performing live (Kiberd, “Synge”). Between 1895 and 1902, Synge spent several months each year in Paris, making the French capital his base to continue his eclectic studies. For example, he took courses in French and medieval literature at the Sorbonne, comparative phonetics at the École Pratiques des Hautes-Études, and Irish and Homeric civilisation at the Collège de France with Henri d’Arbois de Jubainville (1827-1910), who adopted an influential comparative approach to the understanding of civilisations. His interest in languages was an important part of his approach to travel: in the areas he visited, Synge always went linguistically prepared. After learning German, French, and Irish, he took classes in Italian prior to his 1896 sojourn in Florence and Rome. Before his 1899 visit to Brittany, he studied Breton language and folklore, reading, among others, the work of folk collector Anatole Le Braz (1859-1926), who would later visit Dublin in 1905 and meet with various personalities of the Irish dramatic revival, including Synge (Le Braz 68-97).

Paris also offered the opportunity for an immersion into socialist and anarchist thought: Synge attended occasional lectures on the subject and read a wide range of seminal texts by Karl Marx (1818-1883), William Morris (1834-1896), Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921), John Hobson (1858-1940), Victor Considerant (1808-1893), and Paul Lafargue (1842-1911) (Levitas 82). Lastly, Paris was also instrumental to develop important Irish connections as in the 1890s it was a central hub for many Irish literati and advanced nationalists. There, Synge met W.B. Yeats (1896) and attended meetings of Maud Gonne’s Association Irlandaise (1897), whose physical force nationalism he rejected. Instead, Synge resolved “to work in my own way for the cause of Ireland” (Synge, Collected Letters Vol. 1 47). During a final, shorter trip to Paris in 1903, Synge also crossed paths with James Joyce (1882-1941).

The 1896 Parisian meeting with Yeats is generally considered the turning point for Synge’s literary career, not least by Yeats himself, who famously advised Synge to give up Paris and the idea of becoming a scholar—“Arthur Symons will always be a better critic”—and travel instead to the Aran Islands to live like one of the people and express a life that had yet to find expression (Yeats, “Preface” 63). While Yeats’s advice ultimately had the desired effect, Synge’s academic background in Dublin and Paris was equally an incentive for his journeys to the West of Ireland undertaken between 1898 and 1908. Another influence was the pre-existing popularity of the islands among antiquarians, scholars of Celtic languages, Irish language activists, and writers alike (see Brannigan). His wide-ranging philosophical and scientific readings, along with his university training in literature, language, and Celtology, made him especially attuned to the linguistic richness of both the Irish language and the Hiberno-English (the variety of English influenced by Gaelic syntax) spoken in Ireland. A more poetic rendition of this Irish-inflected English would become a landmark feature of his plays.

During his travels in Ireland, Synge visited peripheral rural regions—the Aran archipelago, the Blasket Islands, West Kerry, Connemara, and Mayo—which he turned into the iconic settings for his drama. In addition, he also drew on the Wicklow region, his family homeland, whose woods, rivers, and valleys he knew inside out since his younger years. During these trips, Synge recorded folklore from the local communities in his notebooks, drafted topographical essays, and took ethnographic photographs. For example, his trips to Aran between 1898 and 1902—the base for his travel book The Aran Islands (1907)—were first distilled in articles for periodicals of various leanings and agendas, and his Aran photographs were used by Irish painter Jack Butler Yeats (1871-1957) to make the illustrations for the first edition of Synge’s travelogue.

Synge’s short article, “A Dream on Inishmaan,” written for the second number of The Green Sheaf in 1903 was one of four articles drawing on his Aran experience that he placed in various periodicals after his first trip. For instance, “A Story from Inishmaan” appeared in the Dublin-based New Ireland Review (1894-1911) in November 1898; “The Last Fortress of the Celt” in the Irish American monthly The Gael in April 1901; “An Impression of Aran” in the Manchester Guardian (founded in 1821 and still running today as The Guardian) on January 24, 1905. The same “A Dream on Inishmaan” published in The Green Sheaf was also re-published in The Gael in 1904 and reprinted in the 1907 book exactly as it appears in the periodicals, since Synge’s full account of Aran, albeit following a general chronological order based on his yearly visits, is presented as a collage of episodic vignettes.

Synge’s collaboration with The Green Sheaf likely resulted from several networking meetings with influential London-based artists and publishers facilitated by both Yeats and Gregory. Between January and March 1903, in London, Synge met literary personalities such as The Green Sheaf’s creator and artist Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951), poet John Masefield (1878-1967), and poet and critic Arthur Symons (1865-1945) (Saddlemyer, Collected Letters Vol 1 61). Yeats and Gregory organized these meetings to foster their Irish national theatre project. First concretized in 1899 as the Irish Literary Theatre, Yeats and Gregory’s project staged performances of Irish plays in both Gaelic and English in hired venues around Dublin; in 1902, their venture became the Irish National Theatre Society (1902), availing itself for the first time of a professional group of Irish actors coordinated by actors and producers William Fay (1872-1947) and his brother Frank (1870-1931); in 1904, with the help of wealthy patron Annie Horniman (1860-1937), the theatre found a permanent Dublin venue in what is still today the Abbey Theatre. The 1903 London meetings with influential literary figures served Yeats and Gregory the purpose of reading Synge’s first two plays The Shadow of the Glen and Riders to the Sea in front of an interested audience (Saddlemyer, Theatre Business 39). Symons was so enthusiastic about Synge’s works that in a letter to Gregory he suggested pitching them for publication in the Fortnightly Review; the magazine, however, rejected them (Saddlemyer, Theatre Business 39-40). In the same year, John Masefield also championed Synge’s Aran book with Charles Elkin Mathews (1851-1921) (Saddlemyer, Theatre Business 47-48), though the volume would only be jointly printed by Maunsel and Mathews four years later.

Part of a thematic issue of The Green Sheaf on dreams, with contributions by Masefield, Smith, and Yeats as well, “A Dream on Inishmaan” describes a dream Synge had while staying on this island off Ireland’s western seaboard. A musical whirlwind generated by a string instrument and growing in intensity pushes the author’s unwilling limbs into a frantic dance, interrupted only by Synge’s awakening to the stillness of the island. Seán Hewitt reads this episode as “designed to exemplify [Synge’s] reading in occultist and anthropological works … during the late 1890s,” and the author’s final awakening as the beginning of his “pragmatic approach to modernization without jeopardising his association of the island with spirituality” (44, 46). Depictions of the Aran Islands as a dream-like space had also featured in Symons’s earlier account of an Aran journey he undertook with Yeats and Edward Martyn (1859-1923) in 1896. Symons’s “The Isles of Aran” was included in the final volume of The Savoy (December 1896) and in the collection Cities and Sea-Coasts and Islands (1918). Yeats could have had his own trip to Aran in mind when he gave Synge the famous advice, though, as noted above, Yeats’s mythologizing of Synge during and after his life is only one of several contexts in which to understand Synge’s draw to the islands.

Synge’s experience of life on the Aran Islands saw its dramatic rendition in the one-act tragedy Riders to the Sea (composed in 1902; first performed in 1904), about the drowning of the last two sons of an old island woman, Maurya, who is left to keen over them together with her two daughters. In 1902 Synge also drafted The Shadow of the Glen (first performed in 1903), centred around a peasant woman from Wicklow trapped in a loveless marriage, who leaves her older husband to embrace a nomadic life with a tramp. While Riders was generally well received for the perceived authenticity to island life, Shadow was criticized by contemporaneous nationalist audiences for the Ibsenist portrayal of the female protagonist (named Nora like the protagonist of Henrik Ibsen’s The Doll’s House), who subverted nationalist notions of Irish peasant women seen as subservient in the marriage relationship. In 1902 Synge also started writing another play set in Wicklow, The Tinker’s Wedding, with characters belonging to the Irish Travellers community, a nomadic ethnic minority; the play was published in 1907 but first performed only after Synge’s death, partly because of its controversial depiction of a Catholic priest.

1905 saw the production of another play set in Wicklow and centred on itinerant characters, The Well of the Saints, for which Pamela Colman Smith designed the scenography. Later in that year Synge also took administrative responsibility at the Abbey Theatre, becoming co-director with Yeats and Gregory. In June 1905, he travelled to Connemara and Mayo with Jack Yeats on a journalistic commission for the Manchester Guardian and produced twelve finely illustrated investigative essays which evaluate and critique the work of the constructive unionist governmental body Congested Districts Board by voicing the local population’s own concerns to the modernizing changes, implemented at times hurriedly and with little regard for local traditions. Synge’s collaboration with the Guardian had begun a few years earlier, thanks to Masefield’s introduction (Grene, Introduction xl). In 1906, the literary periodical The Shanachie (1906-1907), published by Maunsel, featured his essays on the Blasket Islands and West Kerry. On January 26, 1907, the first performance of Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World stirred up another row: the audience rioted in the theatre when they heard the mention of female undergarments—the word “shifts” (Collected Works Vol. IV 167). Playboy stages the harbouring of a parricide by an impoverished rural community in Mayo and satirises the darkly comic transformation of the protagonist from a frightened criminal on the run into a local celebrity. However, once again Synge’s play did not match nationalist views of an idyllic rural Ireland, or support “a hero-cult then promoted through the figure of Cú Chulainn by revivalists (including Yeats and … Gregory, fellow directors of the Abbey) (Kiberd, “Synge”).

After Playboy, Synge started composing a new play, Deirdre of the Sorrows, inspired by the ancient Irish sagas, but also a topic regularly taken up by Irish revivalists like A.E. (George Russell), whose Deirdre: A Drama in Three Acts had been published as a supplement to The Green Sheaf, Number 7 (1904), with the permission of the Irish National Theatre Society, which owned dramatic rights. His promising career and an intimate relationship with one of the actresses of the theatre company Maire O’Neill (also known as Molly Allgood) (1886-1952) was curtailed by a deadly cancer that killed him in 1909. Yeats and Gregory completed the drafts of Synge’s unfinished work, which was produced in 1910 at the Abbey Theatre with O’Neill as Deirdre. Synge’s short life and career left a global legacy which continues to inspire dramatists. Significantly, his plays were the only ones belonging to Ireland’s early dramatic movement to be translated into French, German, and Czech while Synge was still alive. Throughout the twentieth century, they were also the object of several adaptations and postcolonial rewritings, notably, Derek Walcott’s The Sea at Dauphin (1979) and Mustafa Matura’s The Playboy of the West Indies (1984).

©2021, Giulia Bruna, Postdoctoral Fellow, Radboud University and Radboud Institute for Culture and History, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Giulia Bruna is a postdoctoral fellow at Radboud University in the Netherlands. She is the author of J. M. Synge and Travel Writing of the Irish Revival (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse UP, 2017); her research on Synge, the Irish literary revival, Irish travel writing, Irish periodical culture, and nineteenth-century British local-colour fiction has appeared in the Irish Studies Review, Studies in Travel Writing, Journal of Modern Periodical Studies, and Translation and Literature.

Selected Publications by John Millington Synge

- —. “A Dream on Inishmaan.” The Green Sheaf, no. 2, 1903, pp. 8-9. The Green Sheaf Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2021-2022.

- —. J. M. Synge: Collected Works. Vol. I: Poems, edited by Robin Skelton. Colin Smythe, 1982.

- —. J. M. Synge: Collected Works. Vol. II: Prose, edited by Alan Price. Colin Smythe, 1982.

- —. J. M. Synge: Collected Works. Vol. III: Plays, Book 1, edited by Ann Saddlemyer. Colin Smythe, 1982.

- —. J. M. Synge: Collected Works. Vol. IV: Plays, Book 2, edited by Ann Saddlemyer. Colin Smythe, 1982.

- —. J. M. Synge: Travelling Ireland, Essays 1898–1908, edited by Nicholas Grene. Lilliput Press, 2009.

- —. Letters to Molly: John Millington Synge to Maire O’Neill, 1906–1909, edited by Ann Saddlemyer. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971.

- —. My Wallet of Photographs: The Collected Photographs of J. M. Synge, arranged and introduced by Lilo Stephens. Dolmen Editions, 1971.

- —. The Collected Letters of John Millington Synge Vol. 1: 1871– 1907, edited by Ann Saddlemyer. Clarendon Press, 1983.

- —. The Collected Letters of John Millington Synge Vol. 2: 1907–1909, edited by Ann Saddlemyer. Clarendon Press, 1984.

Selected Publications about John Millington Synge

- Brannigan, John. “Folk Revivals and Island Utopias.” Archipelagic Modernism: Literature in the Irish and British Isles, 1890-1970. Edinburgh University Press, 2015, pp. 21-67.

- Burke, Mary. “Tinkers”: Synge and the Cultural History of the Irish Traveller. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Cliff, Brian, and Nicholas Grene, eds. Synge and Edwardian Ireland. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Collins, Christopher. Theatre and Residual Culture: J.M. Synge and Pre-Christian Ireland. Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Grene, Nicholas, ed. Interpreting Synge: Essays from the Synge Summer School 1991– 2000. Lilliput Press, 2000.

- —. Introduction. J. M. Synge: Travelling Ireland, Essays 1898–1908, edited by Grene. Lilliput Press, 2009, pp. xiii-xlix.

- —. Synge: A Critical Study of the Plays. Macmillan Press, 1985.

- Hewitt, Seán. J. M. Synge: Nature, Politics, Modernism. Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Kiberd, Declan. Synge and the Irish Language. Gill and Mac Millan, 1979.

- —. “Synge, (Edmund) John Millington.” Dictionary of Irish Biography. 2009. https://www.dib.ie/biography/synge-edmund-john-millington-a8429. Accessed August 30, 2021.

- Le Braz, Anatole. Voyage en Irlande au Pays de Galles et en Angleterre, edited by Alain Tanguy. Terres de Brume (Editions), 1999.

- Lecossois, Hélène. Performance, Modernity and the Plays of J. M. Synge. Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Levitas, Ben. “J. M. Synge: European Encounters.” The Cambridge Companion to J. M. Synge, edited by P. J. Mathews. Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 77-91.

- Lonergan, Patrick. ed. Synge and His Influences: Centenary Essays from the Synge Summer School. Carysfort Press, 2011.

- Mathews, P. J., ed. The Cambridge Companion to J. M. Synge. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Mc Cormack, W. J. Fool of the Family: A Life of J. M. Synge. Weidefeld and Nicolson, 2000.

- Ritschel, Nelson O’Ceallaigh. Synge and Irish Nationalism: The Precursor to Revolution. Greenwood Press, 2002.

- Roche, Anthony. Synge and the Making of Modern Irish Drama. Carysfort Press, 2013.

- —. The Irish Dramatic Revival: 1899-1939. Bloomsbury, 2015.

- Saddlemyer, Ann, editor. Theatre Business. The Correspondence of the First Abbey Theatre Directors: William Butler Yeats, Lady Gregory and J. M. Synge. Colin Smythe, 1982.

- Symons, Arthur. “The Isles of Aran.” The Savoy. Vol. 8, December 1896, pp. 73-86. Savoy Digital Edition, edited by Christopher Keep and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2018-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2019. https://1890s.ca/savoyv8-symons-aran/.

- Yeats, William Butler. “Preface to the First Edition of The Well of the Saints: Mr. Synge and His Plays” Collected Works. Vol. 3: Plays, Book 1, edited by Ann Saddlemyer, Colin Smythe, 1982, pp. 63-68.

MLA citation:

Bruna, Giulia. “John Millington Synge (1871-1909),” Y90s Biographies. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2022, https://1890s.ca/synge_bio/